Abstract

A remote collection of biofluid specimens such as blood and urine remains a great challenge due to the requirement of continuous refrigeration. Without proper temperature regulation, the rapid degradation of analytical targets in the specimen may compromise the accuracy and reliability of the testing results. In this study, we develop porous superabsorbent polymer (PSAP) beads for fast and self-driven “microfiltration” of biofluid samples. This treatment effectively separates small analytical targets (e.g., glucose, catalase, and bacteriophage) and large undesired components (e.g., bacteria and blood cells) in the biofluids by capturing the former inside and excluding the latter outside the PSAP beads. We have successfully demonstrated that this treatment can reduce sample volume, self-aliquot the liquid sample, avoid microbial contamination, separate plasma from blood cells, stabilize target species inside the beads, and enable long-term storage at room temperature. Potential practical applications of this technology can provide an alternative sample collection and storage approach for medically underserved areas.

The challenge of disease diagnosis in rural areas and low-income countries is still huge.1 It is a common practice to ship biofluid specimens for off-site diagnostic tests in resource-limited areas.2−4 For example, during the global outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, an at-home collection kit was developed for point-of-use tests, the samples for which can be collected at home and sent to certified laboratories. Traditionally, biofluid specimens need to be refrigerated upon collection and processed in a short time (e.g., within the same day).5,6 The handling, storage, and transportation of biofluid specimens such as blood and urine without refrigeration are extremely challenging. Hemolysis, the poor stability of molecular biomarkers (especially proteins), and the fast growth of contaminating bacteria at ambient temperatures significantly compromise the quality of the testing results generated. Hemolysis is one of the most common preanalytical sources of error for blood samples found in clinical laboratories, accounting for 40 to 70% of unsuitable samples identified.7,8 The release of intracellular analytes into plasma or serum in hemolyzed samples is known to cause bias in testing results (e.g., serum potassium, lactate dehydrogenase, and aspartate aminotransferase).9 Even if removing the blood cells, without temperature regulation, protein biomarkers in the separated plasma or serum samples degrade quickly, accounting for up to 67% of the laboratory testing errors.10,11 Meanwhile, urine samples are usually contaminated by urethral flora, which can multiply rapidly to 104 CFU mL–1 within 1 day in freshly voided urine.12,13 Previous research has demonstrated the adverse effects of microbial contaminations on the urinary detection index (e.g., glucose, steroid, and microalbumin).14−16

In general, refrigeration storage and transportation are not feasible both logistically and financially in resource-limiting settings. Thus, many biofluid samples may not be preserved appropriately before arriving at centralized laboratories, which hinders remote sample collection, disease screening, early diagnosis, and clinical intervention in underserved populations. Therefore, there is an urgent need for low-cost, effective, reliable, and easily applicable biofluid sample preservation technologies. Promising alternative non-refrigeration preservation methods have been enabled by various functional materials and novel approaches, including dried spot sampling, isothermal vitrification, lyophilization, and biomaterial encapsulation.17−23 However, they still cannot entirely substitute the convectional method and are limited by (i) long sample treatment time, (ii) high cost, (iii) intensive instrument requirement, (iv) complex operation, and/or (v) inadequate protective capacity. For example, a silk matrix was applied to encapsulate and protect protein biomarkers in blood from thermally induced damage and achieved long-term IgE preservation (up to 84 days at 45 °C).22 Nevertheless, it took 8 h for the blood samples to air-dry in a sterile environment, and the silk material used was relatively expensive.

In addition, removing blood cells by centrifugation is usually required for long-term storage of blood-derived samples to avoid effects of hemolysis, but conventional centrifuges are bulky, expensive, and electrically powered, thus typically inaccessible in resource-limiting areas. Some hand-powered and low-cost centrifuges have been developed for fast and effective separation of blood cells and plasma. For example, a paper centrifuge inspired by whirligig toys has been developed and achieved centrifugal forces of 30,000g to separate plasma from blood samples within 1.5 min.24 Other alternative gadgets include a vegetable-dehydrator-like centrifuge, an egg-beater-based centrifuge, and a groove-based microfluidic device.25,26 However, these portable centrifuges usually require multiple-step operations and cannot effectively process a large volume of samples.

Superabsorbent polymers (SAPs) have been widely used in personal hygiene products, food and agricultural industries, and medical applications since the 1980s.27−30 We consider the SAPs for potential applications in biofluid storage because of their superior water absorbing capacity and unique three-dimensional crosslinked network. However, although they can retain a large amount of water and aqueous solution, only ions and molecules smaller than a few nanometers are able to enter the SAPs together with water.31 In addition, porous polymers are particularly attractive for their large surface areas, tunable pore structures, chemical diversity, and easy processability.32 The building blocks, crosslinking method, and functional additives of the the porous polymers in the synthesis can be tailored to achieve desired ionic conductivity, mechanical properties, stimuli-responsiveness, swelling behaviors, and even controllable polymer–matter interaction at the molecular level.33−35 Thus, the porous polymers become an emerging material platform for water and energy technologies. For example, Guo and co-workers developed biomass-derived porous hybrid hydrogel as solar evaporators for fast and cost-effective water purification, which accomplished a high evaporation rate toward wastewater and high-salinity seawater.36 Recently, researchers have opened more possibilities for porous polymers in biomedical applications such as drug delivery, tissue engineering, and biosensor development.37−40 For example, Xu and co-workers fabricated porous polymer encapsulated photonic barcodes that achieved sensitive and reliable detection of MicroRNA targets using only a 20 μL sample.41 Wen and co-workers synthesized temperature-responsive porous polymer microparticles loaded with oncology drugs, which realized a controllable and sustained delivery of the active components to the tumor site.42

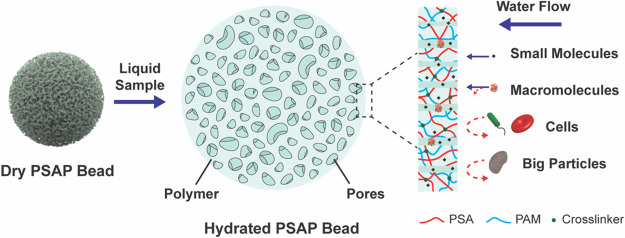

In this study, we report a self-driven microfiltration treatment enabled by porous superabsorbent polymer (PSAP) beads for biofluid specimen processing and storage. The synthesized PSAP bead has a well-controlled porous structure for selective absorption of target species in the biofluid, and an excellent swelling capacity to store the biofluid together with analytical targets inside the bead. Different from the traditional filtration process where the filtrate passes through the filter due to a pressure difference, in this self-driven microfiltration treatment, the filtrate is retained in the PSAP beads. The main purpose of this treatment is to improve the preservation of biofluid samples without refrigeration. In this particular application, we have designed and synthesized PSAP beads (∼2 mm) with pores of 0.5–1 μm that can capture small analytical targets (<0.5 μm) but exclude bacteria and blood cells (>1 μm) in the biofluid samples, thus avoiding the impact of microbial spoilage and hemolysis on the shelf life of the analytical targets. As illustrated in Figure 1, the interconnected pores inside the bead construct water channels and achieve separation of target species based on size exclusion, which allows the sorption of all small molecules (e.g., ions and sugars) and most macromolecules (e.g., protein and nucleic acids) while rejecting large components (e.g., bacteria and blood cells). In addition, the size of the target species also determines their distribution in the beads after the sample treatment. The macromolecular species with relatively high molecular weight mainly attach to the inner surface of the beads or suspend in the water channels, but some small species with very small molecular weight may be intercalated into the polymer chains together with water. For this claim, different sizes of target species (from ∼1 nm to 15 μm) in various biofluid media (from simple saline to complex blood) have been applied to demonstrate the effectiveness of the microfiltration and shelf life extension with the PSAP beads.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the PSAP beads for the microfiltration of target species in biofluid specimens. The PSAP beads capture small analytical targets while rejecting large undesired components along the water absorption to achieve the self-driven microfiltration. The polymer network of the beads is synthesized by poly(sodium acrylate) (PSA) crosslinked with polyacrylamide (PAM).

Characterization of PSAP Beads

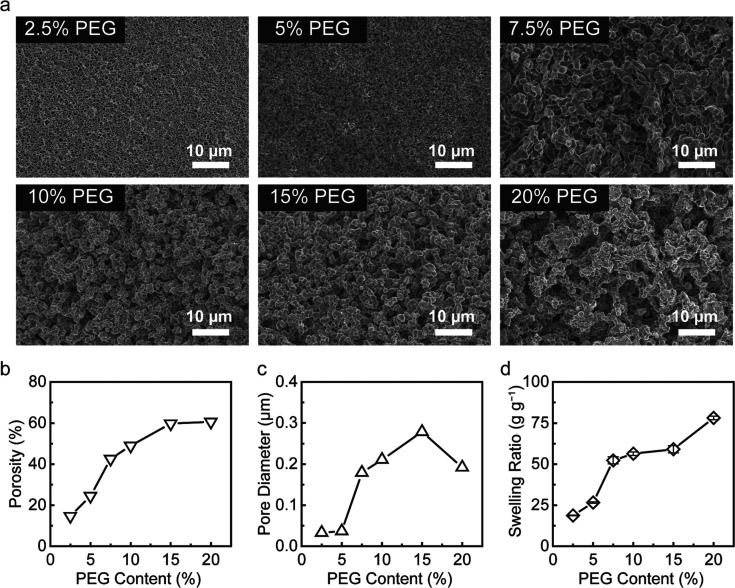

In order to demonstrate the microfiltration procedure using the PSAP beads for liquid samples, we have successfully used a dry-bath batch method to prepare millimeter-sized and bullet-shaped PSAP beads via polymerization induced phase separation (Figure S1).43,44 The pores were formed by the polymerization and crosslinking of monomers in aqueous PEG solution, in which the crosslinked polymer chains constructed a scaffold while PEG served as a porogen. On the basis of the previous studies, the polymerization conditions including reaction temperature, monomer composition, and crosslinking degree were optimized to obtain PSAP beads with desired uniform morphology and swelling behavior (details described in Supporting Information 2.1 and 2.2). In addition, to investigate effects of the PEG concentration on the pore structure of the resulting PSAP beads, reaction mixtures with an addition of different PEG amounts (2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, 15, and 20 wt %) were prepared, and the as-synthesized dry PSAP beads were characterized by SEM. As shown in Figure 2a, the morphology of the beads is strongly affected by the precursor composition. At a PEG content of 2.5 or 5 wt %, the PSAP beads reveal a continuous polymer network with small spherical pores (Figure 2a and Figure S2). When the PEG content is higher than 5 wt %, the polymer scaffold changes to a dendritic structure with interconnected irregular shaped pores. The significant morphology shift is due to the polymer–solvent interaction during phase separation.32 For a precursor with a high PEG concentration, the phase separation process occurs prior to the gel point because of the repulsion between the polymer segments and the aqueous PEG solution. As a result, the porogenic nuclei aggregate and a discontinuous polymer network is formed with large pores. Therefore, with the growing PEG content, the pore size of the PSAP beads increases. However, once the PEG content reaches 20 wt %, a relatively high repulsive interaction results in large cavities inside the polymer system, and these defects may diminish the selectivity of the PSAP beads in the proposed microfiltration applications.

Figure 2.

Characterization of the PSAP beads. (a) SEM images of PSAP beads polymerized by precursors containing different concentrations of PEG-6000 from 2.5 to 20 wt %. (b) Porosity of the PSAP beads. (c) Average pore diameter of the PSAP beads. (d) Swelling ratio of the PSAP beads in the saline (0.9% NaCl solution).

MIP was used to measure the total pore volume, total pore area, and bulk density of the dry PSAP beads for analysis of the pore structure (Table S1). As shown in Figure 2b, the porosity of the PSAP beads increases with the increased PEG content and can reach up to 60%. Meanwhile, the pore size of the beads has a significant increase as the PEG content is higher than 5 wt % (Figure 2c), which is consistent with the change of the polymer morphology (Figure 2a). When the PEG content is 7.5 to 15 wt %, the average pore diameter based on MIP is ∼0.15 to 0.3 μm. In addition, there is a slight decrease in the average pore diameter at 20 wt % of PEG, which may be caused by the uneven distribution of pore size and the existence of numerous small pores inside the polymer network (Figure 2a).

The pore structure estimated by MIP only provides information concerning a dry polymer in the unswollen state, but not at the conditions in which it usually works. Since the PSAP beads can swell in water and become hydrated, the pore size will become larger as the polymer chains relax and absorb water. The swelling process of the PSAP beads in the saline medium (0.9% NaCl in DI water) was monitored to determine both swelling kinetics and equilibrium swelling capacity. The results of normalized bead diameters versus time indicate that the beads with different pore structures can all reach their maximum swelling capacity within 5 min in the saline (Figure S3). The weight swelling ratio of the PSAP beads in the saline was measured to simulate the size expansion of the pores in biofluid media. It can be seen from the swelling ratio data in Figure 2d that the equilibrium swelling capacity increases as the PEG content increases. The swelling ratio is less than 30 g g–1 with a low PEG content (less than 5 wt %) since a rigid polymer network and high mechanical strength cause difficulty in water diffusion inside the beads. When the PEG content is 7.5 to 15 wt %, the swelling ratio of the beads increases significantly and reaches ∼50 to 60 g g–1 because a high porosity can promote relaxation and disentanglement of the polymer chains. As the PEG content is further increased to 20 wt %, the swelling capacity can be as high as ∼80 g g–1 due to the contribution of large cavities inside the beads (Figure 2a).

In addition, the as-prepared PSAP beads have a uniform size and a stable swelling capacity with the same precursor composition (Figure S4). For example, when the PEG content is 10 wt %, a single dry bead has an average weight of 1.6 mg (weight variation<7%), and a hydrated bead has an average weight of 96.1 mg (weight variation<4%). Thus, if applying the PSAP beads for liquid sample collection, it is easy to aliquot the potential-target-containing liquid into the beads spontaneously and simultaneously. For biofluid specimens, aliquoting a specimen into several measured portions for either parallel or different tests is common and necessary for practical applications. The self-aliquoting function of the PSAP beads allows a simple way to divide the liquid sample collected by the beads into equal parts for multiple tests, respectively. Meanwhile, since each bead has a constant and precise swelling ratio, without pipetting or weighing it, the sample volume or weight can be calculated for quantitative analysis by directly counting the bead quantity.

Microfiltration Performance of PSAP Beads

The size screening effect for target species during the self-driven microfiltration treatment depends on both the pore structure and swelling capacity of the PSAP beads. When a PSAP bead swells with liquid samples, the liquid penetrates the pore interior initially and causes swelling of the surface layer of the polymer, which in turn leads to complete pore filling. Upon swelling, the relaxed polymer chains form a framework and the pores inside construct interconnected water channels filled by water molecules together with small target species. The relative size of the resulting water channels is a critical parameter for the size screening of the prospective target species. Only the target species with a size smaller than the swollen water channels can be effectively captured by the bead, while larger target species are excluded outside and thus removed. This critical size is determined primarily by the pore structure of the polymer. According to the needs of microfiltration, the PSAP beads should effectively absorb target species less than 0.5 μm while excluding any target species larger than 1 μm. A decrease in the average pore diameter of the beads should reduce the size of the water channels, which will result in a more effective exclusion of undesired large components. However, as the water channel dimensions decrease, the swelling capacity of the PSAP beads decreases, and the mechanical strength of the hydrated beads increases, which may cause difficulties in subsequent recovery of small species absorbed by the beads.

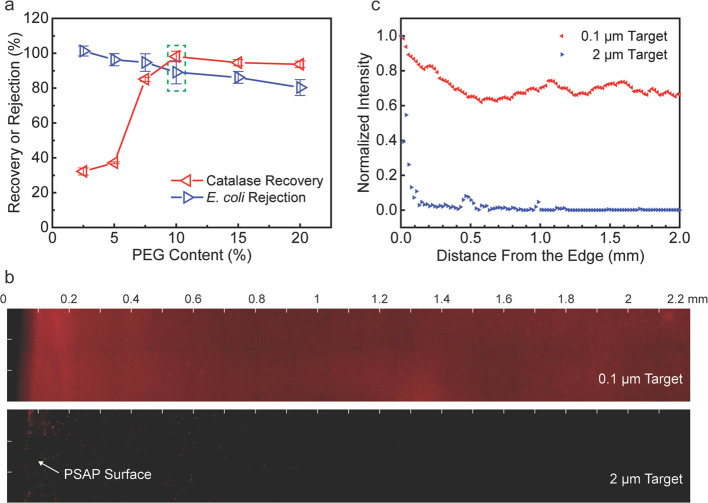

To investigate the critical channel size experimentally, as illustrated in Figure S5, the PSAP beads prepared with different PEG contents were applied to treat a saline medium containing catalase (a common enzyme in the human body with a size of ∼10 nm) or E. coli (a Gram-negative bacterium with a size of 1–2 μm). Figure 3a presents the recovery efficiency for catalase and the rejection efficiency for E. coli after the microfiltration treatment. For the PSAP beads prepared with a PEG content of 2.5 to 5 wt %, the recovery efficiency for catalase is less than 40%, although the characterization results of these beads indicate that they should be able to absorb such small targets. The reason for this is probably that the beads with a low PEG content present a rigid polymer framework together with a relatively high mechanical strength, which makes it challenging to break the hydrated beads and release the catalase captured without affecting its enzymatic activity. As the PEG content is increased to 7.5 wt %, the catalase recovery significantly increases to ∼85% due to a flexible porous structure and a high swelling capacity of the PSAP beads. When the PEG content is 10 to 20 wt %, the recovery efficiency for catalase remains at a high level (>90%), which suggests the recovery of small target species is not affected by the pore structure after the pore size reaches a certain threshold. For the exclusion of bacteria, the results shown in Figure 3a indicate superior exclusion performance of the PSAP beads for E. coli. In our method, the surface-attached E. coli cells on the beads after the treatment are not included in the excluded cells for rejection efficiency calculation. Under this definition, a complete exclusion (∼100% E. coli rejection) can be realized by the PSAP beads with 2.5 wt % of PEG. As the PEG content increases, the rejection efficiency slightly decreases since more bacteria attach to the enlarged water channels and thus remain on the bead surface after the treatment. Nevertheless, it can still achieve higher than 80% E. coli rejection even at a PEG content of 20 wt %. On the basis of the design criteria, an optimal porous network should achieve both a high recovery efficiency for small target species and a high rejection efficiency for undesired large components. Therefore, the PSAP beads with 10 wt % of PEG were selected and applied for further demonstration in biofluid sample treatment due to their optimized pore structure and excellent swelling properties.

Figure 3.

Microfiltration performance analysis in the saline medium. (a) Catalase recovery and E. coli rejection using the PSAP beads with a PEG content from 2.5 to 20 wt %. (b) Distribution of fluorescent microspheres (red under the fluorescent field) on the cross-section of the PSAP beads after the treatment. (c) Normalized fluorescence intensity from the edge to the core of the beads.

The fluorescent latex microspheres (0.1 or 2 μm in diameter, representing small or large target species) were used as standard target species to observe and visualize the distribution of target species on the bead surface or inside the beads after the microfiltration treatment. Figure 3b shows the two-dimensional mapping images of the fluorescent targets on the cross-section of the beads by fluorescence microscopy. The mapping results detecting the microspheres collected by the beads are in accordance with the results from catalase and E. coli treatment (Figure 3a). For 0.1 μm microspheres, the fluorescence signals distribute uniformly on the cross-section of the bead, and a slight aggregation phenomenon only appears on the edge (Figure 3b and details in Figure S6). On the other hand, for 2 μm microspheres, most of the microspheres are excluded outside the bead, while only a few microspheres are attached to the surface (Figure 3b and details in Figure S6). Figure 3c illustrates the intensity analysis of the fluorescent targets on the cross-section of the beads. The fluorescence intensity of small microspheres remains at a stable range from the near-surface to the core of the bead, while the intensity of large microspheres dramatically drops to near zero at a distance of 0.2 mm from the edge. Some small peaks of the fluorescence signal (e.g., at ∼0.5 mm and ∼1.0 mm away from the edge) are probably caused by contamination during the sample preparation. The results indicate that, although a few large target species may be left on the bead surface after the treatment, these undesired components are restricted to the surface area and cannot enter the bead or transfer inside the pores. Thus, the analytical targets captured by the beads will not be affected by these undesired components.

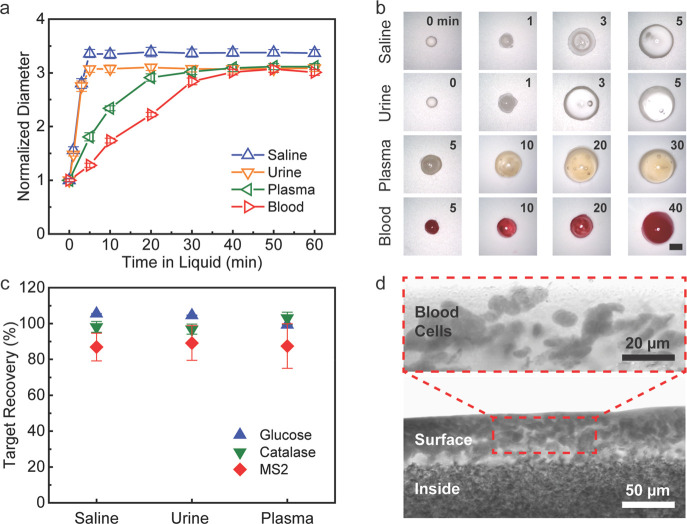

Microfiltration in Biofluid Media

A biofluid medium such as urine, blood plasma, or whole blood may contain organic compounds, macromolecules, or even live cells, which make it a highly complex system compared with the simple saline. To demonstrate the effectiveness of the PSAP beads for biofluid treatment, the swelling process of the beads in biofluid media, including synthetic urine, bovine plasma, and bovine blood, was investigated (Figure 4a). The results show that the PSAP beads can achieve a rapid expansion within 5 min in the synthetic urine. Meanwhile, for colloids like bovine plasma and blood, it takes a longer time for the PSAP beads to reach the swelling equilibrium (30-40 min). The relatively slow swelling process may be caused by the plasma proteins and blood cells, which probably impede the wetting of the bead surface or even block water channels, thus retarding the pore filling process. Although the swelling kinetics is affected by the medium permeability, the swelling ratio of the beads is almost the same for all three biofluid media (40–41 g g–1) due to their similar osmolarity (Figure S7). The optical images of the beads show the uniform expansion of the PSAP during the swelling despite the medium properties (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Microfiltration performance of the PSAP beads in biofluid media. (a) Normalized diameter of the PSAP beads in different biofluid media over time. (b) Optical images of the PSAP beads during the swelling process. The scale bar is 2 mm. (c) Recovery efficiency for glucose, catalase, and bacteriophage MS2 after the microfiltration treatment. (d) Bright-field microscopy images of the hydrated PSAP bead after swelling in the bovine blood medium.

To evaluate microfiltration performance, biofluid samples dosed with sugars (e.g., glucose), enzymes (e.g., catalase), or human virus surrogates (e.g., bacteriophage MS2) were treated by the PSAP beads. Figure 4c presents recovery efficiency for each target species in the saline, synthetic urine, or bovine plasma medium. For glucose and catalase, it shows close to 100% recovery in all three media. For bacteriophage MS2 (∼27 nm), the recovery efficiency shows a slight drop but remains above 85% in either fluid medium. A possible explanation for this might be that the ultrasonication process to release MS2 from the beads may cause minor damages to the viruses, but the double-layer-plating method only detects live viruses for recovery efficiency analysis and has a comparatively high method error. Overall, these findings, while preliminary, suggest that the PSAP beads can be potentially used to collect biomarkers from human biofluid samples for practical medical diagnosis. Turning to the most complicated medium (i.e., blood), although the beads after the microfiltration treatment become dark red (Figure 4b), the microscopy images in Figure 4d show that blood cells are blocked outside the bead due to their large size (∼6–8 μm for red blood cells and ∼12–15 μm for white blood cells). Quantitative analysis shows that only ∼12% of red blood cells remain on the bead surface after the treatment, while ∼88% of the cells are excluded and removed from the beads. This result indicates that the self-driven microfiltration enabled by the PSAP beads can achieve effective separation between blood cells and plasma without centrifugation. Since blood cells approximately account for half the volume/weight of a blood sample, the microfiltration treatment can easily reduce the sample volume by efficiently removing blood cells at the point of collection and halve the transportation load. Simultaneously, as the blood cells are separated from the potential-target-containing plasma in the hydrated PSAP beads, the hemolysis of the blood cells afterward will not affect the target species stored inside the beads.45

Shelf Life Extension against Bacterial Contamination

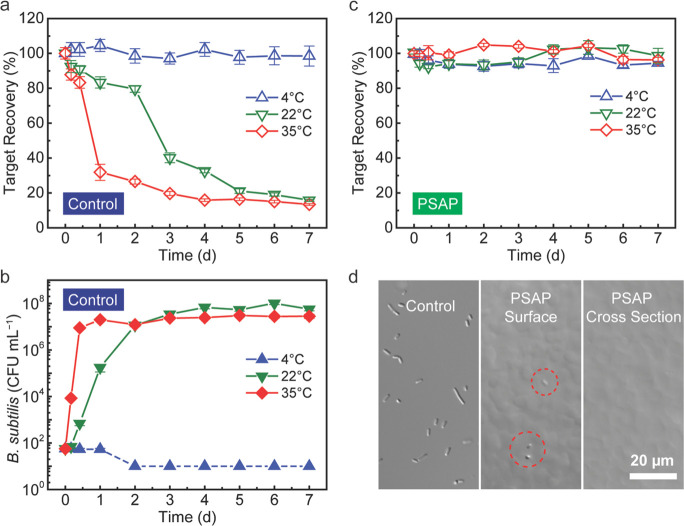

Previous studies have reported the adverse effects of improper storage conditions on the shelf life of analytical targets due to microbial activities.16 The shelf life extension ability of the PSAP beads against bacterial contamination was evaluated by using the saline medium containing the analytical target, catalase, together with Gram-positive bacteria, B. subtilis. As a widely used model organism for secreted enzyme production, B. subtilis is able to generate extracellular and membrane-bound proteases, which can cleave the peptide bonds within polypeptides or proteins by hydrolysis.46 After the microfiltration treatment, the enzymatic activities of catalase in the liquid control and the hydrated PSAP beads were monitored for 7 days at three different temperatures (4-35 °C). As shown in Figure 5a, with a small dosage of bacteria initially (∼50 CFU mL–1), the liquid sample loses ∼70% of catalase activity rapidly within only 1 day at 35 °C. At room temperature (22 ± 1 °C), the degradation of catalase in the control group is slower due to slower bacterial growth and thus less protease production, but it still loses ∼60% of activity gradually after 3 days. The reason that the catalase activity affected by bacterial degradation doesn’t fall to zero is that B. subtilis itself as a catalase-positive bacterium can produce catalase automatically.47,48 Therefore, while the initially added catalase is consumed, the catalase provided by the B. subtilis contributes to the total enzymatic activity, which is not negligible at a high bacterial concentration, but the determination of the shelf life is not affected. In the meantime, the liquid sample stored at 4 °C maintains a stable activity because the refrigeration effectively inhibits the bacterial growth (Figure 5b). Interestingly, there is a lag time in the correlation between the bacterial concentration and the remaining catalase activity. It takes 12 h at 35 °C or 2 days at 22 °C for the bacteria to reproduce to a concentration level of 107 CFU mL–1, but the dramatic drop in the catalase activity happens after 1 and 3 days at 35 °C and 22 °C, respectively (Figure 5a,b). This result may be explained by the fact that only after the bacterial concentration reaches a certain level, does the hydrolysis of catalase start to speed up with the help of enough protease, and the hydrolysis rate is also affected by temperature.

Figure 5.

Shelf life extension of catalase by the microfiltration treatment against bacterial contamination. (a) Catalase activity in the saline medium dosed with B. subtilis during the 7-day storage at 4, 22, or 35 °C. The initial bacterial dosage is ∼50 CFU mL–1. (b) Bacterial concentration that is corresponding to the catalase activity in (a) at each sampling time during the 7 days. The dashed line in b indicates no live bacteria are detected in the agar plates. (c) Catalase activity in the hydrated PSAP beads after the microfiltration treatment during the 7-day storage at 4, 22, or 35 °C. (d) Difference interference contrast microscopy images of the liquid control and the hydrated PSAP bead after the 7-day storage at 35 °C.

In contrast to the control groups, the catalase stored inside the PSAP beads remains higher than 90% of activity even after 7 days despite the temperature change (Figure 5c). As previously demonstrated, the PSAP beads can efficiently exclude bacterial cells during the microfiltration process, thus avoiding bacterial contamination on target species and effectively achieving extension of shelf life as with refrigeration storage. The microscopy images in Figure 5d show that although a few bacteria are left on the bead surface after the treatment, as expected, they cannot enter the bead even after 7 days at 35 °C due to the size limitation of the water channels.

Impacts of Medium Properties on Shelf Life

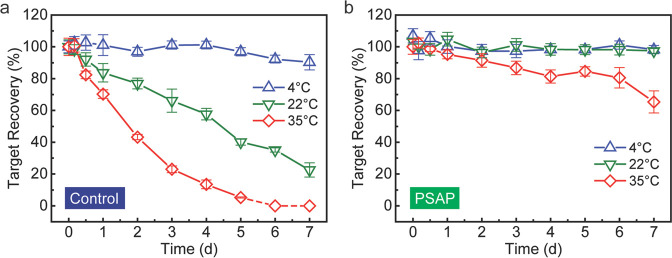

To investigate the impacts of medium properties on the target shelf life, a storage study was performed to examine the stability behavior of catalase across time in a bovine plasma medium. Unlike in the saline medium, catalase is not stable in the plasma medium even without the addition of bacteria (Figure 6a). In the control groups, the plasma sample loses ∼60% of catalase activity within 2 days, and almost complete degradation happens after 5 days at 35 °C. If the storage temperature decreases, the reduction of catalase activity slows down. However, it still loses ∼50% of catalase activity within 4 days, and only ∼20% of catalase activity remains after 7 days at 22 °C. Even a low temperature such as 4 °C cannot entirely prevent the target species from inactivation, and it shows a slight decrease in catalase activity after 7 days of storage. The inactivation of catalase may be caused by aggregations or interactions between catalase with components in the bovine plasma such as serum albumins, globulins, and fibrinogen.49,50 In contrast, the PSAP beads have been demonstrated to effectively extend the shelf life of catalase in the plasma medium. As shown in Figure 6b, the catalase stored inside the beads remains at higher than 90% activity at 22 °C or below even after 7 days. If the storage temperature is elevated to 35 °C, the normalized catalase activity decreases to ∼90% after 2 days, then keeps at 80% for 4 days, and eventually reduces to ∼65% after 7 days of storage. Although the inactivation mechanism for catalase in the plasma has not been investigated yet, a possible explanation for the shelf life extension in the PSAP beads might be that the substance transportation and diffusion are limited in the water channels inside the bead, thus the lower contact probability of target species with other plasma components results in a lower inactivation. But once the temperature is higher than a critical level, with accelerated molecular mobility, the polymer network will gradually lose its function as a physical barrier and cannot protect prospective target species from potential inactivation. To further extend the shelf life of analytical targets in the PSAP beads, synthetic, integration, and post-treatment strategies can be applied to inhibit or reduce the target degradation or inactivation (e.g., preload stabilizers in the beads, or dry the beads together with targets).18,22

Figure 6.

Shelf life extension of catalase in the plasma medium by microfiltration treatment. (a) Catalase activity in the liquid control during the 7-day storage at 4, 22, or 35 °C. The dashed line in a indicates no active catalase is detected in the spectrophotometric assay. (b) Catalase activity in the hydrated PSAP beads after microfiltration treatment during the 7-day storage at 4, 22, or 35 °C.

In summary, we have successfully developed low-cost, well-designed, and scalable PSAP beads for biofluid specimen processing and storage. The PSAP beads can achieve fast and effective microfiltration among target species of different sizes. The key to the success of this microfiltration treatment is the pore structure control and swelling capacity improvement of the PSAP beads. Based on the rational design, we demonstrate centrifuge-free separation, pipet-free aliquoting, and refrigeration-free storage of biofluid samples using the PSAP beads. It takes only 5 min for the beads prepared with 10 wt % PEG to exclude ∼90% of bacteria in the saline or 40 min for these beads to exclude >80% of red blood cells in the blood. Since the synthesized beads have uniform size and constant swelling ability, the biofluid together with prospective target species is aliquoted into each bead spontaneously and simultaneously. The timely removal of blood cells from potential-target-containing plasma eliminated the adverse impacts caused by in vitro hemolysis during sample storage and transportation. In addition, removing blood cells from the samples significantly reduces sample volume/weight and decreases the transport burden. Meanwhile, the microbial spoilage and the influence of microbial activities on the shelf life of target species are avoided even at an evaluated temperature after the microfiltration treatment. Due to the limitation of mass transportation and diffusion in the hydrated PSAP beads, inactivation or degradation of sensitive target species is slowed down, leading to further extended shelf life. Although the microfiltration for biofluid specimen processing and storage remains to be investigated under varying conditions, the reported results show that the PSAP beads can potentially provide an alternative method for point-of-use biofluid stabilization in resource-limited settings.

Experimental Section

Preparation of PSAP Beads

To prepare PSAP beads, a reaction mixture containing 4 wt % acrylamide (AM), 6 wt % sodium acrylate (SA), 10 wt % poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG, average Mn = 6000 g mol–1), and 0.2 wt % N,N′-methylenebis(acrylamide) (MBA) in DI water was prepared and ultrasonicated until fully dissolved. After being degassed by nitrogen bubbling for 5 min, the aqueous solution was added to 0.3 wt % ammonium persulfate (APS) and mixed well. An aliquot of 15 μL of the reaction mixture was transferred to each well of a 96-well plate, and the plate was sealed with an aluminum film and then placed into a bath heater (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA) for 15 min at 70 °C (Figure S1). The resultant polymer beads were thoroughly washed with ethanol to remove the porogen, PEG, and fully dehydrated in a 60 °C oven.

Material Characterization

The morphology of dried PSAP beads was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi SU8230, Tokyo, Japan) at 3 kV. The specimens were coated with gold for 10 s at 20 mA using a sputter coater (Quorum Q150T ES, Lewes, United Kingdom). The pore structure characteristic parameters of the as-prepared PSAP beads were determined by mercury intrusion porosimetry (MIP, Micromeritics Autopore IV, Norcross, GA). The swelling process of the PSAP beads in liquid media was monitored under a digital microscope (Dino-Lite AM73915, Torrance, CA), in which both the diameter and weight of the swollen gel were measured to calculate the normalized diameter (dnormalized = dswollen/ddried) and weight swelling ratio (S = (mswollen – mdried)/mdried), respectively.

Microfiltration Performance Test

The performance of the PSAP beads prepared with varying PEG contents (2.5 to 20 wt %) for microfiltration was demonstrated using catalase and Escherichia coli (E. coli, ATCC 10798). A typical microfiltration treatment, illustrated in Figure S5a, was performed as follows: (i) PSAP beads were preloaded in sample tube with a sieve on top. (ii) A liquid sample was collected and infused into the tube. (iii) PSAP beads absorbed water together with analytical targets but excluded undesired larger components. (iv) The leftover liquid was poured out, keeping only the hydrated PSAP beads with the captured analytical targets in the tube. (v) The sieve was removed and put on a lid for storage. The liquid sample of catalase or E. coli in the saline medium (i.e., 0.9% NaCl solution) was prepared (see Supporting Information 1.2). The original dosage was ∼800 U mL–1 for catalase or ∼500 CFU mL–1 for E. coli. In general, 10 of the dry beads were applied to treat 1 mL of the liquid sample. After the microfiltration treatment, to extract small target species (i.e., catalase) from the hydrated beads, the beads were immersed in added DI water and then broken by 5 s of ultrasonication using a probe sonicator (Qsonica Q125, Newtown, CT) at 75% amplitude (Figure S5b). The activity of the released catalase in the well-dispersed suspension with polymer debris was measured using a UV spectrophotometric method and compared to the original activity to determine the recovery efficiency for catalase (see Supporting Information 1.2 and 1.3).51 For large components (i.e., E. coli) excluded by the PSAP beads, the bacterial concentration in the residual liquid after the microfiltration treatment was quantified by standard spread plating techniques to calculate the rejection efficiency for E. coli (see Supporting Information 1.3).52

Distribution of Target Species in Hydrated PSAP Beads

Imaging and analysis of the target species absorbed or adsorbed by the hydrated PSAP beads after the microfiltration treatment were performed with a fluorescence microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). The PSAP beads were applied to treat a saline medium containing 0.1 or 2 μm fluorescent latex microspheres as model targets (0.25 mg mL–1, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). After the treatment, the PSAP beads were cut in half, and the fluorescent targets on the cross sections of the beads were imaged by fluorescence microscopy using a 63× objective lens together with a charge-coupled device camera. For each PSAP bead, the fluorescent images at different locations of the cross-section (40 images in total) were integrated to provide a two-dimensional mapping of individual fluorescent targets. The integrated image was then divided into columns and processed to analyze the change of fluorescence intensity from the edge to the core of the bead, in which the maximum fluorescence intensity at the bead edge was set as a baseline and intensities at different distances were normalized to the baseline.

Microfiltration Performance with Biofluid Samples

The synthetic urine medium was prepared with urea and minerals (full composition listed in Table S2).53 The bovine plasma and bovine blood stabilized with citrate were purchased from Hardy Diagnostics (Santa Maria, CA) and used within the quality guarantee period. All three biofluid media were stored at 4 °C before use. Both the swelling kinetics and swelling ratio of the PSAP beads in each biofluid medium at room temperature were measured, respectively. For microfiltration performance tests, the PSAP beads were applied to treat biofluid samples with target species such as glucose, catalase, or bacteriophage MS2 (ATCC 15597-B1). After the treatment, the target species captured by the hydrated PSAP beads were then released by ultrasonication and characterized to analyze recovery efficiency for each target species (details of sample preparation and characterization described in Supporting Information 1.2). For cell exclusion in bovine blood treatment, catalase was used as an indicator for red blood cells since it only existed in the red blood cells. The catalase activities, which correspond to the red blood cell concentrations, in the original blood sample and the blood sample after the microfiltration treatment were measured to analyze the cell rejection efficiency (similar to the rejection efficiency calculation for E. coli). In addition, the PSAP beads after the treatment were cut in half, and their cross sections were imaged by microscopy.

Shelf Life in Saline under Bacterial Contamination

The shelf life of catalase was first measured in a saline medium, which contained nutrient broth (10 mg mL–1) to support bacterial growth. Catalase powder was dissolved in the above medium to achieve a concentration of 0.5 mg mL–1, corresponding to an activity of ∼1000 U mL–1. The catalase solution was then filtered via 0.2 μm syringe filter to remove any undissolved aggregates or potential microorganisms. Bacillus subtilis (B. subtilis, ATCC 6051) was cultured in nutrient broth to the log phase (35 °C overnight) and then dosed to the catalase solution (∼50 CFU mL–1 dosage). After preparing the liquid sample, 0.3 g of the PSAP beads (∼300 beads) were applied to treat 30 mL of the sample for 5 min, which were then separated from the liquid and divided into three glass vials (5 g hydrated PSAP beads for each group). The three vials were stored at three temperatures, 4 °C, room temperature (22 ± 1 °C), and 35 °C, respectively. Meanwhile, another three vials, each containing 5 mL of catalase sample dosed with B. subtilis, were also stored at 4 to 35 °C as control groups. After a certain storage time, five of the hydrated PSAP beads were taken out from each vial for catalase activity measurement and recovery efficiency analysis. In addition, 0.5 mL of the liquid from each control was sampled to detect the remaining catalase activity together with the bacterial concentration. All catalase activity data collected, including both the control groups and PSAP groups, were normalized to the initial baseline value of catalase activity in the liquid control at each temperature, respectively.

Shelf Life in Blood Plasma Medium

The catalase stock solution was prepared by dissolving catalase powder in saline solution (5 mg mL–1) and then filtered using a 0.2 μm syringe filter. Then, the catalase stock was directly dosed to bovine plasma medium at a 10 times diluted concentration. After that, the PSAP beads were applied to treat the liquid sample (similar to the shelf life study in the saline medium except for the treatment time in the plasma medium is 30 min). The activity of catalase inside the hydrated PSAP beads and in the liquid control was investigated along the storage time.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ryan P. Lively and Conrad J. Roos for assistance conducting mercury intrusion porosimetry tests. We thank Dr. Wilbur A. Lam and Dr. Elaissa Hardy for helpful technical discussions about blood sample handling. W.C. and T.W. are grateful for the fellowship provided by the China Scholarship Council.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00348.

Experimental methods for preparation and characterization of biofluid samples, optimization process for the PSAP synthesis, more optical and SEM images of the PSAP beads, bead swelling behaviors, schematic of microfiltration and recovery operations, and fluorescent images of target distribution near the bead interface (PDF)

Author Contributions

W.C. and X.X. conceived and designed the experiments. W.C. performed most of the experiments. T.W. helped on fluorescent microscope imaging. Z.D. assisted in the swelling kinetics test. The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

This study is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation via Award OPP1191082.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- World Health Organization , World health statistics 2019: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. 2019.

- Finnie R. K.; Khoza L. B.; van den Borne B.; Mabunda T.; Abotchie P.; Mullen P. D. Factors associated with patient and health care system delay in diagnosis and treatment for TB in sub-Saharan African countries with high burdens of TB and HIV. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2011, 16, 394–411. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galactionova K.; Tediosi F.; De Savigny D.; Smith T.; Tanner M. Effective coverage and systems effectiveness for malaria case management in sub-Saharan African countries. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0127818. 10.1371/journal.pone.0127818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaens G. J.; Bousema T.; Leslie T. Scale-up of malaria rapid diagnostic tests and artemisinin-based combination therapy: challenges and perspectives in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS medicine 2014, 11, e1001590. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J.; Livesey J. H.; Ellis M. J.; Yandle T. G. Effect of anticoagulants and storage temperatures on stability of plasma and serum hormones. Clin. Biochem. 2001, 34, 107–112. 10.1016/S0009-9120(01)00196-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L.-H.; Lin P.-H.; Tsai K.-W.; Wang L.-J.; Huang Y.-H.; Kuo H.-C.; Li S.-C. The effects of storage temperature and duration of blood samples on DNA and RNA qualities. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0184692. 10.1371/journal.pone.0184692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G.; Blanckaert N.; Bonini P.; Green S.; Kitchen S.; Palicka V.; Vassault A. J.; Plebani M. Haemolysis: an overview of the leading cause of unsuitable specimens in clinical laboratories. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2008, 46, 764–772. 10.1515/CCLM.2008.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippi G.; Plebani M.; Di Somma S.; Cervellin G. Hemolyzed specimens: a major challenge for emergency departments and clinical laboratories. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2011, 48, 143–153. 10.3109/10408363.2011.600228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heireman L.; Van Geel P.; Musger L.; Heylen E.; Uyttenbroeck W.; Mahieu B. Causes, consequences and management of sample hemolysis in the clinical laboratory. Clin. Biochem. 2017, 50, 1317–1322. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaigneau C.; Cabioch T.; Beaumont K.; Betsou F. Serum biobank certification and the establishment of quality controls for biological fluids: examples of serum biomarker stability after temperature variation. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2007, 45, 1390–1395. 10.1515/CCLM.2007.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najat D. Prevalence of pre-analytical errors in clinical chemistry diagnostic labs in Sulaimani city of Iraqi Kurdistan. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0170211. 10.1371/journal.pone.0170211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer B.; Reller L.; Mirrett S. Evaluation of preservative fluid for urine collected for culture. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1979, 10, 42–45. 10.1128/JCM.10.1.42-45.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honour J. W. Testing for drug abuse. Lancet 1996, 348, 41–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)05336-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie T.; Fewster J.; Masterton R. The effect of specimen processing delay on borate urine preservation. J. Clin. Pathol. 1999, 52, 95–98. 10.1136/jcp.52.2.95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareck U.; Geyer H.; Opfermann G.; Thevis M.; Schänzer W. Factors influencing the steroid profile in doping control analysis. J. Mass Spectrom. 2008, 43, 877–891. 10.1002/jms.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsivou M.; Livadara D.; Georgakopoulos D.; Koupparis M.; Atta-Politou J.; Georgakopoulos C. Stabilization of human urine doping control samples: II. Microbial degradation of steroids. Anal. Biochem. 2009, 388, 146–154. 10.1016/j.ab.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam B.; Hall E.; Sternberg M.; Lim T.; Flores S.; O’brien S.; Simms D.; Li L.; De Jesus V.; Hannon W. The stability of markers in dried-blood spots for recommended newborn screening disorders in the United States. Clin. Biochem. 2011, 44, 1445–1450. 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2011.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon D. E.; Yin M.; Allen D. M.; Maher Y. S.; Tanny C. J.; Oyola-Reynoso S.; Smith B. L.; Maher S.; Thuo M. M.; Badu-Tawiah A. K. Dried blood spheroids for dry-state room temperature stabilization of microliter blood samples. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 9353–9358. 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b01962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Less R.; Boylan K. L.; Skubitz A. P.; Aksan A. Isothermal vitrification methodology development for non-cryogenic storage of archival human sera. Cryobiology 2013, 66, 176–185. 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2013.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakaltcheva I.; O’Sullivan A. M.; Hmel P.; Ogbu H. Freeze-dried whole plasma: evaluating sucrose, trehalose, sorbitol, mannitol and glycine as stabilizers. Thromb. Res. 2007, 120, 105–116. 10.1016/j.thromres.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S.; Wang X.; Lu Q.; Hu X.; Uppal N.; Omenetto F. G.; Kaplan D. L. Stabilization of enzymes in silk films. Biomacromolecules 2009, 10, 1032–1042. 10.1021/bm800956n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kluge J. A.; Li A. B.; Kahn B. T.; Michaud D. S.; Omenetto F. G.; Kaplan D. L. Silk-based blood stabilization for diagnostics. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2016, 113, 5892–5897. 10.1073/pnas.1602493113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Sun H.; Luan J.; Jiang Q.; Tadepalli S.; Morrissey J. J.; Kharasch E. D.; Singamaneni S. Metal–organic framework encapsulation for biospecimen preservation. Chem. Mater. 2018, 30, 1291–1300. 10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b04713. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhamla M. S.; Benson B.; Chai C.; Katsikis G.; Johri A.; Prakash M. Hand-powered ultralow-cost paper centrifuge. Nature Biomedical Engineering 2017, 1, 1–7. 10.1038/s41551-016-0009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong A. P.; Gupta M.; Shevkoplyas S. S.; Whitesides G. M. Egg beater as centrifuge: isolating human blood plasma from whole blood in resource-poor settings. Lab Chip 2008, 8, 2032–2037. 10.1039/b809830c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan S.; Tan S. H.; Li Y.; Tang S.; Teo A. J. T.; Zhang J.; Zhao Q.; Yuan D.; Sluyter R.; Nguyen N. T.; Li W. A portable, hand-powered microfluidic device for sorting of biological particles. Microfluid. Nanofluid. 2018, 22, 8. 10.1007/s10404-017-2026-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ono T.; Sugimoto T.; Shinkai S.; Sada K. Lipophilic polyelectrolyte gels as super-absorbent polymers for nonpolar organic solvents. Nat. Mater. 2007, 6, 429–433. 10.1038/nmat1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L.; Yang Y.; Chen Z.; Guo C.; Li S. Influence of super absorbent polymer on soil water retention, seed germination and plant survivals for rocky slopes eco-engineering. Ecological Engineering 2014, 62, 27–32. 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2013.10.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. B.; Zhang Y.; Won S. M.; Bandodkar A. J.; Sekine Y.; Xue Y.; Koo J.; Harshman S. W.; Martin J. A.; Park J. M.; Ray T. R.; Crawford K. E.; Lee K.-T.; Choi J.; Pitsch R. L.; Grigsby C. C.; Strang A. J.; Chen Y.-Y.; Xu S.; Kim J.; Koh A.; Ha J. S.; Huang Y.; Kim S. W.; Rogers J. A. Super-absorbent polymer valves and colorimetric chemistries for time-sequenced discrete sampling and chloride analysis of sweat via skin-mounted soft microfluidics. Small 2018, 14, 1703334. 10.1002/smll.201703334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Z.; Wang T.; Chen W.; Lin B.; Dong H.; Sun W.; Xie X. Self-driven membrane filtration by core–shell polymer composites. J. Mater. Chem. A 2020, 8, 15942–15950. 10.1039/D0TA03617J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie X.; Bahnemann J.; Wang S.; Yang Y.; Hoffmann M. R. Nanofiltration” enabled by super-absorbent polymer beads for concentrating microorganisms in water samples. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 20516. 10.1038/srep20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokmen M. T.; Du Prez F. E. Porous polymer particles—A comprehensive guide to synthesis, characterization, functionalization and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2012, 37, 365–405. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2011.07.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Bae J.; Fang Z.; Li P.; Zhao F.; Yu G. Hydrogels and Hydrogel-Derived Materials for Energy and Water Sustainability. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120, 7642–7707. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.0c00345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X.; Lu H.; Zhao F.; Yu G. Atmospheric Water Harvesting: A Review of Material and Structural Designs. ACS Materials Letters 2020, 2, 671–684. 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Entezari A.; Ejeian M.; Wang R. Super Atmospheric Water Harvesting Hydrogel with Alginate Chains Modified with Binary Salts. ACS Materials Letters 2020, 2, 471–477. 10.1021/acsmaterialslett.9b00315. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y.; Lu H.; Zhao F.; Zhou X.; Shi W.; Yu G. Biomass-Derived Hybrid Hydrogel Evaporators for Cost-Effective Solar Water Purification. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, 1907061. 10.1002/adma.201907061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Mooney D. J. Designing hydrogels for controlled drug delivery. Nature Reviews Materials 2016, 1, 1–17. 10.1038/natrevmats.2016.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezwan K.; Chen Q.; Blaker J. J.; Boccaccini A. R. Biodegradable and bioactive porous polymer/inorganic composite scaffolds for bone tissue engineering. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 3413–3431. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An D.; Ji Y.; Chiu A.; Lu Y.-C.; Song W.; Zhai L.; Qi L.; Luo D.; Ma M. Developing robust, hydrogel-based, nanofiber-enabled encapsulation devices (NEEDs) for cell therapies. Biomaterials 2015, 37, 40–48. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F.; Shi Y.; Pan L.; Yu G. Multifunctional nanostructured conductive polymer gels: synthesis, properties, and applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017, 50, 1734–1743. 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y.; Wang H.; Luan C.; Fu F.; Chen B.; Liu H.; Zhao Y. Porous hydrogel encapsulated photonic barcodes for multiplex microRNA quantification. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2018, 28, 1704458. 10.1002/adfm.201704458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y.; Liu Y.; Zhang H.; Zou M.; Yan D.; Chen D.; Zhao Y. A responsive porous hydrogel particle-based delivery system for oncotherapy. Nanoscale 2019, 11, 2687–2693. 10.1039/C8NR09990A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Yao T.; Ji X.; Zeng C.; Wang C.; Zhang L. Versatile preparation of nonspherical multiple hydrogel core PAM/PEG emulsions and hierarchical hydrogel microarchitectures. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7504–7509. 10.1002/anie.201403256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S.; Yao T.; Wang C.; Zeng C.; Zhang L. Preparation of monodispersed porous polyacrylamide microspheres via phase separation in microchannels. React. Funct. Polym. 2015, 91, 77–84. 10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2015.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandro A.; Liumbruno G.; Grazzini G.; Zolla L. Red blood cell storage: the story so far. Blood Transfusion 2010, 8, 82. 10.2450/2009.0122-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mäntsälä P.; Zalkin H. Extracellular and membrane-bound proteases from Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1980, 141, 493–501. 10.1128/JB.141.2.493-501.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewen P. C.; Switala J. Multiple catalases in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 3601–3607. 10.1128/JB.169.8.3601-3607.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Feng M.; Zhao Y.; Guo X.; Zhou P. Overexpression, purification and characterization of a recombinant secretary catalase from Bacillus subtilis. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 30, 181–186. 10.1007/s10529-007-9510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raeker M.; Johnson L. Thermal and functional properties of bovine blood plasma and egg white proteins. J. Food Sci. 1995, 60, 685–690. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1995.tb06206.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva V. D.; Silvestre M. P. Functional properties of bovine blood plasma intended for use as a functional ingredient in human food. LWT-Food Science and Technology 2003, 36, 709–718. 10.1016/S0023-6438(03)00092-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aebi H.Catalase. In Methods of Enzymatic Analysis; Elsevier, 1974; pp 673–684. [Google Scholar]

- Chen W.; Jiang J.; Zhang W.; Wang T.; Zhou J.; Huang C.-H.; Xie X. Silver Nanowire-Modified Filter with Controllable Silver Ion Release for Point-of-Use Disinfection. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7504–7512. 10.1021/acs.est.9b01678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray H.; Perreault F.; Boyer T. H. Urea recovery from fresh human urine by forward osmosis and membrane distillation (FO–MD). Environmental Science: Water Research & Technology 2019, 5, 1993–2003. 10.1039/C9EW00720B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.