To the Editor:

Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) is a high-risk procedure in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) because of aerosol generated by the procedure (1). Decisions to perform a PDT in critically ill SARS-CoV-2 patients should not be taken lightly, balancing the risks and burdens to both patients and healthcare providers. When a PDT is necessary, multiple precautions should be considered, including personal protection equipment (PPE) before, during, and after the procedure as well as place, technique, and capacitated personnel (2–5). We aimed to compare four PDT techniques to assess aerosol spillage before and after the procedure.

We utilized a simulated setting to test these techniques, which included an airway mannequin (AirSim Advance X; TruCorp), a ventilator (Dräger Evita XL; Drägerwerk AG), a PDT (Ciaglia Blue Rhino G2; Cook Medical), standard PPE, and a glow substance (fluorescent dye consisting of GlowGerm and tonic water). We assessed the pre- and postprocedural aerosol spillage in every single procedure using this mixture. Aerosolization was simulated by connecting an 8 L/min flow oxygen humidifier with 2 ml of GlowGerm and 8 ml of tonic water to the main bronchus end of the mannequin. We performed a conventional PDT technique, a conventional PDT technique with intermittent expiratory ventilator pause (IEVP), and a modified PDT technique with and without a customized acrylic box (see Video E1 in the online supplement). In the modified PDT technique developed by Angel and colleagues, the bronchoscope is passed along the side of the endotracheal tube (ETT) and under direct bronchoscopic guidance; the ETT is then advanced to the distal trachea, allowing the patient to be ventilated until the creation of a stoma. Afterward, the ETT is pulled back to the conus elasticus while the ventilation is on hold, and then the tracheostomy tube is advanced into the airway under direct bronchoscopic guidance (6). The acrylic box was customized to allow the bronchoscopist and the proceduralist to perform the procedure in a comfortable manner while having an additional PPE barrier. The anterior face of the box was designed for the bronchoscopist’s hands and scope, whereas the lateral face of the box was designed with two orifices for the proceduralist’s hands (Figure 1). Each technique was previously tested two times by the same experienced bronchoscopist and proceduralist with the same simulated model before testing them with the glow substance. To create a baseline, we recorded the operator’s face, chest, and hands (dorsal and palmar), the mannequin’s head and neck, and PDT equipment before and after using a 395 nm ultraviolet light–emitting lantern (Figure 2). Postprocedural spillage was qualitatively recorded and compared after each procedure. Total procedural and expiratory ventilatory pause times were also recorded.

Figure 1.

(A) Box specifications: 21.65 in (55 cm) width × 19.7 in (50 cm) length × 19.7 in (50 cm) height. Frontal face: two ports of 4.7 in (12 cm) in diameter and a port for bronchoscope of 1.2 in (3 cm) in diameter. Lateral face: one port of 4.7 in (12 cm) in diameter and 8.7 in (22 cm) length × 4.7 in (12 cm) height elliptical opening for proceduralist. Ventilation circuit port: 7.9 in (20 cm) length × 3.9 in (10 cm) height. (B) Acrylic box during simulation.

Figure 2.

(A) Simulated setting with mannequin, percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy tools, and ventilator. (B) Customized acrylic box. (C and D) Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy tools and mannequin under ultraviolet light. (E) Baseline operator’s face, chest, and hands under ultraviolet light.

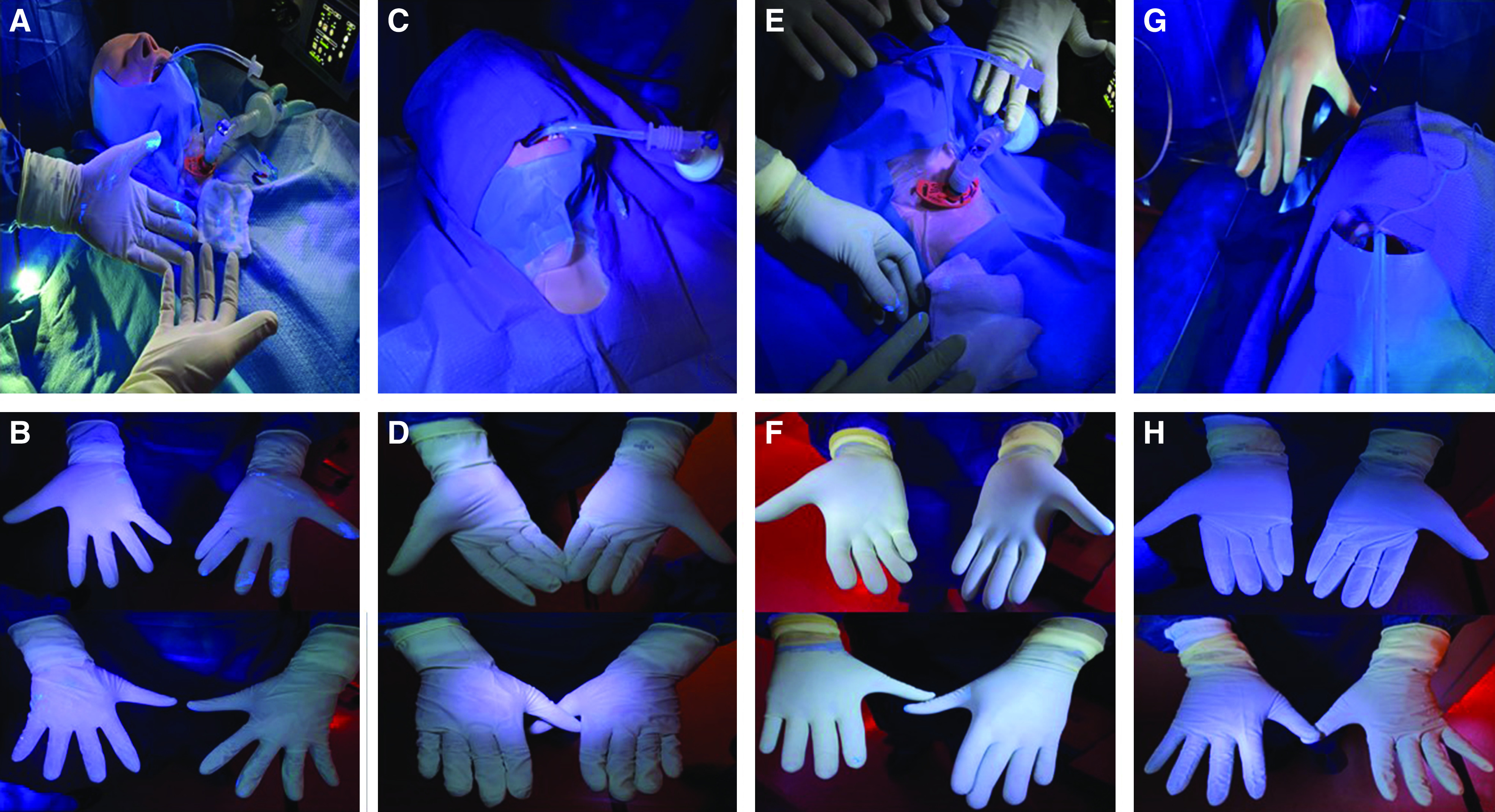

We found that considerable contamination was noticeable after the conventional PDT technique, including on the operator’s hands and chest as well as on the mannequin’s mouth, neck, and adjacent surgical drapes, as compared with all other techniques with IEVP (Figure 3). The modified PDT technique with the customized acrylic box showed a few minuscule glowing particles at the top of the box. Total procedural time for the standard technique, standard technique with IEVP, modified technique, and the modified technique using the acrylic box were 167, 171, 198, and 206 seconds, respectively. Expiratory ventilatory pause times for the standard technique with IEVP, the modified technique, and the modified technique with the acrylic box were 100, 71, and 78 seconds, respectively.

Figure 3.

(A and B) Conventional percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) postprocedural contamination. (C and D) Conventional PDT with intermittent expiratory ventilator pause postprocedural contamination. (E and F) Modified PDT technique without acrylic box postprocedural contamination. (G and H) Modified PDT technique with acrylic box postprocedural contamination.

Our results show that an IEVP (when the circuit is opened) reduces the amount of airway spillage and subsequent contamination. In addition, use of the modified technique decreases the duration of the expiratory ventilator, which may be clinically significant in patients with severe hypoxemia. However, we admit that the modified technique could potentially encounter technical difficulties, especially when inserting the dilator concomitantly with the ETT. Although the bronchoscopic view clearly reflects a lack of space while inserting the dilator, this has not been an issue in real clinical scenarios when this technique has been recently published (6). Finally, we showed that a customized aerosol box can be used when performing a PDT on a mannequin and may represent an additional protection to the operator from unperceivable particles expelled during the procedure.

Although our model might simulate a real setting, our aerosolization method could not identify very small quantities of particles that could be infectious in a real clinical setting. However, our study suggests that PDT in patients infected with SARS-CoV-2 should be performed with IEVP. The use of a modified technique and acrylic box may have some clinical advantages, but additional clinical studies are needed to confirm.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Mike McBride and Darren Tavernelli from the Carl J. Shapiro Simulation Center at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.

Footnotes

This letter has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this letter at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meng L, Qiu H, Wan L, Ai Y, Xue Z, Guo Q, et al. Intubation and ventilation amid the COVID-19 outbreak: Wuhan’s experience. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1317–1332. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heinzerling A, Stuckey MJ, Scheuer T, Xu K, Perkins KM, Resseger H, et al. Transmission of COVID-19 to health care personnel during exposures to a hospitalized patient - Solano County, California, February 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:472–476. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xiao H, Zhong Y, Zhang X, Cai F, Varvares MA. How to avoid nosocomial spread during tracheostomy for Covid-19 patients. Head Neck. 2020;42:1280–1281. doi: 10.1002/hed.26167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenland JR, Michelow MD, Wang L, London MJ. COVID-19 infection: implications for perioperative and critical care physicians. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1346–1361. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angel L, Kon ZN, Chang SH, Rafeq S, Shekar SP, Mitzman B.et al. Novel percutaneous tracheostomy for critically ill patients with COVID-19 Ann Thorac Surg [online ahead of print] 25 Apr 2020; DOI: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.