Abstract

Objectives

We aim to describe time trends of severe sports-related emergency department (ED) visits in the Netherlands, from 2009 to 2018.

Methods

Data were extracted from the Dutch Injury Surveillance System by age, gender, sports activity and injury diagnosis, from 2009 to 2018. Absolute numbers and time trends of severe sports-related ED visits were calculated.

Results

Between 2009 and 2018, the overall numbers of severe sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands have significantly decreased by 14% (95% CI −19% to −9%). This trend was seen among men (−12%; 95% CI −18% to −6%), women (−19%; 95% CI −26% to −11%) and individuals aged 18–34 years (−19%; 95% CI −28% to −10%). The number of ED visits has significantly decreased over time in soccer (−15%; 95% CI −24% to −6%), ice-skating (−80%; 95% CI −85% to −73%) and in inline/roller skating (−38%; 95% CI −55% to −15%). This was not the case in road cycle racing (+135%; 95% CI +85% to +198%) and mountain bike racing (+80%; 95% CI +32% to+146%). In terms of sports injury diagnoses, the number of fractured wrists (−15%; 95% CI −24% to −5%), fractured hands (−37%; 95% CI −49% to −21%), knee distortions (−66%; 95% CI −74% to −55%), and fractured lower legs (−38%; 95% CI −55% to −14%) significantly decreased over time.

Conclusion

Our study shows a promising reduction in the number of severe sports-related ED visits across most age groups and sports activities. As the number of ED visits increased in road cycle and mountain bike racing, it is important to find out what caused these increases. Furthermore, it is essential to determine trends in exposure hours and to evaluate and implement injury prevention programmes specific for these sports activities.

Keywords: Sporting injuries, Epidemiology, Public health

INTRODUCTION

Even though maintaining a physically active lifestyle through sports has many health benefits,1 sports activities also entail a risk for injury among both the youth and adults.2 These sports injuries have a major financial impact, with an estimated annual societal cost of €3 billion in the Netherlands.3 In addition to the economic impact, sports injuries affect an individual’s physical and psychosocial well-being.4 Prevention of sports-related injuries is therefore warranted.

To understand emerging sports injury trends and guide policy development aimed at preventive efforts, it is important to monitor and describe nationwide trends of sports injuries over time.5 A commonly used source used to monitor and describe nationwide sports injuries over time is emergency department (ED) visits. Studies on trends of sports-related ED visits have been performed in several countries. For example, a study performed in the USA has shown that the number of sports-related ED visits increased among children between 2001 and 2013.6 Furthermore, an Australian study has shown that the number of sports-related ED visits and hospital admissions increased among individuals aged >15 years, between 2004 and 2010.7 Both studies emphasise that additional research that monitors and describes time trends of sports-related ED visits is essential to reduce the burden of sports injuries.

In the Netherlands, many individuals with severe sports-related injuries visit the ED. However, a study describing the nationwide trends in these severe sports-related ED visits has not been performed to date. Thus, the aim of this study was to describe time trends of severe sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands, by gender, age group, sports activity and injury diagnosis, from 2009 to 2018.

METHODS

Data source

Sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands were extracted from the Dutch Injury Surveillance System (DISS). The DISS data set is composed of a representative sample of injuries treated at 14 geographically distributed EDs in the Netherlands since 1986.8 Despite the availability of the DISS data set since 1986, in the current study, data are used from 2009 until 2018. This time period was chosen as it represents the current state of affairs in the field of nationwide sports injuries, which in turn can guide current policy development, aimed at preventative efforts. The DISS data set represents 16% of all EDs in the Netherlands and includes general and academic hospitals that provide emergency services 24 hours a day. When a patient visits one of the participating EDs, an employee of the ED (eg, a doctor or nurse) registers the basic data in an administrative system.

When the patient requires treatment for an injury, detailed information about the circumstances of the accident is recorded. In this process, it is determined whether the injury was caused while taking part in a sport, where sport is defined as physical activity which is practised within an organised or unorganised setting, such as competitive or recreational sport.9 All data on injuries that are registered by the EDs are provided anonymously to VeiligheidNL (VNL), and records are converted—by a data manager—into uniform codes and variables. In the case of open text fields, conversion is carried out by means of automatic text recognition. A random check is performed manually on the data to determine whether the data conversions were performed correctly.

Because VNL is an organisation that conducts scientific research, an appeal can be made to the exemption clause of the Medical Treatment Contracts Act (WGBO) for the use of patients’ medical data for scientific research (Article 7: 458 of the Dutch Civil Code). Therefore, no explicit consent of patients was needed (Article 7: 457 of the Dutch Civil Code). Patients were informed about the existence of the surveillance system, and about the possibility to object to the inclusion of their data in the surveillance system.

The sample of 14 EDs can be extrapolated to nationwide estimates, while the age distribution, the type of hospital and other demographics are representative of all EDs in the Netherlands.10 11–13 An extrapolation factor was calculated as follows: (No. of ED visits in the sample×No. hospital admissions in all hospitals)/No. of hospital admission in the sample.14

Severe injury

In the Netherlands, minor injuries are often treated by a general practitioner during same-day visits. Furthermore, minor (overload) injuries are often treated at a physiotherapy centre (without a medical referral). Outside working hours, patients can be treated at a general practice centre, usually situated in a hospital. Severe injuries are often treated at an ED, which can be visited all hours of the day and is situated in a hospital. In the past 10 years, new policies have been adopted in the Netherlands aimed at improving the efficiency of emergency care. This has resulted in minor injuries being treated even more often outside EDs by the general practitioner, whereas severe injuries are still treated in the EDs.10 As minor injuries were more likely to be treated outside EDs, it was decided in the current study to only report the number of severe sports-related ED visits from the DISS data set that were treated between 2009 and 2018. It is assumed that, by doing this, a more reliable description of the incidence of sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands can be provided.

To select the severe sports-related ED visits, a derivative of the Maximum Abbreviated Injury Scale (MAIS) was used.15 The score on this scale runs from 1 (minor) to 6 (maximum) and represents the severity of the injury.16 A MAIS score was generated for the injuries in DISS by transforming 39 injury groups to corresponding categories in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision.17 An overview of the MAIS classification of injury diagnoses is presented in online supplemental table S1. In the current study, severe injury is defined as one with a MAIS score of at least 2.18

bmjsem-2020-000811s001.pdf (150.9KB, pdf)

Data analysis

The absolute numbers and time trends of severe sports-related ED visits were specified for age, gender, sports activity and injury diagnosis for each individual year from 2009 to 2018. As the ED data were extrapolated, all absolute numbers were rounded to the nearest integer. In addition, 95% CIs were calculated. For the calculation of time trends, absolute numbers of injuries were standardised by correcting for changes in population composition between 2009 and 2018. Standardisation was performed by direct standardisation, in which one weight was applied to all age-specific rates, irrespective of the age distribution of the population.19 Data on changes in population composition were obtained from Statistics Netherlands.20

Injuries were specified for the following age groups: 0–17, 18–34, 35–54 and ≥55 years. These age groups are conventional within the DISS data set. In general, the agroup 0–17 years represents youth athletes, 18–34 years represents senior athletes, 35–54 years represents master athletes, and ≥55 years represents elderly athletes.

In the DISS data set, a total of 65 sports activities are coded (online supplemental table S2). Sports activities averaging less than 500 severe sports-related ED visits a year (between 2009 and 2018) were not included in the current analyses. This cut-off was applied as the ED data were extrapolated, resulting in sports activities with less than 500 ED visits a year being less representative for the Netherlands. Therefore, only the following sports activities were included: basketball, combat sports, field hockey, fitness, futsal, gymnastics, horse riding, ice-skating, inline/roller skating, motorcycle racing, mountain bike racing, physical education, road cycle racing, running, skateboarding, skiing, snowboarding, soccer, swimming, tennis and volleyball.

Severe sports-related injury diagnoses identified in the EDs less than 500 times a year (between 2009 and 2018) were not included in the current study either. Again, this cut-off was applied as the ED data were extrapolated, resulting in injury diagnoses identified less than 500 times a year being less representative for the Netherlands. Therefore, only the following severe sports-related injuries were included: knee distortion (ie, a dislocation, sprain, or strain of joint and ligaments of the knee), fractured ankle, fractured collarbone/shoulder, fractured elbow, fractured foot, fractured forearm, fractured hand, fractured hip, fractured knee, fractured lower leg, fractured ribs/chest, fractured spine/spinal cord injury, fractured upper arm, fractured wrist, knee luxation, mild traumatic brain injury, muscle/tendon injury in hand/finger, muscle/tendon injury in lower leg and severe traumatic brain injury.

To analyse the statistical significance of the trends over time, a logistic regression model was used. Both the linear and the quadratic association were tested based on standardised data, as the trend was corrected for changes in population composition between 2009 and 2018. A p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The absolute percentage of the change over time and the 95% CI are reported. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.

Patient and public involvement

This research was done without patient involvement. Patients were not invited to comment on the study design and were not consulted to develop patient-relevant outcomes or interpret the results. Patients were not invited to contribute to the writing or editing of this document for readability or accuracy.

RESULTS

Gender and age group

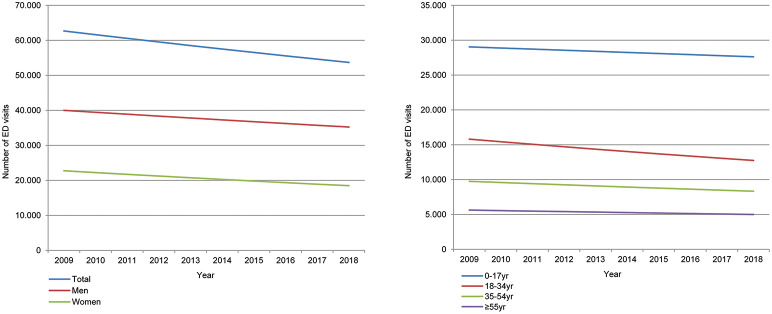

An overview of the absolute number of severe sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands from 2009 to 2018 is presented by gender and age group in table 1. Figure 1 presents the trends over time. The number of severe sports-related ED visits has significantly decreased by 14% (95% CI −19% to −9%). This was also the case among men (−12%; 95% CI −18% to −6%) and women (−19%; 95% CI −26% to −11%). Even though the number of ED visits decreased for all age groups between 2009 and 2018, a significant decrease was seen only among individuals aged 18–34 years (−19%; 95% CI −28% to −10%).

Table 1.

Absolute number and 95% CI of severe sports-related emergency department (ED) visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by gender and age group

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute number and 95% CI of ED visits, by gender | ||||||||||

| Total | 63 500 (58 900 to 68 200) |

56 900 (52 700 to 61 400) |

57 400 (52 900 to 62 000) |

62 800 (58 100 to 67 600) |

53 400 (49 200 to 57 800) |

55 600 (51 400 to 60 200) |

54 800 (50 500 to 59 200) |

53 200 (49 200 to 57 400) |

53 800 (49 800 to 57 900) |

56 900 (52 800 to 61 100) |

| Men | 39 900 (36 300 to 43 700) |

35 500 (32 200 to 39 100) |

37 800 (34 200 to 41 600) |

39 800 (36 100 to 43 600) |

35 100 (31 700 to 38 700) |

37 100 (33 600 to 40 800) |

35 800 (32 400 to 39 500) |

34 100 (30 900 to 37 500) |

34 900 (31 600 to 38 200) |

37 000 (33 700 to 40 400) |

| Women | 23 600 (20 800 to 26 500) |

21 400 (18 800 to 24 200) |

19 600 (17 000 to 22 300) |

23 000 (20 200 to 26 000) |

18 200 (15 800 to 20 900) |

18 500 (16 100 to 21 100) |

19 000 (16 500 to 21 600) |

19 100 (16 700 to 21 700) |

18 900 (16 600 to 21 400) |

19 900 (17 500 to 22 400) |

| Absolute number and 95% CIs of ED visits, by age group | ||||||||||

| 0–17 years | 29 900 (26 800 to 33 200) |

30 500 (27 400 to 33 700) |

29 700 (26 500 to 33 100) |

30 100 (26 900 to 33 500) |

27 200 (24 200 to 30 300) |

29 300 (26 200 to 32 600) |

29 000 (26 000 to 32 300) |

28 400 (25 500 to 31 500) |

27 600 (24 800 to 30 600) |

27 500 (24 700 to 30 500) |

| 18–34 years | 15 400 (13 200 to 17 800) |

13 500 (11 500 to 15 700) |

14 700 (12 500 to 17 200) |

15 300 (13 000 to 17 700) |

12 800 (10 800 to 15 000) |

13 200 (11 100 to 15 400) |

12 800 (10 800 to 15 000) |

12 100 (10 200 to 14 200) |

12 900 (11 000 to 14 900) |

13 800 (11 800 to 15 900) |

| 35–54 years | 12 400 (10 400 to 14 500) |

8900 (7300 to 7311 000) |

9100 (7300 to 7311 000) |

11 100 (9200 to 9213 100) |

8900 (7200 to 7210 700) |

9100 (7400 to 7410 900) |

8500 (6900 to 6910 300) |

8300 (6700 to 6710 000) |

8300 (6800 to 6810 000) |

9500 (7900 to 7911 300) |

| ≥55 years | 5800 (4500 to 7300) |

4000 (3000 to 5300) |

3800 (2700 to 5100) |

6300 (4900 to 7900) |

4500 (3300 to 5800) |

4100 (3000 to 5400) |

4400 (3300 to 5800) |

4400 (3300 to 5700) |

5000 (3800 to 6300) |

6000 (4700 to 7400) |

Figure 1.

Time trends of severe sports-related emergency department visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by gender and age group.

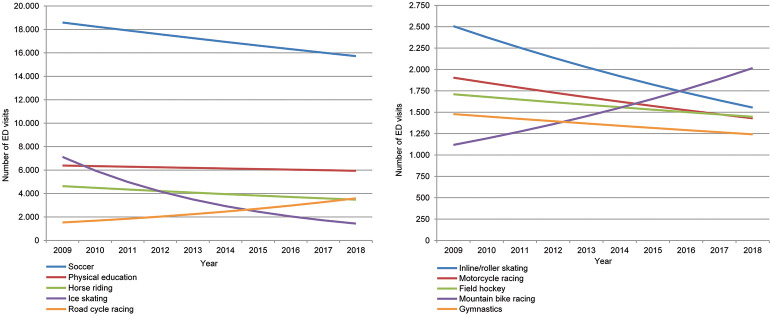

Sports activity

Table 2 presents the absolute number of severe sports-related ED visits, for the 10 sports activities with, on average, the highest number of ED visits (between 2009 and 2018). This includes soccer, physical education, horse riding, ice-skating, road cycle racing, inline/roller skating, motorcycle racing, field hockey, mountain bike racing and gymnastics. The time trends of these 10 sports activities are presented in figure 2. The number of severe sports-related ED visits has significantly decreased over time in soccer (−15%; 95% CI −24% to −6%), ice-skating (−80%; 95% CI −85% to −73%) and in inline/roller skating (−38%; 95% CI −55% to −15%). The number of ED visits has significantly increased over time in road cycle racing (+135%; 95% CI +85% to +198%) and in mountain bike racing (+80%; 95% CI +32% to +146%). The full data of the other 11 sports are provided in online supplemental table S3.

Table 2.

Absolute number and 95% CI of severe sports-related emergency department visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by sports activity (1–10)

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soccer | 17 800 (15 400 to 20 400) |

16 900 (14 600 to 19 400) |

18 300 (15 800 to 20 900) |

17 100 (14 800 to 19 700) |

15 800 (13 600 to 18 200) |

17 500 (15 100 to 20 100) |

17 400 (15 000 to 20 000) |

15 300 (13 200 to 17 600) |

15 600 (13 500 to 17 900) |

15 800 (13 700 to 18 100) |

| Physical education | 6300 (4900 to 7800) |

5700 (4400 to 7200) |

6000 (4600 to 7600) |

6300 (4900 to 7900) |

5900 (4600 to 7500) |

6400 (5000 to 8000) |

6000 (4600 to 7500) |

6100 (4800 to 7600) |

5900 (4600 to 7400) |

5700 (4400 to 7100) |

| Horse riding | 4300 (3100 to 5600) |

4000 (2900 to 5200) |

4700 (3500 to 6100) |

4400 (3200 to 5800) |

3600 (2600 to 4800) |

3900 (2800 to 5200) |

3900 (2800 to 5200) |

3800 (2800 to 5000) |

3400 (2500 to 4500) |

3400 (2400 to 4500) |

| Ice-skating | 9100 (7400 to 7411 000) |

4700 (3500 to 6000) |

1100 (500 to 1800) |

8500 (6800 to 6810 300) |

3200 (2200 to 4400) |

1400 (800 to 2100) |

1100 (500 to 1800) |

1000 (500 to 1600) |

1900 (1200 to 2800) |

3200 (2300 to 4300) |

| Road cycle racing | 1100 (600 to 1800) |

1100 (600 to 1800) |

2200 (1400 to 3200) |

2300 (1500 to 3300) |

2200 (1400 to 3200) |

3200 (2200 to 4400) |

2900 (2000 to 4000) |

2700 (1900 to 3800) |

2900 (2000 to 3900) |

3400 (2500 to 4500) |

| Inline/roller skating | 2200 (1400 to 3200) |

2500 (1600 to 3500) |

2300 (1500 to 3300) |

2000 (1200 to 2900) |

1800 (1100 to 2700) |

2100 (1300 to 3000) |

1700 (1000 to 2600) |

2000 (1200 to 2800) |

1500 (900 to 2200) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

| Motorcycle racing | 1900 (1200 to 2800) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

2000 (1200 to 2900) |

1800 (1100 to 2700) |

1800 (1100 to 2700) |

1400 (800 to 2200) |

1400 (800 to 2200) |

1200 (700 to 1900) |

1400 (900 to 2200) |

1700 (1100 to 2500) |

| Field hockey | 2000 (1200 to 2900) |

1400 (800 to 2100) |

1500 (900 to 2400) |

1400 (800 to 2200) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1600 (1000 to 2500) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1300 (700 to 2000) |

1600 (1000 to 2400) |

| Mountain bike racing | 1100 (600 to 1800) |

1000 (500 to 1700) |

1300 (700 to 2100) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1300 (700 to 2100) |

1700 (1000 to 2500) |

1700 (1000 to 2500) |

1700 (1000 to 2500) |

1700 (1000 to 2500) |

2200 (1400 to 3100) |

| Gymnastics | 1200 (700 to 2000) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1400 (800 to 2200) |

1600 (900 to 2400) |

1200 (700 to 2000) |

1300 (700 to 2000) |

1200 (700 to 2000) |

1300 (700 to 2000) |

1300 (800 to 2000) |

1200 (700 to 1900) |

Figure 2.

Time trends of severe sports-related emergency department visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by sports activity.

Injury diagnosis

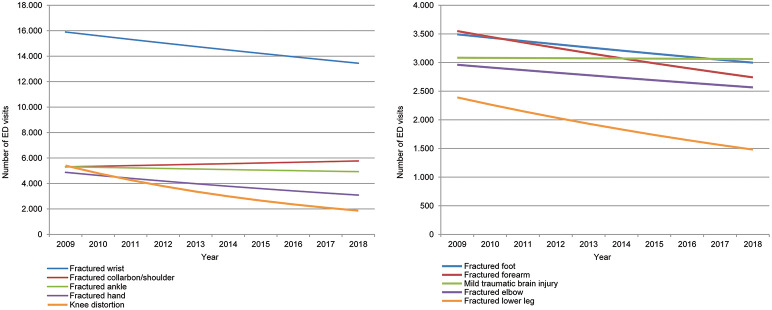

Table 3 presents the absolute number of severe sports-related ED visits, for the 10 injuries that, on average, were diagnosed in the EDs most often (between 2009 and 2018). This includes fractured wrist, fractured collarbone/shoulder, fractured ankle, fractured hand, knee distortion, fractured foot, fractured forearm, mild traumatic brain injury, fractured elbow and fractured lower leg. The time trends of these 10 injuries are presented in figure 3. The injury diagnoses of fractured wrist (−15%; 95% CI −24% to −5%), fractured hand (−37%; 95% CI −49% to −21%), knee distortion (−66%; 95% CI −74% to −55%) and fractured lower leg (−38%; 95% CI −55% to −14%) have significantly decreased between 2009 and 2018. The full data of the other 11 injuries are provided in online supplemental table S4.

Table 3.

Absolute number and 95% CI of severe sports-related emergency department visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by injury diagnosis (1–10)

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fractured wrist | 16 700 (14 400 to 19 200) |

15 300 (13 200 to 17 700) |

12 800 (10 700 to 15 100) |

16 100 (13 800 to 18 600) |

13 000 (11 000 to 15 300) |

13 900 (11 800 to 16 200) |

13 200 (11 100 to 15 400) |

13 700 (11 700 to 15 900) |

13 300 (11 300 to 15 400) |

14 800 (12 800 to 17 100) |

| Fractured collarbone/shoulder | 5100 (3900 to 6500) |

4800 (3600 to 6200) |

5100 (3800 to 6600) |

5600 (4300 to 7100) |

5300 (4000 to 6700) |

6100 (4700 to 7600) |

5600 (4300 to 7100) |

5500 (4300 to 7000) |

5200 (4000 to 6600) |

5800 (4600 to 7200) |

| Fractured ankle | 5300 (4100 to 6800) |

4500 (3400 to 5800) |

5200 (3900 to 6600) |

5400 (4100 to 6900) |

5000 (3700 to 6400) |

4900 (3700 to 6300) |

5200 (3900 to 6600) |

4800 (3600 to 6100) |

4800 (3700 to 6100) |

5000 (3800 to 6300) |

| Fractured hand | 4800 (3600 to 6100) |

4000 (3000 to 5300) |

4600 (3400 to 6000) |

4100 (3000 to 5500) |

4000 (2900 to 5300) |

3900 (2800 to 5100) |

3700 (2600 to 4900) |

2800 (1900 to 3800) |

3100 (2200 to 4100) |

3400 (2500 to 4500) |

| Knee distortion | 5200 (3900 to 6600) |

4800 (3600 to 6200) |

4300 (3100 to 5600) |

3800 (2700 to 5000) |

2800 (1900 to 3900) |

2800 (1900 to 3900) |

2600 (1700 to 3600) |

2300 (1500 to 3300) |

1900 (1200 to 2800) |

2200 (1500 to 3100) |

| Fractured foot | 3400 (2400 to 4500) |

3000 (2100 to 4100) |

3500 (2500 to 4700) |

3500 (2400 to 4700) |

3400 (2400 to 4500) |

3000 (2100 to 4100) |

3000 (2100 to 4200) |

2600 (1800 to 3600) |

3500 (2500 to 4600) |

2900 (2000 to 3900) |

| Fractured forearm | 3100 (2200 to 4300) |

3300 (2400 to 4500) |

3700 (2600 to 5000) |

3600 (2600 to 4800) |

2400 (1600 to 3400) |

3300 (2300 to 4400) |

2900 (2000 to 4000) |

2800 (1900 to 3800) |

2700 (1900 to 3700) |

2900 (2000 to 3900) |

| Mild traumatic brain injury | 3500 (2500 to 4600) |

2900 (2000 to 3900) |

2600 (1700 to 3700) |

3300 (2300 to 4500) |

2600 (1700 to 3600) |

2600 (1700 to 3600) |

3200 (2200 to 4300) |

3100 (2200 to 4200) |

2900 (2000 to 3900) |

3400 (2500 to 4500) |

| Fractured elbow | 3100 (2100 to 4200) |

2800 (1900 to 3800) |

2700 (1800 to 3700) |

2700 (1800 to 3800) |

2500 (1700 to 3600) |

2600 (1800 to 3700) |

2600 (1700 to 3700) |

2800 (1900 to 3800) |

2400 (1600 to 3400) |

2700 (1900 to 3700) |

| Fractured lower leg | 2300 (1500 to 3300) |

2100 (1300 to 3000) |

2100 (1300 to 3100) |

2000 (1300 to 3000) |

1900 (1100 to 2800) |

2000 (1200 to 2900) |

1700 (1000 to 2600) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

1500 (900 to 2300) |

Figure 3.

Time trends of severe sports-related emergency department visits in the Netherlands (2009–2018), by injury diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

The current study described time trends of severe sports-related ED visits in the Netherlands between 2009 and 2018. In this time period, the number of ED visits has decreased considerably (absolute reduction of 14%; 95% CI −19% to −9%).

Comparison with other studies

To date, a study describing the nationwide trends of severe sports-related ED visits has not been performed in the Netherlands. In contrast, previous studies have investigated time trends of sports-related ED visits in other countries. Namely, an Australian study reported an increase in sports injury-related ED visits between 2012 and 2015.21 Furthermore, an American study on sports-related ED visits among individuals aged 5–18 years reported an increase in sports-related injuries between 2009 and 2013,6 whereas we found a decrease among individuals aged 0–17 years between 2009 and 2018. This difference could be explained by the fact that in the current study only severe sports-related ED visits are included. Similar to the promising reduction in ED visits reported in our study, a Swedish study reported a decrease in sports injury-related ED visits between 2004 and 2007.22 However, an Australian study reported a significant annual increase in sport-related major trauma between 2001 and 2007.23 Differences between these studies could be explained due to differences in time periods, healthcare systems and healthcare policy.

Interpretation of results

The reduction in severe sports-related ED visits could be explained by new policies that have been adopted in the Netherlands aimed at improving the efficiency of emergency care. The number of individuals participating in sports on a weekly basis has slightly increased in the Netherlands over the years, but significant differences exist across sports activities.24 Therefore, this cannot be an explanation for the general reduction in severe sports-related ED visits. Interestingly, when the trends in severe sports-related ED visits are compared with all severe ED visits or with other specific ED visits in the Netherlands, differences become evident. Namely, the number of all severe ED visits and severe work-related ED visits has stayed the same between 2009 and 2018.18 In addition, the number of severe traffic-related ED visits has increased over time.

The current study shows a decreasing trend of ED visits over time in soccer, ice-skating and in inline/roller skating. The decreasing trend in soccer could be explained by mandating the use of shin guards, resulting in significant decreases in lower leg fractures.25 In addition, the decreasing trend in ice-skating could be explained by milder winters, resulting in fewer individuals ice-skating outside.

In contrast, ED visits for road cycle racing and mountain bike racing increased between 2009 and 2018. One possibility for the increased ED visits could be that exposure hours of road cycle racing or mountain bike racing have changed in the past decade. A national questionnaire on accidents and exercise among Dutch inhabitants—between 2009 and 2014—found that exposure hours slightly increased for road cycle racing but stayed the same for mountain bike racing.26 However, no information about exposure hours of these sports is available for 2015 through 2018.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of the current study is the use of the DISS data set. This data set is composed of a representative sample of nationwide sports-related ED visits. Furthermore, the current study extensively describes the number of severe sports-related ED visits on different age groups, gender, sports activities and injury diagnoses over a period of 10 years. A limitation is that this study does not provide a complete picture of nationwide sports injuries, as only severe sports-related ED visits were included in the analyses. Including low-risk activities (ie, minor injuries) in the analyses could give a better overview of sports injuries, aimed to look at preventative efforts. Another limitation of the study is that injury data are not corrected for exposure hours as this information is unavailable in the Netherlands. In the current study, a correction was made for changes in population composition between 2009 and 2018.

CONCLUSION

Between 2009 and 2018, the number of severe sports-related ED visits decreased considerably in the Netherlands across most age groups and sports activities. In contrast, the number of ED visits increased in road cycle racing and mountain bike racing. The results of the current study could act as a guide for the development of specific injury prevention policies, especially for road cycle racing and mountain bike racing. Future research should try to find out why these increasing trends are present. Determining the trends in exposure hours is essential, as well as evaluating injury prevention programmes specifically for road cycle racing and mountain bike racing.

What are the new findings?

The number of severe sports-related ED visits decreased considerably in the Netherlands across most age groups and sports activities between 2009 and 2018.

The number of ED visits increased in road cycle racing and mountain bike racing.

The majority of the severe sports-related injury diagnoses has significantly decreased over time.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Dutch hospitals for their collection of the data that are registered in the Dutch Injury Surveillance System.

Twitter: Evert Verhagen @evertverhagen.

Contributors: BO: concept, methodology, analysis, writing, editing paper. EK, HV: concept, methodology, editing paper. CS: methodology, analysis, editing paper. VG, EV: methodology, editing paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1. Warburton DER, Bredin SSD. Health benefits of physical activity: a systematic review of current systematic reviews. Curr Opin Cardiol 2017;32:541–56. 10.1097/HCO.0000000000000437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Field AE, Tepolt FA, Yang DS, et al. Injury risk associated with sports specialization and activity volume in youth. Orthop J Sport Med 2019;7:2325967119870124 10.1177/2325967119870124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Verhagen E. The cost of sports injuries. J Sci Med Sport 2010;13:e40 10.1016/j.jsams.2010.10.546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Forsdyke D, Smith A, Jones M, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with outcomes of sport injury rehabilitation in competitive athletes: a mixed methods studies systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:123–30. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-094850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Finch CF. Getting sports injury prevention on to public health agendas - addressing the shortfalls in current information sources. Br J Sport Med 2012;46:70–4. 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bayt DR, Bell TM. Trends in paediatric sports-related injuries presenting to US emergency departments, 2001–2013. Inj Prev 2016;22:361–4. 10.1136/injuryprev-2015-041757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Finch CF, Kemp JL, Clapperton AJ. The incidence and burden of hospital-treated sports-related injury in people aged 15+ years in Victoria, Australia, 2004–2010: A future epidemic of osteoarthritis? Osteoarthr Cartil 2015;23:1138–43. 10.1016/j.joca.2015.02.165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Toet H, Blatter B, Panneman M, et al. Dutch Injury Surveillance System: methods and applications (in Dutch). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VeiligheidNL, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pannier J. Bewegingsopvoeding in Een Gezondheidsperspectief - Sportmedische Advisering Voor Bewegingsopvoeding Op School (in Dutch). Amersfoort (the Netherlands), 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gaakeer MI, van den Brand CL, Gips E, et al. National developments in emergency departments in the Netherlands: numbers and origins of patients in the period from 2012 to 2015 (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2016;160:D970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gommer AM, Gijsen R. The validity of the estimates of the national number of visits to emergency departments on the basis of data from the injury surveillance system LIS (in Dutch). Bilthoven, The Netherlands: RIVM, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Meerding WJ, Polinder S, Lyons RA, et al. How adequate are emergency department home and leisure injury surveillance systems for cross-country comparisons in Europe. Int J Inj Control Saf Promot 2010;17:13–22. 10.1080/17457300903523237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Panneman M, Blatter B. Dutch injury surveillance system representative for all emergency departments in the Netherlands? (In Dutch). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VeiligheidNL, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Banning R, Camstra A, Knottnerus P. Statistics methods 201207 - sampling theory: sampling design and estimation methods. Heerlen, The Netherlands: Statistics Netherlands, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Association for the Advancement of Automotive Medicine Abbreviated injury scale: 2015 rision. 6th ed Chicago, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mannaerts GHH, Sawor JH, Menovsky T, et al. De betrouwbaarheid van de registratie van polytrauma-patiënten (in Dutch). Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1994;138:2290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization International classification of diseases. Published 2010. Available http://www.who.int/classifications/icd (accessed 24 Mar 2020).

- 18. Stam C, Blatter B. Letsel 2018: Kerncijfers LIS (in Dutch). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: VeiligheidNL, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Israëls A. Methods of standardisation (in Dutch). The Hague/Heerlen, The Netherlands: Statistics Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Statistics Netherlands Dutch population (in Dutch). Published 2019. Available http://www.cbs.nl/en-gb/society/population (accessed 24 Mar 2020)

- 21. Tharanga Fernando D, Berecki-Gisolf J, Finch C. Sports injuries in Victoria, 2012–13 to 2014–15: evidence from emergency department records. Med J Aust 2018;208:255–60. 10.5694/mja17.00872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Röding F, Lindkvist M, Bergström U, et al. Epidemiologic patterns of injuries treated at the emergency department of a Swedish medical center. Inj Epidemiol 2015;2:1–8. 10.1186/s40621-014-0033-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Andrew NE, Gabbe BJ, Wolfe R, et al. Trends in sport and active recreation injuries resulting in major trauma or death in adults in Victoria, Australia, 2001–2007. Injury 2012;43:1527–33. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Statistics Netherlands Sportdeelname wekelijks - Het aandeel van de Nederlandse bevolking van 4 jaar en ouder dat één keer per week of vaker sport (in Dutch). Available https://www.sportenbewegenincijfers.nl/kernindicatoren/sportdeelname-wekelijks (accessed 24 Mar 2020)

- 25. Vriend I, Valkenberg H, Schoots W, et al. Shinguards effective in preventing lower leg injuries in football: population-based trend analyses over 25 years. J Sci Med Sport 2015;18:518–22. 10.1016/j.jsams.2014.07.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. VeiligheidNL Accidents and exercise in the Netherlands (in Dutch). Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjsem-2020-000811s001.pdf (150.9KB, pdf)