Abstract

Pharmacists must be prepared to care for populations where health disparities are greatest and their services can best impact public health needs. Such preparation requires that students have access to practice experiences in underserved environments where pharmacy practice, cultural competence and knowledge of population health are experienced simultaneously. The correctional facility is such a place.

The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends that students receive preceptorship opportunities within the correctional system. The occasional collaboration or experiential opportunity, like Kingston's early model, has occurred between health professional schools and correctional facilities. However, to date, the correctional facility-experiential site remains an untapped opportunity, at least in a complete, coordinated, pharmaceutical care, patient management framework. Consequently, a short research study asked: To what extent is there potential for correctional facilities to serve as experiential practice sites for pharmacy students? The research objective was to identify pharmaceutical practices within South Dakota correctional system and compare those practices to the guidelines established by the Association of American College of Pharmacy's as optimal for student training. To understand medical and pharmaceutical practices in SDPS, three South Dakota Adult prison facilities were included in the exploratory study. Data was collected through a mixed methods approach designed to obtain perspectives about the SDPS health care system from individuals representing the numerous job levels and roles that exist within the health care continuum. Interviews and a web-based surveys were used to collect data. A review of a 36-page transcript along with 498 freeform survey comments revealed that while exact themes from the Exemplary Practice Framework may not have been evident, related words or synonyms for patient-centered care, informatics, public health, medication therapy management, and quality improvement appeared with great frequency.

Keywords: disparities, pharmacy practice, experiential education, population health

Background and Significance

Pharmacy practice has evolved from solely dispensing to direct patient care.1 Pharmacists must be prepared to care for populations where health disparities are greatest and their services can best impact public health needs.2 The correctional facility may, indeed, be such a place. The pharmacy profession plays a significant role within the care team for incarcerated populations.3 In this regard, the pharmacist is not only bound by their oath to relieve human suffering but must also provide quality care to this population.4,5

The relevance of public health and pharmacy practice to the correctional system population is significant provided that 1.5 million Americans are currently incarcerated under state or federal jurisdiction.6 In fact, one in every 31 adults, or 3.2 percent of the United States (US) population is under some form of correctional control.6 Despite the “inmate” branding that they wear, the prisoner is a person with real health care and pharmaceutical needs, oftentimes greater than the average citizen.7

There are a number of stereotypes that typify those incarcerated in the US correctional system. Some characterizations are, however, necessary to understand and address the health care needs of those within the system. For instance, prison inmates, particularly repeat offenders, are often from low socio-economic backgrounds where community conditions are substandard, educational attainment is low, and poor lifestyles and health behaviors are commonly practiced.8,9 Before they are incarcerated many prisoners have experienced inadequate nutrition and may practice a sedentary lifestyle.9 It is common for inmates to have a history of smoking, alcohol or substance abuse.8,9 Mental health concerns are also prevalent before incarceration.10 For these reasons, the health care of this population, including access to the medication therapy management services of pharmacists, is important to population health.

Present day prison health care policies fall short of following the principle of equivalence of care that has been established in the United States.11 This failure brings to question the extent to which established practice guidelines are followed and challenges the prison systems practice of human rights. Historically, prisons have struggled to provide adequate care for inmates due to overcrowding and staffing needs.12 Data from a 2014 Bureau of Justice report suggests that correctional facilities in eighteen states were filled past capacity, with some reporting as many as three times the number of inmates than their safe allowance.13 Such overcrowding is problematic to public health given the conditions that may manifest as a result.14 Increased threat of germ infestation and infectious disease risk, poor sanitation, air pollution, heightened emotions resulting in increased violence or feelings of depression and anxiety due to confinement.14 Overpopulation of inmates may also give rise to inadequate nutrition because of the need to stretch a limited food supply among an oversaturated population.14 These conditions are not perpetually contained within prison walls. Paroled inmates return to society taking with them the whole prison experience which in turn may pose threats to population health.15

Many prisons are not equipped to provide appropriate care.9,16 Current prisoners suffer significant rates of infectious and chronic diseases, among them--HIV, Hepatitis C, hypertension, asthma, arthritis, heart disease and diabetes.9,16 In fact, these conditions were found to be more prevalent in prisons than in the general population.9 It has been reported that approximately 40% of prisoners in federal, state, and local jails suffer a chronic disease.17 Inmates with existing chronic conditions or mental and behavioral health issues may experience delays in receiving necessary treatment until care is established within the system.18 Female and elderly inmates, particularly, are said to have more serious health concerns than their male counterparts.19,20 Elderly prison patients for example, represent 10% of the imprisoned population.19 This group suffers chronic care issues at significantly higher rates than their younger counterparts and are in need of treatment for all of their health issues no matter the severity.19

As part of their preparation for practice, pharmacy students should be exposed to the pharmacist's role as a recognized member of the interprofessional care team within the correctional setting.21,22 Within the correctional system, students will witness firsthand the complexities of medication therapy management in an environment where pharmacy practice, cultural competence, and knowledge of population health are experienced simultaneously.21 Pharmacy students may also gain a deeper understanding and empathy toward persons living within an environment where punishment, retribution, and rehabilitation are concurrent practices.

Two collaborative or experiential opportunities between health professional schools and correctional facilities have been described in published literature. In 1982, Kingston and colleagues characterized pharmaceutical care in the correctional institution as an academic opportunity for pharmacy students and implemented a course taught by core university faculty and members of the Minnesota prison health care team.23 The twenty contact-hour course explored health and medication needs for the inmate population and included ten hours of experience within the correctional site.23 In 2012, the University of Rhode Island introduced a similar correctional care-focused course.21 Sixth-year pharmacy students, while on rotation, were able to experience the correctional environment.21 The time spent within the system was not disclosed making direct comparisons between the two program experiences challenging.

These two examples aside, the correctional facility as an experiential site appears to be an untapped opportunity. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends that students receive preceptorship opportunities within the correctional system.24 The benefit of student presence in the correctional setting is multifold. Student pharmacists may serve in direct, patient-care roles, offer medication therapy counseling to inmates, or provide consultation to other care team members.

In 2015, two third-year pharmacy students along with a faculty member at South Dakota State University College of Pharmacy investigated the rights of incarcerated individuals to pharmacy services and the current role of pharmacists within the state's correctional system as part of a summer learning experience. The potential for a correctional facility to serve as an appropriate, experiential site for pharmacy students was also assessed by comparing current pharmacy practices in South Dakota's Prison System with the guidelines established by the American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy.

Research Methods

This investigative study used a multi-method approach to address the three identified interest areas. First, the rights of incarcerated individuals to health care and pharmacy services was investigated through the use of published materials, specifically social and clinical literature (PubMed, Ovid Medline, Academic Search Premier) using the search terms “prison health”, “prison medicine”, and “correctional health” and Lexus Nexus Academic to identify legal cases and constitutional references pertaining to prison inmate rights.

The current role of pharmacists within the South Dakota Prison System (SDPS) was assessed using two approaches-a document review of information provided by the Correctional Health Services at the South Dakota Department of Health, and a survey of prison medical staff with integral involvement with medication administration. The web-based survey, administered through Question Pro(tm), was designed to evaluate the translation of pharmacy practice policies into practice and included 12 questions pertaining to understanding of the pharmacist's role and prison staff relationships with the pharmacist. The survey included the opportunity for respondents to provide additional comments for each question. Comments were used in a content analysis to explore the alignment of information provided in these comments with the SDPS’ medical/pharmaceutical practice policies and exemplary practice site standards.

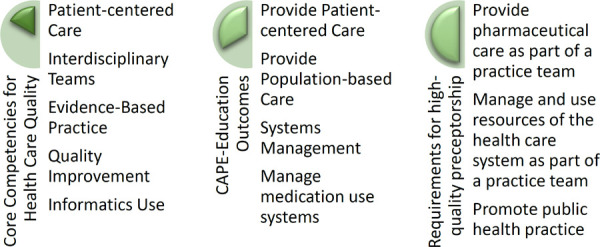

Finally, to determine the potential for SDPS to serve as an experiential education site for pharmacy students, a comparison of current pharmacy services obtained from document review of SDPS policies and procedures, personnel interviews, and the staff survey was made with the “Framework for Exemplary Practice” developed by the

American Association of Colleges of Pharmacy AcademicPractice Partnership Initiative (Figure 1).25 This framework is based on the five core competencies described in the 2002 Institute of Medicine report:26 1.) that a site must provide patient-centered care, 2.) involve interdisciplinary teams when possible, 3.) employ evidence-based practice, 4.) apply quality improvement principles and 5.) incorporation of informatics. Added to the five IOM competencies is a sixth, populationbased care/public health practice, which has been highlighted by the Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE). 27

Figure 1:

Framework for an Exemplary Practice Site

Results

Rights of Incarcerated Individuals to Pharmacy Services

On a global basis, The World Health Organization (WHO), has long-established guidelines for prison health care and has maintained that health care standards should not be lowered because of incarcerated status.28 The WHO cites the United Nations International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights and the United Nations Basic Principles for the Treatment of Prisoners to affirm the standards for health service delivery to prison inmates. Health care services in this regard should be available and delivered without discrimination.28 In the United States, the Constitution guarantees primary health care for incarcerated individuals in the United States.29 Although certain rights and freedoms have been revoked, prisoners should retain access to quality health and pharmaceutical care.29 These rights are established under the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments, defined as protections from cruel and unusual punishment and equal protection under the law, respectively. 29 However, history is replete with Constitutional violations against prisoners that were not remedied without court intervention. In the early part of the 20th century, courts believed that they were bound to follow Constitutional principles only in the sentencing of prisoners, and they were not to be involved with their treatment once they were transferred to prisons.30 But as the U.S. Supreme Court began to recognize important constitutional rights of the accused in the 1960’s (i.e. Miranda v. Arizona, for the Fifth Amendment right to remain silent upon arrest, and Gideon v. Wainright, for the Sixth Amendment right to counsel) it also began to recognize the rights of the incarcerated.31 Prisoner challenges to constitutional violations came in the form of “Section 1983” cases, which refer to claims emanating from Title 42 of the United States Code.31 This section allows an injured party to seek a legal remedy against a party acting under “color of law.”31 For example, a prison guard acting in his authority conferred to him by state law would be acting under color of law. If the guard's actions violate or deprive a prisoner of their constitutional rights, the state could be held liable under Section 1983.

Since the first successful Section 1983 case in 1964, the United States Supreme Court has interpreted the Eighth and Fourteenth Amendments to confer health care and pharmaceutical rights to prisoners in several respects. In Estelle v. Gamble, the Court held that prisons violate the Eighth Amendment prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment if they act with “deliberate indifference” to a prisoner's medical needs.32 Similarly, in Brown v. Plata, the Court found that all prisoners had the right to adequate medical and mental health care while incarcerated, and that population limits were necessary to remedy violations of prisoners’ Eighth Amendment rights.33 Subsequent court cases resulted in an expansion of the definition of “adequate care” in prisons, mandating that health services should be ethical and performed at the standard of modern medicine. 31

Today, care for prisoners in the US is governed by three principal bodies: The National Commission on Correctional Health Care (NCCHC), The American Public Health Association (APHA) and the American Medical Association (AMA).35,36 NCCHC accreditation is the stamp of approval for patient safety within the prison system. 35The accreditation body lists twelve compliance indicators on which it bases its standard of practice to ensure that pharmaceutical operations are sufficient to meet the needs of the facility and conform to legal requirements.35 Among the measures is an assurance that facilities comply with federal regulations for dispensing and disposing of medications and that medications are stored in a highly secure area.35 US prison facilities are accredited through the NCCHC, which includes representatives from the American Pharmacists Association (APhA). NCCHC also provides guidance on published prescription standards.35,36

Pharmaceutical Care Services in the South Dakota Prison System

To understand medical and pharmaceutical practices in SDPS, three South Dakota Adult prison facilities (the South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls, South Dakota Women's Prison in Pierre, and Mike Durfee State Prison in Springfield) were included in an exploratory study. Together these facilities housed 3,271 inmates and employed 85 health care staff serving in various capacities at the time of the study.

A document review was facilitated by a key department of health administrator responsible for prison pharmaceutical services. The document provided, Pharmaceutical Operations: Correctional Health Services South Dakota Department of Health (revised 2014),37 provided policies and stated roles of various health care professionals involved in medication operations. Reviewing role-specific responsibilities, we identified which departments and roles were involved directly with policymaking and the actual administration of medication. Interviews with individuals responsible for pharmaceutical policymaking, practice, and evaluation in the SDPS provided further insights into operational aspects of pharmacy practice.

A formal Correctional Health Services Program is responsible for the delivery of quality and cost-efficient services to the nearly 4000 inmates within the South Dakota Prison System (SDPS). Services include primary care, acute inpatient care, dental and optometric care. All sites are accredited by the NCCHC, which includes representatives from the American Pharmacists Association (APhA). Re-accreditation occurs every 3 years for South Dakota's Correctional Health Services. 37 As a result, there are related duties and responsibilities carried out by internal and external personnel. The consultant pharmacist, who is not a member of full time prison staff, is commissioned with the dispensing responsibility for prison medication. The pharmacist must visit the prison site quarterly to perform drug audits and destroy controlled and expired medications. Staff pharmacists fill medications off-site and ensure proper handling of controlled medications within the prison. 37

A formulary or exclusive list of medications used for inmate therapies is determined, approved and managed by the Correctional Health Management/Pharmacy Therapeutics (P&T) committee. A Formulary Review Committee, which includes the consultant pharmacist, medical director, and others including nursing professionals, addresses concerns about additions or deletions to the formulary. Drug therapies from the established formulary, whether emergent or for longterm use, are prescribed by a physician, nurse practitioner or physician assistant who are considered “advanced practice” personnel. Single doses are provided by a registered nurse who obtains them as prepackaged blister packs or from a remote, automated dispensing system (Talyst's InSite for Corrections, Kirkland, WA, USA) located in the site's medication storage area.38

Pharmacists are not involved in direct patient care services such as patient assessment, counseling or surveillance, as has been long- recommended as vital service needs by Knapp in 2002.39 A designated “advanced practice” professional, likely a physician, is responsible for issuing prescriptions, patient counseling, monitoring patient outcomes and making decisions regarding overall patient care. The pharmacist is responsible for general oversight and quality control of prescription fulfillment i.e., the traditional role of dispensing and medication auditing. Pharmacists are not used to their full knowledge capacity and serve only in a consultant and problem-solving role focused on the medication, not the patient.

The policy description of pharmaceutical processes within SDPS dictates the standard duties for the pharmacy consultant or facility-serving pharmacist, which in South Dakota's case, is one in the same. These duties include: assuring that medication is legally provided in a timely and accurate manner, quarterly audits of the emergency drug box, no less than quarterly site visits to complete pharmacy audits, destruction of expired, controlled medications, administrative consent of controlled substances and, of course, fulfillment of prescriptions.37

A Yankton, South Dakota pharmacy is the sole pharmacy contracted to fill prescriptions for South Dakota state prison facilities. According to a prison official, local pharmacies may be used in the event of an emergency when the main pharmacy is closed and the inmate has an acute medication need or there has been an automated machine dysfunction. Medication within each correctional facility is stored under appropriate conditions of sanitation, temperature, lighting, ventilation and security. Nurses may administer drugs to the prisoner directly or provide them to a patient care technician or medical aide to administer. Legend drugs, antidotes, and emergency medication are inventoried weekly by internal personnel.

Medications may also be under the control of the inmate. A pharmacist working with the prison estimates that approximately 90% of medications are carried and selfadministered by the inmates.3 In-possession prescriptions along with non-prescription medications for less severe ailments are common for acute and chronic conditions. While this tendency empowers the prisoner-patient to take an active role in his or her care40, this is a trend, according to one prison official, that the South Dakota Department of Corrections would like to abolish given the common practice of inmates using their medications as currency. If medications are not kept on their person, then there are fewer opportunities for inmates to misuse medications.

Staff Perceptions of Pharmacist Roles

Survey responses were received from 44 of the 85 individuals meeting the role inclusion criteria of prison medical staff with integral involvement with medication administration. One respondent did not provide responses to any of the questions after entering the survey and was not included in analysis leaving a usable response rate of 50.6%. Among the 43 respondents, staff identifying as registered nurses comprised the majority (86%) and licensed practical nurses comprised 7.0%. Two technician/medication aides and one clinical supervisor also responded. No responses were received from physicians, nurse practitioners or physician assistants.

Overall, prison medical staff agree or strongly agree that interactions with pharmacists are positive (Table 1). The majority of prison staff have consulted with pharmacy staff on a regular basis (62.8%), have a good working relationship with pharmacists providing services to the SDPS (62.8%), indicate that the pharmacy staff is instrumental in providing the best possible care to inmates (72.1%), that pharmacy personnel are available and willing to help when problems arise (58.2%) and that pharmacy personnel listen to concerns regarding medication problems (79.3%), although somewhat qualified as exemplified by one comment: “they will listen to my issues [but] they offer little to no support and almost never any solutions or possible work arounds.” Prison staff also largely indicated support for more pharmacist involvement in the care provided to SDSP inmates (Table 1) and 48.8% either agreed or strongly agreed that they would like a full-time pharmacist onsite. Efforts to expand communications between nurses, doctors and pharmacists as a care improvement process was supported by an overwhelming majority (83.7%).

Table 1: Survey Responses.

Number Respondents (Percent of Respondents)

| Strongly Agree | Agree | Neutral | Disagree | Strongly Disagree | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I would like to have a full-time pharmacist on-site to help resolve problems and answer questions. | 13 (30.2%) | 8 (18.6%) | 12 (27.9%) | 9 (20.9%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| I am aware of the prison's Pharmaceutical Operations policy document | 7 (16.3%) | 18 (41.9%) | 7 (16.3%) | 8 (18.6%) | 3 (7.0%) |

| Communication regarding healthcare of inmates between nurses, doctors, and pharmacists is optimal. | 1 (2.3%) | 16 (37.2%) | 11 (25.6%) | 10 (23.3%) | 5 (11.6%) |

| I consult with the pharmacy staff on a regular basis | 5 (11.6%) | 22 (51.2%) | 11 (25.6%) | 5 (11.6%) | 0 – |

| I have a good working relationship with the pharmacists contracted with the South Dakota Department of Corrections | 7 (16.3°%) | 20 (46.5%) | 11 (25.6%) | 3 (7.0%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| I feel a disconnect or a distance from the pharmacy staff contracted with the South Dakota Department of Corrections. | 5 (11.6%) | 8 (18.6%) | 13 (30.2%) | 14 (32.6%) | 3 (7.0%) |

| Efforts to expand communication between nurses, doctors, and pharmacists would improve care provided to inmates. | 12 (27.9%) | 24 (55.8%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0 – | 0 – |

| Pharmacists have a good understanding of relevant operations inside the prison. | 1 (2.3%) | 10 (23.3%) | 14 | 13 (30.2%) | 5 (11.6%) |

| The pharmacy staff is instrumental in providing the best possible care to inmates. | 5 (11.6%) | 26 (60.5%) | 7 (16.3%) | 4 (9.3%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| Pharmacy personnel are available and willing to help me when problems arise. | 6 (14.0%) | 19 (44.2%) | 12 (27.9%) | 5 (11.6%) | 1 (2.3%) |

| The pharmacy is willing to listen to my concerns regarding medication related problems. | 7 (16.3%) | 27 (62.8%) | 9 (20.9%) | 0 – | 0 – |

A majority of prison staff (55.8%) also indicated that they would like the pharmacist to play a larger role in the prison. Of the 32 comments received, only two identified patientoriented roles--both indicating patient education. Another three comments referred to addressing prison staff concerns and questions about specific medications related to adverse events and contraindications. The remaining comments received generally identified expanded roles in traditional dispensing functions, however. A number of medication distribution problems were identified, particularly concerns related to the automated dispensing system, timely delivery of medication orders, the correction of medication dispensing errors, which could be addressed if pharmacists had a greater role in the medication distribution system.

Comparison of Pharmacist Roles in SPDS and Exemplary Training Site Characteristics

Based on document review of SDPS policies and procedures, personnel interviews, and the staff survey, the current roles that pharmacists fulfill in the delivery of pharmacy services to SDPS are limited to basic roles for medication administration and policy within the prison (Table 2). The pharmacist serves in a consultant capacity for medication dispensing concerns, is not stationed within the prison facility on a daily basis, and is not used in the direct-care service role. The pharmacist offers recommendations to the P&T committee, and prescription fulfillment and audit services to each site. All other medication related responsibilities are assumed by both medical and nonmedical personnel at the prison facilities including nursing, medical technologists and prison guards. The inmate may also hold the responsibility of managing their own medication, earning the privilege of having medications in his or her care, but the pharmacist does not serve in a patient-education capacity for these inmates.

Table 2: Comparison of correctional system and exemplary experiential site characteristics.

| Focus Area | Current Pharmacist Role in Corrections |

|---|---|

| Patient-Centered Care |

|

| Interdisciplinary Care Teams |

|

| Evidenced-based Practice/Systems Management |

|

| Quality Improvement |

|

| Informatics Use/Managed Medication Use System |

|

| Population-based care/Public Health Practice |

|

Discussion

The correctional system is not presently used as an experiential practice site for pharmacy students in South Dakota. As an appropriate experiential practice site for pharmacy students, the pharmacist's role must be reconsidered to be more in line with a medication therapy management model. From our review we uncovered the basic roles for medication administration and policy within the prison.

There is an opportunity to identify areas within the prescribing and administration process where a pharmacist may expand their role within the SDPS correctional system. Analysis of the staff survey of administrators, nurses, medical technicians, nurses’ aides, prison guards and a consultant pharmacist illustrated variability in knowledge and opinions about medication therapy management within their correctional system. Policies and standards of practice are evident but not fully understood by all, particularly if such policy or practice is not relevant to their immediate job responsibilities. Given the survey findings, it appears that the pharmacist is not used for their full knowledge capacity and serves only in a consultant and in a problem-solving role focused on the medication delivery system and not the patient.

Expansion of pharmacist roles would create the opportunity for pharmacy students to take part in an important experiential rotation. Correctional facilities are generally not given attention within the pharmacy curriculum but should be included given the significant population and the degree to which pharmacy services are required within their walls.

MTM programs have long been supported as compelling efforts to improve the quality of care, especially of chronic conditions.41 Pharmacist training in medication therapy management is particularly important when considering the obstacles surrounding the provision of pharmacy services to this culturally diverse population. Challenges include gaining access to needed medications, cultural and language barriers, poor health literacy and communication dissonance among providers and their patients. Instituting an experiential practice model that is in line with exemplary practices is likely to not only improve student pharmacy education but also improve overall patient care among prison inmates. The inherent complexities of correctional medicine warrant a greater involvement of an amalgam of professionals consulting each other on difficult cases, carrying out appropriate practice guidelines, and evaluating treatment interventions and outcomes among inmate-patients. With an enhanced role, where the pharmacist is a direct care provider, the health care team would become a powerful instrument in obtaining positive health care outcomes.

Conclusion

Prison facilities present an opportunity to develop an exemplary experiential education site for pharmacy students. Evidence-based pharmacy practices should be systematically adapted for the prison health care setting, for optimal care management and for the support of inmate health.

References

- 1.Brazeau GA, Meyer SM, Belsey M, Bednarczyk EM, Bilic S, Bullock J, DeLander GE, Fiese EF, Giroux SL, McNatty, Nemire D, Prescott WA, Traynor AP. AACP curricular change summit supplement: Preparing pharmacy graduates for traditional and emerging career opportunities. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2009;73(8):157–169. doi: 10.5688/aj7308157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Svarstad BL, Kotchen JM, Shireman TI, Crawford SY, Palmer PA, Vivian EM, Brown RL. The team education and adherence monitoring (TEAM) trial. Pharmacy interventions to improve hypertension control in blacks. Circulation and Cardiovascular Quality Outcomes. 2009. pp. 264–271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.MacDonnell C, George P, Nimmagadda J, Brown S, Gremel K. A team-based curriculum bringing together students across educational institutions and health professions. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2016;80(3):49–56. doi: 10.5688/ajpe80349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Pharmacy Association Oath of a Pharmacist www.pharmacist.comAccessedApril82018

- 5.American Society of Health-System Pharmacists ASHP guidelines: minimum standard for pharmacies in hospitals. Am Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 2013;70:1619–30. doi: 10.2146/sp130001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carson EA, Anderson E. Prisoners in 2016. US Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs: Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2018. p. NCJ251149.

- 7.Perry J. Management of long-term conditions in a prison setting. Nursing standard (Royal College of Nursing (Great Britain): 1987). 2010;24(42):35–40. doi: 10.7748/ns2010.06.24.42.35.c7849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Binswanger IA, Carson EA, Krueger PM, Mueller SR, Steiner JF, Sabol WJ. Prison tobacco control policies and deaths from smoking in United States prisons: population based retrospective analysis. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2014;349:g4542. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g4542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binswanger IA, Krueger PM, Steiner JF. Prevalence of chronic medical conditions among jail and prison inmates in the USA compared with the general population. Journal of epidemiology and community health. 2009;63(11):912–919. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.090662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Segal AG, Frasso R, Sisti DA. County Jail or Psychiatric Hospital? Ethical Challenges in Correctional Mental Health Care. Qualitative health research. 2018. pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Jotterand F, Wangmo T. The principle of equivalence reconsidered: Assessing the relevance of the principle of equivalence in prison medicine. The American Journal of Bioethics. 2014;14(7):4–12. doi: 10.1080/15265161.2014.919365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Guerrero J, Marco A. Overcrowding in prison and its impact on health. Revista Española de Sanidad Penitenciaria: RESP. 2012;14:106–113. doi: 10.4321/S1575-06202012000300006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carson EA, Anderson E. Prisoners in 2015. US Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs: Bureau of Justice Statistics. 2016. p. NCJ250229.

- 14.Cloud D. On Life Support: Public Health in the Age of Mass Incarceration. Vera Institute of Justice. 2014.

- 15.Restum ZG. Public Health Implications of Substandard Correctional Health Care. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(10):1689–1691. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chari KA, Simon AE, DeFrances CJ, Maruschak L. National Survey of Prison Health Care: Selected findings. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2016. (National health statistics reports; no 96). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maruschak LM, Berzofsky M, Unangst J. Medical problems of state and federal prisoners and jail inmates, 2011-2012. US Department of Justice. Office of Justice Programs: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. p. NCJ248491. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brinkley-Rubinstein L. Incarceration as a catalyst for worsening health. Health & Justice. 2013;1(3):1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nowotny KM, Cepeda A, James-Hawkins L, Boardman JD. Growing Old Behind Bars:Health Profiles of the Older Male Inmate Population in the United States. Journal of Aging and Health. 2016;28(6):935–956. doi: 10.1177/0898264315614007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nowotny KM, Rogers RG, Boardman JD. Racial disparities in health conditions among prisoners compared with the general population. SSM - Population Health. 2017;3:487–496. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marcoux RM, Simeone JC, Colavita M, Larrat EP. An Innovative Approach to Pharmacy Management in a State Correctional System. Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2012;18(1):53–61. doi: 10.1177/1078345811421732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Erickson A. Advancing pharmacy practice behind bars. Pharmacy Today. 2012;18(9):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kingston RL, Pfeifle CE, Cipolle RJ, Zaske DE, Eells CB, Johnson HL. Comprehensive pharmaceutical services for a state correctional facility. American journal of hospital pharmacy. 1982;39(1):86–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Society of Health System Pharmacists ASHP guidelines on pharmacy services in correctional facilities. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2016;73:1784–90. doi: 10.2146/ajhp160143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Association of American Colleges of Pharmacy Academic-Practice Partnership Initiative Profiling Project. 2006. Pilot project to profile exemplary advanced practice experience sites. Association of American Colleges of Pharmacy.

- 26.Medina MS, Plaza CM, Stowe CD, Robinson ET, et al. Center for the Advancement of Pharmacy Education (CAPE) Educational Outcomes 2013. American Journal of Pharmacy Education. 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit . In: Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); The Core Competencies Needed for Health Care Professionals; 2003. Chapter 3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moller L, Stover H, Jurgens R, Gatherer A, Nikogosian H. World Health Organization. Copenhagen, Denmark: 2007. Health in prisons: A WHO guide to the essentials of prison health. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klein S. Prisoners’ rights to physical and mental health care: A modern day expansion of the Eight Amendment's cruel and unusual punishment clause. Fordham Urban Law Journal. 1979;7(1):1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stroud v, Swope F., 2d 9th Circuit. 1951. p. 850.

- 31.Yanofski J. Prisoners v. Prisons. Psychiatry. 2010;7(10):41–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Court US. Estelle v. Gamble . APPEALS CTTUSCO. US Supreme Court; pp. 75–929.pp. 1976 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Newman WJ, Scott CL. Brown v. Plata: Prison overcrowding in California. Journal of the Academy of Psychiatry Law. 2012;40:547–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.United States v DeCologero. p. 821.p. 39.p. 43. F.2d.

- 35.National Commission on Correctional Health Care . Standards for health services in prison. NCCHC; Chicago, Ill: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 36.American Public Health Association Correctional Health Care Standards and Accreditation. Policy #:20048. 2004.

- 37.Malsam-Rysdom K. [Jan 2;2018 ];Correctional Health. 2018 doh.sd.gov/corrections Accessed.

- 38.Talyst L.Medication Automation for Corrections 2018http://www.talyst.com/solutions/long-term-care/corrections/AccessedJanuary22018

- 39.Knapp DA. Professionally determined need for pharmacy services in 2020. American Journal of Pharmacy Education. 2002;66(4):421–429. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Offender Health Research Network An evaluation on in-possession medication within the prison system: A report of the National Institute of Health Research. Aug, 2009.

- 41.Shah P, Goad J, Mirzaian E, Durham M. The Emerging Role of the Pharmacist in Medication Therapy Management and Challenges Facing Expansion. California Pharmacist. 2012;59(2):22–25. [Google Scholar]