Abstract

Background:

Purpura fulminans (PF) is a potentially fatal uncommon disorder of intravascular thrombosis and is clinically characterized by rapidly progressive hemorrhagic infarction of the skin.

Objective:

To describe the clinical feature and outcome of a series of patients with PF.

Materials and Methods:

A descriptive study based on review of case records was carried out at a tertiary care hospital in Kolkata.

Results:

Twenty three consecutive cases seen over a period of 8 years were studied. The age range was 4 days to 78 years (mean 35.6 years) with a male to female ratio of 1:2.8. Hemorrhagic rash was the universal presenting symptom. Other major presenting features included pneumonia (26.1%), sudden-onset shock syndrome (21.7%), and urinary tract infection (17.4%). All patients presented with retiform purpura and lesional necrosis and 8 (34.8%) patients had associated peripheral gangrene. Nineteen (82.6%) patients had sepsis and 60.9% patients had vesiculo-bullous lesion. Pneumococcus was the most common (26.1%) pathogenic organism detected. The precise cause of PF could not be detected in two (8.7%) patients. One patient (4.3%) with neonatal PF had protein C deficiency. All patients had evidence of disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). One patient had to undergo a below knee surgical amputation and one patient had autoamputation of the digits. Ten (43.5%) patients succumbed to their illness. Seven of the 8 patients who had peripheral gangrene had a fatal outcome.

Limitations:

Relatively small sample size and a referral bias were a few limitations of the present study.

Conclusion:

The present study emphasizes that PF is a cutaneous marker of DIC. Association of peripheral gangrene, leukopenia and neutropenia may be the reason for the high mortality rate.

KEY WORDS: Disseminated intravascular coagulation, peripheral gangrene, purpura fulminans

Introduction

Purpura fulminans (PF) is a rare disorder of intravascular thrombosis and is clinically characterized by rapidly progressive hemorrhagic infarction of the skin with high mortality rate.[1,2,3,4,5,6,7] Dermatologists are often consulted to help out with the diagnosis and management of purpura fulminans.[5,8] Recognition of the clinical presentation and the outcome of this condition are important, because the disease may mimic the features of several other disorders, such as simple purpura, necrotizing fasciitis, vasculitis, or diseases that cause gangrene. In spite of the gravity of the problem, there is a paucity of formal studies on purpura fulminans. Furthermore, the condition is not well-studied in non-Western population, which prompted us to undertake the present study.

Materials and Methods

This was a descriptive study based on the review of case records of patients seen over a period of eight years (February 2009 to January 2017). All the patients received institutionalized management and all the patients were referred from the clinic of the departments of internal medicine, pediatrics, gynecology and obstetrics, or intensive care unit. Detailed analysis of history, physical findings, laboratory work-ups, and clinical outcome of patients with a diagnosis of purpura fulminans was undertaken. Laboratory investigations including blood sugar, liver function test, urea, creatinine, urinalysis, urine culture, blood culture, protein C and S estimation, d-dimer, procalcitonin, fibrin degradation product, antinuclear antibody (Hep 2 cell line), screening for antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and skin biopsy were done as and when needed. Chest X-ray and ultrasonography of abdomen were also done. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC).

Case definitions

Purpura fulminans was defined as the rapid-onset, progressive form of retiform purpuric lesions associated with hemorrhagic infarction.[1] Peripheral gangrene was defined as the clinical features of gangrene of acral areas.[7] Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) was defined as moderate to severe thrombocytopenia (<100000/dl) along with laboratory features indicating increased thrombin generation (e.g., decreased fibrinogen) and increased fibrinolysis (e.g., elevated fibrin-degradation products and D-dimer).[5,8,9] Shock was defined as the sudden onset of hypotension and hypovolemia with end-organ failure requiring intensive management.[5]

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 5 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA; 2007) software and Microsoft Excel.

Results

Demographic data

The records of 23 consecutive patients [Table 1] (age range: 4 days to 78 years; mean: 35.6 years; SD: 23.9) were extracted. Of them, 6 were male and 17 were female with a male to female ratio of 1:2.8.

Table 1.

Profile of patients with purpura fulminans

| Age | Gender | Presentation | DIC | Retiform purpura | Vesicle/bullae | Site | Skin necrosis | Peripheral gangrene | Cause | Outcome | Time span to death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 66 years | Female | Sudden-onset shock syndrome | Present | Present | No | Arm | Present | Absent | Klebsiella | Survived | - |

| 45 years | Female | Postoperative fever | Present | Present | Yes | Abdomen | Present | Present | E. coli | Death | 6 days |

| 29 years | Female | Puerperal sepsis following cesarean section | Present | Present | No | Abdomen | Present | Absent | E. coli | Survived | - |

| 18 years | Female | Pneumonia | Present | Present | Yes | Arm | Present | Absent | Pneumococcus | Survived | - |

| 16 years | Female | Pneumonia | Present | Present | Yes | Forearm | Present | Present | Pneumococcus | Death | 5 days |

| 51 years | Female | Urinary tract infection | Present | Present | Yes | Thigh, leg | Present | Absent | E. coli | Survived | - |

| 62 years | Male | Pneumonia | Present | Present | No | Thigh, leg | Present | Absent | Pneumococcus | Survived | - |

| 49 years | Female | Urinary tract infection | Present | Present | No | Leg, feet | Present | Present | Pseudomonas | Death | 4 days |

| 78 years | Female | Cellulitis | Present | Present | Yes | Leg, feet | Present | Present | Streptococcus pyogenes | Death | 5 days |

| 53 years | Male | Cellulitis | Present | Present | No | Thigh, leg, feet | Present | Present | Streptococcus pyogenes | Survived | - |

| 1 year | Female | Sudden-onset shock syndrome | Present | Present | Yes | Thigh, leg, feet, arm, face, forearm | Present | Absent | Group B Streptococcus | Death | 6 days |

| 42 years | Male | Pneumonia | Present | Present | Yes | Chest | Present | Absent | Pneumococcus | Survived | - |

| 43 years | Male | Cellulitis | Present | Present | Yes | Thigh | Present | Absent | Idiopathic | Survived | - |

| 22 years | Female | Urinary tract infection | Present | Present | Yes | Arm | Present | Absent | Proteus | Survived | - |

| 19 years | Female | Cellulitis | Present | Present | Yes | Forearm | Present | Absent | Staphylococcus aureus | Survived | - |

| 50 years | Female | Sudden-onset shock syndrome | Present | Present | Yes | Leg, feet | Present | Present | Idiopathic | Death | 8 days |

| 6 years | Female | Sudden-onset shock syndrome | Present | Present | Yes | Thigh, leg | Present | Absent | Pneumococcus | Survived | - |

| 68 years | Male | Pneumonia | Present | Present | Yes | Leg, feet | Present | Present | Klebsiella | Death | 7 days |

| 7 years | Female | Convulsions | Present | Present | No | Lower limbs, abdomen, upper limbs | Present | Absent | Meningococcus | Survived | - |

| 3 years | Female | Pneumonia | Present | Present | No | Arm, forearm | Present | Absent | Staphylococcus | Death | 4 days |

| 4 days | Male | Sudden-onset shock syndrome | Present | Present | No | Back | Present | Absent | Protein C deficiency | Death | 3 days |

| 31 years | Female | Urinary tract infection | Present | Present | No | Hand, elbow, leg | Present | Absent | E. coli | Survived | - |

| 59 years | Female | Congestive cardiac failure | Present | Present | Yes | Hand, feet, trunk | Present | Present | Pneumococcus | Death | 5 days |

Clinical presentation

All the patients [Figures 1-5] presented with a hemorrhagic skin rash. Besides that, other presenting conditions were pneumonia (n = 6, 26.1%), sudden-onset shock syndrome (n = 5, 21.7%), urinary tract infection (n = 4, 17.4%), cellulitis (n = 4, 17.4%), dilated cardiomyopathy with low cardiac output and congestive cardiac failure (n = 1, 4.3%), postoperative fever (n = 1, 4.3%), puerperal sepsis following cesarean section (n = 1, 4.3%), and convulsion (n = 1, 4.3%).

Figure 1.

Retiform purpura with focal necrosis, ulceration, and bulla formation over the forearm

Figure 5.

Typical lesions of purpura fulminans with acral gangrenous changes in a postoperative patient

Figure 2.

Purpura fulminans of the lower limbs

Figure 3.

Lesions of purpura fulminans on the back of neonate with congenital protein C deficiency

Figure 4.

Purpura fulminans with impending symmetrical peripheral gangrene

Cutaneous features

Retiform purpura and lesional necrosis were present in all (100%) patients. Eight (34.8%) patients had associated peripheral gangrene. Hemorrhagic vesiculo-bullous lesions were present in 14 (60.9%) patients. Lower limbs were most commonly (n = 13; 56.5%) affected site, followed by upper limbs (n = 10; 43.5%), abdomen (n = 3; 13%), trunk (n = 3; 13%), and face (n = 1, 4.3%).

Etiology

Twenty (87%) patients had sepsis. Pneumococcus was the most common pathogenic organism detected, seen in 6 (26.1%) patients followed by Escherichia coli (n = 4, 17.4%), Klebsiella (n = 2, 8.7%), Streptococcus pyogenes (n = 2, 8.7%), Staphylococcus aureus (n = 2, 8.7%), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 1, 4.3%), Group B streptococcus (n = 1, 4.3%), Meningococcus (n = 1, 4.3%), and Proteus (n = 1, 4.3%). The precise cause of purpura fulminans could not be detected in two (8.7%) patients. One patient (4.3%) with neonatal purpura fulminans had protein C deficiency. One (4.3%) patient with pneumococcal sepsis additionally had dilated cardiomyopathy with low cardiac output and congestive cardiac failure. In addition, one patient had rheumatoid arthritis. Based on the laboratory and clinical parameters, all (100%) patients of the present series had DIC.

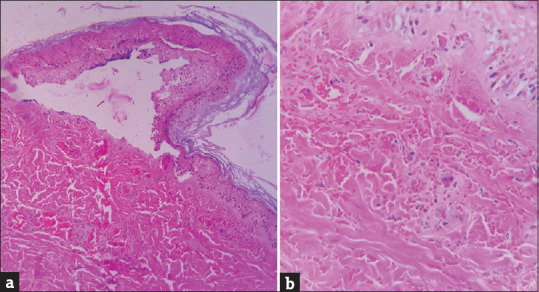

Skin biopsy was performed in 11 patients. The histopathological examination of the lesional punch biopsy specimens showed more or less uniform features of necrotic keratinocytes, subepidermal bullae, and thrombotic changes of the small blood vessels and extravasation of red blood cells in the dermis [Figure 6].

Figure 6.

(a) Epidermis shows necrosis with formation of subepidermal bulla (H and E, ×100). (b) Edematous dermis with extravasation of red blood cells. Fibrin thrombi and inflammatory cells are present in the lumen of the capillaries in the dermis (H and E, ×400)

Outcome

Of the 23 patients, one (4.3%) patient had to undergo below knee surgical amputation and another suffered autoamputation of the digits. Ten (43.5%) patients died of their illness. Of these 10 patients, nine (90%) died within the first week of onset of purpura fulminans.

Factors associated with mortality

Seven (87.5%) out of the eight patients who had peripheral gangrene died. Four (40%) out of the 10 patients who died, had leucopenia with neutropenia.

Discussion

Purpura fulminans (PF) is a disabling and life-threatening disorder characterized by acute onset progressive cutaneous hemorrhage and necrosis.[2] The syndrome of purpura fulminans was first described by Guelliot in 1884; the name was first adopted by Henoch in 1887.[10] The diagnosis of purpura fulminans is essentially clinical and requires a high index of suspicion.[11] The differential diagnosis includes warfarin-induced skin necrosis, cryoglobulinemic vasculitis, catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, and Henoch–Schönlein purpura (IgA vasculitis).[2,11] Patients with PF have laboratory parameters consistent with DIC, including prolonged coagulation time, decreased fibrinogen, elevated D-dimers, and thrombocytopenia. These patients often had elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) in the setting of an inappropriately low erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).[11] The PF lesions have a distinctive appearance, which may help differentiate them from other purpuric lesions.

A patchy erythema is rapidly followed by irregular central areas of blue-black hemorrhagic necrosis with a surrounding erythematous margin. Vesicles and bullae may follow. The involved areas are usually painful and indurated.[2,7,11]

Although initially sterile, secondary infection of gangrenous tissue may supervene, contributing to late mortality and morbidity. Necrosis may extend up to the level of muscle and bone. Healing leads to scarring and auto-amputation of digits and extremities often follows.

The skin lesion is mainly caused by thrombosis of dermal microvasculature which eventually results in perivascular hemorrhage and necrosis with minimal inflammation.[10] Although these lesions are frequently thought to be due to hemorrhage, skin biopsies clearly reveal that the pathophysiology of the lesions are actually dermal vessel thrombosis.[7,10] The microvasculature of other body organs may also be affected resulting in necrosis and dysfunction. Table 2 summarizes the salient features of patients described in previous case series of PF.

Table 2.

Comparing salient features of purpura fulminans amongst different case series

| Study (Year) | Age | Gender | Etiology | Clinical presentation | DIC | Peripheral gangrene | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis et al. (2007)[5] n=12 | 2 years to 91 years | Male > Female | Infectious (75%), Surgical (16.6%), Cancer (8.3%). | Sudden-onset shock syndrome (25%), pneumonia (25%), urinary tract infection (8.3%), pharyngitis (8.3%), shock following dog bite (8.3%), small cell lung cancer (8.3%), postoperative sepsis (8.3%), abdominal compartment syndrome (8.3%). | 91.7% | 100% | 3 patients (25%) succumbed to death. Of the 9 surviving patients, 8 required amputation of at least one limb. |

| Talwar et al. (2012)[13] n=3 | 3 days to 30 years | Male > Female | Infectious (33.3%) Idiopathic (33.3%) Protein C deficiency (33.3%) |

Acute febrile illness - 2 (66.7%), septicemia - 1 (33.3%) | 33.3% | 33.3% | 1 patient (33.3%) succumbed to death. |

| Parikh et al. (1988)[14] n=4 | Not mentioned | Male=Female | Infectious (100%) | Meningitis - 3 (75%), postoperative septicemia - 1 (25%) | 100% | 100% | 3 patients (75%) succumbed to death. |

| Gurgey et al. (2005)[1] n=16 | 3.5 months to 12 years | Female > Male | Infectious (56%), Idiopathic (37.5%), Protein S deficiency -1 (6%). | Sudden-onset shock syndrome - 4 (25%), meningitis - 3 (18.8%), postprocedural sepsis - 2 (12.5%), following interventional procedure for congenital heart disease - 2 (12.5%), systemic lupus erythematosus - 1 (6.3%), familial hypercholesterolemia with a recent arteriovenous fistula application - 1 (6.3%), fever of unknown origin - 1 (6.3%) | 90% | 68.8% | None of the patients died. Ten of the 16 patients (62.5%) underwent amputation. |

| Katoch et al. (2016)[12] n=4 | 6 months to 4 years | Female > Male | Infectious (100%) | Acute febrile illness - 4 (100%) | Not mentioned | 25% | None of the patients died. |

| Present study n=23 | 4 days to 78 years | Female > Male | Sepsis (87%), Idiopathic (13%), Protein C deficiency (4.3%) | Pneumonia - 6 (26.1%), sudden-onset shock syndrome - 5 (21.7%), urinary tract infection - 4 (17.4%), cellulitis - 4 (17.4%), dilated cardiomyopathy with low cardiac output and congestive cardiac failure - 1 (4.3%), postoperative fever - 1 (4.3%), puerperal sepsis following cesarean section - 1 (4.3%), convulsions -1 (4.3%) | 100% | 34.8% | 10 patients (43.5%) succumbed to death. Two (4.3%) patients underwent amputation |

Demography

The present study shows that purpura fulminans spares no age group, which was also supported by the previous studies. While, in conformity with the previous case series of Gurgey et al.[1] and Katoch et al.,[12] a female preponderance was noted in the present series, a male predominance among cases were documented by Davis et al.[5] and Talwar et al.[13]

Etiology

In spite of the devastating clinical outcome associated with this condition, the mechanism of PF remains poorly understood. Severe acquired deficiency of protein C and dysfunction of the protein C-thrombomodulin pathway as well as other systems that exert a negative regulatory effect on coagulation have been hypothesized.[7,11] Three distinct subsets of PF can be recognized, namely inherited or acquired abnormalities of the protein C or other coagulation systems, “acute infectious” PF, and “idiopathic.”[3,4]

Neonatal PF may also result from deficiency of protein S and antithrombin III, the other regulators of the coagulation pathway.[7,13]

Acute infectious purpura fulminans, the most common form, occurs superimposed on a bacterial, viral, rickettsial, or parasitic infection. The most common cause of acute infectious purpura fulminans is meningococcus. However, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Group A and B streptococci, Enterococcus faecalis, Haemophilus influenzae, Haemophilus aegyptius, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella pneumonia, Escherichia coli , Proteus spp (mirabilis, vulgaris), Pseudomonas spp, Acinetobacter calcoaceticus, Xanthomonas maltophilia, Vibrio spp, Salmonella paratyphi, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Capnocytophaga canimorsus, Rickettsia rickettsii, and Plasmodium falciparum may also be associated with this form of purpura fulminans.[2,7] The pathogenesis of acute infectious cases is linked to enhanced expression of the natural procoagulants and depletion of the natural anticoagulant proteins particularly protein C.[2]

Idiopathic purpura fulminans[3] is classically preceded by a bacterial or viral infection and occurs after a variable latent period. Protein C deficiency is considered pivotal to the pathogenesis of idiopathic purpura fulminans, and DIC is the main pathophysiologic mechanism responsible for the development of peripheral gangrene. However, the precise mechanism of DIC in case of purpura fulminans remains elusive and probably multifactorial in origin.

In addition to its anticoagulant function, protein C may play a significant role in the pathophysiology of intravascular coagulation. In cases of DIC associated with sepsis, a decrease in plasma protein C antigen and its activity have been noted.[3,11]

In the present series, 87% patients had sepsis. Several previous studies also showed that infections are the most common cause of purpura fulminans.[1,5,12,14] Pneumococcus was the most common pathogenic organism detected and was found in 26.1% patients in the present series.

In previous studies, the most common pathogenic organism detected were Meningococcus (25%, Davis et al.)[5] and Staphylococcus (18.8%, Gurgey et al.).[1] In the present series, one patient (4.3%) with pneumococcal sepsis additionally had dilated cardiomyopathy with low cardiac output and congestive cardiac failure. In this context, it is noteworthy that a low-flow state with DIC is commonly present in the causation of purpura fulminans and symmetrical peripheral gangrene. All patients of the present study had DIC. In comparison, DIC was found in 33.3%,[13] 90%,[1] 91.7%,[5] and 100% (Parikh et al.)[14] patients in the previous reports.

Peripheral gangrene

In the current study, peripheral gangrene was seen in eight (34.8%) patients. A similar occurrence of gangrene was also noted by Talwar et al. (33.3%)[13] and Katoch et al. (25%).[12] On the contrary, a higher rate of peripheral gangrene was seen by Davis et al. (100%),[5] Parikh et al. (100%),[14] and Gurgey et al. (68.8%).[1] However, the higher rate may be attributable to the different selection criteria of the study by Davis et al. as they have included only patients of purpura fulminans with symmetrical peripheral gangrene.[5]

Clinical presentation

All the patients presented with hemorrhagic skin rashes. The other presenting conditions in the present study were pneumonia (26.1%), sudden-onset shock syndrome (21.7%), urinary tract infection (17.4%), cellulitis (17.4%), dilated cardiomyopathy with low cardiac output and congestive cardiac failure (4.3%), postoperative fever (4.3%), puerperal sepsis following cesarean section (4.3%), and convulsion (4.3%). One patient had history of rheumatoid arthritis.

Davis et al.[5] reported that sudden-onset shock syndrome (25%), pneumonia (25%), urinary tract infection (8.3%), pharyngitis (8.3%), shock following dog bite (8.3%), small-cell lung cancer (8.3%), postoperative sepsis (8.3%), and abdominal compartment syndrome (8.3%) were the presenting features in their series. In their study, Gurgey et al. reported that sudden-onset shock syndrome (25%), meningitis (18.8%), postprocedural sepsis (12.5%), following interventional procedure for congenital heart disease (12.5%), systemic lupus erythematosus (6.3%), familial hypercholesterolemia with a recent arteriovenous fistula application (6.3%), and fever of unknown origin (6.3%) were the presenting features.[1]

Typical hematological findings occur early in the course of PF and may include low concentrations of fibrinogen, clotting factors, and platelet as a result of their consumption, and prolonged prothrombin and partial thromboplastin times.[4] Fibrinogen degradation products tend to be raised and concentrations of proteins C, S, and antithrombin III get reduced. Fever and leukocytosis with a left shift are common despite the absence of acute infection.[4] Development of DIC may occur at any point of time in case of PF.

In the present series, all patients had developed DIC which further supported the view that DIC was the final common pathway in all cases of PF and SPG.[15]

Outcome

A higher rate of amputation was reported by Gurgey et al. (62.5%)[1] and Davis et al. (66.7%),[5] which is in contrast with an amputation rate of 8.6% in the present series. However, the high amputation rate in the study of Davis et al. may be a reflection of the inclusion criteria, since only patients with both purpura fulminans and peripheral gangrene were included in their study.[5]

Death

In the present study, the mortality rate was 43.5%. Variable mortality rate was noted by Parikh et al. (75%),[14] Talwar et al. (33.3%),[13] and Davis et al. (25%).[5] No deaths were observed by Gurgey et al.[1] and Katoch et al.[12] Another noteworthy finding of our study was that 87.5% of the patients who developed peripheral gangrene died and 40% of them had leucopenia with neutropenia. Similar observation was also made by Davis et al.[5]

Management

PF is a life-threatening disease with high mortality and significant long-term morbidity among the survivors. It requires prompt recognition and immediate treatment of the underlying cause and of the ongoing hemostatic abnormalities to prevent permanent disability and death. Unfortunately, there is little evidence to direct clinical decision-making.[11]

The patients with PF should get supportive management in intensive care or burn center setting and treatment of the underlying cause of DIC is of paramount importance.[2,5,8,16] A multidisciplinary approach including physicians, vascular and plastic surgeons, critical care specialists, and dermatologists should be undertaken. Normal saline resuscitation restores volume and promotes the urine output >0.5 ml/kg/hour.[6] Management of DIC requires replacement of the depleted coagulation factors if bleeding is the predominant feature.[5] Most clinicians prefer to provide platelet replacement if platelet counts drop below 20,000/ml.[6] On the other hand, if thrombosis is the principal presentation, institution of heparin or antithrombin 3 did not prove to be of much benefit.[5,6] Zymogen protein C concentrates or recombinant activated protein C, plasmapheresis, intravenous immunoglobulin, continuous plasma ultrafiltration, and continuous veno-veno hemofiltration show variable benefits.[4,5,6,11,16] Management of the associated peripheral gangrene needs avoidance of vasopressors (to avoid exacerbation of gangrene) and padding vascular boots.

Amputation should be postponed until gangrene has demarcated and acute purpura fulminans/DIC has stabilized or resolved.[2,5,17] Anticoagulation and antiplatelet medications (e.g., aspirin), epoprostenol (a prostaglandin-platelet inhibitor/vasodilator), tissue plasminogen activator, sympathetic blockade, plasmapheresis, and leukapheresis were also tried.[5] Fasciotomy, if needed, may limit the level of amputation.[17] Skin grafting may also be needed depending on the clinical status of the patients.[2]

Limitations

In the present study, a probable referral bias was present leading to only the serious patients with prominent cutaneous changes being referred. In addition, autopsy examination could not be done in any of our patients which remained as a limitation of the present study.

Conclusion

The present study emphasizes that purpura fulminans is a cutaneous marker of DIC. PF is a serious medical emergency, often requiring major amputation. Association of peripheral gangrene, leucopenia, and neutropenia with purpura fulminans increases the mortality rate.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Gürgey A, Aytac S, Kanra G, Secmeer G, Ceyhan M, Altay C. Outcome in children with purpura fulminans: Report on 16 patients. Am J Hematol. 2005;80:20–5. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betrosian AP, Berlet T, Agarwal B. Purpura fulminans in sepsis. Am J Med Sci. 2006;332:339–45. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200612000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adcock DM, Brozna J, Marlar RA. Proposed classification and pathologic mechanisms of purpura fulminans and skin necrosis. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1990;16:333–40. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1002686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nolan J, Sinclair R. Review of management of purpura fulminans and two case reports. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:581–6. doi: 10.1093/bja/86.4.581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis MD, Dy KM, Nelson S. Presentation and outcome of purpura fulminans associated with peripheral gangrene in 12 patients at Mayo Clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:944–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Dutta A. Purpura fulminans: A cutaneous marker of disseminated intravascular coagulation. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:41. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, editors. Andrew's Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 11th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D, Ghosh A. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene: A prospective study of 14 consecutive cases in a Tertiary-care hospital in Eastern India. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereo. 2010;24:214–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levi M, Toh CH, Thachil J, Watson HG. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of disseminated intravascular coagulation. British committee for standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spicer TE, Rau JM. Purpura fulminans. Am J Med. 1976;61:566–71. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90339-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colling ME, Bendapudi PK. Purpura fulminans: Mechanism and management of dysregulated hemostasis. Transfus Med Rev. 2018;32:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2017.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katoch S, Kallappa R, Shamanur MB, Gandhi S. Purpura fulminans secondary to rickettsial infections: A case series. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2016;7:24–8. doi: 10.4103/2229-5178.174324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talwar A, Kumar S, Gopal MG, Nandini AS. Spectrum of purpura fulminans: Report of three classical prototypes and review of management strategies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:228. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.93655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Parikh DA, Fernandez RJ, Bhatia SJ, Karand DR, Dastur FD. Purpura fulminans. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1988;54:30–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaudhary SC, Kumar V, Gupta A. Purpura fulminans: A rare presentation of a common disease. Trop Doct. 2010;40:238–9. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.100049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh SK, Bandyopadhyay D. Symmetrical peripheral gangrene. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2011;77:244–8. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.77481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Warner PM, Kagan RJ, Yakuboff KP, Kemalyan N, Palmieri TL, Greenhalgh DG, et al. Current management of purpura fulminans: A multicenter study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2003;24:119–26. doi: 10.1097/01.BCR.0000066789.79129.C2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]