Graphical abstract

Keywords: RNA extraction, SARS-CoV-2, rRT-PCR, Oro- nasopharyngeal swabs

Highlights

-

•

Alternative suitable methods to extract SARS-CoV-2 RNA should be taken into account to cope with the ongoing pandemic.

-

•

Extraction efficiencies of different viral RNA kit brands can be optimized for detection of SARS-CoV-2 genome.

-

•

The accuracy and performance of the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay can be further improved.

-

•

New optimized primer pairs for the N gene, considering its variability and stability, are highly recommended.

Abstract

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is the etiologic agent of the COVID-19 pandemic. Although other diagnostic methods have been introduced, detection of viral genes on oro- and nasopharyngeal swabs by reverse-transcription real time-PCR (rRT-PCR) assays is still the gold standard. Efficient viral RNA extraction is a prerequisite for downstream performance of rRT-PCR assays. Currently, several automatic methods that include RNA extraction are available. However, due to the growing demand, a shortage in kit supplies could be experienced in several labs. For these reasons, the use of different commercial or in-house protocols for RNA extraction may increase the possibility to analyze high number of samples. Herein, we compared the efficiency of RNA extraction of three different commercial kits and an in-house extraction protocol using synthetic ssRNA standards of SARS-CoV-2 as well as in oro-nasopharyngeal swabs from six COVID-19-positive patients. It was concluded that tested commercial kits can be used with some modifications for the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 genome by rRT-PCR approaches, although with some differences in RNA yields. Conversely, EXTRAzol reagent was the less efficient due to the phase separation principle at the basis of RNA extraction. Overall, this study offers alternative suitable methods to manually extract RNA that can be taken into account for SARS-CoV-2 detection.

1. Introduction

At the end of 2019, Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a highly infectious disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was firstly reported in Wuhan, China and rapidly spread from its origin to other countries throughout the world (Zhu et al., 2020). SARS-CoV-2 infection is transmitted from human to human mainly through respiratory droplets and aerosol as well as direct or indirect contact (Worldometers, 2020). COVID-19 patients are the main source of transmission, whereas asymptomatic and pre-symptomatic infected persons might also be potential sources of infection (Bai et al., 2020; Furukawa et al., 2020; Pan et al., 2020; Rothe et al., 2020). These features may explain the sudden epidemic spreading of the virus. Although several efforts are being focused on fast development of novel rapid and reliable diagnostic tests, to date, real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) based assays on respiratory specimens is still considered the gold standard to detect SARS-CoV-2- infection (WHO, 2020a). rRT-PCR is highly sensitive and specific and, compared to other available viral detection methods (e.g. viral antigen detection, standard plaque assay, serology, electron microscopy), is significantly faster with a lower potential for contaminations and/or errors. Undoubtedly, rRT-PCR performance can be greatly affected by the efficiency of the viral RNA extraction procedures. Several methods are used in molecular biology to isolate RNA from samples, such as the guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform and anion-exchange resin extractions. Thus, many commercial kits exploit these methods to allow a fast, sensitive and reproducible detection of viral RNA. However, SARS-CoV-2 infection has challenged, in every aspect, the global health systems including the ability to quickly provide reagents to labs around the world for molecular diagnostic tests. In this scenario, although rRT-PCR is the most valuable, computerized tomography (CT) scans of lungs have been used to overcome the shortening of rRT-PCR supplies (Hozhabri et al., 2020; Prezioso et al., 2020). However, COVID-19 diagnosis by CT scans was often difficult in asymptomatic patients and increases the risk of false-negatives. In a pandemic period, when the shortage of diagnostic kits is predictable, the worldwide sharing of different protocols for RNA extraction and gene amplification among laboratories is strongly required. Along this line, reliable protocols for viral RNA extraction are crucial for those molecular laboratories not equipped with automated nucleic acid extraction systems. Therefore, the present study is aimed at evaluating and optimizing the recovery of SARS-CoV2 RNA from nasopharyngeal swabs using three different commercial kits as well as providing a suitable in-house extraction protocol. After protocol optimization, the four methods were evaluated and compared using different concentrations of two synthetic ssRNA standards of SARS-CoV-2 (EURM-019 single stranded RNA, 2020) and Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (Seegene, Seoul, South Korea) and an in-house rRT-PCR (CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) for detection. The performance of the analyzed methods was also tested on positive clinical specimens.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Specimen collection

Nasopharyngeal rayon swabs (Cod. 26061 Rayon) were sampled according to WHO guidelines (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331058). Swabs were placed in saline (0.9 % NaCl) and stored in appropriate containers for transport of biological samples in accordance with UN 3373 and transported to the laboratory of microbiology within one hour.

2.2. Ethical committee

The Iris -CoV-2 study entitled "Studio osservazionale di sorveglianza epidemiologica SARS-Cov2 su operatori sanitari e pazienti di una struttura di medicina riabilitativa” was approved by the Ethical Committee on March 25th, 2020. Written informed consent was provided by participants; enrolled subjects were: 100 real-life, 56 patients and 224 healthcare professionals from IRCCS San Raffaele, Pisana, Rome, Italy. Subjects were swabbed three times in a three-months follow-up; repeatedly screening for SARS- CoV-2 was chosen to contain SARS-Cov2 transmission.

2.3. Total RNA extraction

Two synthetic ssRNA, an 880 nt of SARS-CoV-2, and Australia/VIC01/2020 were used as positive controls to compare the performance of different extraction protocols (EURM-019 single stranded RNA, 2020; TWIST BIOSCIENCES for Australia/VIC01/2020, 2020, TWIST BIOSCIENCES for Australia/VIC01/2020, 2020). Control and total RNAs from nasopharyngeal swabs were extracted using Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany, Cat.61704), Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I (Fisher Molecular Biology, Rome, Italy, Cat. DR-003), Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen, Rome, Italy, Cat. # 17200) and EXTRAzol (BLIRT S.A., Gdańsk, Poland, Cat. EM30-100).

2.4. rRT-PCR conditions

Probes used to detect the E gene, RdRP gene, N gene and the internal control (IC) were in FAM, Cal Red 610, Quasar 670 and HEX channels, respectively (Allplex™2019-nCoV Assay, Seegene, Seoul, South Korea). The IC (10 or 15 μL) was added to samples before starting the extraction protocols. Reaction and amplification conditions were performed according to the manufacturer's specifications (Seegene). Briefly, eight microliters (μL) of synthetic RNA standards or extracted RNA were added to 17 μL of the reaction mixture. Each 25 μL reaction mixture contained 5 μL of 2019-nCoV MOM, 5 μL of RNase-free Water, 5 μL of 5X Real-time One-step Buffer and 2 μL of Real-time One-step enzyme. Reactions were incubated at 50 °C for 20 min and 95 °C for 15 min followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 15 s and 58 °C for 30 s. Then, the samples were subjected to melting curve analyses (95 °C for 5 s and 65 °C for 1 min followed by a gradual increase in temperature to 97 °C with continuous recording of fluorescence) to test the specificity of the assay. Results were considered valid only when the cycle threshold (Ct) value of the reference gene was ≤ 40 (Seegene). The results were considered positive when the Ct values of even one single target genes were ≤ 40, negative when > 40 (Seegene). On the other hand, probes and primers recognize and amplify three regions of the virus nucleocapsid (N) gene (named N1, N2 and N3), plus an additional primer/probe set to detect the human RNase P gene (RP) representing a control for sample integrity and retro-transcription (CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2020) (Table S1). Reactions were carried on using SensiFAST™ Probe No-ROX One-Step Kit (Bioline Meridian BioScience, USA). Briefly, 4 μL of sample were added to 16 μL of the reaction mixture, each 20 μL containing 10 μL 2x SensiFAST Probe No-ROX One-Step Mix, 0,8 μL of each primer, 0,2 μL probe, 0,2 μL Reverse transcriptase, 0,4 μL RiboSafe RNase inhibitor, 3,6 μL RNase-free Water (Bioline Meridian BioScience, USA). Reactions were incubated at 45 °C for 10 min and 95 °C for 2 min followed by 45 cycles at 95 °C for 5 s and 60 °C for 20 s. All the reactions were performed using a CFX96 Dx System (Bio-Rad, Milan, Italy).

3. Results

3.1. Analytical Efficiency and Sensitivity (Limits of Detection) on positive standards

Two different quantified synthetic ssRNA standards for SARS-CoV-2 were prepared by serial 10-fold serial dilutions in RNAse free water, Australia/VIC01/2020 SARS-CoV-2 RNA and EURM-019 (EURM-019 single stranded RNA, 2020; TWIST BIOSCIENCES for Australia/VIC01/2020, 2020, TWIST BIOSCIENCES for Australia/VIC01/2020, 2020). Dilutions ranged from 2 × 10° to 2 × 107 copies/μl. After dilution, both standards were tested in one step rRT-PCR using Allplex 2019-nCoV assay, a multiplex for simultaneous detection of the envelope (E) gene, RNA-dependent RNA polymerase gene (RdRp), and nucleocapsid (N) gene and using the US CDC panel for detection of SARS-CoV-2 which detects three regions of the virus nucleocapsid (N) gene, named N1, N2 and N3 (Table S1). A linear amplification was achieved over a 6-log dynamic range from 2 × 101 to 2 × 107 copies/μl for the two assays; calculated PCR efficiency, by means of the following formula E = 10(−1/slope) (Rasmussen, 2001), of each standard ranged from 103,3 % to 113,5 % using Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (Fig. 1 A and B), and from 105,0 % to 107,9 % using the US CDS panel assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1C and D). Noteworthy, the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay couldn’t detect the N gene within the synthetic ssRNA standard for SARS-CoV-2 EURM-019, while it was detected by all sets of primers of the US CDC panel for detection of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1D). The limit of detection (LoD) was 2 × 101 copies/μl (Fig. 1). Based on the data from standard curve estimations, two different amounts, 2 × 102 and 8 × 105 copies, were arbitrary chosen to compare the efficiency of RNA recovery from different extraction methods.

Fig. 1.

Linear regression analysis of serial 10-fold serial dilutions of two synthetic ssRNA standards for SARS-CoV-2, ranging from 2 × 101 to 2 × 107 copies/μl. Dilutions from 2 × 10° to 2 × 107 copies of (A) Australia/VIC01/2020 SARS-CoV-2 RNA and (B) EURM-019 were tested by rRT-PCR using the Allplex 2019-nCoV (E, RdRp and N genes). The same 10-fold dilutions of (C) Australia/VIC01/2020 SARS-CoV-2 RNA and (D) EURM-019 were analyzed using the US CDS panel assays for detection of SARS-CoV-2 (N gene detected by primer pairs for N1, N2 and N3). The linear regression analysis is shown only for the N1 primer pair. For each assay, the linear correlation coefficients, PCR efficiency E = 10(−1/slope), R2 and slope were calculated.

3.2. Evaluation and comparison of RNA extraction methods by rRT-PCR

Four extraction methods were chosen, Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit, Total RNA Purification Kit, Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I, and EXTRAzol (see the Material and Methods section for details). RNA extractions were performed using synthetic standards for SARS-CoV-2, at two amounts previously chosen (2 × 102 and 8 × 105 copies), following their respective manufacturer's instructions. The elution volume was 50 μL for all extractions. The extraction efficiency of each kit was compared by rRT-PCR testing, using Allplex 2019-nCoV assay and the US CDC panel for detection of SARS-CoV-2. In the first rRT-PCR round, no signal could be detected using the Total RNA Purification Kit, while variable Ct values were observed for the IC using the other extraction methods. Therefore, we introduced and/or extended some steps to the provided protocols to improve the performance of the extraction methods, as summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Modifications introduced to optimize RNA extractions with respect to manufacturers’ instructions using known amounts of the synthetic ssRNA standard for SARS-CoV-2 (https://crm.jrc.ec.europa.eu/p/EURM-019).

| Method | Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit | Total RNA Purification Kit | Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I | EXTRAzol |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Starting sample | 200 μL | 200 μL | 200 μL | 200 μL |

| Starting buffer | AL buffer 200 μL | RL buffer 250 μL | VNE buffer560 μl | EXTRAzol 750 μL |

| Internal control (IC) μla | 10 μL | 15 μL | 10 μL | 10 μL |

| Protease K | 25 μL | None | None | None |

| Centrifugation step before elution | 2 min | 2 min | 1 min | None |

| Ethanol evaporation | 56 °C for 3 min | 56 °C for 3 min | None | 56 °C for 5 min |

| Elution volume | 50 μL | 50 μL | 50 μL | 50 μL |

| Elution time | 2 min | 5 min | 1 min | N/A |

| Centrifugation step | 2 min @20,000 x g | 5 min @ 6000 x g 2 min @ 14,000 x g |

2 min @ 18,000 x g | None |

| Time per prep | 35 min | 25 min | 26 min | 65 min |

The internal control (RP-V IC), composed of MS2 phage genome, is included to verify all steps of the analysis process in each sample.

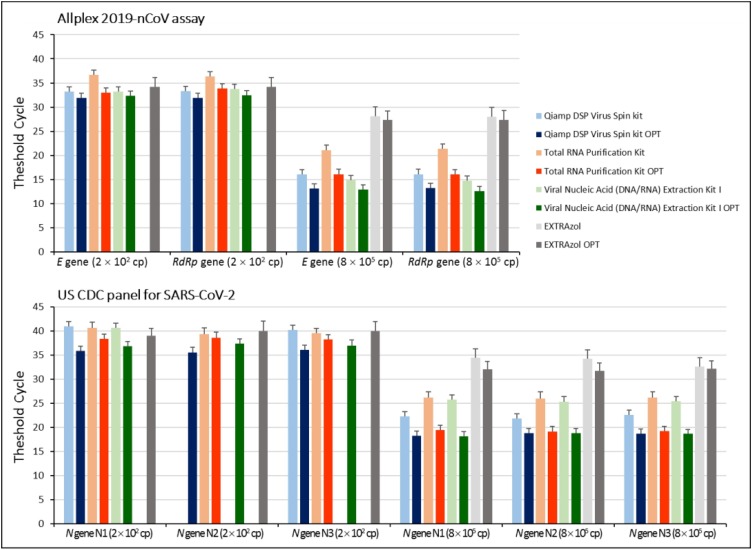

Main changes made to manufacturers’ instructions were extending timing of ethanol evaporation, elution incubation and centrifugation. The amount of IC was increased to achieve its detection in rRT-PCR, using Total RNA Purification Kit. Thus, RNA extractions were performed again accordingly to the modified protocols and analyzed by both rRT-PCR assays in comparison to those performed following manufacturer's instructions. Results showed that by applying even slight modifications the RNA yield improved in all four methods, as evidenced by the lower Ct values obtained in each viral gene amplification. However, some differences in RNA yield were observed among the four extraction methods likely depending on the amount of the starting standard RNA. Specifically at the lowest amount (2 × 102 copies), the Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit OPTIMIZED (OPT) yielded the lowest Ct values (most sensitive) for both rRT-PCR assays (Fig. 2 ), followed by the Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I OPT, Total RNA Purification Kit OPT and EXTRAzol OPT (Fig. 2), suggesting that extraction with Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit OPT resulted in an higher amount of RNA. On the other hand, at the highest amount (8 × 105 copies), the Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I OPT yielded the lowest Ct values, followed by Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit OPT, Total RNA Purification Kit OPT and EXTRAzol OPT (Fig. 2), suggesting that Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) extraction performance improves with viral RNA amount. However, according to relative Ct values, Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I OPT and Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit OPT extraction protocols showed almost superimposable efficiency. As expected, no amplification product was obtained for the N gene.

Fig. 2.

Quantitative comparison of RNA extraction methods. Known amounts of synthetic ssRNA standard for SARS-CoV-2 were extracted using the four described methods, both following manufacturers ‘instructions and using the optimized protocols (OPT). Samples were analyzed by rRT-PCR, using Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (E, RdRp and N genes) and US CDC rRT-PCR panel (three gene regions of the N gene, designated N1, N2, and N3). Average values calculated from three independent experiments performed in duplicate are reported. Missing bars correspond to >40 Ct for Allplex 2019-nCoV assay or negative for the US CDC panel for SARS-CoV-2. Cp, copies.

3.3. Validation on serially diluted specimens confirmed as COVID-19 positive

Among the 56 oro-nasopharyngeal swabs collected from patients admitted at the IRCCS San Raffaele Pisana Rome, Italy, six were found positive. Positivity to SARS-CoV-2 was also laboratory-confirmed by the local Azienda Sanitaria Locale (ASL) ASL ROMA 3 (Italian Local Health Authority). Samples in saline were extracted with the four methods, following manufacturer’s instructions and the optimized extraction protocols. Extracts were analyzed by both rRT-PCR assays, run in parallel with synthetic RNA standards for SARS-CoV-2. Results were in agreement with our previous data on the extraction with synthetic standards, showing an improvement in RNA extraction yield (corresponding to lower Ct values) for the OPT protocols using both rRT-PCR approaches (Fig. 3 ). However, although both rRT-PCR methods are highly sensitive for the detection of RNAs, the extraction efficiency influences significantly the yield of RNA, thereby it represents the most important variable to detect the presence of SARS-CoV-2 genome. Indeed, optimization was crucial in those clinical specimens in which detection for the target genes occurred at high Ct (Fig. 3, PZ 3, 4 and 6). Intriguingly, differently from what observed with the synthetic ssRNA EURM-019, the N gene in clinical specimens was detected by Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Quantitative comparison of SARS-CoV-2 RNA extraction from clinical swabs. RNA was extracted from oro-nasopharyngeal swabs from six patients (PZ) using the four described methods, both following manufacturers ‘instructions and using the optimized protocols (OPT). Samples were analyzed by rRT-PCR, using Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (E, RdRp and N genes) and US CDC rRT-PCR panel (three gene regions of the N gene, designated N1, N2, and N3). Average values calculated from three independent experiments performed in duplicate are reported. Missing bars correspond to >40 Ct for Allplex 2019-nCoV assay or negative for the US CDC panel for SARS-CoV-2.

4. Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic is still ongoing worldwide, causing severe illness and death (Worldometers, 2020). Although several antigen-detecting rapid diagnostic tests have been developed (WHO, 2020b), detection of viral RNA by rRT-PCR from oro-nasopharyngeal swabs is still the method more sensitive to confirm SARS-CoV-2 suspected infections (Hozhabri et al., 2020; Zou et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020). However, although rRT-PCRs were proven to be efficient and sensitive approaches for COVID-19 diagnosis, the extraction efficiency influences significantly the yield of RNA. Thus, the method used for RNA extraction is the most important variable to determine the positivity of sample for SARS-CoV-2 genome, especially for those labs that are not equipped with automated nucleic acid extraction systems. Therefore, labs using manual (non-automated) RNA extraction methods for COVID-19 diagnosis should choose reliable extraction kits; however, these kits could be in supply shortage being in great demand. To overcome this problem, herein we provide optimized protocols for Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit (Qiagen), Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen), Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I (Fisher) and the EXTRAzol as in-house extraction approach. Key steps in RNA extraction were proper ethanol evaporation, to minimize downstream rRT-PCR interference, and extended timing in elution incubation and centrifugation steps, to enhance RNA recovery. The Qiamp DSP Virus Spin kit and Viral Nucleic Acid (DNA/RNA) Extraction Kit I showed a comparable performance, especially using the optimized protocols. On the other hand, Total RNA Purification Kit performance was lower compared to the other two commercial kits and only the optimized protocol allowed to achieve a good efficiency of RNA extraction. Although the wide availability of EXTRAzol, this in-house approach was proven to be the less efficient. These results were predictable since commercial kits exploit the binding capacity of silica-gel affinity columns to selectively entrap, allowing the elution of RNA from samples. Vice versa, the guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform extraction technique is based on the principle that under acidic conditions RNA remains in the aqueous phase, whereas DNA and proteins are captured within the interphase or in the lower organic phase, favoring its recovery by precipitation with isopropanol (Chomczynski and Sacchi, 2006). As a matter of fact, the efficiency of isolated RNA by EXTRAzol is lower than that extracted by column-based methods. Therefore, caution should be exercised for the detection of SARS‐CoV‐2 with EXTRAzol, since in the presence of low or very low viral loads it can go undetected.

The rRT-PCR assays to detect SARS-CoV-2 were developed to detect genus- and species-specific targets. Among those, the N gene was chosen because it is highly abundant during viral replication and conserved among coronaviruses (Moreno et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2020). Detection of the N gene using the synthetic ssRNA standard EURM-019 and the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay failed; instead, it was appreciable using the US CDC rRT-PCR panel assay (Fig. 2). Being the sequence of the primer pair targeting the N gene under Seegene patent, we could not give a satisfactory explanation for the lack of its detection using EURM-019. Conversely, we observed amplification of this gene in clinical samples using the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay (Fig. 3). However, several labs reported cases in which the N gene was the only gene detected at high Ct (>36) which was, instead, undetectable by re-testing some subjects the day after (unpublished observations). Although conserved among coronaviruses, it has been shown that the N gene exhibited a great variability (Wang et al., 2020; Ceraolo and Giorgi, 2020; Dutta et al., 2020). Besides the variability of replicate specimens and of the run’s volume reactions, it can be hypothesized that the uncertainty on N positive results could be linked to a transient stage of virus-host contact and its transitory detection to its high abundancy. This aspect of SARS-CoV-2 infection deserves further investigations.

In conclusion, three of the four RNA extraction methods following the optimized protocols herein provided were proven to be useful for the detection of the SARS-CoV-2 genome by rRT-PCR approaches, although with some differences in the yield of RNA obtained for the Total RNA Purification Kit (Norgen). Due to the phase separation principle at the basis of RNA extraction, EXTRAzol reagent displayed constantly the lowest yield, likely affecting the performance of rRT-PCR. Thus, based on the results of this study, we strongly recommend that rRT-PCR assays should validate more brands for RNA extraction kits to deal with the great demand of them for community screenings and possible future outbreaks. Although the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay failed to detect the N gene within the ssRNA, its performance was accurate for clinical samples, as previously reported (Farfour et al., 2020). However, maximal caution is needed when detection of SARS-CoV-2 genes occurs at high Ct values, for which re-testing should be recommended. In addition, with the increasing knowledge on N gene sequence variability and stability, we do believe that the primer pair chosen for its detection by the Allplex 2019-nCoV assay should be optimized to increase further its performance and accuracy as well as avoiding false-positive results.

Note added in proof

During revision of this manuscript, Seegene developed a new commercial kit for rRT-PCR in which they changed the enzyme, probes, and amplicon sizes (N. cat. RV10248X).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Cecilia Ambrosi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Carla Prezioso: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Paola Checconi: Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Daniela Scribano: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Meysam Sarshar: Validation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing - review & editing. Maurizio Capannari: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing - review & editing. Carlo Tomino: Resources, Data curation, Funding acquisition. Massimo Fini: Resources, Project administration, Supervision. Enrico Garaci: Project administration, Supervision. Anna Teresa Palamara: Conceptualization, Data curation, Resources, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing - review & editing. Giovanna De Chiara: Validation. Dolores Limongi: Conceptualization, Methodology, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing - review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the infrastructure support provided by the IRCCS San Raffaele Pisana, 00166 Rome, Italy to perform this study.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research was funded by the Italian Ministry of Health (Ricerca corrente). C.P. and M.S. were supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (SG-2018-12366194 to C.P. and SG-2018-12365432 to M.S.). The salary of D.S. was supported by the Dani Di Giò Foundation-Onlus, Rome, Italy. The funders had no role in study design, analysis and interpretation of the data or in writing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2020.114008.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Bai Y., Yao L., Wei T., Tian F., Jin D.Y., Chen L., Wang M. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323:1406–1407. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC: Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/lab/rt-pcr-panel-primer-probes.html.

- Ceraolo C., Giorgi F.M. Genomic variance of the 2019-nCoV coronavirus. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:522–528. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. The single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction: twenty-something years on. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:581–585. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta N.K., Mazumdar K., Gordy J.T. The nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2: a target for vaccine development. J. Virol. 2020;94:e00647–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00647-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EURM-019 single stranded RNA (ssRNA) fragments of SARS-CoV-2. Available online: https://crm.jrc.ec.europa.eu/p/EURM-019.

- Farfour E., Lesprit P., Visseaux B., Pascreau T., Jolly E., Houhou N., Mazaux L., Asso-Bonnet M. Vasse, M.; SARS-CoV-2 Foch Hospital study group. The Allplex 2019-nCoV (Seegene) assay: which performances are for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis? Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2020;28 doi: 10.1007/s10096-020-03930-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa N.W., Brooks J.T., Sobel J. Evidence supporting transmission of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 while presymptomatic or asymptomatic. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020;26 doi: 10.3201/eid2607.201595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hozhabri H., Piceci Sparascio F., Sohrabi H., Mousavifar L., Roy R., Scribano D., De Luca A., Ambrosi C., Sarshar M. The global emergency of novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2): an update of the current status and forecasting. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2020:17. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno J.L., Zúñiga S., Enjuanes L., Sola I. Identification of a coronavirus transcription enhancer. J. Virol. 2008;82:3882–3893. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02622-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan X., Chen D., Xia Y., Wu X., Li T., Ou X., Zhou L., Liu J. Asymptomatic cases in a family cluster with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020;20:410–411. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30114-30116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prezioso C., Marcocci M.E., Palamara A.T., De Chiara G., Pietropaolo V. The "Three Italy" of the COVID-19 epidemic and the possible involvement of SARS-CoV-2 in triggering complications other than pneumonia. J. Neurovirol. 2020;26:311–323. doi: 10.1007/s13365-020-00862-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen R. Quantification on the LightCycler instrument. In: Meuer S., Wittwer C., Nakagawara K., editors. Rapid Cycle Real-Time PCR: Methods and Applications. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Press; 2001. pp. 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Rothe C., Schunk M., Sothmann P., Bretzel G., Froeschl G., Wallrauch C., Zimmer T., Thiel V., Janke C., Guggemos W., Seilmaier M., Drosten C., Vollmar P., Zwirglmaier K., Zange S., Wölfel R., Hoelscher M. Transmission of 2019-nCoV infection from an asymptomatic contact in Germany. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:970–971. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TWIST BIOSCIENCES for Australia/VIC01/2020: Available online: www.twistbioscience.com.

- Wang C., Liu Z., Chen Z., Huang X., Xu M., He T., Zhang Z. The establishment of reference sequence for SARS-CoV-2 and variation analysis. J. Med. Virol. 2020;92:667–674. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- WHO: World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/antigen-detection-in-the-diagnosis-of-sars-cov-2infection-using-rapid-immunoassays.

- Worldometers . 2020. Coronavirus Statistics.https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/transmission/ Available online. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T., Wu Q., Zhang Z. Probable pangolin origin of SARS-CoV-2 associated with the COVID-19 outbreak. Curr. Biol. 2020;30:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2020.03.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N., Zhang D., Wang W., Li X., Yang B., Song J., Zhao X., Huang B., Shi W., Lu R., Niu P., Zhan F., Ma X., Wang D., Xu W., Wu G., Gao G.F., Tan W. China novel coronavirus investigating and research team. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;(382):727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou L., Ruan F., Huang M., Liang L., Huang H., Hong Z., Yu J., Kang M., Song Y., Xia J., Guo Q., Song T., He J., Yen H.L., Peiris M., Wu J. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:1177–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.