Abstract

Background

People with developmental disabilities (DD) are a population at high-risk for poor outcomes related to COVID-19. COVID-19-specific risks, including greater comorbidities and congregate living situations in persons with DD compound existing health disparities. With their expertise in care of persons with DD and understanding of basic principles of infection control, DD nurses are well-prepared to advocate for the needs of people with DD during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective

To assess the challenges faced by nurses caring for persons with DD during the COVID-19 pandemic and how the challenges impact people with DD.

Methods

We surveyed 556 DD nurses, from April 6–20, 2020. The 35-item mixed-method survey asked nurses to rate the degree of challenges faced in meeting the care needs of people with DD. We analyzed responses based on presence of COVID-19 in the care setting and geographically. One open-ended question elicited challenges not included in the survey, which we analyzed using manifest content analysis.

Results

Startlingly, nurses reported being excluded from COVID-19 planning, and an absence of public health guidelines specific to persons with DD, despite their high-risk status. Obtaining PPE and sanitizers and meeting social-behavioral care needs were the most highly ranked challenges. COVID-19 impacted nurses’ ability to maintain adequate staffing and perform essential aspects of care. No significant geographic differences were noted.

Conclusions

DD nurses must be involved in public health planning and policy development to ensure that basic care needs of persons with DD are met, and the disproportionate burden of COVID-19 in this vulnerable population is reduced.

Keywords: Developmental disability, COVID-19, Nurse, Health policy

Introduction

Approximately 4.5 million people with developmental disabilities reside in the US1 and represent a population at high risk for severe health outcomes from COVID-19.2 Developmental disability (DD) represents a broad group of conditions that originate before age 22, are expected to last a lifetime, and result in significant impairments in physical or mental functioning, impacting day-to-day living and necessitating supports and assistance.3 Examples of DD include autism, cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, intellectual disability, and congenital blindness. Emerging data from states indicate that people with DD have higher case fatality rates from COVID-19 than people without disabilities. In New York, the COVID-19 case fatality rate for people with DD who are receiving services is 2.2 times higher than the overall COVID-19 case fatality rate.4 In New Jersey, more than a third of the 1238 people living in its five state-run residential facilities for people with DD have contracted the virus, which has already killed 27 people.5 A lack of national surveillance data related to people with DD challenges our understanding of the impact of COVID-19 among persons with DD in the US population. Data from the health records of 42 academic medical centers worldwide found that people with DD have a higher prevalence of comorbid conditions associated with poor COVID-19 outcomes and a higher case fatality rate at younger ages, as compared to persons without DD.6

These disparate COVID-19 outcomes are not surprising given the health disparities faced by people with DD at baseline prior to the pandemic, including poorer health outcomes,7 limited access to needed health care services,8 participation in fewer prevention and health promotion activities,7 increased risk for chronic health conditions,7 and earlier age of death when compared to the general population9 In addition, people with DD have a higher prevalence of specific comorbidities associated with poor outcomes from COVID-19, including diabetes, hypertension, heart disease and respiratory disease6. People with DD are more likely to be obese and experience polypharmacy,10 contributing to increased risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes.11 Mortality rates from pneumonia, a frequent complication of COVID-19, are also higher in people with DD compared with the general population.4 Furthermore, people with DD face high rates of hospitalizations and increased iatrogenic complications as compared to those without DD.12 Despite their vulnerable and high-risk status, our search in March 2020 of the CINAHL, MEDLINE, and PsychInfo databases identified no studies exploring the impact of COVID-19 in people with DD. Our search terms included: “COVID-19″ adding developmental disability, intellectual disability, disabilities, disabled person, person with disability, group home, and congregate living.

Models of care for people with DD have shifted over time in response to societal demands. Historically, people with DD were segregated from society in large, state-run institutions which often lacked adequate resources to meet the basic needs of people with DD and were characterized by pervasive, systemic neglect and abuse3. As a result of media exposure and class action lawsuits in the 1960’s and 1970’s, legal challenges to institutional care mounted and states were forced to find community-based alternatives to institutional care, a movement known as deinstitutionalization.13 The first federal support for DD care came in 1972 with the authorization of Intermediate Care Facilities for Intellectual Disabilities (ICF/IID).13 These Medicaid funded institutions consist of 4 or more beds for individuals with intellectual disability or related conditions and provide active health or rehabilitative services that meet specific standards of care.14 A major boon to the deinstitutionalization movement occurred with the passage of Medicaid Home and Community-based Service (HCBS) waivers, authorized in Section 2176 of the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1981.15 Prior to this time, the federal Medicaid program only paid for services if a person lived in an institution. The federal HCBS waivers allow states the flexibility to provide care in smaller, more individualized home and community-based settings, including group homes, supervised apartments, foster homes, supported living settings, and the family home.13 More specifically, the HCBS waivers allow for a wide range of health and human services to be provided in home and community-based settings, including, but not limited to skilled nursing care, occupational, physical, and speech therapies, personal care assistance, case management, legal and financial services, and habilitation (daily living skills) training in both day programs and residentially.16 All 50 states currently participate in the HCBS waiver program,13 and the majority of public funding for DD care is now provided through HCBS waivers.17

Unfortunately, the persistent health disparities faced by people with DD are illustrative of the large gap that remains to achieving equitable care for people with DD. The current health care system for people with DD residing in the community can be characterized as fragmented, uncoordinated, and difficult to access, with more heath care providers lacking appropriate education and training to meet the unique care needs of people with DD.18 The inability of community settings to adequately meet the needs of people with DD represents a social determinant of health, which are personal, social, economic and environmental factors that influence a population’s overall health status.7 DD nurses, as registered licensed and practical nurses who provide nursing care and support to individuals with DD,19 play a critical yet complex role in filling the health care gap for people with DD. DD nurses care for people with a wide scope of DD often accompanied by chronic co-morbidities and multifaceted care needs across a growing diversity of care settings.20 There are now as many DD care settings are there are places for people with DD to live, work, and recreate. DD nurses practice in public and private institutions, intermediate care facilities, schools, group homes, day habilitation centers, adult foster care and shared living arrangements, private homes, and more. Across all settings, the DD nursing role can be characterized by four overarching functions: direct care expert, care coordinator, interprofessional collaborator, and advocate and leader for equitable care.21 Ultimately, DD nurses act as an essential liaison between the disparate health care and disability service systems.

DD nurses also collectively face unique challenges in meeting the care needs of people with DD, including addressing stigma associated with people with DD, and ensuring that care is responsive to the unique needs of people with DD given the inadequate disability knowledge and training of the health care team20. DD nurses also face tension from within the disability community as they balance health care needs with concerns related to a medical model of care.20 The nursing profession as a whole is firmly established within a medical model of care, which views disability as an illness or abnormality within the individual, requiring expert healthcare professional intervention.20 The concern is that a focus on medical care needs will restrict the freedom of persons with DD to live, work, and recreate in the least restrictive setting. In reality, DD nurses’ practice is guided by a person and family-centered model of care,21 in which persons with DD and their families are equal partners in care decisions, and care is guided by the person’s unique situation, values, priorities, and goals.20

Given the high risks for COVID-19 faced by people with DD, and the critical yet complex role of the nurse in meeting care needs of persons with DD, the objective of this study was to assess the challenges faced by DD nurses in meeting the basic care needs of people with DD during the COVID-19 pandemic. The conceptual framework for this study was McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, and Glanz’s social ecological approach.22 According to this approach, individual, interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy-level characteristics interrelate and influence health outcomes.

Methods

Design

A convergent parallel mixed methods design was used,23 meaning that both quantitative and qualitative data were collected concurrently, through an on-line survey. We identified the need to compare and converge both types of data to gain insight into an unprecedented problem like pandemic impact and preparedness.

Sample and setting

The target population for this study was licensed or registered nurses currently providing, directing, consulting, or managing care of people with DD in the United States. Retired nurses, unlicensed student nurses or caregivers, and those not currently practicing DD nursing were excluded. Nurses were recruited via emails sent to all 954 nurse members of the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association.

Data collection

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Massachusetts Dartmouth. The email invitation consisted of an invitation to participate in an online study, a description of the study’s purpose, inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the link to the study. We also included a statement requesting the nurse share the email with other DD nurses in their personal and professional networks to minimize bias associated with all respondents belonging to a professional nursing organization. Implied consent was obtained from all participants based on a cover letter included on the first page of the survey that described the study and asked potential participants to click “yes” if they agreed to participate. Those who agreed to participate were then routed to the first page of the survey. The survey was open from April 6th to April 20th, 2020. A reminder was sent to all who did not open the email on April 10th, and a reminder was sent to all members at one week.

Measures

The survey was developed based on a review of the literature on disaster and emergency preparedness in persons with DD and guidelines from the American Association of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry.24 The survey was reviewed by a panel of 4 expert DD nurses for face and content validity. The final survey consisted of 35 items. Three items addressed demographic characteristics, including geographic region, type of care setting, and whether the agency has yet had an individual with DD test positive for COVID-19. Thirty-one items asked nurses to rate the degree to which they have faced or anticipate facing challenges in the care of persons with DD as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. These items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale anchored with endpoints 1-“not at all” to 5-“extreme” and were grouped into four care areas: health needs, social needs, service needs, and COVID-19 actions. One additional open-ended item asked nurses to list or describe any other challenges or anticipated challenges to meeting the needs of people with DD as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Data analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics described and analyzed the quantitative data using IBM SPSS software.25 All data were evaluated for applicable statistical assumptions. The statistical significance level was determined as 0.002 after applying a Bonferroni correction for 31 comparisons to an alpha level of 0.05. This means that we corrected for the increased potential of false positives (Type I statistical error) due to the large number of statistical tests performed by dividing the alpha level of 0.05 by the number of comparisons performed (0.05/31 = 0.0016). Because we were interested in the granularity in challenges faced by DD nurses and not summarizing an overall level of challenge, mean scores were calculated for each item and independent t-tests were used to compare mean item scores between those who had cared for an individual testing positive for COVID-19 and those who had not. ANOVA was used to test for statistically significant differences in the mean item scores based on geographic region. As we were not interested in characterizing an overall level of challenge faced by nurses, we did not sum the item scores to analyze as a scale, thus missing data was not a concern and all available data were analyzed for each item.

Manifest content analysis26 was applied to the open-ended survey responses. This qualitative data analysis approach seeks to describe the surface structure of the data, asking “What has been said”26. First, we catalogued all open-ended responses into a single spreadsheet file. Each member of the research team then read through all of the responses to become familiar with the data. Next, we individually identified examples of responses that related to and provided context for each survey item. We also individually coded and inductively organized responses that illustrated challenges that were not present in the survey items. The research team then met to identify consensus among the codes and compile codes into categories. In the last stage, we deductively organized the categories using the socioecological framework, by grouping the challenges faced by DD nurses into individual interpersonal, organizational, community, and policy-level categories22.

Results

Of the 954 email invitations sent to DDNA nurse members, we received 556 responses total, representing an approximate response rate of 58%. However, we are unable to discern which, if any, responses were garnered by DD nurses’ sharing the invitation within their personal and professional networks. At least 523 participants responded to each quantitative survey item, and 287 participants responded to the open-ended item. Respondents’ geographic region and area of practice are presented in Table 1 . The recruitment strategy yielded a higher number of nurses from the northeast region of the US and who work primarily in the group home setting. Just over a quarter of respondents (n = 146, 27.9%) indicated that a person with DD in their agency had tested positive for COVID-19, whereas the remaining nurses (n = 377, 72.1%) had not yet had a person in their agency test positive.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Region of Nursing Practice | 525 | |

| Northeast | 221 | 42.1 |

| South | 77 | 14.7 |

| Midwest | 157 | 29.9 |

| West | 70 | 13.3 |

| DD Practice Setting | 526 | |

| Hospital or medical center | 13 | 2.5 |

| Ambulatory clinic | 10 | 1.9 |

| Public residential institution or agency | 52 | 9.9 |

| Private residential institution or agency | 72 | 13.7 |

| Community-based group home | 195 | 37.1 |

| Adult foster care/shared living supervision | 8 | 1.5 |

| Private duty | 5 | 1 |

| More than one type of setting | 97 | 18.4 |

| Other, please specify: | 74 | 14.1 |

Responses included administration, case management, CBDS waiver program, day habilitation, preschool

Table 2 presents the 12 survey items with a mean score of three or greater, indicating a ‘moderate’ degree of challenge faced or anticipated by nurses. Obtaining an adequate supply of personal protective equipment and sanitizers was the primary challenge whether or not COVID-19 was present in the agency. The next four most highly ranked items all reflected social-behavioral considerations, including adequate day or educational programming, supporting or enabling socialization with family or friends, managing challenging behaviors, and practicing social distancing. In the open-ended responses, nurses described how in most cases it is difficult or impossible to help individuals with DD understand the rationale behind the use of PPE, social distancing, lack of outings, and other COVID-related changes, which contributes to emotional and behavioral challenges.

Table 2.

Joint display of challenges identified by nurses.

| Survey item | Mean | SD | Illustrative comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintaining an adequate supply of personal protective equipment (PPE) and sanitizers | 3.91 | 1.2 | this population is not considered as important … PPE … confiscated and sent elsewhere by the government. greatest challenge … availability of PPE … cleaning and sanitizing products … reserved for “health care workers”, as if we do not provide healthcare as a basic service. |

| Ensuring day programming or educational services | 3.54 | 1.3 | providing … worthwhile activities … to replace activities and socialization that would have come from … day program. disruption of normal routine … difficult consequence of this pandemic … anxiety-provoking … individuals who do not fully understand why they are not going to day program … out in the community … visiting their families. |

| Supporting or enabling socialization with family/friends | 3.41 | 1.2 | helping families grieve … can’t comfort their loved one through their end journey … even those unrelated to COVID encouraging families to visit via telephone/Face Time …. talk … over Zoom |

| Managing challenging behaviors (due to disruptions in home environment, daily schedules and usual activities) | 3.34 | 1.0 | lives have been completely disrupted … …stuck in their rooms most of the day … don’t understand … starting to really act out … increase in aggressive/difficult behaviors |

| Practicing social distancing | 3.27 | 1.1 | challenging to maintain social distancing with many people … impossible with others due to needs that require close physical contact. very hard to keep people occupied … closed up in their homes …. don’t have the capacity to fully understand … importance … reasoning behind it. |

| Ensuring access to regular rehabilitative therapies (speech, OT, PT, behavioral therapies) | 3.24 | 1.3 | Medication changes are needed … difficult to make without a face-to-face visit with a psychiatrist |

| Educating individuals with DD about COVID-19 and risk reduction strategies | 3.23 | 1.2 | difficult for them to understand the rules … went in with a mask on … said they hoped I would get better … try to help them understand … it goes nowhere. education and communication only go so far … not long after receiving education … go out in the community for something non-essential. |

| Ensuring adequate staffing of familiar support workers and caregivers | 3.18 | 1.2 | all of our clients home … no activities to keep them busy, our direct care staff is … overworked. overtaxing limited staff staffing is the most immediate issue … staff quit and do not want to be out in public due to covid 19 and … they do not come to work.” |

| Isolating/quarantining individuals with DD who test positive or are exposed to someone with COVID-19 | 3.13 | 1.4 | if a person … contract the virus … is admitted, where does he go after discharge? Can he safely go back home, how do we isolate … safely … keep other residents safe?” |

| Identifying/planning alternate entertainment activities (not including television) | 3.08 | 1.1 | finding activities for clients to do that are safe or that they want to do in our very small towns … asked to create a plan for social distancing when we go back to day habilitation services …. at a loss for what the environment will be when that happens … haven’t a clue what to plan for at this point in time |

| Meeting mental health care needs and providing emotional support | 3.05 | 1.1 | the most difficult challenges have been related to emotional support they are frustrated, confused, angry, disoriented, perplexed, bewildered, and every other adjective and do not know how to handle it |

| Meeting physical health care needs (ie. personal care, physical activity, safety protocols) | 3.02 | 1.1 | decreased mobility r/t isolation/quarantine. not being encouraged … go outside … get sunshine … exercise … nutritional diets … overlooked |

Note. Items included in table indicate a moderate degree of challenge or greater faced by nurses (Mean3).

Table 3 presents the results of independent samples t-tests comparing COVID positive and negative conditions. A key issue between the two groups was COVID-19 planning. Significant differences were noted in the ability to develop an emergency plan for an individual or agency, with significant associated challenges with contact tracing and quarantining suspected or confirmed cases. In the open-ended responses, several nurses reported that they were excluded from COVID-19 planning in their agencies and were advised to “stay out of staffing”. Significant differences were also noted in the ability to maintain adequate staffing levels for direct care staff and nursing. Open-ended responses revealed an overburdened DD workforce, with many staff working in multiple residences, leading to concerns of “cross-contamination” of staff and increased risk of COVID-19 for supported persons with DD.

Table 3.

Joint display of COVID condition in agency.

| Item | COVID+ |

COVID - |

Illustrative comment | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | df | t | ||

| Ensuring adequate staffing of familiar support workers and caregivers | 3.59 | 1.2 | 3.03 | 1.2 | 518 | 4.75 | Staffing for 7-3 since day programs are closed Familiar faces can’t go into the hospital |

| Practicing social distancing | 3.51 | .98 | 3.19 | 1.1 | 521 | 3.05 | Our residents do not know social distancing … Cannot count how many times a shift I have to “back individuals up from myself the nurse” … most of us 45yrs or older … very concerned most housemates … have difficulty with social distancing with one another … hugs come from around the corner before you know it! |

| Isolating/quarantining individuals with DD who test positive or are exposed to someone with COVID-19 | 3.51 | 1.2 | 3.01 | 1.5 | 518 | 4.05 | standard isolation precautions in a group home setting without … single rooms is extremely hard … main concern … someone test positive … keeping the rest of the house healthy … individuals will not stay in their room … poor hygiene. If one person contracts the virus, they will all get it. |

| Tracing contacts of individuals (both staff and client) testing positive for COVID-19 or who were exposed to someone who tested positive | 3.19 | 1.2 | 2.61 | 1.4 | 293.1 | 4.68 | we are having most difficulty tracking contacts “Cross contamination” … staff work for multiple agencies who provide direct care |

| Keeping staff home who have symptoms suggestive of COVID-19 or who do not have symptoms but who have been exposed to someone with COVID-19 | 3.08 | 1.2 | 2.60 | 1.3 | 274.5 | 3.81 | difficult to determine … to remove staff/isolate someone with symptoms (even just low-grade fever) not all staff … honest about symptoms … don’t want to be forced to stay home. |

| Ensuring access to nursing staff and supervision as needed/indicated | 2.98 | 1.3 | 2.51 | 1.3 | 520 | 3.79 | The biggest challenge … how much work time COVID 19 has consumed … grossly increased the daily work … all of the required changes no nursing visits unless EMERGENCY amount of calls and questions regarding COVID19 …. day-to-day assessments … affected … time it takes to follow up on … questions. coordination of administrative tasks in addition to nursing tasks already responsible for |

| Coordinating care between health organizations, including hospital, rehabilitation, and provider agencies | 2.95 | 1.1 | 2.54 | 1.2 | 276 | 3.79 | high risk of denial of admission or access to ICU level services d/t diagnosis of IDD Communication with hospitals has been difficult |

| Developing an emergency plan for an individual or agency | 2.88 | 1.2 | 2.46 | 1.2 | 521 | 3.55 | lack of cohesive guidance on how CDC … DPH guidelines should be implemented … DD setting, especially group home setting. Not having a plan of care for an individual that tested positive … most challenging |

Note. Items included in table indicate a statistically significant difference (p in mean score between COVID-19 conditions.

Illustrative examples from the qualitative data supporting the quantitative findings are included in Table 2, Table 3. There were no significant differences in item mean scores based on geographic region.

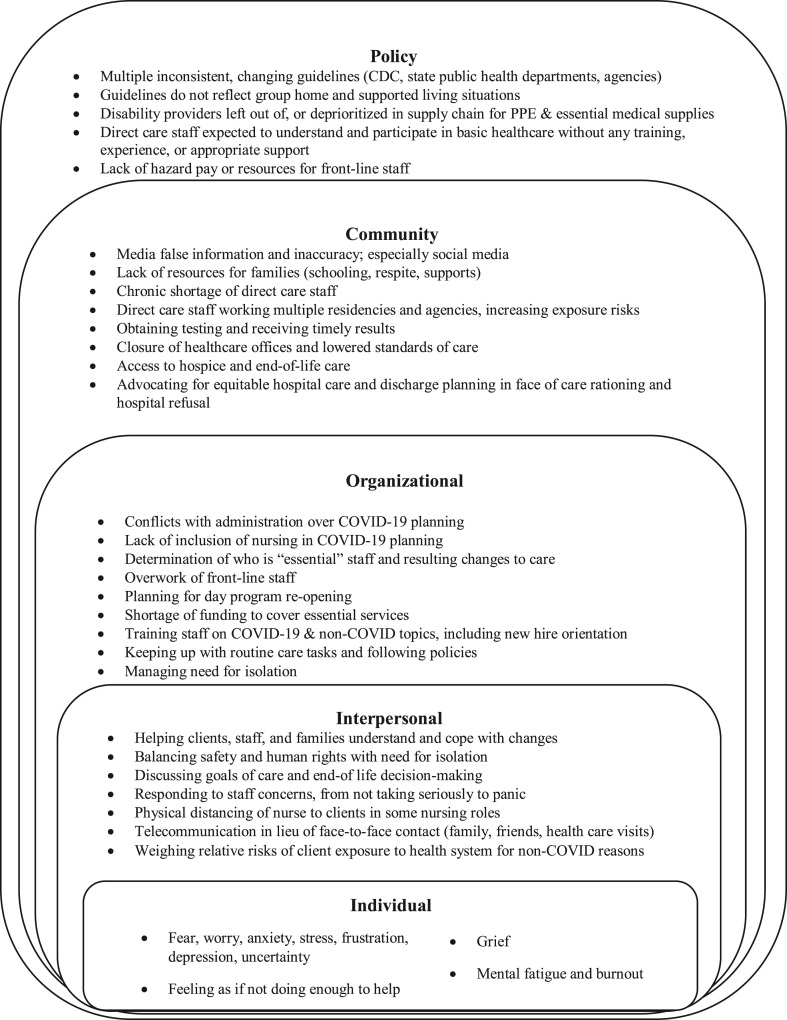

Challenges identified by the nurses’ open-ended responses were categorized according to socioecological level in Fig. 1 . The open-ended responses revealed challenges at all levels, with many challenges being experienced beyond the traditional clinical work setting of the nurse, involving organizational, community and policy-level influences. A critical challenge identified by the nurses is the lack of national and state policies and guidance specific to DD care settings.

Fig. 1.

Nurses’ multi-level challenges to meeting care needs of adults with DD

Discussion

Persons with DD are a high-risk and overlooked population during the COVID-19 pandemic. This theme is also noted in the disability-oriented press.27 , 28 Numerous multi-level challenges exist to the ability of DD nurses to meet basic care and support needs of people with DD. The pandemic has left DD nurses feeling stressed, fearful, depressed, and burned out, and simultaneously wishing they could do more to help. DD nurses are emotionally invested in the care they provide and struggle with balancing their passion and enthusiasm with stress, guilt over their limitations, and feeling devalued in their role even prior to a pandemic29. Nurses need ongoing support and strategies to address the physical and psychological impact of working during a pandemic,30 and this need extends to DD nurses who have been described as marginalized from the nursing specialty.20 In the words of one respondent “we are at the front line trying to keep consumers and staff safe and feel alone.” It is now more important than ever that DD nurses are supported physically and psychologically to practice at their fullest potential.

Beyond acquiring supplies of PPE and sanitizers, nurses identified that the greatest challenges faced were related to the interpersonal/social impact of COVID-19 on people with DD, as well as their caregivers and families. Nurses overwhelmingly identified helping people to understand as a critical aspect of their role, including helping people with DD and their support staff to understand the reasoning behind routine changes, visitation limitations, use of PPE, and social distancing. Helping people with DD to understand these changes is especially important as DD nurses described a dramatic increase in challenging behaviors as a result: “Basically everything we try to do, every day, turns into a challenge. Our individuals’ behavior(s) are exacerbated by having to remain home in close quarters, they are frustrated, confused, angry, disoriented, perplexed, bewildered, and every other adjective and do not know how to handle it. We are seeing behaviors we have never seen before, in people we have never seen them in before and staff are trying to cope and deal with them.” Along with an increase in challenging behaviors, increased use of psychiatric medications was reported, which given known polypharmacy risks in people with DD may contribute to additional risk for negative outcomes from COVID-19.11 In some instances, DD nurses’ ability to intervene was limited by physical distancing and decreased access to persons with DD in their homes. They described having to connect with people with DD over Zoom, and even managing client medications by having staff drop off and pick up medications outside the nurse’s home. Given that DD nurses possess a unique relational skill set31 characterized by a strong nurse-client relationship,29 continued access to a DD nurse is a critical resource to assist people with DD to cope with change in a healthy manner. DD nurses can provide leadership on programming to address mental health issues, reduce challenging behaviors associated with pandemic-related changes, and maintain a healthy, balanced lifestyle during the pandemic.

DD nurses also face challenges to meeting the needs of people with DD from within their employing organizations. Several nurses indicated that they are not involved in pandemic planning that takes place at their agencies and are even purposefully excluded and told to “stay out of staffing business”. This is particularly important as determinations about who is considered “essential personnel” are made for vulnerable persons with DD and complex health conditions residing in community settings by those with little health care knowledge or background. Furthermore, organizations are challenged to maintain adequate staffing and onboard new staff with appropriate hands-on training to care for people with complex needs during a pandemic, while social distancing necessitates only virtual trainings. As many health care offices are closed or limiting access due to COVID-19, and more complex care is being provided in home and community-based settings, it is imperative that persons with DD have access to the appropriate level of knowledgeable staff who are responsive to their unique needs.

Inopportunely, the chronic shortage of direct care staff in home and community-based settings32 is exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic as DD nurses report staffing challenges related to staff exposure and quarantine, as well as fears of contracting the virus. In the absence of adequate staffing, care staff are covering multiple residences and working for multiple agencies, increasing the risk of “cross-contamination” and spread of COVID-19. DD nurses report that direct care staff have expressed concern over working during a pandemic as many direct care staff have health conditions that place them at high risk. The majority of the direct care workforce is female, of color, middle-aged or older, and reliant on some form of public assistance, with 1 in 5 lacking health insurance.33 , 34 This means that this “invisible COVID-19 workforce” is itself at higher risk for COVID-19 due to racial35 and socioeconomic health disparities.36

DD nurses participating in this survey recognize the need for the enactment of policies that identify DD care workers, including nurses and direct care staff, as front-line health providers. Nurses describe that PPE is diverted to other “health care workers, as if we do not provide health care as a basic service”. Testing has not been prioritized for individuals living and working in group homes, despite the increased risks of congregate living. Furthermore, hazard pay has not been extended to most DD care staff, heightening the short staffing situation experienced even prior to the pandemic. DD nurses also describe their frustration with the lack of policies and guidelines specific to the DD setting from public health and governmental bodies, and the lack of inclusion of DD nurses in ongoing COVID-19 administrative planning and policy decisions. This is despite the fact that DD nurses possess the education, experience, and skillset to not only participate in, but also lead interprofessional healthcare teams. As both healthcare and disability experts, DD nurses can provide leadership to tailor public health guidelines for use in specific DD settings. DD nurses can also educate non-health care staff with factual information on relative risks of COVID-19 and infection control practices, to help counteract widespread social media misinformation contributing to fear, stress, and anxiety.

In the face of COVID-19, the results of this study magnify the consistent issues relevant to the ongoing care and support needs of people with DD. The large sample size and lack of statistical differences between regional areas suggest that findings are generalizable nationwide. Furthermore, given this population of people who often live in congregate, community-based settings, they are particularly vulnerable and at high-risk for adverse outcomes within emergent and pandemic situations. Study limitations include a) self-selection of nurses belonging to a specialty nursing organization, and b) the cross-sectional design which captures nurses’ experiences at only one point during the ongoing pandemic. Findings reflect the challenges faced and anticipated by DD nurses early in the pandemic response which may bias findings toward magnifying challenges associated with pandemic planning over actual COVID-19 prevention and risk mitigation activities.

Implications for research

As health care for people with DD has shifted from an institutional model to care provided in a variety of home and community-based settings, the role of the DD nurse so, too, has diversified. A lack of clear understanding of the DD nursing role and agencies’ lingering concerns over medicalizing disability care20 were evident in nurses’ descriptions of challenges faced in meeting the care needs of people with DD during the COVID-19 pandemic. Future research needs to specifically address and incorporate the role of the DD nurse as a critical participant in the interprofessional team, which is especially important during a health care crisis. Additionally, although nursing is often associated with the medical model of disability20, DD nurses in this study most highly ranked social considerations to meeting the needs of people with DD, supporting a social model of health. Such a model provides a framework for research relevant to social determinants important to health and wellness in the daily lives of people with DD, as well as during a pandemic.

Implications for practice

Staff working in DD residential agencies provide 24/7 care to individuals at high-risk for complications from COVID-19. Ready availability of PPE must be prioritized for these settings. Likewise, testing needs to be prioritized for people with DD and their care staff. Public health guidelines specifically inclusive of DD residential and day habilitation settings are needed. Increased funding, including hazard pay for direct care staff, is needed to mitigate overwhelming staff shortages. DD nurses need to be involved in pandemic planning at every level to ensure basic care needs, including physical and mental health, social, and spiritual needs, are being adequately met to prevent and mitigate the spread of COVID-19 and adverse consequences associated with social distancing and isolation.

Conclusions

This is the first nationwide study on COVID-19 in the DD community. A startling finding is the lack of DD nursing involvement in planning and public policy development during this major public health crisis. Just as persons with DD are devalued in society, so too are DD nurses and direct care staff. Integral to quality of care and support and as primary liaisons to healthcare, DD nurses need to be included in the interprofessional planning associated with emergency planning and policy. Although public health nurses are involved in COVID-19 planning, they do not have the scope of knowledge, training, or experience with people with DD to understand the unique barriers faced by this population. Within their roles as educators and advocates for people with DD, DD nurses are well-poised to contribute to planning and public policy efforts along with self-advocates with DD.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Acknowledgments

Sincere appreciation is extended to the Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association for their support of and participation in this study. DDNA is a nursing specialty organization committed to advocacy, education, and empowerment for nurses who support persons with developmental disabilities (DD). DDNA aims to foster the growth of nursing knowledge and expertise so as to affect health and wellness for people with DD across multiple sectors of health care, education, and public policy. For more information: https://ddna.org/

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.101015.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.National Council on Disability The Current State of Health Care for People with Disabilities. https://www.ncd.gov/publications/2009/Sept302009 Published September 30, 2009.

- 2.Boyle C.A., Fox M.H., Havercamp S.M., Zubler J. The public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic for people with disabilities. Disability and Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2020.100943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.ACL Administration for Community Living History of the DD act. https://acl.gov/about-acl/history-dd-act

- 4.Steven D, Landes SD. Potential Impacts of COVID-19 on Individuals with Intellectual and Developmental Disability: A Call for Accurate Cause of Death Reporting. Lerner Center for Public Health Promotion Research Brief, 20. https://lernercenter.syr.edu/2020/04/14/potential-impacts-of-covid-19-on-individuals-with-intellectual-and-developmental-disability-a-call-for-accurate-cause-of-death-reporting/Published April 14, 2020. Retrieved on May 17, 2020.

- 5.Laughlin J., Whelan A., Purcell D. Philadelphia Inquirer; May 17, 2020. At South Jersey Center for Disabled Adults, COVID-19 Has Killed 8 while Infecting Most Residents and Many Staff.https://www.inquirer.com/health/coronavirus/developmental-disabilities-new-jersey-new-lisbon-covid-coronavirus-health-disabled-20200517.html [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turk M.A., Landes S.D., Formica M.K., Goss K.D. 2020 May 24. Intellectual and Developmental Disability and COVID-19 Case-Fatality Trends: TriNetX Analysis. Disability and Health. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krahn G.L., Fox M.H. Health disparities of adults with intellectual disabilities: what do we know? What do we do? J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2013;27(5):431–446. doi: 10.1111/jar.12067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scott H.M., Havercamp S.M. Race and health disparities in adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities living in the United States. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;52(6):409–418. doi: 10.1352/1934-9556-52.6.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradley V.J. Exploring health disparities among people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: What are the issues and do race and ethnicity play a role? Presentation of The National Association of State Directors of Developmental Disabilities Services annual meeting. November 13, 2014. http://www.nationalcoreindicators.org/upload/presentation/FINAL_NASDDDS_2014_Health_Disparities.pdf Alexandria, Virginia.

- 10.Fisher K., Hardie T.L., Ranjan S., Peterson J. Utilizing health records to characterize obesity, comorbidities, and health-care services in one human service agency in the United States. J Intellect Disabil. 2017;21(4):387–400. doi: 10.1177/1744629516660417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McQueenie R., Foster H.M.E., Jani B.D. Multimorbidity, polypharmacy, and COVID-19 infection within the UK Biobank cohort. PloS One. 2020 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0238091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friese T., Ailey S. Specific standards of care for adults with intellectual disabilities. Nurs Manag. 2015;22(1):32–37. doi: 10.7748/nm.22.1.32.e1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braddock D., Hemp R. 2008. Services and funding for people with developmental disabilities in Illinois: a multi-state comparative analysis.https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309493818_Services_and_Funding_for_People_With_Developmental_Disabilities_in_Illinois_A_Multi-State_Comparative_Analysis#fullTextFileContent Report prepared for the Illinois Council on Developmental Disabilities Chicago and Springfield. Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2016. Intermediate care facilities for individuals with intellectual disabilities (ICFs/IID)https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Provider-Enrollment-and-Certification/CertificationandComplianc/ICFIID Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeBlanc A.J., Tonner C., Harrington C. Medicaid 1915c home and community-based services waivers across the states. Health Care Financ Rev. 2000;22:159–174. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Research/HealthCareFinancingReview/Downloads/00Winterpg159.pdf Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services . 2019. Home and Community-Based Services.https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/American-Indian-Alaska-Native/AIAN/LTSS-TA-Center/info/hcbs Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braddock D., Hemp R., Rizzolo M.C., Haffer L., Tanis E.S., Wu J. American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities; Washington, DC: 2011. The State of the States in Developmental Disabilities, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ervin D.A., Hennen B., Merrick J., Morad M. Healthcare for persons with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the community. Frontiers in Public Health. 2014;2(83):1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2014.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association Why DDNA? 2019. https://ddna.org/membership/why-ddna/ Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from.

- 20.Auberry K. Intellectual and developmental disability nursing: current challenges in the USA. Nurs Res Rev. 2018;8:23–28. doi: 10.2147/nrr.s154511. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Developmental Disabilities Nurses Association (DDNA). Practice Standards of Developmental Disability Nursing (third ed.). Joliet, IL: High Tide Press. In press.

- 22.Mcleroy K.R., Bibeau D., Steckler A., Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15(4):351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Creswell J.W., Clark V.P. Sage.; Los Angeles: 2018. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Academy of Developmental Medicine and Dentistry FAQs. https://www.aadmd.org/faqs

- 25.IBM SPSS Statistics GradPack & Faculty Packs IBM SPSS statistics GradPack & faculty packs - overview - United States. https://www.ibm.com/us-en/marketplace/spss-statistics-gradpack

- 26.Bengtsson M. How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open. 2016;2:8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.npls.2016.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abrams A. ’We Are in Crisis.’ COVID-19 Exacerbates Problems for People with Disabilities. https://time.com/5826098/coronavirus-people-with-disabilities/ Time. Published April 24, 2020.

- 28.Serres C. Minnesota Seniors and People with Disabilities Still Battling Isolation, Despite Loosening of COVID-19 Restrictions. Star Tribune. https://www.startribune.com/minnesota-seniors-disabled-still-battling-isolation-despite-loosening-of-restrictions/570563012/. Published May 22, 2020. Accessed May 25, 2020.

- 29.Desroches M. Nurses’ attitudes, beliefs, and emotions toward caring for adults with intellectual disabilities: an integrative review. Nurs Forum. 2019;55:211–222. doi: 10.1111/nuf.12418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez R., Lord H., Halcomb E. Implications for COVID-19: a systematic review of nurses’ experiences of working in acute care hospital settings during a respiratory pandemic. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jnurstu.2020.103637. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilson N.J., Wiese M., Lewis P., Jaques H., O’Reilly K. Nurses working in intellectual disability-specific settings talk about the uniqueness of their role: a qualitative study. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75:812–822. doi: 10.1111/jan.13898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Future Health Care Workforce for Older Americans . National Academies Press; Washington (DC): 2008. Retooling for an Aging America: Building the Health Care Workforce. Chapter 5: The Direct-Care Workforce.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215393/ Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirschner K.L., Iezzoni L.I., Shah T. 2020. The Invisible COVID Workforce: Direct Care Workers for Those with Disabilities.https://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/invisible-covid-workforce-direct-care-workers-those-disabilities Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- 34.PHI . 2020. It’s Time to Care: A Detailed Profile of America’s Direct Care Workforce.https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Its-Time-to-Care-2020-PHI.pdf Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hooper M.W., Napoles A.M., Perez-Stable E.J. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323:2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher M., Bubola E. The New York Times; March 16 2020. As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens its Spread.https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/coronavirus-inequality.html Retrieved on September 1, 2020 from. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.