Abstract

Thiocarbamates are a major class of herbicides that were used extensively in the agricultural industry. Toxicological evaluation showed molinate caused reproductive impairment in male rats, whilst others produced behavioural effects at high doses. Rats dosed with molinate either as a single large oral dose of 100 mg/kg or as multiple doses of 50 mg/kg for 7 days produced inhibition of brain acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Molinate and other thiocarbamate herbicides undergo metabolism to form sulphoxides that can carbamoylate thiol’s such as glutathione and proteins. We have chemically synthesised the sulphoxide and sulphone metabolites of six thiocarbamate herbicides and examined their ability to inhibit rat brain and human red cell AChE in vitro. Parent thiocarbamates were inactive, whilst the sulphoxides produced inhibition with IC50’s in the 1–10 mM range, the sulphone metabolites were the most active with IC50’s for molinate, pebulate, EPTC and vernolate in the μM range. Inhibition was both time- and dose-dependent with biomolecular rate constants for the inhibition of the human red cell enzyme of 0.3 × 102 and 2.0 × 102 M−1 min−1 for molinate sulphoxide and sulphone, respectively. No recovery of enzyme activity, with either enzyme, was seen following dilution of the inhibitor to a concentration that does not inhibit the enzyme for up to 24 h at 25°C at pH 7.4. The metabolites of these thiocarbamate herbicides are rather poor inhibitors of AChE when compared to the organophosphorus ester, paraoxon or the monomethylcarbamate, eserine. Unlike eserine the inhibition produced by the thiocarbamates is irreversible.

Keywords: thiocarbamates herbicides, rat brain acetylcholinesterase, human red cell acetylcholinesterase

Introduction

Thiocarbamate herbicides (Fig. 1) have been widely used in agriculture over many years. Incorporated into soil prior to planting controls a great variety of broadleaf and grass weeds with little or no damage to several crops. Toxicological evaluation showed that molinate produced testicular toxicity in rats, whilst several of the other analogues caused signs of neurotoxicity. Despite their structural similarity to carbamates little information is available on their interaction with acetylcholinesterase (AChE). Thiocarbamates undergo rapid biodegradation such that persistent residues are not a problem. Thiocarbamates are rapidly metabolised by both plant and mammalian systems and a range of metabolites have been identified [1–5]. N-Dealkylation, ring hydroxylation and sulphoxidation are major pathways of metabolism in mammals or in liver microsomal mixed function oxidase systems [2, 5–7]. The sulphoxide metabolites formed are carbamoylating agents which will readily react with tissue thiol’s such as glutathione and cysteine (Fig. 2) and have been shown to be more potent than the parent thiocarbamate as herbicides [1–3, 6, 8]. The carbamoylation reaction is believed to be important in the metabolism and possible mode of action of these herbicides. The sulphoxide metabolites of a number of thiocarbamates have been detected, albeit transiently, in the liver of mice and rats and has been inferred by the appearance of their mercapturic acids in the urine of rats treated with parent compound compounds and their sulphoxides [3, 4, 6–8].

Figure 1.

Thiocarbamate herbicides. Chemical structure, IUPAC nomenclature and common names for the thiocarbamates used in this study.

Figure 2.

Metabolic pathway for the metabolism of molinate. This figure shows the routes of metabolism of molinate, in principle similar metabolism has been shown with the other five thiocarbamates used in this study. Namely C-oxidation, S-oxidation and formation of glutathione conjugates, see references in the text.

Studies have shown that the sulphoxide metabolite, but not parent compound, of a number of thiocarbamates are inhibitors of rat liver mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, analogous to that produced by disulfiram. The inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase by disulfiram is believed to be due to its metabolism to a sulphoxide [9, 10], which is a potent inhibitor of this enzyme. Further oxidation of the sulphoxide of disulfiram will afford the sulphone (S-methyl-N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphone), which has been reported to be a potent irreversible inhibitor of mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase [11]. Molinate has also been shown to inhibit the carboxylesterase hydrolase A, the protein being isolated from rat liver following dosing with 14C-labelled molinate [12]. Molinate is covalently bound to hydrolase A and in a series of elegant studies Zimmerman and coworkers [13] showed it carbamoylated cys-125 in rat haemoglobin forming a S-hexahydro-1H-azepine-1-carbonylcysteine adduct identified bound to β-2 and β-3 chains of globin. Daily dosing of rats with 100 mg/kg/day of molinate for 4 and 11 days showed the formation of adducts in globin were cumulative [13]. Subsequent studies examined the ability of vernolate, ethiolate, EPTC and butylate to form protein adducts with haemoglobin in vivo in rats. In addition, brain, liver and testes mitochondrial and microsomal fractions were incubated with these thiocarbamates and the activities of hydrolase A, low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase, total aldehyde dehydrogenase and the presence of S(N,N-dialkylaminocarbonyl) cysteine adducts examined. All thiocarbamates except butylate produced S(N,N-dialkylaminocarbonyl) cysteine adducts in vivo and inhibited enzyme activities in vitro [8].

The thiocarbamate molinate, when administered at high doses to rats, produces testicular injury that results in sperm abnormalities [14]. Metabolism of molinate by S-oxidation to the sulphoxide or sulphone has been shown to inhibit testicular carboxylesterase (hydrolase A) activity [12, 14]. Molinate also binds to rat red blood cells [13]. In view of the findings that molinate can undergo metabolism to a chemically reactive metabolite, which is a potent inhibitor of carboxylesterase. We examined the hypothesis that the sulphoxide or sulphone metabolites of molinate and other thiocarbamate’s may inhibit AChE, based on their structural similarity to carbamates, which are good inhibitors of this enzyme.

In this paper, we report (i) studies showing inhibition of rat brain AChE following administration of molinate. (ii) The ability in vitro of six thiocarbamate herbicides and their sulphoxides and sulphones to inhibit (carbamoylate) rat brain AChE and human red cell AChE. (iii) The rate of reactivation of these carbamoylated enzymes.

This work was undertaken in 1995/6 at Zeneca, Central Toxicology Laboratory, Alderley Park, Cheshire.

Materials and Methods

Treatment of animals

Sexually mature male Sprague–Dawley rats (10–12 weeks old) obtained from Charles River Breeding Laboratories (Kent, UK) were used for all the in vivo studies with molinate. The rats were housed in temperature controlled rooms (19–23°C) with constant humidity (40–70%) and a 12-hour light–dark cycle. Water and food (R & M No. 1 pelleted diet, Special Diet Services Ltd, Witham, UK) were provided ad libitum. All animals were acclimatised to their surroundings for at least 10 days before dosing. Rats, usually six per treatment group, were administered molinate orally in corn oil at 4 ml/kg body weight either as a single dose at 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg body weight or as given seven daily doses of 10, 50 or 100 mg/kg body weight. Control animals received corn oil alone orally at 4 ml/kg body weight. Animal care and monitoring were in accordance with strict guidelines issued by the British Home Office legislation. Animal procedures and treatment were performed according to approved animal licences and guidelines, and animals were terminated when deemed to be under moderate stress or discomfort.

For the in vitro studies male Alpk:APfSD (Wistar-derived) rats (8–12 weeks old) were used for tissue collection of whole brain. Animals were obtained from the colony at the Animal Breeding Unit, Alderley Park, Macclesfield (Cheshire, UK) and housed as described above.

Chemicals

Molinate, Vernolate, Pebulate, Butylate, EPTC and Cycloate (see Fig. 1 for chemical structures and nomenclature) with a minimum chemical purity of >96% were obtained from Zeneca Agrochemical Products (Richmond, CA, USA). The sulphoxide and sulphones of these chemicals were synthesised by sulphur-oxidation as described by [15]. The purity of the sulphoxides and sulphones was >98% as determined by thin layer chromatography and the structures were confirmed by 1H-NMR and chemical ionisation mass spectrometry. Solutions of the thiocarbamates or their sulphoxides or sulphones were prepared in dimethyl formamide at 2 M and subsequent dilutions made in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 to give stock solutions of either 2 or 20 mM. Lyophilised human red blood cell AChE at 0.5 U/mg protein, acetylthiocholine iodide, 4-nitrophenyacetate, eserine, phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (PMSF) and paraoxon were purchased from Sigma Chemical Company, Poole (Dorset, UK).

Acetylcholinesterase measurements

Rats were killed by an overdose of diethyl ether and then exsanguinated. Whole brain was removed, weighed and a 10% homogenate (w/v) prepared in ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8.0 using a Potter all glass pestle and tube. Analysis was either carried out immediately or aliquots of the homogenate were stored at −20°C.

AChE activity was measured in brain homogenates from molinate treated or control rats by the method of Ellman et al. [16]. Samples (0.1 ml) of rat brain homogenate (2% w/v diluted in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8.0) were added to a 1 cm3 cuvette containing 0.1 ml of (5,5′-dithio-bis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) DTNB (10 mM in phosphate buffer pH 8.0) and 2.8 ml of 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 8.0. The reaction was started by the addition of 0.02 ml acetylthiocholine (75 mM in water) and the formation of the product measured at 25°C with time at 412 nm in a spectrophotometer (Lambda 5 spectrophotometer, Perkin Elmer). The initial reaction was measured over the first 5 min in either duplicate or triplicate.

For the inhibition studies in vitro, varying concentrations of the potential inhibitor were pre-incubated with either rat brain homogenate (2% w/v final concentration in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4) 0.1 ml, or the red blood cell enzyme (stock solution 10 mg/ml in ice-cold 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4) 0.1 and 2.8 ml 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 for 10 min at 37°C. A sample was taken for the determination of enzyme activity as described above. All studies were conducted with at least six concentrations of inhibitor and repeated at least three times using a different tissue sample.

For the reactivation studies, the inhibitors were pre-incubated with the enzyme (10% rat brain homogenate or 5 mg red blood cell AChE) for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, except for molinate sulphoxide which was for 90 min to give 65–90% inhibition of the enzyme. The reaction mixture was diluted 100-fold in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4, to give a concentration that does not produce any inhibition, and incubated at 25°C. Samples (1 ml) were removed immediately after dilution and at subsequent time points for assay of enzyme activity as described above. Rat brain results are expressed as g wet weight of brain and red blood cell studies as per mg of protein. Protein was measured by the method of Lowry et al. [17]. The AChE measurements in rat brain were not corrected for butyrlcholinesterase.

Statistical analysis

For the in vivo studies comparisons between untreated and molinate-treated animals were analysed using Prism (GraphPad, San Diego, Ca) using analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni-corrected t-tests. The dose-response data in vitro was also fitted using Prism generating an IC50 from the average of three separate experiments.

Results

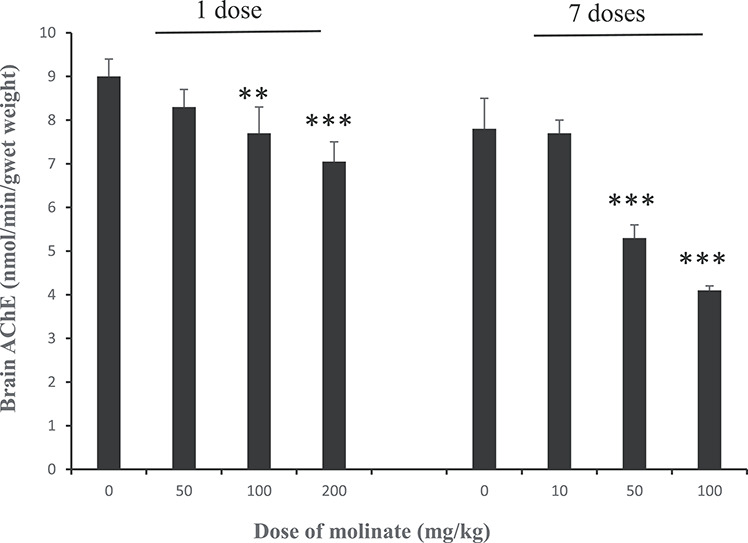

Inhibition of rat brain AChE following oral administration of molinate

Following a single oral dose of 200 mg/kg molinate, the activity of AChE in the brain was not affected 2 h after dosing, but was inhibited by about 20% at both 24 and 48 h after dosing (24 h: control, 8.72 ± 0.40; treated 7.23 ± 0.33 μmol/min/g wet weight of brain P < 0.001; 48 h: control, 8.44 ± 0.22; treated, 6.87 ± 0.57 μmol/min/g wet weight of brain P < 0.001 with five animals per group). Based on this time course study, another group of rats were given a single oral dose of molinate at 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg and killed 24 h after dosing and the brain AChE determined (Fig. 3). Inhibition was seen at 100 and 200 mg/kg. In a further study molinate was dosed orally on a daily basis for 7 days at 10, 50 or 100 mg/kg and the extent of inhibition of AChE determined in the brain (Fig. 3). A more marked inhibition was seen following multiple doses of either 50 or 100 mg/kg molinate than following a single dose, showing a cumulative inhibition. Whilst no effect on brain AChE was seen at 10 mg/kg molinate following seven daily doses (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

The activity of AChE in the brain of rats dosed with molinate. Groups of adult male rats were orally dosed with molinate either as a single dose of 50, 100 or 200 mg/kg and killed 24 h later, or as daily doses of 10, 50 or 100 mg/kg for 7 days and killed 24 h after the last dose. Acetylcholinesterase activity in the brain was determined as described in the Materials and Methods. Results are means ± SD with five animals per group. **Significantly different appropriate control, P < 0.01, ***significantly different appropriate control, P < 0.001.

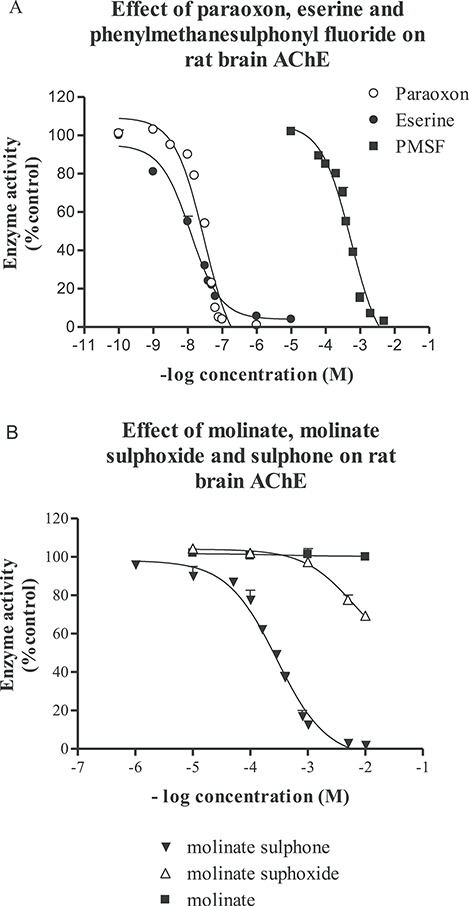

In vitro studies with rat brain AChE

AChE activity in rat brain was inhibited following 10 min incubation at 37°C with the monomethylcarbamate eserine, the organophosphorous ester paraoxon and PMSF, with IC50 values of 12, 25 nM and 408 μM (Fig. 4A). Similar studies with six thiocarbamates (butylate, cycloate, EPTC, molinate, pebulate and vernolate) showed that these chemicals at concentrations up to 10 mM had no effect on AChE activity (Table 1 and Fig. 4B for studies with molinate). However, the sulphoxide metabolites of these thiocarbamates did produce some dose-related inhibition of AChE activity (Table 1 and Fig. 4B). Inhibition was only seen at doses in the 1–10 mM range following 10 min pre-incubation with the enzyme. In contrast, the sulphone metabolites of these thiocarbamates were considerably better inhibitors of AChE with IC50 values in the μM range for molinate, pebulate, EPTC and vernolate, and in the mM range for cycloate and butylate (Table 1 and Fig. 4B for studies with molinate sulphone). Inhibition of rat brain AChE by the sulphoxide and sulphone metabolites is both time and concentration dependent. Time course studies with molinate sulphoxide and molinate sulphone (Fig. 5A) showed that the inhibition was first order and bimolecular with derived rate constants of 11.0 × 102 and 8.5 × 102 M−1 min−1 for the sulphoxide and sulphone, respectively.

Figure 4.

The effect of paraoxon, eserine, phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride, molinate, molinate sulphoxide and molinate sulphone on the activity of rat brain AChE. Various concentrations of paraoxon, eserine or phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride (A) or molinate, molinate sulphoxide or molinate sulphone (B) were incubated with rat brain homogenate for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. The substrate was then added and the activity of AChE determined as described in the Materials and Methods. Results are means ± SE with at least three separate brain samples, control activity was 10.04 ± 0.80 (12) μmol/min/g wet weight of brain.

Table 1.

The concentration of six thiocarbamates and other AChE inhibitors giving 50% inhibition of rat brain AChE

| Inhibitor | Parent compound | Sulphoxide | Sulphone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molinate | >10 mM | >10 mM (33%) | 0.28 mM |

| Butylate | >10 mM | >10 mM (10%) | 10 mM |

| Cycloate | >10 mM | >10 mM (23%) | 1.38 mM |

| Pebulate | >10 mM | ND | 0.1 mM |

| Vernolate | >10 mM | >10 mM (34%) | 0.09 mM |

| EPTC | >10 mM (27%) | >10 mM (24%) | 0.57 mM |

| Paraoxon | 25 nM | ||

| Eserine | 12 nM | ||

| PMSF | 408 μM |

Rat brain homogenate (0.1 ml of 2% homogenate) was pre-incubated with a range of concentrations of the inhibitors for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and then acetylthiocholine added and the enzyme activity determined. Results show the IC50’s derived by curve fitting the data from at least three separate experiments as described in the Materials and Methods. The values in brackets show the extent of inhibition seen at 10 mM as a percentage of control. AChE control activity was 10.04 ± 0.80 (12) μmol/min/g wet weight of brain. ND: not determined.

Figure 5.

The time and concentration dependent inhibition of rat brain AChE by molinate sulphone and its reactivation following exposure to molinate sulphoxide, molinate sulphone, vernolate sulphone, paraoxon or eserine. The rate of inhibition was measured at the times and concentrations of molinate sulphone (A) as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Molinate sulphone 0.75 mM (Δ), vernolate sulphone 2 mM. (♦) paraoxon 0.15μM (⋅) or eserine 0.1 μM (●) were pre-incubated with rat brain homogenate for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. While molinate sulphoxide 10 mM (▼) it was pre-incubated with rat brain homogenate for 60 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Following pre-incubation, samples were diluted 100-fold in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 at 25°C and aliquots taken for analysis of enzyme activity at various times after dilution. Control enzyme activity was 10.04 ± 0.80 (12) μmol/min/g wet weight of brain.

Rat brain AChE activity inhibited by molinate sulphoxide, molinate sulphone or vernolate sulphoxide was not reactivated following dilution to a concentration that produces no inhibition, when examined over 24 h (Fig. 5B). Paraoxon showed similar results, while with eserine there was reactivation with a half-life of 60 min (Fig. 5B).

In vitro studies with purified human red blood cell AChE

Similar studies to those described above were conducted with purified human red blood cell AChE. Eserine and paraoxon were potent inhibitors with IC50 values of 20 and 24 nM, respectively (Fig. 6). Studies with the six thiocarbamates showed that these chemicals at concentrations up to 10 mM had no effect on AChE activity (see Fig. 6 for the studies with molinate). We only examined one sulphoxide metabolite, that from molinate, which produced a dose-related inhibition of AChE activity (Fig. 6 and Table 2) with an IC50 value of 4.3 mM. In contrast, the sulphone metabolites of these thiocarbamates were considerable better inhibitors of AChE with IC50 values in the μM range for all except butylate (Fig. 6 for molinate sulphone and Table 2). Time course studies with molinate sulphoxide and molinate sulphone (Fig. 7A) showed that the inhibition was first order and bimolecular with derived rate constants of 0.3 × 102 and 2.0 × 102 M−1 min−1 for the sulphoxide and sulphone, respectively.

Figure 6.

The effect of paraoxon, eserine, molinate, molinate sulphoxide or molinate sulphone on the activity of human red cell AChE. Various concentrations of paraoxon, eserine, molinate, molinate sulphoxide or molinate sulphone were incubated with rat brain homogenate for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. The substrate was then added and the activity of AChE determined as described in the Materials and Methods. Results are means ± SE with at least three separate brain samples, control activity was 950 ± 68 (n = 3) nmol/min/mg protein.

Table 2.

The concentration of six thiocarbamates and other AChE inhibitors giving 50% inhibition of human red cell AChE

| Inhibitor | Parent compound | Sulphoxide | Sulphone |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molinate | >10 mM | 4.3 mM | 0.16 mM |

| Butylate | >10 mM | ND | 1.0 mM |

| Cycloate | >10 mM | ND | 0.14 mM |

| Pebulate | >10 mM | ND | 0.01 mM |

| Vernolate | >10 mM | ND | 0.02 mM |

| EPTC | >10 mM (39%) | ND | 0.11 mM |

| Paraoxon | 24 nM | ||

| Eserine | 20 nM |

Human red cell AChE was pre-incubated with a range of concentrations of the inhibitors for 10 min in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 at 37°C and then acetylthiocholine added and the enzyme activity determined. Results show the IC50’s derived by curve fitting the data from at least three separate experiments as described in the Materials and Methods. The value in brackets shows the extent of inhibition seen at 10 mM EPTC as a percentage of control. AChE control activity was 950 ± 68 (3) nmol/min/mg protein. ND: not determined.

Figure 7.

The time and concentration dependent inhibition of human red cell AChE by molinate sulphone and its reactivation following exposure to molinate sulphoxide, molinate sulphone or eserine. The rate of inhibition was measured at the times and concentrations of molinate sulphone (A) as described in the Materials and Methods. (B) Molinate sulphone 0.75 mM (Δ) or eserine 0.1 μM (●) were pre-incubated with human red cell AChE for 10 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. While molinate sulphoxide 10 mM (▼) it was pre-incubated with human red cell AChE for 60 min at 37°C in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4. Following pre-incubation, samples were diluted 100-fold in 0.1 M phosphate buffer pH 7.4 at 25°C and aliquots taken for analysis of enzyme activity at various times after dilution. Control enzyme activity was 950 ± 68 (n = 3) nmol/min/mg protein.

Human red cell AChE activity inhibited by molinate sulphone or vernolate sulphoxide was not reactivated following dilution to a concentration that produces no inhibition when examined over 24 h (Fig. 7B), whereas with the eserine-inhibited enzyme the half-life of recovery of enzyme activity was 41 min (Fig. 7B).

Discussion

We report that a single large oral dose of the thiocarbamate herbicide molinate or multiple lower daily doses will inhibit rat brain AChE activity within 24 h of administration. The extent of inhibition is however rather modest, the maximum reduction seen being 50% following seven daily doses of 100 mg/kg. It is well established that molinate and other related thiocarbamate herbicides undergo biotransformation in mammals via microsomal NADPH-mediated sulphoxidation to generate sulphoxide metabolites which readily carbamoylate glutathione. The glutathione conjugates are then processed to cysteine conjugates and excreted in urine as the mercapturic acids (Fig. 2) [3, 4, 6–8]. Early studies suggested that sulphoxidation of the thiocarbamates appeared to be a detoxification pathway [2]; however, studies have shown that the sulphoxide metabolites of a range of thiocarbamates can inhibit (carbamoylate) hepatic low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase both in vitro and in vivo [9, 10]. Administration of the parent thiocarbamates molinate, vernolate, pebulate and EPTC, and to a lesser extent butylate to rats or mice also produces inhibition of hepatic low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase, while cycloate was inactive [8–10]. In this regard, the thiocarbamates and their sulphoxide metabolites resemble disulphiram and this is supported by the findings that molinate-treated rats challenged with ethanol, exhibit a hypotensive response indicative of a disulphiram-like ethanol reaction [10]. Disulphiram in both rats and humans undergoes metabolism by reduction, followed by methylation and it is the methylated metabolite which is then oxidised to form S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphoxide, which is responsible for the inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase [10, 18]. The sulphoxide metabolite of disulphiram can however undergo further oxidation to form the sulphone and studies have shown that the sulphone is a potent irreversible inhibitor of hepatic low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase [11]. Formation of the sulphoxide metabolite of many thiocarbamate herbicides has been shown in vitro using hepatic microsomal systems in the presence of NADPH [2, 5, 6]. These metabolites have also been detected with some thiocarbamates in vivo in the liver of mice at early times after dosing. However, sulphone metabolites have not been detected either in vitro or in vivo, but as these metabolites are chemically reactive and rapidly metabolised one cannot conclude that they are not formed [2, 4, 5, 15]. The sulphone metabolites of EPTC and butylate have been synthesised and administered to mice where they were shown to be considerably more toxic than either the parent compound or the sulphoxide metabolite [5], thus metabolism via this pathway can lead to increased toxicity.

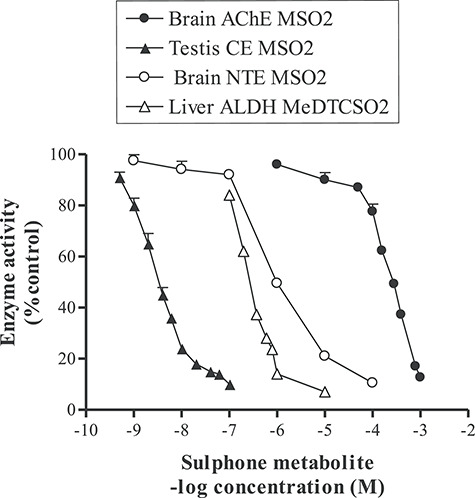

We have shown in vitro that the sulphone and sulphoxide metabolites of six thiocarbamate herbicides are inhibitors of rat brain and human red cell AChE, while the parent compounds are inactive. This inhibition is time- and dose-dependent and is presumably due to the carbamoylation of the serine residue in the active site of AChE analogous to that produced by organophosphorus and carbamate esters [19]. The sulphone metabolites are relatively weak inhibitors of AChE, the most potent compounds such as vernolate and pebulate sulphone having IC50 values of 10–20 μM compared to paraoxon and eserine, which have IC50 values of around 20 nM against human red cell AChE when measured under identical conditions (Table 2). Similarly, the bimolecular rate constant for inhibition of human AChE by molinate sulphone at 2.0 × 102 M−1 min−1 compared to 3.3 × 106 M−1 min−1 for eserine [20], shows an approximately 10 000-fold difference. The sulphone of butylate and the sulphoxide metabolites of the thiocarbamates studied were considerably less active than the sulphones at inhibiting either rat brain or human red cell AChE. The IC50 values for the human enzyme are lower, more active, than those found for the rat brain enzyme (compare Tables 1 and 2). This is presumably due to using the purified human enzyme versus a whole brain homogenate where there are many binding sites on proteins and glutathione [8] that can undergo carbamoylation and hence reduce the available chemical for inhibition of AChE. Inhibited rat brain or human red cell AChE does not undergo reactivation following dilution, when studied for up to 24 h at pH 7.4 and 25°C, showing that di-N-propyl or homopiperidyl carbamoylation of AChE, unlike monomethyl or dimethyl carbamoylation, is not readily reversible [20]. In this regard, this type of inhibition more closely resembles that seen with paraoxon. The finding that AChE activity was not readily reactivated is in agreement with the studies of Davies et al. [21], who found flyhead AChE inhibited by esters of polymethylene dicarbamic acids resulted in no recovery of enzyme activity over 20 h at pH 7.4 and 25°C. These in vitro studies suggest that following molinate administration to rats, metabolism leads to the generation of the sulphoxide and possibly the sulphone metabolites which are capable of carbamoylation AChE and neuropathy target esterase (NTE) in the brain, as reported in earlier studies [22] (Fig. 8) Whether this metabolism occurs in the brain, which is known to contain cytochromes P450 [23], or the metabolite is formed in the liver before entering the brain is not known. However, as the metabolites are chemically reactive and likely to be scavenged by glutathione and react with proteins such as haemoglobin where molinate forms a S-hexahydro-1H-azepine-1-carbonyl cysteine adduct with globin [13] or esterases [8] and aldehyde dehydrogenase in the liver [18], it seems likely that local metabolism in the target tissues may occur. An area that requires further study is the molecular interaction of thiocarbamates with AChE. It is well established that organophosphorous compounds and carbamates interact with the hydroxyl group of serine residue in the active site of the enzyme, giving a phosphorylated and carbamoylated enzyme, respectively [19]. The 3-dimensional structure of AChE is known and quantitative structure-activity relationship studies have classified and predicted the potency of AChE inhibitors and it is clear that inhibitors can interact with several sites on the enzyme [24]. Lee and Barron [24] examined seven thiocarbamates in their computer model showing that four, molinate, pebulate, EPTC and cycloate could act as inhibitors of AChE although there were relatively weak, which is consistent with our findings Table 2. In contrast, the studies by Zimmerman and coworkers [8, 13] using LC/MS/MS identified carbamoylation of Cys-125 residues of the β2- and β3- chains of rat globin and of proteins in rat liver after molinate administration. This difference may be due to the location in the cell of activation by cytochromes P-450 and the presence of GSH and proteins nearby to scavenge the reactive metabolite.

Figure 8.

Comparison of inhibition by molinate sulphone for three different esterases and for the active metabolite of disulphiram, S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphone on low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. The IC50 for the inhibition (carbamoylation) in vitro of rat brain AChE was 0.28 mM after 10 min at 37°C at pH 7.4 (Fig. 4B), for rat brain neuropathy target esterase 1 μM after 20 min at 37°C at pH 8.0 [22], for rat testicular microsomal carboxylesterase-hydrolase A 4 nM after 5 min at 25°C at pH 7.4 [Lock unpublished observation] and inhibition of hepatic low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase by S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphone 0.42 μM after 30 min at room temperature at pH 8.8 [11].

Molinate irreversibly inhibited rat and hen brain and peripheral nerve NTE activity by about 80% at 100–180 mg/kg, in both species 24 h after dosing [22], with no clinical or morphological signs of neuropathy in these animals. No morphological effects of molinate were seen in rat peripheral nerves given 93 mg/kg/day via subcutaneous mini pump over 59 days [8]. In vitro studies looking at NTE activity with molinate sulphoxide and sulphone in rat, hen and human brain tissue, found IC50 values of 4–8 μM for the sulphoxide and 1–2 μM for the sulphone with similar sensitivity across the species [22]. A phenyl valerate esterase activity similar to NTE, named M200, is also inhibited in these neural tissues, and inhibition of M200 has been associated with promotion [25]. Certain esterase inhibitors such as carbamates and sulphonyl halides can protect against organophosphate-induced delayed polyneuropathy(OPIDN) [26]. However, when the same inhibitors are given after a neuropathic organophosphorus ester, they cause exacerbation of OPIDN [27, 28]. Molinate was shown to partially protect against di-n-butyl-dichlorovinylphosphate (DBDCVP) neuropathy in hens when give 24 h before and exacerbated neuropathy when give 24 h after DBDCVP [22].

Cycloate sulphone is a poor inhibitor of AChE with IC50 value of 1.38 mM for rat brain and 0.14 mM for the human red blood cell enzyme, but is quite potent against testicular microsomal carboxylesterase-hydrolase A with an IC50 of 12 nM (Lock, unpublished data). The relevance of this to the neurotoxicity of cycloate in rats is unclear, where a high dose caused selective neuronal cell death in two regions of the forebrain, pyramidal neurons of layers II and III throughout the pyriform cortex and in granule cells of the caudal ventrolateral dentate gyrus [29].

It is interesting that molinate causes testicular toxicity in rats through inhibition of Leydig cell carboxylesterase-hydrolase A, using 4-nitrophenyl acetate as substrate [7, 8, 12, 14]. This is a key enzyme in the synthesis of testosterone and is very sensitive to inhibition by phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride IC50 67 nM [30] and molinate sulphone IC50 3 nM (Fig. 8). Tri-ortho-cresyl phosphate (TOCP) is also a known testicular toxicant in rats [31] and this effect is probably mediated by inhibition of testicular carboxylesterase-hydrolase A [32, 33]. Moreover, testicular carboxylesterase hydrolase A [12, 14], NTE [22] and rat brain and human red cell AChE (Figs 4B, 6 and 8) are inhibited in vitro by molinate sulphone. The hepatic low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase activity is sensitive to inhibition my thiocarbamates [9, 10] and to the active metabolite of disulphiram S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphone (Fig. 8) [11]. Thus, toxicity following exposure to anti-cholinergic chemicals can manifest itself in a number or organs following inhibition of esterase enzymes.

Conclusions

We report that sulphoxidation of the thiocarbamate herbicide molinate causes carbamoylation of AChE in rat brain following oral dosing. Studies in vitro with rat brain homogenate and purified human red blood AChE with six thiocarbamates and their sulphoxide and sulphone metabolites, showed inhibition (carbamoylation) in the mM range for the sulphoxides but in the μM range with the sulphones. This inhibition was irreversible and resembles that seen with organophosphorus esters, but not the carbamate ester eserine. Microsomal oxidation of thiocarbamates to their sulphoxide metabolites followed by conjugation with glutathione, represents about 30–40% in rats and mice [2, 4, 5]. While in humans sulphoxide formation with molinate is only 1% [34] high exposures to these thiocarbamates herbicides should be envisaged for such effects to occur in humans.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Richard B. Moore for the synthesis of the thiocarbamates sulphoxides and sulphones and Alison G. Richardson for excellent technical assistance.

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Dr Martin K. Ellis, a former colleague who worked on the thiocarbamates. He was sadly killed while riding his bicycle on 9 April 2020.

Conflict of Interest statement

The author was employed by Zeneca Central Toxicology Laboratory the research being supported by Zeneca Agrochemicals.

References

- 1. Casida JE, Gray RE, Tilles H. Thiocarbamate sulphoxides: potent, selective and biodegradable herbicides. Science 1974;184:573–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Casida JE, Kimmel EC, Ohkawa H et al. Sulphoxidation of thiocarbamate herbicides and metabolism of thiocarbamate sulphoxides in living mice and liver enzyme systems. Pestic Biochem Physiol 1975a;5:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Lay MM, Casida JE. Dichloroacetamide antidotes enhances thiocarbamate sulphoxide detoxification by elevating corn root glutathione content and glutathione S-transferase activity. Pestic Biochem Physiol 1976;6:442–56. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hubbell JP, Casida JE. Metabolic fate of the N,N-dialkylcarbamoyl moiety of thiocarbamate herbicides in rats and corn. J Agric Food Chem 1977;25:404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chen YS, Casida JE. Thiocarbamate herbicide metabolism: microsomal oxygenase metabolism of EPTC involving mono-and deoxygenation at sulphur and hydroxylation at each alkyl carbon. J Agric Food Chem 1978;26:263–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jewell WT, Miller MG. Comparison of human and rat metabolism of molinate in liver microsomes and slices. Drug Metab Dispos 1999;27:842–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jewell WT, Hess RA, Miller MG. Testicular toxicity of molinate in the rat: metabolic activation via sulphoxidation. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998;149:159–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zimmerman LJ, Valentine WM. Characterisation of S-(N,N-dialkylaminocarbonyl) cysteine adducts and enzyme inhibition produced by thiocarbamate herbicides in the rat. Chem Res Toxicol 2004;17:258–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Quistad GB, Sparks SE, Casida JE. Aldehyde dehydrogenase of mice is inhibited by thiocarbamate herbicides. Life Sci 1994;55:1537–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hart BW, Faiman MD. Inhibition of rat liver low Km aldehyde dehydrogenase by thiocarbamate herbicides. Biochem Pharmacol 1995;49:157–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mays DC, Nelson AN, Fauq AH et al. S-Methyl N,N-diethyldithiocarbamate sulphone, a potential metabolite of disulfiram and potent inhibitor of low Km mitochondrial aldehyde dehydrogenase. Biochem Pharmacol 1995;49:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jewell WT, Miller MG. Identification of a carboxylesterase as the major protein bound to molinate. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998;149:226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zimmerman LJ, Valentine HS, Armarnath K et al. Identification of a S-hexahyro-1H-azepine-1-carbonyl adduct produced by molinate on rat haemoglobin β2 and β3 chains in vivo. Chem Res Toxicol 2002;15:209–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ellis MK, Richardson AG, Foster JR et al. The reproductive toxicity of molinate and metabolites to the male rat: effect on testosterone and sperm morphology. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1998;151:22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Casida JE, Kimmel EC, Lay M et al. Thicarbamate sulphoxide herbicides. Environ Qual Saf Suppl 1975b;3:675–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ellman GL, Courtney KD, Andres V et al. A new and rapid colorimetric determination of acetylcholinesterase activity. Biochem Pharmacol 1961;7:88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL et al. Protein measurements with Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 1951;193:265–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hart BW, Faiman MD. In vitro and in vivo inhibition of rat liver aldehyde dehydrogenase by S-methyl N,N-diethylthiocarbamate sulphoxide, a new metabolite of disulfiram. Biochem Pharmacol 1992;43:403–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Aldridge WN, Reiner E (eds). Enzyme Inhibitors as Substrates: Interactions of Esterase’s with Esters of Organophosphorous and Carbamic Acids. North-Holland: Amsterdam, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Main AR, Hastings FL. Carbamylation and binding constants for inhibition of acetylcholinesterase by physostigmine (eserine). Science 1966;154:400–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Davies JH, Campbell WR, Kearns CW. Inhibition of fly head acetylcholinesterase by bis-[(m-hydroxyphenyl)-trimethylammonium iodide] esters of polymethylene dicarbamic acids. Biochem J 1970;177:221–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Moretto A, Giulio G, Panfilo S et al. Effects of S-ethylhexahydro-1H-azepine-1-carbothioate (molinate) on di-n-butyl-dichorovinyl phosphate (DBDCVP) neuropathy. Toxicol Sci 2001;62:274–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ferguson CS, Tyndale RF. Cytochromes P450 enzymes in the brain: emerging evidence of biological significance. Trend Pharmacol Sci 2011;32:708–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee S, Barron MG. A mechanism-based £D-QSAR approach for classification and prediction of acetylcholinesterase inhibitory potency and carbamate analogs. J Comput Aid Mol Design 2016;30:347–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lotti M, Moretto A. Promotion of organophosphate induced delayed polyneuropathy by certain esterase inhibitors. Chem Biol Interact 1999;119-120:519–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson MK. Organophosphate and delayed neuropathy-is NTE alive and well? Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1990;102:385–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lotti M, Caroldi S, Capodicasa E et al. Promotion of organophosphate induced delayed polyneuropathy by phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1991;108:234–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pope NC, Padilla S. Potentiation of organophosphate-induced delayed neurotoxicity by phenylmethanesulphonyl fluoride. J Toxicol Environ Health 1990;31:261–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Simpson MG, Horner SA, Mistry P et al. Neuropathological studies on cyclo ate-induced neuronal cell death in the rat brain. Neurotoxicology 2005;26:125–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Morgan EW, Yan B, Greenway D et al. Purification and characterisation of two rat liver microsomal carboxylesterases (hydrolase A and B). Arch Biochem Biophys 1994;315:495–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Somkuti SG, Lapadula DM, Chapin RE et al. Reproductive tract lesions resulting from subchronic administration (63 days) of tri-o-cresyl phosphate in male rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1987a;89:49–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chapin RE, Phelps JL, Burka LT et al. The effect of tri-o-cresyl phosphate and metabolites on rat Sertoli cell function in primary culture. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1991;108:194–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Somkuti SG, Lapadula DM, Chapin RE et al. Time course of the tri-ocresyl phosphate-induced testicular lesion in F344 rats: enzymatic, hormonal and sperm parameter studies. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 1987b;89:64–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wickramaratne GA, Foster JR, Ellis MK et al. Molinate: rodent reproductive toxicity and its relevance to humans—a review. Regul Toxicol Pharmacol 1998;27:112–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]