Abstract

Objective:

To determine if the Mechanism of Injury Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme (FTDS) are accurate for identifying children who need the resources of a trauma center.

Methods:

EMS providers transporting any injured child ≤15 years, regardless of severity, to a pediatric trauma center in 3 midsized communities over 3 years were interviewed. Data collected through the interview included EMS observed physiologic condition, suspected anatomic injuries, and mechanism. Patients were then followed to determine if they needed the resources of a trauma center by reviewing their medical record after hospital discharge. Patients were considered to need a trauma center if they received an intervention included in a previously published consensus definition. Data were analyzed with descriptive statistics including positive likelihood ratios (+LR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI).

Results:

9,483 provider interviews were conducted and linked to hospital outcome data. Of those, 230 (2.4%) met the consensus definition for needing a trauma center. 1,572 enrolled patients were excluded from further analysis because they met the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the FTDS. Of the remaining 7,911 cases, 62 met the consensus definition for needing a trauma center (TC). Taken as a whole, the Mechanism of Injury Criteria of the FTDS identified 14 of the remaining 62 children who needed the resources of a trauma center for a 77% under-triage rate. The mechanisms sustained were 36% fall (16 needed TC), 28% motor vehicle crash (MVC) (20 needed TC), 7% struck by a vehicle (10 needed TC), <1% motorcycle crash (none needed TC), and 29% had a mechanism not included in the FTDS (16 needed TC). Of those who sustained a mechanisms not listed in the FTDS, the most common mechanisms were sport related injuries not including falls (24% of 2,283 cases with a mechanism not included) and assault (13%). Among those who fell from a height greater than 10 feet, 4 needed a TC (+LR 5.9; 95%CI 2.8–12.6). Among those in a MVC, 41 were reported to have been ejected and none needed a TC, while 31 had reported meeting the intrusion criteria and 0 needed a TC. There were 32 reported as having a death in the same vehicle, and 2 needed a TC (+LR 7.42; 95%CI: 1.90–29.0).

Conclusion:

Over a quarter of the children who needed the resources of a trauma center were not identified using the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme. The Mechanism of Injury Criteria did not apply to over a quarter of the mechanisms experienced by children transported by EMS for injury. Use of the Mechanism Criteria did not greatly enhance identification of children who need a trauma center. More work is needed to improve the tool used to assist EMS providers in the identification of children who need the resources of a trauma center.

Introduction

Destination decision-making is a key EMS function, particularly in the case of trauma where it has long been recognized that severely injured patients need the resources of a trauma center.1 In many communities, potential for severe trauma based on the mechanism of injury is one of the indicators that allows EMS providers to select the destination hospital that has the best resources to treat the patient. Therefore, EMS providers must recognize those patients who are most likely to have severe injuries. The most commonly used tool to assist with this process is the Field Triage Decision Scheme developed by the American College of Surgeons and updated in collaboration with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.2

The Field Triage Decision Scheme is intended for use with both adult and pediatric patients. This Scheme is made up of four steps; 1) physiologic criteria, 2) anatomic criteria, 3) mechanism of injury criteria, and 4) special patient or system considerations.2 However, when triaging children, the Field Triage Decision Scheme has been found to have a high rate of under-triage which could result in severely injured patients not being identified in the field as needing transport to a trauma center.3–6 The recommended under-triage rate is typically 5%, but applying the guidelines to pediatric patients has been shown to under-triage as many as 35% of children.3

The Mechanism of Injury Criteria are a frequently debated component of the Field Triage Decision Scheme. Some feel the criteria over-triage too many patients while others feel they are essential to reducing under-triage, with very few studies evaluating the criteria in children.7–10 Further, to our knowledge there has not been an extensive evaluation of the utility of the Mechanism of Injury Criteria for children after removing patients who meet the first two steps of the Field Triage Decision Scheme (i.e., Physiologic and Anatomic Criteria). A prior adult study found that when those who met the Physiologic and Anatomic Criteria were removed, the Mechanism of Injury Criteria significantly increased over-triage, and identified less than half of the remaining patients who needed the resources of a trauma center.11 The objective of this study was to determine if the Mechanism of Injury Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme are accurate for identifying children who need the resources of a pediatric trauma center.

Methods

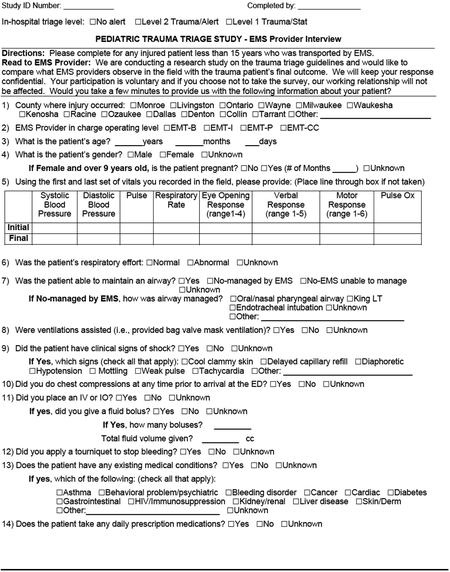

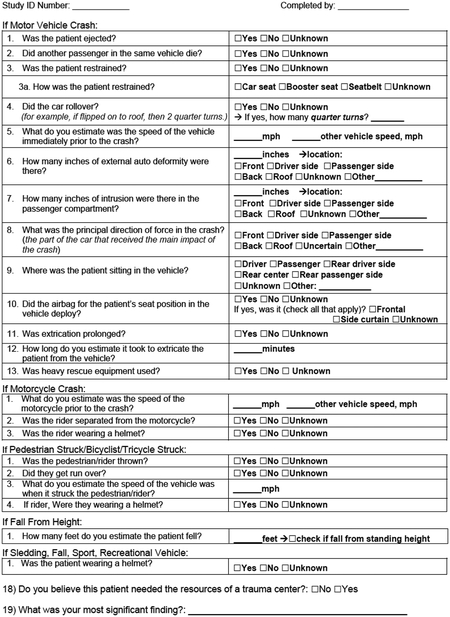

A3-year prospective observational study was conducted at three pediatric regional trauma centers in Dallas, TX; Milwaukee, WI; and Rochester, NY. Each center was designated as a pediatric trauma center in their region. In Milwaukee and Rochester the study was conducted at the only pediatric focused hospital in their community. EMS protocols in each of these communities directed providers to transport pediatric patients whom they suspected to have severe injuries to these facilities but the facilities also received a large percentage of the EMS transported pediatric patients in general. EMS protocols instructed providers to use the 2011 Field Triage Decision Scheme to identify patients with potentially severe trauma at the New York and Texas sites. The Wisconsin site generally followed the Scheme with a few added criteria. The Institutional Review Board at each of the participating hospitals reviewed and approved this study with a waiver of informed consent.

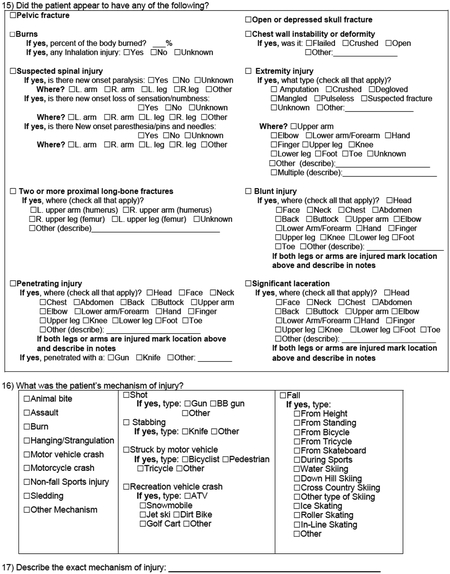

The study included any injured child 15 years old or younger who was transported to one of the participating emergency departments (ED) by EMS, regardless of injury severity or whether the hospital activated a trauma team. When the patients arrived in the ED a trained interviewer approached the EMS providers in charge of patient care and asked if they would complete a survey that included each component of the Field Triage Decision Scheme. The survey was accessed and recorded electronically using REDCap and included the EMS providers’ impressions of the patient’s physiologic condition, anatomic injuries, and mechanism of injury (Appendix 1). Providers’ impressions were recorded exactly and were not corrected if during the course of the patients ED or hospital care a finding was found to be incorrect. For example, if the provider reported the patient had two or more long bone fractures but the x-rays in the ED were negative, the EMS provider impression was left in place and the patient was considered to have met the Anatomic Criteria. This ensured that we were analyzing the information that the EMS provider would have used to make a destination decision. The only exception to this was in categorizing the mechanism of injury. Our data dictionary explicitly defined mechanism of injury and the research assistant used both the EMS providers’ interpretation and their answer to an open-ended question where the EMS providers described the mechanism of injury in their own words to ensure that the mechanisms were categorized correctly.

If the providers participated in the interview, the patients were followed to hospital discharge to determine if the resources of a trauma center were used. A previously published consensus-based criterion standard was used to determine trauma center need.12 However, the investigators for this study added thoracostomy within 2 hours of ED arrival to the outcome definition because it was felt that for children this was an indicator of needing a pediatric trauma center, and it was included in a similar criterion standard for pediatric trauma center activation.13 Medical record data were reviewed and abstracted and recorded in a case report form in REDCap by a single research coordinator at each site with direct oversight by a local physician. A written data dictionary was available at each site to assist with data abstraction and biweekly calls were held with all of the research coordinators and oversight physicians to ensure that data were abstracted in a similar manner at each site. The patient was considered to have needed the resources of a trauma center if they had any of the interventions or outcomes listed in Table 1.

Table 1:

Number of Subjects Who Did Not Meet the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the FTDC, But Met the Criterion Standard Used to Determine Trauma Center Need

| Consensus-Based Criterion Standard Definition | Number of Patients with Outcome (n=7,911) |

|---|---|

| Advanced airway management within 4 hours of arrival - excludes intubation solely for surgical purposes | 21 |

| More than 1 unit of a blood product within 4 hours of arrival - included any blood received from EMS and was based on orders regardless of supply or time to infuse | 11 |

| Admitted to the hospital for spinal cord injury - identified based on discharge codes and/or procedure notes. | 2 |

| Thoracotomy within 48 hours of arrival and did not meet NAEMSP/ACS-COT criteria for termination | 0 |

| Pericardiocentesis within 24 hours of arrival and did not meet NAEMSP/ACS-COT criteria for termination | 0 |

| Emergency cesarean delivery within 24 hours of arrival | 0 |

| Vascular, neurologic, abdominal, thoracic, pelvic, spine or limb-conserving surgery within 24 hours of arrival | 22 |

| Intra-cranial pressure monitoring within 48 hours of arrival | 1 |

| Interventional radiology within 4 hours of arrival | 1 |

| Died before discharge but arrived not in cardiac arrest | 0 |

| Thoracostomy within 2 hours of arrival - added by investigators, not in original criteria | 3 |

The EMS providers’ observations were used to determine if the patient met the Anatomic or Physiologic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme. Patients that met those steps of the decision scheme were excluded from further analysis. We determined if the patient met the mechanism of injury criteria based on the EMS reported findings, this ensured that we were studying the criteria and not the providers opinion of need or ability to use the Field Triage Decision Scheme. The remaining cases were analyzed using descriptive statistics including under-and over-triage rates, and positive Likelihood Ratios along with 95% confidence intervals. Although we primarily focused on under-triage rates, when examining positive likelihood ratios we defined a good predictor as one with a positive likelihood ratio of 5 or greater, a moderate predictor as between 5 and 2, and a poor predictor as less than 2.14 Under and over-triage was calculated as described in the 2009 MMWR on field triage (under-triage = false negatives divided by all patients who needed the resources of a trauma center; over-triage= false positives divided by all patients who did not need the resources of a trauma center).15 If one of the mechanism criteria was documented as unknown, we considered it to not have met the criteria in the analysis, since the EMS providers would not have been able to use that criterion in determining the most appropriate destination decision.

Results

We conducted EMS provider interviews and obtained outcome data for 9,483 children, 230 (2.4%) of which needed the resources of a trauma center. Of these children, 1,572 (16.6%) met either the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme and were excluded from further analysis (Figure 1). Of the remaining 7,911 (83.4%) cases that did not meet Physiologic or Anatomic criteria, 62 (0.78%) needed the resources of a trauma center. The most common hospital interventions that indicated the patient needed the resources of a trauma center were emergent surgery and advanced airway (Table 1). The characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 2.

Figure 1: Number of Patients Included in The Study and Their Outcome Status.

*The grey box indicates the 7,911 patients who did not meet the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme and were included in the study.

Table 2:

Demographics and Other Characteristics of Included Patients

| Characteristic | Number of cases n=7,911 (percent of cases) |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 4,499 (56.9%) |

| Female | 3,404 (43.0%) |

| Unknown | 8 (0.1%) |

| Age | Mean 7.99 years (SD 4.6) |

| <1 year | 528 (6.7%) |

| 1–5 years | 2,127 (26.9%) |

| 6–10 years | 2,409 (30.5%) |

| 11–15 years | 2,847 (36.0%) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 1,930 (24.4%) |

| Non-hispanic | 5,837 (73.8%) |

| Unknown | 144 (1.8%) |

| Race | |

| American Indian\Alaskan Native | 27 (0.3%) |

| Asian | 121 (1.5%) |

| Black/African American | 3,124 (39.5%) |

| Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander | 8 (0.1%) |

| White/Caucasian | 3,537 (44.7%) |

| Other | 886 (11.2%) |

| Unknown | 208 (2.6%) |

| Provider Level | |

| EMT-Basic | 2,516 (31.8%) |

| EMT-Immediate | 137 (1.7%) |

| EMT-Paramedic | 5,189 (65.6%) |

| EMT-Critical Care | 67 (0.8%) |

| Unknown | 2 (>0.1%) |

| Pregnant (n=3404 females) | |

| Yes | 5 (0.1%) |

| No | 1,202 (35.3%) |

| Unknown | 2,197 (64.5%) |

| EMS Provider Believed the Patient Needed the Resources of a Trauma Center | |

| Yes | 3,580 (45.3%) |

| No | 4,327 (54.7%) |

| Unknown | 4 (>0.01%) |

SD-Standard Deviation

Falls (36%) and motor vehicle crashes (28%) were the most common mechanisms of injury among children included in this study. However, over a quarter of our sample did not have a mechanism of injury that is listed in the Field Triage Decision Scheme and several of those children needed a trauma center (Table 3). Of the 29% of cases that did not have one of the mechanisms listed in the field triage guidelines, the most common were sport related injuries not including falls (24% of 2,283 cases with a mechanism of injury not included), assault (13%), animal bite (5%), burn (5%), and recreational vehicle (e.g., moped, ATV, snowmobile) related injury (4%). Nearly half (47%) of those who did not fit into one of the Mechanism of Injury in the criteria did not fit into the extended list of mechanisms that we developed for this study (Appendix 1, question 16).

Table 3:

Mechanisms of Injury Sustained by Included Subjects

| Number of cases (% of Sample, denominator=7,911) | Number that met the criteria for that mechanism (% with that mechanism that met the criteria) | Number that Needed a Trauma Center (% with that mechanism of injury that needed a trauma center) |

Over and Under-Triage Using the Criteria for Each Mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Fall (criteria: from height >10 feet) |

2,810 (36%) | 95 (3%) | 16 (1%) | 8% Over-triage 56% Under-triage +LR 5.9 (95%CI 2.8–12.6) |

|

Motor Vehicle Crash (criteria: ejection, Intrusion >12” at seat or >18” elsewhere, and Death of another passenger) |

2,246 (28%) | 100 (4%) | 20 (1%) | 4% Over-triage 90% Under-triage +LR 2.3 (95%CI 0.6–8.6) |

|

Auto vs. Pedestrian (Criteria: Significant Impact (>20 mph), Patient thrown, or run over) |

560 (7%) | 321 (57%) | 10 (2%) | 57% Over-triage 10% Under-triage +LR 1.6 (95%CI 1.3–2.0) |

|

Motor Cycle Crash (Criteria: >20 mph) |

12 (<1%) | 2 (17%) | 0 | N/A |

| Mechanism of injury that is not listed in the Field Triage Decision Scheme | 2,283 (29%) | N/A | 16 (1%) | N/A |

As listed in the Field Triage Decision Scheme, “fall” appears to be addressing falls that occur from a height. However, many of the children who fell were engaged in sports or other activities that made it difficult to evaluate the fall height (e.g., falling off a moving bicycle). Table 4 shows the different types of falls that children experienced. Ten of the 16 children who fell and needed the resources of a trauma center had fallen from a height. Four children who were reported as a fall from standing needed the resources of a trauma center. Further review of those cases identified that two received a serious laceration from glass that they were holding at the time of their fall, two fell from standing one onto a hard floor, and the other into a small ditch. The child who was designated as the fall type “other” and needed the resources of a trauma center was described as a child who was climbing on a tree branch and fell. It is unclear why the EMS providers did not feel that this was a fall from a height and the height was listed as unknown.

Table 4.

Mechanisms of Fall-Related Injuries Sustained by Included Subjects

| Number of cases (% of Sample n=2,810) | Number that Needed a Trauma Center (% with mechanism) | |

|---|---|---|

| From Height | 1,305(46%) | 10(1%) |

| From Standing | 957 (34%) | 4(<1%) |

| During Sport | 208 (7%) | 1(1%) |

| From Bicycle | 122(4%) | 0 |

| Skating | 47(2%) | 0 |

| From Skateboard | 30(1%) | 0 |

| Skiing | 18(1%) | 0 |

| From Tricycle | 3(<1%) | 0 |

| Other | 120(4%) | 1(1%) |

Taken as a whole the mechanism of injury criteria of the field triage decision scheme identified 14 of the 62 children who needed the resources of a trauma center. It also would have identified 485 children to transport to a trauma center who did not in fact need the resources of a trauma center, leading to an overall 6% over-triage rate and 77% under triage rate. The +LR, 3.7 95%CI 2.3–5.8 was considered moderate.

While Table 3, gives the under-and over-triage rates along with the positive likelihood ratios for each mechanism in the Field Triage Decision Scheme; table 5 illustrates the ability of the individual Mechanism of Injury Criteria to predict trauma center need. Very few children were in motorcycle crashes and none needed a trauma center so no further analysis on motorcycle crashes was performed. We evaluated falls from a height and falls from a height combined with falls from standing. In either case, we found that the 10 foot fall height cut point does not capture many of those who needed a trauma center. Patient height was not collected so average height for age was used to adjust the fall cut-point by patient height, and we found that more children were identified as meeting the criteria when age adjusted heights were considered, but the under-triage rate remained unchanged while the over-triage rate increased.

Table 5:

Mechanism of Injury Criteria’s Individual Prediction of Trauma Center Need

| Mechanism of Injury | Criteria | Trauma Center NOT Needed | NEEDED a Trauma Center | Over and Under-Triage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falls from a Height*** (n=1,219; 19 cases were missing age data) | >10 feet from height | 91 | 4 | 8% Over-triage 56% Under-triage +LR 5.9 (95%CI 2.8–12.6) |

| ≤10 feet from height | 1119 | 5 | ||

| Age-Adjusted** High Fall from height | 144 | 4 | 12% Over-triage 56% Under-triage +LR 3.7 (95%CI 1.7–7.8) |

|

| Age-Adjusted Low Fall from height | 1047 | 5 | ||

| Falls from a Height OR Standing (n=2,176; 19 cases were missing age data) | >10 feet from height | 91 | 4 | 4% Over-triage 69% Under-triage +LR 7.3 (95%CI 3.2–16.9) |

| <=10 feet from height | 2072 | 9 | ||

| Age-Adjusted** High Fall from height | 145 | 4 | 7% Over-triage 69% Under-triage +LR 4.6 (95%CI 2.0–10.4) |

|

| Age-Adjusted Low Fall from height | 1999 | 9 | ||

| Motor Vehicle Crash (n=2,246) | Ejected | 41 | 0 | N/A none of those ejected needed a trauma center |

| Not Ejected**** | 2,185 | 20 | ||

| Intrusion >12 at seat or >18 elsewhere | 31 | 0 | N/A none of those who meet the intrusion criteria needed a trauma center | |

| Intrusion <=12 at seat and <=18 elsewhere No Intrusion | 2,195 | 20 | ||

| Death of another passenger | 30 | 2 | 1 % Over-triage 90% Under-triage +LR 7.42; (95%CI: 1.9–29.0). |

|

| No death of a passenger**** | 2,196 | 18 | ||

| No restraint use | 492 | 3 | 22% Over-triage 85% Under-triage +LR 0.7 (95%CI 0.24–1.93) |

|

| Restraint use**** | 1734 | 17 | ||

| Roll over | 287 | 2 | 13% Over-triage 90% Under-triage +LR 0.78 (95%CI 0.21–2.90) |

|

| No roll over**** | 1,939 | 18 | ||

| Prolonged extrication | 34 | 2 | 1.5% Over-triage 90% Under-triage +LR 6.55 (95%CI1.69–25.42) |

|

| No prolonged extrication**** | 2,192 | 18 | ||

| Auto vs. Pedestrian of Bicyclist (n=560) | Patient thrown | 196 | 4 | 36% Over-triage 60% Under-triage +LR 1.12 (95% CI 0.52–2.42) |

| Patient not thrown**** | 354 | 6 | ||

| Patient run over | 61 | 3 | 11 % Over-triage 70% Under-triage +LR 2.7(95%CI 1.02–7.18) |

|

| Patient not run over**** | 489 | 7 | ||

| Significant Impact (>20 mph) | 166 | 7 | 30% Over-triage 30% Under-triage +LR 2.32(95%CI 1.52–3.55) |

|

| No significant Impact (<20mph)**** | 384 | 3 |

Excludes 634 cases where fall height was not reported.

Age-Adjusted Fall Height: ≤ 3 years fall > 6 feet; 3–8 years fall > 8 feet; ≥ 8 years fall > 10 feet; +LR: Positive Likelihood Ratio

Excludes 86 cases where fall height was not reported.

Missing or unknown values were considered “no” for these responses.

For the 2,246 children in motor vehicle crashes, 20 needed a trauma center. Even though 41 children were reported to have been ejected from the vehicle none of them were found to have needed the resources of a trauma center. The current guidelines for intrusion include consideration of seating position relative to the intrusion. These criteria identified 31 cases, but none needed the resources of a trauma center. If we used the intrusion criteria that was used in a prior version of the Field Triage Decision Scheme, greater than 12 inches of intrusion in any location regardless of the patients position in the vehicle, 59 cases would have been identified and 1 of those needed the resources of a trauma center.15 For motor vehicle crashes, the under-triage rates were found to be high using the current Decision Scheme’s criteria. To address this we also evaluated the use of restraints, prolonged extrication, and rollover in addition to intrusion, ejection, and death of another passenger. Among those, restraint use appeared to be the best predictor of trauma center need with 3 of 20 cases being identified. When we combined the 3 variables in the guidelines with these 3 additional variables we identified 6 MVC cases that needed a trauma center decreasing the under-triage rate from 90% to 70% and increasing the over-triage rate from 4% to 35%.

Discussion

The Physiologic and Anatomic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme identified 73% of children who needed the resources of a trauma center. The remaining 27% of injured children who needed the resources of a trauma center need to be identified so that they can be transported to a facility that can rapidly provide the care that they need to improve their chances of achieving a positive outcome. This study illustrated that the current Mechanism of Injury Criteria did not identify the majority of children who needed the resources of a trauma center and were not identified using the Anatomic and Physiologic Criteria. Using the Mechanism of Injury Criteria resulted in an even higher under-triage rate for children compared to the rate found in an adult population (77% under-triage in children versus 60% in adults).11

One reason for this high rate of under-triage may be that the mechanisms included in the Mechanism of Injury Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme did not apply to more than a quarter of injured children. In contrast, in a similar study, only 2% of nearly 11,890 injured adults sustained mechanisms that were not included in the Field Triage Decision Scheme.11 This notable difference between applying the Mechanism of Injury Criteria to children versus adults likely reflects the fact that these criteria were developed for adult patients. As a consequence of the difficulty we had categorizing the pediatric mechanisms of injury, we expanded the available mechanism of injury categories that we included in our data form based on our experience in a prior pediatric-based study.3 However, even with this expanded list we were only able to categorize half of the cases that did not have an injury mechanism that was included in the Field Triage Decision Scheme. Improving the field triage of children who do not meet the Anatomic or Physiologic Criteria may require new and innovative ways of considering mechanism of injury that are different from those used in an adult population. Alternatively, improving trauma triage for children may require identifying completely different criteria that have not previously been considered.

Looking only at the children who had a mechanism of injury that is included in the Field Triage Decision Scheme, the criteria for the identified mechanism of injury still did a poor job of identifying children who needed the resources of a trauma center. The lowest under-triage rate for all of the specific mechanisms of injury was 10% for auto versus pedestrian. The individual criteria with the lowest under-triage rate (30%) was pedestrian or bicyclist struck with significant impact. While 10% is close to the suggested minimum under-triage rate of 5%, it is still high and the other Mechanism of Injury Criteria had much higher under-triage rates.16 Our attempts to use other Mechanism of Injury Criteria did not have a significant impact on improving the under triage rate. Therefore, addressing the additional mechanisms of injury that children experience will not be enough to improve triage accuracy for injured pediatric patients.

Interestingly, using the Mechanism of Injury Criteria did not have a big impact on over-triage in children, especially when compared to an adult population (6% over-triage in children versus 24% in adults11). There are no explicit recommendations for what an acceptable over-triage rate is but the 6% rate of over-triage that resulted from using the current Mechanism of Injury Criteria may indicate that the current criteria should continue to be used and additional criteria be added to assist with finding the missed children who need the resources of a trauma center.

Limitations

This paper has several limitations. The study benefited from getting EMS data directly from providers at the time that they arrived at the pediatric trauma center in their community. This methodology meant that we missed pediatric patients who were transported to local community hospitals. A recent study that included one of our study sites (Milwaukee, WI) found that 61% of pediatric patients transported for injury went to the community’s pediatric hospital and 63% of those who met the Physiologic Criteria of Field Triage Decision Scheme went to the local pediatric trauma facility.17 This means that while we likely had a representative sample of both severe and non-severe patients our data did not represent all injured children in the community and under-triage rates could be even higher than our estimates.

There were also components of the mechanism of injury criteria that EMS providers stated they did not know if they were present. We analyzed those cases as if the criteria were not present since even if they were the provider did not know about them. The effect of this is very different from a retrospective review because we conducted provider interviews. We felt this was the proper way to handle unknown variables and recognize that “unknown” was not a failure of documentation but the provider in fact was not aware if the factor was present or not.

Conclusion

Over a quarter of the children who needed the resources of a trauma center were not identified using the Physiologic or Anatomic Criteria of the Field Triage Decision Scheme. The Mechanism of Injury Criteria of the decision scheme did not include over a quarter of the mechanisms experienced by children transported by EMS for injury and did not appear to greatly enhance identification of children who need a trauma center. More work is needed to improve the tool used to assist EMS providers in the identification of children who need the resources of a trauma center.

Funding:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute Of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD075786. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Appendix 1: Data collection questions

Footnotes

The authors have no relevant financial conflicts of interest to report.

References

- 1.MacKenzie EJ, Rivara FP, Jurkovich GJ, Nathens AB, Frey KP, Egleston BL, Salkever DS, Scharfstein DO. A national evaluation of the effect of trauma-center care on mortality. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(4):366–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Faul M, Sugerman D, Pearson WS, Dulski T, Wald MM, Jurkovich GJ, Newgard CD, Lerner EB, Centers for Disease C, Prevention. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients: recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage, 2011. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-1):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lerner EB, Cushman JT, Drendel AL, Badawy M, Shah MN, Guse CE, Cooper A. Effect of the 2011 Revisions to the Field Triage Guidelines on Under-and Over-Triage Rates for Pediatric Trauma Patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2017;21(4):456–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newgard CD, Fu R, Zive D, Rea T, Malveau S, Daya M, Jui J, Griffiths DE, Wittwer L, Sahni R, Gubler KD, Chin J, Klotz P, Somerville S, Beeler T, Bishop TJ, Garland TN, Bulger E. Prospective Validation of the National Field Triage Guidelines for Identifying Seriously Injured Persons. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(2):146–158 e142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Newgard CD, Zive D, Holmes JF, Bulger EM, Staudenmayer K, Liao M, Rea T, Hsia RY, Wang NE, Fleischman R, Jui J, Mann NC, Haukoos JS, Sporer KA, Gubler KD, Hedges JR, investigators W. A multisite assessment of the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma field triage decision scheme for identifying seriously injured children and adults. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213(6):709–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Sluijs R, van Rein EAJ, Wijnand JGJ, Leenen LPH, van Heijl M. Accuracy of Pediatric Trauma Field Triage: A Systematic Review. JAMA Surg. 2018;153(7):671–676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Engum SA, Mitchell MK, Scherer LR, Gomez G, Jacobson L, Solotkin K, Grosfeld JL. Prehospital triage in the injured pediatric patient. J Pediatr Surg. 2000;35(1):82–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Esposito TJ, Offner PJ, Jurkovich GJ, Griffith J, Maier RV. Do prehospital trauma center triage criteria identify major trauma victims? Arch Surg. 1995;130(2):171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knopp R, Yanagi A, Kallsen G, Geide A, Doehring L. Mechanism of injury and anatomic injury as criteria for prehospital trauma triage. Ann Emerg Med. 1988;17(9):895–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lowe DK, Oh GR, Neely KW, Peterson CG. Evaluation of injury mechanism as a criterion in trauma triage. Am J Surg. 1986;152(1):6–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lerner EB, Shah MN, Cushman JT, Swor RA, Guse CE, Brasel K, Blatt A, Jurkovich GJ. Does Mechanism of Injury Predict Trauma Center Need? Prehospital Emergency Care. 2011;15(4):518–525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lerner EB, Willenbring BD, Pirrallo RG, Brasel KJ, Cady CE, Colella MR, Cooper A, Cushman JT, Gourlay DM, Jurkovich GJ, Newgard CD, Salomone JP, Sasser SM, Shah MN, Swor RA, Wang SC. A consensus-based criterion standard for trauma center need. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(4):1157–1163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lerner EB, Drendel AL, Falcone RA Jr., Weitze KC, Badawy MK, Cooper A, Cushman JT, Drayna PC, Gourlay DM, Gray MP, Shah MI, Shah MN. A consensus-based criterion standard definition for pediatric patients who needed the highest-level trauma team activation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78(3):634–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McGee S Simplifying likelihood ratios. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(8):646–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sasser SM, Hunt RC, Sullivent EE, Wald MM, Mitchko J, Jurkovich GJ, Henry MC, Salomone JP, Wang SC, Galli RL, Cooper A, Brown LH, Sattin RW, National Expert Panel on Field Triage CfDC, Prevention. Guidelines for field triage of injured patients. Recommendations of the National Expert Panel on Field Triage. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2009;58(RR-1):1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Committee on Trauma American College of Surgeons. Resources for Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. 2014; https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/quality-programs/trauma/vrc-resources/resources-for-optimal-care.ashx?la=en. Accessed November 4, 2019.

- 17.Lerner EB, Studnek JR, Fumo N, Banerjee A, Arapi I, Browne LR, Ostermayer DG, Reynolds S, Shah MI. Multicenter Analysis of Transport Destinations for Pediatric Prehospital Patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(5):510–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]