Abstract

Background and Aim:

The anaesthesiologists are at the highest risk of contracting infection of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in emergency room, operation theatres and intensive care units. This overwhelming situation can make them prone for psychological stress leading to anxiety and insomnia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We did an online self-administered questionnaire-based observational cross-sectional study amongst anaesthesiologists across India. The objectives were to find out the main causes for anxiety and insomnia in COVID-19 pandemic. Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale and Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) were used for assessing anxiety and insomnia.

Results:

Of 512 participants, 74.2% suffered from anxiety and 60.5% suffered from insomnia. The age <35 years, female sex, being married, resident doctors, fear of infection to self or family, fear of salary deductions, increase in working hours, loneliness due to isolation, food and accommodation issues and posting in COVID-19 duty were risk factors for anxiety. ISI scores ≥8 was observed in <35 years, unmarried, those with stress because of COVID-19, fear of loneliness, issues of food and accommodation, increased working hours and with GAD-7 score ≥5. Adjusted odd's ratio of insomnia in participants having GAD-7 score ≥5 was 10.499 (95% confidence interval 6.097–18.080; P < 0.001).

Conclusion:

The majority of anaesthesiologists on COVID-19 duty suffer from anxiety and insomnia. Addressing risk factors identified during this study with targeted interventions and psychosocial support will help them to cope better with the stress.

Key words: Anxiety, COVID-19, insomnia, mental health, psychology

INTRODUCTION

Novel Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak has affected millions of people worldwide and was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization (WHO) on 11th March 2020.[1] It spreads through fomites, aerosol droplets and contact from human to human with an incubation period of 5–6 days (ranges from 1 to 14 days).[2,3,4] High infectivity rate of this virus and associated mortality and morbidity have created a scare amongst the general population, causing social dysfunction, mass hysteria and a constant state of anxiety.[5,6] Several government and medical institutions, universities across the world have provided online platforms for psychological counselling and interventions to deal public health emergencies for patients, their family members, and other people affected by the pandemic.[6,7]

Health-care professionals are the vulnerable population in this scenario because of enhanced risk of exposure and contracting the infection (roughly 33 times) and chances of transmitting the infection to their loved ones.

The burden of an increasing number of patients on limited health-care facilities also leads to increase in working hours, depletion of personal protective equipment (PPE) and isolation and separation from family members. All these factors can make health care professionals more prone for anger, anxiety, insomnia and stress.[8] Feelings of anxiety, helplessness, loneliness, guilt and resultant insomnia can affect their mental health and decision making. Media reports on the pandemic every day about the increasing number of cases and mortality of frontline medical staff, also increase their apprehensions for personal and family safety. The wrong perception of some strata of society about medical professionals being the carrier of the virus also adds to their stress.

Anaesthesiologists are always at the frontline to manage disasters, epidemics, emergencies and natural calamities. Being experts in emergent airway management during perioperative anaesthesia, critical care management, and in the resuscitation of patients, the anaesthesiologists are playing a major role in COVID-19 pandemic.[9,10]

Due to their involvement in multiple aerosols generating procedures such as pre-oxygenation, mask ventilation, laryngoscopy, tracheal intubation, suctioning of orotracheal secretions and extubation, they have very high risk of contracting the infection, especially if adequate PPEs are not available. Besides, long hours in donned PPE in hot and humid weather, exhaustive prolonged work hours and stress related to the uncertainty of the outbreak can result in anxiety, depression, insomnia and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) amongst anaesthesiologists.[11]

Stress is considered to be the primary cause of insomnia.[12] Although there are studies published for identifying insomnia and related psychological effects of working in hospitals during the previous severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) outbreak,[13] there is a paucity of studies to evaluate the risk factors of anxiety and insomnia during the COVID-19 outbreak.

Hence, we did a questionnaire-based survey to assess the psychological impact (in terms of anxiety and insomnia) amongst anaesthesiologists, providing care to the COVID-19 patients in India. We also compared the prevalence rate of anxiety and insomnia amongst anaesthesiologists providing care to the COVID-19 patients versus those, who were not posted in COVID-19 wards or intensive care unit (ICU). We also aimed to find different factors associated with anxiety and insomnia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional observational study was done using an online self-administered Google forms software-based questionnaire by the voluntary participation of anaesthesiologists from different hospitals across India, after approval from the institutional ethics committee (SNMC/IEC/IIP/2020/001). The data were collected from 12th May 2020 to 22nd May 2020. The anaesthesiologists actively involved in the care of COVID-19 patients were included in this study.

All participants provided their informed consent for the study. Only a single response to the questionnaire was permitted for each person. The participants were allowed to leave the survey at any point during the survey. All participants were assured concerning the anonymity and confidentiality of their data, and were provided with information about the nature and purpose of the study and the procedure, and were informed about their right to retract their data at any time.

The questionnaire [Table 1] consisted of queries about age groups, gender, marital status, designation of the doctor, corona ward or ICUs posting with the duration of working days. The probable reasons of stress (anxiety and insomnia) during the times of coronavirus epidemic were also asked. Anxiety was rated on the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scale, while insomnia was rated on the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

Table 1.

Questionnaire

| Consent from participants |

|---|

| I agree to participate in the research study |

| I understand the purpose and nature of this study and I am participating voluntarily. I understand that I can withdraw from the study at any time, without any penalty or consequences |

| I grant permission for the data generated from this interview to be used in the researcher’s publications on this topic |

| Yes |

| No |

| Age (years) |

| <30 |

| 31-40 |

| 41-50 |

| 51-60 |

| >60 |

| Gender |

| Male |

| Female |

| Marital status |

| Unmarried |

| Married |

| Designation |

| Junior resident |

| Senior resident |

| Junior consultant |

| Senior consultant |

| Are you feeling stressed due to COVID-19? |

| Yes |

| No |

| If yes, please select probable reason (tick all applicable) |

| Fear of self-infection |

| Family exposure risk |

| Increased working hours |

| Salary deductions |

| Non-availability of PPE |

| Loneliness |

| Food and accommodation issues |

| Others |

| Corona ward/ICU posting status |

| Yes |

| No |

| Duration of posting in corona ward/ICU |

| ≤7 days |

| >7 days |

| Anxiety questionnaire |

| Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Not being able to stop or control worrying |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Worrying too much about different things |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Trouble relaxing |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Being so restless that it is hard to sit still |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Becoming easily annoyed or irritable |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Feeling afraid, as if something awful might happen |

| 0: Not at all |

| 1: Several days |

| 2: More than half the days |

| 3: Nearly every day |

| Insomnia questionnaire |

| Difficulty falling asleep |

| 0: None |

| 1: Mild |

| 2: Moderate |

| 3: Severe |

| 4: Very severe |

| Difficulty staying asleep |

| 0: None |

| 1: Mild |

| 2: Moderate |

| 3: Severe |

| 4: Very severe |

| Problems waking up too early |

| 0: None |

| 1: Mild |

| 2: Moderate |

| 3: Severe |

| 4: Very severe |

| How SATISFIED/DISSATISFIED are you with your CURRENT sleep pattern? |

| 0: Very satisfied |

| 1: Satisfied |

| 2: Moderately |

| 3: Satisfied dissatisfied |

| 4: Very dissatisfied |

| How NOTICEABLE to others do you think your sleep problem is in terms of impairing the quality of your life? |

| 0: Not at all Noticeable |

| 1: A Little |

| 2: Somewhat |

| 3: Much |

| 4: Very much noticeable |

| How WORRIED/DISTRESSED are you about your current sleep problem? |

| 0: Not at all worried |

| 1: A little |

| 2: Somewhat |

| 3: Much |

| 4: Very much worried |

| To what extent do you consider your sleep problem to INTERFERE with your daily functioning (e.g. daytime fatigue, mood, ability to function at work/daily chores, concentration, memory and mood) CURRENTLY? |

| 0: Not at all interfering |

| 1: A little |

| 2: Somewhat |

| 3: Much |

| 4: Very much interfering |

COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease 2019, ICU – Intensive care units, PPE – Personal protective equipment

The GAD-7 scale is a 7-item, self-rated scale used as a screening tool to measure the severity of anxiety. Every answer is rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale from 0 being not at all to 3 being nearly every day. The scale then measures anxiety as minimum or no anxiety (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14) and severe (15–21).[14,15] The total GAD-7 score ≥5 was considered as the presence of anxiety.

The ISI is a 7-item self-report questionnaire, used to assess the nature, severity and impact of insomnia. A 5-point Likert scale is used to rate each answer from 0 as no problem to 4 as a very severe problem, giving a total score ranging from 0 to 28. The total score is then interpreted as the absence of insomnia (0–7), sub-threshold insomnia (8–14), moderate insomnia (15–21) and severe insomnia (22–28).[16,17] The cut off score of ≥8 was considered to be the presence of insomnia.

The sample size was calculated by openepi.com software based on a study of Zhang et al.[8] Considering the prevalence of insomnia as 36.1%, we estimated a sample size of 461 participants at 95% confidence interval, 30% relative precision and 10% contingency. We received a total of 512 completed responses. The statistical analysis was done using Statistical Package for Social Sciences version 23.0., (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). All qualitative data were expressed as proportions and percentages. Chi-square test was used for descriptive statistics (n, %). To examine the association between demographic factors with insomnia and anxiety multiple binary logistic regression was used. A similar assessment was done for other demographic factors. The P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sociodemographic data, exposure to COVID-19 patients and perception characteristics were enlisted in Table 2.

Table 2.

Sociodemographic data and perception characteristics

| Sociodemographic variables | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | |

| <30 | 199 (38.8) |

| 31-35 | 168 (32.8) |

| 36-40 | 55 (10.7) |

| 41-45 | 32 (6.8) |

| 46-50 | 16 (3.4) |

| >50 | 42 (8.2) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 227 (44.3) |

| Male | 285 (55.7) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 331 (64.7) |

| Unmarried | 181 (35.3) |

| Designation | |

| Resident | 350 (68.4) |

| Consultant | 162 (31.6) |

| Are you feeling stressed due to COVID-19 | |

| No | 95 (18.6) |

| Yes | 417 (81.4) |

| Fear of self-infection | |

| No | 212 (41.4) |

| Yes | 300 (58.6) |

| Family exposure risk | |

| No | 202 (39.5) |

| Yes | 310 (60.5) |

| Salary deductions | |

| No | 421 (82.2) |

| Yes | 91 (17.8) |

| Loneliness | |

| No | 345 (67.4) |

| Yes | 167 (32.6) |

| Food and accommodation issues | |

| No | 349 (68.2) |

| Yes | 163 (31.8) |

| Increased working hours | |

| No | 434 (84.8) |

| Yes | 78 (15.2) |

| Non-availability of PPE | |

| No | 369 (72.1) |

| Yes | 143 (27.9) |

| Posting in COVID-19 | |

| No | 198 (38.7) |

| Yes | 314 (61.3) |

| Duration of posting in COVID-19 ward/ICU (days) | |

| ≤7 | 144 (45.9) |

| >7 | 170 (54.1) |

| GAD-7 Score | |

| <5 | 132 (25.8) |

| ≥5 | 380 (74.2) |

| ISI score | |

| <8 | 202 (39.5) |

| ≥8 | 310 (60.5) |

COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease 2019, ICU – Intensive care units, PPE – Personal protective equipment, GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7, ISI – Insomnia Severity Index

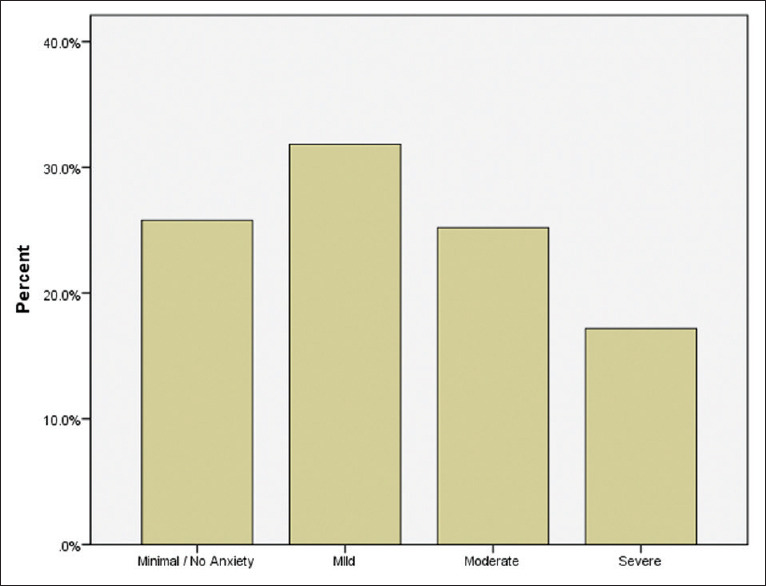

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 score

As far as severity of anxiety is concerned, 25.8% anaesthesiologists had minimum or no anxiety, 31.8% had mild anxiety, 25.2% had moderate anxiety and 17.2% had severe anxiety [Figure 1]. Participants were divided into two groups based on GAD-7 - minimum or no anxiety group (GAD-7 score <5) and anxiety group (GAD-7 score ≥5). Based on GAD-7 score, overall prevalence of anxiety among participating anaesthesiologists was 74.2% (380). The GAD-7 score ≥5, was found in 79.4% in <30 years of age, 75% in 31–35 years, 70.9% in 36–40 years, 75% in 41–45 years, 68.8% in 46–50 years and 52.4% in >50 years. About 82.8% (188) female anaesthesiologists and 67.4% (192) male anaesthesiologists had GAD-7 score ≥5. With regard to marital status, 73.7% of married and 75.1% of unmarried anaesthesiologists had GAD-7 score ≥5. Out of 417 anaesthesiologists who were stressed due to corona, 80.6% (336) had GAD-7 score ≥5. The GAD-7 score ≥5 was found in 78% (245) anaesthesiologists posted on COVID-19 duty and 68.2% (135) of amongst those on non-COVID-19 duty. The fear of self-infection, family exposure risk, salary deduction, loneliness, food and accommodation issues, increased working hours and non-availability of PPE were common factors of anxiety. The duration of duty (≤ 7 days or > 7 days) had no statistically significant difference on anxiety and insomnia [Table 3].

Figure 1.

Severity of anxiety depending upon Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 score

Table 3.

Comparison between no anxiety and anxiety among anaesthesiologists with demographic data and their multiple binary logistic regression analysis

| Variables | Total, n (%) | GAD <5, n (%) | GAD ≥5, n (%) | P | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||||

| <30 | 199 (100.0) | 41 (20.6) | 158 (79.4) | 0.016 | Ref |

| 31-35 | 168 (100.0) | 42 (25.0) | 126 (75.0) | 0.809 (0.402-1.626) | |

| 36-40 | 55 (100.0) | 16 (29.1) | 39 (70.9) | 0.636 (0.232-1.746) | |

| 41-45 | 32 (100.0) | 8 (25.0) | 24 (75.0) | 0.898 (0.220-3.674) | |

| 46-50 | 16 (100.0) | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.8) | 0.770 (0.162-3.665) | |

| >50 | 42 (100.0) | 20 (47.6) | 22 (52.4) | 0.444 (0.139-1.415) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 227 (100.0) | 39 (17.2) | 188 (82.8) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Male | 285 (100.0) | 93 (32.6) | 192 (67.4) | 0.402 (0.229-0.703) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 331 (100.0) | 87 (26.3) | 244 (73.7) | 0.725 | Ref |

| Unmarried | 181 (100.0) | 45 (24.9) | 136 (75.1) | 0.707 (0.373-1.342) | |

| Designation | |||||

| Resident | 350 (100.0) | 79 (22.6) | 271 (77.4) | 0.015 | Ref |

| Consultant | 162 (100.0) | 53 (32.7) | 109 (67.3) | 1.179 (0.529-2.624) | |

| Are you feeling stressed due to COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 95 (100.0) | 51 (53.7) | 44 (46.3) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 417 (100.0) | 81 (19.4) | 336 (80.6) | 1.487 (0.605-3.654) | |

| Fear of self-infection | |||||

| No | 212 (100.0) | 77 (36.3) | 135 (63.7) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 300 (100.0) | 55 (18.3) | 245 (81.7) | 1.040 (0.532-2.034) | |

| Family exposure risk | |||||

| No | 202 (100.0) | 76 (37.6) | 126 (62.4) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 310 (100.0) | 56 (18.1) | 254 (81.9) | 2.099 (1.033-4.263) | |

| Salary deductions | |||||

| No | 421 (100.0) | 119 (28.3) | 302 (71.7) | 0.006 | Ref |

| Yes | 91 (100.0) | 13 (14.3) | 78 (85.7) | 1.279 (0.567-2.887) | |

| Loneliness | |||||

| No | 345 (100.0) | 109 (31.6) | 236 (68.4) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 167 (100.0) | 23 (13.8) | 144 (86.2) | 1.802 (0.878-3.698) | |

| Food and accommodation issues | |||||

| No | 349 (100.0) | 107 (30.7) | 242 (69.3) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 163 (100.0) | 25 (15.3) | 138 (84.7) | 1.228 (0.606-2.488) | |

| Increased working hours | |||||

| No | 434 (100.0) | 124 (28.6) | 310 (71.4) | 0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 78 (100.0) | 8 (10.3) | 70 (89.7) | 1.490 (0.596-3.727) | |

| Non-availability of PPE | |||||

| No | 369 (100.0) | 108 (29.3) | 261 (70.7) | 0.004 | Ref |

| Yes | 143 (100.0) | 24 (16.8) | 119 (83.2) | 0.947 (0.491-1.826) | |

| Posting in COVID-19 ward/ICU | |||||

| No | 198 (100.0) | 63 (31.8) | 135 (68.2) | 0.013 | Ref |

| Yes | 314 (100.0) | 69 (22.0) | 245 (78.0) | 1.510 (0.043-52.650) | |

| Duration of posting in COVID-19 ward/ICU (days) | |||||

| ≤7 | 144 (100.0) | 32 (22.2) | 112 (77.8) | <0.922 | Ref |

| >7 | 170 (100.0) | 37 (21.8) | 133 (78.2) | 1.5109 (0.04-52.6) | |

| Insomnia | |||||

| No insomnia | 202 (100.0) | 107 (53.0) | 95 (47.0) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Insomnia | 310 (100.0) | 25 (8.1) | 285 (91.9) | 10.557 (6.120-18.211) |

COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease 2019, ICU – Intensive care units, PPE – Personal protective equipment, aOR – Adjust odds ratio, GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

On multiple binary logistic regression analysis, significant factors included, female anaesthesiologists (adjust odds ratio [aOR] - 0.402; 95% confidence interval [CI] - 0.229–0.703; P < 0.001), fear of family exposure (aOR - 2.099; 95% CI - 1.033–4.263; P < 0.040) and in participants having insomnia with ISI score >8 (aOR - 10.557 95% CI - 6.120–18.211; P < 0.001) [Table 3].

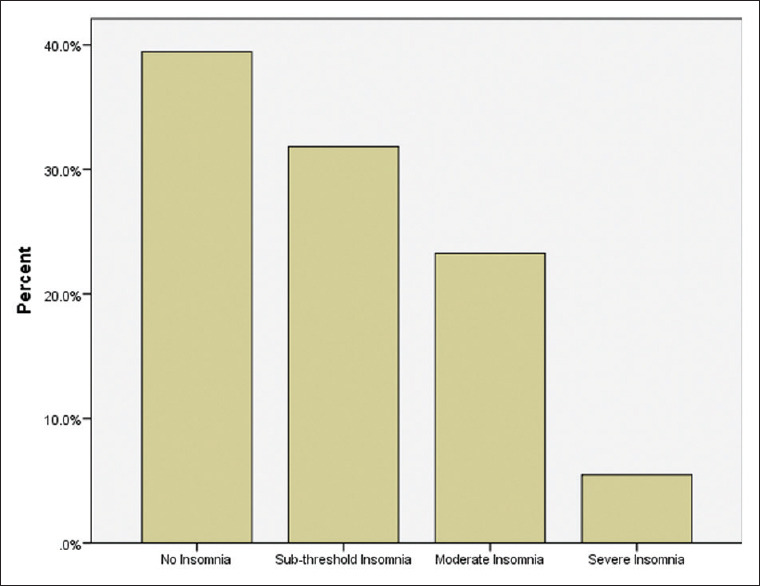

Insomnia Severity Index

Out of 512 anaesthesiologists 39.5% (202) had no insomnia, 31.8% (163) had sub-threshold insomnia, 23.2% (119) had moderate insomnia and 5.5% (28) of respondents reported severe insomnia. [Figure 2] Participants were divided into two groups; no insomnia (ISI <8) and insomnia group (ISI ≥ 8). The overall prevalence of insomnia was found to be 60.5% (314). The ISI score ≥ 8 was found higher in <30 years (67.8%) and in 41–45 years (65.6%) of age. The ISI score ≥ 8 was found in 66.5% female anaesthesiologists and 55.8% male anaesthesiologists. With regard to marital state, 57.4% of married and 66.3% of unmarried anaesthesiologists had ISI score ≥ 8. Out of 417 anaesthesiologists, who were stressed due to COVID-19, 66.7% (274) had ISI ≥ 8. The ISI ≥ 8 was found in 68.2% anaesthesiologists posted in COVID-19 duty, 48.5% of among those not on COVID-19 duty. The fear of self-infection, family exposure risk, salary deduction, loneliness, food and accommodation issues, increased working hours and non-availability of PPE were the most common factors of anxiety. Multiple binary logistic regression analysis revealed significant cause of insomnia was increased work hours [Table 4].

Figure 2.

Severity of insomnia depending upon Insomnia Severity Index

Table 4.

Comparison between no insomnia and insomnia among anaesthesiologists with demographic data and their multiple binary logistic regression analysis

| Sociodemographic Variables | Total, n (%) | No Insomnia, n (%) | Insomnia n (%) | P | aOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups (years) | |||||

| <30 | 199 (100.0) | 64 (32.2) | 135 (67.8) | <0.001 | Ref |

| 31-35 | 168 (100.0) | 63 (37.5) | 105 (62.5) | 1.148 (0.633-2.082) | |

| 36-40 | 55 (100.0) | 26 (47.3) | 29 (52.7) | 0.913 (0.381-2.190) | |

| 41-45 | 32 (100.0) | 11 (34.4) | 21 (65.6) | 2.641 (0.803-8.679) | |

| 46-50 | 16 (100.0) | 10 (62.5) | 6 (37.5) | 0.506 (0.125-2.055) | |

| >50 | 42 (100.0) | 28 (66.7) | 14 (33.3) | 0.797 (0.268-2.365) | |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 227 (100.0) | 76 (33.5) | 151 (66.5) | 0.014 | Ref |

| Male | 285 (100.0) | 126 (44.2) | 159 (55.8) | 0.758 (0.465-1.238) | |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married | 331 (100.0) | 141 (42.6) | 190 (57.4) | 0.049 | Ref |

| Unmarried | 181 (100.0) | 61 (33.7) | 120 (66.3) | 1.184 (0.690-2.032) | |

| Designation | |||||

| Resident | 350 (100.0) | 116 (33.1) | 234 (66.9) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Consultant | 162 (100.0) | 86 (53.1) | 76 (46.9) | 0.504 (0.253-1.003) | |

| Are you feeling stressed due to Corona | |||||

| No | 95 (100.0) | 59 (62.1) | 36 (37.9) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 417 (100.0) | 143 (34.3) | 274 (65.7) | 2.014 (0.866-4.686) | |

| Fear of self-infection | |||||

| No | 212 (100.0) | 99 (46.7) | 113 (53.3) | 0.005 | Ref |

| Yes | 300 (100.0) | 103 (34.3) | 197 (65.7) | 0.861 (0.487-1.521) | |

| Family exposure risk | |||||

| No | 202 (100.0) | 92 (45.5) | 110 (54.5) | 0.023 | Ref |

| Yes | 310 (100.0) | 110 (35.5) | 200 (64.5) | 0.858 (0.463-1.588) | |

| Salary deductions | |||||

| No | 421 (100.0) | 174 (41.3) | 247 (58.7) | 0.62 | Ref |

| Yes | 91 (100.0) | 28 (30.8) | 63 (69.2) | 1.057 (0.547-2.041) | |

| Loneliness | |||||

| No | 345 (100.0) | 153 (44.3) | 192 (55.7) | 0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 167 (100.0) | 49 (29.3) | 118 (70.7) | 0.925 (0.520-1.646) | |

| Food and accommodation issues | |||||

| No | 349 (100.0) | 152 (43.6) | 197 (56.4) | 0.005 | Ref |

| Yes | 163 (100.0) | 50 (30.7) | 113 (69.3) | 1.059 (0.600-1.869) | |

| Increased working hours | |||||

| No | 434 (100.0) | 188 (43.3) | 246 (56.7) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 78 (100.0) | 14 (17.9) | 64 (82.1) | 3.157 (1.478-6.740) | |

| Non-availability of PPE | |||||

| No | 369 (100.0) | 156 (42.3) | 213 (57.7) | 0.036 | Ref |

| Yes | 143 (100.0) | 46 (32.2) | 97 (67.8) | 0.866 (0.506-1.482) | |

| Posting in COVID-19 | |||||

| No | 198 (100.0) | 102 (51.5) | 96 (48.5) | <0.001 | Ref |

| Yes | 314 (100.0) | 100 (31.8) | 214 (68.2) | 0.496 (0.019-13.178) | |

| Duration of posting in COVID-19 Ward/ICU (days) | |||||

| ≤7 | 144 (100.0) | 85 (59.0) | 59 (41.0) | <0.279 | Ref |

| >7 | 170 (100.0) | 90 (52.9) | 80 (47.1) | 0.496 (0.019-13.7) | |

| GAD score <5 | |||||

| <5 | 132 (100.0) | 107 (81.1) | 25 (18.9) | <0.001 | Ref |

| ≥5 | 380 (100.0) | 95 (25.0) | 285 (75.0) | 10.499 (6.097-18.080) |

COVID-19 – Coronavirus disease 2019, ICU – Intensive care units, PPE – Personal protective equipment, aOR – Adjusted odds ratio, GAD-7 – Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

DISCUSSION

There have been multiple studies conducted to understand anxiety and insomnia in HCW comprising of treating physicians and nursing staff across the world. However, this study is probably, the first study about anxiety and insomnia in anaesthesiologists in the Indian subcontinent in COVID 19 pandemic.

The prevalence of anxiety (74.2%) and insomnia (60.5%) was found to be higher in our study compared to other studies during COVID-19 in China [8,17,18] and during the SARS epidemic in Taiwan.[19,20] This could be attributed to the late arrival of COVID-19 in India, when China, the USA, Italy and major parts of Europe had already reported significant hospitalisations and mortality, reports of many frontline HCWs getting infected coming from across the world, media and social media hype, uncertainty about their own and family members' safety and government preparedness to effectively deal with COVID-19 pandemic in India.

Factors related to anxiety and insomnia in our study included age <35 years, female sex, those doing residency (post-graduation or senior residents), fear of infection to the self or family, fear of salary deduction, fear of facing loneliness during isolation or food and accommodation issues, increased working hours and fear related to posting on COVID-19 duty. Married anaesthesiologists had higher incidence of anxiety, while insomnia was higher in unmarried anaesthesiologists. Dai et al.[18] also found similar results in their survey.

People, who are separated from their family members due to work and those who lack a close relationship are more prone to mental health problems. This highlights the importance of support of family and friends to keep good mental health.[21] Female anaesthesiologists had higher levels of stress and burnout compared to men.[22] This is because of the accumulation of tasks and her greater commitment to issues related for work and family when they take a double or even triple workload (work, home and family).[8,23] The resident anaesthesiologists are more prone to mental health problems, because of the long floor duty hours and direct involvement in patient care compared to consultant anaesthesiologists.

The long duration of isolation and quarantine often leads to anxiety, frustration, insomnia and irritability and may lead to PTSD. Increased stress to meet the high expectations of patient care with disturbances in circadian rhythm also impairs a doctor's ability to sleep resulting in insomnia, severe sleep debt and daytime sleepiness. Stress activates the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal system, leading to insomnia which further activates the axis leading to a vicious cycle of insomnia and anxiety.[24]

In the current existing scenario, anaesthesiologists and other HCWs are prone to physical and mental exhaustion as they are caring for the increasing load of COVID-19 patients under unphysiological conditions caused due to wearing of PPEs and other restrictions such as working without water, food and air conditions for hours together, constant exposure to contagion itself, constantly worrying about transmitting the infection to family members, friends and colleagues, living away from home and increased number of duty hours and night duties. They also have to be abreast of constantly changing treatment guidelines and government policies.

The study conducted by Naushad et al.[25] also pointed out, that HCWs especially those working in emergency units, ICUs and infectious disease wards are at higher risk of developing adverse psychiatric impact due to the speculations of mode of transmission, rapidity of spread and lack of definitive treatment protocols or vaccine of COVID-19.

Kang et al.[19] suggested that staff accessed limited mental healthcare services, distressed staff nonetheless saw these services as important resources to alleviate acute mental health disturbances and improve their physical health perceptions. They emphasised the importance of being prepared to support frontline workers through mental health interventions at times of widespread crisis. The Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists, in coordination with its state and city branches, provided training and technical resources as well as issued the advisories to ensure safety of patients and the anaesthesiologists during COVID-19 pandemic.[26,27]

Mohindra et al.[28] suggested that positive motivational factors such as supportive and proud family and colleagues, positive role models, validation and appreciation by peers/patients, positive caretaking experience, a sense of validation of existence, knowledge and acceptance of the possible inevitability of infection can help in boosting the morale of HCPs.

Important clinical and socioeconomic strategies are needed to recognise and understand the source of anxiety and fear before the support of HCWs in COVID-19 pandemic. Chronic fatigue, trouble concentrating, sleep deprivation, mood swings, behavioural changes, loss of appetite and poor work performance are signs of stress.[29] Early detection of stress and providing them with safe, conducive and assuring working environment without putting them to undue physical strain by regulating their rotation and number of hours at work with adequate physical rest and mental relaxation in between, providing temporary accommodation to those on COVID-19 duty to isolate them from their family, not to add to their financial worries, providing them with health and life insurance, keeping people with mental health issues or those on medications for psychiatric disorders can reduce the stress. The setting up of a helpline for in person, online or tele-counselling, psychoeducation and cognitive behaviour therapy by the higher authorities or government will be helpful to minimise stress of HCWs.

Cai et al.[30] also evaluated the factors responsible for the reduction of stress due to COVID-19. On a personal level, HCWs can take care of their mental health by staying away from 'too' much news or discussions, rumours and false information, to be in physical isolation, not in social isolation by connecting online to family and friends and by getting involved in physical exercises and hobbies, practicing yoga, sleep hygiene, relaxation and music therapy.[31] The emphasis should be on regular screening of medical personnel involved in the treatment of COVID-19 patients for evaluating stress, depression and anxiety by multidisciplinary psychiatric teams.[32]

Limitations of this study include indirect method of interview with self-reported questionnaires due to prevailing conditions worldwide and involvement of anaesthesiologists from India only.

CONCLUSION

This study pointed out that majority of anaesthesiologists on COVID-19 duty suffer from some degree of anxiety and insomnia. Addressing risk factors identified during this study with targeted interventions and providing them with required support can help in mitigating it.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank Dr Sandeep Goyal, Consultant Psychiatrist, Apollo Hospital, Ludhiana (Ex- Professor, Department of Psychiatric, DMC Medical College), Dr MeenaNeelam, Department of Anaesthesiology and Critical care, Dr S N Medical College, Jodhpur and Dr Akhil Dhanesh Goel, Department of Community Medicine and Family Medicine, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Jodhpur in the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1. [Last accessed on 2020 May 15];WHO/Europe | Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak-WHO announces COVID-19 outbreak a pandemic [WWW Document], n.d. URL http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/health-emergencies/coronavirus-covid-19/news/news/2020/3/who-announces-covid-19-outbreak-a-pandemic . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Wang W, Zhao X, Zai J, Zhao Q, Li Y, Chaillon A. Transmission dynamics and evolutionary history of 2019-nCoV. J Med Virol. 2020;92:501–11. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lauer SA, Grantz KH, Bi Q, Jones FK, Zheng Q, Meredith HR, et al. The incubation period of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) from publicly reported confirmed cases: Estimation and application. Ann Intern Med. 2020;172:577–82. doi: 10.7326/M20-0504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duan L, Zhu G. Psychological interventions for people affected by the COVID-19 epidemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:300–2. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Health Commission of China. Notice on the Issuance of Guidelines for Emergency Psychological Crisis Intervention in Pneumonia for Novel Coronavirus Infections. [Last accessed on 2020 May 25]. Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/xcs/zhengcwj/202001/6adc08b966594253b2b791be5c3b9467.shtml .

- 7.Roberts AR, editor. Crisis Intervention Handbook: Assessment, Treatment, and Research. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang M, Dong H, Lu Z. Role of anaesthesiologists during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in China. Br J Anaesth. 2020:666–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bajwa SJS, Sarna R, Bawa C, Mehdiratta L. Peri-operative and critical care concerns in coronavirus pandemic. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:267–74. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_272_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wu P, Fang Y, Guan Z, Fan B, Kong J, Yao Z, et al. The psychological impact of the SARS epidemic on hospital employees in China: Exposure, risk perception, and altruistic acceptance of risk. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:302–11. doi: 10.1177/070674370905400504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morin CM, Rodrigue S, Ivers H. Role of stress, arousal, and coping skills in primary insomnia. Psychosom Med. 2003;65:259–67. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000030391.09558.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brooks SK, Dunn R, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, Greenberg N. A systematic, thematic review of social and occupational factors associated with psychological outcomes in healthcare employees during an infectious disease outbreak. J Occup Environ Med. 2018;60:248–57. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–7. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Löwe B, Decker O, Müller S, Brähler E, Schellberg D, Herzog W, et al. Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Med Care. 2008;1:266–74. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318160d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bastien CH, Vallières A, Morin CM. Validation of the Insomnia Severity Index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/s1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morin CM, Belleville G, Bélanger L, Ivers H. The Insomnia Severity Index: Psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dai Y, Hu G, Xiong H, Qiu H, Yuan X. Psychological impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak on healthcare workers in China. [Last accessed on 2020 May 19];MedRxiv 2020.03.03.20030874. doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.03.03.20030874 . [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang L, Ma S, Chen M, Yang J, Wang Y, Li R, et al. Impact on mental health and perceptions of psychological care among medical and nursing staff in Wuhan during the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak: A cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:11–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su TP, Lien TC, Yang CY, Su YL, Wang JH, Tsai SL, et al. Prevalence of psychiatric morbidity and psychological adaptation of the nurses in a structured SARS caring unit during outbreak: A prospective and periodic assessment study in Taiwan. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:119–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ennis E, Bunting BP. Family burden, family health and personal mental health. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kluger MT, Townend K, Laidlaw T. Job satisfaction, stress and burnout in Australian specialist anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:339–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2003.03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calumbi RA, Amorim JA, Maciel CM, Damázio Filho O, Teles AJ. Evaluation of the quality of life of anesthesiologists in the city of Recife. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2010;60:42–51. doi: 10.1016/s0034-7094(10)70005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akerstedt T. Psychosocial stress and impaired sleep. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;32:493–501. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naushad VA, Bierens JJ, Nishan KP, Firjeeth CP, Mohammad OH, Maliyakkal AM, et al. A systematic review of the impact of disaster on the mental health of medical responders. Prehosp Disaster Med. 2019;34:632–43. doi: 10.1017/S1049023X19004874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malhotra N, Bajwa SJ, Joshi M, Mehdiratta L, Trikha A. COVID operation theatre- advisory and position statement of Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists (ISA national) Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:355–62. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_454_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malhotra N, Joshi M, Datta R, Bajwa SJ, Mehdiratta L. Indian Society of Anaesthesiologists (ISA National) advisory and position statement regarding COVID-19. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:259–63. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_288_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mohindra R, Suri V, Bhalla A, Singh SM. Issues relevant to mental health promotion in frontline health care providers managing quarantined/isolated COVID19 patients. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;51:102084. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102084. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp. 2020.102084. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 32289728; PMCID: PMC7138416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta B, Bajwa SJ, Malhotra N, Mehdiratta L, Kakkar K. Tough times and Miles to go before we sleep- Corona warriors. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:S120–4. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_565_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cai H, Tu B, Ma J, Chen L, Fu L, Jiang Y, et al. Psychological impact and coping strategies of frontline medical staff in Hunan between January and march 2020 during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Hubei, China. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e924171. doi: 10.12659/MSM.924171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sood S. Psychological effects of the Coronavirus disease-2019 pandemic. RHiME. 2020;7:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: A review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]