Abstract

Background

Although frailty has been associated with major morbidity/mortality and increased length of stay after cardiac surgery, few studies have examined functional outcomes. We hypothesized that frailty would be independently associated with decreased functional status, increased discharge to a non-home location, and longer duration of hospitalization after cardiac surgery, and that delirium would modify these associations.

Methods

This was an observational study nested in two trials, each of which was conducted by the same research team with identical measurement of exposures and outcomes. The Fried frailty scale was measured at baseline. The primary outcome (defined prior to data collection) was functional decline, defined as ≥2-point decline from baseline in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) score at 1-month after surgery. Secondary outcomes were absolute decline in IADL score, discharge to a new non-home location and duration of hospitalization. Associations were analyzed using linear, logistic, and Poisson regression models with adjustments for variables considered prior to analysis (age, gender, race, and logistic EuroSCORE) and in a propensity-score analysis.

Results

Data were available from 133 patients (83 from one trial and 50 from the second trial). The prevalence of frailty was 33% (44/133). In adjusted models, frail patients had increased odds of functional decline (primary outcome; OR 2.41; 95%CI 1.03–5.63; p=0.04) and greater decline at 1-month in the secondary outcome of absolute IADL score (−1.48, 95%CI −2.77 to −0.30, p=0.019), compared to non-frail patients. Delirium significantly modified the association of frailty and change in absolute IADL score at 1-month. In adjusted hypothesis-generating models using secondary outcomes, frail patients had increased discharge to a new non-home location (OR 3.25; 95%CI 1.37–7.69; p=0.007) and increased duration of hospitalization (1.35 days; 95%CI 1.19–1.52; p<0.0001) compared to non-frail patients. The increased duration of hospitalization, but not change in functional status or discharge location, was partially mediated by increased complications in frail patients.

Conclusions

Frailty may identify patients at risk of functional decline at 1-month after cardiac surgery. Perioperative strategies to optimize frail cardiac surgery patients are needed.

INTRODUCTION

Frailty is a geriatric syndrome characterized by lack of resilience to stressors1 The prevalence of frailty has been estimated to be 10–60% in patients with cardiovascular disease2 and in multiple studies, frailty has been associated with major morbidity/mortality and increased length of stay after cardiac surgery.3,4 However, as noted by two recent systematic reviews,5,6 there are few studies which have determined whether frailty identifies patients at risk for worse functional outcomes or non-home discharge destination. There is also little information on whether delirium interacts with frailty to increase susceptibility to functional decline, but such an interaction would identify the most vulnerable older adults at discharge. For older adults undergoing surgery, preservation of functional status and avoiding institutionalization are key goals, while for health systems, minimizing length of stay is becoming increasingly important.

Although there are many ways to measure frailty, the Fried frailty scale has been widely used and validated in both community-dwelling and hospitalized patients.7 Much of the popularity of the Fried scale may be traced to its basis in a biologic phenotype of sarcopenia and low energy expenditure. Patients categorized as frail are thought to be at high-risk for functional decline after the stress of cardiac surgery, but this association has not been well-documented. However, such information is critically important for risk-stratification, surgical decision-making, and perioperative planning. Importantly, given the biologic basis of frailty, such information could provide a compelling rationale for the development and implementation of prehabilitation programs for frail older adults undergoing cardiac surgery that are targeted at the underlying biology of sarcopenia and low energy expenditure.8

In this nested observational study, we hypothesized that baseline frailty would be associated with functional decline at 1-month (primary outcome), decline in absolute Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) score at 1-month, increased discharge to a non-home location, and longer duration of hospitalization, and that delirium would modify these associations.

METHODS

Study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine (jhmeirb@jhmi.edu). Written informed consent was obtained from patients. The data in this analysis were collected during two trials, each of which was submitted for registration on www.clinicaltrials.gov prior to enrollment (NCT00981474; PI Hogue; submitted 9/21/2009 and NCT02587039; PI Brown; submitted 7/9/2014). This manuscript adheres to the applicable STROBE guidelines.

Study Design and Patients

This was an observational study nested in two separate single-site trials at an academic center. Each trial was conducted by the same team with identical measurement of frailty and functional outcomes. The primary question (association of frailty with 1-month functional decline) was pre-specified prior to patient enrollment for patients in this analysis. Data from the two trials were combined for this study.

The primary aim of the first trial was to determine if targeted mean arterial pressure during cardiopulmonary bypass based on cerebral autoregulation monitoring reduced a composite outcome (stroke, ischemic lesions, cognitive change) compared with standard blood pressure management (registration NCT00981474). Patients ≥55 years old were enrolled from August 2014—May 2016. Inclusion criteria were coronary artery bypass (CAB) and/or valve surgery that required cardiopulmonary bypass and who were at high risk for neurologic complications9 as determined by a Johns Hopkins risk score that generally excluded patients in the lowest quartile of risk. Exclusion criteria were baseline delirium, hepatic dysfunction, contraindications to MRI, dialysis, non-English speaking, inability to follow-up, and emergency surgery. 83 patients were included from this trial.

The primary aim of the second trial was to determine if remote ischemic preconditioning reduced postoperative delirium (trial registration NCT02587039). Patients were enrolled from July 2014—December 2015. Inclusion criteria were age ≥65 years old and undergoing CAB and/or valve operation that required cardiopulmonary bypass. Exclusion criteria were baseline delirium, Mini Mental State Examination score <23, inability to speak/read English, severe hearing impairment, inability to tolerate a tourniquet, hemoglobinopathy, or intraoperative ketamine. 50 patients were included from this trial.

Data from the two studies was merged based on common definitions of data elements. Data on the combined group of patients has been published separately, in a parallel manuscript examining the association of frailty and postoperative delirium/cognition.10 Data from the first trial has been published in manuscripts examining the associations of delirium and cognition11 and the effects of an intervention to optimize mean arterial pressure.12

Preoperative Assessment

Baseline frailty assessments were performed using the validated scale from Fried et al.7 evaluating 5 domains: (1) shrinking, defined as unintentional weight loss of ≥10 pounds in the last year; (2) weakness, determined by grip-strength, adjusted for gender and BMI; (3) exhaustion, determined by two questions from the modified 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression scale;13 (4) low physical activity, determined by the modified Minnesota Leisure Time Activities Questionnaire;14 and (5) slowed walking speed, as measured at normal pace over 15 feet. Each of the five domains yielded a score of 0 or 1 based on cutoffs previously described. 12 patients who refused to walk were scored as “1” for gait speed. Frail patients were defined as total scores 3–5.7

Outcome Assessment

At baseline and 1-month follow-up, patients completed the Older Americans Resources and Services Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) questionnaire.15 Baseline and discharge location were obtained from the medical record; discharge location was categorized as discharge to home, including to hotel or with family, or discharge to a non-home location, including sub-acute or acute rehabilitation. Duration of hospitalization and incidence of postoperative complications (atrial fibrillation, new dialysis, new intra-aortic balloon pump, inotropic drugs>24 hours, mechanical ventilation>48 hours, sepsis, stroke) was obtained from the medical record. Delirium was assessed on 3 of the first 4 days using the Confusion Assessment Method16 and Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU17 (intubated patients). For days on which patients were not assessed in person, a validated chart review was used (sensitivity 74%, specificity 83%).18

Perioperative Management

In the operating room, general anesthesia was induced with fentanyl, midazolam, and/or propofol and was maintained with isoflurane and a non-depolarizing muscle relaxant. In the Intensive Care Unit (ICU), patients were generally sedated with propofol until readiness for tracheal extubation, with a protocolized goal of extubation within 6 hours.. For patients in whom extubation was anticipated to be delayed (>48–72 hours), fentanyl and/or midazolam infusions were considered. Mean arterial pressure targets in the ICU were 65–90 mm Hg depending on the procedure and surgeon. Inotropes were weaned based on estimates of adequate perfusion, including physical exam, hemodynamic variables, and laboratory values. Early mobilization was emphasized, with a goal of ambulating by postoperative day 2.

Statistical Analysis

The primary exposure was frailty (defined as a binary variable [frail vs. not-frail]), as assessed by the Fried criteria.7 The primary outcome was functional decline (defined as IADL decline of ≥2 points). A cutoff of 2 points for functional decline was chosen based on surveys of geriatricians indicating clinically significance19 and based on similar definitions in other studies of functional decline after cardiac surgery.20 Secondary outcomes were absolute decline in IADL score, discharge location (home vs. non-home), and duration of hospitalization. For all analyses, a p-value<0.05 was considered significant. However, all analyses using secondary outcomes should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating. No patients with baseline frailty assessments died in the hospital. Baseline patient characteristics were compared using Student t-tests, Wilcoxon rank sum tests, and Fisher’s exact tests in order to assess potentially confounding variables.

For analyses examining the association of frailty and postoperative outcomes, the primary outcome was functional decline (IADL decline ≥2 points). The associations of frailty and both functional decline and discharge location were examined using logistic regression. The association of frailty and absolute decline in IADL score was examined using linear regression with nonparametric bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals, a method chosen because the distribution of the outcome was not normal, with a relatively small sample size. Generalized linear models with a Poisson distribution were used to examine the association of frailty and duration of hospitalization. The fit of the Poisson distribution was assessed using a comparison of residual deviance with degrees of freedom. Variables for which to adjust were considered a priori before analysis (based on review of the literature and potential associations with frailty and functional status) and included age, gender, race, and logistic EuroSCORE. Of note, the logistic EuroSCORE includes several variables, which were thought to differ by frailty status, such as age, comorbidities, and surgical characteristics. The association of individual components of the frailty score with each outcome were examined in unadjusted and adjusted regression models, with each individual component incorporated into separate models.

As a post-hoc analysis, to minimize selection bias in our observational study, we used an inverse probabilities of treatment weight (IPTW) propensity score method.21 Propensity scores (PS) were calculated by generating a logistic regression model to predict the probability of each patient with observed frailty status at baseline based on the following variables, which were chosen based on review of the literature for potential association with frailty and/or functional decline: age, gender, race, education, prior stroke, hypertension, heart failure, vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tobacco use, diabetes, logEuroSCORE, surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, delirium, and baseline IADL score. IPTW were created by using 1/PS. A range of propensity score distributions was considered. To address the extreme values of the IPTW, truncation was performed using percentile cutpoints—with weights >95th percentile and <5th percentile set equal to the 95th and 5th percentiles respectively. Finally, weighted models to estimate the effect of frailty on outcomes were performed with truncated IPTW as the weights. As a sensitivity analysis to examine potential overfitting of the logistic regression model, we generated separate PS using only variables associated with frailty in univariate analysis (p-value<0.20). Nine variables were identified: age, gender, race, education, hypertension, heart failure, Diabetics, logEuroSCORE, and baseline IADL. These PS were used for separate weighted IPTW models, with similar methodology as described above.

We also examined the modifying effect of delirium by testing the significance of an interaction term in adjusted regression models that examined the association of frailty with functional decline, change in absolute IADL score, discharge location, and duration of hospitalization.

A potential mediating effect of postoperative complications was examined using path analysis in MPlus. Here, the “total” association (“effect”) of frailty with outcomes is decomposed into a direct effect on outcomes, independent of complications, and an “indirect” effect in which frailty is associated with complications which in turn are associated with outcomes. In order to evaluate the indirect effect more fully, the components of the indirect effect were examined individually, i.e. the association of the exposure (frailty) with the mediator (complications) and the associations of the mediator (complications) with each outcome. A probit link was specified in the models with binary mediators or outcomes. This link conceptualizes binary data as a dichotomized version of an underlying standard normal random variable. Path coefficients in this framework are interpreted in the same way as linear regression coefficients, either literally (for continuous outcomes) or with respect to the normal variable underlying the binary dichotomization of it. Mediation was adjudicated based on the size and significance of the indirect effect and the significance of the exposure/complication and complication/outcome relationships. In interpreting the indirect effect, we also examined whether there were exposure-mediator interactions, by examining the interaction of frailty and complications in separate models with each outcome.

The sample size for this nested cohort study was determined by the number of patients with available frailty and outcome assessments. We did determine that a sample size of 133 patients would provide a power of 0.76 to detect a difference in an IADL decline of ≥2 at a significance level of 0.05, assuming a frailty prevalence of 33%, and a decline in IADL of 25% in non-frail patients and 50% in frail patients.20

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Data were available on 133 patients with baseline frailty measurement. A flow diagram is shown in Appendix A. Compared to patients in the trial examining remote ischemic preconditioning, patients in the trial examining cerebral autoregulation were younger (70.7±8.0 y/o vs. 74.2± 6.1 y/o), were more likely to be male (81% vs. 60%), and had similar median logEuroSCORE (4.51 [IQR 2.27, 9.26] vs. 4.22 [IQR 2.71, 7.68]). The overall prevalence of frailty at baseline was 33% (44/133). Characteristics of patients by frailty status are presented in Table 1. Frail patients had significantly higher logEuroSCORE, compared with non-frail patients. Frail patients had a higher incidence of a composite score of postoperative complications compared to non-frail patients (52% [23/44] vs. 30% [27/89] p=0.01), as shown in Table 2, and this difference was significant in a model adjusted for age, logistic EuroSCORE, and bypass time (OR 2.38; 95%CI 1.11, 5.11; p=0.027).

Table 1:

Patient and Surgical Characteristics

| Non-Frail N=89 | Frail N=44 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.3 (7.1) | 73.5 (8.1) | 0.117 |

| Male, n (%) | 69 (78) | 28 (64) | 0.090 |

| Race, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 75 (84) | 35 (80) | 0.195 |

| African-American | 8 (9) | 8 (18) | |

| Other | 6 (7) | 1 (2) | |

| Education, n (%) | 0.181 | ||

| High school or below | 31 (36) | 21 (48) | |

| Above high school | 56 (64) | 23 (52) | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | |||

| Prior stroke | 12 (14) | 7 (16) | 0.707 |

| Hypertension | 84 (94) | 38 (86) | 0.114 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 13 (15) | 12 (27) | 0.079 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 11 (12) | 9 (20) | 0.219 |

| COPD | 5(6) | 2 (5) | 0.739 |

| Tobacco (prior) | 45 (63) | 24 (63) | 0.946 |

| Diabetes | 30 (34) | 22 (50) | 0.070 |

| Logistic EuroSCORE, median (IQR) | 3.35 (2.17, 6.66) | 6.29 (3.29, 9.47) | 0.003 |

| Surgery, n (%) | 0.873 | ||

| CAB | 26 (48) | 18 (41) | |

| CAB +Valve | 7 (13) | 8 (18) | |

| Valve | 19 (35) | 17 (39) | |

| Other | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Cardiopulmonary bypass duration (min), median (IQR) | 117 (84, 154) | 128 (80, 154) | 0.669 |

| Incident Delirium | 37 (42%) | 19 (48%) | 0.56 |

Abbreviations: SD= standard deviation; IQR=Inter-Quartile Range; COPD= chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CAB=coronary artery bypass

Table 2:

Postoperative Complications

| Non-Frail N=89 | Frail N=44 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 17 (19.1) | 13 (29.6) | 0.18a |

| Incident dialysis, n (%) | 0 | 0 | N/A |

| New intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 4 (4.5) | 5 (11.4) | 0.16b |

| Mechanical ventilation>48 hours, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 3 (6.8) | 0.11b |

| Multiple inotropic drugs>24 hours, n (%) | 1 (1.1) | 2 (4.6) | 0.25b |

| Single inotropic drug>24 hours, n (%) | 7 (7.9) | 6 (13.6) | 0.29a |

| Sepsis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (2.3) | 0.33b |

| Stroke, n (%) | 2 (2.3) | 4 (9.1) | 0.09b |

| Compositec, n (%) | 27 (30.3) | 23 (52.3) | 0.014a |

Abbreviations: SD= standard deviation; IQR=Inter-Quartile Range

Chi-squared test,

Fisher Exact test,

Composite was defined as any complication listed in Table 2.

Functional Decline in IADL at 1-Month (Primary Outcome)

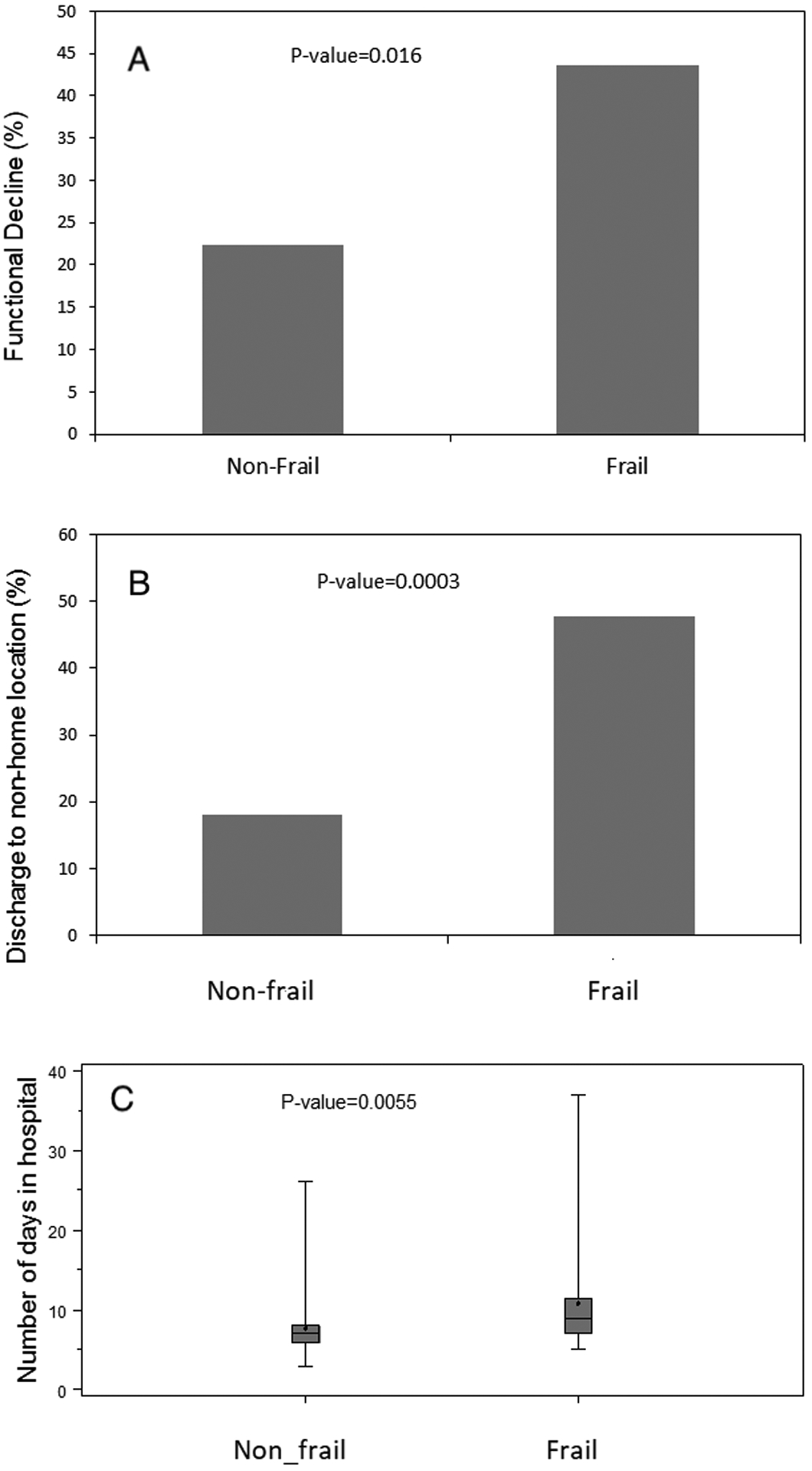

Of the 133 patients in the study sample, IADL data was missing in 6 patients at baseline and in an additional 3 patients at 1-month after discharge. Thus, 1-month IADL data was available in 98% (124/127) of patients with baseline IADL data. At baseline, the median IADL score (out of 14 points total) was 14 (IQR 13, 14) in frail patients and 14 (IQR 14, 14) in non-frail patients. 91% of patients had a baseline IADL score of 13 or 14. At the 1-month follow-up, functional decline in IADL score (≥2-point decline; primary outcome) occurred in 29% (36/124) of patients overall. Among frail patients, functional decline occurred in 44% (17/39), while in non-frail patients, functional decline occurred in 22% (19/85). (Figure 1A) The odds of functional decline in IADL score from baseline to 1 month were higher for frail patients compared to non-frail patients in a model adjusted for age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE (OR 2.41; 95%CI 1.03, 5.63; p=0.04) and in a propensity-score adjusted model (OR 2.32; 95%CI 1.27, 4.32; p=0.006). In a sensitivity analysis that included the baseline IADL score as a covariate in addition to age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE, the inferences were similar (OR 2.45, 95%CI 1.03–5.81, p=0.04)

Figure 1:

(A) Functional decline (defined as decrease in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score ≥2), (B) discharge to non-home location, and (C) number of days in hospital (C) by frailty status. P-values are unadjusted comparisons.

The change in IADL score from baseline to 1-month (n=124) in frail patients was a median change (i.e. decline) of −1 (IQR −3,0) while in non-frail patients was a median change of 0 (IQR −1, 0 p=0.018). The decline in absolute IADL score (secondary outcome) in 124 patients with baseline and 1-month data was greater in frail compared to non-frail patients in a model adjusted for age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE (−1.48; 95%CI −2.77, −0.30; p=0.019) and in a propensity-score adjusted model (−1.04; 95%CI −2.0, −0.07; p=0.035), (Table 3). In a sensitivity analysis using 1-month IADL as the outcome with adjustment for baseline IADL score, age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE, frail patients had lower 1-month IADL scores compared with non-frail patients (−1.53, 95%CI −2.57, −0.49, p=0.004)

Table 3.

Odds of Functional Decline in IADLs, Change in IADL Score, Odds of Discharge to a Non-Home Location, and Increasing Number of Days in Hospital, for Frail Patients Compared with Non-Frail Patients

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | Propensity-Score Adjustedb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate (95%CI) | P-value | Estimate (95%CI) | P-value | Estimate (95%CI) | P-value | |

| Odds Ratio of Functional Decline (≥2) in IADL Score from Baseline to 1-Monthc | ||||||

| Non-frail | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Frail | 2.7 (1.2, 6.1) | 0.02 | 2.4 (1.03, 5.6) | 0.04 | 2.3 (1.3, 4.3) | 0.006 |

| Change in IADL Score from Baseline to 1-Month | ||||||

| Non-frail | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Frail | −1.5 (−2.7, −0.4) | 0.01 | −1.5 (−2.8, −0.3) | 0.02 | −1.0 (−2.0, −0.07) | 0.04 |

| Odds Ratio of Discharge to New Non-Home Locationd | ||||||

| Non-frail | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Frail | 4.2 (1.9, 9.3) | 0.0005 | 3.3 (1.4, 7.7) | 0.007 | 2.5 (1.4, 4.5) | 0.002 |

| Increasing Number of Days in Hospitale | ||||||

| Non-frail | Ref | Ref | Ref | |||

| Frail | 1.4 (1.3, 1.6) | <0.0001 | 1.4 (1.2, 1.5) | <0.0001 | 1.3 (1.1, 1.5) | <0.001 |

Abbreviations: IADL=Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

Adjusted by age, gender, race and LogEuroSCORE

We used an inverse probabilities of treatment weight (IPTW) propensity score method. Propensity scores(PS) were calculated by generating a logistic regression model to predict the probability of each patient with observed frailty status at baseline based on the following variables, which were chosen based on review of the literature for potential association with frailty and/or functional decline: age, gender, race, education, prior stroke, hypertension, congestive heart failure, peripheral vascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, tobacco use, diabetes, logistic EuroSCORE, surgery, cardiopulmonary bypass, delirium, and baseline IADL score. IPTW were created by using 1/PS. A range of propensity score distributions was considered. To address the extreme values of the IPTW, truncation was performed using the percentile cutpoints—all weights with value above the 95th percentile were set equal to the 95th percentile and all weights with value below the 5th percentile were set equal to the 5th percentile. Finally, weighted models to estimate the effect of frailty on outcomes were performed with truncated IPTW as the weights.

Estimate refers to the odds ratio of functional decline in IADL score in frail patients compared with non-frail patients

Estimate refers to the odds ratio of discharge to a new non-home location in frail patients compared with non-frail patients

Estimate refers to the estimated increasing number of days in the hospital for frail patients compared with non-frail patients

Discharge Location (Secondary Exploratory Outcome)

Discharge location was a secondary exploratory outcome. The overall incidence of discharge to a new non-home location was 28% (37/133). The incidence of non-home discharge in frail patients was 48% (21/44) and in non-frail patients was 18% (16/89) (Figure 1B). As shown in Table 3, the odds of being discharged to a non-home location were 3.25-fold higher (95%CI 1.37, 7.69; p=0.007) for frail patients compared to non-frail patients, adjusted for age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE, with similar inferences in a propensity-score adjusted model.

Duration of Hospitalization (Secondary Exploratory Outcome)

Duration of hospitalization was a secondary exploratory outcome. The median number of days in the hospital after surgery for frail patients was 9 (IQR 7, 11.5), while for non-frail patients was 7 (IQR 6, 8; p<0.001) (Figure 1C). As shown in Table 3, the duration of hospitalization in frail patients was estimated to be 1.35 days longer (95%CI 1.19, 1.52; p<0.0001) for frail patients compared to non-frail patients, adjusted for age, gender, race, and logEuroSCORE, and 1.29 days longer (95%CI 1.12, 1.50; p<0.001) in a propensity-score adjusted model.

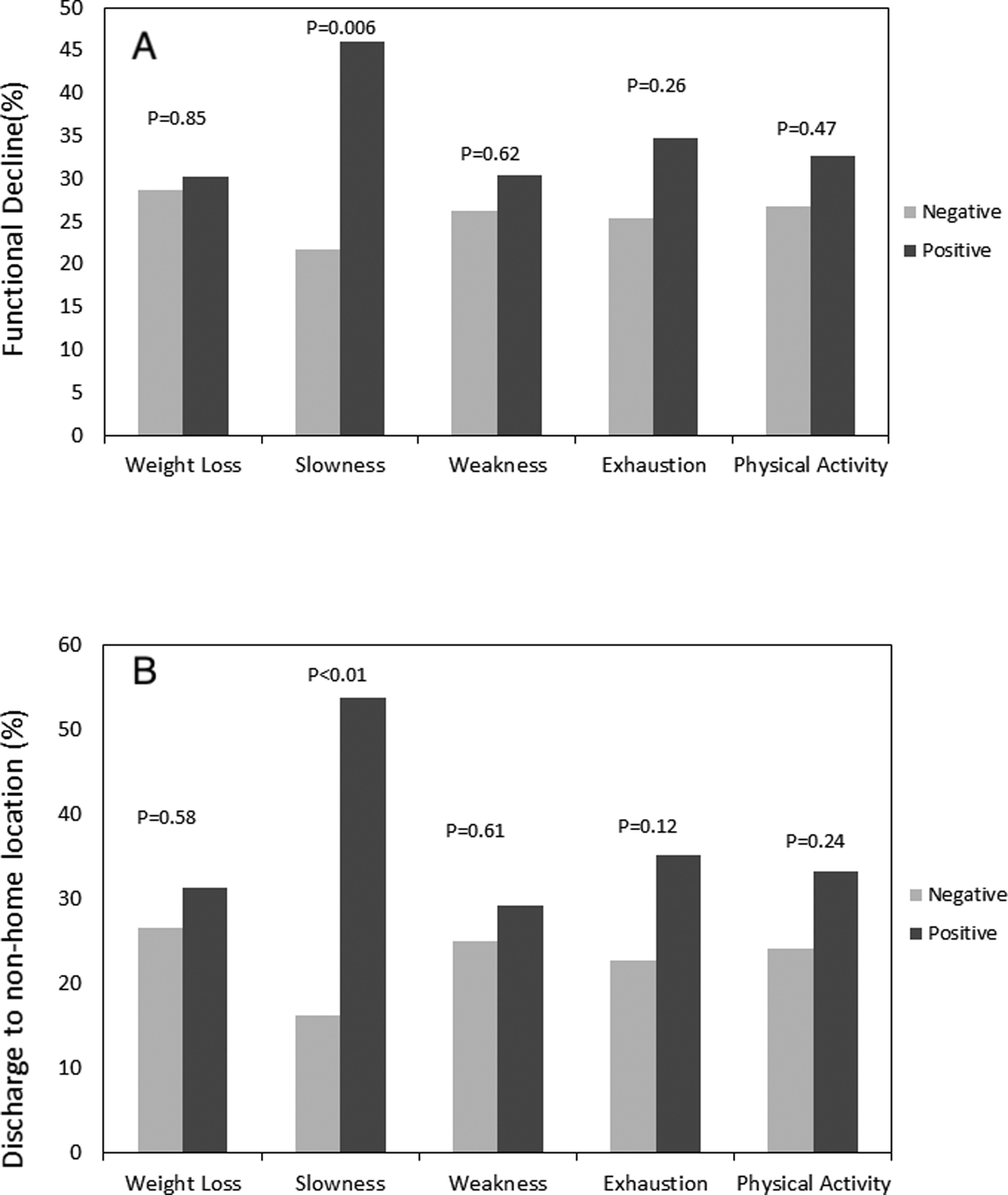

Individual Components of the Frailty Score (Secondary Exploratory Analyses)

Functional decline and discharge to a non-home location based on each individual component of the frailty phenotype are shown in Figure 2, with slow gait speed being significantly associated with both of these outcomes. In adjusted models in which each item on the frailty score was assessed in separate models, slow gait speed was associated with functional decline (OR 2.72, 95%CI 1.14, 6.49, p=0.03), absolute IADL decline (β-coefficient −2.12, 95%CI −3.14, −1.09, p<0.001), discharge to a non-home location (OR 4.23, 95%CI 1.72, 10.38, p=0.002), and number of days in the hospital (β-coefficient 1.42, 95%CI 1.25, 1.61, p<0.001). Additionally, weight loss (β-coefficient 1.19, 95%CI 1.04, 1.36, p=0.01), weakness (β-coefficient 1.28, 95%CI 1.12, 1.46, p<0.001), and exhaustion (β-coefficient 1.15, 95%CI 1.02, 1.30, p=0.02) were all individually associated with increasing number of days in the hospital in separate models. All other associations between individual components of the frailty phenotype and functional outcomes were not significant.

Figure 2:

(A) Functional decline (defined as decrease in Instrumental Activities of Daily Living score ≥2), and (B) discharge to non-home location according to individual components of the frailty phenotype. “Positive” refers to exceeding the cutoff threshold to be considered frail for that particular criterion. P-values are unadjusted comparisons.

Delirium as a Potentially Modifying Factor of the Association between Frailty and Outcomes

Delirium assessments were available on 128 patients (4 missing due to staff availability and 1 missing due to excessive sedation). The association of frailty and 1-month absolute decline in IADL score was significantly different by delirium status (p-interaction 0.03). For patients with delirium, frail patients had a greater decline in 1-month IADL score compared to non-frail patients (−2.2, 95%CI −4.0, −0.4, p=0.02), while for patients without delirium the difference in functional decline for frail compared to non-frail patients was less (−0.12, 95%CI −1.0, 0.78, p=0.79). Delirium did not modify the association of frailty with 1-month functional decline, duration of hospitalization, or discharge location.

Postoperative Complications as Mediating Factors

A potential mediating effect of postoperative complications was examined, with the hypothesis that complications would mediate the association of frailty with functional status and hospital outcomes. In these models, the total effect is interpreted as the effect of frailty on the propensity of each individual functional outcome, without considering mediation. The size and significance of the indirect effect reflects the amount of mediation. Complications did not mediate the association between frailty and functional IADL decline (total effect 0.53, standard error [SE] 0.26, p=0.02, indirect effect −0.05, SE 0.09, p=0.60) or between frailty and discharge location (total effect 0.69, SE 0.27, p=0.01, indirect effect 0.14, SE 0.10, p=0.16). However, complications did partially mediate the association of frailty and hospital duration ≥10 days (total effect 0.77, SE 0.25, p=0.002, indirect effect 0.30, SE 0.15, p=0.043). In this model, the association of frailty and complications was 0.54 (SE 0.24, p=0.026), and the association of complications and hospital duration ≥10 days was 0.56, (SE 0.12, p<0.001). There was no interaction (p=0.45) between frailty and complications in a model with hospital duration ≥10 days as the outcome.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that frail patients were at increased risk of functional decline at 1-month after surgery. In exploratory analyses, we found that frail patients were at increased risk for discharge to a new non-home location and increased duration of hospitalization compared to non-frail patients. Delirium modified the association of frailty and change in IADL score at 1-month. Postoperative complications partially mediated the association of frailty and duration of hospitalization ≥10 days.

Frailty has been conceptualized as an inability to withstand stress, and multiple studies have found that frailty is a predictor of morbidity and mortality following cardiac surgery.3 The results of our study were concordant, with more complications after surgery occurring in the frail. In particular, frailty has been an important focus in the aortic valve replacement population, with the goal of stratifying patients into appropriate candidates for surgical or transcatheter aortic valve replacement, or even non-operative medical therapy. Yet there is a paucity of data describing the relationship between frailty and function after conventional cardiac surgery, even though preservation of functional status is a key patient-centered goal.5

In open surgery, the association between frailty and functional decline has not been consistent,22,23 with two systematic reviews finding few well-done studies and advocating for more research focusing on functional outcomes.5,6 One recent study found that frailty was associated with worse functional trajectories after cardiac surgery, but the frailty measure was based on an index of comorbidities.24 A second well-done multi-center study reported that frailty, as assessed by a number of measures, was associated with a composite of 1-year mortality and disability.25 In this study, the Essential Frailty Toolset (a composite measure of chair stands, cognition, anemia, and albumin) performed the best for prediction of death and disability at 1-year in comparison to six other frailty scales. However, intermediate functional status that may be important for recovery was not reported, nor was the contribution of complications or delirium. It is noteworthy that delirium modified the association of frailty and 1-month functional change in our study and highlights the negative synergy between these two geriatric syndromes. With regards to discharge location, Lee et al.26 did find in >3800 cardiac surgical patients that frailty was associated with new institutional discharge, but the frailty prevalence was only 4%, and the frailty definition was unique to this study. In the transcather aortic procedure, frailty does appear to be associated with functional decline at 6-months or later.27,28

A recent systematic review6 highlighted an important role for single-component frailty instruments, and iIn our study, it is noteworthy that individual domains of the Fried frailty assessment differed with respect to outcomes. Specifically, slowed walking speed was the only domain that was consistently associated with both decline in IADLs and discharge to a non-home location. These results support the measurement of at least gait speed for risk-stratification in busy preoperative clinics, and potentially support change in gait speed as a surrogate outcome for prehabilitation programs. These results may be particularly informative given the myriad of frailty scales that can be used.29

Identification of modifiable risk factors for functional decline may allow for targeted strategies based on the underlying biology of frailty. For instance, frail patients (especially those with delirium or at high risk for delirium) might benefit from enhanced physical therapy, early consideration of discharge planning, or even from prehabilitation programs prior to surgery.30 In contrast, frailty assessments that are based on an index of various comorbidities may not be as amenable to targeted interventions. In this study, delirium did modify the association of frailty with change in IADL score and thus appears to interact with frailty. However, frailty was not associated with delirium as in other studies, in large part since pre-frailty was not considered as a separate exposure.31 Although frail patients were at increased risk for postoperative complications, complications did not mediate the relationship between frailty and either decline in IADL or discharge location, although complications did the mediate the relationship with prolonged hospitalization.

There are several strengths of this study. Frailty was assessed using the well-validated Fried scale by an experienced team. Functional outcomes were measured prospectively and reflect important patient-related outcomes. Analyses were adjusted for important confounding variables and included a propensity score analysis. There are several limitations. Although the frailty and outcome assessments were similar, these results reflect a combination of two studies, with different enrollment criteria and goals. The Fried frailty scale is thought to reflect a biologic phenotype of frailty, but can be time-consuming to implement. Other measures of frailty, such as the frailty index or many single-item measures, were not examined. Thus, it is unclear whether these results would be similar using other conceptualizations of frailty, especially since different frailty scales measure different underlying biology. The primary functional outcomes were assessed at 1-month, but functional status at later time-points (i.e. 3–12 months) may better reflect recovery. These longer-term outcomes would be particularly important to parse out what aspects of frailty are driven by cardiac comorbidities in comparison to traits such as sarcopenia. There is a possibility of residual confounding given baseline differences in comorbidity by frailty status, even though we adjusted for several variables that were determined a priori. Finally, these results reflect patients only at one academic medical center with important exclusion criteria that may limit generalizability.

In conclusion, frail patients undergoing cardiac surgery were at higher risk of functional decline at 1-month after surgery. Further research is needed to determine how to incorporate frailty assessment into perioperative management to optimize functional status early after cardiac surgery.

Supplementary Material

KEY POINTS.

Question:

Are functional outcomes worse among frail patients undergoing cardiac surgery compared with non-frail patients?

Findings:

In adjusted models, frail patients had greater functional decline at 1-month after cardiac surgery.

Meaning:

Frailty may identify patients at risk of functional decline at 1-month after cardiac surgery, and therefore perioperative strategies to optimize frail cardiac surgery patients are needed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES

The authors are grateful for the support of the Johns Hopkins Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care Medicine Clinical Research Core (Michelle Parish RN, Elizabeth White RN, Mirinda Anderson RN), and Laura Max PA for study conduct and regulatory support.

Funding

NIH K76 AG057020 (CB)

OAIC Research Career Development Core Award (P30 AG021334)

Magic That Matters Grant (CB)

NIH RO1 HL092259 (CH)

GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- IADL

Instrumental Activities of Daily Living

- EuroSCORE

European Score for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation

- CAB

Coronary Artery Bypass

- ICU

Intensive Care Unit

- SD

Standard Deviation

- IQR

Inter-quartile Range

- IPTW

Inverse Probability of Treatment

- PS

Propensity Score

Footnotes

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

CB has consulted for and received grant funding from Medtronic

CH is a consultant and provides lectures for Medtronic/Covidien, Inc (Boulder, CO). CH is a consultant to Merck, Inc (Kenilworth, NJ)

RELATED PUBLICATIONS

Data on these patients has been published separately, in manuscripts examining the associations of delirium and frailty with cognitive change after cardiac surgery and examining an intervention to target mean arterial pressure using cerebral autoregulation monitoring.

Contributor Information

Jing Tian, Department of Biostatistics, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore MD 21287.

Atsushi Yamaguchi, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University, Saitama, Japan 330-8503.

Jeremy Walston, Department of Geriatrics and Gerontology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore MD, 21287.

Rani Hasan, Department of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore MD 21287.

Kaushik Mandal, Department of Surgery; Division of Cardiac Surgery, Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, 500 University Drive, PO Box 850, Hershey PA 17033.

Stefano Schena, Department of Surgery; Division of Cardiac Surgery, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore MD 21287.

Charles W. Hogue, Department of Anesthesiology, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, Chicago IL, 60611.

Charles H. Brown, IV, Department of Anesthesiology & Critical Care Medicine, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Baltimore, MD 21287.

REFERENCES

- 1.Walston J, Hadley EC, Ferrucci L, et al. Research agenda for frailty in older adults: Toward a better understanding of physiology and etiology: Summary from the american geriatrics society/national institute on aging research conference on frailty in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(6):991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Graham A, Brown CH. Frailty, aging, and cardiovascular surgery. Anesth Analg. 2017;124(4):1053–1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sundermann S, Dademasch A, Rastan A, et al. One-year follow-up of patients undergoing elective cardiac surgery assessed with the comprehensive assessment of frailty test and its simplified form. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2011;13(2):119–23; discussion 123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sundermann SH, Dademasch A, Seifert B, et al. Frailty is a predictor of short- and mid-term mortality after elective cardiac surgery independently of age. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2014;18(5):580–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin HS, Watts JN, Peel NM, Hubbard RE. Frailty and post-operative outcomes in older surgical patients: A systematic review. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16(1):157–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim DH, Kim CA, Placide S, Lipsitz LA, Marcantonio ER. Preoperative frailty assessment and outcomes at 6 months or later in older adults undergoing cardiac surgical procedures: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(9):650–660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: Evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stammers AN, Kehler DS, Afilalo J, et al. Protocol for the PREHAB study-pre-operative rehabilitation for reduction of hospitalization after coronary bypass and valvular surgery: A randomised controlled trial. BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e007250–007250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McKhann GM, Grega MA, Borowicz LM Jr, et al. Encephalopathy and stroke after coronary artery bypass grafting: Incidence, consequences, and prediction. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(9):1422–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nomura Y, Nakano M, Bush B, et al. Observational study examining the association of baseline frailty and postcardiac surgery delirium and cognitive change. Anesth Analg. 2019; 129: 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CH 4th, Probert J, Healy R, et al. Cognitive decline after delirium in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;129: 406–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown CH, Neufeld KJ, Tian J, et al. Effect of targeting mean arterial pressure during cardiopulmonary bypass by monitoring cerebral autoregulation on postsurgical delirium among older patients: A nested randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2019. (epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Orme JG, Reis J, Herz EJ. Factorial and discriminant validity of the center for epidemiological studies depression (CES-D) scale. J Clin Psychol. 1986;42(1):28–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor HL, Jacobs DR, Schucker B, Knudsen J, Leon AS, Debacker G. A questionnaire for the assessment of leisure time physical activities. J Chronic Dis. 1978;31(12):741–755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Multidimensional functional assessment: The OARS methodology. A manual 2nd ed. Durham NC: Duke University Center for the Study of Aging and Human Development; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inouye SK, van Dyck CH, Alessi CA, Balkin S, Siegal AP, Horwitz RI. Clarifying confusion: The confusion assessment method. A new method for detection of delirium. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(12):941–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ely EW, Margolin R, Francis J, et al. Evaluation of delirium in critically ill patients: Validation of the confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit (CAM-ICU). Crit Care Med. 2001;29(7):1370–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inouye SK, Leo-Summers L, Zhang Y, Bogardus ST Jr, Leslie DL, Agostini JV. A chart-based method for identification of delirium: Validation compared with interviewer ratings using the confusion assessment method. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(2):312–318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdulaziz KE, Brehaut J, Taljaard M, et al. National survey of family physicians to define functional decline in elderly patients with minor trauma. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):117–1. −1 [doi]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudolph JL, Inouye SK, Jones RN, et al. Delirium: An independent predictor of functional decline after cardiac surgery. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(4):643–649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurth T, Walker AM, Glynn RJ, et al. Results of multivariable logistic regression, propensity matching, propensity adjustment, and propensity-based weighting under conditions of nonuniform effect. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(3):262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partridge JS, Fuller M, Harari D, Taylor PR, Martin FC, Dhesi JK. Frailty and poor functional status are common in arterial vascular surgical patients and affect postoperative outcomes. Int J Surg. 2015;18:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ronning B, Wyller TB, Jordhoy MS, et al. Frailty indicators and functional status in older patients after colorectal cancer surgery. J Geriatr Oncol. 2014;5(1):26–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim DH, Afilalo J, Shi SM, et al. Evaluation of changes in functional status in the year after aortic valve replacement. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(3):383–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Afilalo J, Lauck S, Kim DH, et al. Frailty in older adults undergoing aortic valve replacement: The FRAILTY-AVR study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(6):689–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee DH, Buth KJ, Martin BJ, Yip AM, Hirsch GM. Frail patients are at increased risk for mortality and prolonged institutional care after cardiac surgery. Circulation. 2010;121(8):973–978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schoenenberger AW, Stortecky S, Neumann S, et al. Predictors of functional decline in elderly patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI). Eur Heart J. 2013;34(9):684–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Green P, Arnold SV, Cohen DJ, et al. Relation of frailty to outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement (from the PARTNER trial). Am J Cardiol. 2015;116(2):264–269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith CR. Frailty is to predictive as jello is to wall. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;156(1):177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arora RC, Brown CH, Sanjanwala RM, McKelvie R. “NEW” prehabilitation: A 3-way approach to improve postoperative survival and health-related quality of life in cardiac surgery patients. Can J Cardiol. 2018;34(7):839–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nomura Y, Nakano M, Bush B, et al. Observational study examining the association of baseline frailty and postcardiac surgery delirium and cognitive change. Anesth Analg. 2019; 129: 507–514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.