Abstract

Objective

In this observational study, we explored cortical structure as function of cortical depth through a laminar analysis of the T1/T2-weighted (T1w/T2w) ratio, which has been related to dendrite density in ex vivo brain tissue specimens of patients with MS.

Methods

In 39 patients (22 relapsing-remitting, 13 female, age 41.1 ± 10.6 years; 17 progressive, 11 female, age 54.1 ± 9.9 years) and 21 healthy controls (8 female, , age 41.6 ± 10.6 years), we performed a voxel-wise analysis of T1w/T2w ratio maps from high-resolution 7T images from the subpial surface to the gray matter/white matter boundary. Six layers were sampled to ensure accuracy based on mean cortical thickness and image resolution.

Results

At the voxel-wise comparison (p < 0.05, family wise error rate corrected), the whole MS group showed lower T1w/T2w ratio values than controls, both when considering the entire cortex and each individual layer, with peaks occurring in the fusiform, temporo-occipital, and superior and middle frontal cortex. In relapsing-remitting patients, differences in the T1w/T2w ratio were only identified in the subpial layer, with the peak occurring in the fusiform cortex, whereas results obtained in progressive patients mirrored the widespread damage found in the whole group.

Conclusions

Laminar analysis of T1w/T2w ratio mapping confirms the presence of cortical damage in MS and shows a variable expression of intracortical damage according to the disease phenotype. Although in the relapsing-remitting stage, only the subpial layer appears susceptible to damage, in progressive patients, widespread cortical abnormalities can be observed, not only, as described before, with regard to myelin/iron concentration but, possibly, to other microstructural features.

Cortical pathology in MS is characterized by demyelination and neuroaxonal loss associated with cortical thinning.1–3 Along with these well-known features, Jürgens et al. have recently reported, from the analysis of apical dendrites of pyramidal neurons, a reduction in dendrite density with selective spine loss independent of cortical demyelination, occurring alongside a reduction in dendrite branch number more evident in the demyelinated than the normal-appearing cortex.4 In vivo, such dendritic pathology has seemingly been captured by an imaging analysis technique based on the ratio of T1- and T2-weighted (T1w/T2w) signal intensities.5 Specifically, Righart et al.5 have reported a widespread decrease in the T1w/T2w ratio in the cortical gray matter (GM) of patients with MS and have demonstrated that it was related to decreased dendrite density but not to myelin content, axonal density, or cortical thickness in ex vivo brain tissue specimens. Dendrite density reduction could be ascribed to a number of different pathologic mechanisms,4 with some of them (i.e., meningeal inflammation) affecting superficial cortical layers more severely than deeper layers based on anatomic contiguity. To date, although a reduction in the T1w/T2w ratio, possibly indicating dendritic pathology, has been reported in the MS cortex,5 no data are available on the intracortical distribution of such damage that could provide indirect indication on the responsible mechanisms. Against this background, our overarching goal was to characterize, in vivo, the distribution of intracortical pathology in MS as measured by the T1w/T2w ratio. To this aim, after an initial exploration of T1w/T2w ratio values in the normal-appearing cortex and cortical lesions (CLs), we focused on the normal-appearing cortex and performed a laminar analysis of T1w/T2w ratio maps. Exploiting the increased signal-to-noise ratio of submillimetric 7T images, we (1) explored cortical structure as function of cortical depth and hypothesized a predominant involvement of more superficial layers, (2) assessed cortical damage distribution in patients with relapsing and progressive MS (RRMS and PMS), hypothesizing a more widespread involvement in PMS, where the convergence of different mechanisms driving GM damage is known to occur.6

Methods

Participants

From January 2017 to April 2018, 39 patients with MS (22 relapsing-remitting, 10 primary progressive, and 7 secondary progressive) were prospectively enrolled in this observational exploratory study, along with 21 healthy controls (HCs). Inclusion criteria for patients with MS were (1) age between 18 and 70 years; (2) diagnosis of clinically definite MS, according to the revised McDonald criteria7; (3) Expanded Disability Status Scale score ≤7.0 at screening; and (4) if treated, patients had to be on stable treatment for at least 1 year. Sex- and age-matched healthy volunteers were recruited as controls. For all participants, the following exclusion criteria were applied: (1) current or past history of major systemic condition, history of head trauma, diagnosis of psychiatric disorder, or neurologic disorders (other than MS for the patient group); (2) contraindications to MRI; (3) pregnancy; and (4) alcoholism or drug addiction. Patients were recruited through referrals from the treating neurologist, whereas HCs were recruited from the general community through flyers.

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

MRI data acquisition

All participants underwent a brain MRI at 7T (MAGNETOM, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) with a 32-channel head coil. A 3D T1-weighted Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Acquisition of Gradient Echo (MPRAGE) and 3D T2-weighted Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts using different flip angle Evolution (SPACE) images were acquired with the following parameters: (1) T1-weighted MPRAGE sequence: voxel size = 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 mm3; field of view = 224 × 224 mm2; 240 sagittal slices; repetition time/echo time/inversion time = 2,200/2.95/1,050 ms; flip angle = 7°, GeneRalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Acquisition with acceleration factor R = 2 and acquisition time = 6:35 minutes; and (2) T2-weighted SPACE sequence: voxel size = 0.7 × 0.7 × 0.7 mm3; field of view = 224 × 224 mm2; 240 sagittal slices; repetition time/echo time = 3,500/400 ms; GeneRalized Autocalibrating Partial Parallel Acquisition with R = 2 and acquisition time = 7:47 minutes.

Data processing

Cortical lesions

CLs were visually identified on T1-weighted images, by 3 readers in consensus as described in reference 3. Subsequently, CLs were segmented using a semiautomatic approach8–12 (Jim 7, Xinapse Systems xinapse.com/Manual/). Lesion masks were warped into the group template space and averaged to generate a CL probability map. In addition, CL masks were applied to the segmented cortex, and mean T1w/T2w ratio values were obtained from CLs and the normal-appearing cortex.

T1w/T2w ratio map generation

T1w/T2w ratio maps were generated using the Human Connectome Project processing pipeline.13 Briefly, T1w and T2w images were corrected for gradient nonlinearity-induced geometric distortion.14 The T1 images were rigidly registered to the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 space (MNI152) resampled to 0.7 mm isotropic. T2w images were rigidly registered to the T1w image. The T1w and T2w images were corrected for B1− bias and some B1+ bias.15 Finally, T1w/T2w ratio maps were computed by dividing T1w by the T2w signal value.

T1w/T2w ratio across cortical layers

T1w/T2w ratio maps across cortical layers were estimated using the Computational Anatomy Toolbox (CAT12 neuro.uni-jena.de/cat/) combined with NeuroImaginG at High RESolution (Nighres)-Cortical Reconstruction Using Implicit Surface Evolution algorithm (nighres.readthedocs.io/en/latest/cortex/cruise_cortex_extraction.html). Briefly, GM, white matter (WM), and CSF were segmented from T1-weighted images using CAT12. During CAT12 segmentation, single-subject structural data were aligned to the IXI555 template using the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration using Exponentiated Lie algebra normalization.16 Two warping fields were produced by CAT12: the direct warping field that aligns the single-subject structural data to the IXI555 template and the inverse warping field that aligns the IXI555 template to subject structural data. The resulting inverse warping field was then used to transpose the cortical GM from the Neuromorphometrics atlas (Neuromorphometrics, Inc) to the native space. The transposed mask was then applied to GM CAT12 segmentation to isolate cortical GM matter in the subject space. Cortical boundary surfaces were extracted using implicit surface evolution with Nighres-Cortical Reconstruction Using Implicit Surface Evolution.

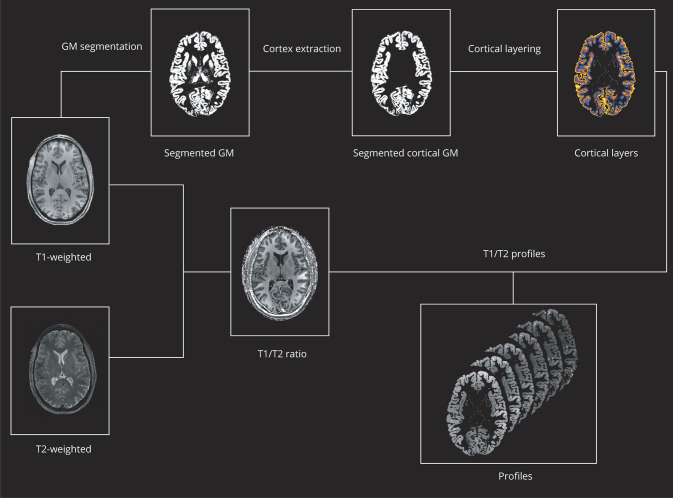

Volume-preserving representations of cortical depth were estimated from T1-weighted images. Briefly, the surfaces between GM and WM were represented in Cartesian space using a level-set framework with N = 5, and traverses were constructed that run from one cortical boundary surface to the other. Sampling T1w/T2w values along these traverses, cortical T1w/T2w ratio profiles were obtained from 6 equivolumetric layers ranging from WM/GM boundary to GM/CSF boundary with Nighres-Volumetric Layering algorithm.17 An equivolume model was adopted for the computation of cortical layers, as it has been proven neuroanatomically more appropriate than other approaches for the reconstruction of cortical anatomy.17 Although in previous studies, the same methodology was applied to images with resolution of 0.7 and 0.5 mm3 obtaining 20 intracortical layers,17,18 we choose a more conservative approach and, considering a mean cortical thickness of 2.5–3 mm and our image resolution of 0.7 isotropic, sampled 6 depth-dependent layers to further ensure accuracy. The main processing steps involved in the generation of the cortical T1w/T2w ratio profiles are shown in figure 1.

Figure 1. Processing pipeline.

Schematic representation of the main processing steps involved in the generation of cortical T1w/T2w ratio profiles. For details about individual steps, see text.

Voxel-wise group analysis

To spatially normalize T1w/T2w ratio maps to get voxel correspondence across all participants for group comparison, a study-specific unbiased GM and WM group template was generated using the Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration using Exponentiated Lie algebra tool16 implemented in SPM12. The resulting deformation fields were used to warp cortical T1w/T2w ratio maps into the group template space. Spatially normalized T1w/T2w ratio maps were smoothed with a Gaussian kernel (8 × 8 × 8 mm) to reduce the intersubject anatomic variability and improve the signal-to-noise ratio before statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed in Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS v25, IBM corp.). Differences in age and sex were assessed using a 2-sample t test and a χ2 test, respectively. Mean T1w/T2w in CLs and the normal-appearing cortex were compared via a paired-sample t test. The mean number of CLs in patients with RRMS and PMS was compared via analysis of covariance, accounting for age and sex.

Voxel-wise general linear model, adjusted for age and sex, was performed using SPM12. Differences in T1w/T2w ratio maps between groups were probed in the normal-appearing cortex at each voxel, defining CLs as set of outlier voxels indicated by NaN (not a number), for the whole cortex and for the 6 layers. Multiple comparisons were corrected with a family-wise error rate using a p value set at <0.05.

Data availability

The data set analyzed in the present study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Results

Study population

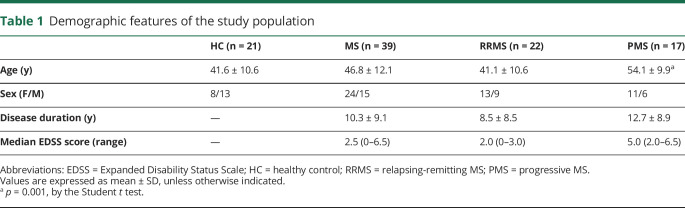

Demographic features of the study population are reported in table 1. A significant age difference was identified between patients with PMS and HCs (t = −3.85; 95% CI [−19.12 to −5.93]; p = 0.001), whereas the remaining demographic variables were not significantly different across groups.

Table 1.

Demographic features of the study population

CLs

Patients with PMS presented a significantly higher number of CLs than patients with RRMS (9.33 ± 13.99 vs 6.12 ± 11.30; F = 7.20; 95% CI [ −26.98 to −3,62]; p = 0.012). The spatial distribution of CLs in the patient group is shown in supplementary figure 1, links.lww.com/NXI/A326.

Mean T1w/T2w in CLs and the normal-appearing cortex

T1w/T2w ratio values were significantly lower in CLs than in the normal-appearing cortex (3.21 ± 0.51 vs 3.80 ± 0.20; t = 7.27; 95% CI [0.42–0.75]; p < 0.0001).

Voxel-based analysis of the normal-appearing cortex

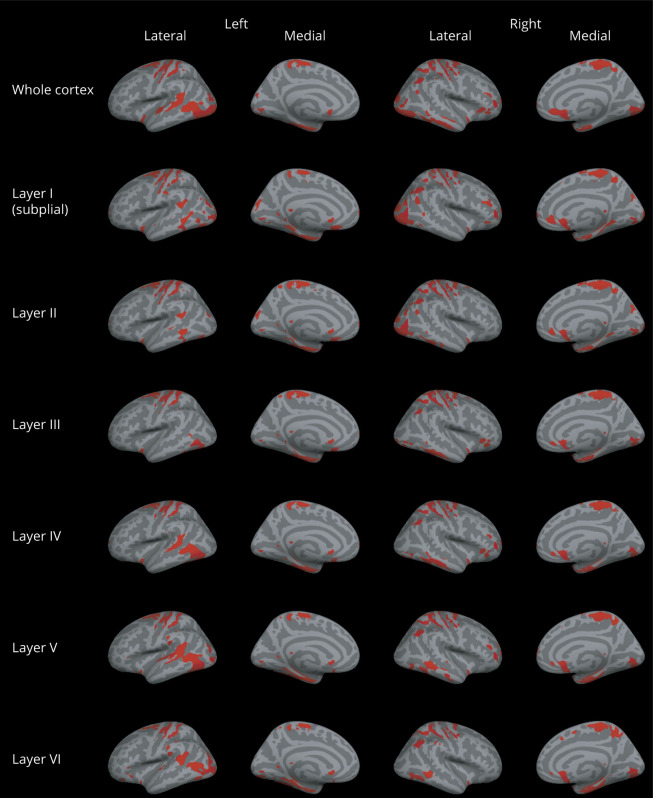

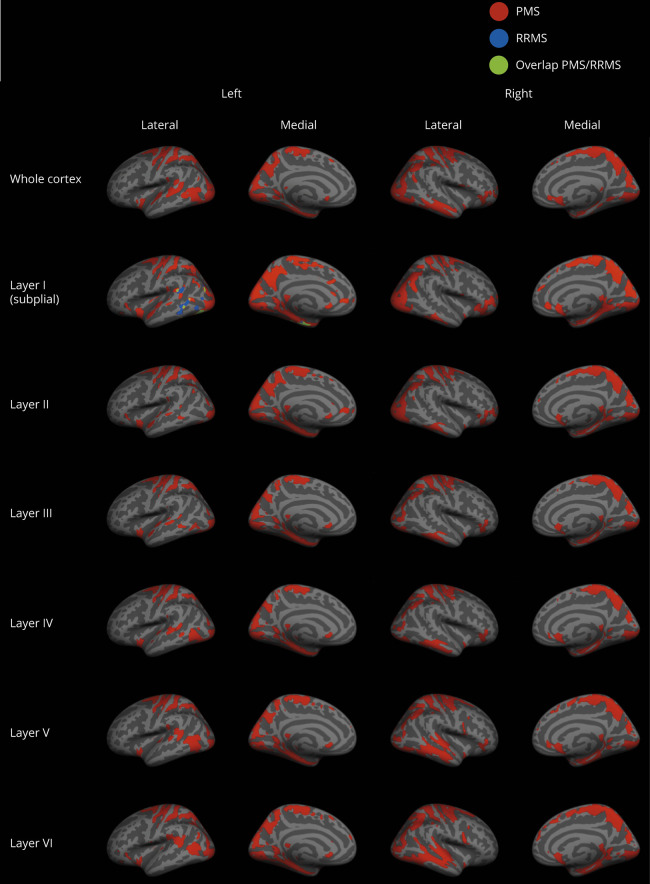

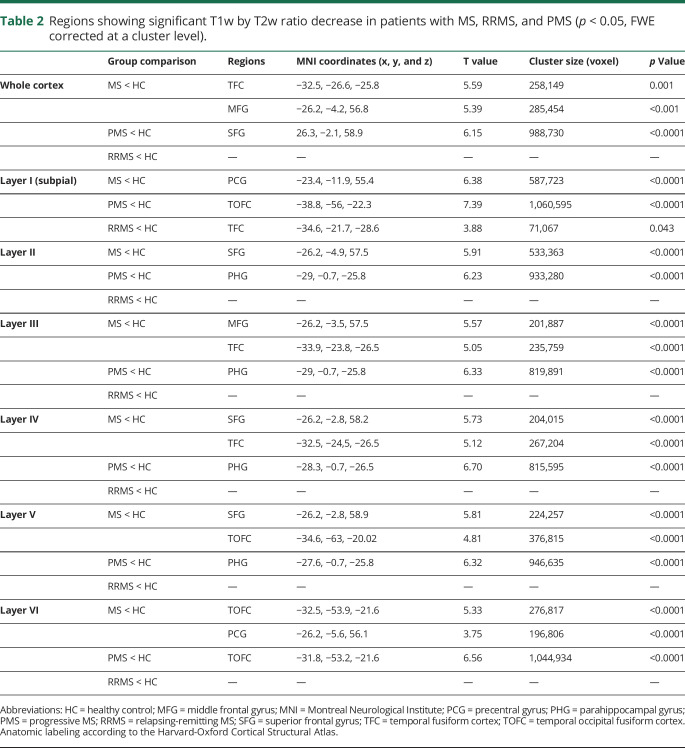

At the voxel-wise comparison, the whole MS group showed significantly lower T1w/T2w ratio values than HC, both when considering the entire cortex and each individual layer, with peaks occurring at the level of the fusiform cortex, temporo-occipital cortex, and superior and middle frontal cortex (figure 2). In comparison with HC, the RRMS subgroup showed significantly lower T1w/T2w ratio values in the subpial layer, with the peak occurring in the fusiform cortex, whereas the PMS subgroup showed a widespread damage, involving all layers and mirroring the results emerged from the comparison of the whole MS group with HC (figure 3). A complete list of the significant clusters emerging from the voxel-based analysis is reported in table 2. Details of the significant cluster overlap between RRMS and PMS are shown in supplementary figure 2, links.lww.com/NXI/A327.

Figure 2. Voxel-wise comparison of the T1w/T2w ratio in patients with MS and controls.

Clusters of significantly lower T1w/T2w ratio in patients with MS compared with healthy controls for the whole cortex and for the 6 cortical layers (p < 0.05, family wise error rate corrected) overlaid onto the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 semi-inflated cortical surfaces.

Figure 3. Voxel-wise comparison of the T1w/T2w ratio in patients with RRMS, patients with PMS, and controls.

Clusters of significantly lower T1w/T2w ratio in patients with PMS and RRMS compared with healthy controls for the whole cortex and for the 6 cortical layers (p < 0.05, family wise error rate corrected) overlaid onto the Montreal Neurological Institute 152 semi-inflated cortical surfaces. PMS = progressive MS; RRMS = relapsing-remitting MS.

Table 2.

Regions showing significant T1w by T2w ratio decrease in patients with MS, RRMS, and PMS (p < 0.05, FWE corrected at a cluster level).

Discussion

The exact pathologic substrate of the T1w/T2w ratio is not completely known. Indeed, although the T1w/T2w ratio is generally considered as a proxy for myelin content, such assumption has been indirectly drawn from the visual comparison of histology-based myelin maps and T1w/T2w ratio maps.15,19–23 More recent findings suggest that the T1w/T2w ratio might rather be capturing variation in caliber and packing density of cortical dendrites and subcortical WM axons,5,24 thus offering the possibility to explore a specific aspect of MS cortical pathology. Our analysis showed lower mean values of the T1w/T2w ratio in CLs than in the normal-appearing cortex. This finding is in agreement with the notion that CLs are sites of highly destructive processes such as demyelination, axonal and dendritic transection, and neuronal apoptosis.25 In addition, this finding is consistent with the histopathologic characterization performed by Jürgens et al., which demonstrated a reduction of dendrite branches in the demyelinated cortex.4 More interestingly, our voxel-wise analysis of the normal-appearing cortex revealed that the cortical damage depicted by the T1w/T2w ratio was not limited to CLs and did not show a homogeneous distribution within the cortex in all MS phenotypes. Considering 6 layers from the subpial surface to the GM/WM boundary, patients with RRMS showed a reduced T1w/T2w ratio only in a relatively small area of the temporal cortex (fusiform gyrus) and only within the subpial layer, whereas patients with PMS showed abnormalities throughout all layers of the temporo-occipital cortex, frontal and limbic areas, with relative sparing of the parietal regions. Such spatial distribution differs from the one, much more widespread, previously reported for the laminar analysis of T2* maps.2 Although no formal correlation has ever been tested between T2* and T1w/T2w ratio, this finding, together with the weak correlation reported between the T1w/T2w ratio and histologically validated myelin markers such as myelin water fraction and magnetization transfer ratio,24,26 seems to suggest that the T1w/T2w ratio could indeed capture a pathologic substrate different from myelin. In the RRMS subgroup, in particular, we identified milder abnormalities in comparison with the ones previously reported.5 One explanation might be that our sample is not large enough to provide sufficient power for the detection of subtle variations in cortical structure with the application of the T1w/T2w ratio. Supporting this hypothesis, a recent study, with the sample size comparable to ours, identified T1w/T2w ratio changes in CLs but not the normal-appearing cortex,27 suggesting that, when structural changes are subtle, the T1w/T2w ratio might not be sensitive enough to capture them. However, regardless of the small sample size, our results in patients with RRMS are in line with the spatial distribution of T1w/T2w ratio abnormalities reported in a larger sample of early MS,5 which showed a lower T1w/T2w ratio in the occipital and posterior cingulate cortex. Although we did not expect a preferential involvement of specific cortical regions a priori, several previous studies have reported the presence of atrophy and microstructural damage affecting predominantly posterior brain areas in MS,28–30 thus suggesting that cortical pathology is not evenly distributed across the brain. As per the intracortical distribution of GM damage, the presence of extensive abnormalities in PMS, involving all cortical layers, could be the consequence of reduced afferent synaptic input from neighboring neurons and retrograde degeneration of efferent pyramidal axons damaged within the WM, which might favor dendritic spine loss.2,4 The diffuse pattern of cortical involvement identified in PMS in comparison with RRMS is in line with the knowledge that several mechanisms inducing cortical pathology are more severe in progressive patients.6 On the other hand, in RRMS, meningeal inflammation seems to occur more frequently than originally described31 and might be responsible for the observed changes in the T1w/T2w ratio in the subpial cortical layer, as inflammation-related excitotoxicity induces a synaptopathy32 that might be responsible for the dendritic damage possibly captured by the T1w/T2w ratio.

The main limitations to consider when interpreting our results are the small sample size, which might have limited our ability to fully characterize the extent of cortical pathology, and the uncertainty about the pathologic substrate behind the observed T1w/T2w ratio modifications. In addition, although the evaluation of the clinical impact of T1w/T2w ratio alterations was beyond the scope of our article, future studies on larger samples and with multidimensional evaluation of clinical status would be of interest to clarify the relationship between T1w/T2w ratio alterations and disability. Finally, the cortex segmentation in 6 layers has been chosen to provide a reliable set of coordinates for the analysis of the T1w/T2w ratio at different cortical depths taking into consideration cortical anatomy and image resolution, but it is important to keep in mind that the analyzed layers do not correspond to the 6 cytoarchitectonic layers.

In conclusion, laminar analysis of T1w/T2w ratio mapping confirms the presence of cortical damage in MS and discloses a variable expression of intracortical damage according to the disease phenotype. Although in the relapsing-remitting stage, only the subpial layer appears susceptible to damage, in progressive patients, widespread cortical abnormalities can be observed, not only, as described before, with regard to myelin/iron concentration2 but, possibly, to other microstructural substrates.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Alessandro Maria Toni, BE, for his valuable assistance in figure production.

Glossary

- CL

cortical lesion

- GM

gray matter

- HC

healthy control

- MPRAGE

Magnetization-Prepared Rapid Acquisition of Gradient Echo

- PMS

progressive MS

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting MS

- SPACE

Sampling Perfection with Application optimized Contrasts using different flip angle Evolution

- WM

white matter

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was supported in part by a grant from Teva Neuroscience (CNS-2014-221).

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Trapp BD, Vignos M, Dudman J, et al. Cortical neuronal densities and cerebral white matter demyelination in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:870–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mainero C, Louapre C, Govindarajan ST, et al. A gradient in cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis by in vivo quantitative 7 T imaging. Brain 2015;138:932–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocozza S, Cosottini M, Signori A, et al. A clinically feasible 7-tesla protocol for the identification of cortical lesions in multiple sclerosis. Eur Radiol;2020. 30:4586–4594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jürgens T, Jafari M, Kreutzfeldt M, et al. Reconstruction of single cortical projection neurons reveals primary spine loss in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2016;139:39–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Righart R, Biberacher V, Jonkman LE, et al. Cortical pathology in multiple sclerosis detected by the T1/T2-weighted ratio from routine magnetic resonance imaging. Ann Neurol 2017;82:519–529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calabrese M, Magliozzi R, Ciccarelli O, Geurts JJ, Reynolds R, Martin R. Exploring the origins of grey matter damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2015;16:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 Revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruggieri S, Petracca M, Miller A, et al. Association of deep gray matter damage with cortical and spinal cord degeneration in primary progressive multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 2015;72:1466–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van De Pavert SHP, Muhlert N, Sethi V, et al. DIR-visible grey matter lesions and atrophy in multiple sclerosis : partners in crime ? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2016;87:461–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petracca M, Saiote C, Bender HA, et al. Synchronization and variability imbalance underlie cognitive impairment in primary-progressive multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep 2017;7:46411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inglese M, Petracca M, Mormina E, et al. Cerebellar volume as imaging outcome in progressive multiple sclerosis. PLoS One 2017;12:e0176519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zurawski J, Tauhid S, Chu R, et al. 7T MRI cerebral leptomeningeal enhancement is common in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis and is associated with cortical and thalamic lesions. Mult Scler J 2020;26:177–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, et al. The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. Neuroimage 2013;80:105–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jovicich J, Czanner S, Greve D, et al. Reliability in multi-site structural MRI studies: effects of gradient non-linearity correction on phantom and human data. Neuroimage 2006;30:436–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glasser MF, Van Essen DC. Mapping human cortical areas in vivo based on myelin content as revealed by T1- and T2-weighted MRI. J Neurosci 2011;31:11597–11616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashburner J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 2007;38:95–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waehnert MD, Dinse J, Weiss M, et al. Anatomically motivated modeling of cortical laminae. Neuroimage 2014;93(pt 2):210–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sprooten E, O'Halloran R, Dinse J, et al. Depth-dependent intracortical myelin organization in the living human brain determined by in vivo ultra-high field magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 2019;185:27–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Glasser MF, Coalson TS, Robinson EC, et al. A multi-modal parcellation of human cerebral cortex. Nature 2016;536:171–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nieuwenhuys R. The myeloarchitectonic studies on the human cerebral cortex of the Vogt-Vogt school, and their significance for the interpretation of functional neuroimaging data. Brain Struct Funct 2013;218:303–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nieuwenhuys R, Broere CA. A map of the human neocortex showing the estimated overall myelin content of the individual architectonic areas based on the studies of Adolf Hopf. Brain Struct Funct 2017;222:465–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grydeland H, Walhovd KB, Tamnes CK, Westlye LT, Fjell AM. Intracortical myelin links with performance variability across the human lifespan: results from T1- and T2-weighted MRI myelin mapping and diffusion tensor imaging. J Neurosci 2013;33:18618–18630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shafee R, Buckner RL, Fischl B. Gray matter myelination of 1555 human brains using partial volume corrected MRI images. Neuroimage 2015;105:473–485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arshad M, Stanley JA, Raz N. Test–retest reliability and concurrent validity of in vivo myelin content indices: myelin water fraction and calibrated T1w/T2w image ratio. Hum Brain Mapp 2017;38:1780–1790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peterson JW, Bö L, Mörk S, Chang A, Trapp BD. Transected neurites, apoptotic neurons, and reduced inflammation in cortical multiple sclerosis lesions. Ann Neurol 2001;50:389–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pareto D, Garcia-Vidal A, Alberich M, et al. Ratio of T1-weighted to T2-weighted signal intensity as a measure of tissue integrity: comparison with magnetization transfer ratio in patients with multiple sclerosis. Am J Neuroradiol 2020;4:461–463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Granberg T, Fan Q, Treaba CA, et al. In vivo characterization of cortical and white matter neuroaxonal pathology in early multiple sclerosis. Brain 2017;140:2912–2926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eshaghi A, Marinescu RV, Young AL, et al. Progression of regional grey matter atrophy in multiple sclerosis. Brain 2018;141:1665–1677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Audoin B, Fernando KT, Swanton JK, Thompson AJ, Plant GT, Miller DH. Selective magnetization transfer ratio decrease in the visual cortex following optic neuritis. Brain 2006;129:1031–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mallik S, Muhlert N, Samson RS, et al. Regional patterns of grey matter atrophy and magnetisation transfer ratio abnormalities in multiple sclerosis clinical subgroups: a voxel-based analysis study. Mult Scler J 2015;2:423–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harrison DM, Wang KY, Fiol J, et al. Leptomeningeal enhancement at 7T in multiple sclerosis: frequency, morphology, and relationship to cortical volume. J Neuroimaging 2017;27:461–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandolesi G, Gentile A, Musella A, et al. Synaptopathy connects inflammation and neurodegeneration in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2015;11:711–724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data set analyzed in the present study will be made available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.