Abstract

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease characterized by the progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta and the presence of Lewy bodies, which gives rise to motor and non-motor symptoms. Unfortunately, current therapeutic strategies for PD merely treat the symptoms of the disease, only temporarily improve the patients’ quality of life, and are not sufficient for completely alleviating the symptoms. Therefore, cell-based therapies have emerged as a novel promising therapeutic approach in PD treatment. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) have arisen as a leading contender for cell sources due to their regenerative and immunomodulatory capabilities, limited ethical concerns, and low risk of tumor formation. Although several studies have shown that MSCs have the potential to mitigate the neurodegenerative pathology of PD, variabilities in preclinical and clinical trials have resulted in inconsistent therapeutic outcomes. In this review, we strive to highlight the sources of variability in studies using MSCs in PD therapy, including MSC sources, the use of autologous or allogenic MSCs, dose, delivery methods, patient factors, and measures of clinical outcome. Available evidence indicates that while the use of MSCs in PD has largely been promising, conditions need to be standardized so that studies can be effectively compared with one another and experimental designs can be improved upon, such that this body of science can continue to move forward.

Subject terms: Stem-cell research, Parkinson's disease, Translational research, Mesenchymal stem cells, Parkinson's disease

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most common neurodegenerative disease with a prevalence of 0.5–1% among people 65–69 years of age, and rising to 1–3% among people of 80 years of age and older1. The pathological hallmarks of PD are a progressive and gradual loss of dopaminergic (DA) neurons of the nigrostriatal pathway and in the substantia nigra pars compacta2, the presence of neuronal α-synuclein inclusions called Lewy bodies, and neuro-inflammation in various brain regions3,4. The loss of DA neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta results in typical clinical manifestation and the classification of PD as a movement disorder characterized by resting tremor, postural instability, rigidity, and bradykinesia5,6. Symptoms of PD usually appear around 55 years of age when roughly 80% of the nigrostriatal DA system is degenerated7,8. However, PD pathology extends beyond the nigrostriatal DA pathway. Lewy pathology is also found in the vagus nerve, spinal cord, sympathetic ganglia, and cardiac and myenteric plexuses9,10. This leads to a number of secondary motor and non-motor symptoms9,11 such as neuropsychiatric disorders (anxiety and depression), autonomic dysfunction (constipation), sleep abnormalities (insomnia), olfaction and visual disorders, and cognitive decline including dementia12,13.

Although the precise mechanism leading to neuronal loss in PD is still unknown, it appears to be multifactorial. The pathogenic mechanisms proposed to play a role in PD include genetic factors, excessive release of oxygen free radicals and oxidative stress, dysfunctional protein degradation, glial dysfunction, lack of trophic factors, inflammation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and accumulation of damaged mitochondria in DA neurons14,15.

The main treatments for PD patients include the administration of dopamine precursor l-3,4-dihydroxyphenylalanine (levodopa; l-dopa), dopamine receptor agonists, and inhibitors of endogenous dopamine degradation enzymes (catechol-O-methyl transferase and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors), as well as surgical procedures such as deep brain stimulation (DBS)16. Pharmacological strategies can restore DA activity and improve the motor symptoms of PD, especially in the early stages of disease. However, their administration does not improve and may even exacerbate non-motor manifestations of PD, such as postural hypotension and neuropsychiatric problems17,18. In regard to the most commonly used pharmaceutical therapy, levodopa, prolonged administration results in undesirable side effects such as dyskinesia and neuropsychiatric pathologies including hallucinations and impulsive-compulsive behaviors19,20. Similar to pharmaceutical treatment, DBS is effective in controlling the motor symptoms of PD, but does not allay most of the non-motor pathological manifestations21. In order to find a cure for PD, various approaches using anti-inflammatory drugs22 and neurotrophic factors23 are being tested in preclinical models. In line with these increasing efforts to improve the efficacy of PD treatment, cell-based therapy has been raised as a promising alternative approach24.

In this review, we describe the evolution of cell therapy in PD, highlight why mesenchymal stem/stromal cells (MSCs) are a promising option in the treatment of this disease, and stress the multitude of potential variabilities that can arise from MSC-based clinical trials in PD.

Evolution of cell therapy for treatment of PD

Due to the selective degeneration of neurons in PD, cell-based therapies including neuronal transplantation were viewed as compelling therapeutic approaches. The proposed mechanisms of cell transplantation that allow for the mitigation of neurodegeneration and symptoms include neurite outgrowth of grafts, graft innervation, and formation of synaptic connections with the host tissue25, the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase, the release of dopamine, and the release of neurotrophic and neuroprotective bioactive molecules from the transplanted cells26,27.

Over 50 years ago, the first preclinical studies involving the transplantation of rat and human-derived fetal ventral mesencephalon (hfVM) neuroblasts into rodent brains were conducted28. Subsequent studies in animal models of PD demonstrated that transplanted DA neurons obtained from the fetal midbrain were able to integrate into host tissue, release dopamine, and improve motor function. This discovery revolutionized cell-based replacement therapy as a treatment for PD29. Based on these encouraging results, several scientific groups conducted open-label clinical trials in PD patients. However, the results were variable, with only moderate to no significant improvement30,31. These inconsistencies were largely due to highly variable trial design in addition to technical difficulties including cell type variability in tissue grafts, phenotypic instability after passaging, and poor proliferation and survival in the brain after grafting32,33. Further challenges in the use of hfVM neuroblasts in PD treatment included the host immune response to an allogenic graft, ethical concerns regarding the use of fetal tissue, and the potential for malignant transformation34,35. Due to these limitations of hfVM neuroblast-based treatment, the focus has shifted to an alternative source of cells for regenerative therapies and transplantation in PD. Recently, enormous progress has been made in the field, and several different strategies and cell sources have been tested for their potential in PD treatment including human embryonic stem cells, human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSCs), human neural stem cells, hiPSC-derived neural stem cells, and human MSCs. The concerns and the advantages of different stem cells sources for PD treatment are included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Comparison of different sources of cells for cell therapy.

| hESCs | iPSCs | hNSCs | iPSC-derived hNSCs | MSCs | iPSC-derived MSCs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethical concerns | ! | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Genomic stability | ! | ! | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ! |

| Risk of tumor formation | ! | ! | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ! |

| Allogenic and autologous source available | ! | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Risk of immunological rejection | ! | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Donor-age-related issues | ✓ | ! | ✓ | ! | ! | ✓ |

✓ safe/advantage, ! concerns/disadvantage.

The potential of hMSC-based therapy for PD treatment

Researchers with interest in PD have focused their attention on cell-based therapies using MSCs due to their widespread availability in the body36, proliferative abilities, and immunomodulatory capabilities37. The therapeutic potential of MSCs involves several mechanisms. Human MSCs are able to secrete protective neurotrophic factors, anti-apoptotic factors, growth factors, and cytokines (vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), beta-nerve growth factor (β-NGF), transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2), and glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF)) into a damaged, inflamed area38. In this way, MSCs could promote repair through the production of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin (IL)-10 and TGF-β39 in addition to the inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines (tumor necrosis factor-α, interferon gamma (IFN-γ), and IL-1 β), which have been identified to be released in the brains of PD patients40,41. MSCs also mediate hematopoiesis regulation and tissue regeneration through their paracrine signaling and multipotency, respectively42. Moreover, MSCs have the potential to be differentiated into a neural lineage, including DA neuron precursors43,44. However, it remains unclear whether undifferentiated MSCs or MSCs that have undergone neuronal differentiation are able to integrate into host neural circuits and create new synaptic connections with host neurons45,46. Recent findings indicating that MSCs can transfer mitochondria to damaged tissue represent another intriguing mechanism that could be beneficial in PD therapy due to the proposed central role of damaged mitochondria in neurodegeneration of DA neurons47. MSC therapy has been shown to be safe with no increased risk of neoplastic transformation (Table 1)48.

The challenges of hMSC cell-based therapies for PD treatment

Previous clinical studies using MSCs in the treatment of PD in humans have provided promising preliminary data. In an open-label study in 2010, autologous bone marrow (BM)-derived MSCs with a dose of 106 cells per kilogram body weight were stereotactically administered unilaterally into the sublateral ventricular zone in seven patients with PD49. Three patients were reported to have improved PD symptoms. In 2012, the same research group started another open-label study using allogeneic BM-derived MSCs with a dose of 2 × 106 cells per kilogram of body weight and stereotactic administration bilaterally into the sublateral ventricular zone into eight patients with PD and eight with advanced symptoms of PD recognized as “PD plus”50. The group reported persistent improvement of symptoms in PD patients and transient improvement of symptoms in “PD plus” patients.

Currently, seven clinical trials using MSCs for PD treatment are in progress with highly variable set up (Table 2). There is a distinct lack of consistency between clinical trials, such that these studies are difficult to compare with one another in order to pinpoint what needs to be improved upon in future studies. In the following sections, we highlight the sources of variability in MSC-based PD therapy in an effort to draw attention to the need for increased standardization in this field.

Table 2.

Clinical studies involving MSC therapy in Clinicaltrials.gov website.

| Study Title | Source of MSCs | Autologous or Allogenic Transplant | Dose Delivery | PD Pathology | Age | Outcome Measures | Identifier and Phase | Status as of January 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study to assess the safety and effects of autologous adipose-derived SVF cells in patients with Parkinson’s disease | Adipose tissue-derived MSCs | Autologous | Delivered to vertebral artery and intravenous administration | Current diagnosis of PD with motor complications | 18–80 years |

Change in motor function Changes in mental state |

Phase 1/2 |

Withdrawn |

| Outcomes data of adipose stem cells to treat Parkinson’s disease | Adipose tissue-derived MSCs | Autologous | Not provided | Idiopathic PD | 18 years and older | Change from baseline in overall quality of life | NCT02184546 | Active, not recruiting |

| Use of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) differentiated into neural stem cells (NSCs) in people with Parkinson’s (PD). | Umbilical cord-derived MSCs | Allogenic | Intrathecally and intravenously | Diagnosis of PD for between 1 to 7 years | 20–75 years |

Tractography Blood-based biomarkers Cerebrospinal fluid-based biomarkers |

Phase 1/2 |

Recruiting |

| Allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell therapy for idiopathic Parkinson’s disease | Bone marrow-derived MSCs | Allogenic | Intravenously at one of four doses: 1 × 106 MSC/kg, 3 × 106 MSC/kg, 6 × 106 MSC/kg, or 10 × 106 MSC/kg | Idiopathic PD | 45–70 years |

Change in motor function Change in disability. Functional magnetic resonance imaging or diffusion tensor imaging Change in quality of life Change in cognitive function Change in immunologic response Change in suicidal ideation |

Phase 1/2 |

Completed |

| Mesenchymal stem cells transplantation to patients with Parkinson’s disease | Bone marrow-derived MSCs | Autologous | Intravenous administration of up to 6 × 105 MSCs/kg, once a week for 4 weeks |

Diagnosis of PD for more than 2 years Motor complications despite optimized levodopa treatment PD of Stage 2–2.5 3 or 4 of Hoehn-Yahr staging |

30–65 years |

Number of participants with adverse events Effect assessment |

Phase 1/2 |

Unknown |

| Umbilical cord-derived mesenchymal stem cells therapy in Parkinson’s disease | Umbilical cord-derived MSCs | Allogenic | Intravenous administration of 10–20 × 106 MSCs once a week for 3 weeks | PD | 40–60 years |

Change in motor function Changes in mental state |

Phase 1 |

Recruiting |

| Individual patient expanded access IND of hope biosciences autologous adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells for Parkinson’s disease | Adipose tissue-derived MSCs | Autologous | Intravenous administration of 2 × 108 MSCs 2 weeks apart for two infusions and then monthly for 6 additional infusions, 8 infusions total | PD | 18 years and older |

Change in motor function Change from baseline in overall quality of life Change in immunologic response |

NCT04064983 | Expanded access no longer available |

PD Parkinson’s disease, MSCs mesenchymal stromal/stem cells, IND Investigational New Drug, NCSs neural stem cells, SVF stromal vascular fraction.

PD patient: selection and outcome measures

One source of variability in the studies is the PD classification and selection of patients for the study. To date, tests allowing for the diagnosis of PD in early stages are missing. The more precise diagnosis of PD is based on the presence of substantia nigra pars compacta degeneration and Lewy pathology found during the post-mortem pathological examination. Therefore, the current diagnosis of PD is based on the symptoms that arise in the later stages of the disease, when approximately 80% of DA neurons have already been damaged.

Classification and staging of PD vary and can lead to a high degree of heterogeneity in defined PD groups. Nevertheless, classification and prediction of disease progression has significant consequences for the selection of therapeutic strategies and the potential success of treatments. Currently, clinical studies focused on MSC-mediated PD treatment have mainly used age and time from diagnosis as inclusion or exclusion criteria. These studies also vary in the outcome measures for the evaluation of MSC treatment success (Table 2), although strides have recently been made to propose a global consensus of outcome measures for PD51. Moreover, these scales, which include the Hoehn and Yahr scale52, the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS)53, the Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the UPDRS54, NMS-Quest55, and the physician-assisted non-motor symptoms scale56, are not only used for selection of the patient but also for measuring the clinical improvements. More objective selection criteria and improvement measures might include functional magentic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance tractography, and blood and cerebral fluid biomarkers57,58. Another important question arising from measuring the outcomes is the timing of follow-up. Thus, the use of more unified clinical groups as well as outcome measures is crucial for the successful assignment of cell therapy treatment strategies.

Donor: autologous versus allogenic

MSC-mediated treatment offers both options: autologous and allogenic transplantation. Autologous MSCs are mainly isolated from adipose tissue (AD) and BM. Variability in autologous MSC therapy between patients can stem from different aspiration techniques during harvesting, which can influence cell yield, viability, and differentiation potential59,60. Autologous MSCs are more likely to garner harvesting variabilities than allogenic MSCs, due to the need to harvest MSCs from each patient rather than having one source of expanded MSCs for experimental use. Some studies in AD-derived MSCs have found a negative correlation between donor age and cell proliferation of the MSCs61. Similarly, the yield of MSCs from BM aspirate has been found to have a negative correlation with age62. Furthermore, a study using immortalized AD-derived MSCs from PD patients have demonstrated significant mitochondrial dysfunction in the MSCs as compared to the immortalized MSCs of non-PD patients63. Additionally, several studies have proposed that PD pathology might limit the regenerative capacity of autologous MSCs due to their autophagy and decreased mitochondrial functions64. This raises concerns regarding the potential efficacy of PD patient-derived MSCs. Furthermore, both pathological and clinical studies have shown that PD pathology affects not only the central nervous system (CNS) but spans through several organs, which could impact the effectiveness of autologous MSC treatment. In addition to the systemic nature of PD, the age of the patient and the systemic effect of PD medication both have important implications for autologous MSC treatment and should be taken into consideration65.

Allogenic MSCs can be isolated from umbilical cord (UC) in addition to BM and AD. The advantages of allogenic MSC transplants include increased timely availability of cells when needed, reduced overall cost, decreased harvesting variability, and the opportunity to conduct more thorough cell quality assessments66. In contrast to autologous MSC treatment, trials involving allogenic MSCs are able to treat patients using MSCs that had undergone extensive quality-assurance measures to mitigate any batch stability or genome issues. Although cryopreservation is applicable to both autologous and allogenic MSCs, variations in freezing technique, composition of freezing media, viability and therapeutic effectiveness of MSCs after thawing represent additional sources of variation among clinical studies67. Another factor to consider in allogenic MSC transplantation is the potential for immune rejection66,68. This raised the question of whether donor human leukocyte antigen (HLA) should be matched with patients or patients should undergo immunosuppression before and/or after MSC transplantation. However, HLA matching would entail the need to have more donors, which would increase time, cost, and harvesting variables69. Additionally, immunosuppression increases the risk of cancer, infection, cardiovascular and metabolic disease, and immune dysregulation, all of which could negatively impact the lives of the patients70. Furthermore, multi-dose regimens have the potential to accelerate the clearance of MSCs due to the boosted allogenic memory-response71. Recent studies have suggested that the immunogenicity of MSCs have no significant adverse impact on the engraftment of MSCs in wound healing72. In general, it is believed that MSCs express a low level of HLA antigen73. However, studies have shown that major HLA class II molecules could be increased during in vitro expansion, which highlights the importance of using low-passage MSCs68. Therefore, while HLA matching may not be necessary, administering HLA-matched MSCs may prolong the survival of the MSCs in vivo. Even though allogenic MSC therapy has been shown to be well tolerated with minimal side effects, there is still concern for the risk of transmitting blood-borne pathogens, and immune rejection, which can lead to the elimination of MSCs and thus potentially lead to a reduced therapeutic effect66,74. Furthermore, an important limitation to the clinical application of both autologous and allogenic MSCs is the potential for their spontaneous differentiation into undesirable cell lineages and tissue types75.

Donor: sources of MSCs

The primary sources of MSCs are BM aspirate, AD, and UC76,77. Considerations must be made regarding the selection of a source. One factor to consider for is the ease and efficiency of harvesting. The harvesting method itself can introduce experimental variability, which has the potential to significantly affect the therapeutic effectiveness of MSCs. Variability can stem from different injection sites within the same sources, or aspiration techniques, which can influence cell yield, viability, and differentiation potential59,60. Compared with AD and UC, harvesting BM is the most invasive and can cause the most pain and infection risk78,79. BM aspirate contains only 0.001–0.01% MSCs in the overall cell population, which translates to roughly 60–600 cells/mL of aspirate76. Considering that only a limited volume of aspirate can be withdrawn, this means that there will typically be an intensive culturing process to expand the MSCs, especially if the cells are to be used allogenically76,79. AD can be harvested from lipid waste generated from lipectomy, lipoplasty, and liposuction. AD can also be harvested from a small area under local anesthesia, making this procedure much less invasive and hazardous than BM harvesting and therefore arguably a better source for autologous use79,80. Furthermore, an AD harvest obtains a 500 times greater yield of MSCs than an equivalent amount of BM aspirate81,82. Compared to BM and AD, UC harvesting is the least invasive and poses no ethical challenges due to the UC tissue being derived aseptically from cesarean sections83,84. Additionally, due to the nature of UC, there are no age-related problems, which can cause issues in adult MSC isolations. Furthermore, a large amount of MSCs can be derived from one UC, which can minimize the need to extensively expand the cells for allogenic use84. UC tissue can also be cryopreserved after harvesting, allowing for the potential to isolate MSCs as needed. However, the isolation of living MSCs from thawed, previously cryopreserved tissue is not always possible due to the differential proximity of the MSCs to the cryoprotectant85.

In addition to harvesting considerations, there are also proliferation differences between sources that need to be considered. It has been found that UC-derived MSCs proliferate faster than AD-derived MSCs, and AD-derived MSCs proliferate faster than BM-derived MSCs83,86. UC-derived MSCs on average have the shortest doubling time at 24 h87, compared to AD-derived MSCs which have a doubling time of 40 h, and BM-derived MSCs which have a doubling time of 60 h79,88. UC-derived MSCs may be more highly proliferative due to UC-derived MSCs not being inhibited by cell-to-cell contact, which allows them to continue to proliferate even after reaching confluence89. Additionally, differences in proliferative abilities may be impacted by the effects of senescence on MSCs. BM-derived MSCs have been found to have senescence landmarks starting at passage 7 (ref. 90), and AD-derived MSCs starting at passage 8 (ref. 88), which can influence the therapeutic effectiveness, number, maximum lifespan, and differentiation abilities of the cells. In contrast, UC-derived MSCs can easily be expanded over passage 16 without any landmarks of senescence and no karyotype instability or variations in morphology91.

Different sources of MSCs have also been found to have differences in their immunological characteristics, as well as have different paracrine signaling and immune modulation abilities92. By definition, MSCs should not have HLA-DR surface markers. However, studies have shown that BM and AD-derived MSCs express HLA-DR surface markers in response to IFN-γ, while UC-derived MSCs do not93. Despite these findings, a study in BM-derived MSCs have demonstrated that HLA-DR surface marker expression appears to be random, and their presence had little effect on the immunomodulation, multilineage differentiation, and their allogenic immune response94. Another surface marker, CD142, has been linked to thrombosis and is a concern for systemic administration of MSCs. BM-derived MSCs have been shown to have lower levels of CD142 as compared to low-passage AD-derived MSCs95,96, which could make BM-derived MSCs more suitable for intravenous MSC delivery and decrease the risk of thrombosis97. In addition to differences in surface markers, MSCs from different sources have been found to have varying paracrine functions. BM-derived MSCs have been found to have significant paracrine functions, including the secretion of angiogenic factors, growth factors, and cytokines98. It has been found that there is a lower secretion of pro-angiogenic molecules and cytokines in AD-derived MSCs as compared to BM-MSCs, which suggests that AD-derived MSCs might be less suited to reducing inflammation99. However, UC-derived MSCs have been found to express more angiogenic, neuroprotective, and neurogenerative factors compared to BM-derived MSCs, which make them an attractive option in PD therapy100. Furthermore, UC-derived MSCs have been found to exhibit a 20–800k relative fold change compared to BM-derived MSCs, which exhibit a 50–1000 relative fold change for indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) upregulation following IFN-γ stimulation69. IDO suppresses T cell responses, which could help increase immune tolerance to allogenic administration of MSCs101.

Another factor that needs to be considered, especially in the treatment of PD, is the impact that the source of the MSCs has on their neuronal differentiation abilities. While BM, AD, and UC-derived MSCs have all been demonstrated to express synaptophysin as evidence of the formation of a synapse102, AD-derived MSCs were exhibited to express the highest level of SAP-90 as compared to BM- and UC-derived MSCs, which indicates that AD-derived MSCs may be more likely to form synaptic structures103. Likewise, BM-, AD-, and UC-derived MSCs were all capable of expressing NT-3, a neurotrophic factor, but AD-derived MSCs had the highest expression103. Furthermore, BM, AD, and UC-derived MSCs were all able to express DA neuron markers in vitro, including nurr1 and tyrosine hydroxylase, which is especially relevant in PD therapy103,104.

A potential strategy for a more objective classification of MSCs includes the analysis of their biomarkers. The minimum criteria for defining the phenotype of MSCs includes the expression of CD73, CD90, and CD105, and the lack of expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79a or CD19, and HLA-DR105. Besides these markers, MSCs express many other surface markers and secrete various bioactive molecules including proteins, immune-modulating molecules, and microRNAs106. Multiple comprehensive transcriptomic and proteomic analyses of human MSCs have revealed different markers that may contribute to the molecular classification of subspecies of MSCs. This could lead to a more targeted approach to MSC therapy, where subspecies of MSCs are applied to specific clinical conditions that their phenotype is most suited to treating107. However, accumulating evidence suggests that marker expression of MSCs is not stable in culture conditions, which could make characterizing MSCs based on their markers a challenge108. So far, it is not clear if the classification based on novel markers can be applicable to clinical studies, but efforts remain ongoing.

Route of delivery and other variabilities

There are several routes for MSC administration in PD treatment. One option is a direct stereotactic transplantation into the affected area. In rodent PD models, direct transplantation into the striatum, substantia nigra, or subthalamic nucleus has been shown to be effective when using BM-derived MSCs109–114, AD-derived MSCs115–117, and UC-derived MSCs118–121. In some of the stereotactic transplant studies, undifferentiated MSCs were shown to differentiate into DA neurons in vivo109,110,118,120. Other studies used MSCs that were differentiated into neurons111,113,116,118, neurotrophic factors-secreting cells112, or nestin-positive stem cells114. Regardless of the PD rodent model (6-hydroxydopamine, 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine, or rotenone model), the majority of these experiments were successful, as was measured by behavioral improvement, reduced microglial activation, increased tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactivity, neuroprotection of DA neurons, and even neurogenesis117,122. Interestingly, AD-derived MSCs did not differentiate in vivo to DA neurons in any of the studies that were reviewed115–117 (Supplementary Table 1). Although the preclinical data for direct transplantation are promising, this delivery route involves a relatively complex surgical procedure, surgery-related risks, possible post-surgical complications, inconvenient administration of repetitive doses, and high costs123.

MSCs have the ability to migrate to injury sites and promote repair, which makes them compelling candidates for systemic administration. Systemic administration of MSCs has been shown to be effective using BM-derived MSCs124–130 and AD-derived MSCs126. In many of these studies, behavioral improvement, neuroprotective effects, and neurogeneration were observed. However, in one study, the MSCs were not able to transmigrate across the blood–brain barrier without a permeabilizing agent131, and in another study, the majority of the MSCs were found to be retained in the lungs rather than in the brain129. While some studies have shown that intravenously administered MSCs can enter the brain without the aid of a permeabilizing agent125,129, many studies did not include experiments regarding the presence of MSCs in the brain126,127,130. The less successful therapeutic outcomes observed via systemic administration of MSCs may be due to the MSCs having difficulty transmigrating across the blood–brain barrier132,133.

An alternative route for the treatment of CNS diseases is intranasal administration132. Studies in preclinical PD models using intranasal administration have demonstrated the successful delivery of MSCs to the brain with localization of MSCs in the olfactory bulb, cortex, hippocampus, striatum, cerebellum, brain stem, amygdala, hippocampus, and spinal cord even 4.5 months after injection134. Furthermore, one study has reported neuroprotective effects, anti-inflammatory effects, and improvements in neurobehavioral tests, indicating that intranasally delivered MSCs are a promising therapeutic option for PD135.

Other variabilities include questions regarding the dose, if the injections should be repeated, and, if so, how those injections should be timed. To date, an effective dose of MSCs for PD applications has not been optimized, and likely is different between administration routes. In the reviewed clinical trials for PD, some studies reported doses that ranged from 6 × 105–10 × 106 MSCs per kilogram of the patients’ weight, some reported the total amount of MSCs used per patient and disregarded weight, and some studies did not report dosage at all. A meta-analysis of animal models of PD concluded that a higher dose of MSCs (<1 × 106 versus ≥1 × 106 MSCs) did show a significant difference in effect for limb function but not in rotation behavior136, yet it is not known whether there is the same effect in non-human primates or humans. Additionally, the studies that have been conducted in primate models of PD have been largely stereotactic137, whereas the majority of clinical trials are reported to use intravenous administration, making it difficult to draw conclusions regarding dosage considerations. Standardization of dosage is necessary to limit variabilities between trials and to gain insight into what aspects needs to be improved.

Future directions and conclusions

Over the decades, scientists and clinicians have put in a tremendous amount of effort into establishing stem cell therapy as an efficient and feasible treatment for neurological diseases including PD. However, systematic translational use of cell therapy is still somewhat out of reach. In order to improve the efficiency of MSC-mediated therapy, several novel strategies have been tested.

One of these approaches is MSC priming or preconditioning. Cell priming involves the exposure of cells to growth conditions that mimic the in vivo microenvironment of damaged tissue. Studies have shown that MSCs can modulate their cellular signaling in response to primed culture conditions138. This pre-activation of intracellular molecular signaling before the transplantation of MSCs may improve their function, survival, and therapeutic efficacy. Several priming approaches have been tested, including priming with inflammatory cytokines or mediators, hypoxia, pharmacological drugs, chemical agents, biomaterials, and different culture conditions139. The disadvantage of this approach is the limited consensus in cell manufacturing protocols, which leads to difficulty in providing quality assurance for clinical-grade MSCs140.

Recently, cell-free therapy has been investigated as a promising alternative approach to regenerative medicine. Several studies have established that the secretome of MSCs, which includes cytokines, growth factors, and various bioactive molecules, is what mediates their therapeutic properties. MSC-conditioned medium has been shown to have therapeutic potential in cardiovascular disease, osteoarthritis, spinal cord injury, gastric mucosal injury, and colitis141,142. One of the components of MSC-conditioned medium is extracellular vesicles (EVs). EVs are nanovesicles that contain numerous types of proteins and RNAs, mediate communication between cells, and regulate various biological processes including immune response, angiogenesis, proliferation, and differentiation143. EVs have emerged as a key component in the MSC-mediated therapeutic response in the cardiovascular, neurological, musculoskeletal, and immune systems144. The advantage of using EVs isolated from MSC-conditioned media stems from the therapy being a cell-free approach, which requires easier administration and avoids the potentially adverse effects of cell therapy. MSC-derived EVs have been shown to provide therapeutic benefits in the treatment of various CNS disorders including stroke145, traumatic brain injury146, Alzheimer’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and Huntington’s disease147. Moreover, it has been shown that MSC-derived EVs mediate the rescue of DA neurons in rodent PD models148. Additionally, the ability of EVs to cross the blood–brain barrier presents an attractive biological vehicle for the delivery of bioactive molecules into the brain149. However, EVs may be a part of heterogeneous populations, and their metabolomic and lipidomic profiles have not yet been well characterized. Other limitations of EV isolation and purification involve the procedure itself, which includes variability in the quality of EV preparations, the yield of EVs, and the potential for non-EV contaminants in the preparation150. Before using EVs in clinical trials, this approach still needs to be extensively evaluated for safety and efficacy.

In order to improve the generation of homogeneous, standardized, high-quality MSCs, the production of MSCs from hiPSCs has been proposed as an unlimited source of cells for therapeutic applications in regenerative medicine. Although hiPSC-derived MSCs meet the criteria for MSCs in terms of marker expression, other criteria such as the potential to differentiate to chondrogenic and adipogenic tissue are reduced compared with BM-MSCs151. The safety and efficacy of iPSC-derived MSCs are of paramount importance for successful application in the field of translational regenerative medicine. The major concerns regarding iPSC-derived MSCs include determining a suitable starter cell line152 and using a reprogramming strategy that is safe for patients. The viral vector-based strategy for reprogramming might present a potential for tumorigenic transformation153. However, recent developments in non-viral based technologies including chemicals, plasmids, and recombinant protein-based approaches might present safer strategies for the generation of iPSC-derived MSCs suitable for use in a clinical setting154.

Genome-edited MSCs that over-express or inhibit specific genes represent another challenging yet promising approach to improve the therapeutic properties of MSCs. Specifically for PD, several studies using engineered MSCs that expressed tyrosine hydroxylase155, vascular endothelial growth factor156, or were transduced to produce increased glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor157 or cerebral dopamine neurotrophic factor158 have demonstrated positive results in preclinical rodent models. However, viral transduction and genetic modification imparts added safety concerns to cell therapy, which creates additional barriers to clinical testing.

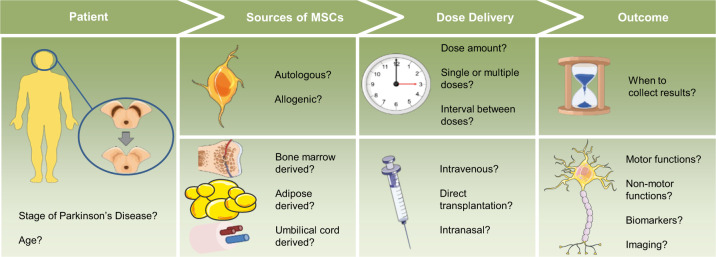

The field of cell-based therapies for PD treatment has faced several challenges. The missing or modest clinical improvement in PD patients treated with MSCs seems to have been the consequence of high variability in clinical trials. In this review, we wanted to stress that allogenic versus autologous transplantation, donor tissue source, culture conditions, PD stage, route of administration, dose, clinical evaluation criteria, and timing of evaluation are sources of variability that can lead to inconsistent results (Fig. 1). Nevertheless, MSCs harbor significant therapeutic potential for the treatment of PD. The advantages of using MSCs for PD therapy include their widespread availability and accessibility, potential for transdifferentiation into neural lineages including DA neurons, immunosuppression in the brain and inhibition of pro-inflammatory cytokines, migratory capacity towards damaged areas, and limited histocompatibility and ethical concerns. The experience gained in previous clinical trials should guide the future directions and emphasize the crucial need for a systematic approach to searching for optimal combinations of conditions in order to achieve reliable and effective treatment designs for PD.

Fig. 1. Roadmap of clinical considerations regarding the use of MSCs in PD therapy.

Relevant sources of variability in clinical trials for PD include patient factors, MSC sources, dose delivery, and clinical outcomes of therapy. Created using elements of Servier Medical Art by Servier, licensed under CC BY 3.0 (https://smart.servier.com/).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Center for Regenerative Medicine, Mayo Clinic.

Author contributions

D.F. and J.A.K. wrote and revised the paper. A.C.Z. designed, revised, and supervised the writing of this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41536-020-00106-y.

References

- 1.Schneider SA, Obeso JA. Clinical and pathological features of Parkinson’s disease. Curr. Top. Behav. Neurosci. 2015;22:205–220. doi: 10.1007/7854_2014_317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hornykiewicz O. Parkinson’s disease: from brain homogenate to treatment. Fed. Proc. 1973;32:183–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Liu Y, Zhou J. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease and its potential as therapeutic target. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015;4:19. doi: 10.1186/s40035-015-0042-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.More SV, Kumar H, Kim IS, Song SY, Choi DK. Cellular and molecular mediators of neuroinflammation in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Mediators Inflamm. 2013;2013:952375. doi: 10.1155/2013/952375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dauer W, Przedborski S. Parkinson’s disease: mechanisms and models. Neuron. 2003;39:889–909. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00568-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jankovic J. Parkinson’s disease: clinical features and diagnosis. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2008;79:368–376. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.131045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrish PK, Sawle GV, Brooks DJ. Clinical and [18F] dopa PET findings in early Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1995;59:597–600. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.59.6.597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jankovic J, Kapadia AS. Functional decline in Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58:1611–1615. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.10.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Tredici K, Braak H. Lewy pathology and neurodegeneration in premotor Parkinson’s disease. Mov. Disord. 2012;27:597–607. doi: 10.1002/mds.24921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braak H, Sastre M, Bohl JR, de Vos RA, Del Tredici K. Parkinson’s disease: lesions in dorsal horn layer I, involvement of parasympathetic and sympathetic pre- and postganglionic neurons. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;113:421–429. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0193-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohnen NI, et al. Extra-nigral pathological conditions are common in Parkinson’s disease with freezing of gait: an in vivo positron emission tomography study. Mov. Disord. 2014;29:1118–1124. doi: 10.1002/mds.25929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gelb DJ, Oliver E, Gilman S. Diagnostic criteria for Parkinson disease. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:33–39. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hughes AJ, Daniel SE, Lees AJ. The clinical features of Parkinson’s disease in 100 histologically proven cases. Adv. Neurol. 1993;60:595–599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch EC, Hunot S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: a target for neuroprotection? Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:382–397. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Truban D, Hou X, Caulfield TR, Fiesel FC, Springer W. PINK1, Parkin, and mitochondrial quality control: what can we learn about Parkinson’s disease pathobiology. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:13–29. doi: 10.3233/JPD-160989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Savitt JM, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Diagnosis and treatment of Parkinson disease: molecules to medicine. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:1744–1754. doi: 10.1172/JCI29178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Young BK, Camicioli R, Ganzini L. Neuropsychiatric adverse effects of antiparkinsonian drugs. Characteristics, evaluation and treatment. Drugs Aging. 1997;10:367–383. doi: 10.2165/00002512-199710050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kujawa K, Leurgans S, Raman R, Blasucci L, Goetz CG. Acute orthostatic hypotension when starting dopamine agonists in Parkinson’s disease. Arch. Neurol. 2000;57:1461–1463. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.10.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ernst AM. The role of biogenic amines in the extra-pyramidal system. Acta Physiol. Pharm. Neerl. 1969;15:141–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Voon V, et al. Chronic dopaminergic stimulation in Parkinson’s disease: from dyskinesias to impulse control disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1140–1149. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70287-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalia SK, Sankar T, Lozano AM. Deep brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease and other movement disorders. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2013;26:374–380. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283632d08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anusha C, Sumathi T, Joseph LD. Protective role of apigenin on rotenone induced rat model of Parkinson’s disease: suppression of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress mediated apoptosis. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2017;269:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2017.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hegarty SV, Lee DJ, O’Keeffe GW, Sullivan AM. Effects of intracerebral neurotrophic factor application on motor symptoms in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2017;38:19–25. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2017.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Han F, et al. Development of stem cell-based therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Neurodegener. 2015;4:16. doi: 10.1186/s40035-015-0039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pantcheva P, Reyes S, Hoover J, Kaelber S, Borlongan CV. Treating non-motor symptoms of Parkinson’s disease with transplantation of stem cells. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2015;15:1231–1240. doi: 10.1586/14737175.2015.1091727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ara J, et al. Inactivation of tyrosine hydroxylase by nitration following exposure to peroxynitrite and 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1998;95:7659–7663. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindsay RM, Altar CA, Cedarbaum JM, Hyman C, Wiegand SJ. The therapeutic potential of neurotrophic factors in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 1993;124:103–118. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1993.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Björklund AJ. Reconstruction of the nigrostriatal dopamine pathway by intracerebral nigral transplants. Brain Res. 1979;177:555–560. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(79)90472-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Björklund AJ. Reinnervation of the denervated striatum by substantia nigra transplants: functional consequences as revealed by pharmacological and sensorimotor testing. Brain Res. 1980;199:307–333. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90692-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kordower JH, et al. Neuropathological evidence of graft survival and striatal reinnervation after the transplantation of fetal mesencephalic tissue in a patient with Parkinson’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 1995;332:1118–1124. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504273321702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piccini P, et al. Dopamine release from nigral transplants visualized in vivo in a Parkinson’s patient. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:1137–1140. doi: 10.1038/16060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Courtois ET, et al. In vitro and in vivo enhanced generation of human A9 dopamine neurons from neural stem cells by Bcl-XL. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:9881–9897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.054312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramos-Moreno T, Lendinez JG, Pino-Barrio MJ, Del Arco A, Martinez-Serrano A. Clonal human fetal ventral mesencephalic dopaminergic neuron precursors for cell therapy research. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e52714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganz J, Lev N, Melamed E, Offen D. Cell replacement therapy for Parkinson’s disease: how close are we to the clinic? Expert Rev. Neurother. 2011;11:1325–1339. doi: 10.1586/ern.11.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Piquet AL, Venkiteswaran K, Marupudi NI, Berk M, Subramanian T. The immunological challenges of cell transplantation for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Bull. 2012;88:320–331. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2012.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paul G, et al. The adult human brain harbors multipotent perivascular mesenchymal stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paul G, Anisimov SV. The secretome of mesenchymal stem cells: potential implications for neuroregeneration. Biochimie. 2013;95:2246–2256. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Boucherie C, Hermans E. Adult stem cell therapies for neurological disorders: benefits beyond neuronal replacement? J. Neurosci. Res. 2009;87:1509–1521. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nasef A, et al. Identification of IL-10 and TGF-β transcripts involved in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation during cell contact with human mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Expr. 2006;13:217–226. doi: 10.3727/000000006780666957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagatsu T, Mogi M, Ichinose H, Togari A. Cytokines in Parkinson’s disease. J. Neural Transm. Suppl. 2000;58:143–151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tansey MG, Goldberg MS. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s disease: its role in neuronal death and implications for therapeutic intervention. Neurobiol. Dis. 2010;37:510–518. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caplan AI. Adult mesenchymal stem cells: when, where, and how. Stem Cells Int. 2015;2015:628767. doi: 10.1155/2015/628767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Joyce N, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells for the treatment of neurodegenerative disease. Regen. Med. 2010;5:933–946. doi: 10.2217/rme.10.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hayashi T, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stem cell-derived dopaminergic neurons function in parkinsonian macaques. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:272–284. doi: 10.1172/JCI62516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zeng X, et al. Integration of donor mesenchymal stem cell-derived neuron-like cells into host neural network after rat spinal cord transection. Biomaterials. 2015;53:184–201. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.02.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Blandini F, et al. Transplantation of undifferentiated human mesenchymal stem cells protects against 6-hydroxydopamine neurotoxicity in the rat. Cell Transpl. 2010;19:203–217. doi: 10.3727/096368909X479839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu K, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells rescue injured endothelial cells in an in vitro ischemia-reperfusion model via tunneling nanotube like structure-mediated mitochondrial transfer. Microvasc. Res. 2014;92:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Centeno CJ, et al. A multi-center analysis of adverse events among two thousand, three hundred and seventy two adult patients undergoing adult autologous stem cell therapy for orthopaedic conditions. Int. Orthop. 2016;40:1755–1765. doi: 10.1007/s00264-016-3162-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Venkataramana NK, et al. Open-labeled study of unilateral autologous bone-marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in Parkinson’s disease. Transl. Res. 2010;155:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Venkataramana NK, et al. Bilateral transplantation of allogenic adult human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells into the subventricular zone of Parkinson’s disease: a pilot clinical study. Stem Cells Int. 2012;2012:931902. doi: 10.1155/2012/931902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Roos P, et al. A consensus set of outcomes for Parkinson’s disease from the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement. J. Parkinsons Dis. 2017;7:533–543. doi: 10.3233/JPD-161055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hoehn MM, Yahr MD. Parkinsonism: onset, progression and mortality. Neurology. 1967;17:427–442. doi: 10.1212/wnl.17.5.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Goetz CG, et al. Movement Disorder Society Task Force report on the Hoehn and Yahr staging scale: status and recommendations. Mov. Disord. 2004;19:1020–1028. doi: 10.1002/mds.20213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goetz CG, et al. Movement Disorder Society-sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov. Disord. 2008;23:2129–2170. doi: 10.1002/mds.22340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chaudhuri KR, et al. International multicenter pilot study of the first comprehensive self-completed nonmotor symptoms questionnaire for Parkinson’s disease: the NMSQuest study. Mov. Disord. 2006;21:916–923. doi: 10.1002/mds.20844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chaudhuri KR, et al. The metric properties of a novel non-motor symptoms scale for Parkinson’s disease: results from an international pilot study. Mov. Disord. 2007;22:1901–1911. doi: 10.1002/mds.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Prange S, Metereau E, Thobois S. Structural imaging in Parkinson’s disease: new developments. Curr. Neurol. Neurosci. Rep. 2019;19:50. doi: 10.1007/s11910-019-0964-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, Garcia-Martin E, Agundez JA. Cerebrospinal fluid biochemical studies in patients with Parkinson’s disease: toward a potential search for biomarkers for this disease. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:369. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wilson A, Butler PE, Seifalian AM. Adipose-derived stem cells for clinical applications: a review. Cell Prolif. 2011;44:86–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2010.00736.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bowen JE. Technical issues in harvesting and concentrating stem cells (bone marrow and adipose) PMR. 2015;7:S8–S18. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Maredziak M, Marycz K, Tomaszewski KA, Kornicka K, Henry BM. The influence of aging on the regenerative potential of human adipose derived mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells Int. 2016;2016:2152435. doi: 10.1155/2016/2152435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Stolzing A, Jones E, McGonagle D, Scutt A. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: consequences for cell therapies. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2008;129:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Moon HE, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction of immortalized human adipose tissue-derived mesenchymal stromal cells from patients with Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurobiol. 2013;22:283–300. doi: 10.5607/en.2013.22.4.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Angelova PR, et al. Mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinsonian mesenchymal stem cells impairs differentiation. Redox Biol. 2018;14:474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yasuhara T, Kameda M, Sasaki T, Tajiri N, Date I. Cell therapy for Parkinson’s disease. Cell Transpl. 2017;26:1551–1559. doi: 10.1177/0963689717735411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Griffin MD, Ritter T, Mahon BP. Immunological aspects of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cell therapies. Hum. Gene Ther. 2010;21:1641–1655. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marquez-Curtis LA, Janowska-Wieczorek A, McGann LE, Elliott JA. Mesenchymal stromal cells derived from various tissues: biological, clinical and cryopreservation aspects. Cryobiology. 2015;71:181–197. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2015.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Berglund AK, Fortier LA, Antczak DF, Schnabel LV. Immunoprivileged no more: measuring the immunogenicity of allogeneic adult mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017;8:288. doi: 10.1186/s13287-017-0742-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mennan C, Garcia J, Roberts S, Hulme C, Wright K. A comprehensive characterisation of large-scale expanded human bone marrow and umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;10:99. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1202-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Riminton DS, Hartung HP, Reddel SW. Managing the risks of immunosuppression. Curr. Opin. Neurol. 2011;24:217–223. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328346d47d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhang J, et al. The challenges and promises of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells for use as a cell-based therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015;6:234. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0240-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chen L, Tredget EE, Liu C, Wu Y. Analysis of allogenicity of mesenchymal stem cells in engraftment and wound healing in mice. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7119. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Uccelli A, Moretta L, Pistoia V. Mesenchymal stem cells in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:726–736. doi: 10.1038/nri2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Uhlin M, et al. Risk factors for Epstein-Barr virus-related post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Haematologica. 2014;99:346–352. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2013.087338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Chamberlain G, Fox J, Ashton B, Middleton J. Concise review: mesenchymal stem cells: their phenotype, differentiation capacity, immunological features, and potential for homing. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2739–2749. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pittenger MF, et al. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wexler SA, et al. Adult bone marrow is a rich source of human mesenchymal ‘stem’ cells but umbilical cord and mobilized adult blood are not. Br. J. Haematol. 2003;121:368–374. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Juneja SC, Viswanathan S, Ganguly M, Veillette C. A simplified method for the aspiration of bone marrow from patients undergoing hip and knee joint replacement for isolating mesenchymal stem cells and in vitro chondrogenesis. Bone Marrow Res. 2016;2016:3152065. doi: 10.1155/2016/3152065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mastrolia I, et al. Challenges in clinical development of mesenchymal stromal/stem cells: concise review. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2019;8:1135–1148. doi: 10.1002/sctm.19-0044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kolaparthy LK, Sanivarapu S, Moogla S, Kutcham RS. Adipose tissue—adequate, accessible regenerative material. Int. J. Stem Cells. 2015;8:121–127. doi: 10.15283/ijsc.2015.8.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Strioga M, Viswanathan S, Darinskas A, Slaby O, Michalek J. Same or not the same? Comparison of adipose tissue-derived versus bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem and stromal cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21:2724–2752. doi: 10.1089/scd.2011.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sabol, R. A. et al. Therapeutic potential of adipose stem cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol.10.1007/5584_2018_248 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 83.Mahmood R, Shaukat M, Choudhery MS. Biological properties of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose tissue, umbilical cord tissue and bone marrow. AIMS Cell Tissue Eng. 2018;2:78–90. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jin HJ, et al. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, adipose tissue, and umbilical cord blood as sources of cell therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2013;14:17986–18001. doi: 10.3390/ijms140917986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Fong CY, Subramanian A, Biswas A, Bongso A. Freezing of fresh Wharton’s jelly from human umbilical cords yields high post-thaw mesenchymal stem cell numbers for cell-based therapies. J. Cell Biochem. 2016;117:815–827. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Li CY, et al. Comparative analysis of human mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue under xeno-free conditions for cell therapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2015;6:55. doi: 10.1186/s13287-015-0066-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pirjali T, et al. Isolation and Characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from human umbilical cord Wharton’s jelly and amniotic membrane. Int J. Organ Transpl. Med. 2013;4:111–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peng L, et al. Comparative analysis of mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow, cartilage, and adipose tissue. Stem Cells Dev. 2008;17:761–773. doi: 10.1089/scd.2007.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Choudhery MS, Badowski M, Muise A, Harris DT. Comparison of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from adipose and cord tissue. Cytotherapy. 2013;15:330–343. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Stenderup K, Justesen J, Clausen C, Kassem M. Aging is associated with decreased maximal life span and accelerated senescence of bone marrow stromal cells. Bone. 2003;33:919–926. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zhang X, et al. Isolation and characterization of mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord blood: reevaluation of critical factors for successful isolation and high ability to proliferate and differentiate to chondrocytes as compared to mesenchymal stem cells from bone marrow and adipose tissue. J. Cell Biochem. 2011;112:1206–1218. doi: 10.1002/jcb.23042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Russell AL, Lefavor R, Durand N, Glover L, Zubair AC. Modifiers of mesenchymal stem cell quantity and quality. Transfusion. 2018;58:1434–1440. doi: 10.1111/trf.14597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Kim JH, Jo CH, Kim HR, Hwang YI. Comparison of immunological characteristics of mesenchymal stem cells from the periodontal ligament, umbilical cord, and adipose tissue. Stem Cells Int. 2018;2018:8429042. doi: 10.1155/2018/8429042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grau-Vorster M, Laitinen A, Nystedt J, Vives J. HLA-DR expression in clinical-grade bone marrow-derived multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells: a two-site study. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2019;10:164. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1279-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Christy BA, et al. Procoagulant activity of human mesenchymal stem cells. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;83:S164–S169. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000001485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Le Blanc K, Davies LC. MSCs-cells with many sides. Cytotherapy. 2018;20:273–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2018.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Moll G, et al. Are therapeutic human mesenchymal stromal cells compatible with human blood? Stem Cells. 2012;30:1565–1574. doi: 10.1002/stem.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kwon HM, et al. Multiple paracrine factors secreted by mesenchymal stem cells contribute to angiogenesis. Vasc. Pharm. 2014;63:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Elman JS, Li M, Wang F, Gimble JM, Parekkadan B. A comparison of adipose and bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cell secreted factors in the treatment of systemic inflammation. J. Inflamm. (Lond.) 2014;11:1. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-11-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Hsieh JY, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells from human umbilical cord express preferentially secreted factors related to neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e72604. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0072604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Le Rond S, Gonzalez A, Gonzalez AS, Carosella ED, Rouas-Freiss N. Indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase and human leucocyte antigen-G inhibit the T-cell alloproliferative response through two independent pathways. Immunology. 2005;116:297–307. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2005.02224.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hayase M, et al. Committed neural progenitor cells derived from genetically modified bone marrow stromal cells ameliorate deficits in a rat model of stroke. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2009;29:1409–1420. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Urrutia DN, et al. Comparative study of the neural differentiation capacity of mesenchymal stromal cells from different tissue sources: an approach for their use in neural regeneration therapies. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0213032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Tatard VM, et al. Neurotrophin-directed differentiation of human adult marrow stromal cells to dopaminergic-like neurons. Bone. 2007;40:360–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2006.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Dominici M, et al. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kozlowska U, et al. Similarities and differences between mesenchymal stem/progenitor cells derived from various human tissues. World J. Stem Cells. 2019;11:347–374. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i6.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Billing AM, et al. Comprehensive transcriptomic and proteomic characterization of human mesenchymal stem cells reveals source specific cellular markers. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:21507. doi: 10.1038/srep21507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Lv FJ, Tuan RS, Cheung KM, Leung VY. Concise review: the surface markers and identity of human mesenchymal stem cells. Stem Cells. 2014;32:1408–1419. doi: 10.1002/stem.1681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shetty P, et al. Clinical grade mesenchymal stem cells transdifferentiated under xenofree conditions alleviates motor deficiencies in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Cell Biol. Int. 2009;33:830–838. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li Y, et al. Intracerebral transplantation of bone marrow stromal cells in a 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;316:67–70. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02384-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bouchez G, et al. Partial recovery of dopaminergic pathway after graft of adult mesenchymal stem cells in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurochem. Int. 2008;52:1332–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Sadan O, et al. Protective effects of neurotrophic factor-secreting cells in a 6-OHDA rat model of Parkinson disease. Stem Cells Dev. 2009;18:1179–1190. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Levy YS, et al. Regenerative effect of neural-induced human mesenchymal stromal cells in rat models of Parkinson’s disease. Cytotherapy. 2008;10:340–352. doi: 10.1080/14653240802021330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ye M, et al. Therapeutic effects of differentiated bone marrow stromal cell transplantation on rat models of Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat. Disord. 2007;13:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Schwerk A, et al. Adipose-derived human mesenchymal stem cells induce long-term neurogenic and anti-inflammatory effects and improve cognitive but not motor performance in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. Regen. Med. 2015;10:431–446. doi: 10.2217/rme.15.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.McCoy MK, et al. Autologous transplants of Adipose-Derived Adult Stromal (ADAS) cells afford dopaminergic neuroprotection in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Neurol. 2008;210:14–29. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Schwerk A, et al. Human adipose-derived mesenchymal stromal cells increase endogenous neurogenesis in the rat subventricular zone acutely after 6-hydroxydopamine lesioning. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:199–214. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Shetty P, Thakur AM, Viswanathan C. Dopaminergic cells, derived from a high efficiency differentiation protocol from umbilical cord derived mesenchymal stem cells, alleviate symptoms in a Parkinson’s disease rodent model. Cell Biol. Int. 2013;37:167–180. doi: 10.1002/cbin.10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Weiss ML, et al. Human umbilical cord matrix stem cells: preliminary characterization and effect of transplantation in a rodent model of Parkinson’s disease. Stem Cells. 2006;24:781–792. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Xiong N, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells in rotenone-induced hemiparkinsonian rats. Biol. Blood Marrow Transpl. 2010;16:1519–1529. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Mathieu P, Roca V, Gamba C, Del Pozo A, Pitossi F. Neuroprotective effects of human umbilical cord mesenchymal stromal cells in an immunocompetent animal model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neuroimmunol. 2012;246:43–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Cova L, et al. Multiple neurogenic and neurorescue effects of human mesenchymal stem cell after transplantation in an experimental model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2010;1311:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Smith Y, Wichmann T, Factor SA, DeLong MR. Parkinson’s disease therapeutics: new developments and challenges since the introduction of levodopa. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37:213–246. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Park HJ, Lee PH, Bang OY, Lee G, Ahn YH. Mesenchymal stem cells therapy exerts neuroprotection in a progressive animal model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurochem. 2008;107:141–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Capitelli CS, et al. Opposite effects of bone marrow-derived cells transplantation in MPTP-rat model of Parkinson’s disease: a comparison study of mononuclear and mesenchymal stem cells. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2014;11:1049–1064. doi: 10.7150/ijms.8182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Choi HS, et al. Therapeutic potentials of human adipose-derived stem cells on the mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging. 2015;36:2885–2892. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kim YJ, et al. Neuroprotective effects of human mesenchymal stem cells on dopaminergic neurons through anti-inflammatory action. Glia. 2009;57:13–23. doi: 10.1002/glia.20731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Park HJ, Shin JY, Lee BR, Kim HO, Lee PH. Mesenchymal stem cells augment neurogenesis in the subventricular zone and enhance differentiation of neural precursor cells into dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra of a parkinsonian model. Cell Transpl. 2012;21:1629–1640. doi: 10.3727/096368912X640556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang F, et al. Intravenous administration of mesenchymal stem cells exerts therapeutic effects on parkinsonian model of rats: focusing on neuroprotective effects of stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha. BMC Neurosci. 2010;11:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-11-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Park BN, Kim JH, Lee K, Park SH, An YS. Improved dopamine transporter binding activity after bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell transplantation in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: small animal positron emission tomography study with F-18 FP-CIT. Eur. Radiol. 2015;25:1487–1496. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3549-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cerri S, et al. Intracarotid infusion of mesenchymal stem cells in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease, focusing on cell distribution and neuroprotective and behavioral effects. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2015;4:1073–1085. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hanson LR, Frey WH., II Intranasal delivery bypasses the blood-brain barrier to target therapeutic agents to the central nervous system and treat neurodegenerative disease. BMC Neurosci. 2008;9:S5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-9-S3-S5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ruigrok MJ, de Lange EC. Emerging insights for translational pharmacokinetic and pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic studies: towards prediction of nose-to-brain transport in humans. AAPS J. 2015;17:493–505. doi: 10.1208/s12248-015-9724-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Danielyan L, et al. Intranasal delivery of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells, macrophages, and microglia to the brain in mouse models of Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. Cell Transpl. 2014;23:S123–S139. doi: 10.3727/096368914X684970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Salama M, et al. Effect of intranasal stem cell administration on the nigrostriatal system in a mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017;13:976–982. doi: 10.3892/etm.2017.4073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Riecke J, et al. A meta-analysis of mesenchymal stem cells in animal models of Parkinson’s disease. Stem Cells Dev. 2015;24:2082–2090. doi: 10.1089/scd.2015.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Gugliandolo A, Bramanti P, Mazzon E. Mesenchymal stem cell therapy in Parkinson’s disease animal models. Curr. Res. Transl. Med. 2017;65:51–60. doi: 10.1016/j.retram.2016.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Durand, N., Russell, A. & Zubair, A. C. Effect of comedications and endotoxins on mesenchymal stem cell secretomes, migratory and immunomodulatory capacity. J. Clin. Med.8, 10.3390/jcm8040497 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 139.Le Blanc K, Mougiakakos D. Multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells and the innate immune system. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2012;12:383–396. doi: 10.1038/nri3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Yin JQ, Zhu J, Ankrum JA. Manufacturing of primed mesenchymal stromal cells for therapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2019;3:90–104. doi: 10.1038/s41551-018-0325-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Wang Y, Chen X, Cao W, Shi Y. Plasticity of mesenchymal stem cells in immunomodulation: pathological and therapeutic implications. Nat. Immunol. 2014;15:1009–1016. doi: 10.1038/ni.3002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Huang P, et al. Mechanism of mesenchymal stem cell-induced neuron recovery and anti-inflammation. Cytotherapy. 2014;16:1336–1344. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Kalluri, R. & LeBleu, V. S. The biology, function, and biomedical applications of exosomes. Science367, 10.1126/science.aau6977 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 144.Reiner AT, et al. Concise review: developing best-practice models for the therapeutic use of extracellular vesicles. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017;6:1730–1739. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Xin H, et al. Systemic administration of exosomes released from mesenchymal stromal cells promote functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity after stroke in rats. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 2013;33:1711–1715. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2013.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Zhang Y, et al. Effect of exosomes derived from multipluripotent mesenchymal stromal cells on functional recovery and neurovascular plasticity in rats after traumatic brain injury. J. Neurosurg. 2015;122:856–867. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS14770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Yuan, Q., Li, X., Zhang, S., Wang, H. & Wang, Y. Extracellular vesicles in neurodegenerative diseases: insights and new perspectives. Genes Dis.10.1016/j.gendis.2019.12.001 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 148.Jarmalaviciute A, Tunaitis V, Pivoraite U, Venalis A, Pivoriunas A. Exosomes from dental pulp stem cells rescue human dopaminergic neurons from 6-hydroxy-dopamine-induced apoptosis. Cytotherapy. 2015;17:932–939. doi: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2014.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Alvarez-Erviti L, et al. Delivery of siRNA to the mouse brain by systemic injection of targeted exosomes. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:341–345. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Wiest, E. F. & Zubair, A. C. Challenges of manufacturing mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles in regenerative medicine. Cytotherapy10.1016/j.jcyt.2020.04.040 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 151.Xu M, Shaw G, Murphy M, Barry F. Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stromal cells are functionally and genetically different from bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stromal cells. Stem Cells. 2019;37:754–765. doi: 10.1002/stem.2993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Jung Y, Bauer G, Nolta JA. Concise review: Induced pluripotent stem cell-derived mesenchymal stem cells: progress toward safe clinical products. Stem Cells. 2012;30:42–47. doi: 10.1002/stem.727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Nakagawa M, Takizawa N, Narita M, Ichisaka T, Yamanaka S. Promotion of direct reprogramming by transformation-deficient Myc. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:14152–14157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009374107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Sabapathy V, Kumar S. hiPSC-derived iMSCs: NextGen MSCs as an advanced therapeutically active cell resource for regenerative medicine. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2016;20:1571–1588. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Lu L, et al. Therapeutic benefit of TH-engineered mesenchymal stem cells for Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. Brain Res. Protoc. 2005;15:46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Xiong N, et al. VEGF-expressing human umbilical cord mesenchymal stem cells, an improved therapy strategy for Parkinson’s disease. Gene Ther. 2011;18:394–402. doi: 10.1038/gt.2010.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Glavaski-Joksimovic A, et al. Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor-secreting genetically modified human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote recovery in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:2669–2681. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]