Abstract

Chromosome segregation is mediated by spindle microtubules that attach to the kinetochore via dynamic protein complexes, such as Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1 and ch-TOG during mitotic metaphase. While experimental studies have previously shown that these proteins and protein complexes are all essential for maintaining a stable kinetochore-microtubule (kMT) interface, their exact roles in this mitotic metaphase remains elusive. In this study, we employed experimental and computational methods in order to characterize how these proteins can strengthen kMT attachments in both nonload-bearing and load-bearing conditions, typical of prometaphase and metaphase, respectively. Immunofluorescence staining of HeLa cells showed that the levels of Ska and Cdt1 significantly increased from prometaphase to metaphase, while levels of the Ndc80 complex remained unchanged. Our new computational model showed that by incorporating binding and unbinding of each protein complex coupled with a biased diffusion mechanism, the displacement of a possible complex formed by Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 is significantly higher than that of Ndc80 alone or Ndc80-Ska. In addition, when we incorporate Ndc80/ch-TOG in the model, rupture force and time of attachment of the kMT interface increases. These results support the hypothesis that Ndc80-associated proteins strengthen kMT attachments, and that the interplay between kMT protein complexes in metaphase ensures stable attachments.

Introduction

During cell division, stable attachments between the kinetochores of the chromosomes and spindle microtubules are essential for ensuring accurate segregation of the genetic material. In metaphase and anaphase, microtubules undergo structural changes via lengthening and shortening of tubulin protofilaments that generate forces at the kinetochore-microtubule (kMT) interface (Jennifer G. DeLuca & Musacchio, 2012; Jeyaprakash et al., 2012). In metaphase, the G-protein pathway activates pulling forces on the mitotic spindle to enable the alignment of chromosomes at the metaphase plate (Grill, Gönczy, Stelzer, & Hyman, 2001; Grill, Howard, Schäffer, Stelzer, & Hyman, 2003). Directional motility of chromosomes driven by kinetochore motors, such as dynein and CENP-E and chromokinesins that bind to chromosome arms, also contribute to chromosome congression and alignment (Maiato, Gomes, Sousa, & Barisic, 2017). Remarkably, kMT attachments remain robust and withstand tension to avoid erroneous segregation. However, the mechanism of how kinetochores remain associated to dynamic microtubule ends under tension during anaphase and metaphase remains elusive.

In metaphase, kMT attachments require several proteins and protein complexes, including Ndc80, Ska1, Cdt1 and ch-TOG (G. Alushin & Nogales, 2011; Jennifer G. DeLuca & Musacchio, 2012; Lampert & Westermann, 2011; Takeuchi & Fukagawa, 2012). These protein factors can broadly be generalized as microtubule-associated proteins (MAPs) at kinetochores that possess the ability to bind to spindle microtubules during metaphase. They are able to undergo dynamic cycles of binding, diffusion and unbinding along tubulin protofilaments (Agarwal et al., 2018; G. M. Alushin et al., 2010; Cooper & Wordeman, 2009; Gestaut et al., 2008; Jeyaprakash et al., 2012; Powers et al., 2009; Spittle, Charrasse, Larroque, & Cassimeris, 2000; Westermann et al., 2006). The Ndc80 complex is the major protein component of the kMT interface and creates a direct link between kinetochores and microtubules (Cheeseman, Chappie, Wilson-Kubalek, & Desai, 2006). Affinity and avidity regulate Ndc80’s binding rates (Davis et al., 2018), while phosphorylation of Aurora B kinase regulates its unbinding rates (K. F. DeLuca et al., 2018; Zaytsev et al., 2015), resulting in a biased diffusion mechanism with diffusion coefficients that range from D = 0.018 m2·s−1 to D = 0.03 μm2·s−1 (Powers et al., 2009; Umbreit et al., 2012). Ska1 and Cdt1 bind to Ndc80 and form load-bearing attachments between Ndc80 and tubulin protofilaments (Cheeseman et al., 2001; Davis et al., 2018; Hanisch, Silljé, & Nigg, 2006; Schmidt et al., 2012; Welburn et al., 2009). Ska1 and Cdt1 diffuse along microtubules with average diffusion rates of D = 0.09 μm2·s−1 and D = 0.16 μm2·s−1, respectively (Agarwal et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2012). The Ska complex strengthens Ndc80 ability to track microtubules ends by dampening chromosome motion to promote accurate segregation (Cheerambathur et al., 2017; Schmidt et al., 2012). Cdt1’s binding affinity for microtubules is also controlled by phosphorylation of Aurora B kinase (Agarwal et al., 2018; Dileep Varma et al., 2012). An additional protein, ch-TOG, a non-motor protein complex that organizes spindle poles (Gergely, Draviam, & Raff, 2003), has been recently found to be critical in load-bearing kMT attachments. Experiments using optical traps showed that ch-TOG’s activity is tension-dependent and stabilizes kMT attachments (Miller, Asbury, & Biggins, 2016).

Previous studies have collectively led to the idea that Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1 and ch-TOG are all critical for stabilizing kMT attachments during metaphase. However, we still lack a clear understanding of the precise roles played by these individual factors and/or how their interplay contributes to kMT attachment stability. An interesting hypothesis is that these proteins directly strengthen the kinetochore-microtubule interface by forming additional connections between the Ndc80 complex and the microtubule (Davis et al., 2018). However, since these proteins dynamically form and break their connections with tubulin protofilaments, while diffusing on microtubules, a synergy between their activities is likely to exist (Miller et al., 2016; Schmidt et al., 2012). Two models have been previously proposed in order to understand how multiple proteins at kMT attachments withstand tension: the ring model and the fibrils model. According to the ring model, tension from dynamic microtubules slides a ring of proteins (Koshland, Mitchison, & Kirschner, 1988). In the fibrils model, kinetochores movement is driven by tugging on tightly bound kinetochore protein fibrils (McIntosh et al., 2008). While providing valuable insights into the molecular mechanisms of multiprotein kMT attachments, these models did not directly incorporate parameters of Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1 and ch-TOG. Therefore, a detailed understanding of the individual contributions from these proteins and proteins complexes and/or interplay is currently missing.

In this work, we used high-resolution fluorescence microscopy and computational simulation approaches in order to understand the interplay between kMT proteins in prometaphase and metaphase. We found that load-bearing kMT attachments in metaphase have considerably higher levels of Ska and Cdt1 with respect to non-load-bearing attachments in prometaphase. In order to understand the synergy between the different kinetochore MAPs with Ndc80, we developed a new computational model. We characterized the effect of binding and unbinding from Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1 and ch-TOG on kMT attachment stability. In particular, we used the model to elucidate how binding and unbinding rates of individual protein components, in combination with a biased diffusion mechanism and tension-dependent bond lifetimes, can strengthen kMT attachments. In load-bearing conditions, by increasing the force across the kinetochore-microtubule interface, we also emulated detachment of kMT interfaces. The model showed that combining Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 enhances kMT attachment strength with respect to individual proteins. Using Ndc80/ch-TOG also strengthens the complex with respect to both Ndc80 in isolation or Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1. Taken together, our results provide important mechanistic insights into how critical kMT proteins interplay to withstand tension and ensure accurate chromosome segregation.

Results

Higher levels of Ska and Cdt1 at metaphase as compared to prometaphase kinetochores

We first aimed to address the roles played by kinetochore-microtubule-binding proteins Ska and Cdt1 in the formation of load-bearing attachments by the Ndc80 complex. To analyze the difference in kinetochore localization between a non-load-bearing (kinetochore pairs not attached to spindle microtubules) and a load-bearing (bioriented kinetochores attached to spindle microtubules from opposite spindle poles) state, we assayed the kinetochore levels of Ska and Cdt1 in prometaphase and metaphase mitotic cells respectively. We found there was considerable increase in the kinetochore levels of both these proteins from prometaphase to metaphase (Fig. 1 C-F; (Agarwal et al., 2018; Chan, Jeyaprakash, Nigg, & Santamaria, 2012; Hanisch et al., 2006; Dileep Varma et al., 2012). There was a robust 4-fold increase in Ska levels in metaphase compared to prometaphase kinetochores (Fig. 1 C, D; (Chan et al., 2012; Hanisch et al., 2006)). The increase in levels of Cdt1 during metaphase was consistent but marginal compared to prometaphase kinetochores (Fig. 1 E, F). The kinetochore levels of the Hec1 subunit of the Ndc80 complex, as expected, did not vary much between prometaphase and metaphase (Fig. 1 A, B; (Gascoigne & Cheeseman, 2013; Lin, Chen, Wu, & Lee, 2006)).

Figure 1:

Kinetochore localization of microtubule-binding proteins that are required for stabilizing end-on kinetochore-microtubule attachments in fixed mitotic HeLa cells. (A) Immunofluorescence staining of mitotic cells for the Hec1 subunit of the Ndc80 complex shown alongside another kinetochore marker, Zwint1 in either prometaphase (top panel) or metaphase (bottom panel). (B) Comparative quantification of Hec1 intensity at kinetochores in prometaphase vs metaphase cells from A. n = 75 from 5 cells. (C) Immunofluorescence staining of mitotic cells for the Ska3 subunit of the Ska complex shown alongside kinetochore markers, anti-CREST antiserum (ACA) in prometaphase (top panel) or Hec1 in metaphase (bottom panel), as indicated. (D) Comparative quantification of Ska3 intensity in prometaphase vs metaphase cells from C. n=120 from 5 cells. (E) Immunofluorescence staining of mitotic cells for Cdt1 shown alongside kinetochore markers, anti-CREST antiserum (ACA) in prometaphase (top panel) or Hec1 in metaphase (bottom panel), as indicated. (F) Comparative quantification of Cdt1 intensity in prometaphase vs metaphase cells from E. n=120 from 5 cells.

Model calibration

We calibrated the model based upon experimentally detected parameters for binding, unbinding and diffusion of Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 (Agarwal et al., 2018; Schmidt et al., 2012; Umbreit et al., 2012). The model treats each protein as a 1D single-point particle (see flow chart in Fig 2 and schematics in Fig. 3A). Initially, each protein was simulated in isolation and undergoes biased diffusion towards the microtubule minus-ends, with probability p to take a step towards the minus-end, and q for taking a step towards the plus-end, with p = 0.6 and q = 0.4 (Fig. 3A). In the case of unbiased diffusion D~Δx2, but in the case of biased diffusion a fraction of the original displacement, corresponding to (p − q)Δx, is turned to drift. Therefore, we renormalized the unbiased diffusion by removing this fraction, which is equivalent to considering the variance of the displacement instead of its squared mean. We systematically varied the protein kon and koff from 0 to 0.6 s−1, and estimated coefficients for biased diffusion as:

where is the unbiased diffusion coefficient, p2 + q2 = 1 − 2pq, Δt = 300 s is the observation time over which the displacement occurs.

Figure 2. Flow chart of the computational model.

The model implements a Kinetic Monte Carlo algorithm, where state and position of each particle are updated at each time step. All particles are initially in the unbound state and at position 0. At each time step: their binding probability is evaluated; then, for the bound particles, unbinding probability is updated; bound particles can move; last, particles’ positions are updated. In the flow chart, black boxes indicate updates in particles’ states and green boxes refer to changes in position. Red is for conditional statements

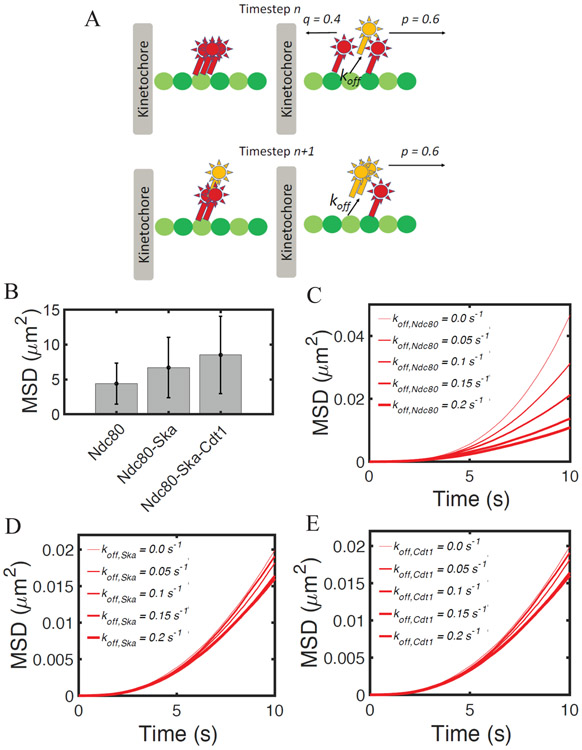

Figure 3. Computational model of kMT attachments incorporating the Ndc80-accessory proteins.

(A) Schematics of the computational model, incorporating binding, unbinding and biased diffusion of Ndc80-associated proteins Ska and Cdt1. (B) Heatmap showing the diffusion coefficient of a protein complex undergoing biased diffusion as a function of kon and koff. Parameter values of kon and koff for Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 are evaluated based on previous in vitro characterization of the complex dynamics on immobilized microtubules. Simulations are run for 300 s and data are averages between 1000 independent runs. (C) Mean squared displacement of Ndc80 at 1 s of simulation using different values of koff, in order to mimic the effect of phosphomimetic Ndc80 mutants. Results are computed as averages from 10,000 independent runs. (D) Heat map of Mean Square displacement (MSD) of the Ndc80-Ska complex at 10 s of simulation, varying the number of Ndc80 and by systematically changing Ska kon. Results are computed as averages from 200 independent runs.

In the parameter space defined by kon and koff, we identified diffusion coefficients for Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 (Fig. 3B) and compared them with those extracted from previous in vitro experiments. When a binding rate was not available from experiments, we identified the D corresponding to the known unbinding rate and used the model to predict the binding rate. For Ndc80, using koff = 0.25 s−1 and diffusion coefficient in the range D = 0.018-0.03 μm2·s−1, as extracted from previous Total Internal Fluorescence Microscopy (TIR-FM) experiments (Schmidt et al., 2012; Umbreit et al., 2012), we found kon = 0.05 s−1. For Ska, we used unbinding rate koff = 0.2 s−1 , binding rate kon = 0.1 s−1, and diffusion coefficient D = 0.09 μm2·s−1 (Schmidt et al., 2012). For Cdt1, higher binding and unbinding rates with respect to both Ndc80 and Ska were used: koff = 0.4 s−1 and kon = 0.25 s−1. Accordingly, Cdt1 resulted in a higher average diffusion coefficient: D = 0.16 μm2/s (Fig. 3B), consistent with experimental data (Agarwal et al., 2018).

Model validation

We tested if the predictive performance of our model deteriorates substantially when applied to data that were not used in the calibration. For this, we used systems of multiple proteins and evaluated kMT attachment stability. We used the model to simulate: (i) Ndc80 phosphorylation (Zaytsev et al., 2015); (ii) Ska binding microtubules without Ndc80 (Schmidt et al., 2012).

Since kon for different numbers of Ndc80 phosphomimetic substitutions does not substantially change (Zaytsev et al., 2015), to mimic Ndc80 phosphorylation we systematically varied Ndc80 koff and evaluated the mean squared displacement, MSD, of the complex. For 10 s of simulation, increasing Ndc80 koff from 0. to 0.2 s−1 decreases MSD by more than 50% (Fig. 3C). This result is quantitatively consistent with data from TIR-FM analysis of Ndc80 phosphomimetic mutants (Zaytsev et al., 2015).

Ska binding rate depends upon whether the protein is in isolation or in combination with Ndc80, increasing from 0.02 s−1 to 0.16 s−1, when forming a complex (Schmidt et al., 2012). When multiple proteins are used in the model, their connectivity is maintained by assigning to all of them (both bound proteins and unbound proteins) the position of the complex. At the beginning of each time step, the position of the complex, xcomplex, corresponds to the average position of all bound proteins Nbound (see schematic representation in Fig. 4A), as:

Figure 4. The interplay between Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 ensures stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment in non-load-bering conditions.

(A) Schematics of the model with a complex of multiple proteins. At each time step, the position of the proteins is calculated as the average position of the bound proteins. Assuming that different proteins move in opposite directions at timestep n (upper panels), their position is updated at timestep n+1 (lower panels). Only after this update in position, the model evaluates binding, unbinding and diffusion. (B) Average Mean square displacement (MSD) of the Ndc80 complex at 300 seconds of simulations. Data are computed from 1,000 independent runs. Error bars denote standard deviation from the mean. MSD of the Ndc80 complex, including Ska and Cdt1, at 10 s of simulations, for different values of (C) koff,Ndc80, (D) koff,ska or (E) koff,cdt1. Data are computed from 5,000 independent runs.

We evaluated the accuracy of our model by using a complex formed by Ndc80-Ska. We characterized how the MSD of the complex changes by varying Ndc80 concentration and Ska kon. For all Ska kon, MSD of the Ndc80-Ska complex increases in proportion to Ndc80 concentration (Fig. 3D), consistent with previous experiments (Zaytsev et al., 2015). Without Ndc80, variations of kon,Ska minimally affected MSD. Co-sedimentation assays had previously also shown that Ndc80 increases Ska affinity in a dose-dependent manner, up to 8-fold (Zaytsev et al., 2015), consistent with our modeling results.

Binding and unbinding of Ndc80-associated proteins stabilize kMT connections in non-load-bearing conditions

In order to gain insights into the processivity of a possible complex formed by Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1, we next used the model in order to test how variations of each component’s koff reflect on the displacement of Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1. The average MSD of Ndc80 alone is about 4 μm2 in 300 s. In the same amount of time, a complex formed by Ndc80-Ska or Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 presented an average MSD of about 7 μm2 or 8.5 μm2, respectively (Fig. 4B). These results demonstrate that the higher binding rate and smaller unbinding rate of Ska with respect to Ndc80 (Fig. 3B) significantly increase the displacement of Ndc80-Ska or Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 with respect to only Ndc80 (Fig. 4B). These results are also consistent with analysis from TIR-FM and co-sedimentation assays of Ndc80-Ska (Schmidt et al., 2012), and with the in vivo analysis of Cdt1 in HeLa cells (Agarwal et al., 2018; Dileep Varma et al., 2012), reporting that both Ska and Cdt1 stabilize kMT attachments. Results from TIR-FM had observed a 1.5-fold change in fluorescence intensity between Ndc80 alone and Ndc80-Ska (Schmidt et al., 2012). From our model, the difference in displacement between Ndc80 and Ndc80-Ska is about 1.5-fold (Fig. 4B).

Aurora B kinase phosphorylation of the Ndc80 complex can affect its kinetic rates (Zaytsev et al., 2015). Mutants for Aurora B kinase phosphorylation sites of Hec1, such as Ser4, Ser5, Ser8, Ser15, Ser44, Thr49, Ser55, Ser62 and Ser69 control the binding of Ndc80 to microtubules (K. F. DeLuca et al., 2018; Zaytsev et al., 2015). In order to gain more insights into the effect of Aurora B on the processivity of a possible complex formed by Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1, we tested how variations of each component’s koff reflected on the displacement of the complex Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1. By systematically increasing Ndc80 koff, from 0.0 s−1 to 0.4 s−1, a decrease in the complex MSD is observed, from about 0.05 μm2 to 0.01 μm2, in 10 s of simulation (Fig. 4C). Increasing Ska or Cdt1 koff within the same range decreases the complex MSD from 0.02 μm2 to 0.015 μm2 in 10 s (Fig. 4D-E). This result indicates that phosphorylation of Ska and Cdt1 can alter the complex processivity.

Role of Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 in kMT attachment in load-bearing conditions

Next, we wanted to understand the properties of the various kinetochore MAPs in assisting the Ndc80 complex to form load-bearing kMT attachments. We first carried out immunofluorescence staining experiments to localize Ska and Cdt1 in mitotic metaphase HeLa cells. Contrary to the observed kinetochore staining in paraformaldehydefixed cells, when we fixed the cells with methanol, we were able to discern clear mitotic spindle microtubule and spindle pole staining for both Ska 3 (top panel) and Cdt1 (bottom panel) (Fig. 5A, (Agarwal et al., 2018; Hanisch et al., 2006)). Clear Ska and Cdt1 staining on individual microtubules, however, was often difficult to discern (data not shown). This staining pattern for these MAPs is distinctly different from that of the Ndc80 complex, which localizes to mitotic kinetochores and forms the core attachment sites for spindle microtubules in metaphase (Deluca et al., 2004; Cheeseman et al., 2006). This also suggests that the Ndc80 complex is assisted by Ska and Cdt1 to form load-bearing kMT attachments during metaphase.

Figure 5. Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 increase kinetochore-microtubule rupture force and attachment time in load-bearing conditions.

(A) Spindle microtubules localization of the Ska3 subunit of the Ska complex (red, top panel) or Cdt1 (red, bottom panel) in methanol-fixed (bottom) metaphase HeLa cells. Microtubules are in green while DAPI/chromosomes are in blue. (B) Implemented bond lifetimes for Ndc80, Ska, and Cdt1. (C) Average MSD of the Ndc80 complex at 300 seconds of simulations. Error bars denote standard deviation from the mean. Data are computed from 100 independent runs. (D) Average rupture force (force at which all proteins become unbound) evaluated for Ndc80, Ndc80-Ska, and Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 versus the number of MT protofilaments. (E) Average attachment lifetime for Ndc80, Ndc80-Ska, and Ndc80-SkaCdt1 versus the number of MT protofilaments. Data are averages from 1,000 independent runs.

In order to test the effect of physiologically relevant loads on the stability of kMT attachments, we incorporated in the model explicit forces acting on bound MAPs. The model assumes that Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 behave as slip bonds, and therefore have unbinding rates dependent on the tension on the bond (Fig. 5B). Unloaded bond lifetime for Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1 was given by the inverse of the corresponding binding rate at zero force (Fig. 5B): τNdc80 = 4 s ; τSka = 5 s; τCdt1 = 2.5 s (Fig. 5B). The average MSD of Ndc80 alone is about 18 nm2 in 300 s, while Ndc80-Ska and Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 had an average MSD about 20 and 30 nm2, respectively (Fig. 5C). The rupture force, corresponding to the load under which no MAP is bound, increased in proportion to the number of simulated microtubule protofilaments for Ndc80, Ndc80-Ska and Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1. In particular, rupture force was between 0.1-0.5 pN for Ndc80, and up 7 to 8-fold higher using Ndc80-Ska and Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1, respectively (Fig. 5D). Similarly, time of attachment, corresponding to the total time during which at least one protein from the complex is bound before rupture, increased with microtubule protofilament concentration (Fig. 5E). This time was lower using Ndc80 than Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 (Fig. 5E). In vitro experiments based on laser trapping-based force clamps (Powers et al., 2009) had shown that for Ndc80, a tension in the range of 0.5-2.5 pN generates unbinding, consistent with our modeling results. The values of rupture force and time of attachment for 13 tubulin protofilaments correspond to those for a single microtubule. Each microtubule protofilament is bound to a maximum of two Ndc80 proteins, and one of each of the other MAPs (Ska and Cdt1). In the model, we control the number of simulated microtubule protofilaments (and therefore the number of microtubules) by adjusting in the input the amount and type of simulated proteins.

Role of ch-TOG in kMT attachments using load-bearing conditions

Finally, we were interested in understanding the role of the kinetochore MAP ch-TOG in assisting the Ndc80 complex for the formation of load bearing kMT attachments. We first expressed a GFP-tagged ch-TOG construct in HeLa cells to characterize its localization in mitotic cells. Paraformaldehyde fixation revealed clear kinetochore localization of ch-TOG in metaphase cells (Fig. 6A). However, we were not able to discern a difference between the kinetochore staining of ch-TOG in prometaphase as compared to metaphase cells (data not shown). On the other hand, fixing metaphase cells with methanol showed clearly definable mitotic spindle staining, with bright spindle pole staining and milder kinetochore staining (Fig. 6A). This staining pattern was reminiscent of Ska and Cdt1 spindle and spindle pole staining after methanol fixation of metaphase cells. This localization pattern is consistent with observation that ch-TOG serves as an accessory factor that enables the Ndc80 complex to form load-bearing kMT attachments during metaphase (Miller et al., 2016).

Figure 6. ch-TOG significantly enhances rupture force and attachment time via tension-dependent mechanisms.

(A) Localization of GFP-tagged ch-TOG to kinetochores (green, top panel) in paraformaldehyde-fixed and to spindle microtubules (green, bottom panel) in methanol-fixed metaphase HeLa cells. (B) Average attachment time for Ndc80 and Ndc80/ch-TOG versus number of MT protofilaments. Data are extracted from 1,000 independent runs. (C) Average rupture force for Ndc80 and Ndc80/ch-TOG versus the number of tubulin protofilaments. Results are computed from 1,000 independent runs. (D) Implemented bond lifetimes for ch-TOG. Bond lifetime versus force relation for varying τMAX are tested. (E) Heatmap of average attachment time by systematically varying the number of microtubules and τMAX. SE is below 1 min for all τMAX. (F) Heatmap of average rupture force by systematically varying number of microtubules and τMAX. SE is below 0.3 pN for all τMAX.

To better understand the contribution of ch-TOG for forming robust kMT attachments, we incorporated in our model an additional protein component that directly stabilizes attachments in a force-dependent way. As for the other Ndc80-associated proteins, ch-TOG undergoes biased diffusion, binding and unbinding along tubulin protofilaments, but follows catch bond dynamics as detected from previous optical traps experiments (Miller et al., 2016). Over the course of the simulations, ch-TOG maintains its attachment to the kMT by sharing the total load, Ftot, with other bound proteins. With respect to Ndc80 alone, Ndc80/ch-TOG remains attached about 5-fold longer (Fig. 6B). Rupture force also increases up to more than 5 pN, for high number of tubulin protofilaments (Fig. 6C). Since experimental data estimating the force versus bond lifetime of individual ch-TOG proteins is not available, we tested how catch bond dynamics with different τMAX (Fig. 6D) affect attachment time and rupture force at varying microtubule concentration. The model shows that by increasing τMAX from 30 s to 440 s, time of kMT attachment and rupture force vary significantly (Fig. 6E-F). In addition, microtubule concentration is positively correlated with kMT attachment time and rupture force (Fig. 6E-F).

Discussion

The ability of cells to separate chromosomes during mitosis is critical to several aspects of their physiology and pathology, including normal tissue development, aneuploidy and cancer. In this study, we demonstrated that a dynamic interplay between protein complexes forming links between spindle microtubules and chromosomal kinetochores is required to ensure stable attachments between the two cellular structures and ensure accurate chromosome segregation. We showed that the levels of Ska and Cdt1 increase from prometaphase to metaphase (Fig. 1), supporting the hypothesis that these Ndc80-accessory proteins functionally complement kMT attachments. We tested this hypothesis by developing a computational model of kMT attachments that incorporate binding, unbinding and biased diffusion of individual protein complexes. The model showed that accessory Ndc80-binding proteins increase kMT attachment time and rupture force in load-bearing conditions (Fig. 5C-D). In addition, incorporating in the model the contribution of ch-TOG further stabilizes kMT attachments due to its catch bond dynamics (Fig. 6B-C). These effects result from binding, biased diffusion and tension-dependent unbinding of the protein complexes.

Previous studies of kMT attachments have shown that an increase in Ndc80 surface density results in the strengthening of kMT attachments, as more Ndc80 complexes can reach tubulin protofilaments, bind them and withstand mitotic forces (Davis et al., 2018). Accordingly, Ndc80 knockdowns in vivo cause severe defects in kMT attachments (J. G. DeLuca, 2004; McCleland et al., 2004; D. Varma & Salmon, 2013; Wei, Al-Bassam, & Harrison, 2007; Wigge & Kilmartin, 2001). Our model is consistent with these results showing that an increase in Ndc80 density increases the displacement of the Ndc80-Ska complex (Fig. 3D). Moreover, previous experiments have shown that Ska and Cdt1 are recruited to kinetochores by Ndc80 to provide more stability to attachments (Gaitanos et al., 2009; Jeyaprakash et al., 2012; Raaijmakers, Tanenbaum, Maia, & Medema, 2009; Welburn et al., 2009), and that ch-TOG is also needed to ensure load-bearing properties to the complex. Loss of Ska in vivo delays mitotic progression and it has been associated with chromosome congression failure and mitotic cell death (Gaitanos et al., 2009; Welburn et al., 2009). Accordingly, deletion of Ska prevents it from strengthening Ndc80 complex-based attachments, as revealed by approaches based on force measurements employing optical tweezers (Davis et al., 2018). Our model shows that the presence of Ska allows the complex to diffuse more than with Ndc80 in isolation, both in non-load-bearing and load-bearing conditions (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5C). In addition, in load-bearing conditions, Ska enhances the force required for kMT attachment rupture of about 5-fold relative to Ndc80 alone. By adding Cdt1, a smaller, but significant enhancement for Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1 attachment strength is detected with respect to Ndc80-Ska, in both non-load-bearing and load-bearing conditions (Fig. 4B and Fig. 5D). When ch-TOG is incorporated in the model, rupture force is significantly higher than with Ndc80-Ska or Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1, owing to its catch bond dynamic (Fig. 6C). This result is consistent with findings from previous in vitro reconstitution systems, showing ch-TOG’s direct role in stabilizing kMT attachments via its tension-dependent bond dynamics (Miller et al., 2016).

This study contributes to the advancement of our understanding of the interplay between Ndc80-associated proteins, specifically Ska, Cdt1 and ch-TOG, in strengthening kMT attachments during metaphase. Previous theoretical models have proposed that ring, sleeves or fibrils containing ensembles of kMT proteins form multiple weak attachments with dynamic microtubules (Hill, 2006; Koshland et al., 1988; McIntosh et al., 2008). While these previous models provide insights into important mechanisms by which kMT remain attached to dynamic microtubules, they do not incorporate parameters specific to Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1 or ch-TOG, such as tension-dependent bond dynamics for these proteins. Our model directly incorporates tension-dependent bonds dynamics for Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1, and ch-TOG. By testing different conditions of proteins densities and levels of binding and unbinding under load, our model allows us to combine contributions from the various MAPs and study how the kMT complex responds to physiologically relevant tensions. In this way, our model allows us to evaluate the synergistic effect of Ndc80-associated metaphase proteins on strengthening of the kMT interface. Furthermore, different from the sleeve and ring models (Koshland et al., 1988; McIntosh et al., 2008), where the kMT proteins are rigidly connected, our model treats binding and unbinding of Ndc80-associated proteins independently.

The results from our model suggest that a possible complex, Ndc80-Ska-Cdt1, in prometaphase is highly diffusive (higher levels of displacement) which agrees with the notion that kinetochore association with microtubules are dynamic and amenable to sliding motility on microtubules in non-load-bearing conditions. The formation of a load-bearing network between these proteins in metaphase enables a robust, processive interaction with microtubule-ends. This reduces the ability for random diffusion while at the same time enabling oscillatory behavior of kinetochores coupled to microtubule polymerization and depolymerization. This processive complex also enables the dynamic coupling of Ndc80 to plus-ends to prevent kMT detachment and chromosome loss during metaphase and anaphase.

A precise understanding of the mechanisms underlying kMT strengthening via various protein complexes was previously missing due to limitations in spatial and temporal resolutions of current experimental approaches. Here, we developed a new computational model of kMT attachment dynamics incorporating the contributions from Ndc80-associated protein complexes. Our model revealed that the mechanisms of binding, biased diffusion and load-dependent unbinding of Ndc80-associated proteins are sufficient to explain stabilization of kMT attachments. It will be interesting to add a cooperativity factor of protein binding to further understand the roles and synergistic properties of these different protein complexes in stabilizing the kMT interface. In the future, we will incorporate this feature and evaluate how kMT attachments respond to tension, when assuming cooperativity between dynamic proteins. In addition, we will test conditions when Ndc80-associated protein complexes also affect microtubule dynamics. Moreover, it will be interesting in the future to test if the MAPs that assist Ndc80 function form sub-complexes with Ndc80 to provide spatial and temporal control for robust kMT attachment formation. Further, it will be an exciting prospect to probe the nature of structures formed by these complexes on microtubules in an effort to understand how they precisely contribute to these functions. For this purpose, experiments combined with simulations based on all-atom and molecular modeling could help understanding kMT complexes’ structures and functions.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and transfection

HeLa cells were cultured and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified eagle’s medium (DMEM, Life Technologies) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (Life Technologies), using standard cell culture procedures (Agarwal et al., 2018). For transfection experiments involving ch-TOG-GFP, cells were seeded overnight onto 22 mm glass coverslips to achieve ~ 60-70 % confluency. The cells were then transfected with 0.5 μg of plasmid encoding ch-TOG-GFP (a generous gift from Dr. Stephen Royle at University of Warwick, UK) using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were fixed 48 h post-transfection and processed for immunofluorescence microscopy.

Cell fixation and immunofluorescence staining

The cells were fixed using ice-cold methanol for 6 mins or 4 % formaldehyde for 20 mins as indicated in the figures or figure legends. For Cdt1 spindle microtubule staining, cells were fixed in ice-cold methanol only for 3 mins. Following fixation, the cells were immune-stained with combinations of different primary antibodies, as indicated in the figures or figure legends. The primary antibodies used in the study include Hec1 monoclonal (1:400, ab3613, clone 9G3, Abcam), Zwint1 polyclonal (1:400, A300-781A, Bethyl), Tubulin monoclonal (1:500, T9026, clone DM1A, Sigma), anti-CREST antiserum (1:500, HCT0100, Immunovision, Inc.) and Cdt1 polyclonal (1:50, H300, Santacruz Biotechnologies). The Rabbit polyclonal antibody against Ska3 used at 1:200 dilution was a kind gift from Dr. Gary Gorbsky (Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, University of Oklahoma). 4,6-diamino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) dihydrochloride (1:10,000, Life Technologies) was used to counterstain the nucleus/chromosomes. Alexa Fluor 488-, Rhodamine Red-X-, or Cy5-labeled donkey secondary antibodies were obtained from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc. and used at a dilution of 1:200.

Spinning-disc confocal microscopy

Following immunostaining, the coverslips were mounted on to glass slides using ProLong Gold Antifade reagent (Invitrogen). For image acquisition, 3D stacks were obtained sequentially at 200 nm steps along the z-axis through the cell using a high-resolution inverted microscope (Eclipse TiE; Nikon) equipped with a spinning disk (CSU-X1; Yokogawa Corporation of America), an Andor iXon Ultra888 EMCCD camera, and an x100 1.4 NA Plan-Apochromatic DIC oil immersion objective (Nikon). The images were acquired and processed using the NIS elements Software from Nikon.

Computational model of kMT attachment dynamics

In order to understand the interplay between Ndc80, Ska, and Cdt1 for stabilizing kinetochore-microtubule attachments, we developed a computational model. The use of a computational approach allowed us to directly incorporate the different protein components, isolate their contributions, and characterize their synergistic effects on the emergent dynamics of kMT attachments. In the model, Ndc80, Ska1, Cdt1 and ch-TOG are explicitly defined by a position along a tubulin protofilament and exists in two states, bound or unbound. When in the bound state, the protein moves with biased direction towards the MT pointed end at a specific rate. It can also unbind depending on its unbinding rate, which determines its unbinding probability. All model parameters, including binding and unbinding rates, diffusion coefficients, and characteristic lifetimes of bound states, are taken from previous experiments. The developed algorithm updates position and state of each protein individually, while maintaining their connectivity within an integrated attachment interface (see flow chart in Fig. 2). Initially, all proteins are considered to be at the tip of tubulin protofilaments, at position 0. In each simulation, a specific number of tubulin protofilaments are considered. Assuming that each tubulin protofilament can be bound by a total of 5 MAPs (2 Ndc80 and 1 of each Ndc80-associated proteins, Ska, Cdt1 or ch-TOG), by varying the number of Ndc80, Ska, Cdt1, or ch-TOG, we control the number of protofilaments in the model. Also, considering that 13 tubulin protofilaments form a microtubule, we use the model to simulate different numbers of microtubules. When 26 protofilaments are used, two microtubules are considered and they share the same kMT interface, since the load is distributed among all of the bound proteins in the system. At each time step, each protein’s binding, diffusion and unbinding are evaluated (see flow chart in Fig. 2). As for the output, the model is used to evaluate: (i) displacement of the kMT interface; (ii) time of kMT attachment under tension and (iii) kMT attachment rupture force.

Dynamics of kMT proteins in non-load bearing conditions

We simulated the time evolution of the kMT interface formed by Ndc80, Ska and Cdt1, by developing a computational model based on the Kinetic Monte Carlo approach. According to this approach, a system evolves dynamically from state to state, and these transitions are treated directly. Initially, proteins are in the unbound state. At each time step of the simulation, the probability of binding, Pon, is evaluated, based upon the protein binding rate, kon, as: Pon = kon dt. A uniform random number, u, is then generated and compared with this probability. If Pon > u, then the protein switches to the bound state. Once in the bound state, the protein undergoes biased diffusion, and its position moves 4 nm to either the minus or the plus-end. This displacement corresponds to the typical size of a tubulin monomer and to the Ndc80 spacing within a tubulin protofilament (G. M. Alushin et al., 2010; Zaytsev et al., 2015). To mimic biased diffusion towards the microtubule minus-end, the probability for the protein of taking a step towards the microtubule minus-end was p, while that of taking a step towards the plus-end was q, with p = 0.6 and q = 0.4 (Fig. 3A). The values for p and q were chosen by scanning how different combinations of p and q (with p > q) affected coefficients of biased diffusion (see Fig. S1).

Lastly, for all bound proteins, unbinding is evaluated based upon unbinding probability, Poff, accounting for the unbinding rate, koff, as: Poff = koff dt. At all time steps, before evaluating binding probabilities, the particle’s position is first re-assigned based on the average position of all bound proteins. Then, for the unbound proteins, binding is evaluated; second, for all bound proteins, biased diffusion occurs, and the positions of all proteins are updated; lastly, unbinding is evaluated, and proteins are allowed to switch to the unbound state. We ran simulations for 300 s, which is a physiologically relevant timescale for kMT attachments (Zaytsev, Ataullakhanov, & Grishchuk, 2013). As for the output, the displacement of kMT attachment proteins was evaluated. For this, we calculated the average mean square displacement (MSD) of all particles in the system, relative to their initial position (the model assumes that at the beginning of the simulations all particles are at position 0; when a particle is in the bound state, it moves either towards one direction or the other, along microtubules; each move corresponds to 4nm).

Dynamics of kMT proteins in load-bearing conditions

Our model incorporates load-bearing conditions, where tension acts on the kMT attachment. The model assumes that this tension increases at each time step, and modifies the initial protein unbinding rate, koff,0. Initially, the kMT is unloaded, with null total force, Ftot = 0; then, at each time step, the total force increases randomly and uniformly, with a value in the range 0-0.1 pN. The model assumes that this force is equally distributed on all bound proteins, nb. Therefore, for each i protein in the bound state, the force acting on it is: . As for the non-load-bearing conditions, the basic algorithm evaluates each protein’s state and position, and updates them at every time step, by evaluating binding, diffusion and unbinding. Importantly, for the load-bearing conditions, protein unbinding rates are not constant and depend on the load per protein, Fi. For Fi = 0 pN, unbinding rate corresponds to that used in non-load-bearing conditions, therefore koff,0 = koff. For Fi > 0 pN, unbinding rates depend on the type of bond between the protein and microtubules, whether it is a slip bond (as for Ndc80, Ska, and Cdt1) or catch bond (as for ch-TOG). The following session explains how the unbinding rates change with load.

Slip bond and catch bond dynamics

In slip bonds, bond lifetimes, τ, decrease with increasing tension, Fi (Figure 5B). Accordingly, koff increases under tension. Slip bond dynamics follows a single exponential pathway and the decrease of τ with tension is:

where koff,0 is the unbinding rate at zero force (for Ndc80, koff,0 = 0.25 s−1; for Ska, koff,0 = 0.2 s−1; for Cdt1, koff,0 = 0.4 s−1) and F0 = 3 pN (Civelekoglu-Scholey et al., 2013).

In catch bonds, τ initially increases with increasing tension, followed by a decrease (Figure 6B). The resulting bond pathway has both a strengthening and a weakening pathway. Catch bonds are expressed mathematically as double exponentials, where exponents have different signs: a positive sign for the strengthening pathway and a negating one for the weakening pathway. The positive and negative exponential signs correspond to an initial increase in τ, followed by a decrease:

With increasing force, initially koff decreases (.), then it increases. In the model, parameters for ch-TOG catch bond are calibrated based on (Miller et al., 2016): koff,0 = 1 s−1, F0,1 = 0.43 pN, α = 0.001 s−1, F0,2 = 5 pN.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Model calibration varying parameters for biased diffusion. Heatmap showing the diffusion coefficient of a protein complex undergoing biased diffusion as a function of kon and koff and using p = 0.5 (A), p = 0.6 (B), p = 0.7 (C), p = 0.8 (D). Results are computed as averages from 200 independent runs.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our respective start-up funds from the Department of Bioengineering and the Scientific Computing and Imaging Institute of the University of Utah and the Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, for supporting our research on this project. This work was also supported by NCI grant R00CA178188 to DV. We would like to thank Drs. Gary Gorbsky and Stephen Royle for help with reagents used in the study.

References

- Agarwal S, Smith KP, Zhou Y, Suzuki A, McKenney RJ, & Varma D (2018). Cdt1 stabilizes kinetochore-microtubule attachments via an Aurora B kinase-dependent mechanism. The Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201705127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alushin GM, Ramey VH, Pasqualato S, Ball DA, Grigorieff N, Musacchio A, & Nogales E (2010). The Ndc80 kinetochore complex forms oligomeric arrays along microtubules. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature09423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alushin G, & Nogales E (2011). Visualizing kinetochore architecture. Current Opinion in Structural Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2011.07.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan YW, Jeyaprakash AA, Nigg EA, & Santamaria A (2012). Aurora B controls kinetochore-microtubule attachments by inhibiting Ska complex-KMN network interaction. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheerambathur DK, Prevo B, Hattersley N, Lewellyn L, Corbett KD, Oegema K, & Desai A (2017). Dephosphorylation of the Ndc80 Tail Stabilizes Kinetochore-Microtubule Attachments via the Ska Complex. Developmental Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2017.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman IM, Brew C, Wolyniak M, Desai A, Anderson S, Muster N, … Barnes G (2001). Implication of a novel multiprotein Dam1p complex in outer kinetochore function. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseman IM, Chappie JS, Wilson-Kubalek EM, & Desai A (2006). The Conserved KMN Network Constitutes the Core Microtubule-Binding Site of the Kinetochore. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Civelekoglu-Scholey G, He B, Shen M, Wan X, Roscioli E, Bowden B, & Cimini D (2013). Dynamic bonds and polar ejection force distribution explain kinetochore oscillations in PtK1 cells. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper JR, & Wordeman L (2009). The diffusive interaction of microtubule binding proteins. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TN, Helgeson LA, MacCoss MJ, Asbury CL, Zelter A, & Riffle M (2018). Human Ska complex and Ndc80 complex interact to form a load-bearing assembly that strengthens kinetochore–microtubule attachments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1718553115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca JG (2004). Hec1 and Nuf2 Are Core Components of the Kinetochore Outer Plate Essential for Organizing Microtubule Attachment Sites. Molecular Biology of the Cell. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e04-09-0852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca Jennifer G., & Musacchio A (2012). Structural organization of the kinetochore-microtubule interface. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca KF, Meppelink A, Broad AJ, Mick JE, Peersen OB, Pektas S, … DeLuca JG (2018). Aurora A kinase phosphorylates Hec1 to regulate metaphase kinetochore-microtubule dynamics. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201707160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitanos TN, Santamaria A, Jeyaprakash AA, Wang B, Conti E, & Nigg EA (2009). Stable kinetochore-microtubule interactions depend on the Ska complex and its new component Ska3/C13Orf3. EMBO Journal. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gascoigne KE, & Cheeseman IM (2013). CDK-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion coordinately control kinetochore assembly state. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201301006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gergely F, Draviam VM, & Raff JW (2003). The ch-TOG/XMAP215 protein is essential for spindle pole organization in human somatic cells. Genes and Development. doi: 10.1101/gad.245603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gestaut DR, Graczyk B, Cooper J, Widlund PO, Zelter A, Wordeman L, … Davis TN (2008). Phosphoregulation and depolymerization-driven movement of the Dam1 complex do not require ring formation. Nature Cell Biology. doi: 10.1038/ncb1702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill SW, Gönczy P, Stelzer EHK, & Hyman AA (2001). Polarity controls forces governing asymmetric spindle positioning in the caenorhabditis elegans embryo. Nature. doi: 10.1038/35054572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill SW, Howard J, Schäffer E, Stelzer EHK, & Hyman AA (2003). The distribution of active force generators controls mitotic spindle position. Science. doi: 10.1126/science.1086560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch A, Silljé HHW, & Nigg EA (2006). Timely anaphase onset requires a novel spindle and kinetochore complex comprising Ska1 and Ska2. EMBO Journal. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill TL (2006). Theoretical problems related to the attachment of microtubules to kinetochores. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaprakash AA, Santamaria A, Jayachandran U, Chan YW, Benda C, Nigg EA, & Conti E (2012). Structural and Functional Organization of the Ska Complex, a Key Component of the Kinetochore-Microtubule Interface. Molecular Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koshland DE, Mitchison TJ, & Kirschner MW (1988). Polewards chromosome movement driven by microtubule depolymerization in vitro. Nature. doi: 10.1038/331499a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampert F, & Westermann S (2011). A blueprint for kinetochores - New insights into the molecular mechanics of cell division. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. doi: 10.1038/nrm3133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin YT, Chen Y, Wu G, & Lee WH (2006). Hec1 sequentially recruits Zwint-1 and ZW10 to kinetochores for faithful chromosome segregation and spindle checkpoint control. Oncogene. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maiato H, Gomes A, Sousa F, & Barisic M (2017). Mechanisms of Chromosome Congression during Mitosis. Biology. doi: 10.3390/biology6010013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCleland ML, Kallio MJ, Barrett-Wilt GA, Kestner CA, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, … Stukenberg PT (2004). The Vertebrate Ndc80 Complex Contains Spc24 and Spc25 Homologs, which Are Required to Establish and Maintain Kinetochore-Microtubule Attachment. Current Biology. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.12.058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh JR, Grishchuk EL, Morphew MK, Efremov AK, Zhudenkov K, Volkov VA, … Ataullakhanov FI (2008). Fibrils Connect Microtubule Tips with Kinetochores: A Mechanism to Couple Tubulin Dynamics to Chromosome Motion. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.08.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MP, Asbury CL, & Biggins S (2016). A TOG protein confers tension sensitivity to kinetochore-microtubule attachments. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers AF, Franck AD, Gestaut DR, Cooper J, Gracyzk B, Wei RR, … Asbury CL (2009). The Ndc80 Kinetochore Complex Forms Load-Bearing Attachments to Dynamic Microtubule Tips via Biased Diffusion. Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.12.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raaijmakers JA, Tanenbaum ME, Maia AF, & Medema RH (2009). RAMA1 is a novel kinetochore protein involved in kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Journal of Cell Science. doi: 10.1242/jcs.051912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt JC, Arthanari H, Boeszoermenyi A, Dashkevich NM, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Monnier N, … Cheeseman IM (2012). The Kinetochore-Bound Ska1 Complex Tracks Depolymerizing Microtubules and Binds to Curved Protofilaments. Developmental Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.09.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spittle C, Charrasse S, Larroque C, & Cassimeris L (2000). The interaction of TOGp with microtubules and tubulin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002597200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K, & Fukagawa T (2012). Molecular architecture of vertebrate kinetochores. Experimental Cell Research. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2012.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umbreit NT, Gonen T, Davis TN, Gestaut DR, Tien JF, Asbury CL, & Vollmar BS (2012). The Ndc80 kinetochore complex directly modulates microtubule dynamics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1209615109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma D, & Salmon ED (2013). The KMN protein network - chief conductors of the kinetochore orchestra. Journal of Cell Science. doi: 10.1242/jcs.093724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma Dileep, Chandrasekaran S, Sundin LJR, Reidy KT, Wan X, Chasse DAD, … Cook JG (2012). Recruitment of the human Cdt1 replication licensing protein by the loop domain of Hec1 is required for stable kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nature Cell Biology. doi: 10.1038/ncb2489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei RR, Al-Bassam J, & Harrison SC (2007). The Ndc80/HEC1 complex is a contact point for kinetochore-microtubule attachment. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welburn JPI, Grishchuk EL, Backer CB, Wilson-Kubalek EM, Yates JR, & Cheeseman IM (2009). The Human Kinetochore Ska1 Complex Facilitates Microtubule Depolymerization-Coupled Motility. Developmental Cell. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann S, Wang HW, Avila-Sakar A, Drubin DG, Nogales E, & Barnes G (2006). The Dam1 kinetochore ring complex moves processively on depolymerizing microtubule ends. Nature. doi: 10.1038/nature04409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigge PA, & Kilmartin JV (2001). The Ndc80p complex from Saccharomyces cerevisiae contains conserved centromere components and has a function in chromosome segregation. Journal of Cell Biology. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.2.349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev AV, Ataullakhanov FI, & Grishchuk EL (2013). Highly transient molecular interactions underlie the stability of kinetochore-microtubule attachment during cell division. Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering. doi: 10.1007/s12195-013-0309-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev AV, Mick JE, Nikashin B, Grishchuk EL, Maslennikov E, & DeLuca JG (2015). Multisite phosphorylation of the NDC80 complex gradually tunes its microtubule-binding affinity. Molecular Biology of the Cell. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e14-11-1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Model calibration varying parameters for biased diffusion. Heatmap showing the diffusion coefficient of a protein complex undergoing biased diffusion as a function of kon and koff and using p = 0.5 (A), p = 0.6 (B), p = 0.7 (C), p = 0.8 (D). Results are computed as averages from 200 independent runs.