Abstract

Sulfite as precursor to generate sulfate radical (SO4•−) for water treatment has gained attention. Here we report a metal-free and highly efficient electro/UV/sulfite process to produce SO4•− for water treatment. UV/sulfite reaction induces sulfite radical (SO3•−), which transforms into SO4•− in the presence of oxygen generated by water electrolysis. Electro/UV/sulfite process generates a steady-state SO4•− concentration of 0.2 to 1.1 × 10−12 M in our tests. Solution pH affects sulfite species distribution, and higher pH mediates improved yield of steady-state SO4•− concentration. Effect of sulfite concentration exhibits a bell-shaped pattern toward SO4•− production due to self-scavenging. The oxidation capability of electro/UV/sulfite process is manifested by removing representative micropollutants (i.e., ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A) and Escherichia coli model pathogen, in both synthetic and natural water matrices. This novel electro/UV/sulfite process has obvious advantages, since it bypasses metal ion catalysts, supplies reaction with electrolytically generated nascent oxygen, and overcomes the acidic pH requirement, that are challenging to traditional metal/sulfite processes. Considering the features of environmental friendliness and low cost, the proposed electro/UV/sulfite process should lead to successful applications in the future.

Keywords: sulfate radical, electrolysis, UV/sulfite, decontamination, disinfection

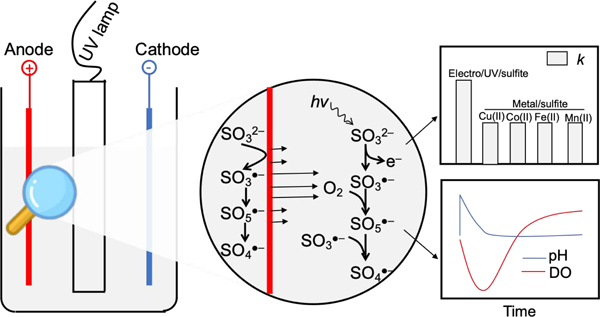

Graphical abstract:

1. Introduction

Current challenges of water pollution require development of efficient treatment strategies. Sulfate radical (SO4•−), because of its high redox potential and selective oxidation, is well studied for water treatment over the past two decades [1–4]. Sulfite as SO4•− precursor under activation by transition metals has been investigated [5,6]. This delicate catalysis relies on valence-variable transition metals to generate SO3•−, which then evolves into SO4•− under oxic conditions, through the formation of corresponding inner-sphere metal-sulfite complex followed by intramolecular ligand-to-metal charge transfer [7]. However, the catalytically functional transition metals pose concerns either due to the requirement of strong acidic pH (e.g. iron, manganese) or their adverse carcinogenic properties (e.g. cobalt, copper, chromium), restricting their applications in practice [5]. Furthermore, surface water and groundwater usually contain buffering agents such as carbonate ions [8,9] which would require large amounts of acids to adjust solution to desired acidic pH. A metal-free platform to efficiently activate sulfite is hence strongly needed.

Literature review identifies UV irradiation of oxygenated sulfite solution as a possible sulfite activation method, that bypasses the metal catalysts for SO4•− production [10–13]. This is supported by two facts. First, UV irradiation (254 nm) decomposes sulfite into hydrated electron (eaq−) and SO3•− (Equations 1 and 2) [12,13], both of which are reductive agents. SO3•− is the precursor of SO4•− radical in the presence of oxygen. The yield of sulfite decomposition under 254 nm UV light is relatively high, i.e., 0.39 for SO32−, and 0.19 for HSO3− [13]. Currently, several studies utilize the generated eaq− (−2.9 V vs SHE) [14,15] by UV/sulfite process under nitrogen atmosphere for breakdown of halogenated organic contaminants [16,17] or transformation of toxic heavy metals [18,19]. The utilization of eaq− requires strict deoxygenated solution, usually under nitrogen atmosphere [16], and otherwise dissolved oxygen could easily scavenge eaq− [20]. In fact, under oxic conditions, the SO3•− byproduct in UV/sulfite process could be possibly upgraded into highly oxidizing SO4•− via Equations 3 and 4 [5,7], which has not been emphasized. Second, several reports disclose the oxidation of aromatic substrates into phenolic products by UV/sulfite under oxygen dissolution, suggesting the SO4•− attack mode [10,12]. Yet, the viability of driving UV/sulfite reaction to proliferate SO4•− has not been fully explored.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

Further, previous results indicate that dissolved oxygen (DO) is instantly depleted during the UV/sulfite process, due to SO3•− and eaq− consumption (Equations 2 and 3). However, the transformation of SO3•− into SO4•− heavily relies on DO content. Oxygen generated by electrolysis exhibits high reactivity in aqueous solution due to its nascence [23,24]. Thus, electrolytic oxygenation is anticipated to promote the SO4•− formation by UV/sulfite process via Equations 1–4 [10].

Building upon prior relevant work on electrochemical water treatment [4–6,24–27], this study rationally couples electrolysis and UV for sulfite activation (i.e., electro/UV/sulfite process) as a metal-free and highly efficient advanced oxidation process. The oxidation capacity of electro/UV/sulfite process is investigated by determining the steady-state SO4•− concentration with benzoic acid, and probing the removal efficiencies of several micropollutants (i.e., ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A) and Escherichia coli model pathogen in diverse water bodies. Compared with previous peroxymonosulfate- or persulfate-based system, such as UV/persulfate system, the obvious advantages of the electro/UV/sulfite process are that 1), it avoids the use of toxic peroxymonosulfate/persulfate compounds; 2), sulfite has short residency upon exposure to the air, and produces benign sulfate anion; and 3), it does not affect the overall water quality especially the DO and pH post treatment. These properties of electro/UV/sulfite process ensure its safe use in water treatment industry.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Chemicals

Sodium sulfite (Na2SO3) and sodium sulfate (Na2SO4) were purchased from Acros Organics (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). Benzoic acid and ibuprofen (2-(4-isobutylphenyl)propanoic acid, C13H18O2) were purchased from Alfa Aesar (Haverhill, MA). Ethanol/thiourea (reactive to HO• and SO4•−) and tert-butanol (reactive to HO•, but inert to SO4•−) from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. were used to scavenge related radicals and discern the role of SO4•− toward substrate oxidation [28,29]. Ferrous sulfate (FeSO4), cobalt chloride (CoCl2), copper sulfate (CuSO4), and manganese chloride (MnCl2) obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. were used to activate sulfite for comparison with electro/UV/sulfite process. Milli-Q water was used throughout this study unless specified. All other chemicals including salicylic acid, bisphenol A, methanol, phosphoric acid, sodium acetate, sodium phosphate, potassium borate, and thiourea were from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.

2.2. Determination of photon flux

The photon flux of used experimental setup (Fig. S1) was determined as previously reported [16]. Briefly, 400 mL solution containing 0.6 M KI and 0.1 M KIO3 buffered in 10 mM borate (pH 9.2) as actinometer was irradiated by monochromatic UV lamp (254 nm). Resulted triiodide product (I3−) was quantified by UV-Vis spectrometer at 352 nm (molar extinction coefficient as 26400 M−1 cm−1). The photon flux was then determined with Equation 5.

| (5) |

where I is the photon flux (Einstein/s), V (0.4 L) is the solution volume, and Φ (0.82 mol/Einstein) is the quantum yield of I3− at 254 nm. The photon flux was calculated as 0.43 μEinstein/s.

2.3. Determination of effective path length

The effective path length was determined with photo-irradiation of 0.5 mM H2O2 solution, which followed pseudo first-order reaction kinetics [16,30,31]. The concentration of H2O2 was quantified with titanium sulfate complexation method, and a yellowish color was developed and measured with UV-Vis spectrometer at 405 nm wavelength [32]. The effective path length was calculated with Equations 6 and 7.

| (6) |

| (7) |

where Ct is the concentration of H2O2 (M) at time t; k is the calculated pseudo first-order kinetic constant of H2O2 decay (s−1); Φapp (1 mol/Einstein) is the apparent quantum yield of H2O2 photolysis at 254 nm [33]; εH2O2 (19.6 M−1 cm−1) is the absorption coefficient of H2O2 at 254 nm [33]; I (0.43 μEinstein/s) is the photo flux; V (0.4 L) is the solution volume. The effective path length of the setup was determined as 2.3 cm.

2.4. Batch assays of electro/UV/sulfite treatment

Electro/UV/sulfite reaction setups contained 400 mL solution of 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, and 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7, with UV irradiation and 200 mA current. Benzoic acid of specific concentration was used to capture/quantify SO4•−. Reactions were initiated by simultaneously switching on the UV lamp (254 nm, 5 W, type UV5-D150W(Y)15, Yayi Inc.) and Agilent E3612A DC power supply workstation to maintain 200 mA current with two identical Ti/MMO (mixed metal oxides) mesh electrodes (5 cm2). Effects of current intensity (0–200 mA), sulfite concentration (0–2 mM), and pH (4–10) were investigated. For the removals of different substrates, 5 μM ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A were utilized as representative micropollutants, and 106 CFU/mL (CFU, colony forming unit) Escherichia coli K12 was used as model water pathogen, without using buffers. Solution DO and pH were monitored during the course of reaction.

2.5. HPLC analysis

Concentrations of organic compounds (i.e., benzoic acid, ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A) were analyzed with a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1200 Infinity Series) equipped with an Agilent Eclipse AAA C18 column (4.6 × 150 mm). Substrates were separated by 0.5 mL/min methanol/1% phosphoric acid (68/32) mobile phase, and detected at 228 nm wavelength using Agilent 1260 diode array detector. Sulfite quantification was performed with a modified HPLC method [27] by injecting 100 μL liquid sample, and the detection limit can be 0.1 mM.

2.6. Escherichia coli inactivation and quantification method

E. coli K12 strain was cultivated in 5 mL LB media of 15 mL culture tube at 37 °C overnight. 50 μL of the fully-grown bacteria solution was then added into 5 mL fresh LB media, and cultivated for another 2 hours. The exponential-phase E. coli was centrifuged at 5000 g for 3 min, and washed with milli-Q water three times to remove nutrients. During bacterial inactivation assay, a final concentration of ~ 106 CFU/mL after dilution of 100 times with water from original solution was prepared to simulate the bacteria concentration in real water bodies [34,35]. 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4 as electrolyte, 200 mA, and UV irradiation were used to inactivate E. coli. To determine the survival rate of E. coli (expressed as Nt/N0), samples were at first serially diluted at a 10-time gradient in 96-well plate, and then 5 μL liquids were dropped on the LB-agar plate with multi-channel pipette followed by overnight growth at 37 °C. Bacterial colonies ranging from 10 to 30 of a specific diluted sample were counted.

2.7. Electron spin resonance assay

50 mM 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide (DMPO) was used to trap radicals in electro/UV/sulfite assay (1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA current, UV, and 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7) and control assays of individual or dual components. Samples were drawn by a capillary tube after reaction for 10 seconds, and then immediately inserted into electron spin resonance (ESR) spectrometer (JES-FA200, Japan Electron Optics Laboratory Co. Ltd., Japan). ESR assays were conducted with 326 mT center field, 30 mT sweep width, 9.147 GHz microwave frequency, and 3 mW microwave power.

2.8. Test of natural water matrices

To further manifest the superior performance of the electro/UV/sulfite process, we tested removals of organics and E. coli bacteria in two natural water bodies. A groundwater sample from a Superfund site in Pozo Mita, Puerto Rico (referred as MIT groundwater), and a surface water sample from Jamaica Pond in the Boston area (referred as JAM surface water), were used as the natural matrices. Water samples were centrifuged at 10000 g for 10 min, and then the supernatants were further filtered with 0.45 μm membrane to remove suspended solid particles or microbes. Water samples were adjusted to neutral pH with 1M H2SO4 or NaOH before sulfite addition, and then treated by the electro/UV/sulfite process. 106 CFU/mL exponential-phase E. coli or 5 μM micropollutants (i.e., ibuprofen, salicylic acid, or bisphenol A) were used as substrate for treatment performance testing with 1 mM sulfite, 200 mA current, and UV irradiation. E. coli inactivation efficiency, organic compounds removal together with its DO and solution pH automatic restorations, were monitored.

2.9. Determination of sulfate radical steady-state concentration

Benzoic acid (BA) was used as a standard compound to capture SO4•−, since its oxidation by SO4•− has been extensively characterized. 0.2 mM BA was selected because oxidation of BA at this concentration could be accurately measured by HPLC and maximally reflect the generated SO4•− by electro/UV/sulfite process.

| (8) |

| (9) |

SO4•− steady-state concentration ([SO4•−]ss) (M) was calculated from Equations 8 and 9, based on experimentally measured r8. The above Equations 8 and 9 are based on the assumption that, BA degradation in the electro/UV/sulfite process is majorly due to SO4•− radical, while the role of other oxidizing species such as HO• is negligible. This hypothesis has been later verified through radical scavenging assays. Therefore, the reaction rate between SO4•− and BA (r8) was determined by quantifying the decrease of BA concentration over time during the first 5 min. The obtained apparent r8 value was then used to calculate ([SO4•−]ss based on Equation 9.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Production of sulfate radical by electro/UV/sulfite process

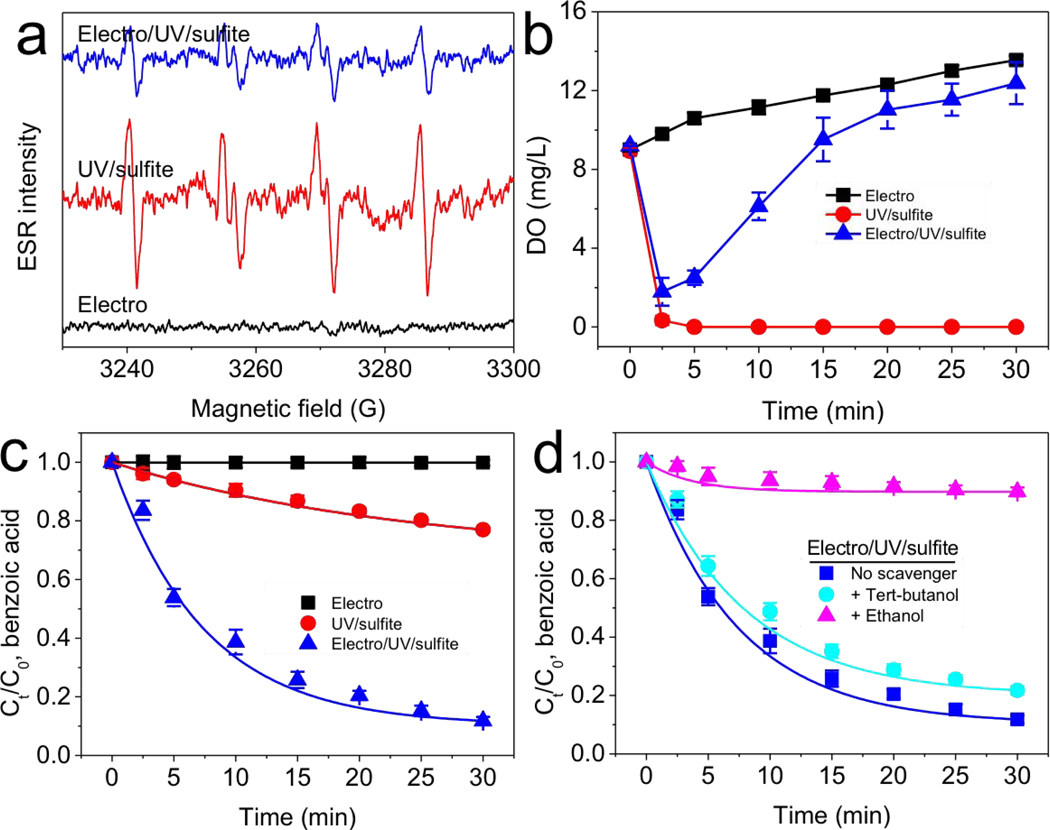

Electron spin resonance assay was first used to confirm the generation of SO3•− from UV/sulfite reaction (Fig. 1a). Typically, DMPO/SO3•− adduct (aHβ = 16.0 G, aN = 14.7 G) [37,38] appeared in UV/sulfite reaction, while UV irradiation or sulfite alone did not produce any noticeable signal (supplementary Fig. S2). DO concentration was measured during UV/sulfite reaction (Fig. 1b). DO concentration rapidly decreased almost to 0 mg/L in 2.5 min, even though the reaction was open to the air and under vigorous stirring. The instant DO depletion was primarily due to the approaching-diffusion rate of reaction between O2 and SO3•−/eaq− (Equations 2 and 3).

Fig. 1.

Electrolysis promoted UV/sulfite process to produce sulfate radical. (a) UV/sulfite process induced SO3•− formation, and (b) electrolytic oxygenation (c, d) transformed SO3•− into SO4•−. Conditions: 5 μM benzoic acid, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7, 200 mA, UV. 50 mM 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide was used during (a) electron spin resonance assay; 5 mM tert-butanol or ethanol was used during (d) radical-scavenging assay. Data were fitted with pseudo first-order reaction kinetics.

Water electrolysis was then used to provide oxygen for transforming SO3•− into SO4•− during UV/sulfite reaction. The DO concentration started to recover shortly (within 2.5 min) and increased to saturation during UV/sulfite reaction. As a result, SO3•− signal was weakened via its enhanced transformation into secondary SO4•− by electrolytically generated O2 (Fig. 1a). DMPO mainly trapped the primary SO3•− radical, and secondary SO4•− was not detected in electron spin resonance assay. Benzoic acid has been extensively used to capture various transient reactive species [39] and was therefore used in this study. The oxidation percentage of 5 μM benzoic acid improved from 23% to 88% after 30 min reaction when applying electrolysis to the UV/sulfite process (Fig. 1c), indicating the enhanced oxidation capability. We also monitored sulfite concentration during reactions (Fig. S3). Application of electrolysis increased sulfite consumption from 46.8% to 96% after 30 min. The noticeable sulfite oxidation by the UV/sulfite process was due to the dissolution of atmospheric oxygen; the significant increase of sulfite consumption was due to electrolytic oxygenation.

The reactive radicals generated in the electro/UV/sulfite process were examined. Different radical scavengers were used to verify this hypothesis [5]. 5 mM ethanol (reactive toward SO4•−) [10] almost completely inhibited oxidation of benzoic acid treated by electro/UV/sulfite process, whereas 5 mM tert-butanol (inert toward SO4•−) [12] showed relatively little impact (Fig. 1d). Radical scavenging assay also confirmed that the slight removal of benzoic acid by UV/sulfite process was due to SO4•− generated under atmospheric oxygen dissolution (Fig. S4). It is concluded that the main oxidation capability of electro/UV/sulfite treatment is ascribed to SO4•−.

3.2. Synergy mechanism of sulfate radical production

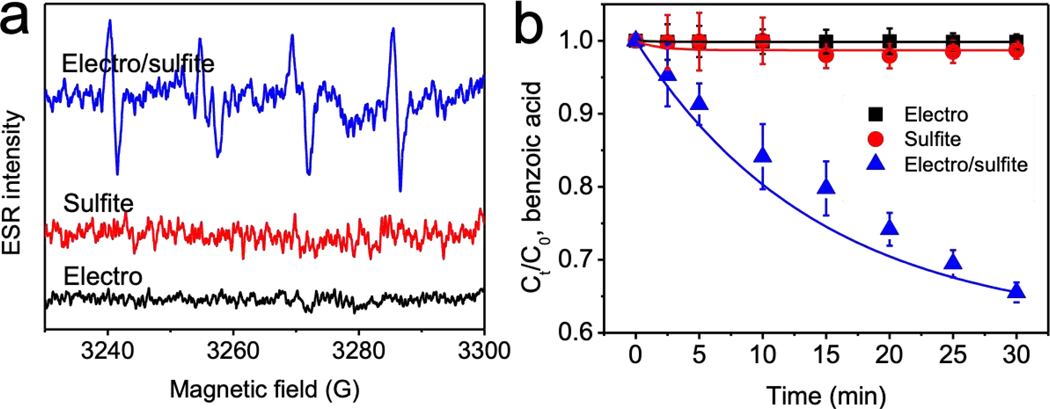

During the electro/UV/sulfite reaction, sulfite solution was under both UV irradiation and electrolysis. The electron spin resonance assay showed that electro/sulfite reaction produced a clear DMPO/SO3•− signal, while electrolysis or sulfite alone did not generate such signal (Fig. 2a). This is not surprising because it is reported that sulfite molecules absorbed on various anodes could be oxidized by transferring one electron directly to the anodes [40–42]. After sulfite donates an electron, SO3•− is produced from electro/sulfite reaction. Therefore, SO3•− formation is an anodic process that occurs on the surface of anode, agreeing with previous report [43].

Fig. 2.

Electro/sulfite process generated sulfate radical, as (a) visualized in electron spin resonance assay and (b) demonstrated by benzoic acid removals. Conditions: 5 μM benzoic acid, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7, 200 mA.

In our study, Ti/MMO was used as inert electrodes. After in situ SO3•− formation on the Ti/MMO anode, SO3•− is supposed to further transform into SO4•− in the presence of oxygen produced from water electrolysis. 5 μM benzoic acid was used to probe the generated SO4•− from electro/sulfite reaction. 34.5% of benzoic acid was removed by electro/sulfite process after 30 min, while electrolysis or sulfite alone produced a relatively little effect (Fig. 2b). Radical quenching studies using tert-butanol and ethanol further confirmed the role of SO4•− in degrading benzoic acid (Fig. S5). Specifically, with 5 mM tert-butanol, benzoic acid removal efficiency by electro/sulfite process decreased from 34.5% to 26.5%; benzoic acid removal was fully inhibited by 5 mM ethanol.

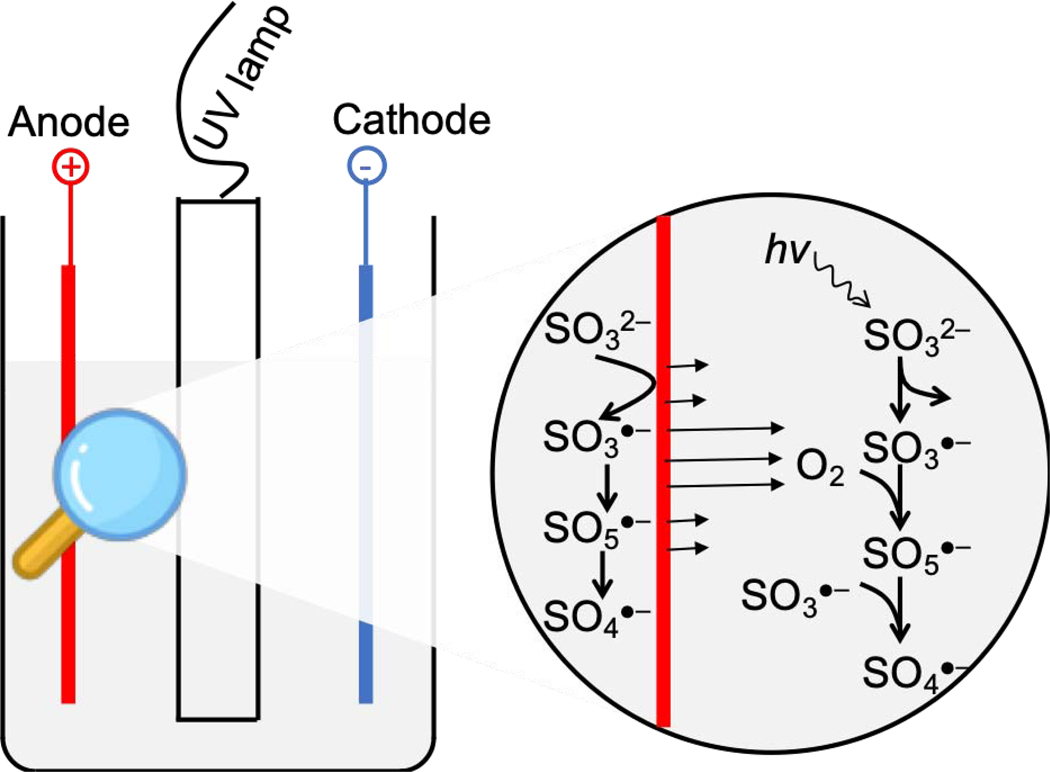

Therefore, the SO3•− as precursor of SO4•− has two sources, i.e., UV irradiation of sulfite solution, and anodic oxidation of adsorbed sulfite molecules (Fig. 3). The UV/sulfite process occurs in bulk solution to produce SO3•−, while the electro/sulfite process occurs on the surface of electrode, since only adsorbed sulfite molecules participate in the single-electron transfer [40–42]. The formed SO3•− on the anode surface then transforms into SO4•−. Considering the short life of SO4•−, the formation of SO4•− also occurs on the anode surface. Hence, the SO4•− formed in bulk solution and anode surface together oxidized substrates.

Fig. 3.

Schematic mechanism of sulfate radical proliferation during electro/UV/sulfite process. Primarily, UV induced sulfite to produce SO3•−, which then transformed into SO4•− under electrolytic oxygenation. Moreover, electrolysis of sulfite solution also produced SO4•− through direct one-electron transfer from sulfite molecule to anode surface.

3.3. Yield of sulfate radical by electro/UV/sulfite process

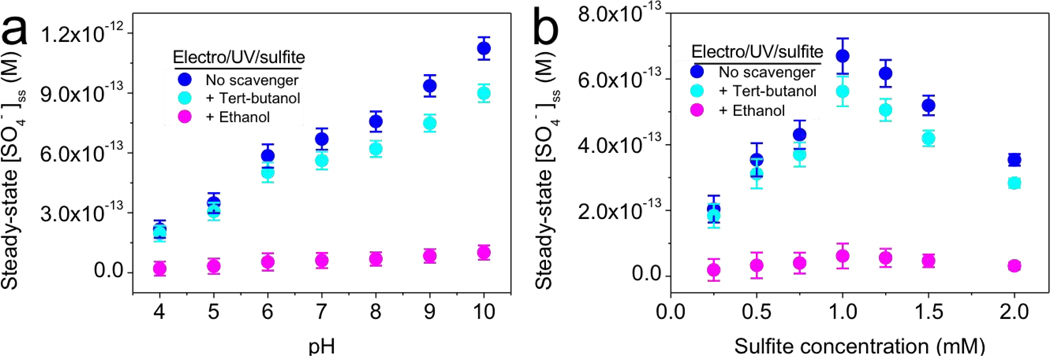

Coupling UV irradiation and electrolysis toward sulfite activation generates SO4•−. The oxidation potential of electro/UV/sulfite process, as represented by the steady-state SO4•− concentration, was explored under varying solution pH (pH 4–10) and sulfite concentrations (0–2 mM) (Fig. 4). 0.2 mM benzoic acid was used to capture generated SO4•− by electro/UV/sulfite process, and determination method of steady-state SO4•− concentration was described in Section 2.9.

Fig. 4.

Steady-state sulfate radical concentrations mediated by electro/UV/sulfite process under varying (a) pH and (b) sulfite concentration. Typical conditions: 0.2 mM benzoic acid as capturing agent, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7, 200 mA, UV. 200 mM tert-butanol and ethanol were used as scavengers. (a) different pH buffers were used, that is, 10 mM acetate (pH 4–5), phosphate (pH 6–8), and borate (pH 9–10). (b) sulfite concentration varied between 0.25 and 2 mM, under 10 mM phosphate buffer at pH 7.

3.3.1. Role of pH

The role of pH was investigated using different buffers. Specifically, 10 mM acetate (pH 4–5), phosphate (pH 6–8), and borate (pH 9–10) buffers were used to maintain solution acidity/alkalinity. These buffers are inert toward SO4•− [44] and therefore do not compete with heterologous substrates toward the SO4•− pool. Solution pH affects the efficiency of electro/UV/sulfite process by affecting the species distribution of sulfite. As solution pH increases, sulfite shifts from HSO3− to SO32− species (Fig. S6). Compared with HSO3−, SO32− owns higher absorption coefficient and quantum yield under UV irradiation at 254 nm [13,16]. Therefore, higher pH is beneficial for SO3•− generation from UV/sulfite reaction. As described before, SO3•− can also be generated from electro/sulfite reaction. It is reported that SO32− (0.63 V vs SHE) [45] is more readily reduced than HSO3− (0.84 V vs SHE) [11]. As a result, this Faradaic process is more effective in alkaline condition because of facile one-electron transfer from adsorbed sulfite molecule to the anode surface [40,41].

The overall yield of SO4•− based on the mechanisms described above (Fig. 3) appeared to increase with pH (Fig. 4a). For example, the steady-state SO4•− concentrations of electro/UV/sulfite process at pH 4, 7, and 10 were 2.18 × 10−13, 6.69 × 10−13, and 1.12 × 10−12 M, respectively. Furthermore, tert-butanol slightly affected SO4•− production, and ethanol fully quenched generated SO4•−, consistent with above observations.

3.3.2. Role of sulfite concentration

Steady-state SO4•− concentration initially increased with increasing sulfite concentration, but then decreased when sulfite concentration reached over 1 mM during the electro/UV/sulfite process (Fig. 4b). 1 mM sulfite mediated a maximum steady-state SO4•− concentration of up to 6.7 × 10−13 M. This volcano pattern is because high concentration (over-dose) of sulfite tends to compete with the substrate toward SO4•− reservoir [12], which is consistent with previous reports [5]. The role of SO4•− during electro/UV/sulfite process was again verified by the differential radical-scavenging assay via addition of tert-butanol and ethanol. Of note, the steady-state SO4•− concentration of electro/UV/sulfite process under neutral condition (6.69 × 10−13 M) was around two orders of magnitude higher than that of reported iron/sulfite process [46], highlighting a preeminent oxidation capability of electro/UV/sulfite process.

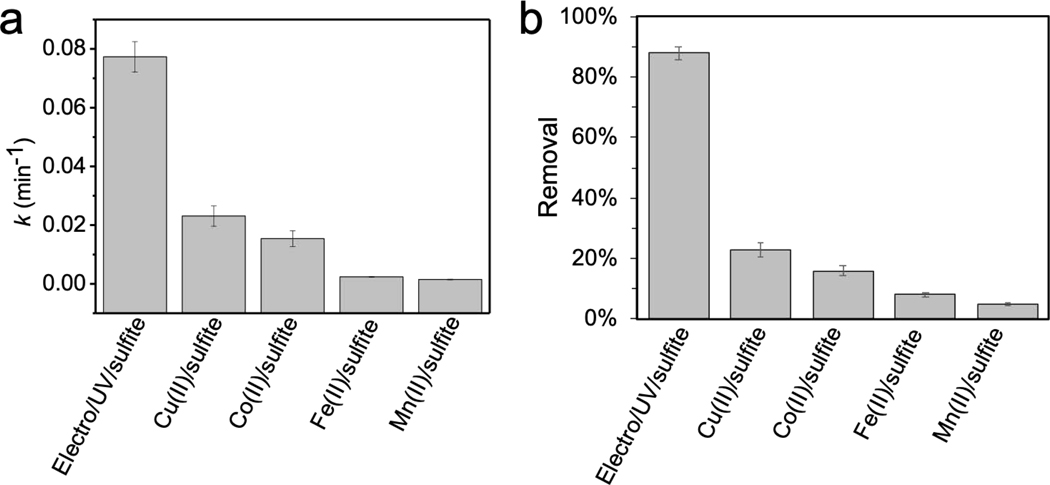

3.4. Oxidative capacity of electro/UV/sulfite compared with traditional metal/sulfite processes

The performances of electro/UV/sulfite process were compared with metal/sulfite processes. Reactions were evaluated at pH 7. A 10 mM MOPS buffer was selected as an inert buffer to maintain the neutral solution since transition metals such as Cu(II) and Fe(II) tend to complex with phosphate ion [47]. 5 μM benzoic acid was either treated by electro/UV/sulfite process (1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4 supporting electrolyte, 200 mA, UV, 10 mM MOPS, pH 7) or metal/sulfite processes (0.1 mM Fe(II)/Co(II)/Cu(II)/Mn(II), 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM MOPS, pH 7). Pseudo first-order removal constants (k) of benzoic acid by electro/UV/sulfite and metal/sulfite processes were then compared. Measured k of benzoic acid treated by electro/UV/sulfite, Cu(II)/sulfite, Co(II)/sulfite, Fe(II)/sulfite, and Mn(II)/sulfite processes were 0.0773, 0.0231, 0.0154, 0.0024, and 0.0015 min−1, respectively (Fig. 5). The performance of electro/UV/sulfite process is superior than the transition metal-based sulfite activation processes, primarily because of its independence of transition metal ion catalysis. It is however worthy to mention that, sulfate radical-based water treatment technology has been majorly deployed to destroy the structure of toxins, while its capability of further breaking fragmented intermediates down into CO2 and H2O is relatively weak compared to hydroxyl radical [1,2]. This is because SO4•− is highly electrophilic, and therefore it mainly attacks electron-rich groups such as aromatic ring. The oxidation intermediates are usually poor in electrons, and oftentimes they do not tend to react fast with SO4•− [1,2]. In our study, we also observed above phenomenon, as the TOC (total organic carbon) removals by both electro/UV/sulfite and metal/sulfite processes were less than 20%. Nonetheless, in fact sulfate radical-based process is often conjugated with other processes such as hydroxyl radical oxidation or membrane filtration to achieve complete removal of the toxins in water.

Fig. 5.

Comparisons of benzoic acid degradation in terms of (a) kinetics and (b) removals after reaction for 30 min by electro/UV/sulfite and metal/sulfite processes. Conditions: electro/UV/sulfite process − 5 μM benzoic acid, 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, UV; metal/sulfite processes − 5 μM benzoic acid, 1 mM sulfite, 0.1 mM metal ions (i.e., Cu(II), Co(II), Fe(II), or Mn(II)). Reactions were carried out in 10 mM MOPS buffer at pH 7.

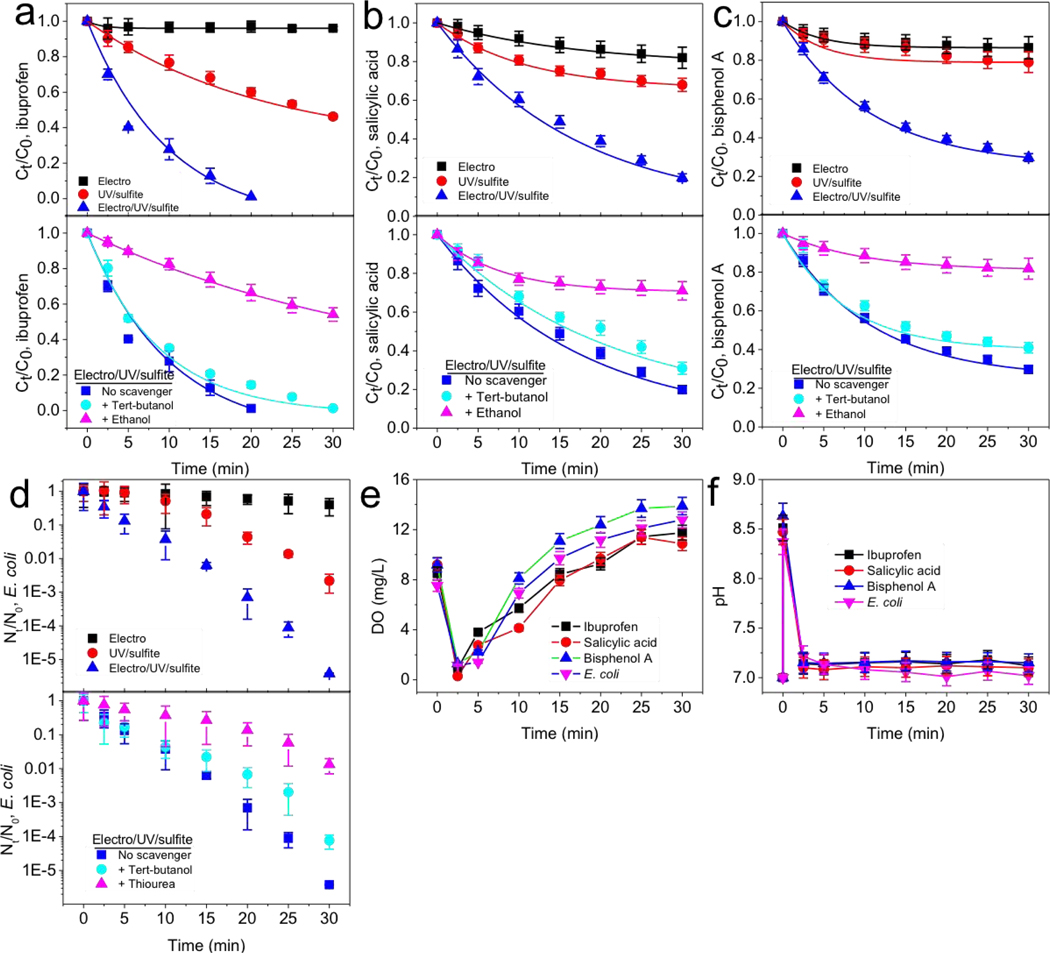

3.5. Contaminant removal and disinfection

Removal of contaminants and inactivation of waterborne pathogens (i.e., disinfection) are important water treatment processes. The electro/UV/sulfite process is an efficient and relatively green platform for contaminant removal and disinfection. Removal of ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A, which are frequently detected in various environmental media [48–50]; and Gram-negative Escherichia coli K12, a debilitated strain lacking virulence characteristics [51], was evaluated.

Applying electrolysis to UV/sulfite process increased the pseudo first-order removal rate (k) from 0.0246, 0.0124, and 0.0071 min−1 (without electrolysis), to 0.1986, 0.0505, and 0.0395 min−1 (with electrolysis), for 5 μM ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A, respectively (Fig. 6a–c). Radical-scavenging assay with tert-butanol and ethanol validated the vital role of SO4•−. Among the selected organic substrates, ibuprofen was the most susceptible to photolysis (k, 0.0165 min−1), and salicylic acid and bisphenol A exhibited slight electrolysis activity (k, 0.0066 and 0.0043 min−1, respectively). The combination of substrate removal by photolysis, electrolysis, and SO4•− agreed well with experimentally obtained pseudo first-order removal rate (Fig. S7).

Fig. 6.

Electro/UV/sulfite process efficiently removed (a-c) various organic compounds and (d) E. coli microbe, together with automatic adjustments of (e) dissolved oxygen and (f) solution pH. Conditions: 1 mM sulfite, 10 mM Na2SO4, 200 mA, UV. 5 μM ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A were used as micropollutants; 106 CFU/mL E. coli cell in exponential-phase was used as model pathogen. 5 mM tert-butanol and ethanol were used for (a-c), and 100 mM tert-butanol and thiourea were used for (d). Solution was neutral before sulfite addition, and it turned alkaline (~ pH 8.6) after sulfite addition. Data in panels (a-c) were fitted with pseudo first-order reaction kinetics.

106 CFU/mL of exponential-phase E. coli, the maximum concentration in natural water bodies [34,35], was diluted from cultured E. coli in nutritious LB media. By applying electrolysis to UV/sulfite process, E. coli inactivation efficiency was improved from 2.6-log to 5.4-log after 30 min (Fig. 6d). Tert-butanol and thiourea [52], instead of ethanol as it is a bactericidal reagent [53], were used to verify the bactericidal role of SO4•−. Notably, thiourea suppressed 3.5-log of E. coli inactivation by scavenging SO4•−, and the rest of E. coli death was caused by UV disinfection which thiourea did not fully rescue [54,55].

Importantly, along with efficient water treatment, the electro/UV/sulfite process automatically regulated the restoration of DO and solution pH to initial conditions (Fig. 6e,f), which are challenging for traditional metal/sulfite process. During electro/UV/sulfite process, DO dropped from 7.5–9.2 mg/L to 0.3–1.3 mg/L at 2.5 min, but subsequently recovered to reach saturation level (10.9–13.9 mg/L) due to electrolytic oxygenation. Moreover, the addition of sulfite turned solution from neutral to alkaline (~ pH 8.6), and solution pH dropped to its original neutral condition at the end of electro/UV/sulfite reactions because of sulfite oxidation into sulfate.

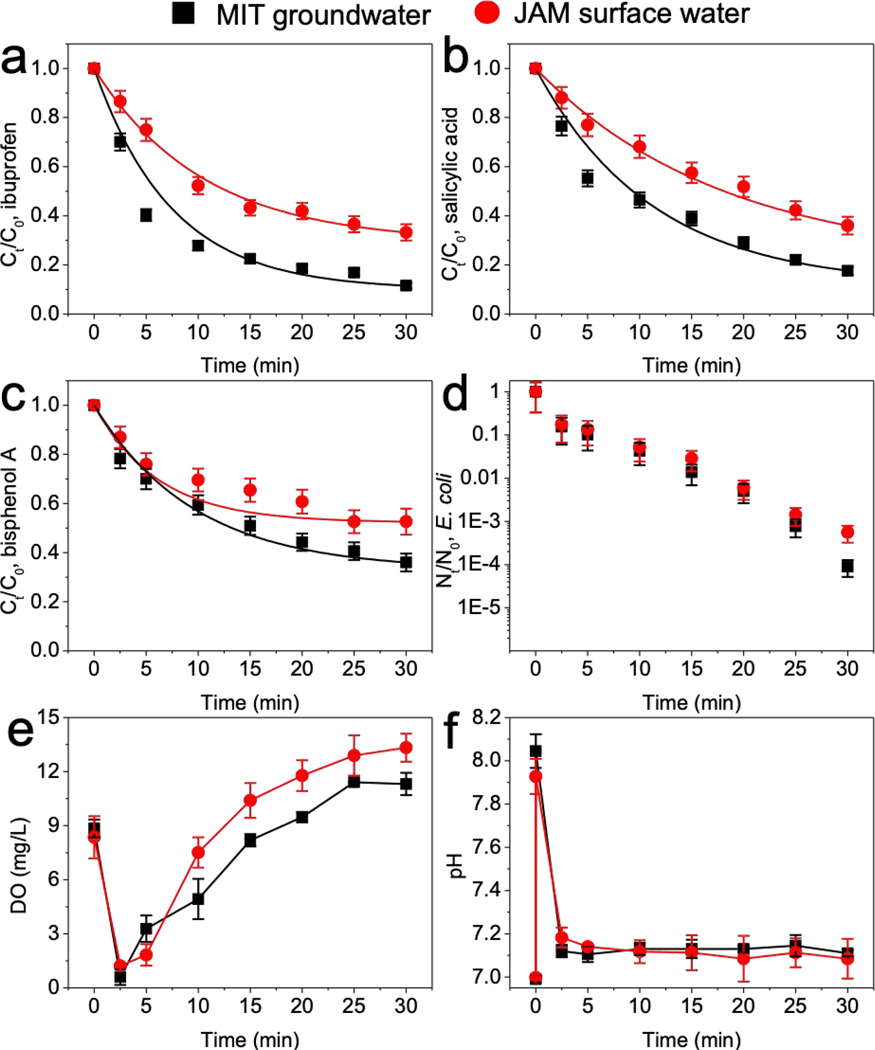

3.6. Efficient treatment of natural water matrices

We then attempted to treat natural water bodies with the electro/UV/sulfite process. A groundwater sample with high carbonate alkalinity collected from Pozo Mita Superfund site of karst topography in Puerto Rico, and a surface water sample with high organic carbon content from a local Jamaica pond in Boston, were used as background matrices. Each of 5 μM target organic contaminants and 106 CFU/mL E. coli was individually prepared in the water samples. Intrinsic ionic species and added sulfite provided the conductivity of the respective treatment, without additional electrolyte. 50% to 90% of the organic contaminants and more than 3.3-log of E. coli were removed in both water matrices treated by electro/UV/sulfite process after 30 min reaction (Fig. 7). The slightly lower removal efficiencies in surface water were primarily due to the high content of organic carbon (Table S1), that competed with target compounds toward SO4•−. Overall, the electro/UV/sulfite process exhibited high efficiency in natural water bodies, together with automatic DO and pH restorations, showing great promise for future applications. The electro/UV/sulfite process is also a low-cost system. In our studies, to treat 400 mL solution, current on electrodes was 200 mA, and voltage was between 5 and 10 V. Considering that the UV lamp is 5 W, the total electric power is around 6–7 W. Based on the average US industrial electricity rate of $0.0676/kWh [56], the overall cost of electro/UV/sulfite process is estimated to be around $0.5/m3. This cost is variable based on water chemistry such as conductivity and can be affordable by most water treatment plants. These data clearly suggest that, the electro/UV/sulfite process could be used for a wide variety of water treatment applications, such as in situ remediation and chemical treatment in a primary water treatment tank, etc.

Fig. 7.

Performance of electro/UV/sulfite process in natural water matrices. Electro/UV/sulfite process was used to treat (a) ibuprofen, (b) salicylic acid, (c) bisphenol A, and (d) E. coli, accompanied with automatic adjustments of (e) dissolved oxygen and (f) solution pH. Conditions: 1 mM sulfite, 200 mA, UV. 5 μM ibuprofen, salicylic acid, and bisphenol A were used as micropollutants; 106 CFU/mL E. coli cell in exponential-phase was used as model pathogen. Note: MIT groundwater, Pozo mita groundwater in our Superfund site in Puerto Rico; JAM surface water, Jamaica pond in local Boston, MA.

4. Conclusions

In this work, we designed a metal-free and highly effective electro/UV/sulfite process for water treatment, through oxidation by SO4•− radical. Electro/UV/sulfite process shows high oxidation efficiency toward a wide range of contaminants under varying conditions, together with automatic restorations of DO and solution pH. Electro/UV/sulfite process exhibits superior performance than traditional transition metal catalyzed sulfite activation processes, and does not require the addition of acid to maintain solution acidity. Further, the electro/UV/sulfite process relies on low-cost sulfite as the precursor of SO4•− radical and generates relatively benign sulfate as an end product. Collectively, these advantages indicate valuable environmental implications, since this superior and environmentally friendly platform would not intrusively affect the native ecology/hydrology and hence could maximally offer convenience for following downstream treatments.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Electrolysis provides oxygen for sulfite-based sulfate radical generation

UV initiates the chain reaction to produce sulfate radical

Greener pollutants abatement without metal ion catalyst

Effective at neutral pH and efficient to various organic compounds

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported by the US National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences of the National Institute of Health (Grant No. P42ES017198). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding sources.

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Materials

Reactor configuration, radical scavenging assay of electro/sulfite process, sulfite species distribution, organic contaminants degradation pathways contribution, and characterizations of natural water matrices are included in Supporting Materials.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference:

- [1].Anipsitakis GP, Dionysiou DD, Degradation of organic contaminants in water with sulfate radicals generated by the conjunction of peroxymonosulfate with cobalt, Environ. Sci. Technol 37 (2003) 4790–4797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Anipsitakis GP, Dionysiou DD, Radical generation by the interaction of transition metals with common oxidants, Environ. Sci. Technol 38 (2004) 3705–3712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Avetta P, Pensato A, Minella M, Malandrino M, Maurino V, Minero C, Hanna K, Vione D, Activation of persulfate by irradiated magnetite: implications for the degradation of phenol under heterogeneous photo-Fenton-like conditions, Environ. Sci. Technol 49 (2014) 1043–1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Yuan S, Liao P, Alshawabkeh AN, Electrolytic manipulation of persulfate reactivity by iron electrodes for trichloroethylene degradation in groundwater, Environ. Sci. Technol 48 (2013) 656–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhou D, Chen L, Li J, Wu F, Transition metal catalyzed sulfite auto-oxidation systems for oxidative decontamination in waters: a state-of-the-art minireview, Chem. Eng. J 346 (2018) 726–738. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yuan S, Chen M, Mao X, Alshawabkeh AN, Effects of reduced sulfur compounds on Pd-catalytic hydrodechlorination of trichloroethylene in groundwater by cathodic H2 under electrochemically induced oxidizing conditions, Environ. Sci. Technol 47 (2013) 10502–10509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kuo DT, Kirk DW, Jia CQ, The chemistry of aqueous S(IV)-Fe-O2 system: state of the art, J. Sulfur Chem. 27 (2006) 461–530. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Glaze WH, Kang JW, Chapin DH, The Chemistry of Water Treatment Processes Involving Ozone, Hydrogen Peroxide and Ultraviolet Radiation, Ozone Sci. Eng. 9 (1987) 335–352. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kumar A, Bisht BS, Joshi VD, Singh AK, Talwar A, Physical, chemical and bacteriological study of water from rivers of Uttarakhand, J. Hum. Ecol 32 (2010) 169–173. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Deister U, Warneck P, Photooxidation of sulfite (SO32−) in aqueous solution, J. Phys. Chem 94 (1990) 2191–2198. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Huie RE, Neta P, Chemical behavior of sulfur trioxide (1-)(SO3-) and sulfur pentoxide (1-)(SO5-) radicals in aqueous solutions, J. Phys. Chem 88 (1984) 5665–5669. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Hayon E, Treinin A, Wilf J, Electronic spectra, photochemistry, and autoxidation mechanism of the sulfite-bisulfite-pyrosulfite systems. The SO2−, SO3−, SO4−, and SO5− radicals, J. Am. Chem. Soc 94 (1972) 47−57. [Google Scholar]

- [13].Fischer M, Warneck P, Photodecomposition and photooxidation of hydrogen sulfite in aqueous solution, J. Phys. Chem 100 (1996) 15111–15117. [Google Scholar]

- [14].Buxton GV, Greenstock CL, Helman WP, Ross AB, Critical review of rate constants for reactions of hydrated electrons, hydrogen atoms and hydroxyl radicals (•OH/•O−) in aqueous solution, Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 17 (1988) 513–886. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Siefermann KR, Abel B, The hydrated electron: A seemingly familiar chemical and biological transient, Angew. Chem., Int. Ed 50 (2011) 5264–5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Li X, Ma J, Liu G, Fang J, Yue S, Guan Y, Chen L, Liu X, Efficient reductive dechlorination of monochloroacetic acid by sulfite/UV process, Environ. Sci. Technol 46 (2012) 7342–7349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Song Z, Tang H, Wang N, Zhu L, Reductive defluorination of perfluorooctanoic acid by hydrated electrons in a sulfite-mediated UV photochemical system, J. Hazard. Mater 262 (2013) 332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Xie B, Shan C, Xu Z, Li X, Zhang X, Chen J, Pan B, One-step removal of Cr(VI) at alkaline pH by UV/sulfite process: reduction to Cr(III) and in situ Cr(III) precipitation, Chem. Eng. J 308 (2017) 791–797. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang X, Liu H, Shan C, Zhang W, Pan B, A novel combined process for efficient removal of Se(VI) from sulfate-rich water: Sulfite/UV/Fe(III) coagulation, Chemosphere 211 (2018) 867–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Elliot AJ, A pulse radiolysis study of the temperature dependence of reactions involving H, OH and e−aq in aqueous solutions, Int. J. Radiat. Appl. Instrum., Part C. Radiat. Phys. Chem 34 (1989) 753–758. [Google Scholar]

- [21].Buxton GV, Salmon GA, Wood ND, A pulse radiolysis study of the chemistry of oxysulphur radicals in aqueous solution In Physico-Chemical Behaviour of Atmospheric Pollutants, (1990) 245–250. Springer, Dordrecht. [Google Scholar]

- [22].Warneck P, Ziajka J, Reaction Mechanism of the Iron(III)-Catalyzed Autoxidation of Bisulfite in Aqueous Solution: Steady State Description for Benzene as Radical Scavenger, Ber. Bunsengese, Phys. Chem 99 (1995) 59–65. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yu F, Zhou M, Zhou L, Peng R, A Novel Electro-Fenton Process with H2O2 Generation in a Rotating Disk Reactor for Organic Pollutant Degradation, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 1 (2014) 320–324. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zhou W, Meng X, Gao J, Alshawabkeh AN, Hydrogen peroxide generation from O2 electroreduction for environmental remediation: A state-of-the-art review, Chemosphere. 225 (2019) 588–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Sarahney H, Alshawabkeh AN, Effect of current density on electrolytic transformation of benzene for groundwater remediation, J. Hazard. Mater 143 (2007) 649–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Alshawabkeh AN, Sarahney H, Effect of current density on enhanced transformation of naphthalene, Environ. Sci. Technol 39 (2005) 5837–5843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yuan S, Chen M, Mao X, Alshawabkeh AN, A three-electrode column for Pd-catalytic oxidation of TCE in groundwater with automatic pH-regulation and resistance to reduced sulfur compound foiling, Water Res. 47 (2013) 269–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Chen L, Peng X, Liu J, Li J, Wu F, Decolorization of Orange II in aqueous solution by an Fe(II)/sulfite system: replacement of persulfate, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res 51 (2012) 13632–13638. [Google Scholar]

- [29].Chen L, Huang X, Tang M, Zhou D, Wu F, Rapid dephosphorylation of glyphosate by Cu-catalyzed sulfite oxidation involving sulfate and hydroxyl radicals, Environ. Chem. Lett 16 (2018) 1507–1511. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Guo K, Zhang J, Li A, Xie R, Liang Z, Wang A, Ling L, Li X, Li C, Fang J, UV Irradiation of Permanganate Enhanced the Oxidation of Micropollutants by Producing HO• and Reactive Manganese Species, Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett 5 (2018) 750–756. [Google Scholar]

- [31].Garoma T, Gurol MD, Modeling aqueous ozone/UV process using oxalic acid as probe chemical, Environ. Sci. Technol 39 (2005) 7964–7969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Eisenberg G, Colorimetric determination of hydrogen peroxide, Ind. Eng. Chem. Anal. Ed 15 (1943) 327–328. [Google Scholar]

- [33].Baxendale JH, Wilson JA, The photolysis of hydrogen peroxide at high light intensities, Trans. Faraday Soc 53 (1957) 344–356. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Cabral JP, Water microbiology. Bacterial pathogens and water, Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 7 (2010) 3657–3703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Pandey PK, Kass PH, Soupir ML, Biswas S, Singh VP, Contamination of water resources by pathogenic bacteria, AMB Express 4 (2014) 51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Neta P, Huie RE, Ross AB, Rate constants for reactions of inorganic radicals in aqueous solution, J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 17 (1988) 1027e1284. [Google Scholar]

- [37].Ranguelova K, Bonini MG, Mason RP, (Bi)sulfite oxidation by copper, zinc-superoxide dismutase: sulfite-derived, radical-initiated protein radical formation, Environ. Health Perspect. 118 (2010) 970–975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Mottley C, Mason RP, Sulfate anion free radical formation by the peroxidation of (bi)sulfite and its reaction with hydroxyl radical scavengers, Arch. Biochem. Biophys 267 (1988) 681–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Ling L, Zhang D, Fan C, Shang C, A Fe(II)/citrate/UV/PMS process for carbamazepine degradation at a very low Fe(II)/PMS ratio and neutral pH: The mechanisms, Water Res. 124 (2017) 446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lu J, Dreisinger DB, Cooper WC, Anodic oxidation of sulphite ions on graphite anodes in alkaline solution, J. Appl. Electrochem 29 (1999) 1161–1170. [Google Scholar]

- [41].Zelinsky AG, Pirogov BY, Electrochemical oxidation of sulfite and sulfur dioxide at a renewable graphite electrode, Electrochim. Acta 231 (2017) 371–378. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Brevett CAS, Jonson DC, Anodic oxidations of sulfite, thiosulfate, and dithionite at doped PbO2-film electrodes, J. Electrochem. Soc 139 (1992) 1314–1319. [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chen L, Xu G, Rui Z, Alshawabkeh AN, Demonstration of a feasible energy-water-environment nexus: Waste sulfur dioxide for water treatment, Appl. Energy, 250 (2019) 1011–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Chawla OP, Fessenden RW, Electron spin resonance and pulse radiolysis studies of some reactions of SO4•−, J. Phys. Chem 79 (1975) 2693–2700. [Google Scholar]

- [45].Neta P, Huie RE, Free-radical chemistry of sulfite, Environ. Health Perspect. 64 (1985) 209–217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Zhou D, Chen L, Zhang C, Yu Y, Zhang L, Wu F, A novel photochemical system of ferrous sulfite complex: Kinetics and mechanisms of rapid decolorization of Acid Orange 7 in aqueous solutions, Water Res. 57 (2014) 87–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Van Wazer JR, Callis CF, Metal complexing by phosphates, Chem. Rev 58 (1958) 1011–1046. [Google Scholar]

- [48].Peng X, Yu Y, Tang C, Tan J, Huang Q, Wang Z, Occurrence of steroid estrogens, endocrine-disrupting phenols, and acid pharmaceutical residues in urban riverine water of the Pearl River Delta, South China, Sci. Total Environ. 397 (2008) 158–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Snyder SA, Westerhoff P, Yoon Y, Sedlak DL, Pharmaceuticals, personal care products, and endocrine disruptors in water: implications for the water industry, Environ. Eng. Sci 20 (2003) 449–469. [Google Scholar]

- [50].Pahigian JM, Zuo Y, Occurrence, estrogen-related bioeffects and fate of bisphenol A chemical degradation intermediates and impurities: A review, Chemosphere 207 (2018) 469–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Clark AJ, Margulies AD, Isolation and characterization of recombination-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli K12, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 53 (1965) 451–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Chen L, Tang M, Chen C, Chen M, Luo K, Xu J, Zhou D, Wu F, Efficient bacterial inactivation by transition metal catalyzed auto-oxidation of sulfite, Environ. Sci. Technol 51 (2017) 12663–12671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Ingram LO, Ethanol tolerance in bacteria, Crit. Rev. Biotechnol 9 (1989) 305–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Gourmelon M, Cillard J, Pommepuy M, Visible light damage to Escherichia coli in seawater—oxidative stress hypothesis, J. Appl. Bacteriol 77 (1994) 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Fisher MB, Nelson KL, Inactivation of Escherichia coli by polychromatic simulated sunlight: evidence for and implications of a Fenton mechanism involving iron, hydrogen peroxide, and superoxide, Appl. Environ. Microbiol 80 (2014) 935–942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Average Price of Electricity to Ultimate Customers. https://www.eia.gov/electricity/monthly/epm_table_grapher.php?t=epmt_5_3 (accessed on June, 2020)

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.