Emergency physicians (EPs) have played a critical role in the response to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). While public health efforts (e.g., statewide stay-at-home orders) had initially flattened the curve [1], COVID-19 spread in the U.S. has once again begun to accelerate. On October 23, 2020, the U.S. reached a new pandemic record of 83,010 daily cases [1], and all signs point toward an impending “second wave” or “third surge.” Given the association between advanced age and COVID-19 severity [2], our objective was to compare the geographic distribution of U.S. EPs age ≥ 60 years to the cumulative distribution of confirmed COVID-19 cases, to highlight the potential risks faced by this vulnerable population of clinicians.

Demographic information on practicing EPs age ≥ 60 during 2018 was extracted from State Physician Workforce Reports published by the American Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) [3]. Information recorded included the number of EPs age ≥ 60 per state, proportion of EPs age ≥ 60 per state, total number of EPs per state, and state population per EP. Coordinate data (i.e., latitude and longitude) on the cumulative distribution of COVID-19 cases as of October 22, 2020 were obtained from a disease-specific data repository published by the Environmental Systems Research Institute [4]. We integrated both datasets into QGIS geospatial analysis software (version 3.12.1), superimposing them onto state boundary files published by the U.S. Census Bureau [5]. States were grouped into color-coordinated quintiles based on proportion of EPs age ≥ 60, and a logarithmic scale was used to adjust coordinate data points of cumulative COVID-19 cases, resulting in a heatmap depicting the proportion of EPs age ≥ 60 and COVID-19 disease burden for each state. This study was deemed IRB exempt due to the use of deidentified and publicly available data.

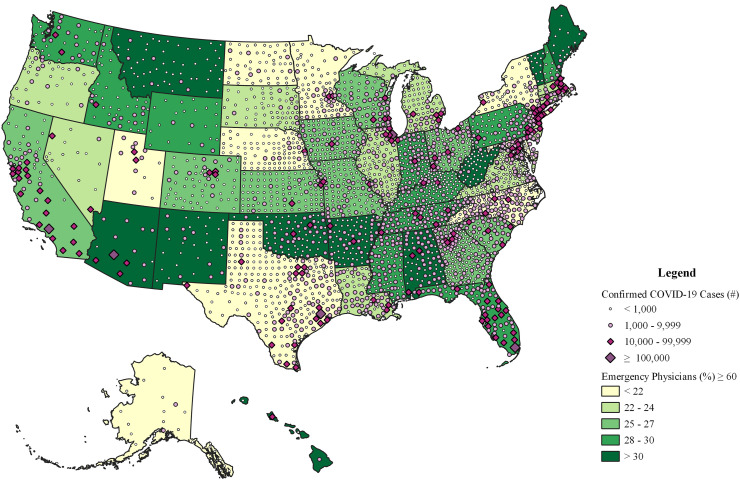

The AAMC identified a total of 43,311 clinically active EPs in 2018, of whom 10,804 (24.9%) were age ≥ 60 years [3]. The 10 states in the highest quintile of older EPs were West Virginia, New Mexico, Vermont, Hawaii, Maine, Oklahoma, Montana, Alabama, Arkansas, and Arizona (Table 1 ). The proportion of EPs age ≥ 60 ranged from 16.0% in Rhode Island to 40.6% in West Virginia. The five states with the highest number of cumulative COVID-19 cases as of October 22, 2020 were California (889,375 cases), Texas (871,078 cases), Florida (768,091 cases), New York (490,134 cases), and Illinois (363,740 cases). Among the states with the highest proportion of older EPs, Arizona (234,906 cases), Alabama (177,064 cases), Oklahoma (112,483 cases), and Arkansas (102,798 cases) have had a particularly high COVID-19 disease burden (Fig. 1 ).

Table 1.

Emergency physician workforce profile and confirmed COVID-19 cases by state, as of October 22, 2020

| State | EPs age ≥ 60 years; n (%) | Total EPs per state | State population per EP | Confirmed COVID-19 cases by state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Virginia | 95 (40.6) | 236 | 7652 | 21,061 |

| New Mexico | 108 (33.9) | 319 | 6569 | 39,377 |

| Vermont | 41 (33.3) | 123 | 5092 | 1987 |

| Hawaii | 91 (33.1) | 275 | 5165 | 14,335 |

| Maine | 95 (32.9) | 290 | 4615 | 6063 |

| Oklahoma | 110 (32.5) | 342 | 11,529 | 112,483 |

| Montana | 54 (32.0) | 169 | 6286 | 25,640 |

| Alabama | 128 (31.9) | 401 | 12,189 | 177,064 |

| Arkansas | 80 (31.3) | 256 | 11,773 | 102,798 |

| Arizona | 274 (29.9) | 917 | 7821 | 234,906 |

| Mississippi | 90 (29.5) | 305 | 9792 | 112,123 |

| Tennessee | 203 (29.4) | 690 | 9812 | 237,907 |

| Idaho | 67 (29.1) | 231 | 7594 | 55,650 |

| New Hampshire | 68 (29.1) | 234 | 5797 | 9994 |

| Florida | 764 (29.0) | 2641 | 8065 | 768,091 |

| Kentucky | 149 (28.7) | 520 | 8593 | 92,299 |

| Wyoming | 23 (28.0) | 84 | 6878 | 10,119 |

| Washington | 296 (27.4) | 1082 | 6965 | 100,525 |

| Indiana | 208 (27.3) | 763 | 8770 | 155,246 |

| Pennsylvania | 498 (27.3) | 1832 | 6991 | 193,401 |

| Missouri | 196 (27.1) | 725 | 8450 | 163,275 |

| South Carolina | 194 (26.9) | 720 | 7061 | 167,485 |

| California | 1418 (26.1) | 5445 | 7265 | 889,375 |

| Ohio | 434 (25.8) | 1681 | 6954 | 190,430 |

| Iowa | 62 (25.1) | 251 | 12,574 | 111,578 |

| Colorado | 268 (25.0) | 1074 | 5303 | 90,199 |

| Georgia | 285 (25.0) | 1139 | 9236 | 345,535 |

| Kansas | 63 (24.7) | 256 | 11,373 | 73,968 |

| Wisconsin | 196 (24.6) | 798 | 7285 | 186,100 |

| Oregon | 190 (24.5) | 778 | 5387 | 40,443 |

| Michigan | 393 (24.4) | 1621 | 6167 | 170,076 |

| Virginia | 283 (24.4) | 1158 | 7356 | 169,566 |

| Massachusetts | 303 (24.3) | 1247 | 5535 | 147,215 |

| Connecticut | 123 (23.9) | 515 | 6937 | 65,373 |

| New Jersey | 241 (23.9) | 1010 | 8820 | 224,385 |

| Illinois | 425 (23.8) | 1787 | 7130 | 363,740 |

| Louisiana | 150 (23.5) | 637 | 7316 | 178,171 |

| Nevada | 88 (23.0) | 384 | 7902 | 92,853 |

| South Dakota | 19 (22.9) | 83 | 10,629 | 36,017 |

| Alaska | 30 (22.1) | 136 | 5422 | 11,835 |

| North Dakota | 19 (21.8) | 87 | 8737 | 35,052 |

| Maryland | 198 (21.7) | 915 | 6604 | 137,979 |

| North Carolina | 284 (20.7) | 1375 | 7552 | 252,992 |

| Minnesota | 157 (20.4) | 770 | 7287 | 128,152 |

| New York | 542 (19.6) | 2777 | 7037 | 490,134 |

| Delaware | 24 (19.4) | 124 | 7800 | 23,528 |

| Utah | 83 (19.4) | 427 | 7403 | 99,549 |

| Texas | 635 (19.1) | 3334 | 8609 | 871,078 |

| Nebraska | 29 (18.1) | 160 | 12,058 | 60,308 |

| Rhode Island | 30 (16.0) | 187 | 5654 | 29,594 |

| U.S. (total) | 10,804 (24.9) | 43,311 | N/A | 8,392,628 |

Abbreviations: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; EP, emergency physician.

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of emergency physicians age ≥ 60 years and cumulative COVID-19 case distribution, as of October 22, 2020.

States were grouped into color-coordinated quintiles based on relative proportion of older EPs, and cumulative COVID-19 case volumes were adjusted with a logarithmic scale to create proportionally-sized data points.

Fig. 1 provides a geospatial representation of the risk faced by older EPs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Given the 2.5-fold difference in the proportion of older EPs across states (16.0% to 40.6%), and in light of reported personal protective equipment (PPE) shortages among major U.S. distributors [6], supply chain prioritization toward EPs in higher-risk states warrants consideration, especially as cases continue to surge. Emergency departments could also amend operations to prioritize reduction of nosocomial transmission risk among advanced age EPs (e.g., allocating critically limited PPE to higher-risk physicians, geographically cohorting patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 infection within an emergency department) [7]. Furthermore, prioritization of routine COVID-19 testing of older EPs, as well as creation of reserve pools of emergency medicine physicians (e.g., EPs from hospital systems relatively less affected by COVID-19), may facilitate the transfer of care duties from older EPs at more heavily affected emergency departments, in the event that they test positive and need to safely self-isolate [8].

Study limitations include not controlling for other individual factors associated with increased COVID-19 severity (e.g., obesity, Black race, Hispanic ethnicity) [9,10], as well as using state-level data, which precludes insights into risk differences by, for example, rural/urban status. Moreover, we acknowledge that utilizing cumulative case volumes does not account for differences in the present rate of COVID-19 spread between states (e.g., rate of COVID-19 spread and confirmed case count in New York have since stabilized from March/April 2020) [1]. Finally, we understand that COVID-19 infection among younger clinicians is a serious problem. Our hope is that the current findings will raise awareness among EPs and assist implementation of safety guidelines and workforce planning. Collectively, we need to ensure that all front-line EPs, including those at higher risk, are properly protected during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Financial disclosure

The authors report no funding sources relevant to this work.

Author contributions statement

DXZ and TKJ conceived the study and supervised data collection. EJM assisted in data collection. CAC provided advice on study design. DXZ drafted the manuscript, and all authors contributed substantially to its revision. DXZ and CAC take responsibility for the paper as a whole.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this work.

References

- 1.The COVID Tracking Project. https://covidtracking.com/

- 2.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.State Physician Workforce Data Report. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/data/2019-state-profiles

- 4.ESRI COVID-19 Resources. https://coronavirus-resources.esri.com/

- 5.United States Census Bureau TIGERweb. https://tigerweb.geo.census.gov/tigerwebmain/TIGERweb_apps.html

- 6.The American College of Emergency Physicians Guide to Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) https://www.acep.org/corona/covid-19-field-guide/cover-page/

- 7.Whiteside T., Kane E., Aljohani B., Alsamman M., Pourmand A. Redesigning emergency department operations amidst a viral pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1448–1453. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehrlich H., McKenney M., Elkbuli A. Protecting our healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(7):1527–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhu Z., Hasegawa K., Ma B., Fujiogi M., Camargo C.A., Jr., Liang L. Association of obesity and its genetic predisposition with the risk of severe COVID-19: analysis of population-based cohort data. Metabolism. 2020;112:154345. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2020.154345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirby T. Evidence mounts on the disproportionate effect of COVID-19 on ethnic minorities. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):547–548. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]