Abstract

Background/Aims

This study examined the risk factors associated with mortality in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding, and evaluated the effects of acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) on the prognosis of these patients.

Methods

This study was retrospectively conducted on patients registered in the Korean acute-on-chronic liver failure study cohort, and on 474 consecutive cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding from January 2013 to December 2013 at 21 university hospitals. ACLF was defined as described by the European Association for the Study of Liver-Chronic Liver Failure Consortium.

Results

Among a total of 474 patients, 61 patients were diagnosed with ACLF. The cumulative overall survival (OS) rate was lower in the patients with ACLF than in those without (P<0.001), and patients with higher ACLF grades had a lower OS rate (P<0.001). The chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment (CLIF-SOFA) score was identified as a significant prognostic factor in patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding (hazard ratio [HR], 1.40; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.30–1.50; P<0.001), even in ACLF patients with variceal bleeding (HR, 1.32; 95% CI, 1.19–1.46, P<0.001). Concerning the prediction of the mortality risk at 28- and 90-day using CLIF-SOFA scores, c-statistics were 0.895 (95% CI, 0.829–0.962) and 0.897 (95% CI, 0.842–0.951), respectively, and the optimal cut-off values were 6.5 and 6.5, respectively.

Conclusions

In cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding, the prognosis was poor when accompanied by ACLF, especially depending upon CLIF-SOFA score. CLIF-SOFA model well predicted the 28-day or 90-day mortality for cirrhotic patients who experienced variceal bleeding.

Keywords: Acute-on-chronic liver failure, Variceal bleeding, Prognosis, Sequential organ failure assessment

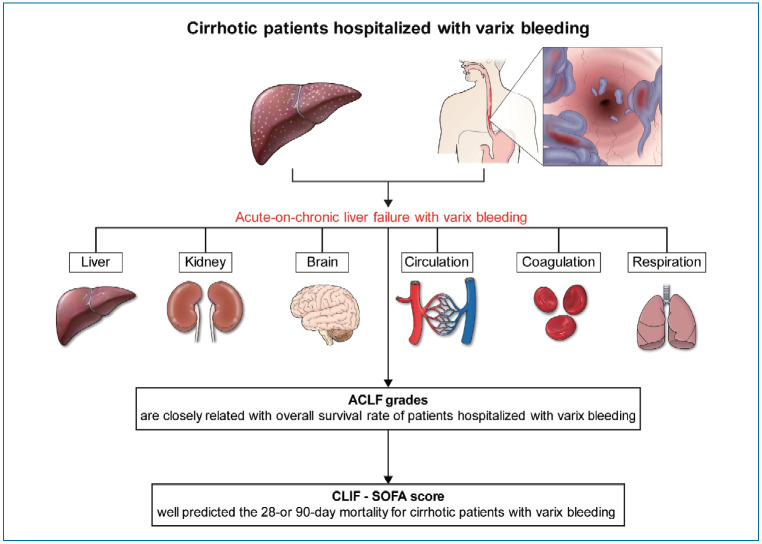

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Variceal bleeding is a critical complication in patients with liver cirrhosis (LC) [1], and accounts for one-third of all mortalities in this patient population [2-4]. Patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding appear to have poor prognoses because variceal bleeding is likely to be accompanied by multi-organ damage due to blood supply insufficiency. Furthermore, it was reported that variceal bleeding associated organ damages were main causes of death in patients with variceal bleeding, even in those that recover completely from variceal bleeding [5-7]. Therefore, in order to investigate the prognoses of these patients, dysfunctions of organs related to variceal bleeding should be considered carefully in addition to hepatic dysfunction.

Several factors, such as hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG), presence of portal vein thrombosis, cause of underlying chronic liver disease, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), and presence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), have been reported to be associated with the prognosis of patients that have experienced an episode of variceal bleeding [8,9]. Studies in these patients using risk assessment models such as the Child-Turcotte-Pugh (CTP), Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD), and the MELD-sodium (Na) model have been conducted [10-12], but, studies that place focus solely on the liver itself may not sufficiently reflect the prognoses of patients with variceal bleeding.

A recent study concluded upper gastrointestinal bleeding was not a significant risk factor of mortality in cirrhotic patients with acute deterioration or acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) [13], but did not compare the survival outcomes of study subjects with or without ACLF. In addition, the proportion of ACLF patients with upper gastrointestinal bleeding was small as 15 (8.8%), and the study was conducted at a single center. Moreover, of the upper gastrointestinal bleeding, variceal bleeding needs to be differently approached and treated because it is resulted by increased portal hypertension, unlike peptic ulcer bleeding [14].

Therefore, in this multicenter cohort study, we investigated risk factors associated with mortality in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding, and also evaluated the effect of the presence of ACLF on prognosis in these patients. In addition, we tried to identify a more reliable model for predicting mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding based on the use of CTP, MELD, MELD-Na, or the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment (CLIF-SOFA) scores.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Study subjects

Between January and December 2013, a total of 1,861 consecutive adult patients admitted due to the acute deterioration of cirrhosis at 21 hospitals, were enrolled in this study. The definition of acute deterioration was previously described as follows: acute development of overt ascites, HE, gastrointestinal bleeding, infection, or liver dysfunction [15,16], and except for liver dysfunction, this definition was adopted from the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure (EASL-CLIF) Consortium Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis (CANONIC) study [17]. In the present study, we tried to enroll as many patients as possible considering the retrospective study design, and therefore, we set the lower limit for bilirubin with ≥3 mg/dL as the standard used to diagnose jaundice, and defined liver dysfunction as an acute increase in serum bilirubin level of ≥3 mg/dL [18].

ACLF was defined as the development of acute deterioration of liver function in cirrhotic patients who had organ failure (OF) defined by the CLIF-SOFA score and high 28-day mortality rate (>15%) based on CANONIC study [17]. OF was defined based on the CLIF-SOFA score [17], and more in detail, liver failure was defined by an increased serum bilirubin level (≥12 mg/dL); renal failure was defined by an increased serum creatinine level (≥2.0 mg/dL) or by the use of hemodialysis; cerebral failure was defined by severe HE (grade III or IV) based on the West Haven classification; coagulation failure was defined by an increased international normalized ratio (>2.5) and/or a decreased platelet count (<20×109/L); circulatory failure was defined by the use of inotropics (dopamine, dobutamine, or terlipressin); respiratory failure was defined by a PaO2/FiO2 ≤200 or an SpO2/FiO2 ≤200. The CLIF-SOFA score was stratified ranging from 0 to 4 for each of the 6 OFs [17]. ACLF was graded according to the EASL-CLIF consortium diagnostic criteria for ACLF of the CANONIC study [17]. LC was diagnosed based on the histological confirmation, or clinical, imaging, and biochemical findings [19].

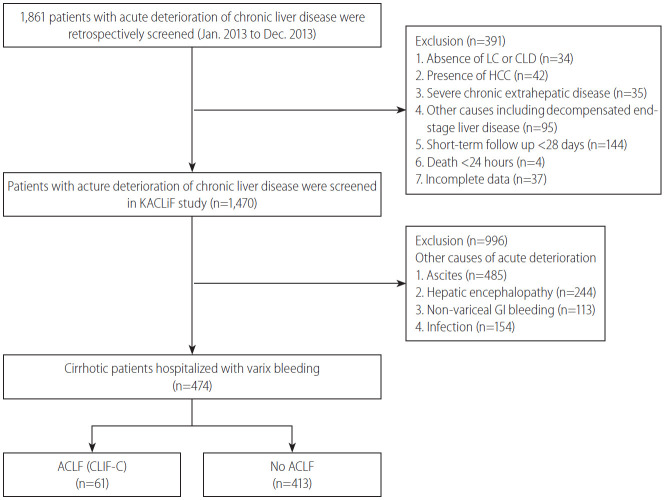

Of the 1,861 patients considered, 350 were excluded for the following reasons; an age of <18 years, absence of cirrhosis, presence of HCC, presence of severe chronic extra-hepatic disease, admission due to other chronic illness, human immunodeficiency virus infection, chronic decompensation of end-stage liver disease, such as ascites over 2 weeks or chronic HE, less than 28 days of follow-up, and incomplete data. Of the remaining 1,470 patients, 996 patients with acute deterioration caused by conditions other than variceal bleeding were also excluded. Patients who had a prior history of variceal bleeding before the study period (n=281) were included in the present study. Therefore, 474 patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding were finally analyzed in this retrospective study (Fig. 1). Follow-up durations were assessed from date of initial admission to date of death or liver transplantation (LT) or to follow-up loss date or June 30, 2014. Patients who received subsequent LT or with follow-up loss were censored. This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and was approved by the Institutional Review Boards at all participating hospitals.

Figure 1.

Flowsheet of the study subjects (n=474). LC, liver cirrhosis; CLD, chronic liver disease; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; KACLiF, the Korean Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure; GI, gastrointestinal; ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; CLIF-C, chronic liver failure consortium.

Acquisition of clinical data

Clinical data, such as age, gender, etiology of cirrhosis, and laboratory results, were obtained from the electronic medical records. The types of events responsible for the acute deterioration, the presence of OF, the occurrence of ACLF, and laboratory results obtained within 24 hours of hospitalization and at the time of ACLF occurrence were evaluated. CTP, MELD, MELD-Na [12], and CLIF-SOFA scores [17] were calculated within 24 hours of hospitalization. Clinical data for ACLF that occurred within 28 days of hospitalization due to the acute deterioration of cirrhosis were analyzed.

Precipitating factors of acute deterioration of cirrhosis were classified as follows: bacterial infection, gastrointestinal bleeding, active alcoholism, exacerbation of underlying viral hepatitis, toxic liver injury, and others. Active alcoholism was considered as >21 drinks/week in men, and >14 drinks/week in women over the 3 months prior to hospitalization [20]. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome was defined according to the diagnostic criteria issued by the American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine [21].

Statistical analyses

Clinical characteristics of the enrolled patients were expressed as medians (ranges) for continuous variables, and numbers (percentages) for categorical variables. Differences between categorical or continuous variables were analyzed using the chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test and the Student’s t test. Short-term mortality was defined as death within 28 days of admission due to variceal bleeding. Overall survival (OS) rates were estimated using Kaplan-Meier method with the log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to evaluate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for mortality. To evaluate the predictive performances of risk prediction models for 28- and 90-day mortality, areas under receiver operating curves (AUROCs), sensitivities, specificities, positive predictive values, and negative predictive values were assessed. Two-tailed P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant, and the statistical analysis was performed using SPSS ver. 19.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics

Baseline clinical characteristics of the 474 study subjects are provided in Table 1, and about 13 percent (n=61) were ACLF patients. Median patient age was 54.8 years and 372 patients were male (78.5%). All patients had variceal bleeding as a complication of cirrhosis, and the most common etiology was alcohol use. No differences were found between patients with or without ACLF with respect to age, gender, or etiology. Serum alanine aminotransferase level (U/L) was not significantly different in these two groups (80.0 vs. 50.4, P=0.186), but serum aspartate aminotransferase level (U/L) (209.0 vs. 98.0, P=0.002), white blood cell (WBC; ×103/uL) count (12.1 vs. 8.3, P<0.001), and C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/dL) (0.64 vs. 0.43, P=0.036) were higher in the ACLF group. Of the acute deterioration events, only HE event was more frequently found in ACLF group (13.1 % vs. 3.1%, P<0.001). Assessments of preserved liver function and organ failure, showed median CTP (10.0 vs. 7.5, P<0.001), MELD (26.3 vs. 13.0, P<0.001), and CLIF-SOFA score (9.8 vs. 3.7, P<0.001) were higher in the ACLF group.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical characteristics of study subjects

| Variable | All (n=474) | Non-ACLF (n=413) | ACLF (n=61) | P-value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 54.8 (17–88) | 54.6 (17–88) | 56.6 (34–84) | 0.202 |

| Gender, male | 372 (78.5) | 323 (78.2) | 49 (80.3) | 0.707 |

| WBC (×103/uL) | 8.8 (0.08–3.01) | 8.3 (0.8–30.1) | 12.1 (3.1–26.9) | <0.001 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 8.6 (2.6–19.1) | 8.7 (2.6–16.8) | 8.0 (3.0–19.1) | 0.048 |

| Platelets (×103/uL) | 102 (12–659) | 102 .3 (12–659) | 102.4 (12–247) | 0.999 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 2.9 (1.3–4.8) | 3.0 (1.5–4.8) | 2.5 (1.3–4.0) | <0.001 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 2.9 (0.2–40.3) | 2.3 (0.2–35.0) | 7.2 (0.3–40.3) | <0.001 |

| AST (IU/L) | 112.2 (4–3,399) | 98.0 (4–3,399) | 209.0 (17–2,620) | 0.002 |

| ALT (IU/L) | 54.2 (4–2,886) | 50.4 (4–2,886) | 80.0 (8–807) | 0.186 |

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.5 (0.9–5.6) | 1.4 (0.9–3.1) | 2.1 (1.0–5.6) | <0.001 |

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.46 (0.01–28.5) | 0.43 (0.1–28.5) | 0.64 (0.03–26.8) | 0.036 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 136.9 (111–162) | 137.3 (111–153) | 134.7 (118–162) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.1 (0.1–11.2) | 0.9 (0.1–1.9) | 2.8 (0.7–11.2) | <0.001 |

| Ascites, presence | 28 (5.9) | 23 (5.6) | 5 (8.2) | 0.416 |

| HE, presence | 21 (4.4) | 13 (3.1) | 8 (13.1) | <0.001 |

| Infection, presence | 5 (1.1) | 3 (0.7) | 2 (3.3) | 0.069† |

| MELD score | 14.7 (6–26) | 13.0 (6–26) | 26.3 (13–47) | <0.001 |

| CTP score | 7.8 (5–15) | 7.5 (5–12) | 10.0 (6–15) | <0.001 |

| CLIF-SOFA score | 4.5 (0–21) | 3.7 (0–10) | 9.8 (3–21) | <0.001 |

| Etiology of CLD | 0.145† | |||

| Viral, HBV or HCV | 92 (19.4) | 85 (20.6) | 7 (11.5) | |

| Alcohol | 320 (67.6) | 271 (65.6) | 49 (80.3) | |

| Viral+alcohol | 31 (6.5) | 28 (6.8) | 3 (4.9) | |

| Others | 31 (6.5) | 29 (7.0) | 2 (3.3) |

Values are presented as median (range) or number (%).

ACLF, acute on chronic liver failure; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CLIF SOFA, the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CLD, chronic liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

P-values were calculated using the t-test or Fisher’s exact test between ACLF and no-ACLF groups.

Fisher’s exact test.

Cumulative survival rates of cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding

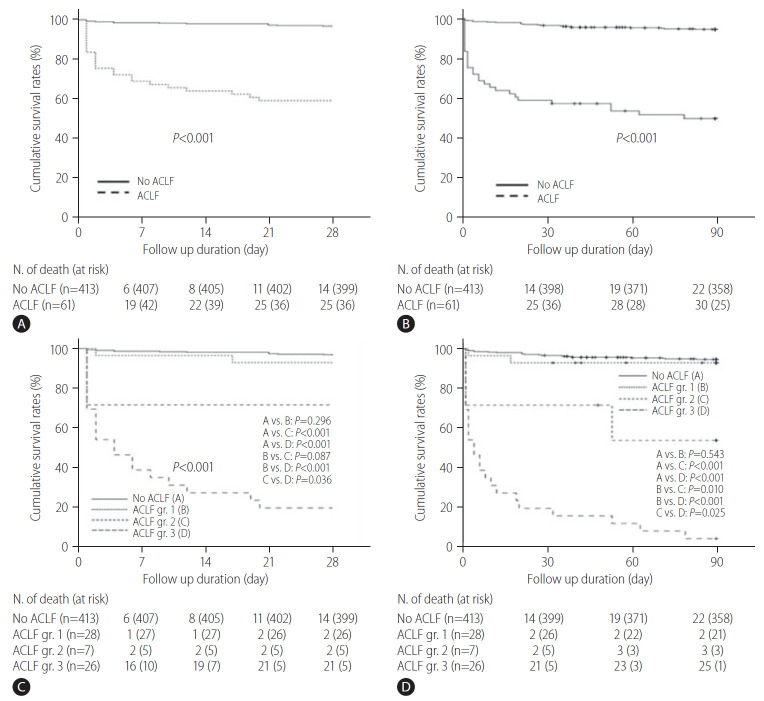

Median follow up for all study subjects was 216 days (range, 1–611). Among all 474 patients, 52 patients were died during a 90-day follow-up period and cumulative OS rates at 28- and 90-days were 91.8% and 88.1%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1). When compared between patients with and without ACLF, 14 and 25 patients were died during a 28-day follow-up period of the patients with and without ACLF, respectively (Fig. 2A), and 22 and 30 patients were died during a 90-day follow-up period of the patients with and without ACLF, respectively (Fig. 2B). The 28- and 90-day cumulative OS rates were significantly lower in patients with ACLF than in those without ACLF, respectively (59.0% vs. 96.6%, P<0.001; and 50.8% vs. 94.7%, P<0.001; respectively) (Fig. 2A, B). To evaluate the prognostic effects of ACLF grade on survival outcomes of the enrolled patients, we compared OS rates of the patients according to the ACLF grade, defined as described by the EASL-CLIF consortium (Fig. 2C, D). During a 28- day follow-up period, 14, two, two, and 21 patients were died among patients without ACLF, and with ACLF grade I, II, and III, respectively (Fig. 2C). During a 90-day follow-up period, 22, 2, 3, and 25 patients were died among patients without ACLF, and with ACLF grade I, II, and III, respectively (Fig. 2D). The 28-day cumulative OS rates of patients without ACLF or with ACLF grade I were almost 90%, and no significant difference was found between these two groups (Fig. 2C, P=0.296), and these results were similar in analysis for the 90-day cumulative OS rates (Fig. 2D, P=0.543). The 28-day cumulative OS rates of patients with ACLF grade III tended to be lower than those with ACLF grade II (Fig. 2C, P=0.087), and 90-day cumulative OS rates of patients with ACLF grade III were significantly lower than those with ACLF grade II (Fig. 2D, P=0.010). In addition, patients with ACLF grades II or III had significantly lower 28-day and 90-day OS rates than those without ACLF or with ACLF grade I, respectively (all P-values <0.001) (Fig. 2C, D). In particular, the 90-day cumulative OS rate of patients with ACLF grade III was very low at <10% (Fig. 2D). In subgroup analysis for causes of mortality in the study subjects, most patients died due to hepatic failure or varix bleeding (Supplementary Table 1).

Figure 2.

Cumulative overall survival rates of cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding. The 28-day (A) and 90-day (B) cumulative OS rates were significantly lower in patients with ACLF than in those without ACLF, respectively (59.0% vs. 96.6%, P<0.001, and 50.8% vs. 94.7%, P<0.001, respectively). (C) The 28-day cumulative OS rates of patients with ACLF grade III tended to be lower than those with ACLF grade II (P=0.087). (D) The 90-day cumulative OS rates of patients with ACLF grade III were significantly lower than those with ACLF grade II (P=0.010). ACLF, acute-on-chronic liver failure; gr, grade; OS, overall survival.

Risk factors for 28-day mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding

To identify risk factors for mortality within 28-day in all patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding (n=474), univariable analysis was performed, and WBC, albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time (PT), sodium, creatinine, presence of HE, MELD score, CTP score, and CLIF-SOFA score were found to be significant (P-values for all <0.01) (Table 2). On the other hand, total bilirubin and PT are common individual components of CTP, MELD, and CLIF-SOFA, and creatinine was one of the components of the MELD or CLIF-SOFA score. In addition, HE was one of the components of the CLIF-SOFA score. Thus, only the WBC, albumin, sodium, and CLIF-SOFA score were used for multivariable analysis in this study. Multivariable analysis showed that CLIF-SOFA (HR, 1.40; 95% CI, 1.30–1.50; P<0.001) was a significant predictor of the 28-day mortality in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with varix bleeding (Table 2). In order to identify more pivotal factors among the individual components that make up the CLF-SOFA scores, subgroup analysis was performed (Supplementary Table 2). Creatinine, HE, and PT were significant predictors for the 28-day mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding.

Table 2.

Risk factors for 28 days mortality in all patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding (n=474)*

| Variable | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 1.00 (0.98–1.03) | 0.828 | ||

| Gender, male | 0.65 (0.27–1.56) | 0.335 | ||

| WBC (×103/uL) | 1.14 (1.09–1.20) | <0.001 | 1.03 (0.97–1.10) | 0.282 |

| Hb (g/dL) | 0.97 (0.85–1.09) | 0.581 | ||

| Platelets (×103/uL) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.828 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.16 (0.09–0.29) | <0.001 | 0.64 (0.31–1.31) | 0.219 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.10 (1.07–1.13) | <0.001 | ||

| AST (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.062 | ||

| ALT (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.277 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 3.19 (2.48–4.10) | <0.001 | ||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 1.06 (0.99–1.13) | 0.071 | ||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 0.93 (0.89–0.98) | 0.004 | 1.03 (0.98–1.09) | 0.222 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.43 (1.27–1.60) | <0.001 | ||

| Ascites, presence | 2.99 (1.25–7.15) | 0.013 | ||

| HE, presence | 6.57 (3.02–14.31) | <0.001 | ||

| MELD score | 1.14 (1.11–1.17) | <0.001 | ||

| CTP score | 1.90 (1.63–2.21) | <0.001 | ||

| CLIF-SOFA score | 1.44 (1.36–1.53) | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.30–1.50) | <0.001 |

HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CLIF SOFA, the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment.

Subjects (n=474), event: death (n=39).

In addition, the risk factors for the 28-day mortality in ACLF patients with varix bleeding (n=61) were analyzed (Table 3). Univariable analysis showed that the albumin, PT, MELD score, CTP score, and CLIF-SOFA score were to be significant (P-values for all <0.05). For the same reasons mentioned above, albumin (P=0.023) and the CLIF-SOFA score (P<0.001) were used in multivariable analysis, and only CLIF-SOFA (HR, 2.19; 95% CI, 1.47–3.24; P<0.001) was found to be a significant predictor of the 28-day mortality in these patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Risk factors for 28 days mortality in ACLF patients with variceal bleeding (n=61)*

| Variable | Univariable analysis |

Multivariable analysis |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | P-value | HR (95% CI) | P-value | |

| Age (years) | 0.98 (0.94–1.02) | 0.251 | ||

| Gender, male | 1.38 (0.47–4.02) | 0.554 | ||

| WBC (×103/uL) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.096 | ||

| Hb (g/dL) | 1.00 (0.87–1.15) | 0.955 | ||

| Platelets (×103/uL) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.605 | ||

| Albumin (g/dL) | 0.37 (0.16–0.88) | 0.023 | 0.72 (0.30–1.71) | 0.455 |

| Bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.03 (0.99–1.07) | 0.127 | ||

| AST (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.538 | ||

| ALT (IU/L) | 1.00 (0.99–1.01) | 0.182 | ||

| Prothrombin time (INR) | 1.68 (1.21–2.33) | 0.002 | ||

| CRP (mg/dL) | 0.99 (0.91–1.08) | 0.815 | ||

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.673 | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 1.00 (0.82–1.22) | 0.970 | ||

| Ascites, presence | 1.21 (0.29–5.16) | 0.792 | ||

| HE, presence | 1.82 (0.68–4.86) | 0.231 | ||

| MELD | 1.06 (1.01–1.11) | 0.010 | ||

| CTP score | 1.32 (1.08–1.62) | 0.006 | ||

| CLIF-SOFA | 1.33 (1.21–1.47) | <0.001 | 1.32 (1.19–1.46) | <0.001 |

| Etiology of CLD | ||||

| Viral, HBV or HCV | 1 | |||

| Alcohol | 1.56 (0.37–6.66) | 0.547 | ||

| Viral+alcohol | 3.24 (0.45–23.09) | 0.241 | ||

| Others | 0.01 (0.01–0.02) | 0.985 | ||

ACLF, acute on chronic liver failure; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; WBC, white blood cell; Hb, hemoglobin; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; INR, international ratio; CRP, C-reactive protein; HE, hepatic encephalopathy; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; CLIF SOFA, the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CLD, chronic liver disease; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Subjects (n=61), event: death (n=25).

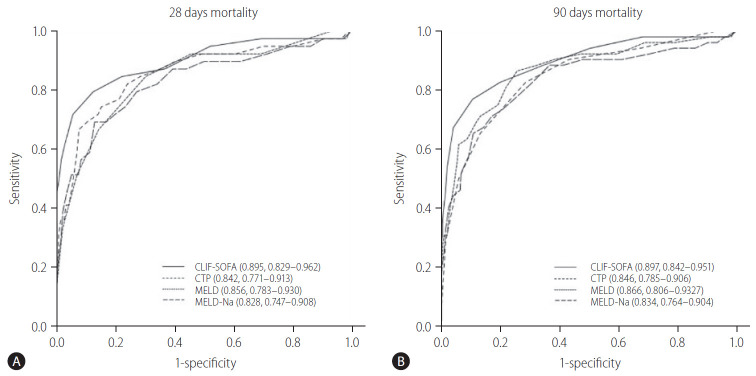

Predictive performances of the risk prediction models for 28- and 90-day mortalities in patients with variceal bleeding

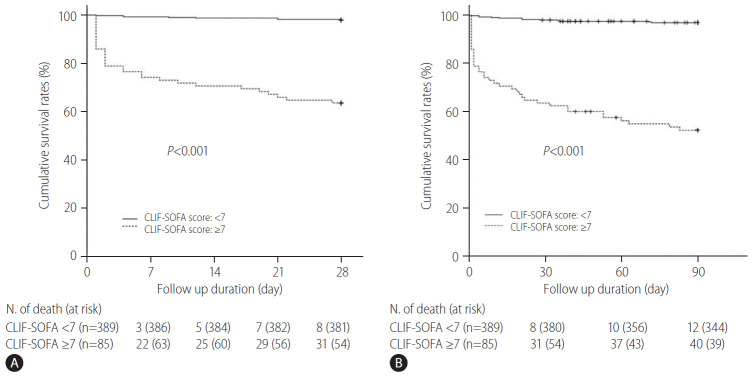

To assess the prognostic role of the CLIF-SOFA scores on the 28- and 90-day mortalities in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding, we compared the predictive performances of CLIF-SOFA scores with those of the CTP, MELD, and MELD-Na scores (Table 4). As compared to CTP, MELD, and MELD-Na scores, the AUROCs estimated for CLIF-SOFA scores for the prediction of 28- and 90-day mortality were higher, respectively, and exhibited about 3–7% better discriminatory abilities than those of the CTP, MELD, MELD-Na scores (Table 4, Fig. 3). With regard to the prediction of mortality risk at 28- and 90-day using CLIF-SOFA scores, the AUROCs were 0.895 (95% CI, 0.829–0.962) and 0.897 (95% CI, 0.842–0.951), respectively, and optimal cut-off values were 6.5 and 6.5, respectively (Table 4). Using these optimal cut-off values, patients were dichotomized into two groups based on the CLIF-SOFA scores of <7 or ≥7 (Fig. 4). The 28- and 90-day cumulative OS rates of the patients with CLIF-SOFA scores ≥7 were found to be significantly lower than those with CLIF-SOFA score <7, respectively (P-values for all <0.001) (Fig. 4). In addition, we also compared the AUROC for the CLIF-SOFA scores for the prediction of the 28- and 90-day mortality with those for the chronic liver failure consortium (CLIF-C) OF and CLIF-C acute liver failure (ALF) scores (Supplementary Fig. 2). The AUROCs of the CLIP-SOFA score for predicting the 28- and 90-day mortality were higher than those of the CLIF-C OF (0.860 [95% CI, 0.793–0.928] and 0.862 [95% CI, 0.784–0.939], respectively) and CLIF-C ALF (0.849 [95% CI, 0.787–0.910] and 0.871 [95% CI, 0.799–0.944], respectively) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Table 4.

Predictive performance of risk prediction models for 28- and 90-day mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding

| CTP score | MELD score | MELD-Na score | CLIP-SOFA score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mortality risk at 28 days | ||||

| AUROC | 0.842 (0.711–0.914) | 0.857 (0.783–0.931) | 0.828 (0.746–0.909) | 0.895 (0.829–0.962) |

| Optimal cut-off value | 8.5 | 18.5 | 22.5 | 6.5 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 84.6 (71.8–94.9) | 74.4 (61.5–87.2) | 69.2 (53.8–84.6) | 79.5 (66.7–92.3) |

| Specificity (%) | 69.9 (65.6–74.3) | 84.8 (81.4–88.3) | 87.1 (83.9–90.1) | 87.6 (84.4–90.6) |

| PPV (%) | 20.1 (17.1–23.5) | 30.5 (24.8–37.5) | 32.6 (25.6–40.2) | 36.3 (30.0–44.0) |

| NPV (%) | 98.1 (96.7–99.4) | 97.4 (96.0–98.7) | 96.9 (95.4–98.4) | 97.9 (96.7–99.2) |

| Mortality risk at 90 days | ||||

| AUROC | 0.846 (0.786–0.906) | 0.867 (0.806–0.927) | 0.834 (0.764–0.904) | 0.897 (0.842–0.951) |

| Optimal cut-off value | 8.5 | 15.5 | 22.5 | 6.5 |

| Sensitivity (%) | 82.7 (71.2–92.3) | 86.5 (76.9–94.2) | 65.4 (53.8–78.8) | 76.9 (65.4–86.5) |

| Specificity (%) | 71.6 (66.9–76.3) | 74.5 (70.1–78.6) | 89.3 (85.9–92.4) | 89.6 (86.2–92.7) |

| PPV (%) | 28.3 (24.4–32.7) | 31.5 (27.5–36.0) | 45.3 (37.2–54.8) | 50.6 (42.4–59.2) |

| NPV (%) | 96.8 (94.9–98.6) | 97.6 (95.9–99.0) | 95.0 (93.3–96.8) | 96.7 (95.0–98.1) |

Values are presented as number (95% confidence interval).

CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; Na, sodium; CLIF-SOFA, the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; AUROC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value.

Figure 3.

Areas under the receiver operating curves of the risk prediction models for the 28- and 90-day mortalities in patients with variceal bleeding. With regard to the prediction of mortality risk at 28-day (A) and 90-day (B) using the CLIF-SOFA scores, AUROCs were 0.895 (95% CI, 0.829–0.962) and 0.897 (95% CI, 0.842–0.951), respectively. CLIF-SOFA, chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CTP, Child-Turcotte-Pugh; MELD, model of end-stage liver disease; Na, sodium; AUROC, areas under receiver operating curves; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 4.

Cumulative overall survival rates of patients according to the CLIF-SOFA scores (<7 or ≥7). The 28-day (A) and 90-day (B) cumulative OS rates of patients with a CLIF-SOFA score ≥7 were found to be significantly lower than those with a CLIF-SOFA score <7, respectively (P-values for all <0.001). CLIF-SOFA, chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment.

DISCUSSION

In this multicenter cohort study, we found that median WBC count and CRP level were higher, and median hemoglobin (Hb) levels were lower in ACLF patients with variceal bleeding than in those without, and the CTP and MELD scores were higher in patients with ACLF. Furthermore, the cumulative OS rates of the patients with variceal bleeding were significantly lower in those with ACLF, and lower in those with a higher ACLF grade. Multivariable analysis showed the CLIF-SOFA score was the only prognostic factors of short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, and that the CLIF-SOFA score was a prognostic factor of short-term mortality in ACLF patients with variceal bleeding. Interestingly, the CLIF-SOFA score was found to more reliably predict the 28- and 90-day mortalities, respectively, than the CTP, MELD, or MELD-Na scores in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding. Given there are few studies that provide a role of the CLIF-SOFA score influencing mortality of ACLF patients induced by variceal bleeding, this study has some strengths. First, this study provided the prognostic role of CLIF-SOFA score with regard to the short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, even in ACLF patients with variceal bleeding. Second, this study was conducted in a multi-center, and analyzed a relatively large number of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, even in ACLF patients.

In the present study, the cumulative 28-day survival rate of the patients with ACLF admitted with variceal bleeding was lower than that of ‘all cause’ ACLF patients reported in the previous study [22]. However, our result was similar to that (63.6%) reported in another previous study, which evaluated the mortality within 6 weeks after variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients with or without ACLF [7]. These outcomes suggest the prognosis of ACLF patients with variceal bleeding may be poorer than that of ACLF patients with other causes. In addition, as reported in a previous study [23], hypoxic hepatitis can occur in patients with variceal bleeding, and the 6-week mortality of patients with hypoxic hepatitis was as high as 83.3%, which is significantly higher than the 24.6% mortality of patients without hypoxic hepatitis. Interestingly, although the data for ischemic hepatitis were not collected in the present study, the CLIF-SOFA score, which reflects organ failure, significantly predicted the short-term mortality of cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, even in ACLF patients, which is in-line with the results of a previous study [17], and which suggests that bleeding-induced hypovolemic change may have caused the ischemic damage, and promoted multi-organ failure [23-25]. In the present study, patients with ACLF had significantly lower Hb and albumin levels, respectively, than patients without ACLF, but multivariable analysis showed these two factors did not significantly predict short-term mortality in cirrhotic patients admitted with variceal bleeding, even in ACLF patients. However, at this point, it should be considered that these two factors can be corrected by a red blood cell transfusion or albumin replacement, suggesting that rapid correction of these variables may prevent hypoxic hepatitis or hemodynamic instability as well as have a good effect on the patients’ survival. Furthermore, these findings indicate that organ failure rather than Hb or albumin levels itself, may have a more important effect on the survival of patients with variceal bleeding. Therefore, patients with higher CLIF-SOFA scores should be carefully managed, and liver transplantation requirements should be prepared at an early stage.

This study evaluated the prognostic effects of the ACLF grade on the survival outcomes of the cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, and compared the OS rates of these patients with respect to the ACLF grade. With regard to the short-term prognoses, we found that the OS rates of the patients with higher ACLF grades were lower than those of the patients with a lower ACLF grade or no ACLF. In particular, patients with ACLF grade III showed the lowest survivals, and in fact, most with variceal bleeding succumbed within 7 days of admission, which suggests that these patients should be registered as transplantation recipients as early as possible. Moreover, these patients need to be carefully managed to prevent progression to organ failure and to actively correct the reversible factors, such as infections, hemodynamics, Hb level, and serum creatinine and albumin levels. On the other hand, OS rates of the patients with ACLF grade I and patients without ACLF were not different. This suggests the kidney failure in patients of ACLF grade I due to variceal bleeding may be of the pre-renal type, resulting from hypovolemia induced by blood loss associated with variceal bleeding. Moreover, fluid resuscitation or red blood cell transfusion may recover these patients from transient renal failure [26]. Patients with ACLF grade II showed poorer survival rate than those with ACLF grade I on the graph (Fig. 2C), but only a trend toward statistical differences was noted (P=0.087). This lack of significance may have been caused by the small number of patients with ACLF grade II. Nevertheless, as the follow-up duration increased, this difference achieved statistical significance (Fig. 2D). Therefore, ACLF grading based on the EASL-CLIF consortium may assist in treatment decision making in cirrhotic patients admitted with variceal bleeding.

In recent systemic reviews and a meta-analysis, the CTP and MELD scores were found to produce similar prognostic values in patients with LC [27]. On the other hand, when extrahepatic organ dysfunction began to develop, the extent of organ dysfunction was probably more important for the prognosis of ACLF patients than the severity of liver disease [28-30]. In another study, it was reported that a high HVPG (≥20 mmHg) importantly predicted rebleeding and a poor prognosis in patients with variceal bleeding [8,31,32]. However, HVPG measurements involve a relatively invasive procedure, and thus, cannot be used routinely in patients with variceal bleeding. Therefore, a straightforward, non-invasive means of accurately predicting the prognosis of ACLF patients is required. Interestingly, the CLIF-SOFA score predicted 28- and 90-day mortalities well in ACLF patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding. This suggests that active treatment may be needed to improve the prognosis of such patients with a CLIF-SOFA score of ≥7. The CLIF-SOFA score should be sequentially observed to predict the prognosis of patients with variceal bleeding.

In this study, the WBC count and CRP levels were elevated more in patients with ACLF than in those without. However, the infection incidence rate was relatively low in the patients admitted with variceal bleeding, and no significant difference was observed between the patients with or without ACLF. In a previous study, it was reported neutrophil dysfunction with elevated WBC and reduced phagocytic activity was associated with increased rates of infection, organ failure, and mortality in patients with cirrhosis [33]. Furthermore, pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to influence the development of ACLF [34,35] by promoting the development of multiple organ failure via progressive vasodilatory shock. Therefore, an increase in the WBC counts or CRP levels without evidence of infection may be related to the development of ACLF due to increased pro-inflammatory cytokines production [35]. However, further studies will be needed to elucidate the mechanism responsible for the WBC and CRP elevations in the context of the development of ACLF in patients with variceal bleeding.

The present study has some limitations that warrant consideration. First, this study is inherently limited because it was based on a cohort of retrospective the Korean Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure (KACLiF) studies. Although the KACLiF study group attempted to register as many patients with acute exacerbations of cirrhosis as possible, selection bias cannot be ruled out completely. Moreover, detailed clinical information about the bleeding focus (esophageal vs. gastric varix), bleeding prophylaxis before admission, pre-emptive transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt, technical problems (exact time to endoscopic therapy, endoscopist’s skill, treatment modality, re-bleeding rate, and availability of alternative treatments after the failure of initial hemostasis), and the transfusion volume could not be obtained. This limitation should be overcome by a prospective study. Second, this study evaluated relatively short-term mortality rates, and thus, was not able to provide information on long-term prognoses. However, if ACLF patients overcome well the acute phase, they can remain stable in the long term. Gustot et al. [36] reported that the 90- and 180-day mortalities of ACLF patients are not different, and another study reported that >50% of deaths occurred within 100 days [13]. Thus, we would argue prognostic analysis beyond 90 days in ACLF patients is probably not clinically relevant. Third, the number of ACLF patients included in the present study was relatively small. However, in view of recent developments made in emergency endoscopic treatment, radiologic interventions, pharmacological drugs, or active intensive care unit management strategies related to the treatment of variceal bleeding, the incidence of ACLF in cirrhotic patients due to variceal bleeding is likely to decrease despite the large number of patients involved [37]. Therefore, the clinical significance of the present study is that the CLIF-SOFA score might helpfully be used to predict the prognoses of variceal bleeding patients, even of patients with ACLF. Nonetheless, further study is required to validate these findings.

In conclusion, the development of ACLF in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding was associated with a poor prognosis. Notably, higher CLIF-SOFA scores were associated with a poorer prognosis, and the optimal CLIF-SOFA cut-off score for predicting mortality risk at 28-days was 6.5. Furthermore, the CLIF-SOFA scores were found to more accurately predict 28- and 90-day mortalities for cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, respectively, than CTP, MELD, or MELD-Na scores. These findings provide useful information regarding the early prediction of survival among cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding, and for deciding whether the patients should be registered early as potential transplant recipients. However, to validate the outcomes of this study, we are currently compiling a large-scaled prospective cohort.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by an Inha University Research Grant.

Abbreviations

- ACLF

acute-on-chronic liver failure

- AUROC

the area under the receiver operating curve

- CANONIC

Consortium Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure in Cirrhosis

- CI

confidence interval

- CLIF-C

chronic liver failure consortium

- CLIF-SOFA

the chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CTP

Child-Turcotte-Pugh

- EASL-CLIF

the European Association for the Study of the Liver-Chronic Liver Failure

- Hb

hemoglobin

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HE

hepatic encephalopathy

- HR

hazard ratio

- HVPG

hepatic venous pressure gradient

- KACLiF

the Korean Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure

- LC

liver cirrhosis

- LT

liver transplantation

- MELD

model of end-stage liver disease

- Na

sodium

- OF

organ failure

- OS

overall survival

- PT

prothrombin time

- WBC

white blood cell

Study Highlights

1. The development of ACLF in cirrhotic patients hospitalized with variceal bleeding was associated with a poor prognosis.

2. Higher CLIF-SOFA scores were associated with a poorer prognosis, and the optimal CLIF-SOFA cut-off score for predicting mortality risk at 28-days was 6.5.

3. The CLIF-SOFA scores were found to more accurately predict 28- and 90-day mortalities for cirrhotic patients with variceal bleeding, respectively, than CTP, MELD, or MELD-Na scores.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

J Shin, JH Yu, and YJ Jin were responsible for the concept and design of the study, the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting the manuscript. HJ Yim, YK Jung, JM Yang, DS Song, YS Kim, SG Kim, DJ Kim, KT Suk, E Yoon, SS Lee, CW Kim, HY Kim, JY Jang, and SW Jeong helped with the data acquisition.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Clinical and Molecular Hepatology website (http://www.e-cmh.org).

Cumulative overall survival rates of all patients. Cumulative OS rates at 28- and 90-days were 91.8% and 88.1%, respectively. OS, overall survival.

Areas under the receiver operating curves of the CLIF-SOFA score compared to CLIF-C OF and CLIF-C ALF for the 28- and 90-day mortalities in patients with variceal bleeding. AUROCs of CLIP-SOFA score for predicting the 28-day (A) and 90-day (B) mortality were higher than those of CLIF-C OF (0.860 [95% CI, 0.793–0.928] and 0.862 [95% CI, 0.784–0.939], respectively) and CLIF-C ALF (0.849 [95% CI, 0.787–0.910] and 0.871 [95% CI, 0.799–0.944], respectively). CLIF-SOFA, chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CLIF-C, chronic liver failure consortium; OF, organ failure; ALF, acute liver failure; AUROC, areas under receiver operating curves; CI, confidence interval.

Cause of motality for 28- and 90-day in all patients with variceal bleeding (n=474)

CLIF-SOFA variables as risk factors for 28-day mortality in all patients with variceal bleeding (n=474)*

REFERENCES

- 1.Graham DY, Smith JL. The course of patients after variceal hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Amico G, Pagliaro L, Bosch J. Pharmacological treatment of portal hypertension: an evidence-based approach. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:475–505. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YD. Management of acute variceal bleeding. Clin Endosc. 2014;47:308–314. doi: 10.5946/ce.2014.47.4.308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Villanueva C, Piqueras M, Aracil C, Gómez C, López-Balaguer JM, Gonzalez B, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing ligation and sclerotherapy as emergency endoscopic treatment added to somatostatin in acute variceal bleeding. J Hepatol. 2006;45:560–567. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krige JE, Kotze UK, Bornman PC, Shaw JM, Klipin M. Variceal recurrence, rebleeding, and survival after endoscopic injection sclerotherapy in 287 alcoholic cirrhotic patients with bleeding esophageal varices. Ann Surg. 2006;244:764–770. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000231704.45005.4e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krige JE, Shaw JM, Bornman PC, Kotze UK. Early rebleeding and death at 6 weeks in alcoholic cirrhotic patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with emergency endoscopic injection sclerotherapy. S Afr J Surg. 2009;47:72-74, 76-79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teng W, Chen WT, Ho YP, Jeng WJ, Huang CH, Chen YC, et al. Predictors of mortality within 6 weeks after treatment of gastric variceal bleeding in cirrhotic patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e321. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abraldes JG, Villanueva C, Bañares R, Aracil C, Catalina MV, Garci A-Pagán JC, et al. Hepatic venous pressure gradient and prognosis in patients with acute variceal bleeding treated with pharmacologic and endoscopic therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;48:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomopoulos K, Theocharis G, Mimidis K, Lampropoulou-Karatza C, Alexandridis E, Nikolopoulou V. Improved survival of patients presenting with acute variceal bleeding. Prognostic indicators of short- and long-term mortality. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chalasani N, Kahi C, Francois F, Pinto A, Marathe A, Bini EJ, et al. Model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) for predicting mortality in patients with acute variceal bleeding. Hepatology. 2002;35:1282–1284. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang J, Wang AJ, Li BM, Liu ZJ, Chen L, Wang H, et al. MELDNa: effective in predicting rebleeding in cirrhosis after cessation of esophageal variceal hemorrhage by endoscopic therapy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48:870–877. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, Wiesner RH, Kamath PS, Benson JT, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the livertransplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1018–1026. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0801209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao H, Zhao R, Hu J, Zhang X, Ma J, Shi Y, et al. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in acute-on-chronic liver failure: prevalence, characteristics, and impact on prognosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;13:263–269. doi: 10.1080/17474124.2019.1567329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Association for the Study of the Liver EASL clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with decompensated cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2018;69:406–460. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim TY, Song DS, Kim HY, Sinn DH, Yoon EL, Kim CW, et al. Characteristics and discrepancies in acute-on-chronic liver failure: need for a unified definition. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146745. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim TY, Kim DJ. Acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19:349–359. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2013.19.4.349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moreau R, Jalan R, Gines P, Pavesi M, Angeli P, Cordoba J, et al. Acute-on-chronic liver failure is a distinct syndrome that develops in patients with acute decompensation of cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1426–1437. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.042. 1437.e1-e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.D’Amico G, Pasta L, Morabito A, D’Amico M, Caltagirone M, Malizia G, et al. Competing risks and prognostic stages of cirrhosis: a 25-year inception cohort study of 494 patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:1180–1193. doi: 10.1111/apt.12721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suk KT, Baik SK, Yoon JH, Cheong JY, Paik YH, Lee CH, et al. Revision and update on clinical practice guideline for liver cirrhosis. Korean J Hepatol. 2012;18:1–21. doi: 10.3350/kjhep.2012.18.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sanyal AJ, Brunt EM, Kleiner DE, Kowdley KV, Chalasani N, Lavine JE, et al. Endpoints and clinical trial design for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;54:344–353. doi: 10.1002/hep.24376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bone RC, Balk RA, Cerra FB, Dellinger RP, Fein AM, Knaus WA, et al. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. The ACCP/SCCM Consensus Conference Committee. American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hernaez R, Kramer JR, Liu Y, Tansel A, Natarajan Y, Hussain KB, et al. Prevalence and short-term mortality of acute-on-chronic liver failure: a national cohort study from the USA. J Hepatol. 2019;70:639–647. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Amitrano L, Guardascione MA, Martino R, Manguso F, Menchise A, Balzano A. Hypoxic hepatitis occurring in cirrhosis after variceal bleeding: still a lethal disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;46:608–612. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318254e9d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Mahtab M, Akbar SMF, Garg H. Influence of variceal bleeding on natural history of ACLF and management options. Hepatol Int. 2016;10:436–439. doi: 10.1007/s12072-015-9677-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arasu S, Liaquat H, Suri J, Ehrlich AC, Friedenberg FK. Incidence and risk factors of dysphagia after variceal band ligation. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2019;25:374–380. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2019.0019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cárdenas A, Ginès P, Uriz J, Bessa X, Salmerón JM, Mas A, et al. Renal failure after upper gastrointestinal bleeding in cirrhosis: incidence, clinical course, predictive factors, and short-term prognosis. Hepatology. 2001;34(4 Pt 1):671–676. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.27830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng Y, Qi X, Guo X. Child–Pugh versus MELD score for the assessment of prognosis in liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2877. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000002877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blasco-Algora S, Masegosa-Ataz J, Gutiérrez-García ML, Alonso-López S, Fernández-Rodríguez CM. Acute-on-chronic liver failure: pathogenesis, prognostic factors and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:12125–12140. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i42.12125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wehler M, Kokoska J, Reulbach U, Hahn EG, Strauss R. Short-term prognosis in critically ill patients with cirrhosis assessed by prognostic scoring systems. Hepatology. 2001;34:255–261. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.26522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stauber RE, Stadlbauer V, Struber G, Kaufmann P. 165 evaluation of four prognostic scores in patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure. J Hepatol. 2006;44:S69–S70. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Augustin S, Altamirano J, González A, Dot J, Abu-Suboh M, Armengol JR, et al. Effectiveness of combined pharmacologic and ligation therapy in high-risk patients with acute esophageal variceal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:1787–1795. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suk KT. Hepatic venous pressure gradient: clinical use in chronic liver disease. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2014;20:6–14. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2014.20.1.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor NJ, Manakkat Vijay GK, Abeles RD, Auzinger G, Bernal W, et al. The severity of circulating neutrophil dysfunction in patients with cirrhosis is associated with 90-day and 1-year mortality. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:705–715. doi: 10.1111/apt.12886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wasmuth HE, Kunz D, Yagmur E, Timmer-Stranghöner A, Vidacek D, Siewert E, et al. Patients with acute on chronic liver failure display “sepsis-like” immune paralysis. J Hepatol. 2005;42:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.López-Sánchez GN, Dóminguez-Pérez M, Uribe M, Nuño-Lámbarri N. The fibrogenic process and the unleashing of acute-on-chronic liver failure. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26:7–15. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2019.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gustot T, Fernandez J, Garcia E, Morando F, Caraceni P, Alessandria C, et al. Clinical course of acute-on-chronic liver failure syndrome and effects on prognosis. Hepatology. 2015;62:243–252. doi: 10.1002/hep.27849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yokoyama K, Yamauchi R, Shibata K, Fukuda H, Kunimoto H, Takata K, et al. Endoscopic treatment or balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration is safe for patients with esophageal/gastric varices in Child-Pugh class C end-stage liver cirrhosis. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2019;25:183–189. doi: 10.3350/cmh.2018.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Cumulative overall survival rates of all patients. Cumulative OS rates at 28- and 90-days were 91.8% and 88.1%, respectively. OS, overall survival.

Areas under the receiver operating curves of the CLIF-SOFA score compared to CLIF-C OF and CLIF-C ALF for the 28- and 90-day mortalities in patients with variceal bleeding. AUROCs of CLIP-SOFA score for predicting the 28-day (A) and 90-day (B) mortality were higher than those of CLIF-C OF (0.860 [95% CI, 0.793–0.928] and 0.862 [95% CI, 0.784–0.939], respectively) and CLIF-C ALF (0.849 [95% CI, 0.787–0.910] and 0.871 [95% CI, 0.799–0.944], respectively). CLIF-SOFA, chronic liver failure-sequential organ failure assessment; CLIF-C, chronic liver failure consortium; OF, organ failure; ALF, acute liver failure; AUROC, areas under receiver operating curves; CI, confidence interval.

Cause of motality for 28- and 90-day in all patients with variceal bleeding (n=474)

CLIF-SOFA variables as risk factors for 28-day mortality in all patients with variceal bleeding (n=474)*