Abstract

Background/Aims

Patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) have a poor prognosis due to the lack of effective systemic therapies. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a pivotal event in tumor progression, during which cancer cells acquire invasive properties. In this study, we investigated the effects of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, including LY294002 and idelalisib, on the EMT features of HCC cells in vitro.

Methods

Human HCC cell lines, including Huh-BAT and HepG2, were used in this study. Cell proliferation was measured by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide, and cell cycle distributions were evaluated using a flow cytometer by propidium iodide staining. Immunofluorescence staining, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, and immunoblotting were performed to detect EMT-associated changes.

Results

PI3K inhibitors suppressed the proliferation and invasion of HCC cells and deregulated the expression of EMT markers, as indicated by increased expression of E-cadherin, an epithelial marker, and decreased expression of N-cadherin, a mesenchymal marker, and Snail, a transcription factor implicated in EMT regulation. Furthermore, LY294002 and idelalisib inhibited the phosphorylation of GSK-3β and induced the nuclear translocation of GSK-3β, which corresponded to the downregulation of Snail and β-catenin expressions in Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells.

Conclusions

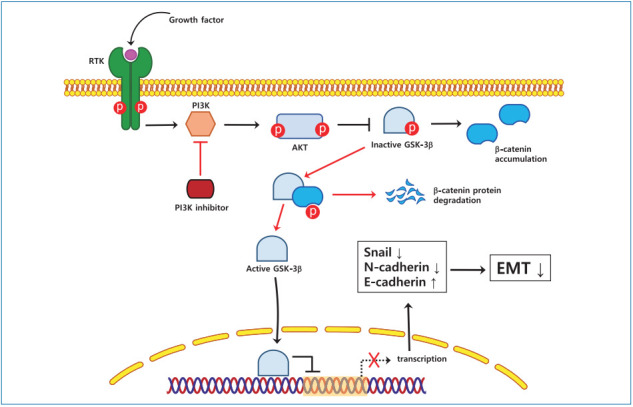

The inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling decreases Snail expression by enhancing the nuclear translocation of GSK-3β, which suppresses EMT in HCC cells, suggesting the potential clinical application of PI3K inhibitors for HCC treatment.

Keywords: Carcinoma, Hepatocellular; Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition; Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases; Glycogen synthase kinase-3; Snails

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third-leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide [1,2]. Although curative treatment options such as surgical resection and liver transplantation are feasible for patients with early-stage HCC, the overall survival remains rather low because of frequent tumor recurrence and metastasis after curative treatments [3]. Therefore, it is important to elucidate the mechanisms underlying HCC invasion and metastasis to establish new therapeutic targets to improve the prognosis of HCC.

The importance of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) in tumor metastasis has been recognized in many cancers, including HCC [4]. EMT is a key initiating step in cancer invasion and metastasis [5-7], during which epithelial cells lose intercellular adhesion ability and acquire mesenchymal characteristics, resulting in an increase in their migratory and invasive properties [8]. Among the mechanisms controlling the EMT process, transcriptional regulation by Snail plays an important role [9]. Snail, a zinc-finger transcription factor, shuttles between the cytoplasm and nucleus, where it binds to an E-box site in the promoter of the E-cadherinen-coding gene [10] and inhibits E-cadherin transcription, thereby triggering EMT [11-13]. Another factor involved in EMT regulation is glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK-3). Although the role of GSK-3 in cancer progression is ambiguous, it has been shown that this kinase could act as a tumor suppressor through phosphorylation of β-catenin and inhibition of the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, which results in preventing EMT, cancer development, and metastasis [14]. Furthermore, GSK-3 is known to participate in the ubiquitination and degradation of β-catenin and Snail [15].

The phosphorylation-dependent activation of GSK-3 is controlled through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt pathway, which is established to play a critical role in EMT, in particular by directly upregulating the expression of Snail [16]. When the PI3K/Akt pathway is activated through stimulation of receptor tyrosine kinases, the p85-p110 complex is recruited to the membrane, where it generates second messengers, which trigger a signaling cascade resulting in the activation of AKT, which phosphorylates GSK-3 [17]. The PI3K p110-encoding gene (PIK3CA) is aberrantly expressed in many cancers, such as breast, digestive tract, ovarian, and thyroid cancers and lymphomas, which have high metastatic capacity [18]. Therefore, PI3K inhibitors have been extensively investigated for their anticancer activity in multiple clinical trials. Among such inhibitors, idelalisib (also known as CAL-101), which specifically downregulates p110δ expression that is increased in metastatic tumors [19,20], has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and various lymphomas. However, there have been no studies about the therapeutic effect of idelalisib on HCC. LY294002, another PI3K inhibitor, acts by suppressing PI3K enzymatic activity, blocking cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis in HCC cells [21]. Because of their activity in cancer cells, idelalisib and LY294002 have attracted attention as potential agents for the treatment of metastatic tumors [22,23].

In this study, we examined whether PI3K inhibitors suppress EMT in HCC cells through deactivation of Snail.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture and drug treatment

Huh-BAT and HepG2 human HCC cells were obtained from the Korean Cell Line Bank (Seoul, Korea). HCC cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 mg/mL streptomycin. They were cultured in fresh medium for 24 hours at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 and then treated with different concentrations of LY294002 (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA, USA) or idelalisib (LC Laboratories, Woburn, MA, USA). Control cells were cultured in medium with 10% FBS without any additional treatments.

Cell proliferation assay

Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were plated in 96-well plates (5×103 cells/well), and 24 hours later, they were incubated with LY294002 or idelalisib for 2, 6, 24, or 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay following the manufacturer’s protocols. The cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/mL 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (Amresco Inc., Solon, OH, USA) at 37°C for 3 hours. Dimethyl sulfoxide (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to each well. The absorbance was detected at 540 nm using a plate reader. Each experiment was repeated three times.

Cell cycle analysis

Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were collected by trypsinization and then fixed in precooled 70% ethanol at 4°C for 20 minutes. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), they were incubated with 100 μg/mL RNase A (Amresco Inc.) at 37°C for 50 minutes. Each sample was stained with 1 mg/mL propidium iodide (Sigma-Aldrich). Cell cycle distributions were detected using a FACS Calibur flow cytometer and BD CellQuestTM Pro software version 5.2.1 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Invasion assay

The invasion assay was performed using 24-well Transwell plates (Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA). Briefly, Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were seeded in the upper chamber in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 24 hours at 37°C, after which 500 μL media containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chamber. Then, cells invading through the membrane were stained with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 minutes. Three random fields of the air-dried membrane were photographed under the microscope.

Immunofluorescence assay

Cells were grown on coverslips in 12-well culture plates and then exposed to 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 24 hours. Following fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature, the cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 15 minutes. After blocking with 10% normal goat serum (Vector Laboratories, Ltd., Peterborough, UK) for 1 hour at room temperature (23.8±6.3°C), cells were incubated with E-cadherin (1:50; cat. no. 3195; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., Danvers, MA, USA) and GSK-3β (1:50; cat. no. 610202; BD Biosciences) at 4°C overnight. Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody (1:50; cat. no. ab150113; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was applied for 1 hour at room temperature. The cell nuclei were stained with 4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, and the images were viewed under a confocal microscope.

Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA of HCC cells was extracted after treatment for 24 hours using the RNA extraction reagent TRIzol (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA). PCR primers were synthesized by Bioneer (Daejeon, Korea). The following primers were used: SNAI1 (Snail) forward 5’-GCGAGCTGCAGGACTCTAAT-3’ and reverse 5’-GGACAGAGTCCCAGATGAGCC-3’; CTNNB1 (β-catenin) forward 5’-GCTTGGTTCACCAGTGGATT-3’ and reverse 5’-GTTGAGCAAGGCAACCATTT–3’; and GAPDH forward 5’-CAGCCTCAAGATCATCAGCA-3’ and reverse 5’-TGGAAGGACTCATGACCACA-3’. Reverse transcription reagents (Enzynomics, Daejeon, Korea) were used for cDNA reverse transcription. PCR amplification was conducted using a 7500 Real Time PCR system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) using SYBR green-containing AccuPower 2X GreenStarq PCR Master Mix (Bioneer) with synthesized cDNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The following thermocycling conditions were used: 95°C for 10 minutes, followed by 40 PCR amplification cycles at 95, 60, and 95°C for 60 seconds at each temperature, and extension at 60°C for another 1 minute. Relative expression of the target genes was calculated after normalizing to GAPDH expression using the 2-ΔΔCTq method [24]. All reactions were performed in triplicate.

Nuclear protein extraction and immunoblotting

Cells were lysed in hypotonic buffer (10 mM HEPES, pH 7.9, 10 mM KCl, 100 μM EDTA, 1 mM DTT) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice for 5 minutes. Lysates were homogenized gently and centrifuged at 12,000 RPM for 30 seconds at 4°C; supernatants containing the cytosolic fraction were collected, whereas nuclear pellets were washed with ice-cold PBS and extracted with hypotonic buffer containing 400 mM NaCl and protease inhibitors. After centrifugation at 12,000 RPM, supernatants were collected and used as nuclear extracts. Protein concentration in whole cell lysates and nuclear extracts was determined using the bicinchoninic acid assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The protein samples (25 μg) were separated by 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Proteins were electrotransferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore) that were subsequently booked in 5% skim milk in tris-buffered saline with tween 20 buffer for 1 hour and then incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies against the following proteins: β-actin (1:2,000 dilution, cat. no. sc-47778; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA), HDAC1 (1:1,000 dilution, cat. no. sc-81598; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), α-tubulin (1:2,000 dilution, cat. no. sc-8035; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.), E-cadherin (1:1,000 dilution), N-cadherin (1:1,000 dilution, cat. no. 13116; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), β-catenin (1:2,000 dilution, cat. no. 610154, BD Biosciences), GSK-3β (1:2,000 dilution), Snail (1:1,000 dilution, cat. no. 3879; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), Akt (1:4,000 dilution, cat. no. 4691; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.), and phospho-Akt (1:2,000 dilution, cat. no. 4060; Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.). Then, either goat anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution, cat. no. sc-2357; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.) or goat anti-mouse HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (1:4,000 dilution, cat. no. 31430; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) was applied to the membranes. The blots were developed using enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents (Promega Corporation, Madison WI, USA). The densitometry of the protein bands was performed using Image J software version 1.51 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA). All western blotting experiments were performed in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using three independent experiments. Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS for Windows version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), and Student’s t-tests were carried out for statistical comparisons. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Inhibition of PI3K reduced HCC proliferation and induced cell cycle arrest

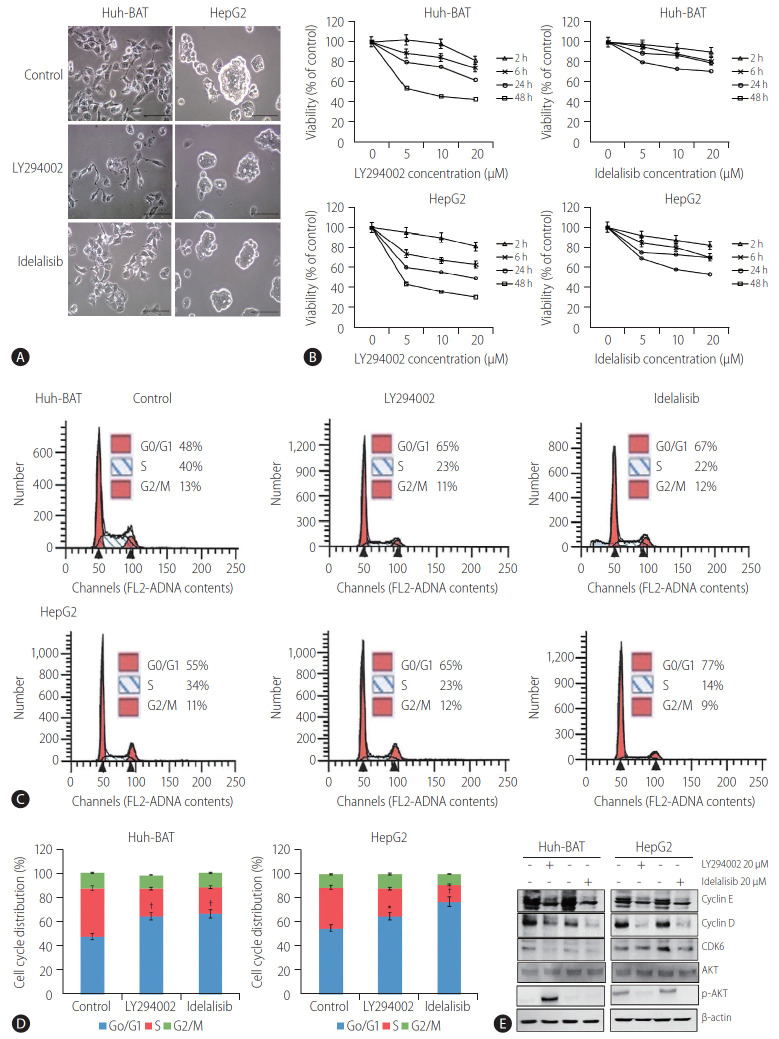

Microscopic analysis of LY294002- and idelalisib-treated cells revealed that the inhibitors markedly altered cell morphology and reduced the number and size of cell colonies (Fig. 1A). These observations were confirmed by the results of the cell viability assay conducted at different drug concentrations, which indicated that treatment with LY294002 or idelalisib decreased the viability of Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, cell cycle analysis revealed a significant increase in cells arrested at the G0/G1 phase after treatment with LY294002 or idelalisib (Fig. 1C, D; *P<0.05 and †P<0.01, respectively). To address the mechanisms underlying cell cycle arrest induced by PI3K inhibitors, we examined the expression of cyclin D, cyclin E, and CDK6 and found that they were decreased in LY294002- and idelalisib-treated cells compared to untreated control cells. Akt signaling was blocked only in the HepG2 cell line (Fig. 1E). Collectively, these findings suggest that LY294002 and idelalisib induced Huh-BAT and HepG2 cell death through G0/G1 phase arrest.

Figure 1.

LY294002 and idelalisib reduce cellular proliferation and induce cell cycle arrest at the G0/G1 phase. (A) Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 48 hours. Cell morphology was observed by phase-contrast microscopy. Scale bar, 100 μm. (B) Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were treated with different concentrations of LY294002 or idelalisib (5, 10, and 20 μM) for 2, 6, 24, and 48 hours. Cell viability was measured using the MTT assay. Flow cytometry analysis were monitored to measure cell cycle distributions (C, D). Cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 48 hours. The percentage of cell cycle progression was evaluated from three independent experiments. (E) The protein expression of cyclin D, cyclin E and CDK6, total Akt, and phosphor-Akt was detected by immunoblotting, and quantifications are shown. Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation. *P<0.05 and †P<0.01 compared with untreated control cells.

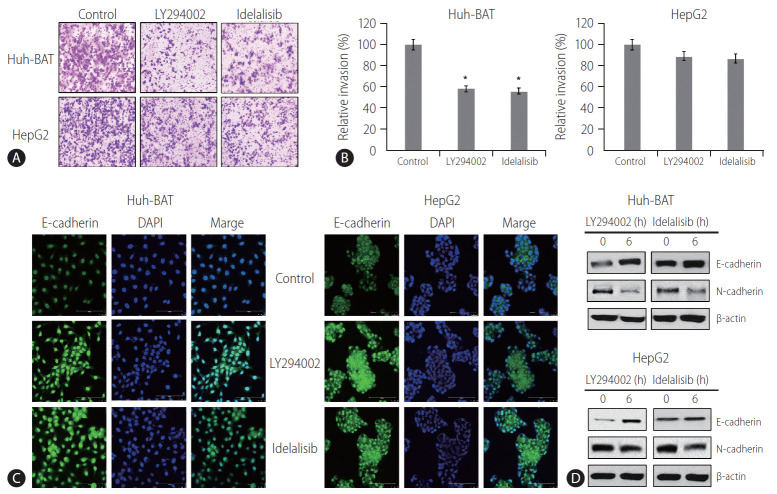

PI3K inhibitors suppressed EMT

The invasion ability of HCC cells treated with PI3K inhibitors was measured by the Transwell invasion assay. The results demonstrated that exposure to LY294002 or idelalisib decreased cell invasion compared to that in the control (Fig. 2A, B). At the same time, immunocytochemistry analysis showed upregulation of E-cadherin expressions (Fig. 2C) in PI3K inhibitor-treated cells. Immunoblotting experiments confirmed these results and revealed a decrease in the expressions of N-cadherin (Fig. 2D). These findings suggest that LY294002 and idelalisib decreased HCC cell invasion by inhibiting EMT through maintaining cellular epithelial characteristics.

Figure 2.

LY294002 and idelalisib suppress the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. (A, B) Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib, for 48 hours, and invasion capability was measured with an invasion assay. The resulting colonies were stained and quantified. All data are expressed as the mean±standard deviation. *P<0.05. (C) Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib, for 48 hours. E-cadherin expression was measured by confocal fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×400). (D) Changes in the protein levels of E-cadherin and N-cadherin were analyzed by immunoblotting following 48 hours of treatment with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib. DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

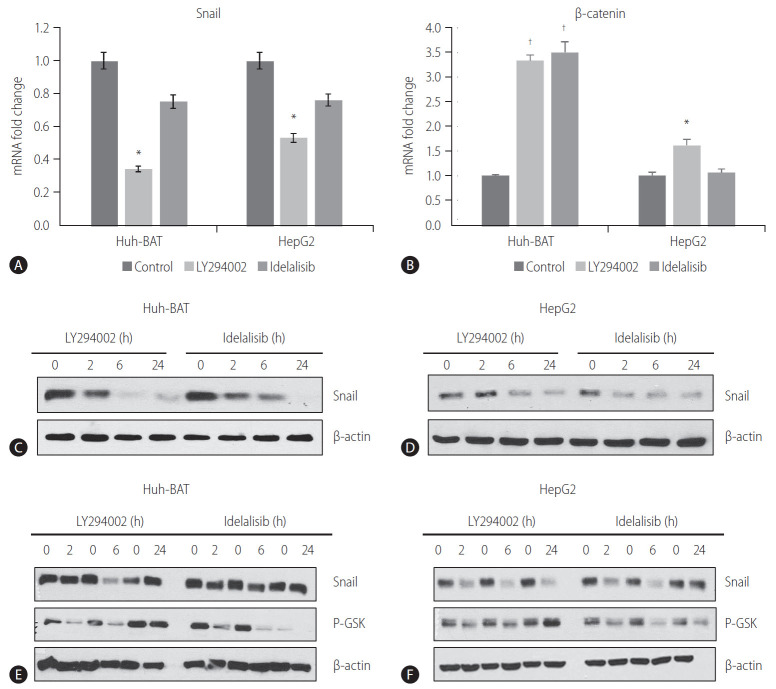

PI3K inhibitors downregulated Snail expression

To investigate whether the PI3K/Akt pathway was involved in the regulation of EMT and Snail expression in HCC cells, we examined the protein and mRNA levels of Snail and β-catenin in Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells treated with PI3K inhibitors. The PI3K inhibitors decreased the transcription of Snail (Fig. 3A) but increased the transcription of β-catenin (Fig. 3B). Consistent with these results, Snail protein expression was significantly decreased in LY294002- and idelalisib-treated cells in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 3C, D).

Figure 3.

LY294002 and idelalisib suppress Snail and β-catenin expressions. (A, B) The mRNA levels of Snail and β-catenin were quantified by qRT-PCR following treatment with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib in Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells. (C, D) Huh-BAT cells and HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib, for various time points. The protein expression levels of Snail were evaluated by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. (E, F) Huh-BAT cells and HepG2 cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib, for various time points. The protein expression levels of Snail and phospho-GSK-3β were evaluated by immunoblotting. β-actin was used as a loading control. Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation. *P<0.05 and †P<0.01 compared with untreated control cells. P-GSK, phospho-glycogen synthase kinase; qRT-PCR, quantitative Real-time polymerase chain reaction.

GSK-3β is a downstream target of Akt kinase that is responsible for Snail protein stability [25]. To determine whether the decrease in Snail expression was mediated by GSK-3β, we assessed GSK-3β protein levels in whole lysates of HCC cells treated with PI3K inhibitors for different time points. Immunoblotting analysis revealed a decrease in the phosphorylation of GSK-3β (Fig. 3E, F). These results imply that inhibition of the PI3K pathway results in the downregulation of Snail expression via dephosphorylation of GSK-3β in HCC cells.

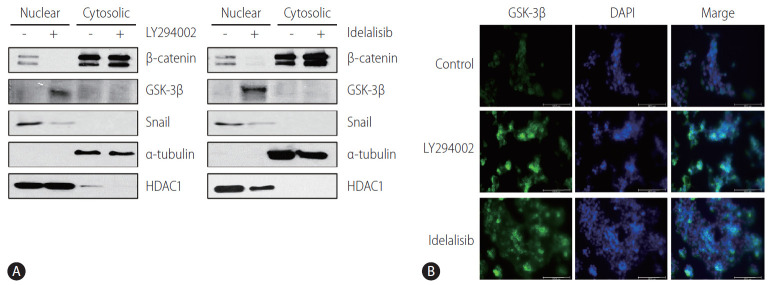

PI3K inhibitors prevent EMT by downregulating Snail expression via the nuclear translocation of GSK-3β

Immunoblotting analysis of nuclear extracts revealed that the nuclear expression of GSK-3β was increased, whereas that of Snail and β-catenin was decreased in LY294002- and idelalisib-treated Huh-BAT and HepG2 cells (Fig. 4A). Immunocytochemistry staining also showed that GSK-3β was mostly translocated to the nucleus after treatment with LY294002 and idelalisib (Fig. 4B). These results indicated that PI3K inhibition prevented EMT by reducing the expression of Snail via the nuclear translocation of GSK-3β.

Figure 4.

LY294002 and idelalisib regulate cellular translocalization of proteins. (A) Huh-BAT cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 48 hours. Protein expression levels of β-catenin, GSK-3β and Snail were evaluated by immunoblotting in both nuclear and cytosolic compartments. α-tubulin and HDAC1 were used as nuclear and cytosolic loading controls, respectively. (B) Huh-BAT cells were treated with 20 μM LY294002 or idelalisib for 48 hours. Following treatments, localization of GSK-3β was evaluated using immunofluorescence. GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β; DAPI, 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

DISCUSSION

EMT is an essential physiological process during cancer metastasis and invasion. Although EMT-related signal transduction pathways and transcription factors involved in tumor cell invasion and metastasis have been studied as targets in HCC prevention and treatment [26], the underlying mechanisms are not fully understood. In this study, we showed that the inhibition of the PI3K pathway by LY294002 and idelalisib downregulates Snail and β-catenin expression by increasing GSK-3β nuclear translocation, ultimately suppressing EMT and HCC cell proliferation.

Aberrant activation of the PI3K/Akt pathway is often observed during the EMT process and correlates with the progression of different types of human cancer, including HCC [27,28]. Therefore, PI3K/Akt inhibitors have been examined as a chemotherapeutic approach against malignant tumors [29]. In this study, we showed that the inhibition of the PI3K pathway by LY294002 and idelalisib suppressed HCC cell proliferation and invasion, and reversed the activation of EMT markers, probably through downregulation of Snail expression at both the mRNA and protein levels. These results are consistent with those of a previous study showing that a PI3K inhibitor reduced Snail expression at the transcriptional and translational levels and promoted the acquisition of the epithelial phenotype in oral cancer cells [26].

To investigate the molecular mechanism underlying PI3K/Akt-mediated Snail inhibition, we analyzed the expression level of GSK-3β, a downstream effector of Akt, in whole cell lysates, as well as in the nuclear and cytosolic compartments. GSK-3β plays an important role in suppressing tumor development by phosphorylating β-catenin and Snail, which promotes their ubiquitination and subsequent degradation and is regulated through PI3K/Akt signaling. Our results indicate that the levels of GSK-3β in the nuclei were markedly increased by PI3K inhibitors in HCC cells, suggesting that nuclear translocation of GSK-3β may be the cause of the reduction in Snail expression and inhibition of the EMT process [30,31]. These findings are consistent with a previous study showing that GSK-3β localized to the nucleus decreased Snail protein expression, whereas a GSK-3β mutant localized to the cytosol increased Snail nuclear levels and are in line with the notion that subcellular localization of GSK-3β is a key element in the pathway regulating Snail and β-catenin activity [32].

Molecular interactions defining nuclear or cytosolic GSK-3β localization have not been fully clarified, and further studies are needed to investigate the detailed mechanism underlying GSK-3β nuclear translocation and its association with Snail, which is suggested by the results of this and other studies. Although decreased phosphorylation of GSK-3β can lead to Snail downregulation and promote β-catenin protein degradation, PI3K inhibitors decreased the transcription of Snail and increased the transcription of β-catenin in this study. This contradictory phenomenon could be explained by the fact that many factors might be associated with the nuclear localization of β-catenin [33]. Among them, MUC-1 promotes nuclear translocation and blocks GSK-3β-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of β-catenin [34]. Thus, disruption of the MUC-1 binding site or nuclear localization signals (NLSs) on β-catenin or stimulation of nuclear export pathway proteins, such as APC/AXIN, can prevent nuclear localization of β-catenin. These dephosphorylated (active state) GSK-3β can translocate into the nucleus via mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1) and NLS and downregulate Snail and β-catenin expression. However, degradation of β-catenin can be blocked by MUC-1, since it can inhibit phosphorylation of β-catenin by GSK-3β. mTORC1 has been reported as a regulator of GSK-3β nuclear localization [35,36]. Inhibition of the mechanistic target of mTORC1 leads to a partial redistribution of GSK-3β from the cytosol to the nucleus and a GSK-3β-dependent reduction in the expression of c-Myc and Snail. Snail is a substrate of GSK-3β. Thus, it can be controlled by mutations in the localization sequence of GSK-3β or suppression of mTORC1. A recent report indicates that Axin2, a GSK-3β scaffolding protein, is involved in shuttling GSK-3β from the nucleus, which results in the activation of the Wnt signaling cascade, whereas Axin2 silencing promotes the nuclear localization of GSK-3β [37]. It would be interesting to examine whether manipulation of Axin2 expression would confirm the inverse correlation between nuclear GSK-3β levels and Snail protein stability.

In conclusion, the current study demonstrates that PI3K inhibitors, including LY294002 and idelalisib, suppress the proliferation and invasion of HCC cells in vitro by promoting the nuclear translocation of GSK-3β, which results in the downregulation of Snail and β-catenin expression. These results suggest that PI3K/Akt pathway might be a promising target for HCC treatment.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Liver Research Institute of Seoul National University College of Medicine for providing relevant experimental facilities and technical support.

This study was supported by grants from the Yuhan Corporation (no. 800-20170050) and grants from the SNUH Research Fund (No. 0320190100)

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- GSK-3

glycogen synthase kinase-3

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- HRP

horseradish peroxidase

- mTORC1

mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1

- MTT

3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide

- NLSs

nuclear localization signals

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PIK3CA

PI3K p110-encoding gene

- RT-PCR

real-time polymerase chain reaction

Study Highlights

PI3K inhibitors suppressed the proliferation and invasion of HCC cells, increased the expression of E-cadherin, and decreased the expression of N-cadherin and Snail. The inhibition of PI3K/Akt signaling decreased Snail expression by enhancing the nuclear accumulation of GSK-3β, which suppresses EMT in HCC cells.

Footnotes

Authors’ contribution

S Lee and EJ Choi designed and performed the experiments, analyzed the data and prepared the manuscript. EJ Cho, YB Lee, JH Lee, SJ Yu and JH Yoon contributed to the writing of the manuscript. YJ Kim designed and was the overseer of the entire study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel R, Naishadham D, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2013. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:11–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas MB, Zhu AX. Hepatocellular carcinoma: the need for progress. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2892–2899. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferenci P, Fried M, Labrecque D, Bruix J, Sherman M, Omata M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): a global perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2010;44:239–245. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181d46ef2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.van Zijl F, Mall S, Machat G, Pirker C, Zeillinger R, Weinhaeusel A, et al. A human model of epithelial to mesenchymal transition to monitor drug efficacy in hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10:850–860. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-10-0917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kalluri R, Weinberg RA. The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1420–1428. doi: 10.1172/JCI39104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu Y, Zhou BP. Snail: more than EMT. Cell Adh Migr. 2010;4:199–203. doi: 10.4161/cam.4.2.10943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peinado H, Olmeda D, Cano A. Snail, Zeb and bHLH factors in tumour progression: an alliance against the epithelial phenotype? Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:415–428. doi: 10.1038/nrc2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nieto MA. The snail superfamily of zinc-finger transcription factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:155–166. doi: 10.1038/nrm757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prokop JW, Liu Y, Milsted A, Peng H, Rauscher FJ., 3rd A method for in silico identification of SNAIL/SLUG DNA binding potentials to the E-box sequence using molecular dynamics and evolutionary conserved amino acids. J Mol Model. 2013;19:3463–3469. doi: 10.1007/s00894-013-1876-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Batlle E, Sancho E, Francí C, Domínguez D, Monfar M, Baulida J, et al. The transcription factor snail is a repressor of E-cadherin gene expression in epithelial tumour cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:84–89. doi: 10.1038/35000034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano A, Pérez-Moreno MA, Rodrigo I, Locascio A, Blanco MJ, del Barrio MG, et al. The transcription factor snail controls epithelial-mesenchymal transitions by repressing E-cadherin expression. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:76–83. doi: 10.1038/35000025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dong C, Wu Y, Yao J, Wang Y, Yu Y, Rychahou PG, et al. G9a interacts with Snail and is critical for Snail-mediated E-cadherin repression in human breast cancer. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:1469–1486. doi: 10.1172/JCI57349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McCubrey JA, Fitzgerald TL, Yang LV, Lertpiriyapong K, Steelman LS, Abrams SL, et al. Roles of GSK-3 and microRNAs on epithelial mesenchymal transition and cancer stem cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:14221–14250. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.13991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahn SY, Kim NH, Lee K, Cha YH, Yang JH, Cha SY, et al. Niclosamide is a potential therapeutic for familial adenomatosis polyposis by disrupting Axin-GSK3 interaction. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31842–31855. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burger JA, Okkenhaug K. Haematological cancer: idelalisib-targeting PI3Kδ in patients with B-cell malignancies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2014;11:184–186. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2014.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henderson V, Smith B, Burton LJ, Randle D, Morris M, Odero-Marah VA. Snail promotes cell migration through PI3K/AKT-dependent Rac1 activation as well as PI3K/AKT-independent pathways during prostate cancer progression. Cell Adh Migr. 2015;9:255–264. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1013383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zawel L. P3Kα: a driver of tumor metastasis? Oncotarget. 2010;1:315–316. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Castillo JJ, Furman M, Winer ES. CAL-101: a phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase p110-delta inhibitor for the treatment of lymphoid malignancies. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2012;21:15–22. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2012.640318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor JR, Lehmann BD, Chappell WH, Abrams SL, Steelman LS, McCubrey JA. Cooperative effects of Akt-1 and Raf-1 on the induction of cellular senescence in doxorubicin or tamoxifen treated breast cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2011;2:610–626. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kunter I, Erdal E, Nart D, Yilmaz F, Karademir S, Sagol O, et al. Active form of AKT controls cell proliferation and response to apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2014;31:573–580. doi: 10.3892/or.2013.2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36803–36810. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005912200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xu Q, Ma J, Lei J, Duan W, Sheng L, Chen X, et al. α-Mangostin suppresses the viability and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer cells by downregulating the PI3K/Akt pathwa. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:546353. doi: 10.1155/2014/546353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhou BP, Deng J, Xia W, Xu J, Li YM, Gunduz M, et al. Dual regulation of Snail by GSK-3beta-mediated phosphorylation in control of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:931–940. doi: 10.1038/ncb1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xu W, Yang Z, Lu N. A new role for the PI3K/Akt signaling pathway in the epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cell Adh Migr. 2015;9:317–324. doi: 10.1080/19336918.2015.1016686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Grille SJ, Bellacosa A, Upson J, Klein-Szanto AJ, van Roy F, Lee-Kwon W, et al. The protein kinase Akt induces epithelial mesenchymal transition and promotes enhanced motility and invasiveness of squamous cell carcinoma lines. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2172–2178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larue L, Bellacosa A. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition in development and cancer: role of phosphatidylinositol 3’ kinase/AKT pathways. Oncogene. 2005;24:7443–7454. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Han Z, Hong L, Han Y, Wu K, Han S, Shen H, et al. Phospho Akt mediates multidrug resistance of gastric cancer cells through regulation of P-gp, Bcl-2 and Bax. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2007;26:261–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. beta-catenin is a target for the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Osakada F, Takahashi M. Drug development targeting the glycogen synthase kinase-3beta (GSK-3beta)-mediated signal transduction pathway: targeting the Wnt pathway and transplantation therapy as strategies for retinal repair. J Pharmacol Sci. 2009;109:168–173. doi: 10.1254/jphs.08r19fm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wiechens N, Heinle K, Englmeier L, Schohl A, Fagotto F. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Axin, a negative regulator of the Wnt-beta-catenin Pathway. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5263–5267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307253200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morgan RG, Ridsdale J, Tonks A, Darley RL. Factors affecting the nuclear localization of β-catenin in normal and malignant tissue. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115:1351–1361. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang L, Chen D, Liu D, Yin L, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. MUC1 oncoprotein blocks glycogen synthase kinase 3beta-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of beta-catenin. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10413–10422. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bautista SJ, Boras I, Vissa A, Mecica N, Yip CM, Kim PK, et al. mTOR complex 1 controls the nuclear localization and function of glycogen synthase kinase 3β. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:14723–14739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He L, Fei DL, Nagiec MJ, Mutvei AP, Lamprakis A, Kim BY, et al. Regulation of GSK3 cellular location by FRAT modulates mTORC1-dependent cell growth and sensitivity to rapamycin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116:19523–19529. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902397116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cong F, Varmus H. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of Axin regulates subcellular localization of beta-catenin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:2882–2887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307344101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]