Abstract

Background

Despite being one of the few evidence-based treatments for acute ischemic stroke, intravenous thrombolysis has low implementation rates—mainly due to a narrow therapeutic window and the health system changes required to deliver it within the recommended time. This systematic review and meta-analyses explores the differential effectiveness of intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of intravenous thrombolysis based on the number and type of behaviour change wheel functions employed.

Method

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and SCOPUS. Multiple authors independently completed study selection and extraction of data. The review included studies that investigated the effects of intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of intravenous thrombolysis and/or onset-to-needle, onset-to-door and door-to-needle time for thrombolysis in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Interventions were coded according to the behaviour change wheel nomenclature. Study quality was assessed using the QualSyst scoring system for quantitative research methodologies. Random effects meta-analyses were used to examine effectiveness of interventions based on the behaviour change wheel model in improving rates of thrombolysis, while meta-regression was used to examine the association between the number of behaviour change wheel intervention strategies and intervention effectiveness.

Results

Results from 77 studies were included. Five behaviour change wheel interventions, ‘Education’, ‘Persuasion’, ‘Training’, ‘Environmental restructuring’ and ‘Enablement’, were found to be employed among the included studies. Effects were similar across all intervention approaches regardless of type or number of behaviour change wheel-based strategies employed. High heterogeneity (I2 > 75%) was observed for all the pooled analyses. Publication bias was also identified.

Conclusion

There was no evidence for preferring one type of behaviour change intervention strategy, nor for including multiple strategies in improving thrombolysis rates. However, the study results should be interpreted with caution, as they display high heterogeneity and publication bias.

Keywords: Thrombolysis, Implementation, Intervention, Systematic review, Meta-analysis

Contribution to the literature.

This study is the first rigorous systematic review and meta-analysis, which evaluates the differential effect of intervention strategies aimed at improving rates of intravenous thrombolysis based on behaviour change wheel intervention function as an analytical framework.

This review illustrates that this field of research not only has high heterogeneity as previously known, but also provides new evidence of publication bias both within and across intervention types.

Although this study indicates that various strategies can be effective, it does not provide strong evidence supporting any specific strategy. Most studies do not have enough detail to unambiguously classify the intervention components.

Background

Stroke causes 5.5 million deaths worldwide and requires substantial treatment and post-stroke care-related economic costs [1]. There are an estimated 80 million stroke survivors worldwide, with an increase in absolute numbers of disability-adjusted life years [1]. Acute ischemic stroke (AIS) refers to the most prevalent and disabling form of stroke [2]. Intravenous thrombolysis (IVT) is considered one of the mainstream therapies for AIS since its approval in 1996 by the United States Food and Drug Administration as a first-line treatment [3]. Despite substantial evidence for both the safety and cost-effectiveness of IVT, the implementation rate has remained persistently low [4]. Subsequently, over 50 published studies deploying a variety of trial designs have tested a variety of approaches to boost implementation rates. One major challenge for increasing IVT usage is reducing onset-to-needle time, the sum of the onset-to-door and the door-to-needle times. Several strategies to reduce door-to-needle time have already been tested and have achieved improvements in IVT rates. Delayed patient arrival at hospital remains, however, one of the major obstacles to better IVT implementation with many studies focusing on approaches aiming to reduce pre-hospital delay [5]. Several additional factors, relevant at both individual and organisational levels, have been identified as major rate-limiting factors for IVT implementation [6]. Patients’ and bystanders’ inability to recognise stroke symptoms and signs resulting in delayed response in seeking support from healthcare providers contributes to delayed hospital arrival [6]. Delays in stroke recognition by paramedics and hospital staff, delays in obtaining and interpreting brain imaging, inefficiencies in emergency stroke care, delays in obtaining treatment consent, an absence of decision support systems and protocols in emergency care facilities and physician perception of IVT efficacy and safety have also been identified as major factors that limit IVT implementation [5]. Consequently, several, often multi-faceted intervention strategies have been tested in efforts to improve the rates of IVT in AIS [7]. Such intervention strategies include telemedicine and ‘hub-spoke’ models, pre- and/or in-hospital notification, multi-disciplinary collaborative approaches and re-organisation of pre-hospital and hospital systems of care [4, 7].

Since the intervention strategies to date have used a variety of methods in various settings, we aim to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to compare the effectiveness of the various forms of intervention strategies. Thus far, there are three published systematic reviews that have attempted to investigate these issues; however, each has limitations. The first systematic review, published in 2016, only included studies that met the Cochrane collaboration standards for practice and organisation of care study design criteria [8]. The second and third systematic reviews and meta-analyses were published in 2018 and 2019 [4, 7]. Both studies expressed the meta-analyses results based on various intervention approaches, but they did not use any specific operational definitions or theoretical approaches when grouping the studies in the analyses [4, 7]. Moreover, neither study explored publication bias when describing group-based results [4, 7], despite the importance of this information to data interpretation.

Theory-based analysis of interventions is recommended when investigating the effect of a specific intervention strategy and aiding in the specification of a potentially active process of care [9]. For example, behaviour-targeted theories can be utilised to define the components of implementation interventions [10]. Multi-level, multi-disciplinary testing and decision-making processes are needed to identify a patient’s eligibility for IVT [11]. Therefore, increasing rates of IVT in AIS are considered an example where multiple factors could be critical to the design of targeted intervention strategies [8]. Conceptual frameworks, such as the behaviour change wheel (BCW), can be useful in defining the range of factors (e.g. training) that need to be addressed to effect complex change [12]. BCW is a behavioural framework which has at its centre the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation-Behaviour (COM-B) theory. As described by Nilsen et al. 2015 [13], the COM-B is an implementation theory which is useful for providing an understanding or an explanation of aspects of implementation. The overarching BCW framework specifies intervention functions (e.g. education, persuasion, training), which can be used to develop intervention content (i.e. a process model) and guide evaluation of an implementation intervention (e.g. an evaluation framework) [13]. Therefore, the BCW framework provides a useful structure for categorising and understanding the content of previous interventions and considering their potential implications; particularly in the context of literature where in-depth detail about intervention content is not commonly provided. In the context of stroke care, considering the existing literature in terms of intervention functions rather than solely pooling all implementation studies has the potential to provide additional understanding regarding how to successfully implement a complex multi-component practice like IVT in a given healthcare organisation. Thus, an evaluation of the interventions aimed at improving the rates of IVT in AIS including coding them based on BCW intervention function could assist to identify more clearly the approaches which might be associated with higher rates of IVT implementation.

The core aspect of the BCW framework described by Michie et al. consists of a ‘behaviour system’ that includes three key elements: capability, opportunity and motivation. This core aspect is surrounded by nine intervention functions and then by seven policy categories [12]. The intervention functions help to identify the gaps and highlight the areas that need intervention. For example, the intervention functions were used to characterise interventions related to smoking cessation and reducing obesity [12]. The functions can also be used to contextualise already implemented interventions and to lead to more efficient design of effective interventions. To date, no studies have used the BCW classification as a framework for examining the intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of IVT. To synthesise the results of studies which tested the effect of intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of IVT in AIS, we will use the BCW nomenclature as the analytical context with the following primary and secondary objectives:

❖ Primary objective: to explore the differential effectiveness of the intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of IVT based on the number and type of BCW intervention functions employed.

❖ Secondary objective: to describe the number and type of BCW intervention functions employed in intervention strategies aimed at improving the rates of IVT.

Methods

This systematic review follows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines [14]. The PRISMA statement is provided in Supplementary file 1. This systematic review was not registered.

Searches

MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, CINAHL and SCOPUS databases were searched for articles published from January 1996 to December 2018 in English. We also checked the reference lists of included articles and existing systematic reviews for relevant studies. The search dates were selected to coincide with the 1996 approval and release of the first thrombolysis guideline for AIS [15].

We followed the search strategy described by Paul et al. 2016 [8] while selecting the search terms. The search terms are a combination of keyword searches: ‘Tissue plasminogen activator’ OR ‘tPA’ OR ‘rtPA’ OR ‘Alteplase’ OR ‘Thrombolysis’ AND ‘Stroke’ OR ‘Ischemic stroke’ OR ‘Brain ischemia’ OR ‘Middle cerebral artery infarction’ OR ‘Cerebrovascular disorder’ OR ‘Cerebrovascular accident’ OR ‘CVA’ OR ‘Cerebral stroke’ OR ‘Cerebral accident’ OR ‘Cerebral infarction’ OR ‘Cerebral apoplexy’ OR ‘Cerebrovascular apoplexy’. We used available MeSH headings; otherwise, a ‘multi-purpose; mp.’ field search was conducted. One senior librarian reviewed the final search strategy. The detailed search strategy is provided in Supplementary file 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This systematic review included the following: quantitative studies that investigated the effect of interventions to improve the rates of IVT and/or onset-to-needle, onset-to-door and door-to-needle time for IVT in patients with AIS; studies that reported the rates of IVT utilisation and/or onset-to-door and/or door-to-needle time for thrombolysis as their primary outcome; studies that reported the number of patients with AIS who received IVT and the total number of suspected stroke and/or confirmed stroke and/or confirmed ischemic stroke patients and/or the total number of eligible patients for IVT; randomised controlled trials and cluster-randomised trials; non-randomised studies, such as uncontrolled before-after studies; parallel group trials; and observational studies including cohort, case-control and cross-sectional studies. The systematic review included a wide range of study designs to identify the possible reasons and factors behind the systematic review result [16]. Inclusion was also limited to original human research studies.

The review excluded studies that reported only haemorrhagic stroke or transient ischemic attack and those reporting rates of thrombolysis other than IVT. Key exclusion and inclusion points are summarised in Supplementary file 3.

Outcome measures

We used IVT rates as our outcome of interest. The numerator was the total number of patients who received IVT, and the denominator was the total number of suspected stroke, confirmed stroke, confirmed ischemic stroke or IVT-eligible patients.

Potential effect modifiers and reasons for heterogeneity

Outcome measures were grouped as follows, to explain some of the heterogeneity across the studies:

❖ Hospital factors addressed by the intervention (pre-hospital, in-hospital or both pre- and in-hospital)

❖ Denominator used (suspected stroke, confirmed stroke, confirmed ischemic stroke or IVT-eligible patients).

❖ Epidemiological design of the study (uncontrolled before-and-after, parallel group trial or randomised controlled trial).

The number of BCW intervention functions employed was included as a covariate in a meta-regression to examine the association between number of BCW intervention functions employed and intervention effectiveness and to explain the heterogeneity between the studies.

Study quality assessment

Three reviewers assessed the quality of the studies. The principal reviewer (MGH) independently assessed the methodological quality of the final articles using the QualSyst scoring system for quantitative research methodologies [17]. The total number of included studies was then divided between two independent reviewers (SA and TR), who also assessed the quality of the studies using the same scoring system. Joint discussion between all three reviewers resolved any disagreements. Studies were scored depending on whether they fully met the criteria (2 points), partially met the criteria (1 point) or did not meet the criteria at all (0 points). Quantitative studies were scored against 14 criteria. A criterion for ‘evidence of ethical approach’ was added to the QualSyst scoring, resulting in a maximum total possible score of 22 for qualitative designs and 30 for quantitative designs [18].

Study selection

All reviewers reviewed the titles and abstracts of the last 500 search results to identify abstracts that would potentially meet the inclusion criteria. There was > 95% agreement between reviewers. After removing duplicates, the principal reviewer reviewed all titles and abstracts and the full text of each non-rejected article to arrive at final inclusion determinations. The other two reviewers concurrently and independently reviewed half of the titles and abstracts and the full texts of non-rejected articles each and then compared their determinations to those made by the principal reviewer. The study selection process is described in more detail in Supplementary file 4 and Supplementary file 5

Data extraction and coding strategy

The principal reviewer performed data extraction for all articles independently identified as ‘included’. A data extraction form was developed following the format used in the Cochrane Handbook for Systemic Reviews of Interventions [19]. This process recorded the following information: country, setting, publication year, intervention duration, study type based on epidemiological design, description of the intervention and outcome. The outcome used the total number of patients receiving IVT as the numerator and the total number of suspected stroke, confirmed stroke, confirmed ischemic stroke or IVT-eligible patients as the denominator. To ensure consistency, a data extraction form was pilot-tested on a 5% subset of the included full-text studies.

The interventions in the included studies were coded according to BCW framework intervention functions criteria mentioned in Michie et al [10].. Operational definitions for the included intervention functions have been described in Table 1. Three reviewers were involved in the process of coding. The principal author (MGH) independently identified the BCW intervention functions addressed through the interventions of the 77 studies. The total number of included studies was then divided between another two co-authors (SA and TR), who also identified the BCW intervention functions addressed through the interventions of the 38 and 39 studies respectively. The discrepancy between MGH and SA was 10.5% (4 out of 38) and between MGH and TR was 7.7% (3 out of 39). Joint discussion between all three reviewers resolved any disagreements. All coding discrepancies were then reviewed and finalised by the senior author (CP).

Table 1.

Operational definitions for the assessed intervention components

| Intervention component | Definition |

|---|---|

| Education | Providing systematic education or instruction to increase knowledge or understanding on stroke via face-to-face or online educational session, or by providing print or online educational materials to the health professionals from any level or community members. |

| Persuasion | Improve communication to stimulate the treatment process in patients with stroke. |

| Training |

Providing systematic training to the community members or health professionals from any level to improve their skills in identifying suspected stroke cases. AND OR Providing systematic training to the health professionals from any level to improve their skills in diagnosing and treating stroke cases. |

| Environmental Restructuring | Restructuring, reorganising or rearranging individual, social or organisational context to promote the usage of thrombolysis in stroke. |

| Enablement | Increasing resources such or reducing obstacles to increase capability or opportunity at the individual level, e.g. health care staff or organisational level, e.g. hospital to promote the process and quality of stroke care. |

Studies were categorised based on the number and type of BCW interventions employed. Specifically, studies were categorised based on:

❖ The number of BCW components implemented as part of the intervention, with categories including 1, 2, 3 or > 3.

❖ Whether one of the following components were included as part of the intervention: education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction, environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement.

Statistical analyses

Separate random effects meta-analyses by type of BCW strategy (i.e. education, persuasion, training, environmental, restructuring and enablement) and by number of BCW strategies implemented (i.e. one, two, three and more than 3) were conducted to assess the effectiveness of the interventions on improving IVT rates (primary objective). For each meta-analysis, a pooled odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated using the metan command in Stata. In addition, forest plots were used to show the effect sizes, to assess possible heterogeneity and identify potential outliers. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed by chi-square and I2 statistics. Publication bias was assessed by testing the asymmetry of funnel and contour-enhanced funnel plots, which were created using the metafunnel and confunnel commands in Stata, and via Egger’s test, which was conducted using the metabias command which was used in Stata. The impact of potential outliers on the results was assessed by conducting sensitivity analyses whereby any identified outliers were removed and the analysis re-run. Descriptive analyses were used to report the number and type of BCW framework interventions used as part of the study intervention (secondary objective). Finally, to determine if the number of BCW intervention strategies used were associated with intervention effectiveness, meta-regression was conducted using the metareg command in Stata. Stata (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas, USA) version 14 was used to conduct all analyses.

Results

Description of studies

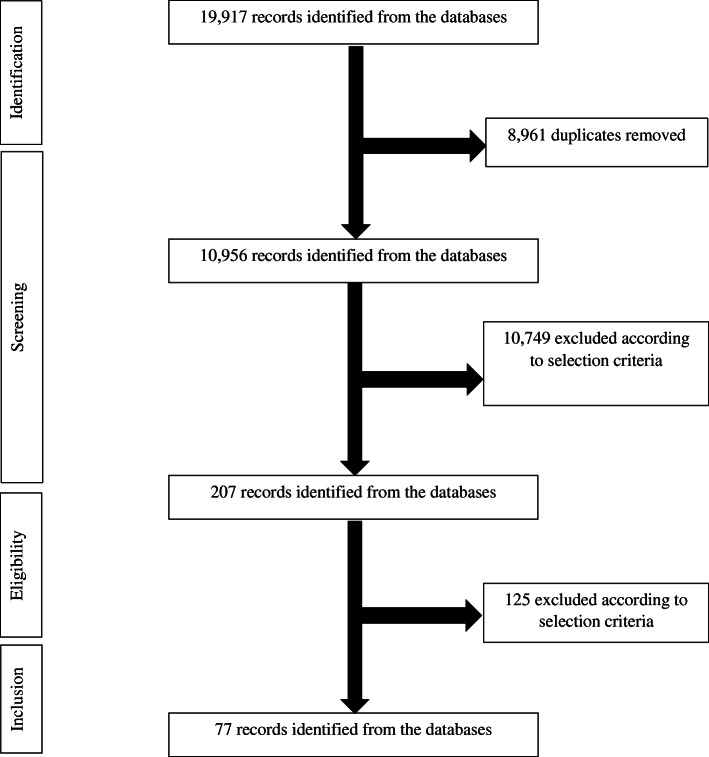

A total of 19,917 titles were screened following database searches and hand searching of bibliographies, and 8961 titles were excluded (Fig. 1). The search hits of all databases are showed in Supplement 2. The remaining 10,749 abstracts were reviewed. A total of 207 articles were included for full-text data review, and 77 were selected based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. BCW classifications were coded for all interventions described in the eligible manuscripts and then included in the meta-analyses.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies included in the systematic review

Characteristics of studies

The 77 studies included in the meta-analyses represent 40,614 IVT cases, and their general characteristics are shown in Table 1. All were published between 2002 and 2018. There were 29 (38%) studies from European countries, 26 (34%) from North American countries, 17 (22%) from Asian countries, four (5%) from Australia and one (1%) from South America. In the methods used, 58% (45/77) were uncontrolled before-and-after, 29% (22/77) were parallel group trial and 13% (10/77) were randomised controlled in design. For the factors the interventions addressed, 35 (45%) addressed in-hospital factors, 33 (43%) addressed pre- and in-hospital factors and nine (12%) addressed pre-hospital factors only.

Quality of studies

The quality scores across studies were normally distributed with a mean of 78 and SD of 11, as shown in Table 2. The highest mean score of 97 (SD 7) was observed in the randomised controlled trial group, followed by similar scores of 76 (SD 7) and 74 (SD 9) for the parallel group trial and the uncontrolled before-and-after study group, respectively.

Table 2.

Summary of study characteristics and outcome measures

| First author and publication year | Study information | BCW intervention functions employed | Number received IVT | Total number of patients | % received IVT | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Addressed factor | Study design | Quality score (%) | Typea | Number | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | |

| Behrens et al. 2002 [20] | Germany | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 63 | 1,5,9 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 86 | 57 | 10 | 2 |

| Morgenstern et al. 2003 [21] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 89 | 1,5,7,8,9 | 5 | 9 | 1 | 80 | 70 | 11 | 1 |

| Lattimore et al. 2003 [22] | USA | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 50 | 1,5,7,9 | 4 | 44 | 3 | 420 | 200 | 10 | 2 |

| Belvis et al. 2005 [23] | Spain | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 67 | 2, | 1 | 7 | 8 | 37 | 181 | 19 | 4 |

| Wojner-Alexandrov et al. 2005 [24] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 1,2,5,9,7 | 4 | 64 | 21 | 709 | 192 | 9 | 11 |

| Ickenstein et al. 2005 [25] | Germany | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 67 | 2,5,9,1,7 | 5 | 45 | 10 | 164 | 155 | 27 | 6 |

| Nam et al. 2007 [26] | South Korea | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 67 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 25 | 14 | 213 | 529 | 12 | 3 |

| Demaerschalk et al. 2008 [27] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 1,9 | 2 | 320 | 4 | 1800 | 1454 | 18 | 0 |

| Abdullah et al. 2008 [28] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 79 | 2, | 1 | 18 | 16 | 44 | 74 | 41 | 22 |

| Quain et al. 2008 [29] | Australia | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 88 | 2,5,7,9 | 4 | 30 | 5 | 140 | 107 | 21 | 5 |

| Gladstone et al. 2009 [30] | Canada | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 58 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 30 | 7 | 128 | 74 | 23 | 9 |

| Pedrogosa et al. 2009 [31] | Spain | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 2,9 | 2 | 19 | 9 | 198 | 201 | 10 | 4 |

| Chenkin et al. 2009 [32] | Canada | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 5,2,9 | 3 | 56 | 18 | 554 | 307 | 10 | 6 |

| Muller-Nordhorn et al. 2009 [33] | Germany | Pre-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 1,5 | 2 | 17 | 13 | 741 | 647 | 2 | 2 |

| Kim et al. 2009 [34] | South Korea | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 2,9,7 | 3 | 47 | 44 | 328 | 678 | 14 | 6 |

| Heo et al. 2010 [35] | South Korea | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 7,9,2 | 3 | 312 | 199 | 5404 | 5798 | 6 | 3 |

| Dharmasaroja et al. 2010 [36] | Thailand | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 67 | 1,2,5,9 | 4 | 110 | 14 | 406 | 170 | 27 | 8 |

| Bae et al. 2010 [37] | South Korea | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 79 | 2, | 1 | 33 | 18 | 55 | 47 | 60 | 38 |

| Sung et al. 2011 [38] | Taiwan | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 9, | 1 | 21 | 40 | 139 | 338 | 15 | 12 |

| Reiner-Deitemyer et al. 2011 [39] | Austria | Pre-hospital | Parallel group trial | 63 | 9, | 1 | 224 | 1062 | 898 | 13,731 | 25 | 8 |

| Hoegerl et al. 2011 [40] | USA | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 1,7,9 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 101 | 132 | 12 | 3 |

| Etgen et al. 2011 [41] | Germany | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 5,7,9,2 | 4 | 95 | 24 | 742 | 500 | 13 | 5 |

| Walter et al. 2011 [42] | Germany | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 9,7 | 2 | 16 | 32 | 78 | 120 | 21 | 27 |

| Driks et al. 2011 [43] | Netherland | In-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 1,7,9 | 3 | 391 | 305 | 2990 | 2525 | 13 | 12 |

| Addo et al. 2012 [44] | UK | Pre-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 88 | 1, | 1 | 45 | 55 | 274 | 326 | 16 | 17 |

| Walter et al. 2012 [42] | Germany | Pre-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 9,7 | 2 | 12 | 8 | 53 | 47 | 23 | 17 |

| O'Brien et al. 2012 [45] | Australia | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 67 | 1,2 | 2 | 22 | 5 | 115 | 67 | 19 | 7 |

| Berglund et al. 2012 [46] | Sweden | Pre- and in-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 81 | 2,9 | 2 | 60 | 24 | 488 | 454 | 12 | 5 |

| Prabhakaran et al. 2012 [47] | USA | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 71 | 9, | 1 | 3335 | 732 | 58,512 | 61,027 | 6 | 1 |

| Bhatt et al. 2012 [48] | USA | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 9, | 1 | 47 | 60 | 484 | 789 | 10 | 8 |

| Scott et al. 2013 [49] | USA | In-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 1,2,9 | 3 | 235 | 194 | 8419 | 9222 | 3 | 2 |

| Meretoja et al. 2013 [50] | Australia | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 47 | 82 | 324 | 468 | 15 | 18 |

| McKinney et al. 2013 [51] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 88 | 2, | 1 | 31 | 17 | 114 | 115 | 27 | 15 |

| Amorim et al. 2013 [52] | USA | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 67 | 9,2 | 2 | 113 | 26 | 1669 | 919 | 7 | 3 |

| Nolte et al. 2013 [53] | Germany | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 2, | 1 | 51 | 14 | 64 | 36 | 80 | 39 |

| Prabhakaran et al. 2013 [47] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 2, | 1 | 64 | 22 | 787 | 719 | 8 | 3 |

| Schaik et al. 2014 [54] | Netherland | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 185 | 41 | 951 | 828 | 19 | 5 |

| Fonarow et al. 2014 [55] | USA | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 3552 | 1557 | 43,850 | 27,319 | 8 | 6 |

| Ebinger et al. 2014 [56] | Germany | Pre-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 9,7 | 2 | 310 | 220 | 1070 | 1041 | 29 | 21 |

| Minnerup et al. 2014 [57] | Germany | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 63 | 9, | 1 | 13,240 | 622 | 71,349 | 22,549 | 19 | 3 |

| Camerlingo et al. 2014 [58] | Italy | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 1,5,9 | 3 | 23 | 8 | 401 | 376 | 6 | 2 |

| Ruff et al. 2014 [59] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 142 | 116 | 925 | 1413 | 15 | 8 |

| Hesselfeldt et al. 2014 [60] | Denmark | Pre-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 9, | 1 | 22 | 87 | 65 | 265 | 34 | 33 |

| Chen et al. 2014 [61] | Taiwan | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 88 | 2, | 1 | 216 | 91 | 2512 | 3500 | 9 | 3 |

| Martinez-Sanchez et al. 2014 [62] | Spain | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 9,2 | 2 | 18 | 12 | 225 | 259 | 8 | 5 |

| Ragoschke-Schumm et al. 2015 [63] | UK | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 7, | 1 | 66 | 49 | 174 | 81 | 38 | 60 |

| Willeit et al. 2015 [64] | Austria | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2,7 | 2 | 160 | 82 | 1238 | 1237 | 13 | 7 |

| Kim et al. 2015 [65] | South Korea | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2, | 1 | 202 | 44 | 341 | 132 | 59 | 33 |

| Baldin et al. 2015 [66] | Australia | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 79 | 9,2 | 2 | 16 | 10 | 62 | 58 | 26 | 17 |

| Moran et al. 2016 [67] | Hawaii | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 9, or 7 | 1 | 122 | 44 | 388 | 151 | 31 | 29 |

| Busby et al. 2016 [68] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2, | 1 | 52 | 41 | 397 | 414 | 13 | 10 |

| Choi et al. 2016 [69] | South Korea | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 58 | 7,9 | 2 | 118 | 111 | 2078 | 2172 | 6 | 5 |

| Nishijima et al. 2016 [70] | Japan | Pre-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 1, | 1 | 36 | 41 | 600 | 544 | 6 | 8 |

| Kim et al. 2016 [71] | South Korea | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 2, | 1 | 215 | 59 | 306 | 136 | 70 | 43 |

| Prabhakaran et al. 2016 [72] | USA | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 1,3,7,9 | 4 | 766 | 1626 | 10,314 | 15,261 | 7 | 11 |

| Hubert et al. 2016 [73] | Finland | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 83 | 9,2 | 2 | 1779 | 912 | 11,589 | 3387 | 15 | 27 |

| Itrat et al. 2016 [74] | USA | Pre-hospital | Parallel group trial | 83 | 9,7 | 2 | 16 | 13 | 110 | 56 | 15 | 23 |

| Denti et al. 2017 [75] | Italy | Pre-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 1, | 1 | 145 | 156 | 649 | 503 | 22 | 31 |

| Zaidi et al. 2017 [76] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 79 | 2,5,7 | 3 | 28 | 18 | 109 | 142 | 26 | 13 |

| Heikkila et al. 2019 [77] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 71 | 9, | 1 | 51 | 124 | 355 | 1581 | 14 | 8 |

| Hsiao et al. 2018 [78] | Taiwan | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 2, | 1 | 40 | 18 | 254 | 118 | 16 | 15 |

| Carvalho et al. 2018 [79] | Brazil | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 5,7 | 2 | 28 | 13 | 154 | 61 | 18 | 21 |

| Gurav et al. 2018 [80] | India | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2, | 1 | 65 | 44 | 610 | 695 | 11 | 6 |

| Tan et al. 2018 [81] | Sweden | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 75 | 2,7 | 2 | 281 | 129 | 826 | 416 | 34 | 31 |

| Haesebaert et al. 2018 [82] | France | Pre- and in-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 1,5,7 | 3 | 140 | 114 | 363 | 328 | 39 | 35 |

| Nguyen-Huynh et al. 2018 [83] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 88 | 2,7,9 | 3 | 557 | 310 | 3168 | 2375 | 18 | 13 |

| Cone et al. 2018 [84] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 2, | 1 | 94 | 181 | 219 | 316 | 43 | 57 |

| Sadeghi-Hokmabadi et al. 2018 [85] | Iran | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 79 | 2, | 1 | 131 | 115 | 180 | 194 | 73 | 59 |

| Meyer et al. 2008 [86] | USA | In-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 89 | 9,2 | 2 | 31 | 28 | 111 | 111 | 28 | 25 |

| de Luca et al. 2009 [87] | Italy | In-hospital | Randomised controlled trial | 100 | 5,9 | 2 | 15 | 2 | 434 | 328 | 3 | 1 |

| Muller-Barna et al. 2014 [88] | Germany | In-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 9,2 | 2 | 655 | 63 | 4409 | 2466 | 15 | 3 |

| Vidale et al. 2016 [89] | Italy | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 75 | 2,5,7 | 3 | 37 | 14 | 610 | 424 | 6 | 3 |

| Nardetto et al. 2016 [90] | Italy | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 71 | 9,2 | 2 | 25 | 106 | 75 | 318 | 33 | 33 |

| Hsieh et al. 2016 [91] | Taiwan | Pre- and in-hospital | Parallel group trial | 79 | 2, | 1 | 144 | 25 | 727 | 201 | 20 | 12 |

| Jeon et al. 2017 [92] | South Korea | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 83 | 2,7 | 2 | 34 | 141 | 297 | 2012 | 11 | 7 |

| Zhou et al. 2017 [93] | China | In-hospital | Parallel group trial | 71 | 9, | 1 | 231 | 88 | 712 | 689 | 32 | 13 |

| Henry-Morrow et al. 2017 [94] | USA | Pre- and in-hospital | Uncontrolled before and after | 50 | 1, | 1 | 16 | 8 | 82 | 38 | 20 | 21 |

aCoding of BCW intervention function type: Education = 1, Persuasion = 2, Incentivisation = 3, Coercion = 4, Training = 5, Restriction = 6, Environmental restructuring = 7, Modelling = 8, Enablement = 9

Description on behaviour change wheel categories

Twenty nine (38%) studies implemented one BCW component, 22 (29%) implemented two components, 18 (23%) implemented three components and 8 (10%) implemented more than 3 components. Of the types of BCW interventions included, 47 (61%) studies included at least enablement, 46 (60%) included at least persuasion, 31 (40%) at least environmental restructuring, 19 (25%) at least education and 16 (21%) at least training.

Outcome measures

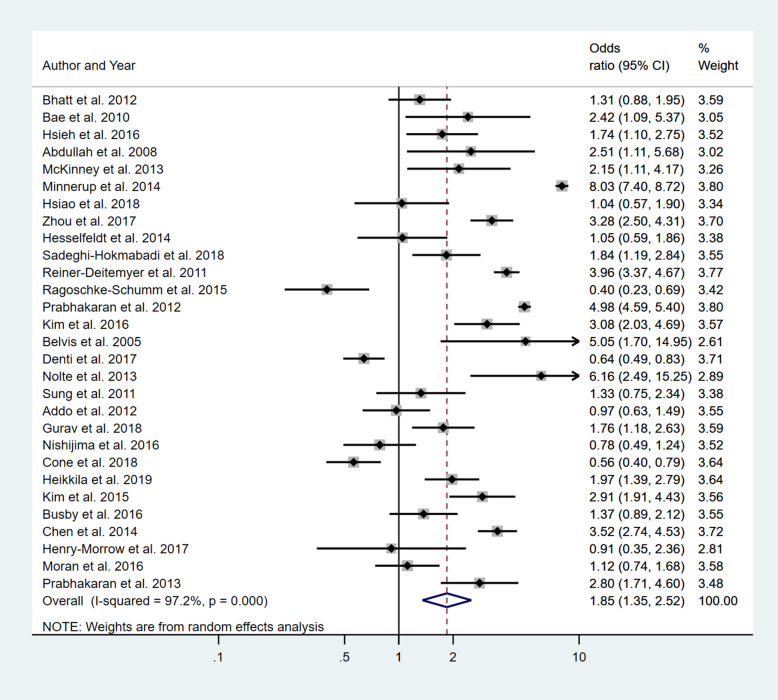

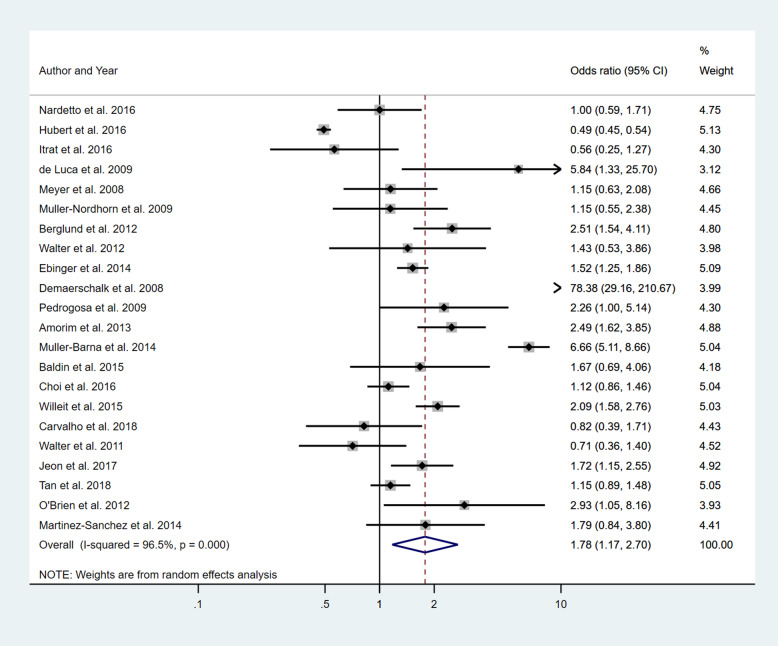

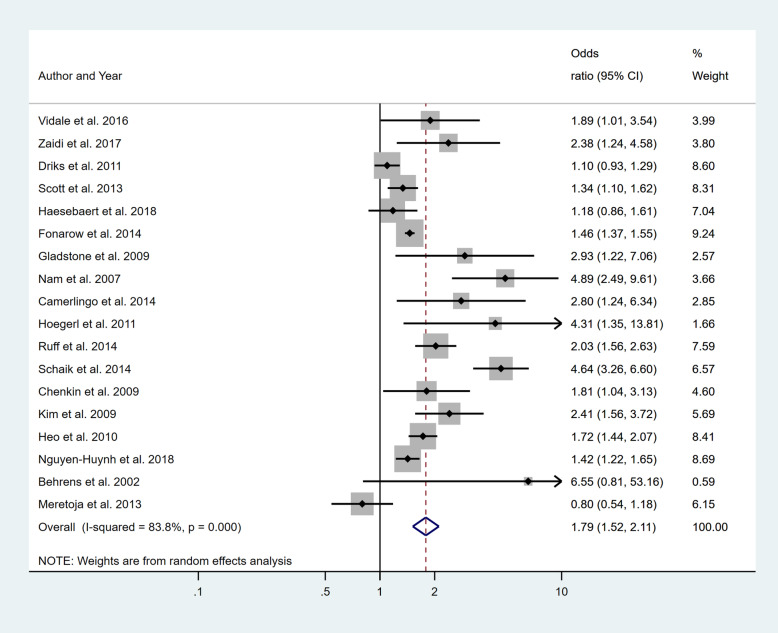

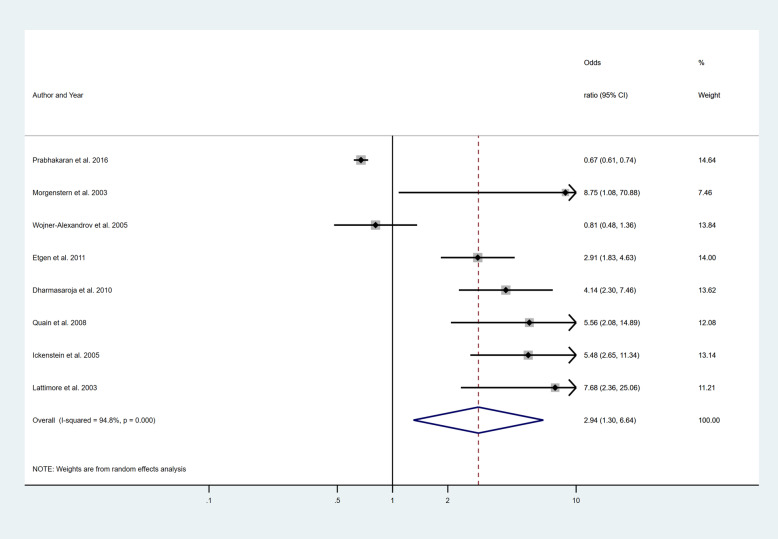

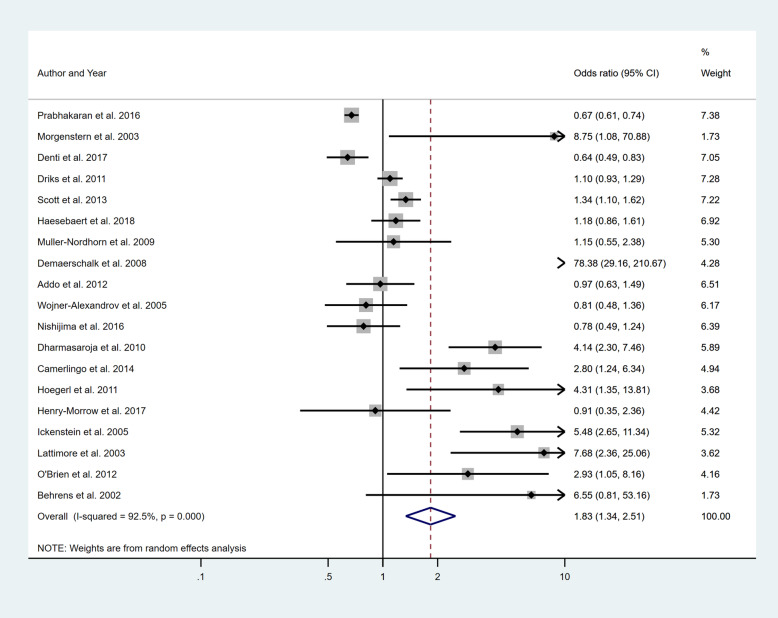

Four separate meta-analyses were conducted to assess the effect of incorporating one, two, three or more BCW intervention types (Fig. 2, 3, 4 and 5). All four analyses found significant overall improvements in rates of IVT delivery, with odds ratio of between 1.78 to 2.94, with largely overlapping confidence intervals. High heterogeneity was seen in all meta-analyses (I2 range 84 to 97%). Sub-group analyses based on the hospital factors addressed by the intervention, the denominator used and epidemiological design of the study indicated that heterogeneity (I2) still ranged from moderate to high. A sensitivity analysis that excluded the results of an outlier study (Demaerschalk et al. [27]) did not result in any substantial change in the results or conclusions.

Fig. 2.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included only one BCW intervention

Fig. 3.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included two BCW intervention functions

Fig. 4.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included three BCW intervention functions

Fig. 5.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included four to five BCW intervention functions

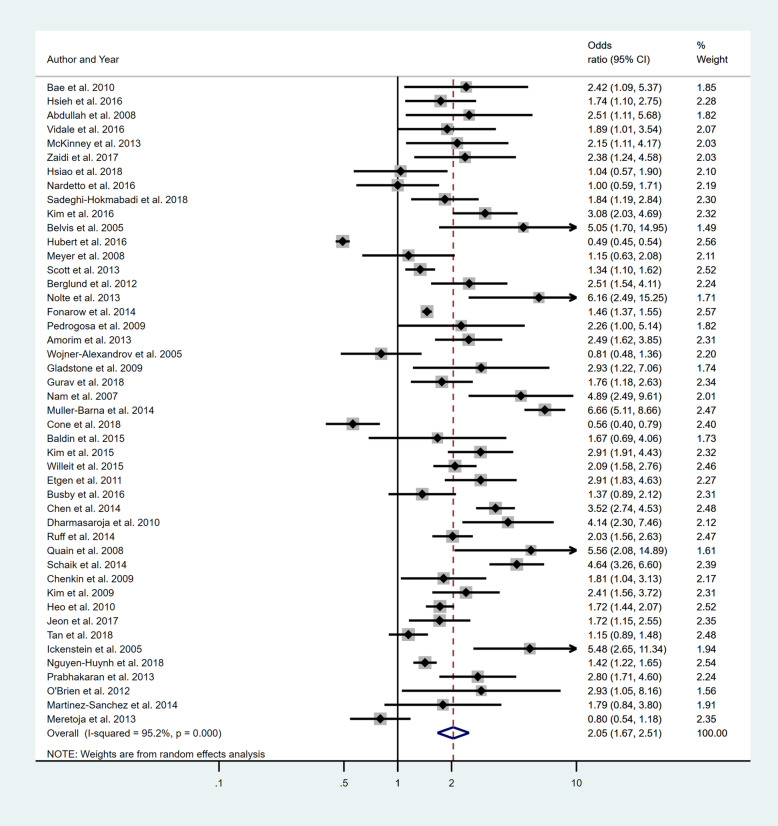

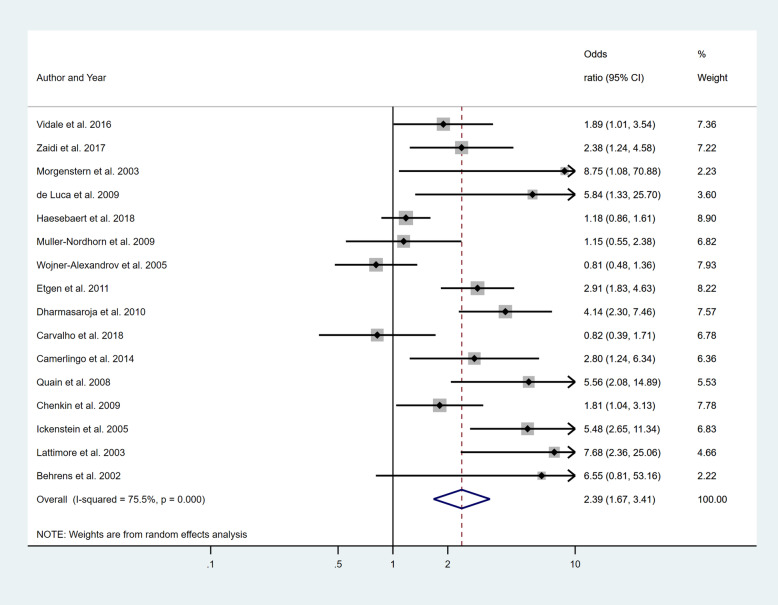

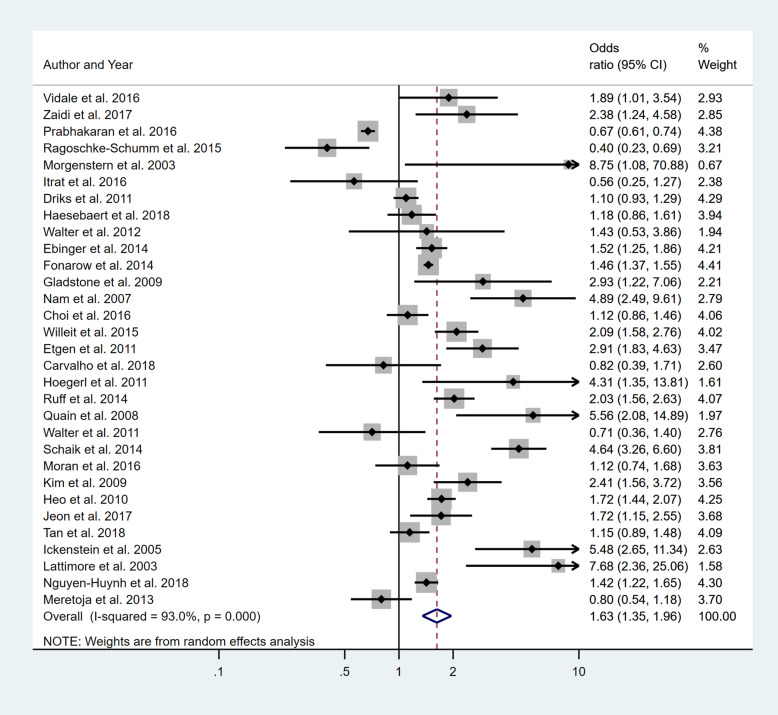

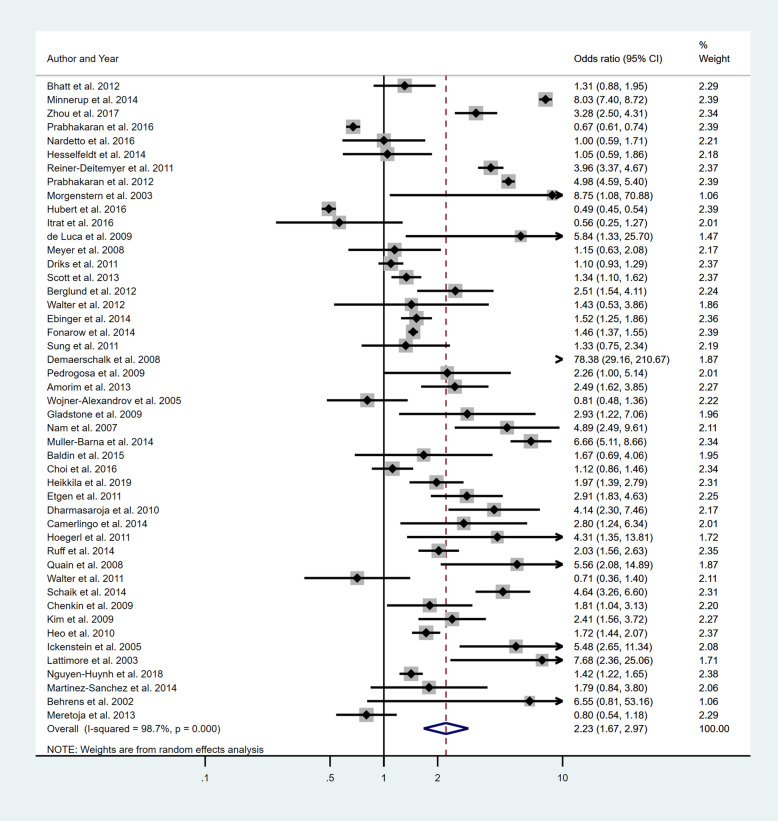

Five separate meta-analyses (Figs. 6, 7, 8, 9 and 10) were conducted to assess the effect of including at least one of the five BCW intervention types. All five found significant improvement in rates of IVT delivery, with odds ratios of between 1.63 and 2.39 with largely overlapping confidence intervals. High heterogeneity was seen in all meta-analyses (I2 range 75.5 to 98.8%). Sub-group analyses based on hospital factors addressed by the intervention, denominator used and epidemiological design of the study were again conducted and exhibited moderate to high levels of heterogeneity (I2). A sensitivity analysis excluding the results of the outlier, Demaerschalk et al. [27] study, was again performed, but this did not substantially change the results.

Fig. 6.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included an education component, at minimum

Fig. 7.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included a persuasion component, at minimum

Fig. 8.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included a Training component, at minimum

Fig. 9.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included an Environmental restructuring component, at minimum

Fig. 10.

Pooled odds ratio of the intervention effectiveness in the studies that included an Enablement component, at minimum

The meta-regression analysis undertaken to assess whether the number of BCW interventions were associated with efficacy, showed no statistically significant association (OR 1.10; 95% CI 0.93, 1.32, p = 0.26).

The contour-enhanced funnel plots investigating the type and number of BCW interventions employed indicated the likelihood of a small-study bias across all meta-analyses, and this is confirmed by Egger’s test (Supplementary file 6, and Supplementary file 7). The missing regions in the contour-enhanced funnel plots indicate that the bias is likely due to a mix of heterogeneity and publication bias. We analysed our results based on various study types (including pre-hospital versus in-hospital) and evaluated the effect on the outcomes. However, the result was the same—an overall significant result with all sub-groups. This result also indicated high heterogeneity and potential publication bias (Supplementary file 8, Supplementary file 9, and Supplementary file 10). Since RCTs provide the strongest evidence, we also looked at the results within the RCT sub-group. In this sub-group, meta-analysis revealed a statistically significant improvement in promoting IVT delivery with an OR of 1.55 (95% CI 1.02–2.35) for the interventions including at least persuasion, OR 1.44 (95% CI 1.04–1.80) for enablement and OR 1.26 (95% CI 1.03–1.54) for environmental restructuring.

Discussion

The findings of this systematic review and meta-analyses bring together empirical evidence regarding the strategies that are potentially effective in improving IVT rates for AIS. This is the first review to evaluate the differential effect of implementation interventions using a theory-informed (i.e. COM-B) approach using the BCW framework to increase the information available about effective intervrention content. This study found similar overall benefits for the five BCW intervention approaches reviewed. Using the BCW nomenclature, education, persuasion, training, environmental restructuring and enablement all increase thrombolysis uptake with odds ratios of approximately 2. Because the pooled effect sizes were largely overlapping, there seems to be no clear ‘winner’ in terms of which strategy has the largest effect for improving rates of IVT for AIS.

The COM-B theory proposes that multiple aspects of behaviour (capability, opportunity and motivation) are necessary to performing a given behaviour, and the BCW framework proposes multiple factors (education, training, etc.) which support and drive behaviour at an individual and system level. Despite the theory-driven expectation that multiple implementation intervention strategies may potentially increase success in the context of a complex multi-step health care practice, we found no evidence that increasing the number of BCW strategies used in an intervention programme resulted in increased effectiveness. However, the sub-group analysis of RCTs provides some suggestion that persuasion, environmental restructuring and enablement may be particularly effective.

The results should be interpreted with caution based on the existence of both high study heterogeneity or variability of studies, and publication bias. Heterogeneity describes the degree of variability among studies. The presence of high heterogeneity in this study indicates that the true intervention effect may be different in different studies. On the other hand, the presence of bias indicates the possibility of having overestimated the summary effect size [19]. Therefore, until there is more substantial evidence, rather than selecting an intervention approach based on the literature, it may be more relevant to select approaches which best address the major barriers in a given health service context. The findings of the current study align with those of McDermott et al. [4] who concluded that it was difficult to identify any one particular most effective strategy because the overall effects of the identified strategies were almost the same [4]. Conversely, Huang et al. [7] concluded that interventions reducing in-hospital delays may serve as the most effective way to increase IVT delivery; however, several approaches were included under the ‘in-hospital’ approach, which made it difficult to recommend any specific approaches, and they did not find strong evidence to suggest a minimum or maximum number of interventions were required to achieve maximum success.

Although it is unclear why particular strategies were chosen by studies’ authors, it was feasible to categorise the type of intervention strategies used using the BCW theoretical framework and to assign interventions to the categories of education, persuasion, training, environmental restructuring and enablement. This is the only systematic review and meta-analysis that has evaluated the effect of implementation interventions aimed at increasing rates of IVT for AIS using a theoretical framework. However, it should be noted that the studies analysed often did not provide enough detail to unambiguously classify the intervention components based on BCW intervention functions. The inability to find differences in the effect of different BCW intervention functions in improving IVT rates may be due to the fact that the 5 categories are relatively coarse. The BCW intervention functions do lend themselves to finer classification but a lack of detailed information in many of the studies reviewed precluded us using this finer-grained classification. Our study also failed to identify any relationship between the number of intervention components and effectiveness of the intervention. A systematic review on multi-component healthcare interventions indicated that multi-component interventions are difficult to implement and seldom implemented as planned [95]. Complex multi-level multi-component interventions or strategies are more difficult to implement and reproduce in the practical setting with fidelity. Multiple strategies may be needed to engage the variety of professionals involved in care such as IVT, which can increase the level of difficulty when implementing or replicating such interventions [96]. Several studies have showed that poor implementation can reduce intervention impact [97]. Therefore, considering the level of complexity in the implementation process, using multi-component BCW interventions in one package may be challenging.

This study has several strengths and limitations. One limitation, as mentioned above, was that the coding for the BCW intervention functions was based on the information available in the studies’ publications only. Given that the reviewed literature focused on reporting outcome-related aspects of methodology including outcome measures and sample size rather than describing intervention development and content, the literature provides only a very limited understanding of the types of behaviour change interventions that can be effective. A more inter-disciplinary approach to designing these trials may be needed to progress the field. If more explicit descriptions of the intervention used were to be published, this may allow for more in-depth classification and, in turn, more capacity to isolate specific BCW strategies associated with change in AIS practice. It must be acknowledged however, that there is a tension between multi-component and single-focus studies in implementation science. Successful implementation of complex evidence-based practices in any given healthcare setting may require a variety of behaviour change interventions to be implemented. Therefore, evaluating the effectiveness of one BCW intervention function over another might not always be enough to understand how to effect change on a multi-level multi-component process within a complex health system. One strength of the review is the large number of studies which were included and the total of 40,614 IVT cases, thus giving weight to the results. Other strengths include the rigorous review process used to identify studies and extract data, and the use of the BCW theoretical framework for pooling the intervention effects. Our results may assist researchers with the development of future interventions, including avoiding the assumption that using multiple strategies will necessarily increase intervention effectiveness.

In terms of implications for practice in stroke care, this review suggests that despite the complexity of the IVT care pathway, successfully increasing IVT rates does not necessarily require a complex suite of implementation intervention components, nor should it focus on one specific type of intervention function. Therefore, it seems reasonable to suggest that successful interventions will be those that draw on the diversity of potential interventions to address identified challenges in the local context by paying close attention to each aspect of the patient pathway.

Conclusion

The evidence we provide does not support using one specific type of BCW intervention strategy over another in the setting of IVT implementation and also that using multiple BCW intervention strategies in the same programme may not necessarily increase intervention effectiveness. A more inter-disciplinary approach to study design may be needed. A caveat, however, is that the sub-group analysis with RCTs suggested more effect with persuasion, environmental restructuring and enablement approaches. Our results suggest it may be more relevant for policy makers and implementation scientists to select the approaches that best address the major obstacles in a given context. However, because of the high degree of heterogeneity and publication bias, these conclusions cannot be considered robust.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AIS

Acute ischemic stroke

- BCW

Behaviour change wheel

- CI

Confidence interval

- IVT

Intravenous thrombolysis

- OR

Odds ratio

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-analyses

Authors’ contributions

MGH directed the review; conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal, carried out the meta-analysis and drafted the manuscript under the supervision of JRA, IJH, CRL and CLP. JRA contributed to the planning of the review, supervised the analysis and commented on the manuscript. SA conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal and commented on the manuscript. TR conducted the screening, data extraction and quality appraisal and commented on the manuscript. AH conducted the meta-analysis and commented on the manuscript. IJH and CRL contributed to the planning of the review and commented on the manuscript. CLP contributed to planning the review, advised throughout the review process and contributed to and commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Md Golam Hasnain, Email: mdgolam.hasnain@uon.edu.au.

John R. Attia, Email: john.attia@newcastle.edu.au

Shahinoor Akter, Email: shahinoor.akter@uon.edu.au.

Tabassum Rahman, Email: tabassum.rahman@newcastle.edu.au.

Alix Hall, Email: alix.hall@hmri.org.au.

Isobel J. Hubbard, Email: isobel.hubbard@newcastle.edu.au

Christopher R. Levi, Email: christopher.levi@unsw.edu.au

Christine L. Paul, Email: chris.paul@newcastle.edu.au

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1186/s13012-020-01054-3.

References

- 1.GBD 2016 Stroke Collaborators Global, regional, and national burden of stroke, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. 2019;18(5):439–458. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(19)30034-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bansal S, Sangha KS, Khatri P. Drug treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs. 2013;13(1):57–69. doi: 10.1007/s40256-013-0007-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(24):1581–1587. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512143332401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDermott M, Skolarus LE, Burke JF. A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions to increase stroke thrombolysis. BMC Neurol. 2019;19(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s12883-019-1298-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evenson KR, Foraker RE, Morris DL, Rosamond WD. A comprehensive review of prehospital and in-hospital delay times in acute stroke care. Int J Stroke. 2009;4(3):187–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2009.00276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eissa A, Krass I, Bajorek BV. Barriers to the utilization of thrombolysis for acute ischaemic stroke. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(4):399–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2011.01329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang Q, Zhang JZ, Xu WD, Wu J. Generalization of the right acute stroke promotive strategies in reducing delays of intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: a meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(25):e11205. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000011205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul CL, Ryan A, Rose S, Attia JR, Kerr E, Koller C, et al. How can we improve stroke thrombolysis rates? A review of health system factors and approaches associated with thrombolysis administration rates in acute stroke care. Implement Sci. 2016;11:51. doi: 10.1186/s13012-016-0414-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, Kinmonth AL, Sandercock P, Spiegelhalter D, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel—a guide to designing interventions. Great Britain: Silverback; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M; Medical Research Council Guidance. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6:42. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-6-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nilsen P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement Sci. 2015;10:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Shrier I, Boivin JF, Steele RJ, Platt RW, Furlan A, Kakuma R, et al. Should meta-analyses of interventions include observational studies in addition to randomized controlled trials? A critical examination of underlying principles. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166(10):1203–1209. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA Statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1006–1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams HP, Jr, Brott TG, Furlan AJ, Gomez CR, Grotta J, Helgason CM, et al. Guidelines for thrombolytic therapy for acute stroke: a supplement to the guidelines for the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from a special writing group of the stroke council. Am Heart Assoc Circ. 1996;94(5):1167–1174. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.1167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kmet L, Lee R, Cook L. Standard quality assessment criteria for evaluating primary research papers from a variety of fields, 2004. Edmonton: Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akter S, Davies K, Rich JL, Inder KJ. Indigenous women’s access to maternal healthcare services in lower- and middle-income countries: a systematic integrative review. Int J Public Health. 2019;64(3):343–353. doi: 10.1007/s00038-018-1177-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 2. Chichester (UK): John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens S, Daffertshofer M, Interthal C, Ellinger K, Van Ackern K, Hennerici M. Improvement in stroke quality management by an educational programme. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13:262–266. doi: 10.1159/000057853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgenstern LB, Bartholomew LK, Grotta JC, Staub L, King M, Chan W. Sustained benefit of a community and professional intervention to increase acute stroke therapy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:2198–2202. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.18.2198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lattimore SU, Chalela J, Davis L, DeGraba T, Ezzeddine M, Haymore J, et al. Impact of establishing a primary stroke center at a community hospital on the use of thrombolytic therapy: the NINDS Suburban Hospital Stroke Center experience. Stroke. 2003;34:e55–e57. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000073789.12120.F3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belvis R, Cocho D, Marti-Fabregas J, Pagonabarraga J, Aleu A, Garcia-Bergo MD, et al. Benefits of a prehospital stroke code system. Feasibility and efficacy in the first year of clinical practice in Barcelona, Spain. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2005;19:96–101. doi: 10.1159/000082786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wojner-Alexandrov AW, Alexandrov AV, Rodriguez D, Persse D, Grotta JC. Houston paramedic and emergency stroke treatment and outcomes study (HoPSTO) Stroke. 2005;36:1512–1518. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000170700.45340.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ickenstein GW, Horn M, Schenkel J, Vatankhah B, Bogdahn U, Haberl R, et al. The use of telemedicine in combination with a new stroke-code-box significantly increases t-PA use in rural communities. Neurocrit Care. 2005;3(1):27–32. doi: 10.1385/NCC:3:1:027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam HS, Han SW, Ahn SH, Lee JY, Choi HY, Park IC, et al. Improved time intervals by implementation of computerized physician order entry-based stroke team approach. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23(4):289–293. doi: 10.1159/000098329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Demaerschalk BM, Bobrow BJ, Paulsen M. Development of a metropolitan matrix of primary stroke centers: the Phoenix experience. Stroke. 2008;39:1246–1253. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.500678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abdullah AR, Smith EE, Biddinger PD, Kalenderian D, Schwamm LH. Advance hospital notification by EMS in acute stroke is associated with shorter door-to-computed tomography time and increased likelihood of administration of tissue-plasminogen activator. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2008;12:426–431. doi: 10.1080/10903120802290828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quain DA, Parsons MW, Loudfoot AR, Spratt NJ, Evans MK, Russell ML, et al. Improving access to acute stroke therapies: a controlled trial of organised pre-hospital and emergency care. Med J Aust. 2008;189:429–433. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gladstone DJ, Rodan LH, Sahlas DJ, Lee L, Murray BJ, Ween JE, et al. A citywide prehospital protocol increases access to stroke thrombolysis in Toronto. Stroke. 2009;40:3841–3844. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.540377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pedragosa A, Alvarez-Sabin J, Molina CA, Sanclemente C, Martín MC, Alonso F, et al. Impact of a telemedicine system on acute stroke care in a community hospital. J Telemed Telecare. 2009;15:260–263. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2009.090102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chenkin J, Gladstone DJ, Verbeek PR, Lindsay P, Fang J, Black SE, et al. Predictive value of the Ontario prehospital stroke screening tool for the identification of patients with acute stroke. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2009;13:153–159. doi: 10.1080/10903120802706146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller-Nordhorn J, Wegscheider K, Nolte CH, Jungehülsing GJ, Rossnagel K, Reich A, et al. Population-based intervention to reduce prehospital delays in patients with cerebrovascular events. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1484–1490. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SK, Lee SY, Bae HJ, Lee YS, Kim SY, Kang MJ, et al. Pre-hospital notification reduced the door-to-needle time for iv t-PA in acute ischaemic stroke. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:1331–1335. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heo JH, Kim YD, Nam HS, Hong KS, Ahn SH, Cho HJ, et al. A computerized in-hospital alert system for thrombolysis in acute stroke. Stroke. 2010;41:1978–1983. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.583591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dharmasaroja PA, Muengtaweepongsa S, Kommarkg U. Implementation of Telemedicine and Stroke Network in thrombolytic administration: comparison between walk-in and referred patients. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:62–66. doi: 10.1007/s12028-010-9360-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bae HJ, Kim DH, Yoo NT, Choi JH, Huh JT, Cha JK, et al. Prehospital notification from the emergency medical service reduces the transfer and intra-hospital processing times for acute stroke patients. J Clin Neurol. 2010;6:138–142. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2010.6.3.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sung SF, Huang YC, Ong CT, Chen YW. A parallel thrombolysis protocol with nurse practitioners as coordinators minimized door-to-needle time for acute ischemic stroke. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:198518. doi: 10.4061/2011/198518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reiner-Deitemyer V, Teuschl Y, Matz K, Reiter M, Eckhardt R, Seyfang L, et al. Helicopter transport of stroke patients and its influence on thrombolysis rates: data from the Austrian Stroke Unit Registry. Stroke. 2011;42:1295–1300. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.604710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoegerl C, Goldstein FJ, Sartorius J. Implementation of a stroke alert protocol in the emergency department: a pilot study. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2011;111:21–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Etgen T, Freudenberger T, Schwahn M, Rieder G, Sander D. Multimodal strategy in the successful implementation of a stroke unit in a community hospital. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;123:390–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2010.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Walter S, Kostopoulos P, Haass A, Lesmeister M, Grasu M, Grunwald I, et al. Point-of-care laboratory halves door-to-therapy-decision time in acute stroke. Ann Neurol. 2011;69:581–586. doi: 10.1002/ana.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dirks M, Niessen LW, van Wijngaarden JD, van Wijngaarden JD, Koudstaal PJ, Franke CL, et al. Promoting thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:1325–1330. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Addo J, Ayis S, Leon J, Rudd AG, McKevitt C, Wolfe CD. Delay in presentation after an acute stroke in a multiethnic population in South London: the South London stroke register. J Am Heart Assoc. 2012;1:e1685. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.112.001685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O’Brien W, Crimmins D, Donaldson W, Risti R, Clarke TA, Whyte S, et al. FASTER (Face, Arm, Speech, Time, Emergency Response): experience of Central Coast Stroke Services implementation of a pre-hospital notification system for expedient management of acute stroke. J Clin Neurosci. 2012;19:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berglund A, Svensson L, Sjostrand C, von Arbin M, von Euler M, Wahlgren N, et al. Higher prehospital priority level of stroke improves thrombolysis frequency and time to stroke unit: the Hyper Acute STroke Alarm (HASTA) study. Stroke. 2012;43:2666–2670. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prabhakaran S, O’Neill K, Stein-Spencer L, Walter J, Alberts MJ. Prehospital triage to primary stroke centers and rate of stroke thrombolysis. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:1126–1132. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2013.293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bhatt A, Shatila A. Neurohospitalists improve door-to-needle times for patients with ischemic stroke receiving intravenous tPA. Neurohospitalist. 2012;2:119–122. doi: 10.1177/1941874412445098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Scott PA, Meurer WJ, Frederiksen SM, Kalbfleisch JD, Xu Z, Haan MN, et al. A multilevel intervention to increase community hospital use of alteplase for acute stroke (INSTINCT): a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:139–148. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70311-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meretoja A, Weir L, Ugalde M, Yassi N, Yan B, Hand P, et al. Helsinki model cut stroke thrombolysis delays to 25 minutes in Melbourne in only 4 months. Neurology. 2013;81:1071–1076. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a4a4d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.McKinney JS, Mylavarapu K, Lane J, Roberts V, Ohman-Strickland P, Merlin MA. Hospital prenotification of stroke patients by emergency medical services improves stroke time targets. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Amorim E, Shih MM, Koehler SA, Massaro LL, Zaidi SF, Jumaa MA, et al. Impact of telemedicine implementation in thrombolytic use for acute ischemic stroke: the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center telestroke network experience. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:527–531. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nolte CH, Malzahn U, Kuhnle Y, Ploner CJ, Müller-Nordhorn J, Möckel M. Improvement of door-to-imaging time in acute stroke patients by implementation of an all-points alarm. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2011.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Schaik SM, Van der Veen B, Van den Berg-Vos RM, Weinstein HC, Bosboom WM, et al. Achieving a door-to-needle time of 25 minutes in thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke: a quality improvement project. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:2900–2906. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2014.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fonarow GC, Zhao X, Smith EE, Saver JL, Reeves MJ, Bhatt DL, et al. Door-to-needle times for tissue plasminogen activator administration and clinical outcomes in acute ischemic stroke before and after a quality improvement initiative. JAMA. 2014;311:1632–1640. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ebinger M, Winter B, Wendt M, Weber JE, Waldschmidt C, Rozanski M, et al. Effect of the use of ambulance-based thrombolysis on time to thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;311:1622–1631. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Minnerup J, Wersching H, Unrath M, Berger K. Effects of emergency medical service transport on acute stroke care. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(10):1344–1347. doi: 10.1111/ene.12367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Camerlingo M, D'Asero S, Perego L, Rovaris C, Tognozzi M, Moschini L, et al. How to improve access to appropriate therapy and outcome of the acute ischemic stroke: a 24-month survey of a specific pre-hospital planning in Northern Italy. Neurol Sci. 2014;35(9):1359–1363. doi: 10.1007/s10072-014-1712-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ruff IM, Ali SF, Goldstein JN, Lev M, Copen WA, McIntyre J, et al. Improving door-to-needle times: a single center validation of the target stroke hypothesis. Stroke. 2014;45(2):504–508. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.004073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hesselfeldt R, Gyllenborg J, Steinmetz J, Do HQ, Hejselbæk J, Rasmussen LS. Is air transport of stroke patients faster than ground transport? A prospective controlled observational study. Emerg Med J. 2014;31:268–272. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2012-202270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chen CH, Tang SC, Tsai LK, Hsieh MJ, Yeh SJ, Huang KY, et al. Stroke code improves intravenous thrombolysis administration in acute ischemic stroke. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Martinez-Sanchez P, Miralles A, Sanz DBR, Prefasi D, Sanz-Cuesta BE, Fuentes B, et al. The effect of telestroke systems among neighboring hospitals: more and better? The Madrid Telestroke Project. J Neurol. 2014;261:1768–1773. doi: 10.1007/s00415-014-7419-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ragoschke-Schumm A, Yilmaz U, Kostopoulos P, Lesmeister M, Manitz M, Walter S, et al. ‘Stroke room’: diagnosis and treatment at a single location for rapid intraarterial stroke treatment. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40:251–257. doi: 10.1159/000440850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Willeit J, Geley T, Schoch J, Rinner H, Tür A, Kreuzer H, et al. Thrombolysis and clinical outcome in patients with stroke after implementation of the Tyrol Stroke Pathway: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:48–56. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(14)70286-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kim A, Lee JS, Kim JE, Paek YM, Chung K, Park JH, et al. Trends in yield of a code stroke program for enhancing thrombolysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2014.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bladin CF, Molocijz N, Ermel S, Bagot KL, Kilkenny M, Vu M, et al. Victorian Stroke Telemedicine Project: implementation of a new model of translational stroke care for Australia. Intern Med J. 2015;45:951–956. doi: 10.1111/imj.12822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Moran JL, Nakagawa K, Asai SM, Koenig MA. 24/7 neurocritical care nurse practitioner coverage reduced door-to-needle time in stroke patients treated with tissue plasminogen activator. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1148–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.01.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Busby L, Owada K, Dhungana S, Zimmermann S, Coppola V, Ruban R, et al. CODE FAST: a quality improvement initiative to reduce door-to-needle times. J Neurointerv Surg. 2016;8:661–664. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2015-011806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Choi HY, Kim EH, Yoo J, Lee K, Song D, Kim YD, et al. Decision-making support using a standardized script and visual decision aid to reduce door-to-needle time in stroke. J Stroke. 2016;18:239–241. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.00374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nishijima H, Ueno T, Kon T, Haga R, Funamizu Y, Arai A, et al. Effects of educational television commercial on pre-hospital delay in patients with ischemic stroke wore off after the end of the campaign. J Neurol Sci. 2017;381:117–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2017.08.3236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kim DH, Nah HW, Park HS, Choi JH, Kang MJ, Huh JT, et al. Impact of prehospital intervention on delay time to thrombolytic therapy in a stroke center with a systemized stroke code program. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:1665–1670. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2016.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prabhakaran S, Lee J, O'Neill K. Regional learning collaboratives produce rapid and sustainable improvements in stroke thrombolysis times. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9(5):585–592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hubert GJ, Meretoja A, Audebert HJ, Tatlisumak T, Zeman F, Boy S, et al. Stroke thrombolysis in a centralized and a decentralized system (Helsinki and Telemedical Project for Integrative Stroke Care Network) Stroke. 2016;47:2999–3004. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.014258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Itrat A, Taqui A, Cerejo R, Briggs F, Cho SM, Organek N, et al. Telemedicine in prehospital stroke evaluation and thrombolysis: taking stroke treatment to the doorstep. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:162–168. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Denti L, Caminiti C, Scoditti U, Zini A, Malferrari G, Zedde ML, et al. Impact on prehospital delay of a stroke preparedness campaign: a SW-RCT (Stepped-Wedge Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial) Stroke. 2017;48(12):3316–3322. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zaidi SF, Shawver J, Espinosa Morales A, Salahuddin H, Tietjen G, Lindstrom D, et al. Stroke care: initial data from a county-based bypass protocol for patients with acute stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9(7):631–635. doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2016-012476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Heikkila I, Kuusisto H, Stolberg A, Pakomaki A. Stroke thrombolysis given by emergency physicians cuts in-hospital delays significantly immediately after implementing a new treatment protocol. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:46. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0237-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hsiao CL, Su YC, Yang FY, Liu CY, Chiang HL, Chen GC, et al. Impact of code stroke on thrombolytic therapy in patients with acute ischemic stroke at a secondary referral hospital in Taiwan. J Chin Med Assoc. 2018;81(11):942–948. doi: 10.1016/j.jcma.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Carvalho VS, Jr, Picanço MR, Volschan A, Bezerra DC. Impact of simulation training on a telestroke network. Int J Stroke. 2019;14(5):500–507. doi: 10.1177/1747493018791030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Gurav SK, Zirpe KG, Wadia RS, Naniwadekar A, Pote PU, Tungenwar A, et al. Impact of "Stroke Code"-Rapid Response Team: an attempt to improve intravenous thrombolysis rate and to shorten door-to-needle time in acute ischemic stroke. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2018;22(4):243–248. doi: 10.4103/ijccm.IJCCM_504_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tan BYQ, Ngiam NJH, Sunny S, Kong WY, Tam H, Sim TB, et al. Improvement in door-to-needle time in patients with acute ischemic stroke via a simple stroke activation protocol. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2018;27(6):1539–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2018.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Haesebaert J, Nighoghossian N, Mercier C, Termoz A, Porthault S, Derex L, et al. Improving access to thrombolysis and inhospital management times in ischemic stroke: a stepped-wedge randomized trial. Stroke. 2018;49(2):405–411. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nguyen-Huynh MN, Klingman JG, Avins AL, Rao VA, Eaton A, Bhopale S, et al. Novel Telestroke program improves thrombolysis for acute stroke across 21 hospitals of an integrated healthcare system. Stroke. 2018;49(1):133–139. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.117.018413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cone DC, Cooley C, Ferguson J, Harrell AJ, Luk JH, Martin-Gill C, et al. Observational multicenter study of a direct-to-CT protocol for EMS-transported patients with suspected stroke. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018;22(1):1–6. doi: 10.1080/10903127.2017.1356410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sadeghi-Hokmabadi E, Farhoudi M, Taheraghdam A, Rikhtegar R, Ghafouri RR, Asadi R, et al. Prehospital notification can effectively reduce in-hospital delay for thrombolysis in acute stroke. Future Neurol. 2018;13(1):5–11. doi: 10.2217/fnl-2017-0031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meyer BC, Raman R, Hemmen T, Obler R, Zivin JA, Rao R, et al. Efficacy of site-independent telemedicine in the STRokE DOC trial: a randomised, blinded, prospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(9):787–795. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70171-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.De Luca A, Toni D, Lauria L, Sacchetti ML, Giorgi Rossi P, Ferri M, et al. An emergency clinical pathway for stroke patients--results of a cluster randomised trial (isrctn41456865) BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Müller-Barna P, Hubert GJ, Boy S, Bogdahn U, Wiedmann S, Heuschmann PU, et al. TeleStroke units serving as a model of care in rural areas: 10-year experience of the TeleMedical project for integrative stroke care. Stroke. 2014;45(9):2739–2744. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.006141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Vidale S, Arnaboldi M, Bezzi G, Bono G, Grampa G, Guidotti M, et al. Reducing time delays in the management of ischemic stroke patients in Northern Italy. Int J Cardiol. 2016;215:431–434. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.03.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nardetto L, Dario C, Tonello S, Brunelli MC, Lisiero M, et al. A one-to-one telestroke network: the first Italian study of a web-based telemedicine system for thrombolysis delivery and patient monitoring. Neurol Sci. 2016;37(5):725–730. doi: 10.1007/s10072-016-2569-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hsieh MJ, Tang SC, Chiang WC, Tsai LK, Jeng JS, Ma MH, et al. Effect of prehospital notification on acute stroke care: a multicenter study. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24:57. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0251-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zhou Y, Xu Z, Liao J, Feng F, Men L, Xu L, et al. New standardized nursing cooperation workflow to reduce stroke thrombolysis delays in patients with acute ischemic stroke. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2017;13:1215–1220. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S128740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jeon SB, Ryoo SM, Lee DH, Kwon SU, Jang S, Lee EJ, et al. Multidisciplinary approach to decrease in-hospital delay for stroke thrombolysis. J Stroke. 2017;19(2):196–204. doi: 10.5853/jos.2016.01802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Henry-Morrow TK, Nelson BD, Conahan E, Mathiesen C, Glenn-Porter B, Niehaus MT, et al. An educational intervention allows for greater prehospital recognition of acute stroke. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:1959–1961. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2017.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Guise JM, Chang C, Viswanathan M, et al. Systematic Reviews of Complex Multicomponent Health Care Interventions [Internet] Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Komro KA, Flay BR, Biglan A, Wagenaar AC. Research design issues for evaluating complex multicomponent interventions in neighborhoods and communities. Transl Behav Med. 2016;6(1):153–159. doi: 10.1007/s13142-015-0358-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Durlak JA, DuPre EP. Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am J Community Psychol. 2008;41(3-4):327–350. doi: 10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.