Abstract

Objectives:

Following the 2012 launch of the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (the National Partnership), the use of antipsychotics has declined. However, little is known about the impact of this effort on quality of care and outcomes for nursing home (NH) residents with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia (ADRD). The objective of this study is to examine changes in hospitalizations for NH long-stay residents with ADRD after the launch of the National Partnership.

Design:

Observational cross-sectional study.

Setting/Participants:

NH residents who were newly admitted into NHs and became long-stay residents between January 2011 and March 2015 (n = 565,885).

Methods:

We estimated linear probability models to explore the relationship between the National Partnership and the likelihood of NH-originated hospitalizations for NH long-stay residents with ADRD, accounting for facility fixed-effect, individual covariates, and concurrent changes in hospitalizations among residents without ADRD. We further stratified the analysis by NHs according to their prevalence of antipsychotic use at baseline (i.e. prior to the National Partnership).

Results:

We detected a 0.7 percentage-point relative increase (p-value<0.01) in risk-adjusted probabilities of hospitalizations among residents with ADRD compare to non-ADRD residents in post-Partnership period. In the stratified analysis, we detected a 1.2 percentage-point increase (p-value=0.037) in the probability of hospitalizations among ADRD residents in NHs with high antipsychotic use at baseline but no significant change among those in NHs with low antipsychotic use.

Conclusion/Implication:

While the National Partnership may have reduced exposure to antipsychotics, our findings suggest this was related to an increase in hospitalization risk for residents with ADRD. Further research is needed to elucidate the reasons behind the observed relationship and to examine the impact of the National Partnership on other health outcomes.

Keywords: nursing homes, antipsychotics, dementia, hospitalization, the National Partnership

Brief summary:

This study found increased risks of hospitalizations among residents with dementia after the launch of the National Partnership, especially in NHs with the high prevalence of antipsychotic use.

INTRODUCTION

More than half of nursing home (NH) residents have Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD),1,2 and many patients with ADRD develop behavioral and psychological symptoms, such as wandering, agitation, or verbal and physical aggression during the course of the illness.3–5 If these behavioral symptoms among NH residents with ADRD are not well managed, they may lead to negative outcomes such as injuries and increased risk of hospitalizations,6–8 as well as pose safety concerns for the non-ADRD co-residents.9

Antipsychotic medications, although labeled for treating psychosis in serious mental illness such as schizophrenia or bipolar disorders, are often used to manage behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia among NH residents.10–12 In the past two decades, there has been increasing evidence suggesting that use of antipsychotics among older ADRD patients is associated with increased risks of adverse events, such as cerebrovascular accidents (CVAs) and fractures,13 leading to higher risk of hospitalizations.14–17 These concerns led the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to issue “black-box warnings” for off-label antipsychotic use among older dementia patients, first for second-generation antipsychotics in 2005 and later expanded to all antipsychotics in 2008.18 However, despite these concerns the prevalence of antipsychotics use in NHs remained high.19,20 A 2015 Government Accountability Office report showed that one third of NH residents with ADRD were prescribed antipsychotics in 2012.21

Aiming to reduce antipsychotic use and improve dementia care in NHs, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) launched the National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes (henceforth referred to as “the National Partnership”) in March 2012. The National Partnership included multi-dimensional approaches, such as setting up state-based coalitions and promoting education and research, but the main component of the National Partnership that affected all NHs in the US was the initiation of public reporting of NH-level antipsychotic use. 22–24

Since the initiation of the National Partnership, there has been a steady and significant reduction in antipsychotic use in NHs:20,24–27 among NH long-stay residents the prevalence decreased from 23.9% in 2011 to 20.2% in 2013, 16.0% in 2016, and 14.6% in 2018. While this declining trend suggests that the National Partnership is achieving its objectives, the implications on health outcomes among residents with ADRD, in particular on hospitalization risk, remain unknown. On one hand, because antipsychotic use has been found to be associated with increased risk of hospitalizations among older patients with ADRD,14–17 the National Partnership may reduce hospitalizations associated with the use of antipsychotics. On the other hand, if NHs do not replace reliance on antipsychotics with patient-centered non-pharmacological alternatives, the reduction in antipsychotics may not result in better outcomes, such as fewer hospitalizations, among ADRD patients, due to the lack of appropriate management of behavioral problems and dementia care. To the best of our knowledge, there is currently no empirical evidence about the impact of the National Partnership on hospitalizations among long-stay NH residents with ADRD. The objectives of this study were to examine the impact of the National Partnership on hospitalization among long-stay NH residents with ADRD, and to assess whether such relationship vary with NHs with initially high versus low-levels of antipsychotic use.

METHODS

DATA AND COHORT

We used the CY2010 – 2015 Minimum Data Set (MDS) 3.0, Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File (MBSF), Medicare Provider and Analysis Review (MedPAR) file, and Nursing Home Compare (NHC) data, linking them at the individual beneficiary level. The MDS 3.0 contains mandatory assessments for all residents in Medicare- or Medicaid- certified NHs, and includes detailed information on individual health status at the time of admission, quarterly if the resident remains in NH, whenever there is a significant change in status, and at discharge. The MBSF contains information on Medicare enrollment, Medicare Advantage plan enrollment, and Medicare-Medicaid dual status. MedPAR contains detailed information on inpatient events, such as dates of admission and discharge for Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) beneficiaries. The NHC data contains facility-level characteristics and quality of care measures, such as the rate of antipsychotic use and quality star ratings, for all Medicare- or Medicaid-certificated NHs.

We used MDS and MBSF data to identify Medicare FFS beneficiaries who were 65 years old or older and were newly admitted to freestanding NHs between January 1, 2011 and March 26, 2015 (to allow for follow-up time to define long-stay residents and hospitalizations, as discussed below). Newly admitted residents were defined as those who did not have any NH stays in the prior 180 days. We further restricted the cohort to long-stay NH residents, defined as being in a NH for at least 100 days. We considered the date when a resident became a long-stay resident as the “baseline” date. We then followed these residents for another 180 days after they became long-stay residents to account for any NH originated hospitalizations. We excluded residents with diagnoses of bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, as the use of antipsychotics is the standard care for these residents. Lastly, we excluded NH residents who became long-stay residents in the second quarter of 2012 because this is a transitional period: the National Partnership was launched, but the public reporting of NH antipsychotic use did not start until July of 2012. Our final analytical sample included 565,885 long-stay NH residents who were newly admitted to 13,770 NHs.

MEASURES

The main outcome was all-cause hospitalization originating from NHs within 180 days after the baseline date (i.e. the date when a resident became a long-stay resident), defined as a dichotomous variable indicating whether a resident experienced any hospitalization during NH stay. This variable was jointly determined based on the MDS 3.0 and MedPAR data.

The main independent variables of interest included the diagnosis of ADRD (based on checkboxes of Alzheimer’s disease and dementia and the International Classification of Diseases [ICD]-9 codes in the MDS 3.0), an indicator of the launch of the National Partnership (i.e. after July 2012 versus before March 2012) at the time when a resident entered long-stay status, and an interaction term between these two variables. The indicator of ADRD captures the differences in hospitalizations between residents with ADRD versus those without at the baseline. The indicator of the National Partnership captures the overall changes in hospitalizations before and after the launch of the National Partnership. The interaction term captures the additional changes in hospitalizations among residents with ADRD after the launch of the National Partnership.

We controlled for a comprehensive set of individual characteristics that are known to be associated with the risk of hospitalizations,28,29 such as socio-demographic characteristics (e.g. age, gender, race, Medicaid coverage), functional status (Activities of Daily Living [ADL], 30 ranging from 0 to 28, with 0 indicating total independency and 28 indicating total dependency), cognitive status (Cognitive Function Scale [CFS],31 a 4-category scale with 1 indicating cognitively intact and 4 indicating severely impaired), aggressive behavior (based on Aggressive Behavior Scale [ABS],32 a 4-category scale measuring individual aggressive behavior with 1 for none and 4 for very severe), as well as the diagnoses of selected conditions28,29 (e.g. diabetes, heart failure, full list of conditions is shown in Table 1). All these variables were extracted from the MDS assessment closest to the baseline date (i.e. when a resident became a long stay resident).

ANALYSIS

We first examined the trend in hospitalizations as well as residents’ characteristics before and after the launch of the National Partnership among long-stay NH residents with and without ADRD to assess whether there were changes in resident case-mix that may have affected hospitalization risks. We used linear probability models with NH fixed-effects and robust standard errors to explore the relationship between the launch of the National Partnership and risks of hospitalization among long-stay NH residents with ADRD, accounting for individual socio-demographic status and health conditions. We accounted for changes in hospitalizations that may be due to other factors unrelated to the illness (e.g. non-ADRD specific policies or market characteristics) by adjusting for changes in hospitalizations among non-ADRD residents. We also included facility fixed-effects to account for time-invariant facility characteristics (e.g. staffing) that may affect the overall quality of care for both residents with and without ADRD.

We further stratified NHs based on the prevalence of antipsychotic use prior the launch of the National Partnership. Specifically, we obtained the NH-level rates of antipsychotic use among long-stay residents from the NHC website between the second quarter of 2011 and the first quarter of 2012, and considered a NH as having high- or low-antipsychotic use if the average prevalence of antipsychotics was in the top 25th or bottom 25th percentile of the distribution. The average baseline rate of antipsychotic use was 37.6% in NHs in the highest quartile and was 11.9% in NHs in the lowest quartile. We then repeated the analysis in these two subgroups of NHs separately. Furthermore, we compared facility quality, measured by CMS’s overall star rating and staffing star rating, between NHs with high- versus low-antipsychotic use at the baseline, to explore potential reasons for the different relationships, if any, between the National Partnership and hospitalizations in these two subgroups of NHs.

To check the robustness of our findings, we also performed a sensitivity analysis by further restricting the pre-Partnership cohort to those who became NH long-stayers before January 1st 2012 so that both the baseline time and follow-up period were before the “complete” initiation of the National Partnership (i.e. July 2012).

RESULTS

The overall prevalence of ADRD among 565,885 identified long-stay NH residents was 58.5%. The overall all-cause hospitalization rates decreased after the launch of the National Partnership. The decrease in hospitalizations was 0.8 percentage points greater for non-ADRD residents than for ADRD (P<0.01, Table 1). Compared with those without ADRD, residents with ADRD were older, had greater physical and cognitive impairment, and higher prevalence of aggressive behaviors and mental conditions (anxiety and depression), but had lower prevalence of most other medical conditions. While there were variations in resident characteristics before and after the launch of the National Partnership, there was no systematic change in the case-mix of residents’ characteristics. For example, residents with ADRD appeared to be slightly less likely to have severe aggressive behaviors (i.e. 8.7% having severe or very severe aggressive behavior in pre-Partnership period and 7.9% in post-Partnership period), but were slightly more functionally impaired (ADL score 16.00 versus 16.34) in the post-Partnership period.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for long-stay NH residents with and without ADRD, before and after the launch of the National Partnership

| Variable | ADRD | Non-ADRD | Difference in pre-post changes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pre | post | Change+ | pre | post | Change | ||

| (n=87,827) | (n=243,293) | (n=57,507) | (n=177,258) | ||||

| All-cause NH originated hospitalization | 18.7% | 17.5% | −1.2%*** | 22.3% | 20.3% | −2.0%*** | 0.8%*** |

| Socio-demographics | |||||||

| Age | 84.62 | 84.57 | −0.05 | 82.85 | 82.53 | −0.32*** | 0.27*** |

| Male | 30.1% | 31.0% | 0.9%*** | 33.2% | 35.0% | 1.8%*** | −0.9%*** |

| Race | *** | *** | |||||

| white | 83.8% | 83.5% | −0.3% | 83.3% | 82.8% | −0.5% | −0.1% |

| black | 8.4% | 8.4% | 0.0% | 8.8% | 8.9% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

| other | 7.8% | 8.1% | 0.3% | 7.9% | 8.3% | 0.4% | 0.1% |

| Medicare-Medicaid dual status | 43.5% | 42.7% | −0.8%*** | 45.6% | 43.5% | −2.1%*** | 1.3%*** |

| Post-acute care | 55.5% | 56.9% | 1.3%*** | 65.1% | 67.8% | 2.8%*** | −1.5%*** |

| Functional Status | |||||||

| ADL | 16.00 | 16.34 | 0.34*** | 15.13 | 15.51 | 0.39*** | −0.05 |

| CFS | *** | *** | ** | ||||

| Intact | 12.0% | 12.3% | 0.3% | 50.4% | 51.9% | 1.5% | −1.2% |

| Mild | 23.1% | 23.3% | 0.2% | 28.8% | 27.7% | −1.0% | 1.1% |

| Moderate | 52.5% | 52.2% | −0.3% | 18.0% | 17.4% | −0.7% | 0.3% |

| Severe | 12.4% | 12.2% | −0.2% | 2.8% | 3.0% | 0.2% | −0.2% |

| ABS category | *** | *** | *** | ||||

| None | 76.8% | 77.5% | 0.7% | 90.5% | 90.7% | −0.2% | 0.7% |

| Moderate | 14.5% | 14.6% | 0.1% | 7.4% | 7.2% | 0.2% | −0.1% |

| Severe | 6.6% | 6.2% | −0.4% | 1.8% | 1.8% | 0.0% | −0.2% |

| Very severe | 2.1% | 1.7% | −0.4% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.0% | −0.3% |

| Major Diagnoses | |||||||

| Hypertension | 78.1% | 78.9% | 0.8%*** | 81.9% | 82.7% | 0.7%*** | 0.1% |

| Diabetes | 25.9% | 26.1% | 0.3% | 34.6% | 34.9% | 0.3% | 0.0% |

| Heart failure | 18.9% | 18.4% | −0.5%*** | 27.9% | 27.0% | −0.9%*** | 0.4% |

| CAD | 23.1% | 23.3% | 0.1% | 26.0% | 25.5% | −0.5%** | 0.6%** |

| PVD | 5.5% | 7.8% | 2.3%*** | 8.0% | 10.4% | 2.4%*** | −0.1% |

| Asthma/COPD | 17.5% | 17.4% | −0.1% | 25.3% | 25.4% | 0.05% | −0.2% |

| Stroke | 16.0% | 15.4% | −0.7%*** | 21.9% | 20.6% | −1.3%*** | 0.6%** |

| Anxiety | 28.3% | 30.7% | 2.4%*** | 23.3% | 24.4% | 1.1%*** | 1.3%*** |

| Depression | 48.3% | 47.8% | −0.5%*** | 41.8% | 40.8% | −1.0%*** | 0.5% |

| UTI | 29.1% | 26.6% | −2.5%*** | 29.1% | 26.7% | −2.4%*** | −0.1% |

| Septicemia | 1.3% | 1.5% | 0.2%*** | 1.7% | 2.0% | 0.3%*** | −0.1% |

| Pneumonia | 9.9% | 9.9% | 0.05% | 12.4% | 12.8% | 0.3%** | −0.2% |

| Dehydration | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.03%** | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.04%** | −0.0% |

p<0.05

p<0.01

NOTE: NH (nursing home); ADL (activities of daily living); CFS (cognitive function scale); ABS (aggressive behavior scale); CAD (Coronary artery disease); PVD (Peripheral Vascular Disease); COPD (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), UTI (urinary tract infection)

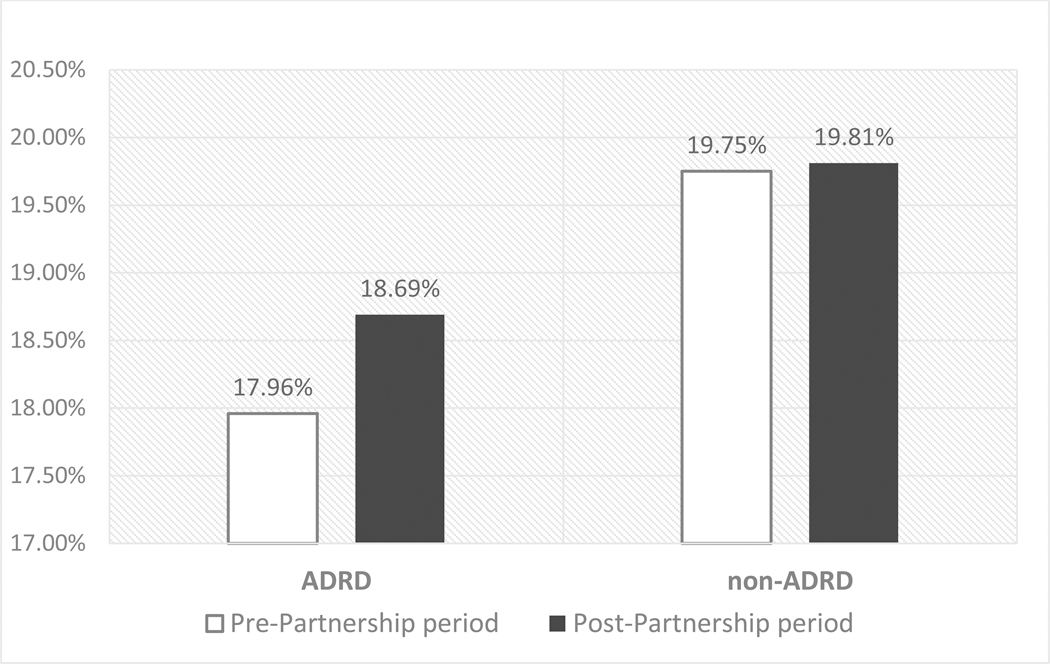

Table 2 displays the findings from the main analysis (for all NHs, linear probability model with facility fixed-effects and robust standard errors) and stratified analysis (for NHs with high/low antipsychotic use), accounting for all other individual-level covariates and the concurrent trend in hospitalizations among non-ADRD residents. In general, residents with ADRD had a lower risk of hospitalization than non-ADRD residents. For example, at baseline, ADRD residents had 1.8 percentage-point lower likelihood of hospitalization (Coefficient: 0.0179, p<0.01), compared to residents without ADRD. After accounting for individual characteristics and facility fixed-effects, however, we detected a 0.7 percentage-point increase (Coefficient:0.00673, p<0.01) in the risk of hospitalizations among residents with ADRD in relation to non-ADRD residents in the post-Partnership period. Figure 1 presents risk-adjusted hospitalization rates for ADRD and non-ADRD residents respectively, before and after the launch of the National Partnership. The risk-adjusted hospitalization risks increased 0.7 percentage-point in the post-Partnership period among residents with ADRD, whereas among those without ADRD the rate remained the same.

Table 2.

Association between the National Partnership and risks of hospitalizations, for residents from all NHs and for residents from NHs with highest/lowest baseline antipsychotic use, after adjusting for individual covariates

| All NHs | NHs with highest antipsychotic% | NHs with lowest antipsychotic% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (n=565,885) | (n=120,605) | (n=140,952) | |

| ADRD | −0.0179*** | −0.0224*** | −0.0159*** |

| (−0.0224 – −0.0134) | (−0.0327 – −0.0121) | (−0.0246 – −0.00721) | |

| Post-Partnership | 0.000561 | −0.00412 | −0.00137 |

| (−0.00529 – 0.00641) | (−0.0177 – 0.00945) | (−0.0128 – 0.0101) | |

| ADRD * post-Partnership | 0.00673*** | 0.0121** | 0.00596 |

| (0.00181 – 0.0116) | (0.000707 – 0.0234) | (−0.00350 – 0.0154) |

p<0.05

p<0.01

95% confidence interval in parentheses

Figure 1.

Adjusted risk of all-cause hospitalization by prevalence of ADRD

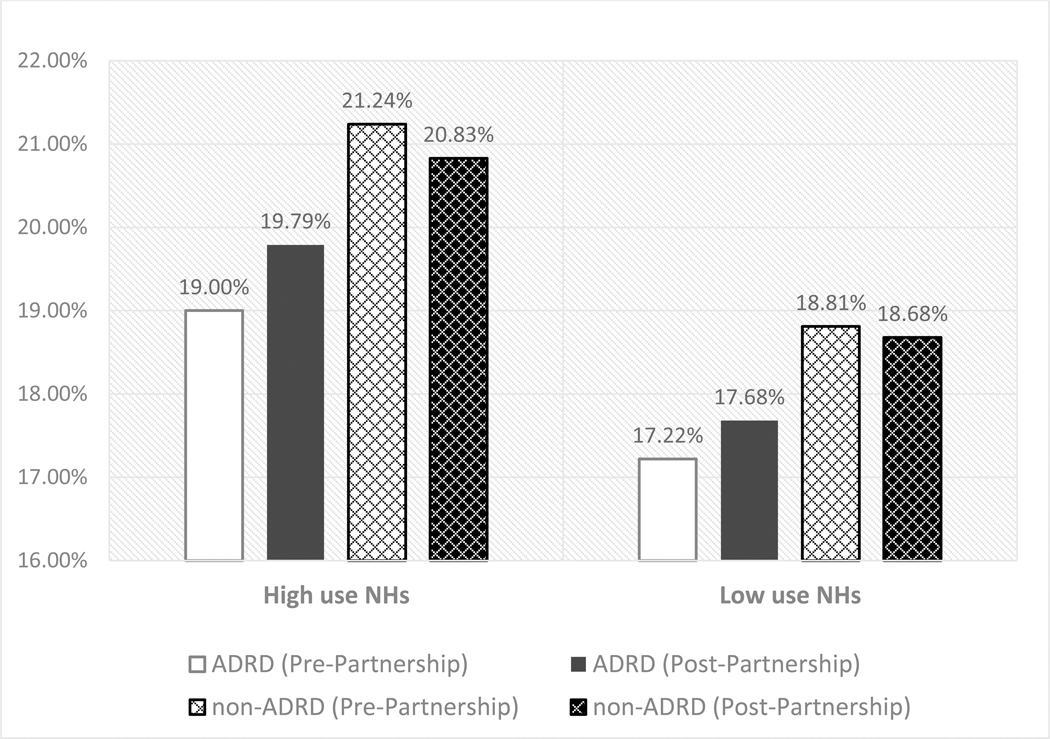

We then performed stratified analyses in NHs with the highest and lowest baseline antipsychotic use (i.e. average of 37.6% versus 11.9% of long-stay residents prescribed antipsychotics). The findings from these analyses (Table 2 last two columns) suggested that residents with ADRD experienced a higher risk of hospitalizations, compared to non-ADRD residents, in NHs with high prevalence of antipsychotic use after the launch of the National Partnership, but not in NHs with low antipsychotic use. To facilitate the interpretation of the findings, we present the risk-adjusted hospitalization rates for ADRD and non-ADRD residents before and after the launch of the National-Partnership, stratified by NH use of antipsychotics, in Figure 2. As illustrated in Figure 2, there was small decreases in the likelihood of hospitalizations among non-ADRD residents in both high and low-antipsychotic use NHs (0.4 percentage-point and 0.1 percentage-point decrease in the probability of hospitalizations). In contrast, the probability of hospitalizations increased 0.8 percentage-point among residents with ADRD in NHs with high-antipsychotic use and 0.5 percentage-point in low-use NHs. Therefore, the relative change for ADRD residents in the probability of hospitalizations increased 1.2 percentage-point (p-value=0.037) in high-antipsychotic use NHs and was statistically insignificant in low-antipsychotic use NHs (0.6 percentage-point, p-value=0.22).

Figure 2.

Adjusted risk of all-cause hospitalization for ADRD and non-ADRD NH residents by high/low facility antipsychotic prevalence

The findings from the comparison of staffing and overall star ratings between NHs with high and low antipsychotic use suggest that NHs with high antipsychotic rates were more likely to have 1 or 2-star rating for staffing and overall quality (39% and 44% respectively), compared to NHs with low antipsychotic use (25% and 31% respectively, Appendix table 1). Findings from the sensitivity analysis with more restricted pre-Partnership cohort definition were consistent with the main findings (Appendix table 3).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we examined the relationship between the National Partnership and hospitalizations among NH long-stay residents, specifically those with ADRD. We found that although long-stay residents with ADRD were generally less likely to be hospitalized than non-ADRD residents, there was an increased risk in hospitalizations among ADRD residents relative to non-ADRD residents after the initiation of the National Partnership. This relationship was more pronounced in NHs with a higher prevalence of antipsychotic use at the baseline.

The reduction in antipsychotic use after the National Partnership has been a welcoming change and seems to have achieved CMS’ objectives.20,26,27 However, concerns have been raised that the National Partnership may have inadvertently and negatively impacted outcomes of residents with ADRD.33–35 Our finding that NH residents with ADRD experienced an increased risk of hospitalization after the National Partnership appears to support these concerns. Although our study is not able to identify the specific reasons for this increase in risk following the implementation of the National Partnership, it may be naïve to assume that less use of antipsychotics alone is likely to assure adequate provision of dementia care. When antipsychotic use is reduced, NHs still need to manage difficult behaviors, which potentially increase the caregiving burden. To provide appropriate dementia care while reducing antipsychotics, NHs may need to focus on non-pharmacological approaches, such as offering behavioral therapy and reality orientation. They may also need to improve facility infrastructure for dementia care, such as environmental modifications to accommodate wandering and reduce confusion or perhaps implement Alzheimer’s special care units, which is associated with reduced risks of potentially avoidable hospitalization among NH residents with ADRD.36–38 Such appoaches, however, would require additional investments in infrastructure and staffing, neither one of which are easily accomplished in this care setting. We do not know to what extent, if any, NHs may have adopted these approaches to reduce reliance on antipsychotics. Reducing antipsychotic use among ADRD residents, without providing alternative means for dealing with difficult behavioral symptoms, may lead to unintended consequences including increased hospitalization risk.6,7 For example, in order to reduce the use of antipsychotics, NHs may be motivated to transfer a resident to a hospital even for conditions that may otherwise be preventable or manageable within a facility, particularly if these conditions are accompanied by difficult behavioral symptoms.8

Given the large and growing population of residents with ADRD, the delivery of high quality dementia care is a critical issue for NHs. It is not, however, clear how NHs can be motivated to do so effectively. Public reporting of quality measures has been widely used to promote care quality.39 In fact, under the National Partnership, CMS started to publish the rates of antipsychotic use in NHs on their NHC website, which may have motivated NHs to reduce the prevalence of antipsychotics. However, adding quality measures for care process (antipsychotic use prevalence) without also adding appropriate outcomes measures for dementia care may not translate into better health outcomes for residents with ADRD.

Making significant improvements in dementia care may be challenging for NHs, especially for the many that are resource poor. Our findings suggest that the National Partnership particularly impacted hospitalizations in NHs with high prevalence of antipsychotic use at baseline. As suggested by our findings, these NHs are more likely to have lower staffing and worse quality, compared to NHs with lower antipsychotic use. Antipsychotics, which are also known as “chemical restraints”, are known to be employed to reduce caregiving burden when staffing ratios may be inadequate.40,41 Thus, NHs with high prevalence of antipsychotic use may have had fewer resources and thus were less likely to adopt non-pharmacological patient-centered interventions to manage ADRD-related behavioral problems. Recognizing the added burden in caring for residents with behavioral disorders, some states provide additional reimbursement to NHs for these individuals.42 Future studies may wish to examine how these add-on policies may impact on NHs’ ability to provide high quality dementia care while reducing antipsychotic use.

This study had several limitations. First, because the National Partnership was implemented nationwide, there were no natural “comparison” facilities that were not subject to this policy change. Although we have accounted for the changes in hospitalizations among NH residents without ADRD so that concurrent changes due to non-ADRD specific polices were to some extent adjusted for, there could be other uncaptured concurrent changes in dementia care. This, however, is somewhat mitigated by the fact that we did not detect systematic changes in observed individual health conditions before and after the launch of the National Partnership among ADRD and non-ADRD residents. Furthermore, if the National Partnership had a spillover effect among non-ADRD residents, the differences in outcomes between ADRD and non-ADRD residents could be underestimated. Second, the National Partnership included multi-dimensional interventions, and they may have different impacts on dementia care in NHs. However, we were not able to differentiate the impact of each component of the National Partnership that may have contributed to the change in health outcomes among NH residents with ADRD. Third, the diagnosis of dementia is based on the MDS assessment. There is a possibility that the diagnosis of dementia in the MDS in underreported or inaccurate. However, such a misspecification, should it exist, is not likely to have systematically changed from before to after the National Partnership. Fourth, although this study did not determine whether or not higher rates of hospitalizations among ADRD residents were necessary, hospitalizations among NH long-stay residents are known to be traumatic, costly, and are often potentially avoidable.43 Lastly, our findings for long-stay NH residents may not be generalizable to other NH residents, i.e. those receiving post-acute care in skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). Because of their unique health conditions, care needs, and care goals, the National Partnership may have affected post-acute SNF residents differently.

CONCLUSIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

Although the prevalence of antipsychotic use in NHs has declined following the National Partnership, we found an increase in the risks of hospitalizations among residents with ADRD, especially in NHs with the high prevalence of antipsychotic use prior to the launch of the National Partnership. Our results suggest that a reduction in NH antipsychotic use may be a necessary but not a sufficient condition for improving health outcomes among residents with ADRD. More research is needed to understand the impact of this legislative intervention on health outcomes in order to improve care quality in this vulnerable population.

Acknowledgments

This study has been funded by the National Institute on Aging Grant R01AG052451. The sponsors had no role in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collections, analysis, and preparation of the article.

Appendix

Appendix table 1.

Overall rating and staffing rating for high- or low-antipsychotic use nursing homes

| NHs with highest antipsychotic% | NHs with lowest antipsychotic% | |

|---|---|---|

| N=3,424 | N=3,420 | |

| Overall rating | ||

| 5-star | 10.7% | 17.4% |

| 4-star | 24.5% | 29.0% |

| 3-star | 20.8% | 21.8% |

| 2-star | 23.1% | 17.5% |

| 1-star | 20.4% | 13.7% |

| Staff rating | ||

| 5-star | 3.4% | 7.7% |

| 4-star | 33.0% | 43.5% |

| 3-star | 22.6% | 21.4% |

| 2-star | 19.5% | 16.1% |

| 1-star | 19.4% | 9.3% |

Note: Percentages do not add up to 100% because star ratings are unavailable for a small amount of NHs. For those with available overall and staff ratings, earliest rating during the study period was used.

Appendix table 2.

Main findings, linear probability models with facility fixed-effect and robust standard error

| VARIABLES | Full model | Full model: NHs with highest antipsychotic use | Full model: NHs with highest antipsychotic use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADRD | −0.0179*** | −0.0224*** | −0.0159*** |

| (−0.0224 – −0.0134) | (−0.0327 – −0.0121) | (−0.0246 – −0.00721) | |

| Post | 0.000561 | −0.00412 | −0.00137 |

| (−0.00529 – 0.00641) | (−0.0177 – 0.00945) | (−0.0128 – 0.0101) | |

| ADRD*Post | 0.00673*** | 0.0121** | 0.00596 |

| (0.00181 – 0.0116) | (0.000707 – 0.0234) | (−0.00350 – 0.0154) | |

| Age | −0.000102 | 0.000301* | −0.000589*** |

| (−0.000246 – 4.23e-05) | (−1.21e-05 – 0.000615) | (−0.000871 – −0.000308) | |

| Male | 0.0273*** | 0.0220*** | 0.0258*** |

| (0.0249 – 0.0296) | (0.0169 – 0.0271) | (0.0211 – 0.0304) | |

| Race: black | 0.0173*** | 0.0122** | 0.0218*** |

| (0.0125 – 0.0221) | (0.00266 – 0.0217) | (0.0118 – 0.0318) | |

| Race: other | 0.00306 | 0.00987* | 0.000727 |

| (−0.00164 – 0.00775) | (−0.000126 – 0.0199) | (−0.00846 – 0.00992) | |

| Dual status | 0.0175*** | 0.0136*** | 0.0197*** |

| (0.0152 – 0.0199) | (0.00849 – 0.0186) | (0.0149 – 0.0245) | |

| Post-acute care | 0.0261*** | 0.0219*** | 0.0253*** |

| (0.0237 – 0.0285) | (0.0167 – 0.0272) | (0.0204 – 0.0302) | |

| ADL | 0.00187*** | 0.00218*** | 0.00168*** |

| (0.00168 – 0.00206) | (0.00179 – 0.00258) | (0.00130 – 0.00205) | |

| CFS: mildly impaired | −0.00137 | −0.00409 | 0.000442 |

| (−0.00440 – 0.00166) | (−0.0111 – 0.00290) | (−0.00528 – 0.00616) | |

| CFS: moderately impaired | −0.00833*** | −0.00644* | −0.00607** |

| (−0.0114 – −0.00525) | (−0.0135 – 0.000624) | (−0.0120 – −0.000175) | |

| CFS: severely impaired | −0.00972*** | −0.00697 | −0.00918* |

| (−0.0144 – −0.00501) | (−0.0173 – 0.00336) | (−0.0184 – 5.68e-05) | |

| ABS: moderate | 0.0105*** | 0.0110*** | 0.00410 |

| (0.00720 – 0.0138) | (0.00408 – 0.0179) | (−0.00265 – 0.0109) | |

| ABS: severe | 0.0122*** | 0.0127** | 0.00312 |

| (0.00706 – 0.0173) | (0.00248 – 0.0229) | (−0.00754 – 0.0138) | |

| ABS: very severe | 0.0221*** | 0.0251*** | 0.0313*** |

| (0.0125 – 0.0318) | (0.00800 – 0.0421) | (0.00870 – 0.0539) | |

| Hypertension | 0.0145*** | 0.0176*** | 0.0125*** |

| (0.0120 – 0.0170) | (0.0121 – 0.0231) | (0.00751 – 0.0175) | |

| Diabetes | 0.0307*** | 0.0315*** | 0.0298*** |

| (0.0283 – 0.0332) | (0.0263 – 0.0367) | (0.0250 – 0.0346) | |

| Heart failure | 0.0421*** | 0.0464*** | 0.0426*** |

| (0.0393 – 0.0448) | (0.0401 – 0.0527) | (0.0373 – 0.0479) | |

| CAD | 0.0155*** | 0.0164*** | 0.0148*** |

| (0.0129 – 0.0180) | (0.0107 – 0.0222) | (0.00974 – 0.0199) | |

| PVD | 0.0230*** | 0.0306*** | 0.0233*** |

| (0.0189 – 0.0270) | (0.0216 – 0.0397) | (0.0152 – 0.0314) | |

| Asthma/COPD | 0.0372*** | 0.0405*** | 0.0365*** |

| (0.0344 – 0.0400) | (0.0344 – 0.0466) | (0.0309 – 0.0422) | |

| Stroke | 0.00234 | 0.00542* | 0.000507 |

| (−0.000510 – 0.00520) | (−0.000985 – 0.0118) | (−0.00504 – 0.00606) | |

| Anxiety | 0.00407*** | 0.0104*** | 0.00316 |

| (0.00165 – 0.00650) | (0.00518 – 0.0155) | (−0.00170 – 0.00803) | |

| Depression | 0.00528*** | 0.00401 | 0.00440* |

| (0.00309 – 0.00747) | (−0.000828 – 0.00885) | (−5.67e-05 – 0.00886) | |

| UTI | 0.0227*** | 0.0252*** | 0.0212*** |

| (0.0203 – 0.0252) | (0.0196 – 0.0308) | (0.0163 – 0.0261) | |

| Septicemia | 0.0343*** | 0.0360*** | 0.0283*** |

| (0.0252 – 0.0434) | (0.0149 – 0.0571) | (0.0109 – 0.0457) | |

| Pneumonia | 0.0372*** | 0.0353*** | 0.0308*** |

| (0.0335 – 0.0409) | (0.0271 – 0.0436) | (0.0238 – 0.0379) | |

| Dehydration | 0.000133 | 0.0101 | 0.00384 |

| (−0.0258 – 0.0261) | (−0.0493 – 0.0694) | (−0.0492 – 0.0569) | |

| Year = 2012 | −0.0107*** | −0.00894 | −0.00920* |

| (−0.0154 – −0.00599) | (−0.0197 – 0.00178) | (−0.0185 – 9.40e-05) | |

| Year = 2013 | −0.0281*** | −0.0256*** | −0.0246*** |

| (−0.0341 – −0.0221) | (−0.0389 – −0.0123) | (−0.0363 – −0.0128) | |

| Year = 2014 | −0.0243*** | −0.0222*** | −0.0237*** |

| (−0.0303 – −0.0183) | (−0.0356 – −0.00875) | (−0.0356 – −0.0118) | |

| Year = 2015 | −0.0313*** | −0.0334*** | −0.0295*** |

| (−0.0376 – −0.0250) | (−0.0473 – −0.0195) | (−0.0419 – −0.0171) | |

| Constant | 0.105*** | 0.0798*** | 0.141*** |

| (0.0919 – 0.118) | (0.0513 – 0.108) | (0.115 – 0.167) | |

| Observations | 565,885 | 120,605 | 140,952 |

| R-squared | 0.018 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| Number of SNF | 13,770 | 3,424 | 3,420 |

95% confidence interval in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

NOTE: ADRD (Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia); ADL (activities of daily living); CFS (cognitive function scale); ABS (aggressive behavior scale); CAD (Coronary artery disease); PVD (Peripheral Vascular Disease); COPD (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), UTI (urinary tract infection)

Appendix table 3.

Models excluding people becoming NH long-stayers in 2012Q1, with facility fixed-effect and robust standard error

| VARIABLES | Full model | Full model: NHs with highest antipsychotic use | Full model: NHs with highest antipsychotic use |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADRD | −0.0189*** | −0.0276*** | −0.0155*** |

| (−0.0240 - −0.0138) | (−0.0394 - −0.0158) | (−0.0252 - −0.00574) | |

| Post | −0.0106*** | −0.0168*** | −0.0102** |

| (−0.0157 - −0.00553) | (−0.0288 - −0.00481) | (−0.0198 - −0.000641) | |

| ADRD*Post | 0.00760*** | 0.0176*** | 0.00570 |

| (0.00213 – 0.0131) | (0.00493 – 0.0304) | (−0.00463 – 0.0160) | |

| Age | −8.38e-05 | 0.000317* | −0.000571*** |

| (−0.000232 – 6.41e-05) | (−3.73e-06 – 0.000638) | (−0.000859 - −0.000283) | |

| Male | 0.0268*** | 0.0223*** | 0.0249*** |

| (0.0243 – 0.0292) | (0.0171 – 0.0275) | (0.0201 – 0.0298) | |

| Race: black | 0.0176*** | 0.0119** | 0.0217*** |

| (0.0127 – 0.0225) | (0.00224 – 0.0215) | (0.0113 – 0.0320) | |

| Race: other | 0.00394 | 0.0106** | 0.00163 |

| (−0.000904 – 0.00879) | (0.000366 – 0.0209) | (−0.00793 – 0.0112) | |

| Dual status | 0.0180*** | 0.0143*** | 0.0200*** |

| (0.0156 – 0.0204) | (0.00903 – 0.0195) | (0.0150 – 0.0249) | |

| Post-acute care | 0.0269*** | 0.0220*** | 0.0260*** |

| (0.0245 – 0.0294) | (0.0166 – 0.0275) | (0.0209 – 0.0310) | |

| ADL | 0.00187*** | 0.00214*** | 0.00174*** |

| (0.00167 – 0.00206) | (0.00173 – 0.00255) | (0.00135 – 0.00213) | |

| CFS: mildly impaired | −0.00158 | −0.00518 | −0.000268 |

| (−0.00470 – 0.00154) | (−0.0124 – 0.00203) | (−0.00613 – 0.00559) | |

| CFS: moderately impaired | −0.00791*** | −0.00640* | −0.00674** |

| (−0.0111 - −0.00473) | (−0.0137 – 0.000863) | (−0.0128 - −0.000650) | |

| CFS: severely impaired | −0.00863*** | −0.00681 | −0.00842* |

| (−0.0135 - −0.00374) | (−0.0174 – 0.00378) | (−0.0181 – 0.00125) | |

| ABS: moderate | 0.0103*** | 0.0110*** | 0.00468 |

| (0.00693 – 0.0137) | (0.00384 – 0.0181) | (−0.00229 – 0.0117) | |

| ABS: severe | 0.0114*** | 0.0122** | 0.00287 |

| (0.00614 – 0.0167) | (0.00162 – 0.0227) | (−0.00805 – 0.0138) | |

| ABS: very severe | 0.0208*** | 0.0255*** | 0.0262** |

| (0.0107 – 0.0309) | (0.00746 – 0.0435) | (0.00243 – 0.0501) | |

| Hypertension | 0.0145*** | 0.0188*** | 0.0126*** |

| (0.0119 – 0.0172) | (0.0131 – 0.0246) | (0.00744 – 0.0178) | |

| Diabetes | 0.0312*** | 0.0319*** | 0.0299*** |

| (0.0287 – 0.0337) | (0.0265 – 0.0373) | (0.0250 – 0.0348) | |

| Heart failure | 0.0413*** | 0.0461*** | 0.0422*** |

| (0.0385 – 0.0441) | (0.0397 – 0.0525) | (0.0367 – 0.0477) | |

| CAD | 0.0160*** | 0.0170*** | 0.0144*** |

| (0.0133 – 0.0186) | (0.0110 – 0.0230) | (0.00909 – 0.0196) | |

| PVD | 0.0226*** | 0.0304*** | 0.0225*** |

| (0.0184 – 0.0268) | (0.0211 – 0.0398) | (0.0142 – 0.0309) | |

| Asthma/COPD | 0.0366*** | 0.0407*** | 0.0364*** |

| (0.0337 – 0.0394) | (0.0344 – 0.0469) | (0.0306 – 0.0422) | |

| Stroke | 0.00194 | 0.00621* | 0.000402 |

| (−0.00101 – 0.00489) | (−0.000395 – 0.0128) | (−0.00538 – 0.00618) | |

| Anxiety | 0.00385*** | 0.00902*** | 0.00256 |

| (0.00136 – 0.00634) | (0.00372 – 0.0143) | (−0.00243 – 0.00755) | |

| Depression | 0.00534*** | 0.00420 | 0.00454* |

| (0.00308 – 0.00760) | (−0.000815 – 0.00921) | (−4.35e-05 – 0.00913) | |

| UTI | 0.0227*** | 0.0264*** | 0.0196*** |

| (0.0201 – 0.0252) | (0.0206 – 0.0323) | (0.0146 – 0.0246) | |

| Septicemia | 0.0364*** | 0.0370*** | 0.0302*** |

| (0.0270 – 0.0458) | (0.0150 – 0.0590) | (0.0122 – 0.0481) | |

| Pneumonia | 0.0363*** | 0.0331*** | 0.0298*** |

| (0.0326 – 0.0401) | (0.0246 – 0.0417) | (0.0226 – 0.0370) | |

| Dehydration | 0.00147 | 0.0176 | 0.00453 |

| (−0.0253 – 0.0282) | (−0.0439 – 0.0791) | (−0.0512 – 0.0602) | |

| Year = 2013 | −0.0175*** | −0.0167*** | −0.0156*** |

| (−0.0210 – −0.0140) | (−0.0245 – −0.00886) | (−0.0225 – −0.00868) | |

| Year = 2014 | −0.0137*** | −0.0133*** | −0.0147*** |

| (−0.0173 – −0.0101) | (−0.0213 – −0.00532) | (−0.0218 – −0.00763) | |

| Year = 2015 | −0.0207*** | −0.0246*** | −0.0206*** |

| (−0.0249 – −0.0166) | (−0.0335 – −0.0157) | (−0.0288 – −0.0125) | |

| Constant | 0.104*** | 0.0814*** | 0.139*** |

| (0.0902 – 0.117) | (0.0522 – 0.111) | (0.113 – 0.166) | |

| Observations | 530,911 | 113,293 | 132,307 |

| R-squared | 0.017 | 0.018 | 0.017 |

| Number of SNF | 13,766 | 3,421 | 3,419 |

95% confidence interval in parentheses

p<0.01

p<0.05

p<0.1

NOTE: ADRD (Alzheimer’s disease and related dementia); ADL (activities of daily living); CFS (cognitive function scale); ABS (aggressive behavior scale); CAD (Coronary artery disease); PVD (Peripheral Vascular Disease); COPD (Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), UTI (urinary tract infection)

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference

- 1.CMS. MDS 3.0 Frequency Report. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-andSystems/Computer-Data-and-Systems/Minimum-Data-Set-3-0-Public-Reports/Minimum-DataSet-3-0-frequency-report.html. Published 2018. Accessed March 26, 2020.

- 2.HHS. Long-Term Care Providers and Services Users in the United States: Data from the National Study of Long-Term Care Providers, 2013–2014. CDC; https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_03/sr03_038.pdf. Published 2016. Accessed May 20, 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sink KM, Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, Yaffe K. Ethnic differences in the prevalence and pattern of dementia‐related behaviors. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52(8):1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cen X, Li Y, Hasselberg M, Caprio T, Conwell Y, Temkin-Greener H. Aggressive behaviors among Nursing home residents: Association with dementia and behavioral health disorders. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2018;19(12):1104–1109. e1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alzheimer’s Society. Optimising treatment and care for people with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-08/Optimising%20treatment%20and%20care%20-%20best%20practice%20guide.pdf?downloadID=609. Published 2011. Accessed May 8th, 2019.

- 6.Aud MA. Dangerous wandering: elopements of older adults with dementia from long-term care facilities. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease & Other Dementias®. 2004;19(6):361–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hersch EC, Falzgraf S. Management of the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging. 2007;2(4):611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Temkin-Greener H, Cen X, Hasselberg MJ, Li Y. Preventable Hospitalizations Among Nursing Home Residents With Dementia and Behavioral Health Disorders. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2019;20(10):1280-+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Muramatsu RS, Goebert D. Psychiatric services: Experience, perceptions, and needs of nursing facility multidisciplinary leaders. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2011;59(1):120–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Briesacher BA, Limcangco MR, Simoni-Wastila L, et al. The quality of antipsychotic drug prescribing in nursing homes. Archives of internal medicine. 2005;165(11):1280–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Briesacher BA, Tjia J, Field T, Peterson D, Gurwitz JH. Antipsychotic Use Among Nursing Home Residents. JAMA. 2013;309(5):440–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee PE, Gill SS, Freedman M, Bronskill SE, Hillmer MP, Rochon PA. Atypical antipsychotic drugs in the treatment of behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia: systematic review. Bmj. 2004;329(7457):75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kate NS, Pawar SS, Parkar SR, Sawant NS. Adverse drug reactions due to antipsychotics and sedative-hypnotics in the elderly. Journal of Geriatric Mental Health. 2015;2(1):16. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rochon PA, Normand S-L, Gomes T, et al. Antipsychotic therapy and short-term serious events in older adults with dementia. Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168(10):1090–1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liperoti R, Gambassi G, Lapane KL, et al. Conventional and atypical antipsychotics and the risk of hospitalization for ventricular arrhythmias or cardiac arrest. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2005;165(6):696–701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pratt NL, Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Salter A, Ryan P. Risk of hospitalization for hip fracture and pneumonia associated with antipsychotic prescribing in the elderly. Drug safety. 2011;34(7):567–575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pratt NL, Roughead EE, Ramsay E, Salter A, Ryan P. Risk of hospitalization for stroke associated with antipsychotic use in the elderly. Drugs & aging. 2010;27(11):885–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.FDA. FDA Public Health Advisory: Deaths with Antipsychotics in Elderly Patients with Behavioral Disturbances. http://psychrights.org/drugs/FDAatypicalswarning4elderly.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed July 5, 2018.

- 19.Ricci J, Coulen C, Berger JE, Moore MC, McQueen A, Jan SA. Prescriber compliance with black box warnings in older adult patients. The American journal of managed care. 2009;15(11):e103–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lucas JA, Bowblis JR. CMS strategies to reduce antipsychotic drug use in nursing home patients with dementia show some progress. Health Affairs. 2017;36(7):1299–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Government Accountability Office. Report to Congressional Requesters: Antipsychotic drug use. https://www.gao.gov/assets/670/668221.pdf. Published 2015. Updated Jan. Accessed June 29, 2018.

- 22.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS Announces Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes. CMS.gov; https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/cms-announces-partnership-improve-dementia-care-nursing-homes. Published 2012. Updated May 30, 2012. Accessed Jan 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Data show National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care achieves goals to reduce unnecessary antipsychotic medications in nursing homes. CMS.gov; https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/data-show-national-partnership-improve-dementia-care-achieves-goals-reduce-unnecessary-antipsychotic. Published 2017. Updated Oct 2, 2017. Accessed Jan 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care exceeds goal to reduce use of antipsychotic medications in nursing homes: CMS announces new goal. CMS.gov; https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/press-releases/national-partnership-improvedementia-care-exceeds-goal-reduce-use-antipsychotic-medications-nursing. Published 2014. Updated Sep 19, 2014. Accessed Jan 8, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care in Nursing Homes: Antipsychotic Medication Use Data Report (October 2018). https://www.nhqualitycampaign.org/files/Antipsychotic_Medication_Use_Report.pdf. Published 2018. Updated Oct 2018. Accessed Jan 8, 2019.

- 26.Gurwitz JH, Bonner A, Berwick DM. Reducing excessive use of antipsychotic agents in nursing homes. Jama. 2017;318(2):118–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bowblis JR, Lucas JA, Brunt CS. The effects of antipsychotic quality reporting on antipsychotic and psychoactive medication use. Health services research. 2015;50(4):1069–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castle NG, Mor V. Hospitalization of nursing home residents: a review of the literature, 1980–1995. Medical Care Research and Review. 1996;53(2):123–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xing J, Mukamel DB, Temkin‐Greener H. Hospitalizations of nursing home residents in the last year of life: nursing home characteristics and variation in potentially avoidable hospitalizations. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2013;61(11):1900–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris JN, Fries BE, Morris SA. Scaling ADLs within the MDS. The Journals of Gerontology: Series A. 1999;54(11):M546–M553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas KS, Dosa D, Wysocki A, Mor V. The minimum data set 3.0 cognitive function scale. Medical care. 2017;55(9):e68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perlman CM, Hirdes JP. The aggressive behavior scale: a new scale to measure aggression based on the minimum data set. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(12):2298–2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maust DT, Kim HM, Chiang C, Kales HC. Association of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services’ National Partnership to Improve Dementia Care With the Use of Antipsychotics and Other Psychotropics in Long-term Care in the United States From 2009 to 2014. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2018;178(5):640–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter JD, Kerns JW, Winter KM, Sabo RT. Increased reporting of exclusionary diagnoses inflate apparent reductions in long-stay antipsychotic prescribing. Clinical gerontologist. 2019;42(3):297–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamshon L Push to Reduce Antipsychotic Drugs in Nursing Homes May Have Boosted Costly Hospitalizations. Skilled Nursing News. https://skillednursingnews.com/2019/10/push-toreduce-antipsychotic-drugs-in-nursing-homes-may-have-boosted-costly-hospitalizations/. Published 2019. Updated Oct 27, 2019. Accessed Feb 29, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Douglas S, James I, Ballard C. Non-pharmacological interventions in dementia. Advances in psychiatric treatment. 2004;10(3):171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. Jama. 2012;308(19):2020–2029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Li Q Quality of Care in Nursing Homes: The Impact of Dementia, Mental Illness, and Work Environment: Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Rochester; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Werner R, Stuart E, Polsky D. Public reporting drove quality gains at nursing homes. Health Affairs. 2010;29(9):1706–1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Konetzka RT, Brauner DJ, Shega J, Werner RM. The effects of public reporting on physical restraints and antipsychotic use in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2014;62(3):454–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Covert AB, Rodrigues T, Solomon K. The use of mechanical and chemical restraints in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1977;25(2):85–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Commission MaCPaA. States’ Medicaid Fee-for-Service Nursing Facility Payment Policies. https://www.macpac.gov/publication/nursing-facility-payment-policies/. Published 2019. Accessed March 2nd, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ouslander JG, Lamb G, Perloe M, et al. Potentially Avoidable Hospitalizations of Nursing Home Residents: Frequency, Causes, and Costs: [See editorial comments by Wyman Jean F. and Hazzard William R. , −pp 760–761] Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(4):627–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]