Abstract

Okra enation leaf curl is a newly emerging disease in commercial okra cultivation fields in Northern Sri Lanka. The present study aimed to identify and characterize the causative begomovirus and associated satellites. Okra plants showing the enation leaf curl disease symptoms were collected from Vavuniya and Jaffna districts of Northern Province. The PCR diagnostic and genome sequencing revealed that the symptomatic okra plants are associated with begomovirus, betasatellite, and alphasatellite complex. The begomovirus isolates shared 98.2–99.7% nucleotide identity with Okra enation leaf curl virus. The betasatellites showed 96–98.8% nucleotide identity with Bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite which is usually associated with Bhendi yellow vein mosaic disease. Two distinct alphasatellite species, Okra leaf curl alphasatellite and Bhendi yellow vein mosaic alphasatellite, were identified in leaf samples with enation leaf curl disease. The disease was transmitted by whiteflies from diseased plants to healthy plants. Hybrid varieties were more susceptible to the disease compared to cultivated varieties.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-020-02502-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Okra enation leaf curl, Begomovirus, Betasatellite, Alphasatellite

Introduction

Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) is cultivated in tropical, subtropical, and warm temperate regions for its edible fruits. Okra fruits are harvested when immature, and are commonly consumed as salads, soups, curry, and stews. The plant has been also used for several other purposes, such as the roots and stems are used for cleaning the cane juice during brown-sugar preparation (Shetty et al. 2013), seeds are used for extract of oil (Gemede et al. 2015), and the fruit has been found to possess various ethno-pharmacological and medicinal properties against cancer, high-cholesterol, and diabetes mellitus (Jenkins et al. 2005).

Okra is susceptible to a number of diseases caused by the members of genus Begomovirus (Family Geminiviridae). Among the begomovirus diseases, yellow vein mosaic disease (YVMD), okra leaf curl disease (OLCuD), and okra enation leaf curl disease (OELCuD) cause serious losses in okra cultivation in Indian subcontinent, Africa, and South America (Ghanem 2003; Venkataravanappa et al. 2013a; Mishra et al. 2017).

A number of distinct begomovirus species have been identified, which includes the species Bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus (Jose and Usha 2003), Okra yellow vein mosaic virus (Zhou et al. 1998), Cotton leaf curl Alabad virus (Venkataravanappa et al. 2012a), Bhendi yellow vein Haryana virus, Bhendi yellow vein Maharashtra virus, Bhendi yellow vein Bhubhaneswar virus (Venkataravanappa et al. 2013b), and Okra enation leaf curl virus (Venkataravanappa et al. 2015) infects, and causes diseases such as okra yellow vein mosaic disease, okra leaf curl disease, and okra enation leaf curl disease.

The members of genus Begomovirus have monopartite or bipartite genome. The bipartite genome consists of DNA-A and DNA-B components, each 2.5–2.6 kb in size. The DNA-A component encodes the information for viral DNA replication, transcription, and encapsidation, but requires the DNA-B component for systemic infection. The genomes of monopartite begomoviruses consist of single component which is homologous to DNA-A of bipartite begomoviruses. Begomovirus DNA-A has six open-reading frames which encodes the protein involved in replication, transcription, encapsulation, movement in host, and symptom expression (King et al. 2011).

Three classes of circular single-strand DNA satellites, namely beta, alpha, and deltasastellites, have been described as associated with begomoviruses: (Briddon et al. 2002; Zhou 2013; Lozano et al. 2016). Betasatellites are associated with many Old World monopartite begomoviruses, and depend on their helper begomoviruses for their movement, replication, and encapsulation. They are approximately 1.3 kb in size and encoding a single gene βC1. The product of the gene βC1 has been shown to function as a suppressor of host gene silencing, movement, and in some cases, they are essential for the maintenance of disease (Zhou 2013). Although the alphasatellites are dependent on their helper begomoviruses for systemic movement, and vector transmission, they are capable of autonomous replication in plant cells (Mansoor et al. 1999; Saunders and Stanley 1999).

In Sri Lanka, okra is a popular vegetable and ranked fourth among the low country vegetables based on cultivated extent (Abeykoon et al. 2010). It is cultivated either as a home garden crop or on a commercial scale in Sri Lanka. MI5, MI7, Haritha, and TV8 (‘Pall Vendi’) are the common okra varieties that are cultivated in Sri Lanka. In addition to the above varieties, several hybrid varieties have been recently introduced as resistant to OYVMD.

The Northern Province of Sri Lanka is one of the major okra growing regions of the country with a region-specific okra variety called Var.TV8 (also named as ‘Paal vendi’) are threatened by okra yellow vein mosaic disease. But recently, several hybrid varieties, such as No 521 and Maha F1, have been introduced in commercial cultivation as resistant to OYVMD. Even though the hybrid varieties are not affected by OYVMD, they show symptoms which had not been previously reported in Northern Sri Lanka. The disease is characterized by severe upward leaf curling, leaf and vein thickening, and stunted plant growth (Jeyaseelan et al. 2018). Leaf curl disease in vegetables, such as chilli and tomato, is already found as a major constrain in vegetable production in Sri Lanka (Samarakoon et al. 2012; Senanayake et al. 2013). The present study was carried out to identify and characterize the begomovirus species which is causing the leaf curl disease in Northern Sri Lanka. The analysis of samples collected from symptomatic plants revealed that the disease is associated with begomovirus–satellite complex.

Materials and methods

Samples collection and DNA extraction

Field survey was conducted in five Districts (Jaffna, Vavuniya, Mannar, Kilinochchi, and Mullaitivu) of Northern Province, Sri Lanka, between May and July in 2018. In each district, the disease incidence was measured in three different fields which were affected by the disease. In each field, the disease incidence was estimated by recording non-symptomatic and symptomatic plants at ten different randomly selected locations. Totally, 50 plants were observed in each field. Subsequently, samples from okra plants exhibiting typical symptoms of leaf curl disease were collected from three plants in each district, and total DNA was extracted using a modified DNA extraction protocol described by (Jeyaseelan et al. 2019).

PCR-mediated amplification and sequencing of begomovirus genome

Totally, 15 DNA samples collected from five districts were subjected to PCR amplification. The full-length genomes (DNA-A) of begomoviruses were PCR amplified using three sets of degenerate primers (synthesized by IDT, USA) which were designed to produce overlapping fragments of the genomes of old world begomoviruses (Venkataravanappa et al. 2012b). To rule out mixed infections, the primers were designed in such a way that the amplified product overlapped (approximately 200 bp) between the fragments amplified. PCR reactions were carried out in a volume of 20 µL reaction mix containing 10 µL ready-made PCR mix (PCR Biosystems, UK), 1 µL of forward and reverse primers (10 µM), and 1 µL DNA sample (about 50 ng). The thermocycler was set for 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 1 min, annealing at 58 °C for 45 s, and extension at 72 °C for 90 s. Runs included an initial denaturation at 94 °C for 3 min and a final extension at 72 °C for 15 min. PCR products were electrophoresed on 0.8% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide (10 mg/ml) and were viewed in a gel documentation system (Enduro GDS, Labnet, USA).

The DNA samples used for PCR detection of the DNA-A were also subjected to amplify DNA-B, betasatellite, and alphasatellite. PCRs for DNA-B component were carried out with the degenerate universal primers described by Rojas et al. (1993). Full length of betasatellite DNA was amplified with a pair of universal primers β01 and β02 as described by Briddon et al. (2002). Similarly, full length of alphasatellite DNA was amplified with a pair of primers AlphaF5 and AlphaR5 as described by Zia-Ur-Rehman et al. (2013).

PCR products of begomovirus DNA-A, betasatellite, and alphasatellite of a plant sample (Vav02) collected from Vavuniya District and another plant sample (Jfn01) collected from Jaffna District were used for cloning and sequencing. PCR products of the expected size were purified from agarose gels using a PCR purification kit (Wizard® SV Gel and PCR Clean-Up System, Promega, USA) and ligated to the plasmid vector pGEM®-T Easy Vector System I (Promega, USA) as described in the manufacturers’ protocols. For the DNA-A, the PCR products (about 1.5 kb each) obtained using three sets of degenerate primers were cloned separately. The complete genomes of betasatellite (about 1.3 kb) and alphasatellite (about 1.4 kb) were cloned in separate vectors.

The clones were sequenced by automated Sanger sequencing service (Macrogen, Korea). The complete nucleotide sequences were deposited in GenBank database; accession numbers are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic features of begomovirus and satellites isolated from okra plants with okra leaf curl disease from two different locations in Northern Sri Lanka

| Plant | Isolate | Species* | Accession number | Size | Nucleotide coordinates (number of amino acids) of predicted genes** | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Begomovirus | Alphasatellite | Betasatellite | |||||||||||

| CP | V2 | Rep | REn | TrAP | C4 | C5 | Rep | βC1 | |||||

| Vav02 | DAVav02 | OELCuV | MN389529 | 2741 | 276–1046 (256) | 116–463 (115) | 1495–2589 (364) | 1049–1453 (134) | 1146–1598 (150) | 2094–24,332 (112) | 612–980 (122) | – | – |

| Vav02 | BYVMB | MN384975 | 1352 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 180–602 (118) | |

| AlVav02 | OLCuA | MN384973 | 1380 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 82–1029 (315) | – | |

| Jfn01 | DAJfn01 | OELCuV | MN384976 | 2738 | 276–1046 (256) | 116–463 (115) | 1495–2586 (363) | 1049–1453 (134) | 1146–1598 (150) | 2091–24,329 (112) | 612–980 (122) | – | – |

| Jfn01 | BYVMB | MN384974 | 1344 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 177–599 (118) | |

| AlJfn01 | BhYVMA | MN384972 | 1378 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 79–1026 (315) | – | |

*Virus, betasatellite, and alphasatellite species are denoted as Okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV), Bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite (BYVMB), Okra leaf curl alphasatellite (OLCuA), and Bhendi yellow vein mosaic alphasatellite (BhYVMA)

**Genes are denoted as the coat protein (CP), V2 protein (V2), replication-associated protein (Rep), transcriptional activator protein (TrAP), replication-enhancer protein (REn), C4 protein (C4), C5 protein (C5), and the βC1 protein

Phylogenetic analysis and detection of recombination events

Identity searches for the DNA-A and DNA satellites identified in the present study were carried out using the BLASTn program available in the NCBI (Altschul et al. 1990). Sequence alignments were performed using MUSCLE (Edgar 2004) and pairwise identity scores were calculated using Sequence Demarcation Tool (SDT) (Muhire et al. 2014). The details of sequences retrieved from GenBank database are given in Supplementary Table 1. Phylogenetic analysis was performed in MEGA 7 (Kumar et al. 2016) using the maximum-likelihood algorithm with 1000 bootstrap replications.

The phylogenic evidence for recombination was detected with SplitsTree version 4.14.4 using the Neighbor-Net method (Huson and Bryant 2006). Putative parental viruses and recombination breakpoints were determined using Recombination Detection Program (RDP) v. 4.0 (Martin et al. 2015). Alignments were analyzed using default settings for different methods and statistical significance was defined as a P value less than the Bonferroni correction cut-off of 0.05.

Testing the virus transmission

For the transmission experiments, non-viruliferous, adult whiteflies Bemisia tabaci were obtained from the laboratory of Entomology, Horticultural Crop Research and Development Institute (HORDI), Gannoruwa, Sri Lanka. They were first cultured on brinjal plants (Solanum melongena) in insect proof cages. The non-viruliferous stage of the whiteflies was again confirmed with DNA samples extracted with randomly selected whiteflies in PCR using primer pair specific to begomovirus (Deng et al. 1994). The hybrid okra variety No.521, which is frequently affected by the leaf curl disease in the field, was chosen for this study. Ten-to-fifteen adult non-viruliferous whiteflies were given an acquisition access period of 12 h on leaves of infected plants and were then released onto healthy test plants for an inoculation access period of 12 h. Then, plants were sprayed with an insecticide [thiocyclam hydrogen oxalate (50% W/W)] and maintained under insect proof cages until symptoms were evaluated. The experiment was repeated three times and the inoculated plants showed leaf curl symptoms following each transmission to okra plants. The resulting infected plants were subjected to DNA extraction and tested for the presence of begomovirus genome using PCR as described (Deng et al. 1994).

Results

The development of OELCuD showed variation among different okra varieties which were grown in all five districts in Northern part of Sri Lanka. The fields having hybrid varieties such as No.521 and Maha F1 were severely affected by the disease, but the fields having cultivated varieties such as TV8, MI5, MI7, and Haritha were completely free from OELCuD. However, these cultivated varieties showed OYVMD more often. Even though both types of varieties were growing in the same field, the plants which showed leaf curl symptoms never developed yellow vein mosaic symptom and vice versa.

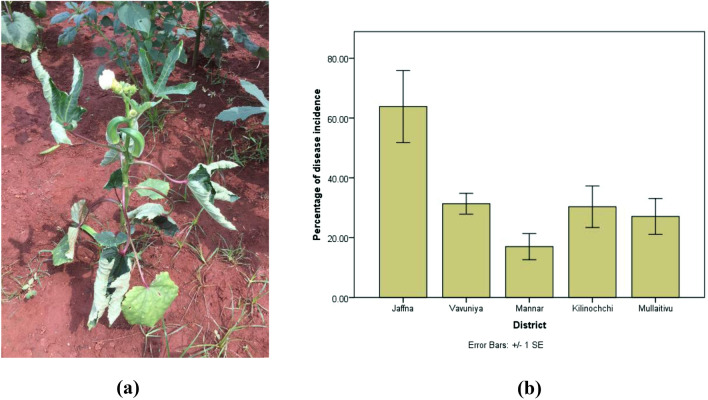

The symptom of OELCuD includes leaf curling, thick and leathery texture of leaves, and characteristic prominent enation on the under-surface of the leaves (Fig. 1a). The symptoms were more prominent in middle-aged leaves than young leaves. The affected plants show twisted stem and lateral branches. The leaves showed upward curling and venal thickening. Moreover, the infected plants become severely stunted with fruits being small, deformed, and unfit for sale. The disease incidence measured in each district varied among them (Fig. 1b), and the mean disease incidence ranged from 17% to 63.8%. Among the five districts, the mean disease incidence was highest in Jaffna and lowest in Mannar. In rest of the places, the mean disease incidence ranged between 27 and 32%.

Fig. 1.

a Symptoms exhibited by Okra enation leaf curl virus-infected okra plants in the field; severe upward leaf curling and associated vein thickening. b Disease incidence of OELCuD in different districts in Northern Province of Sri Lanka; the error bars are standard error of mean

Out of 15 samples tested through PCR, 15 were positive for DNA-A, 13 for betasatellite, nine for alphasatellite, and none for the DNA-B component, respectively. For the follow-up experiments, samples were selected based on the geographical distance among the sample collection sites and presence of DNA-A, betasatellite, and alphasatellite in the sample. Based on above criteria, plant samples Vav02 and Jfn01, collected from Vavuniya and Jaffna Districts, respectively, were selected for cloning and sequencing.

Cloning and sequencing of begomovirus-PCR products amplified using three sets of degenerate primers which specific to begomovirus yielded two isolates of 2741 nt and 2738 nt [DAVav02 (MN389529) and DAJfn01 (MN384976), respectively] representing samples from districts Vavuniya and Jaffna (Table 1). Sequence analysis showed that the two isolates have showed typical features of begomoviruses with conserved open-reading frames (ORFs) reported so far (Hanley-Bowdoin et al. 1999). In addition to the typical six ORFs, two conserved genes encoded in the virion-sense strand (encoding the CP and the V2 protein) and five genes in the complementary-sense strand (encoding the Rep, C2, Ren, C4, and C5). The IR sequences (between the start codons of the C1 and V2 ORFs) are 268 nt (nt 2589–116) for DAVav02 and (nt 2586–161 for DAJfn01).

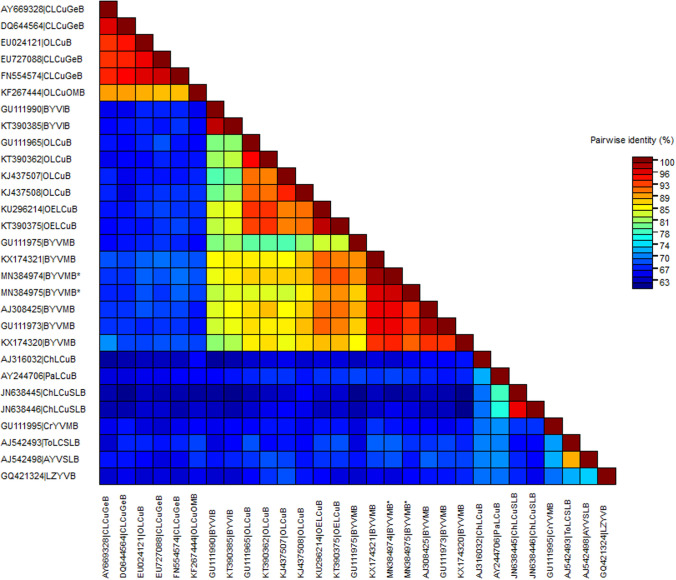

Both DAVav02 and DAJfn01 showed high level of sequence identity (98–99.7%) with several isolates of Okra enation leaf curl virus (OELCuV) in BLAST analysis. SDT analysis showed the sequences to have 98% identity between them, and showed the highest sequence identity (98.2–99.7%) with an isolate of the Sri Lankan strain of OELCuV (KX698092) isolated from Okra showing yellow vein mosaic symptom (Fig. 2). According to the present species delineation criteria for begomoviruses (Brown et al. 2015), the viruses isolated from okra leaf curl disease are considered as isolates of the Sri Lankan strain of OELCuV. Phylogenetic analysis further confirmed this by clustering the isolates with OELCuV which is associated with yellow vein mosaic symptom (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Colour-coded pairwise identity matrix generated from 54 different begomovirus DNA-As, including 2 OELCuV described in this work (with ‘*’ at the end of species name). See Supplementary Table 1 for details on the compared sequences. Each coloured cell represents a percentage identity score between two sequences. The coloured key indicates the correspondence between pairwise identities and the colours displayed in the matrix

Fig. 3.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis for two OELCuV described in this work (with red colour text) with selected begomoviruses. The evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum-Likelihood method based on the General Time Reversible model. The percentage of trees in which the associated taxa clustered together is shown next to the branches. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated

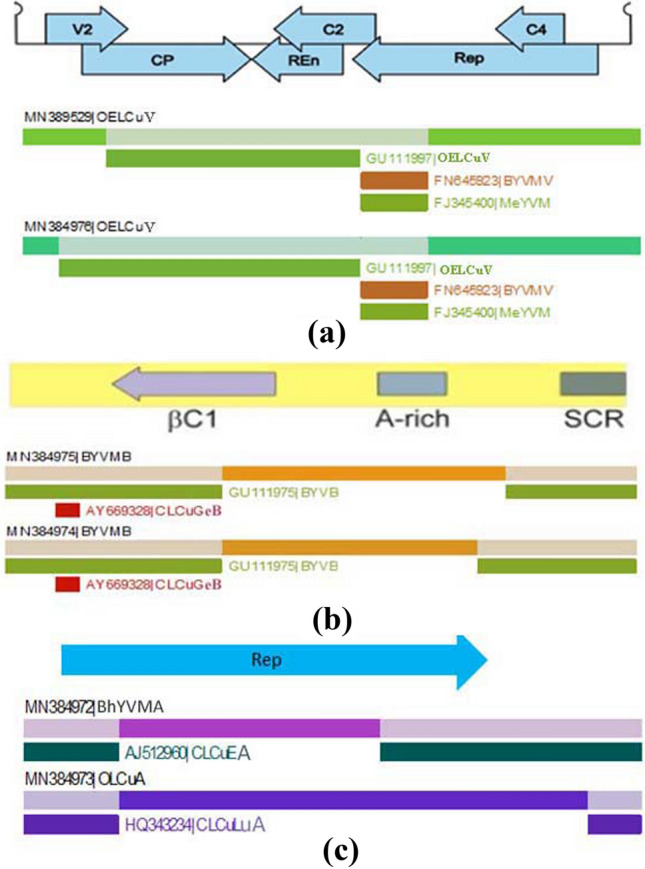

A Neighbor-Net analysis using the SplitsTree program revealed an extensive networked relationship of OELCuV isolates with other begomoviruses retrieved from GenBank (Supplementary Fig. 1). This reticulate network structure is an indicative of phylogenetic incongruence and suggests that parts of the sequences have been different origins due to recombination. Recombination analysis using RDP4 showed two possible recombinations in both DAVav02 and DAJfn01 isolates. In both events, isolates of BYVMV (KX698089 and AF241479) detected as major parents. Indian isolates of OELCuV (GU111997) contributed a large DNA segment for DAVav02 (270–1446 nt, P value = 8.06 × 10–27) and DAJfn01 (78–1446, P value = 7.08 × 10–35). In second recombination event, Mesta yellow vein mosaic virus [MeYVM (FJ345400)] contributed DNA fragment of 1447–1778 nt in DAVav02 and DAJfn01 isolates (Fig. 4a; Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 4.

RDP analysis for recombination of the begomovirus isolates (a), betasatellites (b), and alphasatellites (c). For each of the isolates, recombinant fragments are shown as shaded bars with the origin (parental virus species) indicated where it could be determined. The orientation and approximate position of genes are shown as arrows at the top of the diagram

Cloning and sequencing of PCR products obtained with a pair of universal primers β01 and β02 yielded two betasatellite isolates with 1352 nt and 1344 nt in size [Vav02 (MN384975) and Jfn01 (MN384974), respectively] (Table 1). Both consisting of a single predicted ORF (with a coding capacity of 118 amino acids), an adenine (A)-rich region, and a satellite conserved region (SCR) containing a predicted hairpin structure containing the geminivirus nonanucleotide sequence (TAATATTAC). An initial BLAST screen showed the sequences to have high sequence identity with several isolates of Bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite (BYVMB). The SDT analysis showed 96.8% sequence identity between both isolates (Fig. 5). Comparison to selected betasatellite species available in the databases showed nucleotide sequence identity of 96–98.8% with an isolate of BYVMB obtained from okra showing yellow vein mosaic symptom in Sri Lanka (KX174321). Based on the presently applicable species demarcation criteria for betasatellites (91%; https://talk.ictvonline.org/ICTV/propos a l s/2016. 021a—kP.A. v 2.Tolecusatellitidae.pdf), this indicates that both Vav02 and Jfn01 betasatellites are isolates of BYVMB.

Fig. 5.

Colour-coded pairwise identity matrix generated from 29 different betasatellite DNAs, including 2 BYVMB described in this work (with ‘*’ at the end of species name). See Supplementary Table 1 for details on the compared sequences. Each coloured cell represents a percentage identity score between two sequences. The coloured key indicates the correspondence between pairwise identities and the colours displayed in the matrix

In phylogenetic analysis, both isolates were closely cluster with BYVMB reported from Sri Lanka and India (Fig. 6a). A Neighbor-Net analysis using the SplitsTree program revealed an extensive networked relationship of Vav02 and Jfn01 isolates with other betasatellites (Supplementary Fig. 2). A possible recombinant fragment was detected in both isolates by RDP4 analysis. The Sri Lankan BYVMB isolates (MN384975 and MN384974) emerged by a recombination between an isolate of BYVMB (GU111975) and an isolate of Bhendi yellow vein India betasatellite [BYVIB (KT390385)] (Fig. 4b; Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 6.

a Molecular phylogenetic analysis for two BYVMB described in this work (with red colour text) with selected betasatellites. The evolutionary history was inferred using the maximum-likelihood method based on the Tamura three-parameter model. b Molecular phylogenetic analysis for two alphasatellites described in this work (with bold text) with selected different alphasatellite species described by Briddon et al. (2018)

Cloning and sequencing of samples amplified with alphasatellite-specific primers showed features of typical alphasatellites. The size of AlVav02 (MN384973) and AlJfn01 (MN384972) was 1380 nt and 1378 nt, respectively (Table 1). The isolates AlVav02 and AlJfn01 have a single conserved ORF encoded in the virion-sense, an A-rich sequence, and a predicted stem-loop structure containing, within the loop, the nonanucleotide sequence TAGTATTAC with similarity to the origin of replication of nanoviruses. An initial BLAST screen of AlVav02 and AlJfn01 showed the highest sequence identity with several isolates of Okra leaf curl alphasatellite (OLCuA) (92–98%) and Bhendi yellow vein mosaic alphasatellite (BhYVMA) (96.7–97.5%), respectively. In SDT analysis, the identity between AlVav02 and AlJfn01 was 80.3% (Fig. 7), and thus likely to represent isolates of two different alphasatellite species based on the recently proposed species demarcation criteria for alphasatellites [88%; (Briddon et al. 2018)]. The SDT analysis revealed that the isolate AlVav02 had 98.2% sequence identity with an Indian OLCuA isolate (KF471055), whereas AlJfn01 showed 97.6% of nucleotide identity with isolates of Indian BhYVMA (FN658716). A phylogenetic analysis, confirmed the association of two distinct alphasatellite species with okra leaf curl disease, belongs to the two distinct clades in subfamily colecusatellite; indicates their distinct evolutionary histories (Fig. 6b). A Neighbor-Net analysis using the SplitsTree program indicates recombination in two alphasatellite isolates (Supplementary Fig. 3). Nevertheless, the tree agrees with the phylogenetic analysis shown in Fig. 6b that these two isolates are distinct from Okra enation leaf curl alphasatellite [OELCuA (HF546575)] isolated from OELCuD in India. The recombinant breakpoint analysis using RDP4 revealed a recombination event in the Sri Lankan BhYVMA, where Mesta yellow vein mosaic alphasatellite [MeYVMA (JX183090)] and Cotton leaf curl Egypt alphasatellite [CLCuEA (AJ512960)] were the major and minor parents, respectively. Similarly, a recombination event detected in Sri Lankan OLCuA, here Malvastrum yellow mosaic alphasatellite [MaYA (AM236765)], was the major parent, and Cotton leaf curl Lucknow alphasatellite [CLCuLuA (HQ343234)] was the minor parent (Fig. 4c; Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 7.

Colour-coded pairwise identity matrix generated from 41 different alphasatellites, including two species described in this work (with ‘*’ at the end of species name). See Supplementary Table 1 for details on the compared sequences. Each coloured cell represents a percentage identity score between two sequences. The coloured key indicates the correspondence between pairwise identities and the colours displayed in the matrix

The okra variety No 521 infested by viruliferous whiteflies showed leaf curling, thick and leathery texture of leaves, which is characteristic of OELCuD. The symptoms started to develop from 15 to 20 days after inoculation. In each replicate, 20 plants were allowed for whitefly infestation and more than 50% of the plants showed disease symptoms. The plant which showed symptoms also showed positive to PCR reactions carried out with primers specific to begomovirus.

Discussion

Diseases caused by begomoviruses are an increasing problem for okra production in South Asia. In Sri Lanka, okra cultivation has been highly threatened by BYVMD, but recently OELCuD is an emerging problem, especially in Northern Province. The present study has shown that the disease is not vertically transmitted by seeds, in agreement with the previous studies (Fargette et al. 1996; Brown et al. 2015). Similar to other begomovirus diseases, this disease is transmitted by whitefly. Northern Province is with suitable elevated temperature for whitefly reproduction and infestation, compare to other okra growing provinces in Sri Lanka (Stephenson et al. 2019).

OELCuD is most often reported in countries such as India and Pakistan, where it causes a significant loss in the okra production (Singh 1996; Chandran et al. 2013; Hameed et al. 2014; Venkataravanappa et al. 2015). So far, there is no report of the disease in Africa and America. The OELCuD was first reported from Karnataka (Bangalore) in southern India in the early 1980s (Singh and Dutta 1986; Singh 1996); later, it was reported in Saudi Arabia (Ghanem 2003) and in Pakistan (Hameed et al. 2014). A previous study conducted by Jeyaseelan et al. (2018) did some preliminary work on this aspect. They described the disease based on the symptoms and confirmed the association of begomovirus and satellite in PCR with specific primers. In the present study, the complete genome sequence of begomovirus and satellites have been identified and characterized.

In Asia, majority of the okra diseases of begomovirus are caused by begomovirus–satellite complex. Recently, however, bipartite begomoviruses, Bhendi yellow vein Delhi virus (BYVMDV) have been isolated from okra (Venkataravanappa et al. 2012b). In the present study, a monopartite begomovirus OELCuV has been identified. This is the first OELCuV identified in okra plants with okra enation leaf curl disease from Sri Lanka. There are some genome sequences of OELCuV already deposited in GenBank from Sri Lanka, but they were associated with OYVMD (Unpublished work). The two OECLCuV isolates DAVav02 and DAJfn01 showed 98% sequence identity between them, even though the samples were collected from two different farms apart about 150 km. Because of > 94% sequence identity reveals that both isolates must be the same strain of OELCuV (Brown et al. 2015).

Earlier in India, it was reported that the OELCuD is associated with OELCuV and Okra enation leaf curl alphasatellite (Chandran et al. 2013). Similar finding was made by Serfraz et al. (2015) in Pakistan, where the OELCuV was associated with Ageratum conyzoides symptomless alphasatellite. Venkataravanappa et al. (2011) found that two distinct betasatellites, namely Bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite and Okra leaf curl betasatellite, were associated with the disease in India. The present study reports that a complex of OELCuV, BYVMB, and two distinct species of alphasatellites (OLCuA and BhYVMA) are associated with the disease in Sri Lanka. In addition, the alphasatellites reported in this study are the first alphasatellite species reported from okra in Sri Lanka.

For the majority of betasatellite-associated diseases, such as CLCuD and Ageratum yellow vein disease, betasatellite encodes the dominant symptom determinant (Saunders et al. 2004; Saeed et al. 2005). For CLCuD in Asia, it has been suggested that although the betasatellite determines symptoms, this must be carried to the correct plant tissues by the virus for bonafide disease symptoms to ensue (Saeed et al. 2005). In the present study, however, BYVMB is associated with the disease. This would seem to indicate that OELCuD may be caused by one virus (OELCuV) in association with distinct betasatellites.

In general, in Southern parts of India, YVMV and OELCuV diseases of okra show either leaf curl or yellow vein mosaic symptoms (Sohrab et al. 2013). However, under Northern Indian conditions, both YVMV and OELCuV cause symptoms on the same plants. The observation in the present study coincides with the tendency observed in Southern India.

In the present study, the OELCuD was observed only in some hybrid okra varieties but not in traditional varieties, even though they grow in same field. It is possible that the betasatellites associated with OELCuV encode the dominant symptom determinant, but the tissue specificity of virus or plant response against virus may influence symptom development. Therefore, studies with infectious clones will be needed to investigate the contribution of each component (virus, betasatellite, and plant) makes to symptoms in plants.

Okra is known to be susceptible to at least 27 different species of begomoviruses (Mishra et al. 2017). The wide diversity among begomoviruses associated with mixed infections is supposedly assisting in recombination and pseudo-recombination events leading to the frequent emergence of novel begomoviruses, having devastating effects on the okra (Padidam et al. 1999). Recombination has played a significant role in the evolution of geminiviruses (Seal et al. 2006) including the origin of OELCuV, as the sequences making up OELCuV have originated from other malvaceous begomoviruses; Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus (CLCuBaV), Mesta yellow vein mosaic virus (MeYVMV), and BYVMV (Venkataravanappa et al. 2015). The present study showed that the OELCuV in Sri Lanka has evolved by recombination of malvaceous begomoviruses; BYVMV, OELCuV, and MeYVMV. The betasatellites analyzed in this study originated by recombination between two betasatellites, BYVIB and BYVMB. Venkataravanappa et al. (2011) reported that the BYVIB was associated with okra plants showing upward leaf curling and vein twisting symptoms; meanwhile, the isolate BYVMB was detected in okra plant with yellow vein mosaic symptom. Recombination was also detected in the two different alphasatellite species, BhYVMA and OLCuA, reported in the present study. Both of them showed their origin from unrelated major and minor parents. The BhYVMA has been reported as associated with Bhendi yellow vein mosaic virus or Mesta yellow vein mosaic virus in okra (Zaffalon et al. 2012). However, in the present study, the BhYVMA is associated with OELCuV. This clearly shows the co-existence of this alphasatellite with different species of begomoviruses which infect okra.

Conclusions

The newly emerging enation leaf curl disease in okra is caused by the association of a complex of monopartite begomovirus, betasatellite, and alphasatellite in Sri Lanka. The monopartite begomovirus is identified as Okra enation leaf curl virus, and the virus is transmitted by whitefly vector. A betasatellite associated with okra yellow vein mosaic disease, Bhendi yellow vein mosaic betasatellite, is associated with the okra enation leaf curl disease, as well. Two distinct alphasatellites, namely Okra leaf curl alphasatellite and Bhendi yellow vein mosaic alphasatellite, have been detected in two different samples. Further studies are needed to find out the role of virus and satellites in okra enation leaf curl symptom development.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file2 Figure S1. Neighbor-Net constructed from alignment of the sequences. (a) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the OELCuV sequences with the sequences of the genomes (or DNA A components) of selected other begomoviruses. (b) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the BYVMB sequences with the sequences of the genomes of selected other betasatellites. (c) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the aphasatellites sequences of present study with the sequences of the genomes of selected other aphasatellites (PDF 349 kb)

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Mr. P.T.J. Jashothan, Technical Officer, Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of Jaffna for valuable technical supports.

Author contribution

ECJ and MWS conceived and designed the experiments. ECJ and SM conducted laboratory experiments. ECJ performed all the bioinformatics analysis. ECJ prepared the manuscript. MWS edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the University Jaffna, Sri Lanka, under the university research grant (URG/2017/SEIT/01).

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abeykoon A, Fonseka R, Paththinige S, Weerasinghe K. Fertilizer requirement for densely planted okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) Trop Agric Res. 2010;21:275–283. doi: 10.4038/tar.v21i3.3301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon RW, Bull SE, Mansoor S, Amin I. Universal primers for the PCR-mediated amplification of DNA β: a molecule associated with some monopartite begomoviruses. Mol Biotechnol. 2002;20:315–318. doi: 10.1385/MB:20:3:315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briddon RW, Martin DP, Roumagnac P, Navas Castillo J, Fiallo-Olivé E, Moriones E, et al. Alphasatellitidae: a new family with two subfamilies for the classification of geminivirus and nanovirus associated alphasatellites. Arch Virol. 2018;163:2587–2600. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3854-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JK, Zerbini FM, Navas-Castillo J, Moriones E, Ramos-Sobrinho R, Silva JC, et al. Revision of begomovirus taxonomy based on pairwise sequence comparisons. Arch Virol. 2015;160:1593–1619. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2398-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandran SA, Packialakshmi RM, Subhalakshmi K, Prakash C, Poovannan K, Nixon Prabu A, et al. First report of an alphasatellite associated with Okra enation leaf curl virus. Virus Genes. 2013;46:585–587. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0898-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng D, Mcgrath PF, Robinson DJ, Harrison BD. Detection and differentiation of whitefly transmitted geminiviruses in plants and vector insects by the polymerase chain reaction with degenerate primers. Ann Appl Biol. 1994;125:327–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1994.tb04973.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar RC. MUSCLE: Multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fargette D, Colon LT, Bouveau R, Fauquet C. Components of resistance of cassava to African cassava mosaic virus. Eur J Plant Pathol. 1996;102:645–654. doi: 10.1007/BF01877245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gemede HF, Ratta N, Haki GD, Woldegiorgis AZ, Beyene F. Nutritional quality and health benefits of okra (Abelmoschus esculentus): a review. J Food Process Technol. 2015;6(458):2. doi: 10.4172/2157-7110.1000458. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ghanem GAM. Okra leaf curl virus: a monopartite begomovirus infecting okra crop in Saudi Arabia. Arab J Biotechnol. 2003;6:139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Hameed U, Zia-Ur-Rehman M, Herrmann H, Haider MS, Brown JK. First report of Okra enation leaf curl virus and associated Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite and Cotton leaf curl Multan alphasatellite infecting cotton in Pakistan: a new member of the cotton leaf curl disease complex. Plant Dis. 2014;98:1447. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-04-14-0345-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley-Bowdoin L, Settlage SB, Orozco BM, Nagar S, Robertson D. Geminviruses: models for plant DNA replication, transcription, and cell cycle regulation. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 1999;18:71–106. doi: 10.1080/07352689991309162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huson DH, Bryant D. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:254–267. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msj030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Marchie A, Faulkner DA, Wong JM, de Souza R, et al. Direct comparison of a dietary portfolio of cholesterollowering foods with a statin in hypercholesterolemic participants. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:380–387. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.81.2.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaseelan EC, Sharmya M, Jeyaseelan TC, Shaw MW (2018) Okra leaf curl disease : an emerging threat to okra cultivation in Northern Sri Lanka. In: Proceedings of the 3rd International Research Symposium on Pure and Applied Sciences. Faculty of Science, University of Kelaniya, p. 12

- Jeyaseelan TC, Jeyaseelan EC, De Costa DM, Shaw MW. Selecting and optimizing a reliable DNA extraction method for isolating viral DNA in okra (Abelmoschus esculentus) Vingnanam J Sci. 2019;14:7–13. doi: 10.4038/vingnanam.v14i1.4140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jose J, Usha R. Bhendi yellow vein mosaic disease in India is caused by association of a DNA betasatellite with a Begomovirus. Virology. 2003;305:310–317. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King AMQ, Lefkowitz EJ, Adams MJ, Carstens EB (2011) Virus taxonomy. Ninth report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis Version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano G, Trenado HP, Fiallo-Olivé E, Chirinos D, Geraud-Pouey F, Briddon RW, et al. Characterization of non-coding DNA satellites associated with sweepoviruses (Genus Begomovirus, Geminiviridae)—definition of a distinct class of begomovirus-associated satellites. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:162. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansoor S, Khan SH, Bashir A, Saeed M, Zafar Y, Malik KA, et al. Identification of a novel circular single-stranded DNA associated with cotton leaf curl disease in Pakistan. Virology. 1999;259:190–199. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DP, Murrell B, Golden M, Khoosal A, Muhire B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015;1:1–5. doi: 10.1093/ve/vev003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra GP, Singh B, Seth T, Singh AK, Halder J, Krishnan N. Biotechnological advancements and begomovirus management in Okra (Abelmoschus esculentus L.): status and perspectives. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8:360. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhire BM, Varsani A, Martin DP. SDT: A virus classification tool based on pairwise sequence alignment and identity calculation. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e108277. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padidam M, Sawyer S, Fauquet CM. Possible emergence of new Geminiviruses by frequent recombination. Virology. 1999;265:218–225. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rojas MR, Gilbertson RL, Russell DR, Maxwell DP. Use of degenerate primers in the polymerase chain reaction to detect whitefly-transmitted geminiviruses. Plant Dis. 1993;77:340–347. doi: 10.1094/PD-77-0340. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saeed M, Behjatnia SA, Mansoor S, Zafar Y, Hasnain S, Rezaian MA. A single complementary-sense transcript of a geminiviral DNA betasatellite is determinant of pathogenicity. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2005;18:7–14. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarakoon SAM, Balasuriya A, Rajapaksha RGA, Wickramarachchi WAR. Molecular detection and partial characterization of Tomato yellow leaf curl virus in Sri Lanka. Pakistan J Biol Sci. 2012;15:863–870. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2012.863.870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders K, Stanley J. A nanovirus-like DNA component associated with yellow vein disease of Ageratum conyzoides: evidence for interfamilial recombination between plant DNA viruses. Virology. 1999;264:142–152. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders K, Norman A, Gucciardo S, Stanley J. The DNA β satellite component associated with ageratum yellow vein disease encodes an essential pathogenicity protein (βC1) Virology. 2004;324:37–47. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seal SE, VandenBosch F, Jeger AM. Factors influencing begomovirus evolution and their increasing global significance: implications for sustainable control. Crit Rev Plant Sci. 2006;25:23–46. doi: 10.1080/07352680500365257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Senanayake DMJB, Jayasinghe JEARM, Shilpi S, Wasala SK, Mandal B. A new begomovirus-betasatellite complex is associated with chilli leaf curl disease in Sri Lanka. Virus Genes. 2013;46:128–139. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0836-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serfraz S, Amin I, Akhtar KP, Mansoor S. Recombination among begomoviruses on malvaceous plants leads to the evolution of Okra enation leaf curl virus in Pakistan. J Phytopathol. 2015;163:764–776. doi: 10.1111/jph.12373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shetty AA, Singh JP, Singh D. Resistance to yellow vein mosaic virus in okra: a review. Biol Agric Hortic. 2013;29:159–164. doi: 10.1080/01448765.2013.793165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S. Assessment of losses in okra due to enation leaf curl virus. Indian J Virol. 1996;12:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Dutta O. Enation leaf curl of okra -a new virus disease. Indian J Virol. 1986;2:114–117. [Google Scholar]

- Sohrab SS, Mirza Z, Karim S, Rana D, Abuzenadah AM, Chaudhary AG, et al. Detection of begomovirus associated with okra leaf curl disease. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2013;46:1047–1053. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2012.757068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson RC, Coker CEH, Posadas BC, Bachman GR, Harkess RL, Adamczyk JJ. Effect of high tunnels on populations of whiteflies, aphids and thrips on tomatoes in Mississippi. J Hortic. 2019 doi: 10.35248/2376-0354.19.06.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Lakshminarayana Reddy C, Swaranalatha P, et al. Diversity and phylogeography of begomovirus-associated beta satellites of okra in India. Virol J. 2011;8:555. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Lakshminarayana R, Swarnalatha P, Devaraju JS, Reddy MK. Molecular evidence for association of Cotton leaf curl Alabad virus with yellow vein mosaic disease of okra in North India. Arch Phytopathol Plant Prot. 2012;45:2095–2113. doi: 10.1080/03235408.2012.721682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Lakshminarayana Reddy CN, Jalali S, Krishna Reddy M. Molecular characterization of distinct bipartite begomovirus infecting bhendi (Abelmoschus esculentus L.) in India. Virus Genes. 2012;44:522–535. doi: 10.1007/s11262-012-0732-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Lakshminarayana Reddy CN, Devaraju A, Jalali S, Reddy MK. Association of a recombinant Cotton leaf curl Bangalore virus with yellow vein and leaf curl disease of okra in India. Indian J Virol. 2013;24:188–198. doi: 10.1007/s13337-013-0141-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Reddy CNL, Jalali S, Reddy MK. Molecular characterization of a new species of begomovirus associated with yellow vein mosaic of bhendi (Okra) in Bhubhaneswar, India. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2013;136:811–822. doi: 10.1007/s10658-013-0209-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Venkataravanappa V, Reddy CNL, Jalali S, Briddon RW, Reddy MK. Molecular identification and biological characterization of a begomovirus associated with okra enation leaf curl disease in India. Eur J Plant Pathol. 2015;141:217–235. doi: 10.1007/s10658-014-0463-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X. Advances in understanding Begomovirus satellites. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 2013;51:357–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev-phyto-082712-102234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Liu Y, Robinson DJ, Harrison BD. Four DNA-A variants among Pakistani isolates of cotton leaf curl virus and theiraffinities to DNA-A of geminivirus isolates from okra. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:915–923. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-4-915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zia-Ur-Rehman M, Herrmann HW, Hameed U, Haider MS, Brown JK. First detection of Cotton leaf curl Burewala virus and cognate Cotton leaf curl Multan betasatellite and Gossypium darwinii symptomless alphasatellite in Symptomatic Luffa cylindrica in Pakistan. Plant Dis. 2013;97:1122. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-12-12-1159-PDN. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaffalon V, Mukherjee SK, Reddy VS, Thompson JR, Tepfer M. A survey of geminiviruses and associated satellite DNAs in the cotton-growing areas of northwestern India. Arch Virol. 2012;157(3):483–495. doi: 10.1007/s00705-011-1201-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary file2 Figure S1. Neighbor-Net constructed from alignment of the sequences. (a) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the OELCuV sequences with the sequences of the genomes (or DNA A components) of selected other begomoviruses. (b) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the BYVMB sequences with the sequences of the genomes of selected other betasatellites. (c) A Neighbor-Net constructed from an alignment of the aphasatellites sequences of present study with the sequences of the genomes of selected other aphasatellites (PDF 349 kb)