Abstract

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is driven by mutations that activate canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling, but inhibiting WNT has significant on-target toxicity, and there are no approved therapies targeting dominant oncogenic drivers. We recently found that activating a β-catenin independent branch of WNT signaling that inhibits GSK3-dependent protein degradation induces asparaginase sensitivity in drug-resistant leukemias. To test predictions from our model, we turned to CRC because these can have WNT-activating mutations that function either upstream (i.e., R-spondin fusions) or downstream (APC or β-catenin mutations) of GSK3, thus allowing WNT/β-catenin and WNT-induced asparaginase sensitivity to be unlinked genetically. We found that asparaginase had little efficacy in APC or β-catenin mutant CRC, but was profoundly toxic in the setting of R-spondin fusions. Pharmacologic GSK3α inhibition was sufficient for asparaginase sensitization in APC or β-catenin mutant CRC, but not in normal intestinal progenitors. Our findings demonstrate that WNT-induced therapeutic vulnerabilities can be exploited for CRC therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the US, and outcomes are dismal for patients with metastatic disease (1,2). An estimated 96% of CRCs have mutations that activate canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling (3), and these mutations promote intestinal transformation (4,5). Despite a compelling rationale for therapeutic inhibition of this pathway (6), oncogenic β-catenin (also known as CTNNB1) activity is difficult to inhibit directly (7). The discovery that approximately 15% of CRCs have mutations that drive ligand-dependent activation of WNT signaling, such as R-spondin (RSPO) fusions and RNF43 mutations (8-13), prompted considerable interest in therapeutic inhibition of WNT ligand activity. This is much more tractable pharmacologically, and a number of approaches targeting ligand-induced WNT pathway activation have been developed [reviewed in (7)]. However, inhibiting WNT ligand activity leads to significant bone toxicity with pathologic fractures (14). This is an on-target toxicity also seen in patients with germline mutations of WNT ligands (15,16). While efforts to mitigate this toxicity are ongoing, whether inhibition of WNT signaling has a sufficiently favorable therapeutic index for cancer therapy remains unclear.

Asparaginase, an antileukemic enzyme that degrades the nonessential amino acid asparagine (17), has little activity in unselected patients with CRC (18-20), most of whom have APC mutations (3). We recently found that activation of WNT signaling upstream of GSK3 induces potent sensitization to asparaginase in drug-resistant acute leukemias, but not in normal hematopoietic progenitors (21). WNT-induced signal transduction is mediated by inhibition of the kinase GSK3 (22-24), and GSK3 inhibition was sufficient for asparaginase sensitization in leukemias. However, this effect appeared to be independent of APC or β-catenin. Instead, asparaginase sensitization was mediated by WNT-dependent stabilization of proteins (WNT/STOP), a β-catenin independent branch of WNT signaling that inhibits GSK3-dependent protein ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (25). Proteasomal protein degradation is a catabolic source of amino acids (26,27) required for asparaginase resistance in leukemia (21), and this adaptive response is blocked by WNT-induced inhibition of GSK3.

CRC provides a unique experimental context in which to test predictions from our model, because mutations that arise spontaneously in CRC are predicted to unlink WNT/β-catenin from WNT-induced sensitization to asparaginase. Approximately 10-15% of CRCs have mutations that activate WNT signaling upstream of GSK3, such as R-spondin fusions (8-9). These mutations are predicted to stimulate WNT ligand-induced inhibition of GSK3, thus resulting in activation of both β-catenin and WNT-induced sensitization to asparaginase. By contrast, approximately 85% of human CRC have mutations of genes such as APC or β-catenin (also known as CTNNB1) (3,28), which we predicted would selectively activate the β-catenin branch of WNT signaling downstream of GSK3, without activating WNT/STOP or inducing asparaginase sensitivity. The objective of this study was to test these predictions in the context of mutations that arise spontaneously in CRC.

RESULTS

WNT pathway activation upstream of GSK3 induces asparaginase hypersensitivity

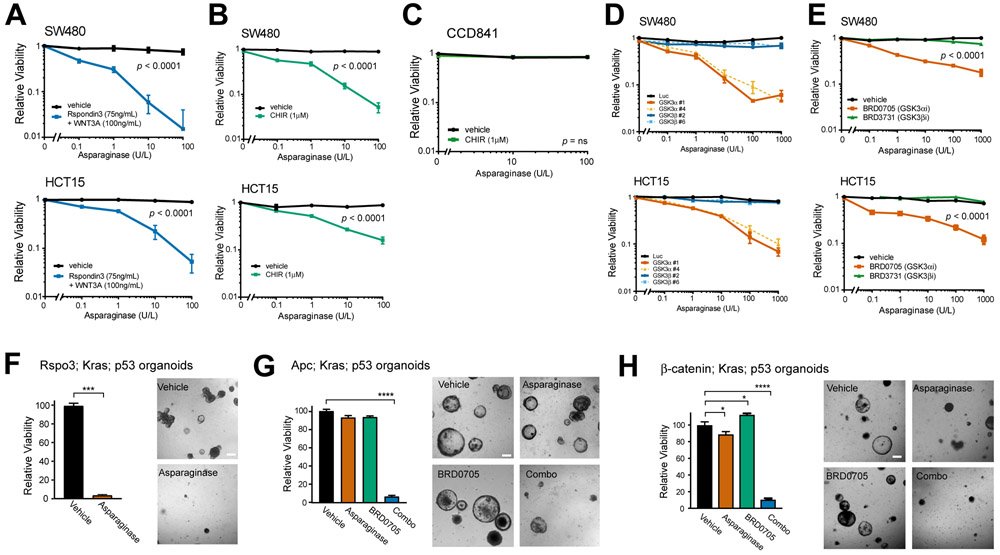

To test whether ligand-induced WNT pathway activation induces asparaginase hypersensitivity in CRC, we began with the human APC-mutant CRC cell lines HCT15 and SW480 (Table S1) (29,30). Treatment with asparaginase revealed that both of these cell lines were refractory to asparaginase monotherapy, but treatment with the recombinant ligands Rspo3 and Wnt3a induced significant sensitization to asparaginase (Fig. 1A). WNT-induced signal transduction is mediated by inhibition of the kinase GSK3 (22-24), and treatment of these cells with CHIR-99021, a small molecule inhibitor of both GSK3α and GSK3β (31) was sufficient to induce asparaginase sensitivity (Fig. 1B). Importantly, the combination of GSK3 inhibition and asparaginase had little toxicity to CCD841 cells derived from normal human colonic epithelium (Fig. 1C) (32).

Figure 1. Activation of WNT signaling upstream of GSK3 induces asparaginase hypersensitivity.

A, SW480 and HCT15 cells were treated with the indicated doses of asparaginase for 10 days, in the presence of recombinant Rspondin3 (75 ng/ml) and WNT3a (100 ng/ml) or vehicle. The number of viable cells was counted by trypan blue vital dye staining, and all cell counts were normalized to those in vehicle-treated cells (no asparaginase, Rspo3 or WNT3a). Two-way ANOVA was performed for each cell line and included interaction terms between asparaginase doses and WNT ligands. The p value for the main effect of WNT ligands vs. vehicle is presented in each plot and the interaction terms were overall significant (p < 0.0001).

B, SW480 and HCT15 cells were treated with the GSK3 inhibitor CHIR99021 (CHIR, 1μM) or vehicle, together with the indicated doses of asparaginase for 10 days. Viability was assessed as in (A). Statistical significance was calculated using a two-way ANOVA and included interaction terms between asparaginase doses and GSK3 inhibitor. The p value for the main effect of WNT ligands vs. vehicle is presented in each plot and the interaction terms were significant (p < 0.0001).

C, CCD841 cells derived from normal human colonic epithelium were treated with CHIR99021 (1 μM) or vehicle, together with the indicated doses of asparaginase for 10 days, and viable cell counts were assessed as described in (A). Two-way ANOVA was performed for each cell line and included interaction terms between asparaginase dose and GSK3 inhibitor. The interaction terms were not significant (p = ns).

D, SW480 and HCT15 cells were transduced with the indicated shRNAs and then treated with the indicated doses of asparaginase. Viability was assessed after 10 days of treatment by counting viable cells. All cell counts were normalized to those in shLuc-transduced, vehicle-treated controls.

E, The indicated cell lines were treated with vehicle, the GSK3α-selective inhibitor BRD0705 (1 μM), or the GSK3β-selective inhibitor BRD3731 (1 μM), in the presence of the indicated doses of asparaginase for 10 days. Viability was assessed as in (A). Two-way ANOVA was performed and included interaction terms between asparaginase dose and type of GSK3 inhibitor type. The p value for the main effect of GSK3 inhibitor type is presented.

F, Mouse intestinal organoids expressing an endogenous Rspo3 fusion in addition to p53 loss-of-function and an activating KrasG12D mutations were cultured in basal medium (which lacks WNT/R-spondin supplementation) and treated with vehicle or asparaginase (100 U/L) for 10 days. Viability was assessed by counting viable organoids using an Axio Imager A1 microscope. Images were taken from a representative of three experiments, and statistical significance was calculated using a two-sided Welch t-test. Scale bar, 100 μm.

G, Apc-deficient organoids with mutations of p53 and Kras were cultured in basal medium and treated with vehicle, asparaginase (100 U/L), BRD0705 (1 μM) or combo (100 U/L asparaginase + 1 μM BRD0705) for 10 days. Viability was assessed as in (F). Images were taken from a representative of three experiment. Scale bar, 100 μm. Differences between groups were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s adjustment for multiple comparisons, using the vehicle group as the reference group.

H, Organoids with a β-catenin activating mutation, as well as Kras and p53 mutations, were cultured in basal medium, treated and analyzed as in (G).

Mammalian cells have two GSK3 paralogs (GSK3α and GSK3β) that are redundant for regulation of canonical WNT/β-catenin signaling in several experimental contexts (33-35). However, we found that knockdown of GSK3α was sufficient for asparaginase sensitization in CRC, whereas GSK3β knockdown had little effect (Fig. 1D, Supplementary Fig. S1A-S1B). Treatment of HCT15 or SW480 cells with asparaginase in combination with GSK3α shRNA knockdown led to induction of caspase 3/7 activity, a marker of apoptosis induction (Supplementary Fig. S1C-S1D). We then used recently described isoform-selective GSK3 inhibitors to validate these findings pharmacologically (35). Treatment with the GSK3α-selective inhibitor BRD0705 sensitized both HCT15 and SW480 cells to asparaginase-induced cytotoxicity, whereas the GSK3β-selective inhibitor BRD3731 had little effect (Fig. 1E).

We then asked whether these findings are relevant in the context of endogenous mutations that arise spontaneously in CRC. Thus, we turned to genetically engineered mouse intestinal organoids designed to recapitulate the genetics of human CRC (6,9,36). The combination of KRAS, p53 (also known as TP53 in humans or Trp53 in mice) and a WNT/β-catenin activating mutation is a common genotype in metastatic CRC (3), thus we leveraged triple-mutant organoids harboring these mutations. The WNT-activating mutations were of distinct types: i) Apc deficiency or a β-catenin (Ctnnb1) activating mutation (S33F), both of which we predicted would activate WNT/β-catenin without inhibiting GSK3 or activating WNT/STOP, and thus have no effect on asparaginase sensitivity; or ii) an endogenous Ptprk-Rspo3 fusion that potentiates WNT ligand-induced inhibition of GSK3, which we predicted would activate both β-catenin and WNT/STOP, leading to asparaginase sensitivity. Treatment of these organoids revealed that asparaginase monotherapy was highly toxic to Rspo3 fusion organoids, whereas it had little activity against those that were Apc-deficient or β-catenin mutant (Fig. 1F-1H). However, Apc or β-catenin mutant organoids were sensitized to asparaginase by co-treatment with the GSK3α inhibitor BRD0705 (Fig. 1G-H), indicating that inhibition of GSK3α is sufficient for asparaginase sensitization.

Asparaginase Sensitization is Mediated by WNT-Dependent Stabilization of Proteins

We then asked how WNT pathway activation induces sensitivity to asparaginase. The E. coli derived asparaginase we utilized has potent asparaginase activity, and also degrades glutamine with lower affinity (approximately 2% of asparaginase activity) (37). Thus, we first assessed whether WNT signaling represses expression of relevant amino acid metabolic enzymes or transporters. However, we found that treatment with WNT-activating ligands, the pan-GSK3 inhibitor CHIR-99021, or the GSK3α-selective inhibitor BRD0705 had no consistent effect on expression of asparagine synthetase, glutamine synthetase, or of relevant amino acid transporters (38) (Supplementary Fig. S2A-F).

We previously showed that drug-resistant leukemias tolerate asparaginase therapy by relying on GSK3-dependent protein ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation as a catabolic source of asparagine. This adaptive response is blocked by WNT-dependent stabilization of proteins (WNT/STOP) (21), a β-catenin independent branch of WNT signaling that inhibits GSK3-dependent protein degradation (23,25,39). Consistent with the β-catenin independence of asparaginase sensitivity, we found that the three approaches we used to trigger asparaginase sensitivity (WNT-activating ligands, the pan-GSK3 inhibitor CHIR-99021, or selective GSK3α inhibition; see Fig. 1) had disparate effects on activation of β-catenin (Supplementary Fig. S3) in SW480 cells, which express an APC allele that is partially but not completely impaired in its ability to inhibit β-catenin (29,36).

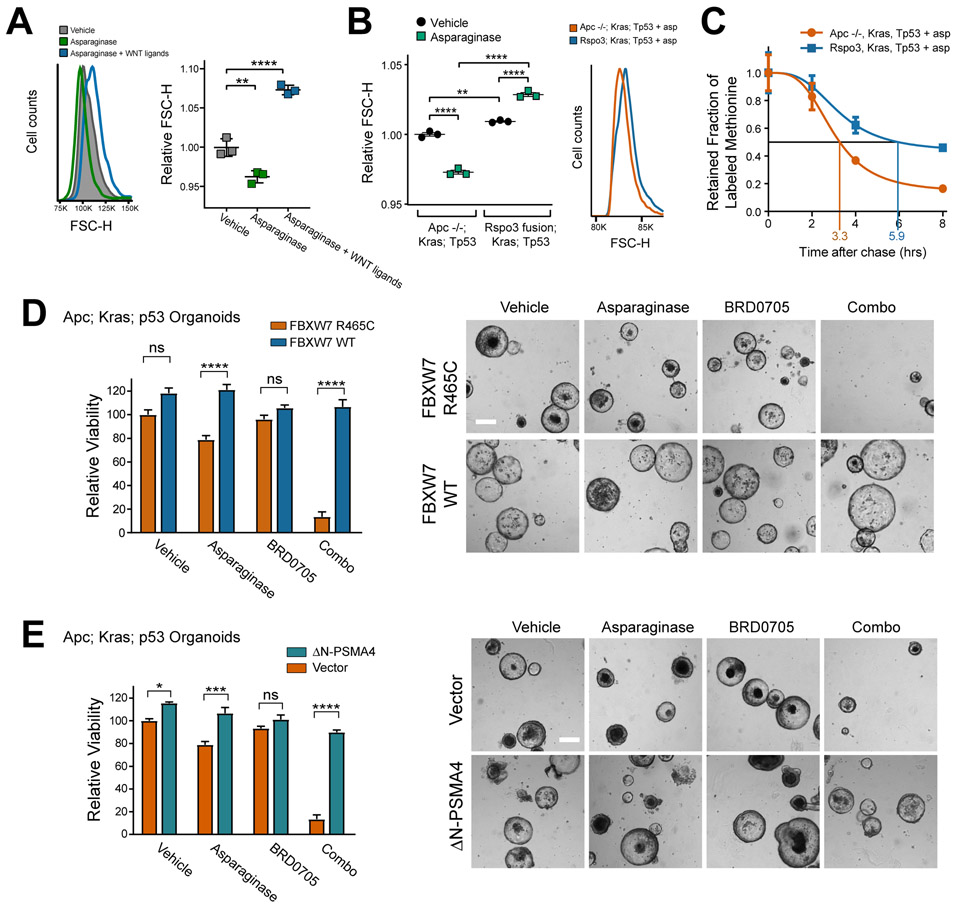

To assess whether these perturbations activate WNT/STOP, we focused on its cellular hallmarks, which are an increase in cell size and an increase in total cellular protein half-life (25). Our model is that these effects should be particularly striking in the context of asparaginase therapy, when catabolic protein degradation is mediating asparaginase resistance. Indeed, we found that asparaginase therapy significantly decreased cell size in the human CRC cell line HCT15, and this effect was reversed by treatment with WNT-activating ligands (Fig. 2A). Asparaginase also reduced cell size in Apc-deficient; Kras; p53 mutant mouse intestinal organoids, and this effect was blocked in organoids expressing an Rspo3 fusion (Fig. 2B). We also asked whether expression of an Rspo3 fusion increases total cellular protein half-life in organoids, using a pulse-chase experiment with the methionine analog azidohomoalanine (AHA). During the pulse period, there was no significant difference in the rate of labelled methionine incorporation in Rspo3 versus Apc deficient organoids (Supplementary Fig. S4). However, total cellular protein half-life was increased by approximately 1.8-fold in Rspo3 fusion versus Apc deficient organoids in the context of asparaginase therapy (Fig. 2C). To test whether WNT ligand-induced sensitization to asparaginase is mediated by WNT/STOP, we first leveraged the fact that overexpression of the E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXW7 restores the degradation of a subset of proteins stabilized by WNT-induced inhibition of GSK3 (25). We found that the toxicity of asparaginase combined with the GSK3α inhibitor BRD0705 to Apc-mutant organoids was reversed by overexpression of wild-type FBXW7, but not by an FBXW7 R465C point mutant allele that is impaired in its ability to bind its protein substrates (Fig. 2D) (40). Additionally, the toxicity of this combination was reversed by expression of a hyperactive mutant of the proteasomal subunit PSMA4 (Fig. 2E), which directly stimulates proteasomal degradation of a range of proteasomal substrates (41). Thus, activation of WNT/STOP induces asparaginase sensitization in CRC.

Figure 2. WNT-induced sensitization to asparaginase is mediated by WNT/STOP.

A, HCT15 cells were treated with vehicle or asparaginase (100 U/L) together with human RSpondin3 (75 ng/ml) and WNT3A protein (100 ng/ml) (referred to collectively as WNT ligands here) for 10 days. Cell size was assessed by forward scatter height (FSC-H) by flow cytometry (left). Scatter plot depicts results of individual biologic replicates, with horizontal bars indicating mean, and error bars indicating SEM (right). Differences between groups were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s adjustment for multiple comparisons.

B, Mouse intestinal organoids of the indicated genotypes were treated with vehicle or asparaginase (100 U/L), and cell size was assessed by forward scatter height (FSC-H) by flow cytometry on a BD FACS DIVA instrument. Scatter plots (left) depict results of individual biologic replicates, with horizontal bars indicating mean, and error bars indicating SEM. Differences between groups were assessed by two-sided ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons. Histograms (right) show results from a representative organoid of the indicated genotype treated with asparaginase.

C, Mouse intestinal organoids of the indicated genotypes were incubated with a pulse of the methionine analog 5-azidohomoalanine (AHA) for 18 hrs. Organoids were then released from AHA and treated with asparaginase (100 U/L) during the chase period. The degree of AHA label retention was assessed by flow cytometry at the indicated timepoints. Results are normalized to time 0 for each condition. See also Supplementary Fig. S2. Error bars indicate SEM.

D, Apc deficient; Kras; p53 organoids were cultured in basal medium, transduced with the indicated constructs and treated with vehicle, asparaginase (100 U/L), BRD0705 (1 μM) or combo (100 U/L asparaginase + 1 μM BRD0705) for 10 days. Viability was assessed as in (1G). Images were taken from a representative of three experiments. Scale bar, 100 μm. Differences between groups were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons.

E, Apc deficient; Kras; p53 organoids were cultured in basal medium, transduced with the indicated constructs and treated with vehicle, asparaginase (100 U/L), BRD0705 (1 μM) or combo (100 U/L asparaginase + 1 μM BRD0705) for 10 days. Viability was assessed as in (1G). Images were taken from a representative of three experiments. Scale bar, 100 μm. Differences between groups were analyzed using a one-way ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons.

* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01; *** p ≤ 0.001, **** p ≤ 0.0001, n.s., p > 0.05.

All error bars represent SEM.

If WNT/STOP activation induces sensitivity to asparaginase by impairing access to amino acids via catabolic protein degradation, then the toxicity of this combination should be rescued by replenishing the relevant amino acid(s). The asparaginase used in our studies (pegaspargase) is a PEGylated form of E. coli asparaginase, which has potent asparaginase activity and low but not absent glutaminase activity (37). Treatment of HCT15 cells with asparaginase led to profound depletion of asparagine, but had no significant effect on glutamine levels (Supplementary Fig. S5). We then asked whether cell death in response to GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase is caused by depletion of asparagine. HCT15 CRC cells were transduced with a GSK3α-targeting shRNA, treated with asparaginase, and we then added back a 10-fold excess of asparagine, glutamine, or vehicle control every 12 hours. This revealed that replenishing asparagine completely rescued CRC cells from the toxicity of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase (Supplementary Fig. S6). By contrast, adding glutamine alone had no effect, and the combination of asparagine and glutamine was no better than asparagine alone. Thus, the combination of WNT/STOP activation and asparaginase is toxic to CRC cells due to depletion of asparagine.

To gain insights into the biologic basis for the tumor-selective toxicity of this combination, we first assessed expression of asparagine synthetase and glutamine synthetase, but found no differences in their basal expression levels in normal versus malignant intestinal cells (Supplementary Fig. S7). We then leveraged an allelic series of mouse intestinal organoids that were either wild-type, had a single WNT-activating mutation of Apc or Rspo3 without other oncogenic mutations, or had these WNT-activating mutations in combination with a Kras-activating (G12D) and a p53-inactivating mutation. Treatment with the combination of asparaginase and GSK3α inhibition revealed little toxicity to wild-type organoids or to those harboring single WNT-activating mutations of either Apc or Rspo3, but the combination was significantly more toxic to those that also had Kras and p53 mutations (Supplementary Fig. S8A-C). Kras activation and p53 loss can both negatively regulate autophagy (42-44), raising the possibility that normal cells may tolerate asparagine starvation by relying on autophagy-mediated protein degradation as an alternative catabolic source of asparagine. This adaptive response may be impaired in CRC cells as a result of oncogenic mutations. To assess this possibility, we first measured levels of the autophagy marker P62 (also known as SQSTM1) by Western blot analysis in APC-deficient organoids that were either wild-type or mutant for Kras and p53. P62 is degraded by autophagy, thus levels of this protein are inversely correlated with the rate of autophagy (45). P62 levels were markedly increased in Kras/p53 mutant organoids, with or without asparaginase therapy, suggesting that these mutations impair autophagy in CRC cells (Supplementary Fig. S8D). Moreover, treatment with inhibitors of lysosomal protein degradation, which block autophagy-induced protein degradation (45), had no effect on sensitivity to GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase in CRC cells, but did significantly sensitize CCD841 cells derived from normal human intestinal epithelium (Supplementary Fig. S8E-G). Inhibiting lysosomal protein degradation blocks not only from autophagy but also macropinocytosis, which provides an alternative catabolic source of amino acids via endocytosis and degradation of extracellular proteins (46,47). To distinguish these possibilities, we used shRNA knockdown of Beclin-1 to inhibit autophagy genetically (45), and the small molecule EIPA as a selective inhibitor of macropinocytosis (46,48). This revealed that Beclin-1 knockdown phenocopied the ability of lysosomal protein degradation inhibitors to stimulate asparaginase sensitivity in CCD841 cells, whereas inhibiting pinocytosis with EIPA had a more modest effect (Supplementary Fig. S8H-J). These data suggest that normal cells rely primarily on autophagy as an alternative catabolic source of asparagine to tolerate asparaginase therapy, an adaptive response impaired in CRC cells.

Therapeutic Activity of Asparaginase in CRCs with Upstream WNT Pathway Mutations

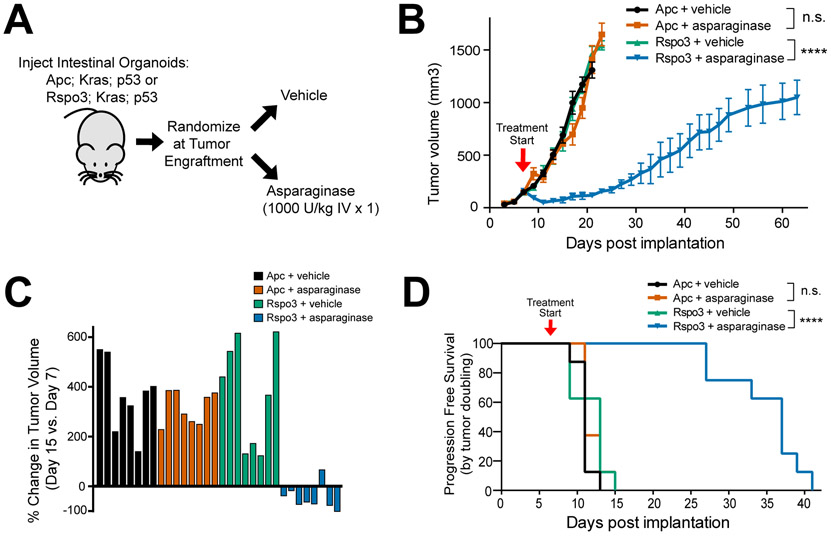

We then asked whether asparaginase has selective in vivo toxicity to CRCs with “upstream” WNT pathway mutations that stimulate WNT-induced signal transduction upstream of GSK3, which inhibits GSK3 (22-24). We generated subcutaneous tumors in immunodeficient nude mice injected with triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids that had Kras and p53 mutations, together with either Apc deficiency or an Rspo3 fusion. Once tumors engrafted (defined as growth to a volume >100 mm3), mice were randomized to treatment with vehicle or a single dose of asparaginase (Fig. 3A). Asparaginase had little effect on Apc-deficient tumors, but had significant therapeutic activity against Rspo3 fusion tumors. Indeed, asparaginase therapy not only markedly delayed disease progression in Rspo3 fusion tumors (Fig. 3B), but also induced tumor regression in most treated mice (Fig. 3C), and prolonged progression-free survival (Fig. 3D), without inducing appreciable weight loss (Supplementary Fig. S9).

Figure 3. Therapeutic Activity of Asparaginase in CRCs with Upstream WNT Pathway Mutations.

A, Experimental schema. Triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids with mutations of p53, Kras, and either an Rspo3 fusion or Apc deficiency were injected subcutaneously into male nude mice (n=8 per group). Once tumor engraftment was confirmed (>100 mm3 tumor volume), mice were randomized into groups and treated with vehicle or asparaginase (1,000 U/Kg x 1 dose).

B, Tumor volumes of mice injected with intestinal organoids in the experiment shown in (A). Treatment start is denoted by the arrowhead on the graph and tumor volumes were assessed every other day by caliper measurements. Significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons, for tumor volume on day 15. Error bars represent SEM. **** p ≤ 0.0001. n.s., p > 0.05.

C, Waterfall plots of % change in tumor volume at post-implantation day 15 versus the pre-treatment measurement on day 7 from the experiment shown in (A); each bar represents an individual mouse.

D, Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival analysis of mice injected with indicated organoids and treated with vehicle or asparaginase from the experiment shown in (A). Progression-free survival was defined by time to death or doubling of tumor volume. Significance was assessed by log rank test. **** p ≤ 0.0001. n.s., p > 0.05.

We noted that the Rspo3 fusion tumors progressed approximately 2 weeks after the asparaginase dose, which coincides with the waning of asparaginase activity following a single dose in mice (49). To distinguish whether tumor progression reflected loss of asparaginase activity or the development of resistance, mice with Rspo3;Kras;p53 tumors were re-challenged with a second dose of asparaginase after tumor re-growth, which retained activity (Supplementary Fig. S10A). Furthermore, treatment of a cohort of mice engrafted with new Rspo3; Kras; p53 fusion tumors using three doses of asparaginase dosed every 12 days revealed that repeated asparaginase dosing can provide sustained disease control (Supplementary Fig. S10B).

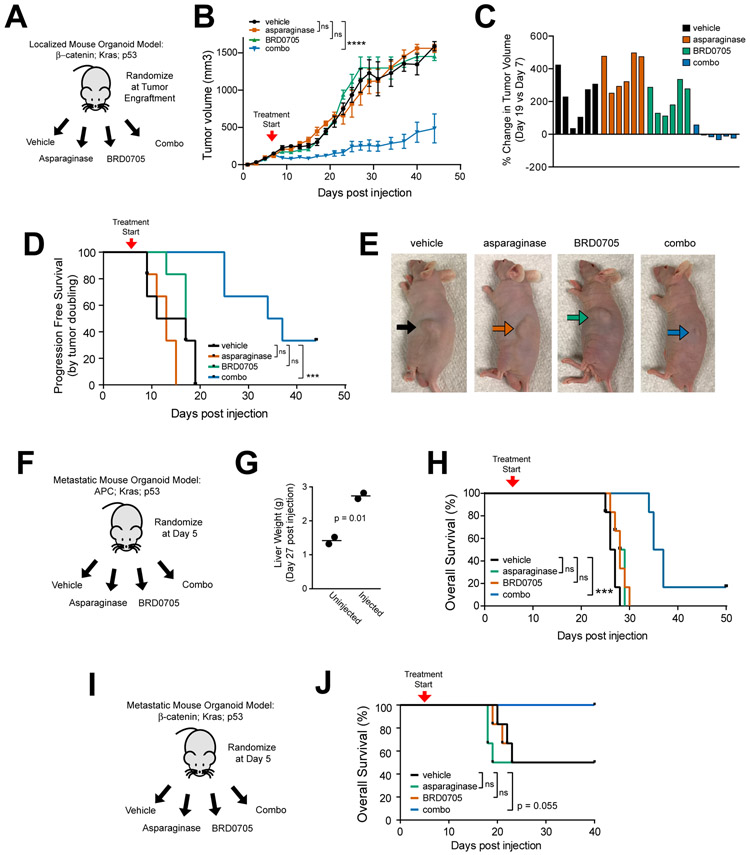

GSK3α Inhibition and Asparaginase for CRCs with APC or β-catenin Mutations

Our model predicted that tumors with WNT pathway mutations that selectively activate β-catenin without directly inhibiting GSK3 should exhibit in vivo asparaginase resistance, unless GSK3α was also inhibited. To test this prediction, we began by generating subcutaneous tumors from mouse intestinal organoids harboring a β-catenin activating (S33F) mutation (36), as well as Kras and p53 mutations. At the time of tumor engraftment, mice were randomized to treatment with vehicle, asparaginase, the GSK3α inhibitor BRD0705, or asparaginase in combination with BRD0705 (Fig. 4A). These β-catenin mutant tumors proved refractory to monotherapy with either asparaginase or BRD0705, despite effective inhibition of GSK3α autophosphorylation by BRD0705 (Supplementary Fig. S11A). However, the combination had significant activity (Fig. 4B-E).

Figure 4. GSK3α Inhibition and Asparaginase for CRCs with APC or β-catenin Mutations.

A, Experimental schema. Triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids with an activating β-catenin mutation, together with mutations of Kras and p53, were injected subcutaneously into male nude mice (n=6 per group). Once tumor engraftment was confirmed (>100 mm3 tumor volume), mice were randomized and treated with vehicle, asparaginase 1000 U/Kg x 1 dose, BRD0705 15 mg/kg every 12 hours x 21 days or both asparaginase and BRD0705 in combination (combo).

B, Tumor volumes of mice with β-catenin; Kras; p53 mutant tumors treated as in (A). Treatment start is denoted by the arrowhead on the graph. Significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons, for tumor volume on day 19. Error bars represent SEM. **** p ≤ 0.0001. n.s., p > 0.05.

C, Waterfall plots showing % change in tumor volume over the first 14 days of treatment. Each bar represents an individual mouse.

D, Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival analysis of mice injected with indicated organoids and treated with vehicle or asparaginase from the experiment shown in (A). Progression-free survival was defined by time to death or doubling of tumor volume. Significance was assessed by log rank test. *** p ≤ 0.001. n.s., p > 0.05.

E, Representative images of anesthetized mice taken on day 14 post treatment from the experiment shown in (A). Arrows point to the location of the subcutaneous tumor.

F, Design of the experiment testing therapeutic activity in a liver-metastatic model of Apc; Kras; p53 triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids. Treatment began on day 5 post-injection, and was performed as described in (A).

G, Liver weights of mice harvested to assess metastatic burden to the liver. Each data point represents an individual mouse. Significance was assessed by a two-sided Welch t-test.

H, Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival from mice in the experiment shown in (F) (n = 6 mice per group). Significance was assessed by log-rank test. *** p ≤ 0.001., *p ≤ 0.05 n.s., p > 0.05.

I, Design of the experiment testing therapeutic activity in a liver-metastatic model of β-catenin; Kras; p53 triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids. Treatment began on day 5 post-injection, and was performed as described in (A).

J, Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival from mice in the experiment shown in (I) (n = 6 mice per group). Significance was assessed by log-rank test. *** p ≤ 0.001., *p ≤ 0.05 n.s., p > 0.05.

We then asked whether GSK3α inhibition would induce asparaginase sensitization in the setting of metastatic CRC, which most commonly involves the liver (50,51). Thus, we leveraged a model of liver-metastatic CRC generated via intrasplenic injection of genetically engineered mouse intestinal organoids (52). Triple-mutant mouse intestinal organoids harboring a WNT-activating mutation of either Apc, β-catenin or Rspo3, together with mutations of Kras and p53, were injected intrasplenically into distinct cohorts of mice. Five days after injection, mice were randomized to treatment with either vehicle, asparaginase, the GSK3α inhibitor BRD0705, or both drugs in combination (Fig. 4F). Metastatic engraftment to the liver was assessed by measuring liver weights in sentinel mice, which were euthanized 28 days post-injection with Apc; Kras; p53 mutant organoids (Fig. 4G). We then followed mice in each treatment cohort for survival. While the Rspo fusion organoids failed to engraft in any mouse (data not shown), Apc; Kras; p53 organoids yielded efficient tumor engraftment, and the combination of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase had significant therapeutic activity in this model (Fig. 4F-H). β-catenin; Kras; p53 organoids yielded tumor engraftment in approximately 50% of injected mice, which impaired our statistical power, nevertheless all of the mice treated with the combination of BRD0705 and asparaginase were alive and well at day 40 post-injection, whereas half of mice in each other treatment condition succumbed to disease by day 25 (Fig. 4I-J).

Therapeutic Activity of GSK3α Inhibition and Asparaginase in CRC Patient-Derived Xenografts

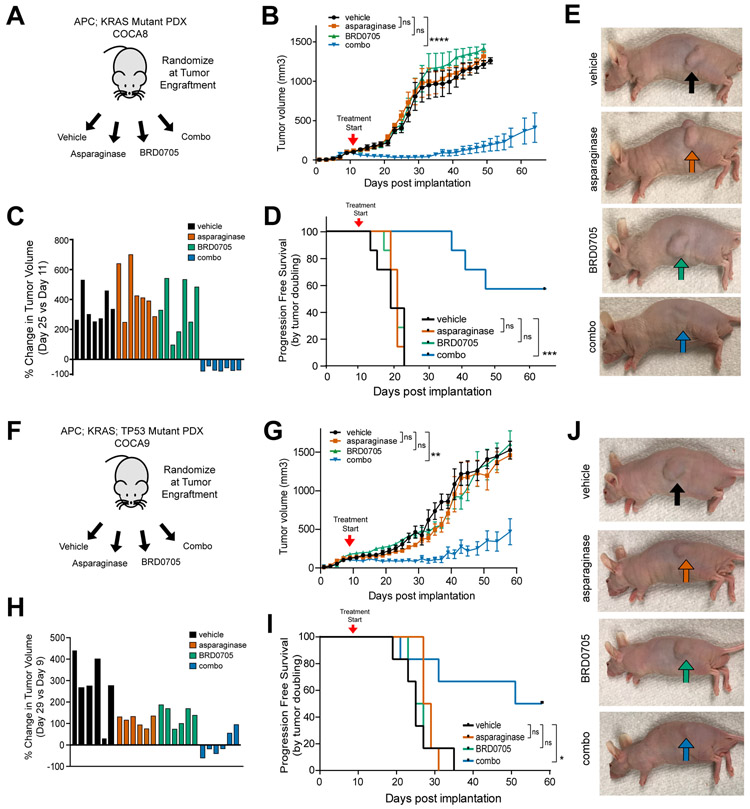

We then asked whether GSK3α inhibition could induce asparaginase sensitization in vivo using patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models of APC-mutant CRC. We engrafted nude immunodeficient mice with a human patient-derived CRC xenograft termed COCA8, which had a biallelic APC mutation as well as a KRAS activating mutation (Table S1). Following tumor engraftment, mice were randomized to treatment with vehicle, asparaginase (1000 U/kg x 1 dose), the GSK3α inhibitor BRD0705 (15 mg/kg every 12 hours x 21 days), or the combination of asparaginase and BRD0705 (Fig. 5A). We confirmed that BRD0705 treatment inhibited GSK3α in vivo (Supplementary Fig. S11B), as assessed by GSK3 autophosphorylation (53). The combination treatment was well tolerated, with no appreciable weight loss and no clinical or laboratory evidence of common asparaginase toxicities such as hepatic or pancreatic toxicity (Supplementary Fig. S12A-H), although these immunocompromised mice were ill-suited to assess risk of hypersensitivity reactions to asparaginase. Monotherapy with asparaginase or BRD0705 had no significant therapeutic activity, but treatment with the combination of asparaginase and BRD0705 had a potent effect on tumor growth, including tumor regression in all treated mice, and significant prolongation in progression-free survival (Fig. 5B-E). To confirm the generalizability of these findings, we leveraged a distinct PDX model, termed COCA9, which had mutations of APC, KRAS and TP53 (Table S1). Consistent with predictions from our model, monotherapy with either asparaginase or BRD0705 had little activity, whereas both drugs in combination had significant therapeutic activity, as assessed by tumor size and progression-free survival (Fig. 5F-J).

Figure 5. Activity of GSK3α Inhibition and Asparaginase in APC-Mutant Patient-Derived Xenografts of CRCs.

A, Experimental schema. A human CRC PDX harboring a biallelic APC mutation was implanted subcutaneously into male nude mice (n=7 per group). Mice were treated at the time of tumor engraftment (>100 mm3) with vehicle, asparaginase 1000 U/Kg x 1 dose, BRD0705 15 mg/kg every 12 hours x 21 days or both asparaginase and BRD0705 in combination (combo).

B, Tumor volumes of mice implanted with the human CRC PDX in the experiment shown in (A). Arrowhead denotes treatment start. Tumor volumes were assessed every other day by caliper measurements. Significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA comparing tumor volumes on day 25, with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparison testing. Error bars represent SEM. *** p ≤ 0.001; n.s., p > 0.05.

C, Waterfall plot of % change in tumor volume at post-implantation day 25 versus the pre-treatment measurement on day 11 from the experiment shown in (A); each bar represents an individual mouse.

D, Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curve of mice treated with asparaginase, BRD0705 or combo. Significance was assessed by log rank test. *** p ≤ 0.001; n.s., p > 0.05.

E, Representative images of mice implanted with the APC-mutant CRC PDX from the experiment shown in (A). Images were taken 30 days post treatment from mice anesthetized with isoflurane.

F, Experimental design using a distinct PDX model, COCA9, harboring a monoallelic APC mutation. Randomization and treatment were performed as in (A).

G, Tumor volumes of mice from the experiment depicted in (F). Arrowhead denotes treatment start. Tumor volumes were assessed every other day by caliper measurements. Significance was assessed by two-way ANOVA comparing tumor volumes on day 25, with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparison testing. Error bars represent SEM. ** p ≤ 0.01; n.s., p > 0.05.

H, Waterfall plots of % change in tumor volume at post-implantation day 29 versus day 9. Each bar represents an individual mouse.

I, Kaplan-Meier progression-free survival curve of mice from the experiment shown in (F). Significance was assessed via log-rank test.

J, Representative images of mice implanted with the APC-mutant CRC PDX from the experiment shown in (F). Images were taken 30 days post treatment from mice anesthetized with isoflurane.

DISCUSSION

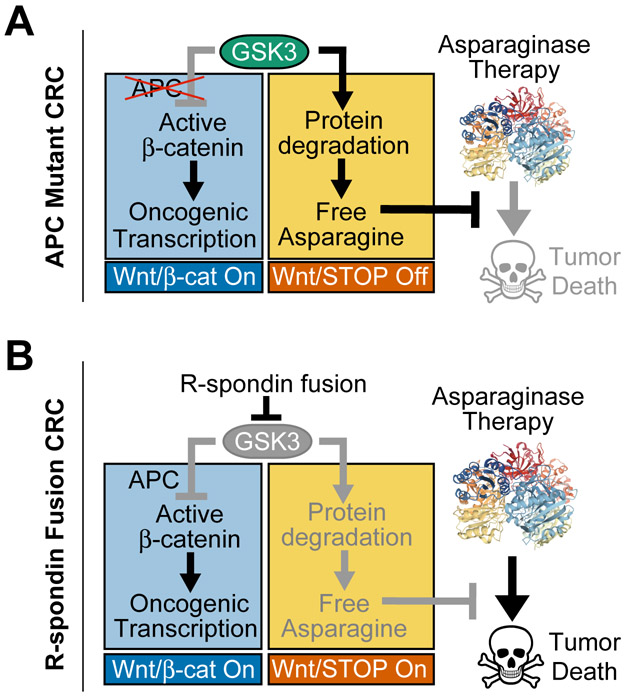

We show here that the WNT-induced therapeutic vulnerability to amino acid starvation can be exploited for CRC therapy (Fig. 6A-B). Inhibition of GSK3 is a key mediator of WNT-induced signal transduction (22-24), thus this kinase is predicted to be endogenously inhibited in a subset of CRCs as a consequence of mutations that stimulate WNT ligand-induced pathway activation. Based on our previous work in leukemia, we predicted that these cases would be selectively sensitized to asparaginase. Indeed, we found that CRCs with RSPO3 fusions, a recurrent oncogenic alteration in CRC that potentiates WNT ligand activity (8-10,13,54-56), were profoundly sensitive to asparaginase monotherapy. Our model predicts that CRCs with other upstream WNT-activating mutations, such as RSPO2 fusions or mutations of the RSPO receptor RNF43, should also be asparaginase sensitive, so long as these mutations result in effective inhibition of GSK3. These findings also suggest the need to test asparaginase in other tumor types with mutations predicted to stimulate WNT-induced inhibition of GSK3, such as RNF43-mutant pancreatic, endometrial and gastric cancers (11,57,58), and G9a mutant melanomas (59).

Figure 6. Model for Therapeutic Interaction of WNT Pathway Activation and Asparaginase.

A, Our model is that APC mutations selectively activate the β-catenin branch of WNT signaling downstream of GSK3. Thus, the ability of GSK3 to phosphorylate a large number of cellular proteins, leading to their ubiquitination and degradation, is unperturbed (WNT/STOP off). This degradation serves as a catabolic source of free asparagine, which prevents asparaginase-induced tumor death. Asparaginase structure is from PDB: 2HIM.

B, In R-spondin fusion CRC, WNT signaling is activated upstream of GSK3, which results in activation of both the WNT/β-catenin and the WNT-dependent stabilization of proteins (WNT/STOP) branches of this pathway. Activation of WNT/STOP inhibits protein degradation, limiting cellular asparagine availability, and triggering a unique vulnerability to its enzymatic degradation by asparaginase. Thus, asparaginase therapy induces tumor death in R-spondin fusion CRC. In APC-mutant CRC, selective inhibition of GSK3α phenocopies this effect.

We found that APC-mutant CRCs were refractory to asparaginase monotherapy, unless GSK3 function was inhibited in these tumors. Selective inhibition of GSK3α was sufficient for this effect. While the ATP-binding pockets of GSK3α and GSK3β differ by a single amino acid, isoform-selective inhibitors of GSK3α can be developed (35), which provides a strategy to leverage this therapeutic interaction for the majority of patients with CRC, who have mutations of APC or β-catenin. Selective inhibition of GSK3α is expected to provide a significant safety advantage because GSK3α and GSK3β are redundant for regulation of β-catenin in several experimental contexts (33-35), and GSK3β is the predominant β-catenin regulator in some contexts (60). Thus, small molecules that inhibit both GSK3α and GSK3β are expected to have toxicity due to widespread activation of β-catenin signaling, which is oncogenic. Moreover, GSK3β deficiency is embryonic lethal due to liver degeneration (61), and the liver is a target organ of asparaginase toxicity (62). By contrast, GSK3α-deficient mice are viable and have no known tumor predisposition (63). Thus, we expect isoform-selective inhibition of GSK3α to be better tolerated in combination with asparaginase.

We found that the combination of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase was potently toxic to oncogenically transformed CRC cells, but had little toxicity to normal intestinal cells or to mouse intestinal organoids harboring a single WNT-activating mutation. By contrast, this combination was more toxic to intestinal organoids that also had mutations of Kras and p53. These findings suggest that KRAS and TP53 mutations impair one or more adaptive responses that allow normal cells to tolerate the combination of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase. One possibility was autophagy, which allows cells to tolerate starvation via lysosomal degradation of organelles and macromolecules (45), and which can be negatively regulated by KRAS activation and TP53 loss (42-44). Indeed, small molecule inhibitors of lysosomal protein degradation, which block autophagy-induced amino acid release, or knockdown of the autophagy factor Beclin-1, sensitized cells derived from normal human intestine to the toxicity of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase. These findings suggest that the ability of normal cells to tolerate asparaginase is in part due to their ability access asparagine via autophagy. However, additional factors may also contribute to the resistance of normal cells to asparagine starvation, such as checkpoints that can trigger proliferative arrest in response to asparagine depletion or an improved capacity for de novo asparagine synthesis. Defining the precise molecular mechanisms that account for the tumor-selective toxicity of this therapeutic combination is of interest for future investigation.

Taken together with our recent work in leukemia (21), our data indicate that GSK3α-dependent protein degradation is required for asparaginase resistance in colorectal cancer and in drug-resistant leukemia. Given that excessive protein degradation is likely to antagonize cell growth in nutrient-rich conditions, tumor cell fitness may be maximized by selective induction of protein degradation in response to amino acid starvation. Deciphering the molecular regulation of this adaptive response will require additional investigation. These studies lead to the unexpected conclusion that mechanisms of intrinsic asparaginase resistance in solid tumors can overlap with those of acquired resistance in leukemia, and are fundamentally distinct from those that allow normal cells to tolerate asparaginase. Given that the therapeutic interaction of GSK3α inhibition and asparaginase is selectively toxic to tumors derived from cellular lineages that are as diverse as intestinal epithelium and hematopoietic cells (21), this approach could have meaningful therapeutic activity in a broad range of human cancers, so long as these rely on GSK3α-dependent protein degradation to tolerate treatment with asparaginase.

METHODS

Drugs

All asparaginase experiments were performed using pegaspargase (Oncaspar, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Lexington, MA), an FDA-approved PEGylated form of E. coli asparaginase. BRD0705 and BRD3731 were synthesized as described (35). CHIR-99021 was obtained from Selleckchem. Bafilomycin, chloroquine, EIPA and ammonium chloride were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Patient-Derived Xenografts

Specimens were collected from patients with APC-mutant colon cancer [per methods described in (64)], with written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approval of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Institutional Review Board. Patient-derived xenografts (PDXs) were generated by subcutaneous implanted into immunodeficient mice, as described (64). Mouse studies were performed in accordance with all regulatory standards and approved by the Boston Children’s Hospital Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. PDX models were genotyped using a clinical genotyping assay based on exon/fusion capture and next-generation sequencing, as described (65).

Cell Lines, Cell Culture and Organoid Culture

293T cells, colorectal cancer cell lines and normal colon cells were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) or DSMZ (Braunschweig, Germany), and cultured in DMEM, RPMI-1640 or Leibovitz’s L-15 media (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% or 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) or TET system approved FBS (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 37°C, 5% CO2.

Organoids carrying Ptprk-Rspo3 fusions and LSL-KrasG12D were derived from transgenic mice (9). Ptrpk-Rspo3 rearrangement was selected by culturing organoids without exogenous R-Spondin for 7 days, and validated by sequencing of the Ptprk-Rspo3 fusion junction. Targeted Apc (Q884X) and Ctnnb1 (S33F) mutations were generated by base editing, as previously described (36). KrasG12D activation and p53 loss were induced by delivery of a Cas9-P2A-Cre lentivirus (66) and p53-targeting guide RNA (67). For selection of p53 loss, organoids were cultured with 5 μM Nutlin-3 for 7 days, and KrasG12D activation was indirectly selected during this selection. P53 loss was validated by sgRNA targeting site sequencing and Western Blot, and KrasG12D activation was validated by RNA sequencing.

For maintenance of mouse intestinal organoids in culture, organoids were resuspended in Matrigel composed of 25% advanced DMEM/F12 (Gibco) and 75% Matrigel (Corning), and after the Matrigel polymerized, organoids were cultured in organoid basal medium supplemented with growth factors (complete organoid growth medium). Organoid basal medium was advanced DMEM/F-12 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 2 mM L-Glutamine (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO), 1 mM N-acetylcysteine (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO) and 10 mM HEPES (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO). Apc-deficient organoids were cultured in complete large intestinal organoid growth medium, consisting of organoid basal medium supplemented with murine Wnt3a (50ng/ml, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), murine Noggin (50ng/ml), murine EGF (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, 50ng/ml) and human R-Spondin 1 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), as previously described (68). Rspo3-fusion organoids were cultured in complete small intestinal organoid growth medium, consisting of organoid basal medium supplemented with murine Noggin (50 ng/ml), murine EGF (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, 50ng/ml) and human R-Spondin 1 (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN), as previously described (68). Because our hypothesis was that WNT and R-spondin ligands would induce asparaginase sensitivity, all experiments involving asparaginase treatment were performed using organoid basal medium, without growth factor supplementation.

Cell line identities were validated using STR profiling at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory (most recently in December 2018), and mycoplasma contamination was excluded using the MycoAlert Mycoplasma Detection Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Lonza, Portsmouth, NH; most recently in November 2018).

Mice

Nude (J:NU) mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME; Stock # 0007850). 7 to 9 week old male nude mice were used for experiments and littermates were kept in individual cages. Mice were randomly assigned to experimental groups and handled in strict accordance with Good Animal Practice as defined by the Office of Laboratory Animal Welfare. All animal work was done with Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approval (protocol # 18-09-3784R).

Lentiviral Transduction of Colon Cancer Cell Lines

Lentiviruses were generated by co-transfecting pLKO.1 plasmids of interest together with packaging vectors psPAX2 (a gift from Didier Trono; Addgene plasmid # 12260) and VSV.G (a gift from Tannishtha Reya; Addgene plasmid # 14888) using OptiMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and and Fugene (Promega, Madison, WI), as previously described (69).

Lentiviral infections were performed by spinoculating colorectal cancer cell lines with virus-containing media (1,500 g x 90 minutes) in the presence of 8 μg/ml polybrene (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Selection with antibiotics was started 24 hours after infection with puromycin (1 μg/ml for a minimum of 48 hours; Thermo Fisher Scientific), or blasticidin (15 μg/ml for a minimum of 5 days; Invivogen).

Lentiviral Transduction of Mouse Intestinal Organoids

Prior to lentiviral transduction, a full 0.95 cm2 well of mouse intestinal organoids was harvested by pipetting up and down the Matrigel and complete organoid growth medium. Briefly, disrupted organoids were centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes and the cell pellet was resuspended in 250 μl of cold 0.25% trypsin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated for 5 minutes at 37°C. Subsequently, trypsin was inactivated by adding 750 μl complete organoid growth medium and centrifuged (300 g x 5 minutes). Cells were resuspended in 250 μl of concentrated lentivirus supplemented with 8 μg/ml polybrene (Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). For lentiviral infection, the organoid-virus mixture was incubated for 12 hours at 37°C, 5% CO2. Subsequently, 750 μl of complete organoid growth medium was added to the well, and the mixture centrifuged at 300g for 5 minutes. The pellet was resuspended in 40 μl of ice-cold matrigel, and 250 μl of complete organoid growth medium was added to each well after matrigel solidification. Selection with antibiotics was started 24 hours after infection.

shRNA and Expression Plasmids

The following lentiviral shRNA vectors in pLKO.1 with puromycin resistance were generated by the RNAi Consortium library of the Broad Institute, and obtained from Sigma-Aldrich: shLuciferase (TRCN0000072243), shGSK3α#1 (TRCN0000010340), shGSK3α#4 (TRCN0000038682), shGSK3β#2 (TRCN0000039564), shGSK3β#6 (TRCN0000010551).

Expression constructs expressing wild-type FBXW7 (also known as CDC4) or its R465C mutant were synthesized by gene synthesis, and cloned into the pLX304 lentiviral expression vector by GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD). A hyperactive open-gate mutant of the human proteasomal subunit PSMA4, termed ΔN-PSMA4, was designed by deleting the cDNA sequences encoding amino acids 2 to 10 (SRRYDSRTT) of PSMA4 isoform NP_002780.1 (encoded by the transcript NM_002789.6), based on the data of Choi and colleagues (41). This ΔN-PSMA4 coding sequence was synthesized by gene synthesis, and cloned into the pLX304 lentiviral expression vector in-frame with the C-terminal V5 tag provided by this vector, by GeneCopoeia (Rockville, MD).

Assessment of Chemotherapy Response and Apoptosis in Colon Cancer Cell Lines

Cells (100,000 per well) were seeded in 1 ml of complete growth medium in 12-well plates and incubated with chemotherapeutic agents or vehicle. Cells were split every 48 hours and cell viability was assessed by counting viable cells based on trypan blue vital dye staining (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Chemotherapeutic drugs included: asparaginase (pegaspargase, Shire, Lexington, MA), CHIR99021 (Selleckchem), recombinant human WNT3A protein (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN) and recombinant human R-Spondin3 protein (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). BRD0705 and BRD3731 were synthesized as described (35). Caspase 3/7 activity was assessed using the Caspase Glo 3/7 Assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Assessment of Chemotherapy Response in Mouse Intestinal Organoids

For assessment of chemotherapy response in mouse intestinal organoids, Apc-deficient and Rspo3 fusion organoids were cultured in organoid basal medium (in the absence of WNT3A, murine Noggin and human R-spondin1 protein). A full 0.95cm2 well of organoids was split into new wells, aiming to obtain approximately 25 organoids per well. Organoids were split according to previously published protocols (68). Matrigel and basal organoid medium were supplemented with vehicle or chemotherapeutic agents, and split every 48 hours. After 10 days in culture, total organoid numbers per wells were counted manually by light microscopy. Dying organoids were distinguished by the drastic change in organoid morphology with loss of epithelial integrity and impaired lumen formation. Organoids touching the edge of a well were excluded from counting. Microscopy was performed using an 100x objective on an Axio Imager A1 microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany), with images captured using a CV-A10 digital camera (Jai, Yokohama, Japan) and Cytovision software (Leica Biosystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Images were taken from a representative of three independent experiments and analyzed with ImageJ Software (70).

Assessment of Cell Size

Briefly, HCT15 cells (100,000 per well) were plated in 1 ml of complete growth medium, containing a final concentration of 100 U/L asparaginase or 100 ng/ml WNT3A ligand and 75ng/ml Rspo3 ligand in a 12-well format. Indicated organoids were seeded in 250 μl of organoid growth medium supplemented with 100 U/L of asparaginase. After 48 hours of treatment, forward scatter height (FSC-H) was assessed by flow cytometry on a Beckton-Dickinson (BD) LSR-III or a BD FACS DIVA instrument.

Assessment of Response to Autophagy Inhibition

Cells (100,000 per well) were plated in 1 ml of complete growth medium, supplemented with vehicle (PBS) or 100 U/L asparaginase and 1 μM BRD0705. Growth medium contained a final concentration of 100 nM bafilomycin (Sigma Aldrich), 10 μM chloroquine (Sigma Aldrich), or 20 mM ammonium chloride (Sigma Aldrich). Cells were split after 48 hours, and cell viability was assessed after 5 days of treatment by counting viable cells based on trypan blue vital dye staining (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was isolated using RNeasy kit (Qiagen) and cDNA was made using SuperScript III first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). qRT-PCR was performed using Power SYBR® Green PCR Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 7500 real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Primers used are described in Table S2.

Western Blot Analysis

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Merck Millipore) supplemented with cOmplete protease inhibitor (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and PhosSTOP phosphatase inhibitor (Roche). Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich) were mixed with 20 μg of protein lysate before being run on a 4–12% bis-tris polyacrylamide gel (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Blots were transferred to PVDF membrane (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and blocked with 5% BSA (New England Biolabs) in phosphate-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween (Boston Bioproducts, Ashland, MA) and probed with the following antibodies: Non-phospho (active) β-catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) antibody Non-phospho (Active) β-Catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) (D13A1) Rabbit mAb #8814(1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies #8814Phospho-β-Catenin (Ser33/37/Thr41) Antibody #9561), P62 antibody (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies #5114), phospho-GSK3 (Tyr279/216) (1:1000, Thermo Fisher #OPA1-03083), or GAPDH (1:1000, Cell Signaling Technologies #2118GAPDH (14C10) Rabbit mAb #2118). Detection of horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibodies (1:2000, Cell Signaling Technologies #7074S) with horseradish peroxidase substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was visualized using a BioRad GelDoc XR+ Imaging System (Hercules, California).

Assessment of Protein Stability

Protein degradation was assessed using a non-radioactive quantification of the methionine analog L-azidohomoalanine (AHA) AlexaFluor488 (Thermo Fisher), as previously described (71). Briefly, organoids were seeded in 250 μl of methionine-free DMEM. After 30 minutes, the pulse step was performed by replacing this media with 250 μl DMEM supplemented with AHA at a final concentration of 50 μM for 18 hr. In the chase step, cells were released from AHA by replacing media with DMEM containing 10x L-methionine for 2 hr. Subsequently, media was replaced with regular organoid growth medium and cells were treated with a final concentration of 100 U/L asparaginase, followed by fixation of cells. AHA labeled proteins were tagged using TAMRA alkyne click chemistry, and fluorescence intensity was measured by flow cytometry. A sample without AHA labeling but TAMRA alkyne tag was included as a negative control to account for background fluorescence.

Amino Acid Quantification

HCT15 cells (100,000 per well) were seeded in 1 ml of complete growth medium in a 12-well format. The growth medium was supplemented with final concentrations of 100 U/L asparaginase. After 24 hr of treatment, media was collected and stored at −80C until amino acid quantification.

For intracellular amino acid extraction, cells were harvested and resuspended in 0.16 M potassium chloride (Sigma Aldrich). After 10 minutes, a mix of leupeptin (1μM, Sigma Aldrich), Pepstatin (1μM, Sigma Aldrich), Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (1mM, Sigma Aldrich) and EDTA (1mM, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the suspension and incubated on ice for additional 10 minutes. Subsequently, cells were lysed by thaw-freeze cycling (15 min at −80C followed by 60 minutes at 4C). After 4 cycles, the suspension was deproteinized by adding sulfosalicylic acid (7mg/ml, Sigma Aldrich) and stored at −80C until amino acid quantification.

The entire amino acid profile was determined by means of liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS).

Rescue of Asparaginase Sensitization with Amino Acid Supplementation

HCT15 cells were transduced with shRNAs (100,000 per well) were seeded in 1 ml of complete growth medium, containing a final concentration of 100 U/L asparaginase (or PBS vehicle control) in a 12-well format. Growth medium (RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal bovine serum) was supplemented with L-asparagine (Sigma-Aldrich) at a final concentration of 3.78 mM (10X), L-glutamine at a final concentration of 20.5 mM (10X), or with both 10X asparagine and 10X glutamine. Every 12 hr, 500 μl of complete growth medium was removed and replaced with 500 μl fresh growth media, supplemented with the appropriate concentration of asparaginase. After 72 hr of treatment, viability was assessed by trypan blue viable cell staining.

In Vivo Drug Treatment of Subcutaneous Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) and Organoids

For implantation of APC mutant human CRC PDX, patient tumor material was collected in PBS and kept on wet ice for engraftment within 24 h after resection. Upon arrival, necrotic and supporting tissues were carefully removed using a surgical blade. Approximately 1mm x 1mm tissue fragments were implanted subcutaneously into the flank region of male nude mice, as described (64). For injection of intestinal organoids (Rspo3; p53; Kras, or Apc; p53; Kras), per mouse one full 9.5cm2 well of organoids was injected subcutaneously.

Treatment was started when tumors reached a volume of approximately 150mm3. For the APC mutant human CRC PDX, a single dose of asparaginase (1,000 U/kg) or PBS was injected by tail vein injection on day 1 of treatment, and BRD0705 (15 mg/kg) or vehicle was given every 12 hours for 21 days by oral gavage. Vehicle was formulated as previously described (35).

After start of treatment, body weight and tumor size were evaluated every other day. Tumor size was assessed by caliper measurements and the approximate volume of the mass was calculated using the formula (l × W × W) × (π/6), where l is the major tumor axis and w is the minor tumor axis. The response was determined by comparing tumor volume change at time t to its baseline: % tumor volume change = 100% × ((Vt – Vinitial) / Vinitial, as previously described (72). Mice were euthanized as soon as they reached a tumor volume of 1500 mm3, developed weight loss greater than 15% and/or showed signs of tumor ulceration. For Fig. 3B, 4B, 5D and 5G, the last recorded tumor size of mice that died due to tumor progression was used for volume plots until the last mouse of the treatment group reached a tumor volume of 1500 mm3.

To assess the potential hepatic or pancreatic toxicity of the combination of BRD0705 and asparaginase treatment, retro-orbital blood collections were performed, and liver function and pancreatic enzyme levels were measured in the Boston Children’s Hospital clinical laboratory.

In Vivo Drug Treatment of Metastatic Mouse Intestinal Organoids

For injection of intestinal organoids (Apc; p53; Kras), per mouse one full 9.5cm2 well of organoids was injected into the spleen, as previously described (73). Briefly, organoids were collected, resuspended in PBS, and kept on ice. Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and the left subcostal area was prepped with 70% ethanol and iodine. A left subcostal incision was made in line with the left ear through the skin and the peritoneum using scissors. The spleen was expressed by pulling the caudal aspect of the spleen through the incision using tweezers, and a total volume of 50 μl of organoids in PBS was slowly injected into the exposed part of the spleen. Subsequently, the spleen was placed back into the peritoneum by applying digital pressure. The peritoneum was closed with 2 sutures, and the skin incision was closed by applying one skin clip.

Five days post injection of organoids, treatment was started and consisted of one single dose of asparaginase (1,000 U/kg) or PBS given by tail vein injection on day 1 of treatment, and BRD0705 (15 mg/kg) or vehicle was given every 12 hours for 21 days by oral gavage.

After start of treatment, body weight was evaluated every other day. Mice were euthanized as soon as they developed weight loss greater than 15% and/or showed signs of disease progression. Mice were harvested for post mortem analysis of liver weights.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

For two-group comparisons of continuous measures, a two-tailed Welch unequal variances t-test was used. For 3-group comparisons, a one-way analysis of variance model (ANOVA) was performed and a Dunnett adjustment for multiple comparisons was used. For analysis of two effects, a two-way ANOVA model was constructed and included an interaction term between the two effects. Post-hoc adjustment for multiple comparisons for two-way ANOVA included Tukey-Kramer adjustment. The log rank test was used to test for differences in survival between groups, and the method of Kaplan and Meier was used to construct survival curves. Data shown as bar graphs represent the mean and standard error of the mean (s.e.m) of a minimum of 3 biologic replicates, unless otherwise indicated. All p-values reported are two-sided and considered as significant if <0.05.

Supplementary Material

SIGNIFICANCE.

Solid tumors are thought to be asparaginase-resistant via de novo asparagine synthesis. In leukemia, GSK3α-dependent protein degradation, a catabolic amino acid source, mediates asparaginase resistance. We found that asparaginase is profoundly toxic to CRCs with WNT-activating mutations that inhibit GSK3. Aberrant WNT activation can provide a therapeutic vulnerability in CRC.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kimberly Stegmaier, Daniel Bauer, Alex Kentsis, Scott Armstrong, Gabriela Zurek, Nikolaus Kuehn-Velten, Mark Kellogg, Timothy Hagan, Otari Chipashvili and Sung-Yun Pai for advice and discussion, and Meaghan McGuinness and Casey O’Brien for experimental assistance. This work was supported by NIH/NCI R01 CA193651, the Boston Children’s Hospital Translational Investigator Service, a Dana-Farber Cancer Institute Medical Oncology Translational Grant Award, and the ERA-NET Transcan/European Commission under the 7th Framework Programme (FP7). L.H. was supported by the German National Academic Foundation and the Biomedical Education Program. M.G. was supported by a Conquer Cancer Foundation of ASCO Career Development Award, the Project P-Fund, the Cancer Research UK C10674/A27140 Grand Challenge Award, and a Stand Up to Cancer Colorectal Cancer Dream Team Translational Research Grant (Grant Number: SU2C-AACR-DT22-17). Stand Up to Cancer is a division of the Entertainment Industry Foundation, and research grants are administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the scientific partner of SU2C. Research grants are administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, a scientific partner of SU2C. E.M.S was supported by a Medical Scientist Training Program grant from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32GM07739 to the Weill Cornell / Rockefeller / Sloan-Kettering Tri-Institutional MD/PhD Program, and an F31 Award from the NCI/NIH under grant number 1 F31 CA224800-01. K.N. was supported by NIH R01 CA205406 and DOD CA160344. A.G. was supported by a CHPA Investigatorship at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Conflicts of interests statement: Boston Children’s Hospital has filed patents on the subject matter of this publication. M. Giannakis receives research funding from Bristol-Myers Squibb and Merck. F. Wagner has consulted for a biotechnology company on a GSK3-related project, and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard has filed US patents US20160375006, WO2014059383 and WO2018187630 on BRD0705 and related GSK3 inhibitors. K. Ng has served as a consultant or on advisory boards for Tarrex, Genentech, Lilly, Bayer, and Seattle Genetics, and has received research funding from Pharmavite, Tarrex, Trovagene, Celgene, Genentech, and Gilead. L.E. Dow is a scientific advisor and holds equity in Mirimus Inc.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin 2019;69(1):7–34 doi 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Goding Sauer A, Fedewa SA, Butterly LF, Anderson JC, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin 2020;70(3):145–64 doi 10.3322/caac.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yaeger R, Chatila WK, Lipsyc MD, Hechtman JF, Cercek A, Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Clinical Sequencing Defines the Genomic Landscape of Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Cell 2018;33(1):125–36 e3 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Su LK, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Preisinger AC, Moser AR, Luongo C, et al. Multiple intestinal neoplasia caused by a mutation in the murine homolog of the APC gene. Science 1992;256(5057):668–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung AF, Carter AM, Kostova KK, Woodruff JF, Crowley D, Bronson RT, et al. Complete deletion of Apc results in severe polyposis in mice. Oncogene 2010;29(12):1857–64 doi 10.1038/onc.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dow LE, O'Rourke KP, Simon J, Tschaharganeh DF, van Es JH, Clevers H, et al. Apc Restoration Promotes Cellular Differentiation and Reestablishes Crypt Homeostasis in Colorectal Cancer. Cell 2015;161(7):1539–52 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nusse R, Clevers H. WNT/beta-Catenin Signaling, Disease, and Emerging Therapeutic Modalities. Cell 2017;169(6):985–99 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2017.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seshagiri S, Stawiski EW, Durinck S, Modrusan Z, Storm EE, Conboy CB, et al. Recurrent R-spondin fusions in colon cancer. Nature 2012;488(7413):660–4 doi 10.1038/nature11282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han T, Schatoff EM, Murphy C, Zafra MP, Wilkinson JE, Elemento O, et al. R-Spondin chromosome rearrangements drive WNT-dependent tumour initiation and maintenance in the intestine. Nature communications 2017;8:15945 doi 10.1038/ncomms15945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hao HX, Xie Y, Zhang Y, Charlat O, Oster E, Avello M, et al. ZNRF3 promotes WNT receptor turnover in an R-spondin-sensitive manner. Nature 2012;485(7397):195–200 doi 10.1038/nature11019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Giannakis M, Hodis E, Jasmine Mu X, Yamauchi M, Rosenbluh J, Cibulskis K, et al. RNF43 is frequently mutated in colorectal and endometrial cancers. Nat Genet 2014;46(12):1264–6 doi 10.1038/ng.3127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Koo BK, Spit M, Jordens I, Low TY, Stange DE, van de Wetering M, et al. Tumour suppressor RNF43 is a stem-cell E3 ligase that induces endocytosis of WNT receptors. Nature 2012;488(7413):665–9 doi 10.1038/nature11308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lau W, Barker N, Low TY, Koo BK, Li VS, Teunissen H, et al. Lgr5 homologues associate with WNT receptors and mediate R-spondin signalling. Nature 2011;476(7360):293–7 doi 10.1038/nature10337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tan D, Ng M, Subbiah V, Messersmith W, Teneggi V, Diermayr V, et al. Phase 1 extension study of ETC-159 an oral PORCN inhibitor administered with bone protective treatment, in patients with advanced solid tumours. Annals of Oncology (ESMO Asia 2018 meeting abstracts) 2018;29 (suppl_9):ix23–ix7 doi 10.1093/annonc/mdy430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zheng HF, Tobias JH, Duncan E, Evans DM, Eriksson J, Paternoster L, et al. WNT16 influences bone mineral density, cortical bone thickness, bone strength, and osteoporotic fracture risk. PLoS Genet 2012;8(7):e1002745 doi 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahiminiya S, Majewski J, Mort J, Moffatt P, Glorieux FH, Rauch F. Mutations in WNT1 are a cause of osteogenesis imperfecta. Journal of medical genetics 2013;50(5):345–8 doi 10.1136/jmedgenet-2013-101567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rizzari C, Conter V, Stary J, Colombini A, Moericke A, Schrappe M. Optimizing asparaginase therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Curr Opin Oncol 2013;25 Suppl 1:S1–9 doi 10.1097/CCO.0b013e32835d7d85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Clarkson B, Krakoff I, Burchenal J, Karnofsky D, Golbey R, Dowling M, et al. Clinical results of treatment with E. coli L-asparaginase in adults with leukemia, lymphoma, and solid tumors. Cancer 1970;25(2):279–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ohnuma T, Holland JF, Freeman A, Sinks LF. Biochemical and pharmacological studies with asparaginase in man. Cancer Res 1970;30(9):2297–305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilson WL, Weiss AJ, Ramirez G. Phase I study of L-asparaginase (NSC 109229). Oncology 1975;32(3-4):109–17 doi 10.1159/000225057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hinze L, Pfirrmann M, Karim S, Degar J, McGuckin C, Vinjamur D, et al. Synthetic Lethality of WNT Pathway Activation and Asparaginase in Drug-Resistant Acute Leukemias. Cancer Cell 2019;35(4):664–76 e7 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Siegfried E, Chou TB, Perrimon N. wingless signaling acts through zeste-white 3, the Drosophila homolog of glycogen synthase kinase-3, to regulate engrailed and establish cell fate. Cell 1992;71(7):1167–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taelman VF, Dobrowolski R, Plouhinec JL, Fuentealba LC, Vorwald PP, Gumper I, et al. WNT signaling requires sequestration of glycogen synthase kinase 3 inside multivesicular endosomes. Cell 2010;143(7):1136–48 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stamos JL, Chu ML, Enos MD, Shah N, Weis WI. Structural basis of GSK-3 inhibition by N-terminal phosphorylation and by the WNT receptor LRP6. Elife 2014;3:e01998 doi 10.7554/eLife.01998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Acebron SP, Karaulanov E, Berger BS, Huang YL, Niehrs C. Mitotic wnt signaling promotes protein stabilization and regulates cell size. Mol Cell 2014;54(4):663–74 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Suraweera A, Munch C, Hanssum A, Bertolotti A. Failure of amino acid homeostasis causes cell death following proteasome inhibition. Mol Cell 2012;48(2):242–53 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vabulas RM, Hartl FU. Protein synthesis upon acute nutrient restriction relies on proteasome function. Science 2005;310(5756):1960–3 doi 10.1126/science.1121925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu Y, Sethi NS, Hinoue T, Schneider BG, Cherniack AD, Sanchez-Vega F, et al. Comparative Molecular Analysis of Gastrointestinal Adenocarcinomas. Cancer Cell 2018;33(4):721–35 e8 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, Venkatesan K, Margolin AA, Kim S, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature 2012;483(7391):603–7 doi 10.1038/nature11003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gayet J, Zhou XP, Duval A, Rolland S, Hoang JM, Cottu P, et al. Extensive characterization of genetic alterations in a series of human colorectal cancer cell lines. Oncogene 2001;20(36):5025–32 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1204611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bennett CN, Ross SE, Longo KA, Bajnok L, Hemati N, Johnson KW, et al. Regulation of WNT signaling during adipogenesis. J Biol Chem 2002;277(34):30998–1004 doi 10.1074/jbc.M204527200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thompson AA, Dilworth S, Hay RJ. Isolation and culture of colonic epithelial cells in serum-free medium. Journal of Tissue Culture Methods 1985;9(2):117–22 doi 10.1007/BF01797782. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Doble BW, Patel S, Wood GA, Kockeritz LK, Woodgett JR. Functional redundancy of GSK-3alpha and GSK-3beta in WNT/beta-catenin signaling shown by using an allelic series of embryonic stem cell lines. Dev Cell 2007;12(6):957–71 doi 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Banerji V, Frumm SM, Ross KN, Li LS, Schinzel AC, Hahn CK, et al. The intersection of genetic and chemical genomic screens identifies GSK-3alpha as a target in human acute myeloid leukemia. J Clin Invest 2012;122(3):935–47 doi 10.1172/JCI46465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wagner FF, Benajiba L, Campbell AJ, Weiwer M, Sacher JR, Gale JP, et al. Exploiting an Asp-Glu "switch" in glycogen synthase kinase 3 to design paralog-selective inhibitors for use in acute myeloid leukemia. Sci Transl Med 2018;10(431) doi 10.1126/scitranslmed.aam8460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schatoff EM, Goswami S, Zafra MP, Foronda M, Shusterman M, Leach BI, et al. Distinct Colorectal Cancer-Associated APC Mutations Dictate Response to Tankyrase Inhibition. Cancer discovery 2019;9(10):1358–71 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Narta UK, Kanwar SS, Azmi W. Pharmacological and clinical evaluation of L-asparaginase in the treatment of leukemia. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2007;61(3):208–21 doi 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2006.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kandasamy P, Gyimesi G, Kanai Y, Hediger MA. Amino acid transporters revisited: New views in health and disease. Trends in biochemical sciences 2018;43(10):752–89 doi 10.1016/j.tibs.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang YL, Anvarian Z, Doderlein G, Acebron SP, Niehrs C. Maternal WNT/STOP signaling promotes cell division during early Xenopus embryogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2015;112(18):5732–7 doi 10.1073/pnas.1423533112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Koepp DM, Schaefer LK, Ye X, Keyomarsi K, Chu C, Harper JW, et al. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin E by the SCFFbw7 ubiquitin ligase. Science 2001;294(5540):173–7 doi 10.1126/science.1065203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi WH, de Poot SA, Lee JH, Kim JH, Han DH, Kim YK, et al. Open-gate mutants of the mammalian proteasome show enhanced ubiquitin-conjugate degradation. Nature communications 2016;7:10963 doi 10.1038/ncomms10963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Crighton D, Wilkinson S, O'Prey J, Syed N, Smith P, Harrison PR, et al. DRAM, a p53-induced modulator of autophagy, is critical for apoptosis. Cell 2006;126(1):121–34 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carugo A, Minelli R, Sapio L, Soeung M, Carbone F, Robinson FS, et al. p53 Is a Master Regulator of Proteostasis in SMARCB1-Deficient Malignant Rhabdoid Tumors. Cancer Cell 2019;35(2):204–20 e9 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bryant KL, Stalnecker CA, Zeitouni D, Klomp JE, Peng S, Tikunov AP, et al. Combination of ERK and autophagy inhibition as a treatment approach for pancreatic cancer. Nat Med 2019;25(4):628–40 doi 10.1038/s41591-019-0368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klionsky DJ, Abdelmohsen K, Abe A, Abedin MJ, Abeliovich H, Acevedo Arozena A, et al. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy (3rd edition). Autophagy 2016;12(1):1–222 doi 10.1080/15548627.2015.1100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palm W, Park Y, Wright K, Pavlova NN, Tuveson DA, Thompson CB. The Utilization of Extracellular Proteins as Nutrients Is Suppressed by mTORC1. Cell 2015;162(2):259–70 doi 10.1016/j.cell.2015.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Commisso C, Davidson SM, Soydaner-Azeloglu RG, Parker SJ, Kamphorst JJ, Hackett S, et al. Macropinocytosis of protein is an amino acid supply route in Ras-transformed cells. Nature 2013;497(7451):633–7 doi 10.1038/nature12138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.West MA, Bretscher MS, Watts C. Distinct endocytotic pathways in epidermal growth factor-stimulated human carcinoma A431 cells. J Cell Biol 1989;109(6 Pt 1):2731–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poppenborg SM, Wittmann J, Walther W, Brandenburg G, Krahmer R, Baumgart J, et al. Impact of anti-PEG IgM antibodies on the pharmacokinetics of pegylated asparaginase preparations in mice. Eur J Pharm Sci 2016;91:122–30 doi 10.1016/j.ejps.2016.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Riihimaki M, Hemminki A, Sundquist J, Hemminki K. Patterns of metastasis in colon and rectal cancer. Sci Rep 2016;6:29765 doi 10.1038/srep29765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.van der Geest LG, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, Verhoef C, Elferink MA, de Wilt JH. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis 2015;32(5):457–65 doi 10.1007/s10585-015-9719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O'Rourke KP, Loizou E, Livshits G, Schatoff EM, Baslan T, Manchado E, et al. Transplantation of engineered organoids enables rapid generation of metastatic mouse models of colorectal cancer. Nat Biotechnol 2017;35(6):577–82 doi 10.1038/nbt.3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lochhead PA, Kinstrie R, Sibbet G, Rawjee T, Morrice N, Cleghon V. A chaperone-dependent GSK3beta transitional intermediate mediates activation-loop autophosphorylation. Mol Cell 2006;24(4):627–33 doi 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chartier C, Raval J, Axelrod F, Bond C, Cain J, Dee-Hoskins C, et al. Therapeutic Targeting of Tumor-Derived R-Spondin Attenuates beta-Catenin Signaling and Tumorigenesis in Multiple Cancer Types. Cancer Res 2016;76(3):713–23 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Storm EE, Durinck S, de Sousa e Melo F, Tremayne J, Kljavin N, Tan C, et al. Targeting PTPRK-RSPO3 colon tumours promotes differentiation and loss of stem-cell function. Nature 2016;529(7584):97–100 doi 10.1038/nature16466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dubey R, van Kerkhof P, Jordens I, Malinauskas T, Pusapati GV, McKenna JK, et al. R-spondins engage heparan sulfate proteoglycans to potentiate WNT signaling. Elife 2020;9 doi 10.7554/eLife.54469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Jiang X, Hao HX, Growney JD, Woolfenden S, Bottiglio C, Ng N, et al. Inactivating mutations of RNF43 confer WNT dependency in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2013;110(31):12649–54 doi 10.1073/pnas.1307218110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu J, Jiao Y, Dal Molin M, Maitra A, de Wilde RF, Wood LD, et al. Whole-exome sequencing of neoplastic cysts of the pancreas reveals recurrent mutations in components of ubiquitin-dependent pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2011;108(52):21188–93 doi 10.1073/pnas.1118046108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kato S, Weng QY, Insco ML, Chen KY, Muralidhar S, Pozniak J, et al. Gain-of-Function Genetic Alterations of G9a Drive Oncogenesis. Cancer discovery 2020;10(7):980–97 doi 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Guezguez B, Almakadi M, Benoit YD, Shapovalova Z, Rahmig S, Fiebig-Comyn A, et al. GSK3 Deficiencies in Hematopoietic Stem Cells Initiate Pre-neoplastic State that Is Predictive of Clinical Outcomes of Human Acute Leukemia. Cancer Cell 2016;29(1):61–74 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]