Abstract

A gap in childlessness rates between women with and without tertiary education in low-fertility settings has been well documented by scholars. However, in the United States, high rates of childlessness are declining for women with tertiary education. Will this current trend lead to a closing of the gap in childlessness across educational subgroups in this country? We answer this question using data from the Current Population Survey from 1976 through 2018. We present population-level trends in permanent childlessness by level of education and estimate the differences in the prevalence of childlessness across educational subgroups. Our findings indicate that the rates of childlessness for women aged 40–44 with tertiary education in the United States are the lowest they have been in over three decades and that rates of childlessness are converging among women with secondary and tertiary education. The declines in childlessness rates and the convergence in childlessness rates between women with secondary and tertiary education are observed for all of the three largest race/ethnicity sub-populations of American women: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women. This report contributes to the emerging literature on the convergence of childlessness rates across sub-populations of women with different levels of educational attainment, which questions the well-established observation that there is a positive relationship between education and childlessness.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10680-019-09550-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Fertility, Childlessness, Education, Current population survey, United States

Introduction

The existing research on the relationship between women’s educational attainment and fertility behaviour leaves no doubt that, at present, childlessness is educationally stratified: the prevalence of childlessness is much higher among women with tertiary education than among women with fewer years of education. A positive relationship between education and childlessness for the cohorts of women born between the 1940s and the 1960s has been well established across North America (Hayford 2013; Ravanera and Beaujot 2014), Europe (Wood et al. 2014; Miettinen et al. 2015; Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2017a), Australia and Japan (Hara 2008; Parr 2010; Wood et al. 2014).

Why is having more education associated with an increased risk of childlessness for women? The most common explanations for this pattern include the higher opportunity costs of childbearing and childrearing for higher educated women (Becker 1991; Cigno 1991) and the emergence of interests and lifestyles that compete with motherhood through exposure to different social schemas and norms in higher education institutions (Kaufman and Feldman 2004). In addition, because prolonged schooling often results in motherhood delay (Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan 2012), it might contribute to an increased risk of sub-fecundity/sterility (Te Velde et al. 2012). Detailed reviews of the mechanisms that link education and childlessness are covered by, e.g. Lappegård and Rønsen (2005) and Kravdal and Rindfuss (2008).

Until recently, the gap in childlessness rates between women with and without tertiary education has changed relatively little across cohorts born in Europe and Australia in the twentieth century (Wood et al. 2014; Beaujouan et al. 2016). However, several studies have reported changes in the educational gradient in childlessness in recent years. Findings from Germany, the Nordic countries, and Spain indicate that the gap in childlessness rates between women with low/medium and high education might be closing (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2017b; Jalovaara et al. 2018; Reher and Requena 2019). Following the recent findings from Europe, in this paper we revisit the association between education and childlessness in the United States.

In the United States., the levels of permanent childlessness oscillated at 20–30% in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Morgan 1991; Rowland 2007). In the 1940s and the 1950s, childlessness rates plummeted to single digit levels and since the 1970s climbed back up until the early 2000s to level off around 14–16% in the twenty-first century (Abma and Martinez 2006; Dye 2010). Studies have indicated a recent convergence in rates of permanent childlessness between white and black women, but have consistently found lower rates of childlessness among Hispanic women (Lunquist et al. 2009; Sweeney and Raley 2014). A positive educational gradient in childlessness has been well documented for the United States. (e.g. Bloom and Trussel 1984; Heaton et al. 1999; Abma and Martinez 2006).

In recent decades, rates of childlessness have steadily declined in the United States. for women with tertiary education (Lamidi and Payne 2013) and Florian and Casper (2014) found that the positive association between tertiary education and childlessness might be weakening, an observation also discussed by Hayford (2013). These findings motivated our research question: Are rates of childlessness converging across educational groups in the United States.? To answer this question, we analyse population-level trends in childlessness across educational subgroups over the past 40 years. We present findings for all women as well as for non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women separately to address historical racial/ethnic differences in childlessness patterns.

The relationship between women’s education and fertility can have profound, long-term effects on a variety of institutions, including the labour market, the family, and the educational institutions themselves (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008). At present, increasingly more women enrol in tertiary education (Esteve et al. 2016) and, as a consequence, the childbearing behaviour of women with high educational attainment will likely be the driving force of future fertility trends. It is thus important to understand under what circumstances rates of childlessness for women with tertiary education increase or decline to better project future fertility change.

Data and Methods

We use the Current Population Survey (CPS) June Fertility Supplements from 1976 to 2018 (Flood et al. 2018). Our sample consists of 117,824 women aged 40–44 and excludes observations with imputed or missing values for all of the variables used (6396 records). Permanent childlessness is defined as not having given birth by ages 40–44. The childlessness rates in our analyses might be therefore slightly overestimated, because some childless women in this age group may go on to become mothers. The analyses are weighted using Fertility Supplement weights.

We designate four main subgroups of educational achievement using years of completed education: less than a high school degree (fewer than 12 years), a high school degree (12 years), some college (13–15 years), and a college degree (16 and more years; equivalent to a Bachelor or higher degrees). This classification is commonly used in studies of the United States context, where educational attainment is frequently measured by years of education, rather than by the completion of specific degrees. Within this classification, individuals with less than a high school degree are assigned to the low education category, while individuals with a high school degree are assigned to the medium education category. Furthermore, a college degree is considered as an equivalent to the high education category (also referred to as tertiary education). This approach also allows us to separate a heterogeneous group of women with 13–15 years of education, which might encompass women who finished post-secondary trainings as well as women who enrolled in but did not complete a college degree.

Additionally, three race/ethnicity sub-populations are identified: non-Hispanic white women, non-Hispanic black women, and Hispanic women. This distinction not only accounts for historical differences in childbearing trends between white and minority women in the United States, it also allows for comparisons between the findings from this study and the research emerging from Europe, where most of the analysed populations are identified as non-Hispanic white (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008; Wood et al. 2014; Beaujouan et al. 2016; Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2017a; Jalovaara et al. 2018). Descriptive statistics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Weighted proportions of women aged 40–44 by childlessness status, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment.

Source: Current Population Survey June Fertility Supplement provided by IPUMS USA (Flood et al. 2018)

| Year | Counts | Childlessness status (%) | Race/ethnicity (%) | Educational attainment (%) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mothers | Childless | Total | Non-Hispanic white | Non-Hispanic black | Non-Hispanic other | Hispanic | Total | Less than a high school degree | High school degree | Some college | College degree | Total | ||

| 1976 | 3296 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 100.0 | 81.4 | 11.9 | 1.6 | 5.2 | 100.0 | 29.5 | 47.2 | 12.6 | 10.7 | 100.0 |

| 1977 | 3918 | 89.0 | 11.0 | 100.0 | 80.8 | 11.9 | 1.8 | 5.5 | 100.0 | 29.2 | 46.8 | 12.8 | 11.3 | 100.0 |

| 1979 | 4008 | 90.1 | 9.9 | 100.0 | 79.8 | 11.7 | 1.9 | 6.6 | 100.0 | 23.3 | 47.2 | 16.1 | 13.4 | 100.0 |

| 1980 | 4598 | 89.9 | 10.1 | 100.0 | 79.1 | 11.5 | 2.5 | 6.8 | 100.0 | 25.3 | 45.1 | 15.5 | 14.1 | 100.0 |

| 1981 | 4239 | 90.4 | 9.6 | 100.0 | 79.0 | 11.5 | 2.8 | 6.6 | 100.0 | 23.1 | 47.2 | 15.6 | 14.1 | 100.0 |

| 1982 | 4297 | 89.2 | 10.8 | 100.0 | 80.2 | 11.3 | 2.6 | 5.9 | 100.0 | 20.9 | 48.1 | 15.4 | 15.7 | 100.0 |

| 1983 | 4442 | 90.0 | 10.0 | 100.0 | 79.4 | 11.1 | 2.9 | 6.6 | 100.0 | 20.2 | 46.3 | 16.3 | 17.2 | 100.0 |

| 1984 | 4528 | 88.9 | 11.1 | 100.0 | 80.3 | 11.1 | 2.8 | 5.8 | 100.0 | 19.5 | 45.4 | 17.5 | 17.6 | 100.0 |

| 1986 | 4541 | 86.7 | 13.3 | 100.0 | 79.3 | 10.9 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 100.0 | 15.8 | 45.2 | 19.8 | 19.2 | 100.0 |

| 1987 | 4838 | 85.6 | 14.4 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 10.5 | 3.5 | 7.4 | 100.0 | 15.8 | 42.6 | 19.2 | 22.3 | 100.0 |

| 1988 | 4704 | 85.3 | 14.7 | 100.0 | 78.6 | 10.7 | 3.5 | 7.2 | 100.0 | 13.5 | 41.5 | 21.0 | 24.1 | 100.0 |

| 1990 | 5295 | 84.0 | 16.0 | 100.0 | 77.1 | 11.7 | 4.0 | 7.2 | 100.0 | 13.4 | 40.2 | 21.8 | 24.7 | 100.0 |

| 1992 | 5317 | 84.3 | 15.7 | 100.0 | 75.7 | 12.3 | 4.2 | 7.7 | 100.0 | 10.5 | 36.5 | 27.1 | 25.9 | 100.0 |

| 1994 | 5395 | 82.6 | 17.4 | 100.0 | 75.6 | 12.6 | 3.9 | 7.9 | 100.0 | 9.0 | 34.5 | 28.7 | 27.8 | 100.0 |

| 1995 | 5634 | 82.5 | 17.5 | 100.0 | 75.8 | 12.7 | 3.4 | 8.2 | 100.0 | 9.6 | 35.9 | 27.7 | 26.8 | 100.0 |

| 1998 | 4905 | 80.9 | 19.1 | 100.0 | 73.6 | 12.7 | 5.4 | 8.3 | 100.0 | 9.6 | 34.2 | 28.5 | 27.8 | 100.0 |

| 2000 | 4791 | 81.1 | 18.9 | 100.0 | 72.2 | 12.7 | 5.9 | 9.2 | 100.0 | 9.4 | 34.9 | 29.4 | 26.3 | 100.0 |

| 2002 | 5614 | 82.0 | 18.0 | 100.0 | 72.1 | 12.7 | 6.0 | 9.2 | 100.0 | 8.4 | 33.8 | 29.9 | 27.9 | 100.0 |

| 2004 | 5167 | 80.6 | 19.4 | 100.0 | 72.3 | 12.7 | 6.2 | 8.9 | 100.0 | 8.1 | 32.7 | 29.3 | 29.9 | 100.0 |

| 2006 | 4792 | 79.1 | 20.9 | 100.0 | 70.7 | 13.4 | 6.9 | 9.0 | 100.0 | 7.1 | 30.8 | 30.4 | 31.7 | 100.0 |

| 2008 | 4455 | 82.1 | 17.9 | 100.0 | 69.4 | 13.6 | 7.5 | 9.4 | 100.0 | 7.8 | 29.9 | 29.6 | 32.7 | 100.0 |

| 2010 | 4235 | 81.3 | 18.7 | 100.0 | 68.7 | 13.4 | 7.8 | 10.2 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 29.6 | 27.9 | 35.2 | 100.0 |

| 2012 | 4108 | 84.2 | 15.8 | 100.0 | 65.1 | 13.5 | 9.0 | 12.4 | 100.0 | 6.8 | 26.3 | 28.6 | 38.3 | 100.0 |

| 2014 | 3868 | 84.0 | 16.0 | 100.0 | 62.4 | 13.3 | 10.0 | 14.4 | 100.0 | 6.9 | 25.0 | 26.6 | 41.5 | 100.0 |

| 2016 | 3525 | 85.3 | 14.7 | 100.0 | 61.3 | 13.3 | 10.5 | 14.9 | 100.0 | 7.3 | 23.8 | 28.0 | 40.9 | 100.0 |

| 2018 | 3314 | 84.4 | 15.6 | 100.0 | 60.7 | 13.3 | 10.9 | 15.1 | 100.0 | 6.2 | 23.0 | 26.2 | 44.5 | 100.0 |

| Total | 117,824 | 84.4 | 15.6 | 100.0 | 73.4 | 12.4 | 5.4 | 8.8 | 100.0 | 12.6 | 36.2 | 24.4 | 26.9 | 100.0 |

The proportion of women who remain childless by age 40–44 increased in the United States from the 1980s through the early 2000s (Table 1) but subsequently declined to reach the level of 15.6% in 2018. The population of women aged 40–44 has also become more diverse, with the proportion of non-Hispanic white women on the decline and the proportions of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic women on the rise. We present trends in childlessness by race/ethnicity in the Online Appendix (Table A1). Over the same time period, the proportion of women with less than high school education or a high school degree declined while the proportion of women with a college degree rose steadily, to reach 44.5% in 2018.

In our analytical approach, we focus on aggregate trends in permanent childlessness across four educational subgroups and the differences between point estimates for these groups. To smooth out annual fluctuations and capture overarching trends, we present the findings in the form of a three-wave moving average. The analyses cover the 1977–2016 period for all women and non-Hispanic white women, the 1986–2016 period for non-Hispanic black women, and the 2000–2016 period for Hispanic women. We use this selection to assure that sample sizes are sufficiently large for minority women, among whom the rates of childlessness and college enrolment have historically been much lower than those among white women.

The descriptive findings presented in this research note were further corroborated using comparisons of confidence intervals around the proportions of childless women by educational subgroups (in the Online Appendix) and predicted probabilities of remaining childless by levels of educational attainment (available from the Author upon request).

Results

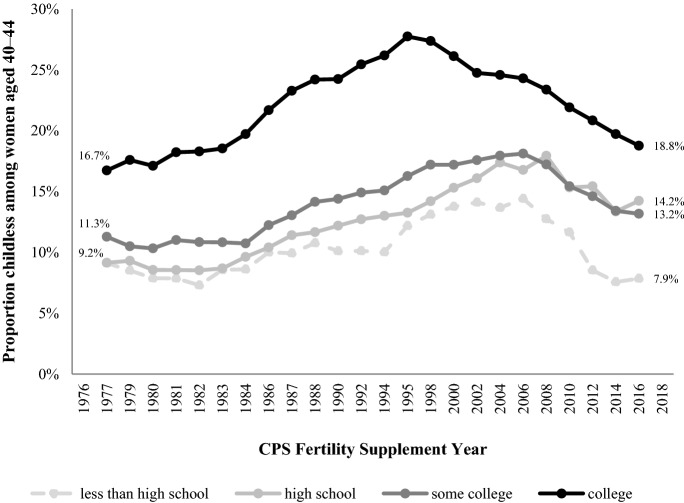

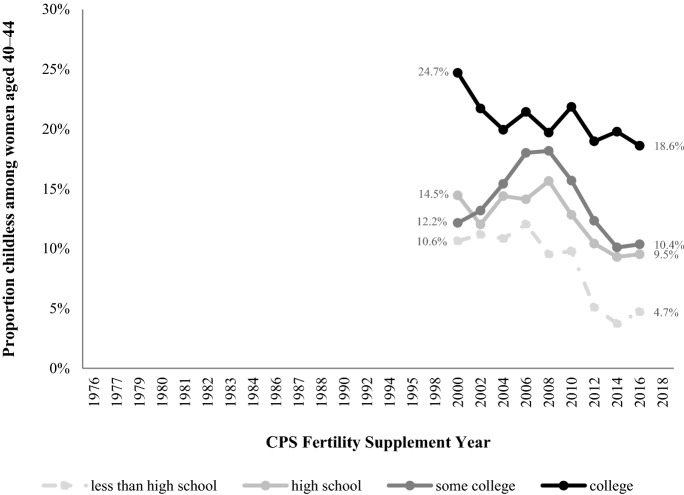

Figure 1 (and Table A2 in the Online Appendix) displays the changes in the proportions of women who were childless in each of the educational groups. Childlessness rates among women aged 40–44 with a college degree increased between the 1970s and the 1990s. This increase resulted in an initial divergence in the proportion of childless women between women with and without college education. Among the latter subgroup, childlessness rates remained relatively low in the 1980s and increased slightly in the 1990s. For instance, in 1995, 27.7% of women aged 40–44 with a college degree remained childless compared to, respectively, 12.2%, 13.3%, and 16.3% for women with less than high school, a high school degree, and some college.

Fig. 1.

Weighted proportions of women aged 40–44 in the United States who remain childless by year and educational category.

Source: Current Population Survey June Fertility Supplement, provided by IPUMS USA (Flood et al. 2018). Findings presented as an average of estimates across three subsequent waves

By the twenty-first century, childlessness rates among women with college education have declined markedly to reach 18.8%, the lowest estimate since 1983. In addition, childlessness increased among women who completed high school or some college at the beginning of this century. These two factors combined resulted in a historical convergence of childlessness rates between women with high (college) and medium (high school and some college) education. In 2016, the difference in childlessness rates between women with college and high school degrees was equal to 4.5% points, the lowest estimate since the 1970s. Noteworthy, a gap in childlessness rates remained between women with college education and women without high school education because the rates of childlessness among women with less than a high school degree increased through the early 2000s but subsequently declined to reach 7.9% in 2016. However, this group of women becomes increasingly selective as women without a high school degree currently make up only 6.2% of all women aged 40–44.

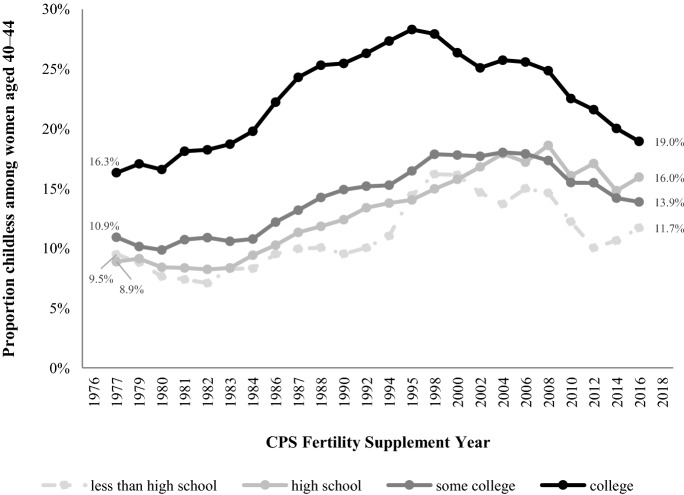

The convergence in childlessness rates across educational groups for women in the United States is visible for all three major race/ethnicity sub-populations, but the timing of the convergence varies across race/ethnicity lines. Among non-Hispanic white women (Fig. 2 below and Table A3 in the Online Appendix), childlessness rates increased in the 1980s and 1990s but then declined to reach 19.0% in 2016. At the same time, childlessness rates among women without college education increased (e.g. 16.0% in 2016 for women high school education). Consequently, the distance between women with college education and all three non-college educational groups diminished to reach remarkably low levels. In 2016, there was only a 3.0% point difference in childlessness rates between women with college and high school education, again the lowest estimate ever recorded in the CPS data.

Fig. 2.

Weighted proportions of non-Hispanic white women aged 40–44 in the United States who remain childless by year and educational category.

Source: Current Population Survey June Fertility Supplement, provided by IPUMS USA (Flood et al. 2018). Findings presented as an average of estimates across three subsequent waves

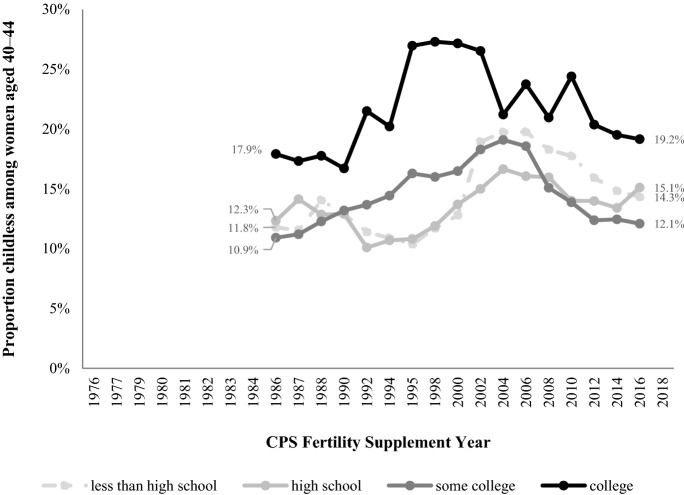

Childlessness rates for women with college education also declined to 19.2% among non-Hispanic Black women and to 18.6% among Hispanic women in 2016 (Figs. 3, 4 below and Tables A4, A5 in the Online Appendix). For the sub-population of non-Hispanic black women, childlessness rates had already converged across educational subgroups by the early 2000s due to an increase in childlessness rates for women without college education at the beginning of the century. By 2016, childlessness rates had diverged but the differences remained small, e.g. at 4.0% points between women with college and high school education. While childlessness rates among women with college education have declined among Hispanic women as well, the differences across educational subgroups have remained due to a decline in childlessness among women without a college degree. Interestingly, among Hispanic women with medium education (high school and some college), the prevalence of childlessness increased at the beginning of the twenty-first century but has declined markedly thereafter.

Fig. 3.

Weighted proportions of non-Hispanic black women aged 40–44 in the United States who remain childless by year and educational category.

Source: Current Population Survey June Fertility Supplement, provided by IPUMS USA (Flood et al. 2018). Findings presented as an average of estimates across three subsequent waves

Fig. 4.

Weighted proportions of Hispanic women aged 40–44 in the United States who remain childless by year and educational category.

Source: Current Population Survey June Fertility Supplement, provided by IPUMS USA (Flood et al. 2018). Findings presented as an average of estimates across three subsequent waves

Conclusions

In contrast to historical trends of diverging rates of permanent childlessness among women with high and low/medium education in the United States, in this research note we document a new emerging phenomenon—a convergence of childlessness rates between women with medium and high education in the twenty-first century. The gap between these two groups of women has largely disappeared: in 2016, the difference in childlessness rates between women with medium and high education was the smallest since the 1970s (at only 4.5% points).

This convergence in childlessness rates across educational subgroups is driven by marked declines in childlessness among women with high education, for whom the rates of childlessness in 2016 were the lowest in over three decades, at 18.8%. Declines in childlessness among higher educated women are observed across the three major race/ethnicity groups in the United States: non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and Hispanic women.

These findings are unusual given the well-established divergence in childlessness trends between women with low/medium educational attainment and women with high educational attainment (Wood et al. 2014; Beaujouan et al. 2016). However, our results follow several recent studies in reporting changes in the educational gradient in childlessness (Kravdal and Rindfuss 2008; Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2017b; Jalovaara et al. 2018; Reher and Requena 2019). We encourage family scholars to investigate other settings in order to collect more evidence about these potential shifts in the relationship between educational attainment and childlessness among women.

Several potential factors could explain the declines in childlessness among women with high education. First, as more women enter higher education, the selectivity of this life path could have weakened. Women with tertiary education now from a heterogeneous group of women, from different social, racial/ethnic, and cultural backgrounds. This increased diversity might contribute to the attenuation of the difference in childlessness rates between women with medium and high education. The heterogeneity of the effects of education on fertility has been reported, e.g. by Hoem et al. (2006) and Brand and Davis (2011).

Additionally, due to a spread of the dual-earner couple model and rising costs of life and parenthood, men might now prefer partners with a high wage potential (Oppenheimer 1994). This shift might lead to better-educated women being viewed as more desirable partners than they were in the past. Higher rates of partnering among women with tertiary education could have resulted in lower childlessness rates for this group. Alternatively, changes in work schedules (i.e. increased availability of remote or flex work) and improved access to child care might have eased the tensions between childbearing and career pursuits and decreased the opportunity costs of motherhood for women with high educational attainment.

It is also possible that women who in the past would have been forced by age-related infecundity/sterility to abandon their plans to have children can now become mothers with medical assistance. Access to assisted reproduction in the United States is expanding (Sunderam et al. 2018), and rates of first births for women aged 34–39 and 40–44 have been rising in the United States (Billari et al. 2007; Martin et al. 2017). We encourage family scholars to pursue future analyses that can uncover the causes of this convergence in women’s childlessness across educational subgroups as new data for the United States become available.

Finally, we outline two additional research questions this note has generated. Childlessness rates among women with the lowest educational attainment are on the decline in the United States, a trend also observed in Nordic countries (Jalovaara et al. 2018). However, recent studies from Germany and Spain have reported increases in childlessness rates among women with low education (Kreyenfeld and Konietzka 2017b; Reher and Requena 2019). These cross-country differences in childlessness rates among women with low education raise questions about the circumstances under which low educated—and potentially low income—women pursue motherhood, and what role childbearing intentions and access to effective contraception play in their transition to parenthood.

In addition, a gap in childlessness persists among Hispanic women with low/medium and high education due to marked declines in childlessness among Hispanic women with medium and low educational attainment. This is an important finding because the share of Hispanic women in the total population of American women is rising (Flores 2017). Given the heterogeneity of the Hispanic population in America with respect to their country of citizenship and the length of residence in the United States (Parrado and Morgan 2008; Parrado 2011), further analyses are needed to understand the factors that underline these large declines.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The author is grateful for comments on this paper to Yong Cai, S. Philip Morgan, Monika Mynarska, and Katherine I. Tierney. This research was partially supported by Carolina Population Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, which receives funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P2C HD050924).

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors confirm that there are no known conflicts of interest associated with this publication, and there has been no significant financial support for this work that could have influenced its outcome. We further confirm that no aspect of the work covered in this manuscript has involved either animals or human patients. The research covered in this manuscript was conducted solely using secondary data from publicly available sources.

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: Figure 2 has been replaced with its correct original version.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

2/11/2020

Correction to

References

- Abma JC, Martinez GM. Childlessness among older women in the United States: Trends and profiles. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2006;68(4):1045–1056. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00312.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beaujouan E, Brzozowska Z, Zeman K. The limited effect of increasing educational attainment on childlessness trends in twentieth-century Europe, women born 1916–65. Population Studies. 2016;70(3):275–291. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2016.1206210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. Treatise on the family. Enlarged. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Billari FC, Kohler HP, Andersson G, Lundström H. Approaching the limit: Long-term trends in late and very late fertility. Population and Development Review. 2007;33:149–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2007.00162.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom DE, Trussell J. What are the determinants of delayed childbearing and permanent childlessness in the United States? Demography. 1984;21(4):591–611. doi: 10.2307/2060917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld HP, Huinink J. Human capital investments or norms of role transition? How women's schooling and career affect the process of family formation. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(1):143–168. doi: 10.1086/229743. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brand JE, Davis D. The impact of college education on fertility: Evidence for heterogeneous effects. Demography. 2011;48(3):863–887. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cigno A. Economics of the family. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, J. L. (2010). Fertility of American women: June 2008. Current Population Reports P20-563. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau.

- Esteve A, Schwartz CR, Van Bavel J, Permanyer I, Klesment M, García-Román J. The end of hypergamy: Global trends and implications. Population and Development Review. 2016;42(4):615–625. doi: 10.1111/padr.12012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flood, S., King, M., Rodgers, R., Ruggles, S., & Warren, J. R. (2018). Integrated public use microdata series, current population survey: Version 6.0. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS. 10.18128/D030.V6.0. [DOI]

- Flores, A. (2017, September 18). How the US Hispanic population is changing. Pew Research Center Reports: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/18/how-the-u-s-hispanic-population-is-changing/.

- Florian, S. M., & Casper, L. M. (April 2014). Differentials in fertility patterns: The divergence of childbearing and the convergence of childlessness in the United States, 1980s–2000s. Paper presented at population association of America annual meeting. Boston, MA.

- Hara T. Increasing childlessness in Germany and Japan: Toward a childless society? International Journal of Japanese Sociology. 2008;17(1):42–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6781.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayford SR. Marriage (still) matters: The contribution of demographic change to trends in childlessness in the United States. Demography. 2013;50(5):1641–1661. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB, Jacobson CK, Holland K. Persistence and change in decisions to remain childless. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(2):531–539. doi: 10.2307/353767. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM, Neyer G, Andersson G. Education and childlessness: The relationship between educational field, educational level, and childlessness among Swedish women born in 1955–59. Demographic Research. 2006;14(15):331–380. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2006.14.15. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jalovaara M, Neyer G, Andersson G, Dahlberg J, Dommermuth L, Lappegård T. Education, gender, and cohort fertility in the Nordic countries. European Journal of Population. 2018 doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9492-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman P, Feldman KA. Forming identities in college: A sociological approach. Research in Higher Education. 2004;45(5):463–496. doi: 10.1023/B:RIHE.0000032325.56126.29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø, Rindfuss RR. Changing relationships between education and fertility: A study of women and men born 1940 to 1964. American Sociological Review. 2008;73(5):854–873. doi: 10.1177/000312240807300508. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M, Konietzka D. Childlessness in Europe. Contexts, causes, and consequences. Dordrecht: Springer; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kreyenfeld M, Konietzka D. Childlessness in east and west Germany: Long-term trends and social disparities. In: Kreyenfeld M, Konietzka D, editors. Childlessness in Europe. Contexts, causes, and consequences. Dordrecht: Springer; 2017. pp. 97–114. [Google Scholar]

- Lamidi, E., & Payne, K. K. (2013). Change in proportion of childless women, 1995–2010 (FP-13-20). National Center for Family & Marriage Research. Retrieved from https://ncfmr.bgsu.edu/pdf/family_profiles/file140559.pdf.

- Lappegård T, Rønsen M. The multifaceted impact of education on entry into motherhood. European Journal of Population/Revue européenne de Démographie. 2005;21(1):31–49. doi: 10.1007/s10680-004-6756-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lundquist JH, Budig MJ, Curtis A. Race and childlessness in America, 1988–2002. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2009;71(3):741–755. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2009.00630.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJ, Driscoll AK, Mathews TJ. Births: Final Data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Reports: From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2017;66(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miettinen, A., Rotkirch, A., Szalma, I., Donno, A., & Tanturri, M. L. (2015). Increasing childlessness in Europe: Time trends and country differences. FamiliesAndSocieties working paper 33. Stockholm: Stockholm University.

- Morgan S. Late nineteenth-and early twentieth-century childlessness. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):779–807. doi: 10.1086/229820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ní Bhrolcháin M, Beaujouan É. Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment. Population Studies. 2012;66(3):311–327. doi: 10.1080/00324728.2012.697569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oppenheimer VK. Women's rising employment and the future of the family in industrial societies. Population and Development Review. 1994;20:293–342. doi: 10.2307/2137521. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parr N. Childlessness among men in Australia. Population Research and Policy Review. 2010;29(3):319–338. doi: 10.1007/s11113-009-9142-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA. How high is Hispanic/Mexican fertility in the United States? Immigration and tempo considerations. Demography. 2011;48(3):1059–1080. doi: 10.1007/s13524-011-0045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrado EA, Morgan SP. Intergenerational fertility among Hispanic women: New evidence of immigrant assimilation. Demography. 2008;45(3):651–671. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravanera ZR, Beaujot R. Childlessness of men in Canada: Result of a waiting game in a changing family context. Canadian Studies in Population. 2014;41(1–2):38–60. doi: 10.25336/P6J02Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reher D, Requena M. Childlessness in twentieth-century Spain: A cohort analysis for women born 1920–1969. European Journal of Population. 2019;35:133–160. doi: 10.1007/s10680-018-9471-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland DT. Historical trends in childlessness. Journal of Family Issues. 2007;28(10):1311–1337. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07303823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sunderam S, Kissin DM, Crawford SB, Folger SG, Boulet SL, Warner L, Barfield WD. Assisted reproductive technology surveillance—United States, 2015. MMWR Surveillance Summaries. 2018;67(3):1–28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6703a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney MM, Raley RK. Race, ethnicity, and the changing context of childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014;40:539–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Te Velde E, Habbema D, Leridon H, Eijkemans M. The effect of postponement of first motherhood on permanent involuntary childlessness and total fertility rate in six European countries since the 1970s. Human Reproduction. 2012;27(4):1179–1183. doi: 10.1093/humrep/der455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood J, Neels K, Kil T. The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries. Demographic Research. 2014;31:1365–1416. doi: 10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.