Nitrification is a key process in the biogeochemical and global nitrogen cycle. Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) perform the second step of aerobic nitrification (converting nitrite to nitrate), which is critical for transferring nitrogen to other organisms for assimilation or energy. Despite their ecological importance, there are few cultured or genomic representatives from marine systems. Here, we obtained two NOB (designated MSP and DJ) enriched from marine sediments and estimated the physiological and genomic traits of these marine microbes. Both NOB enrichment cultures exhibit distinct responses to various nitrite and salt concentrations. Genomic analyses suggest that these NOB are metabolically flexible (similar to other previously described NOB) yet also have individual genomic differences that likely support distinct niche distribution. In conclusion, this study provides more insights into the ecological roles of NOB in marine environments.

KEYWORDS: Nitrospina, Nitrospira, cultivation, marine sediment, metagenomics, nitrite oxidation

ABSTRACT

Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) are ubiquitous and abundant microorganisms that play key roles in global nitrogen and carbon biogeochemical cycling. Despite recent advances in understanding NOB physiology and taxonomy, currently very few cultured NOB or representative NOB genome sequences from marine environments exist. In this study, we employed enrichment culturing and genomic approaches to shed light on the phylogeny and metabolic capacity of marine NOB. We successfully enriched two marine NOB (designated MSP and DJ) and obtained a high-quality metagenome-assembled genome (MAG) from each organism. The maximum nitrite oxidation rates of the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures were 13.8 and 30.0 μM nitrite per day, respectively, with these optimum rates occurring at 0.1 mM and 0.3 mM nitrite, respectively. Each enrichment culture exhibited a different tolerance to various nitrite and salt concentrations. Based on phylogenomic position and overall genome relatedness indices, both NOB MAGs were proposed as novel taxa within the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla. Functional predictions indicated that both NOB MAGs shared many highly conserved metabolic features with other NOB. Both NOB MAGs encoded proteins for hydrogen and organic compound metabolism and defense mechanisms for oxidative stress. Additionally, these organisms may have the genetic potential to produce cobalamin (an essential enzyme cofactor that is limiting in many environments) and, thus, may play an important role in recycling cobalamin in marine sediment. Overall, this study appreciably expands our understanding of the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla and suggests that these NOB play important biogeochemical roles in marine habitats.

IMPORTANCE Nitrification is a key process in the biogeochemical and global nitrogen cycle. Nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB) perform the second step of aerobic nitrification (converting nitrite to nitrate), which is critical for transferring nitrogen to other organisms for assimilation or energy. Despite their ecological importance, there are few cultured or genomic representatives from marine systems. Here, we obtained two NOB (designated MSP and DJ) enriched from marine sediments and estimated the physiological and genomic traits of these marine microbes. Both NOB enrichment cultures exhibit distinct responses to various nitrite and salt concentrations. Genomic analyses suggest that these NOB are metabolically flexible (similar to other previously described NOB) yet also have individual genomic differences that likely support distinct niche distribution. In conclusion, this study provides more insights into the ecological roles of NOB in marine environments.

INTRODUCTION

The ocean comprises about 70% of the Earth’s surface and is the largest reservoir of organisms. Marine sediments, especially nitrogen, substantially contribute to the global elemental cycles (1). Bioavailable nitrogen produced by nitrogen-fixing bacteria is transformed through the process of remineralization, which consists of ammonification and nitrification (1). Aerobic nitrification acts as a key process within the marine biogeochemical nitrogen cycle, biologically catalyzing ammonia to nitrate via nitrite by two distinct groups of chemolithoautotrophic microorganisms. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria oxidize ammonia to nitrite with hydroxylamine as an intermediate substrate. Nitrite is subsequently oxidized to nitrate by nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB). Members of a third newly described group of organisms oxidize ammonia to nitrate (comammox) (2–4). Nitrate produced by nitrite oxidation by NOB constitutes about 90% of the fixed nitrogen in the ocean (5). Nitrate is an important nitrogen source for many plants and microorganisms and is used as an electron acceptor for microbial anaerobic respiration. Thus, NOB are important contributors to the global nitrogen cycle and the main biological source of nitrate in marine environments. NOB also play a critical role in global carbon cycling via carbon fixation (6). Nevertheless, there are few studies describing the distribution and abundance of NOB in marine sediments and water columns (7–9).

The genus Nitrobacter was first isolated and recognized by Winogradsky (10) as a key player in the second step of nitrification. Since then, the number of newly isolated NOB has been very limited owing to difficulty in their cultivation under laboratory conditions. NOB have been known to be restricted to a few phylogenetic groups, including Nitrobacter (mainly found in terrestrial habitats), Nitrococcus (marine), Nitrospina (marine), and Nitrospira (terrestrial) (11). However, due to recent improvements in cultivation and cultivation-free approaches, the phylogenetic diversity of NOB has been expanded with several new lineages, including “Candidatus Nitrotoga” (12–14), Nitrolancea (15, 16), and “Candidatus Nitromaritima” (17).

Despite the fact that our understanding of NOB ecology comes from only a few cultured representatives and genomic data, recent studies including metagenomics showed that NOB are ecophysiologically and metabolically versatile, particularly within the genus Nitrospira. For instance, cultivation and genomic studies suggested that Nitrospira spp. can use hydrogen and formate as alternative energy sources (18, 19). However, these studies focused on the specific members of Nitrospira phylogenetic groups from terrestrial (nonmarine) environments, such as municipal wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) (see references in reference 20).

Only a few NOB have been isolated from marine environments, and their metabolism, geographical distribution, and diversity still remain largely unknown, mostly due to the lack of cultivated representatives. There are currently very few reported marine NOB cultured representatives: Nitrococcus mobilis, Nitrospina gracilis, and Nitrospina watsonii (21, 22), Nitrospira marina (23), Nitrospira ecomares (24), and NOB enrichments from Dutch coastal North Sea waters (25) and marine sponges (26).

In this study, we used cultivation and genome sequencing to characterize two distinct NOB from marine sediments affiliated with the phyla Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota. We describe physiological characteristics of the enriched NOB and their predicted genomic traits (based on metagenome-assembled genomes, MAGs, from the enrichments). The present findings expand our understanding of the metabolic versatility for marine NOB and provide deeper insights for further experimental studies aimed at investigating genomics-predicted traits in nature.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Nitrite-oxidizing enrichment cultures from marine sediments.

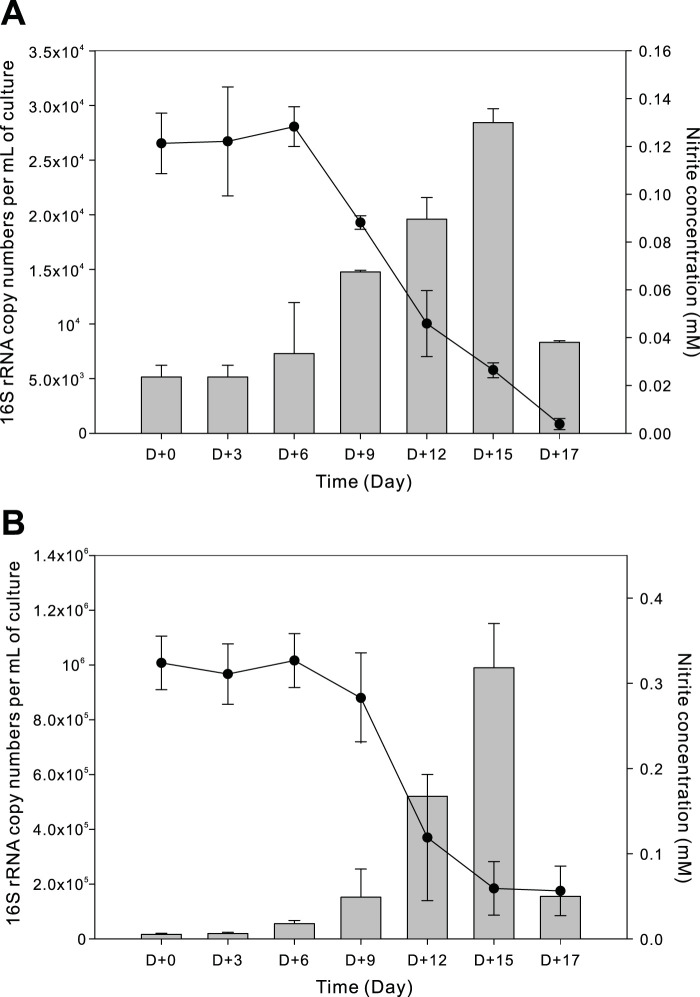

Two enrichment cultures with nitrite oxidation activity were independently obtained from marine sediments from two different sampling sites on Jeju Island, Republic of Korea (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). To stimulate chemolithoautotrophic nitrite oxidation, nitrite (0.1 mM) was used as the sole energy source and bicarbonate as the sole carbon source. Once enrichment cultures showed nitrite consumption (after 1 month), an inoculum of 5% (vol/vol) of total culture volume was serially transferred to fresh medium. The two enriched cultures were designated MSP and DJ, based on the sampling sites. Bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone library and amplicon sequence analyses confirmed that there was only one unique NOB 16S rRNA gene sequence in each culture. 16S rRNA gene sequences for MSP and DJ were closely related to Nitrospina watsonii (92.9% similarity estimated by BLASTN) and Nitrospira marina (99.4% similarity), respectively (Fig. S1). Nitrite consumption was coupled with increases in NOB 16S rRNA gene copies (Fig. 1). Nitrite was nearly stoichiometrically converted to nitrate over a period of about 2 weeks. Without nitrite supplement as the sole energy source, no growth (indicated by no change in 16S rRNA gene copy numbers measured using quantitative real-time PCR [qPCR]) was observed for either culture.

FIG 1.

Relationship between nitrite oxidation and copy number of the 16S rRNA genes per milliliter of culture for two enriched NOB cultures, designated MSP (A) and DJ (B), from marine sediment. MSP and DJ cultures were enriched in artificial seawater medium with 0.1 and 0.3 mM nitrite, respectively, as the sole energy source. The NOB 16S rRNA gene copy numbers (presented by gray bars) increase with nitrite consumption (nitrite concentrations presented by closed circles). Data are means ± standard deviations from triplicate samples.

Nitrite oxidation rates were evaluated at various nitrite concentrations (0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.5 mM) (Fig. S2A). For the MSP enrichment culture, nitrite oxidation occurred at 0.1 to 0.5 mM nitrite concentrations; however, there was a long lag phase at 0.3 mM (9 to 13 days) and very minimal nitrite oxidation at 0.5 mM (6.76 μM per day). This suggests that MSP experiences inhibition, stress, or toxicity above 0.3 mM nitrite despite the high nitrite tolerance (up to 20 mM nitrite) of two isolated Nitrospina strains (N. watsonii [21] and N. gracilis [22]). Maximum nitrite oxidation rates occurred at 0.1 mM nitrite with a 6-day lag and 13.8 μM nitrite oxidized per day (Fig. S2A).

For the DJ enrichment culture, nitrite oxidation occurred at 0.1 to 0.5 mM nitrite concentrations. DJ was able to oxidize nitrite up to concentrations of 1 mM (data not shown); however, growth inhibition (estimated by qPCR) was observed above 0.5 mM nitrite. Maximum nitrite oxidation rates occurred at 0.3 mM nitrite with a 3-day lag and 30.0 μM nitrite oxidized per day (Fig. S2A). These rates are comparable to the NOB culture Aa01 from a marine sponge (up to 110 μM nitrite per day) (26), culture S11 from marine sediment of the Laptev Sea (34 to 36 μM nitrite per day) (27), “Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii” (117 μM nitrite per day) (28), and “Candidatus Nitrospira bockiana” (nearly 750 μM nitrite per day) (29). However, these values were much lower than that of North Sea mixed NOB cultures (up to 3 mM nitrite per day) with Nitrospira as the dominant NOB (25).

To determine salt tolerance, the two enrichment cultures were grown with modified low-salt medium (0.2 mM nitrite) (see Materials and Methods) adjusted to various NaCl concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 3, and 5%, wt/vol, NaCl). For the MSP enrichment culture, nitrite oxidation was observed only at 3%, wt/vol, NaCl (data not shown), which is similar to the amount of NaCl supplied in the artificial seawater (ASW) medium used for cultivation (∼2.46%, wt/vol). This suggests that this organism has a narrow niche requiring a specific range of salt concentrations, like other isolated strains of Nitrospina (N. gracilis and N. watsonii [21, 22]) with a salt tolerance of 70 to 100% seawater (roughly equivalent to ∼2 to 3%, wt/vol, NaCl based on typical salt concentrations in seawater). On the other hand, the DJ enrichment culture had a broader tolerance for salt concentrations, showing nitrite oxidation from 0 to 5% (wt/vol) NaCl. The optimum NaCl concentration was 1% (46.8 μM nitrite oxidized per day), and activity decreased at conditions above 2% (Fig. S2B). These results suggest a broader habitat range with regard to salt for DJ than MSP. Very little is known about the salt tolerance of other marine Nitrospira NOB (most cultivated strains were enriched from nonmarine environments, including WWTP), although the only described marine Nitrospira species (N. marina) is an obligate halophile (growing with 70 to 100% seawater mineral medium) (23). It is important to note that these results show nitrite oxidation during salt exposure, but the enriched MSP and DJ NOB (as well as other NOB) may survive/grow under various salt concentrations using alternative metabolisms (see below). Overall, it can be inferred that NOB exhibit different tolerance levels to salinity stress, which has implications for population ecology, including habitat range and dispersal.

Genomic sequencing and assembly of NOB from the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures.

Metagenomic sequencing and assembly of the enrichment cultures showed that each culture contained one NOB bin (comprised of 56 contigs for MSP and a single contig for DJ; Table S1), corresponding to one predicted NOB genome within each culture designated MSP or DJ. CheckM (30) completeness estimates were 96.6% for MSP and 87.7% for DJ, with low contamination (5.1% for MSP and 1.8% for DJ). The estimated genome size for MSP and DJ was 4.13 and 4.15 Mbp with 45.7 and 50.3% GC content, respectively (see also Table S2).

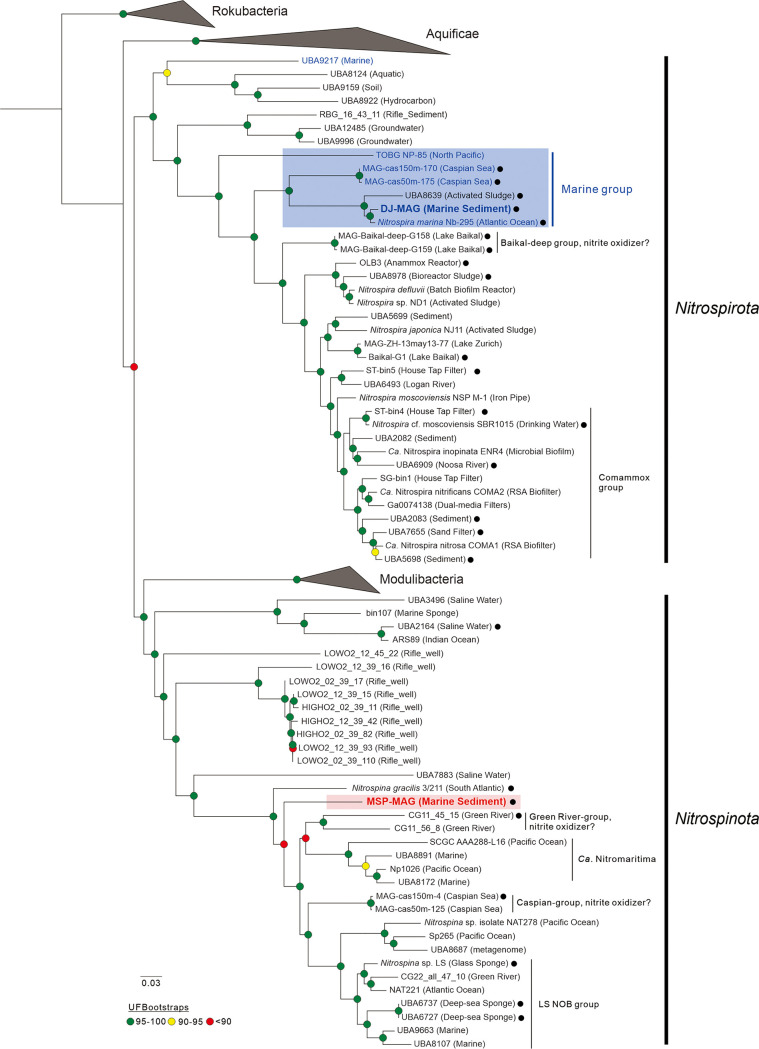

A maximum likelihood phylogenomic tree revealed that the MSP and DJ NOB genome sequences fell within the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla, respectively (Fig. 2). MSP branched distantly from other Nitrospina species genomic representatives, including the cultivated N. gracilis. DJ clustered very closely with N. marina Nb-295 from the Atlantic Ocean (31). Genome-wide average nucleotide identity (ANI) and average amino acid identity (AAI) comparisons further delineated MSP and DJ into the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla, respectively (Fig. S3). ANI values between MSP and the closest described species, N. gracilis, were 65.2%, and AAI values were 57.9%. DJ had a high value for ANI (91.8%) and AAI (91.6%) to N. marina. Based on phylogenetic position and overall genome relatedness indices (ANI and AAI), and in accordance with the guidelines of Konstantinidis et al. (32), we designate these taxa “Candidatus Nitrospina” sp. strain MSP and “Candidatus Nitrospira” sp. strain DJ, representing novel marine NOB.

FIG 2.

Phylogenomic tree of Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla. Whole-genome phylogenies based on a maximum likelihood (phylogenomic) tree inferred from 138 genomes. The MSP and DJ NOB genomes are highlighted in red and blue boldface, respectively. Putative NxrA sequences harboring MAGs (including MSP and DJ) are indicated by black closed circles. The strength of support for internal nodes was assessed by performing bootstrap replicates, with the obtained values shown as colored circles (see the legend). A midpoint root was used when selecting outgroup sequences.

Genomic repertoire of the NOB from the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures.

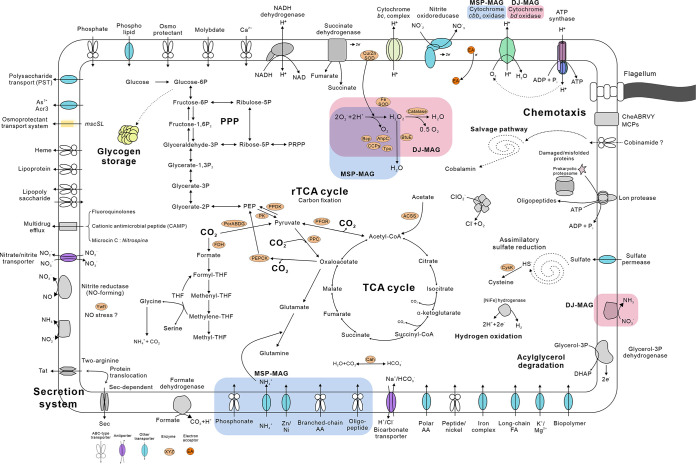

The potential metabolic capabilities of the cultivated MSP and DJ NOB were evaluated based on genome annotations referencing various functional gene databases (Fig. 3).

FIG 3.

Metabolic reconstruction of the MSP and DJ NOB genomes. Unique features for MSP and DJ are indicated by rounded rectangles marked by blue and red, respectively (all other features were shared between both genomes). The text in boldface depicts names of pathways and metabolic processes. ACSS, acetyl-CoA synthetase and carbonic anhydrase; PorABCD, pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase; FDH, formate dehydrogenase; PPC, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase; PEPCK, phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase; PFOR, pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase; PK, pyruvate kinase; PPDK, pyruvate, phosphate dikinase; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; CysK, cysteine synthase A; Cah, carbonic anhydrolase; Ywfl, putative heme peroxidase; SOD, superoxide dismutase; BtuE, glutathione peroxidase; peroxiredoxin, Bcp, CCPs, AhpC, and Tpx; AA, amino acid; FA, fatty acid; THF, tetrahydrofolate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate.

Nitrite oxidation.

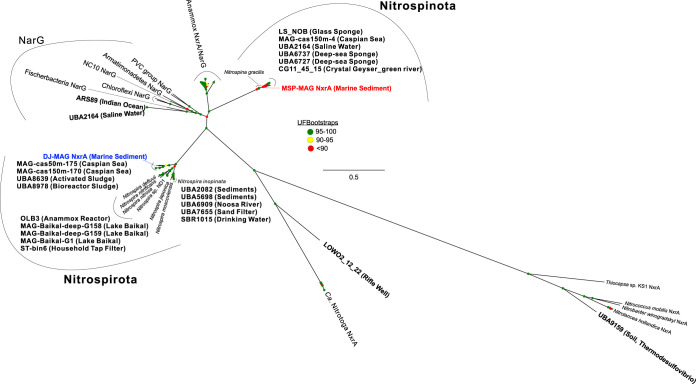

The enriched NOB grew in culture in mineral medium using nitrite as the sole energy source. Nitrite can be converted to nitrate by nitrite oxidoreductase (NXR), which is known as a member of the type II dimethyl sulfoxide reductase family of molybdoenzymes. The capacity for nitrite oxidation was confirmed within the MSP and DJ NOB genomes via the presence of nitrite oxidoreductase alpha subunit (NxrA). An unrooted phylogenetic tree of NxrA protein sequences showed that Nitrospirota NxrA sequences were more diverse than those of Nitrospinota (Fig. 4). The MSP NOB genome contained one gene coding for NxrA. The predicted protein sequence was missing approximately 550 amino acids (likely the result of incomplete sequencing, since the gene was located at the end of a contig), including the conserved amino acids found in all NOB and the signal peptide coding region typically found in Nitrospira and Nitrospina NOB. The short MSP NxrA protein sequence grouped closely with Nitrospina sequences in the phylogenetic tree (with 93.6% AAI to Nitrospina gracilis over 628 amino acids). The DJ NOB genome contained three complete gene copies coding for NxrA (1,145 amino acids), with an average AAI of 87.9%. All three copies grouped phylogenetically with NxrA proteins from Nitrospira sequences. The DJ NxrA protein sequence had an AAI of 90.2% to Nitrospira marina NxrA (three copies; LX98DRAFT_0396, _0404, and _4275, identified by BLASTP). The DJ NxrA protein sequences contained residues conserved among all NOB and previously predicted to play a role in binding a molybdopterin cofactor, a [4Fe–4S] cluster, and the nitrite/nitrate substrate (33, 34). However, one DJ NxrA copy had a leucine in alignment position 290 instead of a tyrosine. Each NxrA copy from the DJ genome had a predicted twin-arginine translocation (Tat) or lysine-arginine signal peptide on the N terminus (35, 36), which supports the translocation of this enzyme into the periplasm, similar to other Nitrospira organisms (34, 37). A periplasm-facing NXR in these organisms would likely yield an energetic benefit compared to other NOB with cytoplasm-facing NXR (e.g., Nitrobacter and Nitrococcus) due to the additional proton release for the proton motive force.

FIG 4.

Phylogenetic analysis of nitrite oxidoreductase subunit alpha (NxrA) protein sequences. An unrooted maximum-likelihood tree of NxrA sequences from MSP (red), DJ (blue), and other representative NOB, along with nitrate reductase subunit alpha (NarG) sequences. Boldface denotes NxrA or NarG sequence-identified reference MAGs selected in this study. Bootstrap values on nodes are indicated by colored circles (see the legend). All related sequence data are provided as an additional supplemental file.

Other forms of nitrogen metabolism.

Both MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded dissimilatory nitrite reductase proteins (NO-forming, NirK) for the reduction of nitrite to nitric oxide, like most NOB. Generally, NirK proteins play an important role in denitrification by denitrifying bacteria. Additionally, many genomes from ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms harbor nirK genes, and NirK proteins likely play an important role in the archaeal ammonia oxidation pathway (38, 39). The exact function of NirK has not been determined in NOB but has been suggested to play a role in managing the redox state in Nitrobacter (40) or contributing to denitrification in Nitrospira (19, 34, 41).

The MSP and DJ NOB genomes both contained genes encoding nitrite/nitrate transporter (NarK) and cytochrome c nitrite reductase small subunit (NrfH) proteins. The MSP NOB genome also encoded transporters for nitrite (NirC) and ammonium (Amt), assimilatory ferredoxin-nitrite reductase (NirA), formate-dependent nitrite reductase (cytochrome c552 subunit, NrfA), and formate-dependent nitrite reductase (penta-heme cytochrome c, NrfB). Many other NOB genomes have been shown to also encode each of these proteins (2, 34, 42, 43).

Recent studies showed that Nitrospira spp. can perform not only nitrite oxidation but also urea and cyanate degradation, allowing for reciprocal feeding with ammonia oxidizers by providing a source of ammonium (2, 3, 19, 44). Here, neither of the MSP nor DJ NOB genomes contained predicted urease or cyanase genes, suggesting that they are not involved in reciprocal feeding. Neither genome contained ammonia monooxygenase genes (for ammonia oxidation), and no growth was observed when the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures were provided ammonium as the sole energy source, confirming that the DJ and MSP NOB are not capable of complete ammonia oxidation, as seen in some Nitrospira spp. (2, 3).

Energetics and reverse electron flow.

The MSP and DJ genomes both encoded proteins for a complete electron transport chain (Fig. 3). Electrons from NXR are passed to cytochrome c and then transferred to oxygen via a terminal oxidase (complex IV). The MSP genome encoded a cbb3-type cytochrome c complex as its terminal oxidase, which has a high affinity for oxygen (45) and suggests that MSP NOB cells can grow in microoxic environments. Many other NOB genomes also contain genes encoding cbb3-type cytochromes, including Nitrococcus, Nitrospina, “Ca. Nitrotoga,” and Thiocapsa (14, 33, 41, 46, 47), but none of the described Nitrospira genomes (19, 34, 42, 43). The DJ NOB genome encoded a bd-like cytochrome (34) as the terminal oxidase. Cytochrome bd oxidases (found in many bacteria, including pathogens) also have a high affinity for oxygen (48); however, oxygen affinity is related to oxidative and nitrosative stress conditions (49) rather than energetics. Overall, this suggests that NOB in the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla exhibit habitat partitioning depending upon the oxygen concentrations within marine environments.

The MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded proteins predicted to produce ATP (derived via the proton motive force using an F-type ATPase) and NADH (derived via reverse electron flow through cytochrome bc1 and NADH dehydrogenase, complexes III and I of the respiratory chain). Both NXR and NADH dehydrogenase proteins are predicted to be bidirectional (14; see also references 41–43 and references cited therein), which suggests that MSP and DJ NOB cells can transfer electrons from NADH (produced during organic carbon metabolism; see below) to a terminal oxidase or to NXR for the reduction of nitrate to nitrite in the absence of oxygen.

Hydrogen metabolism.

The MSP genome contained genes encoding a group 3b NiFe-hydrogenase (see reference 50 and references therein), which likely couples oxidation of NADPH to fermentative evolution of H2 or the reverse reaction in the cytosol (51). The MSP hydrogenase grouped closely with other group 3b NiFe-hydrogenases (Fig. S4) found in N. gracilis (41) and N. mobilis (46). The DJ genome contained the complete gene repertoire (hybABCDEF) to encode a group 2a NiFe-hydrogenase (likely membrane associated) involved in hydrogenotrophic respiration using oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor (see reference 50 and references therein). The DJ hydrogenase was closely related to a group 2a NiFe-hydrogenase found in N. moscoviensis (Fig. S4), which was shown to support growth with H2 and O2 as the sole electron donor and acceptor, respectively (18, 19). No other hydrogenase genes were found in the DJ or MSP genomes despite the fact that other NOB genomes encode several additional classes of hydrogenases, including FeFe-hydrogenase (HydABC) in Nitrospira japonica NJ1 (42), group 3d in “Ca. Nitrotoga” (33), and 1h (formerly named 5) in Nitrolancea hollandica (15). Taken together, the MSP and DJ NOB cells have the genomic potential to oxidize hydrogen as an alternative electron source, although further physiological studies are needed to confirm activity. Expression of the predicted hydrogenases in MSP and DJ NOB cells may facilitate survival and/or growth under anaerobic conditions (coupled with fermentation for group 3b or by using nitrate as an electron acceptor for 2a), which could expand the metabolic versatility of these marine organisms.

Carbon metabolism.

NOB within the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures were capable of aerobic chemolithoautotrophy with nitrite as the sole electron source, carbon dioxide (CO2) as the sole carbon source, and oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor. The MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded proteins (e.g., ATP-citrate lyase, ACL, and pyruvate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, POR) involved in the reverse tricarboxylic acid (rTCA) cycle for carbon fixation (Fig. 3), as previously reported from other NOB in the Nitrospira and Nitrospina genera (34, 41). Some rTCA genes (e.g., 2-oxoglutarate ferredoxin oxidoreductase, OGOR) were not identified in the MSP and DJ NOB genomes, which may have been a result of the incomplete nature of the genomes. The missing ACL gene in the MSP NOB genome may have been replaced by a citryl-coenzyme A (CoA) synthetase gene (ccsA was identified in MSP), as previously described (52). The rTCA cycle has been found in anaerobic or microaerophilic microorganisms, including extremophilic microorganisms (52), and ferredoxin-linked enzymes in the pathway (POR and OGOR) are oxygen sensitive (53), suggesting that these NOB are capable of fixing carbon under microoxic conditions (34, 41, 53). NOB genomes of the genera Nitrobacter, Nitrococcus, Thiocapsa, Nitrolancea, and “Ca. Nitrotoga” have genes coding for the complete Calvin-Benson-Bassham (CBB) cycle supporting CO2 fixation (15, 16, 33, 40, 46); however, key enzymes (e.g., ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase and ribulose-5-phosphate kinase) of the CBB pathway were absent from the MSP and DJ NOB genomes.

Both of the MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded proteins involved in the Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) pathway for glycolysis, gluconeogenesis, the pentose phosphate (PP) pathway, and the TCA cycle. Interestingly, the EMP pathway is commonly found in anaerobes and is thought to correlate to oxygen requirements, whereas the Entner-Doudoroff glycolytic pathway is more commonly present in (facultative) aerobes (54). Both genomes also encoded proteins involved in sugar transport, pyruvate and formate assimilation, and carbon storage as glycogens (Fig. 3 and Table S3). Overall, these results suggest that the MSP and DJ NOB cells have the genetic potential to utilize organic matter for carbon or energy, although this has not been confirmed in culture.

Response to environmental conditions.

Both of the MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded several classes of proteins involved in response to environmental stress, including multidrug efflux systems, transporters for heavy metal, antibiotic resistance (beta-lactamase), and arsenic resistance (Fig. 3 and Table S3). As previously reported in other NOB (41, 55, 56), the MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded chlorite dismutase (Cld) proteins, likely located in the cytoplasm (no signal peptides predicted by SignalP 5.0 [57]), where they could detoxify chlorite (ClO2−) by converting it into chloride and oxygen. Chlorite might be produced by NXR when nitrite is oxidized with chlorate as an electron acceptor under anoxic environmental conditions (see reference 56 and references cited therein).

Similar to the N. gracilis and “Ca. N. defluvii” genomes (34, 41), the MSP and DJ NOB genomes lacked canonical key genes encoding proteins involved in defense against reactive oxygen species (ROS) present in most aerobic organisms. However, the MSP and DJ NOB genomes encoded proteins for a superoxide dismutase (SOD) with a copper/zinc metal cofactor in MSP and an iron cofactor in DJ. The Nitrospira lenta genome encodes a manganese SOD (43). SODs are commonly classified by the type of metal cofactor, with Cu/Zn SODs mainly identified for Gram-negative bacterial pathogens and eukaryotes, while Mn/Fe SODs are associated with more diverse microorganisms, including Archaea (58). In addition, these two SODs have different locations in the cell: Mn/Fe SOD in intracellular/cytosolic and Cu/Zn SOD in extracellular/periplasmic locations (59). The DJ genome encoded proteins for catalase and a glutathione peroxidase homolog (BtuE). Although the MSP genome contained no known catalase genes, degradation for hydrogen peroxide might be mediated via genes encoding antioxidant enzymes in the peroxiredoxin family, including alkyl hydroperoxide reductase (AhpC) and thiol peroxidase (Tpx) and bacterioferritin comigratory protein (Bcp) as a putative peroxidase (60, 61).

The MSP and DJ NOB genomes contained genes coding for methyl-accepting chemotaxis proteins (mcp) and putative aerotaxis receptors (aer), which allow cells to detect and respond to oxygen concentrations. Similar to most nitrifiers (see references in reference 42), genes encoding FlrABC and MotAB (flagellum motor) proteins for type III flagellum synthesis were identified in both genomes, although several flagellar genes were missing from the assemblies (likely a result of incomplete genome sequences). No genes for twitching motility via a type IV pilus assembly were found in either genome. The potential for flagellar motility is likely beneficial within sediments with transitioning redox zones and variability in substrate availability.

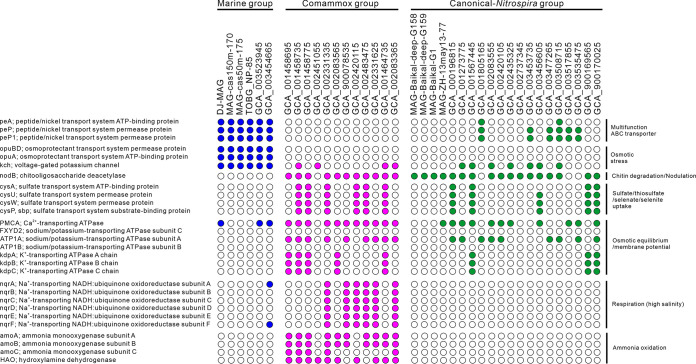

Consistent with the enrichment of MSP and DJ cultures from marine habitats with about 3.7% salt, genes coding for an osmoprotectant transport system (OpuABD) were identified in both genomes. Only the DJ NOB genome contained genes coding for osmolarity sensor protein (EnvZ) and transcriptional regulatory protein (OmpR), reported to be expressed in response to osmotic stress (60) and shown to regulate flagellar gene expression (62). Only the DJ NOB genome encoded proteins involved in trehalose biosynthesis, such as trehalose and maltose phosphorylases (TreP) and maltooligosyl trehalose synthase (TreYZ) (63). Expression of these proteins may contribute to the broader salt tolerance found in the DJ enrichment culture (0 to 5% NaCl) compared to the MSP enrichment culture (3% only). This suggests that related Nitrospirota NOB have an ecological advantage for habitat adaptation against a competitive NOB (i.e., Nitrospinota NOB) in marine environments. Recent studies claimed that some proteins (e.g., sodium-translocating NADH:quinone oxidoreductase, NQR, involved in energy generation by sodium pumping) involved in adaptation to high salinity have been associated with a transition from freshwater to marine habitats (see references in reference 64). Unexpectedly, no nqr genes (nqrABCDEF) were identified in the genomes from the marine NOB, including DJ and canonical Nitrospira (Fig. 5). Genes encoding K+-transporting ATPase (KdpABC) and Na+/K+-transporting ATPase were found within some of the comammox and canonical Nitrospira genomes but not within the marine group genomes. On the other hand, marine and canonical Nitrospirota and Nitrospinota genomes encoded H+-translocating NADH-quinone oxidoreductase (NDH) proteins, which are energetically more efficient under low-salinity conditions (65).

FIG 5.

Predicted distribution of Nitrospirota genes encoding proteins for membrane transport, osmotic stress response, chitin degradation, and respiration. Closed and open circles refer to cases in which a homolog was present in or absent from the MAGs. The MAGs were separated according to the phylogenomic analysis.

Cobalamin synthesis.

Cobalamin (vitamin B12) is required as an essential cofactor by many organisms (66). However, cobalamin biosynthesis is confined to a few prokaryotes, such as Cyanobacteria, Alphaproteobacteria, Gammaproteobacteria, Bacteroidetes, Haloarchaea, and Thaumarchaeota (67, 68). In addition, some microbes synthesize cobalamin via a salvage pathway by corrinoid uptake (69). To our knowledge, no study has experimentally reported cobalamin synthesis in marine NOB (complex vitamins, including vitamin B12, are regularly supplied as a growth factor in culture medium for most strains of NOB). Ngugi et al. (17) claimed that Nitrospinae (“Ca. Nitromaritima” and N. gracilis) members are scavengers for vitamin B12 supplied by cobalamin producers (e.g., ammonia-oxidizing archaea [70]). The NOB “Ca. N. defluvii” (enriched from activated sludge) genome encodes proteins for an anaerobic cobalamin biosynthesis pathway (34).

The MSP and DJ NOB genomes contain many genes predicted to be involved in cobalamin biosynthesis via a salvage pathway (Table S4). In the salvage pathway, BtuBCDF transport proteins might be key enzymes for corrinoid (e.g., cobinamide) uptake (71), but many of the BtuBCDF genes were missing from the MSP and DJ NOB genomes. This function might be replaced by FepBDC (Fe3+-hydroxamate transport system) (72), based on the similar molecular structure between corrinoid and Fe3+-hydroxamate (73). Many additional MAGs in the Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota phyla also had gene repertoires for (an)aerobic and salvage pathways for cobalamin synthesis, although some genes were missing (Table S4).

The predicted genomic potential for cobalamin synthesis was tested in culture by growing the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures in standard medium, medium without any vitamin mixture, and medium with a vitamin mixture prepared without cobalamin. If the MSP and DJ NOB cells can synthesize cobalamin on their own, then they should grow and oxidize nitrite under cobalamin-deficient conditions. The results showed that the DJ and MSP NOB cells grew (based on 16S rRNA gene copy number measurements) and oxidized nitrite in the absence of cobalamin (Fig. S5), suggesting an active cobalamin biosynthesis pathway. Alternatively, these results indicate that the DJ and MSP NOB can take up vitamin B12 synthesized by other bacteria within the enrichment culture. These results tentatively suggest that Nitrospinota and Nitrospirota are cobalamin producers in marine environments and that they provide essential metabolites to other community members.

Conclusions.

Ecophysiological characterizations for marine NOB remain largely unexplored (compared to nonmarine NOB) due in large part to the small number of cultured representatives. Here, two novel NOB were cultured from marine sediments. Physiology assays demonstrated nitrite oxidation under various conditions. The genomes of these two marine NOB encoded proteins for many key metabolic capabilities shared with other NOB groups. Analysis of the MSP and DJ NOB genome sequences revealed predicted traits that likely influence the ecology of these organisms, including tentative cobalamin production, anaerobic metabolisms, and interaction with other organisms. Future investigations will focus on validating genomic predictions and discerning potential niche adaptation of these novel NOB marine groups.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cultivation and growth.

Two marine sediment samples were collected using a box core sampler. The samples were designated MSP, from near Moseulpo (sampling depth, 0.3 m; 33.13′N 126.14′E), and DJ, from near Daejeong (sampling depth, 1.5 m; 33.13′N 126.13′E), near Jeju Island in the Republic of Korea. Marine sediment samples were inoculated into artificial seawater (ASW) medium and incubated at 26°C under dark conditions with 0.1 mM nitrite as the sole energy and nitrogen source (nitrite concentrations were increased to 0.2 mM for further enrichment), 3 mM sodium bicarbonate as a carbon source, 0.1 mM potassium phosphate, 1× trace element mixtures, and vitamin solution (74). The components of basal ASW medium contained, per liter, 24.6 g NaCl, 6.29 g MgSO4·7H2O, 4.66 g MgCl2·6H2O, 0.67 g KCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, and 1.36 g CaCl2·2H2O. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7.5 with NaOH or HCl with 5 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0). Approximately every 2 weeks for a period of 2 years, 5% (vol/vol) of the total culture volume was transferred to fresh medium under dark, static conditions. Enrichment of NOB was enhanced by rapid transfer at the beginning of nitrite oxidation and serial dilution to extinction (2 times), where the highest dilution showing nitrite oxidation activity was transferred to fresh media. Unless otherwise stated, each starting batch culture was supplemented with 0.2 mM nitrite as the sole energy source. Nitrite consumption was monitored using Griess color reagents (75).

Nitrite oxidation rates for optimal concentrations of nitrite (0 to 0.5 mM) and salt (0 to 5%, wt/vol, NaCl) were estimated in triplicate for each enrichment culture using culture conditions described above, with the exception of varied nitrite concentrations. To determine optimal salt concentrations for growth, we used a low-salt medium supplied with 0.2 mM nitrite, which contained, per liter, 0.4 g MgCl2·6H2O, 0.5 g KCl, 0.2 g KH2PO4, and 0.1 g CaCl2·2H2O.

The predicted genomic potential for cobalamin synthesis was tested in culture by growing the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures in standard medium, medium without any vitamin mixture, and medium with vitamin mixture prepared without cobalamin. Other components of the enrichment culture (e.g., basal medium, temperature, and darkness) were maintained as described above with 0.2 mM nitrite. After 2 weeks, nitrite consumption was determined using Griess color reagents (75). NOB abundance was estimated based on 16S rRNA gene qPCR as described below.

Community composition of the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures.

Community composition of the enrichment cultures (including confirmation of only one NOB per culture) was determined by extracting DNA at the mid-log phase of exponential nitrite oxidation and constructing the bacterial 16S rRNA gene clone library (76), as described previously.

For nitrite oxidizer identification, PCR, DNA sequencing, and bioinformatics analysis were employed as described previously (77, 78). Briefly, paired-end sequencing of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene (targeting the V4 hypervariable region) was performed using the MiSeq system (Illumina, San Diego, CA).

Abundance estimates of NOB within the MSP and DJ enrichment cultures.

For estimation of 16S rRNA gene copy number per milliliter of culture, qPCR experiments were conducted using the CFX Connect real-time system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) and built-in CFX manager software (version 3.0; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). DNA extracted from the MSP and DJ cultures was amplified using the primers up-ntspn693R (5′-TTCCCAATATCAAYGCATTT-3′) and ntspa712R (5′-CCTTCGCCACCGGCCTTC-3′), respectively, along with universal bacterial primer 518F (5′-ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG-3′) (79, 80). The up-ntspn693R primer was slightly modified to include a nucleotide degeneracy to increase coverage of the MSP NOB (based on comparison between the published primer sequence and prior clone library 16S rRNA genes sequenced from the MSP culture). The thermal cycling parameters were 15 min at 95°C for initial denaturation and then 40 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 55°C, and 30 s at 72°C, with fluorescence readings taken between each cycle. To estimate gene abundances per milliliter of culture, standard curves were generated for each run by using linearized reference gene standards, ranging from 0 to 109 gene copies per reaction, as described previously (76, 81). The specificity of the amplification of 16S rRNA gene fragments was tested by analyzing melting curves, checking the sizes of reaction products by gel electrophoresis, and sequencing the reaction products. Unless otherwise stated, 16S rRNA gene copy numbers were determined in triplicate for each enrichment culture.

Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was used to observe the relative enrichment of NOB in the MSP and DJ cultures. Cells were harvested from 10 ml of culture after complete nitrite consumption and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, as described previously (76, 82). The paraformaldehyde-fixed samples were hybridized with a 6-carboxyfluorescein (FAM)-labeled bacterium-specific probe (EUB338) (82), along with a Cy5-labeled Nitrospina-specific probe (nsn227, 5′-ATGGTCCGCGAACTCATC-3′) (83) for MSP and a Texas Red-labeled Nitrospira-specific modified probe (662up, 5′-GGAATTCCCGGTGTAGCG-3′) (84) for DJ. The general nucleic acid stain DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) was used to observe the total number of cells for relative NOB enrichment estimates. The samples were observed with a DM2500 fluorescence microscope (Leica Microsystems, Germany) using an oil-immersion objective (see Fig. S6 in the supplemental material). The Nitrospira-specific modified probe (662up) was slightly modified based on clone library sequences from the DJ culture.

DNA extraction and genomic sequencing of enrichment cultures.

For metagenome sequencing of the enrichment cultures, cells were harvested by filtration (0.22-μm pore size; Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) of 200 ml of each culture after complete nitrite consumption. Genomic DNA (gDNA) was isolated from the filters using a commercial gDNA extraction kit (GeneAll Biotechnology Co. Ltd., Republic of Korea) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA integrity was verified by agarose gel (1%, wt/vol) electrophoresis with ethidium bromide staining. A gDNA library was prepared by following the protocol provided by Pacific Biosciences (PacBio; Menlo Park, CA) with single-molecule real-time (SMRT) Bell 8Pac V3 and TruSeq SBS kit v3 for Pacific Biosciences PSII and Illumina HiSeq 4000 (Illumina, San Diego, CA) sequencers, respectively, at Macrogen, Inc. (Seoul, Republic of Korea).

Assembly, binning, and annotation.

All reads sequenced by PacBio and Illumina from each enrichment culture were assembled de novo with SPAdes v3.12.0 (85) using default parameters and a custom k-mer list: 41, 51, 61, 71, 81, 91, 101, 111, 121, and 127. Raw reads sequenced by Illumina after passing filtering were used for contig assembly by tools provided in BBMap (86) (https://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/). In brief, bbduk.sh was employed to remove poor-quality reads (qtrim = rl trimq = 18), to identify phiX and p-Fosil2 control reads (k = 21 ref = vectorfile ordered cardinality), and to remove Illumina adapters (k = 21 ref = adapterfile ordered cardinality).

A total of about 9.7 Gbp of raw read sequences were obtained from the two cultures (MSP, 5.08 Gbp; DJ, 4.69 Gbp), with de novo assembly resulting in 3,323 and 1,511 contigs of >5 kb for MSP and DJ, respectively. Only >5-kb contigs assembled de novo in this study were binned by a combination of taxonomy-dependent and taxonomy-independent approaches. For taxonomy-dependent binning, genes were predicted using Prodigal (87) followed by comparisons against the NCBI NR database, as described previously (88, 89). To achieve taxonomy-independent binning, contigs were mapped using bbwrap.sh (90) (kfilter = 31, subfilter = 15, maxindel = 80) against metagenomic data sets, and contig abundances were calculated using jgi_summarize_bam_contig_depths (91) with default settings. Contig abundance information was used in MetaBAT2 (92) (default parameters) to achieve automated binning of contigs, as described previously (88). After a hybrid binning strategy (taxonomy dependent and independent), these contigs were separated into 43 (MSP) and 16 (DJ) genome bins. Bin completeness and contamination were estimated using the lineage workflow of CheckM v1.0.12 (30) (Table S2). Finally, based on the results for binning and annotation, bins related to the genera Nitrospina (n = 56 contigs) and Nitrospira (n = 1 contig) were selected and denominated as MSP- and DJ-MAG, respectively. To confirm taxonomic affiliation of selected bins, the two MAGs were classified using GTDB-Tk (93) with default settings.

Annotation of predicted genes with KO (KO numbers) and cluster of orthologous groups (COGs) (94) was achieved using BlastKOALA (95) and RPS-BLAST (reversed-position-specific BLAST) (96). Metabolic pathways and general biological functions were inferred using online KEGG mapping tools (https://www.genome.jp/kegg/mapper.html). Genes encoding ribosomal RNAs (rRNA) and transfer RNAs (tRNA) were predicted using the bacterial rRNA predictor (Barrnap; https://github.com/tseemann/barrnap) and tRNAscan-SE (97), respectively. Protein domains were annotated with InterProScan (98).

Genome and phylogenomic analyses.

Publicly available genomes and MAGs belonging to Nitrospinota (n = 31) and Nitrospirota (n = 30) were downloaded from the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDBp; https://gtdb.ecogenomic.org/), and newly assembled environmental MAGs were affiliated with Nitrospinota (n = 2, Caspian Sea [99]) and Nitrospirota (n = 6, Lake Baikal [100] and Lake Zurich [101]). Details regarding geographic location, collection date, isolation source, accession numbers for BioProject and SRR, and sequence statistics of all MAGs used in this study are summarized in Table S1.

Phylogenomic analyses included the MSP and DJ culture genomes (n = 2) and other MAGs/genomes (n = 69). Single-copy marker genes (n = 161; Table S5) were used to infer concatenated protein phylogeny as previously described (30). MAGs were included in the phylogenomic tree inferences if they harbored at least 20% (38 markers) of total phylogenetic markers, although most MAGs (n = 74; including the Nitrospira marina genome) harbored more than 50% of the markers. Individual homologous proteins were aligned using PRANK (default parameters) (102), trimmed using BMGE (-t AA -g 0.2 -b 1 -m BLOSUM65) (103), concatenated, and subjected to SR4 amino acid recoding (104). A maximum likelihood tree was generated by IQ-TREE (105) with the best-fitting substitution model assessed (GTR+F+R6 in this study) by ModelFinder (106) and ultrafast bootstrapping (-bb 1000 -alrt 1000) (107). Average nucleotide identity (ANI) and average amino acid identity (AAI) for all MAGs selected in this study were calculated as previously described (108–110). Taxonomic categories for the two MAGs were defined using the standards suggested by Konstantinidis et al. (32).

Phylogenetic analyses for 16S rRNA, NxrA, and hydrogenase sequences.

The 16S rRNA gene sequences were recovered from the MSP and DJ genomic assemblies using RNAmmer (v1.2) (111) and were confirmed to be identical to the 16S rRNA gene sequences identified from the MSP and DJ enrichment culture clone libraries. Related sequences were imported from the SILVA SSU Ref 132 database. MSP and DJ hydrogenase sequences were classified by HydDB (51). Final alignments for 16S rRNA (average length, 1,454 bp), hydrogenase (average length, 529 amino acids), and nitrite oxidoreductase subunit alpha (NxrA) and nitrate reductase subunit alpha (NarG) (average length, 1,090 amino acids) sequences were generated by PASTA (112). All maximum-likelihood trees were constructed with IQ-TREE (105) with ultrafast bootstraps (-bb 1000 -alrt 1000). All NxrA or NarG sequences (n = 86) analyzed in this study are supplied in the supplemental material.

Data availability.

The assembled genome sequences have been deposited in the BioProject public database under the accession number PRJNA548657. The data that support the findings of this paper are available in figshare with the identifier https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12097716.v2.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Research Foundation of Korea (no. 2018R1C1B6006762) and National Institute of Biological Resources, funded by the Ministry of Environment (no. NIBR202002108). A.-Ş.A. was supported by research grants 17-04828S (Grant Agency of the Czech Republic) and MSM200961801 (Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic). V.S.K. was supported by research grants 17-04828S (Grant Agency of the Czech Republic) and GAJU 158/2016/P (The Grant Agency of the Faculty of Science, University of South Bohemia). R.G. was supported by research grants 17-04828S (Grant Agency of the Czech Republic) and CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/16_025/0007417 (ERDF/ESF). A.C.M. was supported by the University of Colorado, Denver.

S.-J.P. conceived and designed the experiments; S.-J.P., A.-Ş.A., P.A.-B., V.S.K., A.C.M., and R.G. performed the experiments and analyzed the data; S.-J.P., A.-Ş.A., A.C.M., and R.G. wrote and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

We have no conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gruber N. 2008. The marine nitrogen cycle: overview and challenges, p 1–50. In Capone DG, Bronk DA, Mulholland MR, Carpenter EJ (ed), Nitrogen in the marine environment, 2nd ed Academic Press, San Diego, CA. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-372522-6.00001-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daims H, Lebedeva EV, Pjevac P, Han P, Herbold C, Albertsen M, Jehmlich N, Palatinszky M, Vierheilig J, Bulaev A, Kirkegaard RH, von Bergen M, Rattei T, Bendinger B, Nielsen PH, Wagner M. 2015. Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528:504–509. doi: 10.1038/nature16461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Kessel MA, Speth DR, Albertsen M, Nielsen PH, Op den Camp HJ, Kartal B, Jetten MS, Lucker S. 2015. Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 528:555–559. doi: 10.1038/nature16459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pinto AJ, Marcus DN, Ijaz UZ, Bautista-de Lose Santos QM, Dick GJ, Raskin L. 2016. Metagenomic evidence for the presence of comammox Nitrospira-like bacteria in a drinking water system. mSphere 1:e00054-15. doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00054-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gruber N. 2004. The dynamics of the marine nitrogen cycle and its influence on atmospheric CO2 variations, p 97–148. In Follows M, Oguz T (ed), The ocean carbon cycle and climate. Springer, Amsterdam, Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pachiadaki MG, Sintes E, Bergauer K, Brown JM, Record NR, Swan BK, Mathyer ME, Hallam SJ, Lopez-Garcia P, Takaki Y, Nunoura T, Woyke T, Herndl GJ, Stepanauskas R. 2017. Major role of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria in dark ocean carbon fixation. Science 358:1046–1051. doi: 10.1126/science.aan8260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao R, Hannisdal B, Mogollon JM, Jorgensen SL. 2019. Nitrifier abundance and diversity peak at deep redox transition zones. Sci Rep 9:8633. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44585-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lau E, Frame CH, Nolan EJT, Stewart FJ, Dillard ZW, Lukich DP, Mihalik NE, Yauch KE, Kinker MA, Waychoff SL. 2019. Diversity and relative abundance of ammonia- and nitrite-oxidizing microorganisms in the offshore Namibian hypoxic zone. PLoS One 14:e0217136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levipan HA, Molina V, Fernandez C. 2014. Nitrospina-like bacteria are the main drivers of nitrite oxidation in the seasonal upwelling area of the eastern South Pacific (central Chile approximately 36 degrees S). Environ Microbiol Rep 6:565–573. doi: 10.1111/1758-2229.12158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winogradsky S. 1982. Contributions a la morphologie des organismes de la nitrification. Arch Sci Biol 1:88–137. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abeliovich A. 2006. The nitrite oxidizing bacteria, p 861–872. In Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E (ed), The prokaryotes: volume 5: proteobacteria: alpha and beta subclasses. Springer New York, New York, NY. doi: 10.1007/0-387-30745-1_41. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lucker S, Schwarz J, Gruber-Dorninger C, Spieck E, Wagner M, Daims H. 2015. Nitrotoga-like bacteria are previously unrecognized key nitrite oxidizers in full-scale wastewater treatment plants. ISME J 9:708–720. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alawi M, Lipski A, Sanders T, Pfeiffer EM, Spieck E. 2007. Cultivation of a novel cold-adapted nitrite oxidizing betaproteobacterium from the Siberian Arctic. ISME J 1:256–264. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2007.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kitzinger K, Koch H, Lucker S, Sedlacek CJ, Herbold C, Schwarz J, Daebeler A, Mueller AJ, Lukumbuzya M, Romano S, Leisch N, Karst SM, Kirkegaard R, Albertsen M, Nielsen PH, Wagner M, Daims H. 2018. Characterization of the first “Candidatus Nitrotoga” isolate reveals metabolic versatility and separate evolution of widespread nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. mBio 9:e01186-18. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01186-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sorokin DY, Lucker S, Vejmelkova D, Kostrikina NA, Kleerebezem R, Rijpstra WI, Damste JS, Le Paslier D, Muyzer G, Wagner M, van Loosdrecht MC, Daims H. 2012. Nitrification expanded: discovery, physiology and genomics of a nitrite-oxidizing bacterium from the phylum Chloroflexi. ISME J 6:2245–2256. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sorokin DY, Vejmelkova D, Lucker S, Streshinskaya GM, Rijpstra WI, Sinninghe Damste JS, Kleerbezem R, van Loosdrecht M, Muyzer G, Daims H. 2014. Nitrolancea hollandica gen. nov., sp. nov., a chemolithoautotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium isolated from a bioreactor belonging to the phylum Chloroflexi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 64:1859–1865. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.062232-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngugi DK, Blom J, Stepanauskas R, Stingl U. 2016. Diversification and niche adaptations of Nitrospina-like bacteria in the polyextreme interfaces of Red Sea brines. ISME J 10:1383–1399. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koch H, Galushko A, Albertsen M, Schintlmeister A, Gruber-Dorninger C, Lucker S, Pelletier E, Le Paslier D, Spieck E, Richter A, Nielsen PH, Wagner M, Daims H. 2014. Growth of nitrite-oxidizing bacteria by aerobic hydrogen oxidation. Science 345:1052–1054. doi: 10.1126/science.1256985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koch H, Lucker S, Albertsen M, Kitzinger K, Herbold C, Spieck E, Nielsen PH, Wagner M, Daims H. 2015. Expanded metabolic versatility of ubiquitous nitrite-oxidizing bacteria from the genus Nitrospira. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112:11371–11376. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1506533112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Daims H, Lucker S, Wagner M. 2016. A new perspective on microbes formerly known as nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Trends Microbiol 24:699–712. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spieck E, Keuter S, Wenzel T, Bock E, Ludwig W. 2014. Characterization of a new marine nitrite oxidizing bacterium, Nitrospina watsonii sp. nov., a member of the newly proposed phylum “Nitrospinae.” Syst Appl Microbiol 37:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson SW, Waterbury JB. 1971. Characteristics of two marine nitrite oxidizing bacteria, Nitrospina gracilis nov. gen. nov. sp. and Nitrococcus mobilis nov. gen. nov. sp. Archiv Mikrobiol 77:203–230. doi: 10.1007/BF00408114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Watson SW, Bock E, Valois FW, Waterbury JB, Schlosser U. 1986. Nitrospira marina gen. nov. sp. nov.: a chemolithotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium. Arch Microbiol 144:1–7. doi: 10.1007/BF00454947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keuter S, Kruse M, Lipski A, Spieck E. 2011. Relevance of Nitrospira for nitrite oxidation in a marine recirculation aquaculture system and physiological features of a Nitrospira marina-like isolate. Environ Microbiol 13:2536–2547. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Haaijer SCM, Ji K, van Niftrik L, Hoischen A, Speth D, Jetten MSM, Sinninghe Damsté JS, Op den Camp HJM. 2013. A novel marine nitrite-oxidizing Nitrospira species from Dutch coastal North Sea water. Front Microbiol 4:60. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Off S, Alawi M, Spieck E. 2010. Enrichment and physiological characterization of a novel Nitrospira-like bacterium obtained from a marine sponge. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:4640–4646. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00320-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kruse M, Keuter S, Bakker E, Spieck E, Eggers T, Lipski A. 2013. Relevance and diversity of Nitrospira populations in biofilters of brackish RAS. PLoS One 8:e64737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wegen S, Nowka B, Spieck E. 2019. Low temperature and neutral pH define “Candidatus Nitrotoga sp.” as a competitive nitrite oxidizer in coculture with Nitrospira defluvii. Appl Environ Microbiol 85:e02569-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02569-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lebedeva EV, Alawi M, Maixner F, Jozsa PG, Daims H, Spieck E. 2008. Physiological and phylogenetic characterization of a novel lithoautotrophic nitrite-oxidizing bacterium, “Candidatus Nitrospira bockiana.” Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 58:242–250. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.65379-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parks DH, Imelfort M, Skennerton CT, Hugenholtz P, Tyson GW. 2015. CheckM: assessing the quality of microbial genomes recovered from isolates, single cells, and metagenomes. Genome Res 25:1043–1055. doi: 10.1101/gr.186072.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayer B, Saito MA, McIlvin MR, Lücker S, Moran DM, Lankiewicz TS, Dupont CL, Santoro AE. 2020. Metabolic versatility of the nitrite-oxidizing bacterium Nitrospira marina and its proteomic response to oxygen-limited conditions. bioRxiv doi: 10.1101/2020.07.02.185504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 32.Konstantinidis KT, Rossello-Mora R, Amann R. 2017. Uncultivated microbes in need of their own taxonomy. ISME J 11:2399–2406. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2017.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boddicker AM, Mosier AC. 2018. Genomic profiling of four cultivated Candidatus Nitrotoga spp. predicts broad metabolic potential and environmental distribution. ISME J 12:2864–2882. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lucker S, Wagner M, Maixner F, Pelletier E, Koch H, Vacherie B, Rattei T, Damste JS, Spieck E, Le Paslier D, Daims H. 2010. A Nitrospira metagenome illuminates the physiology and evolution of globally important nitrite-oxidizing bacteria. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:13479–13484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1003860107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stanley NR, Palmer T, Berks BC. 2000. The twin arginine consensus motif of Tat signal peptides is involved in Sec-independent protein targeting in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 275:11591–11596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.16.11591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sargent F. 2007. The twin-arginine transport system: moving folded proteins across membranes. Biochem Soc Trans 35:835–847. doi: 10.1042/BST0350835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spieck E, Ehrich S, Aamand J, Bock E. 1998. Isolation and immunocytochemical location of the nitrite-oxidizing system in Nitrospira moscoviensis. Arch Microbiol 169:225–230. doi: 10.1007/s002030050565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kobayashi S, Hira D, Yoshida K, Toyofuku M, Shida Y, Ogasawara W, Yamaguchi T, Araki N, Oshiki M. 2018. Nitric oxide production from nitrite reduction and hydroxylamine oxidation by copper-containing dissimilatory nitrite reductase (NirK) from the aerobic ammonia-oxidizing archaeon, Nitrososphaera viennensis. Microbes Environ 33:428–434. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME18058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carini P, Dupont CL, Santoro AE. 2018. Patterns of thaumarchaeal gene expression in culture and diverse marine environments. Environ Microbiol 20:2112–2124. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Starkenburg SR, Larimer FW, Stein LY, Klotz MG, Chain PS, Sayavedra-Soto LA, Poret-Peterson AT, Gentry ME, Arp DJ, Ward B, Bottomley PJ. 2008. Complete genome sequence of Nitrobacter hamburgensis X14 and comparative genomic analysis of species within the genus Nitrobacter. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:2852–2863. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02311-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lucker S, Nowka B, Rattei T, Spieck E, Daims H. 2013. The genome of Nitrospina gracilis illuminates the metabolism and evolution of the major marine nitrite oxidizer. Front Microbiol 4:27. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ushiki N, Fujitani H, Shimada Y, Morohoshi T, Sekiguchi Y, Tsuneda S. 2017. Genomic analysis of two phylogenetically distinct Nitrospira species reveals their genomic plasticity and functional diversity. Front Microbiol 8:2637. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sakoula D, Nowka B, Spieck E, Daims H, Lucker S. 2018. The draft genome sequence of “Nitrospira lenta” strain BS10, a nitrite oxidizing bacterium isolated from activated sludge. Stand Genomic Sci 13:32. doi: 10.1186/s40793-018-0338-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palatinszky M, Herbold C, Jehmlich N, Pogoda M, Han P, von Bergen M, Lagkouvardos I, Karst SM, Galushko A, Koch H, Berry D, Daims H, Wagner M. 2015. Cyanate as an energy source for nitrifiers. Nature 524:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature14856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pitcher RS, Brittain T, Watmugh NJ. 2002. Cytochrome cbb3 oxidase and bacterial microaerobic metabolism. Biochem Soc Trans 30:653–658. doi: 10.1042/bst0300653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fussel J, Lucker S, Yilmaz P, Nowka B, van Kessel M, Bourceau P, Hach PF, Littmann S, Berg J, Spieck E, Daims H, Kuypers MMM, Lam P. 2017. Adaptability as the key to success for the ubiquitous marine nitrite oxidizer Nitrococcus. Sci Adv 3:e1700807. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1700807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemp J, Lucker S, Schott J, Pace LA, Johnson JE, Schink B, Daims H, Fischer WW. 2016. Genomics of a phototrophic nitrite oxidizer: insights into the evolution of photosynthesis and nitrification. ISME J 10:2669–2678. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2016.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Borisov VB, Gennis RB, Hemp J, Verkhovsky MI. 2011. The cytochrome bd respiratory oxygen reductases. Biochim Biophys Acta 1807:1398–1413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.06.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giuffre A, Borisov VB, Arese M, Sarti P, Forte E. 2014. Cytochrome bd oxidase and bacterial tolerance to oxidative and nitrosative stress. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837:1178–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2014.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greening C, Biswas A, Carere CR, Jackson CJ, Taylor MC, Stott MB, Cook GM, Morales SE. 2016. Genomic and metagenomic surveys of hydrogenase distribution indicate H2 is a widely utilised energy source for microbial growth and survival. ISME J 10:761–777. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sondergaard D, Pedersen CN, Greening C. 2016. HydDB: a web tool for hydrogenase classification and analysis. Sci Rep 6:34212. doi: 10.1038/srep34212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hugler M, Sievert SM. 2011. Beyond the Calvin cycle: autotrophic carbon fixation in the ocean. Annu Rev Mar Sci 3:261–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120709-142712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Campbell BJ, Engel AS, Porter ML, Takai K. 2006. The versatile epsilon-proteobacteria: key players in sulphidic habitats. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:458–468. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flamholz A, Noor E, Bar-Even A, Liebermeister W, Milo R. 2013. Glycolytic strategy as a tradeoff between energy yield and protein cost. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:10039–10044. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215283110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Maixner F, Wagner M, Lucker S, Pelletier E, Schmitz-Esser S, Hace K, Spieck E, Konrat R, Le Paslier D, Daims H. 2008. Environmental genomics reveals a functional chlorite dismutase in the nitrite-oxidizing bacterium “Candidatus Nitrospira defluvii.” Environ Microbiol 10:3043–3056. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mlynek G, Sjoblom B, Kostan J, Fureder S, Maixner F, Gysel K, Furtmuller PG, Obinger C, Wagner M, Daims H, Djinovic-Carugo K. 2011. Unexpected diversity of chlorite dismutases: a catalytically efficient dimeric enzyme from Nitrobacter winogradskyi. J Bacteriol 193:2408–2417. doi: 10.1128/JB.01262-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sonderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, Nielsen H. 2019. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol 37:420–423. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller AF. 2012. Superoxide dismutases: ancient enzymes and new insights. FEBS Lett 586:585–595. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2011.10.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Broxton CN, Culotta VC. 2016. SOD enzymes and microbial pathogens: surviving the oxidative storm of infection. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005295. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cai SJ, Inouye M. 2002. EnvZ-OmpR interaction and osmoregulation in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem 277:24155–24161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jeong W, Cha MK, Kim IH. 2000. Thioredoxin-dependent hydroperoxide peroxidase activity of bacterioferritin comigratory protein (BCP) as a new member of the thiol-specific antioxidant protein (TSA)/Alkyl hydroperoxide peroxidase C (AhpC) family. J Biol Chem 275:2924–2930. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oshima T, Aiba H, Masuda Y, Kanaya S, Sugiura M, Wanner BL, Mori H, Mizuno T. 2002. Transcriptome analysis of all two-component regulatory system mutants of Escherichia coli K-12. Mol Microbiol 46:281–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.03170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iturriaga G, Suarez R, Nova-Franco B. 2009. Trehalose metabolism: from osmoprotection to signaling. Int J Mol Sci 10:3793–3810. doi: 10.3390/ijms10093793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salcher MM, Schaefle D, Kaspar M, Neuenschwander SM, Ghai R. 2019. Evolution in action: habitat transition from sediment to the pelagial leads to genome streamlining in Methylophilaceae. ISME J 13:2764–2777. doi: 10.1038/s41396-019-0471-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H, Yoshizawa S, Sun Y, Huang Y, Chu X, Gonzalez JM, Pinhassi J, Luo H. 2019. Repeated evolutionary transitions of flavobacteria from marine to non-marine habitats. Environ Microbiol 21:648–666. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.14509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA, Gomez-Consarnau L, Suffridge C, Webb EA. 2014. The role of B vitamins in marine biogeochemistry. Annu Rev Mar Sci 6:339–367. doi: 10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Durán-Viseras A, Andrei A-S, Ghai R, Sánchez-Porro C, Ventosa A. 2019. New Halonotius species provide genomics-based insights into cobalamin synthesis in Haloarchaea. Front Microbiol 10:1928. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sañudo-Wilhelmy SA, Gobler CJ, Okbamichael M, Taylor GT. 18 February 2006. Regulation of phytoplankton dynamics by vitamin B12. Geophys Res Lett doi: 10.1029/2005gl025046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fang H, Kang J, Zhang D. 2017. Microbial production of vitamin B12: a review and future perspectives. Microb Cell Fact 16:15. doi: 10.1186/s12934-017-0631-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Doxey AC, Kurtz DA, Lynch MD, Sauder LA, Neufeld JD. 2015. Aquatic metagenomes implicate Thaumarchaeota in global cobalamin production. ISME J 9:461–471. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2014.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Woodson JD, Reynolds AA, Escalante-Semerena JC. 2005. ABC transporter for corrinoids in Halobacterium sp. strain NRC-1. J Bacteriol 187:5901–5909. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.17.5901-5909.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Köster W. 1991. Iron(III) hydroxamate transport across the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. Biol Met 4:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF01135553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Koster W. 2001. ABC transporter-mediated uptake of iron, siderophores, heme and vitamin B12. Res Microbiol 152:291–301. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(01)01200-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Widdel F, Bak F. 1992. Gram-negative mesophilic sulfate-reducing bacteria, p 3352–3378. In Balows A, Trüper HG, Dworkin M, Harder W, Schleifer K-H (ed), The prokaryotes: a handbook on the biology of bacteria: ecophysiology, isolation, identification, applications. Springer New York, New York, NY. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4757-2191-1_21. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schnetger B, Lehners C. 2014. Determination of nitrate plus nitrite in small volume marine water samples using vanadium(III)chloride as a reduction agent. Mar Chem 160:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.marchem.2014.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Park BJ, Park SJ, Yoon DN, Schouten S, Sinninghe Damste JS, Rhee SK. 2010. Cultivation of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing archaea from marine sediments in coculture with sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:7575–7587. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01478-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kim YS, Kim J, Park SJ. 2015. High-throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals alterations of mouse intestinal microbiota after radiotherapy. Anaerobe 33:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Koh HW, Kim MS, Lee JS, Kim H, Park SJ. 2015. Changes in the swine gut microbiota in response to porcine epidemic diarrhea infection. Microbes Environ 30:284–287. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.ME15046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Baker GC, Smith JJ, Cowan DA. 2003. Review and re-analysis of domain-specific 16S primers. J Microbiol Methods 55:541–555. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2003.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alm EW, Oerther DB, Larsen N, Stahl DA, Raskin L. 1996. The oligonucleotide probe database. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:3557–3559. doi: 10.1128/AEM.62.10.3557-3559.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Park SJ, Park BJ, Rhee SK. 2008. Comparative analysis of archaeal 16S rRNA and amoA genes to estimate the abundance and diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in marine sediments. Extremophiles 12:605–615. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0165-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Amann RI, Binder BJ, Olson RJ, Chisholm SW, Devereux R, Stahl DA. 1990. Combination of 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with flow cytometry for analyzing mixed microbial populations. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:1919–1925. doi: 10.1128/AEM.56.6.1919-1925.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Siripong S, Kelly JJ, Stahl DA, Rittmann BE. 2006. Impact of prehybridization PCR amplification on microarray detection of nitrifying bacteria in wastewater treatment plant samples. Environ Microbiol 8:1564–1574. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2006.01047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Daims H, Nielsen JL, Nielsen PH, Schleifer KH, Wagner M. 2001. In situ characterization of Nitrospira-like nitrite-oxidizing bacteria active in wastewater treatment plants. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:5273–5284. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.11.5273-5284.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bushnell B, Rood J, Singer E. 2017. BBMerge—accurate paired shotgun read merging via overlap. PLoS One 12:e0185056. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0185056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hyatt D, Chen GL, Locascio PF, Land ML, Larimer FW, Hauser LJ. 2010. Prodigal: prokaryotic gene recognition and translation initiation site identification. BMC Bioinformatics 11:119. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-11-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Bulzu PA, Andrei AS, Salcher MM, Mehrshad M, Inoue K, Kandori H, Beja O, Ghai R, Banciu HL. 2019. Casting light on Asgardarchaeota metabolism in a sunlit microoxic niche. Nat Microbiol 4:1129–1137. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0404-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Yu WJ, Lee JW, Nguyen NL, Rhee SK, Park SJ. 2018. The characteristics and comparative analysis of methanotrophs reveal genomic insights into Methylomicrobium sp. enriched from marine sediments. Syst Appl Microbiol 41:415–426. doi: 10.1016/j.syapm.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bushnell B. 2016. BBMap short-read aligner, and other bioinformatics tools. http://sourceforge.net/projects/bbmap/. Accessed January 2019.

- 91.Kang DD, Froula J, Egan R, Wang Z. 2015. MetaBAT, an efficient tool for accurately reconstructing single genomes from complex microbial communities. PeerJ 3:e1165. doi: 10.7717/peerj.1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kang D, Li F, Kirton E, Thomas A, Egan R, An H, Wang Z. 2019. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 7:e27522v1. doi: 10.7717/peerj.7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Parks DH, Chuvochina M, Waite DW, Rinke C, Skarshewski A, Chaumeil PA, Hugenholtz P. 2018. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nat Biotechnol 36:996–1004. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Tatusov RL, Galperin MY, Natale DA, Koonin EV. 2000. The COG database: a tool for genome-scale analysis of protein functions and evolution. Nucleic Acids Res 28:33–36. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Morishima K. 2016. BlastKOALA and GhostKOALA: KEGG tools for functional characterization of genome and metagenome sequences. J Mol Biol 428:726–731. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Galperin MY, Kristensen DM, Makarova KS, Wolf YI, Koonin EV. 2017. Microbial genome analysis: the COG approach. Brief Bioinform 20:1063–1070. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbx117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. 1997. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res 25:955–964. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jones P, Binns D, Chang HY, Fraser M, Li W, McAnulla C, McWilliam H, Maslen J, Mitchell A, Nuka G, Pesseat S, Quinn AF, Sangrador-Vegas A, Scheremetjew M, Yong SY, Lopez R, Hunter S. 2014. InterProScan 5: genome-scale protein function classification. Bioinformatics 30:1236–1240. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Mehrshad M, Rodriguez-Valera F, Amoozegar MA, Lopez-Garcia P, Ghai R. 2018. The enigmatic SAR202 cluster up close: shedding light on a globally distributed dark ocean lineage involved in sulfur cycling. ISME J 12:655–668. doi: 10.1038/s41396-017-0009-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cabello-Yeves PJ, Zemskaya TI, Zakharenko AS, Sakirko MV, Ivanov VG, Ghai R, Rodriguez-Valera F. 2020. Microbiome of the deep Lake Baikal, a unique oxic bathypelagic habitat. Limnol Oceanogr 65:1471–1488. doi: 10.1002/lno.11401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mehrshad M, Salcher MM, Okazaki Y, Nakano SI, Simek K, Andrei AS, Ghai R. 2018. Hidden in plain sight-highly abundant and diverse planktonic freshwater Chloroflexi. Microbiome 6:176. doi: 10.1186/s40168-018-0563-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Loytynoja A. 2014. Phylogeny-aware alignment with PRANK. Methods Mol Biol 1079:155–170. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-646-7_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Criscuolo A, Gribaldo S. 2010. BMGE (block mapping and gathering with entropy): a new software for selection of phylogenetic informative regions from multiple sequence alignments. BMC Evol Biol 10:210. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-10-210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Susko E, Roger AJ. 2007. On reduced amino acid alphabets for phylogenetic inference. Mol Biol Evol 24:2139–2150. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nguyen LT, Schmidt HA, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ. 2015. IQ-TREE: a fast and effective stochastic algorithm for estimating maximum-likelihood phylogenies. Mol Biol Evol 32:268–274. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Kalyaanamoorthy S, Minh BQ, Wong TKF, von Haeseler A, Jermiin LS. 2017. ModelFinder: fast model selection for accurate phylogenetic estimates. Nat Methods 14:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hoang DT, Chernomor O, von Haeseler A, Minh BQ, Vinh LS. 2018. UFBoot2: improving the ultrafast bootstrap approximation. Mol Biol Evol 35:518–522. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msx281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Goris J, Konstantinidis KT, Klappenbach JA, Coenye T, Vandamme P, Tiedje JM. 2007. DNA-DNA hybridization values and their relationship to whole-genome sequence similarities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 57:81–91. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64483-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. 2005. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 102:2567–2572. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409727102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Andrei AS, Salcher MM, Mehrshad M, Rychtecky P, Znachor P, Ghai R. 2019. Niche-directed evolution modulates genome architecture in freshwater Planctomycetes. ISME J 13:1056–1071. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0332-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lagesen K, Hallin P, Rødland EA, Staerfeldt HH, Rognes T, Ussery DW. 2007. RNAmmer: consistent and rapid annotation of ribosomal RNA genes. Nucleic Acids Res 35:3100–3108. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]