S. Abortusequi is an important pathogen that can induce abortions in mares. Although S. Abortusequi has been well controlled in Europe and the United States due to strict breeding and health policies, it is still widespread in African and Asian countries and has proven difficult to control. In China, abortions caused by S. Abortusequi have also been reported in donkeys. So far, there is no commercial vaccine. Thus, exploiting alternative efficient and safe strategies to control S. Abortusequi infection is essential. In this study, a new lytic phage, PIZ SAE-01E2, infecting S. Abortusequi was isolated, and the characteristics of PIZ SAE-01E2 indicated that it has the potential for use in phage therapy. A single intraperitoneal inoculation of PIZ SAE-01E2 before or after S. Abortusequi challenge provided effective protection to all pregnant mice. Thus, PIZ SAE-01E2 showed the potential to block abortions induced by S. Abortusequi in vivo.

KEYWORDS: phage therapy, Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Abortusequi, abortion, mares, mice

ABSTRACT

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Abortusequi is a frequently reported pathogen causing abortion in mares. In this study, the preventive and therapeutic effects of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 against S. Abortusequi in a mouse model of abortion were investigated. Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 was stable at different temperatures (4 to 70°C) and pH values (pH 4 to 10) and could lyse the majority of the Salmonella serogroup O:4 and O:9 strains tested (25/28). There was no lysogeny-related, toxin, or antibiotic resistance-related gene in the genome of PIZ SAE-01E2. All of these characteristics indicate that PIZ SAE-01E2 has the potential for use in phage therapy. In in vivo experiments, 2 × 103 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 was sufficient to lead to murine abortion (gestational day 14.5) within 48 h. A single intraperitoneal inoculation of PIZ SAE-01E2 (108 PFU/mouse, multiplicity of infection = 105) 1 h before or after S. Abortusequi challenge provided effective protection to all pregnant mice (10/10). After 24 h of treatment with phage PIZ SAE-01E2, the bacterial loads in both the placenta and the uterus of the infected mice were significantly decreased (<102 CFU/g) compared to those in the placenta and the uterus of the mice in the control group (>106 CFU/g). In addition, the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the placenta and blood of the mice in the phage administration groups were significantly reduced (P < 0.05) compared to those in the placenta and blood of the mice in the control group. Altogether, these findings indicate that PIZ SAE-01E2 shows the potential to block abortions induced by S. Abortusequi in vivo.

IMPORTANCE S. Abortusequi is an important pathogen that can induce abortions in mares. Although S. Abortusequi has been well controlled in Europe and the United States due to strict breeding and health policies, it is still widespread in African and Asian countries and has proven difficult to control. In China, abortions caused by S. Abortusequi have also been reported in donkeys. So far, there is no commercial vaccine. Thus, exploiting alternative efficient and safe strategies to control S. Abortusequi infection is essential. In this study, a new lytic phage, PIZ SAE-01E2, infecting S. Abortusequi was isolated, and the characteristics of PIZ SAE-01E2 indicated that it has the potential for use in phage therapy. A single intraperitoneal inoculation of PIZ SAE-01E2 before or after S. Abortusequi challenge provided effective protection to all pregnant mice. Thus, PIZ SAE-01E2 showed the potential to block abortions induced by S. Abortusequi in vivo.

INTRODUCTION

Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Abortusequi is an important pathogen that can induce abortions in mares during late pregnancy and that can cause neonatal septicemia and polyarthritis (1–3). Moreover, mares infected with S. Abortusequi are thought to be carriers, acting as the initial source for outbreaks of S. Abortusequi infection in areas where the organism is not endemic (4). Additionally, S. Abortusequi also causes secondary bacterial infections in equid herpesvirus 1 (EHV-1)-infected animals (3, 5).

Although S. Abortusequi has been well controlled in Europe and the United States due to strict breeding and health policies, it is still widespread in African and Asian countries and has proven difficult to control (2, 3). In China, the donkey industry has been expanding in recent years, and abortions caused by S. Abortusequi have also been reported in donkeys (6, 7).

Research on the treatment of S. Abortusequi infections mainly focuses on vaccines and has included studies of live attenuated vaccines (8), killed vaccines (9) and subunit vaccines (10). However, at present, all of the studies have just been at the level of basic research and have evaluated only their ability to offer immune protection in experimental animals. So far, there is no commercial vaccine because all of these candidate vaccines suffer from major drawbacks (11). Although bacterin can provide short-term immunity and partial protection against infection, the formation of abscesses is frequently observed in vaccinated mares after its administration (8). In addition, a mutant live candidate vaccine is thought to be the best way to control S. Abortusequi infection in guinea pig (12) and cattle (13) models, but its safety in vivo cannot be fully confirmed. None of the inactivated candidate vaccines have been found to confer protection for a long duration (11). Additionally, the other physical and chemical methods used to inactivate bacteria are not very effective (11). Thus, exploiting alternative efficient and safe strategies to control S. Abortusequi infection is essential.

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy is regarded as an alternative therapeutic strategy to combat various bacterial infections mainly due to its specific bactericidal activity (14). The successful application of phage therapy against Salmonella in animal models has been reported. Bao et al. reported that phage can protect mice against a lethal infection with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis (15). Seo et al. reported that phage cocktails can effectively control Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium infection in a pig challenge model (16). Callaway et al. reported that the phage can reduce Salmonella populations in growing swine (17). However, to our knowledge, phage therapy has been studied only to control abortions caused by Brucella in mice (18).

In this study, a new lytic phage, PIZ SAE-01E2, infecting S. Abortusequi was isolated from sewage samples and characterized. The preventive and therapeutic efficiency of phage treatment was evaluated in a mouse model of abortion caused by S. Abortusequi.

RESULTS

Isolation and characterization of phage PIZ SAE-01E2.

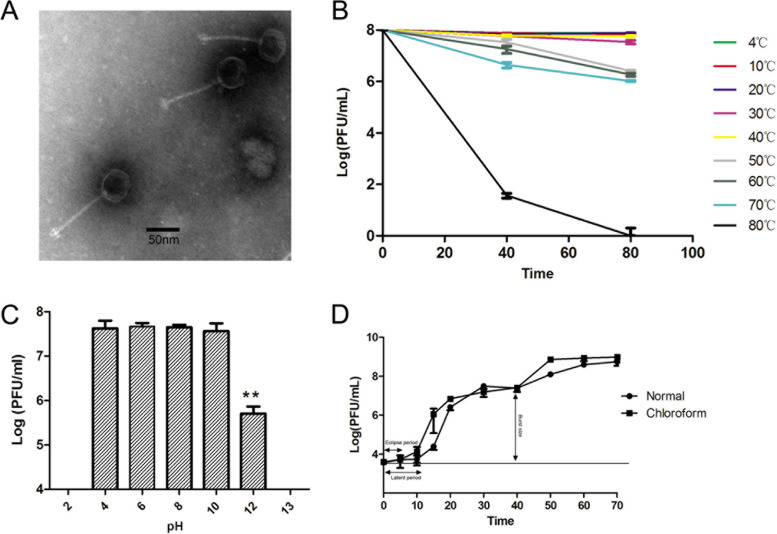

The phage PIZ SAE-01E2 was isolated from sewage samples using S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 as the host. PIZ SAE-01E2 formed clear plaques with a diameter of approximately 0.1 cm on lysogeny broth (LB) double-layer agar plates. Transmission electron microscopy showed that PIZ SAE-01E2 is comprised of an isometric head with a diameter of approximately 60 ± 5 nm, and its long and noncontractile tail (115 ± 5 nm) suggests that it belongs to the Siphoviridae family (Fig. 1A).

FIG 1.

Biological characteristics of phage PIZ SAE-01E2. (A) Transmission electron micrographs of PIZ SAE-01E2. Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 belongs to the Siphoviridae family. The diameter of its head is approximately 60 ± 5 nm, and the length of its noncontractile tails is approximately 115 ± 5 nm. (B) Temperature sensitivity of PIZ SAE-01E2. The phage titers showed no significant differences from 4°C to 40°C and decreased less than 2 log units from 50°C to 70°C. (C) pH stability of PIZ SAE-01E2. The phage titers showed no significant differences at pH values of 4 to 10; the phage titers significantly decreased at a pH value of 12 (P < 0.01). (D) One-step growth curve of PIZ SAE-01E2. The initial 5 and 10 min are an eclipse period and a latent period of PIZ SAE-01E2, respectively, and the average burst size of PIZ SAE-01E2 is approximately 215 PFU/cell. The values indicate the means and standard deviations (SD) (n = 3).

PIZ SAE-01E2 was able to infect 89% (25/28) of all Salmonella strains that belonged to serogroup O:4 (26/28) or O:9 (2/28) tested (Table 1). Additionally, phage PIZ SAE-01E2 had no lytic activity against any of the other bacteria tested. The titers of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 (against S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842) were not significantly changed at pH values of 4 to 10 after incubation for 1 h or at different temperatures ranging from 4°C to 40°C after incubation for 80 min. The phage titers were decreased 2 log units at high temperatures (50 to 70°C) (Fig. 1B and C).

TABLE 1.

Host range of phage PIZ SAE-01E2

| Bacterial strain (reference)e | Serovar | Serogroup | Phage sensitivityf |

|---|---|---|---|

| S. enterica | |||

| ATCC 9842a | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 01Epb | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| wudi1b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| wudi2b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| Yuch1b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| Yuch2b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| Yuch3b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| Yuch4b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE1b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE2b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE3b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE4b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE5b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE6b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| DE7b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| GT1b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| GT2b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 0078b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 078Hb | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 0514b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| Heze1b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 23EEb | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| 01D3b | S. Abortusequi | O:4 | + |

| SDc | S. Dublin | O:9 | + |

| STc | S. Typhimurium | O:4 | + |

| SPc (CICC-10437) | S. Paratyphi β | O:4 | − |

| S06004c (34) | S. Pullorum | O:9 | − |

| SL1344c (35) | S. Typhimurium | O:4 | − |

| E. coli | |||

| 011Db (33) | O:1 | − | |

| E. coli-2c | O:1 | − | |

| E. coli-3c | O:1 | − | |

| E. coli-4c | O:50 | − | |

| FHJU-1d | O:145 | − | |

| FHJU-2d | O:145 | − | |

| FHJU-3d | O:145 | − | |

| FHJU-4d | O:145 | − | |

| K. pneumoniae K7c (36) | − | ||

| S. aureus N38c (37) | − | ||

| E. faecalis GF29c (21) | − |

Purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC).

Isolated from donkey farms (Shandong, China).

Laboratory-preserved strains.

Collected from the First Hospital of Jilin University.

S. enterica S06004, S. enterica SL1344, E. coli 011D, K. pneumoniae K7, S. aureus N38, and E. faecalis GF29 have been reported in previous studies. All Salmonella strains isolated from donkey farms were identified as described in Materials and Methods; all E. coli strains were identified as described previously (33), and their serotypes were determined with Escherichia antiserum (Ningbo Tianrun Biological Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; Zhejiang, China).

+, transparent plaques were observed; −, no plaques were observed.

As shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material, phage PIZ SAE-01E2 could infect and lyse Salmonella over a broad range of multiplicities of infection (MOIs), and it replicated efficiently. A one-step growth curve showed that the eclipse and latent periods of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 were 5 min and 10 min, respectively. The burst size of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 was 215 PFU/cell (Fig. 1D).

General features of the PIZ SAE-01E2 genome.

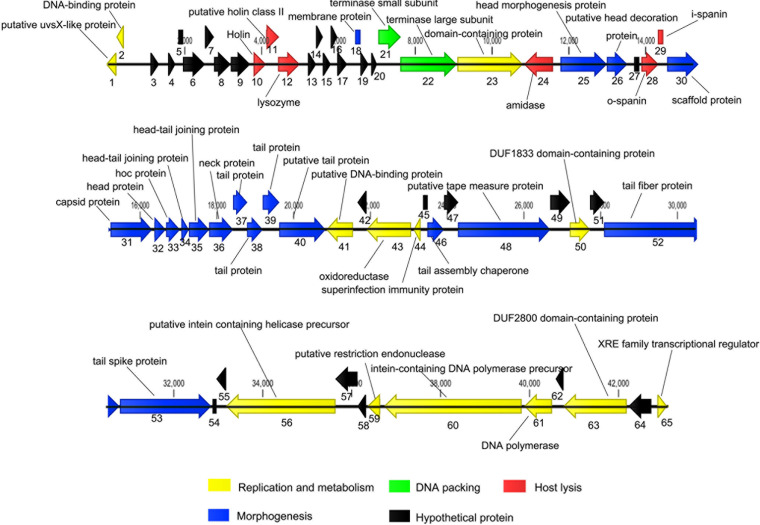

The complete genome sequence of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 is available in GenBank under accession number MN336266. The genome of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 is linear and double-stranded DNA, which is comprised of 43,097 bp with a GC content of 49.63%. A total of 65 open reading frames (ORFs) were predicted by use of the rapid annotations using subsystems technology (RAST) (Table S1). PIZ SAE-01E2 could further be classified into the subfamily Jerseyvirinae on the basis of its genomic size (40.7 to 43.6 kb), GC content (49.6 to 51.4%), and number of ORFs (48 to 69). All phages in this subfamily that have been reported are strictly lytic phages (19).

Approximately 38% of the ORFs in the genome of PIZ SAE-01E2 were annotated as encoding hypothetical proteins (Fig. 2). The other functional ORFs could be divided into four modules: morphogenesis, DNA packing, host lysis, and replication and metabolism. No tRNA was found in its genome, suggesting that phage PIZ SAE-01E2 may rely on the tRNAs of the host. There is no lysogeny-related gene, indicating that it proliferates by a lytic lifestyle. Additionally, no toxin-encoding or antibiotic resistance-conferring genes were identified in the genome of PIZ SAE-01E2.

FIG 2.

The genome of phage PIZ SAE-01E2. The CLC Genomics Workbench (version 8.1) program was employed to visualize the putative ORFs and their direction of transcription. The direction of the arrows represents the direction of gene transcription. The different colors represent different functional modules. The putative functions and names of the genes are listed.

The genome sequence of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 showed approximately 94% similarity with the genomes of four Salmonella phages and a Xanthomonas phage, namely, BPS11Q3 (GenBank accession number KX405002.1), BPS11T2 (GenBank accession number MG646668.1), wksl3 (GenBank accession number JX202565.1), vB_SenS-Ent2 (GenBank accession number HG934469.1), and f29-Xaj (GenBank accession number KU595434.1). The phylogenetic tree of its terminase large subunit showed that phage PIZ SAE-01E2 shares a close relationship to six known Salmonella phages (Fig. S2), and all of them were predicted to belong to the genus Jerseylikevirus.

In vitro bactericidal effect of phage PIZ SAE-01E2.

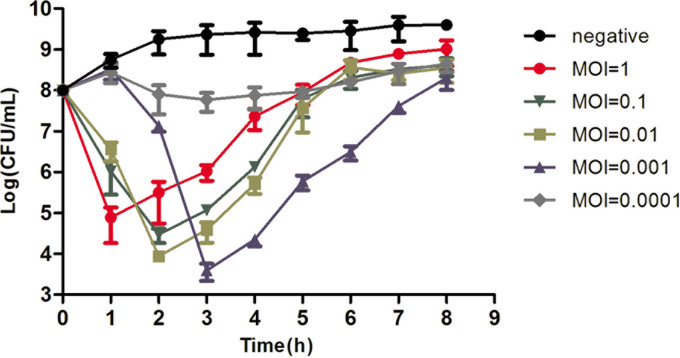

As shown in Fig. 3, the numbers of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 bacteria rapidly decreased after incubation with phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at MOIs of 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, and 1 within the first 2 to 3 h. The number of bacteria reached the inflection point at different times. When the MOI was equal to 1, the bacterial numbers reached 4.9 log units at 1 h; when the MOI was equal to 0.1, the bacterial numbers reached 4.5 log units at 2 h; when the MOI was equal to 0.01, the bacterial numbers reached 4 log units at 2 h; and when the MOI was equal to 0.001, the bacterial numbers reached 3.4 log units at 3 h. After reaching the inflection point, the bacteria grew very fast.

FIG 3.

Bactericidal activity of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 in vitro. S. Abortusequi bacteria were cocultured with phage PIZ SAE-01E2 in LB medium at different MOIs. S. Abortusequi bacteria not infected with phage were used as a negative control. The bacterial numbers were counted at the indicated time points. The values represent means and SD (n = 3).

As shown in Fig. S3, phage titers were also determined. When the bacterial curves reached the inflection point, the phage titers reached their maximum value, and they showed no significant change after that time. The bacteria proliferating in the later period showed resistance to phage PIZ SAE-01E2.

S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 causes abortion in pregnant mice.

As shown in Table 2, infection with 2 × 103 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 was enough to induce abortion in all pregnant mice (gestational day [GD] 14.5) within 48 h. However, this challenge dose had no effect on the mice in early or midpregnancy (GD 3.5 to 9.5). Infection with 2 × 104 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi caused the mice to abort within 24 h when they were infected on GD 14.5, but the effect was unstable in mice in the early or middle period of pregnancy. When the challenge dose was increased to 2 × 105 CFU/mouse, all pregnant mice showed conjunctival congestion, exhibited diarrhea, and died within 12 h.

TABLE 2.

The abortion rates of mice infected with different doses of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 at different gestational dayse

| Infection dose (no. of CFU/mouse) | No. of mice that aborted/no. of mice infected on the following GD: |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.5 | 4.5 | 6.5 | 9.5 | 14.5 | Nonpregnant mice | |

| 2 × 103 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 5/5a | 0/5 |

| 2 × 104 | 0/5 | 0/5 | 2/5c | 3/5c | 5/5b | 0/5 |

| 2 × 105 | 5/5d | 5/5d | 5/5d | 5/5d | 5/5d | 0/5 |

Abortion within between 24 and 48 h.

Abortion within 24 h.

The fur was messy, but the mice did not abort.

The mice died within 12 h.

Mice at different gestational days were infected with 2 × 103 CFU/mouse, 2 × 104 CFU/mouse, or 2 × 105 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842. The abortion of mice was monitored continuously. Nonpregnant mice received the same dose challenge and were used as a negative control.

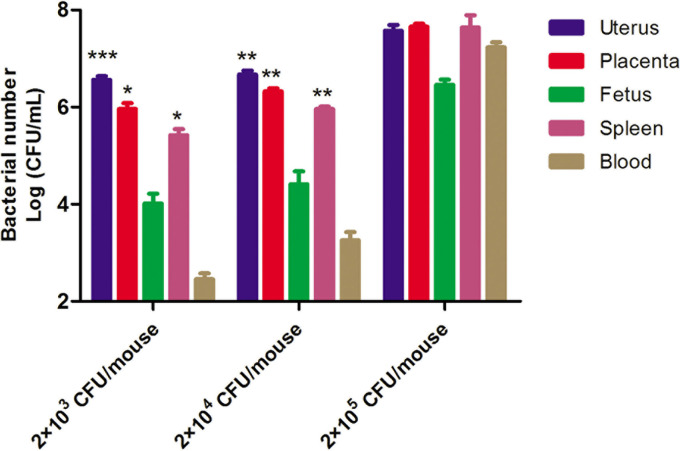

As shown in Fig. 4, in the group challenged with 2 × 103 CFU/mouse S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842, the load of S. Abortusequi in the uterus and placenta reached 3.02 × 106 CFU/g and 6.84 × 105 CFU/g, respectively, which was much higher than that in the fetuses (9.05 × 103 CFU/g). In addition, the bacterial load in the spleen increased to 2.65 × 105 CFU/g, which was close to that in the reproductive organs. Meanwhile, only 2.85 × 102 CFU/ml bacteria were found in the blood. When the challenge dose was 2 × 104 CFU/mouse, the bacterial loads in different tissues, especially in the spleen and blood, of the mice were increased compared to those in the group challenged with 2 × 103 CFU/mouse. In the group challenged with 2 × 105 CFU/mouse, up to 106 to 107 CFU/g and up to 107 CFU/ml were detected in all organs and in the blood, respectively, indicating that a high dose of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 caused bacteremia. Thus, for the murine infection model of abortion, the optimal challenge dose was considered to be 2 × 103 CFU/mouse at GD 14.5.

FIG 4.

Bacterial load in abortive mice. Mice on gestational days (GD) 3.5, 4,5, 6.5, 9.5, and 14.5 were selected and challenged with 2 × 103, 2 × 104, or 2 × 105 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842. The dying mice and all abortive mice were immediately euthanized. Different organs were homogenized, and a suspension was used to count the load of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842. When challenged with 2 × 103 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842, the bacterial load in the uterus was significantly higher than that in the fetus (P < 0.001) and the bacterial loads in the placenta and spleen were significantly higher than the bacterial load in the fetus (P < 0.01). When challenged with 2 × 104 CFU/mouse of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842, the bacterial loads in the uterus, placenta, and spleen were significantly higher than the bacterial load in the fetus (P < 0.01). The values represent the means and SD (n = 5). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 causes no side effects in pregnant mice.

After high-dose (109-PFU/mouse) phage PIZ SAE-01E2 injection, mice on GD 14.5 did not show any abnormal behavior or obvious symptoms until they gave birth compared to mice treated with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Fig. S4). Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 showed no significant effects on the fetuses or the fetal weight of the mice (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Average fetal weight and FGR analysis of high-dose phage PIZ SAE-01E2-injected mice and healthy mice

| Fetal growtha | Mean ± SD fetal wt (no. of mice with FGR or NFW/no. of mice tested)b

|

|

|---|---|---|

| PBS-treated mice | PIZ SAE-01E2-treated mice | |

| FGR | 1.072 ± 0.053 (5/60) | 1.054 ± 0.044 (5/62) |

| NFW | 1.452 ± 0.061 (55/60) | 1.602 ± 0.087 (57/62) |

FGR, fetal growth restriction; NFW, normal fetal weight.

Twenty mice were injected with PIZ SAE-01E2 at a dose of 109 PFU/mouse or PBS on gestational day 14.5. The fetuses were weighed, and fetal growth restriction was evaluated as described in Materials and Methods. All of the data are expressed as the means ± SD.

Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 protects pregnant mice from abortion caused by S. Abortusequi infection.

As shown in Table 4, all pregnant mice in the S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842-infected group aborted within 2 days. When the infected pregnant mice were treated with a single dose of 107 PFU/mouse of PIZ SAE-01E2 before or after S. Abortusequi challenge, 30% (3/10) and 40% (4/10) of the pregnant mice were protected from abortion, respectively. However, the health scores of the pregnant mice were significantly lower than those of the mice in the control group (Fig. S5). Additionally, the fetal growth restriction (FGR) rates of the fetuses from female mice of the pretreated and treated groups were up to 39% (15/38) and 21% (10/48), respectively (Table S2). In contrast, in both the pretreated group and the treated group, a dose of 108 PFU/mouse of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 provided 100% protection (10/10) to all pregnant mice. The health score of female mice in the treated group showed no significant difference from that of the control group, and the average FGR rate of the fetuses from female mice in the treated group showed no significant difference from that of the control group (Fig. S5; Table S2).

TABLE 4.

Protective effect of phage PIZ SAE-01E2

| Groupa | Dose of phage | No. of mice that aborted (total no. of mice tested) after infection on GD: |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15.5 | 16.5 | 17.5 | 18.5 | ||

| Infected | 2 × 103 CFU/mouse | 10 (10) | |||

| Phage treated | 106 PFU/mouse | 10 (10) | |||

| 107 PFU/mouse | 3 (10) | 4 (7) | |||

| 108 PFU/mouse | |||||

| Phage pretreated | 106 PFU/mouse | 10 (10) | |||

| 107 PFU/mouse | 3 (10) | 3 (7) | |||

| 108 PFU/mouse | |||||

| Control | PBS | ||||

The infected group was challenged with S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 at a dose of 2 × 103 CFU/mouse. The mice in the phage-treated group were treated with a single dose of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 (106 PFU/mouse, 107 PFU/mouse, or 108 PFU/mouse) at 1 h after S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 infection; mice in the phage-pretreated group were treated with a single dose of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 (106 PFU/mouse, 107 PFU/mouse, or 108 PFU/mouse) at 1 h before S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 infection. Mice in the control group were injected with PBS. Each group contained 10 mice.

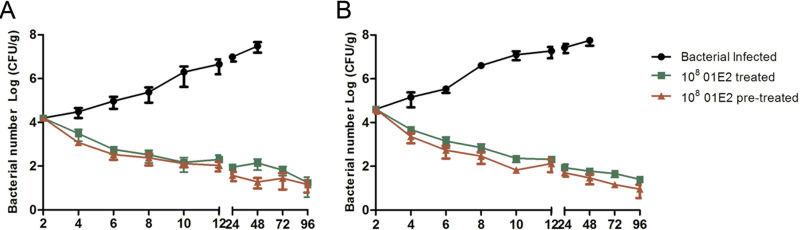

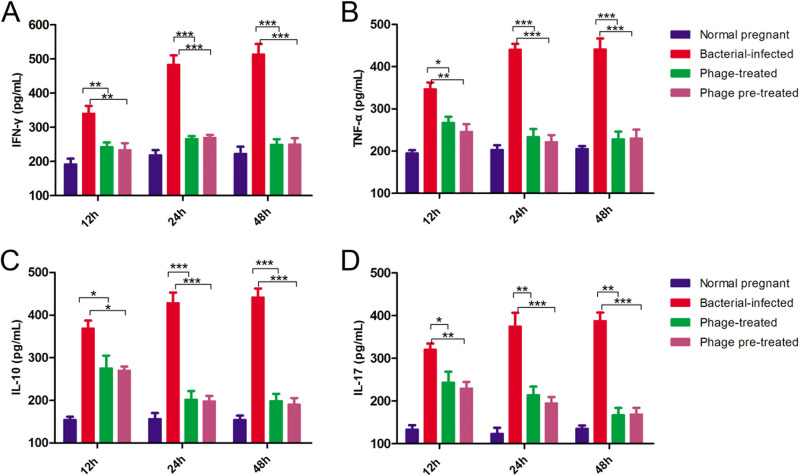

The bacterial loads in the uterus and placenta were up to 2 × 107 CFU/g and 9 × 106 CFU/g, respectively, after 24 h of bacterial infection (Fig. 5A and B). In contrast, the bacterial loads significantly decreased to approximately 104 CFU/g when the mice were treated or pretreated with phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at a dose of 108 PFU/mouse (P < 0.01). As seen in Fig. 6 and Fig. S6, the gamma interferon (IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-10 (IL-10), and IL-17 levels in the placenta and serum of the challenged mice were significantly (P < 0.05) increased after 12 h of bacterial challenge compared to those in the placenta and serum of the healthy pregnant mice. In contrast, the levels of these cytokines were significantly (P < 0.0001) decreased nearly to the normal level by phage PIZ SAE-01E2 administration. In addition, similar results were seen for the cytokine levels in serum.

FIG 5.

Bacterial loads in the organs. (A) Bacterial loads in the placenta of phage PIZ SAE-01E2-treated or S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842-infected mice. (B) Bacterial loads in the uterus of phage PIZ SAE-01E2-treated or S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842-infected mice. The black line represents the dynamic changes in the bacterial loads in the placenta of bacterium-infected mice; the green line represents dynamic changes in the bacterial loads in the placenta of mice that were treated with phage PIZ SAE-01E2; the red line represents the dynamic changes in the bacterial loads in the placenta of mice that were pretreated with phage PIZ SAE-01E2. All experiments were repeated three times. The values represent the means and SD (n = 3). The values on the x axis are times (in hours).

FIG 6.

Inflammatory cytokine expression in the placenta. The levels of the inflammatory cytokines IFN-γ, TNF-α, and IL-10 and the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 in the placenta were determined at 12 h, 24 h, and 48 h after bacterial infection. The values represent the means and SD (n = 3). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

S. Abortusequi causes abortion in mares and has been reported in most countries (3). Usually, the abortion of other Equus Linnaeus animals, such as donkeys, has not attracted people’s attention. Existing evidence shows that S. Abortusequi is associated with the abortion of donkeys in China (7). In this study, some S. Abortusequi strains were isolated from samples from aborted donkeys on four donkey farms (Shandong, China), which indicated that in China the incidence of abortions in donkeys caused by S. Abortusequi is increasing. Although good sanitation and appropriate breeding practices would minimize the risk of infection, there is an urgent need for novel therapeutic agents directed against this infection. Thus, the preventive and protective effects of phage therapy on a murine abortion model caused by S. Abortusequi were investigated in the present study.

A newly isolated phage, PIZ SAE-01E2, which infects and lyses S. Abortusequi, showed good resistance to high temperatures as well as a strong acid-base tolerance. These temperature and pH tolerances are beneficial for the storage and utility of phage PIZ SAE-01E2. Additionally, phage PIZ SAE-01E2 exhibited a broad host spectrum against the pathogenic O:4 and O:9 serogroups of Salmonella. The typical representatives of serogroups O:4 and O:9 are Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Typhimurium and Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Enteritidis, respectively (20). It has been reported that 99% of waterborne and foodborne infections in humans and animals are associated with this serovar (20). Furthermore, no virulence-related factors, antibiotic resistance genes, or lysogeny-related genes were identified in the genome of PIZ SAE-01E2. All of these characteristics indicate that phage PIZ SAE-01E2 has potential for use as phage therapy (21). Therefore, the therapeutic potential of PIZ SAE-01E2 was further explored in vitro and in vivo.

The in vitro experiments suggested that phage PIZ SAE-01E2 could significantly decrease the numbers of S. Abortusequi bacteria. However, when the inflection point weas reached, the numbers of S. Abortusequi bacteria began to increase gradually. This indicated that the sensitive bacteria, which account for a large proportion of bacteria in the initial stage, had been killed by phage PIZ SAE-01E2, and the phage-resistant cells started to grow rapidly after that time (22). It looks likely that, at a high MOI, phage PIZ SAE-01E2 can kill sensitive bacteria in a shorter amount of time, and then the resistant mutants become the mainstream bacteria and rapidly proliferate. Our results are consistent with those of other studies (2, 21). Additionally, a literature review found that phage resistance is more prone to be generated when a single phage is used than when a phage cocktail is used (23). Based on this, we are planning to study the therapeutic effects of phage cocktails against S. Abortusequi infection.

This study established that S. Abortusequi caused abortion in mice. The mice were found to be susceptible to a low dose (2 × 103 CFU/mouse) of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 in a later period of pregnancy (gestational day 14.5) but not in the early or midperiod of pregnancy, and all mice aborted within 48 h of bacterial challenge. The dose of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 (2 × 103 CFU/mouse) causing abortion in mice was close to the dose of S. Enteritidis (3 × 103 to 4 × 103 CFU/mouse) causing abortion in mice (24) but lower than that (104 CFU/rodent) of S. Abortusequi causing abortion in guinea pigs (11).

Before the phage PIZ SAE-01E2 was used to treat infected mice, the safety of PIZ SAE-01E2 for healthy mice was also tested. The safety study indicated that a single dose of 109 PFU/mouse of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 had no side effects on the health of pregnant mice or on the growth of the fetuses. More importantly, phage PIZ SAE-01E2 (108 PFU/mouse) provided 100% protection (10/10) against S. Abortusequi infection no matter whether the phage was injected before or after the bacterial challenge. Usually, bacteria cannot be completely eliminated by phages because of the development of phage-resistant mutants (25). Despite providing 100% protection, S. Abortusequi bacteria could also be detected in the placenta and uterus of infected mice even 96 h after phage administration. However, these residual bacteria did not cause abortion or other obvious damage to the mice.

When animals become pregnant, the Th1/Th2 immune system is altered to favor the expression of Th2 cytokines (26), benefiting fetal survival, but pregnant animals have been shown to be more vulnerable to Th1 immunity-dependent diseases, such as salmonellosis (27). In the placenta, the levels of cytokines, including IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-17, and IL-10, were increased remarkably after 24 h of S. Abortusequi infection compared to those in healthy pregnant mice. Phage administration resulted in a decrease in cytokine levels to normal.

The results of these assays demonstrate that phage PIZ SAE-01E2 is able to effectively reduce the bacterial loads and block abortions induced by S. Abortusequi in mice. Thus, PIZ SAE-01E2 exhibits great therapeutic potential for controlling abortion caused by S. Abortusequi in donkeys.

Conclusion.

In this study, the preventive and therapeutic effects of phage on a murine model of abortion caused by S. Abortusequi were investigated. A new phage, PIZ SAE-01E2, infecting S. Abortusequi was isolated and displayed efficient bactericidal activity against Salmonella serogroups O:4 and O:9. In in vivo experiments, administration of 108 PFU/mouse of PIZ SAE-01E2 at 1 h before or after S. Abortusequi challenge provided 100% protection to all pregnant mice. In addition, the bacterial loads in the placenta and uterus and the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the placenta and serum of the mice were dramatically reduced (P < 0.05) by the administration of phage PIZ SAE-01E2. All of these results indicate that PIZ SAE-01E2 shows great potential for use in therapeutic applications against abortive infection caused by S. Abortusequi.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

All animal experiments performed in this study strictly followed the national guidelines for experimental animal welfare (Ministry of Science and Technology of China, 2006) and were approved by the Animal Welfare and Research Ethics Committee at Jilin University, Changchun, China.

Animals.

Ten-week-old ICR female mice and 11-week-old ICR male mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of Jilin University, Changchun, China. All of them were allowed a week to adapt to their new surroundings, and then the female and male mice were mated individually. The day that a vaginal plug was observed was regarded as day 0.5 of pregnancy.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The Salmonella strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Most of them were isolated from abortive donkeys from different donkey farms (Shandong, China). All isolated strains were identified by 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing (forward primer, 5′-GTGGCGGACGGGTGAGTAA-3′; reverse primer, 3′-GTGTGACCTTGACTTCGTGCC-5′) and serogrouped with Salmonella antiserum (Ningbo Tianrun Biological Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Zhejiang, China). The Salmonella strains were cultured in lysogeny broth (LB) medium (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) or on Salmonella-Shigella (SS) selective agar plates (Oxoid, United Kingdom). Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae strains were cultured in LB. Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium were cultured in brain heart infusion (BHI) broth (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA). All bacterial strains were stored in liquid medium containing 30% glycerol at −20°C and −80°C.

Phage isolation and characteristics.

Sewage samples were collected from the Changchun, Jilin Province, China, sewer system. Phages were detected by spot assays and purified using a double-layer agar plate method as described previously (28). Briefly, 1 ml of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 was added into 100 ml LB liquid medium prepared with the filtered sewage samples. After incubation at 37°C with shaking at 165 rpm for 12 h, the mixture was centrifuged at 10,000 × g for 10 min and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.22-μm-pore-size filter (Millex-GP filter unit, lot R6MA05262; Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA). For detection of the phage in the filtrate, the spot assay was conducted on lawns of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842. The lawns were prepared by spreading 100 μl of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 on 1.5% LB agar plates, and the filtrate was dropped on the lawns; then, the plates were incubated at 37°C for 12 h. For purifying the phage, 100 μl of filtrate was mixed with 100 μl of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842, and the mixture was added into 0.75% LB top agar and mixed, and then the mixture was poured onto 1.5% LB agar plates. The double-layer agar plate was incubated at 37°C for 12 h. A single plaque was picked for further purification with double-layer testing three times. Finally, the phages were amplified in LB liquid medium and stored at 4°C and −80°C in glycerol (3:1 [vol/vol]). The host spectrum of the phage was also determined by the double-layer agar plate method (28).

The phage morphology was examined by previously described methods (28). Briefly, a phage sample was dropped onto a grid surface, allowed to be absorbed for 15 min, and then negatively stained with 2% phosphotungstic acid (PTA; 2% [wt/vol]). The phage morphology was observed using an 80-kV transmission electron microscope (TEM; JEOL model JEM-1200EXII; Japan Electronics and Optics Laboratory, Tokyo, Japan).

The thermal stability and pH sensitivity of the phage were determined as previously described, with some modifications (28). Briefly, 1 ml of the 2 × 108-PFU/ml purified phage was mixed with 1 ml SM buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1 M NaCl, 8 mM MgSO4, 0.01% [wt/vol] gelatin; Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA) in a 2-ml centrifuge tube and then incubated in a heating block at different temperatures (4°C, 10°C, 20°C, 30°C, 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C, and 80°C), and samples were collected at 40 min and 80 min. Phage titers against S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 were determined by the double-layer agar method. Additionally, 1 ml of the 1.65 × 108-PFU/ml purified phage was added into SM buffer, which had been adjusted to different pH values (pH 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12), and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Then, the samples were collected and the phage titers against S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 were determined by the double-layer agar plate method.

The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was defined as the ratio of the number of phages to the number of host bacteria (29). Briefly, the ATCC 9842 strain was cultured, adjusted to 108 CFU/ml (optical density at 600 nm [OD600] = 0.6), and mixed with phages at different MOIs (0.000001, 0.00001, 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 1, and 10). The mixture was cultivated for 8 h at 37°C with shaking at 165 rpm, and then the phage titers against S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 were determined by the double-layer agar method.

A one-step growth curve of the phage was tested as previously described, with some modifications (28). First, bacteria and phage were mixed at an MOI of 0.1 for 5 min. The mixture was added to 10 ml of LB liquid medium and incubated at 37°C with shaking at 165 rpm. Then, 400 μl of the mixed culture was collected every 5 min for the first 20 min and at 10-min intervals for the next 50 min. Two hundred microliters of the mixed culture sample was then treated with chloroform. The phage titers of the samples treated with or without chloroform were determined.

Sequencing and bioinformatics analysis of the phage genome.

The phage genome was extracted with a viral genome extraction kit (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., Norcross, GA, USA). Whole-genome sequencing of the phage was performed by the Wuhan Genewiz Biotechnology Co. using an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencing platform. The SPAdes program was used to assemble the raw data, and rapid annotations using subsystems technology (RAST) was employed to predict the putative potential open reading frames (ORFs). The potential tRNAs were detected by an online tRNA scanner service (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE). The possible functions of the ORFs were predicted by protein BLAST analysis with already known sequences in the NCBI database and illuminated by use of the CLC Genomics Workbench (version 8.1) program (CLC Bio-Qiagen, Aarhus, Denmark). Phylogenetic analysis was performed using the MEGA (version 7.0.26) program, based on the amino acid sequences of the terminase large subunit.

Inhibitory effect of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 on S. Abortusequi in vitro.

The inhibitory effect of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 on S. Abortusequi in vitro was determined as previously described, with some modifications (21). S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 bacteria were cultured and adjusted to 108 CFU/ml (OD600 = 0.6) in 5 ml LB liquid medium. Phage PIZ SAE-01E2 was added into the bacterial solutions at an MOI of 0.0001, 0.001, 0.01, 0.1, or 1. The mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 8 h with shaking at 165 rpm. The bacterial growth in the culture in the absence of phage was detected as the negative control. A total of 100 μl of culture was used to count colonies at intervals of 1 h.

Establishment of a murine abortion model.

ICR mice were used to establish the abortion model, as previously described (11, 30). Pregnant mice on different gestational days (GD; 3.5, 4.5, 6.5, 9.5, and 14.5) were used for the challenge experiments. There were three groups of pregnant mice on each GD, and each group contained 5 mice. Different doses of ATCC 9842, including 2 × 103 CFU/mouse, 2 × 104 CFU/mouse, and 2 × 105 CFU/mouse, were injected intraperitoneally into the three groups of mice, respectively. All challenged mice were monitored continuously, and the blood of the abortive mice was collected for determination of bacterial counts. Then, the abortive mice were euthanized by intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (Fatal Plus; 100 mg/kg of body weight). The placenta, uterus, fetus, and spleen of the abortive mice were removed, weighed, and suspended in filter-sterilized PBS and then were homogenized with sterile mortars and motor-driven Teflon pestles (JinTai, Changchun, China). The organ slurry was diluted in 1.0 ml PBS buffer (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 50 mM Na2HPO4, 10 mM KH2PO4, pH 7.4). The bacterial burden of the organs was calculated by serially diluting the suspension of the homogenized organs in PBS and plating onto Salmonella-Shigella (SS) agar, followed by incubation at 37°C for 24 h. All suspected strains were further confirmed to be S. Abortusequi by 16S rRNA gene amplification and sequencing.

Safety test of phage PIZ SAE-01E2.

Twenty mice at GD 14.5 were divided into two groups (each group contained 10 mice), and each group was intraperitoneally administered 109 PFU/mouse of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 or PBS buffer. All mice were fed under the same conditions and observed until 2 days after giving birth. The health status of the female mice was evaluated as previously described (31). Briefly, the health score was divided into six grades (0, dead; 1, near death; 2, exudative accumulation around partially closed eyes; 3, lethargy and hunched back; 4, decreased physical activity and ruffled fur; 5, normal health, condition unremarkable). Additionally, the fetal growth restriction (FGR) of their offspring was evaluated as previously described (32). Briefly, at day 18.5 or 21.5, fetuses whose weight was less than the normal fetal weight by 2 standard deviations (SD) (1.231 ± 0.091 and 1.543 ± 0.061 on days 18.5 and 21.5, respectively) were defined as having FGR. All of the data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Protective efficacy of phage in murine abortion model.

On GD 14.5, the mice were randomly divided into eight groups (groups A to H), with each group containing 10 mice. Mice in groups A to C were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of 0.2 ml phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at 5 × 106 PFU/ml, 5 × 107 PFU/ml, or 5 × 108 PFU/ml per mouse, respectively, at 1 h before S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 challenge. Mice in groups D to F were injected intraperitoneally with a single dose of 0.2 ml phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at 106 PFU/mouse, 107 PFU/mouse, or 108 PFU/mouse, respectively, at 1 h after S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 challenge. Mice in groups G and H were injected with a single dose of 0.2 ml PBS intraperitoneally at 1 h before or after S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 challenge, respectively. Mice in all groups were monitored daily until 2 days after giving birth to calculate the rate of protection provided by phage administration. The health scores of the female mice and the FGR of the fetuses were observed.

The bacterial loads in the uterus and placenta of pregnant mice were determined. On GD 14.5, the mice were randomly divided into three groups (groups A to C), and each group contained 40 mice. Pregnant mice in group A (the phage-pretreated group) were injected intraperitoneally with 0.2 ml (5 × 108 PFU/ml) of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at 108 PFU/mouse at 1 h before challenge; pregnant mice in group B (the phage-treated group) were injected intraperitoneally with 0.2 ml (5 × 108 PFU/ml) of phage PIZ SAE-01E2 at 108 PFU/mouse at 1 h after challenge; pregnant mice in group C (the bacterium-infected group) were only challenged by S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 without any treatment. Three mice from each group were randomly selected and euthanized by intravenous injection of pentobarbital sodium (Fatal Plus; 100 mg/kg) at 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h after bacterial challenge. The uterus and placenta of the mice were removed under sterile conditions and homogenized in 1.0 ml PBS buffer. The limit of detection (LOD) was 10 CFU/g or CFU/ml. A total of 100 μl of the homogenates was serially diluted with PBS, plated on SS agar, and incubated at 37°C for 24 h to count the number of S. Abortusequi ATCC 9842 bacteria. Additionally, the blood and placenta of the mice from each group were collected at 12, 24, and 48 h after phage administration for detection of the levels of inflammatory cytokines (IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-10, and IL-17). Healthy pregnant mice without any treatment were used as controls. The remaining placenta homogenates were centrifuged at 4°C for 10 min (10,000 × g), and the supernatants were collected. The collected blood was placed at 37°C for 30 min and then placed at 4°C overnight, and the serum was collected by low-speed centrifugation (3,000 × g for 3 min). Cytokine levels in the serum and the supernatant of the homogenized placental tissue were determined using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA) (11).

Data analysis.

Statistical analysis of the experimental data was performed using SPSS (version 13.0) software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), and all data were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Data availability.

The accession number in the GenBank database for phage PIZ SAE-01E2 is MN336266. The accession number for the raw fastq files for phage PIZ SAE-01E2 in the Sequence Read Archive database is SRR9695851.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was financially supported through grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. U19A2038 and 31872505), the Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (Changchun, China; grant no. 20200201120JC), the Jilin Province Science Foundation for Youths (Changchun, China; grant no. 20190103106JH), the Achievement Transformation Project of the First Hospital of Jilin University (grant no. JDYYZH-1902025), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities.

We declare no competing financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

REFERENCES

- 1.Uzzau S, Brown DJ, Wallis T, Rubino S, Leori G, Bernard S, Casadesús J, Platt DJ, Olsen JE. 2000. Host adapted serotypes of Salmonella enterica. Epidemiol Infect 125:229–255. doi: 10.1017/s0950268899004379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duerkop BA, Huo W, Bhardwaj P, Palmer KL, Hooper LV. 2016. Molecular basis for lytic bacteriophage resistance in enterococci. mBio 7:e01304-16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01304-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grandolfo E, Parisi A, Ricci A, Lorusso E, de Siena R, Trotta A, Buonavogli D, Martella V, Corrente M. 2018. High mortality in foals associated with Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica Abortusequi infection in Italy. J Vet Diagn Invest 30:483–485. doi: 10.1177/1040638717753965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niwa H, Hobo S, Kinoshita Y, Muranaka M, Ochi A, Ueno T, Oku K, Hariu K, Katayama Y. 2016. Aneurysm of the cranial mesenteric artery as a site of carriage of Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar Abortusequi in the horse. J Vet Diagn Invest 28:440–444. doi: 10.1177/1040638716649640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bryant NA, Wilkie GS, Russell CA, Compston L, Grafham D, Clissold L, McLay K, Medcalf L, Newton R, Davison AJ, Elton DM. 2018. Genetic diversity of equine herpesvirus 1 isolated from neurological, abortigenic and respiratory disease outbreaks. Transbound Emerg Dis 65:817–832. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madić J, Hajsig D, Sostari B, Ćurić S, Seol B, Naglić T, Cvetnić Z. 1997. An outbreak of abortion in mares associated with Salmonella Abortusequi infection. Equine Vet J 29:230–233. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1997.tb01674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang H, Liu KJ, Sun YH, Cui LY, Meng X, Jiang GM, Zhao FW, Li JJ. 2019. Abortion in donkeys associated with Salmonella abortus equi infection. Equine Vet J 51:756–759. doi: 10.1111/evj.13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Singh BR, Chandra M, Hansda D, Alam J, Babu N, Siddiqui MZ, Agrawal RK, Sharma G. 2013. Evaluation of vaccine candidate potential of deltaaroA, deltahtrA and deltaaroAdeltahtrA mutants of Salmonella enterica subspecies enterica serovar Abortusequi in guinea pigs. Indian J Exp Biol 51:280–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kwon YM, Cox MM, Calhoun LN. 2007. Salmonella-based vaccines for infectious diseases. Expert Rev Vaccines 6:147–152. doi: 10.1586/14760584.6.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singh BR, Sharma VD. 1998. Purification and characterization of phospholipase C of Salmonella gallinarum. Indian J Exp Biol 36:1245–1252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abhishek KB, Anjay Mishra AK, Prakash C, Priyadarshini A, Rawat M. 2018. Immunization with Salmonella Abortusequi phage lysate protects guinea pig against the virulent challenge of SAE-742. Biologicals 56:24–28. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Singh BR, Alam J, Hansda D, Verma JC, Singh VP, Yadav MP. 2002. Evaluation of guinea pig model for experimental Salmonella serovar Abortusequi infection in reference to infertility. Indian J Exp Biol 40:296–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones PW, Dougan G, Hayward C, Mackensie N, Collins P, Chatfield SN. 1991. Oral vaccination of calves against experimental Salmonellosis using a double aro mutant of Salmonella typhimurium. Vaccine 9:29–34. doi: 10.1016/0264-410x(91)90313-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cisek AA, Dąbrowska I, Gregorczyk KP, Wyżewski Z. 2017. Phage therapy in bacterial infections treatment: one hundred years after the discovery of bacteriophages. Curr Microbiol 74:277–283. doi: 10.1007/s00284-016-1166-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bao H, Zhou Y, Shahin K, Zhang H, Cao F, Pang M, Zhang X, Zhu S, Olaniran A, Schmidt S, Wang R. 2020. The complete genome of lytic Salmonella phage vB_SenM-PA13076 and therapeutic potency in the treatment of lethal Salmonella Enteritidis infections in mice. Microbiol Res 237:126471. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2020.126471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seo BJ, Song ET, Lee K, Kim JW, Jeong CG, Moon SH, Son JS, Kang SH, Cho HS, Jung BY, Kim WI. 2018. Evaluation of the broad-spectrum lytic capability of bacteriophage cocktails against various Salmonella serovars and their effects on weaned pigs infected with Salmonella Typhimurium. J Vet Med Sci 80:851–860. doi: 10.1292/jvms.17-0501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Callaway TR, Edringto TS, Brabban A, Kutter B, Karriker L, Stahl C, Wagstrom E, Anderson R, Poole TL, Genovese K, Krueger N, Harvey R, Nisbet DJ. 2011. Evaluation of phage treatment as a strategy to reduce Salmonella populations in growing swine. Foodborne Pathog Dis 8:261–266. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2010.0671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prajapati A, Ramchandran D, Verma H, Abbas M, Rawat M. 2014. Therapeutic efficacy of Brucella phage against Brucella abortus in mice model. Vet World 7:34–37. doi: 10.14202/vetworld.2014.34-37. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anany H, Switt AI, De Lappe N, Ackermann HW, Reynolds DM, Kropinski AM, Wiedmann M, Griffiths MW, Tremblay D, Moineau S, Nash JH, Turner D. 2015. A proposed new bacteriophage subfamily: “Jerseyvirinae.” Arch Virol 160:1021–1033. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2344-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li P, Liu Q, Luo H, Liang K, Yi J, Luo Y, Hu Y, Han Y, Kong Q. 2017. O-serotype conversion in Salmonella Typhimurium induces protective immune responses against invasive non-typhoidal Salmonella infections. Front Immunol 8:1647. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng M, Liang J, Zhang Y, Hu L, Gon P, Cai R, Zhan L, Zhang H, Ge J, Ji Y, Guo Z, Feng X, Sun C, Yang Y, Lei L, Han W, Gu J. 2017. The bacteriophage EF-P29 efficiently protects against lethal vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecalis and alleviates gut microbiota imbalance in a murine bacteremia model. Front Microbiol 8:837. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li Z, Li X, Zhan J, Wang X, Wang L, Cao Z, Xu Y. 2016. Use of phages to control Vibrio splendidus infection in the juvenile sea cucumber Apostichopus japonicus. Fish Shellfish Immunol 54:302–311. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breyne K, Honaker RW, Hobbs Z, Richter M, Żaczek M, Spangler T, Steenbrugge J, Lu R, Kinkhabwala A, Marchon B, Meyer E, Mokres L. 2017. Efficacy and safety of a bovine-associated Staphylococcus aureus phage cocktail in a murine model of mastitis. Front Microbiol 8:2348. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noto Llana M, Sarnacki SH, Aya Castañeda M, Pustovrh MC, Gartner AS, Buzzol FR, Cerquetti MC, Giacomodonato MN. 2014. Salmonella enterica serovar Enteritidis enterocolitis during late stages of gestation induces an adverse pregnancy outcome in the murine model. PLoS One 9:e111282. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0111282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Drulis KZ, Majkowska SG, Maciejewska B, Delattre AS, Lavigne R. 2012. Learning from bacteriophages—advantages and limitations of phage and phage-encoded protein applications. Curr Protein Pept Sci 13:699–722. doi: 10.2174/138920312804871193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Negi VD, Nagarajan AG, Chakravortty D. 2010. A safe vaccine (DV-STM-07) against Salmonella infection prevents abortion and confers protective immunity to the pregnant and new born mice. PLoS One 5:e9139. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Awadalla SG, Mercer LJ, Brown LG. 1985. Pregnancy complicated by intraamniotic infection by Salmonella typhi. Obstet Gynecol 65:30S–31S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen M, Xu J, Yao H, Lu C, Zhang W. 2016. Isolation, genome sequencing and functional analysis of two T7-like coliphages of avian pathogenic Escherichia coli. Gene 582:47–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Czajkowski R, Ozymko Z, de Jager V, Siwinska J, Smolarska A, Ossowicki A, Narajczyk M, Lojkowska E. 2015. Genomic, proteomic and morphological characterization of two novel broad host lytic bacteriophages PhiPD10.3 and PhiPD23.1 infecting pectinolytic Pectobacterium spp. and Dickeya spp. PLoS One 10:e0119812. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0119812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim S, Lee DS, Watanabe K, Furuoka H, Suzuki H, Watarai M. 2005. Interferon-gamma promotes abortion due to Brucella infection in pregnant mice. BMC Microbiol 5:22. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-5-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen Y, Guo G, Sun E, Song J, Yang L, Zhu L, Liang W, Hua L, Peng Z, Tang X, Chen H, Wu B. 2019. Isolation of a T7-like lytic Pasteurella bacteriophage vB_PmuP_PHB01 and its potential use in therapy against Pasteurella multocida infections. Viruses 11:86. doi: 10.3390/v11010086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin D, Smith MA, Elter J, Champagne C, Downey CL, Beck J, Offenbacher S. 2003. Porphyromonas gingivalis infection in pregnant mice is associated with placental dissemination, an increase in the placental Th1/Th2 cytokine ratio, and fetal growth restriction. Infect Immun 71:5163–5168. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.9.5163-5168.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Xi H, Su J, Cheng M, Wang G, He D, Cai R, Wang Z, Sun YGC, Feng X, Lei L, ur Rahman S, Jianbao D, Han W, Gu J. 2020. Characterization and genome analysis of a novel Escherichia coli bacteriophage vB_EcoS_W011D. Pak Vet J 40:157–162. doi: 10.29261/pakvetj/2019.114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Li Q, Hu Y, Wu Y, Wang X, Xie X, Tao M, Yin J, Lin Z, Jiao Y, Xu L, Jiao X. 2015. Complete genome sequence of Salmonella enterica serovar Pullorum multidrug resistance strain S06004 from China. J Microbiol Biotechnol 25:606–611. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1406.06031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hu GQ, Song PX, Chen W, Qi S, Yu SX, Du CT, Deng XM, Ouyang HS, Yang YJ. 2017. Cirtical [sic] role for Salmonella effector SopB in regulating inflammasome activation. Mol Immunol 90:280–286. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2017.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cai R, Wu M, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Cheng M, Guo Z, Ji Y, Xi H, Wang X, Xue Y, Sun C, Feng X, Lei L, Tong Y, Liu X, Han W, Gu J. 2018. A smooth-type, phage-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae mutant strain reveals that OmpC is indispensable for infection by phage GH-K3. Appl Environ Microbiol 84:e01585-18. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01585-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gu J, Xu W, Lei L, Huang J, Feng X, Sun C, Du C, Zuo J, Li Y, Du T, Li L, Han W. 2011. LysGH15, a novel bacteriophage lysin, protects a murine bacteremia model efficiently against lethal methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. J Clin Microbiol 49:111–117. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01144-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The accession number in the GenBank database for phage PIZ SAE-01E2 is MN336266. The accession number for the raw fastq files for phage PIZ SAE-01E2 in the Sequence Read Archive database is SRR9695851.