Abstract

Biomedical HIV prevention trials increasingly include evidence-based adherence counseling to encourage product use. To retain effectiveness, interventions must contain key components. Monitoring counseling fidelity ensures inclusion of components but is challenging in multinational contexts with different languages and scarce local supervision. The MTN-025/HOPE Study, a Phase 3b open-label trial to assess continued safety of and adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention, was the largest such trial to integrate fidelity monitoring using audio recordings of counseling sessions. We describe the monitoring process, along with counselor and participants’ perceptions of it, which were collected via quantitative online survey (counselors only N=42) and in-depth interviews with a subset of counselors (N=22) and participants (N=10). Sessions were conducted in five languages across 14 study sites in four countries. In total, 1,238 sessions (23% of submitted sessions) were randomly selected and rated. Assessment of interrater reliability was essential to address drift in ratings. Counselors were apprehensive about being monitored, but appreciated clear guidance and found ratings very helpful (mean = 6.64 out of 7). Some participants perceived sessions as time-consuming; others found monitoring improved counseling quality. Fidelity monitoring of counseling sessions in multisite biomedical HIV studies is feasible and supportive for counselors.

Keywords: counseling, fidelity monitoring, Africa, HIV prevention

Introduction

Biomedical HIV prevention trials are increasingly including evidence-based adherence counseling to encourage product use. To retain effectiveness, delivery of evidence-based counseling interventions must include their key components (McHugh & Barlow, 2010). However, counselors often encounter challenges when delivering new counseling interventions, which can result in the omission of key components. For example, studies on learning Motivational Interviewing (MI), a frequently used evidence-based approach to facilitate behavior change, have found that learning to practice MI with fidelity is not easy, especially among providers with limited formal counseling training (Söderlund, Nilsen, & Kristensson, 2008; Moyers, et al., 2008). Furthermore, skills acquired during initial training frequently dissipate over subsequent months in the absence of consistent coaching and feedback (Moyers, Manuel, Wilson, & Hendrickson, 2008; Konkle-Parker, Erien, & Dubbert, 2010). As such, methods for monitoring fidelity to such counseling interventions are essential.

One useful method to monitor fidelity is to audio-record counseling sessions. Audio recordings assess fidelity more accurately than counselor self-report (Hogue et al., 2015; Martino et al., 2009; Carroll, Nich & Rounsaville, 1998; Hurlburt et al., 2010; Wain et al., 2015), are less invasive than in-person observation, and can be used routinely without adding to counselor workload. Although audio recordings are used often to monitor fidelity in behavioral interventions, only one other biomedical HIV prevention trial has incorporated them to date. The findings from this study underscored the need for fidelity monitoring, as half of the counselors met fidelity criteria for fewer than half of their sessions (Balán et al., 2014).

Monitoring the fidelity of counseling interventions implemented in multinational contexts faces additional challenges: sessions are conducted in a variety of languages and, often, scarce local expertise is available to provide ongoing coaching and supervision. Additionally, there must be sufficient interrater reliability across fidelity monitors (Forsberg, Källmén, Hermansson, Berman, & Helgason, 2007) to ensure that counselors receive standardized feedback and support across sites (Baer et al., 2007). Finally, to keep counselors engaged, feedback needs to be provided in a supportive, client-centered manner so that it is not perceived as punitive and reinforces the counseling style (Patterson, 1983; Martino et al. 2006).

This article describes the COACH (Counseling to Optimize Adherence, Choice, and Honest reporting) Program, developed to support the training and supervision of counselors in the MTN-025/HOPE Study, an open-label extension trial to assess continued safety and adherence to the dapivirine vaginal ring for HIV prevention at fourteen sites in four African countries (Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, Zimbabwe). The HOPE Study was the largest biomedical HIV prevention trial to integrate fidelity monitoring using audio recordings of adherence counseling sessions. Given the aforementioned challenges to implementing fidelity monitoring in such a trial, this paper describes how project leaders assembled a multi-lingual rating team for the COACH Program, assessed interrater reliability, provided client-centered feedback to counselors, and how counselors and participants perceived the fidelity monitoring process. These findings can inform future fidelity monitoring interventions in multi-site, international trials using behavioral interventions.

Methods

The MTN-025/HOPE Study

The MTN-025/HOPE Study was a Phase 3B trial to characterize safety and adherence associated with open-label use of the dapivirine vaginal matrix ring among women. The ring was designed to be inserted monthly and to stay in place for 30 days to provide HIV protection for women. Participants in the HOPE study were offered the ring as an HIV prevention method, and those who chose to use the ring were asked to return used rings to the clinic to be tested for residual drug levels, an objective measure of adherence. Participation lasted 12 months, during which participants could opt at any time to start or stop using the ring. Those who chose not to use the ring were assisted with developing an alternate HIV prevention plan.

The Options Counseling Intervention

Options Counseling was an MI-based intervention developed to support adherence to the ring in the HOPE Study. As women in this trial were not required to use the ring, the Options Counseling intervention aimed to support them in successfully using the HIV prevention method(s) of their choice. The intervention emphasized global MI concepts, such as: (A) collaboration between the counselor and participant in developing an HIV prevention plan; (B) empathy (i.e., demonstrating interest in the participant’s perspective); (C) respect for participants’ choices; and (D) evocation (i.e., demonstrating curiosity about the participant’s interest in preventing HIV). Counselors were taught strategies for evoking participants’ experiences and challenges using the ring or other HIV prevention methods, incorporating specific MI microskills such as open-ended questions, reflections, and affirmations. Sessions were designed to last 20–30 minutes. Given that existing counseling and nursing staff were designated by each study site’s leadership to be counselors for this study, the sessions were designed to be delivered by counselors with varying counseling training levels, including some with no formal training. A detailed manual, which provided a sequence of tasks for each type of session (enrollment, follow-up, end visit), and a tabletop flip chart in local languages that followed the task sequence and facilitated a conversational tone during sessions, were designed to guide counselors.

Study counselors attended a two-day, in-person training that consisted of didactic teaching on delivering the intervention and experiential exercises to improve counseling skills and foster client-centeredness. Before interacting with study participants, counselors were required to demonstrate fidelity in three mock counseling sessions, conducted in English with a peer.

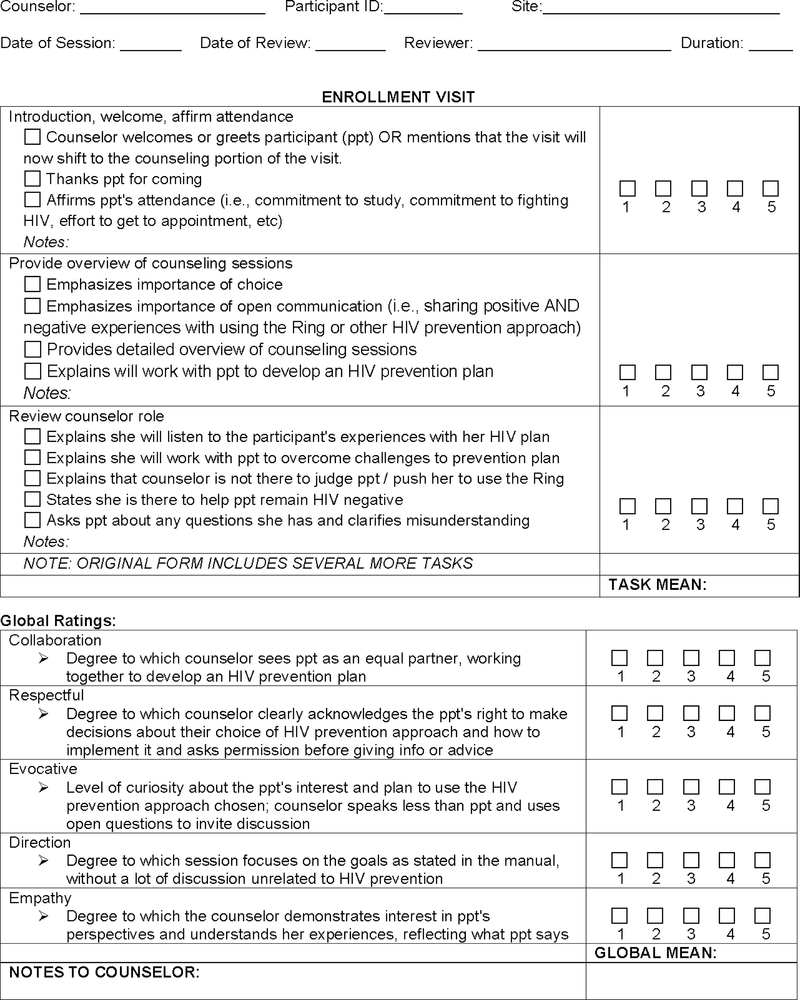

Options Counseling sessions were audio-recorded and uploaded to a secure file-transfer-protocol (FTP) site for review, pending consent of study participants. Out of 9,926 study visits in which a counseling session was expected to occur, 5,366 sessions (54%) were recorded and uploaded. A randomly selected sub-sample of 1,238 (23% of recorded sessions) were rated for fidelity to session tasks and client-centered components by a multilingual team of raters located in New York. Sessions were rated in their entirety for fidelity to tasks and client-centeredness. Among sixty study counselors at fourteen study sites who completed at least 10 sessions, the median number of sessions uploaded per counselor was 43. The median proportion rated was 30% (range = 12% - 100%, depending on number of sessions uploaded). Study rating forms presented each session task as outlined in the manual, with tick boxes indicating key components and ratings from 1 (task skipped) to 5 (task completed at a level equivalent to or better than the manual) for each; ratings for the client-centered components also ranged from 1 to 5, with space for written comments (See Figure 1 – Sample Rating Form). Completed rating forms were sent to each counselor via email, and the lead investigator held monthly coaching calls with small groups of counselors to discuss areas where further guidance was needed and problem-solve challenges. A more detailed description of the process, feasibility, and outcomes of the counseling intervention has been previously published (Balán et al., 2020).

Figure 1.

Sample Rating Form

The COACH Rating Team

Training

The multilingual rating team included immigrants based in New York who spoke English and were native speakers of the study languages (Xhosa, Zulu, Luganda, Chichewa, and Shona). All raters underwent a two-day training, including an overview of client-centered counseling and a review of the HOPE Study counseling objectives. A fidelity ratings guide ensured that all raters followed similar standards when assigning ratings. It provided an overview and examples of each task completed at various levels, ranging from 1 to 5, and described how to rate the client-centered components. Raters became familiarized with the fidelity rating guide during the initial training, and the team periodically updated the guide throughout the study to improve clarity. Additionally, before rating sessions independently, the rating team conducted group fidelity ratings of two enrollment counseling sessions, stopping the recording after each task to discuss the ratings given provide justifications. Subsequently, each rater evaluated three enrollment sessions independently, which were then discussed as a group. Finally, once counselors started to conduct follow-up and end visit counseling sessions, the rating team underwent another training focused on new tasks for these sessions. Team members rated two follow-up sessions independently, then met to jointly discuss and compare ratings.

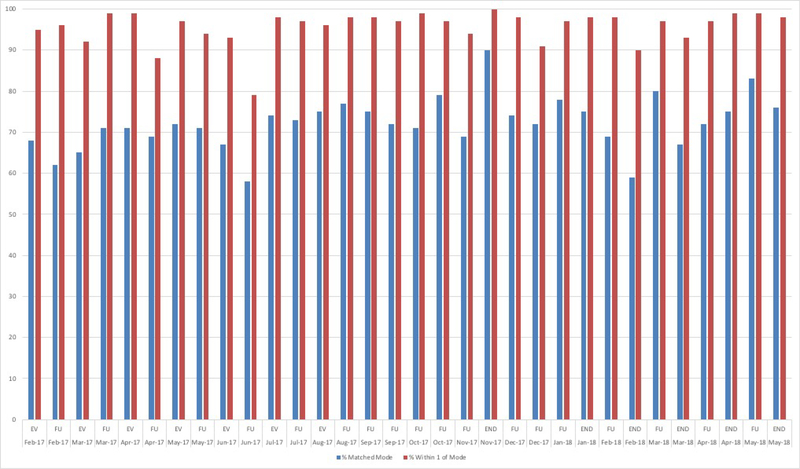

Interrater Reliability

To demonstrate inter-rater reliability (IRR), the goal was for all raters to match the mode for 80% of ratings, and to be within 1 of the group’s modal rating (along the 1-to-5 rating scale) for 100% of tasks and client-centered components. The objective for assessing IRR was to prevent drift and to re-calibrate the rating team, as needed. Given the different languages used in this study, all raters independently rated two sessions in English each month. Over time, ratings drifted apart, particularly for more open-ended tasks and for sessions that were particularly difficult to rate due to counselors completing tasks out of order. After rating the required IRR sessions, the team met as a group to discuss areas of disagreement and ensure continued reliability in ratings (See Figure 2 – IRR Over Time).

Figure 2.

Interrater Reliability Over Time (% of ratings matching and within 1 of the mode for each session rated as a team)

Creating a Client-Centered Team

Once raters were proficient at rating counseling sessions, the monthly IRR meetings focused on modifying communication styles via the rating forms. In short, the team strove to model client-centered concepts in the feedback given to counselors. Box 1 describes the steps taken to create a client-centered rating team, including familiarizing counselors and raters, raters’ participation in monthly coaching calls, rating the raters, comment workshops, and an in-person meeting between raters and counselors. The overall goal was to support the counselors and improve counseling quality by emphasizing teamwork between raters and counselors.

Box 1.

Creating a Client-Centered Team

|

1. Familiarizing raters with counselors | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To help the raters personalize their written interactions with counselors on the rating form and to reinforce the sense that their role was to provide useful feedback to the individual counselors at the study sites. | Photos of each site’s counseling team were placed n the raters’ office by their computers so that they could see them while rating their sessions. |

|

2. Familiarizing counselors with raters | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To minimize the sense of judging that comes from having one’s work rated by another person. | A team newsletter with photographs and a short bio of each rater was sent to the counselors, so that they could see that the raters were natives of their countries even if based in New York. |

|

3. Raters’ participation in coaching calls | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To emphasize that raters and counselors were working together to improve quality of counseling. | Whenever possible, raters participated in the monthly coaching calls with site counselors. |

|

4. Rating the raters | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To facilitate discussion of how brief, critical comments breed frustration rather than encourage growth, so as to encourage more client-centered feedback. | Raters received via email brief feedback about their ratings of a session for IRR, identifying areas where they did not match the mode. Ratersdiscussed how they felt upon reading the feedback and decided to include client-centered comments to the raters. They could support the counselors more effectively by affirming what they were doing well and making client-centered, motivational suggestions for how to improve. |

|

5. Comment workshops | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To support the counselors more effectively by affirming what they were doing well and making client-centered, motivational suggestions for how to improve. | Raters were given a list of comments with common errors and were tasked with rewriting the comments to improve their client-centeredness and sharing their suggestions with the team. |

|

6. In-person meeting | |

| Goal | Exercise |

| To create rapport between team members and allow counselors to inform raters of what types of feedback would be most useful. | Midway through the study, raters and counselors traveled to South Africa where they met in person and worked together for three days practicing counseling skills. There, the counselors were able to inform the raters of what would be most supportive for them to include in the rating forms. |

Collecting Feedback from Counselors

After completing the HOPE Study, all counselors who had conducted at least ten Options Counseling sessions (N=60) were invited to complete an online assessment to evaluate their experiences participating in the COACH Program. Each counselor was assigned a study ID based on study site; they used this ID to complete an online informed consent form and to indicate their interest in participating in a separate in-depth interview before being directed to the online survey. The survey was a brief, quantitative assessment that collected basic demographics and information on prior counseling training and experience. Additonally, counselors were asked to gauge how helpful the session ratings were for developing their counseling skills, on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1=not helpful at all and 7=extremely helpful. Counselors were then asked to retrospectively report how confident they felt during their first five sessions and last five sessions, on a scale of 1 to 7, where 1=not confident at all and 7=completely confident. Counselors were also asked how many sessions they conducted before they felt confident, with answer choices ranging from “less than 25 sessions” to “after more than 100 sessions” to “I never really felt confident conducting Options counseling sessions.” Finally, counselors were asked how likely they would be to use the counseling skills they learned for the HOPE study in their future work.

A maximum of two interested counselors per site were randomly selected to participate in in-depth interviews (IDIs) to gather more detailed feedback (N=22). The interview took place by phone in English with a trained interviewer who had not worked with the counselor during the HOPE Study. The interview guide explored reactions to the fidelity monitoring process, including session recordings and ratings.

Collecting Feedback from Participants

A subset of N=91 HOPE trial participants underwent either ≤ 3 serial IDIs or one single special case IDI on a range of topics about adherence and acceptability of the vaginal ring, during which N=10 spontaneously provided feedback on their experience with the recordings during Options counseling. Interviews took place in person with a trained interviewer at the clinic who was not involved in the study’s clinical or counseling components. Serial IDI’s took place around either month 1, month 3, or at their product use end visit. Special case IDI’s took place after the special case was identified.

Data Analysis

Quantitative data from the online assessment were cleaned and checked for accuracy. The final dataset was analyzed using descriptive statistics in SPSS (v25).

Audio-recordings of interviews with counselors were transcribed and checked for accuracy. The lead investigator and team developed a qualitative codebook based on the interview guide and study objectives. Two independent raters coded transcripts using NVivo (v11), meeting periodically to assess intercoder reliability and discuss and resolve all coding discrepancies. Coding reports for the following codes were summarized and analyzed by the study team to identify emerging themes: counselor’s reaction to recordings, participants’ reactions to recordings, counselor’s reaction to ratings, and counselor’s recommendations for ratings.

Interviews with HOPE trial participants were conducted in the local African language, audio-recorded, transcribed, translated into English, and underwent quality control reviews between the site staff and the qualitative data coordinating center (RTI International) for clarity. English transcripts were uploaded to Dedoose software for coding, which took place by a team of five coders. Intercoder reliability was determined using the Dedoose training center tool with nine ‘key’ codes (about the study objectives) for 10% of transcripts, with an average Kappa score of 0.7. Additionally, the coding team met weekly to resolve coding questions and discuss interesting findings. The lead author reviewed, summarized, and analyzed a coding report of excerpts labeled as ‘counseling’ for mentions of the session recordings.

Results

Online Survey

Forty-two out of the sixty counselors (70%) from all fourteen sites completed the online questionnaire. Most (93%) were female, and 95% had completed education beyond high school level. Fifty percent had professional training in medical/clinical fields and 43% in fields related to counseling, social work, or psychology. Five (12%) reported not having any professional training in counseling, while the rest had earned either a counseling degree or a certificate/diploma. Fifty percent reported that their primary role at their clinic was as a research nurse, while forty-five percent were hired as counselors. Only three (7%) reported never having conducted counseling before the HOPE study.

For helpfulness of session ratings, counselors gave a mean rating of 6.64, indicating that the session ratings were very helpful. For the level of confidence in the first five sessions, counselors gave a mean rating of 3.93, indicating moderate confidence, and for the last five sessions, counselors gave a mean rating of 6.45, indicating nearly complete confidence. A majority (n=37, 88%) responded that they felt confident after conducting fewer than 25 sessions. Ninety percent (n=38) reported they would be very likely to use the counseling skills they learned for the HOPE study in their future work. An additional ten percent reported being somewhat likely to use their client-centered counseling skills in the future.

In-depth Interviews

See Table 1 for illustrative quotes of qualitative themes.

Table 1.

Reactions to Session Recordings and Ratings

| Theme | Subtheme | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Session Recordings | Counselor Reactions |

Initially it was -- because it’s very scary and it’s intimidating, I would say, because when you’re not sure what you’re doing, it’s very hard to know that you are being recorded and somebody’s going to be listening to your mistakes. (Participant ID 53) |

|

When time goes on, you get to be comfortable and forget about the recorder and talk to the person in front of you. So, the minute you forget that you’re being recorded, you get to relax. (PTID 28) |

||

|

No, it was very nice to have the sessions recorded because it builds a record of you as the counselor working with your participant what you were talking about. Because with the record, you can also replay it and then you can hear yourself what you were saying to the participant. That equips you so that you could be able to pick up even your mistakes. That it’s also a learning curve for you not to repeat what we have done on that record. (PTID 25) |

||

|

For me, as a counselor, it benefited me a lot. I would review my work even with my peers. I would sit together and listen and comment each other, and also correct each other, which also I think made our team stronger. So, recording was good. (PTID 38) |

||

| I believe it also influenced the accuracy of the data. Because if someone knows that they’re being recorded, they become not friendly and comfortable to tell everything. (PTID 41) | ||

| How Counselors Presented Recordings to Participants |

Some of them, they didn’t want to be recorded because of time. They would say that “I’m going to work. I don’t want you to record it.” (PTID 25) |

|

|

Even the person that refused the previous month, the following month, they will agree as soon as we made them realize that, even if you disagree to have a recording, I’m still going to follow the same flip chart. So don’t think that you’re going to spend five minutes. We are still going to spend the time to discuss everything that you need to discuss in a session. (PTID 42) |

||

|

One thing that I appreciate is that, the team actually said…when you feel a participant is in a hurry and they won’t be able to finish right through the 20 minutes, there are some parts you can cut... if a participant wants to go early, we would try to make the session, even for five minutes, or eight minutes. (PTID 16) |

||

|

Even if it’s sitting between me and her, it’s far away in the desk, I will make sure that I pull it towards me, so that she is – make her understand, “Oh, she’s recording herself, not me.” Yeah, so I put it as far away from her, as close to me as possible. (PTID 53) |

||

|

The people that will be listening to it won’t be trying to evaluate you or something. But they are listening to what I am saying to you, how I’m conducting the session. They are doing that because they want to help me be the best counselor for you. So you will see a person smiling, because they will feel that I’m doing this for them –- that it’s best for them at the end. (PTID 42) |

||

| You have to explain to them that the people at the site, they won’t listen to the recording. It’s between you and the participants. They are not staff members. They won’t listen to your recordings. And that you are sending their recording to America, so no one in the clinic will know what you were talking about. So you have to reassure the participants about confidentiality. (PTID 04) | ||

| Participant Reactions |

I don’t like this recording thing… It takes a long time to get counselled… Maybe you speak soft or something. Sometimes you don’t feel like talking or you just want to listen. (Participant 687, Month 3 Visit) |

|

|

This [counseling] is now advanced with your recordings and the books [meaning flip charts] you now have which you open to read… it is now of high standard. (Participant 254, Month 3 Visit) |

||

| When we are not recorded, study staff being human at times they will be tired and they would have done it for a long time so they will be using short cuts [laughs]. But when there is recording we say it all, there is nothing that is left over. (Participant 892, Enrollment Visit) | ||

| Session Ratings |

I was like, these people, they want to judge us. (laughter) I thought that. I was feeling uneasy. And I remember, I could not open the first feedback I had. (PTID 43) |

|

|

I had problems to ask open-ended questions all the time. But with the comments, which were said in a very nice way, I found myself improving with the open-ended questions. (PTID 33) |

||

|

The raters were -- they would say, you have done this portion very well. And then when you look back and remembered it, oh, it means that if I’m doing my counseling and I’m touching on this and this and this, that’s doing it very well. Because you also like to be reassured. You also like to be shown where we have done well. (PTID 42) |

||

|

If we were just doing the sessions and not having the feedback, where would we know when we are not doing it right? (PTID 22) |

||

|

So, if I would have a three today for the way I would have handled a certain session, the next time I would find I have a four, and then next time I have a five -- this means I -- it made me work. It made me improve myself. It made me fix my mistakes. It made me have confidence in my work. (PTID 33) |

||

|

It was a big impact. Can I call it tremendous, it was a tremendous impact. Why? You know, like when you’re counseling, no one realizes that you’re doing something good, not until there is some behavior change has been realized. And even if it is realized, someone will not think that’s the impact of talking to someone like that. (PTID 56) |

||

|

Even at work, when you just talk about counseling and they want to know how your counseling is, I can just say, Oh, I did Options counseling. Here are my ratings. So, I can use them as part of this work. (PTID 27) |

||

| Putting the face to the rater or to the reviewer, it helped a lot...having an actual relationship with the rater, it helped that it’s not a computer or is not the teacher. It’s just another human being. It’s just a colleague that looks after my work. It helped in that way, knowing that. (PTID 41) | ||

Session Recordings

Counselor Reactions

Counselors described being intimidated at first by having to record their counseling sessions. Nevertheless, most described that they got used to being recorded over time. Some also mentioned the utility of having a recording of each counseling session that they could later review to improve and identify mistakes. Others reviewed their recordings with other counselors at their site, commenting on each other’s sessions as a team-building exercise. Only one out of the 22 interviewed counselors mentioned reservations about the recordings, and stated that participants would hold back their responses because they felt self-conscious being recorded.

How Counselors Presented Recordings to Participants

Audio recording sessions was dependent on participant consent. Some sites asked permission to record at each session, while others asked for permission at the beginning of the study to record all sessions. At some sites, counselors recognized that participants preferred not to be recorded because they believed it would make the counseling session longer. However, counselors emphasized to participants that being recorded would not impact the content of the session. Additionally, at a booster training session midway through the study, the counseling trainer demonstrated how to conduct briefer follow-up sessions while still covering all key points to accommodate participants who indicated they were in a rush. Counselors also described a few strategies to increase participants’ comfort with being recorded, such as placing the recorder in an out-of-sight spot or closer to themselves. In turn, they emphasized to participants that the recordings were for the counselors, not the participants themselves, to help them to become better counselors. Finally, they highlighted that the team reviewing the recordings was located far away, and that the site staff who knew the participants would not be listening.

Participant Reactions

Based on study participant interviews, the most common complaint related to the counseling was that the sessions were time-consuming and could feel burdensome after many hours spent at the clinic. Consistent with counselor perceptions, participants associated the length of the sessions with being recorded. Nevertheless, some associated having their sessions recorded with better counseling sessions and a higher standard for counselors. They also felt that counselors were more accountable for conducting more thorough sessions when they were being recorded.

Session Ratings

Many counselors described feeling anxious about being rated at the beginning of the study, noting concerns about who would rate them and the nature of the feedback. Nevertheless, over time most counselors found the feedback to be very helpful, especially when the rating forms included client-centered comments. They found the comments reassuring when they described what they had done well, and viewed the targeted suggestions for improvement as beneficial to their growth.

Counselors used the feedback from the ratings forms in several ways, including: comparing ratings on individual tasks to the related flip chart section in order to change their approach; placing physical reminders such as sticky notes on the flip chart for future sessions; focusing first on improving their lowest rated task; and comparing the ratings to the recording to determine how to improve their approach. Counselors were motivated when they could see their ratings improving over time after fixing mistakes, and they appreciated that the ratings allowed them to demonstrate the quality of their work. Additionally, counselors shared that meeting their raters in person allowed them to develop a greater mutual understanding and realize that they were colleagues on the same team.

Recommendations for Ratings

Most counselors thought the ratings process should continue in future studies. Some offered specific recommendations for improvement, including: familiarize counselors with the ratings forms and their raters before the first sessions are rated; keep the same rater for each counselor; have a convenient space online to store the ratings; ensure timeliness in completing and sending ratings; and write more comments.

Discussion

In the largest biomedical HIV prevention trial to integrate fidelity monitoring of a client-centered adherence counseling intervention, we found high acceptability for the intervention and the management of fidelity monitoring, including recommendations to continue this approach in future biomedical trials. Critical components of the intervention included development of clear guidelines and materials for both counselors (manual, flipchart) and raters (rating forms, fidelity guide), and thorough training of both groups. Assessment of interrater reliability was necessary, as drift occurred over time. In addition, efforts to provide client-centered comments were important, as counselors reported that the comments were the most helpful part of the rating process.

Although counselors initially felt apprehensive about the fidelity monitoring process, they quickly came to appreciate it. The recordings allowed them to go back and identify specific pieces of the session that they needed to improve, and the ratings provided them with clear guidance for how to improve. While some participants did not want to be recorded, counselors described several efforts they made to put participants at ease with the recordings; primarily, that they were intended to help counselors improve their counseling for the participants. Some participants perceived that counseling sessions were better when counselors were being recorded due to the accountability. Counselors appreciated the skills they learned and reported they would be very likely to use them in the future. In sum, the process to develop the COACH team, a team of counselors and raters working together to provide the best counseling possible for study participants, was successful and can be incorporated into future trials. Such trials may consider developing local rater expertise to enable closer contact between the raters/coaching team and the counselors, with the awareness that the rating team may be responsible for giving critical feedback to their colleagues and may have to navigate the delicate balance of managing counselor reactions and pressure from local supervisors.

There are some important limitations to our findings. First, six of the counselors eligible for the online assessment declined to participate, and twelve others were unable to be reached. While we had positive feedback from those who participated, we cannot know whether the responses from those who declined would be different. It is possible that those who felt most positively about the counseling were most likely to complete the online assessment and agree to be interviewed. Second, while counselors were assigned study ID numbers so as not to be identifiable to the lead investigator, who trained and coached them throughout the counseling intervention, ultimately social desirability could have influenced their responses. Third, although the findings from this study indicate high acceptability of the fidelity monitoring process, there was variability across study sites in rates of recording sessions, which could indicate lower feasibility of the process at sites with lower rates of recordings. Additionally, study participants were recruited from a pool of participants in a prior vaginal ring study in which the counseling sessions were not recorded, which could have influenced their response to the recording of sessions. Nevertheless, counselors from all sites participated in this study and, even at sites with few recordings, no major issues were expressed by counselors or HOPE study participants.

The effectiveness of behavioral interventions, including adherence counseling interventions, depends on consistent and faithful delivery (Miller & Rollnick, 2014). Although prior HIV prevention trials included comprehensive adherence counseling components, they did not audio-record counseling sessions to monitor fidelity. Concerns around staff and participant acceptability of audio-recording counseling sessions, limited budget for counseling staff, and logistical considerations for international studies are a few reasons why counseling sessions were not monitored in prior studies. Our experience in the HOPE study demonstrates that fidelity monitoring of counseling sessions in such studies is not only possible, but also helps guide and support counselors in essential ways, by providing structured feedback and support for adherence counseling practice.

Acknowledgments

The HOPE study was designed and implemented by the Microbicide Trials Network (MTN) funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases through individual grants (UM1AI068633, UM1AI068615 and UM1AI106707), with co-funding from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Institute of Mental Health, all components of the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH). The work presented here was funded by NIH grant UM1AI068633. The HIV Center for Clinical and Behavioral Studies was also supported through a center grant (P30-MH43520, Remien, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- Baer JS, Ball SA, Campbell BK, Miele GM, Schoener EP, & Tracy K (2007). Training and fidelity monitoring of behavioral interventions in multi-site addictions research. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 87(2–3), 107–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balán I, Carballo-Diéguez A, Giguere R, Lama J, & Cranston R (2014). Implementation of an Adherence Counseling Intervention in a Microbicide Trial: Challenges in Changing Counselor Behavior. AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses, 30(S1), A255–A255. [Google Scholar]

- Balán IC, Lentz C, Giguere R, Mayo AJ, Rael CT, Soto-Torres L, … MTN-025/HOPE Study Team. (2020). Implementation of a fidelity monitoring process to assess delivery of an evidence-based adherence counseling intervention in a multi-site bioemedical HIV prevention study. AIDS Care, 1–10. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2019.1709614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll K, Nich C, & Rounsaville B (1998). Utility of therapist session checklists to monitor delivery of coping skills treatment for cocaine abusers. Psychotherapy Research, 8(3), 307–320. [Google Scholar]

- Forsberg L, Källmén H, Hermansson U, Berman AH, & Helgason ÁR (2007). Coding counsellor behaviour in Motivational Interviewing sessions: Inter-Rater reliability for the Swedish Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Code (MITI). Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 36(3), 162–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Dauber S, Lichvar E, Bobek M, & Henderson CE (2015). Validity of therapist self-report ratings of fidelity to evidence-based practices for adolescent behavior problems: Correspondence between therapists and observers. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(2), 229–243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt MS, Garland AF, Nguyen K, & Brookman-Frazee L (2010). Child and family therapy process: Concordance of therapist and observational perspectives. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 37(3), 230–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkle-Parker DJ, Erlen JA, & Dubbert PM (2010). Lessons learned from an HIV adherence pilot study in the Deep South. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(1), 91–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Gallon SL, Hall D, Garcia M, Ceperich S, Farentinos C, Hamilton J, and Hausotter W (2006) Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency. Salem,OR: Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Oregon Health and Science University. [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball S, Nich C, Frankforter TL, & Carroll KM (2009). Correspondence of motivational enhancement treatment integrity ratings among therapists, supervisors, and observers. Psychotherapy Research, 19(2), 181–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh RK, & Barlow DH (2010). The dissemination and implementation of evidence-based psychological treatments: A review of current efforts. American Psychologist, 65(20, 73–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Rollnick S (2014). The effectiveness and ineffectiveness of complex behavioral interventions: Impact of treatment fidelity. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 37(2), 234–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Manuel JK, Wilson PG, & Hendrickson SML (2008). A randomized trial investigating training in motivational interviewing for behavioral health providers. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 36(2), 149–162. [Google Scholar]

- Patterson CH (1983). A client-centered approach to supervision. The Counseling Psychologist, 11(1), 21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund LL, Nilsen P, & Kristensson M (2008). Learning motivational interviewing: Exploring primary health care nurses’ training and counselling experiences. Health Education Journal, 67(2), 102–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wain RM, Kutner BA, Smith JL, Carpenter KM, Hu M-C, Amrhein PC, Nune EV (2015). Self-report after randomly assigned supervision does not predict ability to practice Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 57, 96–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]