Abstract

Purpose

To determine whether there was a significant impact on using cryopreservation of testicular or epididymal sperm upon the outcomes of intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in patients with obstructive azoospermia (OA).

Method

Systematic review and meta-analysis of 20 retrospective studies in databases from January 1, 1995, to June 1, 2020.

Result

Twenty articles were included in this study. A total of 3602 (64.1%) of 5616 oocytes injected with fresh epididymal sperm were fertilized, compared with 2366 (61.2%) of 3862 oocytes injected with cryopreserved sperm (relative risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% confidence interval (CI) (0.90, 1.02), P > 0.05). A total of 303 (44.1%) of 687 ICSI cycles using fresh epididymal sperm resulted in a clinical pregnancy, compared with 150 (36.6%) of 410 ICSI cycles using cryopreserved epididymal sperm (RR 0.84, 95% CI (0.72, 0.97), P < 0.05). In the testis, a total of 2147 (68.7%) of 3125 oocytes injected with fresh sperm were fertilized, compared with 1623 (63.5%) of 2557 oocytes injected with cryopreserved sperm (RR 0.97, 95% CI (0.90, 1.06), P > 0.05). A total of 151 (47.8%) of 316 ICSI cycles using fresh testicular sperm resulted in a clinical pregnancy, compared with 113 (38.2%) of 296 ICSI cycles using cryopreserved sperm (RR 0.87, 95% CI (0.72, 1.05), P > 0.05).

Conclusions

In men with OA, there was a statistical lower clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) by using frozen epididymal sperm compared with fresh epididymal sperm, but showing no difference on fertilization rate (FR). Additionally, FR and CPR were not affected by whether the retrieved testicular sperm was frozen or fresh.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s10815-020-01940-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Cryopreservation, Epididymal spermatozoa, Intracytoplasmic sperm injection, Obstructive azoospermia, Testicular spermatozoa

Introduction

Obstructive azoospermia (OA) is the absence of spermatozoa in the ejaculate due to obstruction of the male reproductive tract and comprises approximately 40% of all azoospermic cases [1]. OA can occur anywhere along the course of the male reproductive tract and is classically characterized by normal spermatogenesis [2]. Microsurgical reconstruction of blocked tract is recommended for many cases of OA by the European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on male infertility 2018. But if microsurgical reconstruction is unsuccessful or not suitable, through testicular or epididymal spermatozoa in combination with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), OA patients could also achieve biological parenthood [3].

Previous studies have shown that surgically retrieved testicular or epididymal spermatozoa used for ICSI have similar outcomes whether fresh or frozen sperm are used [4–6]. However, other studies concluded that cryopreservation of testicular or epididymal spermatozoa may reduce fertilization rate (FR) or clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) [7, 8]. Whether there is a significant impact on the results of ICSI using fresh or frozen sperm on the site of sperm retrieval in OA patients remains controversial. In order to shed light on this topic, a systematic review and meta-analysis was performed. Unlike previous meta-analyses focused on non-obstructive azoospermia (NOA) or did not distinguish the source of sperm from the testis or epididymis [5, 9, 10], we reviewed the outcomes of ICSI on using cryopreservation of testicular or epididymal sperm in patients with OA in this study. And the outcome parameters were FR and CPR.

Materials and methods

Search strategy

We searched the PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library database. The MeSH terms applied were listed as follows: (((((obstructive azoospermia) OR azoospermia)) AND (((((cryopreservation) OR frozen) OR cryopreserved) OR freeze) OR fresh)) AND ((((reproductive techniques, assisted) OR assisted reproductive technology) OR intracytoplasmic sperm injection))) AND (((((outcome) OR fertility)) OR fertilization) OR clinical pregnancy). The aim was to search for all available English-language literatures related to the outcomes of ICSI on using fresh or frozen spermatozoa from the testis or epididymis in patients with OA. Researches were limited to retrospective cohort studies or case-control studies. Since ICSI was started to be used in 1994 [11], the start and end dates of this search are from January 1, 1995, to June 1, 2020.

Study selection: inclusion and exclusion criteria

We strictly followed the participants-interventions-comparisons-outcomes-study design (PICOS) principle, and all retrospective cohort researches or case-control researches were eventually included in this study. Inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients were diagnosed with OA. (2) Sperm retrieval techniques were limited to microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration (MESA), percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA), testicular sperm extraction (TESE), or testicular sperm aspiration (TESA). (3) Fresh and frozen spermatozoa were extracted from the epididymis or testis in OA patients without female infertility factor. (4) The index of ICSI outcomes at least included FR or CPR. (5) Available data could be extracted in the literatures. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Patients with NOA. (2) Not the surgical methods mentioned in the inclusion criteria. (3) The source of frozen or fresh sperm is not explicitly stated to be derived from the epididymis and testis, respectively. (4) The follow-up procedure is not ICSI, and there are no reports of FRs and CPR. (5) We could not extract valid data, non-English-language literature, repeated published research, meta-analysis, and review articles. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of these studies were independently performed by two authors (Hanchao Liu and Linzhi Gao). When disagreements occurred, an agreement was reached through discussion and consultation with another author (Yun Xie).

Quality assessment of the data

Two researchers (Hanchao Liu and Linzhi Gao) independently conducted literature retrieval and extracted data. Newcastle-Ottawa scale (NOS) scale was used to evaluate the methodological quality of selected experimental studies [12]. Specifically, the patient selection, comparability of the study group, and assessment of outcome were made up of 8 items. Using the semi-quantitative principle of the star system, a perfect score of 9 stars (9 points) and a score of ≥ 6 as the high-quality study were included. When there is a disagreement, reach an agreement by discussing it with another author (Yun Xie).

Statistical analyses

This meta-analysis was based on the Preferred Reporting Items of the System Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [13]. The RevMan software (version 5.3) provided by Cochrane collaboration network is used for the analysis (Cochrane Collaboration, Oxford, UK). The counting data were expressed by the relative risk ratio (RR) value and its 95% confidence interval (CI), and the measurement data were expressed by the weighted mean difference (WMD) value and its 95% CI value. P < 0.05 means that the difference was statistically significant. The heterogeneity of the effect was tested by forest map [14]. Chi-square test was used to test the heterogeneity of the included study. If heterogeneity was not statistically significant (P > 0.05, I2 < 50%), the fixed effect model was used for meta-analysis. If heterogeneity was statistically significant (P < 0.05, I2 > 50%), sensitivity analysis was carried out to find the causes of heterogeneity. If the cause of heterogeneity could not be explained by any factors, the random effect model was used for meta-analysis, and the results were interpreted carefully. The funnel plot was drawn by Stata 14.0. We used Egger’s test to evaluate the publication bias. And the publication bias significance level was set P < 0.05.

Results

Study selection process and characteristics of the included studies

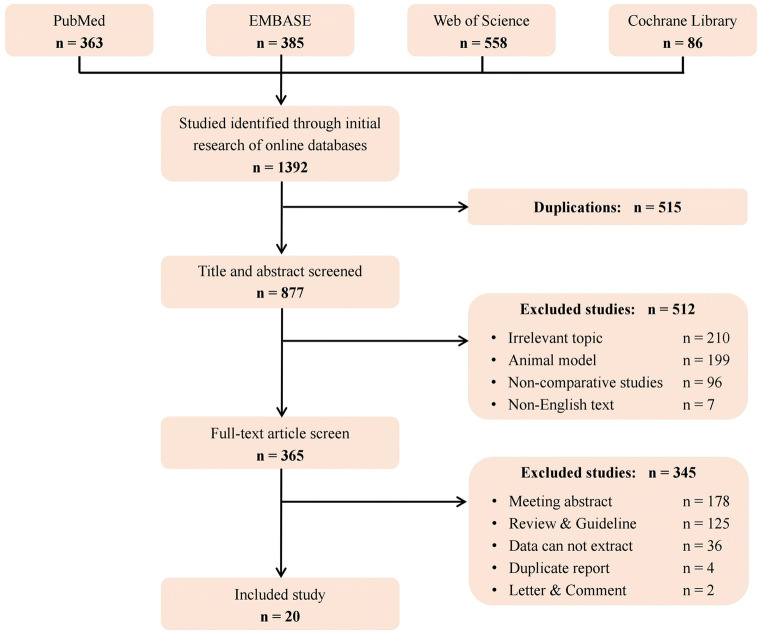

We collected 1392 articles from PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, Cochrane Library database initially. After the screening of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 20 articles were obtained to meet the requirements (Fig. 1) [7, 15–33]. The main characteristics and NOS scores of each article included in this study were shown (Table 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the studies identified, included, and excluded

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included studies

| References | Year | Source | Surgery | Intervention | Female age | Male age | No. of cycles | FR (%) | CPR (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Devroey P et al. | [27] | 1995 | Epididymis | PESA | 31.2 | |||||

| Fresh | 7 | 39/77 | ||||||||

| Frozen | 7 | 28/68 | ||||||||

| Silber SJ et al. | [29] | 1995 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 33 | 20/31 | ||||||||

| Frozen | 7 | 4/7 | ||||||||

| Nagy Z et al. | [28] | 1995 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 31.7 | 38.7 | 43 | 306/547 | 12/40 | |||||

| Frozen | 30.6 | 33.2 | 9 | 59/106 | 3/9 | |||||

| Oates RD et al. | [20] | 1996 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 32.0 | 18 | 41/145 | |||||||

| Frozen | 32.0 | 11 | 28/103 | |||||||

| Sharma RK et al. | [21] | 1997 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 52/101 | |||||||||

| Frozen | 20/30 | |||||||||

| Friedler S et al. | [30] | 1998 | Epididymis | |||||||

| MESA | Fresh | 7 | 33/60 | 2/6 | ||||||

| Frozen | 11 | 62/114 | 5/11 | |||||||

| PESA | Fresh | 17 | 75/134 | 5/16 | ||||||

| Frozen | 10 | 51/98 | 2/8 | |||||||

| Shibahara H et al. | [18] | 1999 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 5 | 35/51 | 3/5 | |||||||

| Frozen | 13 | 34/75 | 3/13 | |||||||

| Tournaye H et al. | [32] | 1999 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 157 | 1125/1821 | 46/145 | |||||||

| Frozen | 118 | 684/1255 | 28/100 | |||||||

| Palermo GD et al. | [31] | 1999 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 33.7 ± 5 | 129 | 1027/1429 | 83/129 | ||||||

| Frozen | 35.4 ± 5 | 112 | 747/1006 | 52/112 | ||||||

| Habermann H et al. | [33] | 2000 | Testis | TESE | ||||||

| Fresh | 9 | 50/86 | 3/9 | |||||||

| Frozen | 25 | 152/238 | 8/25 | |||||||

| Cayan S et al. | [15] | 2001 | Epididymis | MESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 34.3 ± 5.6 | 19 | 139/238 | 6/19 | ||||||

| Frozen | 35.5 ± 5.4 | 19 | 194/313 | 7/19 | ||||||

| Wood S et al. | [7] | 2002 | Epididymis | PESA | 31.9 | 41.5 | ||||

| Fresh | 13 | 58/90 | 2/13 | |||||||

| Frozen | 13 | 57/96 | 3/13 | |||||||

| Park YS et al. | [25] | 2003 | Testis | TESE | 37.5 ± 5.7 | 34.0 ± 5.5 | ||||

| Fresh | 73 | 610/958 | 31/70 | |||||||

| Frozen | 114 | 789/1370 | 37/109 | |||||||

| Wu B et al. | [26] | 2005 | Testis | TESE | 29–56 | |||||

| Fresh | 16 | 174/243 | 11/16 | |||||||

| Frozen | 12 | 100/147 | 5/12 | |||||||

| Kalsi J et al. | [16] | 2010 | Epididymis | MESA, PESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 34.03 ± 4.8 | 173 | 80/173 | |||||||

| Frozen | 33.77 ± 5.2 | 42 | 15/42 | |||||||

| Testis | TESE | |||||||||

| Fresh | 36.48 ± 5.7 | 28 | 9/28 | |||||||

| Frozen | 35.57 ± 3.1 | 15 | 9/15 | |||||||

| Abdel Raheem A et al. | [22] | 2013 | Testis | TESE | ||||||

| Fresh | 19 | 8/19 | ||||||||

| Frozen | 41 | 14/41 | ||||||||

| Karacan M et al. | [23] | 2013 | Testis | TESE | ||||||

| Fresh | 31.7 ± 4.8 | 37.2 ± 8.3 | 67 | 23/67 | ||||||

| Frozen | 37.9 ± 4.4 | 30.9 ± 4.4 | 45 | 13/45 | ||||||

| Kovac JR et al. | [17] | 2014 | Epididymis | PESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 40 ± 1 | 34 ± 1 | 40 | 241/310 | 17/35 | |||||

| Frozen | 37 ± 1 | 34 ± 1 | 11 | 91/124 | 6/11 | |||||

| Yu G et al. | [19] | 2018 | Testis | TESA | ||||||

| Fresh | 30.45 ± 5.03 | 31.85 ± 7.08 | 194 | 1313/1838 | 66/107 | |||||

| Frozen | 29.43 ± 5.40 | 30.30 ± 5.92 | 79 | 589/802 | 27/49 | |||||

| Javed A et al. | [24] | 2019 | Epididymis | PESA | 31.5 ± 4.0 | 35.1 ± 2.0 | ||||

| Fresh | 431/613 | 27/73 | ||||||||

| Frozen | 311/474 | 22/65 |

CPR, clinical pregnancy rate; FR, fertilization rate; MESA, microsurgical epididymal sperm aspiration; PESA, percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration; TESA, testicular sperm aspiration; TESE, testicular sperm extraction

The FR and CPR on using epididymal sperm in ICSI

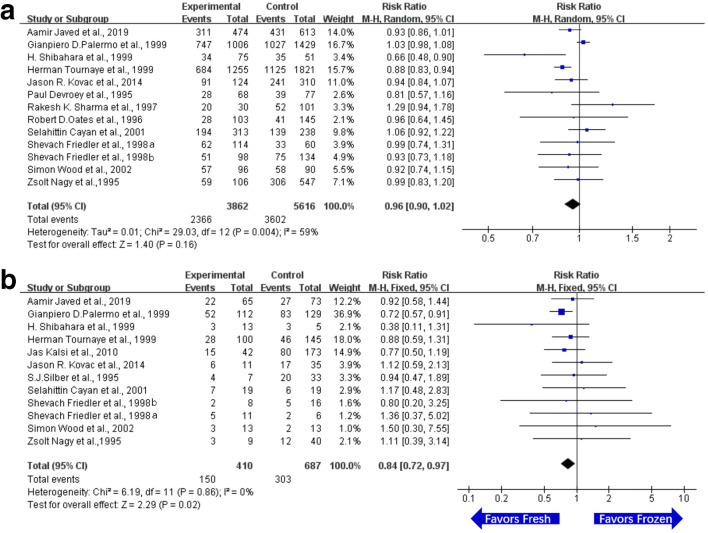

There were 13 related studies of FR on using epididymal sperm in ICSI. The FR of OA patients on using frozen or fresh sperm from epididymis was compared. The results of each experiment were statistically heterogeneous (I2 > 50%). Therefore, random effect model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed that there was no significant difference in FR between the epididymal frozen sperm group and epididymal fresh sperm group (RR = 0.96, 95% CI (0.90, 1.02), P = 0.16). The details are listed in Fig. 2a.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate on using epididymal sperm in ICSI. a Forest plot for fertilization rate. b Forest plot for clinical pregnancy rate. Experimental means frozen group. Control means fresh group. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method

There were 12 related studies of CPR on using epididymal sperm in ICSI. The CPR of OA patients on using frozen or fresh sperm from epididymis was compared. The statistical heterogeneity of each experimental result was less than 50% (I2 < 50%), and the fixed effect model was used for meta-analysis. The results showed that there was a significant difference in CPR between the epididymal frozen sperm group and epididymal fresh sperm group (RR = 0.84, 95% CI (0.72, 0.97), P = 0.02). The results suggested that the CPR on using epididymal fresh sperm was higher than that of epididymal frozen sperm (Fig. 2b).

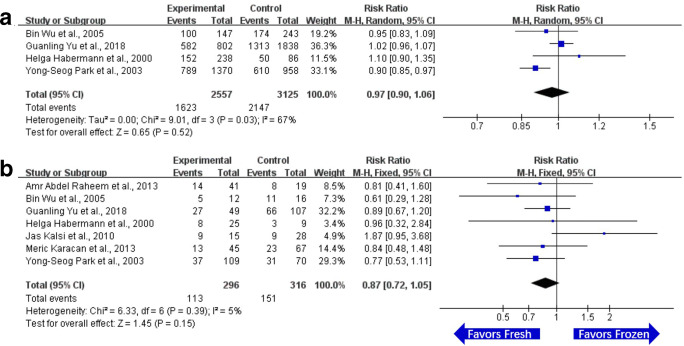

The FR and CPR on using testicular sperm in ICSI

There were 4 related studies of FR on using testicular sperm in ICSI. The FR of OA patients on using frozen or fresh sperm in the testis was compared. There was statistical heterogeneity (I2 > 50%) in each experiment, and random effect model was used for meta-analysis. The results demonstrated that there was no significant difference in FR between the testicular frozen sperm group and testicular fresh sperm group (RR = 0.97, 95% CI (0.90, 1.06), P = 0.52). The details are listed in Fig. 3a.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot and meta-analysis of fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate on using testicular sperm in ICSI. a Forest plot for fertilization rate. b Forest plot for clinical pregnancy rate. Experimental means frozen group. Control means fresh group. CI, confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method

There were 7 related studies of CPR on using testicular sperm in ICSI. The CPR of OA patients on using frozen or fresh sperm in testis was compared. The statistical heterogeneity of each experimental result was less than 50% (I2 < 50%), and the fixed effect model was used for meta-analysis. The results demonstrated that there was no significant difference in CPR between the testicular frozen sperm group and testicular group (RR = 0.87, 95% CI (0.72, 1.05), P = 0.15). The details are listed in Fig. 3b.

Publication bias

The funnel plots were presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. There was no significant publication bias of studies included in our study. In FR and CPR of the epididymis, P = 0.518 and 0.098. And in FR and CPR in the testis, P = 0.946 and 0.729.

Discussion

Sperm cryopreservation is an effective method to preserve male fertility [34]. Having frozen sperm allows more flexibility before undergoing ICSI, which means that there is no need to extract sperm and oocyte at the same time [23]. In addition, sperm cryopreservation could avoid the repeated sperm retrieval technique for each ICSI cycle, thereby minimizing damage to testicular function [35]. However, whether the use of frozen sperm would affect the ICSI outcomes is still controversial. In this study, we found that in men with OA, using cryopreservation of epididymal sperm reduced the CPR in couples undergoing ICSI, but showing no difference between the use of fresh and frozen epididymal sperm when assessing FR. It also showed that the ICSI outcomes, including FR and CPR, were not affected by whether the retrieved testicular sperm was fresh or frozen.

In females, previous studies have reported clearly that the ICSI outcomes in cryopreservation of embryos were better than those of fresh embryos [36, 37]. However, in males, there is a vigorous debate about the impact of using fresh or frozen sperm with regard to ICSI outcomes. By consulting the related literatures published from 1995 to 2020, we found that this situation could be attributed to the following aspects. Firstly, numerous studies confusedly analyze OA and NOA at the same group. Actually, the OA patients, who generally exhibit normal spermatogenesis, are the more ideal objects on studying the impact of sperm cryopreservation concerning ICSI outcomes. Secondly, few studies strictly distinguish the source of sperm, including testicular sperm and epididymal sperm. Finally, insufficient sample size and large differences in female factors would affect the results. Consequently, we hold that to determine whether there is a significant impact on using cryopreservation of sperm upon the outcomes of ICSI, performing a systematic review and meta-analysis between the ICSI outcomes of fresh versus frozen sperm from the different site of retrieval in OA patients is one of the best ways.

The results of this study demonstrated that the CPR was reduced by using the frozen epididymal sperm when compared with fresh epididymal sperm, but there was no statistical difference when assessing FR in OA patients. Previous studies also hold that the CPR of using frozen epididymal sperm in ICSI was actually weaker than that of fresh epididymal sperm [16, 18]. Meanwhile, a considerable number of clinical and basic research have found that cryopreservation does damage sperm, in which the mechanism may be associated with the formation of intracellular ice crystals and accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) [18, 31, 38–42]. A study in deer epididymal sperm showed that the addition of enzyme antioxidants to the cryopreservation expander could increase the survival rate of frozen sperm and improve the motility, acrosome integrity and mitochondrial status of thawed sperm [40]. In the same year, the other study also presented that the use of cryoprotectants could improve sperm motility, plasma membrane integrity, DNA integrity, FR, and quality of embryo [43]. Rezaei N et al. demonstrated that the addition of cryoprotectants could improve the quality of frozen-thawed epididymal sperm in mouse, which was characterized by decreasing the level of ROS and expression of Bax, and increasing the mitochondrial activity and expression of Bcl-2 [44]. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider that epididymal sperm may be greatly affected by cryopreservation in men with OA.

The results of this study also showed that there was no significant difference in FR and CPR between frozen sperm versus fresh sperm from testis in OA patients, which was consistent with the previous studies. When the motility of sperm can be identified, the identified fresh sperm obtained by TESE has better fertilization rate and pregnancy rate than frozen sperm [25]. In other words, the sperm selected during ICSI with good motility contributed to good results in fertilization and pregnancy [45]. For example, hypo-osmotic swelling test (HOST) is related to the in vitro fertilization ability of male spermatozoa, and there is a strong correlation between HOST and in vitro fertilization [46]. Researchers believed the application of HOST may be an important tool for routine identification and selection of active and DNA intact individual spermatozoa to a better ICSI outcome [47].

Besides, it is very important to be able to distinguish the effects of sperm sources on sperm quality. It is well known that the beginning of the epididymis plays an important role in sperm maturation. This is one of the reasons why we divided the testis and epididymis into two groups and compared fresh and frozen sperm in each group. We screened frozen semen and fresh sperm for obstructive azoospermia in epididymis or testis through strict inclusion and exclusion criteria. According to Table 1, we can learn that there is only one study in the literatures we have included that can be used by us to compare epididymis and testis sperm [16]. When researchers defaulted that frozen sperm and fresh sperm are the same sperm, Madelon van Wely et al. proved that the ICSI outcome of epididymal sperm is better than that of testicular sperm in 2015 [48]. Therefore, more studies should be launched to prove that epididymal sperm is better than testicular sperm in OA patients on the basis of strict inclusion and exclusion standard.

According to EAU guidelines on male infertility (2018), when the etiological treatment of OA is ineffective or not suitable, sperm retrieval techniques, such as MESA, PESA, TESE, and TESA, could be taken for the purpose of assisting reproduction. In fact, various sperm retrieval techniques are re-shaping the treatment of OA. Based on this, the conclusions of our study would contribute to guiding the clinical practice in couples undergoing ICSI. For OA patients receiving MESA or PESA, using the fresh epididymal sperm is recommended to minimize the damage to sperm and improve the outcomes of ICSI. While for OA patients receiving TESE or TESA, there is no difference between the use of fresh and frozen testicular sperm. In order to avoid the potential repeated sperm retrieval technique for each ICSI cycle, and keep away from extracting sperm and oocyte at the same time, to our minds, the use of frozen testicular sperm is still recommended in ICSI. Overall, no matter what sperm retrieval technique the OA patients received, the continuous improvement of sperm freezing methods is needed. Additionally, the mechanism of using cryopreservation of epididymal sperm affecting the outcomes of ICSI also needs further explorations in the future.

Although this study makes significant contributions to understanding the impact on using cryopreservation of testicular or epididymal sperm upon the outcomes of ICSI in patients with OA, it still has some limitations. In our meta-analysis, the data presented are based on the previous publications, which all the data and details cannot be extracted completely. There were 12 and 14 studies included in epididymis and only 4 and 7 studies included in testis. We had the result of P < 0.05 in epididymis CPR group. However, it is important to note that some other factors from successful fertilization to clinical pregnancy, such as maternal factors, and embryo quality, may affect the process of implantation and embryo development in each included study. These factors may interpret that some studies have similar fertilization rate but vary widely in clinical pregnancy rate. It is also the limitation of published clinical studies and our meta-analysis. Then, our meta-analysis results in testes of patients with obstructive azoospermia were P > 0.05 in FR and CPR groups. However, this does not mean that freezing does not damage testicular sperm, which may be due to the limitation of study sizes on testicular sperm in patients with OA, the number of cases or some other reasons. And we have mentioned that selecting good-quality sperm is beneficial to the results of ICSI. Therefore, more clinical and experimental studies with strict inclusion and exclusion criteria are needed to further prove this. All the studies included are retrospective studies, and the deviations of individual studies are not controlled by us, such as female factors, detailed clinical characteristics of OA patients. Also, the absence of age, history of recurrent ICSI failure, and other clinical factors of the studies which might adversely affect the outcome. Furthermore, the sample size of clinical data is still limited.

Conclusions

In men with OA, using cryopreservation of epididymal sperm reduced the CPR in couples undergoing ICSI, but showing no impact when assessing FR. Furthermore, the FR and CPR were not affected by whether the retrieved testicular sperm is frozen or fresh.

Electronic supplementary material

Funnel plots illustrating the meta-analysis of fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate on using epididymal or testis sperm in ICSI. a Funnel plot for fertility rate in epididymis. b Funnel plot for clinical pregnancy rate in epididymis. c Funnel plot for fertility rate in testis. d Funnel plot for clinical pregnancy rate in testis (JPG 1403 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)

Authors’ contributions

L.H.C., X.Y., and G.L.Z. made the literature search and data analysis. S.X.Z., L.X.Y., and D.C.H. made study design. L.H.C., X.Y., and G.Y. drew the figures and tables. L.G.H. and G.Y. made the revisions. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

Authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Hanchao Liu, Yun Xie and Linzhi Gao contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Yong Gao, Email: gaoyong9971@163.com.

Guihua Liu, Email: liuguihua@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Jarow JP, Espeland MA, Lipshultz LI. Evaluation of the azoospermic patient. J Urol. 1989;142(1):62–65. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)38662-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wosnitzer MS, Goldstein M. Obstructive azoospermia. Urol Clin N Am. 2014;41(1):83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2013.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sperm retrieval for obstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2008;90(5 Suppl):S213-8. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.The management of obstructive azoospermia: a committee opinion. Fertil Steril. 2019;111(5):873-80. 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Ohlander S, Hotaling J, Kirshenbaum E, Niederberger C, Eisenberg ML. Impact of fresh versus cryopreserved testicular sperm upon intracytoplasmic sperm injection pregnancy outcomes in men with azoospermia due to spermatogenic dysfunction: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2014;101(2):344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicopoullos JD, Gilling-Smith C, Almeida PA, Ramsay JW. The results of 154 ICSI cycles using surgically retrieved sperm from azoospermic men. Hum Reprod. 2004;19(3):579–585. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood S, Thomas K, Schnauffer K, Troup S, Kingsland C, Lewis-Jones I. Reproductive potential of fresh and cryopreserved epididymal and testicular spermatozoa in consecutive intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles in the same patients. Fertil Steril. 2002;77(6):1162–1166. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)03098-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thompson-Cree ME, McClure N, Donnelly ET, Steele KE, Lewis SE. Effects of cryopreservation on testicular sperm nuclear DNA fragmentation and its relationship with assisted conception outcome following ICSI with testicular spermatozoa. Reprod BioMed Online. 2003;7(4):449–455. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)61889-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu Z, Wei Z, Yang J, Wang T, Jiang H, Li H, Tang Z, Wang S, Liu J. Comparison of intracytoplasmic sperm injection outcome with fresh versus frozen-thawed testicular sperm in men with nonobstructive azoospermia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2018;35(7):1247–1257. doi: 10.1007/s10815-018-1206-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nicopoullos JD, Gilling-Smith C, Almeida PA, Norman-Taylor J, Grace I, Ramsay JW. Use of surgical sperm retrieval in azoospermic men: a meta-analysis. Fertil Steril. 2004;82(3):691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.02.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silber SJ, Van Steirteghem AC, Liu J, Nagy Z, Tournaye H, Devroey P. High fertilization and pregnancy rate after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with spermatozoa obtained from testicle biopsy. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(1):148–152. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cota GF, de Sousa MR, Fereguetti TO, Rabello A. Efficacy of anti-leishmania therapy in visceral leishmaniasis among HIV infected patients: a systematic review with indirect comparison. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(5):e2195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis S, Clarke M. Forest plots: trying to see the wood and the trees. BMJ. 2001;322(7300):1479–1480. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7300.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cayan S, Lee D, Conaghan J, Givens CA, Ryan IP, Schriock ED, et al. A comparison of ICSI outcomes with fresh and cryopreserved epididymal spermatozoa from the same couples. Hum Reprod. 2001;16(3):495–499. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.3.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kalsi J, Thum MY, Muneer A, Pryor J, Abdullah H, Minhas S. Analysis of the outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection using fresh or frozen sperm. BJU Int. 2011;107(7):1124–1128. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2010.09545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kovac JR, Lehmann KJ, Fischer MA. A single-center study examining the outcomes of percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration in the treatment of obstructive azoospermia. Urol Ann. 2014;6(1):41–45. doi: 10.4103/0974-7796.127026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibahara H, Hamada Y, Hasegawa A, Toji H, Shigeta M, Yoshimoto T, Shima H, Koyama K. Correlation between the motility of frozen-thawed epididymal spermatozoa and the outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Int J Androl. 1999;22(5):324–328. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2605.1999.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yu G, Liu Y, Zhang H, Wu K. Application of testicular spermatozoa cryopreservation in assisted reproduction. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2018;142(3):354–358. doi: 10.1002/ijgo.12537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oates RD, Lobel SM, Harris DH, Pang S, Burgess CM, Carson RS. Efficacy of intracytoplasmic sperm injection using intentionally cryopreserved epididymal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(1):133–138. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sharma RK, Padron OF. Thomas AJ, Jr, Agarwal A. Factors associated with the quality before freezing and after thawing of sperm obtained by microsurgical epididymal aspiration. Fertil Steril. 1997;68(4):626–631. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(97)00274-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abdel Raheem A, Rushwan N, Garaffa G, Zacharakis E, Doshi A, Heath C, Serhal P, Harper JC, Christopher NA, Ralph D. Factors influencing intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) outcome in men with azoospermia. BJU Int. 2013;112(2):258–264. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2012.11714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karacan M, Alwaeely F, Erkan S, Çebi Z, Berberoğlugil M, Batukan M, Uluğ M, Arvas A, Çamlıbel T. Outcome of intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycles with fresh testicular spermatozoa obtained on the day of or the day before oocyte collection and with cryopreserved testicular sperm in patients with azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2013;100(4):975–980. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Javed A, Ramaiah MK, Talkad MS. ICSI using fresh and frozen PESA-TESA spermatozoa to examine assisted reproductive outcome retrospectively. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2019;62(6):429–437. doi: 10.5468/ogs.2019.62.6.429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Park YS, Lee SH, Song SJ, Jun JH, Koong MK, Seo JT. Influence of motility on the outcome of in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection with fresh vs. frozen testicular sperm from men with obstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2003;80(3):526–530. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(03)00798-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu B, Wong D, Lu S, Dickstein S, Silva M, Gelety TJ. Optimal use of fresh and frozen-thawed testicular sperm for intracytoplasmic sperm injection in azoospermic patients. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2005;22(11-12):389–394. doi: 10.1007/s10815-005-7481-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Devroey P, Silber S, Nagy Z, Liu J, Tournaye H, Joris H, et al. Ongoing pregnancies and birth after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with frozen-thawed epididymal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1995;10(4):903–906. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a136058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagy Z, Liu J, Cecile J, Silber S, Devroey P, Van Steirteghem A. Using ejaculated, fresh, and frozen-thawed epididymal and testicular spermatozoa gives rise to comparable results after intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 1995;63(4):808–815. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)57486-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Silber SJ, Devroey P, Tournaye H, Van Steirteghem AC. Fertilizing capacity of epididymal and testicular sperm using intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) Reprod Fertil Dev. 1995;7(2):281–292. doi: 10.1071/rd9950281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Friedler S, Raziel A, Soffer Y, Strassburger D, Komarovsky D, Ron-El R. The outcome of intracytoplasmic injection of fresh and cryopreserved epididymal spermatozoa from patients with obstructive azoospermia--a comparative study. Hum Reprod. 1998;13(7):1872–1877. doi: 10.1093/humrep/13.7.1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palermo GD, Schlegel PN, Hariprashad JJ, Ergün B, Mielnik A, Zaninovic N, et al. Fertilization and pregnancy outcome with intracytoplasmic sperm injection for azoospermic men. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(3):741–748. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.3.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tournaye H, Merdad T, Silber S, Joris H, Verheyen G, Devroey P, et al. No differences in outcome after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with fresh or with frozen-thawed epididymal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1999;14(1):90–95. doi: 10.1093/humrep/14.1.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Habermann H, Seo R, Cieslak J, Niederberger C, Prins GS, Ross L. In vitro fertilization outcomes after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with fresh or frozen-thawed testicular spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 2000;73(5):955–960. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00416-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tournaye H, Dohle GR, Barratt CL. Fertility preservation in men with cancer. Lancet. 2014;384(9950):1295–1301. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(14)60495-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katz DJ, Kolon TF, Feldman DR, Mulhall JP. Fertility preservation strategies for male patients with cancer. Nat Rev Urol. 2013;10(8):463–472. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2013.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coutifaris C. "Freeze only"--an evolving standard in clinical in vitro fertilization. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):577–579. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1606213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen ZJ, Shi Y, Sun Y, Zhang B, Liang X, Cao Y, Yang J, Liu J, Wei D, Weng N, Tian L, Hao C, Yang D, Zhou F, Shi J, Xu Y, Li J, Yan J, Qin Y, Zhao H, Zhang H, Legro RS. Fresh versus frozen embryos for infertility in the polycystic ovary syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(6):523–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1513873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mazur P. The role of intracellular freezing in the death of cells cooled at supraoptimal rates. Cryobiology. 1977;14(3):251–272. doi: 10.1016/0011-2240(77)90175-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Malo C, Elwing B, Soederstroem L, Lundeheim N, Morrell JM, Skidmore JA. Effect of different freezing rates and thawing temperatures on cryosurvival of dromedary camel spermatozoa. Theriogenology. 2019;125:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2018.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fernández-Santos MR, Martínez-Pastor F, García-Macías V, Esteso MC, Soler AJ, Paz P, et al. Sperm characteristics and DNA integrity of Iberian red deer (Cervus elaphus hispanicus) epididymal spermatozoa frozen in the presence of enzymatic and nonenzymatic antioxidants. J Androl. 2007;28(2):294–305. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal A, Prabakaran SA, Said TM. Prevention of oxidative stress injury to sperm. J Androl. 2005;26(6):654–660. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.05016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bilodeau JF, Chatterjee S, Sirard MA, Gagnon C. Levels of antioxidant defenses are decreased in bovine spermatozoa after a cycle of freezing and thawing. Mol Reprod Dev. 2000;55(3):282–288. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2795(200003)55:3<282::Aid-mrd6>3.0.Co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yildiz C, Ottaviani P, Law N, Ayearst R, Liu L, McKerlie C. Effects of cryopreservation on sperm quality, nuclear DNA integrity, in vitro fertilization, and in vitro embryo development in the mouse. Reproduction. 2007;133(3):585–595. doi: 10.1530/rep-06-0256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rezaei N, Mohammadi M, Mohammadi H, Khalatbari A, Zare Z. Acrosome and chromatin integrity, oxidative stress, and expression of apoptosis-related genes in cryopreserved mouse epididymal spermatozoa treated with L-Carnitine. Cryobiology. 2020;95:171–176. doi: 10.1016/j.cryobiol.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ved S, Montag M, Schmutzler A, Prietl G, Haidl G, van der Ven H. Pregnancy following intracytoplasmic sperm injection of immotile spermatozoa selected by the hypo-osmotic swelling-test: a case report. Andrologia. 1997;29(5):241–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.1997.tb00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rogers BJ, Parker RA. Relationship between the human sperm hypo-osmotic swelling test and sperm penetration assay. J Androl. 1991;12(2):152–158. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stanger JD, Vo L, Yovich JL, Almahbobi G. Hypo-osmotic swelling test identifies individual spermatozoa with minimal DNA fragmentation. Reprod BioMed Online. 2010;21(4):474–484. doi: 10.1016/j.rbmo.2010.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Wely M, Barbey N, Meissner A, Repping S, Silber SJ. Live birth rates after MESA or TESE in men with obstructive azoospermia: is there a difference? Hum Reprod. 2015;30(4):761–766. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Funnel plots illustrating the meta-analysis of fertilization rate and clinical pregnancy rate on using epididymal or testis sperm in ICSI. a Funnel plot for fertility rate in epididymis. b Funnel plot for clinical pregnancy rate in epididymis. c Funnel plot for fertility rate in testis. d Funnel plot for clinical pregnancy rate in testis (JPG 1403 kb)

(DOCX 20 kb)