Summary

Women with catamenial epilepsy often experience increased seizure burden near the time of ovulation (periovulatory) or menstruation (perimenstrual). To date, a rodent model of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) that exhibits similar endogenous fluctuations in seizures has not been identified. Here, we investigated whether seizure burden changes with the estrous cycle in the intrahippocampal kainic acid (IHKA) mouse model of TLE. Adult female IHKA mice and saline-injected controls were implanted with EEG electrodes in the ipsilateral hippocampus. At one and two months post-injection, 24/7 video-EEG recordings were collected and estrous cycle stage was assessed daily. Seizures were detected using a custom convolutional neural network machine learning process. Seizure burden was compared within each mouse between diestrus and combined proestrus and estrus days (pro/estrus) at two months post-injection. IHKA mice showed higher seizure burden on pro/estrus compared with diestrus, characterized by increased time in seizures and longer seizure duration. When all IHKA mice were included, no group differences were observed in seizure frequency or EEG power. However, increased baseline seizure burden on diestrus was correlated with larger cycle-associated differences, and when analyses were restricted to mice that showed the severe epilepsy typical of the IHKA model, increased seizure frequency on pro/estrus was also revealed. Controls showed no differences in EEG parameters with cycle stage. These results suggest that the stages of proestrus and estrus are associated with higher seizure burden in IHKA mice. The IHKA model may thus recapitulate at least some aspects of reproductive cycle-associated seizure clustering.

Keywords: convolutional neural network, EEG, epilepsy, estrous cycle, hippocampus, kainic acid

1. Introduction

Seizure clustering and increased seizure susceptibility in relation to the menstrual cycle, or catamenial epilepsy, affects approximately 31–60% of women with epilepsy (Laidlaw, 1956; Reddy, 2009). In women with catamenial epilepsy who maintain regular menstrual cycles, increased seizure burden occurs primarily near menstruation or ovulation (Herzog et al., 1997; Newmark and Penry, 1980). Rodent models of catamenial-like seizure exacerbation have primarily employed manipulations of circulating progesterone and/or central neurosteroid levels to mimic the late luteal phase drop in progesterone, and subsequent lowering of central progesterone-derived neurosteroid concentrations (Gangisetty and Reddy, 2010; Joshi and Kapur, 2019; Reddy et al., 2012). These models are designed to promote reduced neurosteroid potentiation of GABAA receptor-mediated synaptic inhibition, resulting in a hyperexcitable state. It remains unclear, however, which rodent models of epilepsy display catamenial-like seizure exacerbations in relation to endogenous fluctuations in endocrine stage across the estrous cycle in the absence of additional exogenous hormone and other drug treatments.

To date, most studies examining the impact of estrous cycle stage on seizure susceptibility in rodents have used acute models of seizure induction (Christian et al., 2020). With regard to chemoconvulsant triggers, sensitivity to seizures induced by systemic pentylenetetrazole, bicuculline, kainic acid (KA), or gammabutyrolactone injection is higher in estrous compared with diestrous animals (Finn and Gee, 1994; Maguire et al., 2005; Riazi et al., 2004; Santos et al., 2018). By contrast, the rate of status epilepticus induction after systemic pilocarpine treatment appears to be lower in estrous rats (Scharfman et al., 2005), although other studies have found no effect of estrous cycle stage on pilocarpine susceptibility (Brandt et al., 2016). Similarly, afterdischarge threshold with kindling stimulation is lowest in proestrous rats (Edwards et al., 1999), and hippocampal excitability, as measured in ex vivo brain slices, increases during proestrus and estrus relative to metestrus (Scharfman et al., 2003). So far, less is known about endogenous fluctuations in epileptiform activity across the estrous cycle in rodent models of chronic epilepsy; one study documented increased interictal spike frequency on metestrus and diestrus following systemic KA injection in rats (D’Amour et al., 2015), and in WAG/Rij rats, a model of absence epilepsy, spike-and-wave discharges appear to increase during proestrus (van Luijtelaar et al., 2001).

It is still unclear whether spontaneous seizure burden changes with the estrous cycle in rodent models of epilepsies highly associated with catamenial seizure patterning, such as temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Bazan et al., 2005; Quigg et al., 2009). The intrahippocampal KA (IHKA) mouse model recapitulates several EEG and histopathological features of human TLE (Bouilleret et al., 1999; Levesque and Avoli, 2013; Riban et al., 2002) and has recently gained increased use in preclinical research (Desloovere et al., 2019; Hubbard et al., 2016; Kilias et al., 2018; Krook-Magnuson et al., 2013; Murphy et al., 2012; Wong et al., 2018). Moreover, we documented epilepsy-associated changes in circulating sex steroids across the estrous cycle in IHKA mice (Li et al., 2018), leading us to hypothesize that seizure burden may also fluctuate with estrous cycle stage in this model.

Here, we examined 24/7 video-EEG recordings from IHKA and saline-injected control female mice obtained in conjunction with ongoing studies that included both transgenic and wild-type mice after injection targeting of either left or right hippocampus. Despite the differences in mouse genotype and laterality of injection targeting, consistent features emerged with respect to patterning of seizure activity in association with estrous cycle stage. Specifically, seizure burden was increased on proestrus and estrus compared with diestrus.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (Protocol 17183). All animals had food and water available ad libitum and were housed in a 14 h:10 h light:dark cycle with lights off at 1800 h. Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH)-Cre:Ai9 transgenic mice used in this study were bred by crossing GnRH-Cre+ females (Jackson Labs #021207) and Ai9 males (Jackson Labs #007909) on the C57BL/6J background. Cre+ female pups of this cross at postnatal day 42 and older were used due to requirements for ongoing projects in our laboratory that require fluorescent tdTomato expression in hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone neurons (Li et al., 2018). To verify that Cre recombinase and/or tdTomato expression did not influence the EEG results presented here, we also examined C57BL/6J female mice that were obtained from Jackson Labs at 6 weeks of age.

2.2. Estrous cycle monitoring

Estrous cycle monitoring was conducted from 0900–1100 h and performed both before and after saline/KA injection (Figure 1A) using a vaginal cytology protocol described previously (Pantier et al., 2019). All mice in this study displayed pre-injection estrous cycles with regular 4- to 5-day periods, consistent with previous findings (Byers et al., 2012; Li et al., 2017; Nelson et al., 1981). Proestrus is difficult to determine in many mice, and smears appearing as a transition state between proestrus and estrus are common. Therefore, smears with more nucleated epithelial cells than cornified cells were classified as proestrus, whereas smears with more cornified epithelial cells were classified as estrus. A stage of “few” was designated when very few cells could be obtained, and was typically observed when diestrus was prolonged (Pantier et al., 2019). Cycle length was calculated as the time to progress from one day of estrus to the next, with each stage displayed in order in between (Li et al., 2017; Pantier et al., 2019). At least one cycle was calculated for each mouse at each time point examined; when two cycles were detected, these were averaged for group comparisons.

Figure 1:

Experimental design and development of convolutional neural network machine learning for seizure detection. A) Timeline of procedures and experiments. dpi = days post-injection B) Flowchart of steps in validating the machine learning seizure detection algorithm and analyzing EEG recordings. The version of Seizure Analyzer software used is available in (Zeidler et al., 2018).

2.3. Stereotaxic surgeries

Epilepsy induction by unilateral KA (Tocris #0222; 50 nl of 20 mM in 0.9% sterile saline) injection in left or right dorsal hippocampus (from Bregma: 2.0 mm posterior, 1.5 mm lateral, 1.4 mm ventral to the cortical surface) was performed on diestrus as previously described (Li et al., 2017). Controls were injected with an equivalent volume of saline. Saline/KA injection was assigned randomly. 14–17 days after injection, a twisted bipolar EEG electrode (P1 Technologies #MS303/3-A/SPC) was implanted in the ipsilateral hippocampus slightly dorsal and lateral to the injection location (from Bregma: 1.25 mm ventral, 1.75 mm lateral). Anchor microscrews (J.I. Morris Co. #FF00CE188) were inserted in the skull bilaterally posterior to the electrode, with two screws placed over parietal cortex and two over the cerebellum. Electrode and screw implants were stabilized to the skull using dental cement (Coltene Whaledent #H-00280).

All surgical procedures were performed under isoflurane anesthesia (2–3%, vaporized in 100% oxygen; Clipper Distributing Company #57319-507-06). For analgesia, mice were administered subcutaneous carprofen (5 mg/kg, Zoetis #PI 4019448) at the beginning of each surgery and 2.5% lidocaine plus 2.5% prilocaine cream (Human Pharmaceuticals #191.49600.3) was applied topically on sutured incisions and at the base of the dental cement implant, along with antibiotic Neosporin gel (Johnson and Johnson). Mice were individually housed after electrode implantation and allowed to recover >7 days before recording.

2.4. Video-EEG recording

For EEG recordings, mice were singly housed in custom plastic cages (L*W*D = 20*22*20 cm) in a dedicated recording room and connected through an electrical commutator (P1 Technologies #SL2C/SB) to a Brownlee 440 amplifier (NeuroPhase) with the gain set at 1K. EEG signals, recorded as the local field potential differential between the two electrodes (Armstrong et al., 2013), were sampled at 2 kHz and digitized (National Instruments) to a Dell recording computer with recorder software written in MATLAB (Armstrong et al., 2013) running in Windows 10. Videos were obtained using webcams (Logitech #C930e) synchronized to the recorder software. Mice were EEG- and video-recorded at 21–35 days post-injection (1 month) and again from 49–70 days post-injection (2 months) (Figure 1A). Mice were returned to the colony and individually housed in regular cages for 14 days between recording periods. Both EEG and videos were recorded 24/7, with red light illumination provided to enable video recording in the dark phase of the light cycle.

2.5. Development and implementation of machine learning method for seizure detection and analysis

A convolutional neural network (CNN) architecture was designed in TensorFlow (www.tensorflow.org) and trained to detect seizures recorded from the EEG (Figure 1B). The supporting Python code is available at https://github.com/ChristianLabUIUC/SeizureDetector. The raw EEG signal (down-sampled to 250 Hz) was entered as the input layer (height*width = 1*1024). After the input layer, the CNN consisted of three convolution-pooling units, a flattened layer, a dropout layer, a dense layer, and a final output layer. Each convolution-pooling unit consisted of a convolution layer and a max pooling layer. The 1st, 3rd and 5th layers were convolution layers, which computed the signal with kernel size*num of kernel as 1*64*16, 1*32*32, and 1*16*8, respectively. The 2nd, 4th, and 6th layers were max pooling layers with 1*2 sub-sampling. The signals were then flattened (7th layer) and connected to a dropout layer (8th) for regularization. The 9th layer was a dense layer connected to the final output layer by a sigmoid activation function.

Events used in training and evaluating the CNN model were extracted using the MATLAB-based software, Seizure Analyzer (Zeidler et al., 2018), from a subset of recordings selected at random in a blinded fashion encompassing data from across the estrous cycle. These events were designated as epileptiform (high-amplitude seizure spikes occurring at 2 Hz frequency and higher, with at least 8 spikes occurring within 4 seconds) or non-epileptiform (containing movement artifacts). Extracted EEG traces that contained epileptiform events were used as positive data in training the CNN. All data in the training dataset were set to contain 1024 sampling points. If the EEG trace contained an epileptiform event extending beyond 1024 points, a random portion of 1024 continuous points within the event was selected. Non-epileptiform events and other randomly extracted stable baseline traces were used as negative data. The amplitudes of all traces were normalized to a −1 to +1 range centered on the baseline of the trace. A dataset for model training and evaluation consisting of 46762 total events extracted from both control and IHKA mice was randomly split into training data (~70%, or 37264 events) and validation data (~30%, or 9498 events). In testing the CNN model with the validation dataset, 92% recall, 93% specificity, 93% precision, and 93% accuracy was achieved when the dataset was balanced (positive:negative events = 1:1). On an imbalanced validation dataset (positive:negative = 5:1), the model achieved 91% recall, 93% specificity, 73% precision, and 92% accuracy.

Upon successful CNN training, a sliding window method (window size = 1024 points, step = 750 points) was applied to detect seizures from all recordings collected from both control and IHKA mice across the different stages of the estrous cycle in a blinded manner. Consecutive windows marked as positive (epileptiform) were combined as one seizure. Minimal seizure duration was set at 6 seconds and the minimal interictal interval was set at 5 seconds. The end of a seizure was delineated when the spiking fell below the 2 Hz threshold after at least a 6-s bout of epileptiform spiking; if a subsequent epileptiform event initiated within 5 s, the two events were combined into one epileptiform event for analyses, with the end of the longer epileptiform event determined by spiking rate falling below the 2 Hz threshold. These analysis parameters were applied to all EEG recordings from all mice and all cycle stages for consistency, so that differences in detection settings would not produce artificial differences in seizure parameters between cycle stages.

Note that when seizures are frequent (i.e., ≥1% of time spent in seizure activity), the CNN model detects the events with high accuracy. If seizure frequency is low, however, visual confirmation of seizures and other behaviors are needed to accurately separate epileptiform events from false positive events (Figure S1). Therefore, seizures identified from EEG traces in mice with low seizure frequency near the false positive detection rate were verified in videos by an observer blinded to mouse identity and cycle stage. Paroxysmal activity scored at Racine stage 3 and above was the minimum criterion for behavioral seizure classification. The IHKA mouse model most often displays nonconvulsive electrographic hippocampal seizures (Levesque and Avoli, 2013; Twele et al., 2017). Therefore, lack of movement (but not sleeping) was also classified as seizure activity. Spikes that occurred with exploring, grooming, eating, or drinking behaviors were classified as movement artifacts.

All detected days of diestrus, proestrus, and estrus at 2 months post-injection were used in EEG analyses (Table S1). Recordings from 2100 to 0300 h were considered as the transition times between two different estrous cycle days and were not used in analyses. Similarly, metestrus and “few” stages were considered as transition stages between diestrus and pro/estrus and were not included in the present analyses. Seizure burden for each mouse was quantified by the percentage of time in seizure activity, seizure frequency (number of seizures per hour), average seizure duration, and total seizure EEG power, calculated as the short-term Fourier-transformed signal power at frequencies from 0.1–100 Hz averaged across the time axis.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using Python or OriginPro. Data normality was tested using Shapiro-Wilk tests. Comparisons of cycle length and time spent in diestrus between control and IHKA mice were performed using two-tailed t-tests. Comparisons of EEG parameters between cycle stages were performed as parametric two-tailed paired t-tests or nonparametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests as appropriate based on data normality. Correlations were tested using Spearman’s correlations. Data are presented as means ± SEM. p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Evaluation of custom CNN machine learning seizure detection indicates high accuracy with low false-positive detection rate

Data obtained from GnRH-Cre:Ai9 mice (6 saline-injected, 14 KA-injected) were used to evaluate the detection accuracy of the custom CNN seizure detection method (Table 1). In this cohort, 12/14 KA-injected mice developed epilepsy (example seizures shown in Figure 2A). For all saline-injected mice and two KA-injected mice, all detected “seizure” events were verified as false-positive artifacts (Twele et al., 2017) by examining the EEG traces and videos. Based on the data from these mice, the false-positive detection rate of the CNN method is 0.08 events per hour, in agreement with other methods (Kim et al., 2020; Twele et al., 2017; Zeidler et al., 2018).

Table 1:

Seizure detection result summary for GnRH-Cre:Ai9 mice, incorporating all days recorded at 2 months after saline/KA injection.

| Treatment group | n of mice | % time in seizure | seizures per hour |

|---|---|---|---|

| saline | 6 | 0.026 + 0.006 | 0.08 + 0.02 |

| KA-no | 2 | 0.000003; 0.001 | 0.06; 1.1 |

| KA-epilepsy | 11 | 11.4 + 2.6 | 19.99 ± 4.1 |

Mean ± SEM values for percentage of time spent in seizure activity (% time in seizure) and number of seizures per hour. KA-no = KA-injected mice that did not show confirmed spontaneous recurrent seizures in EEG and were excluded from further study. KA-epilepsy = KA-injected mice that developed spontaneous recurrent seizures. One additional KA-injected mouse was confirmed to develop epilepsy, but seizure parameters were not quantified due to excessive noise in the EEG trace. Note that because standard error values could not be calculated for the two KA-no mice, the individual data points are provided for this group instead, and false positive detection events were used for calculations for saline and KA-no groups.

Figure 2:

Different estrous cycle disruption patterns in control and IHKA mice after first and second habituation to tethered EEG recording. A) Example EEG traces for seizures at 2 months after KA injection. Red arrows indicate the start and end of each seizure, as detected by the custom CNN machine learning seizure detection algorithm. The top 2 traces are from mice with frequent seizures, and the bottom 2 traces are from a mouse with infrequent seizures. B) Boxplots for estrous cycle length (in days) in saline-injected controls (n=7) and IHKA mice (n=18) at one month after injection (left) and 2 months after injection (right). Boxplots indicate 1.5 times the interquartile range, the mean, the median, and 25–75% range. *p<0.05, t-test

3.2. Transient disruption to estrous cyclicity in response to tethered EEG recording in control mice

Introducing mice to a tethered EEG recording system, a new caging environment, and other stressors can potentially cause estrous cycle disruption independent of effects of epilepsy per se. Such effects could complicate the analysis of relationships between spontaneous seizure burden and the estrous cycle. To understand the effect of exposure to the tethered EEG recording system on estrous cycle regularity, the cycle period (length in days) at both 1 and 2 months after intrahippocampal saline/KA injection were calculated for the mice listed in Table S1. The initial 5 days after connecting to the EEG system were set as habituation phases for both 1 month and 2 months post-injection and were not included in these analyses.

After habituation upon the first exposure to EEG tethering, both control and IHKA mice displayed prolonged estrous cycle length, a characteristic of estrous cycle disruption (Li et al., 2017), and a significant difference was not detected between these groups (controls 7.9 ± 1.6 d; IHKA 8.3 ± 0.8 d; p=0.79) (Figure 2B). After another habituation upon the second exposure to EEG tethering, however, control mice showed the expected 4- to 5-day cycle length (4.7 ± 0.2 d) (Figure S2), but IHKA mice continued to show prolonged cycle periods (7.1 ± 0.6 d; p=0.013) (Figure S3). Similarly, there was no difference between control and IHKA mice in the percentage of time spent in diestrus at 1 month post-injection (p=0.3), but at 2 months IHKA mice spent more time in diestrus (controls 35.9 ± 3.8%; IHKA 53.8 ± 4%; p=0.016), another signature of cycle disruption (Li et al., 2017). There were no correlations in IHKA mice between EEG parameters, nor cycle-dependent changes in these parameters, as functions of the estrous cycle length at 2 months post-habituation (Table S2), indicating that the degree of estrous cycle disruption was not related to epilepsy severity.

3.3. Seizure burden is higher on pro/estrus than on diestrus in IHKA mice

EEG recording data from 18 mice (11 GnRH-Cre:Ai9 and 7 C57BL/6J) were used to examine changes in EEG parameters with estrous cycle stage in IHKA mice, exceeding the required minimum sample size estimated by power analysis for 95% power with alpha=0.05, calculated at 16 mice (Tables S1, S3, S4). 1 GnRH-Cre:Ai9 KA-injected mouse was excluded due to excessive noise in the EEG traces. Two mice had fewer than five seizures in the desired period, and therefore were not included in calculations of average seizure duration or total EEG power. Saline-injected mice (5 GnRH-Cre:Ai9 and 2 C57BL/6J) were used in the analysis as false positive controls. 1 GnRH-Cre:Ai9 saline-injected mouse was excluded because no seizure-like false positive events were detected. EEG analyses were performed using data collected at the 2-month recording time point after habituation.

In IHKA mice that showed at least 1 day each in both proestrus and estrus (n=8) (Figure S3), EEG parameters were not significantly different between these two cycle stages (percentage of time in seizures p=0.84; seizure frequency p=0.69; seizure duration p=0.33). The data for all mice were thus combined as ”pro/estrus” to reduce the chance of mislabeling each stage, as well as to increase the power of further within-animal analyses comparing these stages with diestrus.

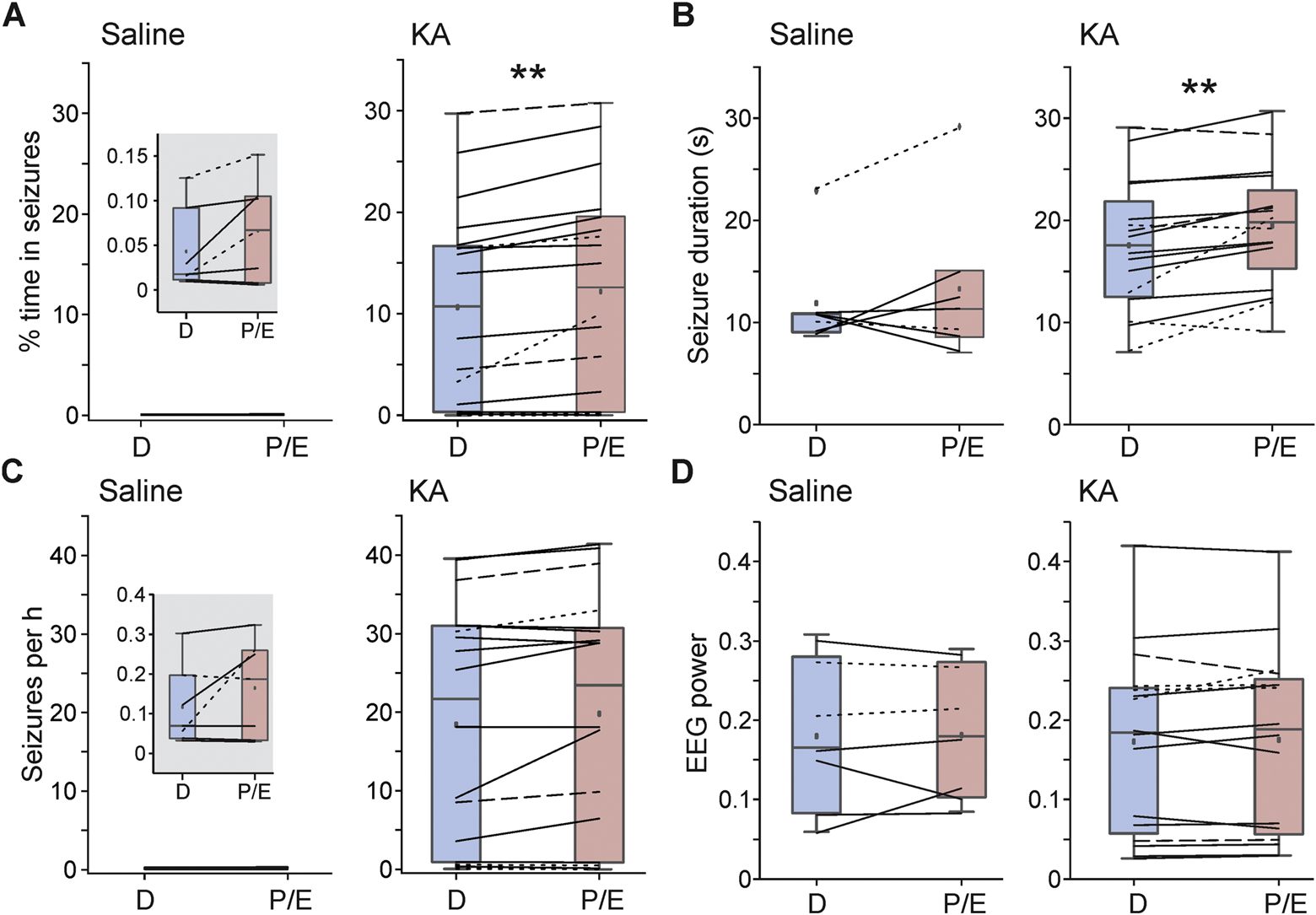

On average, IHKA mice spent more time in seizures during pro/estrus (12.2 ± 2.5%) compared with diestrus (10.6 ± 2.3%) (p=0.002) (Figure 3A). Seizure duration was also longer on pro/estrus (19.5 ± 1.5 s) compared with diestrus (17.6 ± 1.6 s) (p=0.003) (Figure 3B). However, neither mean seizure frequency nor EEG power in seizure activity was different between cycle stages (p=0.08 frequency, p=0.59 EEG power) (Figure 3C–D). The high number of seizures observed in the majority of animals is consistent with previous observations in IHKA mice obtained by multiple groups (Kim et al., 2020; Twele et al., 2016; Zeidler et al., 2018).

Figure 3:

Time in seizures and seizure duration are increased on pro/estrus in IHKA mice, with no cycle-dependent changes in false-positive events in saline-injected controls. A-C) Boxplots and data distribution for percentage of time spent in seizures (A), seizure duration (B), seizure frequency (C), and total EEG power in seizures (D) on diestrus and pro/estrus. Solid lines = GnRH-Cre:Ai9 mice with right-sided injection (5 saline, 11 KA); dashed lines = C57BL/6J mice with right-sided injection (2 KA); dotted lines = C57BL/6J mice with left-sided injection (2 saline, 5 KA). Note that all IHKA mice are included in these analyses, irrespective of the severity of epilepsy. Insets are used for the saline group for percentage of time spent in seizures and seizure frequency (note that these events are not true seizures but are false-positive artifacts included for comparison). Boxplots indicate data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range, the mean, the median, 25–75% range, and outliers in the dataset, which were not excluded from analyses. **p<0.01 A, C: Wilcoxon signed-rank tests; B, D: paired t-tests

To confirm that these differences were not due to potential biases in the seizure detection algorithm, the same analyses were applied to false-positive events detected from control saline-injected mice. No significant differences were detected between pro/estrus and diestrus in controls (percent time in seizures: p=0.09; seizure frequency: p=0.18; seizure duration: p=0.4; EEG power p=0.92; Figure 3).

3.4. Magnitude of change in time spent in seizure activity on pro/estrus compared with diestrus is correlated with epilepsy severity

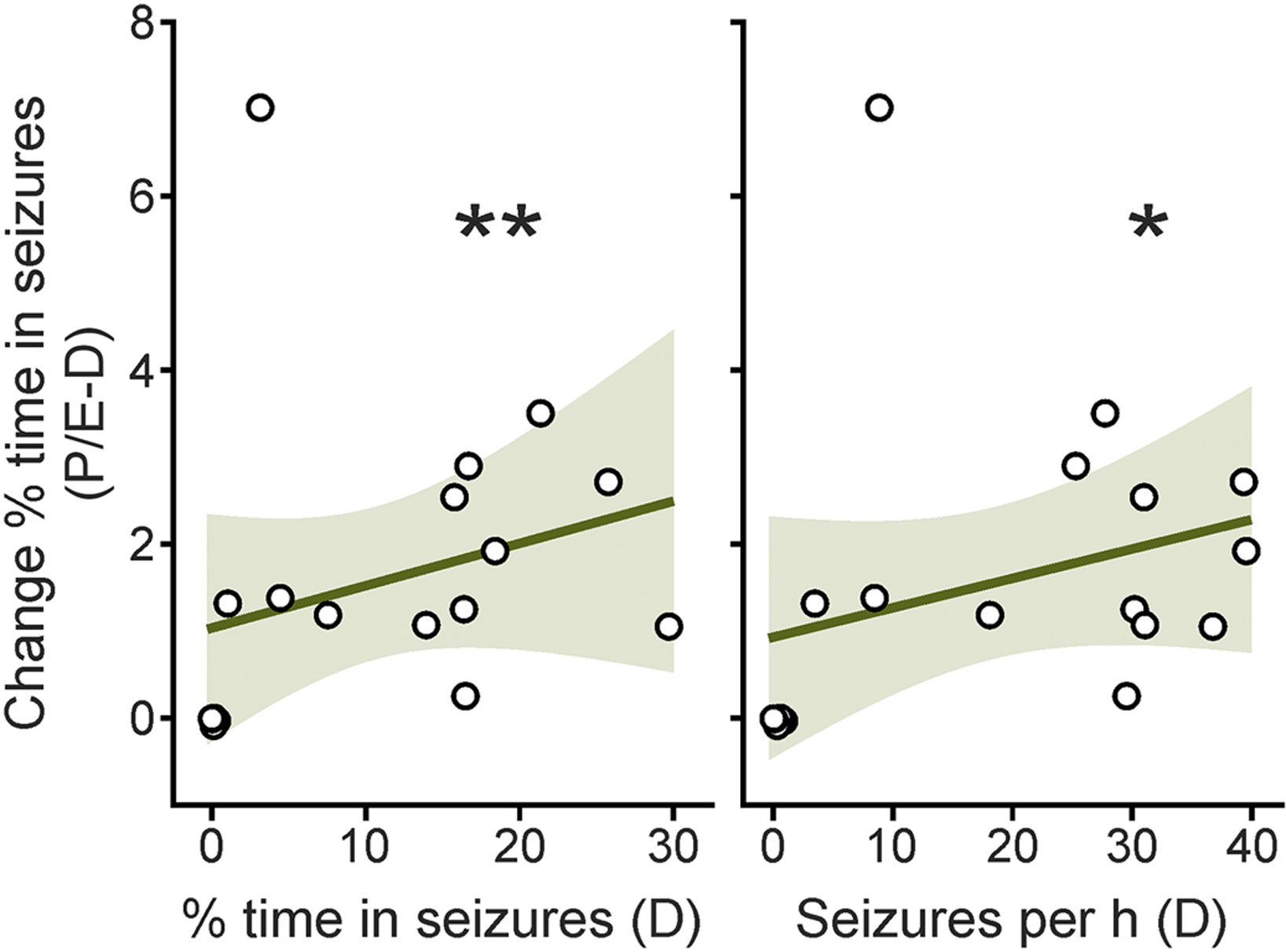

Although most IHKA mice showed a high severity of epilepsy, a wide range of baseline seizure burden was observed, ranging from 0.01–29.7% time spent in seizure activity on diestrus. Therefore, we performed correlation analyses to determine if the degree of estrous cycle-associated changes in EEG parameters correlated with baseline epilepsy severity. Positive correlations in the degree of change in percentage of time spent in seizure activity on pro/estrus compared with diestrus were observed in relation to both the baseline percentage of time spent in seizures on diestrus (r=0.6, p=0.008), and the number of seizures per hour on diestrus (r=0.54, p=0.02) (Figure 4, Table 2), indicating that increased epilepsy severity is associated with a larger degree of estrous cycle-associated changes in time spent in seizures. Comparisons of other EEG parameters did not yield significant correlations (Table 2).

Figure 4:

Cycle-associated changes in percentage of time spent in seizure activity on pro/estrus compared with diestrus in IHKA mice are positively correlated with the baseline percentage of time in seizures (left) and seizures per hour (right) on diestrus. Black circles indicate individual mice (n=18). Dark green lines indicate the linear regression of best fit. Light green shaded areas show the 95% confidence interval of the regression. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, Spearman’s correlations

Table 2:

Summary of Spearman’s correlation statistics examining relationships between values for EEG parameters on diestrus with the degree of change in each parameter on pro/estrus compared with diestrus in IHKA mice.

| EEG parameter (diestrus) | EEG parameter (pro/estrus - diestrus change) | Spearman’s r-value | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| % time in seizures | % time in seizures | 0.6 | .008** |

| Seizures per hour | 0.32 | 0.19 | |

| Seizure duration | −0.3 | 0.26 | |

| Seizures per hour | % time in seizures | 0.54 | 0.022* |

| Seizures per hour | 0.13 | 0.6 | |

| Seizure duration | −0.22 | 0.41 | |

| Seizure duration | % time in seizures | 0.43 | 0.1 |

| Seizures per hour | 0.26 | 0.34 | |

| Seizure duration | −0.34 | 0.2 |

p<0.05,

p<0.01

3.5. Mice that show severe epilepsy characteristic of IHKA model exhibit changes in all measures of seizure burden

Based on the finding that the magnitude of cycle-associated changes in time in seizures depended on the baseline seizure burden on diestrus, we performed paired analyses specifically examining the values obtained from the mice that unambiguously developed the severe epilepsy characteristic of the IHKA model (Twele et al., 2016; Zeidler et al., 2018), defined here as at least 1% time spent in seizure activity on diestrus. When EEG parameters for these mice (n=13) were compared, significant increases in time spent in seizures (D: 14.7 ± 2.4, P/E: 16.8 ± 2.4%; p=0.0007), seizure duration (D: 19.3 ± 1.6, P/E: 21.3 ± 1.3 s; p=0.005), and seizure frequency (D 18.4 ± 3.6, P/E: 19.8 ± 3.7 seizures per hour; p=0.02) were detected (Figure 5). Comparisons within the remaining 5 IHKA mice, which showed much lower seizure burden (0.01–0.33% time in seizures on diestrus), did not show significant differences in percentage of time in seizure activity (D: 0.12 ± 0.06%, P/E: 0.1 ± 0.06%; p>0.16), seizure frequency (D: 0.39 ± 0.16, P/E 0.3 ± 0.17 seizures per hour; p>0.07), nor seizure duration (D: 11.5 ± 1.2, P/E 9.8 ± 1.5 s; p>0.45, n=3 mice as two animals did not exhibit a sufficient number of seizures for comparison of seizure duration).

Figure 5:

Mice with the severe epilepsy typical of the IHKA model (>1% time spent in seizure activity) show prominent pro/estrus vs. diestrus shifts in percentage of time spent in seizures, seizure duration, and seizure frequency. A-C) Boxplots and data distribution for percentage of time spent in seizures (A), seizure duration (B), and seizure frequency (C) on pro/estrus and diestrus. A-C: solid lines = 9 GnRH-Cre:Ai9 mice with right-sided KA injection (9); dashed lines = 2 C57BL/6J mice with right-sided KA injection; dotted lines = 2 C57BL/6J mice with left-sided KA injection. Boxplots indicate data points within 1.5 times the interquartile range, the mean, the median, and 25–75% range. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, paired t-tests

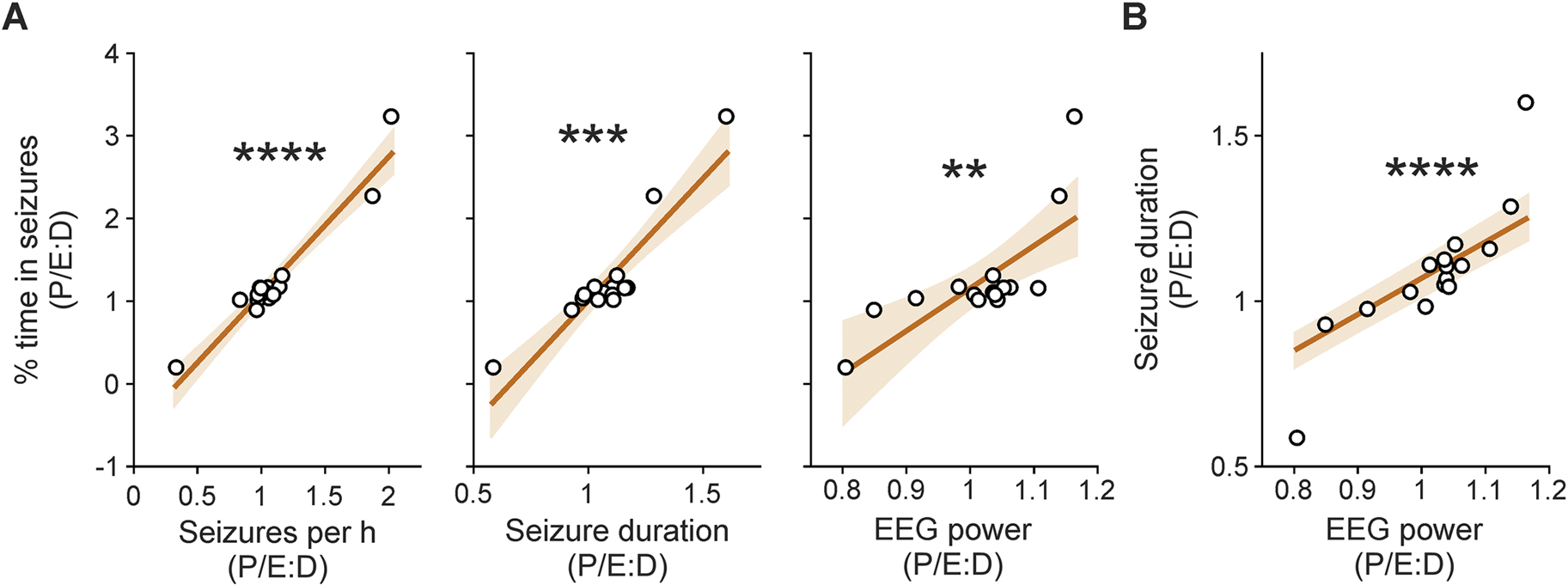

3.6. Within-animal differences in time spent in seizure activity between pro/estrus and diestrus are most strongly correlated with changes in seizure frequency

Fluctuations across estrous cycle stages in time spent in seizures could be driven by changes in seizure frequency and/or duration. To examine the relationships of EEG parameters in promoting within-animal changes between pro/estrus and diestrus, correlation analyses were performed for the pro/estrus:diestrus ratio (P/E:D) of percentage of time in seizures as a function of the P/E:D for seizure frequency, seizure duration, and total EEG power for each individual IHKA mouse. Only mice for which a sufficient number of seizures were detected to enable reliable quantification of seizure duration were included (n=16). There were strong correlations between the change in percentage of time in seizures and the change in seizure frequency (r=0.82, p<0.0001), seizure duration (r=0.74, p=0<0.001), and total EEG power (r=0.68, p=0.03) (Figure 6A). The P/E:D ratios for seizure duration and EEG power were also strongly correlated (r=0.87, p<0.0001) (Figure 6B), but there were no significant relationships between seizure frequency and either duration or EEG power (r=0.4, p=0.12 and r=0.36, p=0.17, respectively).

Figure 6:

Pro/estrus:diestrus ratio (P/E:D) of percentage of time spent in seizure activity is most strongly correlated with P/E:D shifts in seizure frequency. A) Relationship of P/E:D ratio of percentage of time in seizure activity as a function of the P/E:D ratio of seizures per hour (left), seizure duration (middle), and EEG power (right). B) Relationship of P/E:D ratios for seizure duration and EEG power. Black circles indicate individual mice that had a sufficient number of seizures for seizure duration quantification (n=16, including 13 mice with severe epilepsy). Dark orange lines indicate the linear regression of best fit. Light orange shaded areas show the 95% confidence interval of the regression. **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001, Spearman’s correlations

4. Discussion

TLE is strongly linked to catamenial patterns of seizure clustering (Bazan et al., 2005; Quigg et al., 2009). Whether rodent models of TLE show estrous cycle-related changes in seizure burden, and thus could be useful in investigating catamenial-like changes in seizures, remains to be fully understood. This study provides evidence that chronic seizure burden fluctuates with estrous cycle stage in IHKA mice. Specifically, IHKA mice showed more time in seizure activity and longer seizure duration on pro/estrus compared with diestrus. In addition, the degree of change in time in seizures was positively correlated with the baseline seizure burden exhibited on diestrus. As IHKA mice are a model of severe epilepsy (Kim et al., 2020; Twele et al., 2016; Zeidler et al., 2018), this relationship produces distinct shifts in seizure burden across the cohort as a whole. Furthermore, when the IHKA mice with severe epilepsy were examined separately, changes in seizure frequency across the cycle were also detected. In this regard, correlation analyses indicated that the estrous cycle-associated changes in time spent in seizures were most strongly correlated with changes in seizure frequency, although there were also significant relationships with the cycle-dependent changes in seizure duration and EEG power as well.

4.1. Combined proestrus and estrus stages as a time of increased seizure burden in IHKA mice

Because there were no differences detected between proestrus and estrus for any measured seizure parameters, these two stages were combined. Although these are two distinct phases of the estrous cycle and combining the data may mask certain stage-dependent changes, our rationale was based on the following factors. First, these stages are the estradiol-dominant stages in mice. Primarily proconvulsant effects of estradiol have been documented across various rodent models of seizure susceptibility (Edwards et al., 1999; Hom and Buterbaugh, 1986; Woolley, 2000), although some studies have described anticonvulsant effects as well (Kalkbrenner and Standley, 2003; Vathy et al., 1998). In control mice, estradiol strongly peaks at proestrus and drops over the course of estrus (Walmer et al., 1992). Although levels of estradiol in proestrous IHKA mice have yet to be quantified, estrous IHKA mice exhibit higher estradiol levels compared with controls (Li et al., 2018). Second, distinguishing proestrus from estrus is sometimes challenging because a vaginal smear can appear as a mix of these stages (Cora et al., 2015). In addition, vaginal smears may not be fully synchronized with fluctuations in circulating estradiol and progesterone levels (deCatanzaro et al., 2004), and sex steroid effects can occur on both rapid and prolonged timescales, reflecting nongenomic and genomic actions, respectively (Falkenstein et al., 2000). Altogether, combining proestrus and estrus provides a window encompassing an approximation of the late follicular and very early luteal period of the menstrual cycle, a time of increased seizure burden in women with periovulatory catamenial epilepsy (Herzog et al., 1997). Future studies incorporating a longer period of EEG monitoring would be valuable in providing more days in each cycle stage for analyses and allowing for more robust and rigorous determination of the consistency of the observed cycle-associated changes across multiple estrous cycles.

4.2. Potential roles of estradiol and progesterone in driving estrous cycle-associated changes in seizure burden

Although progesterone levels are lower in IHKA mice with disrupted cycles but not in those that maintain regular cyclicity, this pattern is not different on diestrus compared with estrus. Furthermore, although saline-injected controls exhibit estrous cycle-associated shifts in estradiol and progesterone levels, IHKA mice do not (Li et al., 2018). Therefore, it remains unclear to what degree the diestrus vs. pro/estrus differences observed in the present study reflect differences in estradiol feedback vs. effects of progesterone or progesterone-derived metabolites. Although speculative, it is possible that changes in factors such as: expression of estradiol or progesterone nuclear and membrane receptors (Mitterling et al., 2010; Waters et al., 2015); the rate of conversion of progesterone to neurosteroids (Giatti et al., 2019); the sensitivity of GABAA receptors to neurosteroid modulation (Joshi and Kapur, 2019; Reddy et al., 2019); or brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling (Harte-Hargrove et al., 2013) could produce cycle-associated shifts in responses to estradiol and/or progesterone in limbic circuitry in the absence of absolute changes in circulating hormone levels. It should also be noted that the previous hormone data were obtained from separate collections of trunk blood from mice euthanized on diestrus or estrus, which may mask subtle differences that might be discerned by repeatedly measuring estradiol and progesterone at different stages of the cycle within the same animals. Furthermore, many IHKA mice show D and/or P/E stages that persist over several days (Li et al., 2017) (Figures S2–S3), and hormone levels may not remain stable across multiple extended days of a cycle stage as designated by vaginal cytology. Ideally, repeated examination of these hormones in conjunction with simultaneous EEG recordings across the cycle would yield insight into the role of ovarian hormone feedback in driving cycle-associated changes in seizures. Measuring these hormones by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, however, requires approximately 100 μl of blood serum, and mass spectrometry requires similar volumes (Nilsson et al., 2015). Repeated blood sampling of such volumes from a mouse on multiple sequential days is challenging and could be a significant stressor, which can compromise both seizure activity (Joëls, 2009; Maguire and Salpekar, 2013) and the estrous cycle (Breen et al., 2012). Therefore, measurement of blood hormone levels would be limited to a comparison of separate groups of mice euthanized on proestrus, estrus, or diestrus, which would not provide direct insight into within-mouse fluctuations in seizure activity across the cycle. One alternative would be to noninvasively measure urinary or fecal concentrations of estradiol and progesterone, but these concentrations may not precisely reflect those circulating systemically (deCatanzaro et al., 2004).

4.3. Epilepsy severity and degree of estrous cycle disruption do not appear correlated in IHKA mice

On average, IHKA mice in this cohort displayed increased estrous cycle length, recapitulating our previous finding that this phenotype is a prominent feature of estrous cycle disruption in the majority of IHKA female mice, with the remainder maintaining regular estrous cyclicity (Li et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). An observation that IHKA mice with disrupted cycles display differential seizure patterning in association with estrous cycle stage compared with IHKA mice with regular cycles would indicate that this model may at least partially recapitulate a form of catamenial epilepsy in which failure to ovulate, and a resultant inadequate luteal phase, is associated with prolonged seizure exacerbation (Herzog et al., 1997). However, no correlations were detected between the estrous cycle length and any EEG parameters. Furthermore, the cycle-associated patterns of shifts in seizure burden were highly uniform, indicating that the estrous cycle disruption displayed by the majority of IHKA mice did not reciprocally shape the patterning of seizures in relation to estrous cycle stage. It would be interesting to determine whether subtle relationships between seizure patterning and cycle disruption appear as more EEG-recorded IHKA female mice tracked for the estrous cycle are incorporated in future studies across multiple cohorts, enabling more statistically powerful examination. Of note, IHKA mice with disrupted cycles are still able to ovulate, as indicated by the regular appearance of corpora lutea in the ovaries (Li et al., 2017), and estrous cycle disruption in IHKA mice is primarily characterized by increased time in diestrus and prolonged cycle length (Li et al., 2017). Altogether, the lack of correlation between epilepsy severity and degree of estrous cycle disruption indicates that impacts of epilepsy on the estrous cycle likely reflect differential responses manifested at downstream neural and/or pituitary levels in the face of seizure activity. In this regard, in light of our recent findings of changes in GnRH neuron activity on diestrus compared with estrus in IHKA mice (Li et al., 2018), and the evidence supporting functional receptor expression for GnRH and gonadotropins in the hippocampus (Blair et al., 2019; Burnham et al., 2017; Chu et al., 2008; Jennes et al., 1988; Leblanc et al., 1988; Lei and Rao, 2001; Osada and Kimura, 1995; Palovcik and Phillips, 1986; Reubi et al., 1987; Wong et al., 1990), it would be interesting to determine whether GnRH and/or gonadotropin signaling influences the expression of seizures across the estrous cycle.

4.4. EEG tethering transiently disrupts the estrous cycle in control mice

With increased use of the IHKA model of TLE in preclinical studies, an understanding of how the estrous cycle and seizure activity interact in these mice is of increasing importance in interpreting research findings and evaluating the effects of sex as a biological variable (Clayton and Collins, 2014). In our previous study of IHKA mice not implanted with EEG electrodes nor subjected to tethered EEG recording, the phenotype of estrous cycle disruption did not emerge until at least 42 days after KA injection (Li et al., 2017). Female IHKA mice may lack a seizure-free latent period (Twele et al., 2016). Therefore, IHKA females likely develop epilepsy before estrous cycle disruption emerges. Precise evaluation of this time course was precluded here as EEG-recorded control and IHKA mice already displayed long cycles when monitoring commenced at 1 month post-injection. In controls, regular estrous cycles were eventually regained when connected to the EEG a second time. These results emphasize that such disruption to the estrous cycle should be accounted for, and habituation periods provided, when performing similar tethered recordings. Another consideration is that saline/KA injections and EEG electrode implantations were performed in two separate surgeries (Krook-Magnuson et al., 2013), with the first exposure to the tethered EEG environment occurring at least 21 days after intrahippocampal injection. Alternatively, injection and electrode implantation could be performed in the same surgery (Twele et al., 2017; Twele et al., 2016), and EEG tethering introduced earlier to hasten habituation. Wireless telemetric EEG recording systems may also alleviate some of the stress associated with prolonged tethering. Finally, although both control and IHKA mice were subjected to the procedure of daily handling and estrous cycle monitoring, it is possible that at least some IHKA mice may have a stronger stress reaction in response.

4.5. Relevance of fluctuations in seizure burden in IHKA mice to catamenial epilepsy in women

It should be noted that the fluctuations in EEG parameters observed are of smaller magnitude than the ~1.6–1.8-fold exacerbations in seizures typically observed in catamenial epilepsy (Herzog et al., 1997). This difference may reflect, for example: the shorter timescale of the estrous cycle compared to the menstrual cycle; the lack of a true luteal phase in rodents, and thus a reduced accumulation of progesterone-derived neurosteroids and a less precipitous withdrawal at the start of each cycle; differences in underlying mechanisms of cycle-associated shifts in seizure activity in rodents compared with humans; or the much higher baseline frequency of seizures observed in the IHKA model compared with human TLE, which may produce a ceiling effect. As shown in Figure 6, a small number of mice showed large P/E:D shifts in EEG parameters (>1.8-fold) similar to those observed in human catamenial epilepsy, but most mice exhibited changes in the 1.1–1.2-fold range, with some mice not showing cycle-associated differences or showing slight P/E:D decreases in seizure burden. We propose that this variability should be viewed as a strength of the IHKA model rather than a weakness, in that it recapitulates the clinical context in which only some women with TLE exhibit catamenial patterns of seizure clustering, and the timing and degree of seizure exacerbation in relation to the cycle vary among patients as well. Comparisons of IHKA mice that show cycle-associated fluctuations with those that do not should thus provide a useful model for mechanistic studies to elucidate changes specifically linked with seizure patterns that are influenced by the female reproductive cycle. The variability in baseline epilepsy severity also underscores the importance of chronic studies that examine seizure activity within the same animals across different estrous cycle stages, as subtle differences in seizure parameters revealed in within-animal examinations may be masked in experiments in which separate groups of mice are tested at different cycle stages. In this regard, although recent meta-analyses denote a lack of major differences associated with the estrous cycle in mice and rats with regard to diverse physiological and behavioral traits, and indicate that female rodents are not inherently more variable than males (Becker et al., 2016; Beery, 2018; Prendergast et al., 2014), the condition of chronic epilepsy may increase biological variability and reveal latent cycle-associated changes.

4.6. Concluding remarks

In summary, these studies provide evidence for endogenous shifts in seizure burden in association with estrous cycle stage in the IHKA mouse model of TLE. In particular, the stages of proestrus and estrus are associated with higher seizure burden than diestrus. Although further studies are needed to understand the neurobiological and endocrine bases of these fluctuations, these shifts in seizure burden occurred in the absence of exogenous hormone treatment or other pharmacological manipulations. In this regard, it should be noted that despite decades of both basic and clinical research demonstrating hormonal regulation of seizures (Christian et al., 2020), studies illustrating the influence of endogenous hormones and changes across the reproductive cycle are rare in experimental animals. Although the present study is limited in that EEG data were available for only 1–2 estrous cycles per mouse, it underscores the power of examining the same animals across multiple cycle stages, and provides a foundation for future research to examine the degree to which the IHKA model recapitulates at least some aspects of seizure clustering associated with the female reproductive cycle.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Convolutional neural network machine learning method detects seizures in mice

IHKA female mice show increased seizure burden on proestrus and estrus

Higher seizure burden on diestrus correlated with larger cycle-associated differences

IHKA mouse model may be useful in modeling catamenial-like seizure exacerbation

Acknowledgments

We thank Esther Krook-Magnuson for helpful discussions on EEG recordings, and Cathryn Cutia, Robbie Ingram, Lola Lozano, and Rana Youssef for assistance with estrous cycle monitoring.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke grants R01 NS105825 and R03 NS103029 (C.A.C.-H.).

Abbreviations

- CNN

convolutional neural network

- EEG

electroencephalogram

- GnRH

gonadotropin-releasing hormone

- IHKA

intrahippocampal kainic acid

- KA

kainic acid

- TLE

temporal lobe epilepsy

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Armstrong C, Krook-Magnuson E, Oijala M, Soltesz I, 2013. Closed-loop optogenetic intervention in mice. Nat Protoc 8, 1475–1493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazan AC, Montenegro MA, Cendes F, Min LL, Guerreiro CA, 2005. Menstrual cycle worsening of epileptic seizures in women with symptomatic focal epilepsy. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 63, 751–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker JB, Prendergast BJ, Liang JW, 2016. Female rats are not more variable than male rats: a meta-analysis of neuroscience studies. Biol Sex Differ 7, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beery AK, 2018. Inclusion of females does not increase variability in rodent research studies. Curr Opin Behav Sci 23, 143–149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair JA, Bhatta S, Casadesus G, 2019. CNS luteinizing hormone receptor activation rescues ovariectomy-related loss of spatial memory and neuronal plasticity. Neurobiol Aging 78, 111–120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouilleret V, Ridoux V, Depaulis A, Marescaux C, Nehlig A, Le Gal La Salle G, 1999. Recurrent seizures and hippocampal sclerosis following intrahippocampal kainate injection in adult mice: electroencephalography, histopathology and synaptic reorganization similar to mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 89, 717–729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt C, Bankstahl M, Tollner K, Klee R, Loscher W, 2016. The pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy: Marked intrastrain differences in female Sprague-Dawley rats and the effect of estrous cycle. Epilepsy Behav 61, 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen KM, Thackray VG, Hsu T, Mak-McCully RA, Coss D, Mellon PL, 2012. Stress levels of glucocorticoids inhibit LHbeta-subunit gene expression in gonadotrope cells. Mol Endocrinol 26, 1716–1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnham V, Sundby C, Laman-Maharg A, Thornton J, 2017. Luteinizing hormone acts at the hippocampus to dampen spatial memory. Horm Behav 89, 55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byers SL, Wiles MV, Dunn SL, Taft RA, 2012. Mouse estrous cycle identification tool and images. PLoS One 7, e35538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christian CA, Reddy DS, Maguire J, Forcelli PA, 2020. Sex Differences in the Epilepsies and Associated Comorbidities: Implications for Use and Development of Pharmacotherapies. Pharmacol Rev 72, 767–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C, Gao G, Huang W, 2008. A study on co-localization of FSH and its receptor in rat hippocampus. J Mol Histol 39, 49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton JA, Collins FS, 2014. Policy: NIH to balance sex in cell and animal studies. Nature 509, 282–283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cora MC, Kooistra L, Travlos G, 2015. Vaginal Cytology of the Laboratory Rat and Mouse: Review and Criteria for the Staging of the Estrous Cycle Using Stained Vaginal Smears. Toxicol Pathol 43, 776–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Amour J, Magagna-Poveda A, Moretto J, Friedman D, LaFrancois JJ, Pearce P, Fenton AA, MacLusky NJ, Scharfman HE, 2015. Interictal spike frequency varies with ovarian cycle stage in a rat model of epilepsy. Exp Neurol 269, 102–119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deCatanzaro D, Muir C, Beaton EA, Jetha M, 2004. Non-invasive repeated measurement of urinary progesterone, 17β-estradiol, and testosterone in developing, cycling, pregnant, and postpartum female mice. Steroids 69, 687–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desloovere J, Boon P, Larsen LE, Merckx C, Goossens MG, Van den Haute C, Baekelandt V, De Bundel D, Carrette E, Delbeke J, Meurs A, Vonck K, Wadman W, Raedt R, 2019. Long-term chemogenetic suppression of spontaneous seizures in a mouse model for temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 60, 2314–2324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards HE, Burnham WM, Mendonca A, Bowlby DA, MacLusky NJ, 1999. Steroid hormones affect limbic afterdischarge thresholds and kindling rates in adult female rats. Brain Res 838, 136–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M, 2000. Multiple actions of steroid hormones--a focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev 52, 513–556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finn DA, Gee KW, 1994. The estrus cycle, sensitivity to convulsants and the anticonvulsant effect of a neuroactive steroid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 271, 164–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangisetty O, Reddy DS, 2010. Neurosteroid withdrawal regulates GABA-A receptor alpha4-subunit expression and seizure susceptibility by activation of progesterone receptor-independent early growth response factor-3 pathway. Neuroscience 170, 865–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giatti S, Garcia-Segura LM, Barreto GE, Melcangi RC, 2019. Neuroactive steroids, neurosteroidogenesis and sex. Prog Neurobiol 176, 1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harte-Hargrove LC, Maclusky NJ, Scharfman HE, 2013. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-estrogen interactions in the hippocampal mossy fiber pathway: implications for normal brain function and disease. Neuroscience 239, 46–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AG, Klein P, Rand BJ, 1997. Three patterns of catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsia 38, 1082–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hom AC, Buterbaugh GG, 1986. Estrogen alters the acquisition of seizures kindled by repeated amygdala stimulation or pentylenetetrazol administration in ovariectomized female rats. Epilepsia 27, 103–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard JA, Szu JI, Yonan JM, Binder DK, 2016. Regulation of astrocyte glutamate transporter-1 (GLT1) and aquaporin-4 (AQP4) expression in a model of epilepsy. Exp Neurol 283, 85–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jennes L, Dalati B, Conn PM, 1988. Distribution of gonadrotropin releasing hormone agonist binding sites in the rat central nervous system. Brain Res 452, 156–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joëls M, 2009. Stress, the hippocampus, and epilepsy. Epilepsia 50, 586–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Kapur J, 2019. Neurosteroid regulation of GABA(A) receptors: A role in catamenial epilepsy. Brain Res 1703, 31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalkbrenner KA, Standley CA, 2003. Estrogen modulation of NMDA-induced seizures in ovariectomized and non-ovariectomized rats. Brain Res 964, 244–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilias A, Haussler U, Heining K, Froriep UP, Haas CA, Egert U, 2018. Theta frequency decreases throughout the hippocampal formation in a focal epilepsy model. Hippocampus 28, 375–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Gschwind T, Nguyen TM, Bui AD, Felong S, Ampig K, Suh D, Ciernia AV, Wood MA, Soltesz I, 2020. Optogenetic intervention of seizures improves spatial memory in a mouse model of chronic temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia 61, 561–571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krook-Magnuson E, Armstrong C, Oijala M, Soltesz I, 2013. On-demand optogenetic control of spontaneous seizures in temporal lobe epilepsy. Nat Commun 4, 1376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laidlaw J, 1956. Catamenial epilepsy. Lancet 271, 1235–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leblanc P, Crumeyrolle M, Latouche J, Jordan D, Fillion G, L’Heritier A, Kordon C, Dussaillant M, Rostene W, Haour F, 1988. Characterization and distribution of receptors for gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the rat hippocampus. Neuroendocrinology 48, 482–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei ZM, Rao CV, 2001. Neural actions of luteinizing hormone and human chorionic gonadotropin. Semin Reprod Med 19, 103–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque M, Avoli M, 2013. The kainic acid model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 37, 2887–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Kim JS, Abejuela VA, Lamano JB, Klein NJ, Christian CA, 2017. Disrupted female estrous cyclicity in the intrahippocampal kainic acid mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsia Open 2, 39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Robare JA, Gao L, Ghane MA, Flaws JA, Nelson ME, Christian CA, 2018. Dynamic and Sex-Specific Changes in Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Neuron Activity and Excitability in a Mouse Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. eNeuro 5, e0273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire J, Salpekar JA, 2013. Stress, seizures, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis targets for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 26, 352–362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maguire JL, Stell BM, Rafizadeh M, Mody I, 2005. Ovarian cycle-linked changes in GABA(A) receptors mediating tonic inhibition alter seizure susceptibility and anxiety. Nat Neurosci 8, 797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitterling KL, Spencer JL, Dziedzic N, Shenoy S, McCarthy K, Waters EM, McEwen BS, Milner TA, 2010. Cellular and subcellular localization of estrogen and progestin receptor immunoreactivities in the mouse hippocampus. J Comp Neurol 518, 2729–2743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy BL, Hofacer RD, Faulkner CN, Loepke AW, Danzer SC, 2012. Abnormalities of granule cell dendritic structure are a prominent feature of the intrahippocampal kainic acid model of epilepsy despite reduced postinjury neurogenesis. Epilepsia 53, 908–921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson JF, Felicio LS, Osterburg HH, Finch CE, 1981. Altered profiles of estradiol and progesterone associated with prolonged estrous cycles and persistent vaginal cornification in aging C578L/6J mice. Biol Reprod 24, 784–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newmark ME, Penry JK, 1980. Catamenial epilepsy: a review. Epilepsia 21, 281–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson ME, Vandenput L, Tivesten A, Norlen AK, Lagerquist MK, Windahl SH, Borjesson AE, Farman HH, Poutanen M, Benrick A, Maliqueo M, Stener-Victorin E, Ryberg H, Ohlsson C, 2015. Measurement of a Comprehensive Sex Steroid Profile in Rodent Serum by High-Sensitive Gas Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Endocrinology 156, 2492–2502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osada T, Kimura F, 1995. LHRH effects on hippocampal neurons are modulated by estrogen in rats. Endocr J 42, 251–257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palovcik RA, Phillips MI, 1986. A biphasic excitatory response of hippocampal neurons to gonadotropin-releasing hormone. Neuroendocrinology 44, 137–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantier LK, Li J, Christian CA, 2019. Estrous Cycle Monitoring in Mice with Rapid Data Visualization and Analysis. Bio Protoc 9, e3354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prendergast BJ, Onishi KG, Zucker I, 2014. Female mice liberated for inclusion in neuroscience and biomedical research. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 40, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigg M, Smithson SD, Fowler KM, Sursal T, Herzog AG, 2009. Laterality and location influence catamenial seizure expression in women with partial epilepsy. Neurology 73, 223–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, 2009. The role of neurosteroids in the pathophysiology and treatment of catamenial epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 85, 1–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Carver CM, Clossen B, Wu X, 2019. Extrasynaptic γ-aminobutyric acid type A receptor-mediated sex differences in the antiseizure activity of neurosteroids in status epilepticus and complex partial seizures. Epilepsia 60, 730–743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy DS, Gould J, Gangisetty O, 2012. A mouse kindling model of perimenstrual catamenial epilepsy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 341, 784–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reubi JC, Palacios JM, Maurer R, 1987. Specific luteinizing-hormone-releasing hormone receptor binding sites in hippocampus and pituitary: an autoradiographical study. Neuroscience 21, 847–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riazi K, Honar H, Homayoun H, Rashidi N, Dehghani M, Sadeghipour H, Gaskari SA, Dehpour AR, 2004. Sex and estrus cycle differences in the modulatory effects of morphine on seizure susceptibility in mice. Epilepsia 45, 1035–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riban V, Bouilleret V, Pham-Le BT, Fritschy JM, Marescaux C, Depaulis A, 2002. Evolution of hippocampal epileptic activity during the development of hippocampal sclerosis in a mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Neuroscience 112, 101–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos VR, Kobayashi I, Hammack R, Danko G, Forcelli PA, 2018. Impact of strain, sex, and estrous cycle on gamma butyrolactone-evoked absence seizures in rats. Epilepsy Res 147, 62–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Goodman JH, Rigoulot MA, Berger RE, Walling SG, Mercurio TC, Stormes K, Maclusky NJ, 2005. Seizure susceptibility in intact and ovariectomized female rats treated with the convulsant pilocarpine. Exp Neurol 196, 73–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharfman HE, Mercurio TC, Goodman JH, Wilson MA, MacLusky NJ, 2003. Hippocampal excitability increases during the estrous cycle in the rat: a potential role for brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurosci 23, 11641–11652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twele F, Schidlitzki A, Tollner K, Loscher W, 2017. The intrahippocampal kainate mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy: Lack of electrographic seizure-like events in sham controls. Epilepsia Open 2, 180–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twele F, Tollner K, Brandt C, Loscher W, 2016. Significant effects of sex, strain, and anesthesia in the intrahippocampal kainate mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 55, 47–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Luijtelaar G, Budziszewska B, Jaworska-Feil L, Ellis J, Coenen A, Lason W, 2001. The ovarian hormones and absence epilepsy: a long-term EEG study and pharmacological effects in a genetic absence epilepsy model. Epilepsy Res 46, 225–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vathy I, Veliskova J, Moshe SL, 1998. Prenatal morphine exposure induces age-related changes in seizure susceptibility in male rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 60, 635–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walmer DK, Wrona MA, Hughes CL, Nelson KG, 1992. Lactoferrin expression in the mouse reproductive tract during the natural estrous cycle: correlation with circulating estradiol and progesterone. Endocrinology 131, 1458–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters EM, Thompson LI, Patel P, Gonzales AD, Ye HZ, Filardo EJ, Clegg DJ, Gorecka J, Akama KT, McEwen BS, Milner TA, 2015. G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1 is anatomically positioned to modulate synaptic plasticity in the mouse hippocampus. J Neurosci 35, 2384–2397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JC, Makinson CD, Lamar T, Cheng Q, Wingard JC, Terwilliger EF, Escayg A, 2018. Selective targeting of Scn8a prevents seizure development in a mouse model of mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. Sci Rep 8, 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M, Eaton MJ, Moss RL, 1990. Electrophysiological actions of luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone: intracellular studies in the rat hippocampal slice preparation. Synapse 5, 65–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley CS, 2000. Estradiol facilitates kainic acid-induced, but not flurothyl-induced, behavioral seizure activity in adult female rats. Epilepsia 41, 510–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidler Z, Brandt-Fontaine M, Leintz C, Krook-Magnuson C, Netoff T, Krook-Magnuson E, 2018. Targeting the Mouse Ventral Hippocampus in the Intrahippocampal Kainic Acid Model of Temporal Lobe Epilepsy. eNeuro 5, ENEURO.0158–0118.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.