Abstract

Touch, hearing, and blood pressure regulation require mechanically gated ion channels that convert mechanical stimuli into electrical currents. One such channel is Piezo1, which plays a key role in the transduction of mechanical stimuli in humans and is implicated in diseases, such as xerocytosis and lymphatic dysplasia. There is building evidence that suggests Piezo1 can be regulated by the membrane environment, with the activity of the channel determined by the local concentration of lipids, such as cholesterol and phosphoinositides. To better understand the interaction of Piezo1 with its environment, we conduct simulations of the protein in a complex mammalian bilayer containing more than 60 different lipid types together with electrophysiology and mutagenesis experiments. We find that the protein alters its local membrane composition, enriching specific lipids and forming essential binding sites for phosphoinositides and cholesterol that are functionally relevant and often related to Piezo1-mediated pathologies. We also identify a number of key structural connections between the propeller and pore domains located close to lipid-binding sites.

Significance

The perception and interpretation of mechanical forces is involved in senses, such as touch and hearing, as well as regulating cell volume and blood pressure. Piezo1 is an ion channel that plays a key role in the sensation of these mechanical forces in humans. Mutations in Piezo1 are implicated in many diseases, including xerocytosis and generalized lymphatic dysplasia. It has been shown that the membrane environment can regulate Piezo1, but it is unclear how this occurs. We show that Piezo1 forms specific, long-lasting interactions with a number of lipid types in the cell membrane and that these are critical to the proper function of the protein. This helps us understand how mutations at these disparate sites can have pathological consequences.

Introduction

Piezo1 is a long-sought-after molecular force sensor in eukaryotes (1). This nonselective cation channel is ubiquitously expressed and is responsible for primary mechanosensitive currents in a myriad of cells and tissues (2,3). Its presence in mammals is essential, exemplified by the embryonic lethality of its global deletion in mice (4,5). Piezo1 dysfunction is likely involved in both multifactorial diseases, including migraine and pain (6,7), in addition to hereditary conditions. For example, Piezo1 gene variants have been definitively linked to hereditary xerocytosis (gain of function (8,9) and generalized lymphatic dysplasia (loss of function (10)). In all likelihood, this list of known pathologies will grow given the broad expression pattern of Piezo1. The gain-of-function Piezo1 phenotype, identified by its impact on red blood cell morphology, has been linked to a loss of channel inactivation (11), as well as increased channel sensitivity to mechanical force (12). The net result in all these mutations is increased Ca2+ flux and eventual red blood cell dehydration. The loss-of-function phenotype is presumably due to a portion of variants not reaching the membrane (e.g., G2029R (10)) and a proportion that are less sensitive to applied force.

Although lipids are of critical importance to all membrane-embedded proteins (13, 14, 15), they hold particular significance for mechanically gated ion channels (16, 17, 18, 19, 20). This is because in many cases, such as the prototypical bacterial channels (21,22), mechanically gated channels can sense forces directly from the membrane (23, 24, 25, 26). Akin to the bacterial mechanically gated channels (21,22), Piezo1 has been shown to function in “reduced systems,” such as reconstituted bilayers (27,28). This suggests that the channel is not completely reliant on direct cytoskeletal connections. This in no way precludes a role for the cytoskeleton in Piezo1 function (29, 30, 31, 32) because membrane forces are largely determined by the local arrangement of the cytoskeleton and extracellular matrix (33, 34, 35). However, these experiments highlight that lipids are of critical importance to Piezo1.

Cryo-EM structures of the trimeric assembly of mouse Piezo1 (mPiezo1) from three separate groups show a triskelion arrangement and a peculiar cup-shaped topology (36, 37, 38). The long arms (“propellers”) of each monomer extend out and curve toward the extracellular space, with a long helix termed the “beam” running almost parallel to the intracellular side of the propeller (Fig. 1). The propellers converge on a central pore region created by the last two transmembrane helices in the C-terminus, which sits under a conserved cap domain important for inactivation (39). The propellers are separated from the pore by an “anchor domain” that forms a triangle and consists of two elbows and a helix that sits parallel at the membrane interface. In a simplified liposomal system, the channel itself seems to locally deform the membrane, retaining the cup shape seen in the cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) protein structures (36), something also seen during Piezo1 simulations in simple bilayers (40).

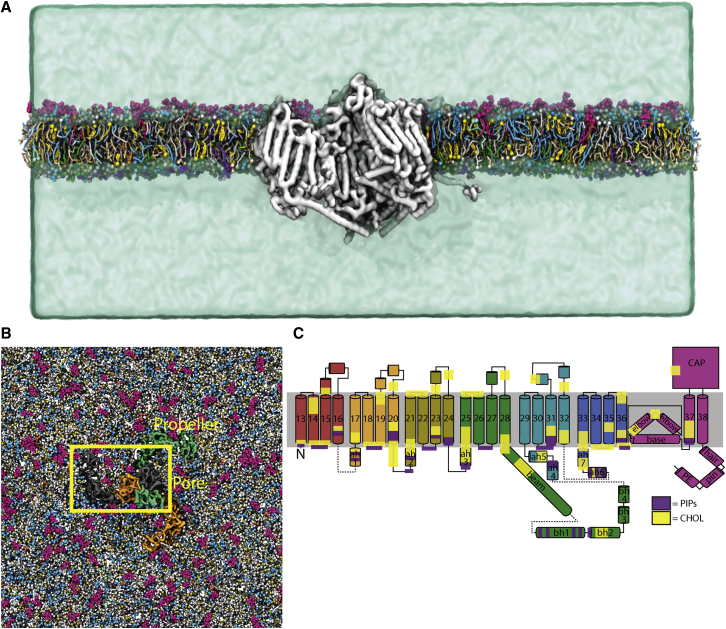

Figure 1.

Simulation setup and Piezo1 structure. Shown is the initial system setup as viewed from (A) the side of the bilayer and (B) from the extracellular side of the membrane. In (A), Piezo1 is shown by the gray surface, whereas each different lipid type is shown in different colors, and water is shown as a green surface. Ions are omitted for clarity. In the top down view, each protein chain colored differently. The box highlights one protein subunit as represented in (C). Only the central part of the simulation system is shown. (C) Shown is the topology of a single subunit of the truncated construct, with each part of the secondary structure labeled. Helices 1–12 are absent in this protein model. ah6 is a computationally predicted amphipathic helix. The location of predicted PIP- and CHOL-binding sites are highlighted by purple and yellow regions, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

Functional data point to a role for various lipids in mechanical gating of Piezo1. For example, methyl-β-cyclodextrin, a drug commonly used to deplete cholesterol, had a minor influence on Piezo1 clustering (41), reduced mechanically induced Piezo1 currents in response to cell indentation (42), and increased the pressure required to open the channel in cell-attached patch clamping (41). Depletion of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) via activation of TRPV1 inhibits Piezo1 activity (43). Although a specific PIP2-binding region was identified on Piezo2, with depletion of PIP2 also leading to channel inhibition, this specific structural region was not conserved in Piezo1 (44). The presence of phosphatidylserine (PS) or lysophosphatidylserine in the outer leaflet inhibits Piezo1-mediated Ca2+ entry. The PS presence is due to the scramblase TMEM16F, which, when activated by Ca2+, flips PS into the outer leaflet and acts as a negative feedback loop for Piezo1 activity (45). Piezo1 activity seems to depend on asymmetry within the membrane, with spontaneous activity observed in asymmetric bilayers containing dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidic acid or lysophosphatidic acid in the inner leaflet, but not in symmetric bilayers (28,46). However, exactly how and where different lipids interact with Piezo1 to regulate channel activity is yet to be carefully explored.

Here, we use coarse-grained molecular dynamics (CG-MD) simulations of Piezo1 in complex asymmetric bilayers to understand how different lipid types interact with the protein. By finding residues that form long-lasting interactions with specific lipid types, we identify potential lipid-binding sites. Electrophysiological studies on mutations at these sites shows that some appear to be functionally important and that this may be due to altering lipid binding to the protein.

Methods

Molecular dynamics simulations

Structural modeling

The structure of mPiezo1 (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 6B3R (36)) was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org) (47). Because some of the smaller loops were not resolved, these were built in using the program MODELER (48). Any large unstructured loops were not modeled. In addition, the sequence of the unresolved loops of mPiezo1 was run through PsiPred (http://bioinf.cs.ucl.ac.uk/psipred/). This determined that there is likely another amphipathic region before helix 33 in addition to the structurally resolved amphipathic helix. This helix was modeled into both structures using MODELER (48). The final structure was chosen from the best of five models generated using MODELER (48). The mPiezo1 model starts from L577 and omits the following large extracellular loops: E718-D781, R1366-S1492, S1579-I1656, and A1808-V1904. The model lacking the propeller domains starts from M1905 (mouse numbering). For all simulation figures, the mouse sequence numbering has been converted to human numbering for ease of comparison with the experimental data on human Piezo1.

Simulation setup

GROMACS2018.1 (49) was used for the setup and execution simulations, with the Martini 2.2 force field (50,51) being used for all simulations. The model used for these simulations was an mPiezo1 model based on the structure solved by Guo and Mackinnon (36). This model was one that was deemed the “best” of the five models in that it had no loops overlapping, had the best DOPE score, and constructed the best representation of the α-helices. All simulations were run at 310 K, with a van der Waals radius of 1.1 nm and a timestep of 20 fs (52). The NPT simulations used a Berendsen (53) thermostat, with semiisotropic pressure coupling and the pressure set to 1 atm using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat. A straight cutoff Lenard-Jones potential with potential modifiers, as well as a Verlet neighbor search algorithm (52,54), was used in GROMACS (55) to calculate electrostatics.

Simulations were set up using the MARTINATE script, which is available on Github (https://github.com/Tsjerk/gromit). The initial homology model was coarse grained using martinize (http://cgmartini.nl/index.php/tools2/proteins-and-bilayers), with an elastic network cutoff of 0.6 nm. The elastic network was initially built using ElNeDyn (56), and extraneous elastic network bonds were removed using domELNEDIN (57). The protein was then embedded into a realistic mammalian membrane model using INSANE (58) (see Table S1 for the exact lipid composition), solvated with coarse-grain waters, neutralized, and ionized with 0.15 M NaCl. The size of the Piezo1 system is 60 × 60 × 25 nm, which totals ∼710,000 coarse-grain particles. The system was then energy minimized using the steepest descent method for 5000 steps. After this initial minimization, position-restrained NVT was run for 1 ps to remove possible high-energy interactions. For the position-restrained NVT simulations, they were run for 5000 steps, with isotropic pressure at 1 atm and a timestep of 2 fs. After this, three position-restrained NPT equilibration steps were run for 5000 steps each, with 5-, 10-, and 20-fs timesteps, respectively, with a Berendsen barostat (53) and a pressure of 1 atm. Next, two initial NPT simulations were run for 1 ps each, with a 20-fs timestep, again with a Berendsen barostat (53) and a pressure of 1 atm. Finally, production runs were conducted for 30 μs in total. To allow the systems to equilibrate, all analysis was done using the last 10 μs.

For the mutation simulations, specifically R808Q and K2097E, the last frame of the first replicate of the wild-type (WT) simulation was manually mutated. Because the mutations R808Q and K2097E involve removing one coarse-grain side chain bead, we manually deleted this bead and changed the name of the side chain. We then re-neutralized this structure and simulated each system for 10 μs. For the Δ4K simulation, a new model was created using the Piezo1 structure as a template but was built without K2166-K2169. This was simulated for 30 μs, with the last 10 μs of the simulation used for subsequent analysis.

Simulation analysis

Radial distribution functions were analyzed using gmx rdf in GROMACS2018.1 (49). Contact maps were calculated using in-house Python and gnuplot scripts. Depletion/Enrichment Indices were calculated using an updated version of the script used in (59) and is available on the Martini website (cgmartini.nl). The Depletement/Enrichment Index (DEI) is calculated as follows:

| (1) |

where

| (2) |

and

| (3) |

Thickness and density maps were calculated using modified versions of g_density and g_thickness (60) (available for download from http://perso.ibcp.fr/luca.monticelli/tools/index.html) and compiled using GROMACS4.5.6 (61). Visualization was done using visual molecular dynamics (62).

Electrophysiology

Transiently transfected P1 KO HEK293T cells were plated on 35-mm dishes for patch-clamp analysis. The extracellular solution for cell-attached patches contained high K+ to zero the membrane potential and consisted 90 mM potassium aspartate, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2 and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) adjusted using KOH. The pipette solution contained either 145 mM CsCl or 145 mM NaCl with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2) adjusted using the respective hydroxide. EGTA was added to control levels of free pipette (extracellular) Ca2+ using an available online EGTA calculator—Ca-EGTA Calculator TS v1.3—Maxchelator. Negative pressure was applied to patch pipettes using a High Speed Pressure Clamp-1 (ALA Scientific Instruments, Farmingdale, NY) and recorded in millimeters of mercury (mmHgs) using a piezoelectric pressure transducer (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL). Borosilicate glass pipettes (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) were pulled using a vertical pipette puller (PP-83; Narishige Scientific Instrument Lab, Tokyo, Japan) to produce electrodes with a resistance of 1.8–2.2 MΩ. Single-channel PIEZO1 currents were amplified using an AxoPatch 200B amplifier (Axon Instruments Molecular Devices, San Jose, CA), and data were acquired at a sampling rate of 10 kHz with 1-kHz filtration and analyzed using pCLAMP10 software (Axon Instruments Molecular Devices). Boltzmann distribution functions describe the dependence of the mesoscopic PIEZO1 channel currents and open probability, respectively, on the negative pressure applied to patch pipettes. The Boltzmann plots were obtained by fitting open probability Po∼I/Imax versus negative pressure using the expression Po/(1 − Po) = exp[α(P − P1/2)], where P is the negative pressure (suction) [mmHgs], P1/2 is the negative pressure at which Po = 0.5, and α [mmHgs−1] is the slope of the plot ln [Po/(1 − Po) = [α(P − P1/2)], reflecting the channel mechanosensitivity. Kinetic analysis was performed using Clampfit on records with a deadtime of 0.4 ms, idealized by the half-amplitude threshold method under the application of 10 mmHg. The resulting dwell time data were fitted with a one-component probability density function.

Cell culture

hPiezo1 KO HEK293T cells were a kind gift from Ardem Patapoutian and cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum.

Results

The lipid fingerprint of Piezo1

To probe the local interactions of Piezo1 with surrounding lipids, we made use of CG-MD simulations, an efficient tool to study the molecular details of protein-lipid interactions (63). To closely mimic the composition of mammalian membranes, we simulated Piezo1 inside a complex asymmetric in silico bilayer containing more than 60 different lipid types (Fig. 1 A; Table S1; (64)), allowing us to see which of these localize to specific sites on the protein. We conducted three 30-μs replicate simulations of a WT, truncated construct of Piezo1, based on the portion of the protein resolved in the cryo-EM structure of Guo and Mackinnon (36). This construct includes six of the nine four-helical repeats that make up the propellers, starting from residue L577, and contains all regions of the protein resolved in the recent cryo-EM structures (36,37,65) (pore, cap, and beam domains and most of the propellers; see Fig. 1 B). Although omitting the ends of the propellers may alter the overall curvature of the membrane around the protein, we believe it should not influence specific lipid-protein interactions in the central portion of the protein.

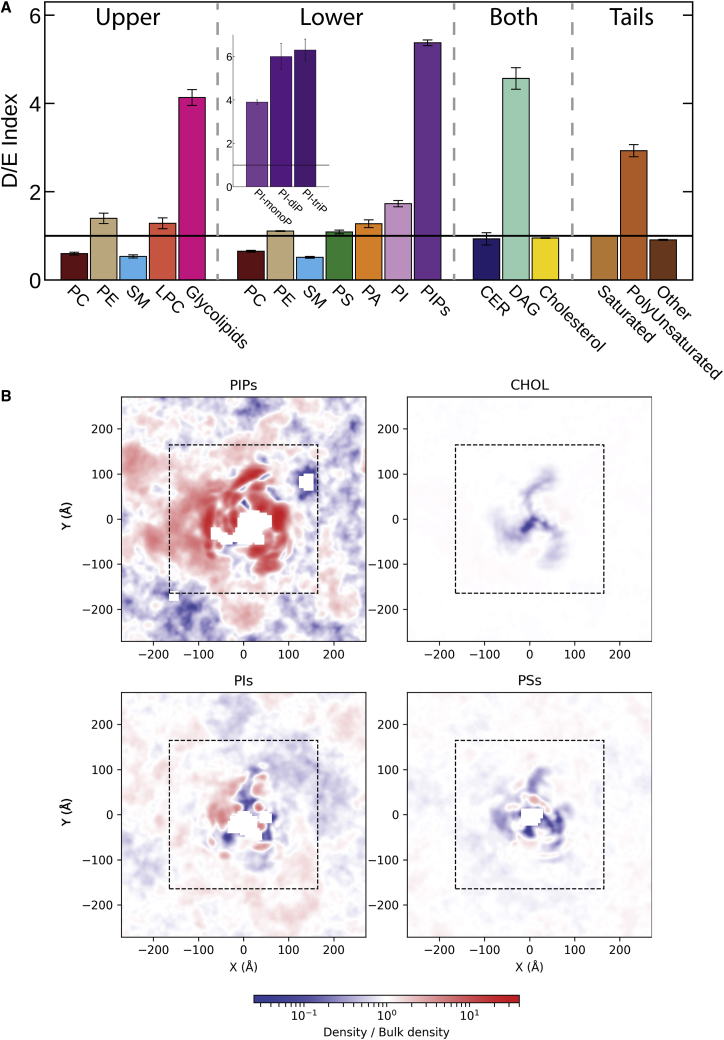

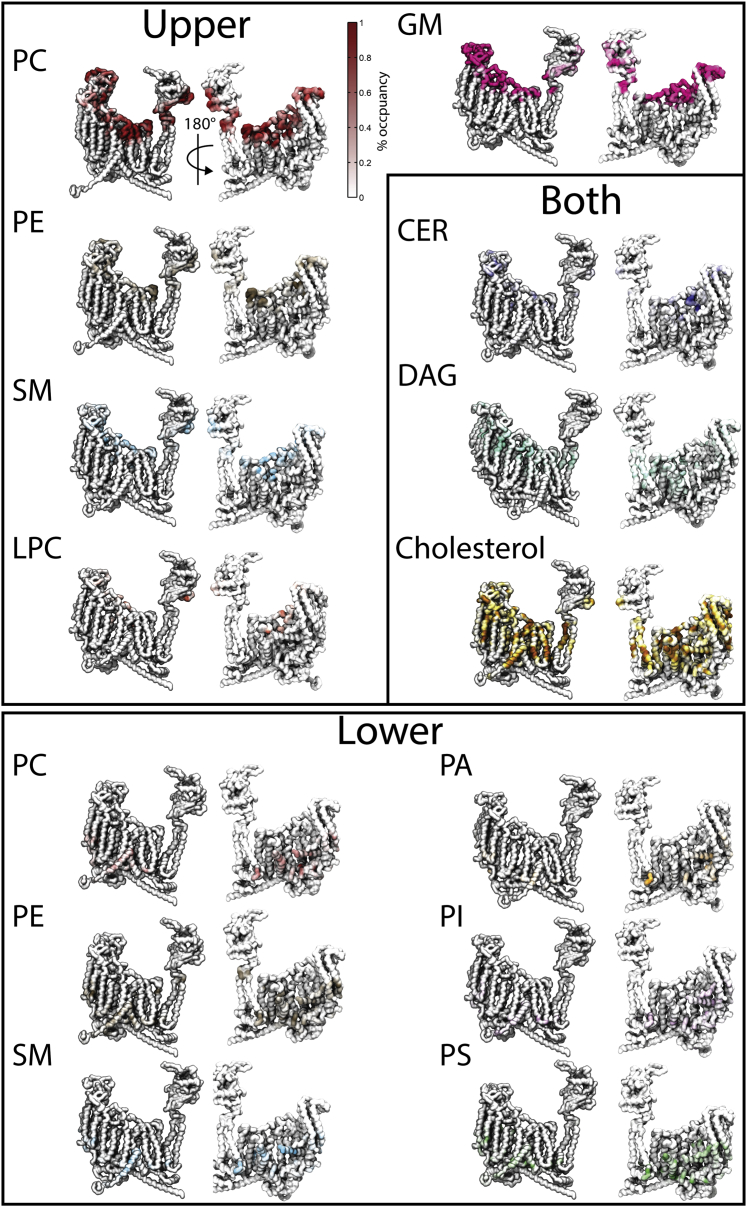

The CG-MD simulations reveal membrane curvature around the protein (to be examined in future work) and enrichment and depletion of specific lipids around the protein, suggesting a clear preference for the protein to interact with some lipids over others (denoted lipid fingerprints (59)). Some lipid types are highly enriched around the protein, in particular, glycolipids, phosphatidylinositol phosphates (PIPs), and diacylglycerols (DAGs), whereas some lipids, most notably sphingomyelin, are strongly depleted. This can be inferred from the D/E index calculated for each lipid group for each leaflet (Fig. 2 A), as well as by density plots of specific lipids around the protein (Fig. 2 B) and maps of the residues that most frequently interact with each lipid type (Fig. 3). As seen in Figs. 2 B and 3, a large number of lipids, including PSs, phosphatidic acids (PAs), sphingomyelin, phosphatidylethanolamines, PIPs, phosphatidylinositols (PIs), and cholesterol bind at specific sites on the protein. This includes some lipids that are not enriched overall in the neighborhood of Piezo1, such as cholesterol. The lipid fingerprint of Piezo1 is similar to that observed for other membrane proteins (59), including the binding of PIPs to the protein and the relative higher occupancy of polyunsaturated lipids compared with the saturated ones (Fig. S1). Polyunsaturated fatty acids have been shown to be able to modulate Piezo1 channel kinetics (66). The accumulation of specific polyunsaturated lipids close to the protein in our simulations, such as highly unsaturated phosphatidylethanolamines and PSs (Fig. S1), suggests that modulation could involve both direct interactions with the protein and alteration of the bulk membrane properties. Most other proteins studied in this way show a significant depletion of lyso-phosphatidylcholine near the protein (59). In contrast, the conically shaped lyso-phosphatidylcholine is enriched around Piezo1 (Fig. 2), which may be associated with membrane curvature induced by the protein. Below, we focus our detailed analysis on negative lipids and cholesterol that have been shown to modulate Piezo1 activity as described above.

Figure 2.

Lipid fingerprinting of the Piezo1 channel. (A) Given are the average and sem (standard error of the mean) of the depletion and enrichment (D/E) index of all lipid groups in three simulations within a 20-Å cutoff of Piezo1. Lipids are separated by the leaflet and by their tendency to flip-flop (these are noted as “both”). The D/E index is also calculated for lipids grouped according to tail saturation. The D/E of different PIP species are shown in the inset. (B) Given are the densities of PIPs, cholesterol, PIs, and PSs or PAs around Piezo1, shown as a fraction of the bulk density. The dashed lines represent the halfway point between the center of the system (Piezo1’s pore) with the bilayer bulk. To see this figure in color, go online.

Figure 3.

Significant contacts made with the lipids either in the upper leaflet (top), lower leaflet (bottom), or that can flip-flop between leaflets (inset). Residues that interact with a given lipid type are colored on the surface of a monomer of Piezo1, as viewed from two sides. Darker colors represent lipids interacting with, or occupying, that region of the protein for a larger percentage of the 20–30-μs analysis window of the simulations. An example colormap is shown to the left of the result for the PC. To see this figure in color, go online.

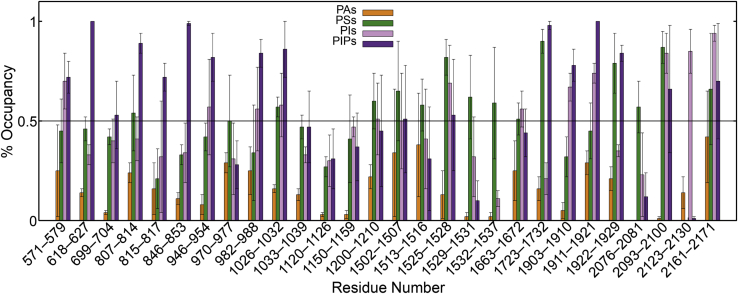

Specific binding sites for PIPs

Negative lipids such as PIPs, PIs, PAs, and PSs share common binding sites, as seen in Fig. 4 (more detail is available in Table S2), characterized by the presence of basic residues on the protein surface, some of which are identified in a recent preprint (67). PIPs, having the largest negative charge, tend to have the highest occupancy in many of these sites. This is particularly true of sites that contain multiple positive residues, such as R623/K624/K627, R850/R852, R1724/K1727/R1728, and K1911/R1912/R1915/R1919/R1921. Some other sites have greater than 50% occupancy for PIPs, but PSs and other PIs share the site, such as K2196/K2197 and K2163/K2166-K2169. In contrast, many of the sites containing a single basic residue, such as R1527 and R1534, have a slight preference for PSs. Many of these regions of negative lipid binding are also the location of disease-causing mutations. For example, each of R808Q (discussed in more detail below), R972H, R1925W, and ΔK2169 lead to hereditary xerocytosis (68). We find that although R808 has an occupancy of greater than 75% for PIPs, R972 has a slight preference for PS, and R1925 and K2169 near the pore domain have a PIP or PI lipid binding to them for at least 70% of the simulation time.

Figure 4.

Specific protein-lipid interactions for negatively charged lipids. Average ± SE of the percentage of time that each lipid type is interacting with specific residues during the last 10 μs of the repeat simulations. Results shown for PIPs, PIs, PSs, and PAs. To see this figure in color, go online.

As noted in the introduction, PIPs are a particularly interesting lipid class. Our simulations include PI-monophosphates, PI-diphosphates, and PI-triphosphates (noting that CG-MD can separate these three categories but cannot distinguish lipid types within them, i.e., PI(3,4)P2 vs. PI(4,5)P2). PIPs (especially the di- and tri-phosphate species) are not only highly enriched around the protein (inset to Fig. 2 A) but can be seen to form high-density regions around both the pore domain and propellers (Fig. 2 B). The clustering of PIPs to specific sites is also evident by looking at the map of residues frequently interacting with PIPs (Fig. 5 A) and selected snapshots as depicted in the inset of Fig. 5 A.

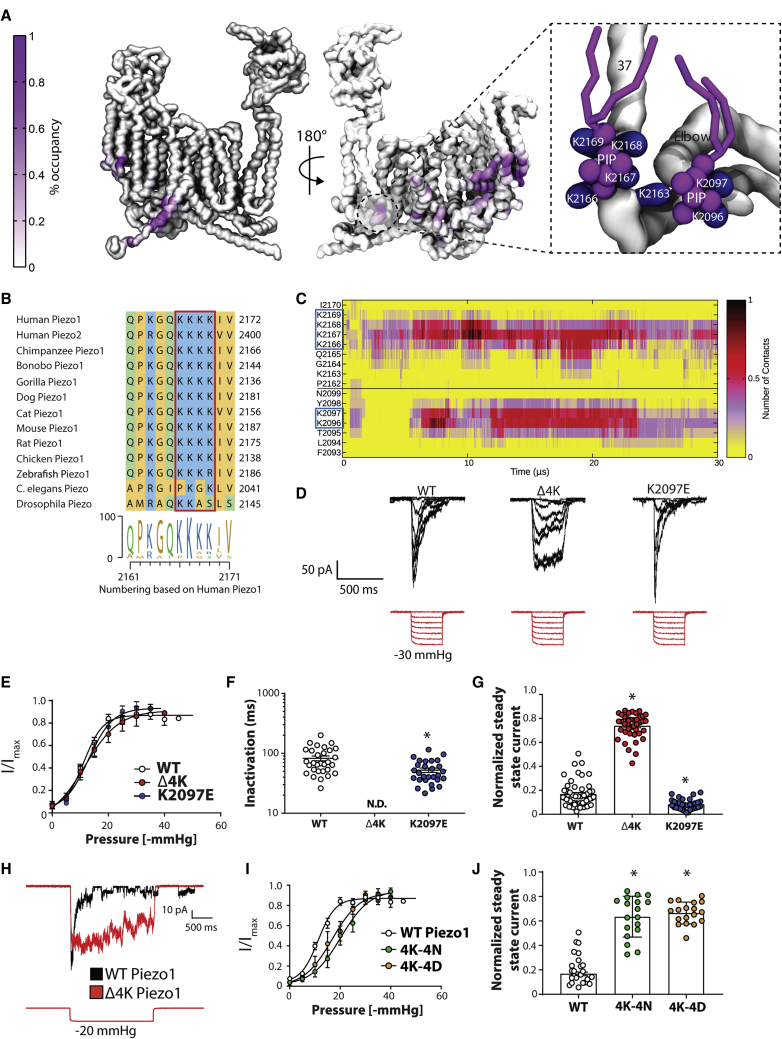

Figure 5.

Computationally identified phosphatidylinositide-binding sites and the effect of mutations on Piezo1 channel function. (A) The contact map of a Piezo1 monomer indicates the residues that form consistent interactions with PIPs (purple) with the protein backbone, represented as a gray surface. The colorbar shows the percentage of frames that PIPs are interacting with that particular residue (only from 20 to 30 μs). The inset shows a snapshot of a PIP-binding site close to the pore, with relevant lysines shown in blue and PIPs in purple. Residue numbering corresponds to the human sequence for comparison with experimental data, although simulations are conducted on mPiezo1. (B) Shown is the complete conservation of human Piezo1 K2166-2169 in mammalian homologs. (C) Given is contact analysis showing interactions between PIPs and Piezo1 residues, highlighting the stability of the interaction of specific residues with PIPs throughout the simulation. (D) Deletion of conserved lysines in human Piezo1 is associated with xerocytosis and causes a loss of inactivation. Shown are representative traces of WT human Piezo1, a mutant in which these conserved lysines are deleted (Δ4K), and charge reversal at another site located near these conserved lysines (hK2097E, equivalent to mK2113). Shown are all the cell-attached traces recorded at a holding potential of −65 mV. (E) Shown are the pressure response curves of WT Piezo1 and the two mutants (n ≥ 6). (F) Shown is the inactivation time constant in milliseconds comparing WT with the PIP-binding mutants from pressure pulses of 20–40 mmHg. The inactivation phenotype of Δ4K mutant was so profound that accurate fitting of “mesoscopic”-cell-attached currents was not possible (not determined). (G) The analysis of the steady-state current from pressure pulses of 20–40 mmHg shows a large increase in Δ4K and a modest but statistically significant decrease in the K2097E mutant. The data represent mean ± SE (H) Shown is the long 2-s square wave pressure pulse illustrating the vast difference in the Δ4K mutant to WT Piezo1. (I) Shown are the pressure response curves of WT Piezo1 compared with 4K-4N and 4K-4D mutants (n ≥ 6). (J) The analysis of the steady-state current from pressure pulses of 20–40 mmHg shows a large increase in the steady-state current, which is indicative of a loss of inactivation in both 4K-4N and 4K-4D. The data represent mean ± SE. The asterisk (∗) represents statistically significant p < 0.05 from WT controls using Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc test. To see this figure in color, go online.

Among many specific protein-PIP-binding sites identified, an intriguing site was determined around the pore domain, shown on the right in Fig. 5 A. There is a noticeable patch of four lysines, K2166-K2169 (human sequence numbering), right before helix 37, which is highly conserved in Piezo1 channel homologs (Fig. 5 B). These lysines, along with some adjacent lysines (K2096-K2097 and K2163), were identified to consistently interact with PIPs (most notably di-phosphate species, Fig. 6) or other negative lipids, as seen by the constancy of protein-PIP contacts at these sites (Fig. 5 C). To test the importance of this site, we removed this string of four lysines (Δ4K mutant) because this variant had been noted to cause xerocytosis (8). Patch-clamp electrophysiology in the cell-attached configuration show that this mutation reduces channel inactivation significantly. Using large cell-attached patches with “mesoscopic” currents arising from multiple channels, it was not possible to measure the inactivation rate because the noninactivating phenotype was so severe (Fig. 5, D and F), although the pressure sensitivity of the mutant was unchanged from WT (Fig. 5 E). As previously described (11), we measured the degree of steady-state current, which clearly quantifies the marked difference with WT (Fig. 5 G). This change becomes even more evident when looking at longer pressure pulses, as shown in Fig. 5 H. We also used depolarizing voltages to compare deactivation, and again, deactivation of the Δ4K mutant was slower than the WT (Fig. S2, A and B).

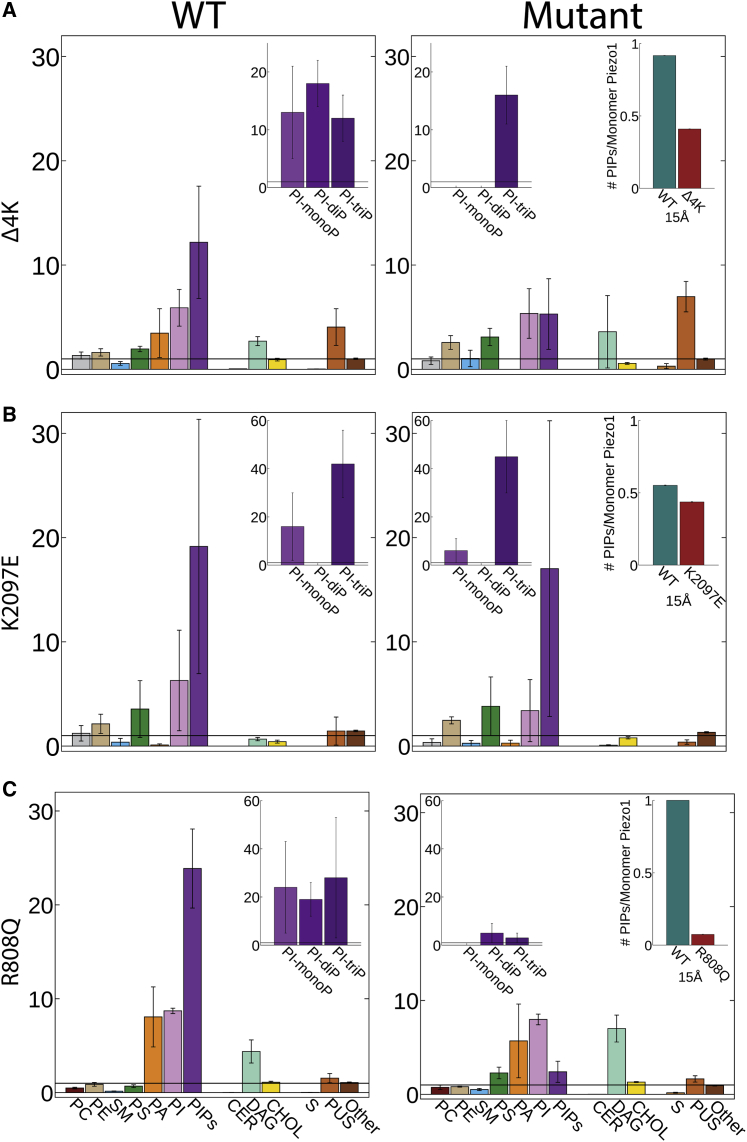

Figure 6.

Mutation of disease-causing residues alters PIP binding. Given are the D/E indices for both the WT (left) and mutants (right) for the Δ4K (A), K2097E (B), and R808Q (C) mutants. The averages of the Δ4K and middle and bottom rows of D/E indices were calculated by averaging each propeller’s D/E index for each lipid, and the mean ± SE is shown. The WT Δ4K mutation is an average of three replicates, which each had their own average and mean ± SE from the three propellers in each simulation. The insets show D/E for different PIP species and the number of PIP molecules per monomer within 15 Å of the site of mutation in both the WT and mutant. To see this figure in color, go online.

The loss of inactivation, and slowing of deactivation of the Δ4K, may be caused by changes in lipid binding or to structural changes in the protein itself. To help address this question, we examined two additional mutants at this location: 4K→4N and 4K→4D. As for Δ4K, both mutations remove inactivation (Fig. S2 C). Unlike the Δ4K mutant, these produce a significant rightward shift in the pressure response curve (WT 11.92 ± 0.81, n = 15; 4K-4N 20.23 ± 1.6, n = 7; and 4K-4D 16.84 ± 1.7 n = 6) (Fig. 5, I and J) and match similar data for 4K→4A from the Xiao Laboratory (69). This indicates a loss of sensitivity to force, which fits with experiments documenting PIP removal (43). Although it is hard to imagine all mutations could cause the same structural change, all can be expected to remove binding of negative lipids, such as PIPs. This leads us to the hypothesis that the functional consequences of the xerocytosis-causing Δ4K may be caused by both a structural change and by changes in essential lipid-binding sites. In support of the latter, simulations of the Δ4K mutant show a large reduction in PIP enrichment around the protein and, specifically, a loss of mono- and di-phosphate PIP molecules at this site (Fig. 6, top row).

We also use our simulations to examine a range of other mutations occurring at PIP-binding sites. A mutation of the residue K2097E (K2113E in mouse) has a modest effect in speeding up inactivation (Fig. 5, D and G). This is probably not by preventing PIP binding because no significant change is seen in simulations of this mutant (Fig. 6, middle row). Our simulations also show that R808 binds all species of PIPs (Fig. 6, bottom row). R808Q is a rare variant with a minor allele frequency of 0.6% and has been reported as a gain-of-function mutant associated with xerocytosis (68). However, this mutation has been reported in patients in combination with G782S, though which of these are disease causing has yet to be addressed. Simulations of the R808Q mutant show a loss of PIP binding but no loss of other lipids (Fig. 6, bottom row), suggesting that the gain of function may be related to changes in the pattern of lipid binding.

Previous work suggested conversion of R2119 to alanine (R2135 in mouse (37)) led to a nonfunctional channel, with structural information suggesting an interaction with negatively charged lipids. However, we did not see any negatively charged lipids interacting with this residue. We do, however, see a salt bridge between R2119 and E2140 that is present most of the time in all three monomers and in all three replicates (Fig. S3, A and B). This salt bridge may be the reason for the need for arginine at this position. Another critical salt bridge identified in the simulations is that between the elbow and beam at positions R1955 and E1342/E1343. The mutation R1955C is found in a case of hereditary xerocytosis (70) and is associated with colorectal adenomatous polyposis and displays a modest reduction in pressure sensitivity (Fig. S3 C). Negative lipids do not congregate around this site, suggesting that the pathology related to this mutation may be explained by a break in a salt bridge, which is important for conveying forces felt in the propellers via the beam to the pore (71).

Specific binding sites for cholesterol

Because cholesterol is present because 30% of the membrane fraction in our CG-MD simulations, there are naturally a large number of residues on Piezo1 that interact with cholesterol (Fig. 3). However, there are certain places on the structure of Piezo1 where cholesterol is found most frequently (Fig. 3) that may help understand the importance of cholesterol to Piezo1 function. We searched for cholesterol-recognition motifs (termed CRAC and CARC) (72,73) within the sequence of Piezo1 using ProSite (https://prosite.expasy.org/scanprosite/) and identified 19 CRAC motifs and 39 CARC motifs (Fig. 7 A; Table S3). Previous cross-linking studies showed an interaction of cholesterol with four residues (LVPF), which are part of a CARC motif we have identified and are located in the anchor domain between the two elbow regions of Piezo1 (74), a region previously identified as being highly conserved (75) (Fig. 7 B, residues 2127–2130 in mouse). Cholesterol was observed in this same site in all three monomers, on average 75 ± 20% of the simulation duration (Fig. 7 D, bottom right), highlighting the ability of the coarse-grained simulations to reproduce known protein-lipid interactions.

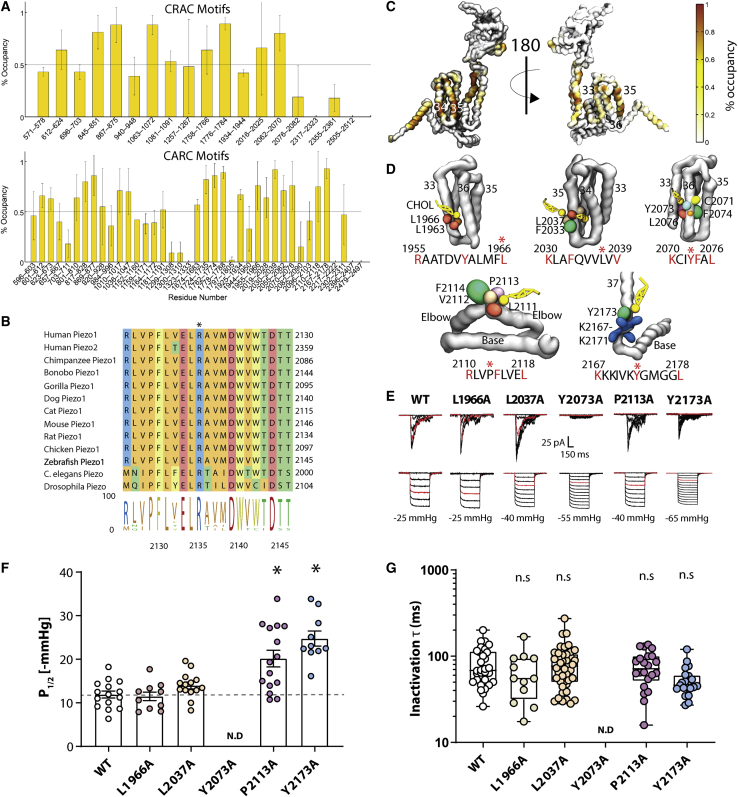

Figure 7.

Computationally identified cholesterol-binding sites and the effect of point mutations on Piezo1 activation. (A) Shown are the CRAC (top) and CARC (bottom) motifs identified by ExPasy ProSite, and their average percentage of occupancy ± SE with cholesterol in simulation. (B) Shown is the alignment of anchor domain and conservation of human Piezo1 P2113 in all Piezo1 homologs. (C) Given is the cholesterol (yellow) contact map of a Piezo1 monomer (only the regions close to the pore shown for clarity), with the backbone represented as a gray surface. Brown regions denote areas in which a cholesterol molecule resides greater than 65% of the simulation. (D) Shown are snapshots of four CARC motifs near the pore domain that bind cholesterol. The relevant sequence and relevant residues are highlighted, and the human numbering is shown. Residues that were subsequently mutated are indicated by an asterisk (∗). (E) Shown are the cell-attached currents of human Piezo1 WT and residues identified to interact with cholesterol: L1966A, L2037A, Y2073A, P2113A, and Y2173A. All are part of bona fide cholesterol-recognition motifs. Shown are the currents recorded at a holding potential of −65 mV and, for comparison, the −15 mmHg pulse of each representative trace is shown in red. (F) Shown is the calculated P1/2 from each patch compared with WT (not determined). (G) Given is a box and whiskers plot showing the inactivation time constant from the cell-attached patches, illustrating that there is little difference between these mutants and WT. The data represent mean ± SE. The asterisk (∗) represents statistically significant p < 0.05 from WT controls using Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc test. To see this figure in color, go online.

To test the importance of predicted cholesterol-binding sites, we examined a number of alanine mutations in this conserved elbow region (i.e., P2113A) and in other parts of the first Piezo1 repeat, as identified in simulations and by recognition sequences to interact with cholesterol (L1966A, L2037A and Y2073A, and Y2173A) (Fig. 7 C; Table S3, highlighted in yellow). L1966A and L2037A behave similar to WT, with a similar P1/2 and inactivation properties (Fig. 7, E–G). However, P2113A has a right-shifted pressure response curve (WT 11.92 ± 0.81, n = 15; P2113A 20.18 ± 1.92 mmHg, n = 15) (Fig. 7 D). mPiezo1 also displays loss of function when this residue is mutated (P2129A (71,76)). Y2073A could not be opened regardless of the pressure applied up to the lytic limit of the patch. Simulations of the P2113A (76) mutant show loss of cholesterol binding at this residue (cholesterol occupancy is 96% for P2113 and 5% for A2113) but no obvious structural changes in the protein. In contrast, Y2073 appears to be part of a hydrophobic cluster that maintains the integrity of the four-helix bundle closest to the pore (Fig. S4 A).

Many of these identified cholesterol-binding sites also contain residues which, when mutated, lead to disease. Three CRAC motifs contain such mutations in their key residues: R1943Q (12) (the arginine in motif LaqgtYrplrR) and K2070Q (77) (the lysine in motif VaqlwYfvK). In addition, there are six such mutations in CARC motifs: R1797C (78,79) (RsqllcYgL), R1925W (80) (RrlqgFcvsL), R1955C (70,81) (RaatdvYalmfL), K2070Q (77) (KciYFaL), R2110W (78)/R2110Q (80) (RlvpFlveL), and R2302H (12) (RftwnFqrdL). We are only interested in missense variants, and many of these may be involved in the formation of key structural interactions, such as salt bridges (Fig. S4, “Missense”). An example of this is the mutations at R1955, which appears to form a stable salt bridge with E1342/E1343, thus linking the beam to the propeller (Fig. S3 C). K2070 forms a salt bridge with D1976, presumably helping to hold this central helical bundle together (Fig. S4 B). Although part of a cholesterol-recognition motif, R2302 forms a salt bridge with D2209 inside the cap of Piezo1, well away from the membrane (Fig. S4 C). R2110 forms a critical bridge with D2141 and E2471 between the elbow region, the base of the base, and helix 38. This is most likely another connection between the propeller and the pore (Document S1. Figs. S1–S4 and Tables S1–S4, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material). Recent work implicates another loss-of-function mutation as a cause of bicuspid aortic valve (Fig. S4 E; (82)); this forms part of another cholesterol-recognition motif (Y2022H).

Discussion

There is accumulating data showing that lipids can regulate the function of Piezo channels (66,83). Some of these affects are likely to come from altering the global membrane properties such bending rigidity or stiffness, but we believe it is likely that Piezo1 generates essential protein-lipid interactions. To address this, we have conducted extensive analysis of the Piezo1-lipid interactions to identify a characteristic lipid fingerprint for Piezo1. This shows membrane distortions and an enrichment of phospholipids with unsaturated acyl chains. These flexible lipids can adopt many very different conformations that are similar in energy and are ideal to pack against the protein surface; this is particularly important for a protein that deforms the membrane as markedly as Piezo1. We identify a number of stable binding sites for negative lipids, including phosphoinositides, as well as for cholesterol. To test the importance of the binding sites, we conduct site-directed mutagenesis in combination with electrophysiology to show that many of these sites are functionally relevant. Furthermore, a large number of mutations at these sites are related to Piezo1-mediated pathologies.

In particular, we identify a highly conserved patch of four lysines which, when deleted, causes a gain-of-function xerocytosis phenotype. This site stably recruits PIP species. These residues lie on an intracellular linker that has previously been shown to be important for transducing forces felt in the propeller domains to the pore, analogous to the linker that connects the voltage sensor and pore regions of voltage sensitive channels. This site has been identified as being able to interact with the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic-reticulum Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA), whose presence suppresses the mechanosensitivity of Piezo1 (69). A Piezo1 mutant in which all four lysines are converted to alanines has been shown to remove this interaction, which would yield a Piezo1 gain-of-function phenotype. The presence of PIPs at this site may aid or hinder SERCA binding, providing another possible mechanism by which lipids can regulate Piezo1. This is unlikely to be the full explanation of Piezo1 mediated xerocytosis, however, because red blood cells lack an endoplasmic reticulum and, thus, the potential for the same SERCA2 interaction (69). Our careful analysis of cell-attached currents show that deletions or mutations at this site cause a profound loss of inactivation, and a slowing of deactivation, which is congruent with a gain-of-function phenotype that causes xerocytosis. This intriguing result shows that the intracellular linker not only couples the propellers and pore as required for mechanosensation but also has a critical role in channel inactivation.

Cholesterol has been shown to cross-link with a number of regions of Piezo1, including the apex of the anchor domain, an area where cholesterol is enriched during our simulations (74). Mutations in both this anchor domain (P2113A) and in nearby cholesterol-recognition motifs in close proximity to the pore (Y2073A and Y2173A) influence function. However, many of the mutants in predicted cholesterol-binding domains are WT like, suggesting that cholesterol effects may be mediated by both specific protein-lipid interactions and a global influence on the mechanical properties of the membrane (42,84). Some of the mutations at cholesterol-binding sites that alter function may do so by affecting lipid binding. However, some of these may also be altering the structural stability of the protein’s different states because some appear to be involved in key structural interactions within the protein. Examples of such structural interactions identified here are residues involved either in connecting the propeller and pore domains (particularly the salt bridge formed by residues R1955, K2070, and R2110) or in hydrophobic interactions that maintain the integrity of the helical bundles or connect the first helical bundle to the pore helices (e.g., residues Y2022, Y2073, and Y2173). Weakening any of these can be expected to alter the connection between the force sensing propeller and pore domain.

Although we have identified a large number of likely binding sites for a range of different lipid types, it remains to be experimentally proven that lipids do bind at these locations in the full-length protein because such experiments (for example, using mass spectrometry (13,85)) remain challenging. However, we have shown that we can reproduce three cholesterol-binding sites on Piezo1 proven by chemical cross-linking (74). Furthermore, these mutants largely follow the consequences of cholesterol removal (i.e., reduce channel sensitivity to applied force (41,42)). However, none of those tested seem to influence inactivation (41). CG-MD simulations on other membrane proteins have also been successful in reproducing or predicting proven sites (59,86, 87, 88, 89). Although we hypothesize that the functional consequences of mutations at some of the lipid-binding sites (particularly for PIPs) are due to alterations in specific lipid binding, this is also difficult to prove directly because of the fact that there are many binding sites for each lipid type. Removing PIP binding at one site (e.g., the Δ4K mutant) may not be expected to replicate the global PIP-depletion phenotype because a large number of other PIP-binding sites remain. In addition, the sharing of binding sites between negative lipids means that they are likely to be able to compensate for each other to some extent. Finally, these binding sites may not be essential for stretch activation in patch-clamp studies but may be important focal points for interactions with other structural proteins such as those found at cell-cell contacts (32) or focal adhesions (31,90), which are critical foci for cellular mechanotransduction.

It is interesting that lipid-binding sites can have a positive or negative modulatory effect on Piezo1 channel function. These sites seem to influence not only mechanosensitivity but also gating kinetics. These results, in addition to work on specific and global effects of lipids on Piezo1 (41,42,45,66,83) make it clear that Piezo1 mutations, where possible, should be studied in the membranes of natively expressing Piezo1 cells. Finally, the curvature of the membrane induced by Piezo1 (36) likely requires strong protein-lipid interactions to anchor the bilayer around the curved shape of Piezo1. More work is required to determine if the binding sites seen for specific lipid types are essential for locally curving the membrane.

Author Contributions

A.B. performed the simulations, completed simulation analysis, and helped write the article. C.D.C. helped design the project, performed the electrophysiology experiments, and helped write the article. J.B. assisted in simulation setup, wrote programs that were used in analysis, and contributed to the interpretation of the simulations. J.L. performed part of the electrophysiology experiments and generated Piezo1 mutations using site-directed mutagenesis. H.S.M.C. simulated and analyzed the R808Q mutation. S.J.M. helped design and interpret the simulations. B.M. provided guidance for the project and helped interpret the data. B.C. helped design the project and supervised the simulations and assisted in the analysis and helped write the article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Tsjerk Wassenaar for his invaluable advice and help with his Martinate script. We also thank Helgi Ingolfsson for usage of his original D/E script and for permission to publish it.

We are grateful for funding from the Australian Research Council (FT130100781 and DP200100860) that supported this research. S.J.M. is supported by an ERC Advanced grant “COMP-MICR-CROW-MEM.” J.B. acknowledges funding from the TOP grant of S.J.M. (NWO) and the EPSRC program grant EP/P021123/1. This work was also supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (grants APP1140064 and APP1150083 and fellowship APP1156489 to R.G.P. and APP1135974 to B.M.).

Editor: Philip Biggin.

Footnotes

Amanda Buyan and Charles D. Cox contributed equally to this work.

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.07.043.

Contributor Information

Charles D. Cox, Email: c.cox@victorchang.edu.au.

Ben Corry, Email: ben.corry@anu.edu.au.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Coste B., Mathur J., Patapoutian A. Piezo1 and Piezo2 are essential components of distinct mechanically activated cation channels. Science. 2010;330:55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.1193270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zeng W.Z., Marshall K.L., Patapoutian A. PIEZOs mediate neuronal sensing of blood pressure and the baroreceptor reflex. Science. 2018;362:464–467. doi: 10.1126/science.aau6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Servin-Vences M.R., Moroni M., Poole K. Direct measurement of TRPV4 and PIEZO1 activity reveals multiple mechanotransduction pathways in chondrocytes. eLife. 2017;6:e21074. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ranade S.S., Qiu Z., Patapoutian A. Piezo1, a mechanically activated ion channel, is required for vascular development in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:10347–10352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409233111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J., Hou B., Beech D.J. Piezo1 integration of vascular architecture with physiological force. Nature. 2014;515:279–282. doi: 10.1038/nature13701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mikhailov N., Leskinen J., Giniatullin R. Mechanosensitive meningeal nociception via Piezo channels: implications for pulsatile pain in migraine? Neuropharmacology. 2019;149:113–123. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang J., La J.H., Hamill O.P. PIEZO1 is selectively expressed in small diameter mouse DRG neurons distinct from neurons strongly expressing TRPV1. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2019;12:178. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2019.00178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albuisson J., Murthy S.E., Patapoutian A. Dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis linked to gain-of-function mutations in mechanically activated PIEZO1 ion channels. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:1884. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarychanski R., Schulz V.P., Gallagher P.G. Mutations in the mechanotransduction protein PIEZO1 are associated with hereditary xerocytosis. Blood. 2012;120:1908–1915. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-04-422253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lukacs V., Mathur J., Krock B.L. Impaired PIEZO1 function in patients with a novel autosomal recessive congenital lymphatic dysplasia. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8329. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bae C., Gnanasambandam R., Gottlieb P.A. Xerocytosis is caused by mutations that alter the kinetics of the mechanosensitive channel PIEZO1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:E1162–E1168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219777110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Glogowska E., Schneider E.R., Gallagher P.G. Novel mechanisms of PIEZO1 dysfunction in hereditary xerocytosis. Blood. 2017;130:1845–1856. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-786004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laganowsky A., Reading E., Robinson C.V. Membrane proteins bind lipids selectively to modulate their structure and function. Nature. 2014;510:172–175. doi: 10.1038/nature13419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee A.G. How lipids affect the activities of integral membrane proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1666:62–87. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Corradi V., Sejdiu B.I., Tieleman D.P. Emerging diversity in lipid-protein interactions. Chem. Rev. 2019;119:5775–5848. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caires R., Sierra-Valdez F.J., Cordero-Morales J.F. Omega-3 fatty acids modulate TRPV4 function through plasma membrane remodeling. Cell Rep. 2017;21:246–258. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perozo E., Kloda A., Martinac B. Physical principles underlying the transduction of bilayer deformation forces during mechanosensitive channel gating. Nat. Struct. Biol. 2002;9:696–703. doi: 10.1038/nsb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nomura T., Cranfield C.G., Martinac B. Differential effects of lipids and lyso-lipids on the mechanosensitivity of the mechanosensitive channels MscL and MscS. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:8770–8775. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1200051109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moe P., Blount P. Assessment of potential stimuli for mechano-dependent gating of MscL: effects of pressure, tension, and lipid headgroups. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12239–12244. doi: 10.1021/bi0509649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eastwood A.L., Sanzeni A., Goodman M.B. Tissue mechanics govern the rapidly adapting and symmetrical response to touch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2015;112:E6955–E6963. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1514138112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sukharev S.I., Blount P., Kung C. A large-conductance mechanosensitive channel in E. coli encoded by mscL alone. Nature. 1994;368:265–268. doi: 10.1038/368265a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sukharev S. Purification of the small mechanosensitive channel of Escherichia coli (MscS): the subunit structure, conduction, and gating characteristics in liposomes. Biophys. J. 2002;83:290–298. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75169-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dong Y.Y., Pike A.C., Carpenter E.P. K2P channel gating mechanisms revealed by structures of TREK-2 and a complex with Prozac. Science. 2015;347:1256–1259. doi: 10.1126/science.1261512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brohawn S.G., Su Z., MacKinnon R. Mechanosensitivity is mediated directly by the lipid membrane in TRAAK and TREK1 K+ channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:3614–3619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320768111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy S.E., Dubin A.E., Patapoutian A. OSCA/TMEM63 are an evolutionarily conserved family of mechanically activated ion channels. eLife. 2018;7:e41844. doi: 10.7554/eLife.41844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xue F., Cox C.D., Martinac B. Membrane stiffness is one of the key determinants of E. coli MscS channel mechanosensitivity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2020;1862:183203. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox C.D., Bae C., Martinac B. Removal of the mechanoprotective influence of the cytoskeleton reveals PIEZO1 is gated by bilayer tension. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:10366. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Syeda R., Florendo M.N., Patapoutian A. Piezo1 channels are inherently mechanosensitive. Cell Rep. 2016;17:1739–1746. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gottlieb P.A., Bae C., Sachs F. Gating the mechanical channel Piezo1: a comparison between whole-cell and patch recording. Channels (Austin) 2012;6:282–289. doi: 10.4161/chan.21064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole K., Herget R., Lewin G.R. Tuning Piezo ion channels to detect molecular-scale movements relevant for fine touch. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:3520. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ellefsen K.L., Holt J.R., Pathak M.M. Myosin-II mediated traction forces evoke localized Piezo1-dependent Ca2+ flickers. Commun. Biol. 2019;2:298. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0514-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J., Jiang J., Xiao B. Tethering Piezo channels to the actin cytoskeleton for mechanogating via the E-cadherin-β-catenin mechanotransduction complex. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.05.12.092148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Le Roux A.L., Quiroga X., Roca-Cusachs P. The plasma membrane as a mechanochemical transducer. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2019;374:20180221. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2018.0221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cox C.D., Bavi N., Martinac B. Biophysical principles of ion-channel-mediated mechanosensory transduction. Cell Rep. 2019;29:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.08.075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shi Z., Graber Z.T., Cohen A.E. Cell membranes resist flow. Cell. 2018;175:1769–1779.e13. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2018.09.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guo Y.R., MacKinnon R. Structure-based membrane dome mechanism for Piezo mechanosensitivity. eLife. 2017;6:e33660. doi: 10.7554/eLife.33660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saotome K., Murthy S.E., Ward A.B. Structure of the mechanically activated ion channel Piezo1. Nature. 2018;554:481–486. doi: 10.1038/nature25453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhao Q., Zhou H., Xiao B. Structure and mechanogating mechanism of the Piezo1 channel. Nature. 2018;554:487–492. doi: 10.1038/nature25743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lewis A.H., Grandl J. Inactivation kinetics and mechanical gating of Piezo1 ion channels depend on subdomains within the cap. Cell Rep. 2020;30:870–880.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.12.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Botello-Smith W.M., Jiang W., Luo Y. A mechanism for the activation of the mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel by the small molecule Yoda1. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:4503. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-12501-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ridone P., Pandzic E., Martinac B. Disruption of membrane cholesterol organization impairs the concerted activity of PIEZO1 channel clusters. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/604488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qi Y., Andolfi L., Hu J. Membrane stiffening by STOML3 facilitates mechanosensation in sensory neurons. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:8512. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borbiro I., Badheka D., Rohacs T. Activation of TRPV1 channels inhibits mechanosensitive Piezo channel activity by depleting membrane phosphoinositides. Sci. Signal. 2015;8:ra15. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Narayanan P., Hütte M., Schmidt M. Myotubularin related protein-2 and its phospholipid substrate PIP2 control Piezo2-mediated mechanotransduction in peripheral sensory neurons. eLife. 2018;7:e32346. doi: 10.7554/eLife.32346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsuchiya M., Hara Y., Umeda M. Cell surface flip-flop of phosphatidylserine is critical for PIEZO1-mediated myotube formation. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:2049. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04436-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coste B., Xiao B., Patapoutian A. Piezo proteins are pore-forming subunits of mechanically activated channels. Nature. 2012;483:176–181. doi: 10.1038/nature10812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Bourne P.E. The protein Data Bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fiser A., Sali A. Modeller: generation and refinement of homology-based protein structure models. Methods Enzymol. 2003;374:461–491. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(03)74020-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marrink S.J., Risselada H.J., de Vries A.H. The MARTINI force field: coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:7812–7824. doi: 10.1021/jp071097f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Jong D.H., Singh G., Marrink S.J. Improved parameters for the martini coarse-grained protein force field. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2013;9:687–697. doi: 10.1021/ct300646g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.de Jong D.H., Baoukina S., Marrink S.J. Martini straight: boosting performance using a shorter cutoff and GPUs. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2016;199:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:014101. doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Essman U., Perera L., Berkowitz M.L. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;102:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Periole X., Cavalli M., Ceruso M.A. Combining an elastic network with a coarse-grained molecular force field: structure, dynamics, and intermolecular recognition. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009;5:2531–2543. doi: 10.1021/ct9002114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Siuda I., Thøgersen L. Conformational flexibility of the leucine binding protein examined by protein domain coarse-grained molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Model. 2013;19:4931–4945. doi: 10.1007/s00894-013-1991-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wassenaar T.A., Ingólfsson H.I., Marrink S.J. Computational lipidomics with insane: a versatile tool for generating custom membranes for molecular simulations. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corradi V., Mendez-Villuendas E., Tieleman D.P. Lipid-protein interactions are unique fingerprints for membrane proteins. ACS Cent. Sci. 2018;4:709–717. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.8b00143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Castillo N., Monticelli L., Tieleman D.P. Free energy of WALP23 dimer association in DMPC, DPPC, and DOPC bilayers. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 2013;169:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2013.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pronk S., Páll S., Lindahl E. GROMACS 4.5: a high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:845–854. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Humphrey W., Dalke A., Schulten K. VMD: visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:33–38. doi: 10.1016/0263-7855(96)00018-5. 27–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ingólfsson H.I., Arnarez C., Marrink S.J. Computational ‘microscopy’ of cellular membranes. J. Cell Sci. 2016;129:257–268. doi: 10.1242/jcs.176040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ingólfsson H.I., Melo M.N., Marrink S.J. Lipid organization of the plasma membrane. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:14554–14559. doi: 10.1021/ja507832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ge J., Li W., Yang M. Architecture of the mammalian mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel. Nature. 2015;527:64–69. doi: 10.1038/nature15247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Romero L.O., Massey A.E., Vásquez V. Dietary fatty acids fine-tune Piezo1 mechanical response. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1200. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09055-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wenjuan J., Del Rosario J.S., Luo Y.L. A piezo1 open state reveals a multi-fenestrated ion permeation pathway. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.12.988378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Andolfo I., Alper S.L., Iolascon A. Multiple clinical forms of dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis arise from mutations in PIEZO1. Blood. 2013;121:3925–3935. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-02-482489. S3921–S3912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang T., Chi S., Xiao B. A protein interaction mechanism for suppressing the mechanosensitive Piezo channels. Nat. Commun. 2017;8:1797. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01712-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang E., Voelkel E.B., Gallagher P.G. Hemoglobin C trait accentuates erythrocyte dehydration in hereditary xerocytosis. Pediatr. Blood Cancer. 2017;64 doi: 10.1002/pbc.26444. 10.1002/pbc.26444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang Y., Chi S., Xiao B. A lever-like transduction pathway for long-distance chemical- and mechano-gating of the mechanosensitive Piezo1 channel. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1300. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-03570-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Di Scala C., Baier C.J., Barrantes F.J. Relevance of CARC and CRAC cholesterol-recognition motifs in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor and other membrane-bound receptors. Curr. Top. Membr. 2017;80:3–23. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctm.2017.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Posada I.M., Fantini J., Goñi F.M. A cholesterol recognition motif in human phospholipid scramblase 1. Biophys. J. 2014;107:1383–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hulce J.J., Cognetta A.B., Cravatt B.F. Proteome-wide mapping of cholesterol-interacting proteins in mammalian cells. Nat. Methods. 2013;10:259–264. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Prole D.L., Taylor C.W. Identification and analysis of putative homologues of mechanosensitive channels in pathogenic protozoa. PLoS One. 2013;8:e66068. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Coste B., Murthy S.E., Patapoutian A. Piezo1 ion channel pore properties are dictated by C-terminal region. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:7223. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Datkhaeva I., Arboleda V.A., Janzen C. Identification of novel PIEZO1 variants using prenatal exome sequencing and correlation to ultrasound and autopsy findings of recurrent hydrops fetalis. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018;176:2829–2834. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.40533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russo R., Andolfo I., Iolascon A. Multi-gene panel testing improves diagnosis and management of patients with hereditary anemias. Am. J. Hematol. 2018;93:672–682. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Shefer Averbuch N., Steinberg-Shemer O., Tamary H. Targeted next generation sequencing for the diagnosis of patients with rare congenital anemias. Eur. J. Haematol. 2018;101:297–304. doi: 10.1111/ejh.13097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Picard V., Guitton C., Garçon L. Clinical and biological features in PIEZO1-hereditary xerocytosis and Gardos channelopathy: a retrospective series of 126 patients. Haematologica. 2019;104:1554–1564. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2018.205328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Spier I., Kerick M., Aretz S. Exome sequencing identifies potential novel candidate genes in patients with unexplained colorectal adenomatous polyposis. Fam. Cancer. 2016;15:281–288. doi: 10.1007/s10689-016-9870-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Faucherre A., Moha ou Maati H., Jopling C. Piezo1 is required for outflow tract and aortic valve development. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020;143:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2020.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cox C.D., Gottlieb P.A. Amphipathic molecules modulate PIEZO1 activity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019;47:1833–1842. doi: 10.1042/BST20190372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cordero-Morales J.F., Vásquez V. How lipids contribute to ion channel function, a fat perspective on direct and indirect interactions. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2018;51:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2018.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pliotas C., Dahl A.C., Naismith J.H. The role of lipids in mechanosensation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2015;22:991–998. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.3120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stansfeld P.J., Hopkinson R., Sansom M.S. PIP(2)-binding site in Kir channels: definition by multiscale biomolecular simulations. Biochemistry. 2009;48:10926–10933. doi: 10.1021/bi9013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yen H.Y., Hoi K.K., Robinson C.V. PtdIns(4,5)P2 stabilizes active states of GPCRs and enhances selectivity of G-protein coupling. Nature. 2018;559:423–427. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0325-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arnarez C., Mazat J.P., Periole X. Evidence for cardiolipin binding sites on the membrane-exposed surface of the cytochrome bc1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:3112–3120. doi: 10.1021/ja310577u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sengupta D., Chattopadhyay A. Molecular dynamics simulations of GPCR-cholesterol interaction: an emerging paradigm. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2015;1848:1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2015.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Yao M., Tijore A., Sheetz M. Force-dependent Piezo1 recruitment to focal adhesions regulates adhesion maturation and turnover specifically in non-transformed cells. bioRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.03.09.972307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.