Abstract

Previously, we have reported that 3-hydroxypropionate (3-HP) tolerance in Escherichia coli W is improved by deletion of yieP, a less-studied transcription factor. Here, through systems analyses along with physiological and functional studies, we suggest that the yieP deletion improves 3-HP tolerance by upregulation of yohJK, encoding putative 3-HP transporter(s). The tolerance improvement by yieP deletion was highly specific to 3-HP, among various C2–C4 organic acids. Mapping of YieP binding sites (ChIP-exo) coupled with transcriptomic profiling (RNA-seq) advocated seven potential genes/operons for further functional analysis. Among them, the yohJK operon, encoding for novel transmembrane proteins, was the most responsible for the improved 3-HP tolerance; deletion of yohJK reduced 3-HP tolerance regardless of yieP deletion, and their subsequent complementation fully restored the tolerance in both the wild-type and yieP deletion mutant. When determined by 3-HP-responsive biosensor, a drastic reduction of intracellular 3-HP was observed upon yieP deletion or yohJK overexpression, suggesting that yohJK encodes for novel 3-HP exporter(s).

Subject terms: Bacterial systems biology, Bacterial transcription, Bacterial development, Cellular microbiology, Metabolic engineering

Introduction

3-Hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), a three-carbon carboxylic acid, is an industrially relevant platform chemical. It can be converted to numerous value-added compounds such as acrylate, acrylamide, 1,3-propanediol, and malonic acid1. Chemical synthesis methods of 3-HP have been established, but they are costly and involve toxic intermediates2. Recently, environmentally-friendly biological methods have been developed, which use various microorganisms as recombinant host, including Escherichia coli, Synechococcus elongatus, Pseudomonas denitrificans, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Corynebacterium glutamicum3–9. Among them, E. coli has been extensively studied due to its rich genomic, physiological, and phenotypic information and availability of well-established genetic tool box10,11. However, the growth of E. coli strains, even the most tolerant E. coli W, is severely inhibited by 3-HP at > 300 mM, a level far lower than the industrially desirable 1.0 M12,13.

Toxic effect of short-chain aliphatic acids like 3-HP appears mostly upon their entry into the cytoplasm and/or intracellular production (Supplementary Fig. S1). Once entering or being produced inside the cell, acid molecules dissociate into protons (H+) and anions owing to the near-neutral pH of cytoplasm and its high salt concentration14. Complicated toxic effects caused by H+, anions and/or reaction intermediates of the acid do appear inside cell (Supplementary Fig. S1). Cellular responses to acids and/or low medium pH have been extensively studied in enterobacteria, particularly E. coli. These responses can be divided into ‘general’ and ‘specific’ acid-resistance, respectively. Altering of cell-membrane components or its structure, removing H+, restoring anion imbalance, etc. can be considered as ‘general’ responses, whereas anions-specific counteractions such as acceleration of cellular metabolisms to remove specific anions and their metabolites into non-toxic products can be classified as ‘specific’ responses8,15–17. In the general responses, up-regulation of the proton-consuming mechanism, such as glutamic-, arginine-, lysine-, and/or ornithine-dependent acid resistance, has been well documented15,18–20. Up-regulation of SOS responses and chaperons expression have also been well studied21,22. However, the ‘anion-specific’ acid-resistant mechanisms have been much less studied. In the case of 3-HP, mutation of SFA1, which encodes S-(hydroxymethyl)glutathione dehydrogenase in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, is known to reduce the toxic effect of 3-HP, because the mutation improves removal of the highly reactive intermediate 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde (3-HPA)8. In the same context, the up-regulation of frmB, the SFA1 ortholog, has also been noted when E. coli is growing in the presence of 3-HP23.

There have been several attempts to improve tolerance against organic acids. For example, for improved 3-HP tolerance in E. coli, a complex nitrogen source like yeast extract, mixture of several amino acids including methionine, threonine, and aromatic amino acids, and/or their biosynthetic intermediates, was added into the culture medium24. Up-regulation of biosynthetic pathways for several amino acids has also known to improve tolerance against 3-HP24. The so-called ‘adaptive laboratory evolution’ (ALE), repeated exposure of a microorganism to a target acid with an increasing concentration and selecting the fast-growing cell(s), is also a routine and popular practice8,25,26. In a recent study, by ALE, we isolated a highly 3-HP-tolerant E. coli W strain27. The strain contained 13 point-mutations, including alterations in glpK and yieP, and could grow in the presence of 800 mM 3-HP when yeast extract was supplemented to the culture medium. Furthermore, the strain could produce more 3-HP than its parent counterpart when the mutated glpK gene was reverted to the native form. Interestingly, the mutation in one specific gene named yieP, encoding a less-characterized transcriptional regulator28, was entirely responsible for the improved 3-HP tolerance. When the yieP gene was deleted, both the wild-type and the evolved strains exhibited the same tolerance to 3-HP; and when the native yieP was re-expressed, both the strains lost their tolerance. Although the transcriptional binding-sites of YieP was reported28, the cellular mechanism how the yieP deletion confers 3-HP tolerance has not been elucidated.

This study aims to investigate the 3-HP tolerance mechanism acquired by deletion of the global regulator encoded by yieP. Specificity of 3-HP tolerance by ΔyieP, genome-wide transcription profiles in response to the yieP deletion, and systems-level YieP binding landscape were investigated to select and identify genes/operons responsible for the improved 3-HP tolerance. Deletion and subsequent complementation of the selected targets were also conducted to confirm their physiological roles. This study suggests the presence of putative 3-HP exporter(s) encoded by yohJK, the upregulation of which is resulted by ΔyieP and renders 3-HP tolerance in E. coli.

Results

Tolerance improvement by yieP deletion is highly specific to 3-HP

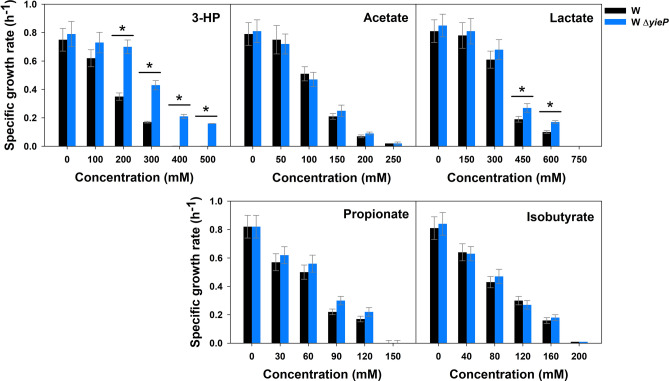

To determine the specificity of acid-tolerance improvement by yieP knock-out (i.e., whether the improvement is limited to 3-HP only or extended to other organic acids), wild-type E. coli W and its ΔyieP mutant were grown in the presence of C2–C4 weak organic acids (Fig. 1). Because the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) at which cell growth stops is different for each acid29,30, the range of acid concentration tested was varied as follows: 1–500 mM for 3-HP, 0–250 mM for acetate, 0–750 mM for lactate, 0–150 mM for propionate, and 0–200 mM for isobutyrate. For 3-HP, it has been confirmed that yieP deletion effectively improves tolerance27; the yieP deletion mutant could grow up to 500 mM, while the wild-type counterpart stopped its growth at < 400 mM. On the other hand, for the rest of the C2–C4 acids, the yieP deletion showed only a marginal or negligible improvement of tolerance. In another experiment, we added yeast extract (YE) at 0.5 g/L to the culture medium to examine whether 3-HP tolerance conferred by yieP deletion is masked by YE (Supplementary Fig. S2). Yeast extract significantly improved the tolerance in both the wild-type and ΔyieP mutant strains. However, the ΔyieP mutant still grew better than the wild-type in the presence of 3-HP, and the difference became more significant as the 3-HP concentration increased. In summary, the deletion of yieP increased the tolerance specifically against 3-HP, regardless of the presence of yeast extract in the culture medium.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of microbial growth by various organic acids. E. coli W and its ΔyieP mutant were grown in the M9 minimal medium with different organic acids: 3-HP, acetate, lactate, propionate, and isobutyrate. The concentration of each organic acid was varied within the specific respective ranges. Symbols: wild-type E. coli W (black bar), E. coli W ΔyieP (blue bar). Asterisk (*) indicates the significant difference (p < 0.05).

Transcriptome analysis reveals possible 3-HP tolerance mechanisms

To identify the genes and operons affected by the yieP deletion and to obtain insight into the possible molecular mechanisms behind the improved 3-HP tolerance, genome-wide transcriptomic analyses were performed for both the wild-type and ΔyieP mutant of E. coli W during the growth in M9 minimal medium (Supplementary Fig. S3). The effect of yieP deletion and 3-HP addition was elucidated by comparing the gene expression profiles among WΔ( +), W( +), WΔ(−) and W(−) (note that WΔ and W represent the mutant E. coli W ΔyieP and wild-type E. coli W, respectively; ‘ + ’ and ‘−’ in the parentheses indicate the presence and absence of 100 mM of 3-HP in the culture medium, respectively). When cells were cultured in the absence of 3-HP, expression of 279 genes (5.3% of total genes) was significantly altered by the yieP deletion (log2(fold change) > 1 and p value < 0.05). The number of alterations was 1.5-times higher when 3-HP was present in the culture medium (411 genes, 7.8% of total genes). Comparison between W( +) and W(−), showed differential expression in a total of 676 genes (13.0%), out of 5195 genes; among which, 274 genes (5.3%) were up-regulated while 402 genes (7.1%) were down-regulated (Supplementary Fig. S3). On the other hand, the comparison between WΔ( +) and WΔ(−) showed differential expression in a total of 442 genes (8.4%); 215 genes (4.1%) were up-regulated, while 227 genes (4.4%) were down-regulated (Supplementary Fig. S3). Hierarchical clustering of differentially expressed genes from the RNA-seq revealed that the transcriptomic variation by removal of yieP was more significant than that by 3-HP supplementation (Supplementary Fig. S3).

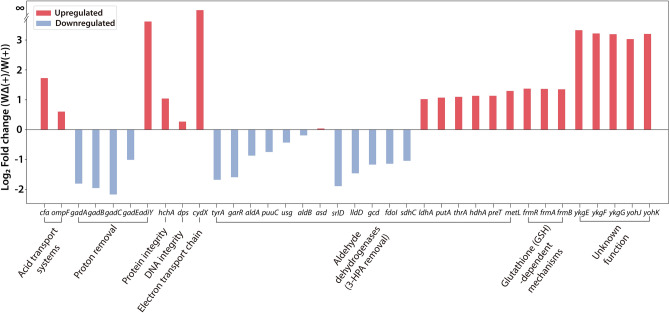

Although the yieP deletion is highly specific to 3-HP, the ‘general’ acid-resistance mechanisms should appear because 3-HP is an acid. Additionally, the general acid-resistance mechanisms should contribute to 3-HP tolerance to a certain extent in the yieP deletion mutant. Therefore, genes known to be related with the general acid-resistance responses were analyzed in the following four categories: (1) acid transport (reduction of influx and activation of efflux); (2) proton removal; (3) maintenance of integrity/activity of proteins, and nucleic acids; and, (4) electron transport chain (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. S4). In the yieP deletion strain, the expression levels of cfa (cyclopropane fatty acyl phospholipid synthase) and ompF (outer-membrane porin F) were up-regulated upon 3-HP addition. On the other hand and contrary to our expectation, the primary glutamate-dependent acid-resistant (GDAR) system, including transcription regulator gadE and its regulon genes gadA and gadBC, showed reduced RNA levels in the yieP deletion strain. However, the transcription factor adiY for the arginine-dependent response system (ADAR) was significantly up-regulated (12.3-fold). The hchA gene encoding the Hsp31 molecular chaperone for protein stabilization was also significantly up-regulated in ΔyieP mutant. A similar up-regulation was also observed for cydX which encodes for cytochrome bd-I ubiquinol oxidase subunit, a gene involved in the electron transport chain. In summary, many genes responsible for ‘general’ acid-resistant mechanism were up-regulated by yieP deletion, except GDAR genes which were down-regulated.

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed genes upon yieP knock-out. Genes for several ‘general’ acid-resistance responses and/or unknown functions were differentially expressed as consequence of the yieP deletion. Red and blue indicate up-regulation and down-regulation by yieP deletion, respectively. The Y-axis is the log2(fold change) between ΔyieP and the wild-type in the presence of 3-HP, and the X-axis indicates the gene names and their functions.

For the ‘3-HP-specific’ or ‘anion-specific’ resistance mechanisms31, expression of aldehyde dehydrogenases and glutathione (GSH)-dependent dehydrogenases was examined (Fig. 2). In the ΔyieP mutant, among a total of 18 genes encoding (putative) aldehyde dehydrogenases, 7 genes were up-regulated whereas 11 other genes were down-regulated. It is noted that the frmRAB operon, known to be associated with a glutathione (GSH)-dependent detoxification mechanism and reported to be up-regulated by 3-HP in a previous study23, was up-regulated by 2.90-fold by ΔyieP. To identify other possible ‘3-HP-specific’ resistance mechanisms, the genes with unknown functions but showing highly differential expression were further screened and scrutinized. Two operons, ykgEFG and yohJK, drew our attention because of a significant up-regulation (~ tenfold) by the yieP deletion. The yieP gene is a less-characterized transcription factor; thus, functionally-unknown genes can be highly relevant.

ChIP-exo enables systems-level reconstruction of YieP regulatory network

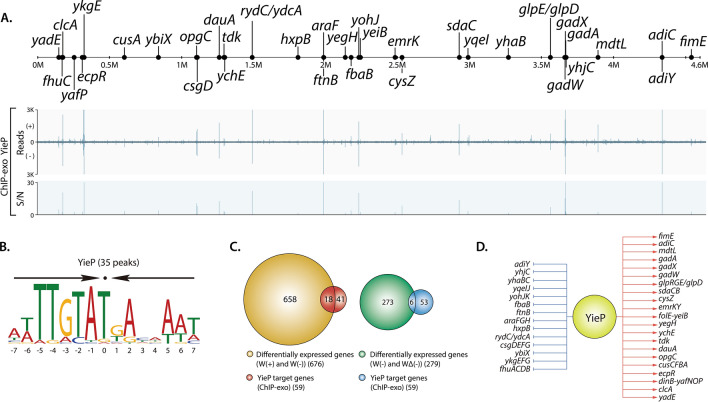

RNA-seq analysis identified the genes and operons that were affected by 3-HP and yieP deletion, but they were too many for functional studies. Another useful genome-wide tool for identification of genes/operons regulated by a transcription factor such as YieP, is the ChIP-exo analysis32,33. According to a recent ChIP-exo study on E. coli K-12 MG1655, there exist ~ 23 binding sites for YieP28. Here, we attempted to analyze YieP regulon in E. coli W by comparing ChIP-exo data and RNA-seq data. Note that the ChIP-exo data for E. coli MG1655 was used instead of that for E. coli W. The reason for that is because E. coli K-12 MG1655 has the most comprehensive knowledge on the transcriptional regulatory network, and ChIP-exo experimental protocol, ready to be used, was set up for that particular strain. On the other hand, genomic comparison showed that these two strains shared over 84.1% of the genes (Supplementary Fig. S5) and, more importantly, they had the same sequences for all the YieP target sites.

The ChIP-exo analysis for E. coli K-12 MG1655 with the addition of 3-HP revealed 33 YieP binding sites on the genome-scale (Fig. 3A). Among them, 12 binding sites were located in the intragenic regions, and 21 were in the intergenic regions. Integration of the identified binding sites by ChIP-exo, transcriptomic profiling by RNA-seq and operon structures known thus far34,35 revealed the presence of 33 transcriptional units (TUs) regulated by YieP, which contain a total of 59 genes. A sequence-motif analysis of the YieP binding sites showed the presence of a palindromic sequence: atTTGTaTGAcaAAT (capital characters indicating information content > 1 bit) (Fig. 3B). This palindromic sequence motif suggests that YieP might work as a dimeric conformation. Among the 59 genes belonging to the 33 YieP regulons, a total of 33 target genes were up-regulated, and the remaining 26 were down-regulated (Fig. 3D). Notably, six genes (ykgEFG, yohJK, and adiY) in 3 TUs were down-regulated by YieP with high-log2(fold change) as: < 4.8, 5.4, and 2.2-fold, respectively. This regulatory mode of YieP is consistent with the previous study28.

Figure 3.

Genome-wide identification of YieP regulon. (A) An overview of YieP-binding profiles across the genome of E. coli K-12 MG1655 cultured in the presence of 3-HP. (B) The sequence motif for YieP transcription factor. Arrows above the motif indicate the palindromic sequence. (C) Comparison of ChIP-exo result and gene expression profile to distinguish direct and indirect regulatory effects for YieP regulon genes. (D) Reconstruction of YieP regulon genes. The red and blue arrows indicate activation and suppression, respectively.

To minimize and finalize the list of genes for detailed functional studies, the 676 target genes suggested by the RNA-seq and 59 target genes indicated by the ChIP-exo analysis, respectively, were further curated. Five categories, individually or in combinations, were looked into for this purpose, as follows (Supplementary Fig. S6): (1) difference between E. coli W and E. coli BL21(DE3) (notice that, according to our previous study27, BL21(DE3) did not show tolerance improvement by the yieP deletion), (2) high-fold change in gene expression caused by the yieP deletion, (3) general acid-resistance mechanisms, (4) genes for membrane synthesis, and (5) genes with unknown functions. For the first category, the DNA sequences of TUs which are presumably under the control of YieP in E. coli BL21(DE3) and E. coli W or E. coli K-12 MG1655 were compared, and the 2 operons, ykgEFG, and sdaCB, were chosen due to the difference in their promoter sequences (Supplementary Fig. S7). In the second category, for the highly up-regulated (~ tenfold) genes resulted by the yieP deletion, three operons, ykgEFG, yohJK and adiY, were chosen. In the third category, for the general acid-resistant genes, gadX and adiY, which are known to be complicated acid-resistant regulatory proteins, were selected15,18. In the fourth category, the rydC gene, encoding a small RNA and known to be related to the biosynthesis of putative transporters and curli, was chosen36. Finally, in the fifth category, the ydcA gene, the function of which is unknown, was selected. The ykgEFG and yohJK can also be classified as the fifth category, although chosen in the second category. Altogether, a total of 11 genes in 7 operons were selected as prospective candidates for further investigation.

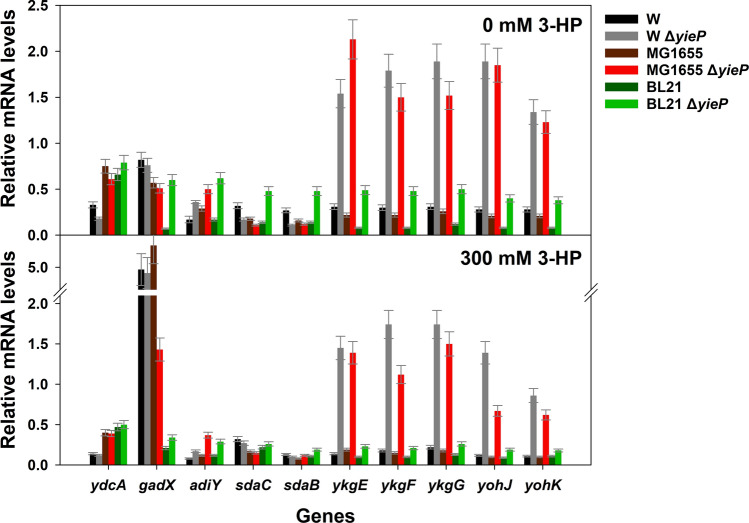

Transcription of YieP target genes varies in multiple E. coli strains

Knock-out of yieP improved 3-HP tolerance in several E. coli strains, including E. coli W, E. coli K-12 MG1655, E. coli K-12 W3110, and E. coli B, but not in E. coli BL21(DE3)27. It was postulated that the phenotypic difference of E. coli BL21(DE3) might be originated from differential gene expression of the YieP regulons. For clarification of this hypothesis, functional analyses of the 11 target genes with their deletion and over-expression are needed, which is time-consuming and laborious. Therefore, before the functional analyses, the selected target genes were examined by RT-qPCR experiments in the three E. coli strains, W, K-12 MG1655, and BL21(DE3), and their three corresponding ΔyieP mutants, respectively. Ten genes among the 11, except for rydC the length of which is too short (64 bp), were analyzed (Fig. 4). For E. coli W, RT-PCR analysis showed a good correlation with FPKM values from the RNA-seq analysis (correlation coefficient was 0.71) (Supplementary Fig. S8). Among the 10 target genes, the two operons ykgEFG and yohJK exhibited a highly enhanced transcription by yieP deletion, regardless of 3-HP. However, in E. coli BL21(DE3), the fold change of these two operons was much lower (~ 2.5-fold) than in the other E. coli strains (~ 6 to 10-fold). The adiY gene, a transcription regulator for the arginine-dependent acid-resistant (ADAR) system, was up-regulated by ~ twofold in all of the ΔyieP mutants, unlike the corresponding wild-type strains. Expression of the regulator related to the glutamate-dependent acid-resistant system, gadX, was not affected by the yieP deletion, but the addition of 3-HP to the culture medium up-regulated its transcription level as high as sixfold in E. coli W and E. coli K-12 MG1655. Transcription of the remaining genes (ydcA and sdaCB) was not affected by the yieP deletion. These results expand our knowledge on the regulatory role of yieP from E. coli W to other E. coli strains, especially by demonstrating that YieP down-regulates expression of multiple genes, including ykgEFG, yohJK, and adiY. These genes are expected to play important roles in linking ΔyieP genotype to 3-HP tolerant phenotype.

Figure 4.

Relative mRNA transcription levels of 10 selected genes. Transcription was determined in E. coli W, E. coli K-12 MG1655, E. coli BL21(DE3), and their corresponding ΔyieP mutants grown with and without 300 mM 3-HP (upper and lower panel, respectively). The housekeeping sigma factor, rpoD, was used as reference. Symbols: E. coli W (black bar), E. coli W ΔyieP (gray bar), E. coli K-12 MG1655 (dark-brown bar), E. coli K-12 MG1655 ΔyieP (red bar), E. coli BL21 (DE3) (dark-green bar), E. coli BL21(DE3) ΔyieP (light-green bar).

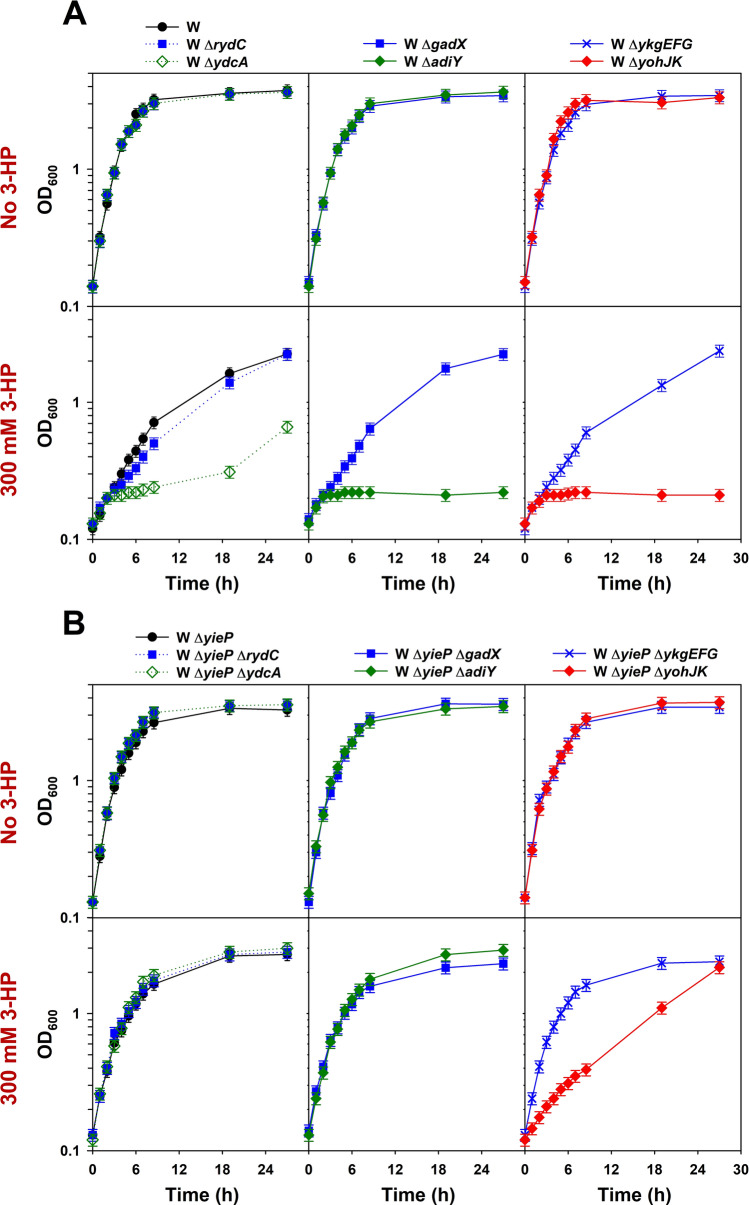

yohJK operon, a member of the YieP regulon, is essential for ‘3-HP-specific’ tolerance

In order to evaluate functional importance, six operons (rydC, ydcA, gadX, adiY, ykgEFG, and yohJK, except sdaCB) were subjected to deletion experiments. Two series of deletion mutants were developed: the first from the wild-type E. coli W, and the second from its ΔyieP mutant, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). The growth of these mutants (12 strains in total) was examined in the modified M9 minimal medium (Fig. 5A,B). When 3-HP was absent, the mutations did not disturb cell growth for either the wild-type (for yieP) strains or their ΔyieP mutants. However, when 3-HP (300 mM) was added, the growth of the three mutants in the first series (ydcA, adiY, and yohJK), developed from the wild-type E. coli W, was severely reduced (Fig. 5A). On the other hand, in the second series of mutants, those developed from the ΔyieP mutant, 3-HP toxic effect was much reduced: entirely in the case of the ydcA and adiY mutants, and partially in the case of the yohJK mutant (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Identification of genes/operons conferring 3-HP tolerance. Six selected genes/operons were individually deleted from E. coli W (A) and E. coli W ΔyieP (B). All the mutants were grown in the modified M9 minimal medium. The 300 mM 3-HP was supplemented to the culture medium when indicated. Symbols: E. coli W (wild-type and ΔyieP; black circles, solid line), ΔrydC (blue closed rectangles, dotted line), ΔydcA (green open diamonds, dotted line), ΔgadX (blue closed rectangles, solid line), ΔadiY (green closed diamonds, solid line), ΔykgEFG (blue crosses, solid line), and ΔyohJK (red closed diamonds, solid line).

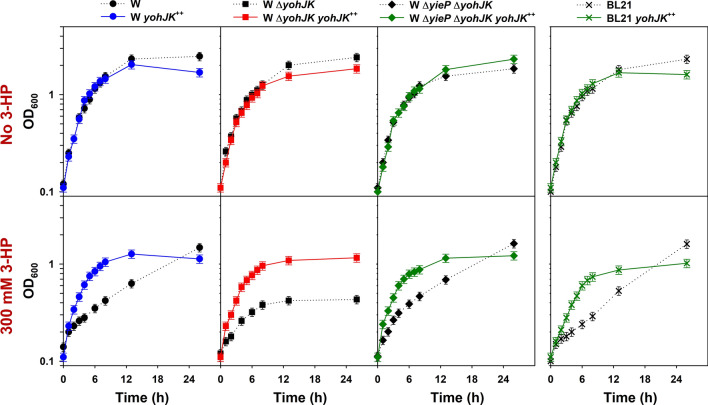

Because the yohJK deletion overrides the yieP deletion in showing 3-HP tolerance, overexpression of yohJK on 3-HP tolerance was also investigated (Fig. 6). The yohJK genes were cloned into the low-copy pACYC plasmid under the tetracycline-inducible promoter (Ptet). The expression of yohJK was induced (by adding 200 ng/mL of anhydrotetracycline) for one hour before adding 300 mM 3-HP. With overexpression of yohJK (designated yohJK++), the wild-type E. coli W exhibited an improved tolerance to 3-HP (Fig. 6). This indicates that the overexpression of yohJK alone, without the yieP deletion, can confer 3-HP tolerance to E. coli W. However, the tolerance level in the yieP deletion mutant was not further enhanced by overexpression of yohJK (Supplementary Fig. S10). The role of yohJK was also confirmed by complementary expression of yohJK in both E. coli W ΔyohJK and E. coli W ΔyiePΔyohJK: both the strains exhibited similar tolerance to 3-HP as E. coli W yohJK++. Interestingly enough, over-expression of yohJK improved the 3-HP tolerance in E. coli BL21(DE3), which did not show improvement at all by the deletion of yieP. It is likely that the lower up-regulation of yohJK in E. coli BL21(DE3) (~ 2.5 fold) than in other E. coli strains (~ 6 to 10-fold) is responsible for not acquiring 3-HP tolerance by the yieP deletion in the former strain. It will be interesting to overexpress yohJK in other microbes in order to improve their tolerance to 3-HP.

Figure 6.

Overexpression of yohJK in E. coli strains. Recombinant E. coli strains were grown in the M9 minimal medium containing 50 mg/L kanamycin. 3-HP was added to the culture medium when indicated. “yohJK++” indicates the recombinant strains harboring pACYC-Ptet-yohJK; otherwise, strains harbor the pACYC empty-plasmid. Symbols: E. coli W (black circles, dotted line), E. coli W yohJK++ (blue circles, solid line), E. coli W ΔyohJK (black rectangles, dotted line), E. coli W ΔyohJK yohJK++ (red rectangles, solid line), E. coli W ΔyieP ΔyohJK (black diamonds, dotted line), E. coli W ΔyieP ΔyohJK yohJK++ (green diamonds, solid line), E. coli BL21(DE3) (black crosses, dotted line), E. coli BL21(DE3) yohJK++ (green crosses, solid line).

yohJK operon encodes for 3-HP transporter in E. coli W

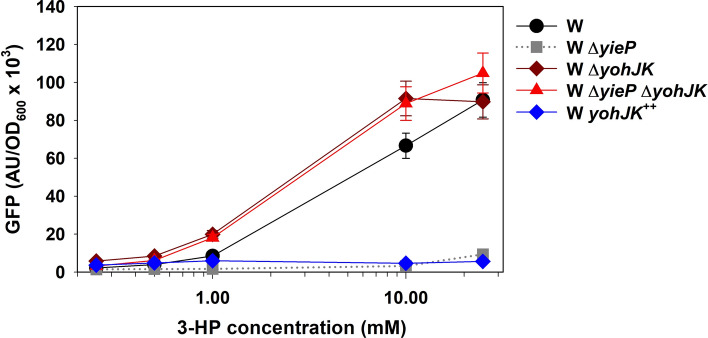

The results of this study thus far strongly suggest that the improvement of 3-HP tolerance caused by the yieP deletion is mostly mediated by the up-regulation of yohJK. However, the exact mechanism behind the tolerance improvement remains elusive. According to EcoCyc, yohJ and yohK are predicted to be inner-membrane proteins with four and six transmembrane domains, respectively37,38, suggesting that the protein(s) are transporter(s) for 3-HP. To study their physiological roles, we measured intracellular 3-HP concentration by 3-HP responsive biosensor. The biosensor module employs a LysR-type transcription factor (MmsR) which is specifically activated by 3-HP and induces the expression of green fluorescence protein (GFP) under the control of PmmsA promoter39 (Supplementary Fig. S11 and S12). Because the one (BS-P) previously reported was not sensitive in E. coli, a new biosensor module (BS-E) having a higher expression of MmsR was constructed (see Materials and Method). When tested in the modified M9 minimal medium, the strain with the new BS-E module gave ~ threefold higher GFP signal than the one with its predecessor BS-P. Both BS-P and BS-E showed increased GFP intensity up to 25 mM 3-HP in a dose-dependent manner.

The new biosensor module (BS-E) was introduced into five E. coli W strains such as wild type, two single deletion mutants for each of yieP and yohJK, a double deletion mutant for both yieP and yohJK, and an yohJK-overexpressed strain (yohJK++), and the GFP signals were compared among the five strains in varying 3-HP concentrations (from 0 to 25 mM). The GFP intensity was determined 6 h after inoculation (Fig. 7). The intensity increased in the following order (notably, up to 10 mM 3-HP): yohJK++ ≤ ΔyieP < W (wild-type) < ΔyiePΔyohJK ≤ ΔyohJK. It is noticed that the yieP deletion mutant (where yohJK is upregulated according to RT-PCR shown in Fig. 4) and the yohJK-overexpressed strain (yohJK++), showed a dramatically reduced GFP intensity compared to that of the wild type. On the other hand, the yohJK deletion in both wild-type and ΔyieP mutant substantially increased the GFP signal. These results indicate that the intracellular 3-HP concentration is significantly reduced when yieP is deleted or yohJK is overexpressed, and support our hypothesis that the physiological function of the yohJK genes is involved with the excretion or removal of 3-HP from the cell. Because yohJK encode for integral transmembrane proteins and their overexpression reduces intracellular 3-HP concentration greatly, the protein(s) is likely a novel 3-HP exporter.

Figure 7.

Effect of ΔyieP , ΔyohJK and yohJK++ on GFP-intensity of 3-HP biosensors. Five E. coli W strains (W, W ΔyieP, W ΔyohJK, W ΔyiePΔyohJK, and W yohJK++) harboring the BS-E biosensor module were grown in the modified M9 minimal medium containing varying 3-HP concentration (0–25 mM). GFP was measured 6 h after inoculation. Symbols: E. coli W (black circles); W ΔyieP (gray rectangles); W ΔyohJK (dark-red diamonds); W ΔyiePΔyohJK (red triangles); W yohJK++ (blue diamonds).

Discussion

We wanted to study the mechanism how the yieP deletion improves 3-HP tolerance and use the information to develop better 3-HP tolerant strains. Without knowing the physiological functions of YieP, the first thing that should be done was screening the candidate genes and operons affected by YieP or its deletion. Although YieP was suggested as a transcription factor28, the possibility to conduct other physiological functions was not fully eliminated a priori. The specificity experiment with different organic acids was conducted as the first step to search the uncovered mechanism(s), and it was found that the effect of the yieP deletion was highly specific to 3-HP. Consequently, the ‘3-HP specific’ mechanism was targeted for further investigations (Fig. 1).

The combination of transcriptomics, mapping of transcriptional binding sites, genomics, and physiological study was an efficient approach for elucidation the role of yieP deletion. Genome-wide transcriptomic profiling and ChIP-exo analyses are useful when a global regulator is studied for its function28. In this study, these two, genome-wide approaches significantly narrowed down the number of candidates from the initial 411 genes to 59 genes (Fig. 3). Comparison of genomic sequences (Supplementary Fig. S7) and/or transcription levels (Fig. 4) between E. coli BL21(DE3), that was insensitive to the yieP deletion, and other E. coli strains also helped the selection of target genes. Through all these sequential efforts (Supplementary Fig. S6), the number of operons to be studied could be minimized to six (rydC, ydcA, gadX, adiY, ykgEFG, and yohJK) for the functional analyses, i.e., knockout and/or overexpression experiments.

According to functional analyses, the deletion of ydcA or adiY made cells sensitive to 3-HP, but the sensitivity was overridden by the yieP deletion completely (Fig. 5). The positive transcriptional factor, adiY, has been suggested to regulate both the arginine- and glutamate-dependent acid-resistant systems40. Similarly, the ydcA protein has also known to be related with acid-resistance. It was reported that the expression of ydcA, under the control of YdcI, was up-regulated in acidic condition (pH 5.0) (Supplementary Fig. S9)28,41. However, the involvement of AdiY and YdcA in 3-HP tolerance is not clear. The deletion of yohJK also made cells sensitive to 3-HP and, furthermore, the sensitivity was not overridden by the yieP deletion, differently from the ydcA or adiY deletion (Fig. 5). In addition, the overexpression of yohJK without yieP deletion could improve the 3-HP tolerance as much as the yieP deletion (Supplementary Figs. S6 and S10). This indicates the effect of yieP deletion on 3-HP tolerance, in a large extent, is mediated by the yohJK overexpression. The function of yohJ and yohK in E. coli has not been revealed previously, but according to EcoCyc, yohJ and yohK, both are inner-membrane proteins with four and six transmembrane domains, respectively37. Further study using biosensor revealed that the up-regulation of yohJK significantly reduces intracellular 3-HP concentration while their deletion increases its level, strongly suggesting they encodes for 3-HP-specific exporter(s) (Fig. 7). If YohJK is a 3-HP-specific transporter, it is understandable why the yohJK overexpression, either indirectly by yieP deletion or directly by its episomal expression, has specifically improved 3-HP tolerance. Thus far, no 3-HP-specific transporter has been reported, and further, no functional study on YohJK has been conducted. More studies to understand how YohJK work, i.e., whether both YohJ and K function together or individually, they are associated with other membrane proteins, they utilize energy for 3-HP transport, they can improve 3-HP tolerance in other microorganisms, etc. should be followed.

In conclusion, by combined studies of microbial growth, RNA-seq, ChIP-exo and functional analyses of genes and operons, we could identify novel membrane proteins YohJK which improve 3-HP tolerance in E. coli W. YohJK efficiently reduced intracellular 3-HP concentration and should be useful in strain development for achieving high 3-HP titer. In addition, the procedures described in this manuscript should be useful in identifying genes and operons which are affected by a global regulator, the physiological functions of which has not known. Biochemical and physiological aspects of the new putative exporter(s) YohJK and their application to other microbes are under study.

Methods

Strains, culture conditions, and materials

Escherichia coli W (ATCC 9637) and E. coli K-12 MG1655 were obtained from Korean Collection for Type Cultures (KCTC, South Korea). E. coli BL21 (DE3) was purchased from Novagen (Darmstadt, Germany). All of the bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table S1. Highly-pure 3-HP sodium salt (> 99%) was provided by Noroo Holdings Ltd, Seoul, Korea. Glycerol, lactic acid and propionic acid were acquired from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). All of the other chemicals were purchased from Junsei, Japan.

Bacterial cells were cultured in modified M9 minimal medium with glycerol as the carbon source, unless indicated otherwise. The modified M9 minimal medium contains: MgSO4·7H2O, 0.25 g/L; NaCl, 1.0 g/L; NH4Cl, 0.5 g/L; yeast extract, 0.5 g/L (optional); potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 100 mM; and glycerol, 100 mM. Cells were cultured aerobically in a 125 mL flask (working medium, 10 mL) at 37 °C at an agitation speed of 200 rpm27. Organic acids were prepared as 10 M stock solutions, neutralized by NaOH and added to the culture medium as needed. To monitor growth, the bacterial cell density (cell OD600) was determined at 600 nm by UV/Vis spectrophotometry (Lambda 265, PerkinElmer, CT, USA). All experiments were conducted in duplicate, the results were expressed by means value.

Genome-wide transcriptome analysis with RNA-seq

For RNA-seq expression profiling, total RNA, including small RNAs, was isolated using the NucleoSpin RNA XS (Macherey–Nagel, Germany). The sequencing library was prepared by random fragmentation of cDNA samples, followed by 5′ and 3′ adapter ligation using TrueSeq stranded mRNA kits (Microbe). Sequencing was performed on a Hiseq 4000 sequencer obtained from Marcrogen Inc. (Korea). RNA-seq experiments were performed in biological duplicate.

For the processing of RNA-seq output, sequence reads generated from RNA-seq were mapped onto the reference genome (NC_017635.1) using Bowtie with the maximum insert size of 1000 bp along with two maximum mismatches after trimming 3 bp at 3′ ends42. SAM files generated from Bowtie were then used for Cufflinks (https://cufflinks.cbcb.umd.edu) and Cuffdiff to calculate fragments per kilobase of exon per million fragments (FPKM) and differential expression, respectively. Cufflinks and Cuffdiff were run using default options with the library type of dUTP RNA-seq by the default normalization method (classic-fpkm). From the Cuffdiff output, genes showing differential expression with log2-fold change > 1.0 and a p value < 0.05 were considered as differentially expressed genes. Genome-scale data were visualized using MetaScope (https://sites.google.com/view/systemskimlab/software).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation with exonuclease (ChIP-exo) to identify YieP binding sites

In order to execute ChIP-exo experiments, a multi-Myc-tag peptide sequence was added to the C-terminal of yieP using the λ red-mediated site-specific recombination system43. The resultant recombinant strain, E. coli K-12 MG1655 yieP-8myc, was cultured in fresh M9 minimal medium (100 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.0, 1 g/L NaCl, 1 g/L NH4Cl, 2 mM MgSO4) with 100 mM glycerol as the sole carbon source; 1 mL of trace element solution (100X) containing 1 g/L EDTA, 29 mg/L ZnSO4·7H2O, 198 mg/L MnCl2·4H2O, 254 mg/L CoCl2·6H2O, 13.4 mg/L CuCl2 and 147 mg/L CaCl2 was also supplemented to the culture medium. When the effect of 3-HP was tested, 100 mM 3-HP was added to the culture medium. The cells were cultured at 37 °C and 200 rpm and harvested in the mid-log phase (~ 0.3 OD600) for further experimentation.

A ChIP-exo experiment was performed following the procedures previously described33. In brief, to identify the in vivo YieP binding map, DNA bound to YieP from formaldehyde-cross-linked E. coli cells was isolated by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) with the specific antibodies that specifically recognize Myc-tag (9E10, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Texas, USA) and Dynabeads Pan Mouse IgG magnetic beads (Invitrogen, CA, USA), followed by stringent washing as described previously34. ChIP materials (chromatin-beads) were used to perform on-bead enzymatic reactions of the ChIP-exo method33,44. Briefly, the sheared DNA of the chromatin-beads was repaired by the NEBNext End Repair Module (New England Biolabs, MA, USA) followed by the addition of a single dA overhang and ligation of the first adaptor (5′-phosphorylated) using the dA-Tailing Module (New England Biolabs) and the NEBNext Quick Ligation Module (New England Biolabs), respectively. Nick repair was performed by using PreCR Repair Mix (New England Biolabs). Lambda exonuclease- and RecJf nuclease-treated chromatin were eluted from the beads, and overnight incubation at 65 °C reversed the protein-DNA cross-link. RNAs- and Proteins-removed DNA samples were used to perform primer extension and second adaptor ligation, respectively, with the following modifications. The DNA samples incubated for primer extension, as described previously, were treated with dA-Tailing Module (New England Biolabs) and NEBNext Quick Ligation Module (New England Biolabs) for second adaptor ligation33. The DNA sample purified using the GeneRead Size Selection Kit (Qiagen) was enriched by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (New England Biolabs). The amplified DNA samples were purified again with the GeneRead Size Selection Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and quantified using the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Life Technologies). The quality of the DNA sample was checked by running the Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit using Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, CA, USA). Sequencing was performed on a Hiseq 4000 sequencer at Marcrogen Inc. (Korea). Each modified step was also performed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. The ChIP-exo experiments were performed in biological duplicate.

In order to process the ChIP-exo output, ChIP-exo analysis was performed according to the method reported previously28. The sequence reads of ChIP-exo were mapped onto the reference genome (NC_000913.2) using the Bowtie with default options to generate SAM output files. To reduce false-positive peaks, peaks with a signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio < 1.5 were removed. The noise level was set to the top 5% of signals at genomic positions, because the top 5% makes a background level in a plateau, and the top 5% intensities from each of the ChIP-exo replicates across conditions correlate well with the total number of reads. Then, each peak was assigned to the nearest gene. Genome-scale data were visualized using MetaScope.

A YieP-binding motif analysis was performed using the MEME tool from the MEME software suite45. YieP-binding DNA sequences were extracted from the reference sequence (NC_000913.2). The sequence of each binding site was extended by 20 bp at each end to allow for adjacent sequences to be included in the analysis. The default setting was used, except for the width parameter, which was fixed to 20 bp.

Homologous recombination for gene disruption

Mutants with multiple knock-outs were well developed using a method of scarless homologous recombination reported elsewhere11. In brief, the upstream and downstream fragments of a target gene were amplified using PCR, and overlapping PCR was performed to combine the two fragments. The combined fragment was digested with two restriction enzymes XbaI and XhoI, and ligated into the pKOV vector. Afterwards, the resulting plasmid was introduced to the E. coli strains and used to delete a target gene by homologous recombination11. The plasmids for gene deletion and resultant mutants are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Real-time PCR for quantification of mRNA expression levels

The procedure for measuring mRNA level was described before46. Briefly, E. coli was grown in modified M9 minimal medium until reaching the exponential phase. Cells were harvested in RNase-free vials and centrifuged for 10,000 rpm for 10 min to obtain the cell pellet. Total RNA was extracted using an RNA isolation kit (Macherey–Nagel, Germany). First-strand cDNA was synthesized using a SuperScript III first-strand cDNA synthesis system (Invitrogen, USA). RT-PCR was performed by the StepOne real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA). The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: denaturation, 1 cycle of 95 °C for 30 s; and amplification, 40 cycles of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 30 s. The relative mRNA level was calculated using the ΔCt method. The housekeeping gene rpoD encoding sigma factor 70 was used as a reference.

Overexpression of yohJK operon

The yohJK operon of E. coli W (GenBank: yohJ, ADT75777.1, and yohK, ADT75778.1) was cloned into a low-copy-number plasmid pACYC under the tetracycline-inducible promoter. The sequences of the tetracycline promoter and yohJK operon were amplified using PCR, and overlapping PCR for combination of the two fragments followed. Afterwards, the overlapped fragment was digested using EcoRI and BamHI restriction enzymes and ligated with linearized pACYC to obtain the plasmid pACYC-Ptet-yohJK. The resultant plasmid was then introduced into E. coli host strains for further experimentation. Kanamycin (Km) at 50 mg/L was added to the culture medium for plasmid maintenance, and 200 ng/mL of anhydrotetracycline was used for induction of yohJK.

Development of GFP-based 3-HP biosensor for comparison of intracellular 3-HP in E. coli W strains

Briefly, we modified the 3-HP biosensor previously developed for P. denitrificans ATCC 13867 (designated as BS-P) and applied it for E. coli W39. The 3-HP inducible promoter (PmmsA) and 10 amino acids of its downstream gene (mmsA) from P. denitrificans ATCC 13867 was fused with gfp reporter gene. The mmsR gene, encoding for positive transcription factor for PmmsA promoter, was expressed under the control of IPTG inducible promoter T5. All the DNA fragments were assembled using overlapping PCR to make a T5-mmsR_PmmsA-gfp cassette. The obtained cassette was digested using BamHI and HindIII restriction enzymes and ligated with linearized pQE80L plasmid (Supplementary Fig. S11). The resulted biosensor module was named as BS-E. Under the control of 3-HP inducible promoter PmmsA, the expression of GFP is dependent on the levels of intracellular 3-HP.

Whole-cell fluorescence assay

In order to compare the level of intracellular 3-HP between E. coli W strains, the recombinant strains harboring the plasmid pQE80L_T5-mmsR_PmmsA-gfp were inoculated in the modified M9 minimal medium. The inducers such as IPTG and 3-HP were added into the culture medium. Samples were taken at 6-h after inoculation for fluorescence and OD600 measurement. The protocol for GFP measurement was described somewhere else47. Synergy H1 microplate reader (BioTek instruments, USA) using 486-nm excitation and 535-nm emission filters was used to measure both fluorescence and OD600. The measured fluorescence values were normalized to OD600 to obtain specific fluorescence (AU/ OD600).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Advanced Biomass R&D Centre (ABC) of the Global Frontier Project funded by the Ministry of Science, ICT and Future Planning (ABC-2011-0031361), KAIST, Republic of Korea. It was also supported by the BK21 Plus Program for Advanced Chemical Technology at Pusan National University.

Author contributions

T.P.N.-V. conducted experiment related with growth, biosensor, RNA-seq and wrote manuscript; S.K. conducted ChIP-exo experiment, processed computational analysis and wrote manuscript; H.R. developed 3-HP biosensor and performed biosensor experiment; J.R.K., D.K., and S.P. advised ideas and revised manuscript.

Data availability

The dataset of RNA-seq and ChIP-exo has been deposited to GEO under the accession number GSE129317 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE111095, the secure token to allow a review of record GSE129317 is qdqlyygkvvgzxaf).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Thuan Phu Nguyen-Vo and Seyoung Ko.

Contributor Information

Donghyuk Kim, Email: dkim@unist.ac.kr.

Sunghoon Park, Email: parksh@unist.ac.kr.

Supplementary information

is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41598-020-76120-3.

References

- 1.Werpy T, et al. Top Value Added Chemicals From Biomass. Washington DC: Department of Energy; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seok JY, et al. Directed evolution of the 3-hydroxypropionic acid production pathway by engineering aldehyde dehydrogenase using a synthetic selection device. Metab. Eng. 2018;47:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borodina I, et al. Establishing a synthetic pathway for high-level production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid in Saccharomyces cerevisiae via β-alanine. Metab. Eng. 2015;27:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sabet-Azad R, Sardari RRR, Linares-Pastén JA, Hatti-Kaul R. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from 3-hydroxypropionaldehyde by recombinant Escherichia coli co-expressing Lactobacillus reuteri propanediol utilization enzymes. Bioresour. Technol. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2014.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rathnasingh C, et al. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid via malonyl-CoA pathway using recombinant Escherichia coli strains. J. Biotechnol. 2012;157:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan EI, et al. Metabolic engineering of cyanobacteria for photosynthetic 3-hydroxypropionic acid production from CO2 using Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942. Metab. Eng. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar V, Ashok S, Park S. Recent advances in biological production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol. Adv. 2013;31:945–961. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kildegaard KR, et al. Evolution reveals a glutathione-dependent mechanism of 3-hydroxypropionic acid tolerance. Metab. Eng. 2014;26:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Z, et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for the production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glucose and xylose. Metab. Eng. 2017;39:151–158. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontrelli S, et al. Escherichia coli as a host for metabolic engineering. Metab. Eng. 2018;50:16–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Link AJ, Phillips D, Church GM. Methods for generating precise deletions and insertions in the genome of wild-type Escherichia coli: application to open reading frame characterization. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:6228–6237. doi: 10.1128/JB.179.20.6228-6237.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chun AY, Yunxiao L, Ashok S, Seol E, Park S. Elucidation of toxicity of organic acids inhibiting growth of Escherichia coli W. Biotechnol. Bioprocess. Eng. 2014;19:858–865. doi: 10.1007/s12257-014-0420-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sankaranarayanan M, Ashok S, Park S. Production of 3-hydroxypropionic acid from glycerol by acid tolerant Escherichia coli. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014;41:1039–1050. doi: 10.1007/s10295-014-1451-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warnecke T, Gill RT. Organic acid toxicity, tolerance, and production in Escherichia coli biorefining applications. Microb. Cell Fact. 2005;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seo SW, Kim D, O’Brien EJ, Szubin R, Palsson BO. Decoding genome-wide GadEWX-transcriptional regulatory networks reveals multifaceted cellular responses to acid stress in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:1–8. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hommais F, et al. GadE (YhiE): a novel activator involved in the response to acid environment in Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 2004;150:61–72. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26659-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tramonti A, De Canio M, Bossa F, De Biase D. Stability and oligomerization of recombinant GadX, a transcriptional activator of the Escherichia coli glutamate decarboxylase system. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta Proteins Proteomics. 2003;1647:376–380. doi: 10.1016/S1570-9639(03)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stim-Herndon KP, Flores TM, Bennett GN. Molecular characterization of adiY, a regulatory gene which affects expression of the biodegradative acid-induced arginine decarboxylase gene (adiA) of Escherichia coli. Microbiology. 1996;142:1311–1320. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-5-1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neely MN, Dell CL, Olson ER. Roles of LysP and CadC in mediating the lysine requirement for acid induction of the Escherichia coli cad operon. J. Bacteriol. 1994 doi: 10.1128/jb.176.11.3278-3285.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashiwagi K, Shibuya S, Tomitori H, Kuraishi A, Igarashi K. Excretion and uptake of putrescine by the PotE protein in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 1997 doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.10.6318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster PL. Stress responses and genetic variation in bacteria. Mutat. Res. Mol. Mech. Mutagen. 2005;569:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gajiwala KS, Burley SK. HDEA, a periplasmic protein that supports acid resistance in pathogenic enteric bacteria. J. Mol. Biol. 2000;295:605–612. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yung TW, Jonnalagadda S, Balagurunathan B, Zhao H. Transcriptomic Analysis of 3-hydroxypropanoic acid stress in Escherichia coli. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2016;178:527–543. doi: 10.1007/s12010-015-1892-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warnecke TE, et al. Rapid dissection of a complex phenotype through genomic-scale mapping of fitness altering genes. Metab. Eng. 2010;12:241–250. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dragosits M, Mattanovich D. Adaptive laboratory evolution—principles and applications for biotechnology. Microb. Cell Fact. 2013;12:1–17. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-12-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang J, Wu C, Du G, Chen J. Enhanced acid tolerance in Lactobacillus casei by adaptive evolution and compared stress response during acid stress. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2012;17:283–289. doi: 10.1007/s12257-011-0346-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nguyen-Vo TP, et al. Development of 3-hydroxypropionic-acid-tolerant strain of Escherichia coli W and role of minor global regulator yieP. Metab. Eng. 2019;53:48–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao Y, et al. Systematic discovery of uncharacterized transcription factors in Escherichia coli K-12 MG1655. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 doi: 10.1101/343913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiegand I, Hilpert K, Hancock REW. Agar and broth dilution methods to determine the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antimicrobial substances. Nat. Protoc. 2008;3:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gómez-García M, et al. Antimicrobial activity of a selection of organic acids, their salts and essential oils against swine enteropathogenic bacteria. Porc. Heal. Manag. 2019;5:32. doi: 10.1186/s40813-019-0139-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lipscomb TW, Lipscomb ML, Gill RT, Lynch MD. Metabolic engineering of recombinant E. coli for the production of 3-hydroxypropionate. Eng. Complex Phenotypes in Ind. Strains. 2012 doi: 10.1002/9781118433034.ch7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim D, et al. Systems assessment of transcriptional regulation on central carbon metabolism by Cra and CRP. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018 doi: 10.1093/nar/gky069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seo SW, et al. Deciphering fur transcriptional regulatory network highlights its complex role beyond iron metabolism in Escherichia coli. Nat. Commun. 2014 doi: 10.1038/ncomms5910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho B-KK, Kim D, Knight EM, Zengler K, Palsson BO. Genome-scale reconstruction of the sigma factor network in Escherichia coli: topology and functional states. BMC Biol. 2014;12:4. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-12-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D, et al. Comparative analysis of regulatory elements between Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae by genome-wide transcription start site profiling. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002867. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bak G, et al. Identification of novel sRNAs involved in biofilm formation, motility, and fimbriae formation in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2015;5:1–19. doi: 10.1038/srep15287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keseler IM, et al. The EcoCyc database: reflecting new knowledge about Escherichia coli K-12. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.UniProt UniProt: a worldwide hub of protein knowledge. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D506–D515. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nguyen NH, Kim JR, Park S. Development of biosensor for 3-hydroxypropionic acid. Biotechnol. Bioprocess Eng. 2019;24:109–118. doi: 10.1007/s12257-018-0380-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krin E, Danchin A, Soutourina O. Decrypting the H-NS-dependent regulatory cascade of acid stress resistance in Escherichia coli. BMC Microbiol. 2010 doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-10-273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jennings ME, et al. Characterization of the Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium ydcI gene, which encodes a conserved DNA Binding protein required for full acid stress resistance. J. Bacteriol. 2011 doi: 10.1128/JB.01335-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol. 2009;10:R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cho BK, Knight EM, Palsson B. PCR-based tandem epitope tagging system for Escherichia coli genome engineering. Biotechniques. 2006;40:67–72. doi: 10.2144/000112039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rhee HS, Pugh BF. ChIP-exo method for identifying genomic location of DNA-binding proteins with near-single-nucleotide accuracy. In: Ausubel FM, editor. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology, vol. 100. New York: Wiley; 2012. pp. 21.24.1–21.24.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bailey TL, et al. MEME Suite: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nguyen-Vo TP, Ainala SK, Kim J-R, Park S. Analysis and characterization of coenzyme B12 biosynthetic gene clusters and improvement of B12 biosynthesis in Pseudomonas denitrificans ATCC 13867. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2018;365:fny211. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fny211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Binder S, et al. A high-throughput approach to identify genomic variants of bacterial metabolite producers at the single-cell level. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R40. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-5-r40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset of RNA-seq and ChIP-exo has been deposited to GEO under the accession number GSE129317 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE111095, the secure token to allow a review of record GSE129317 is qdqlyygkvvgzxaf).