Abstract

BACKGROUND

Postpartum depression is a common mental illness in puerpera, with an incidence of approximately 3.5%-33.0% abroad, and the incidence of postpartum depression in China is higher than the international level, reaching 10.0%-38.0%. Providing effective nursing care in clinical nursing activities is one of the key points of obstetrical care. However, little research has been designed to investigate the positive role of home-based nursing in the prevention of postpartum depression .

AIM

To study the effect of home-based nursing for postpartum depression patients on their quality of life and depression.

METHODS

The clinical data of 92 patients with postpartum depression treated at our hospital were retrospectively analyzed. The patients were grouped according to the nursing methods used; 40 patients receiving basic nursing were included in a basic nursing group, and 52 receiving home-based nursing were included in a home-based nursing group. Depression and anxiety were evaluated and compared between the two groups. The estradiol (E2), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), and progesterone (PRGE) levels were measured.

RESULTS

The SAS and SDS scores of the home-based nursing group were significantly lower than those of the basic nursing group (P < 0.05). The E2 and 5-HT levels of the home-based nursing group were significantly higher than those of the basic nursing group, but the PRGE level was significantly lower than that of the basic nursing group. The GQOLI-74 scores (material, social, somatic, and psychological) and nursing satisfaction were significantly higher in the home-based nursing group (P < 0.05).

CONCLUSION

Postpartum depression through home-based nursing can effectively alleviate depression and improve the quality of life of patients, help modulate their serum E2, 5-HT, and PRGE levels, and improve their satisfaction with nursing care.

Keywords: Postpartum depression, Home-based care, Depression, Quality of life, Estradiol, Progesterone

Core Tip: Based on the nursing principle of "taking the patient as the nursing center", family nursing measures can improve the overall nursing quality and provide an effective psychological intervention for patients with clinical depression.

INTRODUCTION

Pregnancy is a special physiological period for women. During the normal development of the fetus, maternal physiology and psychology will experience a series of changes. After delivery, these physical and psychological changes gradually recover, but in this process, some women are prone to depression, seriously affecting their quality of life and subsequent feeding enthusiasm[1-4].

Clinical studies suggest that in addition to the changing family role as the main trigger, changes in sex hormone levels are also risk factors for postpartum depression[5,6]. The main manifestations of depression in postpartum women are depression, fear, excessive worry about the newborn, etc., which seriously affect their physical and mental health. At the same time, the current economic development of the country, the increase in social work pressure, and the increase in depression have led to the annual incidence in postpartum depression[7,8]. In view of the high incidence and harmfulness of postpartum depression, the approach to providing effective nursing care in clinical nursing activities is one of the key points of obstetrical care[9].

Previous studies have shown that routine basic postpartum care has a good effect on maternal physical rehabilitation; however, due to a lack of corresponding effective psychological intervention measures, there are some limitations in the nursing care of postpartum depression patients[10]. Based on the nursing principle of "taking the patient as the nursing center", family nursing measures can improve the overall nursing quality and provide an effective psychological intervention for patients with clinical depression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective analysis of the clinical data of 92 patients with postpartum depression admitted to our hospital was conducted from May 2017 to April 2019. The diagnostic criteria referred to the "Prevention and Conditioning of Postpartum Depression." Patients were grouped according to the nursing measures that they received after admission; 40 patients receiving basic care were enrolled in a basic nursing group, and 52 receiving family care were included in a family care group. There was no significant difference between the two groups (P < 0.05; Table 1). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital.

Table 1.

Comparison of basic data between the two groups [n = 46, n (%)]

|

Basic information

|

Basic nursing group

|

Home-based care group

|

χ

2

/t

|

P

value

|

|

| Cultural level | High school | 15 (32.61) | 14 (30.43) | 0.110 | 0.740 |

| College | 17 (36.96) | 17 (36.96) | 0.001 | 1.001 | |

| Bachelor's degree or above | 14 (30.43) | 15 (32.61) | 0.110 | 0.740 | |

| Age | 27.86 (3.59) | 27.61 (3.47) | 0.340 | 0.735 | |

| Estradiol (pmol/L) | 588.12 (38.20) | 593.00 (39.97) | 0.599 | 0.551 | |

| Progesterone (nmol/L) | 145.10 (10.02) | 145.99 (10.24) | 0.422 | 0.674 | |

| Serotonin (μmol/L) | 0.91 (0.12) | 0.93 (0.14) | 0.736 | 0.464 | |

The diagnostic criteria included the following: (1) SDS score ≥ 53; and (2) Clinical manifestations such as depression and depression.

The following inclusion criteria were used: (1) No history of prenatal depression; (2) Normal intelligence, with IQ test results showing an IQ > 70; (3) Good compliance and no severe resistance or resistance to study participation; (4) Voluntary use of their clinical data in this nursing study; and (5) Multiple physical examinations showing no serious heart, lung, kidney, or other organ diseases.

The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) Gestational diabetes mellitus or gestational hypertension; (2) Severe schizophrenia or cognitive dysfunction; (3) Other diseases that can affect the indicators included in this observation, such as ovarian hyperfunction and endometrial hyperplasia; and (4) Missing basic data.

Review of nursing methods

Basic care unit: The vital signs of the patients after childbirth were closely monitored, and wound healing was checked regularly. The matters needing attention in daily life were as follows: Yin cleaning and avoiding the consumption of spicy food. Patients were guided to gain relevant nursing knowledge and to improve their breastfeeding ability.

Family care unit: The above basic care was accompanied by home-based care as follows: Regarding ward management activities, patients were allowed to adjust and decorate the ward environment properly, such as putting up posters commonly used in patients' homes, placing small bonsai plants in the wards, etc. Their families were informed that they could deliver items that they often use and contact in their daily life, such as sofa pillows and water cups.

The use of family-style communication in daily nursing work reduced the use of professional terminology when nursing staff performed nursing work. In addition to the normal visits made for patient rehabilitation, the nurses chatted with the patients more. This family-oriented, ordinary, and life-oriented communication style improved nurse-patient relations, created a family-oriented language atmosphere, and improved patient communication enthusiasm and nursing compliance.

Regarding the psychological nursing work, the nursing staff educated the family members of the patient about postpartum depression, and informed them of the importance of their participation in the process of psychological nursing to help improve the patients' mood. Through the cooperation of family members to jointly implement subjective nursing measures, patients were guided to face the changes in their family role after delivery appropriately. In the process of psychological care, the nurses helped family members and patients to reconcile possible differences in parenting and to create a stress-free family atmosphere for patients.

Health education was conducted by nursing staff with substantial clinical experience and good communication skills in obstetrics to explain various physiological and psychological changes that occur throughout the special physiological cycle of a woman during pregnancy, childbirth, and rehabilitation. The purpose was to remove the tension and fear that the patient may have experienced due to the lack of relevant knowledge. The goals were to explain to them in detail the matters needing attention, including neonatal contact, daily feeding skills, bath skills, umbilical nursing-related knowledge, and how to change diapers; to improve the neonatal nursing ability of patients; and to alleviate some patients' worries about whether they can be competent as a mother.

Patients were guided on maintaining good dietary care, including appropriate intake of a high-protein, high-calorie diet, supplementing nutrients lost to labor, and avoiding spicy intake. Patients were directed to focus on rehabilitation exercises and appropriate daily activity; modern research has confirmed that exercise has a certain regulatory effect on female hormones, whereby reasonable exercise can promote a faster return to pre-pregnancy hormone levels.

Before discharge from the hospital, the patients provided their contact information, such as their QQ number, WeChat username, etc., and they were followed once a week to monitor their out-of-hospital rehabilitation progress and neonatal conditions and to provide continuous guidance.

Regarding the use of the anxiety self-rating anxiety scale (SAS) and depression self-rating scale (SDS), after the nursing measures outlined in 1.2.1 were given, the total score of the two scales was 80, and the score was proportional to the severity of anxiety and depression.

The quality of life of the patients was evaluated using a GQOLI-74 questionnaire after they received the care described in 1.2.2. The questionnaire is divided into four dimensions, including material, social, physical, and psychological, and the results are positively correlated with the quality of life of the patients.

Serum was collected after routine separation to include 5 mL of affected venous blood after the completion of nursing. The levels of estradiol (E2), serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine) and progesterone (PRGE) were measured by radioimmunoassay.

Nursing satisfaction was assessed through a simple questionnaire, which mainly includes nursing attitude, self-perceived comfort, nursing skills and so on. The questionnaire is a percentage system, and satisfaction levels were as follows: High satisfaction (100-85), satisfaction (84-50), and dissatisfaction (< 50).

Statistical analysis

The obtained data were processed with SPSS software package. The measurement data are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared using the independent sample t-test; the count data are expressed as percentages (%) and were compared using chi-squared tests. P < 0.05 indicated a significant difference.

RESULTS

Nursing satisfaction

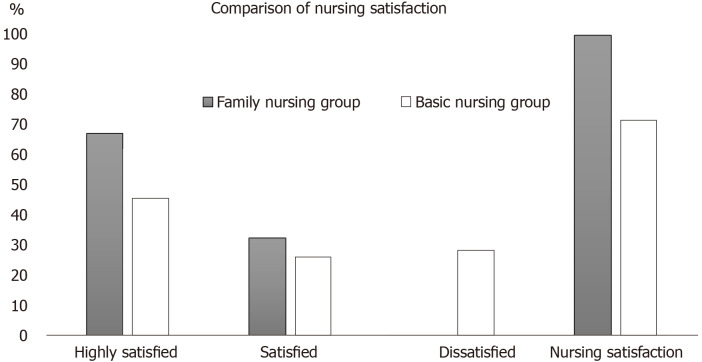

The satisfaction of the family nursing group was significantly higher than that of the basic nursing group (P = 0.001). The data and corresponding test results are shown in Table 2 and Figure 1.

Table 2.

Comparison of nursing satisfaction between the two groups [n = 46, n (%)]

|

Group

|

Highly satisfied

|

Satisfaction

|

Dissatisfied

|

Total

|

| Family care group | 31 (67.39) | 15 (32.61) | 0 (0.00) | 46 (100.00) |

| Basic nursing group | 21 (45.65) | 12 (26.09) | 13 (28.26) | 33 (71.74) |

| χ 2 | 9.616 | 1.025 | 32.910 | 32.910 |

| P value | 0.002 | 0.311 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Figure 1.

Comparison of nursing satisfaction between the two groups.

GQOLI-74 score

The data in Table 2 show that the scores of each dimension of the GQOLI-74 in the family nursing group were significantly higher than the corresponding scores of the basic nursing group (P < 0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

GQOLI-74 score comparison (n = 46, mean ± SD)

|

Group

|

Psychological

|

Society

|

Substance

|

Body

|

| Family care group | 93.53 ± 2.52 | 92.16 ± 3.02 | 90.85 ± 3.57 | 92.87 ± 3.06 |

| Basic nursing group | 84.16 ± 3.58 | 83.41 ± 3.87 | 81.57 ± 4.06 | 81.93 ± 4.51 |

| t | 19.516 | 12.089 | 11.642 | 13.614 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Comparison of SAS and SDS scores between the two groups

The SAS and SDS scores of the family nursing group were significantly lower than those of the basic nursing group (P < 0.05), and the data are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Comparison of SAS and SDS scores between the two groups (n = 46, mean ± SD)

|

Group

|

SAS

|

SDS

|

| Family care group | 30.21 (3.57) | 33.61 (3.69) |

| Basic nursing group | 40.16 (4.41) | 42.87 (5.06) |

| t | 11.894 | 10.029 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Comparison of E2, 5-HT, and PRGE levels in the two groups

The E2 and 5-HT levels of the family nursing group were significantly higher than those of the basic nursing group, and the PRGE level was significantly lower than that of the basic nursing group (P < 0.05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of estradiol, 5-hydroxytryptamine, and progesterone levels between the two groups [n = 46, n (%)]

|

Group

|

E2 (pmol/L)

|

5-HT (μmol/L)

|

PRGE (nmol/L)

|

| Family care group | 868.36 (59.49) | 1.78 (0.31) | 68.72 (11.48) |

| Basic nursing group | 710.29 (38.02) | 1.34 (0.24) | 96.23 (12.91) |

| t | 15.184 | 7.612 | 10.799 |

| P value | 0.001 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

PRGE: Progesterone; E2: Estradiol; 5-HT: 5-hydroxytryptamine.

DISCUSSION

Postpartum depression is the result of a combination of factors. Physiologically, after delivery, women’s physical state will be restored to their pre-pregnancy conditions; during this stage, various levels of hormones will have an impact on the nervous system. Psychologically, the family role after delivery changes from wife to mother, which can lead to psychological stress, and multiple factors may influence the occurrence of depression[11]. The epidemiological statistics show that the incidence of postpartum depression abroad is 3.5%-33.0%, and the incidence in China is higher than the international level, reaching 10.0%-38.0%[12]. Clinical postpartum depression patients experience depression, anxiety and so on, affecting their nursing care and treatment compliance, and the overall harm is great[13].

Family nursing requires treating the patient as the center of nursing, using the hospital environment as a home, and engaging in daily communication with the family, etc. to complete the nursing intervention, which emphasizes the positive effect of family nursing measures on the emotional state of patients[14]. In clinical practice, patients with postpartum depression are found to be a key population for targeted nursing measures. Previous studies have summarized the clinical manifestations of patients with postpartum depression into four main characteristics, including the emotional aspect, self-evaluation aspect, thought aspect, and life confidence aspect. Among them, the emotional aspect generally includes depression; its clinical manifestations are shyness, unwillingness to contact people, and irritability. The self-evaluation aspect typically addresses the patients’ feelings of self-abandonment, self-blame, and guilt; easily developing hostility toward other people; increased vigilance; and non-harmonious family relations. Patients who experience challenges in the thought aspect are generally slow and unable to focus quickly and have poor ability to handle routine affairs. Regarding life confidence, patients can generally feel that life is meaningless and have no positive life confidence and willingness to enjoy life; the typical manifestations are anorexia, libido, dizziness, nausea, constipation, etc.[15,16].

According to the results of this study, the E2, 5-HT, and PRGE levels of the family nursing group were better than those of the basic nursing group. Recent studies have shown that depression in women is associated with sex hormone imbalances[17,18]. Estrogen is an antidepressant. When estrogen levels are excessive, the development of depression is likely. Estrogen levels are associated with up/downregulation of 5-HT. When estrogen decreases, the 5-HT levels decrease, and 5-HT deficiency has been identified in previous studies as a major cause of depression[19]. Also noted in some studies is that PRGE decline is slow, i.e., high levels of maternal PRGE are also directly associated with postpartum depression[20]. At the same time, the SAS and SDS scores of the family nursing group were lower than those of the basic nursing group. In the course of family nursing, it was concluded that in addition to directly improving the emotional state of the patients, the nursing approach also had an effect on various hormone levels in the patients. In both groups, the quality of life scores and nursing satisfaction observations indicated that the family nursing group had significantly better outcomes than the basic nursing group, suggesting that family nursing can directly improve quality of life and nursing satisfaction after improving the emotional state of the patients.

The SAS and EPDS scores of the patients in both groups decreased significantly, but the scores of patients in the observation group decreased significantly more than those in the control group. The GSES scores in the observation group decreased significantly, and the incidence of depression was significantly lower. Maternal self-efficacy was improved, achieving the purpose of significantly preventing the occurrence of postpartum depression. The study revealed the positive role of home-based care in the prevention of postpartum depression; furthermore, in a nursing study on post-partum depression by Zhao Huijun, family nursing in postpartum depression patients yielded significantly better results than those in the control group (routine nursing). The study found that postpartum depression was the result of multiple factors, and the imbalance of various hormones was one of the important factors for developing depression. Incorporating family nursing in clinical nursing activities could affect multiple factors from physiology to psychology, from social relations to family relations, and from self-cognition to self-management. This study is highly consistent with previous studies on family nursing, which showed effective relief of depression. However, the specific nursing measures of home-based nursing still need to be improved and optimized, and clinical references need to be improved according to the different conditions of clinical patients to further improve the relevance of nursing care.

CONCLUSION

In summary, home-based nursing for patients with clinical postpartum depression can effectively improve their various hormone levels, play an effective role in alleviating their depression or depressed mood, and improve their quality of life and nursing satisfaction.

ARTICLE HIGHLIGHTS

Research background

Postpartum depression is a common mental illness in puerpera with a high incidence rate. Both changing family role as the main trigger and changes in sex hormone levels are risk factors for postpartum depression.

Research motivation

Postpartum depression has been investigated in many previous studies, which have shown that routine basic postpartum care has a good effect on maternal physical rehabilitation; however, due to a lack of corresponding effective psychological intervention measures, there are some limitations in the nursing care of postpartum depression patients. However, little research has been designed to investigate the positive role of home-based nursing in the prevention of postpartum depression. This study aimed to explore the importance of home-based nursing in postpartum depression.

Research objectives

To study the effect of home-based nursing for postpartum depression patients on their quality of life and depression, and research the importance of home-based nursing for patients with clinical postpartum depression and the influence of their hormone levels to lead more researchers to pay more attention to home-based nursing in postpartum depression patients.

Research methods

A retrospective analysis was performed on the clinical data of 92 patients with postpartum depression admitted to an obstetrical department. The patients were grouped according to the nursing measures that they received after admission. Data were collected by questionnaire investigation, and serum samples were collected. The obtained data were processed with the help of SPSS software package.

Research results

The satisfaction with nursing care, the scores of the GQOLI-74, SAS, and SDS, and the E2 and 5-HT levels of the family nursing group were significantly higher than those of the basic nursing group, which proved the importance of home-based nursing

Research conclusions

Home-based nursing for patients with clinical postpartum depression can effectively improve their various hormone levels, play an effective role in alleviating their depression or depressed mood, and improve their quality of life and satisfaction with nursing care. This study preliminarily proved the importance of home-based nursing.

Research perspectives

More studies are needed to investigate the positive role of home-based care in the prevention of postpartum depression and to provide new ideas for the treatment of postpartum depression through more research methods.

Footnotes

Institutional review board statement: The study was reviewed and approved by the Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Peer-review started: June 5, 2020

First decision: July 25, 2020

Article in press: September 4, 2020

Specialty type: Nursing

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Currie IS, Voigt M S-Editor: Ma YJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Li JH

Contributor Information

Chun-Yu Zhuang, Department of Nursing, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Sheng-Ying Lin, Department of Nursing, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Chen-Jia Cheng, Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery, Hainan Provincial People's Hospital, Haikou 570311, Hainan Province, China.

Xiao-Jing Chen, Department of Medicine, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Hui-Ling Shi, Department of Care Medicine, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Hong Sun, Department of Nursing, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Hong-Yu Zhang, Department of Midwifery, School of International Nursing, Hainan Medical College, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China.

Mian-Ai Fu, Department of Reproductive Medicine, Haikou Maternal and Child Health Hospital, Haikou 570203, Hainan Province, China. a18907667866@126.com.

Data sharing statement

No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Muchanga SMJ, Eitoku M, Mbelambela EP, Ninomiya H, Iiyama T, Komori K, Yasumitsu-Lovell K, Mitsuda N, Tozin RR, Maeda N, Fujieda M, Suganuma N Japan Environment and Children’s Study Group. Association between nausea and vomiting of pregnancy and postpartum depression: the Japan Environment and Children's Study. J Psychosom Obstet Gynaecol . :2020 1–9. doi: 10.1080/0167482X.2020.1734792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, Zhao Q, Cross WM, Chen J, Qin C, Sun M. Assessing the quality of mobile applications targeting postpartum depression in China. Int J Ment Health Nurs . 2020:Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1111/inm.12713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maliszewska K, Świątkowska-Freund M, Bidzan M, Krzysztof P. Screening for maternal postpartum depression and associationswith personality traits and social support. A Polish follow-upstudy 4 wk and 3 mo after delivery. Psychiatr Pol . 2017;51:889–898. doi: 10.12740/PP/68628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li XB, Liu A, Yang L, Zhang K, Wu YM, Zhao MG, Liu SB. Antidepressant-like effects of translocator protein (18 kDa) ligand ZBD-2 in mouse models of postpartum depression. Mol Brain . 2018;11:12. doi: 10.1186/s13041-018-0355-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fisher PM, Larsen CB, Beliveau V, Henningsson S, Pinborg A, Holst KK, Jensen PS, Svarer C, Siebner HR, Knudsen GM, Frokjaer VG. Pharmacologically Induced Sex Hormone Fluctuation Effects on Resting-State Functional Connectivity in a Risk Model for Depression: A Randomized Trial. Neuropsychopharmacology . 2017;42:446–453. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henningsson S, Madsen KH, Pinborg A, Heede M, Knudsen GM, Siebner HR, Frokjaer VG. Role of emotional processing in depressive responses to sex-hormone manipulation: a pharmacological fMRI study. Transl Psychiatry . 2015;5:e688. doi: 10.1038/tp.2015.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masoudi M, Khazaie H, Ghadami MR. Comments on: insomnia, postpartum depression and estradiol in women after delivery. Metab Brain Dis . 2018;33:673–674. doi: 10.1007/s11011-018-0184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farías-Antúnez S, Xavier MO, Santos IS. Effect of maternal postpartum depression on offspring's growth. J Affect Disord . 2018;228:143–152. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scarff JR. Use of Brexanolone for Postpartum Depression. Innov Clin Neurosci . 2019;16:32–35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chung TC, Chung CH, Peng HJ, Tsao CH, Chien WC, Sun HF. An analysis of whether sleep disorder will result in postpartum depression. Oncotarget . 2018;9:25304–25314. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.25219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Swanson LM, Burgess HJ, Zollars J, Todd Arnedt J. An open-label pilot study of a home wearable light therapy device for postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health . 2018;21:583–586. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0836-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller ES, Hoxha D, Pinheiro E, Grobman WA, Wisner KL. The association of serum C-reactive protein with the occurrence and course of postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health . 2019;22:129–132. doi: 10.1007/s00737-018-0841-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson M, Sharma V. Between a rock-a-bye and a hard place: mood disorders during the peripartum period. CNS Spectr . 2017;22:49–64. doi: 10.1017/S1092852917000852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rasmussen MH, Strøm M, Wohlfahrt J, Videbech P, Melbye M. Risk, treatment duration, and recurrence risk of postpartum affective disorder in women with no prior psychiatric history: A population-based cohort study. PLoS Med . 2017;14:e1002392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lin CC, Hung YY, Tsai MC, Huang TL. Increased serum anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antibody immunofluorescence in psychiatric patients with past catatonia. PLoS One . 2017;12:e0187156. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0187156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmadpanah M, Nazaribadie M, Aghaei E, Ghaleiha A, Bakhtiari A, Haghighi M, Bahmani DS, Akhondi A, Bajoghli H, Jahangard L, Holsboer-Trachsler E, Brand S. Influence of adjuvant detached mindfulness and stress management training compared to pharmacologic treatment in primiparae with postpartum depression. Arch Womens Ment Health . 2018;21:65–73. doi: 10.1007/s00737-017-0753-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McEvoy K, Osborne LM, Nanavati J, Payne JL. Reproductive Affective Disorders: a Review of the Genetic Evidence for Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder and Postpartum Depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep . 2017;19:94. doi: 10.1007/s11920-017-0852-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li F, He F, Sun Q, Li Q, Zhai Y, Wang X, Zhang T, Lin J. Reproductive history and risk of depressive symptoms in postmenopausal women: A cross-sectional study in eastern China. J Affect Disord . 2019;246:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Agampodi TC, Agampodi SB, Glozier N, Lelwala TA, Sirisena KDPS, Siribaddana S. Development and validation of the Social Capital Assessment Tool in pregnancy for Maternal Health in Low and middle income countries (LSCAT-MH) BMJ Open . 2019;9:e027781. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang Y, Briere CE, Xu W, Cong X. Factors Affecting Breastfeeding Outcomes at Six Months in Preterm Infants. J Hum Lact . 2019;35:80–89. doi: 10.1177/0890334418771307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No additional data are available.