Abstract

Over the past two decades, elderly colon cancer patients experienced less improvement in survival than their younger counterparts, yet the contributing factors remain unknown. We aimed to evaluate factors that may contribute to the age disparity of survival improvement among patients with colon cancer. Using data from the National Cancer Database, we identified patients diagnosed with colon cancer between 2004 and 2012 with follow-up data up to 2017. The hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for 5-year OS associated with study variables were estimated using multivariable Cox regression. Among 486,284 patients included in this study, elderly patients (aged ≥75) had a lower adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) treatment guidelines (% of non-adherence: 45.3%) than younger patients (aged <50, 19.3%; P<0.001). After adjusting for demographics, access to care and clinical characteristics, compared with patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2006, younger and older patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2012 experienced 16% (HR: 0.84, 95% CI: 0.81-0.88) and 6% (HR: 0.94, 95% CI: 0.93-0.95) reductions in mortality (P for interaction=1.42×10-5), respectively. After an additional adjustment for guideline adherence status, no significant difference in the improvement of survival was noted (P for interaction=0.17). The association patterns were similar regardless of tumor stage, race, and high comorbidity scores (all P for interaction>0.05). Several patient-related factors were identified in association with noncompliance to NCCN guidelines, including comorbidity status. However, over 60% of noncompliance elderly patients had a Charlson comorbidity score of 0. The observed age disparity in survival improvement among colon cancer patients was primarily explained by a slower improvement in adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines in elderly than younger patients. Many older adults were not receiving recommended therapies despite minimal comorbidities. Our findings call for measures to increase adherence to treatment guidelines among elderly patients to improve survival.

Keywords: Colon cancer, guideline adherence, survival improvement, elderly populations

Introduction

It is estimated that in 2020 there will be approximately 104,640 new cases of colon cancer and 44,556 deaths from colon cancer in the United States [1]. Colon cancer risk increases with age, with approximately 70% of patients diagnosed over 65 years of age and 42% over 75 years of age [2]. These proportions will likely continue to increase because of the aging population in the U. S. [3]. The fast-growing elderly population also increases the demand and challenges for cancer care in this population. It has been well documented that elderly patients with colon cancer have worse prognoses than younger patients [4,5]. Great progress in diagnostic and therapeutic techniques have led to a steady improvement in survival after colon cancer diagnosis [6,7]. However, this improvement has not been equally seen for patients across all age groups. We reported previously that elderly patients with colon cancer experienced less improvement in survival than their younger counterparts over the past two decades [8]. However, the underlying reasons for this disparity are unclear, affecting effective measures to improve cancer care for all.

Elderly populations, compared with younger individuals, are generally considered to have a higher probability of potential comorbidities, a worse overall physical condition, and frailties [9,10], which may affect the selection of therapeutic cancer regimens by patients and their health providers [11,12]. Consequently, this could compromise the final receipt of standard treatment. It was reported that elderly patients with stage II (high risk) or stage III cancer, as well as those with high comorbidity scores, were less likely to be offered adjuvant chemotherapy [13], which is a recommended treatment by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). However, prior studies have reported that elderly patients are less likely to receive recommended cardiovascular care, even after adjusting for comorbidities. This suggests that non-adherence with clinical guidelines could be biased by age alone [14,15]. A recent analysis using Texas Cancer Registry data indicated that noncompliance to guidelines was associated with a higher risk of mortality for elderly patients with stage II or III cancer [16]. In several other studies, it has been consistently seen that patients benefited from receiving guideline-concordant treatment [17-19]. Therefore, it is conceivable that non-adherence to guidelines may contribute to the slower survival improvement over the past 20 years among elderly patients with colon cancer than their younger counterparts in the U.S. We used data from the National Cancer Database (NCDB) to test this hypothesis and explore other factors that may contribute to the age disparity in the improvement of survival among colon cancer patients. We further evaluated potential factors associated with non-adherence of treatment guidelines among elderly patients.

Materials and methods

The data for this study were derived from the NCDB, which is a nationwide oncology database including data from more than 1,500 facilities accredited by the Commission on Cancer (CoC) across the United States [20]. The NCDB includes more than 70% of the newly diagnosed cancer cases in the U. S. To ensure a sufficient follow-up time, we limited the study to patients who were diagnosed between 2004 and 2012 with follow-up data up to 2017. Of the 620,485 colon cancer patients identified, 134,201 were excluded according to the following criteria: missing or invalid follow-up information, missing information on treatment or detailed stages, or stage 0 disease. The final cohort for analysis included 486,284 patients (Supplementary Figure 1). This study was conducted in concordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Study variables extracted from the NCDB included demographic characteristics (age at diagnosis, sex, race, residence, annual household income, education), access to care (insurance and facility type), clinical characteristics (Charlson comorbidity score, year of cancer diagnosis, stage, histologic type, histologic grade), and treatment information (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy). Patients’ age at diagnosis was divided into four groups (<50, 50-64, 65-74, and 75 years or older). Neighborhood household income was assessed by median household income levels and educational levels by the percentage of residents not receiving a high school education, based on the zip code of patients’ residence. A stage group was assigned preferentially using the reported pathologic stage; clinical stage was used when pathologic stage was not reported. Patients with stage II cancer were further categorized as low and high risk according to the NCCN criteria. Patients were considered to be low risk if they had T3N0M0 with no high-risk features, while those who had T3N0M0 with high-risk features or T4N0M0 were defined as high risk. The high-risk features included poor histologic grade (≥3), positive margin status, and inadequate lymph nodes retrieved (<12 nodes).

The stage-specific adherence status to NCCN treatment guidelines were identified following the algorithm described in previous studies [13,17]. Patients were defined as “adherent” if they received treatment in accordance with the following stage-specific recommendations: stage I, undergo surgical resection alone; stage II (low risk), in 2006 and before, undergo surgical resection alone; after 2006, undergo surgical resection with or without chemotherapy; stage II (high risk), undergo surgical resection and chemotherapy; stage III, undergo surgical resection and chemotherapy; stage IV, chemotherapy with or without surgical resection. In contrast, if they did not receive guideline-recommended treatment, they were classified as “non-adherent”. Patients were defined as “undergoing surgical treatment” if they underwent adequate surgical resection according to the most invasive surgical procedure at the tumor site. Those who did not have surgical procedures or only had tumor destruction with no pathological specimen produced were classified as inadequate surgical resection. Furthermore, the NCCN Panel believes that it is reasonable to accept the relative benefit of adjuvant therapy for patients with stage II (high risk), and recommends it as an optional treatment. Therefore, patients with stage II (high risk) were considered as adherent if they underwent surgical resection and chemotherapy in this study, which is supported by several previous studies [13,17].

Statistical analysis

The primary outcome was a 5-year overall survival (OS), defined as the time from diagnosis until death, or the date of last contact within five years, or censored at five years if the patient survived five years or longer. Baseline characteristics across age groups were compared using the χ2 test. Five-year OS rates across age groups were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared using the Log-rank test.

Multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate the hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of death among colon cancer patients associated with study variables, such as the year of diagnosis, demographic features, access to care, clinical characteristics, and adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines. The proportional hazard assumption was assessed by plotting scaled Schoenfeld residuals and log-log survival plots. In the analysis of the association of adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines with survival stratified by age groups, factors associated with both survival and adherence status were considered confounders and adjusted for in the analysis. Then, the HRs and 95% CIs for 5-year mortality associated with year of diagnosis were estimated across different age groups separately. The HRs and 95% CIs were derived with (i) adjustment for demographic features, access to care, and clinical characteristics; (ii) additional adjustment for comorbidity; (iii) further adjustment for adherence status. Interactions between age and year of diagnosis were individually tested in each model using likelihood ratio tests. Stratified analyses by stage, race/ethnicity and comorbidity were further conducted to test the potential modification effects of these factors. Multivariable logistic regression was also used to identify factors associated with non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines among those older than 75.

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and statistical significance was defined as P<0.05. All analyses were performed using R, version 3.2.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing). Statistical analyses were conducted from November 25, 2019, to January 15, 2020.

Results

Among the 486,284 patients included in the study, 234,258 (48.2%) were male. The mean (SD) age was 68.6 (13.6) years. The baseline characteristics of the patients are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. Briefly, older patients (≥75 years), compared with their younger counterparts (<50 years), tended to have a substantially higher Charlson comorbidity score (≥1 score: 37.7% vs 12.0%) and were much less likely to receive chemotherapy (66.0% vs 19.2%), or to adhere to treatment guidelines (45.3% vs. 19.3%).

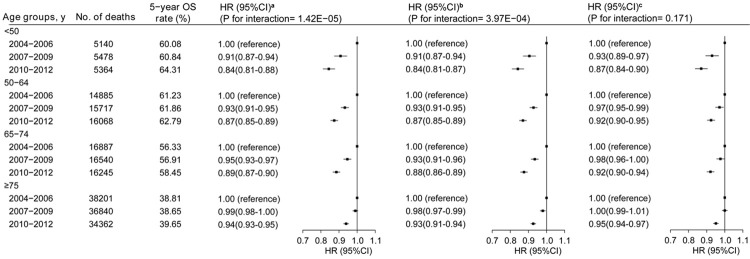

With a median follow-up time of 46.2 months (IQR: 15.1-76.1), 261,801 (53.8%) patients died during the study period. Although an increase in survival from 2004 to 2012 was observed across all age groups, the magnitude of the improvement was smaller in older patients (≥75 years older) compared with their younger counterparts (p for interaction=1.42×10-5, Figure 1, left panel). For example, overall mortality among colon cancer patients was reduced 4.23% among patients <50 years, but only 0.84% among those ≥75 years for the time period of 2010-12 compared to 2004-06.

Figure 1.

Five-year overall survival rates and multivariate adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for the risk of death associated with year of diagnosis by age. aThe HRs and 95% CIs were adjusted for age, sex, race, residence, education, income, facility type, insurance, histology, grade and TNM stage (left panel). bAdditional adjusting for Charlson comorbidity score (middle panel). cFurther additional adjusting for adherence status to NCCN treatment guidelines (right panel). P values for interactions between age and year of diagnosis are displayed.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis showed that, after TNM stage and age, adherence status to NCCN treatment guidelines is the most significant predictor for survival among colon cancer patients (HR: 1.93, 95% CI: 1.92-1.95 for non-adherence vs adherence), followed by Charlson comorbidity score (HR: 1.70, 95% CI: 1.68-1.73; score ≥2 vs. score=0) (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure 2). The association between adherence status and mortality was observed across all age groups, and this association remained essentially unchanged after adjusting for the Charlson comorbidity score (Table 2). Similar, but weaker, association patterns were observed for comorbidity status in the age-specific analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Adjusting for the Charlson comorbidity score slightly attenuated the age disparity in the improvement of survival from the period of 2004-06 to 2010-12 (Figure 1, middle panel, P for interaction=3.97×10-4), while additional adjustment for adherence status of NCCN guidelines substantially narrowed the disparity (P for interaction=0.17) (Figure 1, right panel). The association patterns were similar regardless of tumor stage, race and high comorbidity scores (all P for interaction >0.05) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Table 1.

Five-year overall survival and hazard ratios of total mortality associated with selected demographic and clinical characteristics among patients with colon cancer: results from the National Cancer Database

| Variables | No. of deaths | 5-y overall survival (%) | HR (95% CI)d |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | |||

| <50 | 15,982 | 61.9 | 1.00 |

| 50-64 | 46,670 | 62.0 | 1.09 (1.07-1.11) |

| 65-74 | 49,672 | 57.3 | 1.25 (1.23-1.28) |

| ≥75 | 109,403 | 39.1 | 2.15 (2.10-2.20) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 108,836 | 50.9 | 1.00 |

| Female | 112,891 | 52.8 | 0.88 (0.88-0.89) |

| Racea | |||

| White | 186,216 | 52.0 | 1.00 |

| Black | 28,180 | 48.8 | 1.10 (1.09-1.12) |

| Other | 5,651 | 60.5 | 0.84 (0.82-0.86) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004-2006 | 75,113 | 50.7 | 1.00 |

| 2007-2009 | 74,575 | 51.5 | 0.99 (0.98-1.00) |

| 2010-2012 | 72,039 | 53.4 | 0.93 (0.92-0.94) |

| Residencea | |||

| Metro | 175,770 | 52.6 | 1.00 |

| Urban | 32,070 | 50.4 | 0.98 (0.96-0.99) |

| Rural | 4,698 | 50.6 | 0.97 (0.94-1.00) |

| Annual household incomea | |||

| <$30,000 | 32,745 | 48.2 | 1.00 |

| $30,000-$34,999 | 41,695 | 50.0 | 0.96 (0.95-0.98) |

| $35,000-$45,999 | 60,492 | 51.8 | 0.93 (0.92-0.95) |

| ≥$46,000 | 78,450 | 54.9 | 0.90 (0.88-0.92) |

| Insurancea | |||

| No insurance | 6,862 | 50.9 | 1.00 |

| Private insurance | 54,041 | 63.6 | 0.75 (0.73-0.77) |

| Government insurance | 157,245 | 45.9 | 0.95 (0.93-0.98) |

| Educational attainmenta,b | |||

| ≥29% | 37,687 | 49.8 | 1.00 |

| 20%-28.9% | 52,274 | 50.6 | 1.02 (1.00-1.03) |

| 14%-19.9% | 54,004 | 51.6 | 1.01 (0.99-1.02) |

| <14% | 69,424 | 54.8 | 0.97 (0.95-0.98) |

| Facility typea | |||

| Community | 29,849 | 49.9 | 1.00 |

| Comprehensive community | 107,454 | 51.6 | 0.96 (0.94-0.97) |

| Academic/research program | 56,140 | 52.7 | 0.87 (0.85-0.88) |

| Integrated network | 24,351 | 51.3 | 0.95 (0.93-0.96) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 141,997 | 55.3 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 53,699 | 47.9 | 1.21 (1.20-1.22) |

| 2 | 26,031 | 34.4 | 1.70 (1.68-1.73) |

| Tumor stage | |||

| I | 27,981 | 74.1 | 1.00 |

| II | 44,025 | 62.0 | 1.21 (1.19-1.23) |

| III | 58,436 | 55.1 | 1.75 (1.73-1.78) |

| IV | 91,285 | 11.8 | 7.71 (7.60-7.82) |

| Tumor histology | |||

| Adenocarcinomas | 210,914 | 52.5 | 1.00 |

| Others | 10,813 | 33.2 | 1.21 (1.19-1.24) |

| Tumor gradea | |||

| Well differentiated | 16,078 | 64.6 | 1.00 |

| Moderately differentiated | 119,726 | 56.7 | 1.15 (1.13-1.17) |

| Poorly differentiated | 50,797 | 40.5 | 1.49 (1.46-1.52) |

| Undifferentiated | 6,023 | 39.4 | 1.54 (1.49-1.59) |

| Treatment adherence statusc | |||

| Adherence | 124,095 | 60.0 | 1.00 |

| Non-adherence | 97,632 | 34.5 | 1.93 (1.92-1.95) |

Abbreviations: OS, overall survival; HR, Hazard Ratio.

Unknown data was not shown.

Educational attainment refers to the percentage of adults who did not graduate from high school in the patient’s area of residence.

Adherence status to NCCN treatment guidelines.

HRs were derived from models including all variables listed in the table.

Table 2.

Associations between adherence status and the risk of death among patients with colon cancer stratified by age: results from the National Cancer Databasea

| Strata | Adherent | Non-adherent | HR (95% CI)b | HR (95% CI)c | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| No. of patients | No. of deaths | No. of patients | No. of deaths | |||

| Aged <50 | 36,410 | 12,593 | 8,689 | 3,389 | 1.71 (1.65-1.78) | 1.71 (1.64-1.78) |

| Aged 50-64 | 101,775 | 32,853 | 28,781 | 13,817 | 2.02 (1.98-2.07) | 2.01 (1.97-2.05) |

| Aged 65-74 | 89,593 | 30,860 | 32,924 | 18,812 | 2.28 (2.24-2.33) | 2.24 (2.20-2.29) |

| Aged ≥75 | 102,891 | 47,789 | 85,221 | 61,614 | 2.27 (2.23-2.30) | 2.23 (2.20-2.26) |

Abbreviations: HR, Hazard Ratio.

Adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines as the reference.

Adjustment for age, sex, race, residence, education, income, facility type, insurance, histology, grade, TNM stage.

Additional adjustment for Charlson comorbidity score.

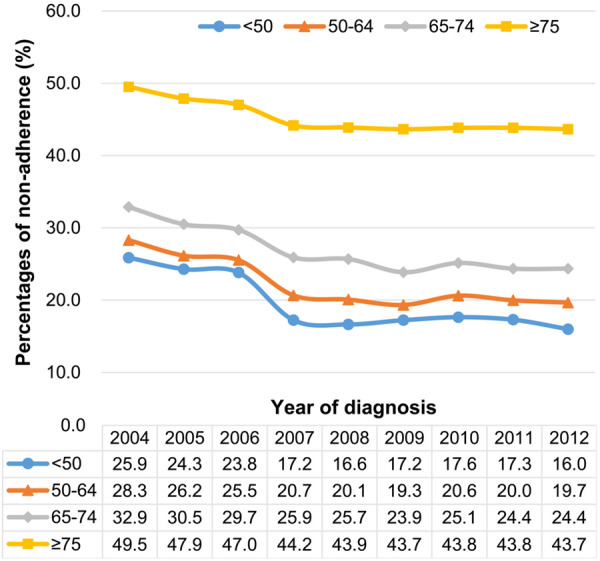

Although proportions of adherence to guidelines increased from 2004 to 2012 across all age groups, the trend was less evident among elderly patients, and the non-adherence proportion remained much higher among elderly than for younger patients in 2012 (43.7% vs. 16.0%, Figure 2). Logistic regression analysis showed that factors associated with non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines among patients ≥75 years included Charlson comorbidity score, female, black, no insurance, and low educational attainment of patients’ residence (Table 3). There were still over 60% of noncompliance elderly patients with a Charlson comorbidity score of 0.

Figure 2.

Proportions of non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines for patients with colon cancer from 2004-2012 by age: results from the National Cancer Database.

Table 3.

Factors associated with non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines for colon cancer patients older than 75 years: results from the National Cancer Database

| Variables | Adherent (n, %) | Non-adherent (n, %) | OR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 44,872 (43.6) | 33,799 (39.7) | 1.00 |

| Female | 58,019 (56.4) | 51,422 (60.3) | 1.12 (1.09-1.14) |

| Raceb | |||

| White | 92,594 (90.0) | 75,526 (88.6) | 1.00 |

| Black | 7,344 (7.1) | 7,117 (8.4) | 1.16 (1.11-1.21) |

| Other | 2,281 (2.2) | 1,933 (2.3) | 1.01 (0.94-1.08) |

| Residenceb | |||

| Metro | 83,634 (81.3) | 69,224 (81.2) | 1.00 |

| Urban | 13,573 (13.2) | 10,994 (12.9) | 0.93 (0.90-0.96) |

| Rural | 2,084 (2.0) | 1,731 (2.0) | 0.90 (0.84-0.97) |

| Annual household incomeb | |||

| <$30,000 | 12,109 (11.8) | 10,853 (12.7) | 1.00 |

| $30,000-$34,999 | 18,167 (17.7) | 15,297 (18.0) | 0.98 (0.94-1.02) |

| $35,000-$45,999 | 28,772 (28.0) | 23,790 (27.9) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| ≥$46,000 | 40,803 (39.7) | 32,556 (38.2) | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| Insuranceb | |||

| No insurance | 310 (0.3) | 369 (0.4) | 1.00 |

| Private insurance | 9,428 (9.2) | 7,462 (8.8) | 0.72 (0.61-0.86) |

| Government insurance | 92,028 (89.4) | 76,199 (89.4) | 0.75 (0.64-0.89) |

| Educational attainmentb,c | |||

| ≥29% | 13,591 (13.2) | 12,306 (14.4) | 1.00 |

| 20%-28.9% | 22,190 (21.6) | 18,760 (22.0) | 0.95 (0.92-0.99) |

| 14%-19.9% | 26,439 (25.7) | 21,805 (25.6) | 0.92 (0.89-0.96) |

| <14% | 37,633 (36.6) | 29,627 (34.8) | 0.89 (0.85-0.93) |

| Facility type | |||

| Community | 14,064 (13.7) | 12,522 (14.7) | 1.00 |

| Comprehensive community | 53,067 (51.6) | 44,496 (52.2) | 0.91 (0.88-0.94) |

| Academic/research program | 24,301 (23.6) | 18,801 (22.1) | 0.79 (0.76-0.81) |

| Integrated network | 11,459 (11.1) | 9,402 (11.0) | 0.87 (0.84-0.91) |

| Year of diagnosis | |||

| 2004-2006 | 33,130 (32.2) | 30,767 (36.1) | 1.00 |

| 2007-2009 | 34,619 (33.6) | 27,092 (31.8) | 0.77 (0.75-0.79) |

| 2010-2012 | 35,142 (34.2) | 27,362 (32.1) | 0.72 (0.70-0.74) |

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||

| 0 | 65,321 (63.5) | 51,801 (60.8) | 1.00 |

| 1 | 26,586 (25.8) | 22,485 (26.4) | 1.11 (1.08-1.14) |

| 2 | 10,984 (10.7) | 10,935 (12.8) | 1.42 (1.38-1.47) |

Abbreviations: OR, Odds Ratio.

ORs were derived from the model including all variables listed in the table with adjustment of histology, TNM stage, grade.

The percentages were calculated based on all the population. OR of unknown data was not shown.

Educational attainment refers to the percentage of adults who did not graduate from high school in the patient’s area of residence.

Discussion

In this large national registry-based study, we found a much higher proportion of non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines among elderly patients with colon cancer than among their younger counterparts. Although the proportions of non-adherence have reduced steadily over the years in all age groups, the reduction was much less evident in elderly patients, which has contributed to a slower improvement in survival among elderly than younger patients with colon cancer over the past two decades. We have shown further that several patient-related factors and comorbidity are risk factors of non-adherence of NCCN treatment guidelines. These findings are supported by results from several previous studies and calls for action to improve cancer treatment in elderly patients to reduce age-related disparities in cancer survival.

NCCN treatment guidelines for colon cancer are updated regularly, taking into consideration the recent advances in oncology [21]. Similar to our study, several previous studies also have shown that adherence to NCCN guidelines is associated with better survival among patients with colon cancer [16-19]. Our findings for a higher non-adherence proportion to NCCN treatment guidelines among elderly patients are also supported by previous studies, which showed that the proportions of colon cancer patients receiving surgical treatment and adjuvant chemotherapy decline with age [22,23]. Using NCDB data, we confirmed our previous findings based on SEER data that, over the past two decades, elderly patients experienced less improvement in survival than did younger patients [8]. In addition to confirming these previous findings using a large national dataset, we provide strong evidence, for the first time, that the age disparity in the improvement of survival in colon cancer patients is largely due to poorer adherence of NCCN treatment guidelines among elderly patients compared with their younger counterparts.

Previous clinical trials have shown that elderly patients with colon cancer receive similar benefits of adjuvant therapy as younger patients, and it is equally safe and effective [24-26]. However, treatment delivered in real-world clinical practice might be very much different from that in clinical trials. This difference may be more pronounced among elderly patients, for whom more aggressive therapies might not be used [27-29]. Comorbidity is an important factor in predicting guideline adherence in colon cancer [13,16,30] and several other malignancies [31,32]. In our study, comorbidity was also found to have the greatest impact on adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines among elderly populations. A recent study noted that the receipt of guideline-recommended adjuvant treatment was associated with better survival, even among patients with a high Charlson comorbidity index [33], supporting the notion that guideline-recommended treatments should be considered seriously regardless of comorbidity status. However, still over 60% of elderly patients were non-adherent to NCCN treatment guidelines with a Charlson comorbidity index of zero. It is not certain why such a large proportion of healthy older adults might not undergo appropriate therapies. Similar findings regarding the impact of age on the delivery of appropriate medical services have been described with stroke care [14], acute myocardial infarction treatment [15,34], and management of lung cancer [35]. As in our study, these age-related differences in treatment were not accounted for by comorbidities and may represent a bias towards older adults. In our study, we found that several patient-related factors, i.e., patients who were female, black, with no insurance, or in low education residence, were related to non-adherence to the NCCN treatment guidelines among elderly patients. Thus, appropriate measures are needed to increase the adherence to treatment guidelines in the sub-populations defined by these characteristics. Moreover, considering elderly patients were underrepresented in cancer clinical trials [36], future clinical trials specifically designed for elderly patients are warranted in order to develop easier-to-follow, and similarly effective, treatment regimens or strategies.

The strength of our study includes the large sample size and systematic analysis with an adjustment for multiple key covariates. Nonetheless, several limitations should also be acknowledged. First, data are not available in the NCDB regarding the number and types of comorbidities, specific chemotherapy regimens and lifestyle factors, and thus, we were unable to evaluate potential confounding or modification effects of these variables. Second, information on causes of death is unavailable in the NCDB, preventing us from analyzing cancer specific mortality. We performed 5-year survival analyses by limiting the time to five years after diagnosis and assumed that deaths during this short-time period close to diagnosis were more likely to be related to colon cancer.

In summary, our study confirms our previous findings of a slower improvement in survival among elderly than younger colon cancer patients in the U.S. over the past two decades, and provides strong evidence that non-adherence to NCCN treatment guidelines in elderly patients is the primary contributor to this age-related disparity in survival improvements. We have identified multiple risk factors for non-adherence to treatment guidelines. Many older adults were not receiving recommended therapies despite minimal comorbidities. Our study calls for measures to improve treatment guideline adherence to reduce mortality among elderly patients who account for the majority of colon cancer patients diagnosed in the U.S. and other countries.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported in part by Anne Potter Wilson Chair Endowment to Vanderbilt University. All information was derived from the American College of Surgeons’ National Cancer Database. We thank Marshal Younger, Division of Epidemiology, Vanderbilt University Medical Center, for his assistance in editing the manuscript. He received no additional compensation, outside of his usual salary, for his contribution.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cancer Tomorrow. [cited 2020 March 22]; Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/tomorrow/home.

- 2.Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, Miller KD, Ma JM, Rosenberg PS, Jemal A. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974-2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw322. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. The older population in the United States. 2018. [cited 2020 January 20]; Available from: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/2018/demo/age-and-sex/2018-older-population.html.

- 4.McKay A, Donaleshen J, Helewa RM, Park J, Wirtzfeld D, Hochman D, Singh H, Turner D. Does young age influence the prognosis of colorectal cancer: a population-based analysis. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:370. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubbard J, Thomas DM, Yothers G, Green E, Blanke C, O’Connell MJ, Labianca R, Shi Q, Bleyer A, de Gramont A, Sargent D. Benefits and adverse events in younger versus older patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer: findings from the adjuvant colon cancer endpoints data set. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:2334–2339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:7–34. doi: 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pal SK, Miller MJ, Agarwal N, Chang SM, Chavez-MacGregor M, Cohen E, Cole S, Dale W, Magid Diefenbach CS, Disis ML, Dreicer R, Graham DL, Henry NL, Jones J, Keedy V, Klepin HD, Markham MJ, Mittendorf EA, Rodriguez-Galindo C, Sabel MS, Schilsky RL, Sznol M, Tap WD, Westin SN, Johnson BE. Clinical cancer advances 2019: annual report on progress against cancer from the american society of clinical oncology. J. Clin. Oncol. 2019;37:834–849. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.02037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng C, Wen W, Morgans AK, Pao W, Shu XO, Zheng W. Disparities by race, age, and sex in the improvement of survival for major cancers: results from the National Cancer Institute Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program in the United States, 1990 to 2010. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:88–96. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2014.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caughey GE, Ramsay EN, Vitry AI, Gilbert AL, Luszcz MA, Ryan P, Roughead EE. Comorbid chronic diseases, discordant impact on mortality in older people: a 14-year longitudinal population study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2010;64:1036–1042. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.088260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Given B, Given CW. Older adults and cancer treatment. Cancer. 2008;113:3505–3511. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarfati D, Koczwara B, Jackson C. The impact of comorbidity on cancer and its treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66:338–350. doi: 10.3322/caac.21342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Given B, Given CW. Cancer treatment in older adults: implications for psychosocial research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:S283–S285. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chagpar R, Xing Y, Chiang YJ, Feig BW, Chang GJ, You YN, Cormier JN. Adherence to stage-specific treatment guidelines for patients with colon cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:972–979. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luker JA, Wall K, Bernhardt J, Edwards I, Grimmer-Somers KA. Patients’ age as a determinant of care received following acute stroke: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:161. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McLaughlin TJ, Soumerai SB, Willison DJ, Gurwitz JH, Borbas C, Guadagnoli E, McLaughlin B, Morris N, Cheng SC, Hauptman PJ, Antman E, Casey L, Asinger R, Gobel F. Adherence to national guidelines for drug treatment of suspected acute myocardial infarction: evidence for undertreatment in women and the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156:799–805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao H, Zhang N, Ho V, Ding MM, He WG, Niu J, Yang M, Du XL, Zorzi D, Chavez-MacGregor M, Giordano SH. Adherence to treatment guidelines and survival for older patients with stage II or III colon cancer in texas from 2001 through 2011. Cancer. 2018;124:679–687. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boland GM, Chang GJ, Haynes AB, Chiang YJ, Chagpar R, Xing Y, Hu CY, Feig BW, You YN, Cormier JN. Association between adherence to National Comprehensive Cancer Network treatment guidelines and improved survival in patients with colon cancer. Cancer. 2013;119:1593–1601. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hines RB, Barrett A, Twumasi-Ankrah P, Broccoli D, Engelman KK, Baranda J, Ablah EA, Jacobson L, Redmond M, Tu W, Collins TC. Predictors of guideline treatment nonadherence and the impact on survival in patients with colorectal cancer. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2015;13:51–60. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2015.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Javid SH, Varghese TK, Morris AM, Porter MP, He H, Buchwald D, Flum DR Collaborative to Improve Native Cancer Outcomes (CINCO) Guideline-concordant cancer care and survival among American Indian/Alaskan native patients. Cancer. 2014;120:2183–2190. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American College of Surgeons. National cancer database. [cited 2020 March 2]; Available from: https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/cancer/ncdb.

- 21.National Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCCN) NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: colon cancer. [cited 2019 November 21]; Available from: https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.

- 22.Majano SB, Di Girolamo C, Rachet B, Maringe C, Guren MG, Glimelius B, Iversen LH, Schnell EA, Lundqvist K, Christensen J, Morris M, Coleman MP, Walters S. Surgical treatment and survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark, England, Norway, and Sweden: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019;20:74–87. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30646-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manjelievskaia J, Brown D, McGlynn KA, Anderson W, Shriver CD, Zhu KM. Chemotherapy use and survival among young and middle-aged patients with colon cancer. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:452–459. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.5050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sargent DJ, Goldberg RM, Jacobson SD, Macdonald JS, Labianca R, Haller DG, Shepherd LE, Seitz JF, Francini G. A pooled analysis of adjuvant chemotherapy for resected colon cancer in elderly patients. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1091–1097. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Folprecht G, Seymour MT, Saltz L, Douillard JY, Hecker H, Stephens RJ, Maughan TS, Van Cutsem E, Rougier P, Mitry E, Schubert U, Kohne CH. Irinotecan/fluorouracil combination in first-line therapy of older and younger patients with metastatic colorectal cancer: combined analysis of 2,691 patients in randomized controlled trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008;26:1443–1451. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blanke CD, Bot BM, Thomas DM, Bleyer A, Kohne CH, Seymour MT, de Gramont A, Goldberg RM, Sargent DJ. Impact of young age on treatment efficacy and safety in advanced colorectal cancer: a pooled analysis of patients from nine first-line phase III chemotherapy trials. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2781–2786. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.5281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jonker JM, Hamaker ME, Soesan M, Tulner CR, Kuper IMJA. Colon cancer treatment and adherence to national guidelines: does age still matter? J Geriatr Oncol. 2012;3:131–137. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aparicio T, Navazesh A, Boutron I, Bouarioua N, Chosidow D, Mion M, Choudat L, Sobhani I, Mentre F, Soule JC. Half of elderly patients routinely treated for colorectal cancer receive a sub-standard treatment. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2009;71:249–257. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Potosky AL, Harlan LC, Kaplan RS, Johnson KA, Lynch CF. Age, sex, and racial differences in the use of standard adjuvant therapy for colorectal cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2002;20:1192–1202. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.5.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lemmens VE, van Halteren AH, Janssen-Heijnen ML, Vreugdenhil G, Repelaer van Driel OJ, Coebergh JW. Adjuvant treatment for elderly patients with stage III colon cancer in the southern Netherlands is affected by socioeconomic status, gender, and comorbidity. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:767–772. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormick B, Ottesen RA, Hughes ME, Javid SH, Khan SA, Mortimer J, Niland JC, Weeks JC, Edge SB. Impact of guideline changes on use or omission of radiation in the elderly with early breast cancer: practice patterns at national comprehensive cancer network institutions. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:796–802. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cliby WA, Powell MA, Al-Hammadi N, Chen L, Miller JP, Roland PY, Mutch DG, Bristow RE. Ovarian cancer in the United States: contemporary patterns of care associated with improved survival. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;136:11–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wollschlager D, Meng X, Wockel A, Janni W, Kreienberg R, Blettner M, Schwentner L. Comorbidity-dependent adherence to guidelines and survival in breast cancer-is there a role for guideline adherence in comorbid breast cancer patients? A retrospective cohort study with 2137 patients. Breast J. 2018;24:120–127. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harries C, Forrest D, Harvey N, McClelland A, Bowling A. Which doctors are influenced by a patient’s age? A multi-method study of angina treatment in general practice, cardiology and gerontology. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16:23–27. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peake MD, Thompson S, Lowe D, Pearson MG Participating Centres. Ageism in the management of lung cancer. Age Ageing. 2003;32:171–7. doi: 10.1093/ageing/32.2.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Abbasi J. Older patients (Still) left out of cancer clinical trials. JAMA. 2019;322:1751–1753. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.