Abstract

Cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) maintains primary roles in toxic metabolism, catalyzes redox reaction, and contributes to chemotherapeutic resistance. However, the mechanism of CYP3A5 in carcinogenesis remains largely undefined. Here, we investigated a novel role of CYP3A5 inhibiting the metastasis in lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) via ATOH8/Smad1 axis. We found that CYP3A5 was generally down-regulated in LUAD by RT-PCR, western blot and immunohistochmeistry (IHC) in tissues and cell lines. Low expression of CYP3A5 was significantly associated with poor prognosis of LUAD patients. Functionally, ectopic expression of CYP3A5 could substantially inhibit the migration and invasion in vitro. Consistently, up-regulation of CYP3A5 dramatically suppressed metastatic ability in vivo. Mechanistically, high-throughput phosphorylation chip indicated that CYP3A5 significantly decreased the phosphorylation of Smad1, resulting in suppression of metastasis. Furthermore, bioinformatics analysis and co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) experiments uncovered that CYP3A5 interacted with ATOH8, and the interaction, in turn, mediated in-activation in the Smad1 pathway. The combined IHC panel, including CYP3A5 and phosphorylation of Smad1, exhibited a better prognostic value for LUAD patients than any of these components individually. Taken together, CYP3A5 repressed activation of Smad1 to inhibit LUAD metastasis via interacting with ATOH8, indicating a novel potential mechanism of CYP3A5 in LUAD progression.

Keywords: Lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD), CYP3A5, metastasis, biomarker

Introduction

Lung cancer is now the leading cause of mortality and morbidity due to cancer. Over the past decades, the pathological constitution of lung cancer has gradually changed, and lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) has become the most prevalent subtype, accounting for approximately 70% of total lung cancers [1,2]. However, the role of cytochrome P450 3A5 (CYP3A5) in the development and progression of LUAD is largely unknown. An epidemiological study demonstrated that the rs776746 polymorphism of CYP3A5 and smoking may play roles in the survival of lung cancer patients undergoing therapy [3]. In addition, polymorphisms of CYP3A5 influence the efficiency of targeted drug metabolism in LUAD [4]. Therefore, we hypothesized that CYP3A5 is involved in the progression of LUAD.

CYP3A5 is an enzyme belonging to the cytochrome P450 family involved in the metabolism of many substances, including endogenous hormone synthesis and degradation and the metabolism of potentially toxic compounds [5]. Increasing evidence has shown that CYP3A5 is deregulated in multiple cancers, such as prostate, lung, gastric, and kidney cancers [6]. Previous works have shown that CYP3A5 plays a crucial role in regulating various aspects of cancer via metabolism, such as chemotherapy and drug metabolism. Biological findings have indicated that the function of CYP3A5 in cancer is mainly dependent on metabolism.

In this study, we identified novel biological functions of CYP3A5 in the progression of LUAD and show that CYP3A5 could suppress the Smad1 signaling pathway by interacting with ATOH8.

Materials and methods

Data analysis & patient samples

Expression data (GSE19804 and GSE10072) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [9,10]. RNA-seq data from LUAD were downloaded from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA; http://cancergenome.nih.gov). The differential expression of CYP3A5 between paired tumor tissues and normal tissues was assessed with data from TCGA, GSE19804, and GSE10072 and analyzed by Student’s t-test. Kaplan-Meier (KM) plotter (http://kmplot.com/analysis/) was used for survival analysis. Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) was carried out as described previously to identify the clinical significance of differential CYP3A5 expression [11].

Forty-two paired tumor and adjacent normal tissues with clinical records were collected from Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Cancer Hospital. This study was approved by the Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Cancer Hospital Research Ethics Committee. Immunohistochemistry of lung tissue slides was performed using the appropriate antibodies as described in the section below.

Cell culture and lentivirus system

LUAD cell lines (A549, NCI-H1975, NCI-H1299, NCI-H358, SPCA1, PC9) were purchased from the Shanghai Institutes for Biological Science (China). All cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (KeyGene, Nanjing, China) or RPMI 1640 medium (KeyGene, China) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, Thermo Fisher). Cells were cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 and confirmed to be negative for mycoplasma infection. DNA fingerprinting was conducted to verify cell authenticity within six months of use for the current study.

The lentivirus vector system used in this experiment was constructed with the vector pGCSIL-GFP for the stable expression of CYP3A5 mRNA and a marker (a GFP fusion protein). This recombinant lentivirus to express CYP3A5-GFP was designed and cloned by GeneChem Corporation (Shanghai, China). The recombinant lentivirus, enhanced infection solution (ENi.S.) and polybrene were mixed and transfected into cells at the optimal multiplicity of infection (MOI) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Virus-infected cells were detected by their GFP fluorescence signal within 72 h.

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

RNA was extracted from tissues and cells with TRIzol (Invitrogen, MA, USA) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Prime ScriptTM RT Master Mix (Takara, Shiga Prefecture, Japan) was used to perform reverse transcription to obtain cDNA. Quantitative real-time PCR was carried out to analyze CYP3A5 mRNA expression using SYBR Master Mix (Takara, Shiga Prefecture, Japan) on a Q6 RT-PCR machine. The primers used were synthesized by GeneChem Corporation (Shanghai, China). Relative expression was normalized to an internal control (GAPDH) and assessed by the 2-ΔΔCt method. The PCR primer sequences are listed in Table S2.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

Paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned, mounted on positively charged glass slides, baked, deparaffinized, and rehydrated. Antigen retrieval was performed by heating slides in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, pH 8.0) for 10 min. Sections were incubated in antibody overnight at 4°C and then incubated with secondary antibodies at 37°C for 45 min. The sections were then stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and visualized. Immunostaining assays were independently and blindly performed by two pathologists, and the results were determined according to both the intensity of the staining and the proportion of the stained area.

Western blot assay

Cultured cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and harvested by scraping into lysis buffer (Pierce) containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors and a phosphatase inhibitor (Invitrogen). The protein concentration was assessed with a BCA protein kit (Beyotime). Western blot analyses were performed according to traditional methods. In brief, samples containing a similar amount of protein were loaded onto an SDS-PAGE gel and electrophoresed, after which the separated proteins were blotted onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The membrane was blocked with TBST (0.05% Tween-20 in TBS) containing 5% skim milk. Then, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight (anti-p-Smad1, Cell Signaling Technology, #13820; anti-Smad1, Cell Signaling Technology, #12430; anti-GAPDH, Cell Signaling Technology, #5174; anti-p-AKT, Cell Signaling Technology, #4060; anti-AKT, Cell Signaling Technology, #9272; anti-p-AMPK, Cell Signaling Technology, #50081; anti-AMPK, Cell Signaling Technology, #5832; anti-p-p38 MAPK, Cell Signaling Technology, #4511; anti-p38 MAPK, Cell Signaling Technology, #8690; anti-ATOH8, Abcam, # ab106377; anti-Flag, Cell Signaling Technology, #14793; and anti-GFP, Cell Signaling Technology, #2956). After washing three times in TBST, the membrane was incubated with fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hours at room temperature. Western blot bands were visualized by Odyssey infrared imaging. GAPDH was detected as an internal control.

Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) assays

Co-IP assays were performed as described previously [12]. After washing with PBS, cells were lysed and coimmunoprecipitated using the Co-IP Kit (Pierce) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Then, the lysate was centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with IgG or the suitable antibody for IP. After washing with buffer containing NP-40 three times, the immunocomplexes were then detected with a targeted protein antibody by western blot analysis.

Immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy

A549 cells were grown on glass slides and washed in PBS three times. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde on slides for 30 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 0.03% Triton X-100 for 10 min to allow permeabilization and then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Cells were covered with secondary antibody. A confocal laser scanning microscope (LSM 780; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) was then used to analyze the fluorescence signal.

Migration and invasion assays

Transwell assays were performed to assess the ability of cells to migrate and invade. A total of 5 × 104 cells were seeded in the wells of a Transwell unit (5.0-μm pores; Corning Costar, Corning, NY, USA). Serum-free medium was added to the upper part of each Transwell well, and medium containing 10% fetal calf serum (FBS) used to fill the lower part. After incubation for 24 h, the upper part of each Transwell well was removed, and the nonmigrated cells were removed with a cotton swab. Migrated cells on the membrane were fixed and stained with crystal violet. The cells in five random views were counted to determine the number of migrated cells. In addition, Falcon® inserts with a 5 μm pore size coated with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, USA) were used to assess the invasive ability of the cells. All assays were performed in triplicate.

Real-time cell analysis

A real-time cell analyzer (RTCA) system was also used to monitor cell migration with cell migration plates, which provided label-free, real-time biosensor measurements, and kinetic imaging of the same live cell populations, independently, or simultaneously. It monitors cell health, adhesion, morphology, proliferation, and cytolysis in primary or native cells alone, providing unprecedented insight into cellular mechanisms and functionality. Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI) medium containing 10% FBS was placed in the bottom chamber. The upper chamber was mounted, and 30 μL of serum-free medium was added to each well, after which cells were maintained at 37°C and 5% CO2. Readings were recorded at 30-minute intervals until the end of the experiment (up to 36 hours).

Measurements of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and cellular metabolism

Flow cytometry was used to measure mitochondrial ROS in living cells. ROS were stained with a CellROX Deep Red Reagent Kit (Life Technologies Corporation). The difference in ROS levels between the two groups at each time point was calculated by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI).

The extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) were used with a Seahorse XF96 analyzer (Seahorse Bioscience Inc., North Billerica, MA, USA) to measure cellular metabolism. A549 cells were plated into XF96 (V3) polystyrene cell culture plates at 10000 cells per well and incubated for 24 hours in a 37°C incubator with 5% CO2. Cell numbers were detected after trypsin digestion and used to normalize when determining the OCR/ECAR. Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Assay medium containing all compounds at the appropriate concentration was prepared.

Xenograft experiments and immunohistochemistry

Twelve female BALB/c nude mice (4-5 weeks of age, 18-22 g) purchased from Beijing Weitong Lihua Co., Ltd. were housed and fed in the animal center of Nanjing Medical University. After one week, the mice were divided into two groups and treated with A549 cells (1 × 107) transfected with lentivirus-CYP3A5 or lentivirus-scramble (NC) by intravenous injection. The nude mice were subjected to dynamic imaging of GFP biofluorescence, and the weights of the mice were measured. After one month, the nude mice were sacrificed, and their lungs were dissected for immunohistochemistry. After deparaffinization, rehydration and antigen retrieval, serial section slides were blocked with 3% H2O2 for 10 min and incubated with anti-p-Smad1 and anti-CYP3A5 antibodies (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at 4°C overnight. The immunoreactive cells in several visual fields of each slide were observed under a microscope. Care of the laboratory animals and animal experimentation were carried out in accordance with the animal ethics guidelines of Nanjing Medical University Affiliated Cancer Hospital via approved protocols.

Statistical analysis

Student’s t-test was performed to compare means between two groups. One-way ANOVA was used to assess differences between the means of more than two groups. P<0.05 indicated statistical significance. All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY).

Results

CYP3A5 is markedly decreased in LUAD

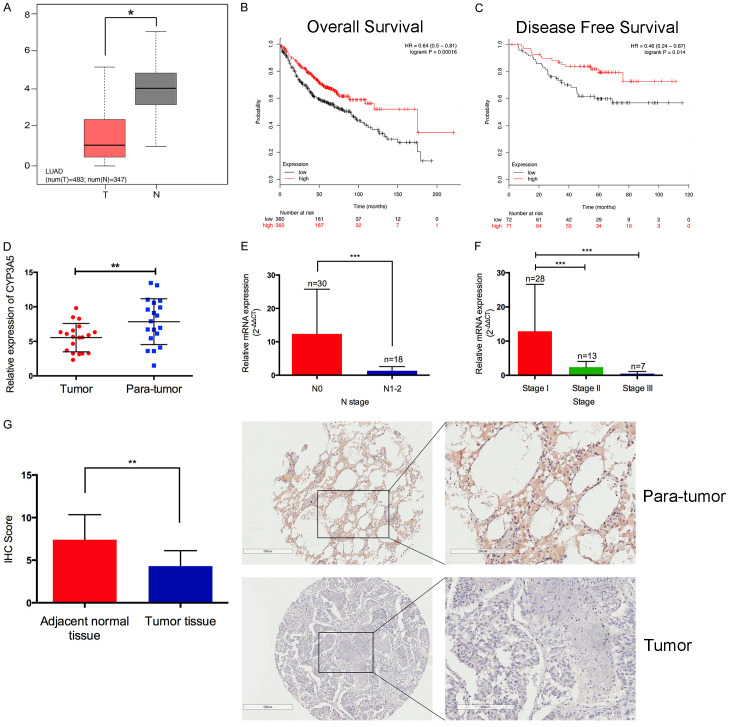

Based on TCGA dataset, we identified that CYP3A5 was remarkably down-regulated in LUAD tumor tissues compared with normal tissues by the web-based tool Oncomine (Figure 1A). Survival analysis indicated that patients with low expression of CYP3A5 had shorter overall survival and progression free survival than those with high expression (Figure 1B, 1C), which revealed that CYP3A5 was downregulated and correlated with progression in LUAD and might be be a prognostic biomarker of LUAD. In addition, we found that CYP3A5 was generally decreased in all cancers, including lung cancer (Figure S1A). Compared with other adenocarcinomas, LUAD showed extremely decreased expression (Figure S1B), which was further validated in several datasets (Figure S1C, S1D). WGCNA was performed in TCGA LUAD datasets. Several gene modules were identified, and the correlations between these modules and clinical data were calculated (Figure S1E, S1F). Notably, the brown module tended to be significantly associated with cancer stage (Figure S1G), and we found that CYP3A5 was a hub gene of the brown module, indicating that CYP3A5 might be strongly correlated with the progression of LUAD.

Figure 1.

A. Differential expression of CYP3A5 in TCGA-LUAD dataset. B, C. Overall survival and progression-free survival indicated that patients with low expression of CYP3A5 showed poor prognosis compared to those with high expression. D. qPCR analysis identified that CYP3A5 was down-regulated in the major part of cases. E, F. Low expression of CYP3A5 was correlated with lymph node metastasis and TNM stages. G. The expression of CYP3A5 was down-regulated in lung adenocarcinoma by IHC analysis on tissue microarrays.

Clinical validation was performed in 48 paired LUAD samples from our biobank. The qRT-PCR results indicated that among 32 cases, CYP3A5 expression was lower in tumor tissues (Figure 1D). In addition, YP3A5 was expressed at lower levels in cases with lymph node metastasis than in cases without lymph node metastasis, and the expression of CYP3A5 was negatively correlated with the clinical stage of LUAD (Figure 1E, 1F). The IHC results further confirmed a similar trend at the protein level (Figure 1G).

Ectopic expression of CYP3A5 inhibited the migration and invasion of LUAD cells in vitro

To further identify the function of CYP3A5 in LUAD, we evaluated the influence of CYP3A5 on the malignant phenotype in cell lines. We assessed the endogenous expression of CYP3A5 in LUAD cell lines, which revealed that CYP3A5 was aberrantly downregulated in A549 and H1975 cells (Figure S2A, S2B). Based on their tumorigenic potential and CYP3A5 expression level, we selected the A549 and H1975 cell lines to perform our further experiments. We used lentivirus to construct cells lines stably expressing CYP3A5 and confirmed the efficiency of transfection by qRT-PCR and western blot analysis (Figure S2C, S2D).

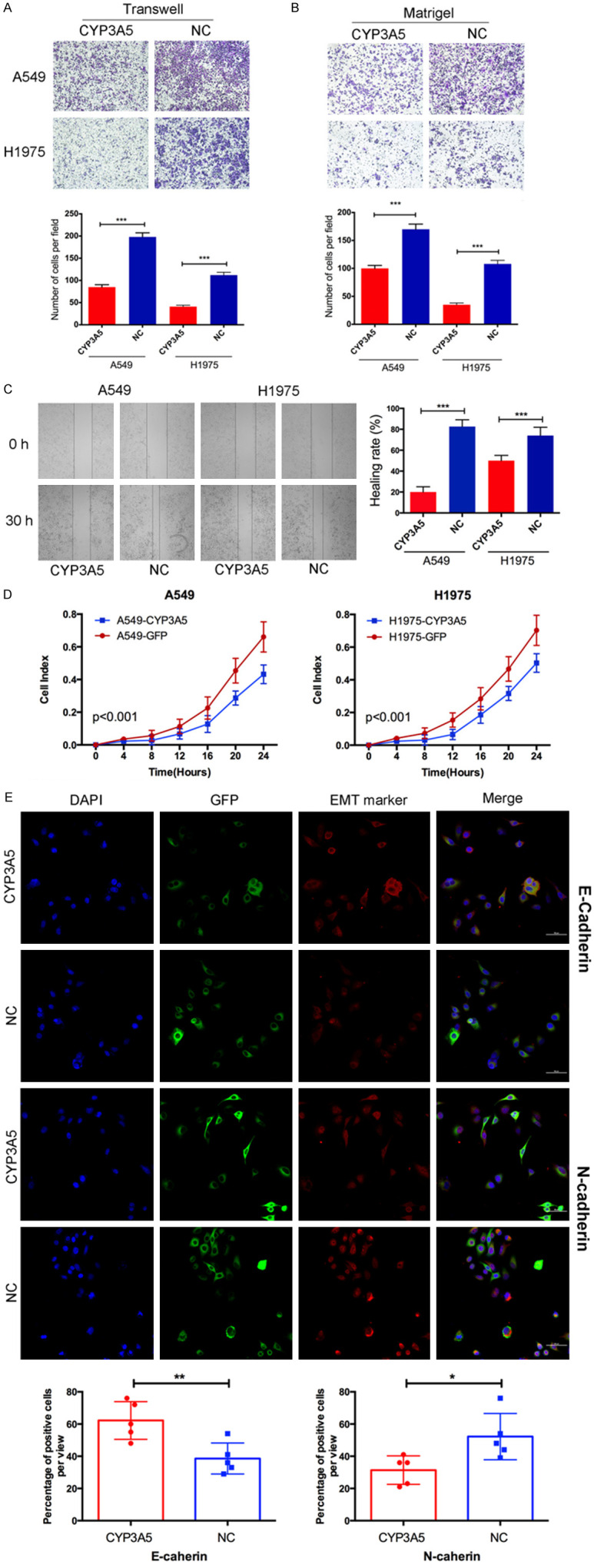

Then, we performed Transwell, Matrigel, wound-healing, and RTCA assays to assess the effect of CYP3A5 on cell metastasis. As shown, overexpression of CYP3A5 significantly inhibited the metastasis of LUAD cells (Figure 2A, 2B). A wound-healing assay showed that overexpression of CYP3A5 could impede the invasive ability of the cells (Figure 2C). The RTCA assay further validated the suppressive effects of CYP3A5 on the metastasis of LUAD cells (Figure 2D). Moreover, epithelial-mesenchymal transition markers were analyzed in CYP3A5-overexpressing cells and negative control cells using immunofluorescence. The results indicated that the E-cadherin expression level was increased, while N-cadherin expression levels were decreased in CYP3A5-overexpressing A549 cells compared to control cells (Figure 2E). These findings suggest that overexpression of CYP3A5 could inhibit invasion and migration in vitro. No obvious difference in other malignant phenotypes (proliferation, apoptosis, and the cell cycle) between LUAD cells with and without CYP3A5 overexpression.

Figure 2.

CYP3A5 inhibited metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma in vitro. (A, B) Transwell and matrigel assay identified the capacity of migration. Statistical results were shown as the means ± SD. (C) Wound healing assay and (D) RTCA assay was used to assess the invasion and migration of LUAD cells in different manners. (E) A, Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) markers were analyzed in cells overexpression circCRIM1 using immunofluorescence.

Ectopic expression of CYP3A5 inhibited the migration and invasion of lung adenocarcinoma in vivo

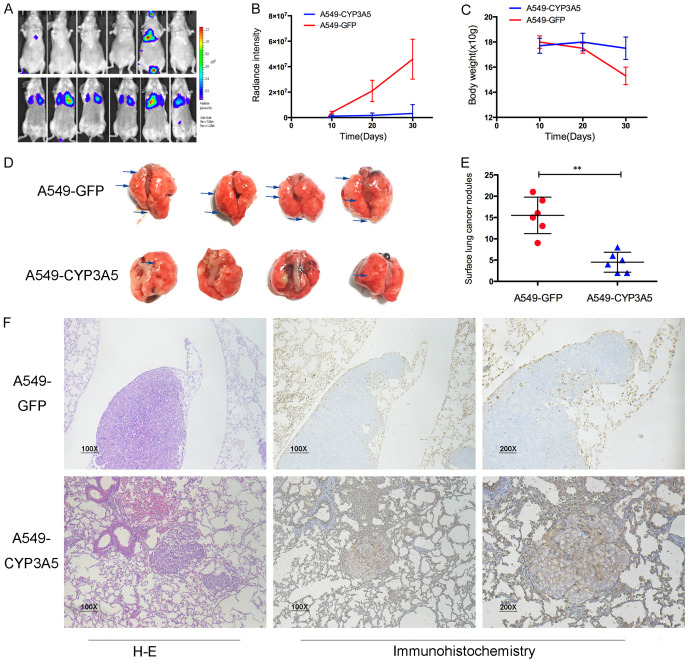

We next validated the effect of CYP3A5 on metastasis in a xenograft model. Mice were randomized into two groups, and half of the mice were injected with luciferase-expressing A549-CYP3A5 cells through the tail vein. Beginning on day 45, via bioluminescent imaging, we observed significantly reduced fluorescence intensity in mice in the A549-CYP3A5 group compared with the scramble group, indicating that metastasis was suppressed in the A549-CYP3A5 group (Figure 3A, 3B). In addition, the weight of each mouse was detected every ten days, and the weight of mice in the scramble group was remarkably decreased compared with that of mice in the A549-CYP3A5 group (Figure 3C). The lungs of the mice in each group were obtained after their sacrifice on day 45 after injection. Significantly fewer visible surface nodules were observed in the A549-CYP3A5 group than in the scramble group (Figure 3D, 3E). Furthermore, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining confirmed that the lung nodules were metastatic tumor nests and demonstrated that overexpression of CYP3A5 decreased the diameter and volume of lung metastatic nodules compared to those in the scramble group (Figure 3F). IHC showed that CYP3A5 was upregulated in lung metastatic nodules in the A549-CYP3A5 group and downregulated in those in the scramble group, indicating that CYP3A5 inhibited the metastasis of LUAD in vivo.

Figure 3.

CYP3A5 inhibited metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma in vivo. A. Lung metastasis model in nude mice was injected with lv-CYP3A5 cells or control cells in the tail vein. Representative image of luciferase signals derived from lung metastatic nodules. B. The intensity of luciferase was statistically analyzed. C. The weight of mice was weighted per 10 days. D. Representative images of lung metastatic nodules. E. The number of metastatic nodules was quantified. F. HE-stained sections and IHC sections were shown.

Overexpression of CYP3A5 suppressed the p-Smad1 signaling pathway

We investigated the underlying mechanism of CYP3A5-mediated inhibition of LUAD metastasis. Based on the biological function of CYP3A5 and a literature review, CYP3A5 might affect the intracellular ROS level and cellular metabolism, in turn manipulating the progression of malignant tumors [8,13]. However, a flow cytometry experiment showed no significant difference in the intracellular ROS level with and without CYP3A5 overexpression (Figure S3A, S3B). In addition, assays to detect the OCR and ECAR revealed that overexpression of CYP3A5 did not alter cellular glycolysis or oxidation in the respiratory chain (Figure S3C, S3D). These findings indicated that changes in neither intracellular ROS levels nor cellular glycolysis and oxidation are responsible for the CYP3A5-mediated suppression of metastasis in LUAD.

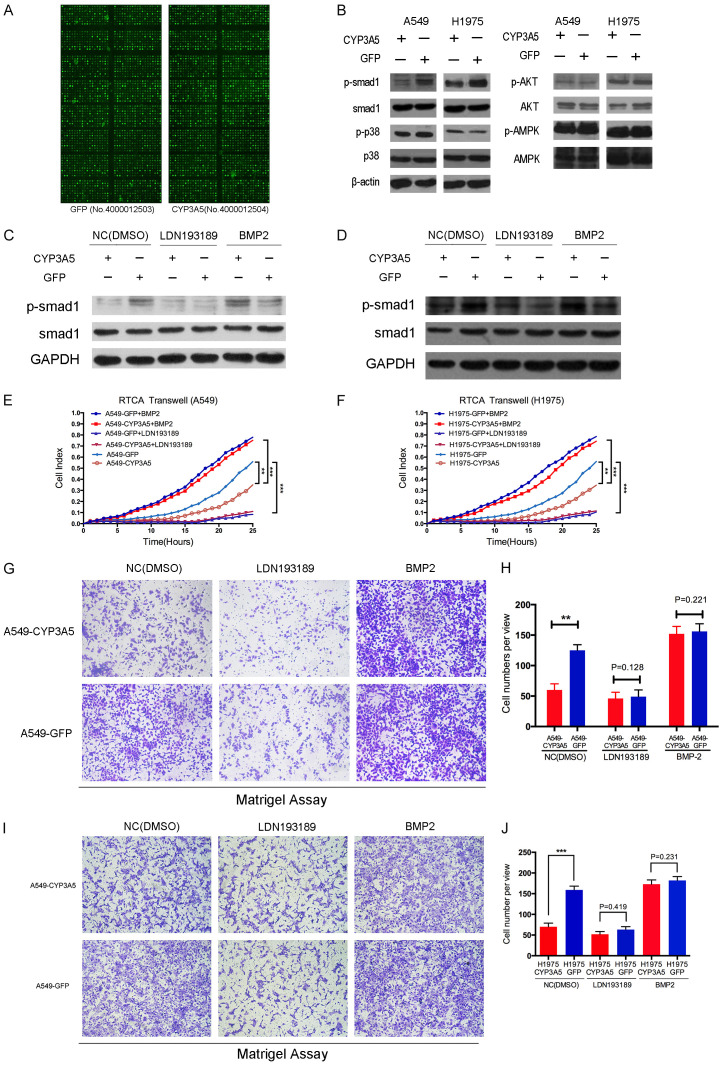

A comprehensive approach using a phospho-antibody microarray provided a high-throughput platform to efficiently profile protein phosphorylation status (Full Moon BioSystems Inc.), avoiding inefficiency and incorrect results. Using this approach, we detected and analyzed phosphorylation events at 1318 specific sites using the PEX100 array to explore the potential downstream effectors of CYP3A5 (Figure 4A). Performing the array with cell lysates from A549-CYP3A5 and A549-GFP cells, we identified a spectrum of key molecules whose phosphorylation levels were remarkably decreased by more than 50% compared to those in the negative control cells; these molecules included AKT1, MAPK p38, AMPK, and Smad1 (Table S1). Subsequently, dramatic variation in the phosphorylated sites in the two cell lines (A549 and H1975 cells) were validated by western blotting (Figure 4B), which indicated remarkable and consistent alteration in the phosphorylation of Smad1 with and without ectopic expression of CYP3A5.

Figure 4.

CYP3A5 suppresses the Smad1 pathway in lung adenocarcinoma. A. PEX100 antibody-based microarray. B. The level of phospho-Smad1, phospho-p38, phosphor-AMPK, and phosphor-AKT with corresponding total protein in negative control cells versus CYP3A5 over-expression cells. C, D. Two cell lines A549 and H1975, transfected with lv-CYP3A5 and lv-NC, were treated with Smad1 inhibitors and activator, LDN193189 (200 nM) and recombinant BMP2 (20 ng/ul). Phosphorylation of Smad1 protein was examined by western blot analysis. E-J. The cells were subjected to the RTCA transwell assay and migration assay in order to measure the capacity of cell metastasis.

A specific inhibitor (LDN193189) and activator (recombinant bone morphogenetic protein 2, BMP2) of p-Smad1 were used to further confirm whether CYP3A5-induced inhibition of LUAD metastasis depends on the Smad1 signaling pathway. LDN193189 considerably inhibited the phosphorylation level of Smad1 in the scramble group, but this decrease in phosphorylated Smad1 was rescued by recombinant BMP2 in the group in which CYP3A5 was overexpressed (Figure 4C, 4D). RTCA, Transwell and Matrigel assays demonstrated that the activation of smad1 in A549 cells remarkably reversed inhibition of invasion and migration by the overexpression of CYP3A5 (Figure 4E, 4G, 4H). Furthermore, inhibition of Smad1 phosphorylation decreased the ability of cells to metastasize and abolished the difference in metastasis between the group in which CYP3A5 was overexpressed and the scramble group. The H1975 cell line showed a similar tendency, confirming these results (Figure 4F, 4I, 4J).

The interaction of CYP3A5 and ATOH8 results in inactivation of the Smad1 signaling pathway

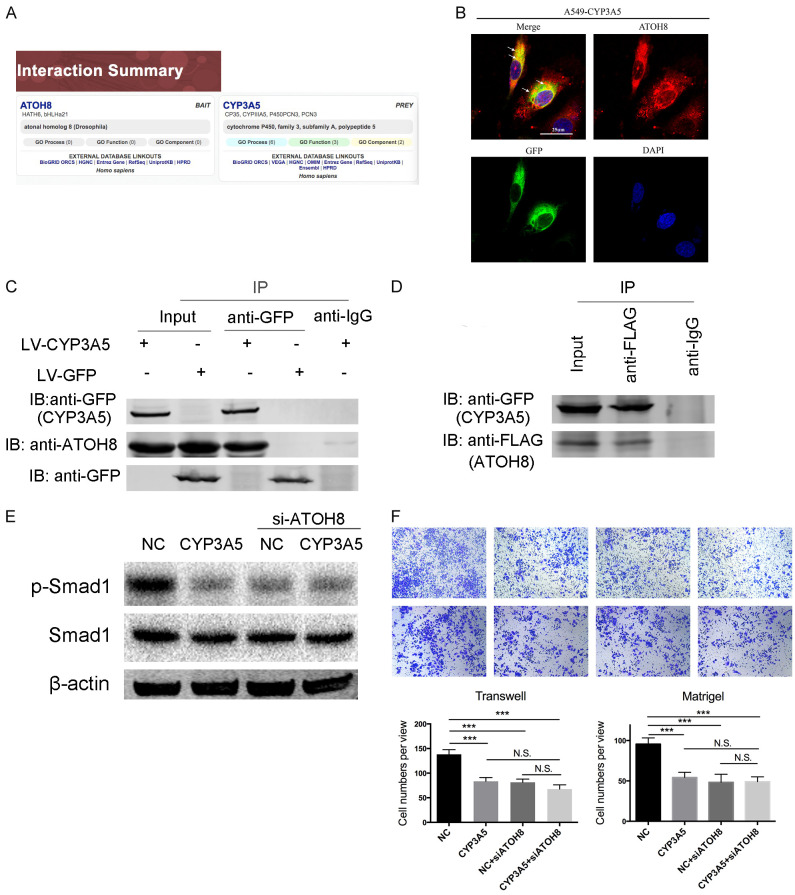

To explore the mechanism of CYP3A5-mediated regulation of the Smad1 pathway, we first examined the potential regulatory roles of the Smad1 pathway. Published research noted that ATOH8 could specifically regulate the phosphorylation of Smad1 [14,15]. In addition, we found that ATOH8 could interact with CYP3A5 in liver tissue, which was demonstrated by high-throughput two-hybrid system techniques [16] (Figure 5A). Therefore, we hypothesized that CYP3A5 interacts with ATOH8 in the lung, resulting in inhibition of the Smad1 signaling pathway. We separately detected the phosphorylation of Smad1 in ATOH8-knockdown and ATOH8-knockin LUAD cells, the results of which indicated that ATOH8 could regulate the phosphorylation of Smad1 (Figure S3E). Immunofluorescence confocal experiments revealed the colocalization of CYP3A5 and ATOH8, indicating the probability of their physical interaction (Figure 5B). Then, co-IP experiments revealed that the CYP3A5-GFP protein can interact with endogenous ATOH8, while no obvious binding was observed in the GFP-expressing cell line (Figure 5C). To further confirm this result, we transfected flag-tagged ATOH8 into the A549 cell line. As shown, a co-IP assay showed that ATOH8-Flag could bind CYP3A5, confirming their interaction (Figure 5D). Moreover, interference with the expression of ATOH8 in ectopic CYP3A5 LUAD cells did not decrease the phosphorylation of Smad1 compared with that in control ectopic CYP3A5 LUAD cells (Figure 5E). A rescue assay illustrated that ATOH8 knockdown in ectopic CYP3A5 cells did not further inhibit the metastatic ability of LUAD cells (Figure 5F).

Figure 5.

Over-expression of CYP3A5 could interact with ATOH8. A. Website prediction of the interaction between CYP3A5 and ATOH8. B. A549-CYP3A5 Cells were fixed for the immunofluorescence analysis. CYP3A5-GFP fusion protein was detected using an anti-GFP primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-mouse antibody, and ATOH8 was detected using an anti-ATOH8 primary antibody and Alexa Fluor 594 goat anti-rabbit antibody. Representative cells from the same field for each experimental group are shown. C. Co-IP showed that CYP3A5 interacted with ATOH8 in A549-CYP3A5 cells, but not in A549-GFP cells. D. A549-CYP3A5 was transfected with Flag-tagged ATOH8, and the interaction between ATOH8 and CYP3A5 was determined by IP and immunoblotting. E. Phosphorylation of Smad1 was assessed after knock down ATOH8 in ectopic CYP3A5 and control cells. F. Transwell and matrigel assays were utilized to assess the metastasis ability after knock down ATOH8 in ectopic CYP3A5 and control cells.

Prognostic value of the combination of CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 in LUAD

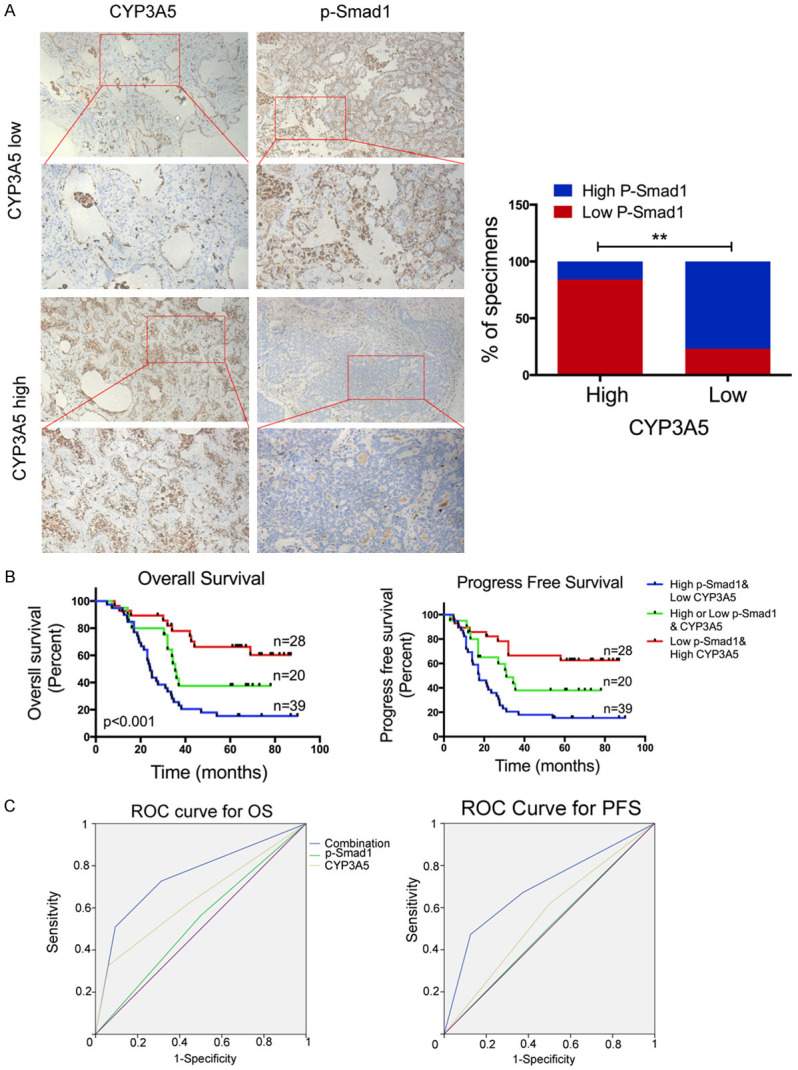

Based on the mechanism above, we proceeded to explore the clinical relevance of CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 in our study. An IHC assay to detect CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 was performed using a LUAD microarray and indicated a positive correlation between the expression of CYP3A5 and the activity of Smad1 (Figure 6A). We aimed to generate a novel IHC panel to test the ability of CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 combined to predict the prognosis of LUAD. The patient demographic information was listed in Table S3. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank test suggested that patients with high CYP3A5 expression and low Smad1 activity had better overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) (Figure 6B). Moreover, the combination indexes of CYP3At and p-Smad1 determined through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis showed an additive predictive value for overall survival compared with that for either of the individual markers (combination ROC area: 0.753 for OS, 0.695 for DFS) (Figure 6C). This provided us with a reliable IHC panel with which to evaluate the prognosis of LUAD patients.

Figure 6.

Prognostic value of combining CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 in lung adenocarcinoma. A. Representative images showing high or low expression of CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 in 87 LUAD tumor specimens. Correlation between CYP3A5 and p-Smad1 in LUAD microarray specimens (right panel). B. Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival (OS) based on the molecular markers (Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test). CYP3A5 expression and the activity of p-Smad1 were stratified by the individual medians by IHC analysis, and the patients were divided into three groups as indicated. C. ROC curve analysis for OS for combined panel [AUC = 0.753, (95% CI, 0.721-0.769)], CYP3A5 [AUC = 0.643, (95% CI, 0.617-0.671)], and p-Smad1 [AUC = 0.532, (95% CI, 0.505-0.579)] as individual biomarkers, AUC, area under the curve, P<0.05; ROC curve analysis for DFS for combined panel [AUC = 0.695, (95% CI, 0.664-0.725)], CYP3A5 [AUC = 0.559, (95% CI, 0.525-0.593)], and p-Smad1 [AUC = 0.505, (95% CI, 0.478-0.569)] as individual biomarkers.

Discussion

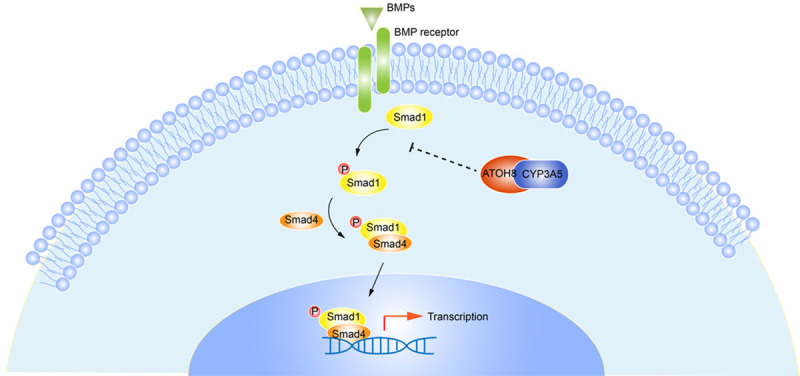

LUAD is a heterogenetic disease and complex process in which multiple cellular factors and genes in turn influence the malignant phenotype [1,2,17,18]. Thus, it is of great theoretical and practical importance to clarify aberrant gene expression patterns in lung cancer carcinogenesis, which might provide novel insight into translational medicine. P450 family proteins are primarily known as key enzymes related to metabolic processes, including the metabolism of endogenous and exogenous substrates [8]. However, several genes of the P450 family were found to be aberrantly expressed in tumors and involved in various oncogenic processes. CYP2C9 plays a direct protective role against non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) development by decreasing EET biosynthesis [19]. Another investigation showed that cytochrome P450 2E1 mediates trichloroethylene (TCE) metabolism to promote γ-H2AX generation via ROS production [20]. The clinical impact of CYP3A5 was first reported in liver cancer, in which low expression of CYP3A5 at the transcript and protein levels was shown to contribute to worse overall survival and the metastasis of liver cancer [8,21]. Upregulation of CYP3A5 in prostate cancer was found to be associated with prostate cancer cell growth by facilitating the nuclear translocation of androgen receptor (AR) [7]. In this study, we evaluated the expression of CYP3A5 in multiple cancers and found that CYP3A5 was aberrantly expressed at low levels in lung cancer. WGCNA showed that CYP3A5 is correlated with TNM stage in LUAD. Overexpression of CYP3A5 inhibited the migration and invasion of LUAD in vitro and in vivo. A mechanistic investigation found that overexpression of CYP3A5 suppressed phosphorylation of the Smad1 protein, mediating the inhibition of metastasis. Furthermore, a literature review and co-IP experiment confirmed that CYP3A5 could interact with ATOH8, inhibiting the Smad1 pathway (Figure 7). These findings suggest that CYP3A5 is involved in the metastasis of LUAD.

Figure 7.

Schematic diagram of how CYP3A5 inhibits metastasis of lung adenocarcinoma.

CYP3A5 is a metabolic enzyme responsible for the metabolism of endogenous steroids and exogenous drugs [5]. A published article revealed that CYP3A5 could produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which serve as cellular second messengers to activate or inhibit signaling pathways, as side products when it metabolized its substrates [8]. Thus, we assessed whether CYP3A5 has the same function in LUAD. Flow cytometry identified no significant difference in ROS levels between the group in which CYP3A5 was overexpressed and the negative control group. In addition, several drug-metabolizing enzymes are involved in mitochondrial energy metabolism [22,23]. However, assays revealed no obvious difference in the ECAR or OCR when CYP3A5 was upregulated, which indicated that CYP3A5 does not play a role in cellular glycolysis or the oxidative respiratory chain. To uncover the potential effect of CYP3A5 on metastasis in LUAD, we identified multiple prometastatic proteins whose phosphorylation levels are downregulated by CYP3A5 in LUAD cells by a microarray-based proteomics method to efficiently screen potential mechanisms. In this study, a phospho-antibody microarray-based method revealed that the phosphorylation levels of AKT, p38, AMPK, and Smad1/5/8 were remarkably decreased upon the overexpression of CYP3A5 in A549 cells. BMP/Smad1 signaling is controlled by the TGFβ pathway, which is activated in multiple cancer types and plays significant roles in a diverse range of oncogenic phenotypes. A literature review found that activation of the Smad1 protein exerts its oncogenic function through binding DNA and modulating its transcription with other transcription factors in the cellular nucleus [24]. In the current study, we observed that overexpression of CYP3A5 resulted in decreased Smad1 phosphorylation and Smad1 inactivation. Reciprocal rescue experiments confirmed that CYP3A5-mediated regulation of LUAD metastasis depends on decreased Smad1 phosphorylation. Therefore, the results of our phospho-antibody microarray-based experiments pave the way to develop a novel mechanism to mediate CYP3A5-dependent prometastatic signals.

Activation of the BMP/Smad1 signaling pathway depends on the binding of BMP ligands to specific serine/threonine kinase transmembrane receptors, activating intracellular Smad1 proteins [25]. The stability of phosphorylated Smad1 was found to be modified by Smurf proteins via the ubiquitination pathway or dephosphorylation by phosphatases [26]. Phosphorylation of Smad1 at Ser463/465 dictates its ability to translocate into the cellular nucleus, mediating its functional contact with the basal transcriptional machinery. However, our preliminary experiment showed that the overexpression of CYP3A5 did not affect the expression of the ligand BMP or the smurf protein. In addition, no specific Smad1 phosphatases are described in the published literature.

ATOH8, a transcription factor that binds the E-box element, has been implicated in inducing stem cell features [27], inhibiting tumor phenotypes [28], and stimulating myogenesis [29]. Song et al found that ATOH8 served as a tumor suppressor that induced stem cell features and chemoresistance in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) cells. In HEK293 cells, ATOH8 appeared to increase phosphorylated Smad1/5/8 levels [14]. Another study also showed that ATOH8 could increase the phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 [15]. Furthermore, Wang et al found that ATOH8 could interact with CYP3A5 with a two-hybrid system [16]. Our experiment confirmed that CYP3A5 could interact with ATOH8 to mediate the inhibition of metastasis of LUAD, providing a novel mechanism for the involvement of CYP3A5 with metastasis in LUAD. This mechanism is shown in Figure 7.

The phenotype and mechanism of CYP3A5 in LUAD were thoroughly investigated, but the limitations of this study should be noted. For example, the effects of ATOH8 on the migration and invasion of LUAD cells need to be further investigated. The mechanism by which ATOH8 regulates the phosphorylation of Smad1 is still unknown. Clinical analysis could be carried out to evaluate the correlation between the expression of CYP3A5 and ATOH8.

In summary, herein, we demonstrated that overexpression of CYP3A5 effectively inhibited the metastasis of LUAD cells. These data provide proof that not only suggests the therapeutic potential of CYP3A5 in LUAD but also demonstrates the novel mechanism of CYP3A5 in cancer metastasis. Furthermore, we found that CYP3A5 was likely involved in LUAD tumor metastasis in a xenograft mouse model. Together, our results not only suggest a novel target to inhibit metastasis in LUAD but also provide novel insight into CYP3A5 in carcinogenesis.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81472702, 81501977, 81702892 and 81672294), the Science Foundation for Outstanding Youth scholars of Jiangsu Province (BK20160100); The Project of Invigorating Health Care through Science, Technology Education (2016KJQWLJRC-02); Funded by Jiangsu Provincial key research development program (BE2017761); 333 Project of Jiangsu Province (BRA2015); “Six One Project” Research Project for High-level Talents in Jiangsu Province (LGY2017086); Ministry of Health of China Wu Jieping Medical Foundation (320.6799.15056). We greatly appreciate Prof. Junhai Han and Dr. Xiaoyan Zhang (Institute of Life Sciences, the Collaborative Innovation Center for Brain Science, Southeast University, Nanjing, China.) kindly help for instruction of method and study design.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Mao Q, Xia W, Dong G, Chen S, Wang A, Jin G, Jiang F, Xu L. A nomogram to predict the survival of stage IIIA-N2 non-small cell lung cancer after surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2018;155:1784–1792. e1783. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2017.11.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang LP, Zhu ZT, He CY. Effects of CYP3A5 genetic polymorphism and smoking on the prognosis of non-small-cell lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:1461–1469. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S94144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo-Tsukude C, Sasaki JI, Saeki S, Iwamoto N, Inaba M, Ushijima S, Kishi H, Fujii S, Semba H, Kashiwabara K, Tsubata Y, Hayashi M, Kai Y, Saito H, Isobe T, Kohrogi H, Hamada A. Population pharmacokinetics and adverse events of erlotinib in Japanese patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: impact of genetic polymorphisms in metabolizing enzymes and transporters. Biol Pharm Bull. 2018;41:47–56. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b17-00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Guo Z, Johnson V, Barrera J, Porras M, Hinojosa D, Hernández I, McGarrah P, Potter DA. Targeting cytochrome P450-dependent cancer cell mitochondria: cancer associated CYPs and where to find them. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2018;37:409–423. doi: 10.1007/s10555-018-9749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Woodland C, Huang TT, Gryz E, Bendayan R, Fawcett JP. Expression, activity and regulation of CYP3A in human and rodent brain. Drug Metab Rev. 2008;40:149–68. doi: 10.1080/03602530701836712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mitra R, Goodman OB. CYP3A5 regulates prostate cancer cell growth by facilitating nuclear translocation of AR. Prostate. 2015;75:527–538. doi: 10.1002/pros.22940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jiang F, Chen L, Yang YC, Wang XM, Wang RY, Li L, Wen W, Chang YX, Chen CY, Tang J, Liu GM, Huang WT, Xu L, Wang HY. CYP3A5 functions as a tumor suppressor in hepatocellular carcinoma by regulating mTORC2/Akt signaling. Cancer Res. 2015;75:1470–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lu TP, Hsiao CK, Lai LC, Tsai MH, Hsu CP, Lee JM, Chuang EY. Identification of regulatory SNPs associated with genetic modifications in lung adenocarcinoma. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8:92. doi: 10.1186/s13104-015-1053-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Landi MT, Dracheva T, Rotunno M, Figueroa JD, Liu H, Dasgupta A, Mann FE, Fukuoka J, Hames M, Bergen AW, Murphy SE, Yang P, Pesatori AC, Consonni D, Bertazzi PA, Wacholder S, Shih JH, Caporaso NE, Jen J. Gene expression signature of cigarette smoking and its role in lung adenocarcinoma development and survival. PLoS One. 2008;3:e1651. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mao Q, Zhang L, Zhang Y, Dong G, Yang Y, Xia W, Chen B, Ma W, Hu J, Jiang F, Xu L. A network-based signature to predict the survival of non-smoking lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:2683–2693. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S163918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertrand MJ, Milutinovic S, Dickson KM, Ho WC, Boudreault A, Durkin J, Gillard JW, Jaquith JB, Morris SJ, Barker PA. cIAP1 and cIAP2 facilitate cancer cell survival by functioning as E3 ligases that promote RIP1 ubiquitination. Mol Cell. 2008;30:689–700. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noll EM, Eisen C, Stenzinger A, Espinet E, Muckenhuber A, Klein C, Vogel V, Klaus B, Nadler W, Rösli C, Lutz C, Kulke M, Engelhardt J, Zickgraf FM, Espinosa O, Schlesner M, Jiang X, Kopp-Schneider A, Neuhaus P, Bahra M, Sinn BV, Eils R, Giese NA, Hackert T, Strobel O, Werner J, Büchler MW, Weichert W, Trumpp A, Sprick MR. CYP3A5 mediates basal and acquired therapy resistance in different subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Med. 2016;22:278–287. doi: 10.1038/nm.4038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel N, Varghese J, Masaratana P, Latunde-Dada GO, Jacob M, Simpson RJ, McKie AT. The transcription factor ATOH8 is regulated by erythropoietic activity and regulates HAMP transcription and cellular pSMAD1,5,8 levels. Br J Haematol. 2014;164:586–96. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kautz L, Meynard D, Monnier A, Darnaud V, Bouvet R, Wang RH, Deng C, Vaulont S, Mosser J, Coppin H, Roth MP. Iron regulates phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 and gene expression of 13rap6, SmadT, Idl, and Atoh8 in the mouse liver. Blood. 2008;112:1503. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-143354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang J, Huo K, Ma L, Tang L, Li D, Huang X, Yuan Y, Li C, Wang W, Guan W, Chen H, Jin C, Wei J, Zhang W, Yang Y, Liu Q, Zhou Y, Zhang C, Wu Z, Xu W, Zhang Y, Liu T, Yu D, Zhang Y, Chen L, Zhu D, Zhong X, Kang L, Gan X, Yu X, Ma Q, Yan J, Zhou L, Liu Z, Zhu Y, Zhou T, He F, Yang X. Toward an understanding of the protein interaction network of the human liver. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:536–536. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qixing M, Gaochao D, Wenjie X, Anpeng W, Bing C, Weidong M, Lin X, Feng J. Microarray analyses reveal genes related to progression and prognosis of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2017;8:78838–78850. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mao Q, Jiang F, Yin R, Wang J, Xia W, Dong G, Ma W, Yang Y, Xu L, Hu J. Interplay between the lung microbiome and lung cancer. Cancer Lett. 2018;415:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sausville LN, Gangadhariah M, Chiusa M, Mei S, Wei S, Zent R, Luther JM, Shuey MM, Capdevila JH, Falck JR, Guengerich FP, Williams SM, Pozzi A. The cytochrome P450 slow metabolizers CYP2C9*2 and CYP2C9*3 directly regulate tumorigenesis via reduced epoxyeicosatrienoic acid production. Cancer Res. 2018;78:4865–4877. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-3977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Toyooka T, Yanagiba Y, Ibuki Y, Wang RS. Trichloroethylene exposure results in the phosphorylation of histone H2AX in a human hepatic cell line through cytochrome P450 2E1-mediated oxidative stress. J Appl Toxicol. 2018;38:1224–1232. doi: 10.1002/jat.3632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu T, Wang X, Zhu G, Han C, Su H, Liao X, Yang C, Qin W, Huang K, Peng T. The prognostic value of differentially expressed CYP3A subfamily members for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:1713–1726. doi: 10.2147/CMAR.S159425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adam AAA, van der Mark VA, Donkers JM, Wildenberg ME, Oude Elferink RPJ, Chamuleau RAFM, Hoekstra R. A practice-changing culture method relying on shaking substantially increases mitochondrial energy metabolism and functionality of human liver cell lines. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0193664. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0193664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Legendre C, Hori T, Loyer P, Aninat C, Ishida S, Glaise D, Lucas-Clerc C, Boudjema K, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Corlu A, Morel F. Drug-metabolising enzymes are down-regulated by hypoxia in differentiated human hepatoma HepaRG cells: HIF-1alpha involvement in CYP3A4 repression. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:2882–92. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu H, Bao D, Xia X, Chau JF, Li B. An unconventional role of BMP-Smad1 signaling in DNA damage response: a mechanism for tumor suppression. J Cell Biochem. 2013;115:450–456. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eikesdal HP, Becker LM, Teng Y, Kizu A, Carstens JL, Kanasaki K, Sugimoto H, LeBleu VS, Kalluri R. BMP7 signaling in TGFBR2-deficient stromal cells provokes epithelial carcinogenesis. Mol Cancer Res. 2018;16:1568–1578. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-18-0120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sapkota G, Alarcón C, Spagnoli FM, Brivanlou AH, Massagué J. Balancing BMP signaling through integrated inputs into the smad1 linker. Mol Cell. 2007;25:441–454. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Song Y, Pan G, Chen L, Ma S, Zeng T, Man Chan TH, Li L, Lian Q, Chow R, Cai X, Li Y, Li Y, Liu M, Li Y, Zhu Y, Wong N, Yuan YF, Pei D, Guan XY. Loss of ATOH8 increases stem cell features of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Gastroenterology. 2015;149:1068–1081. e1065. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Z, Xie J, Yan M, Wang J, Wang X, Zhang J, Zhang Y, Li P, Lei X, Huang Q, Lin S, Guo X, Liu Q. Downregulation of ATOH8 induced by EBV-encoded LMP1 contributes to the malignant phenotype of nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:26765–26779. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Balakrishnan-Renuka A, Morosan-Puopolo G, Yusuf F, Abduelmula A, Chen J, Zoidl G, Philippi S, Dai F, Brand-Saberi B. ATOH8, a regulator of skeletal myogenesis in the hypaxial myotome of the trunk. Histochem Cell Biol. 2014;141:289–300. doi: 10.1007/s00418-013-1155-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.