Abstract

Background

Treatment decisions for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) depend on disease severity, but the prescribing pattern by severity and drivers of therapeutic choices remain unclear.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to evaluate pharmacological treatment patterns by COVID-19 severity and identify the determinants of prescribing for COVID-19.

Methods

Using electronic health record data from a large Massachusetts-based healthcare system, we identified all patients aged ≥ 18 years hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 from 1 March to 24 May, 2020. We defined five levels of COVID-19 severity at hospital admission: (1) hospitalized but not requiring supplemental oxygen; (2–4) hospitalized and requiring oxygen ≤ 2, 3–4, and ≥ 5 L per minute, respectively; and (5) intubated or admitted to an intensive care unit. We assessed the medications used to treat COVID-19 or as supportive care during hospitalization.

Results

Among 2821 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, we found inpatient mortality increased by severity from 5% for level 1 to 23% for level 5. As compared to patients with severity level 1, those with severity level 5 were 3.53 times (95% confidence interval 2.73–4.57) more likely to receive a medication used to treat COVID-19. Other predictors of treatment were fever, low oxygen saturation, presence of co-morbidities, and elevated inflammatory biomarkers. The use of most COVID-19 relevant medications has dropped substantially while the use of remdesivir and therapeutic anticoagulants has increased over the study period.

Conclusions

Careful consideration of disease severity and other determinants of COVID-19 drug use is necessary for appropriate conduct and interpretation of non-randomized studies evaluating outcomes of COVID-19 treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40265-020-01424-7) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Key Points

| Based on a cohort of 2821 patients hospitalized for COVID-19, we found a simple COVID-19 severity scale using admission oxygen requirements and intensive care unit designation correlates well with inpatient mortality and is highly predictive of administration of COVID-19-specific medications (3.5-fold more likely to receive a drug therapy for COVID-19 in patients of highest vs lowest severity level). |

| Additional predictors of treatment were calendar time, fever, low oxygen saturation, presence of co-morbidities, and elevated inflammatory biomarkers. |

| Pharmacological treatment for patients hospitalized for COVID-19 is highly correlated with disease severity and oxygen requirement is a key driver. |

| Non-randomized studies evaluating treatment effectiveness for COVID-19 must consider these important determinants of treatment decisions for COVID-19. |

Introduction

Patients infected with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) have a wide variety of clinical manifestations. While > 80% of infected patients experience only mild illness [1], mortality rates of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) have been estimated to be 5–27% [2, 3] in vulnerable populations, including older adults and patients with multiple co-morbidities [4, 5]. For patients with mild disease, supportive care has been the preferred management strategy [6]; pharmacological treatments with possible anti-viral effects have been primarily used for patients with moderate-to-severe disease [7, 8].

Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have begun to provide evidence that certain drugs, remdesivir [8] and dexamethasone [9], can have important impacts on clinical outcomes for patients hospitalized for COVID-19. A range of medications continue to be used off-label and are under investigation to treat COVID-19, including hydroxychloroquine [10, 11], azithromycin [11, 12], darunavir/cobicistat [13], interferon-beta [14, 15], and tocilizumab [16–18]. There are also many ongoing investigations about the implication in COVID-19 management of some long-term medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) [19–21], angiotensin receptor blockers [19–21], statins [22], antibiotics or anti-viral agents for other specific viruses [23, 24], anticoagulants [25, 26], proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) [27, 28], and H2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) [27, 29].

Given the rapidity with which the COVID-19 treatment landscape is evolving, it is important to understand the determinants and patterns of pharmacological treatment over time. Such knowledge helps to contextualize the results of emerging non-randomized studies and RCTs as the “standard of care” evolves. Understanding drivers of treatment can inform the conduct and interpretation of observational studies of treatment outcomes. We aimed to evaluate utilization patterns of medications used to treat COVID-19 by disease severity defined by a modified ordinal scale commonly used in RCTs [30–32]. We also sought to identify determinants of use of treatments for COVID-19 in the inpatient setting.

Methods

Source Data

Data were drawn from Research Patient Data Registry [33], which contains electronic health records (EHRs) from Mass General Brigham [34], a large care delivery network in Massachusetts that includes facilities across the full continuum of care [34]. Mass General Brigham consists of two tertiary hospitals, 11 secondary hospitals, and > 30 ambulatory centers. The Research Patient Data Registry contains information on patient demographics, medical diagnosis and procedures, medication information, vital signs, smoking status, body mass index, immunizations, laboratory data, various clinical notes, and reports. The Mass General Brigham Human Research Committee approved the study protocol.

Study Population

We included all hospitalized patients aged 18 years and older with a positive laboratory finding confirming infection with SARS-CoV-2 in a Mass General Brigham facility from 1 March 2020 to 24 May 2020. A positive laboratory finding for SARS-CoV-2 was defined as a positive result on a real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction assay of nasal or pharyngeal swab specimens. Those with negative or indeterminant results were excluded. The cohort entry date (index date) was the date when both cohort eligibility criteria (a positive SARS-CoV-2 test and hospital admission) were met. We required the date of collection of the SARS-CoV-2 test to occur within 2 weeks prior to or during the index hospitalization. Pregnant women and those receiving hospice or comfort care prior to or at cohort entry were excluded.

Severity of COVID-19

We defined COVID-19 disease severity as follows: severity level 1, hospitalized but not requiring supplemental oxygen; level 2, hospitalized and requiring supplemental oxygen ≤ 2 L per minute (L/min); severity level 3, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy 3–4 L/min; level 4, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy ≥ 5 L/min or receiving nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, non-rebreather, or noninvasive mechanical ventilation; level 5, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU). This scale was modified from an ordinal scale commonly used in RCTs [30–32], restricting to categories relevant for hospitalized patients and further sub-dividing those receiving supplemental oxygen by oxygen flow rate because distinguishing oxygen requirements may be helpful for identifying early respiratory deterioration [35]. The cut-points for oxygen flow rates were informed by the observed distribution in the data (i.e., 2 L/min was the median flow rate in our data) and based on clinical knowledge [36].

Drug Utilization and Clinical Endpoints

We assessed medications relevant in COVID-19, including (1) COVID-19-specific medications, defined as pharmacological agents under investigation or reported to have effects against COVID-19, including remdesivir [8, 37], systemic corticosteroids [9], tocilizumab [16, 17], hydroxychloroquine [10, 11], azithromycin [11, 12], sarilumab [38], siltuximab [39], darunavir/cobicistat [13], interferon-beta [14, 15], nitric oxide [40, 41], favipiravir [42], canakinumab [43], ravulizumab [44], ibrutinib [45], anakinra [43, 46], rilonacept [47], and umifenovir [48]; and (2) medications that may be used for supportive care in patients with COVID-19, including statins [22], anti-infective agents (antibiotics, anti-fungal agents, and anti-viral agents for other specific viruses, [23, 24], anticoagulants [25, 26], inhalers/nebulizers [49], ACEIs [19–21], angiotensin receptor blockers [19–21], proton pump inhibitors [27, 28], and H2RAs [27, 29]. We assessed inpatient medication use via electronic medication administration data, which are generated when nurses scan patients’ identifying barcodes immediately before medication administration. The administration of investigational drugs (e.g., remdesivir) was also captured in the database, except when administered as part of a double-blind trial.

We also assessed the following clinical endpoints: ICU admission, respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation, inpatient mortality, and non-fatal discharge from the hospital. Mechanical ventilation was assessed as an endpoint only among those who were not intubated on the index date and who did not have a code status indicating “do not intubate.” The ascertainment of drug utilization and clinical outcomes both started on the index date and continued until the earliest of death, discharged from the hospital, or end of the study (24 May 2020).

Patient Characteristics

We assessed patient demographics (age, sex, and race), body mass index, smoking, oxygen therapy, and vital signs on admission. We also assessed baseline co-morbidities using diagnosis and procedure codes and prior drug exposure using records from the electronic ordering system, medication reconciliation and dispensing data available in the EHR data in the 365 days prior and including the cohort entry date. Co-morbidities assessed included asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary tuberculosis, cystic fibrosis, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, myocardial infarction, stroke, peripheral vascular diseases, heart failure, venous thromboembolism, atrial fibrillation, malignancy, viral hepatitis, human immunodeficiency virus infection, urinary tract infections, chronic liver disease, major bleeding events, connective tissue diseases, dementia, history of organ transplant. Baseline medication exposure evaluated included non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroids, statins, ACEIs, angiotensin receptor blockers, and other anti-hypertensives, proton pump inhibitors, H2RAs, anticoagulants, anti-platelet agents, anti-diabetic agents, anti-asthmatic agents, anti-depressants, anticonvulsants, chemotherapy, and biologics. Detailed definitions for each co-morbidity and generic names for each medication class are listed in Appendix 1 of the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM).

Statistical Analysis

We assessed trends in the proportion of patients receiving the drugs of interest by COVID-19 severity using the Cochran-Armitage test [50]. For weekly drug utilization time trends, we used a generalized linear model with generalized estimating equations and robust standard errors to account for within-person correlation over time [51]. To assess associations between patient characteristics and pharmacological treatment for COVID-19, we built a model including basic demographic factors and factors selected by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression [52]. The selected predictors were entered into logistic regression models as explanatory (independent) variables. The dependent variable was the receipt of at least one COVID-19-specific medication (not including agents used for supportive care). We excluded remdesivir from the dependent variable in the primary analysis because it was mostly an investigational drug in the study period, and use of it depended on trial eligibility and drug availability. We conducted a sensitivity analysis including remdesivir. All analyses were performed using SAS statistical software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Hospitalization Outcomes by Disease Severity

We identified 13,445 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 and excluded 10,489 non-hospitalized patients, 14 pediatric patients, 61 pregnant women, and 60 receiving hospice or comfort care on admission, yielding a final study cohort of 2821 patients (mean age 62.7; 45% female). Inpatient mortality increased by severity from 5% for level 1 to 36% for level 4 (Table 1). Inpatient mortality was 23% in patients in level 5 (those intubated, on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to the ICU on admission), but a larger proportion of patients in level 5 remained hospitalized without an ultimate hospitalization outcome (death or discharge alive) as compared with level 4 (15 vs 8%, p = 0.017). We observed a similar trend for mechanical ventilation and transfer to the ICU.

Table 1.

Hospitalization outcomes by disease severity

| Hospitalization outcomes | Severity level on admissiona | Overall, N (%) N = 2821 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, N (%) Total N = 1000 | 2, N (%) Total N = 602 |

3, N (%) Total N = 236 |

4, N (%) Total N = 152 |

5, N (%) Total N = 831 |

p for trend | ||

| Inpatient mortality | 54 (5) | 60 (10) | 36 (15) | 55 (36) | 187 (23) | < 0.0001 | 392 (14) |

| Discharge aliveb | 875 (88) | 513 (85) | 177 (75) | 85 (56) | 516 (62) | < 0.0001 | 2166 (77) |

| Remain in the hospital | 71 (7) | 29 (5) | 23 (10) | 12 (8) | 128 (15) | < 0.0001 | 263 (8) |

| Mechanical ventilationc | 62 (7) | 51 (10) | 52 (26) | 43 (39) | 109 (25) | < 0.0001 | 317 (14) |

| Transfer to ICU | 168 (17) | 107 (18) | 74 (31) | 66 (43) | – | < 0.0001 | 415 (21) |

ICU intensive care unit

aWe defined COVID-19 disease severity as follows: severity level 1, hospitalized but not requiring supplemental oxygen; level 2, hospitalized and requiring supplemental oxygen ≤ 2 L/min; severity level 3, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy 3–4 L/min; level 4, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy ≥ 5 L/min or receiving nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, non-rebreather, or noninvasive mechanical ventilation; level 5, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to an ICU

bNon-fatal discharge from the hospital

cAssessed among patients who did not receive mechanical ventilation on the index date and who did not have a code status indicating “do not intubate”

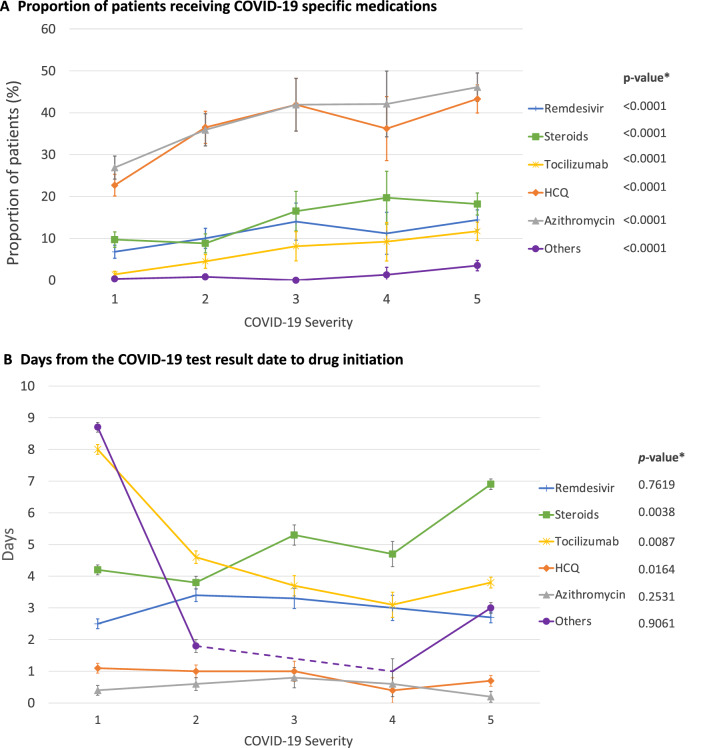

Prescribing of COVID-19-Specific Medications by Disease Severity

Patients in lower severity levels were less likely to receive COVID-19-specific medications than those in higher severity levels. Use increased from 7% in level 1 to 14% in level 5 for remdesivir, from 23% to 43% for hydroxychloroquine, and from 10% to 18% for systemic steroids (Fig. 1a). The mean time from when the positive test result became available to drug initiation significantly decreased across levels from 8.0 days in level 1 to 3.8 days in level 5 (p for trend = 0.0087) for tocilizumab. A similar trend was found for hydroxychloroquine (1.1 days for level 1 and 0.7 days for level 5; p for trend = 0.0164). In contrast, systemic steroids tended to be initiated later for patients with higher severity (p for trend = 0.0038, Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Pharmacological treatment pattern of patients hospitalized with COVID-19 by disease severity. We defined COVID-19 disease severity as follows: severity level 1, hospitalized but not requiring supplemental oxygen; level 2, hospitalized and requiring supplemental oxygen ≤ 2 L/min; severity level 3, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy 3–4 L/min; level 4, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy ≥ 5 L/min or receiving nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, non-rebreather, or noninvasive mechanical ventilation; level 5, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to an intensive care unit. HCQ hydroxychloroquine, others sarilumab, siltuximab, darunavir/cobicistat, interferon-beta, nitric oxide, favipiravir, canakinumab, ravulizumab, ibrutinib, anakinra, rilonacept, and umifenovir. *p-value for linear trend by COVID-19 severity

Pharmacological Treatment for COVID-19 Supportive Care by Disease Severity

We observed increasing use by severity for most medications relevant for COVID-19 supportive care (Table 2). For example, use of therapeutic parenteral anticoagulants increased from 8% in patients of severity level 1 to 35% in those of level 5 (p for trend <0.0001). Use of prophylactic anticoagulants was high (62–71%) for patients of all severity levels.

Table 2.

Use of supportive care medications in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 by disease severity

| Medication class | Severity level on admissiona | p for trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1, N (%) Total N = 1000 |

2, N (%) Total N = 602 |

3, N (%) Total N = 236 |

4, N (%) Total N = 152 |

5, N (%) Total N = 831 |

||

| Statins | 568 (57) | 386 (64) | 182 (77) | 92 (61) | 505 (61) | 0.1375 |

| ACEI/ARB | 247 (25) | 138 (23) | 61 (26) | 34 (22) | 149 (18) | 0.0008 |

| Prophylactic anticoagulants | 712 (71) | 459 (76) | 168 (71) | 94 (62) | 536 (65) | < 0.0001 |

| Therapeutic parenteral anticoagulants | 84 (8) | 63 (11) | 45 (19) | 33 (22) | 290 (35) | < 0.0001 |

| Therapeutic oral anticoagulants | 121 (12) | 86 (14) | 40 (17) | 22 (15) | 138 (17) | 0.0072 |

| Antibiotics | 522 (52) | 364 (61) | 180 (76) | 124 (82) | 684 (82) | < 0.0001 |

| Anti-influenza agentsb | 4 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 13 (2) | 0.0009 |

| Other non-HIV anti-viral therapiesc | 16 (2) | 14 (2) | 9 (4) | 5 (3) | 28 (3) | 0.0120 |

| Inhalers | 254 (25) | 226 (38) | 108 (46) | 62 (41) | 319 (38) | < 0.0001 |

| Nebulizers | 210 (21) | 216 (36) | 102 (43) | 60 (40) | 306 (37) | < 0.0001 |

| IV PPI | 70 (7) | 45 (8) | 34 (14) | 26 (17) | 236 (28) | < 0.0001 |

| Oral PPI | 301 (30) | 192 (32) | 97 (41) | 53 (35) | 335 (40) | < 0.0001 |

| IV H2RA | 44 (4) | 36 (6) | 23 (10) | 18 (12) | 207 (25) | < 0.0001 |

| Oral H2RA | 99 (10) | 61 (10) | 38 (16) | 25 (16) | 247 (30) | < 0.0001 |

ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin II receptor blockers, H2RA H2-receptor antagonists, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, IV intravenous, PPI proton pump inhibitors

aWe defined COVID-19 disease severity as follows: severity level 1, hospitalized but not requiring supplemental oxygen; level 2, hospitalized and requiring supplemental oxygen ≤ 2 L/min; severity level 3, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy 3–4 L/min; level 4, hospitalized and requiring oxygen therapy ≥ 5 L/min or receiving nasal high-flow oxygen therapy, non-rebreather, or noninvasive mechanical ventilation; level 5, receiving invasive mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to an intensive care unit

bOseltamivir or amantadine

cAcyclovir, ganciclovir, valacyclovir, valganciclovir

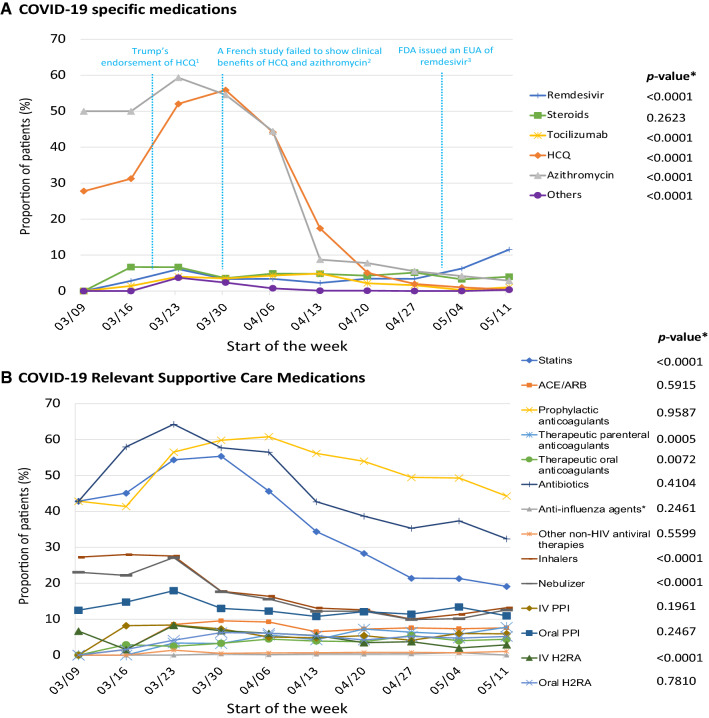

Weekly Time Trend

There was a dramatic increase in prescribing of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in March 2020 followed by a precipitous decline from April 2020. Use of tocilizumab and systemic steroids fluctuated across the study period. Remdesivir use increased beginning in May 2020 (p < 0.0001, Fig. 2a). Among medications relevant for COVID-19 supportive care, we observed a significant decrease in the use of statins, intravenous H2RAs, inhalers, and nebulizers. Use of therapeutic parenteral anticoagulants increased significantly over time (p = 0.0005, Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Weekly time trend of pharmacological treatment for patients hospitalized for COVID-19. ACEi angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, ARB angiotensin II receptor blockers, FDA US Food and Drug Administration, H2RA H2-receptor antagonists, HCQ hydroxychloroquine, HIV human immunodeficiency virus, EUA emergency use authorization, IV intravenous, PPI proton pump inhibitors. Others: sarilumab, siltuximab, darunavir/cobicistat, interferon beta, nitric oxide, favipiravir, canakinumab, ravulizumab, ibrutinib, anakinra, rilonacept, and umifenovir. *p-value for linear time trend. The first week was excluded because of an insufficient number of patients (n = 2) and the last week was excluded because of an incomplete observation period (<1 week). 1On 19 March, 2020, President Trump endorsed the use of hydroxychloroquine to treat COVID-19 on the television. 2On 30 March, 2020, a French study found no evidence of effective antiviral activities or clinical benefits of the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin for the treatment of hospitalized patients with severe COVID-19 [63], findings that were supported by several subsequent studies [64]. 3On 1 May, 2020, the US FDA issued an EUA of remdesivir for the treatment of hospitalized patients with COVID-19

Predictors of COVID-19 Prescribing

After considering 105 variables (see the list of all variables evaluated in Appendix 2 of the ESM), LASSO selected 26 variables (Table 3). The multivariable adjusted odds ratio (aOR) was 1.50 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.16–1.92) comparing use of COVID-19-specific medications in level 2 patients to level 1 patients and 3.53 (95% CI 2.73–4.57) comparing level 5 to level 1. Other significant positive predictors included having a fever, low oxygen saturation (≤ 93%), history of organ transplantation, prior use of systemic steroids, elevated C-reactive protein, COVID-19 test performed in an inpatient (vs outpatient) setting, and calendar time. The aOR was 0.11 (95% CI 0.09–0.14) comparing use of COVID-19 medications after vs before (including) 15 April, the median time among all cohort entry dates of our study population.

Table 3.

Characteristics of patients hospitalized for COVID-19, stratified by whether they received medications to treat COVID-19

| Patient characteristics | Not receiving COVID-19 medications, N = 1147 | Receiving COVID-19 medications, N = 1674 | aOR (95% CI)a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||

| Age, years | |||

| 15–49 | 283 (25) | 371 (22) | Ref |

| 50–64 | 314 (27) | 509 (30) | 1.25 (0.96–1.62) |

| 65–74 | 201 (18) | 341 (20) | 1.30 (0.95–1.76) |

| 75–84 | 195 (17) | 276 (16) | 1.28 (0.92–1.79) |

| 85 + | 154 (13) | 177 (11) | 1.37 (0.93–2.01) |

| Race | |||

| White | 591 (52) | 829 (50) | Ref |

| Black | 215 (19) | 285 (17) | 0.99 (0.76–1.28) |

| Asian | 44 (4) | 62 (4) | 0.93 (0.58–1.49) |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Island | 2 (0) | 5 (0) | 1.48 (0.22–9.85) |

| Other | 295 (26) | 493 (29) | 1.10 (0.87–1.39) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 549 (48) | 719 (43) | Ref |

| Male | 598 (52) | 955 (57) | 1.02 (0.84–1.23) |

| Severity | |||

| 1 | 597 (21) | 403 (14) | Ref |

| 2 | 257 (9) | 345 (12) | 1.50 (1.16–1.92)c |

| 3 | 87 (3) | 149 (5) | 1.50 (1.05–2.13)c |

| 4 | 69 (2) | 83 (3) | 1.70 (1.10–2.62)c |

| 5 | 267 (9) | 564 (20) | 3.53 (2.73–4.57)c |

| Cohort entry date | |||

| Before 15/4/2020d | 274 (22) | 298 (19) | Ref |

| After 15/4/2020d | 1003 (79) | 1246 (81) | 0.11 (0.09– 0.14)c |

| COVID test | |||

| COVID test before hospitalization | 255 (22) | 317 (19) | Ref |

| COVID test during hospitalization | 892 (78) | 1357 (81) | 1.31 (1.03–1.65)c |

| Code status on index date | |||

| Full code | 756 (66) | 1181 (71) | Ref |

| DNI only | 10 (1) | 21 (1) | 1.54 (0.64–3.68) |

| DNR ± DNI | 201 (18) | 197 (12) | 0.79 (0.58–1.07) |

| Unknown | 180 (16) | 275 (16) | 1.63 (1.25–2.13) |

| Vital signs groups on index date, N (%) | |||

| Heart rate, bpm | |||

| ≤ 100 | 982 (86) | 1411 (84) | Refb |

| > 100 | 165 (14) | 263 (16) | 1.13 (0.87–1.46) |

| Oxygen saturation, % | |||

| > 93 | 1024 (89) | 1359 (81) | Refb |

| ≤ 93 | 123 (11) | 315 (19) | 1.46 (1.13–1.88)c |

| Temperature, °C, N (%) | |||

| < 37.5 | 642 (56) | 565 (34) | Ref |

| 37.5–38.0 | 207 (18) | 385 (23) | 1.44 (1.13–1.83)c |

| 38.1–39.0 | 182 (16) | 432 (26) | 1.59 (1.24–2.03)c |

| > 39.0 | 113 (10) | 285 (17) | 1.63 (1.23–2.18)c |

| Missing | 3 (0) | 7 (0) | 0.82 (0.16–4.19) |

| Baseline co-morbidities | |||

| Asthma | 130 (11) | 209 (12) | 1.32 (0.98–1.77) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 368 (29) | 482 (31) | 1.10 (0.87–1.40) |

| Hypertension | 618 (48) | 768 (50) | 1.17 (0.93–1.47) |

| Malignancy | 130 (11) | 241 (14) | 1.20 (0.90–1.61) |

| Organ transplant | 9 (1) | 42 (3) | 4.19 (1.90–9.24)c |

| Medication use in 1 year prior to the index date | |||

| Systemic steroids | 164 (19) | 287 (24) | 1.53 (1.15–2.03)c |

| Antidepressant | 285 (33) | 302 (25) | 0.78 (0.60–1.00) |

| NSAIDs | 375 (43) | 460 (38) | 0.81 (0.64–1.02) |

| Baseline laboratory test classification | |||

| Albumin, g/dL | |||

| ≥ 3.3 | 221 (19) | 281 (17) | Ref |

| <3.3 | 823 (72) | 1207 (72) | 0.90 (0.69–1.16) |

| Missing | 103 (9) | 186 (11) | 1.23 (0.87–1.75) |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | |||

| 0–8 | 133 (12) | 82 (5) | Ref |

| 8–100 | 508 (44) | 727 (43) | 1.39 (0.96–2.01) |

| > 100 | 298 (26) | 625 (37) | 1.96 (1.32–2.91)c |

| Missing | 208 (18) | 240 (14) | 1.14 (0.71–1.83) |

| d-Dimer, ng/mL | |||

| < 500 | 224 (20) | 357 (21) | Ref |

| 500–100 | 223 (19) | 268 (16) | 0.85 (0.62–1.15) |

| > 1000 | 321 (28) | 497 (30) | 1.18 (0.89–1.56) |

| Missing | 379 (33) | 552 (33) | 1.18 (0.88–1.60) |

| Glucose level, mg/dL | |||

| ≤ 180 | 962 (84) | 1352 (81) | Refb |

| > 180 | 185 (16) | 322 (19) | 1.22 (0.94–1.60) |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | |||

| ≥ 12 | 737 (64) | 1206 (32) | Refb |

| <12 | 410 (36) | 468 (28) | 0.84 (0.68–1.04) |

| Lymphocyte count, K/uL | |||

| > 0.8 | 762 (66) | 965 (58) | Ref |

| <0.8 | 342 (30) | 619 (37) | 1.06 (0.86–1.30) |

| Missing | 43 (4) | 90 (5) | 1.57 (0.93–2.66) |

| Procalcitonin, ng/mL | |||

| <0.08 | 257 (22) | 313 (19) | Ref |

| > 0.08 | 614 (54) | 1042 (62) | 1.27 (0.99–1.63) |

| Missing | 276 (24) | 319 (19) | 1.01 (0.71–1.45) |

ALP alkaline phosphatase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, aOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval, DNI do not intubate, DNR do not resuscitate, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PT-INR prothrombin time and internal normalized ratio, Ref reference, WBC white blood cell

aaOR adjusted for all the 26 variables selected by least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) regression from 105 candidate predictors (see the full list in Appendix 2 of the ESM)

bThe reference group was merged with the missing category because of small cell/non-convergence

cSignificant associations

dMedian calendar date among all the cohort entry dates of patients included in the study

Sensitivity Analysis

Including remdesivir in a sensitivity analysis produced similar estimates as observed in the primary analysis. The aOR was 3.75 (95% CI 2.86–4.91) comparing use of COVID-19-specific medications in level 5 to level 1. The aOR was 0.16 (95% CI 0.13–0.19) comparing prescribing of COVID-19 medications after vs before (including) 15 April (Appendix 3 of the ESM). In contrast, the aOR comparing prescribing of remdesivir alone after vs before (including) 15 April was 4.15 (95% CI 3.01–5.74, data not shown).

Discussion

In this study of more than 2800 individuals hospitalized with positive SARS-CoV-2 tests in Massachusetts, we found that the use of pharmacological treatments for COVID-19 is largely driven by disease severity. Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 requiring oxygen or ICU admission were 1.5- to 3.5-fold more likely to receive drug therapies than those not needing oxygen. Having a fever, low oxygen saturation, history of organ transplantation, prior use of systemic steroids, and elevated C-reactive protein were also predictive of receiving COVID-19-specific medications. We also found that a severity scale determined by oxygen requirement and ICU designation is highly predictive of COVID-19-specific treatment administration as well as mortality and the risk of respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation.

These findings have important implications for the conduct and interpretation of non-randomized studies in COVID-19, which may be subject to strong confounding. It has been noted that COVID-19 can cause rapid respiratory deterioration with median days from onset of dyspnea to acute respiratory distress syndrome requiring intubation of around 2–3 days [53, 54]. Studies that do not carefully account for COVID-19 severity, including oxygen requirement, which can change quickly over time, are likely to be biased. We also found that the use of pharmacological treatments has dropped by almost 90% for most COVID-19 relevant medications, except for remdesivir and therapeutic anticoagulants, which have been increasing in use over time. Understanding of treatment patterns is important to put into context the results of both non-randomized studies and RCTs because the clinical questions that might be relevant may be rapidly changing as the standard of care evolves.

We observed a significant increasing trend in inpatient mortality by the modified severity scale with the exception of progression from severity level 4 (hospitalized and requiring supplemental oxygen of ≥ 5/min) to level 5 (receiving mechanical ventilation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or admitted to an ICU). It is possible that some patients in level 4 were critically ill but were not admitted to the ICU or did not receive invasive procedures because of medical futility [55]. Indeed, we observed a higher proportion of patients with a do-not-resuscitate code status in level 4 than in level 5 (31% vs 14%). It is also possible that some of these critically ill patients remained outside of the ICU because of capacity constraints during the pandemic [55, 56], which could lead to higher risks of adverse outcomes. In addition, patients in level 5 were almost two-fold more likely than those in level 4 to remain hospitalized without an ultimate outcome (death or discharged alive) at the available data. An ICU stay can prolong hospitalization [57, 58], and those with longer lengths of stay have been shown to have higher mortality [59], which has not yet fully unfolded in our current data.

We observed a rapid rise followed by a rapid decline in the use of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin. These findings are consistent with a recent report based on US outpatient pharmacy data that showed a dramatic increase (+214%) in dispensing of hydroxychloroquine during the week of 15–21 March, 2020, compared with that in 2019, followed by a subsequent decline [60]. In our multivariable analysis, use of COVID-19-specific medications in the inpatient setting dropped by almost 90% after mid-April, 2020, compared with the earlier phase of the pandemic. The administration of other supportive medications also declined over the study period. Evidence to inform pharmacological treatment for COVID-19 was sparse in the early phase of the pandemic, whereas more selective prescribing is occurring as evidence about the effectiveness or ineffectiveness of various treatments has also emerged. The only two medications that increased in use over the study period were remdesivir and therapeutic anticoagulants. An RCT comparing remdesivir with placebo showed significant improvement in the time to recovery [8], which led the US Food and Drug Administration to issue an Emergency Use Authorization for the treatment of COVID-19 [61]. COVID-19 has been linked with a state of hypercoagulability [62] and clinical guidelines have recommended pharmacologic prophylaxis for venous thromboembolism in all patients hospitalized for COVID-19 [25, 26]. Proactive surveillance for venous thromboembolism and some empirical use for high-risk patients may explain the increasing trend in the use of therapeutic anticoagulants in our cohort [25]. A preliminary report from the Randomized Evaluation of COVID-19 Therapy (RECOVERY) trial suggests that the use of dexamethasone could reduce mortality in patients hospitalized with COVID-19 receiving mechanical ventilation and supplemental oxygen, but not in those not receiving oxygen therapy [9]. In our study cohort, we observed an almost two-fold increase in the prescribing of systemic steroids in patients hospitalized for COVID-19 requiring oxygen therapy ≥ 5 L/min, intubation, or ICU admission, compared with those not requiring oxygen. The RCT findings [9] were released after our study period, thus we have not observed their impact on prescribing trends. Within our care delivery network, there were no unified institutional guidelines or clinical pathways. Therefore, the observed time trends likely reflect the responses of each care facility to the evolving research findings and regulatory decisions mentioned above (Fig. 2).

Our study has several limitations. First, we used EHR data in the 365 days before the index date to determine co-morbidities and prior drug exposure. Some patients may not regularly receive care in our EHR system, which may result in under-estimation of these covariates. We also used medical conditions recorded on admission to reduce such misclassification, but this also relies on the recording of codes for important chronic conditions during the index hospitalization. Reassuringly, we observed comparable prevalences of diabetes (30%) and hypertension (49%) when compared to what was reported in a recent RCT conducted in hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (diabetes, 29% and hypertension, 50%) [8]. Second, missing data are common in EHR-based studies. Given the severity of the study population, the magnitude of missingness in this cohort was relatively small. Data were missing for admission vital signs for <0.5% patients. Commonly ordered admission laboratory tests, such as blood cell counts and general chemistry tests, were available for > 95%, and inflammatory makers available for > 80% of our study cohort. Markers for coagulation abnormalities were notably less available (58–67%, Appendix 4 of the ESM). We used a missing indicator approach in our prediction models and found that missingness was not associated with COVID-19 prescribing. Third, remdesivir was primarily an investigational drug during our study period, and its use was limited by trial eligibility and drug availability. Therefore, our primary analysis excluded remdesivir, but a sensitivity analysis including remdesivir showed largely consistent results. Last, our findings are based on a Massachusetts-based healthcare system and the generalizability of our findings to other systems was not evaluated.

Conclusions

Use of medications for COVID-19 in the inpatient setting is highly correlated with disease severity. A simple COVID-19 severity scale using admission oxygen requirements and ICU designation correlates well with inpatient mortality and is highly predictive of the administration of COVID-19-specific medications. Compared with the early phase of the pandemic, the use of most medications has significantly declined, except for remdesivir and therapeutic anticoagulants, which have been increasing. Careful consideration of determinants of COVID-19 drug use, including oxygen requirement, vital signs, inflammatory markers, and co-morbidities, is necessary for successfully conducting non-randomized studies evaluating outcomes of COVID-19 treatments.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the insights provided by Dr. Francisco Marty, Division of Infectious Disease, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, and Christopher Herrick, Mass General Brigham Research Information Science and Computing.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Schneeweiss is participating in investigator-initiated grants to the Brigham and Women’s Hospital from Bayer, Vertex, and Boehringer Ingelheim unrelated to the topic of this study. He is a consultant to Aetion Inc., a software manufacturer of which he owns equity. His interests were declared, reviewed, and approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Mass General Brigham System in accordance with their institutional compliance policies. Dr. Gagne has received salary support from grants from Eli Lilly and Company and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation to the Brigham and Women's Hospital and was a consultant to Optum, Inc., all for unrelated work. Other authors have no conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethics approval

The Mass General Brigham (MGB) institutional review board (IRB) approved the study protocol (#2020P001022).

Consent to participate

Not applicable. The MGB IRB approved the study to be exempt from individual consent as this is a secondary use of routinely collected database.

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The MGB IRB approved the study to be exempt from individual consent as this is a secondary use of routinely collected database.

Availability of data and materials

The patient-level data that the study was based on are not available due to patient privacy, in compliance of our approved IRB.

Code availability

The detailed definitions of our study variables are available in the Supplemental information (Appendix 1).

References

- 1.CDC et al. (2020) Severe outcomes among patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)—United States, February 12–March 16, 2020. Morbidity Mortality Wkly Rep. 2020;69:343–346. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richardson S, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York city area. JAMA. 2020;323(20):2052–2059. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Hasell J. Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Published online at OurWorldInData.org; 2020. https://www.ourworldindata.org/coronavirus. Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 4.Wang X, et al. Comorbid chronic diseases and acute organ injuries are strongly correlated with disease severity and mortality among COVID-19 patients: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Research. 2020;2020:1–17. doi: 10.34133/2020/2402961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adams ML, Katz DL, Grandpre J. Population-based estimates of chronic conditions affecting risk for complications from coronavirus disease, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:1831–1833. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.200679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bajwah S, et al. Managing the supportive care needs of those affected by COVID-19. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:2000815. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00815-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders JM, Monogue ML, Jodlowski TZ, Cutrell JB. Pharmacologic treatments for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) JAMA. 2020;323(18):1824–1836. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19 — preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:992–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horby P, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Geleris J, et al. Observational study of hydroxychloroquine in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2411–2418. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2012410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenberg ES, et al. Association of treatment with hydroxychloroquine or azithromycin with in-hospital mortality in patients with COVID-19 in New York state. JAMA JAMA. 2020;323(24):2493–2502. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andreani J, et al. In vitro testing of combined hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin on SARS-CoV-2 shows synergistic effect. Microb Pathog. 2020;145:104228. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2020.104228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beck BR, Shin B, Choi Y, Park S, Kang K. Predicting commercially available antiviral drugs that may act on the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) through a drug–target interaction deep learning model. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2020;18:784–790. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mantlo E, Bukreyeva N, Maruyama J, Paessler S, Huang C. Antiviral activities of type I interferons to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Antiviral Res. 2020;179:104811. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez MA. Compounds with therapeutic potential against novel respiratory 2019 coronavirus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2020;64:e00399-20. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00399-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alattar R, et al. Tocilizumab for the treatment of severe coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):2042–2049. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alzghari SK, Acuña VS. Supportive treatment with tocilizumab for COVID-19: a systematic review. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104380. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang S, Li L, Shen A, Chen Y, Qi Z. Rational Use of tocilizumab in the treatment of novel coronavirus pneumonia. Clin Drug Investig. 2020;40:511–518. doi: 10.1007/s40261-020-00917-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brojakowska A, Narula J, Shimony R, Bander J. Clinical implications of SARS-Cov2 interaction with renin angiotensin system. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(24):3085–3095. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Javanmard SH, Heshmat-Ghahdarijani K, Vaseghi G. Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors) and angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) Use in COVID-19 prevention or treatment: a paradox. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2020:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Kai H, Kai M. Interactions of coronaviruses with ACE2, angiotensin II, and RAS inhibitors—lessons from available evidence and insights into COVID-19. Hypertension Res. 2020;43:648–654. doi: 10.1038/s41440-020-0455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reiner Ž, et al. Statins and the COVID-19 main protease: in silico evidence on direct interaction. Arch Med Sci. 2020;16:490–496. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2020.94655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muralidharan N, Sakthivel R, Velmurugan D, Gromiha MM. Computational studies of drug repurposing and synergism of lopinavir, oseltamivir and ritonavir binding with SARS-CoV-2 protease against COVID-19. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2020:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Hendaus MA, Jomha FA. Covid-19 induced superimposed bacterial infection. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2020:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Barnes GD, et al. Thromboembolism and anticoagulant therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic: interim clinical guidance from the anticoagulation forum. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50:72–81. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02138-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kollias A, et al. Thromboembolic risk and anticoagulant therapy in COVID-19 patients: emerging evidence and call for action. Br J Haematol. 2020;189:846–847. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borrell B. New York clinical trial quietly tests heartburn remedy against coronavirus. Sci Mag. 2020.

- 28.Lowe D. Omeprazole as an additive for coronavirus therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2020.

- 29.Freedberg DE, et al. Famotidine use is associated with improved clinical outcomes in hospitalized COVID-19 patients: a propensity score matched retrospective cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(3):1129–1131. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beigel JH, et al. Remdesivir for the treatment of Covid-19—preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:992–994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cao B, et al. A trial of lopinavir-ritonavir in adults hospitalized with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1787–1799. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, et al. Remdesivir in adults with severe COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1569–1578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31022-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nalichowski R, Keogh D, Chueh HC, Murphy SN. Calculating the benefits of a research patient data repository. AMIA. 2006:1044. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Mass General Brigham (MGB). Hospitals and affiliates. https://www.partners.org/Services/Hospitals-And-Affiliates.aspx. Accessed 16 June 2020.

- 35.Vitacca M, Nava S, Santus P, Harari S. Early consensus management for non-ICU ARF SARS-CoV-2 emergency in Italy: from ward to trenches. Eur Respir J. 2020;55(5):2000632. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00632-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hyzy R. Heated and humidified high-flow nasal oxygen in adults: practical considerations and potential applications. UpToDate. 2020.

- 37.Grein J, et al. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2327–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2007016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu C-C, Chen M-Y, Chang Y-L. Potential therapeutic agents against COVID-19. J Chin Med Assoc. 2020;83(6):534–536. doi: 10.1097/JCMA.0000000000000318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gritti G, et al. Use of siltuximab in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia requiring ventilatory support. medRxiv. 2020 doi: 10.1101/2020.04.01.20048561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ignarro LJ. Inhaled NO and COVID-19. Br J Pharmacol. 2020;177(16):3848–3849. doi: 10.1111/bph.15085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zamanian RT, et al. Outpatient inhaled nitric oxide in a patient with vasoreactive IPAH and COVID-19 infection. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;202(1):130–132. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-0937LE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pilkington V, Pepperell T, Hill A. A review of the safety of favipiravir—a potential treatment in the COVID-19 pandemic? J Virus Erad. 2020;6:45–51. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30016-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Monteagudo LA, Boothby A, Gertner E. Continuous intravenous anakinra infusion to calm the cytokine storm in macrophage activation syndrome. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2020;2:276–282. doi: 10.1002/acr2.11135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ClinicalTrials.gov. Efficacy and safety study of IV ravulizumab in patients with COVID-19 severe pneumonia; 2020. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT04369469.

- 45.Treon SP, et al. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib may protect against pulmonary injury in COVID-19—infected patients. Blood. 2020;135:1912–1915. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franzetti M, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor antagonist anakinra in association with remdesivir in severe Coronavirus disease 2019: a case report. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;97:215–218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Regeneron. Regeneron announces important advances in novel COVID-19 antibody program; 2020. https://investor.regeneron.com/news-releases/news-release-details/regeneron-announces-important-advances-novel-covid-19-antibody.

- 48.Vankadari N. Arbidol: a potential antiviral drug for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 by blocking trimerization of the spike glycoprotein. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020;56(2):105998. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ari A. Practical strategies for a safe and effective delivery of aerosolized medications to patients with COVID-19. Respir Med. 2020;167:105987–105987. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.105987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou Z, Ku H-C, Huang Z, Xing G, Xing C. Differentiating the Cochran–Armitage trend test and Pearson’s χ2 test: location and dispersion. Ann Hum Genet. 2017;81:184–189. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liang KY, Zegar SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13–22. doi: 10.1093/biomet/73.1.13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roth GA, et al. The burden of cardiovascular diseases among US states, 1990–2016. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:375. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang D, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang X, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single-centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:475–481. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ballantyne A, Rogers WA, Entwistle V, Towns C. Revisiting the equity debate in COVID-19: ICU is no panacea. J Med Ethics. 2020;46(10):641–645. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moghadas SM, et al. Projecting hospital utilization during the COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117:9122–9126. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004064117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vasilevskis EE, et al. Reducing iatrogenic risks: ICU-acquired delirium and weakness–crossing the quality chasm. Chest. 2010;138:1224–1233. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Papazian L, Klompas M, Luyt C-E. Ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46:888–906. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05980-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Moitra VK, Guerra C, Linde-Zwirble WT, Wunsch H. Relationship between ICU length of stay and long-term mortality for elderly ICU survivors. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:655–662. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vaduganathan M, et al. Prescription fill patterns for commonly used drugs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. JAMA. 2020;323:2524. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.9184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.FDA. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: FDA issues emergency use authorization for potential COVID-19 treatment. 2020. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-fda-issues-emergency-use-authorization-potential-covid-19-treatment.

- 62.Panigada M, et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID-19 patients in intensive care unit: A report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Molina JM, et al. No evidence of rapid antiviral clearance or clinical benefit with the combination of hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin in patients with severe COVID-19 infection. Med Mal Infect. 2020;50:384. doi: 10.1016/j.medmal.2020.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fiolet T, et al. Effect of hydroxychloroquine with or without azithromycin on the mortality of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Microbiol Infect (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The patient-level data that the study was based on are not available due to patient privacy, in compliance of our approved IRB.