Abstract

Introduction

Individuals with obesity have higher rates of mental health disorders, both singly and in combination, than individuals of normal weight. Mental health disorders may negatively impact weight loss treatment outcomes; however, little is known about the mental health burden of individuals using weight loss programs. The current study identifies common mental health diagnostic profiles among participants of MOVE!—the Veterans Health Administration’s behavioral weight loss program.

Material and Methods

We used national VHA administrative data from fiscal year 2014 to identify veteran primary care patients who participated in at least one MOVE! session the previous year (n = 110,830). Using latent class analysis, we identified patient types (classes) characterized by the presence or absence of mental health diagnoses, both overall and stratified by age and gender.

Results

There were several patient types (classes), including psychologically healthy, predominantly depressed, depressed with co-occurring mental disorders, and co-occurring mental disorders with no predominant psychological condition. Additional patient types were found in men of different ages. The majority of patients had at least one psychiatric disorder, particularly younger patients.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve patients’ engagement in the MOVE! program may need to address barriers to care associated with mental health disorders or incorporate care for both obesity and mental health diagnoses in MOVE! A holistic approach may be particularly important for younger patients who have a higher comorbidity burden and longer care horizons. Future work may address if patient types found in the current study extend to non-VHA obesity treatment seekers.

INTRODUCTION

Individuals with obesity experience mental health issues at a higher rate than individuals of normal weight. Obesity is linked with depression,1–4 anxiety,2,5 severe mental illness (SMI),1 and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).4,6 The associations between obesity and mental health disorders are likely reciprocal.3 For instance, mental health issues could contribute to increased weight and put an individual at greater risk for obesity because of dysregulated stress systems,7 obesogenic behavioral symptoms (eg, physical inactivity),7 or obesogenic psychotropic medications.1 Conversely, stigma and discrimination experienced by individuals with obesity may contribute to the development of mental health disorders.8

Individuals with obesity also have higher rates of co-occurring mental health conditions; one study reported 23% of individuals with obesity met criteria for more than one mental health disorder compared to 11% of participants with normal weight.2 Co-occurring mental health disorders can lead to higher levels of impairment.9,10 Further, individuals with multiple conditions have an earlier onset and longer duration of mental health disorders and are more likely to experience adverse life events, including job stress, physical illness, lack of social support, and unemployment than individuals with one or no psychological diagnosis.10 Given that obesity is itself associated with a number of negative health experiences, including medical conditions and discrimination,11 patients with obesity and co-occurring mental health conditions may be particularly vulnerable to negative medical and psychosocial outcomes.

Understanding the mental health characteristics of patients with obesity is particularly salient for the Veterans Health Administration (VHA), which is one of the nation’s largest healthcare systems, serving more than 5 million unique outpatients every year. The veterans who use VHA care experience high rates of both obesity12 and mental health disorders,13 with markedly high rates of co-occurring mental health disorders (ie, multiple mental health diagnoses)14 and available evidence supports an association between obesity and mental health in veterans. Specifically, a study conducted among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans reported that diagnoses of PTSD, depression, and co-occurring mental health conditions were associated with negative weight outcomes over time, specifically if individuals were overweight or obese at the beginning of the study.15 There were also gender differences, with a stronger link between PTSD and obesity in men and a stronger link between depression and obesity in women.15

MOVE! is the VHA’s primary weight management program (www.move.va.gov), which was developed in-house for veterans following evidence-based guidelines from the National Institutes of Health.16 In some studies, veterans with mental health disorders have shown a blunted response to the MOVE! program, specifically veterans with depression,17 PTSD,18 and SMI.19 Moreover, veterans with mental health disorders report an increased number of barriers to weight loss,20,21 which may ultimately affect participation in weight loss programs.22 Despite high rates of co-occurring psychiatric disorders among VHA patients,14 there is little information about common subgroups of psychiatric disorders among MOVE! attendees. As healthcare systems move toward a precision medicine approach, in which an individual’s unique traits are integrated into treatment planning, knowledge of these subgroups can inform decisions on the necessity and utility of adapting MOVE! for individuals with co-occurring mental disorders, particularly as single-disorder interventions may not be sufficient to meet the needs of this population.10

The current study aimed to characterize patterns of mental health diagnoses among veterans participating in MOVE!. In addition, based on previous studies reporting that women with and without obesity are more likely to meet criteria for a mental disorder than their male counterparts2,23 and that younger individuals with obesity are more likely to experience depression or depressive symptoms than older individuals with obesity,1,24 a secondary goal was to explore how gender and age affected subgroup make-up and membership.

METHODS

Cohort and Program

We used national VHA electronic health record data to define a cohort of veteran VHA primary care patients in fiscal year 2014 (FY2014) who participated in at least one session of MOVE! in the 12 months before their initial primary care appointment in FY2014 (95,798 men and 15,032 women). Gender and age in the administrative data were defined based on previously developed algorithms.25 Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using an existing algorithm that provides a BMI for roughly 98% of VHA primary care patients in FY2014.12 Obesity care standards in VHA suggest veterans be screened for obesity annually, as measured by BMI, and offered a referral to weight management if they are deemed “at risk” (eg, BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 or BMI > 25 kg/m2 with an obesity-related health condition).16

Diagnoses

We used previously developed algorithms25 to identify the presence of the following six diagnostic groups based on ICD-9 codes: (1) depressive disorders, (2) substance use disorders (alcohol use disorder and drug use disorder), (3) bipolar disorder, (4) SMI (psychotic disorders and schizophrenia), (5) PTSD, and (6) anxiety disorders, each of which is included as a binary variable in the statistical models. We excluded eating disorders because of the relatively small number of patients with this condition (n = 407).

Statistical Analyses

We used LCA to identify profiles of mental health diagnoses among veterans in the cohort. LCA is a mixture model that assumes a latent categorical variable underlies certain profiles of a population and sorts data into exclusive latent classes.26 LCA uses the covariation among different observed and measurable variables to characterize the latent variable or the variable that is not observable or measurable. In this study, the observed variables were diagnoses while the latent variable was unique combinations or patterns of mental health diagnoses. LCA has advantages relative to simpler descriptive methods, notably allowing us to examine the entire set of interdependent relationships among different mental health disorders simultaneously.26 In this study, we used LCA to identify a parsimonious set of homogeneous classes that could not be simply characterized by the presence or absence of particular mental health diagnoses in a heterogeneous population.26 The output from the LCA includes class membership probabilities, item-response probabilities (ie, the probability an individual has a positive diagnosis given membership in the indicated class), and indicators of model fit.26 We used the PROC LCA program in SAS 9.4 for all LCA analyses.

We first tested for measurement invariance to determine whether underlying latent classes were the same for men and women. Because our tests indicated the classes were not the same for men and women, we ran separate models for each gender. We then ran a series of models specifying distinct classes and compared model fit using G2 (a likelihood-ratio chi-square statistic of absolute fit), and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), which are relative measures of fit26 (smaller values indicate better fit for both AIC and BIC; AIC favors more complex models whereas BIC favors more parsimonious models). We started by specifying two classes for each gender, separately, and increased the number of classes until model fit worsened (eg, resulted in larger AIC or BIC). We identified final models based on fit statistics and clinical interpretation of the classes. Once a final set of classes was selected, we modeled class membership as a function of age using multinomial logistic regression. This analysis provides odds ratios comparing odds of class membership for each class, as a function of age, when compared to a reference class. If inclusion of age as a covariate shifted item-response probabilities, such that classes were comprised differently (ie, different indicators crossed 0.5 threshold either way indicating that the diagnosis was no longer characteristic of the class), we removed age as a covariate and stratified LCA models by age group, as is recommended practice when using LCA.26

This work was approved by the relevant Institutional Review Board.

RESULTS

This cohort of MOVE! attendees was primarily men, average age was 59 years, and mean BMI was 35 (clinical obesity; Table I). A higher proportion of women than men had a mental health diagnosis within each category, with the exception of substance use disorders. Patients attended a median of two and a mode of one MOVE! visits.

Table I.

Demographics of Study Sample

| Variable | All (N = 110,830) | Men (N = 95,798) | Women (N = 15,032) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M ± SD) | 58.74 ± 11.48 | 60.11 ± 10.89 | 50.04 ± 11.34 |

| Body mass index (M ± SD) | 35.30 ± 6.89 | 35.37 ± 6.93 | 34.86 ± 6.64 |

| Mental health diagnosis, N (column %) | |||

| Depressive disorders | 40,844 (36.9%) | 33,089 (34.5%) | 7,755 (51.6%) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 27,080 (24.4%) | 22,633 (23.6%) | 4,447 (29.6%) |

| Anxiety disorders | 17,929 (16.2%) | 14,127 (14.7%) | 3,802 (25.3%) |

| Bipolar disorder | 6,243 (5.6%) | 4,617 (4.8%) | 1,626 (10.8%) |

| Severe mental illness | 4,783 (4.3%) | 3,998 (4.2%) | 785 (5.2%) |

| Substance use disorder | 14,423 (13.0%) | 13,037 (13.6%) | 1,386 (9.2%) |

Following measurement invariance testing for men and women, separately, we confirmed that class differences existed between men and women veterans (change in G2 = 1133.01, degrees of freedom [df] = 30, P < 0.001) and proceeded with gender-stratified analyses. In men, model fit consistently improved with the inclusion of each additional class in the model until a six-class model was reached. The six-class model did not converge; thus we determined a five-class model best fit our data (G2 = 164.31, AIC = 232.31, and BIC = 554.29). In women, model fit also improved with the inclusion of each additional class until a five-class model was reached, when BIC started increasing. As such, we determined a four-class model best fit the data (Table II).

Table II.

LCA of Psychiatric Diagnoses Model Results by Gender and Age

| Classes | G 2 | df | AIC | BIC |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young men (18–44 years) | ||||

| 2 | 615.31 | 50 | 641.31 | 734.13 |

| 3 | 265.14 | 43 | 305.14 | 447.94 |

| 4 | 156.09 | 36 | 210.09 | 402.88 |

| 5 | 81.49 | 29 | 149.49 | 392.25 |

| 6 | 37.95 | 22 | 119.95 | 412.69 |

| Middle-aged men (45–64 years) | ||||

| 2 | 1742.41 | 50 | 1768.41 | 1882.47 |

| 3 | 408.11 | 43 | 448.11 | 623.59 |

| 4 | 157.63 | 36 | 211.63 | 448.53 |

| 5 | 66.14 | 29 | 134.14 | 432.45 |

| 6 | 30.39 | 22 | 112.39 | 472.12 |

| Older men (65+ years) | ||||

| 2 | 592.80 | 50 | 618.80 | 730.13 |

| 3 | 236.46 | 43 | 276.46 | 447.74 |

| 4 | 128.08 | 36 | 182.08 | 413.32 |

| 5 | 124.58 | 29 | 124.58 | 415.76 |

| Women | ||||

| 2 | 1042.19 | 50 | 1068.19 | 1167.22 |

| 3 | 252.63 | 43 | 292.63 | 444.98 |

| 4 | 99.40 | 36 | 153.40 | 359.08 |

| 5 | 50.74 | 29 | 118.74 | 377.75 |

Note: Smaller G2, AIC, and BIC fit statistics indicate better model fit. Bolded results indicate best model fit.

After including age as a covariate in the model for men, item-response probabilities shifted heavily, indicating that age influenced class diagnostic patterns. Follow-up analyses comparing constrained and unconstrained models with three age groups confirmed that young (18–44 years old), middle-aged (45–64 years old), and older (65+ years old) men had distinct class profiles (change in G2 = 688.89, df = 60, P < 0.001), confirming measurement invariance, and separate LCA analyses were therefore performed for each age group. Optimal model fits were identified as follows: a five-class model for young men and older men and a six-class model for middle-aged men (Table II). In women, item-response probabilities were stable when the age covariate was added to the model, so we retained the four-class model containing women of all ages.

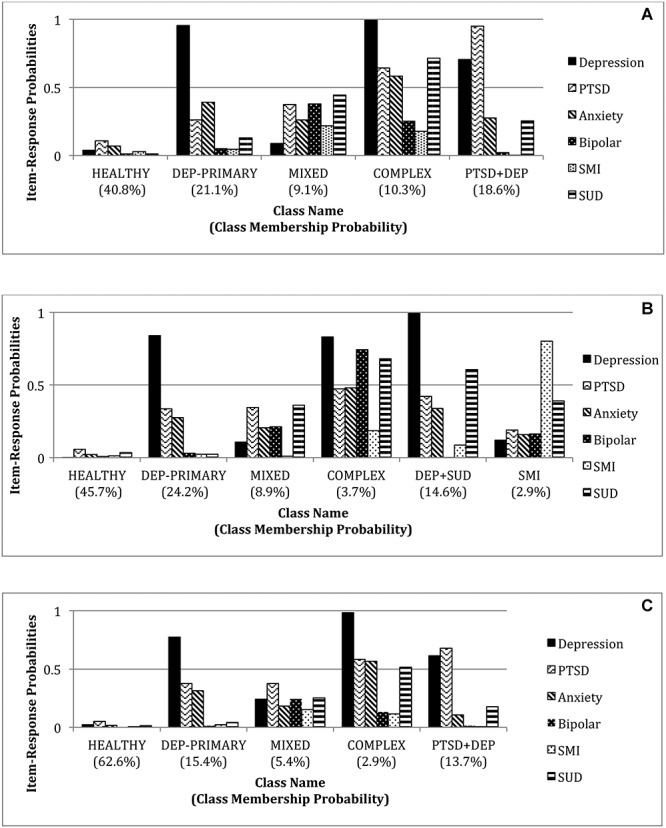

There were four classes characterized by similar patterns that emerged across age and gender groups (Fig. 1). The first was a psychologically healthy class (HEALTHY) that had a very low likelihood of mental health diagnoses. The HEALTHY class had the largest class membership probabilities for all male groups (from 40.8% in young men to 62.6% in older men) and the second largest class membership probabilities in women (40.0%). The next largest class was one characterized primarily by depressive disorders (DEP-PRIMARY), representing the second largest class membership probabilities for men of all age groups (between 15.4% and 24.2%) and the largest class membership probabilities for women (42.8%). The third was a class that was likely to have a mental health disorder, but was not characterized by any predominant disorder (MIXED), which constituted 5–10% of each gender and age group. However, among women, this class had an item-response probability for bipolar disorder slightly >0.5.

Figure 1.

Item-response probabilities of selected LCA models of psychiatric diagnoses: results by gender and age. (A) Young men (18–44 years), (B) middle-aged men (45–64 years), and (C) older men (65+ years).

The fourth class was more psychologically complex than the other classes, in which its members were more likely to have co-occurring mental health diagnoses (COMPLEX). For younger (10.3% of young men) and older (2.9% of older men) men, this class was characterized by depressive disorders with a high likelihood of a co-occurring disorder including PTSD, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. A similar pattern of diagnoses was found in women, although PTSD had a higher item-response probability than in the male groups, suggesting PTSD diagnoses as more characteristic of this clinically complex class in women. In middle-aged men, this class was characterized by depressive disorders, substance use disorders, and bipolar disorder.

There were additional classes by age among men. A class characterized by PTSD and depressive disorders (PTSD + DEP) was found in both younger (18.6%) and older men (13.7%) and a class characterized by depressive disorders and substance use among middle-aged men (DEP + SUD: 14.6%). Moreover, a small but distinct class in middle-aged men was characterized by SMI (SMI: 2.9%).

Results with age as a covariate in women suggest that latent class characterizations were consistent across women, regardless of age, and that the classes characterized by a greater likelihood of mental health diagnosis were more likely to have younger women than the HEALTHY class (LL −38008.78, change in 2*LL 229.39, df = 3, P < 0.001). Odds ratios for the DEP-PRIMARY class (0.975; CI: 0.971–0.979), the COMPLEX class (0.967; CI: 0.958–0.975), and the MIXED class (0.967; CI: 0.960–0.975) suggest that with each year increase in age, odds of membership in each latent class characterized by one or more mental disorders are lower than the odds of membership in the HEALTHY class.

DISCUSSION

We assessed patterns of mental health diagnoses among veterans with obesity who attended a VHA weight management program (MOVE!). Gender and age were associated with the number and patterns of mental health diagnoses, with men and women requiring separate models and men requiring different models across age groups. There were several classes characterized by similar patterns of mental health disorders in each of the gender and age groups. Specifically, all groups contained a HEALTHY class, a DEP-PRIMARY class, a COMPLEX class, and a MIXED class. Unique classes in men were PTSD + DEP, DEP + SUD, and SMI. Moreover, younger MOVE! attendees had a greater likelihood of at least one mental health diagnosis than older attendees of the same gender.

The results from the study indicate that in all groups, with the exception of older men, the majority of individuals presenting to MOVE! are likely to have at least one mental health diagnosis. The veteran population in VHA has a large mental health burden14 and some previous studies highlight blunted response to MOVE! in some populations with psychiatric diagnoses.17–19 However, it is notable that the HEALTHY class had the largest class membership probabilities in men (from 40.8% in young men to 62.6% in older men) and the second largest class membership probabilities in women (40.0%), which suggests a sizeable proportion of participants may not need adapted program content or additional referrals for mental health care.

Patients in classes characterized by co-occurring mental health diagnoses may present the greatest treatment challenge, as they tend to experience more enduring symptoms, more severe impairment, greater physical illness, a greater number of lifestyle challenges, and less support.10 Moreover severity of impairment in these areas increases as the number of mental health diagnoses increases.9 In this study, all age and gender groups had a COMPLEX class, while among men, there were also the PTSD + DEP and DEP + SUD classes. In young men specifically, class membership probabilities for the co-occurring psychiatric diagnoses class was high (over 25%). Individuals with co-occurring disorders are at risk for fragmented and inadequate treatment because of insufficient time or competing demands during treatment visits and overlapping or interfering symptomology from different conditions, including the clinical dominance of one or more disorders.27 As such, MOVE! providers should monitor how mental health diagnoses may be manifesting and interfering with treatment for clinically complex patients.

Guidance on how best to treat obesity in individuals with co-occurring mental health disorders is limited; no existing evidence base serves to guide treatment options for each combination of mental health disorders. By identifying common combinations of disorders relevant to MOVE! attendees, this analysis is a first step in addressing this gap and could allow for examination of the efficacy of different treatment approaches for clinically complex patients with common comorbidity profiles. Indeed, recent data suggest that improving mental health symptoms results in improved MOVE! engagement.28 Options could include a coordinated parallel treatment for mental health during MOVE! participation, in which veterans are simultaneously connected to the mental health clinic. The co-occurrence of substance use disorders with depression, PTSD, and anxiety in many of the clinically complex classes may warrant this type of approach, as individuals with a substance use disorder and another mental health condition respond more poorly to treatment and require coordinated care because of the chronicity of the condition.29 Administration of MOVE! by a provider who is familiar with mental and behavioral health interventions can offer other options, such as sequential treatment of disorders. For example, for an individual with PTSD and depression, a common patient profile as indicated by the results, it may be necessary to first start with behavioral activation for depression, move to an evidence-based treatment for PTSD to reduce emotional dysregulation that leads to emotional eating, and then introduce behavioral weight loss treatment components of MOVE!.

Treatment approaches for classes with a singular mental disorder are easier to identify. In the current study, the DEP-PRIMARY class represented the second largest class membership probabilities for men of all age groups (between 15.4% and 24.2%) and the largest class membership probabilities for women (42.8%). These results highlight larger trends from the literature showing that depression rates are higher in individuals with obesity than individuals of normal weight1–4 and are higher in women than men.15,30 Previous studies show that veterans with depression show blunted responses to treatment.17 Given the high-class membership probabilities in these classes, offering a MOVE! program option that includes treatment for depressive disorders such as behavioral activation or cognitive behavioral therapy may be warranted. Indeed, depression treatment has been integrated into obesity treatment previously with success in reducing both depressive symptoms and weight.31,32 This type of integrated care is appropriate in a primary care setting, which may improve participant access.32

The other class characterized by a singular diagnostic category was the SMI class in middle-aged men. Although the class membership probabilities were low (2.9%), SMI can cause substantial impairment. Previous studies have documented that individuals with SMI are overrepresented in MOVE!, demonstrating an interest in weight loss treatment in this population,33 although MOVE! attendees with SMI have limited weight loss (1% body weight across 12 months)33 and a greater number of barriers to healthy eating and physical activity.20 A previous attempt to adapt MOVE! for this population by administering it in a specialty mental health care setting and including an increased number of motivational techniques, visual learning aids, repetition of material, and content focused on interconnections between weight management and mental health disorders did not result in more weight loss compared to a basic diet and exercise education control condition,19 although other MOVE! adaptations for SMI have improved behavioral health factors.34 Authors of this trial suggest instead using a more holistic approach that emphasizes management of medical health and general wellness and includes programming and services to integrate a range of lifestyle issues that may interfere with treatment (eg, medication management, supervised living situations in which food is provided). Indeed, a more recent trial addressed treatment barriers associated with in-person attendance (eg, dislike for groups, transportation issues) by creating an online version of the adapted MOVE! intervention.35 Results of this study suggested higher acceptability and feasibility of the web-based intervention for veterans with SMI as well as improved weight loss outcomes compared to in-person groups. As such, use of MOVE! in VA-affiliated residential settings where both individual and environmental intervention can occur may be warranted.

Notably, younger MOVE! attendees, both men and women, had a greater likelihood of at least one mental health diagnosis than older attendees of the same gender. Others have documented the higher rates of mental health disorders in younger veterans in VHA, particularly among operation Iraqi freedom/operation enduring freedom veterans.30 As such, it may be beneficial to target combined weight loss and mental health treatment efforts toward younger MOVE! attendees.

Limitations of the current study include a reliance on diagnosis codes from the electronic health record, which lack the diagnostic rigor of structured clinical interviews. We included patients in the sample who had attended one or more MOVE! sessions to be inclusive of patients who may decide not to fully participate because of complications surrounding mental health. Thus, mental health profiles may be different among patients who participate in MOVE! long term. Additionally, we could not directly compare age and gender classes and class structures because LCA modeling demonstrated distinct differences among the latent classes. As such, comparisons made across age and gender groups are based on the ensemble of results rather than specific statistical tests. Furthermore, interpretation of LCA requires clinical and investigative judgment to arrive at final conclusions that are both statistically accurate and substantively meaningful. The final results thus depend on expert interpretation, which can be disputed, and we have therefore reported the modeling and interpretation with as much transparency as possible. Finally, there were more men than women in the sample, potentially leaving the women with less statistical power relative to the men and making it more difficult to optimally model more than four classes.

CONCLUSION

Most patients presenting to the MOVE! program from different age and gender groups are likely to have one or more psychiatric diagnoses, although older men were an exception. Our description of common and meaningful profiles of mental health diagnosis patterns among patients enrolled in MOVE! provides behavioral weight loss treatment developers and administrators critical information that can be used to adapt and tailor programs to address barriers to weight management. This may include referrals to mental health providers and sequential or integrated treatment of obesity and mental health disorders by trained providers. Future studies may seek to replicate these findings in veterans attending the other VHA programs or in other obesity treatment-seeking populations to understand if the current profiles are VHA-specific or obesity-specific patterns. Future work may also consider how patients with particular profiles, particularly co-occurring mental health disorders, respond to behavioral weight loss programs and may then test the efficacy of different approaches for individuals with diagnostically complex psychiatric presentations. Identifying, testing, and implementing more patient-centered weight management treatment options may increase treatment involvement and ultimately reduce the burden of obesity and obesity-related disease among patients.

Acknowledgment

Data were contributed by the Women’s Health Evaluation Initiative, which is funded by VA Women’s Health Services, Veterans Health Administration (VHA).

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the Department of Veterans Affairs or of the U.S. government.

FUNDING

Dr. Hayes is a postdoctoral fellow on a T32 training grant from the National Institutes of Health (T32 HL076134). Dr. Breland is a VA Health Services Research and Development Career Development Awardee at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (CDA 15-257) and an investigator with the Implementation Research Institute at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis, through an award from the National Institute of Mental Health (5R25MH08091607) and the Department of Veterans Affairs, Health Services Research & Development Service, Quality Enhancement Research Initiative.

References

- 1. Allison DB, Newcomer JW, Dunn AL, et al. : Obesity among those with mental disorders: a National Institute of Mental Health meeting report. Am J Prev Med 2009; 36(4): 341–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Baumeister H, Härter M: Mental disorders in patients with obesity in comparison with healthy probands. Int J Obes (Lond) 2007; 31(7): 1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Luppino FS, Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. : Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67(3): 220–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Scott KM, McGee MA, Wells JE, Browne MAO: Obesity and mental disorders in the adult general population. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64(1): 97–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gariepy G, Nitka D, Schmitz N: The association between obesity and anxiety disorders in the population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2010; 34(3): 407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Suliman S, Anthonissen L, Carr J, et al. : Posttraumatic stress disorder, overweight, and obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2016; 24(4): 271–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stunkard AJ, Faith MS, Allison KC: Depression and obesity. Biol Psychiatry 2003; 54(3): 330–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puhl RM, Heuer CA: Obesity stigma: important considerations for public health. Am J Public Health 2010; 100(6): 1019–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE: Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62(6): 617–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Newman DL, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA: Comorbid mental disorders: implications for treatment and sample selection. J Abnorm Psychol 1998; 107(2): 305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Finkelstein EA, Ruhm CJ, Kosa KM: Economic causes and consequences of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health 2005; 26: 239–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Breland JY, Phibbs CS, Hoggatt KJ, et al. : The obesity epidemic in the veterans health administration: prevalence among key populations of women and men veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32(1): 11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olenick M, Flowers M, Diaz VJ: US veterans and their unique issues: enhancing health care professional awareness. Adv Med Educ Pract 2015; 6: 635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Richardson JD, Ketcheson F, King L, et al. : Psychiatric comorbidity pattern in treatment-seeking veterans. Psychiatry Res 2017; 258: 488–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Maguen S, Madden E, Cohen B, et al. : The relationship between body mass index and mental health among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. J Gen Intern Med 2013; 28(2): 563–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kinsinger LS, Jones KR, Kahwati L, et al. : Peer reviewed: design and dissemination of the MOVE! Weight-management program for veterans. Prev Chronic Dis 2009; 6(3): A98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Littman AJ, Damschroder LJ, Verchinina L, et al. : National evaluation of obesity screening and treatment among veterans with and without mental health disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2015; 37(1): 7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hoerster KD, Lai Z, Goodrich DE, et al. : Weight loss after participation in a national VA weight management program among veterans with or without PTSD. Psychiatr Serv 2014; 65(11): 1385–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Goldberg RW, Reeves G, Tapscott S, et al. : “MOVE!”: outcomes of a weight loss program modified for veterans with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2013; 64(8): 737–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Klingaman EA, Viverito KM, Medoff DR, Hoffmann RM, Goldberg RW: Strategies, barriers, and motivation for weight loss among veterans living with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2014; 37(4): 270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Klingaman EA, Hoerster KD, Aakre JM, Viverito KM, Medoff DR, Goldberg RW: Veterans with PTSD report more weight loss barriers than veterans with no mental health disorders. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2016; 39: 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Maguen S, Hoerster KD, Littman AJ, et al. : Iraq and Afghanistan veterans with PTSD participate less in VA's weight loss program than those without PTSD. J Affect Disord 2016; 193: 289–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Albert PR: Why is depression more prevalent in women? J Psychiatry Neurosci 2015; 40(4): 219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dixon JB, Dixon ME, O'Brien PE: Depression in association with severe obesity: changes with weight loss. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163(17): 2058–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Frayne S, Phibbs C, Saechao F, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 4: Longitudinal Trends in Sociodemographics, Utilization, Health Profile, and Geographic Distribution, p 144 Washington, DC, Women's Health Evaluation Initiative, Women's Health Services, Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Collins LM, Lanza ST. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences, Vol. 718 Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zulman DM, Asch SM, Martins SB, Kerr EA, Hoffman BB, Goldstein MK: Quality of care for patients with multiple chronic conditions: the role of comorbidity interrelatedness. J Gen Intern Med 2014; 29(3): 529–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Scherrer JF, Salas J, Chard KM, et al. : PTSD symptom decrease and use of weight loss programs. J Psychosom Res 2019; 127: 109849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dennis M, Scott CK: Managing addiction as a chronic condition. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2007; 4(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Seal KH, Metzler TJ, Gima KS, Bertenthal D, Maguen S, Marmar CR: Trends and risk factors for mental health diagnoses among Iraq and Afghanistan veterans using Department of Veterans Affairs health care, 2002–2008. Am J Public Health 2009; 99(9): 1651–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pagoto S, Schneider KL, Whited MC, et al. : Randomized controlled trial of behavioral treatment for comorbid obesity and depression in women: the be active trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2013; 37(11): 1427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ma J, Rosas LG, Lv N, et al. : Effect of integrated behavioral weight loss treatment and problem-solving therapy on body mass index and depressive symptoms among patients with obesity and depression: the RAINBOW randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 321(9): 869–79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Goodrich DE, Klingaman EA, Verchinina L, et al. : Sex differences in weight loss among veterans with serious mental illness: observational study of a national weight management program. Women’s Health Issues 2016; 26(4): 410–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Muralidharan A, Niv N, Brown CH, et al. : Impact of online weight management with peer coaching on physical activity levels of adults with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv 2018; 69(10): 1062–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Young AS, Cohen AN, Goldberg R, et al. : Improving weight in people with serious mental illness: the effectiveness of computerized services with peer coaches. J Gen Intern Med 2017; 32(1): 48–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]