Abstract

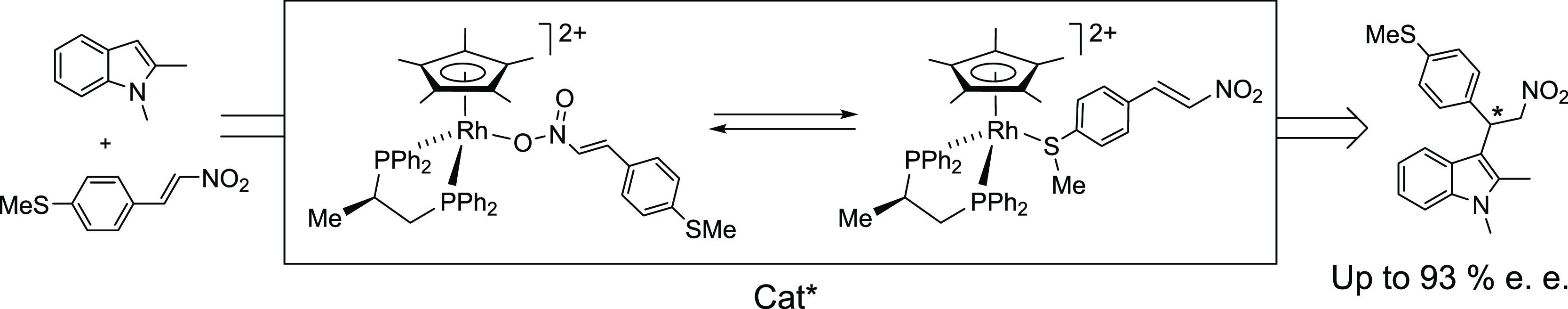

The reaction of the rhodium aqua-complex (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos} (OH2)][SbF6]2 [Cp* = C5Me5, Prophos = propane-1,2-diyl-bis(diphenylphosphane)] (1) with trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene (MTNS) gives two linkage isomers (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(κ1O-MTNS)]2+ (3-O) and (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(κ1S-MTNS)]2+ (3-S) in which the nitrostyrene binds the metal through one of the oxygen atoms of the nitro group or through the sulfur atom, respectively. Both isomers are in equilibrium in dichloromethane solution, the equilibrium constant being affected by the temperature in such a way that when the temperature increases, the relative concentration of the oxygen-bonded isomer 3-O increases. The homologue aqua-complex of iridium, (SIr,RC)-[Cp*Ir{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (2), also reacts with MTNS; but only the sulfur-coordinated isomer (SIr,RC)-[Cp*Ir{(R)-Prophos}(κ1S-MTNS)]2+ (4-S) is detected in the solution by NMR spectroscopy. The crystal structures of 3-S and 4-S have been elucidated by X-ray diffractometric methods. Complexes 1 and 2 catalyze the Friedel–Crafts reaction of indole, N-methylindole, 2-methylindole, or N-methyl-2-methylindole with MTNS. Up to 93% ee has been achieved for N-methyl-2-methylindole. With this indole, the ee increases as conversion increases, ee at 263 K is lower than that obtained at 298 K, and the sign of the chirality of the major enantiomer changes at temperatures below 263 K. Detection and characterization of the catalytic intermediates metal-aci-nitro and the free aci-nitro compound as well as detection of the Friedel–Crafts (FC)-adduct complex involved in the catalysis allowed us to propose a plausible double cycle that accounts for the catalytic observations.

Introduction

Chiral catalysts based on transition metals are among the most efficient and versatile for the preparation of enantioenriched compounds.1 Metallic catalysts activate organic substrates by coordination and chiral induction takes place when the reaction occurs within the asymmetric environment generated around the metal by enantiopure ligands.2

In particular, transition-metal complexes efficiently catalyze asymmetric Friedel–Crafts (FC) reactions,3 and several metallic systems have been successfully applied to the alkylation of indoles with nitroalkenes. Thus, following the pioneering work of Bandini et al.,4 homogeneous systems based on copper,5 zinc,6 and, to a lesser extent, nickel,7 platinum,8 or palladium9 catalyze this transformation. Additionally, metal-containing hydrogen bond donors also catalyze the FC reaction between nitroalkenes and indoles through second coordination sphere mechanisms,10 in some instances, enantioselectively.11

However, theoretical or experimental studies about the operating catalytic cycles are very scarce and, therefore, no reliable data about the active metallic intermediates are available. Although it should be taken into account that intermediates detected under catalytic conditions may not be responsible for the catalysis, the study of the metallic intermediates involved in catalytic processes is one of the most powerful tools available for the chemists to get a deep insight into the reaction mechanisms.

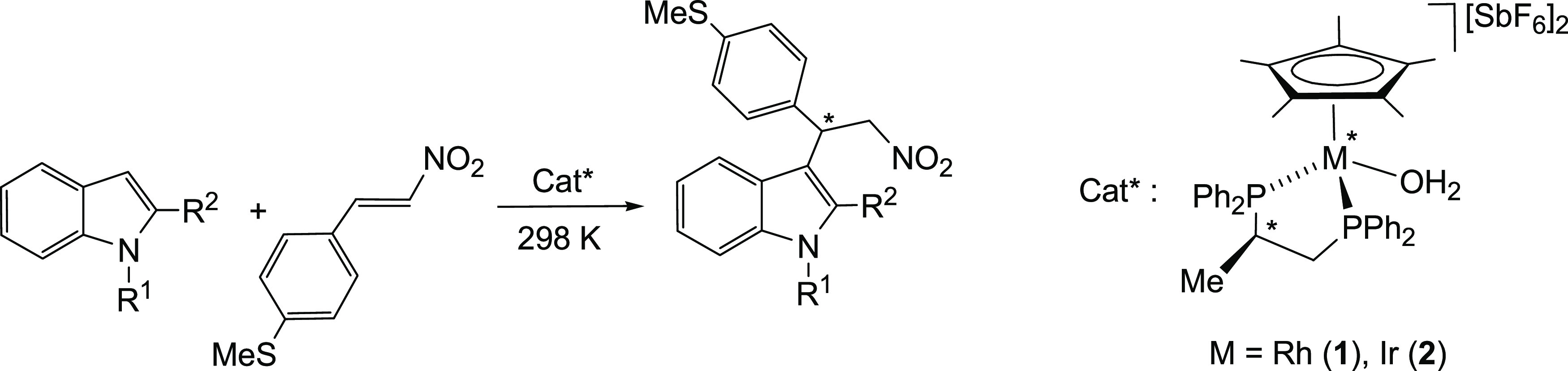

In this context, we have recently reported on the application of the chiral half-sandwich rhodium and iridium complexes (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 [Prophos = propane-1,2-diyl-bis(diphenylphosphano); M = Rh (1), Ir (2)] (Scheme 1)12 as catalyst precursors for the Michael-type Friedel–Crafts reaction between indoles and trans-β-nitrostyrenes. High yield and excellent enantioselectivity were achieved. The true catalyst was shown to be the dicationic species of formula (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(nitrostyrene)]2+ in which the nitrostyrene coordinates with the metal through one of the oxygen atoms of the nitro group. aci-Nitro and FC-adduct rhodium complexes, involved in the process, were characterized by spectroscopic means. On the basis of these data, together with theoretical and kinetic studies, the catalytic stereochemical outcome was satisfactorily explained.13

Scheme 1. Chiral Complexes [Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(H2O)][SbF6]2.

Here, we disclose our findings about the behavior of trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene, instead of unfunctionalized β-nitrostyrene, as an electrophile in the abovementioned reaction.

Results and Discussion

Reaction of the Aqua-Complex (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(H2O)][SbF6]2 with trans-4-Methylthio-β-nitrostyrene

When an excess of different trans-β-nitrostyrenes was added to solutions of (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(H2O)][SbF6]2 (M = Rh (1), Ir (2)) in dichloromethane, an equilibrium between the starting aqua-complex and the corresponding nitrostyrene complex (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(nitrostyrene)]2+ was reached. Addition of 4 Å molecular sieves drives this equilibrium completely to the nitrostyrene-coordinated compound side. The reaction is stereospecific and takes place with retention of the configuration of the metal center. Spectroscopic and diffractometric data reveal that the nitrostyrene ligand coordinates with the metal through one of the oxygen atoms of its nitro group and unveil the strong electronic activation of the β-carbon atom of this ligand toward nucleophilic attack.13

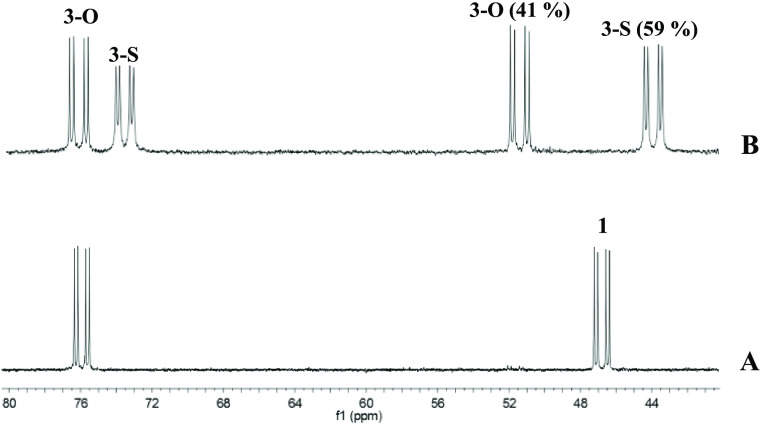

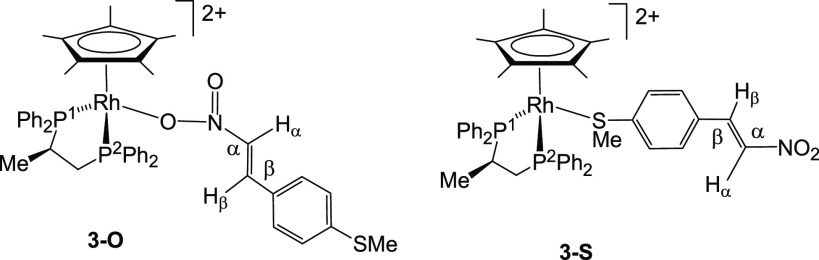

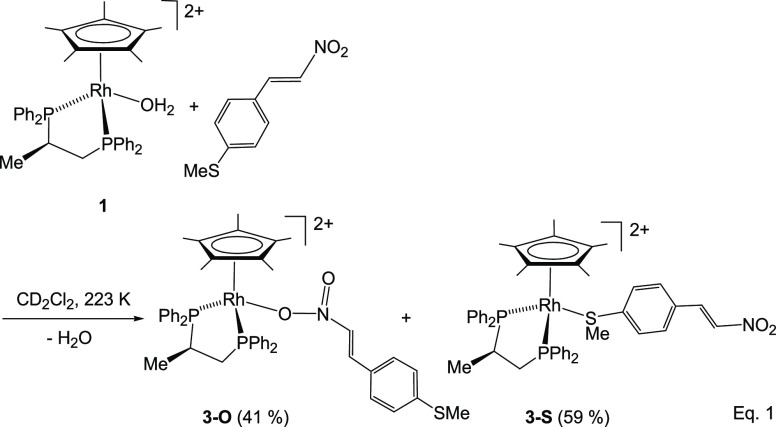

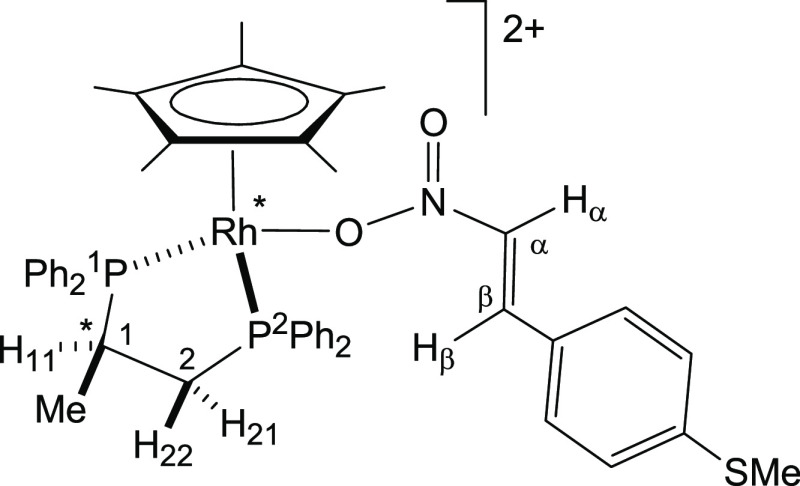

However, when one equivalent of the functionalized nitrostyrene trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene (MTNS) was added to CD2Cl2 solutions of the rhodium complex (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1), in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieves, at 223 K, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra showed that the starting aqua-complex had completely reacted to give a mixture of two rhodium complexes in approximately 41/59 molar ratio. Thus, the two double doublets corresponding to complex 1 (Figure 1, trace A) disappeared and two pairs of double doublets emerged. We assign the new resonances to the two linkage isomers, 3-O and 3-S (eq 1), in which the nitrostyrene coordinates with the metal through one of the oxygen atoms of the nitro group or through the sulfur atom, respectively. Table 1 shows 1H and 13C{1H} NMR data for selected nuclei of the coordinated nitrostyrene ligand of these isomers. The variation of chemical shifts with respect to those measured for the corresponding nuclei of the free ligand (Δδ) is also tabulated. In particular, a comparison of this variation, for the Hβ and SMe protons and for the Cβ and SMe carbons of both isomers, allows us to distinguish between their coordination modes. Thus, ΔδHβ and ΔδCβ values of −0.98 and +8.57 ppm, respectively, were attributed to the O-coordinated isomer, whereas −0.04 and −0.14 ppm were ΔδHβ and ΔδCβ, respectively, for the S-coordinated isomer. On the other hand, −0.92 and +9.32 were Δδ measured for the protons and carbon of the SMe group, respectively, in the S-coordinated isomer, whereas in the O-coordinated compound, −0.01 and +0.06 ppm were Δδ recorded for these protons and carbon nuclei, respectively. These data strongly suggest that in the minor isomer, one of the NO2 oxygen atoms completes the coordination sphere of the rhodium, and in the major isomer, the nitrostyrene coordinates with the metal through the sulfur atom of the SMe group. Regarding reactivity, it is convenient to be aware that the NMR data indicated that when the nitrostyrene oxygen binds to the metal, the β carbon is activated for nucleophilic attack (ΔδCβ = +8.57), but this activation is not apparent when coordination occurs through the sulfur atom (ΔδCβ = −0.14).

|

1 |

Notably, EXSY experiments revealed that the 3-O and 3-S linkage isomers exchange with each other and also with free trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene. Moreover, the equilibrium constant 3-O ⇆ 3-S is strongly affected by the temperature. Figure 2 shows the 31P{1H} NMR spectra of 3-O ⇆ 3-S equilibrium mixtures at different temperatures. As the temperature increases, the concentration of 3-O increases at the expense of the concentration of 3-S and vice versa. Regarding the catalytic properties of this compound, it is interesting to notice that at temperatures below 233 K, complex 3-O accounts for less than 50% of the rhodium present in the solution. Additionally, below 213 K, the broadening of the doublets assigned to complex 3-S is apparent. Taking into account that in this isomer the sulfur atom is a stereogenic center, we tentatively propose that, whereas above 213 K epimerization at sulfur is rapid on the NMR time scale, below this temperature this process is significantly slowed down. On the other hand, above 263 K the four resonances slowly broaden, and the doublets assigned to 3-S coalesce at around 298 K. The thermal stability of the compound avoids reaching the temperature region of fast exchange between both isomers. In fact, at 298 K, a small amount of the decomposition cation14 [Cp*RhCl{(R)-Prophos}]+ was observed. Finally, from the linear dependence of ln K versus the reciprocal of the temperature (Figure 3), the thermodynamic parameters for the equilibrium 3-O ⇆ 3-S, ΔG° = 0.84 ± 0.28 kcal·mol–1, ΔH° = −3.24 ± 0.13 kcal·mol–1, and ΔS° = −13.93 ± 0.54 cal·mol–1·K–1, were derived.

Figure 1.

31P{1H} NMR spectra of complex 1 (trace A) and a mixture of 3-O and 3-S (trace B) at 223 K.

Table 1. Selected 1H and 13C{1H} NMR Data (223 K) for the Complexes 3-O and 3-S, in CD2Cl2a.

| minor isomer (3-O) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1H NMR | |||

| δHβ | ΔδHβ | δSMe | ΔδSMe |

| 6.95 | –0.98 | 2.49 | –0.01 |

| 13C {1H} NMR | |||

| δCβ | ΔδCβ | δSMe | ΔδSMe |

| 147.63 | +8.57 | 14.75 | +0.06 |

| major isomer (3-S) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1H NMR | |||

| δHβ | ΔδHβ | δSMe | ΔδSMe |

| 7.89 | –0.04 | 1.58 | –0.92 |

| 13C {1H} NMR | |||

| δCβ | ΔδCβ | δSMe | ΔδSMe |

| 138.95 | –0.14 | 23.13 | +9.32 |

Chemical shifts in ppm; coupling constants in Hz.

Figure 2.

31P{1H} NMR spectra of a mixture of complexes 3-O and 3-S at different temperatures. The asterisk denotes the decomposition species [Cp*RhCl{(R)-Prophos}]+.

Figure 3.

Plot of ln K versus 1/T for the equilibrium 3-O ⇆ 3-S.

The iridium analogue (SIr,RC)-[Cp*Ir{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (2) also reacted with MTNS. However, only the S-coordinated isomer (SIr,RC)-[Cp*Ir{(R)-Prophos}(κ1S-MTNS)][SbF6]2 (4-S) was detected for this metal. The low solubility of the resulting compound in the usual organic solvents precludes its complete spectroscopic characterization, but single crystals for diffractometric studies were obtained from dichloromethane/pentane mixtures.

Molecular Structure of the Complex [Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(MTNS)][SbF6]2 (M = Rh (3-S), Ir (4-S))

Single crystals of the complexes were grown by slow diffusion of pentane into dichloromethane solutions. Molecular representations of the cations are shown in Figure 4 and selected structural parameters are listed in Table 2.

Figure 4.

Molecular representation of the cations of the compounds 3-S and 4-S (one of the crystallographically independent molecules of each unit cell). For clarity, hydrogen atoms have been omitted.

Table 2. Selected Bond Lengths (Å) and Angles (deg) for 3-S and 4-Sa.

|

3-S (M = Rh) |

4-S (M = Ir) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| molecule 1 | molecule 2 | molecule 1 | molecule 2 | |

| M-S(1) | 2.379(3) | 2.388(3) | 2.373(5) | 2.368(5) |

| M-P(1) | 2.332(3) | 2.330(3) | 2.327(4) | 2.323(5) |

| M-P(2) | 2.397(2) | 2.403(2) | 2.366(4) | 2.376(4) |

| M-Ga̲ | 1.899(6) | 1.912(6) | 1.910(9) | 1.930(10) |

| S(1)-M-P(1) | 85.11(9) | 84.97(9) | 84.77(17) | 84.99(17) |

| S(1)-M-P(2) | 89.67(9) | 89.99(9) | 89.45(16) | 89.68(16) |

| S(1)-M-Ga̲ | 125.97(18) | 125.68(18) | 125.7(3) | 125.8(3) |

| P(1)-M-P(2) | 82.91(9) | 82.91(9) | 82.62(16) | 82.90(16) |

| P(1)-M-Ga̲ | 125.60(18) | 126.14(18) | 125.9(3) | 126.5(3) |

| P(2)-M-Ga̲ | 132.28(18) | 131.95(17) | 132.8(3) | 131.7(3) |

G represents the centroid of the Cp* ligand.

Both cations exhibit a “three-legged piano-stool” geometry. An η5-C5Me5 group occupies three fac positions and the two phosphorus atoms of the chelate diphosphano and the sulfur atom of the nitrostyrene ligand complete the coordination sphere of the metal. The absolute configuration of the complexes is SM,RC,SS.15 Asymmetric units of both complexes comprise two crystallographically independent but chemically equivalent molecules.

At a molecular level, both complexes exhibit similar parameters. Furthermore, bond lengths and angles of a Cp*M{(R)-Prophos} fragment in complexes 3-S and 4-S agree with those found in parent aqua complexes.12b Coordination of the sulfur atom is apparent in both cases, the two M–S bond distances being comparable, in the 2.368(5)–2.388(3) Å range. The 5-membered metallacycles M-P(1)-C(14)-C(23)-P(2) adopt a λ conformation. These puckered rings may be characterized by two parameters.16 On the one hand, their Cremer and Pople ring-puckering amplitude (Q ∼ 0.5 Å, see the Supporting Information) nicely agrees with those observed in other Cp*M{(R)-Prophos} complexes.12b,17 On the other hand, their phase angle (ϕ) values between 62.84(3) and 65.33(1)°, characteristic of 3T2 with a contribution of 3E conformations, have been found.

Catalytic Reactions

Complexes 1 and 2 catalyze the reaction between indoles and MTNS. Table 3 shows a selection of the obtained results together with the reaction conditions. The results shown are the average of at least two comparable reaction runs. The reactions were carried out in CH2Cl2, at 298 K, in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieves. A molar ratio cat*/MTNS/indole of 1/30/20 (5 mol % catalyst loading) was employed in all cases.

Table 3. Results of Selected Asymmetric FC Alkylation Reactions of Indoles with MTNSa.

| entry | cat* | R1 | R2 | t (min) | conv.b (%) | eec (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | H | H | 30 | 55 | rac |

| 2 | 2 | 30 | 22 | –2 | ||

| 3 | 1 | Me | H | 30 | 90 | +12 |

| 4 | 2 | 30 | 43 | +15 | ||

| 5 | 1 | H | Me | 30 | 81 | +3 |

| 6 | 2 | 30 | 48 | +15 | ||

| 7 | 1 | Me | Me | 5 | 100 | +93 |

| 8 | 2 | 30 | 100 | –21 |

Reagents and conditions: catalyst (0.03 mmol, 5.0 mol %), MTNS (0.90 mmol), indole (0.60 mmol), 4 Å molecular sieves (100 mg), and CH2Cl2 (4 mL).

Based on indole. Determined by 1H NMR spectroscopy.

Determined by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Changes in the sign indicate that the opposite enantiomer was preferentially obtained.

Catalytic runs were quenched after the reaction times shown in Table 3 by adding excess of a saturated solution of N(nBu4)Br in methanol. The reactions are clean: only the addition product and the remaining unreacted reagents were detected in the NMR spectra of the crude reaction mixture. The rhodium complex is more active than the iridium analogue, but it is remarkable that the iridium compound catalyzes the reaction although, under the catalytic conditions, the presence of the O-coordinated isomer (the one in which the nitrostyrene is activated for nucleophilic attack) was not detected by NMR (see above). As the best results, in both reaction rate and enantioselectivity, were obtained for N-methyl-2-methylindole using the rhodium complex as catalyst, we chose this system as the model to continue our study.

Effect of the Temperature

The model reaction was performed at different temperatures in the range 298–233 K, the remaining conditions being maintained unchanged. At a fixed temperature, the ee changes as conversion increases and, in some cases, it changes even when indole (the limiting reagent) is no longer detected by 1H NMR spectroscopy in the reaction medium. Table 4 shows the ee values measured when at least three identical ee values have been obtained at reaction times longer than that needed to achieve complete conversion. Changes in the sign of the enantioselectivity indicate that the opposite enantiomer was preferentially obtained. ee values up to 93% were obtained at temperatures higher than 263 K. Unexpectedly, by reducing the temperature from 298 to 263 K, a decrease from 93 to 55% in the enantioselectivity was observed. Notably, this decrease results in a switch in the sign of the major isomer at the lowest temperatures measured (see the Supporting Information).

Table 4. Effect of the Temperaturea.

To try to explain this behavior, we studied the catalytic process by NMR spectroscopy.

Reaction of Complexes 3 with N-Methyl-2-methylindole

Plausibly, the catalytic cycle starts with the interaction between the activated O-coordinated electrophile in (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(κ1O-MTNS)]2+ and the indole. To confirm this proposal, at 193 K, the reaction of a 30/70 molar ratio mixture of 3-O/3-S (Figure 5, trace A) -formed in situ from complex 1 (1 equiv) and MTNS (10 equiv), in the presence of 4 Å molecular sieves- with N-methyl-2-methylindole (5 equiv) was monitored by NMR spectroscopy. After the addition of the indole, the 31P{1H} NMR spectra showed the immediate disappearance of complexes 3 and the formation of two rhodium complexes, 5, in a molar ratio of around 80/20, characterized by two new pairs of double doublets (Figure 5, trace B). Both starting isomers, 3-O and 3-S, were transformed into 5; 3-O by direct reaction with the indole and 3-S, most probably, after conversion into 3-O via the equilibrium 3-O ⇆ 3-S (Scheme 2). The selected region of the 1H NMR spectrum shown in Figure 5, trace B shows a pair of coupled signals centered at 6.12 (Hα) and at ca. 5.25 ppm (Hβ, overlapped; major isomer) together with two broad doublets at 6.02 (Hα) and 4.76 ppm (Hβ; minor). Signals at about 17 ppm, attributed to NO2H groups, are also observed. Complexes 5 should be the aci-nitro complexes formulated in Scheme 2, resulting from the formation of the C–C bond between the C3 carbon of the indole and the Cβ carbon of the coordinated nitroalkene in 3-O.18 Apart from the excess of indole (the C3 indole proton gives a singlet at about 6.2 ppm), trace B also shows the presence of two new organic compounds characterized by one singlet at around 14 ppm and a doublet centered at 5.45 ppm and a complex multiplet centered at about 5.2 ppm. The singlet and the doublet were attributed to the NO2H group and the Hβ proton, respectively, of the free aci-nitro ligand (6) displaced from the coordination sphere of the metal in 5 by a new molecule of MTNS (Scheme 2). The complex multiplet corresponds to the three aliphatic protons of the FC adduct 7 (Scheme 3), as determined by comparison with an authentic sample obtained in an independent catalytic experiment. Further treatment at 223 K gave rise to the gradual disappearance of the indole together with the progressive formation of the FC adduct 7 at the expense of the free aci-nitro compound 6 (traces C and D). The aci-nitro compound 6 rearranges to the FC adduct 7,19 most probably, through the prototropic tautomerism shown in Scheme 3.13,18

Figure 5.

Trace A: selected regions of the 1H and 31P{1H} NMR spectra of a mixture of 3-0 and 3-S at 193 K. Trace B: measured at 193 K after the addition of N-methyl-2-methylindole (catalyst/nitroalkene/indole molar ratio, 1/10/5). Traces C, D: measured at 193 K after heating up to 223 K for 20 min. Trace E: measured at 193 K after total consumption of the indole. Trace F: selected regions of the 1H and 31P{1H} NMR spectra of a mixture of 1, racemic FC adduct 7, and 4 Å MS (1/7 molar ratio, 1/5) at 193 K. The asterisk denotes residual, not deuterated dichloromethane. A double asterisk denotes the decomposition species [Cp*RhCl{(R)-Prophos}]+ (see Figure 2 and the corresponding text).

Scheme 2. Reaction of Complexes 3 with N-Methyl-2-methylindole.

Scheme 3. Prototropic Tautomerism of the aci-Nitro Compound 6 to the FC Adduct 7.

The 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the resting state of the catalyst consisted of a pair of double doublets in about 20/80 molar ratio (8-S, trace E). To determine the nature of these complexes, excess of racemic FC adduct 7 was added to a dichloromethane solution of the rhodium aqua-complex (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1). The 1H and 31P{1H} NMR spectra of the resulting solution are consistent with a mixture of the resting state complexes 8-S (Figure 5, trace E) and starting complex 1. The value of the chemical shift of the phosphorus nuclei indicates that the coordination of the FC adduct takes place through the sulfur (Scheme 4).

Scheme 4. Sulfur-Coordinated FC-Adduct Rhodium Complex 8-S, the Resting State of the Catalyst.

The solution’s spectroscopic data obtained from the reaction between MTNS and N-methyl-2-methylindole catalyzed by (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 closely resemble those reported for the same reaction with parent trans-β-nitrostyrene.13 In both cases, metal-nitroalkene, metal-aci-nitro, free aci-nitro, and metal-FC-adduct intermediates have been spectroscopically detected and characterized. Moreover, also in both cases, at a fixed temperature, the ee changes with reaction time and, simply by changing the temperature, each of the two enantiomers of the FC adduct can be preferentially obtained.

The catalytic cycles A and B (Figure 6) were proposed for the parent nitrostyrene on the basis of theoretical and experimental studies reported in ref (13). From these studies it was also determined that the rate-limiting step was the prototropic tautomerism of the corresponding aci-nitro compound 5 or 6 (see Schemes 2 and 3). This prototropy could take place when the aci-nitro compound is not coordinated to the metal rendering the corresponding FC adduct (steps 6 → 8 → 7, Figure 6) or, alternatively, when it is coordinated to the metal (step 5 → 8-O). Additionally, the reported DFT studies for the unsubstituted nitrostyrene case13 revealed that a dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) occurred on 5. At 298.15 K, the lowest barrier for the whole process 5 → 7 was for the S epimer at Cβ through the free aci-nitro compound 6. However, at 233.15 K, the lowest barrier for the same process is for the R epimer at Cβ through the FC-adduct complex 8-O. As the 5 → 3-O step is reversible, in both cases, the less-suited enantiomer goes back into the combination of the substrates, i.e., a nitrostyrene complex and indole.

Figure 6.

Catalytic cycle proposed for the reaction between N-methyl-2-methylindole and trans-β-nitrostyrene catalyzed by (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2.

From the behavior encountered for the FC reaction with trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene, identical to that found for the parent nitrostyrene, we assume that a similar mechanism would be operating in both cases. In fact, all of the experimental observations (no DFT calculations have been carried out for the reaction with trans-4-methylthio-β-nitrostyrene) made for the reaction with MTNS can be explained. Thus, ee increases when conversion increases because cycle A is reversible and a DKR occurs in the aci-nitro complex 5. As conversion increases, the turnover number of cycle A also increases in this way, improving the ee via DKR. At low temperatures, even when the amount of indole is negligible (not detected by NMR), the reversible cycle A works, improving the ee.

The decrease of the ee value as the temperature decreases can be accounted for by assuming that at higher temperatures the step 6 → 7 is kinetically favored for one of the enantiomers of the FC adduct 7 over the metal-assisted prototropy 5 → 8 but, at lower temperatures, the latter route, which preferentially gives the opposite enantiomer of 7, becomes competitive. Therefore, at low temperatures, the ee of the FC adduct is lower because a part of the product is obtained through the route 5 → 8 → 7. Consequently, at temperatures lower than 263 K, the ee further decreases, promoting a change in the sign of the chirality of the adduct. We have not carried out catalytic runs at temperatures below 233 K because the catalytic reaction becomes too slow.

Conclusions

One of the nitro group oxygens and the sulfur atom of MTNS can coordinate with the half-sandwich rhodium or iridium fragment “Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}” rendering κ1O or κ1S complexes. In solution, these linkage isomers are in equilibrium and in the iridium case, this equilibrium is strongly shifted to the complex that exhibits a κ1S coordination mode. Only the κ1O-coordinated nitroalkene was activated for the nucleophilic attack of indole, which is the first step of the catalytic cycle. However, the equilibrium between the κ1S and κ1O isomers facilitates the catalytic reaction. In fact, both metallic complexes catalyze the Michael-type FC reaction between the indoles and MTNS in quantitative yield and with up to 93% ee. Detection and characterization of the key intermediates metal-aci-nitro (5), metal-FC-adduct (8), and free aci-nitro compound (6) allow us to propose a mechanism that accounts for the effect of conversion and temperature over the measured ee.

Experimental Section

General Comments

All preparations have been carried out under argon. All solvents were treated in a PS-400-6 Innovative Technologies Solvent Purification System (SPS) and degassed prior to use. 1H, 13C, and 31P NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AV-300 (300.13 MHz), a Bruker AV-400 (400.16 MHz), or a Bruker AV-500 (500.13 MHz) spectrometer. In both 1H NMR and 13C NMR measurements, the chemical shifts are expressed in ppm downfield from SiMe4. The 31P NMR chemical shifts are relative to 85% H3PO4. J values are given in Hz. COSY, NOESY, HSQC, HMQC, and HMBC 1H–X (X = 1H, 13C, 31P, 15N) correlation spectra were obtained using standard procedures. Analytical high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on an Alliance Waters 2695 (Waters 2996 PDA detector) instrument using a chiral column Chiralpak IB (0.46 × 25 cm2) and an IB guard (0.46 × 1 cm2). High-resolution mass spectra were obtained with a Micro Tof-Q Bruker Daltonics spectrometer.

Preparation of the Complex [Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(MTNS)][SbF6]2 (M = Rh 3, Ir 4)

In an NMR tube, at 223 K, to a suspension of (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (M = Rh (1), Ir (2)) (0.024 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.45 mL), MTNS (4.7 mg, 0.024 mmol) and 4 Å MS (15 mg) were added. The resulting solution containing complexes 3 and 4 was analyzed by NMR without any further purification. Crystals suitable for X-ray analysis for both complexes were obtained by crystallization from CH2Cl2/n-pentane solutions. Yield: complex 3, 15.5 mg (49%); complex 4, 28.0 mg (83%).

(SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(MTNS)][SbF6]2 (3)

3-O

1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ

= 7.98–6.90 (m, 24H, HAr), 7.24 (brd, 1H, Hα), 6.95 (brd, 1H, Hβ), 3.56 (m, 1H,

H21), 3.09 (m, 1H, H11), 2.49 (s, 3H, SMe),

2.41 (m, 1H, H22), 1.39 (brs, 15H, C5Me5), 1.23 ppm (m, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR

(75.48 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 151.92–120.10

(CAr), 147.63 (Cβ), 134.48 (Cα), 107.10 (brs, C5Me5), 30.04

(m, C2), 31.54 (m, C1), 15.82 (dd, J(P,C) = 17.5 and 4.6 Hz, Me), 14.75 (SMe), 10.23 ppm (C5Me5). 31P{1H} NMR

(121.42 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 75.91

(dd, J(Rh,P) = 131.2 Hz, J(P,P)

= 38.7 Hz, P1), 51.40 ppm (dd, J(Rh,P)

= 132.5 Hz, P2).

3-S

1H NMR (300.13 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ

= 7.98–6.90 (m, 24H, HAr), 7.89 (brd, 1H, Hβ), 7.50 (brd, 1H, Hα) 3.67 (m, 1H,

H11), 3.61 (m, 1H, H21), 2.48 (m, 1H, H22), 1.58 (s, 3H, SMe), 1.50 (brs, 15H, C5Me5), 1.31 ppm (m, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR

(75.48 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 141.58–120.97

(CAr), 138.95 (s, Cβ), 135.90 (s, Cα), 108.57 (brs, C5Me5), 32.33 (m, C1), 29.89 (m, C2), 23.13

(s, SMe), 15.59 (dd, J(P,C) = 17.6 and 4.2 Hz, Me),

10.23 ppm (s, C5Me5). 31P{1H} NMR (121.42 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 73.34 (dd, J(Rh,P) = 123.6 Hz, J(P,P) = 38.9 Hz, P1), 43.84 ppm (dd, J(Rh,P) = 129.6 Hz, P2).

NMR Studies for the Equilibrium 3-O ⇆ 3-S

In an NMR tube, at 193 K, to a suspension of (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1) (20.4 mg, 0.018 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.50 mL), MTNS (3.5 mg, 0.018 mmol) and 4 Å MS (15 mg) were added. The resulting solution containing complexes 3-O and 3-S was analyzed by NMR at different temperatures. Thermodynamic parameters were obtained through Van’t Hoff analyses.

(SIr,RC)-[Cp*Ir{(R)-Prophos}(κ1S-MTNS)][SbF6]2 (4-S)

31P{1H} (121.42 MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 38.26 (d, P1), 8.71 ppm (d, P2).

Catalytic Procedure for the Friedel–Crafts Reaction

Under argon, to a Schlenk flask equipped with a magnetic stirrer, 0.03 mmol (5 mol %) of (SM,RC)-[Cp*M{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (M = Rh (1), Ir (2)), the solvent (4 mL), 0.90 mmol of MTNS, and about 100 mg of 4 Å MS were added. The resulting mixture was stirred for 15 min at the selected temperature and then the corresponding indole (0.60 mmol) was added. After the appropriate reaction time, the reaction was quenched by addition of a methanolic solution of [N(nBu)4]Br. The resulting suspension was vacuum-concentrated until dryness. The residue was extracted with Et2O (4 × 6 mL), and the resulting oil was analyzed by NMR and HPLC.

Procedure for the Synthesis of 5

At 193 K, in an NMR tube, to a suspension

of (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1) (17.0 mg, 0.014 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.3 mL), MTNS (27.3 mg, 0.140 mmol) and 4 Å

MS (15 mg) were added. After 20 min, N-methyl-2-methylindole

(10.2 mg, 0.070 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.15 mL) was

added to the resulting solution at 193 K. The resulting solution was

analyzed by NMR without any further purification and showed the presence

of complexes 5 in 80/20 5a/5b molar ratio.

5a

1H NMR (400.16 MHz, CD2Cl2, 193 K): δ = 17.6 (br, 1H, OH), 6.12 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, Hα), 5.25 (brd, 1H, Hβ), 3.57 (brs, 3H, NMe), 2.64 (s, 3H, Me), 2.37 (s, 3H, SMe), 1.26 (brs, 15H, C5Me5), 0.92 ppm (br, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR (100.16 MHz, CD2Cl2, 193 K): δ = 118.43 (Cα), 38.35 (Cβ), 34.86 (NMe), 14.75 (SMe), 14.27 (Me), 12.82 (Meindole), 8.99 ppm (C5Me5). 31P{1H} NMR (161.96 MHz, CD2Cl2, 193 K): δ = 75.96 (dd, J(Rh,P) = 129.9 Hz, J(P,P) = 42.4 Hz, P1), 50.32 ppm (dd, J(Rh,P) = 132.4 Hz, P2).

5b

1H NMR (400.16 MHz,

CD2Cl2, 193 K): δ = 17.5 (br, 1H, OH),

6.02 (brd, Hz, 1H, Hα), 4.76 (brd, 1H, Hβ), 3.58 (brs, 3H, NMe), 2.64 (s, 3H, Me), 2.39 (s, 3H, SMe), 1.31

(brs, 15H, C5Me5), 1.11 ppm (br, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR (100.16 MHz, CD2Cl2, 193 K): δ = 113.70 (Cα), 40.62 (Cβ), 29.65 (NMe), 14.70 (SMe), 14.57 (Meindole), 14.34 (Me),

9.21 ppm (C5Me5). 31P{1H} NMR (161.96 MHz, CD2Cl2, 193

K): δ = 76.83 (brdd, J(P,P) = 42.6 Hz, P1), 51.92 ppm (brdd, J(Rh,P) = 135.3 Hz, P2).

Preparation of the aci-Nitro Compound 6

At 193 K, in an NMR tube, to a suspension

of (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1) (12.4 mg, 0.010 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.3 mL), MTNS (58.6 mg, 0.300 mmol) and 4 Å

MS (15 mg) were added. After 20 min, N-methyl-2-methylindole

(29.0 mg, 0.200 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.15 mL) was

added to the resulting solution. The gradual consumption of the indole

with the concomitant appearance of the aci-nitro

compound was monitored using NMR at 233 K. When the indole was not

observed, compound 6 was fully characterized by NMR at

223 K in the presence of 7 (6/7 molar ratio: 85/15). 6. 1H NMR (500.13 MHz,

CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 13.41 (br, 1H, OH),

7.32–6.90 (m, 9H, HAr), 6.99 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, Hα), 5.56 (d, J =

8.1 Hz, 1H, Hβ), 3.65 (s, 3H, NMe), 2.50 (s, 3H,

SMe), 2.44 ppm (s, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR (125.77

MHz, CD2Cl2, 223 K): δ = 140-107 (CAr), 122.02 (Cα), 39.80 (Cβ), 29.80 (NMe), 14.87 (SMe), 10.40 ppm (Me).

Characterization of the Friedel–Crafts Adduct 7

1H NMR (400.16 MHz, CDCl3, RT): δ = 7.30–7.17 (m, HAr), 7.06 (t, J = 12.5 Hz, 1H), 5.28-5.20 (m, 2H, Hα), 5.16-5.08 (m, 1H, Hβ), 3.60 (s, 3H, NMe), 2.51 (s, 3H, SMe), 2.43 ppm (s, 3H, Me). 13C{1H} NMR (100.62 MHz, CDCl3, RT): δ = 143.67–106.60 (CAr), 77.37 (Cα), 38.86 (Cβ), 28.11 (NMe), 13.25 (SMe), 9.00 ppm (Me). HPLC (Chiralpak IB with IB guard, n-hexane:iPrOH (70:30) 1 mL/min), tR: 16.9 (minor), 18.4 min (major). HRMS (ESI): m/z = 341.4475 (calcd 341.4480 [C19H21N2O2S]+).

NMR Study of the Reversibility of Cycle A

At 193 K, in an NMR tube, MTNS (34.9 mg, 0.179 mmol) and 4 Å MS (15 mg) were added to a suspension of the complex (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(H2O)][SbF6]2 (1; 6.8 mg, 0.006 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.3 mL). After 20 min, N-methyl-2-methylindole (17.3 mg, 0.119 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.20 mL) was added to the resulting solution at the same temperature. The gradual consumption of the indole with the concomitant appearance of the aci-nitro compound 6 was then monitored by NMR spectroscopy at 243 K. N-methyl-2-methylindole progressively reacted and when the solution consisted of a mixture of 6, 7, and indole in a molar ratio of 82:16:2, trans-β-nitrostyrene (26.7 mg, 0.179 mmol) was added at the same temperature. At 243 K, the 1H NMR analysis showed the formation of the aci-nitro compound derived from trans-β-nitrostyrene and N-methyl-2-methylindole (6′). The measured 6/6′ molar ratios were 87:13 and 23:77 after 10 min and 1 h, respectively. Heating up to 298 K, 6 and 6′ evolved to the corresponding FC products 7 and 7′, respectively.

Procedure for the Preparation of [Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(FC-Adduct)]2+ (8-S)

At 193 K, in an NMR tube, to a suspension of (SRh,RC)-[Cp*Rh{(R)-Prophos}(OH2)][SbF6]2 (1) (25.0 mg, 0.022 mmol) in CD2Cl2 (0.5 mL), 7 (37.3 mg, 0.110 mmol, racemic) and 4 Å MS (15 mg) were added. The resulting solution was analyzed by NMR without any further purification and consisted of a mixture of complexes 8-S and 1, in 75/25, 8-S/1, and 65/35, 8-Sa/8-Sb molar ratios.

8-Sa

31P{1H} NMR (202.46 MHz, CD2Cl2, 263 K): δ = 72.78 (br, P1), 42.80 ppm (dd, J(Rh,P) = 129.2 Hz, J(P1,P2) = 34.3 Hz, P2).

8-Sb

31P{1H} NMR (202.46 MHz, CD2Cl2, 263 K): δ = 72.78 (br, P1), 43.21 ppm (dd, J(Rh,P) = 127.6 Hz, J(P1,P2) = 33.1 Hz, P2).

Crystal Structure Determination for Complexes 3-S and 4-S

X-ray diffraction data were collected on an APEX DUO Bruker diffractometer, using graphite-monochromated Mo κα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å). Single crystals were extracted from NMR tubes, manipulated, and selected at low temperature on an inert atmosphere (surrounded by dry ice). Compounds 3-S and 4-S crystallize on well-formed yellow and orange prisms, respectively. The prisms are stuck to each other. Several samples were tested before selecting the ones used in the data collections. Most of the tested samples exhibit doubled diffraction peaks and problems in reflection indexation, evidencing the existence of twinning.

Selected crystals were mounted on a fiber, coated with a protecting perfluoropolyether oil, and cooled to 100(2) K with an open-flow nitrogen gas. Data were collected using ω-scans with a narrow oscillation frame strategy (Δω = 0.3°). Selected crystals show isolated well-defined diffraction spots; more than 95% of the harvest reflections were indexed in an orthorhombic C2221 space group. Consequent data integration (with SAINT program)20 and structure solution (with direct methods with SHELXS)21 in C2221 lead to a problematic structural model in which only the heaviest atoms (Rh, Ir, S, and P) can be anisotropically refined. Furthermore, the observed residual density peaks are anomalously large and the second parameter of the weighting scheme is too large.

A careful inspection of reflection pointed out the existence of a pseudomerohedric twin, with a monoclinic lattice. Therefore, data have been integrated in a monoclinic system, and the structures have been refined by full-matrix least-squares on F2 with SHELXL program22 included in a Wingx program system23 as 2-component twins. It is noteworthy that the same twin law has been observed in rhodium and iridium complexes 3-S and 4-S. Furthermore, several crystallization assays led to the same feature.

All of the nonhydrogen atoms have been anisotropically refined and several rigid-body restraints have been included in the model.

CCDC 1972185 and 1972186 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Crystal Data for Complex 3-S

2(C46H50NF12NO2P2RhSSb2)·4(CH2Cl2); Mr = 2974.26; an orange plate, 0.101 × 0.167 × 0.198 mm3; monoclinic P21; a = 10.9772(6) Å, b = 46.096(3) Å, c = 10.9795(6) Å, β = 93.0010(10)°; V = 5548.0(5) Å3, Z = 2, Dc = 1.780 g/cm3; μ = 1.628 cm–1; min. and max. absorption correction factors: 0.7137 and 0.8251; 2θmax= 56.454°; 93 923 reflections measured, 27199 unique; Rint = 0.0430; number of data/restraint/parameters 27199/37/1331; R1= 0.0426 [25 806 reflections, I > 2σ(I)], wR(F2) = 0.1018 (all data); largest difference peak 1.551 e·Å–3; Flack parameter: −0.005(7); BASF parameter: 0.505.

Structural Data for 4-S

2(C46H50IrNF12NO2P2SSb2)·3(CH2Cl2)·2(H2O); Mr = 3103.94; a yellow prism, 0.053 × 0.098 × 0.104 mm3; monoclinic P21; a = 10.9760(18) Å, b = 46.000(8) Å, c = 10.9840(18) Å, β = 93.038(3)°; V = 5537.9(16) Å3, Z = 2, Dc= 1.861 g/cm3; μ = 3.687 cm–1; min and max absorption correction factors: 0.6212 and 0.7955; 2θmax = 55.134°; 59 017 reflections measured, 25 261 unique; Rint = 0.0501; number of data/restraint/parameters 25261/115/1321; R1= 0.0488[21281 reflections, I > 2σ(I)], wR(F2) = 0.1106 (all data); largest difference peak 1.574 e·Å–3; Flack parameter: 0.012(4); BASF parameter: 0.352.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades of Spain (CTQ2018-095561-BI00) and Gobierno de Aragón (Grupo Consolidado E05-17R: Catálisis Homogénea Enantioselectiva) for financial support. I.M. acknowledges the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain for the FPI grant. R.R. acknowledges the Ministerio de Economía y Competitividad of Spain for the Ramón y Cajal (RYC-2013-13800) grant. P.G.-O. acknowledges CSIC and Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades of Spain for the PTA contract. We wish to kindly acknowledge Dr. Duane Choquesillo Lazarte (Laboratorio de Estudios Cristalográficos, IACT-CSIC, Granada) for his skilled assistance in twinned crystal data treatment.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03485.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis; Jacobsen E. N.; Pfaltz A.; Yamamoto H., Eds.; Springer: New York, 1999; Vol. I–III. [Google Scholar]

- a Lewis Acids in Organic Synthesis, Yamamoto H. Ed., Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2000. [Google Scholar]; b Transition Metals for Organic Synthesis: Building Blocks and Fine Chemicals, Beller M.; Bolm C.; Carsten B. Eds.; Wiley-VCH, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Heravi M. M.; Zadsirjan V.; Masoumi B.; Heydari M. Organometal-catalyzed asymmetric Friedel-Crafts reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 879, 78–138. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2018.10.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandini M.; Garelli A.; Rovinetti M.; Tommasi S.; Umani-Ronchi A. Catalytic Enantioselective Addition of Indoles to Arylnitroalkenes: An Effective Route to Enantiomerically Enriched Tryptamine Precursors. Chirality 2005, 17, 522–529. 10.1002/chir.20189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sato T.; Arai T. Chiral Bis(oxazolidine)pyridine-Copper-Catalyzed Enantioselective Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles with Nitroalkenes. Synlett 2014, 25, 349–354. 10.1055/s-0033-1340311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Zhang G. A trinuclear Cu2Eu complex catalyzed asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylations of indoles with nitroalkenes. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2014, 40, 1–4. 10.1016/j.inoche.2013.11.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Arai T.; Yamamoto Y.; Awata A.; Kamiya K.; Ishibashi M.; Arai M. A. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Mixed 3,3′-Bisindoles and Their Evaluation as Wnt Signaling Inhibitors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 2486–2490. 10.1002/anie.201208918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Arai T.; Awata A.; Wasai M.; Yokoyama N.; Masu H. Catalytic Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts/Protonation of Nitroalkenes and N-Heteroaromatics. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 5450–5456. 10.1021/jo200546a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Arai T.; Wasai M.; Yokoyama Y. Easy Access to Fully Functionalized Chiral Tetrahydro-β-Carboline Alkaloids. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2909–2912. 10.1021/jo1025833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Wu J.; Li X.; Wu F.; Wan B. A New Type of Bis(sulfonamide)-Diamine Ligand for a Cu(OTf)2-Catalyzed Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation Reaction of Indoles with Nitroalkenes. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 4834–4837. 10.1021/ol201914r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Kim H. Y.; Kim S.; Oh K. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4476–4478. 10.1002/anie.201001484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Orthogonal enantioselectivity approaches using homogeneous and heterogeneous catalyst systems: Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indole. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4476-4478.; h Yokoyama N.; Arai T. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts reaction of N-heterocycles and nitroalkenes catalyzed by imidazoline-aminophenol-Cu complex. Chem. Commun. 2009, 3285–3287. 10.1039/b904275j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Arai T.; Yokoyama N. Tandem Catalytic Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts/Henry Reaction: Control of Three Contiguous Acyclic Stereocenters. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 4989–4992. 10.1002/anie.200801373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Corrigendum: Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 9555.; j Sui Y.; Liu L.; Zhao J.-L.; Wang D.; Chen Y.-L. Catalytic and asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with nitroacrylates. Application to the synthesis of tryptophan analogues. Tetrahedron 2007, 63, 5173–5183. 10.1016/j.tet.2007.03.175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Singh P. K.; Bisai A.; Singh V. K. Enantioselective Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with nitroalkenes catalyzed by a bis(oxazoline)-Cu(II) complex. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007, 48, 1127–1129. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2006.12.081. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Kumar P.; Lymperopoulou S.; Griffiths K.; Sampani S. I.; Kostakis G. E. Highly Efficient Tetranuclear ZnII2LnIII2 Catalysts for the Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles and Nitrostyrenes. Catalysts 2016, 6, 140. 10.3390/catal6090140. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b More G. V.; Bhanage B. M. Synthesis of a chiral fluorescence active probe and its application as an efficient catalyst in the asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indole derivatives with nitroalkenes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2015, 5, 1514–1520. 10.1039/C4CY01456A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Li W.-J. Synthesis of chiral benzene-based tetraoxazolines and their application in asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indole derivatives with nitroalkenes. Catal. Commun. 2014, 52, 53–56. 10.1016/j.catcom.2014.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Islam M. S.; Al Majid A. M. A.; Al-Othman Z. A.; Barakat A. Highly enantioselective Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indole with electron deficient trans-β-nitroalkenes using Zn(II)-oxazoline-imidazoline catalysts. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2014, 25, 245–251. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2013.11.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Jia Y.; Yang W.; Du D.-M. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with 3-nitro-2H-chromenes catalyzed by diphenylamine-linked bis(oxazoline) and bis(thiazoline) Zn(II) complexes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012, 10, 4739–4746. 10.1039/c2ob25360g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Peng J.; Du D.-M. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles with Nitrodienes and 2-Propargyloxy-β-nitrostyrenes Catalyzed by Diphenylamine-Linked Bis(oxazoline)-Zn(OTf)2 Complexes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 4042–4051. 10.1002/ejoc.201200382. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g McKeon S. C.; Müller-Bunz H.; Guiry P. J. Synthesis of Thiazoline–Oxazoline Ligands and Their Application in Asymmetric Catalysis. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 7107–7115. 10.1002/ejoc.201101335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; h Guo F.; Lai G.; Xiong S.; Wang S.; Wang Z. Monodentate N-Ligand-Directed Bifunctional Transition-Metal Catalysis: Highly Enantioselective Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles with Nitroalkenes. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 6438–6441. 10.1002/chem.201000540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Liu H.; Du D.-M. Development of Diphenylamine-Linked Bis(imidazoline) Ligands and Their Application in Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indole Derivatives with Nitroalkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 1113–1118. 10.1002/adsc.201000111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j McKeon S. C.; Müller-Bunz H.; Guiry P. J. New Thiazoline-Oxazoline Ligands and Their Application in the Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Reaction. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 4833–4841. 10.1002/ejoc.200900683. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; k Lin S.-z.; You T.-p. Synthesis of 9,9′-biphenanthryl-10,10′-bis(oxazoline)s and their preliminary evaluations in the Friedel-Crafts alkylations of indoles with nitroalkenes. Tetrahedron 2009, 65, 1010–1016. 10.1016/j.tet.2008.11.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; l Yuan Z.-L.; Lei Z.-Y.; Shi M. BINAM and H8-BINAM-based chiral imines and Zn(OTf)2-catalyzed enantioselective Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with nitroalkenes. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry 2008, 19, 1339–1346. 10.1016/j.tetasy.2008.04.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; m Liu H.; Lu S.-F.; Xu J.; Du D.-M. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Electron-Rich N-Heterocycles with Nitroalkenes Catalyzed by Diphenylamine-Tethered Bis(oxazoline) and Bis(thiazoline) ZnII Complexes. Chem. Asian J. 2008, 3, 1111–1121. 10.1002/asia.200800071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Lu S.-F.; Du D.-M.; Xu J. Enantioselective Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles with Nitroalkenes Catalyzed by Bifunctional Tridentate Bis(oxazoline)-Zn(II) Complex. Org. Lett. 2006, 8, 2115–2118. 10.1021/ol060586f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Jia Y.-X.; Zhu S.-F.; Yang Y.; Zhou Q.-L. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylations of Indoles with Nitroalkenes Catalyzed by Zn(II)-Bisoxazoline Complexes. J. Org. Chem. 2006, 71, 75–80. 10.1021/jo0516537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Arai T.; Tsuchida A.; Miyazaki T.; Awata A. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Chiral 2-Vinylindole Scaffolds by Friedel-Crafts Reaction. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 758–761. 10.1021/acs.orglett.6b03584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wu H.; Liu R. R.; Jia Y.-X. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation Reaction in the Construction of Trifluoromethylated All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenters. Synlett 2014, 25, 457–460. 10.1055/s-0033-1340318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Weng J.-Q.; Deng Q.-M.; Wu L.; Xu K.; Wu H.; Liu R.-R.; Gao J.-R.; Jia Y.-X. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of α-Substituted β-Nitroacrylates: Access to β2,2-Amino Acids Bearing Indolic All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenters. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 776–779. 10.1021/ol403480v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gao J.-R.; Wu H.; Xiang B.; Yu W.-B.; Han L.; Jia Y.-X. Highly Enantioselective Construction of Trifluoromethylated All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenters via Nickel-Catalyzed Friedel-Crafts Alkylation Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 2983–2986. 10.1021/ja400650m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hao X.-Q.; Xu Y.-X.; Yang M.-J.; Wang L.; Niu J.-L.; Gong J.-F.; Song M.-P. A Cationic NCN Pincer Platinum(II) Aquo Complex with a Bis(imidazolinyl)phenyl Ligand: Studies toward its Synthesis and Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles with Nitroalkenes. Organometallics 2012, 31, 835–846. 10.1021/om200714z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Wu L.-Y.; Hao X.-Q.; Xu Y.-X.; Jia M.-Q.; Wang Y.-N.; Gong J.-F.; Song M.-P. Chiral NCN Pincer Pt(II) and Pd(II) Complexes with 1,3-Bis(2′-imidazolinyl)benzene: Synthesis via Direct Metalation, Characterization, and Catalytic Activity in the Friedel-Crafts Alkylation Reaction. Organometallics 2009, 28, 3369–3380. 10.1021/om801005j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Drabina P.; Brǒz B.; Padĕlková E.; Sedlák M. Structure and catalytic activity of organopalladium(II) complexes based on 4,5-dihydro-1H-imidazol-5-one derivatives. J. Organomet. Chem. 2011, 696, 971–981. 10.1016/j.jorganchem.2010.10.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scherer A.; Mukherjee T.; Hampel F.; Gladysz J. A. Metal-Templated Hydrogen Bond Donors as “Organocatalysts” for Carbon-Carbon Bond Forming Reactions: Syntheses, Structures, and Reactivities of 2-Guanidinobenzimidazole Cyclopentadienyl Ruthenium Complexes. Organometallics 2014, 33, 6709–6722. 10.1021/om500704u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu W.; Shen X.; Ma Q.; Gong L.; Meggers E. Restricted Conformation of a Hydrogen Bond Mediated Catalyst Enables the Highly Efficient Enantioselective Construction of an All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenter. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 7641–7646. 10.1021/acscatal.6b02080. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Huang K.; Ma Q.; Shen X.; Gong L.; Meggers E. Metal-Templated Asymmetric Catalysis: (Z)-1-Bromo-1-Nitrostyrenes as Versatile Substrates for Friedel-Crafts Alkylation of Indoles. Asian J. Org. Chem. 2016, 5, 1198–1203. 10.1002/ajoc.201600288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Liu J.; Gong L.; Meggers E. Asymmetric Friedel-Crafts alkylation of indoles with 2-nitro-3-arylacrylates catalyzed by a metal-templated hydrogen bonding catalyst. Tetrahedron Lett 2015, 56, 4653–4656. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2015.06.046. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Chen L.-A.; Tang X.; Xi J.; Xu W.; Gong L.; Meggers E. Chiral-at-Metal Octahedral Iridium Catalyst for the Asymmetric Construction of an All-Carbon Quaternary Stereocenter. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 14021–14025. 10.1002/anie.201306997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Carmona D.; Lamata M. P.; Viguri F.; Rodríguez R.; Oro L. A.; Balana A. I.; Lahoz F. J.; Tejero T.; Merino P.; Franco S.; Montesa I. The Complete Characterization of a Rhodium Lewis Acid-Dipolarophile Complex as an Intermediate for the Enantioselective Catalytic 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of C,N-Diphenylnitrone to Methacrolein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 2716–2717. 10.1021/ja031995z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carmona D.; Lamata M. P.; Viguri F.; Rodríguez R.; Oro L. A.; Lahoz F. J.; Balana A. I.; Tejero T.; Merino P. Enantioselective 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition of Nitrones to Methacrolein Catalyzed by (η5-C5Me5)M{(R)-Prophos} Containing Complexes (M = Rh, Ir; (R)-Prophos = 1,2-bis(Diphenylphosphino)propane): On the Origin of the Enantioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 13386–13398. 10.1021/ja0539443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Carmona D.; Méndez I.; Rodríguez R.; Lahoz F. J.; García-Orduña P.; Oro L. A. Metal-Nitroalkene and aci-Nitro Intermediates in Catalytic Enantioselective Friedel-Crafts Reactions of Indoles with trans-β-Nitrostyrenes. Organometallics 2014, 33, 443–446. 10.1021/om401125q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Méndez I.; Rodríguez R.; Polo V.; Passarelli V.; Lahoz F. J.; García-Orduña P.; Carmona D. Temperature Dual Enantioselective Control in a Rhodium-Catalyzed Michael-Type Friedel-Crafts Reaction: A Mechanistic Explanation. Chem. - Eur. J. 2016, 22, 11064–11083. 10.1002/chem.201601301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona D.; Lahoz F. J.; Oro L. A.; Lamata M. P.; Viguri F.; San José E. Synthesis, Separation, and Stereochemical Studies of Chiral-at-Metal Rhodium(III) Complexes. Crystal Structure of (SRh,RC)-[(η5-C5Me5)RhCl{Ph2PCH(CH3)CH2PPh2}][BF4]. Organometallics 1996, 15, 2961–2966. 10.1021/om960134e. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Cahn R. S.; Ingold C.; Prelog V. Specification of Molecular Chirality. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1966, 5, 385–415. 10.1002/anie.196603851. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Prelog V.; Helmchen G. Basic Principles of the CIP-System and Proposals for a Revision. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1982, 21, 567–583. 10.1002/anie.198205671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Lecomte C.; Dusausoy Y.; Protas J.; Tirouflet J.; Dormond A. Structure crystalline et configuration relative d’un complexe du titanocene presentant une chiralite plane et une chiralite centree sur l’atome de titane. J. Organomet. Chem. 1974, 73, 67–76. 10.1016/S0022-328X(00)80382-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cremer D.; Pople J. A. General definition of ring puckering coordinates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1975, 97, 1354–1358. 10.1021/ja00839a011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona D.; Viguri F.; Asenjo A.; Lahoz F. J.; Oro L. A. Enantioselective Catalytic Diels-Alder Reactions with Enones as Dienophiles. Organometallics 2012, 31, 4551–4557. 10.1021/om300346s. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carmona M.; Rodríguez R.; Passarelli V.; Carmona D. Mechanism of the Alkylation of indoles with Nitrostyrenes Catalyzed by Chiral-at-Metal Complexes. Organometallics 2019, 38, 988–995. 10.1021/acs.organomet.8b00925. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For the complete spectroscopic characterization of compounds 5, 6, and 7, see Experimental Section.

- SAINT+, version 6.01; Area-Detector Integration Software: Bruker AXS, Madison, 2001.

- a Sheldrick G. M. Phase annealing in SHELX-90: direct methods for larger structures. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 1990, 46, 467–473. 10.1107/S0108767390000277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sheldrick G. M. A short history of SHELX. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. 10.1107/S0108767307043930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Struct. Chem. 2015, 71, 3–8. 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia L. J. WinGX and ORTEP for Windows: an update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012, 45, 849–854. 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.