Abstract

An efficient brucite@zinc borate (3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O) composite flame retardant (CFR), consisting of an incorporated nanostructure, is designed and synthesized via a simple and facile electrostatic adsorption route. It has been demonstrated that this incorporated system can enhance the interfacial interaction and improve the mechanical properties when used in ethylene–vinyl acetate (EVA) composites. Meanwhile, in the process of burning, the CFR particles can successively migrate and accumulate to the surface of the burning zone, increasing the local concentration and rapidly generating a compact barrier layer through a condensed phase reinforcement mechanism even at a lower loading value. Especially, compared with the EVA/physical mixture (PM, with the same proportion of brucite and zinc borate), the heat release rate (HRR), the peak of the heat release rate (PHRR), the total heat released (THR), the smoke production rate (SPR), and mass loss are considerably reduced. According to this study, controlling the nanostructure of flame-retardant particles, to improve the condensed phase char layer, gives a new approach for the design of green flame retardants.

Introduction

In the last few decades, polymer materials have been widely used in the modern society due to their excellent properties and abundant product forms.1−6 However, high flammability is always a general shortcoming of these materials.7−11 To solve this problem, various flame retardants (FRs) were introduced into the polymer matrix.12−19 As important halogen-free flame retardants, mineral fillers, such as magnesium hydroxide or brucite, have attracted considerable attention due to their excellent nontoxic nature and smoke-suppressing properties.20,21 The working mechanism of brucite can be described as a condensed phase effect,22 including endothermic dehydration and formation of the protective carbon layer,23 which retards or terminates thermal degradation of the polymer to suspend the combustion in the condensed phase. Unfortunately, this approach is normally inefficient. The reason is mainly owing to strength reduction of the char layer, which primarily consists of magnesium oxide particles and is easy to break under pushing of flammable gas “bubbles”.23 Even though the heat absorption through endothermic dehydration of brucite can delay the thermal degradation of the polymer to some extent, it can do little because the heat absorption rate is much lower than the heat release rate (HRR) of polymer combustion.24 Consequently, both lead to high heat release and the polymer matrix eventually completes combustion.25,26 Thus, to fulfill an expected flame-retarding efficiency, a high loading amount (commonly up to more than 60 wt %) is necessary.17,27−29 Moreover, it is extremely harmful to the mechanical properties of polymer composites, which limit the application fields.30−34

To solve this problem, great efforts have been devoted to enhancing the flame retardancy of the condensed phase effect by incorporating magnesium hydroxide or brucite with synergistic additives, such as zinc borate (ZB).35−38 Zinc borate (ZB) is also a kind of halogen-free mineral filler, and previous works demonstrated that some kinds of zinc borate particles migrated and aggregated in the polymer melt and then changed into a glassy cage for polymer chains as a physical barrier, reinforcing the char layer in the condensed phase.35,36,39−41 However, these approaches are based on simple physical mixing of zinc borate and magnesium hydroxide. During polymer burning, filler particles including zinc borate and magnesium hydroxide would assemble and decompose respectively to form a hollow structure in the polymer matrix, resulting in strength reduction and collapse of the char layer. Namely, this synergistic method is isolated and weak, which has to maintain a high loading level to meet the flame-retardant requirement.42 Hereby, one potential strategy to conquer this problem is to reinforce the condensed phase structure through conducting migration of flame-retardant particles in the polymer melt, even at a lower loading. To the best of our knowledge, no work has been reported on designing a special incorporated structure of brucite@zinc borate flame-retardant particles, to improve and reinforce the condensed phase residue layer by conducting the migration and local accumulation of the particles to the burning surface zone.

In our previous work,23 we found that the core/shell-structured brucite@Zn6O(OH)(BO3)3 could enhance the flame-retarding efficiency. The surface Zn6O(OH)(BO3)3 acted as a stabilizer to improve the internal char structure in situ. These results inspired us to investigate whether it is possible to further improve the flame-retarding efficiency by conducting particle migration. Considering the low transition temperature and good migratory behavior of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O (a kind of zinc borate),43 in this paper, we attempt to synthesize 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O nanosheets on the surface of brucite via a simple and facile electrostatic adsorption method, fabricating incorporated brucite@3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O particles for great enhancement of the flame-retarding efficiency in polymers (here we chose the ethylene–vinyl acetate copolymer, EVA). In comparison with the simple physical mixture (PM) in EVA, these combined particles can uniformly migrate and accumulate to the combustion zone, resulting in an insulation layer rapidly and presenting the remarkable performance of flame retardancy even at a lower loading level. Meanwhile, the morphologies and structures of surface zinc borate can be controlled to maintain the mechanical properties when used in EVA composites. The first part of this paper concerned the evaluation of the brucite@zinc borate composite flame-retardant (CFR) particles and the mechanical properties in EVA. In the second part, the study focused on the flame-retardant performance of brucite@zinc borate particles for a reasonably enhanced condensed phase mechanism.

Results and Discussion

Chemical Compositions and Structural Characterization

The typical morphologies and structures of as-prepared particles were examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) shown in Figure 1. These images show that the zinc borate (ZB) particles are irregular nanoflakes with a nanometer-sized diameter (Figure 1b,f,j). In the high-magnification view, numerous particles with a nanometer-sized diameter are implanted on the surface of brucite (Figure 1d), which is distinct from PM (Figure 1c). Moreover, the high-magnification TEM image (Figure 1l) further displays that brucite was well coated by nanoflakes to form an obvious incorporated nanostructure. In contrast, raw brucite particles are angular with a relatively smooth surface (Figure 1i) owing to layer exfoliation. In addition, the low-magnification view of the CFR (Figure 1h) displays the same particle size and distribution as brucite particles (Figure 1e), and the average diameter of the CFR is 7.22 μm (Figure S1).

Figure 1.

SEM images of the (a) high- and (e) low-magnification views of the brucite particles, (b) high- and (f) low-magnification views of the as-prepared zinc borate particles, (c) high- and (g) low-magnification views of the physical mixture (PM), (d) high- and (h) low-magnification views of the brucire@zinc borate composite flame retardant (CFR). TEM images of (i) brucite particles, (j) zinc borate particles, (k) PM particles, and (l) a single CFR particle.

To further identify the chemical composition of these particles, the powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of brucite, zinc borate, and CFR were measured and are shown in Figure 2. It can be seen that the CFR particles present characteristic reflections of both brucite and 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O phases, and the diffraction peaks are in good agreement with JCPDS files No. 44-1482 and 35-0433, respectively. Interestingly, it is noted that the characteristic reflections of CFR are slightly weakened compared to those in brucite or PM phases, resulting from the shielding of the surface 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O nanosheet coverage corresponding to the TEM analysis.

Figure 2.

XRD patterns of (a) brucite, (b) zinc borate, (c) PM, and (d) CFR.

Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves are shown in Figure 3. The thermal decomposition of the CFR mainly takes place in two weight loss steps due to a similar decomposition temperature to zinc borate and brucite. The first decomposition step (332–425 °C) corresponds to the dehydration of Mg(OH)2 and the transformation from zinc borate into ZnO and B2O3, which occurs at a higher temperature than either the PM (298–413 °C) or raw brucite (298–409 °C). In addition, the CFR presents a higher initial decomposition temperature at 332 °C, which was 42 °C higher than that of the PM. Consistently, the derivative weight peak of the CFR appears at 398 °C, which is 7 °C higher than that of the PM. In other words, the CFR presents higher thermal stability, which might be attributed to the interface dehydration of hydroxyl groups between brucite and 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O to form chemical bonding. Moreover, the latter Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) analysis gives more information about this inference. Consequently, the final residue of the CFR is 72.05 wt % at 800 °C, which is higher than any other formulations, related to the enhancement of thermal stability. Indeed, it is worth noting that the chemical bonding through dehydration can prevent the two brucite and zinc borate phases from separating during burning conditions.

Figure 3.

TGA/derivative thermogravimetric (DTG) curves of (a) pristine brucite, (b) zinc borate, (c) PM, and (d) CFR.

FTIR spectra give direct evidence of this interface dehydration assumption shown in Figure 4. The brucite exhibits a strong absorbance peak at 3694 cm–1 and 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O presents an absorption peak at 3478 cm–1, corresponding to the stretching vibration bands for the free hydroxyl groups. Indeed, these are the essential conditions for interface dehydration. In comparison with that of PM, it is observed that these absorbances of the CFR decrease in intensity. Besides, owing to chemisorbed CO2 on the surface, the brucite presents a stretching vibration band of C–O–Mg at 1439 cm–1 (Figure 4a). Interestingly, this absorption shifted to 1423 and 1483 cm–1 (Figure 4d), suggesting interface dehydration between the hydroxyl groups.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of (a) pristine brucite, (b) 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O, (c) PM, and (d) CFR.

Mechanical Properties and Interfacial Interaction

Although all of the filler particles have similar size distributions, the microstructures are quite different (Figure 1). When used in EVA composites, these differences bring great impacts on the mechanical properties including tensile strength (TS) and elongation at break (EAB) shown in Figure 5. As for all of the samples, it is found that both the TS and EAB rapidly decreased with increasing filler contents owing to the poor compatibility between filler particles and the EVA matrix. Even so, a dramatic increase in TS can be observed for the EVA/CFR formulation with any loading amount, almost reaching a 50% increment in comparison with EVA/brucite and EVA/PM blends. The reason for this phenomenon is that the surface nanoflakes of the CFR can easily embed into the EVA matrix, bringing more interface contact areas and providing polydirectional internal stress transfer. The EVA/ZB presents an obvious increase in EAB owing to the nanometer size effect. Concurrently, EVA/CFR formulation also shows an increase in EAB, resulting from multiple orientations of surface nanosheets, which can prevent the microcracks from propagating at the interface during extension. In other words, this incorporated nanostructure improves the compatibility between inorganic filler particles and the polymer matrix.

Figure 5.

Mechanical properties of (a) EVA/brucite, (b) EVA/ZB, (c) EVA/PM, and (d) EVA/CFR formulations.

To further elucidate the contact status between filler particles and the EVA matrix, the cross-sections of the four blends were examined by SEM shown in Figure 6. It can be seen that the morphologies of cross-sections are quite different. The cross-sections of EVA/ZB and EVA/CFR present relatively smooth surfaces and no obvious aggregates (Figure 6b,d). The ZB and CFR particles seem to be embedded into the EVA matrix and the dispersion is significantly improved, while EVA/brucite and EVA/PM display different morphologies that the added filler particles tend to agglomerate (Figure 6a,c) and are detrimental to the mechanical properties. Namely, there is better compatibility between ZB nanosheets in a regular shape and the EVA matrix, even the surface ZB nanosheet coating of the CFR particles. As a result, the EVA/CFR formulation exhibits superior mechanical properties (Figure 5).

Figure 6.

SEM images of freeze-fractured sections of (a) EVA/brucite, (b) EVA/ZB, (c) EVA/PM, and (d) EVA/CFR. The loading amounts of FR particles were all kept constant at 40 wt %.

Thermal Analysis

To explore the effect of flame retardants on the decomposition behavior of EVA composites, TGA/DTG was carried out under nitrogen conditions. EVA/brucite (A2), EVA/ZB (A3), EVA/PM (A4), and EVA/CFR (A5) formulations with an equivalent content of 40 wt % fillers, and pure EVA (A1) was taken into account. As seen in Figure 7, all of these degradation curves included two steps. The first steps in the temperature range of 300–400 °C can be attributed to the degradation of fillers and loss of acetic acid in EVA, whereas the second steps that occur between 400 and 520 °C are considered to the degradation of ethylene-based chains and volatilization of the residual polymer.44,45 Meanwhile, the derivative weight peak of the CFR (A5) appears near 355 °C, which is 10 and 13 °C higher than those of the PM (A4) and brucite (A2), respectively. Additionally, sample A5 exhibits the lower maximum weight loss rate of 3.01 wt %/min at 355 °C compared with A2 and A4, and its final residue is 34.61 wt % at 800 °C, which is higher than any other blends. All of these results mean that the CFR can effectively delay the thermal degradation and bring higher thermal stability in EVA.

Figure 7.

TGA/DTG curves for A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5.

Flammability of the EVA/FR Composites

The flame retardance of the EVA composites was accessed by the limiting oxygen index (LOI) and UL94 tests, listed in Table 1. When the EVA is mixed with any flame retardant, positive results are obtained, especially in the LOI. It is observed that the EVA/CFR formulation displays the highest LOI values at the equivalent filling amount. Moreover, only the EVA/CFR formulation could pass a vertical UL94 V-0 rating. The best self-extinguishing ability of the EVA/CFR formulation can be ascribed to the incorporated nanostructure of the CFR.

Table 1. LOI and UL94 Tests of EVA Formulations.

| composition (wt %) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sample formation | EVA | FR | LOI | UL94 |

| virgin EVA | 100 | 0 | 17 | fail |

| EVA/brucite | 60 | 40 | 23 | fail |

| 50 | 50 | 27.5 | fail | |

| EVA/ZB | 60 | 40 | 21 | fail |

| 50 | 50 | 25 | fail | |

| EVA/PM | 60 | 40 | 29 | fail |

| 50 | 50 | 32 | fail | |

| EVA/CFR | 60 | 40 | 30 | V-1 |

| 50 | 50 | 34 | V-0 | |

To study the effect of flame retardants on the burning behaviors in EVA, a cone calorimeter test was conducted. With the equivalent filling amount of 40 wt %, the detailed results of the heat release rate (HRR), the total heat released (THR), the smoke production rate (SPR), and mass loss were examined and are shown in Figure 8. From Figure 8a, it can be seen that EVA (A1) is considerably flammable with a peak of heat release rate (PHRR) of 876 kW/m2. After complete combustion, EVA reaches a THR of 148 MJ/m2 (Figure 8b) with almost no residue left finally (2 wt %). As for EVA/brucite (A2), two obvious HRR peaks at 305 and 343 kW/m2 are observed in the range of 190–600 s, which are in accordance with the endothermic decomposition of brucite to MgO, forming a thin and fragile MgO char layer with large holes and cracks on the char surface (Figure 9a). During the period of combustion, this crisp structure almost collapsed (Figure 9d,g) resulting in the promotion of heat radiation and gaseous phase transfer. Indeed, the second PHRR comes from the sufficient contract between oxygen rushing through the collapsed structure and combustion gases stored under the protective layer, which leads to explosive combustion and an enhanced HRR. As for sample EVA/PM (A4), an inconspicuous decrease in the PHRR with 271 to 323 kW/m2 (Figure 8a) is observed, and the THR is also close to that of A2. This implies that the PM displays no more obvious effect than an individual brucite. More importantly, these results indicate that a simple physical mixture of brucite and zinc borate has no distinct synergy and cannot effectively enhance the flame retardancy. In fact, there is an unstable and brittle protective layer which cannot prevent the transfer of heat and circulation of gases in burning (Figures 9b and 10e,h). Interestingly, the peak intensities of EVA/CFR (A5) are apparently much lower than any other samples. It can be seen that sample A5 presents a dramatic decline in HRR intensities, which was much lower than that of sample A4. In addition, the dynamic curves of the THR (Figure 8b) show that the THR of A5 is the lowest among the five samples and its total burning time is also prolonged. These imply that the incorporated nanostructure of the CFR plays a major role in the combustion stage, greatly reinforcing condense phase flame retardancy. Furthermore, A5 displays the lowest mass loss (Figure 8c), indicating that the combined structure of the CFR has some benefit of increasing the char residue, even better than EVA/ZB. After complete combustion in cone calorimetry, the final mass loss of sample A5 was 39.1 wt %. In contrast, the amounts of samples A2, A3, and A4 were 31.77, 36.16, and 33.97 wt %, respectively. It can be concluded that residue A5 apparently demonstrates an insulating layer effect.

Figure 8.

(a) HRR, (b) THR, (c) mass loss, and (d) SPR against time curves for A1, A2, A3, A4, and A5.

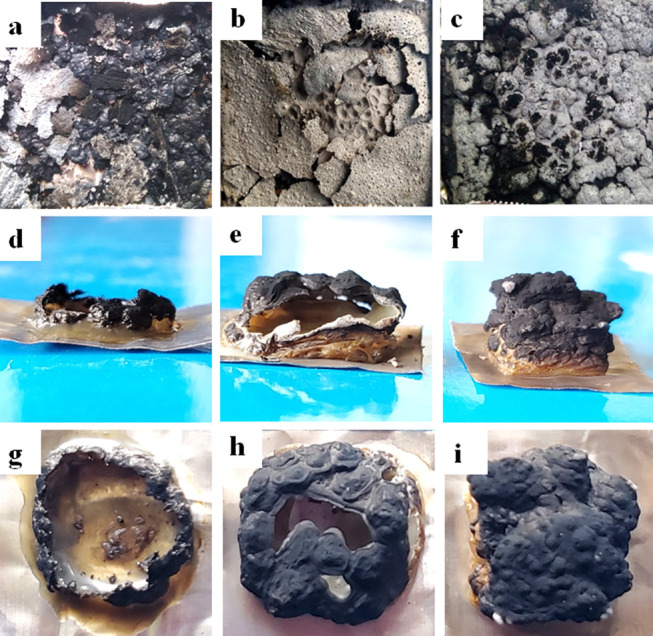

Figure 9.

Digital photographs of EVA composites: (a) A2, (b) A4, and (c) A5 after the CONE test; (d, g) A2, (e, h) A4, and (f, i) A5 after complete combustion in air.

Figure 10.

XRD patterns of surface and inner char residues: (a, e) A2, (b, f) A3, (c, g) A4, and (d, h) A5.

The most significant property of the brucite flame retardant is smoke suppression owing to the formation of active MgO layers in fire.46,47 The dynamic SPR curves show that the peak SPR value of sample A5 is considerably reduced compared to that of other samples, which implies that the zinc borate coating in the CFR is beneficial to prevent active MgO from agglomerating during burning. This improves the dispersion of active MgO, absorbing more smoke. Apparently, the above results further demonstrated that this integrated structure of CFR particles causes a strong impact on flame retardancy and smoke suppression during EVA burning.

Morphological and Chemical Analyses of Residues

To elucidate how the formation of condensed phase chars affects the combustion process of EVA composites, the residues obtained after cone calorimeter tests and complete combustion in air were examined in char appearance. Figure 9 shows the digital pictures of residues for EVA/brucite (A2), EVA/PM (A4), and EVA/CFR (A5) composites. It is obvious that the EVA/CFR formulation formed homogeneous and coherent char structures with no visible holes on the surface after burning (Figure 9c,f,i), and the residual char is compact and rigid enough to prevent gas permeation and hinder heat transmission, which is the main reason for the significant HRR decrease. Nevertheless, the residue chars of EVA/brucite and EVA/PM display different morphologies. Both of them internally collapsed to hollow structures. Especially, the EVA/brucite residual char aggregated together to the edge (Figure 9a,d,g). Moreover, there is also a thin and brittle layer on the surface of the EVA/PM residual char, which can easily collapse inward and burst into flame, corresponding to the second PHRR in Figure 8a.

The reason for the enhancement was further explained by the char residue XRD and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) analyses. The typical XRD patterns of surface and inner char residues for A2, A3, A4, and A5 are shown in Figure 10. It can be found that the surface char layer of A3 (Figure 10b) presents only characteristic peaks of Zn(BO2)2 corresponding to JCPDS 39-1126. In contrast, its inner residue shows no diffraction peak (Figure 10f). This is attributed to the surface migration of thermal decomposition products of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O. In addition, as for sample A2 (Figure 10a,e), all diffraction peaks, either surface or inner char, are indexed as MgO with the lattice constants comparable to the values of JCPDS 45-0946. It implies that MgO, derived from the thermal decomposition of brucite, is evenly distributed over the whole residual char. Coincidentally, sample A4 (Figure 10c,g) presents similar MgO distributions, indicating no obvious synergistic action between brucite and zinc borate. However, from sample A5, it is noted that the peak intensities of surface MgO (Figure 10d) are obviously higher than those of inner MgO (Figure 10g), verifying the surface migration of CFR particles. Moreover, the EDS spectra of the surface char residues after the CONE test give more direct evidence of this migration. As shown in Figure 11, it can be observed that the surface char residue of EVA/CFR (A5) presents a higher content of Mg element, whereas EVA/PM (A4) shows higher contents of Zn element. In addition, A series of little diffraction peaks from 30 to 40° can be observed, which are attributed to the interaction between MgO and Zn(BO2)2.48 These can be beneficial to the quality of the residual char layer in the condensed phase. Especially, these reflections disappeared in the inner char layer of A4, indicating that brucite and zinc borate in the PM assemble separately during combustion. All of these results can be concluded that CFR particles migrated and accumulated near the surface to act as a thermal insulation layer.

Figure 11.

EDS spectrum of the surface char residue after the CONE test.

Flame-Retardant Mechanism

The detailed mechanism of the surface migration and enhanced flame resistance is proposed as shown in Figure 12. The EVA/CFR formulation provides a condensed phase reinforcement mechanism in flame retardancy, by the formation of a barrier layer. At the beginning of the EVA composite burning, the temperature continues to rise, and the EVA matrix begins to melt and burn. Subsequently, the CFR particles successively migrate to the surface of the burning zone. The concentration of particles on the surface increases in a short time. With the thermal decomposition of CFR particles, several glassy foams blow and cover the surface burning area. Moreover, the surface net concentration of the glassy foams further increased along with the particle migration. In this case, the total 16.7 wt % content of zinc borate can lead to rapid charring of EVA chains from the surface to the inside, finally resulting in a compact barrier layer consisting of many interconnected protuberances (Figure 9c,f,i). Apparently, this thermal insulation layer can retard the external heat radiation from the burning area to the undegraded EVA and prevent contact between combustible gases and external oxygen. Both can reduce EVA pyrolysis and the combustible gases release. The thicker the insulation layer grows, the harder the combustion maintains.

Figure 12.

Schematic illustration of the mechanism for the enhanced flame resistance.

Conclusions

In this work, a brucite@zinc borate composite flame retardant (CFR) was synthesized via a simple and facile electrostatic adsorption process. The obtained CFR particles are confirmed by XRD, FTIR, TG, SEM, and TEM. All of the results indicate that zinc borate (3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O) nanoflakes are implanted into the surface of brucite to form an obvious incorporated nanostructure. Compared with the simple physical mixture (PM), the brucite@zinc borate-incorporated nanostructure can enhance the interfacial interaction and improve the mechanical properties when used in EVA. More importantly, even at a lower loading value of 40 wt %, its flame retardancy is significantly increased through a condensed phase reinforcement mechanism by CFR particle surface migration. These results indicate that controlling the nanostructure of flame-retardant particles, to improve the condensed phase barrier layer, gives a new approach for the design of green flame retardants.

Experimental Section

Materials

Brucite powder (2500 mesh) was supplied by Sino Minmetals (China). It contains more than 90 wt % of magnesium hydroxide, and the chemical components are listed in Table 2. Zinc oxide (ZnO, analytical grade), boric acid (H3BO3, analytical grade), and sodium hydroxide (NaOH, analytical grade) were purchased from Xilong Chemical Co., Ltd. (China). The ethylene–vinyl acetate copolymer (TAISOX 7350 M, 18 wt % of vinyl acetate) was supplied as pellets by Formosa Plastics Corporation, and its melt index is 2.5 dg/min at 190 °C and 2.16 kg load. All of these materials were used as received without any further purification.

Table 2. Chemical Components of Brucite Powder.

| Mg(OH)2 (wt %) | SiO2 (wt %) | CaO (wt %) | Fe2O3 (wt %) | Al2O3 (wt %) | insoluble residues (wt %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90.11 | 4.39 | 3.03 | 0.41 | 0.13 | <1.93 |

Preparation of Zinc Borate

Zinc borate (3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O) nanoflakes were obtained according to a controllable solid–liquid process. In a typical procedure for synthesis, 22.26 g (0.36 mol) of boric acid (H3BO3) and 4.88 g (0.06 mol) of zinc oxide were mixed in 50 mL of distilled water and the obtained slurry was heated to reflux for 2 h with vigorous stirring. Then, the white suspension was immediately filtered, washed repeatedly with deionized water, and finally dried in the oven at 90 °C for 12 h, yielding a loose 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O powder.

Preparation of Brucite@Zinc Borate Composite Fame Retardant Particles

The brucite@zinc borate composite flame-retardant (CFR) particles were obtained through a potential adsorption process, illustrated in Figure 13. In detail, 70 g of brucite was suspended in 400 mL of deionized water and the slurry was heated at 95 °C for 2 h. Then, the as-prepared 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O nanoflakes were added into the slurry rapidly. After 10 min, 4 mol/L NaOH solution was used to adjust the pH value of 10.5–11.0, to change the ζ potential of the two particles (ζ potential investigations of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O and brucite are shown in Figure S2). Vigorous stirring was applied during the whole procedure for 6 h, until the 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O nanoflakes were firmly incorporated on the brucite surface under electrostatic attraction. Finally, the residues were filtered and dried in oven at 90 °C for 24 h, yielding a loosened white powder. The weight content of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O was 16.7 wt % (measured by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) elemental analysis).

Figure 13.

Schematic illustration of the synthesis of brucite@zinc borate composite flame-retardant (CFR) particles.

Preparation of the Physical Mixture

The physical mixture was prepared by mixing brucite and zinc borate (3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O) with a high-speed mixer at room temperature. For comparison, zinc borate was prepared using a similar synthesis process to that of the CFR in the absence of brucite and the weight content of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O in the mixture is 16.7 wt %, similar to that in the CFR.

Preparation of EVA/Flame-Retardant Composites

To ensure the same dispersion degree of all of the flame-retardant (FR) particles in the EVA matrix, surface treatment was carried out. All of the FR particles (30% weight ratio to ethanol) were added into ethanol (containing 4 wt % of water). Subsequently, the mixture was heated in a water bath for 1 h. Then, γ-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (AMEO) (3% weight ratio to FR) was fed into the reaction system, with vigorous stirring and refluxing for 2 h. The product was collected and washed with absolute ethyl alcohol several times and then dried in a vacuum system at 50 °C for 24 h for subsequent blending.

The EVA/FR composites were prepared by melt mixing at 135 °C in an open mill for 15 min. Thereafter, sheets with 4, 3, and 1 mm thickness were obtained by compression molding under a pressure of 10 MPa at 130 °C for 30 min, respectively. The content of FR additives was varied from 0 to 60 wt %.

Characterization of the Samples

The particle morphology was examined under cold-field scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-7500F) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEM-2100). The crystallinity and the composition of the powder were analyzed by X-ray diffraction (XRD) (Holland PANalytical company, Cu Kα radiation, at 2θ values ranging from 5 to 80°) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDS) (JEOL JSM-7500F).

Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out using a Mettler-Toledo TGA/SDTA 851e thermal analyzer in a static atmosphere from room temperature to 800 °C with a heating rate of 10 °C/min. The FTIR spectra were recorded in the range of 400–4000 cm–1 on a Thermo Nicolet 5700 FTIR instrument using the KBr disc method.

The freeze-fractured cross-sections of blends were obtained by liquid nitrogen (−196 °C) quenching. Moreover, the images were observed by a SEM after coating with a thin gold layer deposited by sputtering under vacuum.

Tensile tests were evaluated by a JSL-5000N testing machine (Yangzhou Jingyi Test Machine Co., Ltd., China) in accordance with ASTM D68-14 at room temperature and a tensile strain rate of 200 mm/min. At least ten parallel tests were conducted to obtain the average values.

Flammability Tests of EVA/FR Composites

The limiting oxygen index (LOI, Standard Test Method for measuring the minimum oxygen concentration to support candle-like downward flame combustion) was detected using an HC-2C digital oxygen index type instrument (Nanjing Shangyuan Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd.) on the specimens of 120 × 6.5 × 3 mm3 according to GB/T 2406-2008. UL94 classification was carried out using a CZF-4 horizontal vertical burning type instrument (Nanjing Shangyuan Analytical Instrument Co., Ltd) on the specimens of 127 × 12.7 × 3 mm3 according to GB/T 2408-2008.

The forced flaming behaviors were evaluated on a cone calorimeter device (Fire Testing Technology, East Grinstead, U.K.) under 35 kW/m2 external radiant heat flux conforming to ISO 5660, and the samples with the dimensions of 100 × 100 × 4 mm3 were used.

Acknowledgments

X.W. and other authors are grateful for the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21706033).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c03916.

Particle size and distribution of CFR particles (Figure S1); ζ potential investigations of 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O and brucite (Figure S2) (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Ekladious I.; Colson Y. L.; Grinstaff M. W. Polymer-drug conjugate therapeutics: advances, insights and prospects. Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery 2019, 18, 273–294. 10.1038/s41573-018-0005-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidal F.; Jakle F. Functional Polymeric Materials Based on Main-Group Elements. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 5846–5870. 10.1002/anie.201810611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T.; Kim J. H.; Kang T. E.; Lee C.; Kang H.; Shin M.; Wang C.; Ma B. W.; Jeong U.; Kim T. S.; Kim B. J. Flexible, highly efficient all-polymer solar cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 8547 10.1038/ncomms9547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B. Q. Y.; Low Z. W. K.; Heng S. J. W.; Chan S. Y.; Owh C.; Loh X. J. Recent Advances in Shape Memory Soft Materials for Biomedical Applications. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 10070–10087. 10.1021/acsami.6b01295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroon R.; Mengistie D. A.; Kiefer D.; Hynynen J.; Ryan J. D.; Yu L. Y.; Muller C. Thermoelectric plastics: from design to synthesis, processing and structure-property relationships. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 6147–6164. 10.1039/C6CS00149A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peplow M. FANTASTIC PLASTICS. Nature 2016, 536, 266–268. 10.1038/536266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deans T.; Schiraldi D. A. Flammability of polyesters. Polymer 2014, 55, 2825–2830. 10.1016/j.polymer.2014.04.050. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon R. E.; Takemori M. T.; Safronava N.; Stoliarov S. I.; Walters R. N. A molecular basis for polymer flammability. Polymer 2009, 50, 2608–2617. 10.1016/j.polymer.2009.03.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman J. W.; Jackson C. L.; Morgan A. B.; Harris R.; Manias E.; Giannelis E. P.; Wuthenow M.; Hilton D.; Phillips S. H. Flammability properties of polymer-Layered-silicate nanocomposites. Polypropylene and polystyrene nanocomposites. Chem. Mater. 2000, 12, 1866–1873. 10.1021/cm0001760. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q.; Jin C.; Jiang Y. Compare the flammability of two extruded polystyrene foams with micro-scale combustion calorimeter and cone calorimeter tests. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2017, 127, 2359–2366. 10.1007/s10973-016-5754-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. C.; Kim Y. S.; Shields J.; Davis R. Controlling polyurethane foam flammability and mechanical behaviour by tailoring the composition of clay-based multilayer nanocoatings. J. Mater. Chem. A 2013, 1, 12987–12997. 10.1039/c3ta11936j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman D. Review Polymer Nanocomposites: Flammability. J. Macromol. Sci., Part A 2013, 50, 1241–1249. 10.1080/10601325.2013.843407. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanu L. G.; Simon G. P.; Cheng Y. B. Thermal stability and flammability of silicone polymer composites. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2006, 91, 1373–1379. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2005.07.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song P. A.; Yu Y. M.; Zhang T.; Fu S. Y.; Fang Z. P.; Wu Q. Permeability, Viscoelasticity, and Flammability Performances and Their Relationship to Polymer Nanocomposites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 7255–7263. 10.1021/ie300311a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laoutid F.; Bonnaud L.; Alexandre M.; Lopez-Cuesta J. M.; Dubois P. New prospects in flame retardant polymer materials: From fundamentals to nanocomposites. Mater. Sci. Eng., R 2009, 63, 100–125. 10.1016/j.mser.2008.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H. L.; Zhang S. M.; Zhao C. G.; Hu G. J.; Yang M. S. Flame retardant mechanism of polymer/clay nanocomposites based on polypropylene. Polymer 2005, 46, 8386–8395. 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham A. L.; Lomeda J. R.; Morgan A. B.; Tour J. M. Graphite oxide flame-retardant polymer nanocomposites. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2009, 1, 2256–2261. 10.1021/am900419m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. J.; Shao Z. B.; Wang X. L.; Chen L.; Wang Y. Z. Halogen-Free Flame-Retardant Flexible Polyurethane Foam with a Novel Nitrogen-Phosphorus Flame Retardant. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2012, 51, 9769–9776. 10.1021/ie301004d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cipiriano B. H.; Kashiwagi T.; Raghavan S. R.; Yang Y.; Grulke E. A.; Yamamoto K.; Shields J. R.; Douglas J. F. Effects of aspect ratio of MWNT on the flammability properties of polymer nanocomposites. Polymer 2007, 48, 6086–6096. 10.1016/j.polymer.2007.07.070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L.; Yang X. M.; Peng H.; Wang F.; Liu X.; Yang Y. G.; Hao J. W. Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Multifunctional Flame Retardant Based on Brucite, 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, and Alginate and Its Applications in Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate Resin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 9925–9935. 10.1021/acsami.6b00998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. L.; Li Z. P.; Li Y. Y.; Wang J. Y.; Liu X.; Song T. Y.; Yang X. M.; Hao J. W. Spray-Drying-Assisted Layer-by-Layer Assembly of Alginate, 3-Aminopropyltriethoxysilane, and Magnesium Hydroxide Flame Retardant and Its Catalytic Graphitization in Ethylene-Vinyl Acetate Resin. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 10490–10500. 10.1021/acsami.8b01556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K.; Cao X. J.; Liang Q. S.; Wang H. T.; Cui X. W.; Li Y. J. Formation of a Compact Protective Layer by Magnesium Hydroxide Incorporated with a Small Amount of Intumescent Flame Retardant: New Route to High Performance Nonhalogen Flame Retardant TPV. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 8784–8792. 10.1021/ie5008147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. S.; Pang H. C.; Chen W. D.; Lin Y.; Zong L. S.; Ning G. L. Controllable Fabrication of Zinc Borate Hierarchical Nanostructure on Brucite Surface for Enhanced Mechanical Properties and Flame Retardant Behaviors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 7223–7235. 10.1021/am500380n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil E. D.; Levchik S. V. Flame retardants in commercial use or development for polyolefins. J. Fire Sci. 2008, 26, 5–43. 10.1177/0734904107083309. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mouritz A. P.; Mathys Z.; Gibson A. G. Heat release of polymer composites in fire. Composites, Part A 2006, 37, 1040–1054. 10.1016/j.compositesa.2005.01.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jang B. N.; Costache M.; Wilkie C. A. The relationship between thermal degradation behavior of polymer and the fire retardancy of polymer/clay nanocomposites. Polymer 2005, 46, 10678–10687. 10.1016/j.polymer.2005.08.085. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothon R. N.; Hornsby P. R. Flame retardant effects of magnesium hydroxide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 1996, 54, 383–385. 10.1016/S0141-3910(96)00067-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier F.; Bourbigot S.; Bras M. L.; Delobel R.; Foulon M. Charring of fire retarded ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer-magnesium hydroxide/zinc borate formulations. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2000, 69, 83–92. 10.1016/S0141-3910(00)00044-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gui H.; Zhang X.; Liu Y.; Dong W.; Wang Q.; Gao J.; Song Z.; Lai J.; Qiao J. Effect of dispersion of nano-magnesium hydroxide on the flammability of flame retardant ternary composites. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2007, 67, 974–980. 10.1016/j.compscitech.2006.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sain M.; Park S. H.; Suhara F.; Law S. Flame retardant and mechanical properties of natural fibre-PP composites containing magnesium hydroxide. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 83, 363–367. 10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00280-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z. Z.; Qu B. J. Flammability characterization and synergistic effects of expandable graphite with magnesium hydroxide in halogen-free flame-retardant EVA blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2003, 81, 401–408. 10.1016/S0141-3910(03)00123-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z. Z.; Qu B. J.; Fan W. C.; Huang P. Combustion characteristics of halogen-free flame-retarded polyethylene containing magnesium hydroxide and some synergists. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2001, 81, 206–214. 10.1002/app.1430. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu M. Z.; Qu B. J. Synergistic flame retardant mechanism of fumed silica in ethylene-vinyl acetate/magnesium hydroxide blends. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 85, 633–639. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2004.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hull T. R.; Witkowski A.; Hollingbery L. Fire retardant action of mineral fillers. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2011, 96, 1462–1469. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2011.05.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier F.; Bourbigot S.; Le Bras M.; Delobel R.; Foulon M. Charring of fire retarded ethylene vinyl acetate copolymer - magnesium hydroxide/zinc borate formulations. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2000, 69, 83–92. 10.1016/S0141-3910(00)00044-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabet M.; Hassan A.; Ratnam C. T. Effect of zinc borate on flammability/thermal properties of ethylene vinyl acetate filled with metal hydroxides. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2013, 32, 1122–1128. 10.1177/0731684413494942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sertsova A. A.; Marakulin S. I.; Yurtov E. V. Metal Compound Nanoparticles: Flame Retardants for Polymer Composites. Russ. J. Gen. Chem. 2017, 87, 1395–1402. 10.1134/S1070363217060421. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pang H. C.; Wang X. S.; Zhu X. K.; Tian P.; Ning G. L. Nanoengineering of brucite@SiO2 for enhanced mechanical properties and flame retardant behaviors. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2015, 120, 410–418. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2015.08.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen K. K.; Kochesfahani S.; Jouffret F. Zinc borates as multifunctional polymer additives. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2008, 19, 469–474. 10.1002/pat.1119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li S. L.; Long B. H.; Wang Z. C.; Tian Y. M.; Zheng Y. H.; Zhang Q. Synthesis of hydrophobic zinc borate nanoflakes and its effect on flame retardant properties of polyethylene. J. Solid State Chem. 2010, 183, 957–962. 10.1016/j.jssc.2010.02.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao P. Q.; Song W. H.; Ding F.; Wang X.; Li M. M. Controllable synthesis and flame-retardant properties of spherical zinc borate nanostructure. Micro Nano Lett. 2012, 7, 863–866. 10.1049/mnl.2012.0418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carpentier F.; Bourbigot S.; Le Bras M.; Delobel R. Rheological investigations in fire retardancy: application to ethylene-vinyl-acetate copolymer-magnesium hydroxide/zinc borate formulations. Polym. Int. 2000, 49, 1216–1221. . [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Zhang A. Q.; Liu Z. H. Thermodynamic properties of two zinc borates: 3ZnO·3B2O3·3.5H2O and 6ZnO·5B2O3·3H2O. J. Chem. Thermodyn. 2015, 82, 88–92. 10.1016/j.jct.2014.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H.; Zhang W.; Ryu H. J.; Choi G.; Choi J. Y.; Choy J. H. Enhanced thermal stability and mechanical property of EVA nanocomposites upon addition of organo-intercalated LDH nanoparticles. Polymer 2019, 177, 274–281. 10.1016/j.polymer.2019.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gu X. Y.; Sun W. X.; Guo J.; Bu X. X.; Li H. F.; Zhang S.; Sun J. Fabrication of hydrotalcite containing N/P/S and its ternary synergistic efficiency on thermostability and fire resistance of ethylene vinyl acetate (EVA). J. Vinyl Addit. Technol. 2019, 25, 255–261. 10.1002/vnl.21684. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsby P. R. Application of magnesium hydroxide as a fire retardant and smoke-suppressing additive for polymers. Fire Mater. 1994, 18, 269–276. 10.1002/fam.810180502. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim S. Flame retardancy and smoke suppression of magnesium hydroxide filled polyethylene. J. Polym. Sci., Part B: Polym. Phys. 2003, 41, 936–944. 10.1002/polb.10453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Genovese A.; Shanks R. A. Structural and thermal interpretation of the synergy and interactions between the fire retardants magnesium hydroxide and zinc borate. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2007, 92, 2–13. 10.1016/j.polymdegradstab.2006.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.