Abstract

Background

The prognostic significance of diabetic retinopathy (DR) for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) remained unclear. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to assess whether DR predicted CVD mortality in diabetic patients.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Embase, Web of Science and Cochrane Library for cohort studies reporting the association of DR and CVD mortality. Then we pooled the data for analysis.

Results

After screening the literature, 10 eligible studies with 11,239 diabetic subjects were finally included in quantitative synthesis. The pooled risk ratio (RR) of DR, mild DR, and severe DR for CVD mortality was 1.83 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.42, 2.36; p < 0.001), 1.13 (95% CI 0.81, 1.59; p = 0.46), and 2.26 (1.31, 3.91; p = 0.003), respectively, compared to those without DR. In type 2 DM, the patients with DR had a significantly higher CVD mortality (RR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.27, 2.24; p < 0.001). Subgroup analysis also showed a significantly higher CVD mortality in DR according to various regions, study design, data source, and follow-up period (all RR > 1; all P values < 0.05). Data from 2 studies showed no significant correlation of DR and CVD mortality in diabetic patients receiving cardiovascular surgery (RR: 2.40; 95% CI 0.63, 9.18; P = 0.200).

Conclusions

DR is a risk marker of cardiovascular death, and severe DR predicts a doubled mortality of CVD in diabetes. These findings indicate the importance of early identification and management of diabetic patients with DR to reduce the risk of death.

Keywords: Diabetic retinopathy, Cardiovascular disease, Mortality, Diabetes, Meta-analysis

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) has become one of the largest public health challenges throughout the world, both in developed and developing countries [1]. According to the global estimate from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), there were about 415 million diabetic patients in 2015, and the number will probably rise to 642 million by 2040 [2]. The main burden of DM results from its complications, which can be traditionally divided into macrovascular complications (e.g., cardiovascular disease (CVD)) and microvascular complications (e.g., renal disease, retinopathy, and polyneuropathy) [3].

Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a common microvascular complication of DM, and has emerged as the leading cause of irreversible blindness in working-age population [4]. DR can be further classified as non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy (NPDR) and proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR). In the Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR), the overall 10-year incidence of retinopathy in diabetes was 74% [5]. And in patients with retinopathy at baseline, 64% developed more severe retinopathy and 17% progressed to PDR finally [6].

It has been reported that individuals with DM have poorer survival rates than those without, mainly due to the incidence of CVD [7, 8]. Therefore, efforts have been made to clarify the prognostic factors for mortality in diabetes. Although several investigations have found DR is associated with all-cause mortality and incidence of CVD events in both type 1 and type 2 DM [9], it still remains unclear whether DR serves as an indicator of CVD mortality. The inconsistent findings may result from variations in population, study design, sample size, type of DM, duration of diabetes and other factors. Clarifying the relationship between DR and CVD mortality may have significant public health implications for the primary prevention. Therefore, we performed this meta-analysis to assess whether DR is able to predict CVD mortality.

Methods

Literature search

The protocol of the meta-analysis was registered in PROSPERO website (University of York, York, UK) with a registration number of CRD42020194324. We searched PubMed, Embase, Cochrane Library, and Web of Science using following keywords with various combinations: “retinopathy”, “diabetic retinopathy”, “DR”, “diabetes”, “diabetes mellitus”, “cardiovascular disease”, “vascular disease”, “coronary heart disease”, “myocardial infarction”, “heart failure”, “heart disease”, “mortality”, and “death”. The last search date was June 1st, 2020 and the literature was limited to human study only.

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were: (1) prospective or retrospective cohort study based on population or hospital; (2) the study included at least 100 participants; (3) the median follow-up period was more than 2 years; (4) the retinopathy was examined and graded by ophthalmologists using ophthalmoscope or fundus photography, with or without applying fundus fluorescence angiography (FFA); (5) the study reported the CVD mortality in diabetic patients with and without DR; (6) deaths related to CVD included death due to various cardiovascular causes, including myocardial infarction, coronary heart disease, and heart failure; and (7) English-language bibliography.

Exclusion criteria were: (1) studies that based on the same population and failed to provide additional information; (2) ongoing or unpublished studies; and (3) unavailable to obtain the original data. The literature was independently screened and selected by two researchers (XHX, AQD), and any disagreements between them were resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment and data extraction

For the articles that passed the primary screening, they were reviewed by two authors (XHX, AQD). They independently evaluated the quality of the studies according to the STROBE statement [10]. The research with low quality or evident defects in study design were excluded from this meta-analysis. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion or judged by senior researchers. The extracted data were: (1) basic characteristics of the included studies and participants; (2) the CVD mortality in diabetic patients with and without DR.

Statistical analysis

The quantitative synthesis was performed using RevMan 5.3 software (Cochrane Collaboration, Denmark). The risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was calculated for dichotomous variables. Forest plots were used for presenting the RR for CVD mortality. In this study, DR was further classified as mild and severe DR. Mild DR was defined as mild to moderate NPDR. Severe DR was defined as severe NPDR, PDR and vison-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR). Subgroup analysis was performed according to the type of DM, regions, study design, data source, follow-up period and surgery condition. The statistical heterogeneity among studies was analyzed using the chi-squared test and presented as the I-squared (less than 50%: low heterogeneity, 50% to 75%: moderate heterogeneity, and more than 75%: high heterogeneity). Fixed-effects model was applied when the heterogeneity was lower than 50%, otherwise, random-effects model was used. The publication bias for included studies was evaluated using Funnel plots. Two-sided P-value lower than 0.05 was considered as statistically significance.

Results

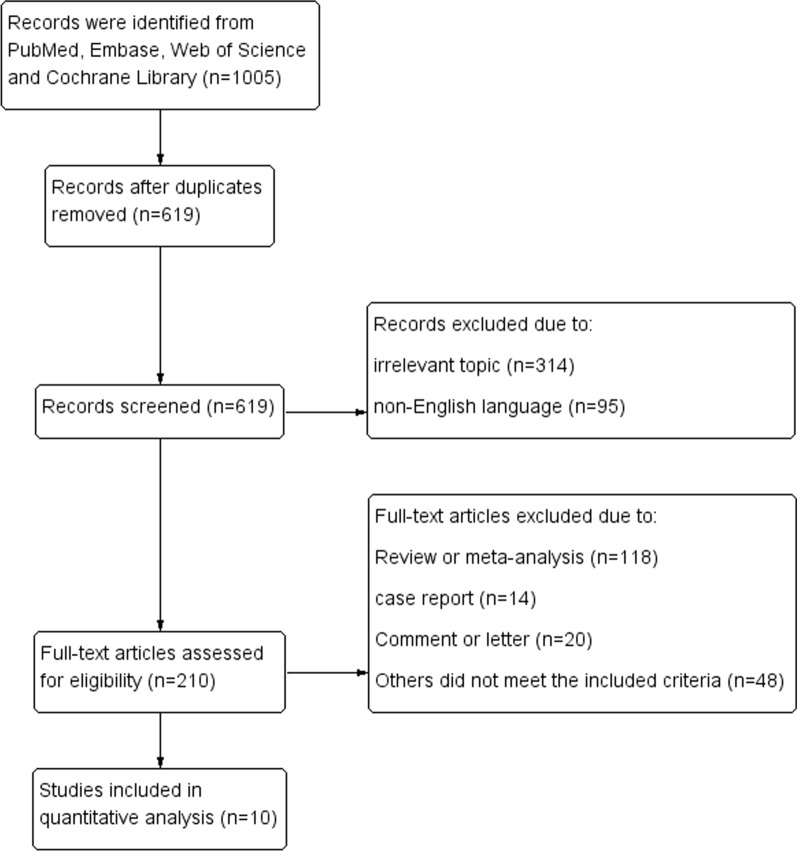

Figure 1 showed the process of the literature selection. At the initial searches, a total of 1,005 articles were potentially eligible (319 from PubMed, 453 from EMBASE, 2 from Cochrane Library, and 231 from Web of Science). After primary screening and removing duplicates, 210 potentially eligible articles were selected. After full-text review, 10 eligible cohort studies with 11,239 diabetic patients were finally included in the quantitative synthesis [11–20].

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of literature selection

The included cohort studies consisted of 7 prospective studies and 3 retrospective studies. 7 of them were based on hospital and others were based on population. Data from 5 studies were based on Asian countries and others were based on the western countries. Most participants in the included studies were type 2 DM (T2DM), and subjects in 2 studies underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [13] or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery [20] for the treatment of coronary heart disease (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the included studies

| First author | Year | Country | Study design | Data source | Follow-up (y) | Sample size | Type of DM | Male (%) | Age at baseline (y) | Diagnosis of DR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabanayagam [11] | 2019 | Singapore | Prospective cohort study | Population-based | Median 8.8 | 2964 | T2DM: 98.2% | 50.6 | 40–80 | Fundus photography |

| Takao [12] | 2020 | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | Hospital-based | Median 18.6 | 1902 | T2DM | 80.3 | Mean 55.6 | Ophthalmoscope FFA |

| Kim [13] | 2002 | Korea | Prospective cohort study | Hospital-based | 2 | 365 | T2DM | NA | NA | Ophthalmoscope |

| Rajala [14] | 2000 | Finland | Prospective cohort study | Hospital-based | 4 | 428 | T2DM: majority | 31.8 | 27–88 | Fundus photography |

| Hsieh [15] | 2017 | China | Retrospective cohort study | Hospital-based | Median 6.6 | 761 | T2DM | 56.4 | Mean 63.6 | Ophthalmoscope FFA |

| Juutilainen [16] | 2007 | Finland | Prospective cohort study | Population-based | 18 | 824 | T2DM | 51.6 | 45–64 | Ophthalmoscope |

| Liew [17] | 2008 | Australia | Prospective cohort study | Population-based | 12 | 199 | T2DM | NA | NA | Fundus photography |

| Lövestam-Adrian [18] | 2006 | Sweden | Prospective cohort study | Hospital-based | 10 | 363 | T2DM | 64.5 | Mean 54.1 | Fundus photography |

| Mottl [19] | 2014 | United States | Prospective cohort study | Hospital-based | Mean 5 | 3210 | T2DM | 61.8 | Mean 61.3 | Fundus photography |

| Ono [20] | 2002 | Japan | Retrospective cohort study | Hospital-based | Median 11.6 | 223 | T2DM | 77.1 | Mean 60.3 | Fundus photography FFA |

DM: diabetes mellitus, DR: diabetic retinopathy, FFA: fundus fluorescein angiography, NA: not available

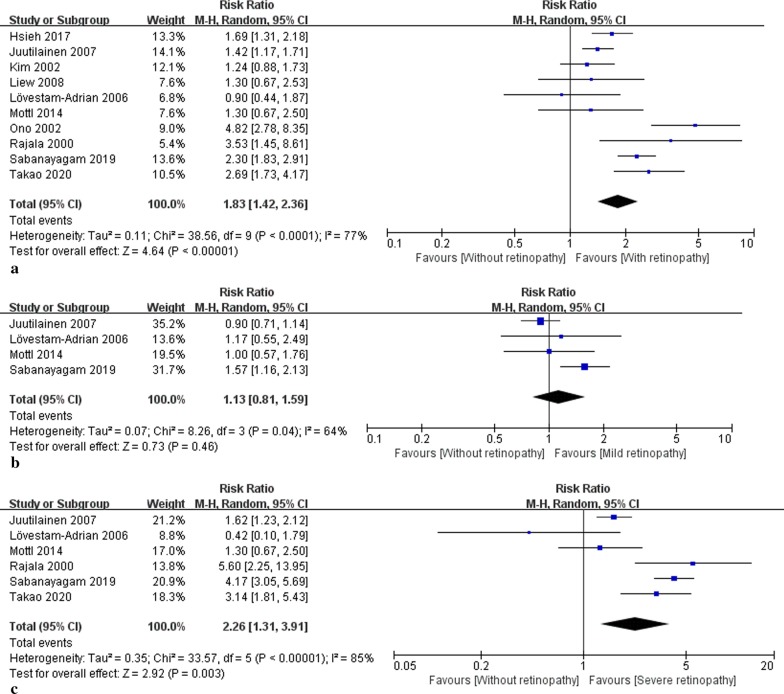

Overall, the pooled RR of DR, mild DR, and severe DR for CVD mortality was 1.83 (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.42, 2.36; p < 0.001; I2 = 77%), 1.13 (95% CI 0.81, 1.59; p = 0.46; I2 = 64%), and 2.26 (1.31, 3.91; p = 0.003; I2 = 85%), respectively, compared to those without DR (Fig. 2). In T2DM, the patients with DR had a significantly higher CVD mortality than those without (RR: 1.69; 95% CI 1.27, 2.24; p < 0.001; I2 = 75%).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot showing the RRs of DR (a), mild DR (b) and severe DR (c) for CVD mortality. RR: risk ratio, DR: diabetic retinopathy, CVD: cardiovascular disease, CI: confidence interval

Subgroup analysis was performed according to various regions, study design, data source, and follow-up period (Table 2). DR patients had significantly higher CVD mortality in both Asian (RR: 2.18; 95% CI 1.53, 3.11; p < 0.001; I2 = 82%) and western countries (RR: 1.46; 95% CI 1.22, 1.74; p < 0.001; I2 = 31%). In studies with more than 5-, 10- and 15-years follow-up, the RR of DR for CVD mortality was 1.86 (95% CI 1.40, 2.46; p < 0.001; I2 = 78%), 1.89 (95% CI 1.13, 3.16; p = 0.020; I2 = 84%), and 1.89 (95% CI 1.01, 3.56; p = 0.049; I2 = 86%), respectively. For those who underwent cardiovascular surgery, there was no significant correlation of DR and CVD mortality (RR: 2.40; 95% CI 0.63, 9.18; p = 0.200; I2 = 94%). Only 1 study analyzed the association of DR and CVD stratified by gender [16]. The results demonstrated the hazard ratio (HR) of CVD mortality in male was 1.30 (95% CI 0.86, 1.96) for mild retinopathy and 3.32 (95% CI 1.61, 6.78) for severe retinopathy. And the HR in female was 1.71 (95% CI 1.17, 2.51) for background retinopathy and was 3.17 (95% CI 1.38, 7.30) for severe retinopathy.

Table 2.

Subgroup analysis showing the pooled RRs of DR for CVD mortality

| Subgroups | Studies | Participants | RR (95% CI) | P value | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2, % | P value | |||||

| Type 2 DM | 8 | 7596 | 1.69 (1.27, 2.24) | < 0.001 | 75 | < 0.001 |

| Regions | ||||||

| Asian countries | 5 | 6017 | 2.18 (1.53, 3.11) | < 0.001 | 82 | < 0.001 |

| Western countries | 5 | 4887 | 1.46 (1.22, 1.74) | < 0.001 | 31 | 0.22 |

| Study design | ||||||

| Prospective | 7 | 8132 | 1.54 (1.16, 2.04) | 0.003 | 70 | 0.003 |

| Retrospective | 3 | 2772 | 2.69 (1.49, 4.85) | 0.001 | 84 | 0.002 |

| Data source | ||||||

| Population-based | 3 | 3903 | 1.68 (1.13, 2.52) | 0.010 | 82 | 0.004 |

| Hospital-based | 7 | 7001 | 1.93 (1.31, 2.84) | < 0.001 | 78 | < 0.001 |

| Follow-up period | ||||||

| More than 5 years | 8 | 10,111 | 1.86 (1.40, 2.46) | < 0.001 | 78 | < 0.001 |

| More than 10 years | 5 | 3360 | 1.89 (1.13, 3.16) | 0.020 | 84 | < 0.001 |

| More than 15 years | 2 | 2712 | 1.89 (1.01, 3.56) | 0.049 | 86 | 0.008 |

| After cardiovascular surgery | 2 | 588 | 2.40 (0.63, 9.18) | 0.200 | 94 | < 0.001 |

RR: risk ratio, DR: diabetic retinopathy, CVD: cardiovascular disease, DM: diabetic mellitus, CI: confidence interval

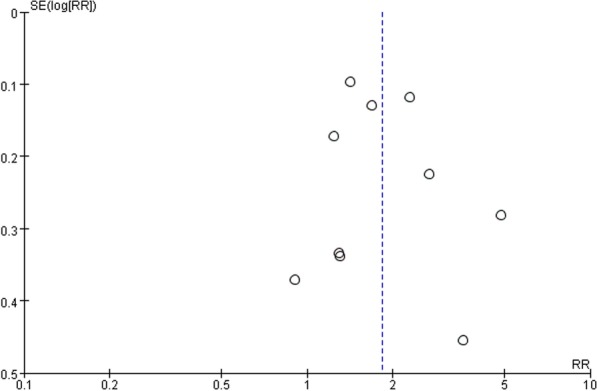

At last, Funnel plot was used to evaluate the publication bias of pooled RR of DR for CVD mortality (Fig. 3). No obvious publication bias was detected among the included studies in this meta-analysis.

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot showing the test for publication bias of pooled RR of DR for CVD mortality. RR: risk ratio, DR: diabetic retinopathy, CVD: cardiovascular disease, SE: standard error

Discussion

This meta-analysis of cohort studies shows that the presence of any degree of DR is correlated with an increased risk for cardiovascular death in diabetes. Similar results are also obtained in subgroup analysis which is stratified by various regions, study design and follow-up period. These findings indicate the importance of early screening and management of diabetic patients with DR to reduce the mortality.

The present study finds diabetic patients with PDR or VTDR predict a doubled mortality of CVD than those without, but detects no significant association of mild DR and CVD mortality. A 7-year follow-up cohort study based on 1,059 non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) also demonstrates CHD events (CHD death or nonfatal myocardial infarction) are only correlated with PDR instead of NPDR [21]. They assumed the correlation between DR and CHD may be due to similar pathophysiological backgrounds. Drinkwater et al. [22] also claimed the intensified CVD risk factor management should be considered for patients with at least moderate NPDR. However, the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-RS) explores the impact of retinopathy on mortality, and declares even minimal retinopathy is a significant predictor of increased mortality in older persons, irrespective of diabetes status [23]. Although it remains unclear whether mild DR will increase the mortality, it is also with significance to monitor NPDR patients since a part of them will finally develop to PDR.

In our study, DR is related with CVD mortality in studies with more than 10-year follow-up, which suggests DR serves as a valuable predictor for long-term survival rate in diabetic patients. A cohort study with 12-year follow-up also detects the presence of retinopathy is related to CVD death and myocardial infarction incidence in diabetes [24]. However, in the Central Australian Ocular Health Study, although diabetic patients with any DR have a higher all-cause mortality than those without, no relationship is detected in DR and cardiac mortality [25]. Therefore, further studies are still needed. In fact, assessing the mortality related to DM presents a lot of challenges. It cannot be precisely assessed from death certificates since deaths in diabetic patients usually result from one of its complications (e.g. stroke, heart disease and renal failure), which are regarded as the cause of death. Furthermore, it should be noticed that the assessment of long-term mortality risk in diabetes must include some related variables, such as glycemic control, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), renal function, blood pressure, dyslipidemia, and smoking habit [26].

The long-term mortality in diabetic patients with tractional retinal detachment (TRD) also deserves attention. Shukla et al. [27] compare the long-term all-cause mortality rate in TRD population and those diabetic patients with minimal to no retinopathy. They calculate a 48.7% 10-year all-cause mortality in TRD patients and even a higher mortality in those with worse vison. The results indicate TRD requiring vitrectomy surgery is a marker for poor long-term survival. Banerjee et al. [28] observe the mortality of 148 PDR patients undergoing vitrectomy surgery, and detect the 3-, 5- and 7-year survival rates are 94%, 86% and 77%, respectively. In an Australian population, the 5-, 7- and 9-year survival rates of diabetic patients undergoing vitrectomy for DR are 84.4%, 77.9% and 74.7%, respectively, with CVD as the most common cause of death [29].

It should be clarified that the main findings in our study cannot be applied in T1DM, since the majority of included participants were T2DM. The mortality and risk factors have been also evaluated in T1DM, and similar results were obtained. In an observational cohort study of 725 African-Americans with T1DM, the 3-year all-cause mortality is 18.1%, and 90% of the deceased are diagnosed with DR [30]. In a 12-year observation study of 462 T1DM, the relative risk for death is 7.0 times higher in patients with sight-threatening retinopathy, compared with those with no retinopathy [31]. However, this association disappears when retinopathy was adjusted for presence of macroalbuminuria. In addition, the 20-year mortality is calculated in a Germany cohort with T1DM, and the results also detect no association of DR and mortality [32]. Therefore, further studies are needed and various confounding factors should be taken into account.

The limitations of this study should be also noted. First, different definitions of CVD among the included investigations may influence the results. Second, some included investigations are retrospective cohort studies, and there is no age- and gender-matched study included in the meta-analysis. Third, some included studies contain a relatively small sample size. Fourth, the heterogeneity among the studies is large, though subgroup analysis is performed and random effects model is applied. Fifth, due to the limited data from the included studies, we fail to calculate the association of DR and specific cause of CVD death, such as CHD, arrhythmia, and sudden cardiac death. Sixth, we do not examine the contribution of individuals’ baseline characteristics (e.g. age, gender, HbA1c, and duration of DM) as well as therapeutic impacts in evaluating the relationship between DR and CVD mortality. Seventh, we do not evaluate the degree to which DR is itself a sign of poorly controlled CVD risk factors. And it is hard to prove whether DR is an independent risk factor for CVD, or DR has overlapped effects with other factors for CVD, including kidney disease, hyperglycemia and hypertension. Eighth, we do not perform a further sub-group analysis comparing the different diagnostic procedure of DR. In addition, since the majority of the included participants are T2DM, the findings in our study cannot be directly applied in T1DM.

Conclusion

Our results show that DR is a risk marker of cardiovascular death and severe DR predicts a doubled mortality of CVD in diabetes. These findings indicate the importance of early identification and management of diabetic patients with DR to reduce the risk of death.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants who contribute to this study.

Abbreviations

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- IDF

International diabetes federation

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DR

Diabetic retinopathy

- NPDR

Non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- PDR

Proliferative diabetic retinopathy

- WESDR

Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy

- RR

Risk ratio

- CI

Confidence interval

- VTDR

Vison-threatening diabetic retinopathy

- CHD

Chronic heart disease

- PCI

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- CABG

Coronary artery bypass graft

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the research: XHX, AQD; Acquisition and interpretation of the data: XHX, BS, AQD; Statistical analysis and writing of the manuscript: XHX, SZ, DDW, ZH, AQD; Revision of the manuscript: XHX, BS, SZ, DDW, ZH, AQD. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Zhejiang Province Natural Science Foundation (LY17H020008), National Health Commission Science Research Fund-Zhejiang Major Science and Technology Projects for Health (WKJ-ZJ-2121). The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

All data used for this meta-analysis has been contained within the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Zimmet P, Alberti KG, Magliano DJ, Bennett PH. Diabetes mellitus statistics on prevalence and mortality: facts and fallacies. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(10):616–622. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2016.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas 7th edition. 2016. https://www.diabetesatlas.org. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Zheng Y, Ley SH, Hu FB. Global aetiology and epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its complications. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14(2):88–98. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cheung N, Mitchell P, Wong TY. Diabetic retinopathy. Lancet. 2010;376(9735):124–136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein R. Epidemiology of diabetic retinopathy. In: Diabetic Retinopathy. Duh E, ed. Totowa: Humana Press. 2008.

- 6.Varma R. From a population to patients: the Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:1857–1858. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klein R, Klein BE, Moss SE, Cruickshanks KJ. Association of ocular disease and mortality in a diabetic population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999;117(11):1487–1495. doi: 10.1001/archopht.117.11.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein BE, Klein R, McBride PE, Cruickshanks KJ, Palta M, Knudtson MD, et al. Cardiovascular disease, mortality, and retinal microvascular characteristics in type 1 diabetes: Wisconsin epidemiologic study of diabetic retinopathy. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(17):1917–1924. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.17.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kramer CK, Rodrigues TC, Canani LH, Gross JL, Azevedo MJ. Diabetic retinopathy predicts all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in both type 1 and 2 diabetes: meta-analysis of observational studies. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(5):1238–1244. doi: 10.2337/dc11-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007; 4:e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Sabanayagam C, Chee ML, Banu R, Cheng CY, Lim SC, Tai ES, et al. Association of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic kidney disease with all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in a multiethnic Asian population. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e191540. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takao T, Suka M, Yanagisawa H, Kasuga M. Combined effect of diabetic retinopathy and diabetic kidney disease on all-cause, cancer, vascular and non-cancer non-vascular mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: A real-world longitudinal study. J Diabetes Investig. 2020. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Kim YH, Hong MK, Song JM, Han KH, Kang DH, Song JK, et al. Diabetic retinopathy as a predictor of late clinical events following percutaneous coronary intervention. J Invasive Cardiol. 2002;14(10):599–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rajala U, Pajunpää H, Koskela P, Keinänen-Kiukaanniemi S. High cardiovascular disease mortality in subjects with visual impairment caused by diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2000;23(7):957–961. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsieh YM, Lee WJ, Sheu WH, Li YH, Lin SY, Lee IT. Inpatient screening for albuminuria and retinopathy to predict long-term mortality in type 2 diabetic patients: a retrospective cohort study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:29. doi: 10.1186/s13098-017-0229-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Juutilainen A, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälä K, Laakso M. Retinopathy predicts cardiovascular mortality in type 2 diabetic men and women. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(2):292–299. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liew G, Wong TY, Mitchell P, Cheung N, Wang JJ. Retinopathy predicts coronary heart disease mortality. Heart. 2009;95(5):391–394. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2008.146670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lövestam-Adrian M, Hansson-Lundblad C, Torffvit O. Sight-threatening retinopathy is associated with lower mortality in type 2 diabetic subjects: a 10-year observation study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;77(1):141–147. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mottl AK, Pajewski N, Fonseca V, Ismail-Beigi F, Chew E, Ambrosius WT, et al. The degree of retinopathy is equally predictive for renal and macrovascular outcomes in the ACCORD Trial. J Diabetes Complications. 2014;28(6):874–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ono T, Kobayashi J, Sasako Y, Bando K, Tagusari O, Niwaya K, et al. The impact of diabetic retinopathy on long-term outcome following coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002; 40(3):428–36. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Miettinen H, Haffner SM, Lehto S, Rönnemaa T, Pyörälà K, Laakso M. Retinopathy predicts coronary heart disease events in NIDDM patients. Diabetes Care. 1996;19(12):1445–1448. doi: 10.2337/diacare.19.12.1445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drinkwater JJ, Davis TME, Hellbusch V, Turner AW, Bruce DG, Davis WA. Retinopathy predicts stroke but not myocardial infarction in type 2 diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study Phase II. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12933-020-01018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher DE, Jonasson F, Klein R, Jonsson PV, Eiriksdottir G, Launer LJ, et al. Mortality in older persons with retinopathy and concomitant health conditions: the age. Gene/Environ Suscep Reykjavik Stud Ophthalmol. 2016;123(7):1570–1580. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.02.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fuller JH, Stevens LK, Wang SL. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity: the WHO Mutinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(Suppl 2):S54–64. doi: 10.1007/PL00002940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Landers J, Liu E, Estevez J, Henderson T, Craig JE. Presence of diabetic retinopathy is associated with worse 10-year mortality among Indigenous Australians in Central Australia: The Central Australian ocular health study. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;47(2):226–232. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Grauslund J. Long-term mortality and retinopathy in type 1 diabetes. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010; 88 Thesis1:1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Shukla SY, Hariprasad AS, Hariprasad SM. Long-term mortality in diabetic patients with tractional retinal detachments. Ophthalmol Retina. 2017;1(1):8–11. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Banerjee PJ, Moya R, Bunce C, Charteris DG, Yorston D, Wickham L. Long-term survival rates of patients undergoing vitrectomy for proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2016;23(2):94–98. doi: 10.3109/09286586.2015.1089578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu E, Estevez J, Kaidonis G, Hassall M, Phillips R, Raymond G, et al. Long-term survival rates of patients undergoing vitrectomy for diabetic retinopathy in an Australian population: a population-based audit. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2019;47(5):598–604. doi: 10.1111/ceo.13466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roy M, Rendas-Baum R, Skurnick J. Mortality in African-americans with type 1 diabetes: the New Jersey 725. Diabet Med. 2006;23(6):698–706. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torffvit O, Lövestam-Adrian M, Agardh E, Agardh CD. Nephropathy, but not retinopathy, is associated with the development of heart disease in Type 1 diabetes: a 12-year observation study of 462 patients. Diabet Med. 2005;22:723–729. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heller T, Kloos C, Lehmann T, Schiel R, Lorkowski S, Wolf G, et al. Mortality and its causes in a german cohort with diabetes mellitus Type 1 after 20 years of follow-up: the JEVIN trial. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2018;126(6):387–393. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-113452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data used for this meta-analysis has been contained within the manuscript.