Abstract

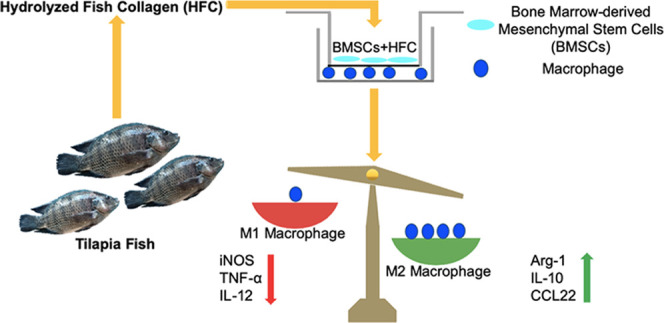

A key issue in the field of tissue engineering and stem cell therapy is immunological rejection after the implantation of allogeneic bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs). In addition, maintaining the immunoregulatory function of BMSCs is critical to achieving tissue repair. In recent years, scientists have become interested in fish collagen because of its unique osteoinductive activity. However, it is still unclear whether osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by fish collagen maintain their immunoregulatory functions. To address this question, BMSCs were isolated from 8-week-old male BALB/c mice, and a noncontact coculture model was established consisting of macrophages and BMSCs treated with hydrolyzed fish collagen (HFC). Cell proliferation of the macrophages was determined by MTT. The gene and protein expression levels of the M1 and M2 macrophage markers were measured by real-time PCR and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). To study the role of TNF-α-induced gene/protein 6 (TSG-6), TSG-6 was targeted by short interfering RNA (siRNA) in BMSCs, then the osteogenic differentiation ability of the BMSCs was examined by western blotting. The mRNA expression levels of interleukin-10 (IL-10), CCL22 (a macrophage-derived chemokine), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and interleukin-12 (IL-12), and the protein expression levels of arginase-1 (Arg-1) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) of macrophages cocultured with TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC were detected by real-time PCR and western blotting, respectively. The results showed that the osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by HFC did not affect the proliferation of macrophages. Osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by HFC promoted the expression of M2 macrophage markers IL-10 and CCL22, while HFC inhibited the expression of M1 macrophage markers, including TNF-α and IL-12. The TSG-6 knockdown led to a decrease in the production of TSG-6 without impairing the expression of bone sialoprotein (BSP), osteocalcin (OCN), and Runt-related transcription factor 2 (RUNX2) by BMSCs. TSG-6 silencing significantly counteracted the effect of HFC, and the expression of IL-10, CCL22, and Arg-1 were all decreased in the macrophages cocultured with TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC, while that of TNF-α, IL-12, and iNOS were increased relative to the BMSCs+HFC group. The data demonstrated that osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by fish collagen retained their immunomodulatory functions. This study provides an additional scientific basis for future applications of fish collagen as an osteogenic component in the fields of tissue engineering and stem cell therapy.

1. Introduction

Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs) are the most widely studied seed cells in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering. They are easy to obtain and have the ability to multidifferentiate under certain conditions, which is the foundation for their various roles in the field of regenerative medicine. In addition to the above characteristics, it has been shown that BMSCs have strong immunoregulatory functions. For example, BMSCs can inhibit the proliferation of T lymphocytes and inhibit the secretion of immune cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α).1 The immunoregulatory functions of BMSCs have important implications in the fields of tissue engineering and stem cell therapy, where a critical issue is the immunological rejection of allogeneic mesenchymal stem cells after implantation. The immunoregulatory functions of BMSCs are essential to escape the attack of lymphocytes, including natural killer cells and activated T cells.2 Therefore, maintaining the immunoregulatory functions of BMSCs is of great importance for the ultimate success of tissue repair.3

In recent years, studies have found that a traditional osteogenic medium can induce the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs, which retain their immunoregulatory functions after differentiation.4 Other studies showed that many biological materials can induce the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs;5 however, it is still unclear whether BMSCs can retain their immunoregulatory functions after stimulation by these biomaterials. Our previous studies found that hydrolyzed fish collagen has good osteoinductivity,6,7 which raised the question of whether HFC affects (either weakens or enhances) the immunoregulatory functions of mesenchymal stem cells.

As important immune cells in the body, macrophages participate in the entire inflammatory response process.8 Macrophages are also the major players involved in acute rejection after homotransplantation or xenotransplantation. After transplantation, macrophages promote rejection by secreting cytokines and mediating antigen presentation. Macrophages can also induce the differentiation of Th17 cells and cause acute graft rejection. Dayan et al. found that mesenchymal stromal cells can promote the activation of M2 macrophages and inhibit the activation of M1 macrophages.9 Although the most significant effect of macrophages on tissue engineering is the allogeneic response, studies have shown that MSCs can reduce the occurrence of macrophage-mediated foreign body reactions.10

The present study established a noncontact coculture model consisting of BMSCs and macrophages to compare the effect of BMSCs on the secretion of macrophage-associated inflammatory factors before and after osteogenic differentiation. The mechanism by which BMSCs exert immunomodulatory functions at both the RNA and protein levels was also studied to provide a scientific basis for future applications of HFC as a biomaterial additive with anti-inflammatory activity.

2. Results

2.1. HFC-Induced BMSCs have Minimal Impact on the Proliferation of Cocultured Macrophages

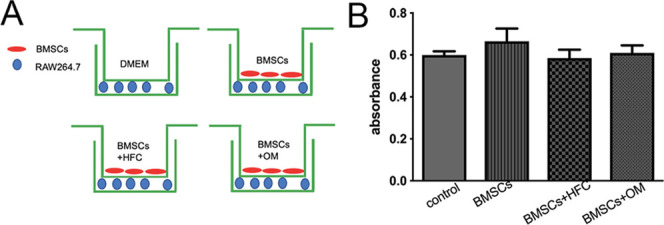

After being cocultured with HFC-induced BMSCs, as shown in Figure 1A (BMSCs+HFC), no significant differences in macrophage proliferation among all groups were found. The macrophages in the BMSCs+HFC group exhibited a proliferation rate comparable to those of the control group, BMSCs group, and the BMSCs+OM group (Figure 1B), suggesting that the HFC-induced BMSCs had good biocompatibility with macrophages in this experimental system.

Figure 1.

(A) Coculture model. (B) MTT results for macrophages after being cultured alone (control), or cocultured with BMSCs (BMSCs), BMSCs induced by HFC (BMSCs+HFC), and BMSCs induced by osteogenic medium (BMSCs+OM). Error bars indicate SD (n = 3 per group).

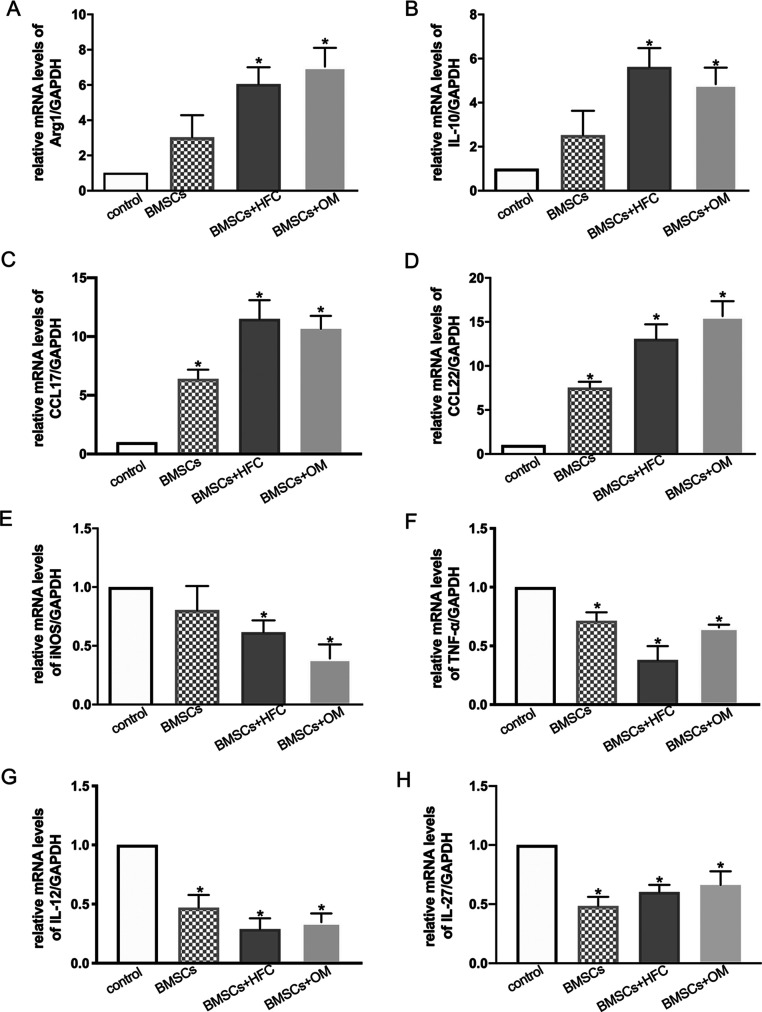

2.2. HFC-Induced BMSCs Inhibit the Expression of M1 Markers and Promote M2 Polarization of Macrophages

Compared with the control group, the mRNA expression levels of Arg-1, IL-10, and CCL17 (thymus and activation-regulated chemokine), and CCL22 (macrophage-derived chemokine) by the macrophages cocultured with HFC-induced BMSCs were significantly higher (Figure 2A–D, respectively), whereas the expression levels of iNOS, TNF-α, IL-12, and IL-27 were markedly lower in the HFC-induced BMSC group (Figure 2E–H, respectively). Taken together, these data demonstrate that HFC-treated BMSCs inhibit M1 polarization but promote the M2 polarization of macrophages.

Figure 2.

Relative gene expression levels of Arg-1 (A), IL-10 (B), CCL17 (C), CCL22 (D), iNOS (E), TNF-α (F), IL-12 (G), and IL-27 (H) in macrophages after being cultured alone (control), or cocultured with BMSCs (BMSCs), BMSCs induced by HFC (BMSCs+HFC), and BMSCs induced by osteogenic medium (BMSCs+OM). Data are presented as mean values with standard deviation as error bars (n = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with the control group.

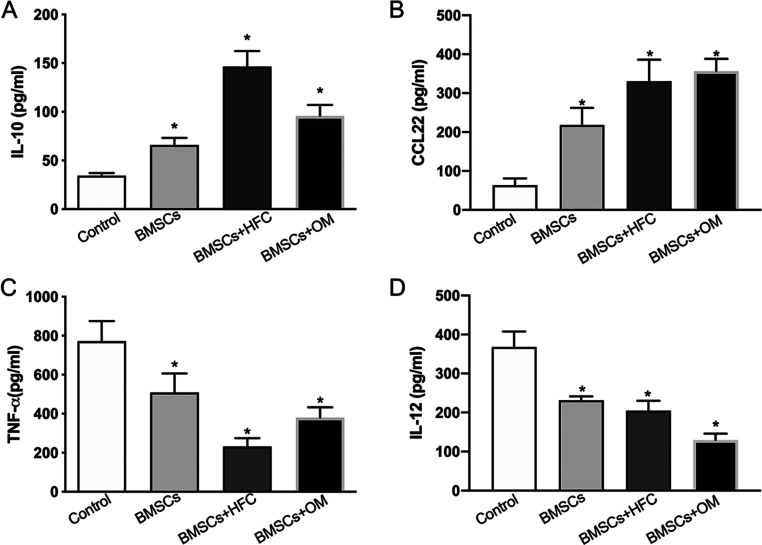

2.3. HFC-Treated BMSCs Show Differential Effects on the Secretion of IL-10, CCL22, TNF-α and IL-12 by Macrophages

The amounts of IL-10 and CCL22 produced by macrophages in the HFC-treated BMSC group (BMSCs+HFC) were both substantially higher than those in the control group (Figure 3A,B). In contrast, the amounts of TNF-α and IL-12 secreted by macrophages were significantly lower in the HFC-treated BMSC group (BMSCs+HFC) than in the control group (Figure 3C,D).

Figure 3.

Production of IL-10 (A), CCL22 (B), TNF-α (C), and IL-12 (D) in macrophages assayed by ELISA. The data represent the mean ± SD of n = 3. *p < 0.05 compared with the control group.

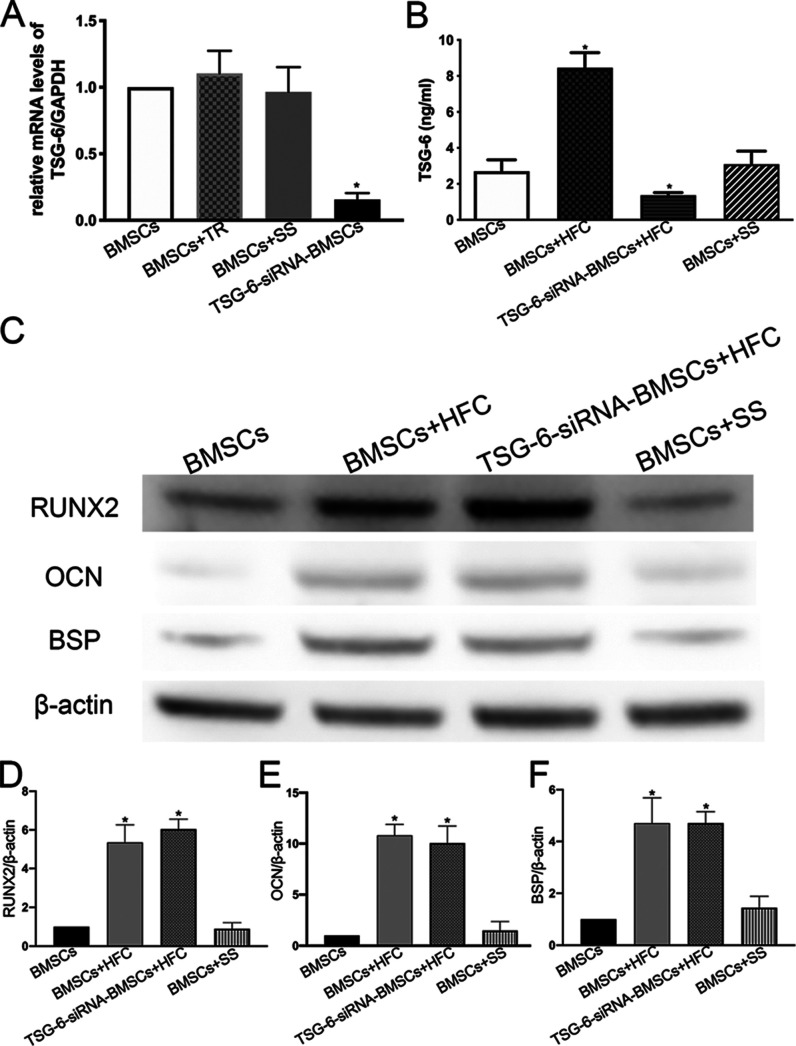

2.4. TSG-6 siRNA Specifically Decreases the Expression of TSG-6 by BMSCs at Both the RNA and Protein Levels, without Impairing the Osteogenic Differentiation Ability of BMSCs

As shown in Figure 4A, the gene expression of TSG-6 was significantly decreased in BMSCs silenced by siRNA-TSG-6 (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs) compared with that in the untreated BMSCs. In addition, the mRNA expression of TSG-6 was significantly decreased in TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs compared with that in scrambled siRNA-transfected cells (BMSCs+SS) or transfection reagent-treated cells (BMSCs+TR), which were used as negative controls (p < 0.05). There was no statistical difference between the untreated BMSCs and the BMSCs+SS group or the BMSCs+TR group. ELISA was performed to assess the expression of the TSG-6 protein in the BMSCs transfected with siRNA-TSG-6. Consistent with the real-time PCR data, ELISA revealed that the amount of TSG-6 secreted by BMSCs was significantly increased by HFC treatment, and this increase was abolished by siRNA transfection. There was no statistical difference between the untreated BMSCs and the scrambled siRNA-transfected cells (BMSCs+SS) (Figure 4B). RUNX2, OCN, and BSP are important osteogenic differentiation markers, as shown in Figure 4C–F. The expression levels of RUNX2, OCN, and BSP in both the BMSCs+HFC and TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC groups were significantly higher than those in the control group, while there were no significant differences between the BMSCs+HFC and TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC groups. In addition, no significant differences were found between the BMSC group and the BMSCs+SS (BMSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA) group (Figure 4C–F). These results demonstrated that the TSG-6 knockdown by siRNA did not affect the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs in the presence of HFC.

Figure 4.

Expression of TSG-6 in BMSCs and the effect of TSG-6 siRNA on the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. (A) mRNA expression levels of TSG-6 in BMSCs, BMSCs treated with transfection reagents only (BMSCs+TR), BMSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (BMSCs+SS), and BMSCs transfected with TSG-6 siRNA (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs) were determined by real-time RT-PCR. Results are presented as the mean ± standard deviation of three independent experiments. *p < 0.05 compared with the BMSC group. (B) TSG-6 concentrations measured in the supernatants from BMSCs, BMSCs treated with HFC (BMSCs+HFC), TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs treated with HFC (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC), and BMSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (BMSCs+SS) with data given as mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05 compared with the BMSC group. (C) Western blot analysis of RUNX2, OCN, and BSP from cell lysates of the BMSCs, BMSCs treated with HFC (BMSCs+HFC), TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs treated with HFC (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC), and BMSCs transfected with scrambled siRNA (BMSCs+SS). (D–F) Densiometric analyses of western blot images. *p < 0.05, n = 3.

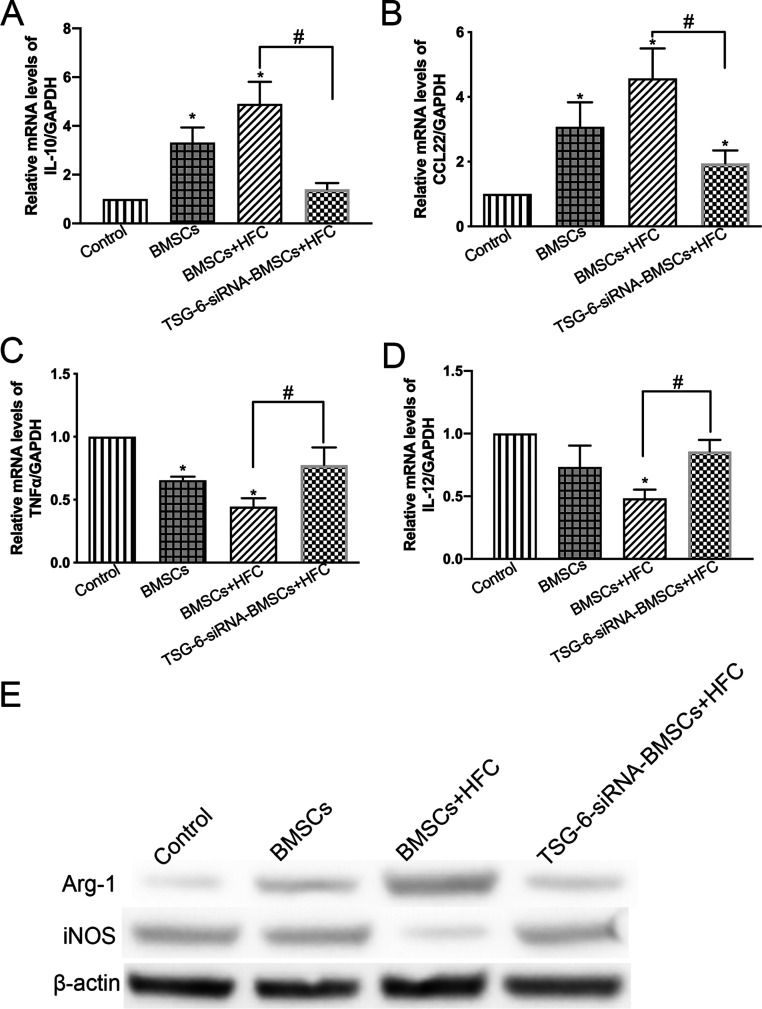

2.5. Immunoregulatory Functions of HFC-Treated BMSCs Depend on TSG-6 Expression

The expression levels of the M2- and M1 macrophage-related genes in the macrophages were analyzed using real-time PCR (Figure 5A–D). The expression levels of IL-10 and CCL22 were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the macrophages cocultured in the presence of BMSCs+HFC than in the control macrophages. This effect was counteracted by the silencing of TSG-6, as shown in the TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC group, where the expression levels of IL-10 and CCL22 were significantly decreased (p < 0.05) compared to those in the BMSCs+HFC group (Figure 5A,B). On the other hand, the expression levels of TNF-α and IL-12 were significantly inhibited (p < 0.05) in the macrophages cocultured in the presence of BMSCs+HFC as compared with those in the control macrophages. Remarkably, TSG-6 silencing significantly counteracted this inhibitory effect, and the expression levels of TNF-α and IL-12 were significantly higher (p < 0.05) in the macrophages cocultured in the presence of TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC compared to those in the BMSCs+HFC group (Figure 5C,D). Western blotting showed that the expression of Arg-1 was upregulated in macrophages cocultured with HFC-treated BMSCs (BMSCs+HFC), while iNOS expression was inhibited (Figure 5E), suggesting that HFC-treated BMSCs had strong immunoregulatory effects on the cocultured macrophages. However, the TSG-6 knockdown abolished such changes in the expression of Arg-1 and iNOS, as shown in Figure 5E. The expression of Arg-1 was decreased, and iNOS expression was elevated after the TSG-6 knockdown in TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs treated with HFC (the TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC).

Figure 5.

(A–D) Relative gene expression levels of IL-10, CCL22, TNF-α, and IL-12 in macrophages after being cultured alone (Control), or cocultured with BMSCs (BMSCs), BMSCs induced by HFC (BMSCs+HFC), and TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs induced by HFC (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC). Data are presented as mean values, with standard deviation represented as error bars (n = 3), *p < 0.05 compared with the control group, #p < 0.05. (E) Western blot analysis of Arg-1, iNOS, and GAPDH protein levels in macrophages after being cultured alone (Control), and cocultured with BMSCs (BMSCs), BMSCs treated with HFC (BMSCs+HFC), and TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs treated with HFC (TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC).

3. Discussion

The unique immunomodulatory functions of mesenchymal stem cells enable them to evade immune recognition and inhibit immune responses. Such biological properties render them ideal for tissue repair and inhibiting immunological rejection, making them suitable for cellular therapies and tissue engineering. A previous study showed that HFC could induce the osteogenic differentiation of MSCs.6 Nevertheless, it is still unclear whether osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by HFC maintain their immunomodulatory functions.

As shown in the MTT assay, there were no significant differences between BMSCs treated with the HFC group and other groups regarding macrophage proliferation. As important immune cells, macrophages play important roles in inflammatory responses, wound repair, disease progression, and foreign body reactions. The maintenance of the number and activity of macrophages is critical for these biological processes. The data from this study indicate that macrophages could maintain their normal proliferative ability in a coculture system with HFC-induced BMSCs. In addition, it was previously found that HFC exhibits good biocompatibility with both macrophages and BMSCs,6,11 which was further supported by this study.

To investigate the effect of osteogenically differentiated BMSCs treated with HFC on the phenotypic changes of macrophages, the expression levels of relevant macrophage markers were examined at both the gene and protein level, and it was found that HFC-treated BMSCs inhibited M1 macrophage-related markers and increased M2 macrophage-related markers. As an important marker of M2 macrophages, IL-10 inhibits the Th1 cell response, inhibits antigen presentation and cytokine synthesis by macrophages, and promotes the proliferation, differentiation, and antibody production of B cells.12 CCL22 (also known as a macrophage-derived chemokine, MDC), is a chemokine that is predominantly produced by M2 macrophages and has been used as an M2 macrophage marker.13 On the other hand, as an important marker of M1 macrophages, TNF-α mainly mediates inflammation, activates leukocytes, enhances the adhesion of neutrophils and monocytes, and accelerates the translocation of inflammatory cells to the intercellular space. TNF-α also causes the secretion of other cytokines such as IL-1β.14 IL-12 has been recognized as a proinflammatory heterodimeric cytokine and an M1 macrophage marker. It is primarily produced by activated macrophages and plays a key role in the activation of CD4+ T helper cells and natural killer cells.15 Shahbazi et al. demonstrated that the upregulation of IL-10 in macrophages reflected a successful transition from the M1 to M2 phenotype via hyaluronic acid treatment.16 Recently, it has been suggested that CCL22 is one of the robust markers for the in vitro macrophage polarization study,17 and elevated expression of CCL22 by THP-1 cells in the extracellular matrix has been observed, indicating spontaneous induction of M2-like polarity of monocyte/macrophages by their specific ECM environment.18 Shayan et al. studied macrophage interactions with nanopatterned bulk metallic glass-based biomaterials, and they found that the secretion of TNF-α and IL-12 by murine macrophages was significantly reduced after culture on nanopatterned bulk metallic glasses, which demonstrated that their biomaterials could modulate macrophage polarization.19 Consistent with the abovementioned studies, our results indicate that osteogenically differentiated BMSCs treated with HFC promoted M2 polarization of macrophages and inhibited M1 polarization.

M1 macrophages secrete a large number of proinflammatory cytokines, participate in anti-infective immunity, and cause inflammatory damage. M2 macrophages produce a large number of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-4 and chemokines such as CCL18, inhibit inflammatory responses, and promote wound repair.20 The data from this study suggest that HFC-induced BMSCs can regulate the polarized phenotypes of macrophages in this coculture system, which has the feature of inhibiting M1 polarization while increasing M2 polarization. The rejection of allogeneic stem cells remains one of the most challenging bottlenecks for using stem cells in tissue engineering and stem cell therapy.21 Mesenchymal stem cells contribute to the creation of a well-balanced microenvironment via tuning the adaptive, innate, and immune cells, and the cell–cell interactions and specific secretome of mesenchymal stem cells and immune cells facilitate tissue regeneration.22 Liu et al. demonstrated that MSCs could significantly increase the recruitment of macrophages into injured sites to promote tissue repair and alleviate immune disorders.23 A paper from Ding et al. indicated that bone marrow mesenchymal stem cell-based constructs suppressed scaffold-induced inflammation and promoted cartilage tissue regeneration through M2 polarization of macrophages.24 It has been shown that the intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells before allogeneic corneal transplantation shifts the macrophage polarization toward an M2 phenotype, which imparts protection against corneal allograft rejection.25 Based on the data from the present study, it is possible to reasonably extrapolate that the transplantation of HFC-induced BMSCs into the host body could reduce any rejection reaction. However, further in vivo investigations are still needed.

The previous findings prompted the study of the mechanisms underlying the immunoregulatory functions of HFC-induced BMSCs. It has been found that some effector molecules or pathways are involved in regulating the activation and polarization of macrophages by MSCs.26,27 Among these, TNF-α-induced gene/protein 6 (TSG-6), which is a secreted glycoprotein, is the most crucial one. TSG-6 is one of the important immunomodulatory factors associated with the anti-inflammatory effect, and the therapeutic activities of MSCs in many animal models of disease have been observed to be dependent on TSG-6.28 Previous studies have suggested that TSG-6 secreted by MSCs can regulate the polarization of macrophages,26 which inspired an investigation of whether TSG-6 is involved in the mechanisms leading to the immunoregulation by HFC-induced BMSCs. To gain further insight into the role of TSG-6 (TNF-α-induced gene/protein 6), BMSCs whose TSG-6 was knocked down by siRNAs were used in the present study. The results showed that after TSG-6 expression was knocked down, the inductive effect of HFC was neutralized. At the same time, we needed to confirm that the TSG-6 knockdown did not undermine the osteogenic differentiation ability of BMSCs. RUNX2 is the earliest transcription factor expressed during osteogenic differentiation, and it regulates the expression of downstream transcription factors and related osteogenic genes. Therefore, RUNX2 is one of the most reliable markers for the identification of osteogenic differentiation.29 OCN is a highly specific noncollagen protein synthesized and secreted by osteoblasts, and it is an important marker for the differentiation and maturation of osteoblasts.30 Bone sialoprotein (BSP) is one of the main noncollagenous glycosylated phosphoproteins specifically expressed in mineralized tissue and is considered to be a marker of mid-to-late stage osteogenic differentiation.31 In the present study, knockdown of TSG-6 did not impair the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs. The expression levels of RUNX2, OCN, and BSP in both BMSCs+HFC and TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs+HFC groups were significantly higher than those in the control group. These results are consistent with previous findings that demonstrated that HFC activates the ERK-RUNX2 pathway to promote the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.6

Finally, it was found that TSG-6 and Arg-1 mediated the immunoregulatory function of HFC-treated BMSCs (Figure 5A–D). Macrophages are a highly plastic population of cells, and their function can be remodeled by unique sets of soluble factors. When participating in tissue repair, macrophages highly express arginase-1 (Arg-1),32 an enzyme that converts l-arginine to urea and l-ornithine, and Arg-1 is a well-recognized M2 macrophage marker. Heo et al. found that indirect coculture with adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells increased the expression of arginase-1 in human peripheral blood monocytes, which demonstrated that mesenchymal stem cell-secreted factors promoted M2 macrophages polarization.33 These findings are consistent with previous studies showing that TSG-6 promotes the expression of Arg-1.34 Van et al. found that Arg-1 secreted by M2 macrophages binds to its substrate arginine, decomposes arginine into polyamine and proline, and then promotes cell division and collagen formation, which can repair and remodel the damaged tissues in the late phase of inflammation.35 Collectively, the data from this study suggest that HFC induces the production of TSG-6 by BMSCs, and TSG-6 upregulates Arg-1 expression in macrophages.

Other than fish collagen, the majority of collagen is derived from mammal sources.36 Chiu et al. found that chicken collagen served as a good modulator during early osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by facilitating RUNX2 activation.37 Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) cultured on bovine collagen stained positive for calcium deposition by day 30, more strongly than hMSCs cultured on other substrates.38 In a study to assess the osteogenic capability of rat BMSCs grown on calf collagen, a steady increase in osterix expression was observed. Osterix is considered to be one of the master transcription factors of osteogenic differentiation in mesenchymal stem cells.39 A recent study demonstrated that electrospun nanofibers with rat collagen had the ability to induce chondrogenesis of MSCs and accelerate the regeneration of injured cartilage surfaces.40 However, few studies have investigated the correlation between animal-derived collagen and the immunomodulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells, and no study has been performed to directly compare the effect of hydrolyzed fish collagen with animal-derived collagen. Using collagen-based biomaterials and stem cells to manipulate the innate or adaptive immune system of the host may induce both systemic and local proregenerative immune responses and ultimately promote tissue repair, and therefore, a deeper understanding of the interactions among collagen, stem cells, and immune cells is urgently needed, especially considering the great potential of the application of collagen and stem cells in the fields of tissue engineering and stem cell therapy.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

The hydrolyzed fish collagen (HFC) used in this study was provided by the Shanghai Fisheries Research Institute (Shanghai, China). The HFC was derived from tilapia fish. The physical–chemical properties of the HFC, including the contact angle, molecular weight distribution, and amino acid composition have been described previously.6

4.2. Isolation and In Vitro Culturing of BMSCs

This experiment was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital, which is affiliated with the School of Medicine, Shanghai Jiao Tong University. BALB/c mice aged 8 weeks were sacrificed by cervical dislocation and thoroughly sterilized with 75% ethanol, after which a femur bone was quickly removed under aseptic conditions. After washing with phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.4, PBS), the bone marrow cavity was exposed to reveal the bone marrow, and Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) plus 1% penicillin–streptomycin was repeatedly used to rinse and dissociate the bone marrow mass to prepare single-cell suspensions. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, the cell pellet was resuspended and transferred to a culture flask. The cells were incubated in an incubator with 5% CO2 at 37 °C. The cell health was evaluated every other day, and the medium was changed after 48 h. After the cells were attached to the bottom of the culture flask and the cell density reached 80%, the cells were sub-cultured at a ratio of 1:2, and the cells at 3–5 passages were used for the subsequent experiments. All of the steps were performed under sterile conditions.

4.3. Establishment of the Noncontact Coculture System

A noncontact coculture system was established using Transwell chambers with a micropore diameter of 0.4 μm. Macrophages (obtained from the cell bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China) and pretreated with 1 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 6 h) were diluted to 1 × 105 cells/mL in the medium and then transferred to 12-well plates (1 mL of cells per well). For the induction of BMSCs, the BMSCs were seeded at a density of 5 × 104/mL in a 12-well plate. Once the cells reached 80% confluency, the growth medium was replaced with DMEM containing 0.2 mg/mL of HFC (BMSCs+HFC) or osteogenic medium (OM, DMEM supplemented with 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, 0.1 μM dexamethasone, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid, and 10% FBS). The cells were incubated for 7 days, with the medium changed daily. DMEM medium, BMSCs, BMSCs induced with HFC for 7 days, TSG-6-siRNA–BMSCs induced with HFC for 7 days, and BMSCs induced with OM for 7 days were separately added to individual Transwell chambers (all of the cells were pretreated with 100 μM IFN-γ for 6 h before being added to the chambers). The chambers were placed into the wells in a 12-well plate seeded with macrophages. After incubation for 24 h, the chambers were removed using sterile forceps, and the macrophages and supernatants in the 12-well plate were collected.

4.4. Detection of Cell Proliferation Using MTT Assay

After the coculture chambers were removed, 500 μL of an MTT reaction solution was added to each well and incubated for 4 h. After the liquid was aspirated, 1 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added to each well to dissolve the formazan crystals, and the plate was shaken for 10 min at room temperature using an orbital shaker. The lysate was then transferred to a 96-well plate. Finally, the plate was read using a microplate reader to measure the absorbance of each well at an optical density (OD) of 490 nm.

4.5. Collection of Cocultured Macrophages for Real-Time PCR

The total cellular RNA was extracted using the following procedure: a total of 500 μL of TRIzol solution was added to individual wells in the 12-well plate, and after homogenization 200 μL of chloroform was added to each well. The lysate was incubated for 10 min and then centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm, 4 °C. The supernatant was collected, an equal volume of precooled isopropanol was added, and the mixture was vortexed and incubated at room temperature for 5 min before being centrifuged for 10 min at 12,000 rpm, 4 °C. Then, 1 mL of enzyme-free water containing 70% ethanol was added to wash the RNA pellet, the pellet was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min, and the supernatant was removed; the pellet was dissolved in 20 μL of sterile DEPC water at 60 °C for 15 min. Total RNA was reverse transcribed into cDNA as per the manufacturer’s protocol (Takara Reverse Transcription Kit), and the sequences of the primers are listed in Table 1. The polymerase chain reaction (PCR) used 10 μL of a reaction mixture consisting of 0.4 μL of forward and reverse primers, 2 μL of template cDNA, 0.2 μL of reference dye (50×), 2 μL of deionized water, and 5 μL of SYBR Premix Ex Taq. GAPDH was used as the internal reference, and the obtained Ct value was analyzed using the 2–ΔΔCt method. All of the real-time PCR experiments were carried out in triplicate.

Table 1. Primers for Real-Time PCR.

| target gene | forward primer sequence (5′–3′) | reverse primer sequence (5′–3′) |

|---|---|---|

| iNOS | CAAGCTGAACTTGAGCGAGGA | TTTACTCAGTGCCAGAAGCTGGA |

| TNF-α | TTGACCTCAGCGCTGAGTTG | CCTGTAGCCCACGTCGTAGC |

| CCL17 | GACGACAGAAGGGTACGGC | GCATCTGAAGTGACCTCATGGTA |

| CCL22 | ATTCTGTGACCATCCCCTCAT | TGTATGTGCCTCTGAACCCAC |

| Arg-1 | CCTGTGTTCCACCAGGAGAT | CCTGTGTTCCACCAGGAGAT |

| IL-10 | ACTCTTCACCTGCTCCACTG | GCTATGCTGCCTGCTCTTAC |

| IL-12 | GTGGAATGGCGTCTCTGTCT | CGGGTCTGGTTTGATGATGT |

| IL-27 | CTGTTGCTGCTACCCTTGCTT | CACTCCTGGCAATCGAGATTC |

| GAPDH | AGGTGAAGGTCGGAGTCAACG | CCTGGAAGATGGTGATGGGAT |

4.6. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

The cell supernatants from the 12-well plate were collected, and the concentrations of IL-10, CCL22, TNF-α, and IL-12 in the cell supernatants were determined according to the manufacturer’s suggested protocols (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN).

4.7. Transfection of BMSCs with TSG-6 Short Interfering RNA (siRNA) and Control siRNA

When the BMSCs from the 3rd passage reached 70% confluency, TSG-6 siRNA and control siRNA purchased from Santacruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz) were separately transfected into the cells using the RNAiMAX reagent (Lipofectamine, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA). The cells were then cultured for 24 h. The knockdown efficiency of the TSG-6 siRNA was evaluated by real-time PCR, and the amount of secreted TSG-6 was quantified using an ELISA Kit (LSBio, Seattle, WA).

4.8. Western Blot Analysis

For the western blot analysis, the BMSCs or macrophages were lysed with 500 μL of RIPA buffer (Catalog number R0278, Sigma-Aldrich) with protease and phosphatase inhibitors, and then the protein lysates were denatured at 95 °C for 10 min. The protein was subjected to electrophoresis using SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and then the proteins from the gel were transferred to PVDF membranes using the Bio-Rad transfer system. The PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature and washed three times in TBST for 15 min each, then the PVDF membrane was incubated with the primary antibodies at 4 °C overnight, followed by secondary antibody incubation at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was finally washed with TBST three times for 10 min each, and an ECL luminescence kit was used for the detection. The dilution ratios of the primary antibodies were as follows: anti-RUNX2 antibody (1:1000 dilution, ab76956, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-OCN antibody (1:1000 dilution, ab93876, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), anti-BSP antibody (1:1000 dilution, PA5-79424, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Carlsbad, California), anti-Arg-1 antibody (1:1000 dilution, A4923, ABclonal, Cambridge, MA), anti-iNOS antibody (1:1000 dilution, ab15323, Abcam, Cambridge, MA), and anti-GAPDH antibody (1:1000 dilution, ab9485, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). The secondary antibodies (ab205719 and ab205718, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) were diluted at a ratio of 1:5000. All of the western blot experiments were performed in triplicate.

4.9. Statistical Analyses

Calculations were performed using SPSS 22.0. The experimental data are represented as means ± SD. Statistical comparisons were made using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Tukey’s post hoc test, where p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

HFC upregulates TSG-6 expression by BMSCs, and TSG-6 exerts immunomodulatory effects on macrophages by inhibiting TNF-α and IL-12 expression and secretion, and by promoting IL-10 and CCL22 expression and secretion. The data from this study demonstrated that osteogenically differentiated BMSCs induced by HFC retain their original immunoregulatory functions. Therefore, this study provides scientific guidance for the application of HFC in tissue engineering and stem cell therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China [grant number 31600760]. We thank Nanping Wang at the Shanghai Fisheries Research Institute for suppling the hydrolyzed fish collagen.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- BMSCs

bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells

- HFC

hydrolyzed fish collagen

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-α

- siRNA

short interfering RNA

- Arg-1

arginase-1

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- OM

osteogenic medium

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- OD

optical density

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IL-12

interleukin-12

- IL-27

interleukin-27

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- RUNX2

Runt-related transcription factor 2

- OCN

osteocalcin

- BSP

bone sialoprotein

- TSG-6

tumor necrosis factor-stimulated gene-6

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Molina E. R.; Smith B. T.; Shah S. R.; Shin H.; Mikos A. G. Immunomodulatory properties of stem cells and bioactive molecules for tissue engineering. J. Controlled Release 2015, 219, 107–118. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2015.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan T.; Zhang L.; Feng L.; Fan H.; Zhang X. Chondrogenic differentiation and immunological properties of mesenchymal stem cells in collagen type I hydrogel. Biotechnol. Prog. 2010, 26, 1749–1758. 10.1002/btpr.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rocca G.; Lo Iacono M.; Corsello T.; Corrao S.; Farina F.; Anzalone R. Human Wharton’s jelly mesenchymal stem cells maintain the expression of key immunomodulatory molecules when subjected to osteogenic, adipogenic and chondrogenic differentiation in vitro: new perspectives for cellular therapy. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2013, 8, 100–113. 10.2174/1574888X11308010012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer P.; Kornacker M.; Mehlhorn A.; Seckinger A.; Vohrer J.; Schmal H.; Kasten P.; Eckstein V.; Südkamp N. P.; Krause U. Comparison of immunological properties of bone marrow stromal cells and adipose tissue-derived stem cells before and after osteogenic differentiation in vitro. Tissue Eng. 2007, 13, 111–121. 10.1089/ten.2006.0114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Gareta E.; Coathup M. J.; Blunn G. W. Osteoinduction of bone grafting materials for bone repair and regeneration. Bone 2015, 81, 112–121. 10.1016/j.bone.2015.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Sun J. Potential application of hydrolyzed fish collagen for inducing the multidirectional differentiation of rat bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Biomacromolecules 2014, 15, 436–443. 10.1021/bm401780v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Sun J. Hydrolyzed tilapia fish collagen induces osteogenic differentiation of human periodontal ligament cells. Biomed. Mater. 2015, 10, 065020 10.1088/1748-6041/10/6/065020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapouri-Moghaddam A.; Mohammadian S.; Vazini H.; Taghadosi M.; Esmaeili S. A.; Mardani F.; Seifi B.; Mohammadi A.; Afshari J. T.; Sahebkar A. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J. Cell. Physiol. 2018, 233, 6425–6440. 10.1002/jcp.26429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayan V.; Yannarelli G.; Billia F.; Filomeno P.; Wang X. H.; Davies J. E.; Keating A. Mesenchymal stromal cells mediate a switch to alternatively activated monocytes/macrophages after acute myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2011, 106, 1299–1310. 10.1007/s00395-011-0221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swartzlander M. D.; Blakney A. K.; Amer L. D.; Hankenson K. D.; Kyriakides T. R.; Bryant S. J. Immunomodulation by mesenchymal stem cells combats the foreign body response to cell-laden synthetic hydrogels. Biomaterials 2015, 41, 79–88. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C.; Liu X.; Xue Y.; Ding T. T.; Sun J. Hydrolyzed tilapia fish collagen modulates the biological behavior of macrophages under inflammatory conditions. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 30727–30736. 10.1039/C5RA02355F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Akdis C. A.; Joss A.; Akdis M.; Faith A.; Blaser K. A molecular basis for T cell suppression by IL-10: CD28-associated IL-10 receptor inhibits CD28 tyrosine phosphorylation and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase binding. FASEB J. 2000, 14, 1666–1668. 10.1096/fj.99-0874fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheu S.; Ali S.; Ruland C.; Arolt V.; Alferink J. The C-C Chemokines CCL17 and CCL22 and Their Receptor CCR4 in CNS Autoimmunity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017, 18, E2306 10.3390/ijms18112306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F.; Pétrilli V.; Mayor A.; Tardivel A.; Tschopp J. Gout-associated uric acid crystals activate the NALP3 inflammasome. Nature 2006, 440, 237–241. 10.1038/nature04516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behzadi P.; Behzadi E.; Ranjbar R. IL-12 Family Cytokines: General Characteristics, Pathogenic Microorganisms, Receptors, and Signalling Pathways. Acta Microbiol. Immunol. Hung. 2016, 63, 1–25. 10.1556/030.63.2016.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahbazi M. A.; Sedighi M.; Bauleth-Ramos T.; Kant K.; Correia A.; Poursina N.; Sarmento B.; Hirvonen J.; Santos H. A. Targeted Reinforcement of Macrophage Reprogramming Toward M2 Polarization by IL-4-Loaded Hyaluronic Acid Particles. ACS Omega 2018, 3, 18444–18455. 10.1021/acsomega.8b03182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiratori H.; Feinweber C.; Luckhardt S.; Wallner N.; Geisslinger G.; Weigert A.; Parnham M. J. An in vitro test system for compounds that modulate human inflammatory macrophage polarization. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2018, 833, 328–338. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2018.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.; Cha J.; Jang M.; Kim P. Hyaluronic acid-based extracellular matrix triggers spontaneous M2-like polarity of monocyte/macrophage. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 2264–2271. 10.1039/C9BM00155G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shayan M.; Padmanabhan J.; Morris A. H.; Cheung B.; Smith R.; Schroers J.; Kyriakides T. R. Nanopatterned bulk metallic glass-based biomaterials modulate macrophage polarization. Acta Biomater. 2018, 75, 427–438. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski K. A.; Amici S. A.; Webb L. M.; Ruiz-Rosado J. D.; Popovich P. G.; Partida-Sanchez S.; Guerau-de-Arellano M. Novel Markers to Delineate Murine M1 and M2 Macrophages. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0145342 10.1371/journal.pone.0145342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjea A.; LaPointe V. L.; Alblas J.; Chatterjea S.; van Blitterswijk C. A.; de Boer J. Suppression of the immune system as a critical step for bone formation from allogeneic osteoprogenitors implanted in rats. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2014, 18, 134–142. 10.1111/jcmm.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrukhov O.; Behm C.; Blufstein A.; Rausch-Fan X. Immunomodulatory properties of dental tissue-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Implication in disease and tissue regeneration. World J. Stem Cells. 2019, 11, 604–617. 10.4252/wjsc.v11.i9.604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Zhang S.; Gu S.; Sang L.; Dai C. Mesenchymal stem cells recruit macrophages to alleviate experimental colitis through TGFβ1. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 35, 858–865. 10.1159/000369743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J.; Chen B.; Lv T.; Liu X.; Fu X.; Wang Q.; Yan L.; Kang N.; Cao Y.; Xiao R. Bone Marrow Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Engineered Cartilage Ameliorates Polyglycolic Acid/Polylactic Acid Scaffold-Induced Inflammation Through M2 Polarization of Macrophages in a Pig Model. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016, 5, 1079–1089. 10.5966/sctm.2015-0263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko J. H.; Lee H. J.; Jeong H. J.; Kim M. K.; Wee W. R.; Yoon S. O.; Choi H.; Prockop D. J.; Oh J. Y. Mesenchymal stem/stromal cells precondition lung monocytes/macrophages to produce tolerance against allo- and autoimmunity in the eye. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113, 158–163. 10.1073/pnas.1522905113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop D. J. Concise review: two negative feedback loops place mesenchymal stem/stromal cells at the center of early regulators of inflammation. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 2042–2046. 10.1002/stem.1400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher M.; Mattern C.; Ghoumari A.; Oudinet J. P.; Liere P.; Labombarda F.; Sitruk-Ware R.; De Nicola A. F.; Guennoun R. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Prog. Neurobiol. 2014, 113, 6–39. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madrigal M.; Rao K. S.; Riordan N. H. A review of therapeutic effects of mesenchymal stem cell secretions and induction of secretory modification by different culture methods. J. Transl. Med. 2014, 12, 260. 10.1186/s12967-014-0260-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinoi E.; Fujimori S.; Wang L.; Hojo H.; Uno K.; Yoneda Y. Nrf2 negatively regulates osteoblast differentiation via interfering with Runx2-dependent transcriptional activation. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 18015–18024. 10.1074/jbc.M600603200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth S. L.; Centi A.; Smith S. R.; Gundberg C. The role of osteocalcin in human glucose metabolism: marker or mediator?. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 2013, 9, 43–55. 10.1038/nrendo.2012.201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olmos Buitrago J.; Perez R. A.; El-Fiqi A.; Singh R. K.; Kim J. H.; Kim H. W. Core–shell fibrous stem cell carriers incorporating osteogenic nanoparticulate cues for bone tissue engineering. Acta Biomater. 2015, 28, 183–192. 10.1016/j.actbio.2015.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosurgi L.; Cao Y. G.; Cabeza-Cabrerizo M.; Tucci A.; Hughes L. D.; Kong Y.; Weinstein J. S.; Licona-Limon P.; Schmid E. T.; Pelorosso F.; Gagliani N.; Craft J. E.; Flavell R. A.; Ghosh S.; Rothlin C. V. Macrophage function in tissue repair and remodeling requires IL-4 or IL-13 with apoptotic cells. Science 2017, 356, 1072–1076. 10.1126/science.aai8132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heo J. S.; Choi Y.; Kim H. O. Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cells Promote M2 Macrophage Phenotype through Exosomes. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 7921760 10.1155/2019/7921760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um S.; Kim H. Y.; Lee J. H.; Song I. S.; Seo B. M. TSG-6 secreted by mesenchymal stem cells suppresses immune reactions influenced by BMP-2 through p38 and MEK mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Cell Tissue Res. 2017, 368, 551–561. 10.1007/s00441-017-2581-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stijn C. M. W.; Kim J.; Lusis A. J.; Barish G. D.; Tangirala R. K. Macrophage polarization phenotype regulates adiponectin receptor expression and adiponectin anti-inflammatory response. FASEB J. 2015, 29, 636–649. 10.1096/fj.14-253831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison-Kotler E.; Marshall W. S.; García-Gareta E. Sources of Collagen for Biomaterials in Skin Wound Healing. Bioengineering 2019, 6, 56. 10.3390/bioengineering6030056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu L. H.; Lai W. F.; Chang S. F.; Wong C. C.; Fan C. Y.; Fang C. L.; Tsai Y. H. The effect of type II collagen on MSC osteogenic differentiation and bone defect repair. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 2680–2691. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley C.; Wu B.; Tawil B. The effect of fibrinogen, collagen type I, and fibronectin on mesenchymal stem cell growth and differentiation into osteoblasts. Tissue Eng., Part A 2013, 19, 1416–1423. 10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Su W.; Ma X.; Zhang H.; Sun Z.; Li X. Comparison of the osteogenic capability of rat bone mesenchymal stem cells on collagen, collagen/hydroxyapatite, hydroxyapatite and biphasic calcium phosphate. Regener. Biomater. 2018, 5, 93–103. 10.1093/rb/rbx018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang T.; Heng S.; Huang X.; Zheng L.; Kai D.; Loh X. J.; Zhao J. Biomimetic Poly(Poly(ε-caprolactone)-Polytetrahydrofuran urethane) Based Nanofibers Enhanced Chondrogenic Differentiation and Cartilage Regeneration. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2019, 15, 1005–1017. 10.1166/jbn.2019.2748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]