Abstract

Microporous crystalline porous materials such as zeolites, metal–organic frameworks, and zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) have potential use for separating water/alcohol mixtures in fixed bed adsorbers and membrane permeation devices. For recovery of alcohols present in dilute aqueous solutions, the adsorbent materials need to be hydrophobic in order to prevent the ingress of water. The primary objective of this article is to investigate the accuracy of ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST) for prediction of water/alcohol mixture adsorption in hydrophobic adsorbents. For this purpose, configurational bias Monte Carlo (CBMC) simulations are used to determine the component loadings for adsorption equilibrium of water/methanol and water/ethanol mixtures in all-silica zeolites (CHA, DDR, and FAU) and ZIF-8. Due to the occurrence of strong hydrogen bonding between water and alcohol molecules and attendant clustering, IAST fails to provide quantitative estimates of the component loadings and the adsorption selectivity. For a range of operating conditions, the water loading in the adsorbed phase may exceed that of pure water by one to two orders of magnitude. Furthermore, the occurrence of water–alcohol clusters moderates size entropy effects that prevail under pore saturation conditions. For quantitative modeling of the CBMC, simulated data requires the application of real adsorbed solution theory by incorporation of activity coefficients, suitably parameterized by the Margules model for the excess Gibbs free energy of adsorption.

1. Introduction

Due to the formation of azeotropes, distillation of a water/alcohol mixture is energy-intensive. The use of membrane pervaporation devices in hybrid distillation-membrane processing schemes offers energy-efficient alternatives in production of purified alcohols.1−5 The membranes may be constructed as thin films of zeolites (e.g., CHA,3,6 DDR,7,8 LTA,9 MFI10,11) or zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs).12 The permeation selectivity of membrane constructs, Sperm, is dictated by a combination of the adsorption selectivity, Sads, and the diffusion selectivity, Sdiff.13−15 The alcohol/water adsorption selectivity, Sads, is defined by

| 1 |

where q1 and q2 are the molar loadings of the water and alcohol, respectively, in the adsorbed phase in equilibrium with a bulk fluid phase mixture with partial fugacities f1 and f2 and composition y1 = 1 – y2. Due to the narrow 3.8–4.1 Å window sizes of CHA, DDR, and LTA zeolites, the diffusion selectivity, Sdiff, favors water transport.5,16 For water-selective dehydration of feed streams of near-azeotropic composition, hydrophilic LTA-4A (= NaA) membranes are applied on a commercial scale.17 Hydrophobic membranes made of materials such as all-silica MFI and ZIF-8 are suitable for enrichment of feed mixtures that are dilute in alcohol.11,18

In the production of bioalcohols by fermentation of biomass, the desired products such as bioethanol and biobutanol are available in low concentrations in the fermentation broth; consequently, distillation separations are infeasible. One separation strategy is to use fixed bed adsorption devices packed with hydrophobic microporous materials, such as all-silica MFI (also called silicalite-1), ZIF-8, ZIF-71, and MOFs.18−22 The separation efficacy of fixed bed adsorbers is dictated by a combination of mixture adsorption equilibrium and intracrystalline diffusion of guest molecules.

For estimation of the component loadings q1 and q2 and selectivity, Sads, it is common to use ideal adsorbed solution theory (IAST)23 that requires the unary isotherm data as inputs. The IAST approach has been used in a number of published works for evaluating and screening adsorbents for a wide variety of mixture separations.18,24−29

For adsorption of water/alcohol mixtures in all-silica MFI zeolite, molecular simulations have established the occurrence of molecular clusters engendered by hydrogen bonding between water and alcohol molecules.11,30−37 Such molecular clustering results in significantly enhanced water ingress that is not anticipated by IAST.11,31 For adsorption of mixtures of water/ethanol mixtures of constant composition, y1, in MFI zeolite, the molecular simulation data of Gómez-Álvarez et al.33 also showed that the ethanol/water selectivity decreases with increasing pore occupancy.

The primary objective of this article is to demonstrate that the enhanced water ingress, as evidenced by MFI zeolite in published works, is a common characteristic of other all-silica zeolites and also hydrophobic ZIFs. Toward this end, configurational bias Monte Carlo (CBMC) simulations of water/methanol and water/ethanol mixture adsorption equilibrium were performed for three all-silica zeolites (CHA, DDR, and FAU) and ZIF-8. The secondary objective is to elucidate the reasons behind the failure of the IAST to provide quantitatively accurate predictions of mixture adsorption. The tertiary objective is to show how the nonidealities in mixture adsorption can be quantified and modeled.

The CBMC simulation methodology used in this article follows published works.14,38−41 All host materials are considered to be rigid in the simulations, performed at a temperature T = 300 K. The force field implementation follows earlier publications.7,35,37,42 Water is modeled using the Tip5pEw potential.43 The alcohols are described with the TraPPE force field.44 Intramolecular potentials are included to describe the flexibility of alcohols, while the water molecules are kept rigid. The bond lengths are fixed for all molecules. Bond bending potentials are considered for methanol and ethanol, and a torsion potential is used for ethanol.44 Further details, including force field parameters, are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. IAST Prescriptions and Origins of Nonidealities

In the Myers–Prausnitz development of IAST,23 the partial fugacities in the bulk fluid mixture are related to the mole fractions xi in the adsorbed phase mixture

| 2 |

by the analogue of Raoult’s law for vapor–liquid equilibrium, i.e.

| 3 |

where Pi0 is the pressure for sorption of every component i, which yields the same spreading pressure, π for each of the pure components, as that for the mixture:

| 4 |

In eq 4, A represents

the surface area per kilogram of framework and qi0(f) is the pure component adsorption isotherm. Since

the surface area A is not directly accessible from

experimental data, the adsorption potential πA/RT, with the unit mol kg–1, serves

as a convenient and practical proxy for the spreading pressure π.

For binary mixture adsorption, each of the equalities on the right-hand

side of eq 4 must be

satisfied. These constraints may be solved using a suitable equation

solver to yield the set of values of P1, and P20, both of

which satisfy eq 4. The

corresponding values of the integrals using these as upper limits

of integration must yield the same value of  for each component; this ensures that the

obtained solution is the correct one.

for each component; this ensures that the

obtained solution is the correct one.

The applicability of the Raoult law analog, eq 3, mandates that all of the adsorption sites within the microporous material are equally accessible to each of the guest molecules, implying a homogeneous distribution of guest adsorbates within the pore landscape, with no preferential locations of any guest species.45,46 This prescription is fulfilled for adsorption of mixtures of nonpolar guest molecules in relatively “open” host materials. As an illustration, Figure 1a compares IAST estimates of Sads with CBMC data for equimolar CH4/C3H8 mixtures in cation-exchanged NaX zeolite. Noteworthily, IAST quantitatively predicts the decrease in C3H8/CH4 selectivity with increasing bulk fugacity, ft; this decrease is engendered by entropy effects that favor the smaller methane molecule that has the higher saturation capacity.24,47 However, for adsorption of CO2/C3H8 mixtures in NaX zeolite, IAST overestimates the CO2/C3H8 selectivity because the CO2 molecules tend to congregate around the Na+ cations, thereby reducing the competition between the two guest species;45,46,48 see Figure 1b.

Figure 1.

CBMC simulation data for (a) CH4/C3H8 and (b) CO2/C3H8 mixture adsorption in NaX zeolite (106 Si, 86 Al, 86 Na+, Si/Al = 1.23) at 300 K, with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The dashed lines are the IAST calculations of the component loadings. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

A further key assumption of IAST is that the enthalpies and surface

areas of the adsorbed molecules do not change upon mixing.23 If the total mixture loading is qt, the area covered by the adsorbed mixture is  with a unit of m2 (mole

mixture)−1. Therefore, the assumption of no surface

area change

due to mixture adsorption translates as

with a unit of m2 (mole

mixture)−1. Therefore, the assumption of no surface

area change

due to mixture adsorption translates as

| 5 |

The occurrence of molecular clustering due to hydrogen bonding should be expected to invalidate the use of eq 5 in the IAST calculations of qt.

2.2. Evidence of Hydrogen Bonding for Water/Alcohol Mixture Adsorption

In order to demonstrate the occurrence of hydrogen bonding in water/methanol and water/ethanol mixtures, CBMC simulation data on the spatial locations of the guest molecules were sampled to determine the O···H distances of various pairs of molecular distances. By sampling a total of 106 simulation steps, the radial distribution functions (RDFs) of O···H distances were determined for water–water, water–alcohol, and alcohol–alcohol pairs. Figure 2a shows the RDF of O···H distances for molecular pairs of water(1)/methanol(2) mixture adsorption in CHA zeolite at 300 K. The partial fugacities of components 1 and 2 are f1 = 2.5 kPa and f2 = 7.5 kPa. We note that the first peaks in the RDFs occur at a distance less than 2 Å, which is characteristic of hydrogen bonding.35,49 The heights of the first peaks are a direct reflection of the degree of hydrogen bonding between the molecular pairs. We may conclude therefore that for water/methanol mixtures, the degree of H bonding between water–methanol pairs is significantly larger, by about an order of magnitude, than for water–water and methanol–methanol pairs. An analogous set of conclusions can be drawn for water/ethanol mixtures, for which the RDF data are presented in Figure 2b: that is, the degree of H bonding between water–ethanol pairs is larger than for water–water and ethanol–ethanol pairs. For comparison purposes, the RDF data for adsorption of methanol/ethanol mixtures are shown in Figure 2c. The magnitudes of the first peaks for methanol–ethanol, methanol–methanol, and ethanol–ethanol pairs are significantly lower than those of the water–alcohol peaks in Figure 2a,b. Therefore, the H-bonding effects should be expected to be of lesser importance for methanol/ethanol mixture adsorption in CHA than for water/methanol and water/ethanol mixtures.

Figure 2.

RDF of O···H distances for molecular pairs of (a) water(1)/methanol(2), (b) water(1)/ethanol(2), and (c) methanol(1)/ethanol(2) mixture adsorption in CHA zeolite at 300 K. For all three sets of mixtures, the partial fugacities of components 1 and 2 are f1 = 2.5 kPa and f2 = 7.5 kPa. The y-axes are normalized in the same manner, and therefore, the magnitudes of the first peaks are a direct reflection of the degree of hydrogen bonding between the molecular pairs.

Analogous results are obtained for the RDFs in DDR, MFI, and ZIF-8; see Figures S15–S22 of the Supporting Information.

2.3. Water/Alcohol Mixture Adsorption; CBMC vs IAST

Figure 3a compares CBMC simulations of unary water isotherms in different microporous host materials, plotted as a function of the fugacity of water in the bulk fluid phase. The plot clearly shows the difference between various hydrophobic hosts (all-silica zeolites, ZIF-8, ZIF-71) and hydrophilic host CuBTC; for hydrophobic hosts, the bulk fluid phase fugacity needs to be at least 1 kPa before significant water uptake is realized.

Figure 3.

(a) Comparison o CBMC simulations of unary water isotherms in different microporous host materials, plotted as a function of the fugacity of water in the bulk fluid phase. (b) CBMC simulation data for water(1)/ethanol(2) mixture adsorption in DDR at 300 K with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The component loadings in mixture (filled symbols) are compared with CBMC simulations of unary isotherms (open symbols), both plotted as a function of the partial fugacity fi in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The dashed lines are the IAST calculations of the component loadings. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication. (c) IAST calculations of the component loadings for ethanol/1-butanol mixture adsorption in ZIF-8 are compared with the unary isotherm data fits reported by Claessens et al.20

Two types of mixture adsorption simulation campaigns were conducted. In campaign A, the bulk fluid phase mixture is equimolar, f1 = f2, and the bulk fluid phase fugacity ft = f1 + f2 was varied over a wide range from the Henry regime of adsorption, ft = 1 Pa, to near pore saturation conditions, typically ft>50 kPa. In campaign B, the bulk fluid phase fugacity ft = f1 + f2 was held at a constant value of 10 kPa, and the bulk fluid phase mixture composition was varied, 0<y1<1. The obtained results for both sets of campaigns in the different host materials are presented in Figures S24–S50 of the Supporting Information.

As an illustration, Figure 3b presents the CBMC data for campaign A of water/ethanol mixture adsorption in DDR. The component loadings in the adsorbed mixture (filled symbols) are compared with CBMC simulations of unary isotherms (open symbols) at the same partial fugacity, fi, in the bulk phase. For fi < 10 kPa, the ethanol loading in the mixture is practically identical to that of the unary isotherm while the water loading in the mixture is considerably larger than that of pure water. For fi < 10 kPa, the IAST calculations (indicated by the dashed lines) do not anticipate the substantially enhanced water ingress from the mixture because the influence of molecular clustering is not catered for in the theoretical development of IAST. From a close examination of Figure 3b, it is also noteworthy that water loading from the IAST calculations also exceeds the unary water loading, albeit to a minor extent as indicated by the shaded area. This increase in the loading of the lighter component in the mixture is a common characteristic of mixtures in which the lighter component (with higher saturation capacity) exhibits a much steeper unary isotherm than that of the heavier component (with lower saturation capacity). For adsorption of ethanol/1-butanol mixtures in ZIF-8, the experiments of Claessens et al.20 demonstrated that the ethanol loading in the mixture may exceed that of pure ethanol over a certain limited range of bulk fugacities; see Figure 3b. These authors have dubbed this phenomenon as “co-operative adsorption” and have further demonstrated that IAST is capable of describing such effects. By contrast, for water/ethanol adsorption in DDR, the CBMC data for enhancement in the water loading far exceeds the IAST value. To put it another way, hydrogen bonding effects tend to significantly amplify the “co-operative adsorption” effect.

By dividing the CBMC data on water loadings in the mixture by the corresponding loading determined from the unary water isotherm, the enhancement in the water loading can be determined. These data are summarized in Figure 4a,b for water/methanol and water/ethanol mixtures in different host materials; the data sets include those for hydrophilic CuBTC and hydrophobic ZIF-71, culled from the published literature.50−52 For a range of bulk fluid phase fugacities, the enhancement in the water loadings may range from 10 to 500.

Figure 4.

Enhancement of water loading in (a) water(1)/methanol(2) and (b) water(1)/ethanol(2) mixtures, determined from CBMC simulations for mixture adsorption in various host materials at 300 K with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The x axis represents the bulk fluid phase fugacity ft = f1+ f2. Also included are the data for ZIF-7152 and CuBTC.50,51 Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

Figure 5a,b summarizes the CBMC data for methanol/water and ethanol/water selectivities, Sads, in different host materials. In all cases, the selectivity reverses in favor of water as pore saturation conditions are approached, typically for ft > 50 kPa. Water is preferentially adsorbed due to size entropy effects that favor the smaller molecule due to improved packing within the pore landscape.24,47 For hydrophobic all-silica CHA and FER zeolites, the experiments of Arletti et al.53 and Confalonieri et al.54 provide confirmation that adsorption of water/ethanol mixtures is water-selective at high pore occupancies.

Figure 5.

CBMC simulation data for alcohol/water adsorption selectivity for (a) water(1)/methanol(2) and (b) water(1)/ethanol(2) mixtures in various host materials at 300 K with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The x axis represents the bulk fluid phase fugacity ft = f1+ f2. Also included are the data for ZIF-7152 and CuBTC.50,51 Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

In Figure 6a, the CBMC data for ethanol/water selectivity in DDR, Sads, are compared with IAST estimates. IAST takes due account of entropy effects and selectivity reversals, but the quantitative agreement with the CBMC data is not adequate because the IAST development does not account for molecular clustering; IAST essentially portrays an exaggerated influence of entropy effects. For ft < 20 kPa, Sads is overestimated because IAST ignores water uptake induced by hydrogen bonding. For ft > 50 kPa, cluster formation tends to moderate entropy effects, causing the IAST calculations for alcohol/water selectivity to fall below those determined from CBMC. Precisely analogous results are obtained for deviations of IAST from CBMC simulation results for water/ethanol/ZIF-8 and water/methanol/CHA; see Figure 6b,c. Comparisons of the CBMC data Sads with IAST estimates for all investigated mixture/host combinations are available in Figures S24–S50 of the Supporting Information. They all show common characteristics that are illustrated in Figure 6a–c for three different cases.

Figure 6.

CBMC simulation data for the alcohol/water selectivity for water(1)/alcohol(2) mixture adsorption in (a) DDR, (b) ZIF-8, and (c) CHA at 300 K with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture. The dashed lines are the IAST calculations of the component loadings. The continuous solid lines are the RAST calculations using the Margules model. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

Molecular dynamics simulation data for mixture diffusion have shown that cluster formation tends to reduce the diffusivities of both water and alcohol molecules;5,33,35,42,55−58 this mutual slowing-down phenomena is a corollary to the moderation of entropy effects in mixture adsorption.

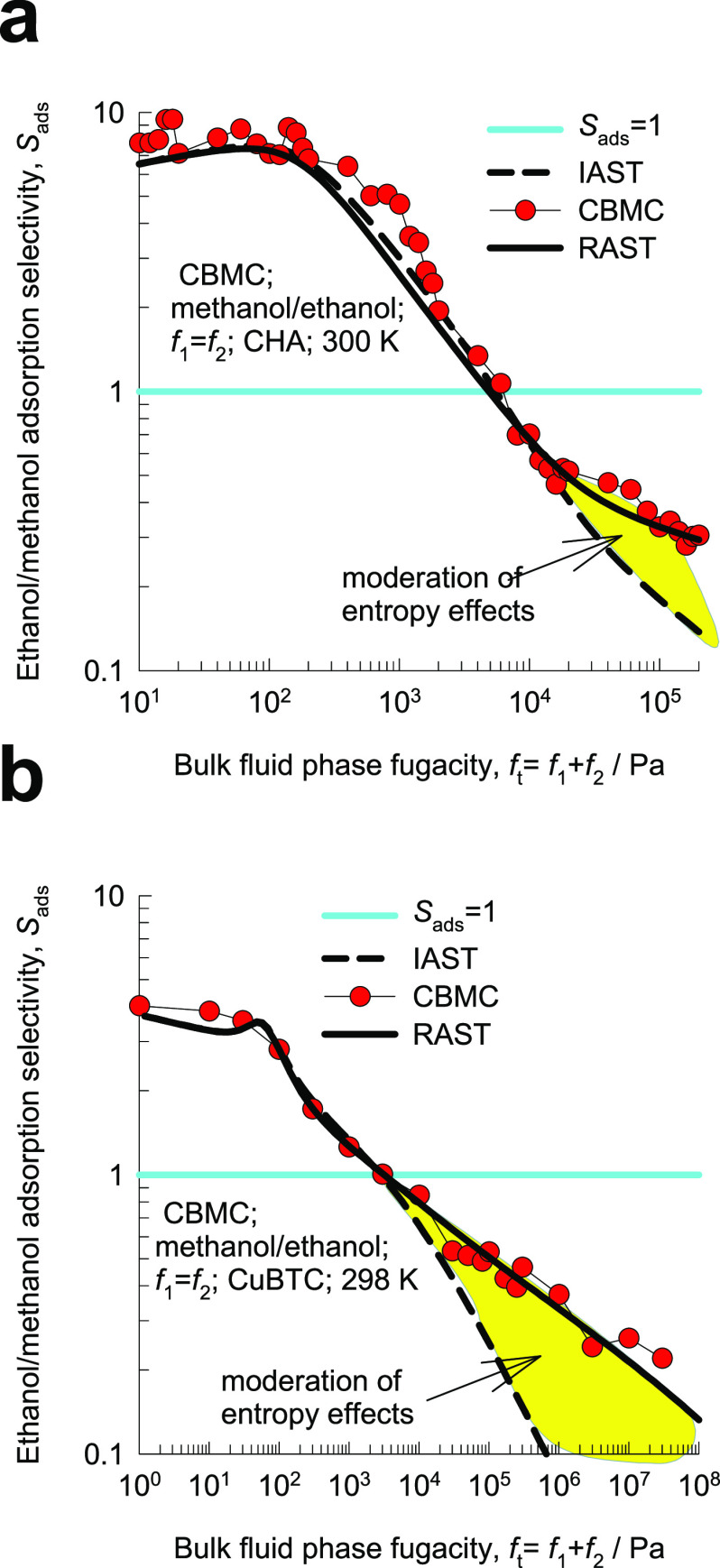

For methanol/ethanol adsorption in CHA, Figure 7a compares the CBMC simulation data for Sads with IAST estimates. There is good agreement between the two data sets for bulk phase fugacities ft < 10 kPa because hydrogen bonding effects are smaller than for water/alcohol systems, as witnessed in Figure 2. The entropy-driven selectivity reversal in favor of methanol is correctly predicted by IAST. For ft > 50 kPa, as pore saturation conditions are approached, IAST tends to underestimate the ethanol/methanol selectivity due to moderation of entropy effects as a result of some degree of molecular clustering that prevail at pore saturation. Analogous results are obtained for methanol/ethanol adsorption in hydrophilic CuBTC; see Figure 7b.

Figure 7.

CBMC simulation data for ethanol/methanol adsorption selectivity for methanol(1)/ethanol(2) mixtures with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in (a) CHA and (b) CuBTC. The x axis represents the bulk fluid phase fugacity ft = f1+ f2. The dashed lines are the IAST calculations of the component loadings. The continuous solid lines are the RAST calculations using the Margules model. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

Figure 8a presents CBMC data for ethanol/water selectivity in DDR zeolite for campaign B, in which the bulk fluid composition is varied. The CBMC data show that for water-rich mixtures, y1>0.5, the adsorption is ethanol-selective; this is desired of adsorbents in recovery of bioethanol from fermentation broths. However, for feed mixtures that are richer in ethanol, y1<0.5, the adsorption is water-selective; this is a desirable feature for use of DDR in membrane constructs for water-selective pervaporation processes.7 The narrow 8-ring windows of DDR, with dimensions of 3.65 Å × 4.37 Å, ensure that the diffusion selectivity Sdiff also favors water.16,35,37,42 IAST (dashed line) anticipates ethanol-selective adsorption over the entire range of y1. Analogous results are obtained for water/alcohol mixture adsorption in CHA; see Figure 8b. Adsorption of alcohol-rich feed mixtures in CHA is water-selective; therefore, CHA membranes are used for purification of alcohols by membrane pervaporation because diffusion through 3.8 Å × 4.2 Å 8-ring windows of CHA also favors water.6,16,35,37,42

Figure 8.

(a) Comparisons of CBMC data for Sads with IAST (dashed line) and RAST calculations (continuous solid line) for water/ethanol adsorption in DDR for ft = f1+ f2 = 10 kPa. (b) CBMC simulation data for alcohol/water adsorption selectivities, Sads, in CHA and DDR zeolites at 300 K; the bulk fluid phase is maintained at a constant fugacity ft = f1+ f2 = 10 kPa, and the mole fraction of water in the bulk mixture y1 is varied. (c) Enhancement of water loading for water/alcohol mixture adsorption in CHA and DDR for ft = f1+ f2 = 10 kPa. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

For rationalization of these results, Figure 8c plots the enhancement in the water loading as a function of y1. We note that for dilute aqueous alcohol solutions with y1<0.2, the enhancement in the water loading is about one to two orders of magnitude. Each water molecule has a greater probability of forming O···H bonds with alcohols due to the preponderance of alcohol molecules that are present.

There is evidence that molecular clustering effects induced by hydrogen bonding also cause failure of IAST to provide quantitative description of adsorption equilibrium for methanol/benzene, ethanol/benzene, acetone/benzene, methanol/n-hexane, 1-propanol/toluene, and 1-butanol/p-xylene mixtures in CuBTC and cation-exchanged zeolites;36,50,51,59−61 detailed analyses are provided in Figures S37–S44 and S55–S57.

2.4. RAST Modeling of Thermodynamic Nonidealities

To account for nonideality effects in mixture adsorption, engendered by hydrogen bonding, we need to introduce activity coefficients γi into eq 3

| 6 |

The implementation of the activity coefficients is termed as real adsorbed solution theory (RAST). Following the approaches of Myers, Talu, and Sieperstein,62−64 we model the excess Gibbs free energy for binary mixture adsorption as follows

| 7 |

A variety of models such as Regular solution,64 Wilson,45,46,48 NRTL,65 SPD,63 and Margules11 have been used for describing the composition dependence of γi. Here, we employ the Margules model, which is particularly suitable for water/alcohol mixtures,11 expressed in the following form

|

8 |

In eq 8, C is a constant with the unit kg mol–1. The introduction

of  imparts the correct limiting behaviors

imparts the correct limiting behaviors  for the activity coefficients in the Henry

regime,

for the activity coefficients in the Henry

regime,  . As pore saturation conditions

are approached,

this correction factor tends to unity

. As pore saturation conditions

are approached,

this correction factor tends to unity  .

.

For calculation of the total mixture loading, eq 5 is replaced by

| 9 |

The parameters A12, A21, C can be fitted to match the CBMC data on mixture adsorption. Further details of the RAST model calculations, fitting methodology, and values of the fitted Margules parameters are provided in the Supporting Information. As an illustration, Figure 9a presents RAST calculations of activity coefficients γi for water/ethanol adsorption in DDR zeolite, plotted as a function of the adsorption potential, πA/RT. The water activity coefficient exhibits a deep minimum for conditions under which significant enhancement in the water ingress is caused by hydrogen bonding. Analogous characteristics are found for other guest/host combinations as evidenced in Figure 9b,c in which the ratio of activity coefficients γ1/γ2 is plotted for (a) water/methanol and (b) water/ethanol mixtures in different host materials. The non-monotonic variation of γ1/γ2 with increasing πA/RT is a distinguishing and common characteristic of nonidealities induced by hydrogen bonding; in sharp contrast, for nonidealities engendered by congregation/segregation effects,45,46,48 the variation of γ1/γ2 with increasing πA/RT is monotonic; see Figure 9d. In the range of πA/RT values for which γ1/γ2<1, IAST overestimates Sads because of enhanced water ingress, indicated by the cyan shaded areas in Figure 6a–c. In the range of πA/RT values for which γ1/γ2>1, IAST underestimates Sads because of moderation of entropy effects, indicated by the yellow shaded areas in Figure 6a–c.

Figure 9.

(a) RAST calculations of activity coefficients γi for water/ethanol adsorption in DDR zeolite at 300 K with equal partial fugacities, f1 = f2, in the bulk fluid phase mixture, plotted as a function of the adsorption potential, πA/RT. (b, c) RAST calculations of the ratio of activity coefficients γ1/γ2 for (b) water/methanol and (c) water/ethanol mixtures in different hosts. (d) RAST calculations of the ratio of activity coefficients γ1/γ2 for CO2(1)/C3H8(2)/NaX, CO2(1)/CH4(2)/NaX, nC4(1)/iC4(2)/MFI, and nC6(1)/2MP(2)/MFI. Further information on the data inputs and calculations are provided in the Supporting Information accompanying this publication.

The continuous solid lines in Figures 6–8 are the RAST calculations of Sads; the improvement over the corresponding IAST estimation is significant, as should be expected.

3. Conclusions

Two different CBMC campaigns, A and B, for water/methanol and water/ethanol adsorption in hydrophobic CHA, DDR, FAU, and ZIF-8 were undertaken to investigate the accuracy of IAST estimates of component loadings and adsorption selectivities.

For CBMC simulation campaign A with equimolar bulk fluid mixtures, f1 = f2, the increase of ft = f1 + f2 from 1 Pa to about 10 kPa shows that the water ingress in the host material is significantly higher than that anticipated from the pure water isotherm data. The enhancement in the water ingress is induced by the formation of water/alcohol clusters due to hydrogen bonding; this enhanced water ingress is not anticipated by IAST. When pore saturation conditions are approached, typically ft>50 kPa, the CBMC simulations show selectivity reversal in favor of water; this selectivity reversal is driven by size entropy effects that favor water to pack more efficiently. The formation of water/alcohol clusters has a moderating influence on size entropy effects. Since molecular clustering is not recognized in the IAST development, the entropy effects are exaggerated; consequently, IAST estimates of Sads are more water-selective than that observed in the CBMC data.

The CBMC simulations following campaign B in which the bulk fluid phase fugacity is held constant, ft = 10 kPa, show that for CHA and DDR, the adsorption of alcohol-rich mixtures is water-selective and suitable for use in membrane pervaporation processes for alcohol purification. For water-rich mixture, the adsorption is alcohol-selective and therefore suitable for use in the recovery of bioalcohols.

The quantitative modeling of water/alcohol mixture adsorption in hydrophobic adsorbent requires use of RAST, with appropriate parametrization of the model to describe activity coefficients. For all hydrophobic adsorbents, the variation of the activity coefficients with the spreading pressure displays common characteristics as evidenced in Figure 9b,c.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr. Richard Baur for helpful discussion.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.0c04491.

Structural details of zeolites, MOFs, and ZIFs, details of the CBMC simulation methodology, details of the IAST and real adsorbed solution theory (RAST) calculations for mixture adsorption equilibrium, unary isotherm fits for all the guest/host combinations, Margules parameter fits for thermodynamic nonidealities, and plots of CBMC simulation data and comparisons with IAST/RAST estimates for all guest/host combinations (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Peng P.; Shi B.; Lan Y. A Review of Membrane Materials for Ethanol Recovery by Pervaporation. Sep. Sci. Technol. 2011, 46, 234–246. 10.1080/01496395.2010.504681. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Aoki K.; Sugimoto K.; Izumi K.; Inoue S.; Saito J.; Ikeda S.; Nakane T. Dehydrating performance of commercial LTA zeolite membranes and application to fuel grade bio-ethanol production by hybrid distillation/vapor permeation process. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2008, 115, 184–188. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2007.10.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sato K.; Sugimoto K.; Shimotsuma N.; Kikuchi T.; Kyotani T.; Kurata T. Development of practically available up-scaled high-silica CHA-type zeolite membranes for industrial purpose in dehydration of N-methyl pyrrolidone solution. J. Membr. Sci. 2012, 409-410, 82–95. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.03.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Highlighting Thermodynamic Coupling Effects in Alcohol/Water Pervaporation across Polymeric Membranes. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 15255–15264. 10.1021/acsomega.9b02255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. Investigating the Influence of Diffusional Coupling on Mixture Permeation across Porous Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2013, 430, 113–128. 10.1016/j.memsci.2012.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y.; Abe C.; Nishioka M.; Sato K.; Nagase T.; Hanaoka T. Formation of high flux CHA-type zeolite membranes and their application to the dehydration of alcohol solutions. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 364, 318–324. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.08.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn J.; Castillo-Sanchez J. M.; Gascon J.; Calero S.; Dubbeldam D.; Vlugt T. J. H.; Kapteijn F.; Gross J. Adsorption and Diffusion of Water, Methanol, and Ethanol in All-Silica DD3R: Experiments and Simulation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2009, 113, 14290–14301. 10.1021/jp901869d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn J.; Yajima K.; Tomita T.; Gross J.; Kapteijn F. Dehydration performance of a hydrophobic DD3R zeolite membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 2008, 321, 344–349. 10.1016/j.memsci.2008.05.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pera-Titus M.; Fité C.; Sebastián V.; Lorente E.; Llorens J.; Cunill F. Modeling Pervaporation of Ethanol/Water Mixtures within ‘Real’ Zeolite NaA Membranes. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2008, 47, 3213–3224. 10.1021/ie071645b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu M.; Falconer J. L.; Noble R. D.; Krishna R. Modeling Transient Permeation of Polar Organic Mixtures through a MFI Zeolite Membrane using the Maxwell-Stefan Equations. J. Membr. Sci. 2007, 293, 167–173. 10.1016/j.memsci.2007.02.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal N.; Bai P.; Siepmann J. I.; Daoutidis P.; Tsapatsis M. Bioethanol Enrichment using Zeolite Membranes: Molecular Modeling, Conceptual Process Design and Techno-Economic Analysis. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 540, 464–476. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.06.075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yao J.; Wang H. Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework Composite Membranes and Thin Films: Synthesis and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2014, 43, 4470–4493. 10.1039/C3CS60480B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. In Silico Screening of Zeolite Membranes for CO2 Capture. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 360, 323–333. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.05.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. In silico screening of metal-organic frameworks in separation applications. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2011, 13, 10593–10616. 10.1039/c1cp20282k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Thermodynamic Insights into the Characteristics of Unary and Mixture Permeances in Microporous Membranes. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 9512–9521. 10.1021/acsomega.9b00907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. The Maxwell-Stefan Description of Mixture Diffusion in Nanoporous Crystalline Materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 185, 30–50. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2013.10.026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Morigami Y.; Kondo M.; Abe J.; Kita H.; Okamoto K. The First Large-scale Pervaporation Plant Using Tubular-type Module with Zeolite NaA Membrane. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2001, 25, 251–260. 10.1016/S1383-5866(01)00109-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K.; Lively R. P.; Zhang C.; Koros W. J.; Chance R. R. Investigating the Intrinsic Ethanol/Water Separation Capability of ZIF-8: An Adsorption and Diffusion Study. J. Phys. Chem. C 2013, 117, 7214–7225. 10.1021/jp401548b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Remi J. C. S.; Rémy T.; van Huskeren V.; van de Perre S.; Duerinck T.; Maes M.; De Vos D. E.; Gobechiya E.; Kirschhock C. E. A.; Baron G. V.; Denayer J. F. M. Biobutanol Separation with the Metal–Organic Framework ZIF-8. ChemSusChem 2011, 4, 1074–1077. 10.1002/cssc.201100261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens B.; Martin-Calvo A.; Gutiérrez-Sevillano J. J.; Dubois N.; Denayer J. F. M.; Cousin-Saint-Remi J. Macroscopic and Microscopic View of Competitive and Cooperative Adsorption of Alcohol Mixtures on ZIF-8. Langmuir 2019, 35, 3887–3896. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b03946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lively R. P.; Dose M. E.; Thompson J. A.; McCool B. A.; Chance R. R.; Koros W. J. Ethanol and Water Adsorption in Methanol-derived ZIF-71. Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 8667–8669. 10.1039/c1cc12728d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L.-H.; Xu M.-M.; Liu X.-M.; Zhao M.-J.; Li J.-R. Hydrophobic Metal–Organic Frameworks: Assessment, Construction, and Diverse Applications. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1901758. 10.1002/advs.201901758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A. L.; Prausnitz J. M. Thermodynamics of Mixed-Gas Adsorption. AIChE J. 1965, 11, 121–127. 10.1002/aic.690110125. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Separating Mixtures by Exploiting Molecular Packing Effects in Microporous Materials. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 39–59. 10.1039/C4CP03939D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motkuri R. K.; Thallapally P. K.; Annapureddy H. V. R.; Dang L. X.; Krishna R.; Nune S. K.; Fernandez C. A.; Liu J.; McGrail B. P. Separation of Polar Compounds using a Flexible Metal-Organic Framework. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 8421–8424. 10.1039/C5CC00113G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plessius R.; Kromhout R.; Ramos A. L. D.; Ferbinteanu M.; Mittelmeijer-Hazeleger M. C.; Krishna R.; Rothenberg G.; Tanase S. Highly Selective Water Adsorption in a Lanthanum Metal-Organic Framework. Chem. – Eur. J. 2014, 20, 7922–7925. 10.1002/chem.201403241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C.-T.; Jiang L.; Ye Z.-M.; Krishna R.; Zhong Z.-S.; Liao P.-Q.; Xu J.; Ouyang G.; Zhang J.-P.; Chen X.-M. Exceptional hydrophobicity of a large-pore metal-organic zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7217–7223. 10.1021/jacs.5b03727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Metrics for Evaluation and Screening of Metal-Organic Frameworks for Applications in Mixture Separations. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 16987–17004. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Screening Metal-Organic Frameworks for Mixture Separations in Fixed-Bed Adsorbers using a Combined Selectivity/Capacity Metric. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 35724–35737. 10.1039/C7RA07363A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong R.; Sandler S. I.; Vlachos D. G. Alcohol Adsorption onto Silicalite from Aqueous Solution. J. Phys. Chem. C 2011, 115, 18659–18669. 10.1021/jp205312k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bai P.; Tsapatsis M.; Siepmann J. I. Multicomponent Adsorption of Alcohols onto Silicalite-1 from Aqueous Solution: Isotherms, Structural Analysis, and Assessment of Ideal Adsorbed Solution Theory. Langmuir 2012, 28, 15566–15576. 10.1021/la303247c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh A.; DeJaco R. F.; Ohlin L.; Holmgren A.; Siepmann J. I.; Grahn M. Comparative Study of the Effect of Defects on Selective Adsorption of Butanol from Butanol/Water Binary Vapor Mixtures in Silicalite-1 Films. Langmuir 2017, 33, 8420–8427. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b02097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Álvarez P.; Noya E. G.; Lomba E.; Valencia S.; Pires J. Study of Short-Chain Alcohol and Alcohol–Water Adsorption in MEL and MFI Zeolites. Langmuir 2018, 34, 12739–12750. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b02326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farzaneh A.; Zhou M.; Potapova E.; Bacsik Z.; Ohlin L.; Holmgren A.; Hedlund J.; Grahn M. Adsorption of Water and Butanol in Silicalite-1 Film Studied with in Situ Attenuated Total Reflectance–Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy. Langmuir 2015, 31, 4887–4894. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.5b00489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. Hydrogen Bonding Effects in Adsorption of Water-alcohol Mixtures in Zeolites and the Consequences for the Characteristics of the Maxwell-Stefan Diffusivities. Langmuir 2010, 26, 10854–10867. 10.1021/la100737c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M.; Baur R. Highlighting the Origins and Consequences of Thermodynamic Nonidealities in Mixture Separations using Zeolites and Metal-Organic Frameworks. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018, 267, 274–292. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.03.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. Highlighting Pitfalls in the Maxwell-Stefan Modeling of Water-Alcohol Mixture Permeation across Pervaporation Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2010, 360, 476–482. 10.1016/j.memsci.2010.05.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. A comparison of the CO2 capture characteristics of zeolites and metal-organic frameworks. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2012, 87, 120–126. 10.1016/j.seppur.2011.11.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frenkel D.; Smit B.. Understanding Molecular Simulations: From Algorithms to Applications; 2nd Edition, Elsevier: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smit B.; Krishna R. Molecular simulations in zeolitic process design. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2003, 58, 557–568. 10.1016/S0009-2509(02)00580-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vlugt T. J. H.; Krishna R.; Smit B. Molecular Simulations of Adsorption Isotherms for Linear and Branched Alkanes and Their Mixtures in Silicalite. J. Phys. Chem. B 1999, 103, 1102–1118. 10.1021/jp982736c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. Mutual slowing-down effects in mixture diffusion in zeolites. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 13154–13156. 10.1021/jp105240c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rick S. W. A Reoptimization of the Five-site Water Potential (TIP5P) for use with Ewald Sums. J. Chem. Phys. 2004, 120, 6085–6093. 10.1063/1.1652434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B.; Potoff J. J.; Siepmann J. I. Monte Carlo Calculations for Alcohols and Their Mixtures with Alkanes. Transferable Potentials for Phase Equilibria. 5. United-Atom Description of Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Alcohols. J. Phys. Chem. B 2001, 105, 3093–3104. 10.1021/jp003882x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; Van Baten J. M. Using Molecular Simulations for Elucidation of Thermodynamic Non-Idealities in Adsorption of CO2-containing Mixtures in NaX Zeolite. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 20535–20542. 10.1021/acsomega.0c02730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; Van Baten J. M. Investigating the Non-idealities in Adsorption of CO2-bearing Mixtures in Cation-exchanged Zeolites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2018, 206, 208–217. 10.1016/j.seppur.2018.06.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Elucidation and Characterization of Entropy Effects in Mixture Separations with Micro-porous Crystalline Adsorbents. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2019, 215, 227–241. 10.1016/j.seppur.2019.01.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; Van Baten J. M. Elucidation of Selectivity Reversals for Binary Mixture Adsorption in Microporous Adsorbents. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 9031–9040. 10.1021/acsomega.0c01051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Yang X. Molecular dynamics simulation of ethanol/water mixtures for structure and diffusion properties. Fluid Phase Equilib. 2005, 231, 1–10. 10.1016/j.fluid.2005.03.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Sevillano J. J.; Calero S.; Krishna R. Selective Adsorption of Water from Mixtures with 1-Alcohols by Exploitation of Molecular Packing Effects in CuBTC. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 3658–3666. 10.1021/jp512853w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez-Sevillano J. J.; Calero S.; Krishna R. Separation of Benzene from Mixtures with Water, Methanol, Ethanol, and Acetone: Highlighting Hydrogen Bonding and Molecular Clustering Influences in CuBTC. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 20114–20124. 10.1039/C5CP02726H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalaparaju A.; Zhao X. S.; Jiang J. W. Molecular Understanding for the Adsorption of Water and Alcohols in Hydrophilic and Hydrophobic Zeolitic Metal-Organic Frameworks. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 11542–11550. 10.1021/jp1033273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arletti R.; Vezzalini G.; Quartieri S.; Di Renzo F.; Dmitriev V. Pressure-induced water intrusion in FER-type zeolites and the influence of extraframework species on structural deformations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2014, 191, 27–37. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2014.02.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Confalonieri G.; Quartieri S.; Vezzalini G.; Tabacchi G.; Fois E.; Daou T. J.; Arletti R. Differential penetration of ethanol and water in Si-chabazite: High pressure dehydration of azeotrope solution. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2019, 284, 161–169. 10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.04.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R.; van Baten J. M. Maxwell-Stefan modeling of slowing-down effects in mixed gas permeation across porous membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2011, 383, 289–300. 10.1016/j.memsci.2011.08.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Diffusion in Porous Crystalline Materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 3099–3118. 10.1039/c2cs15284c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Thermodynamically Consistent Methodology for Estimation of Diffusivities of Mixtures of Guest Molecules in Microporous Materials. ACS Omega 2019, 4, 13520–13529. 10.1021/acsomega.9b01873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna R. Using the Maxwell-Stefan formulation for Highlighting the Influence of Interspecies (1-2) Friction on Binary Mixture Permeation across Microporous and Polymeric Membranes. J. Membr. Sci. 2017, 540, 261–276. 10.1016/j.memsci.2017.06.062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuth M.; Meyer J.; Gmehling J. Vapor Phase Adsorption Equilibria of Toluene + 1-Propanol Mixtures on Y-Zeolites with Different Silicon to Aluminum Ratios. J. Chem. Eng. Data 1995, 40, 895–899. 10.1021/je00020a035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Assche T. R. C.; Duerinck T.; Van der Perre S.; Baron G. V.; Denayer J. F. M. Prediction of Molecular Separation of Polar–Apolar Mixtures on Heterogeneous Metal–Organic Frameworks: HKUST-1. Langmuir 2014, 30, 7878–7883. 10.1021/la5020253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi Y.; Iwamoto H.; Miyata N.; Asano S.; Harada M. Adsorption of l-butanol and p-xylene vapor with high silica zeolites. Sep. Technol. 1995, 5, 23–34. 10.1016/0956-9618(94)00101-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talu O.; Myers A. L. Rigorous Thermodynamic Treatment of Gas Adsorption. AIChE J. 1988, 34, 1887–1893. 10.1002/aic.690341114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Talu O.; Zwiebel I. Multicomponent Adsorption Equilibria of Nonideal Mixtures. AIChE J. 1986, 32, 1263–1276. 10.1002/aic.690320805. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siperstein F. R.; Myers A. L. Mixed-Gas Adsorption. AIChE J. 2001, 47, 1141–1159. 10.1002/aic.690470520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sochard S.; Fernandes N.; Reneaume J.-M. Modeling of Adsorption Isotherm of a Binary Mixture with Real Adsorbed Solution Theory and Nonrandom Two-Liquid Model. AIChE J. 2010, 56, 3109–3119. 10.1002/aic.12220. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.