Abstract

Background

Endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) allows us to intervene on patients otherwise considered poor candidates for open repair. Despite its importance in determining operative approach, no comparison has been made between the subjective “eyeball test” and an objective measurement of preoperative frailty for EVAR patients.

Materials and Methods

Patients undergoing elective EVAR were identified in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) database [2003-2017]. Patients were classified “unfit” based on a surgeon-reported variable. Frailty was defined using the VQI-derived Risk Analysis Index (VQI-RAI) which includes sex, age, BMI, renal failure, congestive heart failure, dyspnea, preoperative ambulation and functional status. The association between fitness and/or frailty and adverse outcomes was determined by logistic regression.

Results

A total of 11,694 patients undergoing elective EVAR were included of which only 18.1% were “unfit” while 34.6% were “frail”, and overall 43.6% “unfit or frail.” Patients deemed “unfit” or “frail” had significantly increased odds of mortality, complications, and non-home discharge (p<0.001), and both frailty and unfitness generated negative predictive values for these outcomes greater than 93%. In adjusted logistic regression, the addition of objective frailty significantly improved model performance in predicting non-home discharge (C-statistic 0.65 vs 0.71, p <0.001) and complications (0.59 vs 0.61, p=0.01), but similarly predicted mortality (0.74 vs 0.73, p=0.99).

Conclusions

Preoperative frailty assessment provides a useful objective measure of risk stratification as an adjunct to a physician’s clinical intuition. The addition of frailty expands the pool of high-risk patients who are more likely to experience adverse postoperative events following elective EVAR and may benefit from uniquely tailored perioperative interventions.

Keywords: Eyeball test, frailty, EVAR, Risk Analysis Index

Introduction:

Surgeons traditionally predict perioperative fitness by virtue of their clinical intuition and experience, a method often referred to as the “eyeball test”.1 The surgeon’s assessment is an overall gestalt of patient fitness upon review of patient history and physical exam. However, this clinical judgment is subjective by its very nature, and thus there is inherent variability among physicians.1-4 In contemporary practice, the demand for delivery of high-value care has necessitated quantification of subjective clinical assessments through objective scores to guide management (e.g. MELD score, APACHE II score). 1,5-9 The Risk Analysis Index (RAI) is one such objective instrument that can be employed to measure preoperative frailty. Validation evidence has been provided in studies demonstrating that preoperative RAI score predicts postoperative short- and long-term mortality in surgical populations.10,11 Frailty is defined as a biological syndrome that reflects a limited physiologic reserve, which in turn reduces a patient’s ability to withstand stressors and increases their vulnerability to adverse outcomes.12,13 Multiple studies, several in vascular surgery patients, have determined that frailty is a strong predictor of adverse outcomes such as short-term morbidity, long-term mortality, prolonged length of stay, and non-home discharge.11,13

In 2017 in the United States there were almost 10,000 deaths secondary to diseases of the aorta, with almost half of those related to ruptures of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA).14 Approximately 120,000 AAA repairs are performed annually to prevent subsequent aneurysm rupture.15,16 Endovascular techniques have enabled physicians to offer interventions to patients who would otherwise be considered poor candidates or “too frail” for open repair. However, despite its importance in determining operative approach for AAA repair, no comparison has been made between the subjective “eyeball test” and an objective measurement of preoperative frailty in vascular surgery patients.

This study aims to compare the performance of subjective surgeon assessment to the objective measurement of frailty as calculated by the RAI in predicting hospital death, complications, and discharge destination following elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair (EVAR). Our hypothesis is that the objective measurement of frailty would perform better than the subjective assessment of patient fitness in predicting adverse postoperative outcomes.

Methods

Patients undergoing endovascular AAA repair during the 15-year period between 2003 and 2017 were identified in the Vascular Quality Initiative database. The VQI was developed by the Society for Vascular Surgery in 2011 to improve the safety and efficacy of 12 common vascular procedures, including open and endovascular repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Details regarding this multicenter collaboration have been published and are available at www.vascularqualityinitiative.org.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to compare and contrast outcomes of those who were deemed “unfit” by the clinician’s assessment and those who were considered “frail” by the VQI-RAI. The subjective measure of patient fitness, the “eyeball test,” was determined from a surgeon reported variable in the VQI called UNFITOAAA, which was intended as a marker of poor candidacy for open AAA repair in the opinion of the operating surgeon. To assess frailty objectively, we utilized a VQI-derived version of the RAI where variables in the original RAI had been cross-walked to the variables in the VQI.10 This instrument is theoretically based on the deficit accumulation model of frailty by Rockwood et al and is an adaptation of the Minimum Data Set Mortality Risk Index-Revised.18-21 The original RAI was initially validated in the U.S. veteran population and has since been successfully applied to other large datasets and shown to be predictive of surgical outcomes.10,22 The RAI has recently been revised and recalibrated among development and confirmation samples within the Veterans Affairs Surgical Quality Improvement Program (VASQIP) and then tested externally for validation in the American College of Surgeons’ National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP) dataset as well as in a prospectively collected cohort from the Nebraska Western Iowa Health Care System VA.17 In this study, a cutoff of a VQI-RAI score of 30 was used to dichotomize frail (VQI-RAI ≥ 30) from non-frail patients (VQI-RAI < 30) as has been described in prior work.17

Cohort

This study using a de-identified database was deemed exempt from review by the Stanford University Institutional Review Board. Patients undergoing elective EVAR were retrospectively selected in the VQI database, and those with calculable VQI-RAI scores were included (N = 11,694 patients). Of those, 47 had the UNFITOAAA variable missing and thus our final cohort included 11,647 patients. The cohort was subdivided according to patients’ “fitness” and “frailty” status as dictated by the subjective assessment and the VQI-RAI, respectively. The relevant subgroups were “frail,” “unfit,” and “unfit or frail,” with the last category also given the label of “high risk” for the purpose of comparison to those who were neither frail nor unfit and thereby categorized as “low risk” surgical candidates.

Variables

The primary outcomes in the study were in-hospital mortality, postoperative complications as recorded by the reporting standards of the VQI, and discharge destination (home, skilled nursing facility, or rehabilitation). These data as well as patient demographics, co-morbidities, aneurysm characteristics, and procedural information are collected at the time of the initial hospitalization by the centers who participate in the VQI.

Statistics

VQI-RAI characteristics and covariates were compared among unfit and frailty subgroups by Student’s independent t-tests or chi-square tests. Differences in perioperative mortality, development of any complication, and postoperative discharge destination were also evaluated with chi-square tests. Postoperative complications assessed included experiencing myocardial infarction, dysrhythmia, congestive heart failure (CHF), renal failure (creatinine increase > 0.5 mg/dL or hemodialysis), respiratory complications (pneumonia or prolonged intubation), stroke, leg ischemia, bowel ischemia, surgical site infection, return to the operating room for bleeding, return to the operating room for other reason, or endovascular access site hematoma. Negative and positive predictive values were calculated for each subgroup. Recall that the negative predictive value (NPV) suggests that if the test is negative then the value of the NPV is the stated probability that the patient will not experience the adverse outcome, with the opposite logic utilized for interpreting positive predictive values. We then contrasted the abilities of frailty and unfitness to predict adverse outcomes using the DeLong method of logistic regression adjusted for race (African American, Asian, Caucasian (reference), Hispanic, Other), maximum AAA diameter (<4.50cm, 4.50-5.49cm, 5.50-6.49cm (reference), 6.50-7.49cm, >7.50cm), diabetes (yes/no), hypertension (yes/no), coronary artery disease (yes/no), and smoking (yes/no).23 Statistical significance was assessed at an alpha level of 0.05. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

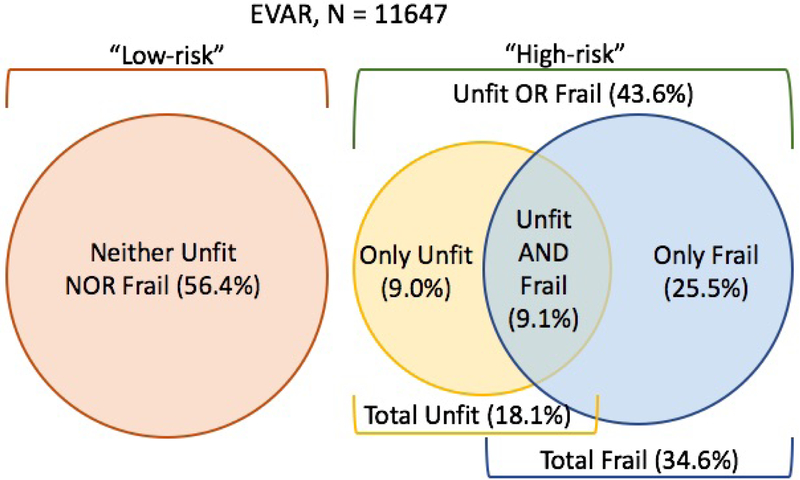

From 2003-2017 in the VQI dataset there were a total of 11,694 patients with calculable VQI-RAI scores who underwent elective EVAR, and 11,647 of those had a subjective surgeon assessment of patient fitness recorded. The overall mean age of the cohort was 74.02 years (SD 8.5) and the mean VQI-RAI score was 28.33 (SD 5.87). Overall, 18.1% of the cohort was deemed “unfit” by the surgeon’s eyeball test, 34.6% classified as “frail” by the VQI-RAI cutoff of ≥ 30, 9.1% were considered both “unfit and frail”, and 43.6% were rated either “unfit or frail” [Figure 1].

Figure 1:

Cohort distribution of patients undergoing elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI) who were considered unfit by subjective surgeon assessment and/or frail by the objective frailty measure of the VQI-Risk Analysis Index.

In those who were deemed “unfit” by the surgeon assessment, their mean age was 75.84 years (SD 8.3), length of hospital stay 4.39 days (14.87), and mean VQI-RAI score 30.59 (6.41). For those who were considered “frail” by the VQI-RAI, the mean age was 78.62 years (SD 7.51), length of hospital stay 3.97 days (13.28), and mean VQI-RAI score 34.78 (4.29). “Unfit or frail” patients were considered in our study to be “high-risk” surgical patients, and they had a mean age of 77.42 years (SD 7.96), mean length of hospital stay of 4.05 days (SD 14.96) and mean VQI-RAI score 32.87 (SD 5.51) [Table 1]. Compared to patients classified as neither or either “unfit” or “frail,” the 9.1% of patients qualifying as both “unfit and frail” had significantly higher mean RAI scores and proportion of female patients as well as a significantly higher prevalence of co-morbidities such as CHF, smoking history, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, and diabetes requiring medication. However, the proportion of patients on dialysis did not significantly differ, and their aneurysms were generally repaired at larger diameters [Supplemental Table 1].

Table 1:

Comparison of age, VQI-RAI scores, co-morbidities, aneurysm characteristics, and adverse outcomes in high-risk versus low-risk surgical patients undergoing elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI).

| Overall cohort (N=11,647) |

HIGH RISK “Unfit or Frail” (n=5,080) |

LOW RISK Neither “Unfit” nor “Frail” (n=6,567) |

High- vs. Low-risk p-value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, Mean (SD) | 74.02 (8.50) | 77.42 (7.96) | 71.30 (7.95) | <0.001 |

| VQI-RAI, Mean (SD) | 28.33 (5.87) | 32.87 (5.51) | 24.82 (3.07) | <0.001 |

| Female Gender, % | 19.1% | 19.8% | 18.5% | 0.07 |

| Race/Ethnicity, % | <0.001 | |||

| Caucasian | 90.0% | 89.0% | 90.7% | |

| African American | 4.3% | 5.1% | 3.7% | |

| Hispanic | 2.5% | 2.3% | 2.7% | |

| Asian | 1.3% | 1.6% | 1.0% | |

| Not reported/Other | 1.9% | 2.0% | 1.8% | |

| Renal Failure on Dialysis, % | 0.3% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 0.20 |

| Congestive Heart Failure, % | 12.2% | 24.1% | 3.1% | <0.001 |

| Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, % | 33.0% | 39.2% | 28.1% | <0.001 |

| Pre-op Smoking Status | <0.001 | |||

| Prior | 56.1% | 61.0% | 52.4% | |

| Current | 30.3% | 23.7% | 35.4% | |

| Coronary Artery Disease, % | 29.7% | 33.7% | 26.5% | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 84.3% | 86.1% | 82.9% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 16.4% | 18.0% | 15.2% | <0.001 |

| AAA diameter, % | <0.001 | |||

| Less than 4.50cm | 8.1% | 7.0% | 8.9% | |

| 4.50 – 5.49cm | 40.2% | 34.2% | 44.9% | |

| 5.50 – 6.49cm | 37.0% | 40.4% | 34.3% | |

| 6.50 – 7.49cm | 9.3% | 11.7% | 7.5% | |

| 7.50cm or larger | 5.4% | 6.7% | 4.5% | |

| ICU Length of Stay, mean days (SD) | 0.70 (1.98) | 0.88 (2.37) | 0.55 (1.59) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative Length of Stay, mean days (SD) | 2.57 (9.00) | 2.97 (6.58) | 2.25 (10.48) | <0.001 |

| Hospital Mortality, % | 0.5% | 0.8% | 0.2% | <0.001 |

| Any Complication, % | 8.6% | 11.6% | 6.3% | <0.001 |

| 1 complication | 5.8% | 7.6% | 4.5% | |

| 2 complications | 1.7% | 2.4% | 1.2% | |

| ≥ 3 complications | 1.0% | 1.6% | 0.6% | |

| Non-Home Discharge, % | 6.4% | 10.8% | 3.0% | <0.001 |

Finally, we classified those who were neither “frail” nor “unfit” as “low-risk” surgical patients. These patients were significantly younger than high-risk patients with a mean age of 71.30 years (7.95) and less frail with a mean VQI-RAI of 24.82 (SD 3.07) (p< 0.001). Additionally, the mean length of hospital stay was more than one day shorter at 2.94 (15.80) days for these “low-risk” compared to “high-risk” patients (p< 0.001). “High-risk” patients were found to have a significantly higher prevalence of congestive heart failure, smoking history, COPD, hypertension, and diabetes requiring medication, and their aneurysms were generally repaired at larger diameters. However, there was no statistically significant difference in gender between “high-risk” and “low-risk” patients (p=0.07) or in the incidence of pre-operative renal failure (p=0.20). Compared to “low-risk” patients, “high-risk” EVAR patients had significantly higher rates of in-hospital mortality (0.8% vs 0.2%, p<0.001), complications (11.6% vs 6.3%, p<0.001), and discharges to a facility other than home (10.8% vs 3.0%, p<0.001) [Table 1].

In logistic regression, patients deemed either “unfit” by surgeon assessment or “frail” by the VQI-RAI had significantly increased odds of experiencing in-hospital mortality, complications, or non-home discharge [Table 2]. In-hospital mortality was more strongly associated with a patient being “unfit” (Odds Ratio 3.47, 95% CI 2.04-5.87), but there were higher odds of non-home discharge associated with patient frailty compared to unfitness (OR 3.64, 95% CI 3.10-4.28). Patient frailty and unfitness resulted in similarly elevated odds (OR ~1.8) of experiencing one or more complications. Patients who were both “unfit and frail” demonstrated higher odds of all three outcomes compared to neither or either “unfit” or “frail” patients: in-hospital death (OR 6.83 (95% CI 3.40-13.83)), any complication (OR 2.84 (95% CI 2.34-3.45)), and non-home discharge (OR 4.96 (95% CI 3.95-6.21)), suggesting a strata of incrementally higher risk than the high-risk/low-risk dichotomization proposed initially.

Table 2:

Logistic regression comparing the odds of increased of adverse outcomes as well as the negative and positive predictive values of not experiencing those same adverse outcomes using a subjective surgeon assessment of patient fitness for surgery to an objective preoperative frailty measurement by the Vascular Quality Initiative-Risk Analysis Index (VQI-RAI). Model was adjusted for race, maximum AAA diameter, diabetes, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and smoking.

“Low risk”: neither “unfit” nor “frail.”

| Overall cohort (N=11,647) |

Unfit (n=2,105) |

Frail (n=4,034) |

Unfit or Frail (n=5,080) |

Unfit and Frail (n=1,059) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Mortality | 0.5% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.7% |

| Odds Ratio: Ref “Low risk” (95% Confidence Interval) | 3.47 (2.04-5.87) | 2.74 (1.61-4.74) | 3.44 (1.95-6.37) | 6.83 (3.40-13.83) | |

| Negative Predictive Value | 99.7% | 99.7% | 99.8% | 99.6% | |

| Positive Predictive Value | 1.2% | 0.8% | 0.8% | 1.7% | |

| Any Complication | 8.6% | 13.5% | 12.0% | 11.6% | 16.8% |

| Odds Ratio: Ref “Low risk” (95% Confidence Interval) | 1.82 (1.57-2.11) | 1.81 (1.58-2.07) | 1.89 (1.65-2.16) | 2.84 (2.34-3.45) | |

| Negative Predictive Value | 92.4% | 93.2% | 93.7% | 92.2% | |

| Positive Predictive Value | 13.5% | 12.0% | 11.6% | 16.8% | |

| Non-Home Discharge | 6.4% | 10.4% | 12.1% | 10.8% | 15.0% |

| Odds Ratio: Ref “Low risk” (95% Confidence Interval) | 1.79 (1.51-2.11) | 3.64 (3.10-4.28) | 3.59 (3.03-4.26) | 4.96 (3.95-6.21) | |

| Negative Predictive Value | 94.5% | 96.7% | 97.0% | 94.5% | |

| Positive Predictive Value | 10.4% | 12.1% | 10.8% | 15.0% |

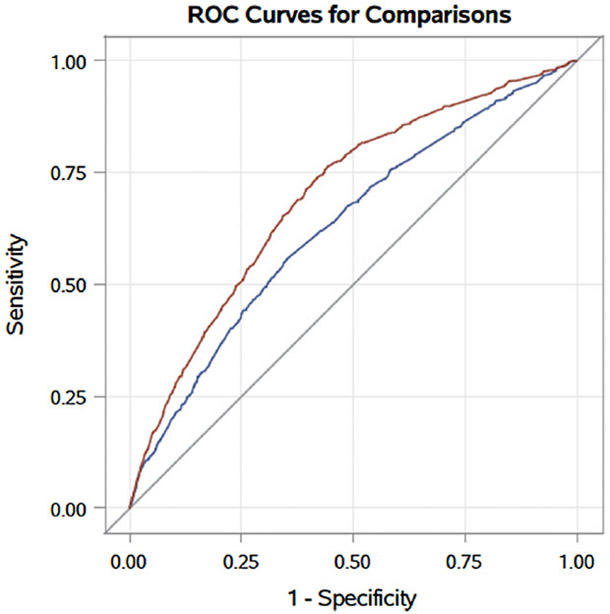

Nevertheless, the negative predictive values (NPV) of both frailty as measured by the VQI-RAI and surgeon assessment of patient fitness for ruling out adverse events were excellent (> 93% NPV for a designation of “frail” and >92% NPV for “unfit”). In the case of elective EVAR, if patients are considered to be low-risk (neither “unfit” nor “frail”), there is a less than 1% risk of perioperative mortality, less than 7% risk of a postoperative complication, and less than 3% risk of discharge to a skilled nursing facility or rehabilitation. Compared to subjective surgeon assessment alone, the addition of the objective measure of frailty significantly improved regression model performance in predicting patients who would experience complications (0.61 vs 0.59, p=0.001) or discharge to locations other than home (0.71 vs 0.65, p<0.001) [Figure 2], but similarly predicted in-hospital mortality (0.73 vs 0.74, p=0.993) [Table 3].

Figure 2.

Comparison of receiver operating curves (ROC) for predicting non-home discharge using patient fitness alone (blue) or with the addition of the objective measure of frailty to the surgeon’s subjective assessment (red). There was a significant improvement in model performance with the addition of the objective measure (c=0.71 vs 0.65, p<001).

Table 3:

Logistic regression demonstrating the improved model discrimination by adding the objective measurement of frailty to the subjective assessment of patient fitness in predicting adverse events following elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI). Model performance assessed by Hosmer & Lemeshow Goodness-of-Fit Test and comparisons between receiver operating curves made using the DeLong method.23

| Unfit C-Statistic (Subjective measure) n=2,105 |

Hosmer & Lemeshow Goodness-of Fit Test Pr > Chi Square |

Unfit or Frail C-Statistic (Subjective + Objective measure) n=5,080 |

Hosmer & Lemeshow Goodness- of Fit Test Pr > Chi Square |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospital Mortality | 0.740 | 0.883 | 0.733 | 0.798 | 0.993 |

| Any Complication | 0.593 | 0.763 | 0.609 | 0.792 | 0.001 |

| Non-Home Discharge | 0.644 | 0.272 | 0.706 | 0.854 | <0.001 |

p-value compares model C-statistics for “unfit” vs “unfit OR frail”

Discussion

In this analysis directly comparing a subjective assessment of patient fitness for surgery and an objective measure of patient frailty, both measures were significantly associated with increased odds of experiencing adverse postoperative events following elective EVAR. However, applying the VQI-RAI to the preoperative screening process identifies additional patients [n = 2,975, 25.5% of the cohort] who are almost equally or at times more at risk for adverse outcomes, effectively doubling the number of patients deemed high-risk. Additionally, those distinguished as both “unfit” and “frail” can be escalated to an even higher risk strata than those classified by one or the other subjective and objective assessments as evidenced by their greatly elevated odds of poor outcomes.

Compared to subjective surgeon assessment alone, the addition of the objective measure of frailty significantly improved model performance in predicting patients who would experience complications, but similarly predicted in-hospital mortality. The latter finding is somewhat expected given that in prior studies the VQI-RAI has proven valuable by more accurately predicting long-term mortality following surgery. By design, the RAI captures patients’ inability to cope with the physiologic stress of surgery.22 For instance, in prior work in the VQI focusing on both elective open and endovascular AAA repair, Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significant differences in survival curves when stratified by frailty status and procedure groups. Survival in “frail” patients undergoing EVAR was markedly worse than the non-frail group, with the proportion of surviving “frail” patients dropping from 93.6% at 3 months to 78.2% at 1 year post-operatively, compared to non-frail EVAR patients who saw 96.4% survival at 3 months and 94.6% at 1 year.24

The VQI-RAI is unique in that it incorporates five frailty domains [functional, physical, cognitive, nutritional and social] and factors in more than simply age and comorbidities . While age, comorbidities, and a surgeon’s gut feeling can be associated with poor outcomes, in isolation they are not useful as tools for determining candidacy for surgery, as corroborated in various studies.10,11,17 While surgeons’ subjective assessment performs well in identifying surgical candidates at risk of postoperative death (C-statistic = 0.738), we found that surgeons miss nearly half of the patients that may be at similar risk of dying yet do not appear frail to their eyeball test. The advantage of adding the RAI to the preoperative evaluation is that it ultimately functions to objectify the eyeball test and expand the pool of patients considered to be at-risk. We have also demonstrated that those who don’t pass the “eyeball test” and screen positive for frailty are at the highest risk of experiencing adverse perioperative outcomes. In this manner, objective frailty screening can be operationalized as a confirmatory and cautionary exercise to a surgeon’s subjective assessment to additionally designate a patient as very high-risk prior to elective EVAR.

Our prior work with the RAI in the VQI database found very high 1-year mortality for “frail” patients undergoing EVAR (22.7%) and open AAA repair (43.3%).24 In light of the escalated mortality risk, identifying frailty has implications for shared decision-making; including first and foremost the decision to operate, the operative approach (endovascular or open), and the potential for discharge to a rehab facility after surgery. As mentioned previously, the negative predictive value of both frailty as measured by the VQI-RAI and surgeon assessment of fitness is excellent. In this study, if the patient is not considered to be “unfit” or “frail,” there is a 99.8% chance that the patient will survive the perioperative period, a 93.7% chance that they will not experience a complication, and a 97% chance that they will discharge home. A potential downstream effect of ruling out frailty or unfitness is that a reassuring discussion with patients and their families regarding surgical risk might take place as there is now objective data that the patient doesn’t fall into the high-risk category for an elective surgery.

Discharge planning involves the process of transitioning a patient from one level of care to the next.25 In 2013 Edgerton et al found that half of the patients after cardiac surgery who were discharged to locations other than home did not return to independent living.26 Other studies have also demonstrated the ability of frailty status to predict discharges to non-home facilities.27,28 As part of managing expectations, patients and families should be informed early on by their providers about the potential for non-home discharge to enable planning ahead to the recovery phase. In this study, “frail” patients had twice the odds of non-home discharge compared to those deemed “unfit” for surgery, suggesting that surgeons may underestimate just how much of an immediate physiologic toll surgery will take. Similarly, in adjusted logistic regression, the addition of frailty to surgeon assessment significantly improved model prediction of non-home discharge, thereby demonstrating that utilizing the VQI-RAI preoperatively can function to optimize discharge planning and guide healthcare providers to realistically counsel patients and their caretakers.

There are several limitations to our study, some of which are inherent to the VQI dataset. First, there is a selection bias manifest in the data collection as institutions and providers voluntarily submit self-reported data and not all institutions or providers participate in all aspects of the registry. Second, there is a limitation in our ability to draw conclusions about causality and generalizability to other surgeries outside of EVAR. Further work is necessary to determine how the addition of the RAI can expand the pool of “at-risk” patients for other procedures. Third, the analyses may be subject to residual confounding due to unmeasured factors, such as a patient’s cognitive status or the presence of social support. Fourth, variables such as ambulation and functional status are prone to individual interpretation and as a result may introduce unintentional misclassification bias. Finally, the variable from which “unfit” was ascribed is also susceptible to bias given the natural variance of surgeons’ opinions that is also difficult to quantify in a dataset such as the VQI.

A significant body of work has been published describing the strengths and weaknesses of frailty in predicting poor surgical outcomes11,17. Future directions for frailty research should involve the implementation of routine preoperative frailty screening using validated instruments such as the RAI to 1) identify those who are low risk and thus “rule out” frailty; 2) redirect valuable perioperative resources towards the highest risk strata of surgical candidates and 3) facilitate transparency in the shared decision-making process regarding elective surgery and establish realistic post-surgical discharge expectations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, preoperative frailty assessment provides a useful objective measure of risk stratification as an adjunct to a physician’s subjective assessment of patients undergoing elective EVAR. The addition of frailty screening in preoperative workflow expands the pool of patients who are truly “high risk” for experiencing adverse outcomes and can be confirmatory of a surgeon’s subjective assessment to further identify the highest risk patients. The VQI-RAI has a high negative predictive value and consequently accurately identifies those who are not frail. Furthermore, it performs much better at identifying patients at risk for non-home discharge than the eyeball test. Routine preoperative measurement of frailty by centers to identify high risk patients may prove instrumental in determining which patients would most benefit from specially tailored pre-and post-operative interventions for enhanced recovery after surgery as well as anticipate discharge needs through early recognition.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Table 1. Comparison of age, VQI-RAI scores, co-morbidities, aneurysm characteristics, and adverse outcomes in patients labeled neither “unfit” or “frail,” either “unfit” or “frail,” or both “unfit” and “frail” undergoing elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented at: Northern California Chapter of the American College of Surgeons’ Annual Meeting. March 15-16, 2019, Berkeley, California.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Jain R, Duval S & Adabag S How accurate is the eyeball test?: a comparison of physician’s subjective assessment versus statistical methods in estimating mortality risk after cardiac surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 7, 151–156 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubbard RE & Story DA Does Frailty Lie in the Eyes of the Beholder? Heart, Lung and Circulation 24, 525–526 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hii TBK, Lainchbury JG & Bridgman PG Frailty in acute cardiology: comparison of a quick clinical assessment against a validated frailty assessment tool. Heart Lung Circ 24, 551–556 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Welke KF The eyeball test: can the blind leading the blind see better than the statistician? Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 7, 11–12 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai JC, Covinsky KE, McCulloch CE & Feng S The Liver Frailty Index Improves Mortality Prediction of the Subjective Clinician Assessment in Patients With Cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 113, 235–242 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larvin M & McMahon MJ APACHE-II score for assessment and monitoring of acute pancreatitis. Lancet 2, 201–205 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruse JA, Thill-Baharozian MC & Carlson RW Comparison of clinical assessment with APACHE II for predicting mortality risk in patients admitted to a medical intensive care unit. JAMA 260, 1739–1742 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP & Zimmerman JE APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit. Care Med 13, 818–829 (1985). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Who will die in the ICU? APACHE II, ROC curve analysis, and, of course, Cleone. JAMA 261, 1279–1280 (1989). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hall DE et al. Development and Initial Validation of the Risk Analysis Index for Measuring Frailty in Surgical Populations. JAMA Surg 152, 175–182 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arya S et al. Frailty increases the risk of 30-day mortality, morbidity, and failure to rescue after elective abdominal aortic aneurysm repair independent of age and comorbidities. J. Vasc. Surg 61, 324–331 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Mañas L et al. Searching for an operational definition of frailty: a Delphi method based consensus statement: the frailty operative definition-consensus conference project. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci 68, 62–67 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morley JE et al. Frailty Consensus: A Call to Action. J Am Med Dir Assoc 14, 392–397 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.WONDER Message. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D77;jsessionid=76BBF0C61A837651AD09ACAD5CB01CE3. (Accessed: 18th April 2019)

- 15.Multiple Cause of Death, 1999-2017 Request Form. Available at: https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D77. (Accessed: 4th April 2019)

- 16.Suckow BD et al. National trends in open surgical, endovascular, and branched-fenestrated endovascular aortic aneurysm repair in Medicare patients. Journal of Vascular Surgery 67, 1690–1697.e1 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arya S et al. Recalibration and External Validation of the Risk Analysis Index: A Surgical Frailty Assessment Tool. Annals of Surgery Publish Ahead of Print, (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kraiss LW et al. A Vascular Quality Initiative-Based Frailty Instrument Predicts 9-Month Postoperative Mortality. Journal of Vascular Surgery 64, 551–552 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraiss LW, Al-Dulaimi R, Thelen J & Brooke BS Postoperative Outcomes Correlate With Frailty Defined Using Vascular Quality Initiative Data. Journal of Vascular Surgery 62, 532 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Velanovich V, Antoine H, Swartz A, Peters D & Rubinfeld I Accumulating deficits model of frailty and postoperative mortality and morbidity: its application to a national database. J. Surg. Res 183, 104–110 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porock D, Parker-Oliver D, Petroski GF & Rantz M The MDS Mortality Risk Index: The evolution of a method for predicting 6-month mortality in nursing home residents. BMC Res Notes 3, 200 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hall DE et al. Association of a Frailty Screening Initiative With Postoperative Survival at 30, 180, and 365 Days. JAMA Surg 152, 233–240 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.DeLong ER, DeLong DM & Clarke-Pearson DL Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics 44, 837–845 (1988). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.George EL et al. Variation in Center-Level Frailty Burden and Its Impact on Long-Term Survival in Patients Undergoing Repair for Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms. Journal of Vascular Surgery 68, e41 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.CMS Updates Guidance for Hospital Discharge Planning ∥ Center for Medicare Advocacy. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Edgerton JR et al. Long-term fate of patients discharged to extended care facilities after cardiovascular surgery. Ann. Thorac. Surg 96, 871–877 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.AlHilli MM et al. Risk-Scoring Model for Prediction of Non-Home Discharge in Epithelial Ovarian Cancer Patients. J Am Coll Surg 217, 507–515 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson TN et al. Accumulated frailty characteristics predict postoperative discharge institutionalization in the geriatric patient. J. Am. Coll. Surg 213, 37–42; discussion 42-44 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Table 1. Comparison of age, VQI-RAI scores, co-morbidities, aneurysm characteristics, and adverse outcomes in patients labeled neither “unfit” or “frail,” either “unfit” or “frail,” or both “unfit” and “frail” undergoing elective endovascular abdominal aortic aneurysm repair (EVAR) in the Vascular Quality Initiative (VQI).