Abstract

A boy aged 19 years presented to emergency room with severe postprandial upper abdominal pain and recent significant weight loss, with history of decompressive craniotomy for post-traumatic frontal lobe haemorrhage. CT scan revealed an acute indentation of coeliac artery with high-grade stenosis and post-stenotic dilatation, diagnostic of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS). MALS, a diagnosis of exclusion, is identified using patient’s accurate symptomatic description. Exclusion of other causes of abdominal angina in a patient with frontal lobe syndrome was a challenging job, as they lack critical decision-making ability. Hence, the decision to proceed with the complex laparoscopic procedure was made by the patient’s parents and the surgeon, with the patient’s consent. Laparoscopic release of the median arcuate ligament resulted in relief of the patient symptoms much to the relief of his parents and the surgeon.

Keywords: vascular surgery, gastrointestinal surgery

Background

Median arcuate ligament (MAL) is a fibrous arch formed at the base of diaphragm at the level of T12 where the right and the left crura join on either side of the aortic hiatus. The ligament usually forms the anterior border of the aortic hiatus (figures 1 and 2). In certain people, there will be abnormal low insertion of the ligament causing indentation on the coeliac artery and these patients may have haemodynamically significant stenosis that would cause symptoms (figure 3). We present a rare case of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) following head injury (frontal lobe syndrome), which is the first instance in documented literature. Symptoms include recurrent abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and unintentional significant weight loss related to compression of coeliac artery. The diagnosis of MALS should be considered as a cause of abdominal angina in patients with variable clinical features that does not have a clear established aetiology.

Figure 1.

Diaphragm muscle (Illustrator: Dr Sanjana Ravindra).

Figure 2.

Normal anatomy showing median arcuate ligament (Illustrator: Dr Sanjana Ravindra).

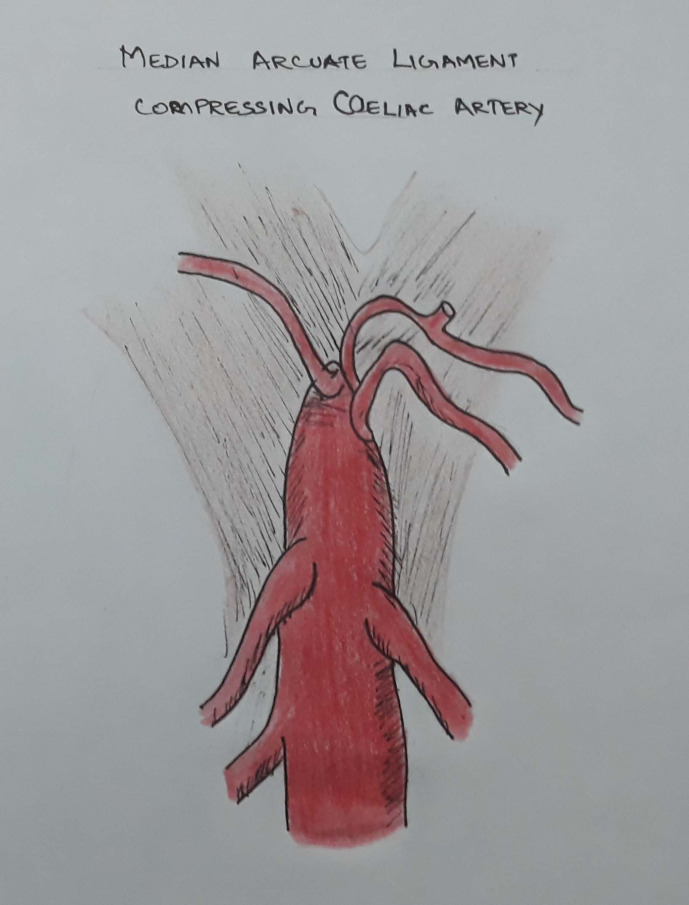

Figure 3.

Median arcuate ligament compressing coeliac artery (Illustrator: Dr Sanjana Ravindra).

Case presentation

A 19-year-old male patient, weighing 47 kg, presented to emergency room with upper abdomen pain for the past 1 week. Pain was often described as sudden crampy abdominal pain with severe intensity (pain score 9/10) in the epigastric region, non-radiating, aggravated on food intake and relieved after vomiting. He had significant unintentional weight loss of around 10 kg over 3 months. There were no other systemic symptoms like fever or altered bladder and bowel habits. He sustained a road traffic accident 3 months earlier and had frontal lobe haemorrhage, for which he underwent emergency left fronto-temporo-parietal decompressive craniotomy. He was irritable and agitated due to post-traumatic frontal lobe syndrome. Local examination of the abdomen revealed minimal epigastric and right hypochondrial tenderness. Abdominal guarding and rebound tenderness were absent. Classically, the pain was out of proportion to the findings on physical examination.

Investigations

Evaluating a patient with frontal lobe syndrome was difficult as it was hard to solicit his cooperation. All routine investigations and invasive diagnostic procedures like upper gastrointestinal endoscopy were normal. Contrast-enhanced CT of the whole abdomen showed acute indentation on the superior aspect of coeliac artery with high-grade stenosis and post-stenotic dilatation (hooked appearance) which was consistent with MALS (figure 4). Coeliac artery Doppler revealed an elevated peak systolic velocity of coeliac artery on expiration and normal velocity on inspiration, and stenosis in proximal segment of coeliac artery which was again in favour of MALS (figure 5).

Figure 4.

(A) Contrast-enhanced CT of whole abdomen showing hooked appearance (coronal view). (B) Zoomed in view of (A), showing hooked appearance with pre-stenotic segment and post-stenotic dilatation of coeliac artery, suggestive of median arcuate ligament syndrome.

Figure 5.

(A and B) Preoperative coeliac artery Doppler showing spectral variation with regards to respiration, suggestive of median arcuate ligament syndrome.

Treatment

Patient underwent laparoscopic release of MAL. Intraoperatively MAL was found to be densely adherent over the coeliac artery and the fibres were meticulously released from the coeliac artery (figure 6). The surgery was performed with a judicious combination of blunt and sharp dissection using harmonic shears.

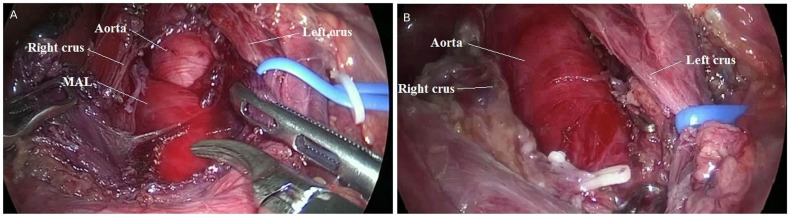

Figure 6.

(A and B) Technique of laparoscopic release of median arcuate ligament (MAL). Intraoperative picture showing MAL syndrome before (A) and after (B) release of MAL.

Outcome and follow-up

Patient had good symptomatic relief after the procedure. Postprocedure coeliac Doppler, which is a satisfactory modality in the postoperative assessment of surgical decompression due to its inexpensive and non-ionising nature,1 showed no spectral variation with respiration and there was no stenosis of coeliac artery (figure 7). At follow-up, after 6 months of surgery, patient is symptomatically much better. He is tolerating normal diet with no symptoms and his body mass index has increased from 15.9 to 20.3.

Figure 7.

(A and B) Postoperative coeliac artery Doppler showing no inspiration and expiration variation.

Discussion

Frontal lobe syndrome refers to a clinical syndrome which results from damage and impaired function of the prefrontal cortex area of the frontal lobe. Damage to this area will result in frontal lobe syndrome in which the higher mental functions of the brain, such as language, social behaviour, motivation, planning and speech production are damaged. Harlow, after his study on Phineas Gage, who following a trauma developed a dramatic change in behaviour, described this set of symptoms as frontal lobe syndrome.2 A drastic change in personality and goal-oriented behaviour happens in a patient following frontal lobe injury. Lesion in ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex area commonly cause ‘frontal lobe personality’ which is characterised by changes in behaviour leading to impulsivity, emotional lability, inability to interact with the society and lack of judgement.3

The existence of MALS is still a controversy, and it is a disease of mesenteric ischaemia and should be differentiated from other ischaemic bowel disease. It has gained the attention of many authors who are trying to find out the relationship of coeliac artery and diaphragm in embryogenesis.4 Some authors reported that the compression may be due to different aetiology such as neoplasm of pancreas and duodenum, vascular aneurysms and sarcoidosis.5

Superior mesenteric artery (SMA) syndrome had been reported following head injury but not MALS.6 Prolonged starvation following head injury may lead to loss of retroperitoneal pad of fat and exacerbation of MALS. MALS, also known as Dunbar syndrome or coeliac artery compression syndrome, was first described by Harjola et al in 1963.7 Later, Dunbar et al published a series of patients with MALS in 1965. Roayaie et al reported first case of MALS treated with laparoscopic decompression in 2000.8

The abnormally low MAL compromises the coeliac artery resulting in decreased blood flow and symptoms.9–11Radiologically, the incidence of MALS is found to be approximately 10%–24%.10 Classical triad includes postprandial abdominal pain, epigastric bruit and the presence of extrinsic compression of the coeliac artery revealed by imaging associated with nausea and vomiting with subsequent weight loss.12 Patients are usually thin people between the ages of 40 and 60 with postprandial pain and weight loss which is more than 20 pounds and typically need extensive work-ups to rule out other causes of abdominal pain.13

The compression worsens with expiration as the diaphragm moves caudally during expiration, causing compression of the coeliac trunk. This compression leads to visceral ischaemia and postprandial pain (compression theory). This also causes a steal phenomenon with the blood flow being diverted away from the SMA via collaterals to the coeliac axis causing midgut ischaemia. Overstimulation of the coeliac ganglion due to its compression is also believed to cause chronic pain in these patients (neural theory).

Patient may also experience sitophobia (fear of food) because of the symptoms. Patient may get transient relief of symptoms by bringing their knees to their chest. This position decreases impingement of the coeliac artery by pushing it cephalad relative to the artery. On physical examination, patient may have epigastric tenderness and also some will have epigastric bruit which may increase on expiration. Coeliac artery Doppler is a very useful diagnostic test which shows a marked increase in peak systolic velocity of coeliac artery on expiration. CT angiography of the abdomen reveals an acute indentation on the superior aspect of coeliac artery with high-grade stenosis and post-stenotic dilatation (hooked appearance).14–16

In the work-up of these patients, the surgeon should rule out other causes of visceral pain using various investigatory modalities like abdomen ultrasound, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy, colonoscopy, and gastric emptying studies. MALS is usually a diagnosis of exclusion in which patient’s decision-making ability becomes very significant.

Surgery is the mainstay of treatment in patients with persistent abdominal pain. Surgical approach includes coeliac artery decompression with or without coeliac artery angioplasty or reconstruction.17 18 Typically, pain relief is usually immediate. Since the postoperative pain can mimic preoperative symptoms, patients should be followed up for at least 6 weeks to ascertain the success of the procedure.

Surgical decompression resulted in overall clinical improvement in 83% of patients, with lack of improvement in older patients and in those with higher American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA).19 Endovascular stenting is usually reserved for patients in whom traditional surgery is contraindicated or used as an adjuvant procedure in patients who had a failed surgical decompression.20 21

Patient’s perspective.

My son suffered from severe abdominal pain. The pain from which he suffered cannot be defined. After food he used to complain of severe discomfort in the stomach and he used to scream out of pain. Even after very little intake of food, he would experience the above-said pain and he will vomit immediately. He was not able to consume even liquid food.

In this state, we got him admitted on 15 April 2018 night Sunday at 1:30. Initially, even the doctors were confused, and they took few investigations. After that they diagnosed median arcuate ligament syndrome. The doctors suggested surgery as the best treatment for the condition. But they explained us clearly that there are many complications in the surgery before itself. We also accepted for the surgery. A team of doctors performed the surgery. On 21 April 2018, the surgery was done. Till it got over, we were offering prayers to god. We felt relieved only when the doctors came out of the operation theatre and said that the surgery was successful. After that surgery, he has slowly recovered from that problem and at present he is back to normal state. We are so grateful to the doctors throughout our life. Thank you.

Learning points.

The present case is a rare presentation of median arcuate ligament syndrome (MALS) following head injury. Diagnosing MALS in a patient with head injury is a challenging job.

MALS is a diagnosis of exclusion.

But even in a patient with impaired mental capacity, the diagnosis of MALS should be considered in the absence of evidence of other possible diagnosis.

Suspicion of MALS warrants further invasive studies and raises the possibility of surgical intervention whenever necessary.

Minimal invasive surgical approach will be the ideal choice.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLKP involved in preoperative work-up and postoperative follow-up of the patient. SS and NDC were the primary surgeons. SR drawn diagrams for the manuscript and involved in manuscript publication work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ozel A, Toksoy G, Ozdogan O, et al. Ultrasonographic diagnosis of median arcuate ligament syndrome: a report of two cases. Med Ultrason 2012;14:154–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Damasio H, Grabowski T, Frank R, et al. The return of Phineas GAGE: clues about the brain from the skull of a famous patient. Science 1994;264:1102–5. 10.1126/science.8178168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tranel D. "Acquired sociopathy": the development of sociopathic behavior following focal brain damage. Prog Exp Pers Psychopathol Res 1994:285–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bech FR. Celiac artery compression syndromes. Surg Clin North Am 1997;77:409–24. 10.1016/S0039-6109(05)70558-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuter SR, Olin T. Stenosis of the celiac artery. Radiology 1965;85:617–27. 10.1148/85.4.617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pedoto MJ, O'Dell MW, Thrun M, et al. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome in traumatic brain injury: two cases. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1995;76:871–5. 10.1016/S0003-9993(95)80555-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harjola PT. A rare obstruction of the coeliac artery. Report of a case. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn 1963;52:547–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roayaie S, Jossart G, Gitlitz D, et al. Laparoscopic release of celiac artery compression syndrome facilitated by laparoscopic ultrasound scanning to confirm restoration of flow. J Vasc Surg 2000;32:814–7. 10.1067/mva.2000.107574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duffy AJ, Panait L, Eisenberg D, et al. Management of median arcuate ligament syndrome: a new paradigm. Ann Vasc Surg 2009;23:778–84. 10.1016/j.avsg.2008.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horton KM, Talamini MA, Fishman EK. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: evaluation with CT angiography. Radiographics 2005;25:1177–82. 10.1148/rg.255055001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gander S, Mulder DJ, Jones S, et al. Recurrent abdominal pain and weight loss in an adolescent: celiac artery compression syndrome. Can J Gastroenterol 2010;24:91–3. 10.1155/2010/534654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chou SQH, Kwok KY, Wong LS, et al. Imaging features of median arcuate ligament syndrome. Journal of the Hong Kong College of Radiologists 2010;13:101–3. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nedaa S, Leslie TC, Audra AD, et al. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: a nonvascular, vascular diagnosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;303:G155–68.22517770 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reilly LM, Ammar AD, Stoney RJ, et al. Late results following operative repair for celiac artery compression syndrome. J Vasc Surg 1985;2:79–91. 10.1016/0741-5214(85)90177-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aschenbach R, Basche S, Vogl TJ. Compression of the celiac trunk caused by median arcuate ligament in children and adolescent subjects: evaluation with contrast-enhanced Mr angiography and comparison with Doppler us evaluation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:556–61. 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jimenez JC, Rafidi F, Morris L. True celiac artery aneurysm secondary to median arcuate ligament syndrome. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2011;45:288–9. 10.1177/1538574411399155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentile AT, Moneta GL, Lee RW, et al. Usefulness of fasting and postprandial duplex ultrasound examinations for predicting high-grade superior mesenteric artery stenosis. Am J Surg 1995;169:476–9. 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)80198-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kohn GP, Bitar RS, Farber MA, et al. Treatment options and outcomes for celiac artery compression syndrome. Surg Innov 2011;18:338–43. 10.1177/1553350610397383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khrucharoen U, Juo Y-Y, Sanaiha Y, et al. Factors associated with Symptomology of celiac artery compression and outcomes following median arcuate ligament release. Ann Vasc Surg 2020;62:248–57. 10.1016/j.avsg.2019.06.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hongsakul K, Rookkapan S, Sungsiri J, et al. A severe case of median arcuate ligament syndrome with successful angioplasty and stenting. Case Rep Vasc Med 2012;2012:1–4. 10.1155/2012/129870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salem D, Delibasic M. Endovascular approach to treat median arcuate ligament compressing syndrome. Vascular Disease Management 2017;14:E37–45. [Google Scholar]