Abstract

Voluntary control over voice-hearing experiences is one of the most consistent predictors of functioning among voice-hearers. However, control over voice-hearing experiences is likely to be more nuanced and variable than may be appreciated through coarse clinician-rated measures, which provide little information about how control is conceptualized and developed. We aimed to identify key factors in the evolution of control over voice-hearing experiences in treatment-seeking (N = 7) and non-treatment-seeking (N = 8) voice-hearers. Treatment-seeking voice-hearers were drawn from local chapters of the Connecticut Hearing Voices Network, and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers were recruited from local spiritually oriented organizations. Both groups participated in a clinical assessment, and a semi-structured interview meant to explore the types of control exhibited and how it is fostered. Using Grounded Theory, we identified that participants from both groups exerted direct and indirect control over their voice-hearing experiences. Participants that developed a spiritual explanatory framework were more likely to exert direct control over the voice-hearing experiences than those that developed a pathologizing framework. Importantly, despite clear differences in explanatory framework and distress because of their experiences, both groups underwent similar trajectories to develop control and acceptance over their voice-hearing experiences. Understanding these factors will be critical in transforming control over voice-hearing experiences from a phenomenological observation to an actionable route for clinical intervention.

Keywords: auditory hallucinations, control, non-clinical voice-hearing, computational psychiatry, perception

Introduction

Auditory-verbal hallucinations, or voice-hearing experiences,1 are a core component of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, but may also occur in the general, non-treatment-seeking population.2–8 Voice-hearing experiences in treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking populations are remarkably similar in terms of fundamental acoustic qualities such as loudness, duration, and location,8–10 but show key differences in interpretation of the voices’ origins, their perceived malevolence, their content, and their ability to be engaged meaningfully.8,11–13 This knowledge has guided research into the neural underpinnings of hallucinations as distinct from other symptoms of psychosis14,15 and has provided useful insights into the relationship between voice-hearing and dysfunction.10,16–19 Some of the phenomenological and attributional differences between treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking groups of voice-hearers have already translated into clinically effective interventions for treatment-seeking voice-hearers.20,21

Voluntary control over voice-hearing experience is one potential candidate for a meaningful clinical measure and target for intervention that is based on documented differences between TS and non-treatment-seeking groups. Across a number of reports drawn from psychiatric, epidemiological, and anthropological studies, control over voice-hearing experiences consistently differentiates non-treatment-seeking from treatment-seeking voice-hearers.8–12,15,16,22–30 Interestingly, recovery-oriented groups such as the Hearing Voices Network (HVN) also promote development of agency over the timing and impact of voice-hearing experiences, mainly among people who have sought treatment.31–33

Control over voice-hearing experiences, defined as the ability to voluntarily influence the timing, frequency, or intensity of voice-hearing experiences, has been described as taking a variety of forms. These abilities range from engaging in non-voice-hearing-related activities that impact voice-hearing34,35 to directly controlling the onset and offset of voice-hearing episodes.8,36–38 This heterogeneity poses a significant challenge to the characterization of the psychological and biological processes underlying the development of control over voice-hearing experiences. Adding to this difficulty, there are very few measures to assess or characterize control to any degree of detail: currently available tools consist of single clinician-rated items on comprehensive scales of psychotic symptomatology such as the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scale (PSYRATS-AH).39

In order to better understand the varieties of control over voice-hearing experiences and the factors related to development of that control, we undertook a qualitative analysis of data drawn from semi-structured interviews aimed at elucidating the processes involved in developing control over voice-hearing experiences in both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking, as these populations differ on several factors (eg, social support, level of distress caused by the voices, coping strategies, content of the voices8,11–13,39) that could impact the development of control. Here, we present evidence for a common framework for the development of control across these 2 populations.

Methods

Participants

Participants with a history of at least weekly voice-hearing experiences who endorsed control over those experiences were recruited from local spiritual and psychic/medium communities (PM) (as described elsewhere8,14) and local chapters of the Connecticut Hearing Voices Network (HVN)40 via snowball sampling.41 Convenience sampling was intentionally employed in this study. Not all voice-hearers reach complete voluntary control over voice-hearing experiences (especially in treatment-seeking groups), and so we approached 2 voice-hearing groups known to be enriched with individuals reporting control over voice-hearing experiences8,14 (limitations evaluated in Discussion). To identify individuals within spiritual communities with voice-hearing experiences, we used social media and e-mail marketing to reach people who self-identified as psychic mediums throughout New England and New York. Respondents contacted the team if interested and were interviewed by phone to determine if they endorsed any degree of control over their voice-hearing experiences. Other participants reached out to the team on the recommendation of their colleagues, who had also participated. A total of 21 participants were interviewed. Six were excluded from the analyses for the following reasons: 1 underperformed in general intelligence assessment and 5 failed to complete clinical self-report. Thus, the sample used for analysis consisted of 8 non-treatment-seeking and 7 treatment-seeking participants.

Interview

Semi-structured interview questions were derived from prior work by our group8,14,41 and others,8,9,11,12,15,16,22–30,36–38 as well as input from members of our team (BQ and CB) with lived experience of voice-hearing. The final version (supplementary table S1) was reviewed by collaborators from HVN and the spiritual community to ensure that both the topics and terminology were meaningful and fit within the participants’ reference frame.

Measures

The remainder of the assessment included clinician-rated symptom severity ratings by the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),41 which were supplemented by a phenomenological interview based upon the Computerized Binary Scale for Auditory Speech Hallucinations (cbSASH).42 Symptom dimensions and degree of functioning were assessed using: the Launay-Slade Hallucinations Scale-Revised (LSHS-R),43,44 the Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire-Revised (BAVQ-R)15, the Peters et al45 Delusion Inventory (PDI), the Chapman Anhedonia, Perceptual Aberration, Magical Ideation subscales,46 Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II), and the Brief Multidimensional Measurement of Religiosity and Spirituality (BMMRS).47

Procedures

The Yale University Institutional Review Board/Human Interest Committee approved this study. Participants were consented for the study procedures, including audio-taping the interviews and releasing de-identified transcripts in scientific publications.

Participants took part in a 45- to 60-minute semi-structured interview conducted by members of the research team (N.E.M., F.K., B.Q., A.R.P.) who did not know the participant’s identities prior to the interviews as well as any details of their voice-hearing experiences. Follow-up questions were asked to ensure an in-depth understanding of participants’ voice-hearing experiences. The study team was composed of mental health professionals (psychiatrists, psychologists, therapists), students (undergraduate and medical), and people with lived voice-hearing experiences (one self-identified psychic/medium and one member of the Connecticut HVN), who were involved in different stages of data processing and interpretation of results to minimize idiosyncratic biases. A clinical diagnostic interview was conducted by 2 team clinicians and several symptom-severity and the presence of potential personality disorders were assessed via self-report surveys completed separately (supplementary methods).

Analysis

To identify factors and mechanisms explaining the process of developing control over voice-hearing experiences,42 interviews were analyzed using Grounded Theory,43,44 an inductive methodology that facilitates systematic generation of theory on complex subjective experiences.45,46 Transcribed interviews were analyzed following established coding techniques,45 and theory was developed through an iterative comparative process.47 The first step of the analysis, open coding, consisted of line-by-line reviewing and coding of each interview. Individual participants’ segments of text, ranging from clauses to paragraphs, were allowed to be assigned to multiple codes reflective of underlying concepts. Twenty-six codes and 41 subcodes were created to capture the participants’ experience description. The next stage of analysis focused on amalgamating and separating previously established open codes through a method of constant comparison within each interview, known as axial coding. Axial coding was conducted independently by 2 of the researchers (C.M. and B.Q.), compared for consistency by a third (F.K.), and then discussed with the research team to establish consensus. The main themes were organized along a timeline starting with participants’ first voice-hearing experiences and following control development. The coding process was facilitated by MaxQDA48 (VERBI Software). For questionnaires and self-report measures, we compared the groups using non-parametric analyses. Mean ranks differences were computed using Mann-Whitney tests and proportion differences were obtained using chi-square tests. The Holm-Bonferroni procedure was used for multiple-comparisons correction.

Results

Sample Characteristics

No significant inter-group differences were found in age (MNTS = 37.38, SDNTS = 11.88; MTS = 31.00, SDTS = 6.63, z = −.927, P = .354), gender distribution (χ 2(1) = 1.029, P = .569), or educational attainment (χ 2(1) = 1.759, P = .185).

Clinical, Symptom, and Phenomenological Characteristics

All treatment-seeking and only 3 non-treatment-seeking participants reported having ever received a psychiatric diagnosis (table 1). Results of the SCID-II revealed that treatment-seeking participants exhibited increased borderline personality traits relative to the non-treatment-seeking group (table 2, corrected, P = .012). As has been demonstrated in the past, several between-group differences in voice-hearing experiences, symptom attribution and engagement were found (table 3). Treatment-seeking participants believed the voices were more likely to be malevolent (BAVQ-R - Malevolence; corrected, P = .012, see table 6, Beliefs about the voices, for verbatim examples), demonstrated higher levels of behavioral (BAVQ-R - Behavioral Resistance; corrected, P = .004) and overall resistance to their voices (BAVQ-R - Resistance; corrected, P = .001). Non-treatment-seeking participants reported increased overall (BAVQ-R Engagement; corrected, P = .016) and emotional engagement with their voice-hearing experiences (BAVQ-R Engagement; corrected, P = .040). Treatment-seeking participants reported higher degrees of non-hallucinatory perceptual abnormalities than non-treatment-seeking participants (Chapman; corrected, P = .021). Non-treatment-seeking participants trusted more in religion and spirituality as coping strategies (BMMRS Religious & Spiritual Coping; corrected, P = .014). Similar scores were reported for hallucination severity (on LSHS-R and BPRS), as well as delusion propensity and distress due to delusions (on PDI). Phenomenological characteristics, measured by the cbSASH (supplementary table S2), differed between groups. Non-treatment-seeking participants were more likely to report experiencing voice-hearing experiences via their ears (corrected, P = .007), increased use of first-person syntax (corrected, P = .020), content of voice-hearing experiences focused on themselves (corrected, P = .000) and the ability to induce their voice-hearing experiences at will (corrected, P = .001).

Table 1.

Demographics and Self-Reported Psychiatric Diagnoses by Group

| Non-Treatment-Seeking | Treatment-Seeking | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 5 | 6 |

| Male | 3 | 1 |

| Age | M = 37.38 (SD = 11.8) | M = 31.00 (SD = 6.6) |

| Race | ||

| White | 7 | 5 |

| Hispanic | 1 | 1 |

| Asian | 0 | 1 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school degree | 0 | 1 |

| High school | 1 | 2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 4 | 4 |

| Master’s degree | 3 | 0 |

| Employed | 8 | 5 |

| Self-Reported Psychiatric Diagnoses | ||

| Bipolar Disorder | 1 | 4 |

| Depression | 1 | 1 |

| Panic Disorder | 0 | 2 |

| Anxiety | 1 | 1 |

| Psychosis | 0 | 1 |

| Schizophrenia | 0 | 1 |

| Schizoaffective | 0 | 1 |

| Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 0 | 2 |

| Obsessive Compulsive Disorder | 0 | 1 |

| Major Depression | 0 | 1 |

| Borderline Personality Disorder | 0 | 1 |

| Eating Disorders | 0 | 1 |

| No. of Participants Diagnosed | 3 | 7 |

Note: Numbers denote frequency except where otherwise specified. Self-reported psychiatric diagnoses were derived from a self-report.

Table 2.

Descriptive of Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II Personality Disorders (SCID-II) for Non-Treatment seeking and Treatment Seeking Participants

| Non-Treatment seeking | Treatment seeking | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subscale | M | SD | SE | Fq | M | SD | Fq | SE | P | P(corr) | Eta2 |

| Avoidant | 2.5 | 1.35 | 0.38 | 1 | 4.57 | 2.07 | 4 | 0.52 | .021 | .210 | .340 |

| Dependent | 1.75 | 1.41 | 0.50 | 0 | 4.43 | 2.23 | 2 | 0.78 | .061 | .549 | .229 |

| Obs. Compulsive | 3.88 | 1.15 | 0.40 | 3 | 3.57 | 2.07 | 1 | 0.78 | .283 | 1 | .072 |

| Passive Aggressive | 1.75 | 1.35 | 0.45 | 0 | 1.71 | 1.25 | 0 | 0.47 | .905 | 1 | .001 |

| Depressive | 1.38 | 1.51 | 0.53 | 0 | 4 | 1.73 | 1 | 0.65 | .014 | .154 | .394 |

| Paranoid | 1.63 | 1.38 | 0.46 | 0 | 3 | 2.24 | 2 | 0.85 | .23 | 1 | .089 |

| Schizotypal | 6 | 0.38 | 0.19 | 8 | 5.29 | 2.69 | 6 | 1.02 | .951 | .951 | .000 |

| Schizoid | 0.88 | 0.69 | 0.23 | 0 | 1.86 | 1.35 | 0 | 0.51 | .119 | .833 | .151 |

| Histrionic | 1.38 | 0.98 | 0.32 | 0 | 2.29 | 1.11 | 0 | 0.42 | .115 | .920 | .151 |

| Narcissistic | 2.75 | 2.79 | 0.92 | 2 | 4.14 | 2.19 | 2 | 0.83 | .293 | 1 | .072 |

| Borderline | 1.75 | 0.95 | 0.31 | 0 | 6.43 | 2.64 | 4 | 1.00 | .001 | .012 | .651 |

| Conduct Disorder | 1.13 | 0.82 | 0.30 | 0 | 1.14 | 1.46 | 1 | 0.55 | .694 | 1 | .014 |

Note: M = Mean; Fq = number of participants that meet the criteria for each personality disorder; P(corr) = P-value corrected for multiple-comparisons; Eta2 = Eta Squared. Boldface represents significant values after correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 3.

Descriptive by Scale for Non-Treatment-Seeking and Treatment-seeking Participants

| Non-Treatment Seeking | Treatment Seeking | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | Mode | Med | Min | Max | IQR | M | SD | Mode | Med | Min | Max | IQR | P | P(corr) | Eta2 | |

| LSHS-R | 17.75 | 5.99 | 11 | 17 | 11 | 26 | 10.75 | 20.57 | 8.3 | 8.0 | 20 | 8 | 34.0 | 12.0 | .524 | .524 | .027 |

| BPRS | 25.25 | 1.83 | 25.0 | 25 | 23 | 28 | 3.25 | 28.71 | 4.15 | 23.0 | 29 | 23 | 34.0 | 9.0 | .114 | .114 | .163 |

| BAVQ-R | |||||||||||||||||

| Malevolence | 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7.43 | 6.8 | 1 | 9 | 0 | 16.0 | 14.0 | .004 | .012 | .514 |

| Benevolence | 11.5 | 4.04 | 5.0 | 12 | 5 | 18 | 8.25 | 7.29 | 4.07 | 1.0 | 7 | 1 | 14.0 | 5.0 | .104 | .823 | .175 |

| Omnipotence | 4.38 | 2.16 | 7.0 | 4.5 | 1 | 7 | 4.5 | 6.14 | 4.1 | 3.0 | 5 | 3 | 15.0 | 3.0 | .558 | 1 | .022 |

| Emotion Resistance | 1.13 | 0.9 | 0.0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 4.28 | .00 | 8 | 0 | 10.0 | 9.0 | .076 | .532 | .201 |

| Behavior Resistance | 1 | 1.68 | 0.0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2.5 | 7.14 | 3.44 | 7 | 7 | 3 | 13.0 | 6.0 | .002 | .004 | .201 |

| Resistance | 2.13 | 1.72 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0 | 5 | 2.75 | 13.15 | 5.87 | 19 | 14 | 4 | 19.0 | 12.0 | .001 | .001 | .651 |

| Emotion Engagement | 8.75 | 3.4 | 12.0 | 9.5 | 3 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 2.71 | .00 | 3 | 0 | 6.0 | 6.0 | .008 | .040 | .452 |

| Behavior Engagement | 8.88 | 3.79 | 2.0 | 9.5 | 2 | 14 | 5.5 | 4 | 3.87 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 11.0 | 6.0 | .032 | .192 | .306 |

| Engagement | 17.63 | 6.43 | 8.0 | 17.5 | 8 | 26 | 11.5 | 7 | 4.76 | .00 | 8 | 0 | 12.0 | 10.0 | .004 | .016 | .514 |

| Chapman | |||||||||||||||||

| Magical Ideation | 12.75 | 3.21 | 9.0 | 11.5 | 9 | 22 | 7.5 | 12.29 | 4.64 | 6.00 | 12 | 6 | 20.0 | 7.0 | .953 | 1 | 0 |

| Perceptual Abnormalities | 3.13 | 1.4 | 2.0 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 2.75 | 9.57 | 6.53 | 2.00 | 9 | 2 | 21.0 | 10.0 | .021 | .021 | .340 |

| Social Anhedonia | 8 | 5.15 | 2.0 | 8.5 | 2 | 15 | 8.75 | 10.57 | 5.56 | 11 | 11 | 2 | 19.0 | 5.0 | .416 | 1 | .044 |

| PDI | 6.88 | 2.97 | 8.0 | 7 | 2 | 14 | 6.25 | 6.86 | 3.48 | 4 | 6 | 4 | 13.0 | 6.0 | .953 | 1 | 0 |

| PDI Distress | 12.5 | 7.6 | 3.0 | 9.5 | 3 | 31 | 17.75 | 15.43 | 7.46 | 11 | 12 | 8 | 30.0 | 8.0 | .383 | 1 | .050 |

| BMMRS | |||||||||||||||||

| Spiritual Daily experiences | 2.67 | 1.37 | 29.0 | 43.5 | 29 | 81 | 28.5 | 3.74 | 0.92 | 46.00 | 57 | 46 | 84.0 | 24.0 | .164 | 1 | .129 |

| Religious Practices | 7.25 | 4.93 | 1.0 | 2.67 | 1 | 5.17 | 2.12 | 5.64 | 1.19 | 4.17 | 3.33 | 2.83 | 5.50 | 1.17 | .397 | 1 | .050 |

| Religious and Spiritual Coping | 3.86 | 2.86 | 4.25 | 4.5 | 2.5 | 7.25 | 2.18 | 3.46 | 0.33 | 3.50 | 6 | 3.5 | 7.00 | 1.75 | .014 | .014 | .201 |

Note: LSHS-R = Launay-Slade Hallucinations Scale-Revised; BPRS = Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale; BAVQ-R = Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire-Revised; PDI = Peters et al. Delusion Inventory; Chapman = Chapman Anhedonia, Perceptual Aberration, and Magical Ideation subscales; BMMRS = Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality; M = Mean; Med = Median; Min = Minimum; Max= Maximum; IQR = Interquartile ratio; P(corr) = P-value corrected for multiple-comparisons; Eta2 = Eta Squared. Boldface represents significant values after correction for multiple comparisons.

Table 6.

Factors Associated With Efficacy of Control Over Voice-Hearing Experiences

| 1.Mood changes | |

|---|---|

| Treatment-Seeking [TS] | Non-Treatment-Seeking [NTS] |

|

TS14 “No. I’m not always distressed by them [voices]. Like I said, it’s, it depends on my environment, and if I’m stressed or not stressed. Or if I have like a setback, obviously, they are going to be more prominent than like right now, as I struggle more with motivation and flatness and stuff like that.” TS18 “I could control … I got to put myself in a good mood if they’re negative. I cheer myself up. But if they’re positive, they’ll usually be giving me advice…” TS20 “I can change my mood and then it stops [the voices]. But usually I can’t control it (referring to the mood), so I just go to sleep.” |

NTS07 “So like if like sometimes they would make me feel bad, and I would sense a feeling. So, like why am I feeling this, what’s going on?” …” the longer I’ve been in therapy, the longer I’ve done like life coaching and, have gotten my own personal world in order, there’s less and less and less of bad stuff.” |

| 2.Structured and predicted daily schedule | |

| TS21 “I seclude myself. It’s another part of taking care of myself. I learned I really can’t just push through. that will not work, it’ll just make it worse. So, what I do is I go home, I go in my room, and I just surround myself with comfort things.” | NTS04 “Well I’m on a schedule. If I’m sitting at dinner, and two or three shows up (referring to voices), and I’m stunned to the couple of times, I will say out loud, “too early, it’s 5 o’clock, you are not supposed to come until 7.” |

| 3.Self-care habits | |

| TS14 “I practice mindfulness and meditation when I can. And I’m very into exercise, when I can. I mean, I still struggle daily…but I do really what I can, like, to promote my own health, because I know I have some sort of agency and control during all of this.” |

NTS09 “But the meditation also allows a space to be created, … meditation is probably one of the best things that I do for myself for that.” NTS07 “Meditation trainings to kind of calm the mind, some, what we would call like psychic development work..” |

| 4.Beliefs about the voices | |

|

TS10 “When I was a teenager and in my 20s, I did not learn how to control them...He [a male voice] tells me a lot of negative, but lately since I’ve been learning how to control him … I’ve been hearing better voices.” TS18 “[about negative voices] I was like, ok it might be something inside me telling me these negative things, but I turned it into a positive. So, if I do hear anything negative, I think about the pros and cons, things like that.” |

NTS09 “Just energy. I don’t believe in ghosts, I’ll be the first person to say I don’t believe in the devil and I don’t believe in demons either. I believe there is energy that is frenetic.” NTS02 ‘Most of my spirit guides are male. Very few are female, and those are very different conversations and uh…” NTS06 “She was guiding me. Most of what I learned what to do, and how to do it. She taught me from the other side. She taught me sit quietly. She taught me, she would nudge me where to go.” |

Control Over Voice-Hearing Experiences

The following categories resulted from the inductive process of interview data analysis involved in Grounded Theory method. These themes represent an abstraction of different aspects of participants’ experiences, referenced directly from text cited in tables 4 to 7.

Table 4.

Meaning of Control Over Voice-Hearing Experiences

| Treatment-Seeking [TS] | Non-Treatment-Seeking [NTS] |

|---|---|

|

TS21 “And it was distressing to me because of how emotional it was [referring to the voices]. And finally, I just interrupted that and said, “I can’t concentrate, you need to stop doing this.” TS18 “I thought at first it was somebody in the outside speaking to me or calling me. So, I look out my window… I was in the mental hospital…because I wasn’t in the right state of mind. I was talking to the TV. I thought the TV was talking to me.” |

NTS05 “I guess I call upon them, you know, from my own things that I want guidance, from. But they don’t always provide the guidance if I need to learn a lesson.” NTS02 “…they [the voices] come to me, if I’m meditating, or, you know, I want to talk to, you know have a conversation with my mother, who passed, because I’m having a bad day...,” “I cannot initiate it unless I am doing mediumship work.” NTS07 “[about the voices] I think, I think it’s a spiritual world, I think internal, external. I think it’s a spiritual realm. I think whether you want to call it another dimension, or whatever.” |

Table 7.

Common Themes on Control Development Over Voice-Hearing Experiences

| 1.Voice Onset | |

|---|---|

| Treatment-Seeking [TS] | Non-Treatment-Seeking [NTS] |

|

TS12 “So I’ve been a voice hearer for a really long time. I was very auditory when I was younger, and when it happened at first, I didn’t really talk about it to anyone … and I had a lot of issues going on.” TS22 ..."my first kind of hearing voices – I would say for a couple of weeks, like a break, or episode kind of thing when I was about 32. And it was initially really scary.” |

NTS02 “I began to begin hearing things, we call them voices in my, in my youth, pre-teen. It would be very simple of ‘hi (subject name)’ …. And it was weird, but I rode it off and never gave it much thought, NTS05 “…my first experience of clairaudience was because I was praying to the angels to ask for help…that was so weird, I don’t know what to think about this right now.” |

| 2. Making Sense of the Experience | |

|

TS12 “I figured out about different voices and different aspects, or what I’ve come to understand, is that they are all different parts of myself, and they all have a voice, and they’ve always been there my whole life..” TS22 “So, it’s not like a normal thing to hear voices.” “…I was like something’s not quite right. … I was like, I kept hearing ‘wherever you go I’ll be there, wherever you are I’ll be there,’ and I was like, this isn’t cool. I need to go back to work, like, I can’t anymore.” |

NTS02 “Well you know as a kid, you know, I wondered, ‘what is this,’ … ‘what is this?’, but it didn’t bother me that much… and now I’m just more spiritually conscious, I don’t know, but I am really determined that this is a spirit talking to me.” NTS05 “I went into those class pretty much thinking I was going to be a clairvoyant, … I realized that I was actually hearing information in my, primarily in my right ear… I primarily connect to the angels” |

| 3. Turning Point | |

|

TS12 “Until I got hospitalized and someone asked me about voices and I’m like “yeah” … I went to the hospital, they made me feel ashamed about it…they drugged me up with a lot of medications and so I was never talked about it again…” TS22 “I went to the hospital. And I was like, ‘Hi, I’m hearing voices. Something’s not quite right”…“I remember my therapist had said, “if you hear something, why not ask who it is and what they’re trying to tell you? You know?.” And I was like, “oh ok.” So, I thought I heard something, I thought I heard a guy again. And I was like “hello?” and they were like, “hi, I’m here” |

NTS02 “….and so I, I said, ‘okay, we’re not going to go this way’ with clinical. You know, let’s try to stop what is happening to me of hearing voices and having feelings...and let’s say that I am not broken, and that maybe what I am hearing, or feeling is normal. So, let’s go this way, and look alternatively in shamanic tradition, which is what resonated, you know, with me.” NTS05 “So I started to get as many books as I can as far as psychics, and even like ghost stories and haunted houses and angels and just trying to like figure this whole world out” |

| 4. Support Seeking | |

|

TS12 “…definitely have the community with people with similar experiences. We all understand each other in that aspect. When I went to the hospital this year, I faced a hard dilemma, I know that my team supporting me while I was going through the process – or even when I was super suicidal, they babysat me” TS22 “Yeah, I mean that’s the first thing I looked up, is there psychic therapy? Is there psychic support? A support group? And I couldn’t find anything. There’s gotta be something.” |

NTS02 “Yeah. They’re, um, they’re like my community, my soul family, my friends. … what I call family, and we all care for each other as deeply as human beings.” NTS05 “I left teaching just a few months after meeting (mentor name), and starting to investigate my psychic abilities. Um, and I just kind of went on this like, I’m going to jump and hope you catch me kind of thing.” |

| 5. Acceptance | |

|

TS12 “Learning to accept all aspects. You know like, because I’m not an organized person because of this. But I’ve accepted that part about myself if that makes sense” TS22 “I heard “hey listen, you can go on them. Do whatever’s comfortable for you.” For me, it was kind of like – they’re always going to be here, so I need to start tuning into what’s happening emotionally with me, versus kind of like not dealing with it. Let’s see what happens.” |

NTS02 “I’m hearing people that want help crossing. So, the more you open yourself up, and the more you accept it. And, and I do think that a piece of it is not feeling like you are broken, not feeling like you should be ashamed, or not those traditional feelings that maybe there is a reason for this, the better of you are.” NTS05 “I have come out and said “this is my gift, this is what I’m doing with my life.” And so people are kind of coming out to me, it’s like coming out of the psychic closet, to be honest.” |

Meaning of Control

Control over voices does not have a singular meaning among participants. For some, exerting control referred to the ability to control the onset and cessation of voice-hearing experiences (table 4, TS21, TS18), whereas for others it meant seeking to establish a relationship with the voice(s) in order to understand the reasons for its presence and what the voice is trying to communicate (table 4, NTS05, NTS02, NTS07). Many of them do not use the word “control” at all, instead preferring interpersonal terms like “relationship” or “connection.” Here, we use the word control to refer to experiences in which the participant can exert a certain level of agency over the onset, content/resignification, and offset of the voices using a variety of coping strategies. Additionally, control is understood by the participants through the lens of their explanatory frameworks (ie, spiritual or pathologizing) and the quality of those experiences over time (table 4, NTS02, NTS07).

Types of Control.

In all cases examined, control is characterized by the ability to manage either when the voices appear (direct control), to use other factors to minimize how impactful or disruptive the voices are when they do appear (indirect control), or some combination thereof. Direct and indirect control over the voices is related to the use of different strategies.

Strategies to develop direct control were reported to result in the ability to directly influence the onset and/or offset of voice-hearing experiences. These included: engaging with voices; developing an understanding of voices’ personhood and intentions; and negotiating boundaries with the voices. Direct control strategies were employed most frequently (but not exclusively) by participants who understood voices as spiritual entities or as representations of different aspects of themselves. Gaining control over voice-hearing experiences using these strategies required not only practice but also the development of confidence in one’s ability to exert control (table 5, Direct Control).

Table 5.

Types of Over Voice-Hearing Experiences

| 1.Direct Control | |

|---|---|

| Treatment-Seeking [TS] | Non-Treatment-Seeking [NTS] |

|

TS15 “…I stopped saying. “that’s a negative voice.” I started saying “I understand why you exist.” I’d ask why are you here? I started to comfort these voices. I started to take more of a higher, wiser position for how I dealt. I delegated and said, anything I thought I needed work on, I would work everything out with myself. So, I sort of therapized myself.” TS14 “There’s no other way I can control them. Like I have to negotiate, I have to communicate and then they have to agree.” |

NTS02 “… instead of ignoring it, or brushing it off, or changing my immediate focus to make it go away, I embraced it and said ‘Alright. Let’s stick around and let’s see’. You know, basically ‘what the hell are you trying to tell me? What do you want?’. And the more you open yourself up, the more it happens.” NTS08 “Basically, um, just asking them to, ‘this is my time, this is my’ whatever I’m doing. But yeah, it’s like um, it’s like your best friend that even though you ask for ‘shh don’t say anything’.” |

| 2.Indirect Control | |

| TS10 “So I’m trying not to focus on them… if I’m at my place or at my parents I love to color. That’s a good distraction from them. Put on some nice music. Sometimes, I do have to take one of my anxiety pills too. | NTS09 “Distraction is one them. Meditation is another one, just getting really quiet. And music is another and keeping busy is another – I guess that goes along with the distraction.” |

Strategies to develop indirect control were based on attentional reallocation, detachment, or distraction. These included listening to music, watching television, or keeping themselves busy, and allowed them to keep a certain distance from the content and emotional state that the voices generated. These strategies were occasionally related to a lack of sense of agency and the difficulty of integrating voice-hearing experiences into their narratives (table 5, Indirect Control).

Most participants reported that there was some overlap in the types of strategies employed over time. Indirect strategies often stopped being useful at some point, spurring a search for direct strategies or other, more effective indirect strategies to achieve control.

Efficacy of Control

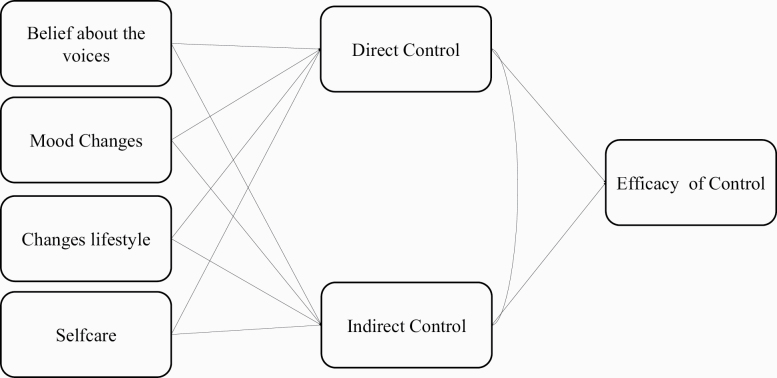

The degree to which individuals are able to exert either direct or indirect control seems to be associated with several factors. These include mood; structured and predicted daily schedules; self-care; and participants’ beliefs about the voices. Hypothesized interactions among these factors are summarized in figure 1.

Fig. 1.

A hypothesis of how efficacy of control is related with control strategies and factors associated with control.

Participants in both groups reported past major depressive episodes as well as periodic struggles with anxiety (table 1). Mood changes, such as increased anxiety or depressed mood, were reported to make it more difficult to exert control over voice-hearing experiences (table 6, Mood Changes).

The ability to organize daily activities in a way that makes events and voice-hearing experiences predictable helped in the development of a stronger sense of agency (table 6, Structured and predicted daily schedule). Non-treatment-seeking participants frequently employed scheduling time for their voices as a direct control strategy (table 6, Structured and predicted daily schedule, NTS04).

Most participants reported specific changes in self-care habits that were associated with greater control over voice-hearing experiences. These included healthy eating, sufficient sleep, meditation, reiki, regular exercise, and contact with nature. Some of these activities, such as meditation and exercise, were reported to improve control by lowering anxiety levels (table 6, Self care habits).

Lastly, beliefs about voices play an essential role in how participants experience voice-hearing experiences; spiritual or pathologizing frameworks influenced how participants interacted with and developed strategies to cope with voice-hearing experiences. Non-treatment-seeking participants developed a cooperative and meaningful relationship with their voice-hearing experiences, which were often described as friends or guides (table 6, Beliefs about the voices, NTS09, NTS02, NTS06). Treatment-seeking participants developed a pathologizing framework of their voice-hearing experiences, which were described as intrusive, negative, and distressing experiences. However, some treatment-seeking participants reported engaging with their voices despite derogatory content, leading to resignification of the content and development of a sense of control over their voice-hearing experiences (table 6, Beliefs about the voices, TS10, TS18).

Common Themes in Development of Control Over Voice-hearing Experiences

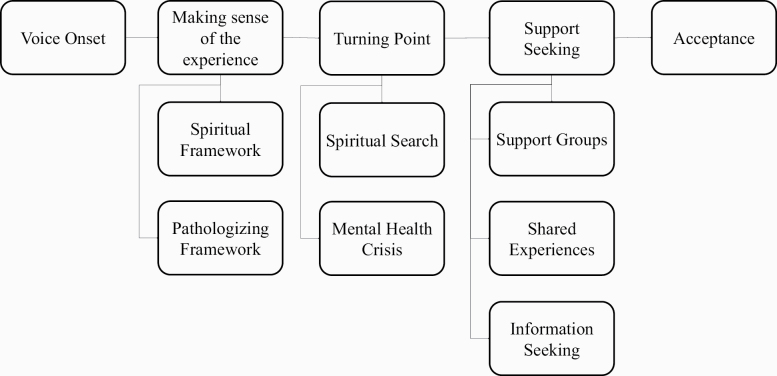

Five main stages or themes in the development of control were identified in both groups: (1) Voice Onset; (2) Making Sense of the Experience; (3) Turning Point; (4) Support-Seeking and; (5) Acceptance. These themes can be seen as common stages or phases through which all participants transited to develop control. Figure 2 depicts theme and subtheme trajectories for both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking groups. Verbatim from 2 representative participants are provided in table 7.

Fig. 2.

Trajectories of acceptance of voice-hearing experiences.

Voice Onset. In both groups, the onset of the voices carried feelings of surprise, perplexity, and distress. Negative and distressing experiences were more prominent in retrospective reports of treatment-seeking participants (table 7, Voice Onset, TS). By contrast, initial voice-hearing experiences were less distressing for non-treatment-seeking participants and were often interpreted as spirits or beings (table 7, Voice Onset, NTS).

Making Sense of the Experience. Two main explanatory frameworks were developed, corresponding to spiritual (table 7, Making Sense of the Experience, NTS) and pathologizing beliefs (table 7, Making Sense of the Experience, TS). Within the spiritual framework, predominant among individuals in the non-treatment-seeking group, participants identified the voices and other perceptual experiences as coming from spiritual beings (eg, angels, guides), dead people, or simply energy (table 6, Beliefs about the voices, NTS). Overall, the voices were positive, helpful, and often proffered important messages. An initially pathologizing framework was predominant among treatment-seeking participants, who reported their voice-hearing experiences as “wrong” or abnormal mental health experiences (table 7, Making Sense of the Experience, NTS). Finally, it is important to mention that some of the non-treatment-seeking participants’ voice-hearing experiences were initially seen as a mental health problem. However, this perspective was not later consolidated, and an alternate explanatory framework was adopted.

Turning Point: A turning point triggering the search for help or a new way to understand voice-hearing experiences was common across participants. Those employing a spiritual framework associated these turning points with a spiritual search or life crisis that may or may not have been distressing (table 7, Turning Point NTS), whereas for those with a pathologizing framework turning points often took the form of a mental health crisis (table 7, Turning Point TS).

Support-Seeking: Frequently, after the highly distressing periods characterizing the turning points, participants searched for help to cope with their voices, such as joining support groups or gathering information about their voice-hearing experiences. Being part of such a group allowed them to share their voice-hearing experiences openly, in a non-judgmental and supporting environment, thus contributing to a sense of community and normalization (table 7, Support-Seeking NTS and TS).

Acceptance: A final stage was often marked by acceptance of voice-hearing experiences, derived frequently through social support. Non-treatment-seeking participants described peer groups as places in which they shared their experiences, practicing and developing their skills (table 7, Acceptance, NTS). Many treatment-seeking participants found support and peer groups enabled them to share and resignify their experiences, develop a sense of community, and explore novel strategies to cope with the voices (table 7, Acceptance, TS). Acceptance of the enduring nature of voice-hearing experiences reduced the intensity of resistant behavior and emotions, allowing participants to develop strategies to gain control over voice-hearing experiences.

Inter-Group Differences

As described above, all participants transited through the 5 stages of development of control outlined. However, some aspects of individual trajectories of control varied by group and were influenced by comorbidities, phenomenology, and the explanatory frameworks employed.

For treatment-seeking participants, early interpretations of voice-hearing experiences as a mental health problem (whether driven by negative voice content or by social environment) shaped their initial response. Specifically, interactions with mental health professionals, receipt of diagnosis and prescription medications, as well as admission to acute care, shaped their conceptualization of voice-hearing experiences [TS12: “Until I got hospitalized and someone asked me about voices and I’m like “yeah” ... I went to the hospital, they made me feel ashamed about it...they drugged me up with a lot of medications and so it was never talked about it again…”]. This often fostered the development of indirect control over their voice-hearing experiences via changes in the immediate environment and focus of attention, which were often ineffective, further reducing a sense of control over experiences. Participating in support groups helped them to accept their voice-hearing experiences and explore other techniques to engage with and exert direct control over their voice-hearing experiences. Non-treatment-seeking participants were more likely to interpret their voices within a spiritual framework or as a gift that enabled communication with spirits or guides (table 3 and table 6, Beliefs about the voices) and were more likely to report family members that also heard voices [NTS 1":Yeah, so I started to kind of hear voices or hear things since I was a little girl... during dreams I would hear either beings or spirits or I don’t really know what they were. I guess as I have gotten older I understood a little bit more...It wasn’t until my grandmother...started to come to America ...I was able to understand it was a higher being talking to me...Just as she was praying, I was praying when I was talking to these beings, but I was also hearing their voices back, I was listening to what they had to say to me.”]. Control over voice-hearing experiences for non-treatment-seeking participants allowed them to regulate the connection with their guides/spirits and keep messages from coming through when they were unwanted or dangerous [TS 14: “I guess when I was a senior--no, junior--in high school....I always had these fears of certain things, like weather, more, all these obnoxious fears... [the voices] weren’t ever really mean or derogatory, it was more of about things I was doing during the day, ... I’ve never experienced that before and I didn’t know how to handle it, or what to do with it... So I tried to keep it under control, for as long as I could until it was obviously very noticeable that something was wrong.”].

Discussion

Results of our analyses revealed significant commonalities in the development of control over voice-hearing experiences in both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers. These commonalities included the types of control exhibited, the factors extrinsic to control that influenced those abilities, and the trajectories through which participants passed in pursuit of developing agency over their experiences. Nonetheless, key differences also pertained, including initial beliefs about voice-hearing and the degree to which each group interacted with the psychiatric system.

In their seminal book, Slade and Bentall define hallucinations as not “susceptible to being voluntarily directed or controlled by those who experience [them]”.49 However, as we50 and others51 have argued, the existence of hallucinations that are susceptible to delusional and affective content itself challenges the assumptions of strict modularity underlying this statement in favor of Bayesian accounts of perception.52 These accounts have recently led to insights into the potential for hallucinations to arise from overly-weighted expectations relative to sensory evidence.14,15,48,53–55 This formulation may also yield insight into how direct voluntary control over voice-hearing may be possible. High-level expectations regarding internal and external states may influence the likelihood of overly weighting one’s expectations about hearing a voice.56,57 Engagement with voices—a strategy employed universally by those with direct control in our sample—may drive social learning and evolution of these expectations, which in turn could influence the precision of priors around hearing a voice.

The findings we present here speak strongly in favor of development of control abilities in both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers: both groups of voice-hearers reported remarkably similar steps in the development of voluntary control over voice-hearing experiences. Those inclined toward a spiritual explanatory framework exhibited an earlier transition toward control. This may be related directly to participants’ beliefs about the possibility of control and the degree to which their explanatory framework promotes suppression or engagement as a dominant strategy. This again supports previously-reported relationships between meaningful engagement with voices and likelihood of good functional outcomes.17,58–61 Psychological therapies for individuals reporting voice-hearing experience, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Psychosis (CBTp)62–64 and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)65–68 have focused on changing one’s relationship with their voices.69 The results of the current study identify component processes that lead to distinct control abilities. This knowledge may aid in the development and optimization of specific techniques to enhance control abilities by harnessing the processes that led to their development in our sample.

The results reported here indicate that development of control over voice-hearing experience voice-hearing experiences, or the ability to intentionally influence one’s functioning and life circumstances.70 Greater control over voice-hearing experience may improve one’s personal efficacy, which previous research has identified as closely linked to a sense of agency.70 Conversely, results of the current study highlight that efficacy in control over voice-hearing experience is strongly influenced by specific activities (such as those involved in self-care) that may themselves reflect a general sense of agency. Nonetheless, there may be danger in representing control over voice-hearing experiences as something all voice-hearers should be able to develop, leading some to feel deficient because they have tried and have found themselves unable to develop them. However, given that disruptions in one’s sense of agency due to psychopathology have significant implications for quality of life,71 these abilities may be helpful for recovery in some voice-hearers.

Several critical questions remain about the processes discussed here. It remains unclear what roles semantic content and valence play in the development of control over voice-hearing experience. Previous research focusing on semantic content, syntactical structure, and affective valence of voice-hearing experience have found significant differences between treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers in these domains.9,72 We replicate these findings here, as demonstrated in our quantitative scales (table 3, BAVQ-R Malevolence) as well as content from semi-structured interview transcripts (table 4). These differences may have played a significant role in the differing explanatory frameworks and specific control techniques employed. However, despite any differences in the content of or affective response to voice-hearing experiences, results of the current study indicate broad-ranging and significant commonalities in types of control exhibited, factors influencing control, and trajectories of control development in both treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers. Nonetheless, future studies exploring the development of control in voice-hearing experiences would benefit from formal inclusion of content, valence, and linguistic structure of voice-hearing experiences as possible moderators or mediators in the development of control. Future studies may also find benefit in elucidating the relationship between direct control and voice onset and offset, as previous work has highlighted a relationship between these variables.73 Additionally, lifetime incidence of multimodal hallucinations is twice that of unimodal ones in help-seeking populations,74,75 and understanding modality-specific and supra-modal facets of control may be essential.

Some of the techniques described here as enhancing control abilities have also been described in the extant literature as part of therapeutic approaches to psychosis. Coping strategies have been important features of psychological therapies for psychosis for decades, and have offered extremely important insights into non-pharmacological approaches for functional improvement in voice-hearing. Recent efforts have sought to further improve the efficacy of coping strategies by better characterizing psychological processes and cognitive mechanisms underlying voices and their amelioration (see ref.21 for an excellent review). Our efforts here represent one step in this direction by choosing to focus on voluntary control abilities rather than the broad range of coping strategies meant to improve general functioning in voice-hearing. Focusing specifically on control allows for the formation of hypotheses regarding specific cognitive, computational, and neural processes that underlie subsets of control abilities, processes that may be targeted and improved via biological and psychotherapeutic interventions in the future.

We characterize specific abilities to voluntarily influence the timing, frequency, and/or intensity of voice-hearing experiences directly by interaction with the voices or indirectly through some intermediary action. The choice to focus on these abilities was inspired by differences commonly identified to exist between clinical and non-clinical voice-hearers. Despite important differences between the experiences between these groups, we demonstrate that some of the same abilities may be developed in both groups, in a very similar pattern. We are not alone in attempting to leverage differences between non-clinical and clinical voice-hearing populations to improve clinical standing: recent therapeutic efforts (eg, ACT, Person-Based Cognitive Therapy for Psychosis) have focused on altering beliefs around the omnipotence and malevolence of voices, inspired directly by differences in these beliefs between treatment-seeking and non-treatment-seeking voice-hearers.

Our study has several limitations. Although sampling was guided by data saturation (as is typical in qualitative studies), our sample size is modest by quantitative standards. Additionally, participants were recruited from only 2 organizations and the analyzed sample skewed female, potentially resulting in early data saturation. Several questions remain open to be explored, such as the role of mental health diagnoses, comorbidities, and voice content in shaping the trajectories and strategies to control voice-hearing experiences voice-hearing experiences. In that same vein, it would have been helpful to ascertain participants’ functional status and to examine its role in the development and maintenance of control. We contend that functional status, as well as current psychiatric status as rendered from a clinician-administered semi-structured interview, may aid in the applicability of the current findings to specific clinical populations. Additionally, it would be helpful to determine if participants’ self-reported level of control is consistent with clinician ratings of said control. Lastly, voice-hearing is a dynamic phenomenon, and so is control over voice-hearing experiences. Control itself may be influenced by stressful life events, changes in voice content, or the explanatory framework employed. Future work should focus specifically on changes in control over time; interviewing non-treatment-seeking participants to understand whether changes in voice content may lead to an emergent need for care would be particularly valuable.

The degree to which researchers are able to measure type and degree of control over voice-hearing experiences is severely limited by the instruments currently available. Reliable and valid voice-hearing experiences control measures may allow for development and optimization of effective interventions based on enhancing that control. Results of the present study offer a requisite first step in characterizing control in these populations, as well as documenting key differences in the development and progression of agency in voice-hearing experiences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Hale Jaeger, Ely Sibarium, and Allison Hammer for their editorial advice. The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

Funding

This work was supported by K23 Career Development Award from the National Institute of Mental Health (K23 MH115252-01A1), by a Career Award for Medical Scientists from the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund, awarded to A.R.P., and by the Yale Department of Psychiatry and the Yale School of Medicine. E.K. receives support from the Yale Science, Technology, and Research Scholars II (STARS II) program, itself supported by the Yale College Dean’s Office and Yale University. A.M.N. received support through the Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Achievement postdoctoral fellowship program.

References

- 1. Beavan V. Towards a definition of “hearing voices”: a phenomenological approach. Psychosis. 2011;3(1):63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Badcock JC, Chhabra S. Voices to reckon with: perceptions of voice identity in clinical and non-clinical voice hearers. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strauss JS. Hallucinations and delusions as points on continua function. Rating scale evidence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1969;21(5):581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. van Os J, Linscott RJ, Myin-Germeys I, Delespaul P, Krabbendam L. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the psychosis continuum: evidence for a psychosis proneness-persistence-impairment model of psychotic disorder. Psychol Med. 2009;39(2):179–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Os J, Reininghaus U. Psychosis as a transdiagnostic and extended phenotype in the general population. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(2):118–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Verdoux H, van Os J. Psychotic symptoms in non-clinical populations and the continuum of psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2002;54(1-2):59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brett CM, Peters ER, McGuire PK. Which psychotic experiences are associated with a need for clinical care? Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(5):648–654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Powers AR III, Kelley MS, Corlett PR. Varieties of voice-hearing: psychics and the psychosis continuum. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(1):84–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daalman K, Boks MP, Diederen KM, et al. The same or different? A phenomenological comparison of auditory verbal hallucinations in healthy and psychotic individuals. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):320–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hill K, Varese F, Jackson M, Linden DE. The relationship between metacognitive beliefs, auditory hallucinations, and hallucination-related distress in clinical and non-clinical voice-hearers. Br J Clin Psychol. 2012;51(4):434–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Larøi F. How do auditory verbal hallucinations in patients differ from those in non-patients? Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Baumeister D, Sedgwick O, Howes O, Peters E. Auditory verbal hallucinations and continuum models of psychosis: a systematic review of the healthy voice-hearer literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;51:125–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Leede-Smith S, Barkus E. A comprehensive review of auditory verbal hallucinations: lifetime prevalence, correlates and mechanisms in healthy and clinical individuals. Front Hum Neurosci. 2013;7:367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Powers AR, Mathys C, Corlett PR. Pavlovian conditioning-induced hallucinations result from overweighting of perceptual priors. Science. 2017;357(6351):596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Alderson-Day B, Lima CF, Evans S, et al. Distinct processing of ambiguous speech in people with non-clinical auditory verbal hallucinations. Brain. 2017;140(9):2475–2489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Daalman K, Sommer IE, Derks EM, Peters ER. Cognitive biases and auditory verbal hallucinations in healthy and clinical individuals. Psychol Med. 2013;43(11):2339–2347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chandwick P, Lees S, Birchwood M. The revised Beliefs About Voices Questionnaire (BAVQ-R). Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:229–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kråkvik B, Stiles T, Hugdahl K. Experiencing malevolent voices is associated with attentional dysfunction in psychotic patients. Scand J Psychol. 2013;54(2):72–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Peters ER, Williams SL, Cooke MA, Kuipers E. It’s not what you hear, it’s the way you think about it: appraisals as determinants of affect and behaviour in voice hearers. Psychol Med. 2012;42(7):1507–1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Shergill SS, Murray RM, McGuire PK. Auditory hallucinations: a review of psychological treatments. Schizophr Res. 1998;32(3):137–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Thomas N, Hayward M, Peters E, et al. Psychological therapies for auditory hallucinations (voices): current status and key directions for future research. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl 4):S202–S212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Daalman K, Verkooijen S, Derks EM, Aleman A, Sommer IE. The influence of semantic top-down processing in auditory verbal hallucinations. Schizophr Res. 2012;139(1-3):82–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. de Weijer AD, Neggers SF, Diederen KM, et al. Aberrations in the arcuate fasciculus are associated with auditory verbal hallucinations in psychotic and in non-psychotic individuals. Hum Brain Mapp. 2013;34(3):626–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Diederen KM, van Lutterveld R, Sommer IE. Neuroimaging of voice hearing in non-psychotic individuals: a mini review. Front Hum Neurosci. 2012;6:111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Diederen KM, De Weijer AD, Daalman K, et al. Decreased language lateralization is characteristic of psychosis, not auditory hallucinations. Brain. 2010;133(Pt 12):3734–3744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Slotema CW, Daalman K, Blom JD, Diederen KM, Hoek HW, Sommer IE. Auditory verbal hallucinations in patients with borderline personality disorder are similar to those in schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 2012;42(9):1873–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Laroi F, Van Der Linden M. Nonclinical participants’ reports of hallucinatory experiences. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science/Revue canadienne des Sciences du comportement. 2005;37(1):33–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Andrew EM, Gray NS, Snowden RJ. The relationship between trauma and beliefs about hearing voices: a study of psychiatric and non-psychiatric voice hearers. Psychol Med. 2008;38(10):1409–1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Daalman K, van Zandvoort M, Bootsman F, Boks M, Kahn R, Sommer I. Auditory verbal hallucinations and cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Schizophr Res. 2011;132(2-3):203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Honig A, Romme MA, Ensink BJ, Escher SD, Pennings MH, deVries MW. Auditory hallucinations: a comparison between patients and nonpatients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1998;186(10):646–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Romme M, Escher S. Making Sense of Voices: The Mental Health Professional’s Guide to Working with Voice-Hearers. London, UK: Mind Publications; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Romme M, Escher S, eds. Accepting Voices. London, UK: Mind Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Romme MA, Honig A, Noorthoorn EO, Escher AD. Coping with hearing voices: an emancipatory approach. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;161:99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Falloon IR, Talbot RE. Persistent auditory hallucinations: coping mechanisms and implications for management. Psychol Med. 1981;11(2):329–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bentall RP, Haddock G, Slade PD. Cognitive behavior therapy for persistent auditory hallucinations: from theory to therapy. Behav Ther. 1994;25(1):51–66. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Roxburgh EC, Roe CA. Reframing voices and visions using a spiritual model. An interpretative phenomenological analysis of anomalous experiences in mediumship. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2014;17(6):641–653. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Taylor G, Murray C. A qualitative investigation into non-clinical voice hearing: what factors may protect against distress? Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2012;15(4):373–388. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Roxburgh EC, Roe CA. A survey of dissociation, boundary-thinness, and psychological wellbeing in spiritualist mental mediumship. J Parapsychol. 2011;75(2) http://nectar.northampton.ac.uk/11011/. Accessed February 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Haddock G, McCarron J, Tarrier N, Faragher EB. Scales to measure dimensions of hallucinations and delusions: the psychotic symptom rating scales (PSYRATS). Psychol Med. 1999;29(4):879–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. The Connecticut Hearing Voices Network (CT-HVN). Connecticut Hearing Voices Network. CT Hearing Voices Network https://www.cthvn.org/. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 41. Goodman LA. Snowball sampling. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1961;32(1):148–170. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Glaser BG. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Charmaz K, Henwood K. Grounded theory methods for qualitative psychology. In: Willig C, Rogers W, eds. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. London, UK: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2017:238–256. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Strauss AL, Corbin JM. eds. Grounded theory in practice. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bryant A. The Grounded Theory Method. In: Leavy P, ed. The Oxford Handbook of Qualitative Research. New York: Oxford University Press; 2014:115–136. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research. In: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Teufel C, Subramaniam N, Dobler V, et al. Shift toward prior knowledge confers a perceptual advantage in early psychosis and psychosis-prone healthy individuals. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112(43):13401–13406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Slade PD, Bentall RP. Sensory Deception: A Scientific Analysis of Hallucination. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Powers AR III, Kelley M, Corlett PR. Hallucinations as top-down effects on perception. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2016;1(5):393–400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Howe PD, Carter OL. Hallucinations and mental imagery demonstrate top-down effects on visual perception. Behav Brain Sci. 2016;39:e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Friston KJ. Hallucinations and perceptual inference. Behav Brain Sci. 2005;28(6):764–766. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Corlett PR, Horga G, Fletcher PC, Alderson-Day B, Schmack K, Powers AR III. Hallucinations and strong priors. Trends Cogn Sci. 2019;23(2):114–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cassidy CM, Balsam PD, Weinstein JJ, et al. A perceptual inference mechanism for hallucinations linked to striatal dopamine. Curr Biol. 2018;28(4):503–514.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Zarkali A, Adams RA, Psarras S, Leyland LA, Rees G, Weil RS. Increased weighting on prior knowledge in Lewy body-associated visual hallucinations. Brain Commun. 2019;1(1):fcz007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Benrimoh D, Parr T, Adams RA, Friston K. Hallucinations both in and out of context: an active inference account. PLoS One. 2019;14(8):e0212379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hohwy J. Priors in perception: top-down modulation, Bayesian perceptual learning rate, and prediction error minimization. Conscious Cogn. 2017;47:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Chadwick P. Two chairs, self-schemata and person based approach to psychosis. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2003;31(4):439–449. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Paulik G. The role of social schema in the experience of auditory hallucinations: a systematic review and a proposal for the inclusion of social schema in a cognitive behavioural model of voice hearing. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2012;19(6):459–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Hayward M, Berry K, McCarthy-Jones S, Strauss C, Thomas N. Beyond the omnipotence of voices: further developing a relational approach to auditory hallucinations. Psychosis. 2014;6(3):242–252. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Birchwood M, Meaden A, Trower P, Gilbert P, Plaistow J. The power and omnipotence of voices: subordination and entrapment by voices and significant others. Psychol Med. 2000;30(2):337–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sivec HJ, Montesano VL. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychosis in clinical practice. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2012;49(2):258–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Valmaggia LR, Tabraham P, Morris E, Bouman TK. Cognitive behavioral therapy across the stages of psychosis: prodromal, first episode, and chronic schizophrenia. Cogn Behav Pract. 2008;15(2):179–193. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Fowler D, Garety P, Kuipers E. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychosis: Theory and Practice. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Thomas N, Morris EMJ, Shawyer F, Farhall J. Acceptance and commitment therapy for voices. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness for Psychosis. 2013;210(2):95–111. [Google Scholar]

- 66. Oliver JE, Morris EMJ. Acceptance and commitment therapy for first-episode psychosis. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and Mindfulness for Psychosis. 2013;210(2):190–205. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Hayes SC, Lillis J. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Washington, DC: Theories of Psychotherapy; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Bunting K, Twohig M, Wilson KG. What is acceptance and commitment therapy? In: Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, eds. A Practical Guide to Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Boston, MA: Springer; 2004:3–29. [Google Scholar]

- 69. Morrison AP. Cognitive therapy for auditory hallucinations as an alternative to antipsychotic medication: a case series. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy. 2001;8(2):136–147. [Google Scholar]

- 70. Bandura A. Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2006;1(2):164–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Frith CD, Blakemore SJ, Wolpert DM. Abnormalities in the awareness and control of action. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1404):1771–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. de Boer JN, de Boer JN, Heringa SM, van Dellen E, Wijnen FNK, Sommer IEC. A linguistic comparison between auditory verbal hallucinations in patients with a psychotic disorder and in nonpsychotic individuals: not just what the voices say, but how they say it. Brain Lang. 2016;162:10–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Alderson-Day B, Smailes D, Moffatt J, Mitrenga K, Moseley P, Fernyhough C. Intentional inhibition but not source memory is related to hallucination-proneness and intrusive thoughts in a university sample. Cortex. 2019;113:267–278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Montagnese M, Leptourgos P, Fernyhough C, et al. A review of multimodal hallucinations: categorisation, assessment, theoretical perspectives and clinical recommendations. Schizophr Bull. sbaa101. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbaa101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Waters F, Fernyhough C. Hallucinations: a systematic review of points of similarity and difference across diagnostic classes. Schizophr Bull. 2017;43(1):32–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.