Abstract

Background:

Previous studies indicate that taste dysfunction occurs early in the development of Alzheimer’s Disease. It is debatable whether the deficit in taste is due primarily to peripheral sensory mechanisms or to central processing, or a combination of the two.

Objective:

The aim of our current study is to combine behavior and histological data in APP/PS1 transgenic mice to determine whether APP/PS1 transgenic mice show deficits in unconditioned taste preference and avoidance behaviors and whether taste impairments are due to defects in the peripheral taste system and/or problems with central processing of taste information.

Methods:

The APP/PS1 transgenic mutant mice were used as a model of Alzheimer’s Disease. We employed a brief-access gustometer test to assess immediate orosensory taste responses of APP/PS1 mice. We used immunohistochemistry to examine tongue, gustatory ganglion, and brain tissues to determine a cytological basis for behavioral deficits.

Results:

There is a significant, selective reduction of bitter taste sensitivity in APP/PS1 mice. These mice also have a loss of TRPM5-expressing taste receptor cells in the circumvallate papillae of the tongue. While we observed no overt loss of neuron cell bodies within the primary gustatory sensory neurons, degeneration of the neurons’ peripheral axons innervating the taste bud may play a role in the observed loss of TRPM5-expressing taste receptor cells.

Conclusion:

This data supports a potential role for peripheral taste dysfunction in AD through the selective loss of taste receptor cells. Further study is necessary to delineate the mechanisms and pathological significance of this deficit in AD.

Keywords: Taste dysfunction, taste receptor cells, APP/PS1 mutant

Introduction:

Sensory dysfunction such as gustatory deficit often precedes the cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and other neurodegenerative diseases [1–4]. It is not clear whether such sensory deficits are directly linked to the pathogenic development of AD. Examining the deterioration in sensory function may help to understand the progression of AD and develop methods for early detection that may improve patient outcomes. A significant loss in taste has been reported in AD patients [5–9]. Specifically, both taste recognition and detection thresholds of specific tastants have been reported in AD patients [2–4, 10]. Although studies have postulated that these deficits are due to the deterioration of central processing related to AD pathology [4, 10], others indicate that peripheral sensory and other non-cognitive impairments may also play a role [1, 11]. To our knowledge, there has been no study that directly tests whether this defect is caused primarily by central processing, peripheral sensory mechanisms, or a combination of the two.

The mammalian taste system detects nutrients (salts, carbohydrates, and amino acids) and warns of potentially harmful substances (acids, toxins) within a meal. Specialized taste receptor cells (TRCs) housed within the fungiform and circumvallate papilla structures on the surface of the tongue express specific taste receptors to detect the chemicals within food. TRCs are neuroepithelial cells, which have a finite lifespan of ~7–14 days and continually turn over within the taste bud. When a tastant is detected on the tongue, the TRCs signal to the peripheral gustatory sensory neurons that innervate the taste buds. The cell bodies of these neurons are located within the geniculate and petrosal ganglia; their peripheral axons innervate TRCs and their central axons terminate within the brainstem. Within the CNS, taste information is processed in a series of relays from the brainstem, to the thalamus, and then to the gustatory cortex [12].

The aim of our current study is to combine behavior and histological data in APP/PS1 transgenic mice to determine two key points. First, determine whether APP/PS1 transgenic mice show deficits in unconditioned taste preference and avoidance behaviors. The APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model [13, 14] expresses chimeric mouse/human mutant amyloid precursor protein (Mo/HuAPP695swe) and the PS1-dE9 mutant human presenilin 1 (PS1) and develops multiple AD-related pathologies including the accumulation of amyloid-β (Aβ). We employed a brief-access gustometer test to assess immediate orosensory taste responses of APP/PS1 mice and age matched controls to sweet, bitter, salty, and sour tastants. Second, we wanted to determine whether taste impairments are due to defects in the peripheral taste system and/or problems with central processing of taste information. For this, we used immunohistochemistry to examine tongue, geniculate ganglion, and brain tissues to determine a cytological basis for the behavioral deficit.

Methods:

Animals:

We used APP/PS1 double transgenic mice that express a chimeric mouse/human amyloid precursor protein and a mutant human presenilin [14] (JAX Stock #004462). We tested APP/PS1 mice ranging from 12-14 months of age (four males, one female), and compared them with five age-matched control littermates (four males, one female). These transgenic mice develop Aβ deposits in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex starting at 6 months of age.

Behavior Tests:

Brief-access lickometer taste tests on the APP/PS1 and control mice were performed using a multichannel gustometer (Davis MS160-Mouse gustometer; MedAssociates). Mice were water deprived for 24 hours before training. Initially mice were acclimated to receiving water from the gustometer spouts, trained twice a day for 1 week prior to testing. The mice were tested with four tastants (Sweet = Sucrose; Bitter = Quinine; Sour = Citric Acid; Salty = NaCl) within a two week period after training. Mice were placed into the chamber for 10 minutes duration. The test consisted of one tastant at five different concentrations presented in pseudo-random order. A shutter opens and presents the mouse with one spout, the mouse has a 60 second window to lick this, otherwise it will proceed to the next trial. Upon the first lick, the mouse was allowed to continue licking for 10 seconds. Number of licks, inter-lick interval and lick latency were recorded in each trial. Each experimental day, the mice were given an aversive taste (quinine or citric acid) in the morning session and an attractive taste (sucrose or NaCl) in the afternoon session. The first two seconds were removed from each session to account for thirst. The remaining licks from each session were averaged for each mouse (N=5). The percentage of licks for a tastant concentration were calculated by taking the remaining licks for a specific tastant concentration over the total remaining licks for that tastant. These percentages were then averaged for each genotype (APP/PS1 versus control).

Tissue Preparation:

Both APP/PS1 and control mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and perfused with 15 ml PBS followed with 15 ml 4% paraformaldehyde solution. The brain, geniculate ganglion, and tongue tissues were collected The brain was stored in 4% paraformaldehyde solution and the geniculate ganglion, nodose and tongue was stored in 30% sucrose solution overnight at 4°C for cryoprotection. Brains were then sectioned at 100 μm with a vibratome apparatus (TPI). Brain slices were collected at the coordinates for the sweet and bitter cortex (around bregma 1.6 and −0.3) and were used for immunohistochemical analysis. The geniculate ganglion and tongue were embedded in OCT compound and sectioned at 15 μm thickness on a cryostat.

Immunohistochemistry:

Sections of tongue, nodose/petrosal, and geniculate ganglion were washed with blocking buffer (10% donkey serum in 1xPBS). Primary antibodies for TRPM5 and Car4 in 10% donkey serum in 1xPBS were added to the tongue circumvallate papillae (CV) sections. Primary antibodies for Phox2B and P2X3 in 10% donkey serum in 1xPBS; 0.3% triton were added to the geniculate sections. Slides were stored overnight at 4 °C. Sections were then washed with 1xPBS three times, 5 minutes each. Secondary antibodies were diluted in 10% donkey serum in 1xPBS were added to Tongue sections (1:1000 dilution). 1:500 Nissl (NeuroTrace 640/660 deep-red fluorescent Nissl stain from Invitrogen) were added to geniculate sections during the secondary antibody incubation period. Brain sections were washed with blocking buffer (10% donkey serum in 1xPBS, 0.1% Triton X-100 ) for 1 hour at 4°C in a 24 well plate. The sections were then stained with 1:500 anti- Aβ primary antibody in blocking buffer overnight at 4°C then washed with 1xPBS three times, 15 minutes each. Secondary antibody staining was done with 1:500 Nissl in blocking buffer for 1 hour at 4°C. Sections were then washed with 1xPBS three times, 15 minutes each. Stained brain sections were then transferred to slides. All slides were coverslipped and mounted with hard set mounting media (Vectashield hard set H-1400 from Vector Laboratories). Primary antibodies used were: anti-TRPM5 (Zuker Lab, 1:500 dilution [15]), anti-Car4 (R&D Systems AF2414, 1:200 dilution), anti-P2X3 (Neuromics GP10108, 1:1000) anti-Aβ (82E1, IBL, 1:500 dilution). Secondary antibodies used were from Jackson Immuno Research, 1:1000 dilution.

Imaging and Quantification:

Zeiss 710 confocal microscope was used to image brain, tongue, nodose/petrosal, and geniculate sections. For image analysis ImageJ was used. 203 taste buds across 10 mice were examined by looking for TRPM5 and Car4 expression. Each cell labeled were counted in the CV sections of the tongue. For geniculate and nodose sections, Image-pro’s cell count function was used to count the Phox2B, P2X3 and Nissl stained cells. Two-way Student’s t-Test were used for statistical analysis.

Results:

APP/PS1 mice show a deficit in bitter taste response.

In order to see if there were any taste deficits in APP/PS1 mice, we used a brief-access lickometer taste test. We placed both APP/PS1 and control mice individually into a Davis multichannel gustometer with a single tastant (sweet, sour, bitter, or salty) serially diluted in five concentrations. These concentrations were presented in pseudo-random order while we recorded the number of licks for each presentation (Figure 1A). We used quinine for bitter taste, citric acid for sour, sucrose for sweet, and sodium chloride for salty.

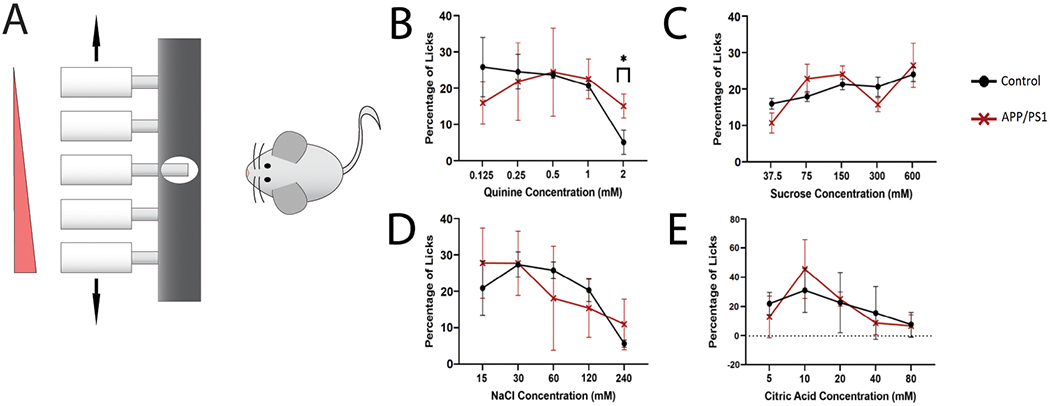

Figure 1: Behavioral analysis of gustatory sensation in APP/PS1 and control mice.

(A) Illustration of experimental setup. Animals were tested using a brief-access lick assay with pseudo-random presentation of each tastant concentration. (B-E) Dose response to the tastants in control and APP/PS1 mice. Shown are the relative fraction of licks to each concentration of tastant. (B) Bitter, Quinine (0.125 mM, 0.25 mM, 0.5 mM, 1 mM, 2mM). (C) Sweet, sucrose (37.5 mM, 75 mM, 150 mM, 300 mM, 600 mM). (D) Salty, Sodium Chloride (15 mM, 30 mM, 60 mM, 120 mM, 240 mM). (E) Sour, Citric Acid (5 mM, 10 mM, 20 mM, 40 mM, 80 mM). (*p<0.05, n=5/group).

The majority of the dose-dependent lick responses did not differ significantly between APP/PS1 mice and age matched control littermates (Figure 1B–E). However, the APP/PS1 mice did show a decreased aversion to the bitter compound quinine compared to controls (Figure 1B). The APP/PS1 licked 2 mM quinine at a significantly higher percentage than the controls (Student’s T-test, p<0.05). Even at this high concentration, the APP/PS1 mice showed only a moderate decrease in licking while the control mice showed almost complete aversion to this concentration of bitter.

The APP/PS1 and control mice displayed similar responses to sucrose, NaCl, and citric acid, showing a dose-dependent increase in licking to higher concentrations of sucrose, and a dose-dependent decrease in licking to higher concentrations of NaCl and citric acid (Figure 1C–E). We note that both cohorts of mice show a less defined dose-dependent response to sucrose than is usually observed [16]. This could possibly be due to the levels of thirst of the mice.

Loss of TRPM5-expressing cells in the circumvallate papillae of the tongue in APP/PS1 mice

What might cause this specific deficit in bitter taste sensitivity in APP/PS1 mice? Starting with the peripheral taste system, we examined the circumvallate papillae of the tongue. We quantified the numbers of TRPM5 and Car4 expressing cells to see if there were any changes within these populations in the tongue. TRPM5 is expressed within the bitter, sweet and umami populations of taste receptor cells [15], whereas Car4 is expressed within the sour taste receptor cell population [17]. Using these two markers allows us to assess the majority of the taste receptor cells within the taste bud, with the exception of salty cells.

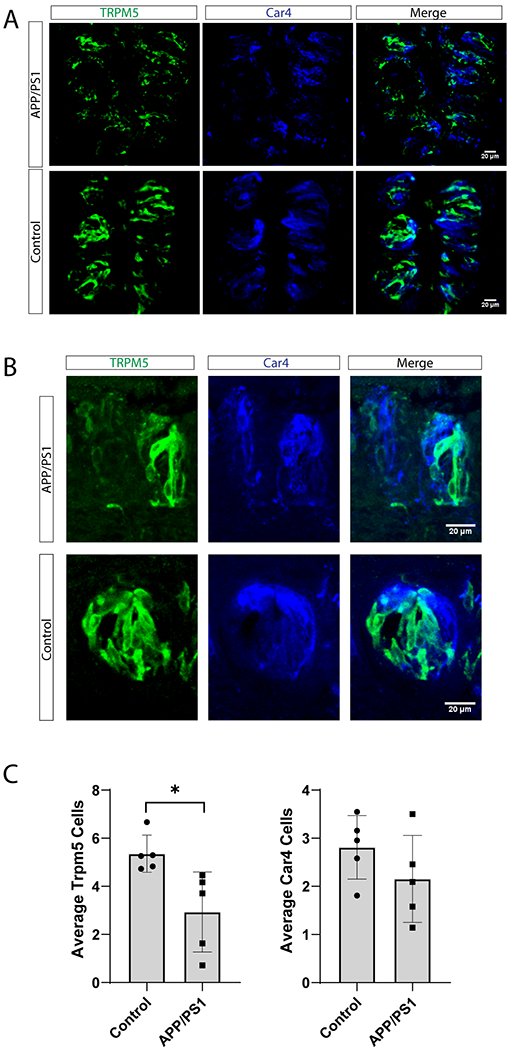

We used immunofluorescence staining of both TRPM5 and Car4 in the taste buds in circumvallate papillae of the APP/PS1 and control mice (Figure 2A–B). We quantified 109 taste buds in the APP/PS1 group, and 94 taste buds in the age-matched controls. An average of 20 taste buds were analyzed per mouse. There was a significant decrease in TRPM5 cells in the APP/PS1 model (p<0.05, Figure 2C). The reduction of TRPM5 cells may be due to a selective loss of the bitter TRCs, which may explain the bitter behavior deficit observed in the APP/PS1 mice. We did not find any significant difference in the Car4-expressing cells (p>0.05, Figure 2C), which agrees with our behavioral test showing no deficits in sour taste.

Figure 2: Quantification of TRPM5- and Car4- expressing TRCs within the circumvallate papillae in APP/PS1 and control mice.

(A-B) Confocal microscopy images of circumvallate papilla (CV) taste buds from APP/PS1 and control mice demonstrating expression of TRPM5 (a marker of sweet, bitter, and umami TRCs, green) and Car4 (expressed in sour TRCs, blue). (A) 10x images, scale bar = 20 μm. (B) 20x images, scale bar = 20 μm (C) The average number of TRPM5 and Car4-expressing cells per taste bud in APP/PS1 and controls. A total of 203 taste buds were analyzed for each group (12-22 Taste buds per mouse). (*p<0.05, n=5 /group).

Quantification of sensory neurons responsible for taste in the geniculate ganglion

After noticing a loss of TRPM5-expressing cells in the APP/PS1 mice, we wanted to determine if cell loss also occurred in the neurons of the geniculate and nodose/petrosal ganglion. The geniculate ganglion houses the cell bodies of the sensory neurons that relay taste information from the anterior tongue to the brainstem. Neurons of the nodose/petrosal complex of the vagal ganglion innervate the CV. Innervation of the taste buds by these sensory afferent fibers provides trophic factors that are necessary to maintain taste buds [18, 19]. In order to look specifically at the population of sensory neurons related to taste, we used immunostaining for Phox2b. Phox2b is a marker for the population of geniculate ganglion neurons that project to the taste buds [20]. In addition, we stained for P2rx3 which is expressed in subpopulations of both gustatory and somatosensory neurons within the geniculate [21], and Nissl stain was used to quantify the total numbers of neurons within the ganglion (Figure 3A).

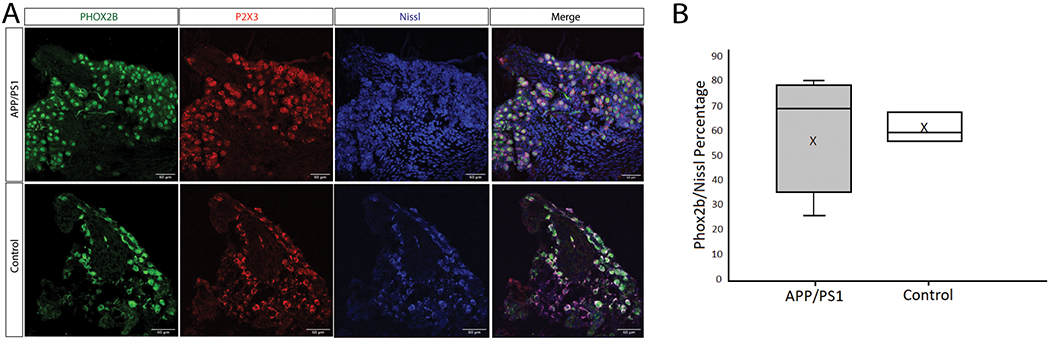

Figure 3: Geniculate ganglion phenotype of (APP/PS1) and C57 (Control) mice.

(A) Confocal microscopy images of geniculate ganglion immunostains illustrating the expression of Phox2b (Green), P2X3 (Red) and Nissl (Blue) in APP/PS1 and control mice. 40x images, scale bar = 60 μm. (B) Quantification of the average number of Phox2b + labeled neurons within the total number of neurons in the field (determined by Nissl staining of neuronal nuclei) in APP/PS1 and control tissues (p>0.05, n=5 for APP/PS1, n=3 for control).

We were unable to detect a significant difference in the relative percentage of Phox2b labeled cells within the geniculate ganglion between the APP/PS1 and control mice (Figure 3B). There also does not appear to be a difference in the proportion of gustatory neuron and somatosensory neuron cell populations in the geniculate ganglion in these mice. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the Phox2b populations in the nodose/petrosal ganglion (Control, 81% +/− 13.5% n=3; APP/PS1, 70% +/− 9.7% n=4; p>.05, Student’s T-test). This suggests that there is no overt loss of gustatory ganglion neurons in APP/PS1 mice.

Accumulation of Aβ in sweet and bitter gustatory cortical areas

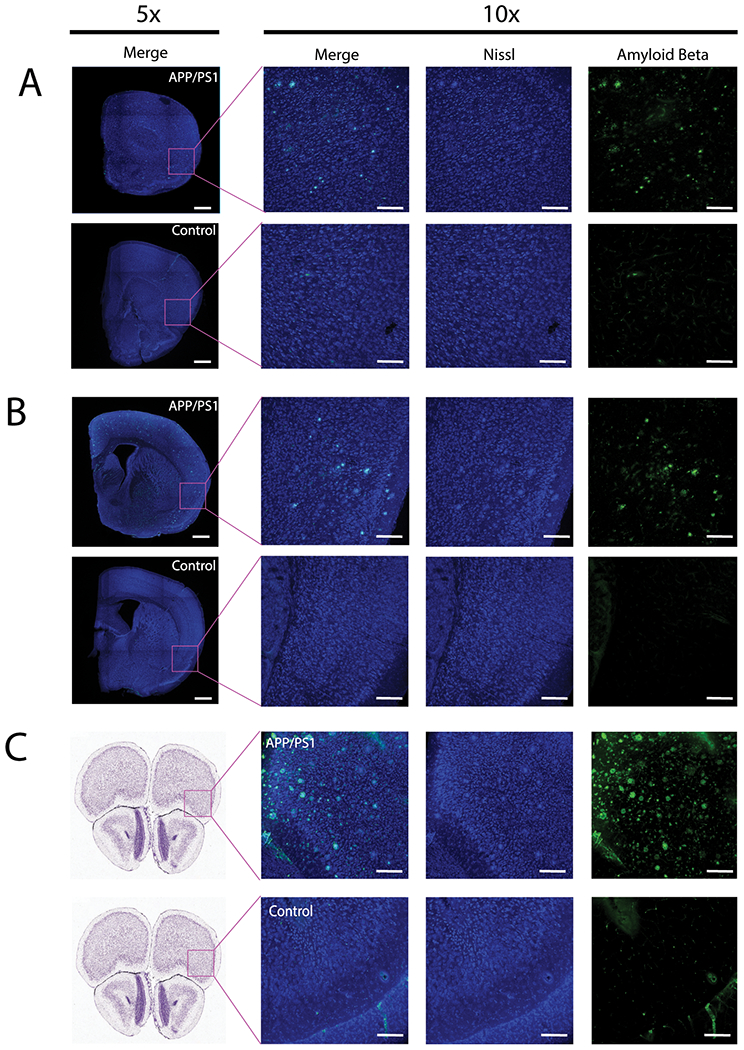

Next, we examined if there was overt pathology in the gustatory cortex of APP/PS1 mice that may contribute to the decrease in bitter taste sensitivity. It has been demonstrated that olfactory deficits in APP/PS1 are associated with increased Aβ deposits in the olfactory bulb, which contributes to neuronal atrophy and results in an impairment of dendrodendritic inhibition [5, 22, 23]. We analyzed APP/PS1 mutant and control brains specifically in the areas responsible for sweet and bitter taste in the gustatory cortex (Figure 4A, B) [24]. We stained for both Aβ and Nissl to see if these areas had an accumulation of Aβ that could affect taste perception. We compared the pattern of Aβ deposits in the gustatory cortex to the anterior insula (Figure 4C), which is known to have more severe Aβ accumulation in APP/PS1 transgenic mice [25].

Figure 4: Aβ pathology in the sweet and bitter areas of the gustatory cortex.

(A-C) Confocal images of coronal brain sections immunostained with Nissl (blue) and anti-Aβ (82E1) antibody (green). (A) Whole section (5x) and magnified field (10x) of the sweet cortical field (bregma 1.6mm; lateral 3.1mm; ventral 1.8mm) in the gustatory cortex. (B) Whole section (5x) and magnified view (10x) of the Bitter cortical field (bregma −0.3mm; lateral 4.2mm; ventral 2.8mm) in the gustatory cortex. (C) Whole section (Allen Brain Atlas Images) and magnified view (10x) of rostral frontal cortex (bregma 2.745) highlighting strong positive and negative phenotype for APP/PS1 and control brain sections. 5x images scale bars are 1000um. 10x images scale bars are 200 μm.

We were able to see an even distribution of Aβ deposits within both sweet and bitter regions of the gustatory cortex, but not to the extent of Aβ deposits as seen in the anterior insula. The accumulation of Aβ deposits is similar in both sweet and bitter areas, which would be unlikely to cause a specific bitter cortical taste deficit in the APP/PS1 mice. These findings lead us to believe that the selective deficit in bitter taste aversion is unlikely due to the insoluble Aβ deposits within the gustatory cortex, but rather caused by the selective degeneration of peripheral sensory cells.

Discussion:

Overall, our study shows the loss of bitter taste sensitivity in APP/PS1 mutant mice is likely caused by peripheral loss of taste receptor cells. While we cannot completely rule out the contribution of a central processing deficit in the APP/PS1 mice, the striking selective loss of TRPM5-expressing TRCs within the taste buds point to a peripheral sensory deficit. Since no distinct neuropathology was observed between the sweet and bitter regions of the gustatory cortex, this supports the idea that the origin of the deficit in bitter taste aversion is likely the degeneration of peripheral gustatory sensory cells in the tongue.

A significant loss of bitter taste receptor cells within this TRPM5 population correlates with the behavioral deficit seen in the APP/PS1 mice. Given what we know about the development and maintenance of TRCs within taste buds, there are several potential causes for the taste receptor cell loss we observe in APP/PS1 mice. These mechanisms include: 1) premature TRC cell death, 2) loss or decline of the taste stem cell population, and 3) loss or degeneration of sensory afferent nerve fibers innervating the taste buds.

Loss of taste sensitivity and the loss of taste receptor cells within the taste bud is associated with normal ageing [26, 27], and it is possible that the loss seen in the APP/PS1 mice could be accelerating the mechanisms of ageing in the tongue. Typically, age-related taste receptor cell loss and behavioral deficits are noticeable in ≥ 18 month-old mice. Also, it has been reported that in aged mice, sweet taste perception, not bitter, is the most affected [27]. Thus, at the ages we tested our cohort (12-14 months), no significant age-related taste dysfunction is typically observed [27].

Interestingly, there is evidence in humans that gustatory nerve innervation to the taste buds is reduced in AD patients [11]. This observation supports the hypothesis that AD leads to peripheral gustatory nerve degeneration which in turn reduces the trophic factors needed for taste receptor cell maintenance [18, 19]. While we did not observe a loss of gustatory neuron cell bodies within the geniculate or nodose/petrosal ganglion of APP/PS1 mice, there may be deterioration of the nerve terminals within the taste buds. Future study will be able to address this possibility.

APP/PS1 transgenic mice allow us to test whether the accumulation of Aβ is associated with taste dysfunction and detect it at each anatomical relay within the gustatory sensory system. In our experiment, the accumulation of Aβ is evident in both the sweet and bitter gustatory cortex, but not in either the tongue or the geniculate ganglion. Since only bitter, not sweet taste, was affected in APP/PS1 mice, this result suggests that the accumulation of Aβ in the gustatory cortex may not be the primary mechanism causing such specific taste deficit in APP/PS1 mice. Expression of the APP/PS1 transgene is dependent on the Prion Promoter, prnp. The transgenes are expressed at high levels in the CNS, but also in the PNS and other tissues including muscle [14]. In future work, we plan to investigate the levels of Aβ accumulation and soluble oligomeric Aβ in tongue and gustatory ganglion tissues that might cause sensory cell loss. In the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse line, amyloid accumulation progresses with age, and interestingly, female mice show increased amyloid burden and plaque formation compared to males [28]. It will be important in future studies to determine the age of taste deficit onset, and the relationship to amyloid accumulation in both male and female mice.

The deficit in bitter taste perception in APP/PS1 mice was observed using a brief-access behavioral assay. Even though this assay is meant to test immediate orosensory behaviors, the CNS is required to process the taste signals from the periphery and to coordinate a response such as licking or suppression of licking in the gustometer assay. There may also be more subtle deficits that are not significant enough to be detected by behavioral assessments. These subtle deficits may be examined by measuring the responses of the primary taste ganglion neurons by electrophysiological recordings or calcium imaging assays. In addition, since TRPM5 is also expressed in sweet and umami taste receptor cells, a specific label for bitter taste receptor can be used in future studies to further validate specific loss of the bitter TRC population. It will also be important to assess the chronology of taste dysfunction to uncover if taste deficits precede the pathological development in hippocampus and cerebral cortex in AD. If taste dysfunction occurs early in the progression of disease, taste tests could be developed for early diagnosis and intervention.

Collectively, we found a significant loss in bitter taste sensitivity in APP/PS1 mice. This deficit is associated with the loss of TRPM5-expressing cells in the tongue. We were unable to detect significant pathology in either the geniculate ganglion or gustatory cortices in the brain that would have contributed to this specific loss in bitter taste. This indicates that the taste dysfunction is likely due to a deficit in the peripheral taste system. Further studies into taste dysfunction in AD will help to determine the cause of this dysfunction and functional implications for the pathogenesis of AD, and also provide insights into developing taste-based assays that may improve early diagnosis of AD.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work has been provided in part by the Alzheimer’s Association AARG-16-440669 to H-G Lee and NIH-SC2-GM130411 and Brain Research Foundation Seed Grant to LJM.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

References:

- [1].Lang CJ, Leuschner T, Ulrich K, Stossel C, Heckmann JG, Hummel T (2006) Taste in dementing diseases and parkinsonism. J Neurol Sci 248, 177–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Sakai M, Ikeda M, Kazui H, Shigenobu K, Nishikawa T (2016) Decline of gustatory sensitivity with the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr 28, 511–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sakai M, Kazui H, Shigenobu K, Komori K, Ikeda M, Nishikawa T (2017) Gustatory Dysfunction as an Early Symptom of Semantic Dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 7, 395–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Steinbach S, Hundt W, Vaitl A, Heinrich P, Forster S, Burger K, Zahnert T (2010) Taste in mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurol 257, 238–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Churnin I, Qazi J, Fermin CR, Wilson JH, Payne SC, Mattos JL (2019) Association Between Olfactory and Gustatory Dysfunction and Cognition in Older Adults. Am J Rhinol Allergy 33, 170–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Doorduijn AS, de van der Schueren MAE, van de Rest O, de Leeuw FA, Fieldhouse JLP, Kester MI, Teunissen CE, Scheltens P, van der Flier WM, Visser M, Boesveldt S (2019) Olfactory and gustatory functioning and food preferences of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment compared to controls: the NUDAD project. J Neurol. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Doty RL (2018) Age-Related Deficits in Taste and Smell. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 51, 815–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Doty RL, Hawkes CH (2019) Chemosensory dysfunction in neurodegenerative diseases. Handb Clin Neurol 164, 325–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kouzuki M, Suzuki T, Nagano M, Nakamura S, Katsumata Y, Takamura A, Urakami K (2018) Comparison of olfactory and gustatory disorders in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurol Sci 39, 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Ogawa T, Irikawa N, Yanagisawa D, Shiino A, Tooyama I, Shimizu T (2017) Taste detection and recognition thresholds in Japanese patients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Auris Nasus Larynx 44, 168–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yamagishi M, Takami S, Getchell TV (1995) Innervation in human taste buds and its decrease in Alzheimer’s disease patients. Acta Otolaryngol 115, 678–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yarmolinsky DA, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ (2009) Common sense about taste: from mammals to insects. Cell 139, 234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Garcia-Alloza M, Robbins EM, Zhang-Nunes SX, Purcell SM, Betensky RA, Raju S, Prada C, Greenberg SM, Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP (2006) Characterization of amyloid deposition in the APPswe/PS1dE9 mouse model of Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Dis 24, 516–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jankowsky JL, Fadale DJ, Anderson J, Xu GM, Gonzales V, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Lee MK, Younkin LH, Wagner SL, Younkin SG, Borchelt DR (2004) Mutant presenilins specifically elevate the levels of the 42 residue beta-amyloid peptide in vivo: evidence for augmentation of a 42-specific gamma secretase. Hum Mol Genet 13, 159–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Mueller KL, Cook B, Wu D, Zuker CS, Ryba NJ (2003) Coding of sweet, bitter, and umami tastes: different receptor cells sharing similar signaling pathways. Cell 112, 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Zhao GQ, Zhang Y, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Erlenbach I, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS (2003) The receptors for mammalian sweet and umami taste. Cell 115, 255–266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Chandrashekar J, Yarmolinsky D, von Buchholtz L, Oka Y, Sly W, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS (2009) The taste of carbonation. Science 326, 443–445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Castillo-Azofeifa D, Losacco JT, Salcedo E, Golden EJ, Finger TE, Barlow LA (2017) Sonic hedgehog from both nerves and epithelium is a key trophic factor for taste bud maintenance. Development 144, 3054–3065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Yee C, Bartel DL, Finger TE (2005) Effects of glossopharyngeal nerve section on the expression of neurotrophins and their receptors in lingual taste buds of adult mice. J Comp Neurol 490, 371–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ohman-Gault L, Huang T, Krimm R (2017) The transcription factor Phox2b distinguishes between oral and non-oral sensory neurons in the geniculate ganglion. J Comp Neurol 525, 3935–3950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Zhang J, Jin H, Zhang W, Ding C, O’Keeffe S, Ye M, Zuker CS (2019) Sour Sensing from the Tongue to the Brain. Cell 179, 392–402 e315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].De la Rosa-Prieto C, Saiz-Sanchez D, Ubeda-Banon I, Flores-Cuadrado A, Martinez-Marcos A (2016) Neurogenesis, Neurodegeneration, Interneuron Vulnerability, and Amyloid-beta in the Olfactory Bulb of APP/PS1 Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Front Neurosci 10, 227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Yao ZG, Hua F, Zhang HZ, Li YY, Qin YJ (2017) Olfactory dysfunction in the APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease: Morphological evaluations from the nose to the brain. Neuropathology 37, 485–494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Peng Y, Gillis-Smith S, Jin H, Trankner D, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS (2015) Sweet and bitter taste in the brain of awake behaving animals. Nature 527, 512–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Choi J, Jeong Y (2017) Elevated emotional contagion in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease is associated with increased synchronization in the insula and amygdala. Sci Rep 7, 46262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Feng P, Huang L, Wang H (2014) Taste bud homeostasis in health, disease, and aging. Chem Senses 39, 3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Shin YK, Cong WN, Cai H, Kim W, Maudsley S, Egan JM, Martin B (2012) Age-related changes in mouse taste bud morphology, hormone expression, and taste responsivity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 67, 336–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Wang J, Tanila H, Puolivali J, Kadish I, van Groen T (2003) Gender differences in the amount and deposition of amyloidbeta in APPswe and PS1 double transgenic mice. Neurobiol Dis 14, 318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]