Abstract

In this cohort study, we aim to compare outcomes from coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in people with severe epilepsy and other co-morbidities living in long-term care facilities which all implemented early preventative measures, but different levels of surveillance.

During 25-week observation period (16 March–6 September 2020), we included 404 residents (118 children), and 1643 caregivers. We compare strategies for infection prevention, control, and containment, and related outcomes, across four UK long-term care facilities. Strategies included early on-site enhancement of preventative and infection control measures, early identification and isolation of symptomatic cases, contact tracing, mass surveillance of asymptomatic cases and contacts. We measured infection rate among vulnerable people living in the facilities and their caregivers, with asymptomatic and symptomatic cases, including fatality rate.

We report 38 individuals (17 residents) who tested severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-positive, with outbreaks amongst residents in two facilities. At Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE), 10/98 residents tested positive: two symptomatic (one died), eight asymptomatic on weekly enhanced surveillance; 2/275 caregivers tested positive: one symptomatic, one asymptomatic. At St Elizabeth’s (STE), 7/146 residents tested positive: four symptomatic (one died), one positive during hospital admission for symptoms unrelated to COVID-19, two asymptomatic on one-off testing of all 146 residents; 106/601 symptomatic caregivers were tested, 13 positive. In addition, during two cycles of systematically testing all asymptomatic carers, four tested positive. At The Meath (TM), 8/80 residents were symptomatic but none tested; 26/250 caregivers were tested, two positive. At Young Epilepsy (YE), 8/80 children were tested, all negative; 22/517 caregivers were tested, one positive.

Infection outbreaks in long-term care facilities for vulnerable people with epilepsy can be quickly contained, but only if asymptomatic individuals are identified through enhanced surveillance at resident and caregiver level. We observed a low rate of morbidity and mortality, which confirmed that preventative measures with isolation of suspected and confirmed COVID-19 residents can reduce resident-to-resident and resident-to-caregiver transmission. Children and young adults appear to have lower infection rates. Even in people with epilepsy and multiple co-morbidities, we observed a high percentage of asymptomatic people suggesting that epilepsy-related factors (anti-seizure medications and seizures) do not necessarily lead to poor outcomes.

Abbreviations: CCC, Crick COVID Consortium; CCE, Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy; COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; PPE, personal protective equipment; SARS-CoV-2, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2); STE, St Elizabeth’s Centre; SWGC, Sir William Gowers Centre; TM, The Meath; UCLH, University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; YE, Young Epilepsy

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2, Vulnerable people, Surveillance, Prevention, Care Models

1. Introduction

Novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) associated with the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus has quickly spread around the world [1]. A range of typical symptoms is associated with COVID-19, including fever, cough, and dyspnoea [2]. But these may be absent in older age, and in those with multi-morbidity [3]. Long-term care facilities are high-risk settings for poor outcomes from respiratory disease outbreaks, including COVID-19, due to greater prevalence of risk factors, like age and chronic health conditions [4], [5], [6].

During the first wave, only people admitted to hospital were tested for COVID-19 in the United Kingdom (UK). Official figures for the number of deaths in the community do not provide a comprehensive account of what has happened in care facilities [7]. These figures are likely to be underestimates due to the lack of testing.

Once COVID-19 is introduced into a care facility, it has the potential to spread rapidly and widely, causing serious adverse outcomes among those in care and those providing it [8], [9], [10]. Asymptomatic transmission of SARS-CoV-2 is considered the Achilles’ heel for society fighting the COVID-19 pandemic [11].

Here, we report the effect of early preventative measures and enhanced surveillance in a long-term care facility for people with epilepsy and multiple co-morbidities, and compare infection rates and outcomes with three other such facilities, which all adopted similar preventative measures, including attempts at shielding vulnerable and isolating symptomatic people, but did not have access to enhanced surveillance, and only very limited access to testing even symptomatic people.

2. Material and methods

This work was registered and independently approved by the Clinical Audit and Quality Improvement Subcommittee (Queen Square Division, UCLH University College London Hospitals Trust) as a service evaluation. This approval waives the need for approval by an ethics committee, in accordance with UK legislation and NHS operating procedures.

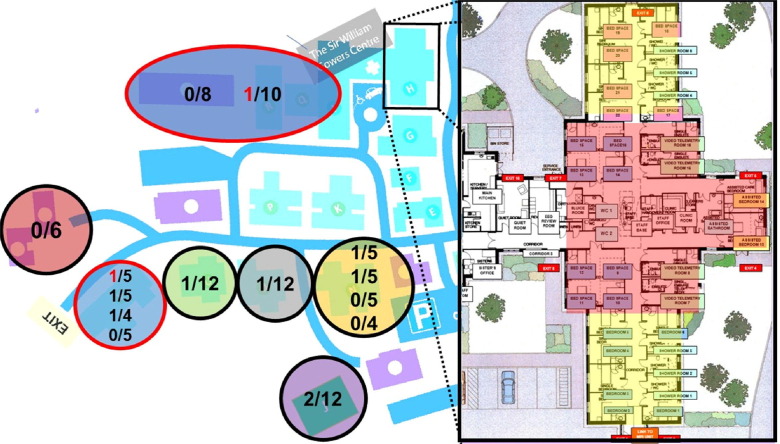

The Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE), north-west of London, is a long-term care facility for adults with severe epilepsy and other co-morbidities. It currently houses 98 people (66 males) aged between 23 and 91 (median age: 49 years), who live in seven units of 1–4 self-contained flats, each housing 5–12 people, looked after by 275 caregivers during the observation period. University College London Hospitals (UCLH) provides secondary and tertiary care to people living at the center, which also houses a UCLH elective unit for multidisciplinary assessment and treatment of adults with complex epilepsies (Sir William Gower Centre, SWGC) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE) map, with enlarged illustration of the repurposed COVID-19 care unit. CCE houses 98 people who live in seven units of 1–4 self-contained flats. Outbreaks were observed in six of the seven units (represented as circles in different colors), with two of the ten positive individuals that developed symptoms of COVID-19 (red numbers in red circles). Enlarged on the right of picture, Sir William Gowers Centre (SWGC), the repurposed COVID-19 care unit, with six single rooms and eight beds ward repurposed for individuals who tested positive (red area), and twelve beds for suspected residents who could not be isolated in their care homes (yellow).

St Elizabeth’s (STE), north-east of London, is a long-term care facility for 38 children and 108 adults with severe epilepsy and other co-morbidities. The adult residential facility consists of 11 units for 5–10 people, housing currently a total of 88 people (31 males), aged between 19 and 80 (median age: 42 years). There is also on-site a special needs school (38 individuals) and a further education college for 20 boarders (median age: 18 years; age-range: 12–23; 40 males). In total, 146 individuals were looked after by 601 caregivers during the observation period. UCLH provides tertiary care to 87/108 adults, and Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) to 12/38 children, living at the center.

The Meath (TM), south-west of London, is a long-term care facility for 80 adults (median age 39 years, range: 23–79; 28 males) with epilepsy and additional learning and other disabilities, looked after by 250 caregivers. Residents live in nine residential units each housing between 3 and 13 people. UCLH provides tertiary care for 12/80 individuals.

Young Epilepsy (YE), south of London, supports children and young adults with epilepsy and other co-morbidities. On this site, there is a school and a further education college, which continued to support some day-students, who were educated separately from boarders. The center operates seven separate children’s residential homes and a further 12 for young adults. Before COVID-19 they housed 111 students. Some families, however, shielded their children at home, and during the identified period the centre supported 80 children and young adults (median age 20, range 8–25 years, 53 males), looked after by 517 caregivers.

In response to COVID-19, different sets of measures were implemented on a short timescale (starting in mid-March) to keep those in the facilities as safe as possible, given limited available resources. The measures fell into the categories of prevention and surveillance (Table 1 ), and intervention.

Table 1.

List of prevention and surveillance measures adopted in the four care facilities starting on 23rd March 2020.

| Prevention | ||

|---|---|---|

| Vulnerable people living in the facility-related | Staff-related | General measures |

| Houses/Bungalows treated as “family units” with free movement within that space (all centers), but encouragement of elderly individuals to spend most of the time in their rooms, in particular for meals (CCE) | “Staff rostering” with designation and isolation of flats within each care unit as stand-alone, with contacts between staff or individuals from different units reduced (all centers) |

Caregivers allocated to one individual for whole duration of shift, minimization of contact, with multiple tasks to be performed during same contact, e.g. dispensing medication and checking temperature (CCE) |

| Banning of family members from site, provision of laptops to maintain on-line contacts (CCE, STE, TM) | No external visitors (all centers) | Minimization of numbers of staff down to safe levels, with remote working where feasible, e.g. for administrative staff (all centers) |

| Restriction of family visits (YE) | Only permanent staff working, no temporary agency staff, minimization of one to one care (TM) | |

| Closure of on-site communal areas (recreation hall, social, therapy and art centers) with cessation of group activities, but maintaining activities within the houses (all centers) | PPE for all caregivers and other essential staff (e.g. cleaners) when entering all units (CCE) | Social distancing for all activities as far as possible: staff required to keep 2 m distance with other team members, except in special circumstances, e.g. an individual requiring support from more than one caregiver (all centers) |

| Non-maintained special school and college continued activities but with reduced numbers of students (STE, YE) | PPE in use for personal care and administering emergency medications, and in isolation units at all times (STE, TM, YE) | Educational activities under-taken in separate areas of school and college for residential and day students (STE, YE) |

| Staff canteen open with appropriate social distancing measures (YE) | ||

| Maintenance of activities with regular outdoor activities (closed to external visitors), e.g. walks in the gardens, listening to or playing music outside (all centers) | Implementation of enhanced hygiene measures: regular cleansing of frequently touched surfaces, especially door handles (all centers) | To wear aprons and gloves for close (<2 m) contact with vulnerable individuals, with regular hand hygiene before and after, eye protection where there is risk of contamination from respiratory droplets or from splashing of secretions (CCE) |

| Surveillance | |

| Regular monitoring of body temperature (two/three times daily) of all those in care (at YE from mid-April). Temperature >37.8 °C notified to the nursing and medical team for closer observation and escalation of isolation (see Fig. 1 for CCE) and treatment (all centers) | Regular monitoring of temperature of all caregivers and health care professionals at the start of each shift. No caregivers allowed to work if their temperature exceeded 37.5 °C or if reported a new onset cough. Caregivers who developed symptoms during their shift immediately sent home to self-isolate for 14 days after symptom onset in line with Public Health England (PHE) guidance (all centers) |

| All other students living in the same home were also immediately isolated in the house, for 14 days or until negative swab result received (YE) | Where staff lived in the communal staff accommodation on site, they were temporarily moved to an identified single unit bungalow for their period of isolation/awaiting test results. (YE) |

| From April, symptomatic caregivers and family members tested (STE, YE) | |

Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE), St. Elisabeth (STE), The Meath (TM), and Young Epilepsy (YE).

2.1. Policy in the facilities

At CCE, a program of systematic action was implemented for isolation and on-site testing for COVID-19 suspected residents. Individuals were suspected to have COVID-19 if they had a temperature >37.8 °C, or a temperature rise of 1.5 °C above their long-term average, and/or new persistent cough or shortness of breath. SWGC was repurposed as an isolation facility. Any individual with suspected COVID-19 was admitted to SWGC (Fig. 1, yellow area). Samples were obtained by nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swabs and tested at the Crick COVID-19 Consortium (CCC) by PCR for SARS-CoV-2 [12]. While waiting for the test results (up to 48 h), individuals were cared for by dedicated and familiar caregivers in long shifts (i.e. 12 h) to reduce staff contacts. Staff employed personal protective equipment (PPE) and measures recommended for caring for confirmed COVID-19 residents [13], [14]. Residents testing positive were transferred to a separate section of SWGC (Fig. 1, red area) for provision of the usual care and management, with additional vital signs monitoring using NEWS [15]. If the result of the first testing in a symptomatic resident was negative, a second test was performed after 24–48 h. If the second testing was negative, other causes for raised temperature or other symptoms were re-considered (unless already indicated). De-isolation of negative residents took place only after 48 h following the resolution of the symptoms. After three weeks of intensive shielding and pragmatic surveillance of all people living in the facility, a further management step became available. This consisted of repeat enhanced surveillance of the remaining 97 of those in care, for early identification of positive residents in the asymptomatic phase [16]. Weekly rounds of enhanced surveillance testing of all those in care have been undertaken since 17 April 2020. Naso- and oropharyngeal swabs were collected and tested as above [12]. Results were usually available within 12–48 h and prompted isolation of identified positive asymptomatic residents in SWGC as described above (Fig. 1, red area). Tracing and testing of caregivers who had been in contact with those who had tested positive but were asymptomatic, was started within 12 h of the original positive result. As a further preventative step, routine surveillance of all asymptomatic caregivers working on-site was commenced on 30 April 2020.

At STE, TM and YE, early preventative measures were implemented to different degrees, but no on-site testing was available initially, with individuals only tested when admitted to hospital. Individuals were isolated within their rooms whilst presenting with COVID-19 like-symptoms, and/or transferred to dedicated units upon return from hospital, if the diagnosis was confirmed. Testing for caregivers with symptoms became available at testing stations from mid-April 2020, and on-site testing for symptomatic individuals since early May. At STE, all 146 asymptomatic individuals were tested between 29 May and 05 June, and again once since then, with weekly testing of a random sample of 50 people, either residents or staff.

2.2. Data availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting our findings are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request from bona-fide researchers.

3. Results

We report the outcomes in 2047 people living and working in four different long-term care facilities, home for 404 residents with an age range of 8–91 years.

3.1. Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy

3.1.1. Testing of residents with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19

Detailed demographic data for CCE are provided in Table 2 .

Table 2.

Summary of demographic and clinical details of residents living at Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE).

| All (n = 98) |

SARS-CoV-2 positive (n = 10) | SARS-CoV-2 negative (n = 88) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender n, % | 66 (67%) | 9 (90%) | 57 (65%) |

| Age in years, mean (range) | 49 (23–91) | 49 (33–69) | 48 (23–91) |

| BAME | 5 (5%) | 2 (20%) | 3 (3%) |

| Fever (>37.8) and/or respiratory symptoms n, % | 10 (10%) | 2 (20%) | 8 (9%) |

| Asymptomatic | 88 (90%) | 8 (80%) | 80 (91%) |

| Clinical frailty scale (1–9) mean (range) | 5.88 (3–8) |

5.3 (3–8) |

5.9 (3–8) |

| Cardiac co-morbidity | 15 (15%) | 1 (10%) | 14 (16%) |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 21 (21%) | 2 (20%) | 19 (22%) |

| Immunosuppression | 6 (6%) | 0 | 6 (7%) |

| Death | 1 (1%) | 1 | 0 |

BAME – Black, Asian and Minority Ethnic.

By 10 April 2020, two COVID-19 symptomatic residents were identified amongst the 98 individuals (2%) (Table 3 , Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Individual summaries of symptomatic residents tested positive at Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE) and St. Elizabeth’s (STE).

| Case | Age (decade) |

Unit | Intellectual disability* | Clinical Frailty Scale (1–9) |

Co-morbidities | Symptom onset (SO) Test results: dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1-1 | 60s | CCE 1 A |

moderate | 8 | obesity hypertension |

SO: 2 April positive: 3 April deceased 8 April |

| #1-2 | 50s | CCE 2 A |

moderate | 6 | hypertension | SO: 7 April positive: 10,17,24,28 April 4, 11 May negative: weekly, from 18 May to 8 September |

| #2-1 | 10s | STE 8 |

severe | 7 | obesity | SO: 5 March negative: 6 March positive: 23 March deceased 2nd April |

| #2-2 | 50s | STE 8 |

moderate | 7 | none | SO: 9 April positive: 17 April |

| #2-3 | 50s | STE 4 |

severe | 5 | obesity | SO: 22 April positive: 1 May |

| #2-4 | 20s | STE college |

severe | 7 | none | SO: 28 May positive: 29 May negative: 3 June |

The degree of intellectual disability was obtained by reviewing the clinical notes

The first (#1-1) tested positive on 03 April and was an individual in their 60s, living in a large nursing home consisting of two units with 9–10 people each. This person had severe epilepsy and multiple co-morbidities, including dysphagia with percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) in situ. They became symptomatic on the evening of 02 April, with vomiting and subsequently pyrexia possibly related to aspiration, rapid and severe clinical deterioration with reduced oxygen saturation at ∼70%, persistent high temperature not responsive to paracetamol, reduced conscious level (Glasgow Coma Scale <5). Transfer to hospital was promptly arranged and the person tested positive on 03 April; following further deterioration, death occurred six days after symptom onset.

The second (#1-2) was an individual in their 60s, with a genetic epilepsy and co-morbidities who lived in a large unit of 19 people with four self-contained flats each housing 4–5 people. On 09 April, they became pyrexial (38.7 °C) and were promptly isolated in a single room in SWGC, tested and confirmed positive. They remained clinically stable until day 3, when oxygen saturation dropped to ∼85% leading to a transfer to our linked hospital facility (UCLH), given the risk of further deterioration. They tested positive again on days 7, 14 and 18, but remained clinically asymptomatic following admission, without pyrexia, and discharged back to CCE on day 40, after testing negative on two consecutive occasions.

Further details for these symptomatic individuals are provided in Table 3.

As of 6 September, ten other individuals were promptly isolated due to the development of temperature above 37.8 °C, with or without respiratory symptoms: all have repeatedly (minimum twice) tested negative and were discharged back to their residences and de-isolated 48 h after symptom resolution.

3.1.2. Testing of asymptomatic residents

On 17 April 2020, CCE started regular weekly surveillance of residents. Of the remaining 96 people, seven were not tested in the first round as five declined and two had temporarily moved out. Of the 89 tested, four were positive (4.5%) and were immediately isolated.

On 22 April, in the second surveillance round, 95/96 were tested as only one declined Three who previously tested negative were now positive but remained asymptomatic throughout.

On 27 April, in the third surveillance round, all 96 people tested negative, including one of the asymptomatic individuals who had twice tested positive previously.

On 09 June, in the 9th surveillance round, an 8th asymptomatic individual tested positive. Re-testing on 11 and 13 June returned negative results (see Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Individual summaries of asymptomatic residents tested positive at Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE) and St. Elizabeth’s (STE).

| Case | Age (decade) | Unit | Intellectual disability | Clinical Frailty Scale (1–9) |

Co-morbidities | Test results: dates |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #1-3 | 40s | CCE 2B | severe | 5 | none | positive: 17 April negative: from 22April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-4 | 30s | CCE 2C | severe | 5 | none | positive: 17 April negative: from 22, 24, 28 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-5 | 60s | CCE 3 | mild | 6 | hypertension | positive: 17 April negative: from 22, 24, 28 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-6 | 40s | CCE 4 | mild | 4 | none | positive: 19 April negative: from 24 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-7 | 40s | CCE 5A | moderate | 6 | none | positive: 22, 27 April negative: from 17 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-8 | 50s | CCE 5B | severe | 5 | none | positive: 22 April negative: from 17 April to 8 September, weekly, |

| #1-9 | 50s | CCE 6 | moderate | 5 | chronic respiratory | positive: 22 April negative: from 17 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #1-10 | 40s | CCE 4 | mild | 3 | none | positive: 9 June negative: from 22 April to 8 September, weekly |

| #2-5 | 40s | STE 6 | severe | 3 | none | positive: 7 May negative: 13 May |

| #2-6 | 10s | STE college | severe | 7 | chronic respiratory | positive: 5 June |

| #2-7 | 30s | STE 11 |

severe | 7 | nephrolythiasis | positive: 18 September negative: 22 September |

No further positive individuals were identified in 13 further surveillance rounds, up to 6 September.

3.1.3. Contact tracing and surveillance of care staff

Following confirmation of a positive result, testing of caregivers who had been in contact over the previous two weeks with positive individuals was performed within three days. A total of 150 caregivers accepted testing; only one symptomatic caregiver tested positive on 11 April, before enhanced surveillance of residents started on 17 April. From 30 April onwards, weekly surveillance of all asymptomatic 275 caregivers has been implemented: only one tested positive, on 04 June, with two negative re-tests on 08 and 10 June. The symptomatic caregiver positive on 11 April fully recovered and tested negative on 17 April and repeatedly until 19 June, when although completely asymptomatic tested positive again. This individual has repeatedly tested negative since. On 15 May, this caregiver had positive antibody titres, suggestive of a previous infection with SARS-CoV-2. When antibodies were re-tested on 22 June, titres for Nucleocapsid, receptor binding domain and full trimeric spike were raised, suggestive of an acute re-infection.

3.2. St Elizabeth’s

3.2.1. Testing of residents with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19

By 07 May 2020, three symptomatic individuals were identified amongst the 146 people living on-site (2%) (Table 3).

The first (#2-1) was a young adult with epilepsy following encephalitis aged 2, dysphagia with PEG in situ and severe intellectual disability who lived in a unit with eight other people. They were admitted to hospital on 05 March, with aspiration pneumonia following an episode of vomiting, tested then negative, and was discharged 09 March. Two weeks later, on 23 March, he presented with a new cough and pyrexia, was transferred back to the hospital the same day, and then tested positive. Ventilation became necessary. Death occurred 11 days after symptom onset.

The second (#2-2) was an individual in their 50s, with a genetic epilepsy who lived in the same unit as #3. On 09 April, this individual became symptomatic with fever, lethargy and cough for 1 week, after which they rapidly deteriorated with respiration rate >32 per minute and oxygen saturation <88%. They were promptly isolated and confirmed positive on 20 April, and remained in isolation until 05 May. One caregiver at the same unit showed symptoms on the same day as #2-2, and tested positive. Another caregiver was asymptomatic and tested positive on 08 May.

The third (#2-3) was an individual in their late 50s, with refractory epilepsy of unknown cause and moderate intellectual disability, who lived in a different unit to #2-1 and #2-2. The individual became symptomatic on 22 April, with mild fever and cough, but would not consent to isolation in room and so was moved to an unused area of another building. Supplemental oxygen was used for the first few days as his oxygen saturation fell <90%, but, overall, symptoms remained mild. A positive result for COVID-19 testing was received on 01 May. The fourth (#2-4) was an individual in their early 20s, with a genetic epilepsy who was a boarder in college. The individual became symptomatic on 28 May, with mild fever. They were admitted to A&E with oxygen saturation <88% on 30 May, discharged that evening and transferred to isolation unit. A positive test result was received on 30 May; a re-swab on 03 June returned a negative result. One caregiver working in the college, but also in a hospital, was symptomatic and tested positive on 30 May.

Further details for these symptomatic individuals are provided in Table 3.

Prior to 29 May, eight further resident were promptly isolated as they become symptomatic but only six were tested (testing was not available for the other two), and all were negative. All eight individuals were discharged back to their residences and de-isolated 24–48 h after symptom resolution.

3.2.2. Testing of asymptomatic residents

A fifth (#2-5) individual tested positive on 07 May, during one of their frequent hospital admissions for recurrent urinary tract infections, but was considered asymptomatic for COVID-19 as malaise was attributed to the other health conditions, and was tested negative prior to discharge on 13 May. This individual in their late 40s lives in a different unit than the three symptomatic individuals tested positive. One caregiver from the same unit became symptomatic on 11 April and another on 08 May: both tested positive.

Between 29 May and 05 June 2020, all asymptomatic individuals living on-site were tested. Of the 146 tested, one young adult living as a boarder attending college was found to be positive. This individual attended class together with the symptomatic boarder #2-4. One caregiver working in the college also become symptomatic a few days earlier and tested positive on 30 May. Since early June, a random sample of 50 residents or caregivers were tested weekly, so that all have been tested twice since June. One further asymptomatic individual tested positive and isolated.

3.2.3. Contact tracing and surveillance of care staff

From 06 April onwards, testing was available for symptomatic caregivers and those needing to self-isolate for 14 days if a household member had symptoms. Contact tracing was implemented from 02 May, with testing of all caregivers who had contact with positive individuals. Of the 601 workforce, 105 were tested once, 13 symptomatic caregivers tested positive. Enhanced surveillance was implemented at the end of May, with 50 random samples from caregivers, so that all staff members have tested twice. An additional four asymptomatic caregivers were found positive after introducing contact tracing and enhanced surveillance.

3.3. The Meath

3.3.1. Testing of residents with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19

By 6 September 2020, eight symptomatic residents were identified amongst the 80 people living on-site (10%). There was no access to viral testing, but they were promptly isolated for at least 48 hours after complete resolution of the symptoms

3.3.2. Testing of asymptomatic residents

There was no routine asymptomatic screening.

3.3.3. Contact tracing and surveillance of care staff

Up until 05 June, 26 of 250 staff were symptomatic, and have been tested, with two positive results.

3.4. Young Epilepsy

3.4.1. Testing of residents with symptoms suggestive of COVID-19

By 6 September 2020, eight symptomatic individuals were identified amongst the 80 people living on-site (10%). All tested negative; seven were tested once, one individual twice for persistent COVID-like symptoms.

3.4.2. Testing of asymptomatic residents

There was no routine asymptomatic screening at TM or YE.

3.4.3. Contact tracing and surveillance of care staff

There was no systematic testing, but at least 22 of 517 student-facing caregivers are known to have attended communal testing centers throughout this period. Only one agency nurse who had worked also at other facilities was severely ill and tested positive.

4. Discussion

We report confirmed COVID-19 outbreaks in two out of four care facilities for people with epilepsy and additional co-morbidities. Less than 3% of individuals living in the two facilities showed COVID-19 related symptoms and tested positive. Enhanced surveillance, available at CCE, showed a high rate of asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals (8/10 testing positive; 80%). Our case fatality rate was high (CCE: 50%, or 10% corrected for asymptomatic; STE: 25%), but the total number of deaths, one at each of the two centers, was in line with the average death rate over similar observation periods over the last five years at each facility: there was no excess of deaths.

Our observations at CCE of a relatively low (10%) infection but high (80%) asymptomatic rates are similar to the report of initially heathy populations (3711 passengers on Diamond Princess cruise ship) with a fifth testing positive, and of those about half being asymptomatic [17]. Our higher asymptomatic rates might be explained by the difficulties of detecting mild or no symptoms in people with severe intellectual disability. Our rates are, however, dissimilar from those reported in another, similarly-sized long-term care facility with access to testing asymptomatic individuals: among 76 individuals, 48 (63%) tested positive initially with 27 (56%) asymptomatic at time of testing, but only three remained asymptomatic (6%) [4]. Their case fatality rate was also higher (26%), possibly due to a difference in population characteristics (average age of those tested positive: 79 years versus 52 years at CCE).

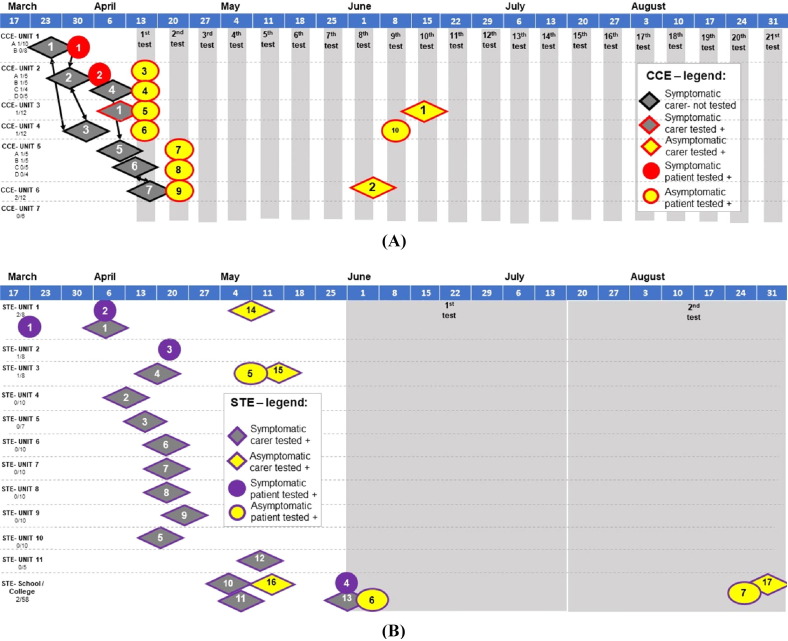

We succeeded in containing a widespread outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 in six of seven care units at CCE with a low rate of spread, i.e. only one infected individual per individual care unit, with no established resident-to-caregiver transmission. Only one caregiver tested positive during immediate contact tracing and none of the 275 caregivers during the weekly surveillance phase. A second outbreak in two care-units was detected early through enhanced surveillance, with one asymptomatic caregiver and one asymptomatic individual living in the facility who both tested positive, without further positive test results on immediate contact tracing and weekly surveillance since. In contrast, at STE, initially without enhanced surveillance, 13 symptomatic caregivers tested positive out of 106 since testing of symptomatic caregivers became available at STE on 6 April. An additional four asymptomatic caregivers tested positive during contact tracing and enahced surveillance. Infections of individuals living in the facilities and amongst caregivers were widespread across almost all care units at CCE (6/7) and STE (11/11). Whilst the spread of infections was contained at CCE within 3 weeks, positive test results at STE were seen throughout the 26 weeks’ observation period (see Fig. 2 ). While symptom severity was similar between the two sites, we assume that the difference in numbers of infected staff (3/275 at CCE vs 17/601 at STE, P < 0.05) is likely due to enhanced surveillance available at CCE. There was no access to systematic testing at TM and YE.

Fig. 2.

Timeline across centres Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy (CCE) (A) and St. Elizabeth’s (STE) (B). This includes all symptomatic residents tested positive (red circle CCE 1–2; purple circle STE 1–4), asymptomatic tested positive (red outlined yellow circle CCE 3–10; purple outlined yellow circle STE 5–6), symptomatic caregiver (red outlined gray diamond CCE 1) who was asymptomatic when tested positive again during surveillance (red outlined yellow diamond CCE 1) after eight negative tests; selected symptomatic staff at CCE (black outlined gray diamond CCE 2–7, self-isolating but not tested); symptomatic caregivers at STE tested positive (purple outlined gray diamond STE 1–13), and asymptomtic staff tested positive (red outlined yellow diamond CCE 1–2; purple outlined yellow diamond STE 14–16). Staff are presented in the unit where they regularly worked, arrows connect staff who are also household contacts at CCE. Timings represent date of symptom onset (symptomatic individuals), or date of self-isolation from work (staff members, who were not PCR tested), gray columns represent date of enhanced surveillance.

Care facilities are highly vulnerable to COVID-19 outbreaks [9], [10], [18], and it is crucial to identify effective strategies to prevent infection and to reduce impact. The approach reported here focused on two main strategies: (1) early on-site enhancement of preventative and infection control measures, (2) early identification and isolation of symptomatic individuals, with enhanced surveillance and isolation of asymptomatic people living and working at CCE as an additional measure. All centers were able to implement isolation of suspected and confirmed residents in empty or re-purposed units (see Fig. 1 for CCE), avoiding hospital admission and allowing continuity of care by staff acquainted with the individuals. The use of PPE was enforced early during the pandemic, but to different degrees (see Table 1), mainly depending on open market sourcing rather than centralized procurement [19]. Similar early implementation of these measures in a care facility in the US has been reported to be effective in minimizing viral spread [20]. Whilst this is reassuring, suggesting that PPE and good hand hygiene can effectively prevent transmission when in contact with confirmed positive individuals, caregivers themselves must have been pre- or asymptomatic earlier and so, unknowingly, infected colleagues and individuals under their care, as happened at CCE. The initial spread of infection across the sites, very likely caused by healthcare workers from different care units sharing accommodation (see Fig. 2), questions the initial advice to healthcare workers of continuing to go to work despite household members self-isolating.

Individuals in all centers had different degrees of intellectual disability, such that it was not possible to assess reliably for the presence of non-respiratory symptoms, which have been described involving various organs [3], [21]. For example, acute–onset anosmia may manifest either early in the disease process or in people with mild or no constitutional symptoms [22]. Similarly, due to limited compliance, the false negative rate of testing can be expected to be higher in this population than the already quoted 20–30% [23]. Thus, enhanced surveillance through repeat testing of all ‘asymptomatic’ individuals is vital for case ascertainment in such settings, to identify covert transmitters and individuals at risk of rapid deterioration [24], [25]: three of the seven asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive individuals at CCE in round two tested negative during the first round of surveillance, and the first positive individual #2-1 from STE was initially tested negative on admission to hospital, but not when discharged. According to UK public health guidance, a negative test was not required prior to discharge from hospital back to a care facility [26]. Such discharges may contribute to the risk of infection spreading within care facilities. We also describe a case of re-infection among caregivers, a phenomenon which has been recently reported in the literature, although the mechanisms of immunity, or its loss, underlying re-infection have not been yet established [27].

Not surprisingly, contact tracing at CCE proved difficult, not only for asymptomatic individuals testing positive without data on when the infection might have occurred, but also due to caregivers sharing accommodation (contacts of contacts, see Fig. 2), large numbers of agency workers, in particular in CCE-Unit 2, and delay in obtaining test results (up to 5 days after testing). Testing of symptomatic caregivers at STE (13 positive out of 105 tested) and TM (2/26) returned similar numbers of positive tests in symptomatic people compared to the general UK population (as of 13 September 2020: 368,504 people/19,293,329 tests), with the official numbers not accounting for multiple tests in hospitals for the same individual (two negative tests prior to discharge). Together with a low rate of infected individuals, this is re-assuring as it suggests that early implementation of preventative and infection control measures in all four long-term care facilities (see Table 1) can reduce the infection risk in high-risk environments [11], be it for vulnerable individuals living in long-term care facilities or their caregivers, to a level similar to that observed in the general population. We also show, however, that these measures alone, without identification of asymptomatic people through enhanced surveillance, do not contain the spread of infection.

Despite the frailty and multiple co-morbidities of our population, the impact to date of SARS-CoV-2 in all the facilities has been limited. Children and young adults appear to have lower infection rates, although access to testing, even of symptomatic individuals, was limited in this age group. Enhanced surveillance, as at CCE, is required to determine the true infection rate in the younger age groups. Three of the confirmed positive individuals at CCE/STE and one of the suspected individuals at YE have an underlying genetic condition frequently observed in people with severe epilepsy, with mutation in the SCN1A gene, which is known to be associated with fever sensitivity and elevated risk of early mortality [28] Host genetic predictors of outcome in SARS-CoV-2 infections are yet to be established [29]. SARS-CoV-2 RNA mutations and additional molecular mechanisms may explain variability in clinical presentation [30], [31].

5. Conclusions

We provide evidence of the need for enhanced surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 of asymptomatic people in high-risk environments. We recognize that CCE was fortunate to have extensive collaboration between basic science repurposed for high-throughput viral testing (the Francis Crick Institute), high-level virological and clinical input (from UCLH), and the ability to redeploy clinical academics (from UCL), to support dynamic and purposeful care teams. All centers benefit from close integration between health and social care with close reviews by epilepsy consultants from UCLH and/or GOSH. Such multidisciplinary input is not available to all care facilities, but the strategies outlined here may provide generally applicable guidance for other facilities facing similar challenges, in particular in preparation for a additional waves of infection. We hope that such integration between science, healthcare and social care can also generate a new model for the care of the most vulnerable in society in the future. We must learn that there are better ways to be a civil society, to ensure that those living in care facilities are not excluded from the expertise and interventions available for the wider population.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all people living at the Chalfont Centre for Epilepsy, St Elisabeth, The Meath and Young Epilepsy and their families. We are also grateful to all care staff working at the Chalfont Centre, St Elisabeth, The Meath and Young Epilepsy. We thank Professor David Goldblatt, Dr Louis Grandjean, and Dr Marina Johnson, for the support provided in arranging antibody testing for one of the caregivers, and interpretation of the results. This work was supported by Epilepsy Society, UK. It was undertaken at UCLH/UCL Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre and at Great Ormond Street Hospital Biomedical Research Centre. Research in both sites is supported by the UK Department of Health’s NIHR Biomedical Research Centres funding scheme. S Balestrini was supported by the Muir Maxwell Trust. Funding was also provided by MRC, European Union (Horizon 2020), and GSK. K Silvennoinen is supported by a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (WT104033AIA). C Swanton is Royal Society Napier Research Professor. Part of this work was carried out at the Francis Crick Institute, which receives core funding from Cancer Research UK (FC001169), the UK Medical Research Council (FC001169), and the Wellcome Trust (FC001169). He receives funding from the European Research Council (ERC) under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) Consolidator Grant (FP7-THESEUS-617844), European Commission ITN (FP7-PloidyNet 607722), an ERC Advanced Grant (PROTEUS) from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement No. 835297), and Chromavision from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (grant agreement 665233). JW Sander receives research support from the Dr. Marvin Weil Epilepsy Research Fund and the Christelijke Verenigingvoor de verpleging van Lijdersaan Epilepsie, The Netherlands.

Declarations of Interest

None of the authors report conflicts in relation to this work.

Contributor Information

Crick COVID Consortium (CCC):

Jim Aitken, Zoe Allen, Rachel Ambler, Karen Ambrose, Emma Ashton, Alida Avola, Samutheswari Balakrishnan, Caitlin Barns-Jenkins, Genevieve Barr, Sam Barrell, Souradeep Basu, Rupert Beale, Clare Beesley, Nisha Bhardwaj, Shahnaz Bibi, Ganka Bineva-Todd, Dhruva Biswas, Michael J. Blackman, Dominique Bonnet, Faye Bowker, Malgorzata Broncel, Claire Brooks, Michael D. Buck, Andrew Buckton, Timothy Budd, Alana Burrell, Louise Busby, Claudio Bussi, Simon Butterworth, Matthew Byott, Fiona Byrne, Richard Byrne, Simon Caidan, Joanna Campbell, Johnathan Canton, Ana Cardoso, Nick Carter, Luiz Carvalho, Raffaella Carzaniga, Natalie Chandler, Qu Chen, Peter Cherepanov, Laura Churchward, Graham Clark, Bobbi Clayton, Clementina Cobolli Gigli, Zena Collins, Sally Cottrell, Margaret Crawford, Laura Cubitt, Tom Cullup, Heledd Davies, Patrick Davis, Dara Davison, Vicky Dearing, Solene Debaisieux, Monica Diaz-Romero, Alison Dibbs, Jessica Diring, Paul C. Driscoll, Annalisa D'Avola, Christopher Earl, Amelia Edwards, Chris Ekin, Dimitrios Evangelopoulos, Rupert Faraway, Antony Fearns, Aaron Ferron, Efthymios Fidanis, Dan Fitz, James Fleming, Daniel Frampton, Bruno Frederico, Alessandra Gaiba, Anthony Gait, Steve Gamblin, Kathleen Gärtner, Liam Gaul, Helen M. Golding, Jacki Goldman, Robert Goldstone, Belen Gomez Dominguez, Hui Gong, Paul R. Grant, Maria Greco, Mariana Grobler, Anabel Guedan, Maximiliano G. Gutierrez, Fiona Hackett, Ross Hall, Steinar Halldorsson, Suzanne Harris, Sugera Hashim, Emine Hatipoglu, Lyn Healy, Judith Heaney, Susanne Herbst, Graeme Hewitt, Theresa Higgins, Steve Hindmarsh, Rajnika Hirani, Joshua Hope, Elizabeth Horton, Beth Hoskins, Michael Howell, Louise Howitt, Jacqueline Hoyle, Mint R. Htun, Michael Hubank, Hector Huerga Encabo, Deborah Hughes, Jane Hughes, Almaz Huseynova, Ming-Shih Hwang, Rachael Instrell, Deborah Jackson, Mariam Jamal-Hanjani, Lucy Jenkins, Ming Jiang, Mark Johnson, Leigh Jones, Nnennaya Kanu, George Kassiotis, Gavin Kelly, Louise Kiely, Anastacio King Spert Teixeira, Stuart Kirk, Svend Kjaer, Ellen Knuepfer, Nikita Komarov, Paul Kotzampaltiris, Konstantinos Kousis, Tammy Krylova, Ania Kucharska, Robyn Labrum, Catherine Lambe, Michelle Lappin, Stacey-Ann Lee, Andrew Levett, Lisa Levett, Marcel Levi, Hon Wing Liu, Sam Loughlin, Wei-Ting Lu, James I. MacRae, Akshay Madoo, Julie A. Marczak, Mimmi Martensson, Thomas Martinez, Bishara Marzook, John Matthews, Joachim M. Matz, Samuel McCall, Laura E. McCoy, Fiona McKay, Edel C. McNamara, Carlos M. Minutti, Gita Mistry, Miriam Molina-Arcas, Beatriz Montaner, Kylie Montgomery, Catherine Moore, David Moore, Anastasia Moraiti, Lucia Moreira-Teixeira, Joyita Mukherjee, Cristina Naceur-Lombardelli, Aileen Nelson, Jerome Nicod, Luke Nightingale, Stephanie Nofal, Paul Nurse, Savita Nutan, Caroline Oedekoven, Anne O'Garra, Jean D. O'Leary, Jessica Olsen, Olga O'Neill, Nicola O'Reilly, Paula Ordonez Suarez, Neil Osborne, Amar Pabari, Aleksandra Pajak, Venizelos Papayannopoulos, Stavroula M Paraskevopoulou, Namita Patel, Yogen Patel, Oana Paun, Nigel Peat, Laura Peces-Barba Castano, Ana Perez Caballero, Jimena Perez-Lloret, Magali S. Perrault, Abigail Perrin, Roy Poh, Enzo Z. Poirier, James M. Polke, Marc Pollitt, Lucia Prieto-Godino, Alize Proust, Clinda Puvirajasinghe, Christophe Queval, Vijaya Ramachandran, Abhinay Ramaprasad, Peter Ratcliffe, Laura Reed, Caetano Reis e Sousa, Kayleigh Richardson, Sophie Ridewood, Fiona Roberts, Rowenna Roberts, Angela Rodgers, Pablo Romero Clavijo, Annachiara Rosa, Alice Rossi, Chloe Roustan, Andrew Rowan, Erik Sahai, Aaron Sait, Katarzyna Sala, Emilie Sanchez, Theo Sanderson, Pierre Santucci, Fatima Sardar, Adam Sateriale, Jill A. Saunders, Chelsea Sawyer, Anja Schlott, Edina Schweighoffer, Sandra Segura-Bayona, Rajvee Shah Punatar, Maryam Shahmanesh, Joe Shaw, Mariana Silva Dos Santos, Margaux Silvestre, Matthew Singer, Daniel M. Snell, Ok-Ryul Song, Moira J. Spyer, Louisa Steel, Amy Strange, Adrienne E. Sullivan, Michele S.Y. Tan, Zoe H. Tautz-Davis, Effie Taylor, Gunes Taylor, Harriet B. Taylor, Alison Taylor-Beadling, Fernanda Teixeira Subtil, Berta Terré Torras, Patrick Toolan-Kerr, Francesca Torelli, Tea Toteva, Moritz Treeck, Hadija Trojer, Ming-Han C. Tsai, James M.A. Turner, Melanie Turner, Jernej Ule, Rachel Ulferts, Sharon P. Vanloo, Selvaraju Veeriah, Subramanian Venkatesan, Karen Vousden, Andreas Wack, Claire Walder, Philip A. Walker, Yiran Wang, Sophia Ward, Catharina Wenman, Luke Williams, Matthew J. Williams, Wai Keong Wong, Joshua Wright, Mary Wu, Lauren Wynne, Zheng Xiang, Melvyn Yap, Julian A. Zagalak, Davide Zecchin, and Rachel Zillwood

ChAlfont keepS vulnerAble People safe (ASAP) Consortium::

Santhakumari Carthiyaniamma, Jane DeTisi, Julie Dick, Andrea Hill, Karin Kipper, Birinder Kullar, Sarah Norris, Fergus Rugg-Gunn, Rebecca Salvatierra, Gabriel Shaya, Astrid Sloan, Priyanka Singh, James Varley, and Ben Whatley

References

- 1.https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 2.https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 3.https://www.bgs.org.uk/blog/atypical-COVID-19-presentations-in-older-people-–-the-need-for-continued-vigilance [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 4.Arons M.M., Hatfield K.M., Reddy S.C., Kimball A., James A., Jacobs J.R., et al. Presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections and transmission in a skilled nursing facility. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2081–2090. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2008457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.https://www.epicentro.iss.it/coronavirus/bollettino/Report-COVID-2019_20_marzo_eng.pdf. [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 6.Hand J., Rose E.B., Salinas A., Lu X., Sakthivel S.K., Schneider E., Watson J.T. Severe respiratory illness outbreak associated with human coronavirus NL63 in a long-term care facility. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018;24:1964–1966. doi: 10.3201/eid2410.180862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-52341403 [accessed 14 September 2020].

- 8.McMichael T.M., Currie D.W., Clark S., Pogosjans S., Kay M., Schwartz N.G., et al. Epidemiology of COVID-19 in a long-term care facility in King County, Washington. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2005–2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2005412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iacobucci G. COVID-19: care home deaths in England and Wales double in four weeks. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iacobucci G. COVID-19: UK government is urged to publish daily care home deaths as it promises more testing. BMJ. 2020;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gandhi M., Yokoe D.S., Havlir D.V. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles’ heel of current strategies to control COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2158–2160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe2009758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.04.19.20071373v1. [accessed 14 September 2020].

- 13.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-infection-prevention-and-control [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 14.https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/COVID-19-personal-protective-equipment-use-for-aerosol-generating-procedures [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 15.https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/projects/outputs/national-early-warning-score-news-2 [accessed 19 April 2020].

- 16.Nishiura H., Kobayashi T., Suzuki A., Suzuki A., Jung S.M., Hayashi K., et al. Estimation of the asymptomatic ratio of novel coronavirus infections (COVID-19) Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:154–155. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moriarty L.F., Plucinski M.M., Marston B.J., Kurbatova E.V., Knust B., Murray E.L., et al. Public health responses to COVID-19 outbreaks on Cruise Ships — Worldwide, February–March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:347–352. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6912e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Porzio G., Peris F., Ravoni G., Colpani E., Cecchi M., Parretti G., et al. The COVID-19 epidemic is posing entirely new problems for home cancer care services. Recenti Prog Med. 2020;111:257–258. doi: 10.1701/3347.33189. [Article in Italian] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/880094/PHE_11651_ COVID-19_How_to_work_safely_in_care_homes.pdf [accessed 27 April 2020].

- 20.Roxby A.C., Greninger A.L., Hatfield K.M., Lynch J.B., Dellit T.H., James A., et al. Detection of SARS-CoV-2 among residents and staff members of an independent and assisted living community for older adults - Seattle, Washington, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:416–418. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6914e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/04/how-does-coronavirus-kill-clinicians-trace-ferocious-rampage-through-body-brain-toes [accessed 27 April 2020].

- 22.Xydakis M.S., Dehgani-Mobaraki P., Holbrook E.H., Geisthoff U.W., Bauer C., Hautefort C., et al. Smell and taste dysfunction in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30293-0. S1473-3099(20)30293-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green D.A., Zucker J., Westblade L.F., Whittier S., Rennert H., Velu P., et al. Clinical performance of SARS-CoV-2 molecular testing. J Clin Microbiol. 2020;58(8) doi: 10.1128/JCM.00995-20. e00995-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Meng H., Xiong R., He R., Lin W., Hao B., Zhang L., et al. CT imaging and clinical course of asymptomatic cases with COVID-19 pneumonia at admission in Wuhan, China. J Infect. 2020;81:e33–e39. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Considine J., Street M., Bucknall T., Rawson H., Hutchison A.F., Dunning T., et al. Characteristics and outcomes of emergency interhospital transfers from subacute to acute care for clinical deterioration. Int J Qual Health Care. 2019;31:117–124. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzy135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/879639/COVID-19-adult-social-care-action-plan.pdf [accessed 27 April 2020].

- 27.Parry J. Covid-19: Hong Kong scientists report first confirmed case of reinfection. BMJ. 2020;370 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dravet C., Bureau M., Oguni H., Fukuyama Y., Çokar O. In: Epileptic syndromes in infancy, childhood and adolescence. 4th ed. Roger J., Bureau M., Dravet C., Genton P., Tassinari C.A., Wolff P., editors. John Libbey Eurotext; Paris, France: 2005. Severe myoclonic epilepsy in infancy (Dravet syndrome) pp. 89–113. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanigawa Y, Rivas M. Initial review and analysis of COVID-19 host genetics and associated phenotypes. Preprints 2020, 2020030356. doi:10.20944/preprints202003.0356.v1.

- 30.https://blogs.sciencemag.org/pipeline/archives/2020/04/21/watching-for-mutations-in-the-coronavirus. [accessed 27 April 2020].

- 31.Masters P.S. The molecular biology of coronaviruses. Adv Virus Res. 2006;66:193–292. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(06)66005-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting our findings are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request from bona-fide researchers.