In 2015, globally over 236 million individuals aged ≥25 years had peripheral artery disease (PAD), a serious health condition with a high morbidity burden and mortality risk [1]. PAD shares several risk factors with chronic kidney disease (CKD), including smoking, diabetes, hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia. Moreover, patients with established PAD are at increased risk of other vascular events including CKD, ischaemic heart disease, heart failure and stroke [2]. Correction of established cardiovascular risk factors may reduce the risk of PAD and its complications, but additional therapeutic targets need to be identified in order to improve outcomes in this high-risk population. Among these targets are non-traditional cardiovascular risk factors, which can be targeted with pharmacological or non-pharmacological interventions.

Several mechanisms may be involved in the aetiology of PAD. Intimal atherosclerosis and plaque formation, driven by traditional cardiovascular risk factors, are common and play a prominent role in PAD development. In addition, calcification of the tunica media, which is highly prevalent in patients with advanced CKD and diabetes, can promote PAD [3]. Over the past years, several studies have highlighted a role for magnesium as a direct modulator of vascular (media) calcification, among others through effects on pro-osteogenic signalling and hydroxyapatite formation (Figure 1). Interestingly, magnesium can also influence atherosclerosis, among others through improving endothelial function by reducing inflammation and altering lipid metabolism [4, 5]. Epidemiological studies have shown inverse correlations of serum magnesium levels and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CKD patients [6].

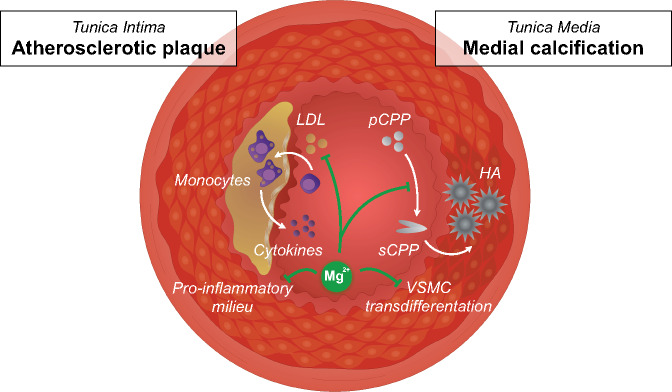

FIGURE 1.

Schematic overview of potential mechanisms by which magnesium (Mg2+) protects against PAD. On one hand, Mg2+ may reduce medial calcification (right side), by inhibiting the conversion of primary CPPs to secondary CPPs, promoting hydroxyapatite crystal deposition in the tunica media. In addition, Mg2+ may inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell transdifferentiation in the media layer. On the other hand, Mg2+ may also influence low-density lipoprotein cholesterol metabolism and reduce inflammation in the tunica intima, which may retard atherosclerotic plaque development (left side). HA, hydroxyapatite; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; pCPP, primary CPP; sCPP, secondary CPP; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cell.

Recently, two studies addressed whether serum magnesium is associated with the risk of developing PAD in the general population [7, 8]. Both studies used data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) cohort, a large prospective study conducted in four US communities. Sun et al. [7] studied 13 826 ARIC participants aged 40–64 years, and found that a lower serum magnesium level was independently associated with an increased risk of developing PAD during a median follow-up of 24.4 years. Individuals in the lowest serum magnesium quintile (≤1.4 mEq/L) had a 30% higher risk of developing PAD, compared with those in the highest magnesium quintile (≥1.8 mEq/L, P < 0.001), after adjustment for several potential confounders. The shape of this association was nonlinear (J-shaped), with individuals in the lower range being at increased risk, while a higher magnesium level did not seem to provide additional protection compared with the group median. In patients with mild to moderate CKD, serum magnesium may be normal or low, the latter particularly due to treatment with proton-pump inhibitors, thiazide diuretics and other drugs [9].

In this issue of Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, Menez et al. [8] extended the initial results from the ARIC cohort by focusing on the interaction by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). In individuals with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (n = 11 606 of whom 436 developed PAD), there was a strong and consistent inverse association between serum magnesium and PAD risk. In contrast, this association was not present in participants with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2, who seemed to have a similar distribution of magnesium levels compared with individuals with an eGFR >60 mL/min/1.73 m2. It is, however, important to note that the analyses in the low eGFR group had considerably less statistical power, since this subgroup consisted of only 233 ARIC participants, 35 of whom developed PAD. In particular, the further adjusted Cox regression models that contained more than 10 covariates are prone to overfitting, potentially blunting the results. Unfortunately, results from crude or minimally adjusted analyses in this subgroup were not provided. Alternatively, using a higher eGFR cut-off (e.g. ≤70 mL/min/1.73 m2) may allow to increase the sample size to get a more robust impression of the association between serum magnesium and incident PAD in individuals with (mildly) impaired kidney function. Yet, the observation by Menez et al. might indicate that a low magnesium level is a less important risk factor for PAD in CKD patients. Possibly, other factors such as deregulated mineral metabolism (hyperparathyroidism tended to be associated with a higher PAD risk in patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2) or hyperphosphataemia may be more important risk factors than low magnesium levels in this population, especially in CKD Stage G5 where hypermagnesaemia develops frequently [10].

How can this observation be reconciled with emerging data that seem to position magnesium as an important factor in the prevention of vascular calcification in CKD? A substantial body of in vitro and in vivo studies has demonstrated that vascular calcification is significantly delayed under high magnesium conditions [6]. Multiple molecular mechanisms may contribute to the development of vascular calcification, including extracellular formation of calcium-containing particles and transdifferentiation of vascular smooth muscle cells in osteoblast-like cells [6, 11]. Magnesium has been proposed to interfere with this transdifferentiation process at several levels: (i) it may function as calcium channel antagonist and thereby reduces cellular calcium uptake; (ii) magnesium uptake via transient receptor potential melastatin type 7 channels may directly inhibit pro-osteogenic gene transcription; and (iii) magnesium activates the calcium-sensing receptor and thereby inhibits calcification [11]. However, recent data from our groups indicate that in particular the circulating calcium- and phosphate-containing particles may play an essential role. In CKD, high serum phosphate levels promote the formation of the so-called secondary calciprotein particles (CPPs). Secondary CPPs contain crystalline calcium–phosphate and are considered an important driver of CKD-associated vascular calcification. Recent in vitro studies indicated that magnesium can inhibit the formation of phosphate-induced secondary CPPs, preventing calcification of vascular smooth muscle cells [12]. However, once secondary CPPs had been formed, magnesium supplementation did not halt vascular smooth muscle cells calcification [12]. These findings suggest that magnesium supplementation may be of particular interest in early stages of CKD, when secondary CPP formation and calcium deposits in the vessel wall are not yet present. The observation by Menez et al. that the association between magnesium and PAD is weaker in patients with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 is in line with this hypothesis. Large epidemiological studies and clinical trials would be required to address the hypothesis that patients with early stages of CKD particularly benefit from magnesium supplementation.

Interestingly, Menez et al. show the lowest hazard risk of incident PAD in patients with serum magnesium levels >1.8 mEq/L, which is near the upper limit of the normal range (1.4–2.0 mEq/L). Patients who were well within the population-based reference interval already had an increased risk of PAD. Similar observations were reported in the Renal Data Registry of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy and in the CONvective TRAnsport STudy (CONTRAST) [13, 14]. These findings suggest that the clinically optimal range is higher than previously assumed and higher than the serum magnesium level that is currently strived for in the clinic.

While it seems that the jury is still out regarding the role of low serum magnesium levels and the risk of PAD in individuals with impaired kidney function, the overall results from the ARIC study set the stage for clinical trials that further explore magnesium as a target for intervention. In fact, several preclinical and clinical studies have confirmed that higher dietary magnesium intake reduces vascular stiffness and calcification. In klotho knockout mice, an animal model that actually reflects many aspects of the CKD phenotype, high magnesium intake prevented vascular calcification [15]. Similar results were obtained in uraemic rats and other genetic mouse models of calcification [16–18]. In humans, magnesium supplementation reduced vascular stiffness in overweight healthy individuals [19]. In a currently on-going clinical trial, we aim to further refine these results by addressing whether the anion that accompanies magnesium influences the association with vascular stiffness [20]. Randomized controlled trials in CKD patients demonstrated that both oral and dialysate magnesium supplementation improved calcification propensity [21, 22]. Moreover, magnesium supplementation slowed down coronary artery calcification in CKD patients [23], demonstrating the efficacy of magnesium on a clinically relevant endpoint.

Insufficient magnesium intake is abundant throughout the population [24], and a considerable proportion of the CKD and kidney transplant populations use drugs that influence magnesium uptake and metabolism, including proton-pump inhibitors and calcineurin inhibitors [25, 26]. Consequently, it remains timely and relevant to address whether magnesium deficiency plays a major role in the alarmingly high rates of cardiovascular complications. At the same time, side effects of high magnesium intake, including gastrointestinal complaints and potential disturbances of bone metabolism, should be monitored. Despite the large sample size and the long-term follow-up of the ARIC cohort, more CKD-specific data are needed to reach a final verdict on low serum magnesium as a risk factor for PAD and other cardiovascular outcomes in these patients.

FUNDING

This research was funded by grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO Veni 016.186.012) and the Dutch Kidney Foundation (Kolff 14OKG17), and is part of the NIGRAM2+ consortium, a collaboration project co-funded by the PPP Allowance made available by Health-Holland, Top Sector Life Sciences & Health, to stimulate public–private partnerships (LSHM17034) and the Dutch Kidney Foundation (16TKI02).

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTIONS

M.H.d.B. and J.H.F.d.B. drafted, revised and finalized the manuscript, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

M.H.d.B. has served as a consultant for, and received honoraria or research support (all to employer) from Amgen, Bayer, Kyowa Kirin Pharma, Pharmacosmos, Sanofi Genzyme and Vifor Fresenius Medical Care Renal Pharma. J.H.F.d.B. has nothing to disclose.

(See related article by Menez et al. Serum magnesium, bone-mineral metabolism markers and their interactions with kidney function on subsequent risk of peripheral artery disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 1878–1885)

REFERENCES

- 1. Song P, Rudan D, Zhu Y et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence and risk factors for peripheral artery disease in 2015: an updated systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2019; 7: e1020–e1030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Emdin CA, Anderson SG, Callender T et al. Usual blood pressure, peripheral arterial disease, and vascular risk: cohort study of 4.2 million adults. BMJ 2015; 351: h4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ho CY, Shanahan CM. Medial arterial calcification: An overlooked player in peripheral arterial disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2016; 36: 1475–1482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zhu D, You J, Zhao N, Xu H. Magnesium regulates endothelial barrier functions through TRPM7, MagT1, and S1P1. Adv Sci 2019; 6: 1901166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ravn HB, Korsholm TL, Falk E. Oral magnesium supplementation induces favorable antiatherogenic changes in apoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2001; 21: 858–862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. ter Braake AD, Shanahan CM, de Baaij J. Magnesium counteracts vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2017; 37: 1431–1445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sun X, Zhuang X, Huo M et al. Serum magnesium and the prevalence of peripheral artery disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Atherosclerosis 2019; 282: 196–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Menez S, Ding N, Grams ME et al. Serum magnesium, bone–mineral metabolism markers and their interactions with kidney function on subsequent risk of peripheral artery disease: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 1878–1885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hughes J, Chiu DYY, Kalra PA et al Prevalence and outcomes of proton pump inhibitor associated hypomagnesemia in chronic kidney disease. PLoS One 2018; 13: e0197400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cunningham J, Rodriguez M, Messa P. Magnesium in chronic kidney disease Stages 3 and 4 and in dialysis patients. Clin Kidney J 2012; 5: i39–i51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Massy ZA, Drüeke TB. Magnesium and cardiovascular complications of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2015; 11: 432–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. ter Braake AD, Eelderink C, Zeper LW et al. Calciprotein particle inhibition explains magnesium-mediated protection against vascular calcification. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2019; DOI: 10.1093/ndt/gfz190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sakaguchi Y, Fujii N, Shoji T et al. ; the Committee of Renal Data Registry of the Japanese Society for Dialysis Therapy. Magnesium modifies the cardiovascular mortality risk associated with hyperphosphatemia in patients undergoing hemodialysis: a cohort study. PLoS One 2014; 9: e116273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Roij Van Zuijdewijn CLM, Grooteman MPC, Bots ML et al. Serum magnesium and sudden death in European hemodialysis patients. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0143104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. ter Braake AD, Smit AE, Bos C et al. Magnesium prevents vascular calcification in Klotho deficiency. Kidney Int 2020; 97: 487–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Diaz-Tocados JM, Peralta-Ramirez A, Rodríguez-Ortiz ME et al. Dietary magnesium supplementation prevents and reverses vascular and soft tissue calcifications in uremic rats. Kidney Int 2017; 92: 1084–1099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaesler N, Goettsch C, Weis D et al. Magnesium but not nicotinamide prevents vascular calcification in experimental uraemia. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2020; 35: 65–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kingman J, Uitto J, Li Q. Elevated dietary magnesium during pregnancy and postnatal life prevents ectopic mineralization in Enpp1asj mice, a model for generalized arterial calcification of infancy. Oncotarget 2017; 8: 38152–38160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Joris PJ, Plat J, Bakker SJ et al. Long-term magnesium supplementation improves arterial stiffness in overweight and obese adults: Results of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled intervention trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2016; 103: 1260–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schutten JC, Joris PJ, Mensink RP et al. Effects of magnesium citrate, magnesium oxide and magnesium sulfate supplementation on arterial stiffness in healthy overweight individuals: a study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2019; 20: 295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bressendorff I, Hansen D, Schou M et al. The effect of increasing dialysate magnesium on serum calcification propensity in subjects with end stage kidney disease: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018; 13: 1373–1380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bressendorff I, Hansen D, Schou M et al. Oral magnesium supplementation in chronic kidney disease stages 3 and 4: efficacy, safety, and effect on serum calcification propensity—a prospective randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled clinical trial. Kidney Int Rep 2017; 2: 380–389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sakaguchi Y, Hamano T, Obi Y et al. A randomized trial of magnesium oxide and oral carbon adsorbent for coronary artery calcification in predialysis CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2019; 30: 1073–1085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Morello A, Biondi-Zoccai G, Frati G et al Association between serum magnesium levels and peripheral artery disease: a leg too short? Atherosclerosis 2019; 282: 165–166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Douwes RM, Gomes-Neto AW, Schutten JC et al. Proton-pump inhibitors and hypomagnesaemia in kidney transplant recipients. J Clin Med 2019; 8: 2162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nijenhuis T, Hoenderop JGJ, Bindels R. Downregulation of Ca(2+) and Mg(2+) transport proteins in the kidney explains tacrolimus (FK506)-induced hypercalciuria and hypomagnesemia. J Am Soc Nephrol 2004; 15: 549–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]