Abstract

Objectives:

Research indicates that the increasing population of over 25 million people in the US who have limited English proficiency (LEP) experience differences in decision making and subsequent care at end of life in the Intensive Care Unit(ICU) when compared to the general population. The objective of this study was to assess the perceptions of healthcare team members about the factors that influence discussions and decision-making about end-of-life for patients and family members with Limited English Proficiency in the ICU.

Design:

Qualitative study using semi-structured interviews with ICU physicians, nurses, and interpreters.

Setting:

Three ICUs at Mayo Clinic Rochester.

Subjects:

16 ICU physicians, 12 ICU nurses, and 12 interpreters.

Intervention:

None

Measurements and Main Results:

We conducted 40 semi-structured interviews. We identified six key differences in end-of-life decision making for patients with LEP compared to patients without LEP: 1) clinician communication is modified and less frequent, 2) clinician ability to assess patient and family understanding is impaired, 3) relationship building is impaired, 4) patient and family understanding of decision making concepts (e.g. palliative care) is impaired, 5) treatment limitations are often perceived to be unacceptable due to faith-based and cultural beliefs, and 6) patient and family decision making styles are different. Facilitators of high quality decision making in patients with LEP included: 1) pre-meeting between clinician and interpreter, 2) interpretation that communicates empathy and caring, 3) bidirectional communication of cultural perspectives, 4) interpretation that improves messaging including appropriate word choice, and 5) clinician cultural humility.

Conclusions:

End-of-life decision making is significantly different for ICU patients with LEP. Participants identified several barriers and facilitators to high quality end-of-life decision making for ICU patients and families with LEP. Awareness of these factors can facilitate interventions to improve high quality, compassionate, and culturally sensitive decision making for patients and families with LEP.

Keywords: intensive care unit, end of life, limited English proficiency, disparities, communication, cultural sensitivity, qualitative research, communication, interpreters, decision making, discussions, language barriers, preferences, barriers, facilitators

Introduction:

More than 25 million people in the United States have limited English proficiency (LEP)and this number continues to increase(1). Those who have LEP have difficulties speaking and understanding English (1, 2). A large body of research has demonstrated the adverse health effects associated with having a language barrier (3–15). In the outpatient setting at the end-of-life, patients with LEP are at risk of poor symptom control, poor understanding of their diagnosis and prognosis, and poor quality discussions about goals of care (16–18).

In the ICU, patients with LEP have been shown to have lower likelihood of do-not-resuscitate orders, lower rates of advance directive completion, and lower rates of comfort measure order use prior to imminent death (19). Decisions to limit life support also took longer for patients who had LEP when compared to the general population (19). Immigrants are also more likely to receive aggressive care in the ICU and to die in the ICU(20).

It is unclear whether these observed differences represent authentic preferences for increased intensity of life sustaining treatment or whether they represent suboptimal decision making secondary to poor bidirectional communication and potential disparities (21). Prior studies suggested that family members of patients with LEP in the ICU may be given less information about their loved one and also provided less emotional support during family conferences—suggesting that suboptimal communication may be an important consideration (22). In addition, it is challenging to parse out the specific influences of language versus culture on end-of-life decision making, at end of life. Indeed in Australia these minorities are described as a group using the term CALD-culturally and linguistically diverse, suggesting the concepts of language and culture are inevitably intertwined(23).

There is a knowledge gap in our understanding of the factors that influence end-of-life decision making in the ICU for patients who have LEP. Exploring these factors is a key step to developing interventions to improve the delivery of high quality end-of-life decision making for this growing patient population. The objective of this study was to identify and understand the barriers and facilitators that influence decision making about end-of-life care for patients with LEP in the ICU.

Methods:

We conducted a qualitative study using semi-structured interviews of ICU physicians, nurses, and interpreters. The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board approved the protocol. Informed consent was obtained from participants.

Participants

Inclusion criteria were >18 years old, working in the general medical or surgical ICUs at Mayo Clinic Rochester, and self-reported experience caring for patients with LEP. Participants were recruited via email invitation using distribution lists (113 physicians, 195 nurses, and 65 interpreters were contacted via email). We initially enrolled 10 interpreters, 10 physicians, and 10 nurses. We enrolled additional participants until data saturation was achieved. We experienced no difficulties with recruitment and cancelled several planned future interviews once data saturation was achieved.

Data Collection and Analysis

An interview guide asking a series of open-ended questions (Supplemental 2) was developed by a multidisciplinary team (AKB, CAN, CJ, and MEW) based on literature review, expert opinion, and clinical experience. We (CAN, AKB, CJ) conducted one on one in-person semi-structured interviews lasting approximately 30 minutes each between November 2017 and April 2018. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and transcripts were subsequently anonymized.

Principles of grounded theory were used to analyze the transcripts with open, axial, and selective coding using the software NVivo Version 11 (QSR Intl Inc; Burlington, MA). Thirty percent of transcripts were coded to consensus by 2 coders (AKB, CAN). All successive transcripts were coded in duplicate independently (AKB, CAN, NRE) and coders met to reach consensus on each interview. The ongoing process of coding led to refinement of the codebook and the addition of some new codes and sub-codes as well as clearer definitions of existing codes. Following completion and of coding and consensus the investigators met to develop overarching themes and select representative statements.

Results:

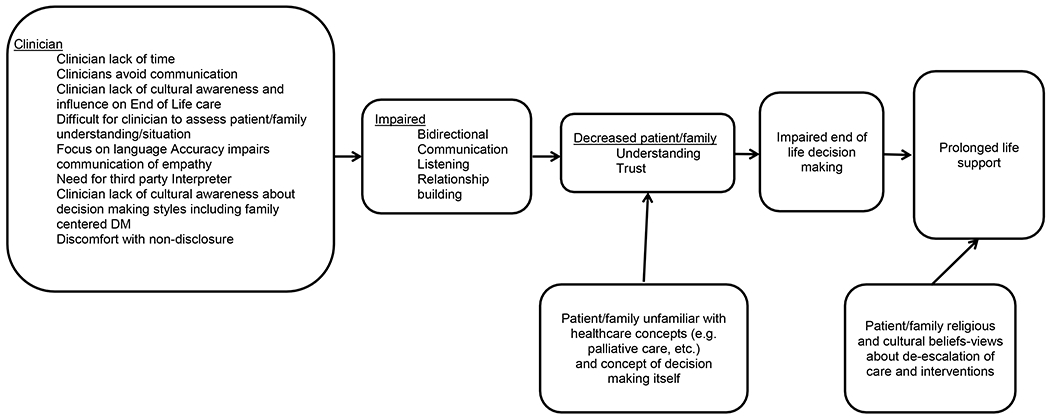

We conducted 40 interviews. Participants’ baseline characteristics are provided in Table 1. We identified 6 key barriers to and 5 key facilitators of high quality end-of-life decision making for patients with LEP (Table 2, Table 3, and Supplemental Table 1). Figure 1 provides a conceptual framework outlining the factors that influence decision making and lead to differences.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Participants

| Interpreters n=12 |

Nurses n=12 |

Physicians n=16 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 10 (83) | 11(92) | 5(31) |

| Age, years, range | 30-65 | 20-35 | 30-65 |

| Born in the United States, n (%) | 1(8) | 12(100) | 9(56) |

| Languages Interpreted, n (%) | NA | NA | |

| Spanish | 5(42) | NA | NA |

| Somali | 1(8) | NA | NA |

| Arabic | 3(25) | NA | NA |

| Mandarin Chinese | 1(8) | NA | NA |

| Lao | 1(8) | NA | NA |

| Hmong | 1(8) | NA | NA |

| Years of ICU experience, range | 2-20 | 1-11 | 4-30 |

Table 2:

Barriers to end of life decision making for ICU patients and families with LEP

| Barrier | Quote |

|---|---|

| 1) Clinician communication is modified and less frequent | |

| -Routine clinical updates are less frequent | One physician noted: “It can be awkward and sometimes sadly unfortunate that if [the patient were] English speaking you’d just stop at the door, and you say, ‘Hi. How are you? We missed you this morning. Everything is stable. We talked to your family. We’re gonna be back on afternoon rounds in a little while.’ and you just move on. Whereas, you can’t say that if they don’t speak English at all. It’s hard to just give them that update.” |

| -Decision making conversations are less frequent | One nurse commented: “[After the family meeting], all those people leave and oftentimes we’re in the room and [the patient and family] have additional questions when an interpreter isn’t there. That’s where a lot of the important discussions really happen—so you lose that piece.” |

| -Clinicians avoid difficult and time consuming conversations | One physician said: “I do think there is more of a tendency to not engage when we might otherwise if they spoke English.” |

| -Infrequent communication leads to patient and family mistrust, distress, inadvertent misconceptions | An interpreter commented: “[Waiting for an interpreter] takes time and sometimes the patient is waiting. It causes stress and tension [for the patients].” |

| -Focus on language accuracy reduces likelihood that empathy is relayed effectively | A physician said: “Even if you want to try to connect, the interpreter may not have the same inflection of empathy or concern that you’re trying to convey.” |

| -Clinicians listen less and have Less direct communication with patient | An interpreter said “It’s easier [for physicians] to talk to the son who speaks English … I think it’s just easier to talk to the other part of the family than talking to the patient.” |

| 2)Clinician ability to assess patient and family understanding is impaired | |

| - Patient and family understanding of illness, treatment options, prognosis | A physician noted: “It’s harder to assess [the patient’s health literacy] because I can’t necessarily analyze the sophistication of their language.” A physician stated: “Sometimes I feel that the patient will just get a glazed-over look . . They may or may not be understanding, but they just keep saying, ‘Yes.’” |

| -Patient and family preferences and culture or faith | A physician explained: “How much of this [disagreement] is me misinterpreting or not understanding [the family’s] perspective … just not being a worldview or culture that I know anything about.” |

| -Patient and family situational dynamics | A nurse commented: “I did have a patient [who did not speak English] … and the patient started to get kind of upset, and … I didn’t know what to do … I could see that there was some sort of conflict there and I didn’t know what they were talking about.” |

| 3) Relationship building is impaired | |

| -Focus on language accuracy can impair usual patient/clinician therapeutic relationship | A physician stated: “You’re emphasizing precision of language rather than forming a connection and having a human interaction.” |

| -Need for third party (interpreter) affects usual patient/clinician therapeutic relationship -Discussion of sensitive topics more likely to be inappropriate and ill timed |

A nurse noted: “[When using an interpreter], all that information passes through somebody else who is a stranger to you. That may circumvent the nurse/patient relationship you may develop with somebody.” An interpreter recalled” “Many times doctors and nurses don’t take into consideration when they’re asking questions about sexual preference, or … drug use, STDs or other kind of maybe legal problems that can come up when they’re asking questions. They ask those questions with the family in the room … I feel uncomfortable sometimes . . A gay person that family members didn’t know he was gay was in the ICU, and the partner was there. [The family] learned that that was a partner, not the roommate right there … that was difficult.” |

| 4) Patient/ Family understanding/ of decision making concepts (e.g. palliative care) is impaired | An interpreter noted: “Do not resuscitate or resuscitate … [Patients and families] have no idea what the concept is. It’s a different concept [for them]. They’re always gonna say, do whatever you can.” |

| 5) Treatment limitations are perceived to be unacceptable due to faith-based and cultural beliefs | A nurse stated: “I think a lot of times they [patient/family] can’t withdraw cares because that seems like they’re… actively taking (a) life.” |

| 6) Patient and family decision making styles are different | |

| -Families are not used to making decisions to limit life support | An interpreter stated: “[In my home country, the families always say to the doctor] ‘Whatever you think is the best, and it’s your decision…You know what you’re doing. Don’t ask me.’ It’s because, in our countries, we don’t have to … .make those decisions.” |

| -Many families prefer nondisclosure | A physician explained “There may be quite profound cultural differences that coincide with people of limited English proficiencies. Ideas around the illness and treatment and the role of who makes decisions and who information should be shared with.” |

| -More family members are involved in decision making | An interpreter said: “For Hispanic families, there are several family members. It’s just not immediate family. It’s just the cousins and the uncles and everybody’s there, and everybody—everybody’s opinions count.” |

Table 3:

Facilitators of end of life decision making for ICU patients and families with LEP

| Category | Illustrative Quotes |

|---|---|

| Pre-meeting between clinician and interpreter (to plan and clarify how to optimally deliver the message) | A physician told of how they usually talk with the interpreter beforehand: “If nothing else, for me to talk with [the interpreter] ahead of time and just say, ‘This is our understanding. Can you help me communicate this? If I’m not being clear, can you help me?’” A physician said: “I will always introduce myself to the interpreters, make sure they know who I am and what problem I’m hoping to address that day.” |

| Interpretation that communicates empathy and caring | One physician commented: “I remember working with one interpreter in general, and he was fantastic and really took his job seriously. I loved working with him. I mean, he would turn to me and be like—he’d want to get some more information about how to convey this better.” A physician said: “Even with the limitations of language and even working with interpreters, I think it’s crucially vital that there is signalling, both verbal and non-verbal signals that we care about the patient and we care about the family.” |

| Interpretation that communicates cultural perspectives and context bidirectionally | An interpreter explained that physicians might ask for help: “How would I say this … ‘How do I present this?’ if there’s an in-person interpreter,[it helps] just to know the culture more.” A physician stated: “Oftentimes, [the interpreter] will have cultural understandings that I don’t know…. and so it can be a little bit-not just a direct translation, but also help with cultural interpretation.” |

| Interpretation that improves messaging including with appropriate word use | Another interpreter said: “maybe the word of dying. Maybe you should change it. Maybe you can talk about…something more sweet than just dying. Something that makes the patient and t the family members more at ease.” |

| Clinician cultural competency and humility | A nurse stated: “Are we truly understanding what the (LEP) patient’s values are? It’s amazing how it’s night and day change. Once you do that and you readdress it when the dust settles. I think we could do a little better job of that”. A nurse noted: “Usually with our [Healthcare Team] admission, we ask “what are your religious preferences? What’s important to you? Who makes decisions in your family?” An interpreter recommended: “I think we [Healthcare Team] need all our providers to have enough education from the perspective of culture differences”. A physician stated: “Even if we think, ‘This is a futile process,’ [the patients and families] have their belief system. I think that every interaction I’ve had once I’ve understood that belief system, has actually been very straightforward.” |

Figure 1.

Framework of barriers to end-of-life decision making (DM) and care for patients with limited English proficiency.

Barriers to end-of-life decision making for ICU patients with LEP compared to those with no LEP

Table 2 and supplemental table 1 describe the key barriers.

Clinician communication is modified and less frequent

This includes communication about routine updates. Furthermore, conversations about decision making also occur less frequently—often due to the delayed arrival or early departure of an interpreter. Interpreters perceive that stress and tension can occur among patients and families with limited English proficiency if they are waiting for an interpreter or clinician. Debriefing after significant conversations is hampered and this can reduce iterative decision making that might otherwise occur. In addition, physicians may avoid conversations with patients who have LEP because conversations with interpreters may be time consuming. Some physicians also believe they lack the skills to have adequate discussions or fear offending patients with unfamiliar languages and cultures. Physicians may also have unconscious biases and divert attention to the needs of other patients who are more straightforward. Also, interpreters, nurses, and physicians perceive that infrequent communication leads to patient and family mistrust, distress, inadvertent misconceptions. In addition, a focus on language accuracy reduces likelihood that empathy is relayed effectively. Finally, with LEP, clinicians listen less and have less direct communication with patient. Clinicians are often more inclined to speak with family members who speak English rather than communicating directly with the patients themselves. Several interpreters noted this phenomenon.

Clinician ability to assess patient and family understanding is impaired

Clinicians may find it difficult to assess patient and family understanding about the seriousness of a diagnosis, prognosis, or treatment. Without understanding the spoken language of the patient and family, the healthcare team may also find it hard to evaluate health literacy. Clinicians are also challenged in their assessment of patient and family preferences based on culture or faith as well as limited in their ability to evaluate in passing situational family dynamics that are often important for decision making about end-of-life care.

Relationship building is impaired

The need for third party (interpreter) involvement affects usual patient/clinician therapeutic relationship. The focus on linguistic accuracy inhibits the development of the patient/clinician relationship. Sensitive topics are sometimes unintentionally and inappropriately revealed due to the clinician’s belief that since the interpreter is present as much information must be gathered as possible during the conversation.

Patient and family understanding of /familiarity with decision making concepts (e.g. palliative care) is impaired

Patients and families often struggle with general understanding as well as concepts that those who speak English are familiar with including palliative care, and code status decision making.

Treatment limitations are perceived to be unacceptable due to faith-based and cultural beliefs

Those with LEP were more likely to pursue aggressive life support interventions by accepting all offers of life support, resisting efforts to discontinue life support, and prolonging life support despite a lack of effectiveness. Many interviewees reported that patient and family cultural and religious beliefs prevented patients and families from making decision to limit or withdraw life support.

Patient and family decision making styles are different

Patients and families also often struggle with the notion of making their own decisions rather than the clinicians deciding for them. Request for non-disclosure of the diagnosis and prognosis to the patient was a frequent experience of all members of the healthcare team. Due to family centered decision making styles clinicians may need to interact with several family members simultaneously and that can be challenging.

Facilitators of high quality end-of-life decision making in the ICU for patients with LEP

Table 3 describes the key facilitators.

There are several measures that can be taken on an individual level by clinicians and interpreters to improve the quality of decision making for patients with LEP. In-person interpreters were considered the gold standard for end-of-life and goals of care discussions. As well as facilitating clear bidirectional communication, the extent to which interpreters incorporate empathy and cultural perspectives into their interactions with patients/families and clinicians can influence discussions and decision making. An interpreter noted: “For my role, I have to make sure that sides, provider, and the patient understand each other.” Another explained: “We’re part of the care team. We’re here to facilitate you both, to gain that trust.” Conducting a pre-meeting between the clinician and interpreter (to define purpose of the meeting and share background information) was considered a useful strategy to help improve quality and understanding of conversations. Furthermore, interpreters can help with messaging and word use to improve conversations. It is helpful for clinicians ask about and to recognize and accept cultural and faith-based differences in preferred care and preferred decision making approaches. While sometimes difficult, maintaining cultural humility is important. A physician elucidated: “there are very large differences between how different groups approach end-of-life care, like any complex medical decision making. Without recognizing these differences or responding to that in a meaningful way …one loses the opportunity for establishing a relationship, which is, again, the pathway or the portal to effective care for that patient”.

Discussion:

A number of studies have identified key differences in end-of-life care for ICU patients who have LEP (19, 20). The purpose of this study was to explore the perspectives of ICU physicians, bedside nurses, and interpreters to better understand this phenomenon and whether the differences noted represent disparities in communication or reflect belief systems that drive differences in preferred end of life care including increased interventions.

We have identified several key reasons for differences in end-of-life decision making in the ICU for patients who have limited English proficiency. Several of our findings have not been previously reported. Former work measuring the duration of time participants spoke during family conferences reported that LEP families with loved ones in the ICU received less information (22). Our findings go further and our qualitative data shows that LEP had an impact on frequency of routine clinical updates as well as iterative decision making over several conversations. These recurrent conversations with clinicians usually serve to inform decision making at end of life and highlight the distinct disadvantage that patients with LEP have in relation to important discussions beyond the use of an interpreter -facilitated decision making at scheduled intervals. Reduced conversation frequency may also lead to prolonged medical treatment (19, 20).

Due to perceived complexity and /or time constraints, some clinicians may avoid conversations or modify the frequency of conversations with patients who require language interpreters. While bias towards racial and ethnic minorities has been widely documented, the finding that clinicians consciously or unconsciously might avoid interactions with those who have LEP is also new and concerning (24).

Relationship building that may be taken for granted when communication is easy and the clinician and patient share certain assumptions, and an implicit understanding of various aspects of the healthcare system, is impaired for many patients with LEP. Studies have shown that when provider and patients are language-concordant or racially and culturally concordant outcomes improve and care is perceived to be better (7, 15, 25, 26).

When caring for patients with LEP, clinicians have a substantial disadvantage when reliably estimating health literacy, understanding, preferences for end-of-life care, and whether decision making is informed. The finding that patients and families have impaired understanding has face validity and a “glazed over look” may provide a clue that the patient or family member lacks confidence in the situational context of the ICU and decision making or is specifically uncomfortable with the interaction secondary to poor understanding. Accurate language interpretation alone cannot completely mitigate such comprehension difficulties. Impaired understanding extends to conceptual elements of the healthcare system as well understanding of illness, illness severity, and treatment options.

Facilitators that helped to improve end-of-life discussions and decision making included, having a pre-meeting between the clinician and the interpreter. These encounters allowed interpreters to understand the medical concerns and purpose of the conversation, gave the interpreters the opportunity to give cultural context about the patient and family to the clinicians and provide advice about word use and messaging. Interpretation that imbued empathy and respect helped clinicians convey compassion. Interpretation that checked and confirmed understanding was also an important facilitator. While pre-meetings with interpreters have been known and reported to be a useful approach to improve the quality of conversations, our specific findings about empathy are new (27, 28). Furthermore it is likely that pre-meetings will reduce the likelihood that alterations during interpretation will occur, an added benefit (29). Previous work by Hsieh and others has also endorsed a non-utilitarian approach when using interpreters and outlined the benefits of working collaboratively with them to deliver better and more empathic care not just to use them simply as linguistic instruments (30–33).

Clinician cultural competence has been widely endorsed in the last 2 decades. However, it may be better to focus on clinician humility and sensitivity as an essential quality to demonstrate caring and respect for patients from diverse backgrounds (34). This concept was supported in our study. It is important for clinicians to recognize that they do not require an encyclopedic range of knowledge about faith, spiritual and cultural differences but should be more focused on asking, responding to, and accepting differences within these realms (34). This also reduces the risk of stereotyping from generalizations (35).

Rather than reflecting a purely linguistic disadvantage, some of the factors we noted in our study may reflect confounding variables including cultural, spiritual, ethnic, and racial diversity that often occur in conjunction with patients who have LEP (23, 36, 37). Findings that signified cultural and spiritual factors(rather than linguistic capabilities) included differences in patient and family preferences, perceptions about treatment limitations, decision making styles, and the central involvement of family in decision making that might seek non-disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis to the patient (23, 38–42). Conceptual differences among diverse groups have been reported previously (43) (44) but few studies have been done to mitigate the linguistic, health literacy and cultural factors that drive these differences. (45–47).Some patients with LEP are more familiar with the US medical culture making some of the challenges we have noted less likely and the linguistic issues more prominent. First generation immigrants who are more likely to have LEP, rarely discuss end-of-life care although second generation immigrants are more likely to discuss and accept end-of-life care; this likely reflects acculturation and language acquisition (48).

This study has some limitations. First, this study was conducted at a single tertiary care medical center in the United States Midwest. Our findings may have limited generalizability to other populations and settings. The languages spoken by patients in our ICUs include: Arabic (26%), Spanish (26%), Somali (9%), Cambodian (4%), Vietnamese (3%), Lao (3%), Hmong (2%), Russian (2%), and other (25%)(19) Second, while we captured physician, nurse, and interpreter perceptions, we did not capture patient and family perceptions. This remains an important subject for future research. Third, there may be selection bias as a result of recruiting participants via email distributions lists. It is possible that those with strong opinions and an interest in this topic self-selected for this study. The data is the insights of a small number of interpreters, physicians, and bedside nurses but since data saturation was reached we believe these findings are robust. Moreover the phrase “Limited English Proficiency” (LEP) despite being the commonly used definition in the literature incorporates a wide spectrum of linguistic abilities (26, 49, 50).

Strengths of this study include the fact the data was triangulated by seeking the perspectives of three different member groups from the healthcare team. While previous studies have sought the perceptions of nurses, interpreters, and physicians, this is the first that has incorporated all of these distinct groups into one qualitative study(51, 52). All of the interviews were coded independently and in duplicate and consensus reached on each transcript where differences in coding occurred.

Conclusions:

In the ICU, end-of-life decision making for patients with LEP is significantly different than for English speaking patients. The identified barriers and facilitators to high quality end-of-life decision making are important to consider when developing interventions to improve end-of-life decision making for ICU patients and families with LEP. It is paramount that clinicians understand the potential issues that can make conversations with patients who have LEP challenging and strive to deliver compassionate and culturally sensitive care.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank Dr. Joyce Balls-Berry, Dr. Mark Wieland, Dr. Andrea Cheville for valuable input. Gratitude is also expressed to the Bioethics Research Department Mayo Clinic especially Ms. Susan Curtis, and Ms. Marguerite Robinson as well as Ms. Andrea Guerra, Ms. Yapa Xiong and Ms. Simona Prentice for advice and assistance with recruitment and scheduling of interpreter interviews.

Grant Support: This study was supported by Grant Number UL1 TR002377 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. It was also supported by a grant from the Mayo Clinic Critical Care Research Committee.

Footnotes

This work was performed at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester Minnesota.

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.American Community Survey, Detailed Languages Spoken at Home and Ability to Speak English for the Population 5 Years and Over. 2009-2013; . [Google Scholar]

- 2.LEP.gov. [cited Available from: https://www.lep.gov/faqs/faqs.html#One_LEP_FAQ

- 3.John-Baptiste A, Naglie G, Tomlinson G, et al. The Effect of English Language Proficiency on Length of Stay and In-hospital Mortality. Journal of general internal medicine 2004;19(3):221–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karliner LS, Auerbach A, Nápoles A, et al. Language barriers and understanding of hospital discharge instructions. Medical care 2012;50(4):283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karliner LS, Kim SE, Meltzer DO, et al. Influence of language barriers on outcomes of hospital care for general medicine inpatients. Journal of hospital medicine 2010;5(5):276–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, et al. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22 Suppl 2:324–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schenker Y, Karter AJ, Schillinger D, et al. The impact of limited English proficiency and physician language concordance on reports of clinical interactions among patients with diabetes: the DISTANCE study. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81(2):222–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Linderoth G, Hallas P, Lippert FK, et al. Challenges in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest - A study combining closed-circuit television (CCTV) and medical emergency calls. Resuscitation 2015;96:317–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harmsen JA, Bernsen RM, Bruijnzeels MA, et al. Patients’ evaluation of quality of care in general practice: what are the cultural and linguistic barriers? Patient Educ Couns 2008;72(1):155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng EM, Chen A, Cunningham W. Primary language and receipt of recommended health care among Hispanics in the United States. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22 Suppl 2:283–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woloshin S, Schwartz LM, Katz SJ, et al. Is language a barrier to the use of preventive services? J Gen Intern Med 1997;12(8):472–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Flores G, Abreu M, Olivar MA, et al. Access barriers to health care for Latino children. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 1998;152(11):1119–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferguson WJ, Candib LM. Culture, language, and the doctor-patient relationship. Family medicine 2002;34(5):353–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hampers LC, Cha S, Gutglass DJ, et al. Language barriers and resource utilization in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1253–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manson A Language concordance as a determinant of patient compliance and emergency room use in patients with asthma. Med Care 1988;26(12):1119–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Silva MD, Genoff M, Zaballa A, et al. Interpreting at the End of Life: A Systematic Review of the Impact of Interpreters on the Delivery of Palliative Care Services to Cancer Patients With Limited English Proficiency. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;51(3):569–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGrath P, Vun M, McLeod L. Needs and experiences of non-English-speaking hospice patients and families in an English-speaking country. The American journal of hospice & palliative care 2001;18(5):305–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chan A, Woodruff RK. Comparison of palliative care needs of English- and non-English-speaking patients. Journal of palliative care 1999;15(1):26–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barwise A, Jaramillo C, Novotny P, et al. Differences in Code Status and End-of-Life Decision Making in Patients With Limited English Proficiency in the Intensive Care Unit. Mayo Clinic proceedings 2018;93(9):1271–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yarnell CJ, Fu L, Manuel D, et al. Association between immigrant status and end-of-life care in ontario, canada. JAMA 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harhay MO, Halpern SD. End-of-life care among immigrants: Disparities or differences in preferences? JAMA 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thornton JD, Pham K, Engelberg RA, et al. Families with Limited English Proficiency Receive Less Information and Support in Interpreted ICU Family Conferences. Crit Care Med 2009;37(1):89–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Broom A, Good P, Kirby E, et al. Negotiating palliative care in the context of culturally and linguistically diverse patients. Internal medicine journal 2013;43(9):1043–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit Racial/Ethnic Bias Among Health Care Professionals and Its Influence on Health Care Outcomes: A Systematic Review. American journal of public health 2015;105(12):e60–e76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Annals of internal medicine 2003;139(11):907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parker MM, Fernández A, Moffet HH, et al. Association of patient-physician language concordance and glycemic control for limited–english proficiency latinos with type 2 diabetes. JAMA internal medicine 2017;177(3):380–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenker Y, Smith AK, Arnold RM, et al. “Her husband doesn’t speak much English”: conducting a family meeting with an interpreter. J Palliat Med 2012;15(4):494–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juckett G, Unger K. Appropriate use of medical interpreters. Am Fam Physician 2014;90(7):476–480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pham K, Thornton JD, Engelberg RA, et al. Alterations during medical interpretation of ICU family conferences that interfere with or enhance communication. Chest 2008;134(1):109–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hsieh E, Kramer EM. Medical interpreters as tools: dangers and challenges in the utilitarian approach to interpreters’ roles and functions. Patient Educ Couns 2012;89(1):158–162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsieh E, Hong SJ. Not all are desired: providers’ views on interpreters’ emotional support for patients. Patient Educ Couns 2010;81(2):192–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dysart-Gale D. Clinicians and medical interpreters: negotiating culturally appropriate care for patients with limited English ability. Family & community health 2007;30(3):237–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hadziabdic E, Hjelm K. Working with interpreters: practical advice for use of an interpreter in healthcare. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 2013;11(1):69–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tervalon M, Murray-Garcia J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of health care for the poor and underserved 1998;9(2):117–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green A, Jerzmanowska N, Green M, et al. ‘Death is difficult in any language’: A qualitative study of palliative care professionals’ experiences when providing end-of-life care to patients from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Palliative medicine 2018;32(8):1419–1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barnato AE, Anthony DL, Skinner J, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in preferences for end-of-life treatment. Journal of general internal medicine 2009;24(6):695–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barnato AE, Chang C-CH, Saynina O, et al. Influence of race on inpatient treatment intensity at the end of life. Journal of general internal medicine 2007;22(3):338–345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Searight HR, Gafford J. Cultural diversity at the end of life: issues and guidelines for family physicians. Am Fam Physician 2005;71(3):515–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crawley LM, Marshall PA, Lo B, et al. Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Annals of Internal Medicine 2002;136(9):673–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bullock K The Influence of Culture on End-of-Life Decision Making. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care 2011;7(1):83–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smith AK, Sudore RL, Pérez-Stable EJ. Palliative care for Latino patients and their families: whenever we prayed, she wept. Jama 2009;301(10):1047–1057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mancuso L Providing culturally sensitive palliative care. Nursing2018 2009;39(5):50–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fang ML, Sixsmith J, Sinclair S, et al. A knowledge synthesis of culturally-and spiritually-sensitive end-of-life care: findings from a scoping review. BMC geriatrics 2016;16(1):107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kwak J, Ko E, Kramer BJ. Facilitating advance care planning with ethnically diverse groups of frail, low-income elders in the USA: perspectives of care managers on challenges and recommendations. Health & social care in the community 2014;22(2):169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, et al. Engaging Diverse English-and Spanish-Speaking Older Adults in Advance Care Planning: The PREPARE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow M, Gillick MR, et al. Health literacy not race predicts end-of-life care preferences. Journal of palliative medicine 2008;11(5):754–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Volandes AE, Barry MJ, Chang Y, et al. Improving decision making at the end of life with video images. Medical Decision Making 2010;30(1):29–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eckemoff EH, Sudha S, Wang D. End of Life Care for Older Russian Immigrants-Perspectives of Russian Immigrants and Hospice Staff. Journal of cross-cultural gerontology 2018;33(3):229–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ngai KM, Grudzen CR, Lee R, et al. The association between limited English proficiency and unplanned emergency department revisit within 72 hours. Annals of emergency medicine 2016;68(2):213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Qureshi MM, Romesser PB, Jalisi S, et al. The influence of limited English proficiency on outcome in patients treated with radiotherapy for head and neck cancer. Patient education and counseling 2014;97(2):276–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Coleman JS, Angosta AD. The lived experiences of acute-care bedside registered nurses caring for patients and their families with limited English proficiency: A silent shift. Journal of clinical nursing 2017;26(5-6):678–689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norris WM, Wenrich MD, Nielsen EL, et al. Communication about end-of-life care between language-discordant patients and clinicians: insights from medical interpreters. Journal of palliative medicine 2005;8(5):1016–1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.