Abstract

Purpose/Objective:

Spiritual well-being has been associated with better quality of life outcomes in caregivers, but the associations among the care recipient’s functional status, the caregiver’s spiritual well-being, and the caregiver’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is unknown.

Research Method/Design:

The study examined the Spiritual Well-Being Scale in caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injury (TBI; n = 335). Participants completed measures from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System, the Quality of Life in Caregivers of TBI, and the Caregiver Appraisal Scale. The Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory–4 (MPAI-4) measured care recipient’s functional status. The association between religious well-being and existential well-being and HRQOL were examined with Pearson correlation coefficients. Multiple linear regressions examined the interaction between caregiver well-being and care recipient functional status on HRQOL outcomes accounting for demographic variables.

Results:

Less favorable caregiver HRQOL was associated with military affiliation, male status, spousal caregiver relationship, and White race. MPAI-4 was moderately associated with all HRQOL subdomains. For spiritual well-being, existential well-being was moderately correlated with 9 of 16 HRQOL subdomains in comparison to religious well-being that demonstrated small correlations with 3 of 16 subdomains. MPAI-4 had negative effects on HRQOL regardless of spiritual well-being with higher existential well-being reducing the negative impact of the care recipient’s functional impairment on HRQOL for significant HRQOL interactions.

Conclusions/Implications:

Interventions that encourage development and maintenance of life purpose and meaning in caregivers of persons with TBI, and less so, spirituality, might have beneficial effects on HRQOL when the person with injury has more functional limitations.

Keywords: traumatic brain injury, brain injuries, caregivers, rehabilitation, spirituality

Introduction

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) affects more than 1.7 million Americans per year, and though many individuals have a good recovery, those with severe injuries experience significant functional and psychosocial changes (Faul, Xu, Wald, & Coronado, 2010). Associated chronic sequelae can impact an individual’s ability to independently care for themselves, maintain gainful employment, and successfully navigate interpersonal relationships with significant others (Jorge et al., 2004; Silva, Ownsworth, Shields, & Fleming, 2011; Soo & Tate, 2007; Tate & Broe, 1999). Given the complexity of recovery for individuals following TBI, such individuals might rely on care partners, such as friends or family, to compensate for their loss in independent functioning and productivity (Knight, Devereux, & Godfrey, 1998). Caring for individuals with TBI can be a long-term undertaking that exposes caregivers to a number of psychosocial stressors resulting in a high rate of emotional distress and burden, both at the early stages of TBI rehabilitation and chronically thereafter (Bayen et al., 2013; Brooks, Campsie, Symington, Beattie, & McKinlay, 1986; Ennis, Rosenbloom, Canzian, & Topolovec-Vranic, 2013; Kreutzer et al., 2009; Marsh, Kersel, Havill, & Sleigh, 1998b; Norup, Kristensen, Siert, Poulsen, & Mortensen, 2011; Norup, Siert, & Lykke Mortensen, 2010; Norup, Welling, Qvist, Siert, & Mortensen, 2012; Turner et al., 2010).

One psychosocial outcome frequently discussed within the caregiver literature is diminished health-related quality of life (HRQOL; Arango-Lasprilla et al., 2011; Gulin et al., 2014; Knight et al., 1998; Kratz, Sander, Brickell, Lange, & Carlozzi, 2017; Marsh, Kersel, Havill, & Sleigh, 1998a; Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, Harris, & Moldovan, 2007). HRQOL refers to one’s perception of his or her physical, social, and psychological health in the context and interplay between individual experiences, expectations, values, and attitudes (Arango-Lasprilla et al., 2011; Chronister, Chan, Sasson-Gelman, & Chiu, 2010). Care partners of persons with TBI report poorer HRQOL than the general population; caregiver HRQOL is incrementally influenced by the injured individual’s level of disability, as well as the nature of the caregiver and recipient of care, such as kinship (e.g., spouse vs. parent caregiver; A. Norup et al., 2012; Arango-Lasprilla et al., 2011; Knight et al., 1998; Koskinen, 1998; McPherson, Pentland, & McNaughton, 2000; Nanda & Andresen, 1998; Norup et al., 2011; Norup et al., 2010). Reductions in HRQOL include caregiver psychological burden, depression, anxiety, and social isolation (Corrigan, Bogner, Mysiw, Clinchot, & Fugate, 2001; Gulin et al., 2014; Knight et al., 1998; Marsh et al., 1998a; Norup et al., 2013; Rotondi et al., 2007). Research demonstrates that both caregivers’ pre- and postinjury HRQOL is related to caregiver stress. Noted preinjury HRQOL factors include medical illness, psychological difficulties, and escape-avoidance coping style (Davis et al., 2009).

Understanding the multitude and synergistic effects of adjustment and coping factors related to HRQOL is imperative for the development of interventions aimed at improving caregiver’s HRQOL. Existing literature indicates that some of the strongest postinjury predictors of caregiver HRQOL involve coping resources, including both perceived social support and a caregivers’ coping style (Hanks, Rapport, & Vangel, 2007). Ergh and colleagues (Ergh, Hanks, Rapport, & Coleman, 2003; Ergh, Rapport, Coleman, & Hanks, 2002) have shown that perceived social support moderates both caregiver psychological distress and life satisfaction. In their research, caregivers without adequate social support, relative to those with adequate support, reported higher levels of distress with increasing time postinjury, as well as greater distress and lower satisfaction with greater care recipient cognitive dysfunction and unawareness of deficits (Ergh et al., 2003; Ergh et al., 2002). Notably, psychological adjustment and coping resources appear to affect not only the caregiver, but also the care recipient. Poor caregiver social support is associated with poor psychological well-being in the person with the TBI. Similarly, poor caregiver psychological well-being is associated with higher care recipient (person with TBI) disability on follow-up (Vangel, Rapport, & Hanks, 2011). In addition, internal coping factors, such as the effectiveness of caregiver’s coping are related to HRQOL and overall well-being in both the caregiver and the individual with TBI (Chronister & Chan, 2006). Chronister and Chan (2006) described commonly utilized coping strategies in caregivers of individuals with TBI, finding that strategies tend to be problem-focused (e.g., finding solutions to specific problems), emotion-focused (e.g., accepting the current situation and taking an approach of positive reappraisal), or avoidant (e.g., emotional distancing or denial; Chronister & Chan, 2006).

Interventions focused on coping resources, such as caregiver social support, have demonstrated positive effects on caregiver HRQOL. Hanks, Rapport, Wertheimer, and Koviak (2012) demonstrated that increased caregiver social support, through involvement in a peer mentoring program, was associated with better community integration for the caregiver. Cumulatively, research findings stress the importance of caregiver access to avenues of social support, including but not limited to, respite care and peer mentoring. Furthermore, research highlights the continued benefit of identifying HRQOL-related adjustment and coping factors around which caregiver intervention can be designed. Spiritual well-being is one such factor, which has been thoroughly explored within persons with TBI and caregivers of those with other chronic medical conditions (e.g., cancer, Alzheimer’s disease), but has been examined far less frequently in caregivers of person’s with TBI.

Spiritual well-being has been associated with better mental health and quality of life outcomes. Persons with TBI, similar to individuals with chronic medical conditions and their caregivers, use religion and spirituality as a mechanism to effectively cope with rehabilitation, community reintegration, and the long-term effects of brain injury (Campbell, Yoon, & Johnstone, 2010; Kilpatrick & McCullough, 1999; Nightingale, 2003; Shah, Snow, & Kunik, 2002). C. G. Ellison and George (1994) made a distinction between two facets of spiritual well-being, asserting that religious well-being denoted a specific relationship with God, while existential well-being denoted the conviction that there are purpose and meaning in one’s life. In addition to the benefits of emotional support, either from a religious community or from a sense of connection to a higher power, spiritual beliefs attribute meaning and purpose to human suffering. The divine is often experienced as a comforting presence of unconditional love, which might assist in the acceptance of immediate circumstances and result in better outcomes (Koenig, 2013).

The spiritual/religious versus existential well-being distinction is important, as research is mixed on how types of spiritual well-being are related to HRQOL. Research with cancer survivors, specifically examining the subconstructs of spiritual well-being (religious vs. existential), reported that existential well-being fully mediated religious well-being’s effect on cancer survivor’s HRQOL (Edmondson, Park, Blank, Fenster, & Mills, 2008). In contrast, the perception of connectedness to a higher power was more predictive of well-being and improved functional outcomes than engagement in specific religious practices or a nonreligious sense of purpose in one study of persons with TBI (Waldron-Perrine et al., 2011). Riley and colleagues (Riley et al., 1998) identified a third type of spiritual well-being, nonspiritual. They found that, in comparison to a nonspiritual group of individuals with chronic illness, those with higher religious or existential well-being demonstrated better HRQOL. Noteworthy, the existential well-being group demonstrated the highest HRQOL. The authors posited that religiosity and faith might contribute to overall spiritual well-being but might not be necessary (Riley et al., 1998).

Beyond spiritual and religious coping in non-TBI persons and caregivers, less is known about the spiritual well-being construct in caregivers of persons with TBI. With the intent to identify HRQOL-related adjustment and coping factors for future caregiver intervention development, the current study examined caregiver spiritual well-being in relation to caregiver HRQOL at different levels of functional impairment in the individual with TBI. Injury severity is consistently shown to impact HRQOL outcomes for both the person with TBI and their care-partner. Specifically, in the context of varying levels of functional status in the person with injury, spiritual well-being in the caregiver was examined in relation to caregiver’s general psychological functioning (e.g., emotional support, social isolation), their perception of the caregiving role, and their experiences of caregiver-specific psychological stress (e.g., caregiver-specific anxiety). It has been hypothesized that greater spiritual well-being is associated with better caregiver HRQOL.

Method

Participants

Data for the current study was analyzed retrospectively. The initial sample consisted of 534 participants enrolled in the Quality of Life in Caregivers of TBI (TBI-CareQOL) study which aimed to develop and validate measures of HRQOL specific to caregivers of persons with TBI (Carlozzi, Kallen, Hanks, Hahn, et al., 2019). Only 335 participants of the original 534 were available for the current analysis secondary to limitations in data use and dissemination. One study site only granted permission to disseminate findings listed in the primary study aims and thus their participants (n = 199) were unavailable for the current project. Data collection for the current analysis occurred at the University of Michigan (Ann Arbor, MI), TIRR Memorial Hermann (Houston, TX), Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan (RIM; Detroit, MI), and James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital (Tampa, FL). All data collection sites gained approval for this study through their respective Internal Review Boards and Human Investigation Committees. Caregivers of civilians with TBI were recruited at University of Michigan, TIRR Memorial Hermann, and RIM through existing TBI caregiver databases and medical record data capture systems (Hanauer, Mei, Law, Khanna, & Zheng, 2015); caregivers of service members/veterans TBI were recruited through community-based outreach at the University of Michigan and through medical record systems and both hospital-based and community outreach at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital. All data collection sites gained approval for this study through their respective Internal Review Boards and Human Investigation Committees and caregivers provided informed consent prior to their participation in this study.

For eligibility, the caregiver must have been caring for at least one year post injury an individual, 18 years or older, who met the following criteria: a medically documented complicated mild, moderate, or severe TBI based on TBI Model Systems criteria for civilians with TBI (Corrigan et al., 2012), or a medically documented diagnosis of a mild, moderate, or severe TBI by a military or Veteran Affairs treatment facility for service members/veterans.

Caregivers were asked the following question, “On a scale of 0 to 10, where 0 is no assistance and 10 is assistance with all activities, how much assistance does the person you care for require from you to complete activities of daily living due to problems resulting from his or her TBI? Only caregivers who indicated a response of ≥1 were included in the study. Activities could consist of personal hygiene, dressing and undressing, housework, taking medications, managing money, running errands, shopping for groceries or clothing, transportation, meal preparation and cleanup, remembering things, and so forth?”

Measures

Demographics.

Caregiver demographic information including age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, and years in the caregiver role were collected using Assessment Center, a secure online data collection platform. Demographics of the person with injury, including age, gender, time since injury, cause of injury, and method of injury were collected from medical records when available.

Spiritual Well-Being Scale (SWBS; C. W. Ellison, 1983; Paloutzian & Ellison, 1982).

The SWBS is a 20-item measure that assesses spirituality and meaning. Items cover two subscales including religious well-being (RWBS; e.g., “My relation with God contributes to my sense of well-being”) and existential well-being (EWBS; e.g., “I feel very fulfilled and satisfied with life”). Notably, the SWBS instructions highlight that some statement items refer to God and allow the respondee to “substitute another idea that calls to mind the divine or holy” if the respondee is not comfortable with the word as stated. Each item is rated on a six-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), with negatively worded items being reverse scored. Scores for the total SWBS range from 20 to 120 with higher scores indicating greater spiritual well-being. Scores on the EWBS and RWBS range from 10 to 60, where higher scores indicate greater well-being.

Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory Version 4 (MPAI-4; Malec, 2005).

The MPAI-4 is a measure of caregivers’ perceptions of the ability, adjustment, and participation of the person with injury. The measure consists of 35 items rated from 0 (none) to 4 (severe problem). The MPAI-4 is scored on a T metric with a mean of 50 (SD = 10); higher scores indicate more severe impairment. Relative to individuals with acquired brain injury (ABI), a T score between 40 and 60 would be considered average for individuals seen in outpatient, community-based, or residential rehabilitation following brain injury. Specifically, a T score above 60 would be suggestive of severe limitations in persons with TBI in comparison to the suggestion of relatively good outcomes in those with a T score below 30. T scores between 40 and 50 are associated with mild to moderate perceived limitations in the person with TBI and T scores between 30 and 40 would suggest mild limitations in the person with TBI.

Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with TBI (TBI-CareQOL; Carlozzi, Kallen, Hanks, Hahn, et al., 2019).

The TBI-CareQOL measurement system was developed to assess HRQOL concerns specific to caregivers of persons with TBI. The reliability and validity of these measures has been demonstrated for caregivers of persons with TBI (Carlozzi, Lange, et al., 2019). For the current analysis, TBI-CareQOL measures of Caregiver Specific Anxiety (Carlozzi, Kallen, Sander, et al., 2019), which assesses feelings of worry related to the behavior and well-being of the person with TBI, Caregiver Strain (Carlozzi, Kallen, Ianni, Hahn, et al., 2019), which measures feelings of being overwhelmed or stressed in relation to the caregiver role, Feeling Trapped (Carlozzi, Kallen, Hanks, Hahn, et al., 2019), which assesses feelings of being unable to do things due to caregiver responsibilities, and Feelings of Loss-Self (Carlozzi, Kallen, Ianni, Sander, et al., 2019), which measures feelings of sorrow over personal changes that have resulted from being in the caregiving role. Each item in the aforementioned item banks is on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Each of these measures were administered as computer adaptive tests (CATs), where participants completed items depending on their previous responses in an order that maximizes reliability. Each item in the aforementioned item banks is on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). As such, raw values are not accurately representative of participant responses. TBI-CareQOL measures are scored on a T metric with a mean of 50 (SD = 10); higher scores indicate worse outcomes.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS; Cella et al., 2010).

PROMIS was developed to examine a variety of HRQOL domains in the general population. The reliability and validity of PROMIS measures have been demonstrated in caregivers of persons with TBI (Carlozzi, Hanks, et al., 2019; Carlozzi, Ianni, Lange, et al., 2019; Carlozzi, Ianni, Tulsky, et al., 2019). For the current analysis, PROMIS measures of Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Anger, Ability to Participate in Social Roles and Activities (SRA), Emotional Support, Satisfaction with SRA, and social isolation were used. Items are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never/not at all) to 5 (always/very much). Each of these measures were administrated using CATs. As such, raw values are not accurately representative of participant responses. Items are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (never/not at all) to 5 (always/very much). Each PROMIS measure is scored on a T metric with a mean of 50 (SD = 10); higher scores indicate more of the named construct being measured (i.e., higher depression scores mean more depression).

Caregiver Appraisal Scale (CAS; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984).

The CAS is a 47-item questionnaire that measures both positive and negative perceptions of the caregiving role. Each item is rated on a five-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Struchen and colleagues (2002) previously validated the measure in caregivers of persons with TBI, ultimately using 35 items of which were summed under four identified CAS domains. This scoring system was later replicated and used with moderate to severe TBI in Hanks et al. (2007). CAS domains include Perceived Burden (e.g., perceived negative impact of caregiving on the caregiver’s life), Caregiver Satisfaction (e.g., positive or negative fulfillment from caregiving role), Caregiver Ideology (e.g., identified reasons for being a caregiver such as family tradition), and Caregiver Mastery (e.g., caregiving self-efficacy). Higher scores on the CAS indicate more positive aspects of being a caregiver (e.g., higher burden scores mean less burden).

Analysis Plan

Data analysis for the current study was conducted using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., 2013). Demographic variables were calculated using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Pearson correlations were conducted to examine the relationship between the MPAI-4, EWBS, RWBS, and 16 HRQOL measures. HRQOL measures included four TBI-CareQOL measures (i.e., Caregiver–Specific Anxiety, Caregiver Strain, Feeling Trapped, Feelings of Loss–Self), eight PROMIS measures (i.e., Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Anger, Ability to Participate in SRA, Emotional Support, Satisfaction with SRA, and Social Isolation), and four CAS domains (i.e., Perceived Burden, Caregiver Satisfaction, Caregiver Ideology, and Caregiver Mastery). Correlations were also conducted between select demographic variables (military status of the person with TBI, caregiver gender, caregiver race, and relationship to the person with TBI) and HRQOL outcomes. Based on preliminary analyses, these four demographic variables were then included in subsequent models. Thirty-two multiple linear regression models, including military status of the person with TBI, caregiver gender, caregiver race, and relationship to the person with TBI, were analyzed to determine if spiritual well-being (EWBS/RWBS) moderated the association between functional status (MPAI-4) of the person with TBI (16 regressions each) and caregiver’s HRQOL. These models included two main fixed effects (i.e., EWBS/RWBS and MPAI-4), and an interaction between EWBS/RWBS and MPAI-4 to examine the slope change between the two continuous variables. For, EWBS, simple (conditional) slope estimates were tested at varying levels to determine at which point the slope of MPAI-4 became insignificant (Aiken & West, 1991). A Benjamini–Hochberg procedure with a false discovery rate of 10% was utilized to correct for multiple comparisons (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Results

We examined data for 335 caregivers. Demographic, injury, and caregiving statistics are presented in Table 1. Correlation analyses between demographic characteristics and the 16 HRQOL subdomains were largely significant (Tables 2 and 3). For TBI-CareQOL measures (Caregiver–Specific Anxiety, Caregiver Strain and Feeling Trapped and Feelings of Loss–Self), mean scores were higher for military/veterans with TBI compared to civilians with TBI (p < .001) and for male caregivers as compared to female caregivers (p < .003). For all four TBI-CareQOL measures, spouses reported significantly higher scores as compared to other family members (p < .001). Notably, spouses reported significantly higher scores on the measure of Feeling Trapped relative to all other caregivers (parents, other family, nonfamily; p < .001). Caregivers identifying as White reported higher scores as compared with caregivers identifying as Black for Caregiver Strain and Feelings of Loss–Self (p < .005). Both caregivers identifying as White or Other race reported higher scores for Feeling Trapped as compared with those identifying as Black (p < .005). Caregiver specific anxiety did not differ by caregiver racial identification.

Table 1.

Demographic Information

| Characteristic | N = 335 |

|---|---|

| Caregiver descriptive data | |

| Age, M (SD) | 47.1 (14.5) |

| Years in caregiver role, M (SD) | 7.4 (4.6) |

| Gender, % | |

| Male | 14.6 |

| Female | 85.4 |

| Race, % | |

| White | 77.3 |

| Black | 14.3 |

| Other | 8.4 |

| Ethnicity, % | |

| Non-Hispanic | 90.1 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 9.9 |

| Relationship, % | |

| Spouse | 46.9 |

| Parent | 28.7 |

| Other family | 17.9 |

| Other | 2.6 |

| Education, % | |

| Less than high school | 5.7 |

| High school/equivalent | 13.4 |

| More than high school | 80.9 |

| Person with injury descriptive data | |

| Age, M (SD) | 41.5 (13.1) |

| Time since injury, M (SD) | 8.9 (6.3)a |

| MPAI-4 T score, M (SD) | 51.8 (14.7) |

| Gender, % | |

| Male | 84.4 |

| Female | 15.6 |

| Severity, % | |

| Mild | .6 |

| Complicated mild | 16.1 |

| Moderate | 12.2 |

| Severe | 40.6 |

| Penetrating | 3.9 |

| Unknown | 26.6a |

| Cause of injury, % | |

| Motor vehicle accident | 43.2 |

| Bicycle accident | 2.7 |

| Pedestrian struck by motor vehicle | 5.7 |

| Fall | 12.6 |

| Assault/gunshot | 12.6 |

| Struck by/thrown against object | 14.1 |

| Other | 5.5 |

| Unknown | 3.6 |

| Patient-reported outcomes, M (SD) | |

| EWBS | 44.5 (9.1) |

| RWBS | 45.6 (13.7) |

| TBI-CareQOL-Caregiver Specific Anxiety | 53.2 (9.7) |

| TBI-CareQOL-Caregiver Strain | 50.5 (10.5) |

| TBI-CareQOL-Feeling Trapped | 49.7 (9.3) |

| TBI-CareQOL-Feelings of Loss-Self | 49.3 (10.5) |

| PROMIS-Anxiety | 53.5 (10.7) |

| PROMIS-Depression | 52.5 (9.8) |

| PROMIS-Fatigue | 54.5 (10.6) |

| PROMIS-Anger | 52.2 (10.2) |

| PROMIS-Ability to Participate in SRA | 49.5 (10.7) |

| PROMIS-Emotional Support | 46.9 (10.1) |

| PROMIS-Satisfaction with SRA | 46.9 (9.7) |

| PROMIS-Social Isolation | 50.1 (11.3) |

| CAS-Perceived Burden | 45.8 (14.6) |

| CAS-Satisfaction | 43.4 (6.1) |

| CAS-Ideology | 14.6 (3.8) |

| CAS-Mastery | 13.6 (3.0) |

Note. For this sample, motor vehicle accidents include accidents/roll- overs resulting from improvised explosive devices. MPAI-4 = Mayo- Portland Adaptability Inventory; EWBS = Existential Well-Being subscale; TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Traumatic Brain Injury; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale.

Available medical records for the military sample did not characterize severity or time since injury (n = 79) and caregivers provided other demographic information.

Table 2.

Means (Standard Deviations in Parentheses) Based on Military Status and Relationship to the Person With TBI for HRQOL Measures

| Military status |

Relationship with person with TBI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Military (n = 151) | Civilian (n = 184) | p | Spouse (n = 157) | Parent (n = 96) | Other family (n = 59) | Nonrelated (n = 22) | p |

| TBI-CareQOL | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 56.6(8.1) | 50.4 (10.0) | <.001 | 55.3 (9.3) | 52.3 (8.9) | 50.2 (10.9) | 49.9 (9.0) | <.001b |

| Caregiver Strain | 54.8 (8.9) | 47.1 (10.5) | <.001 | 53.8 (9.7) | 48.9 (10.7) | 45.7 (11.1) | 47.7 (6.7) | <.001a,b |

| Feeling Trapped | 54.8 (7.9) | 45.6 (8.3) | <.001 | 52.5 (8.9) | 47.5 (8.4) | 45.0 (8.8) | 46.2 (7.3) | <.001a,b,c |

| Feelings of Loss | 52.8 (9.5) | 46.5 (10.5) | <.001 | 51.9 (10.1) | 48.7 (10.2) | 45.1 (10.7) | 45.9 (10.1) | <.001b |

| PROMIS | ||||||||

| Anxiety | 56.1 (10.5) | 51.4(10.5) | <.001 | 56.0 (10.0) | 52.2 (10.6) | 49.9 (11.6) | 51.2(10.4) | .001a,b |

| Depression | 55.1 (9.3) | 50.4 (9.7) | <.001 | 55.0 (8.9) | 51.2(9.9) | 49.1 (10.6) | 50.1 (9.2) | <.001a,b |

| Fatigue | 59.7 (10.4) | 50.9 (9.4) | <.001 | 58.2 (10.1) | 52.6 (10.3) | 49.2 (10.0) | 50.2 (6.7) | <.001a,b,c |

| Anger | 54.1 (10.2) | 50.7 (9.9) | .002 | 54.5 (9.7) | 50.6 (9.8) | 49.6(11.2) | 50.3 (9.2) | .001a,b |

| Participate in SRA | 45.1 (10.1) | 53.1 (9.8) | <.001 | 45.4 (10.2) | 52.3 (9.8) | 54.3 (10.7) | 53.1 (7.1) | <.001a,b,c |

| Emotional Support | 44.0 (9.3) | 49.3 (10.2) | <.001 | 44.6 (9.2) | 48.9 (10.1) | 47.9 (11.7) | 52.1 (8.3) | <.001a,b |

| Satisfaction with SRA | 44.3 (8.6) | 49.1 (10.0) | <.001 | 44.2 (8.4) | 48.4 (10.1) | 50.2(11.3) | 51.0(6.4) | <.001a,b,c |

| Social Isolation | 54.5 (11.5) | 46.5 (9.7) | <.001 | 54.2 (11.3) | 47.1 (9.6) | 46.2(11.3) | 44.5 (7.5) | <.001a,b,c |

| CAS | ||||||||

| Perceived Burden | 38.9 (13.0) | 51.4(13.5) | <.001 | 40.2 (14.1) | 49.4 (13.5) | 52.4 (13.7) | 51.8 (11.3) | <.001a,b,c |

| Satisfaction | 44.2 (6.2) | 42.8 (6.0) | .04 | 43.2 (6.3) | 44.3 (5.5) | 42.9 (7.1) | 43.4 (4.4) | .47 |

| Ideology | 15.4 (3.6) | 16.0 (3.9) | .001 | 14.8 (3.8) | 14.4 (3.8) | 14.4 (3.7) | 14.9 (4.5) | .85 |

| Mastery | 13.4 (2.8) | 13.8 (3.1) | .18 | 13.8 (3.0) | 13.5 (3.1) | 13.4 (3.0) | 13.4 (2.9) | .82 |

Note. TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Traumatic Brain Injury; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale; SRA = Social Roles and Activities. Values with different subscripts indicate significant group differences, which are as follows:

Spouses differ from parents.

Spouses differ from other family.

Spouses differ from nonrelatives.

Table 3.

Means (Standard Deviations in Parentheses) Based on Caregiver Gender and Caregiver Race for HRQOL Measures

| Caregiver gender |

Caregiver race |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | Male (n = 49) | Female (n = 286) | p | White (n = 259) | Black (n = 48) | Other race (n = 28) | p |

| TBI-CareQOL | |||||||

| Anxiety | 49.3 (9.2) | 52.8 (9.6) | .002 | 53.6 (9.4) | 50.5 (10.7) | 53.6 (10.2) | .13 |

| Caregiver Strain | 46.0 (7.6) | 51.3 (10.8) | <.001 | 45.8 (10.2) | 45.8 (11.0) | 51.4 (10.8) | .004a |

| Feeling Trapped | 45.9 (6.9) | 50.4 (9.5) | .002 | 50.3 (9.3) | 45.7 (8.0) | 51.4(9.9) | .004a,b |

| Feelings of Loss | 44.7 (10.0) | 50.1 (10.4) | <.001 | 50.2 (10.3) | 44.3 (10.5) | 50.2 (10.8) | .002a |

| PROMIS | |||||||

| Anxiety | 56.1 (10.5) | 45.9 (9.5) | 54.8 (10.4) | 54.1 (10.7) | 49.4 (10.6) | 55.0 (10.1) | .02a |

| Depression | 55.1 (9.3) | 45.6 (8.8) | 53.7 (9.5) | 53.1 (9.8) | 47.3 (9.2) | 55.8 (8.1) | <.001a,b |

| Fatigue | 59.7 (10.4) | 48.5 (7.6) | 55.5 (10.7) | 55.1 (10.9) | 50.2 (9.1) | 55.8 (8.9) | .01a |

| Anger | 54.1 (10.2) | 47.9 (9.5) | 53.0(10.1) | 52.5 (10.2) | 49.9 (9.7) | 53.9 (10.5) | .19 |

| Participate in SRA | 45.1 (10.1) | 54.8 (8.7) | 48.5 (10.7) | 48.8 (10.8) | 54.3 (8.4) | 47.5 (11.3) | .003a,b |

| Emotional Support | 44.0 (9.3) | 48.3 (9.8) | 46.6 (10.2) | 47.0 (10.3) | 47.2 (10.2) | 45.4 (8.9) | .70 |

| Satisfaction with SRA | 44.3 (8.6) | 49.8 (7.7) | 46.4 (9.9) | 46.5 (9.6) | 48.9 (10.3) | 47.6 (9.2) | .26 |

| Social Isolation | 54.5 (11.5) | 45.0 (9.2) | 50.9 (11.4) | 50.6(11.5) | 46.6 (8.7) | 51.4 (12.1) | .06 |

| CAS | |||||||

| Perceived Burden | 38.9 (13.0) | 51.5 (11.1) | 44.8 (15.0) | 45.3 (15.0) | 50.3 (11.9) | 42.7 (14.6) | .04 |

| Satisfaction | 44.2 (6.2) | 42.8 (5.8) | 43.5 (6.2) | 44.0 (6.0) | 42.1 (6.1) | 41.0(7.1) | .01a |

| Ideology | 15.4 (3.6) | 14.5 (3.8) | 15.5 (3.6) | 14.4 (3.7) | 15.9 (4.1) | 14.3 (4.0) | .03a |

| Mastery | 13.4 (2.8) | 12.4(3.1) | 13.8 (3.0) | 13.8 (3.1) | 12.7 (2.4) | 13.4(3.3) | .06 |

Note. TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Traumatic Brain Injury; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale; SRA = Social Roles and Activities.

indicate significant group differences.

For PROMIS measures, mean scores were higher for military/veterans with TBI compared with civilians with TBI for Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Anger, Social Isolation, and lower for Perceived Emotional Support, Ability to Participate in SRA and Satisfaction with SRA (ps < 0.003). Similarly, male caregivers reported higher scores relative to female caregivers for Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Anger, Social Isolation (p < .001), and lower scores for Ability to Participate in SRA and Satisfaction with SRA (p < .03). Sex differences were not found for Emotional Support. For caregiver type, spouses reported higher scores for PROMIS Fatigue, Social Isolation and lower scores for Ability to Participate in SRA and Satisfaction with SRA as compared to all other caregivers (parents, other family, nonfamily). For all other PROMIS measures spouses reported higher scores for Anxiety, Depression and Anger, and lower for Emotional Support in comparison to parents and other family, but not nonfamily caregivers. Caregivers identifying as White reported higher scores as compared to caregivers identifying as Black for Anxiety and Fatigue (p < .05). Both caregivers identifying as White or Other race reported higher scores for Depression and lower scores for Ability to Participate in SRA in comparison to caregivers identifying as Black (p < .004). Anger, Social Isolation, Emotional Support, and Satisfaction with SRA were unrelated to caregiver racial identification.

For CAS measures, mean scores were lower for military/veterans with TBI compared with civilians with TBI for Perceived Burden and Ideology and higher for Satisfaction, (ps < 0.05). Mastery was unrelated to TBI population. Male caregivers reported higher scores relative to female caregivers for Perceived Burden (p = .003), but lower scores for Ideology and Mastery (p = .05). Satisfaction did not differ between male and female caregivers. Lower scores for Perceived Burden were also noted for spouses relative to all other caregivers (parents, other family, nonfamily; p < .001). Caregiver type was unrelated to all other CAS measures. Caregivers identifying as White reported higher scores as compared to caregivers identifying as Black for Satisfaction, and lower scores for ideology (ps < 0.05). Perceived Burden and Mastery were unrelated to caregiver racial identification. Across measures, there were no differences between parents and other family, parents and nonrelatives, or other family and nonrelatives for any HRQOL measures; there were no differences between White race and other race for any HRQOL measures.

Correlation analyses indicated that MPAI-4 was significantly and moderately associated with each of the 16 HRQOL subdomains, except for CAS Satisfaction (r = −0.03; Table 4). EWBS was moderately correlated with each of the HRQOL measures except for CAS Ideology (r = .00). RWBS had fewer significant correlations, all small effects, with no correlation with PROMIS Fatigue (r = −0.06), Ability to Participate in SRA (r = .08), Satisfaction with SRA (r = .09), or CAS Mastery (r = .02).

Table 4.

MPAI-4, Existential Well-Being, and Outcome Measure Correlations

| Pearson r |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | MPAI-4 | EWBS | RWBS |

| TBI-CareQOL | |||

| Caregiver Specific Anxiety | .61 | −.32 | −.14 |

| Caregiver Strain | .58 | − .40 | −.12 |

| Feeling Trapped | .67 | − .40 | −.15 |

| Feelings of Loss | .58 | −.52 | −.16 |

| PROMIS | |||

| Anxiety | .38 | −.45 | −.12 |

| Depression | .38 | −.51 | −.13 |

| Fatigue | .47 | − .40 | − .06* |

| Anger | .32 | − .43 | −.15 |

| Ability to Participate in SRAa | −.52 | .45 | .08* |

| Emotional Supporta | −.40 | .40 | .14 |

| Satisfaction with SRAa | −.44 | .46 | .09* |

| Social Isolation | .49 | −.53 | −.15 |

| CAS | |||

| Perceived Burdena | −.63 | .51 | .11 |

| Satisfactiona | −.03* | .40 | .14 |

| Ideologya | .20 | .00* | .16 |

| Masterya | −.29 | .36 | .02* |

Note. MPAI-4 = Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (4th ed.); EWBS = Existential Well-Being subscale; RWBS = Religious Well- Being subscale; TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; SRA = Social Roles and Activities; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale.

Higher scores indicate better HRQOL.

p > .05.

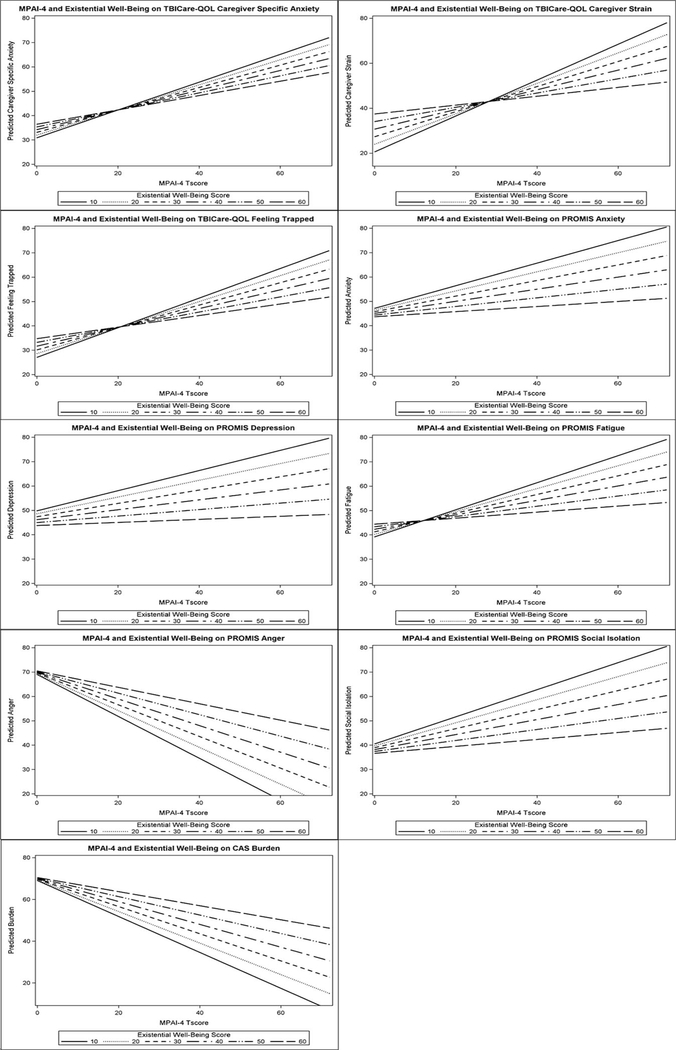

For EWBS analyses, greater functional impairment of the person with injury was associated with less favorable caregiver HRQOL outcomes (TBI-CareQOL, PROMIS, CAS). Noteworthy, the relationship between functional impairment and HRQOL significantly weakened as EWBS increased (see Figure 1). Specific linear regressions showed significant interactions between MPAI-4 and EWBS for TBI-CareQOL measures of Caregiver-Specific Anxiety, Caregiver Strain and Feeling Trapped (p < .05; Table 5), but not for Feelings of Loss–Self. For PROMIS measures, MPAI-4 and EWBS interactions were significant for mood symptoms including, Anxiety, Depression, Fatigue, Anger, and Social Isolation, but not coping related measures, such as Emotional Support, Ability to Participate in SRA, or Satisfaction with SRA (see Table 5). For CAS domains, EWBS moderated the effect of MPAI-4 on Perceived Burden, the negative impact of caregiving, but not for measures of positive aspects of caregiving, Satisfaction, Ideology, or Mastery (see Table 5).

Figure 1.

Functional Impairment and Health Related Quality of Life in Caregivers. TBI-CareQOL = quality of life in caregivers of persons with traumatic brain injury; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; MPAI-4 = Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (4th ed.).

Table 5.

Linear Regression for MPAI-4 and Existential Well-Being

| HRQOL subdomain | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Specific Anxiety (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .95 | .16 | 3.92 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .11 | .18 | .63 | .53 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.44 | .003 | −1.76 | .08 |

| Caregiver Strain (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | 1.28 | .16 | 5.57 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .29 | .18 | 1.85 | .07 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.88 | .003 | −3.71 | <.001 |

| Feeling Trapped (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | 1.09 | .13 | 5.34 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .15 | .14 | 1.09 | .28 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.62 | .003 | −2.96 | .003 |

| Feelings of Loss (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .75 | .16 | 3.42 | <.001 |

| EWBS | − .21 | .17 | −1.4 | .16 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.31 | .003 | −1.41 | .16 |

| Anxiety (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .74 | .18 | 2.91 | .004 |

| EWBS | − .06 | .20 | −.34 | .74 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.51 | .004 | −1.99 | <.001 |

| Depression (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .73 | .16 | 3.07 | .002 |

| EWBS | −.11 | .17 | −.69 | .49 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.55 | .003 | −2.27 | .02 |

| Fatigue (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .89 | .18 | 3.64 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .09 | .20 | .54 | .59 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | − .63 | .003 | −2.50 | .01 |

| Anger (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .77 | .19 | 2.83 | .005 |

| EWBS | .00 | .21 | .02 | .99 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | − .60 | .004 | −2.16 | .03 |

| Ability to Participate in SRA (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.79 | .17 | −3.42 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .05 | .19 | .29 | .77 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .47 | .003 | 1.96 | .05 |

| Emotional Support (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .20 | .19 | .76 | .45 |

| EWBS | .63 | .21 | 3.39 | .001 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.49 | .004 | −1.79 | .07 |

| Satisfaction with SRA (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | − .43 | .17 | −1.70 | .09 |

| EWBS | .29 | .19 | 1.65 | .10 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .14 | .003 | .53 | .59 |

| Social Isolation (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .84 | .18 | 3.64 | <.001 |

| EWBS | − .06 | .19 | − .40 | .69 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | −.56 | .003 | −2.41 | .02 |

| Burden (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.97 | .20 | −4.80 | <.001 |

| EWBS | .02 | .22 | .13 | .90 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .55 | .004 | 2.65 | .01 |

| Satisfaction (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.34 | .12 | −1.22 | .22 |

| EWBS | .17 | .13 | .89 | .38 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .38 | .002 | 1.31 | .19 |

| Ideology (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.05 | .08 | −.18 | .86 |

| EWBS | −.09 | .09 | − .42 | .68 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .22 | .002 | .72 | .47 |

| Mastery (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.34 | .06 | −1.21 | .23 |

| EWBS | .23 | .06 | 1.18 | .24 |

| MPAI-4 × EWBS | .12 | .001 | .41 | .69 |

Note. Regressions are adjusted for military status of the person with traumatic brain injury (TBI), relationship to the person with TBI, caregiver gender, and caregiver race; TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury; HRQOL = health-related quality of life; PROMIS = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale; MPAI-4 = Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (4th ed.); EWBS = Existential Well-Being subscale; SRA = Social Roles and Activities.

Higher scores indicate better HRQOL.

For RWBS, although the number of significant relationships were limited (see Table 6) relative to EWBS interactions, greater functional impairment of the person with injury was again associated with less favorable caregiver HRQOL outcomes (TBI-CareQOL, PROMIS, CAS) with higher RWBS scores associated with a weaker effect of MPAI-4 on HRQOL outcomes. Specific linear regressions showed significant interactions between functioning and religious well-being for TBI-CareQOL Caregiver Strain, PROMIS Depression, and PROMIS Anger.

Table 6.

Linear Regression for MPAI-4 and Religious Well-Being

| HRQOL subdomain | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Specific Anxiety (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .87 | .13 | 4.45 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .21 | .14 | 1.05 | .29 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.39 | .002 | −1.55 | .12 |

| Caregiver Strain (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | 1.04 | .14 | 5.32 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .47 | .15 | 2.39 | .02 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.70 | .003 | −2.77 | .01 |

| Feeling Trapped (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .85 | .11 | 4.94 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .22 | .12 | 1.26 | .21 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.38 | .002 | −1.72 | .09 |

| Feelings of Loss (TBI-CareQOL) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .84 | .14 | 4.26 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .18 | .15 | .89 | .37 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.38 | .003 | −1.50 | .14 |

| Anxiety (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .73 | .16 | 3.34 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .27 | .17 | 1.25 | .21 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.51 | .003 | −1.81 | .07 |

| Depression (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .77 | .14 | 3.58 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .32 | .15 | 1.51 | .13 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.60 | .002 | −2.13 | .03 |

| Fatigue (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .71 | .15 | 3.41 | < 001 |

| RWBS | .31 | .16 | 1.49 | .14 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | − .43 | .003 | −1.59 | .11 |

| Anger (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .75 | .16 | 3.29 | .001 |

| RWBS | .32 | .17 | 1.41 | .16 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | − .61 | .003 | −2.07 | .04 |

| Ability to Participate in SRA (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | − .68 | .14 | −3.36 | <.001 |

| RWBS | − .21 | .16 | −1.06 | .29 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | .30 | .003 | 1.16 | .25 |

| Emotional Support (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .00 | .15 | .01 | .99 |

| RWBS | .46 | .17 | 2.08 | .04 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | − .48 | .003 | −1.66 | .10 |

| Satisfaction with SRA (PROMIS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | − .27 | .15 | −1.24 | .22 |

| RWBS | .20 | .16 | .89 | .38 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | −.18 | .003 | −.65 | .52 |

| Social Isolation (PROMIS) | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .72 | .16 | 3.43 | <.001 |

| RWBS | .20 | .17 | .98 | .33 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | − .41 | .00 | −1.52 | .13 |

| Burden (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.90 | .18 | −4.92 | <.001 |

| RWBS | −.30 | .19 | −1.64 | .10 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | .46 | .003 | 1.94 | .05 |

| Satisfaction (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.15 | .10 | − .63 | .53 |

| RWBS | .11 | .11 | .45 | .66 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | .09 | .003 | .28 | .78 |

| Ideology (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | .35 | .06 | 1.52 | .13 |

| RWBS | .41 | .07 | 1.74 | .08 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | − .27 | .001 | −.90 | .37 |

| Mastery (CAS)a | ||||

| MPAI-4 | −.50 | .05 | −2.13 | .03 |

| RWBS | − .20 | .05 | −.86 | .39 |

| MPAI-4 × RWBS | .26 | .001 | .84 | .40 |

Note. Regressions are adjusted for military status of the person with TBI, relationship to the person with TBI, caregiver gender, and caregiver race; TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury; HRQOL = health-related quality oflife; PROMIS = Patient- Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale; MPAI-4 = Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (4th ed.); RWBS = Religious Well-Being subscale; SRA = Social Roles and Activities.

Higher scores indicate better HRQOL.

For models with significant interactions between functioning and existential well-being, cut-points were identified to determine at which point MPAI-4 was no longer associated with adverse HRQOL after EWBS was taken into account (see Table 7). For example, when EWBS equaled 58 (i.e., excellent existential well-being), the association between MPAI-4 and PROMIS Depression became negligible. Thus, higher existential well-being reduced the impact of the care recipient’s functional impairment on caregiver’s anxiety. For TBI-CareQOL Caregiver Specific Anxiety, Caregiver Strain, Feeling Trapped, PROMIS Fatigue, Social Isolation, and CAS Perceived Burden, simple slopes analyses determined that MPAI-4 had negative effects on HRQOL regardless of EWBS or RWBS score, but this relationship was significantly weakened as spiritual well-being increased.

Table 7.

Existential and Religious Well-Being Cut-off Values

| Cut-off value (s) |

||

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | EWBS | RWBS |

| TBI-CareQOL | ||

| Caregiver Specific Anxiety | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | Association weakens but does not become insignificant |

| Caregiver Strain | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | |

| Feeling Trapped | Association weakens but does not become insignificant) | |

| PROMIS | ||

| Anxiety | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | Association weakens but does not become insignificant |

| Depression | Above 57 | |

| Fatigue | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | |

| Anger | Above 55 | Association weakens but does not become insignificant |

| Social Isolation | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | |

| CAS | ||

| Perceived Burden | Association weakens but does not become insignificant | |

Note. Cut-off values represent the existential or religious well-being score value where MPAI-4 is no longer associated with poorer HRQOL. TBI-CareQOL = Quality of Life in Caregivers of Persons with Traumatic Brain Injury; PROMIS = Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System; CAS = Caregiver Appraisal Scale; MPAI-4 = Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory (4th ed.); EWBS = Existential Well-Being subscale; RWBS = Religious Well-Being subscale; SRA = Social Roles and Activities.

Discussion

The findings of this study show that caregiving experiences are not universal across demographic and etiology of injury groups. The greatest emotional and psychological adjustment to caregiving was evident in caregivers who were spouses, men, and those involved with a military service person. Spouses in particular reported feeling more trapped in their situation and having greater burden than other types of caregivers (e.g., parents, friends). Caregivers identifying as White or Other race reported higher emotional distress than those who self-identified as Black. It is possible that extended family caregiving is more common within the Black community, and therefore the expectations and emotional reactions that they experience might be different than for those of other racial groups. As such, there might be cultural or demographic factors that rehabilitation professionals need to be aware of when working with diverse populations.

Caregivers of those who were injured in the military appear to have a very different emotional experience than civilian caregivers. Such individuals reported higher levels of anxiety, depression, fatigue, anger, and social isolation. They report lower levels of social support, as well as decreased ability to participate in and gain satisfaction from social activities. Overall, their reaction to caregiving appears to be one of emotional distress and social isolation, with the perception that they have very little emotional support from others. Paradoxically, although they experience more burden than civilian caregivers, they also report higher levels of satisfaction.

Functional impairment was associated with worse HRQOL for caregivers of those with TBI, but existential well-being was found to moderate this relationship. Specifically, the association between functional impairment and HRQOL was weakened when caregivers endorsed higher levels of existential well-being, and less so for religious well-being. These findings are important given the fact that spiritual well-being has been understudied in caregivers of persons with TBI. The empirical literature would indicate that spirituality is associated with better mental health and quality of life outcomes in caregivers of those with other medical conditions in a linear manner (e.g., the greater the spirituality, the better the HRQOL in the caregiver), but this study showed that this relationship is more complicated in TBI. In this study, the functional status of the person receiving care moderated the association between spiritual well-being and HRQOL. For CAS domains, EWBS moderated the effect of MPAI-4 on negative aspects of caregiving (Perceived Burden), but not for positive aspects of caregiving (Satisfaction, Ideology or Mastery).

One possible explanation for the study’s findings is that caregivers of those with severe TBI might lose hope for improvement over the years, as they are forced to accept that their loved one might not recover in the manner that they had hoped. They might be resigned to accept the unfortunate reality of a truncated recovery rather than a full recovery or much improved outcome. Caregivers of those with less severe TBI might still be struggling and hoping for improvements that might or might not be fully achieved. The two groups might live different realities and their adjustments could be quite different. This was not an empirical question that this study was designed to address, but rather is an interesting hypothesis for further exploration.

Strengths of this study include a large, diverse sample recruited from multiple sites and types of care settings that enhance generalizability of study findings. It should be noted that the sample was highly educated, thus limiting generalizability to those with lower education. Other limitations of the study include a lack of objective TBI severity data from the military sample. Additionally, the veteran sample included persons with mild TBI, and mild TBI typically results in good recovery and a lack of long-term sequelae. Surprisingly, the military caregivers in this sample reported more symptomatology than the civilian caregivers, and although differential effects were found for the caregiver groups and documented, some might think that combining the groups in the first place might be less than optimal. There are unique incentives in the veterans system for ensuring long-term health care, as well as additional comorbid factors that might account for worse psychological outcomes for the caregivers of this mild TBI group.

Consistent with most literature using spiritual well-being scales, the current Spiritual Well-Being Scale or otherwise, we did not ask participants about religious affiliation. Although considered a potential limitation, the current study was not designed to assess differential effects of religious affiliation or congregational membership on spiritual well-being (distinct from spirituality/religion) and HRQOL, and in fact, chose to use a spiritual well-being scale specifically designed to assess the concept of religion and not specifics of any one religion. The SWB scale instructions are consistent with this approach and allow the participant to use a higher being as a referent rather than a religiously defined construct of God. That said, a closer look at our participant’s responses to religious well-being items indicates that our participants ranged in their level of religious well-being and the current study was limited in the ability to capture the underlying nature of this range, either in religious affiliation, lack of affiliation, or other circumstance.

Rehabilitation professionals working with the support system of the person with TBI, might need to be aware of the moderating effect of function on caregiver outcome. For those friends and family members that have loved ones with more impairment, their spiritual beliefs and commitment might be more important to psychological function, perception about the caregiving role, and experience of stress, than their caregiving counterparts who have a loved one with less functional impairment. Such issues can be included as part of the formal rehabilitation treatment plan for the person with TBI’s whole support system and might involve nontraditional rehabilitation team members such as chaplains or spiritual guides.

Impact and Implications.

Spirituality as a coping mechanism has been proposed as a good predictor of outcomes in persons with TBI, but it has not been examined regarding caregiver outcomes. This study shows that the relationship between spirituality and health-related quality of life for caregivers of persons with TBI is more complicated than might be expected. Level of impairment in the person with brain injury has a moderating effect for spirituality and health-related quality of life in caregivers, such that caregivers of those with more impairment might rely more on spirituality for better quality of life. Knowledge of this effect can be helpful to caregivers as they plan for their own needs and self-care during the recovery process of their loved ones with TBI.

Acknowledgments

Work on this article was supported by Grant R01NR013658 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute of Nursing Research. Funding from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000433) provided support for data collection. This research is sponsored by Veterans Health Administration Central Office Veterans Affairs TBI Model System Program of Research, and Subcontract from General Dynamics Health Solutions (W91YTZ-13-C-0015) from the Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center within the Defense Health Agency. We thank the investigators and research associates/coordinators who worked on the study, the study participants, and organizations who supported recruitment efforts. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies.

Footnotes

TBI-CareQOL Site Investigators and Coordinators are as follows: Noelle E. Carlozzi, Anna Kratz, Amy Austin, Jenna Russell, Jenna Freedman, Jennifer Miner (University of Michigan); Angelle Sander (Baylor College of Medicine and TIRR Memorial Hermann, Houston, Texas), Curtisa Light (TIRR Memorial Hermann, Houston, Texas); Robin A. Hanks, Daniela Ristova-Trendov (Wayne State University/Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan); Tracey Brickell, Rael Lange, Louis French, Sara Lippa, Rachel Gartner, Megan Wright, Angela Driscoll, Diana Nora, Jamie Sullivan, Nicole Varbedian, Lauren Johnson, Heidi Mahatan, Paula Bellini, Jayne Holzinger, Jennifer Freud, Ashley Schaper, Maryetta Reese, Elizabeth Barnhart, Vanessa Ndege, Yasmine Eshera, Jenna Weintraub, Mary Andrews, Kaitlyn Casey, Gabrielle Robinson (Walter Reed National Military Medical Center/Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center, Bethesda, Maryland); Jill Massengale, Risa Richardson, Leah Drasher-Phillips, Kristina Martinez, Padmaja Ramaiah (James A. Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, Florida).

The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this article are those of the authors and should not be construed as an official Department of Veterans Affairs position or any other federal agency, policy, or decision unless so designated by other official documentation.

Contributor Information

Robin A. Hanks, Wayne State University School of Medicine and Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan

Nicholas R. Boileau, University of Michigan

Andria L. Norman, Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan

Risa Nakase-Richardson, James A. Haley Veterans Hospital, Tampa, Florida, and University of South Florida.

Kyr Hudson Mariouw, Rehabilitation Institute of Michigan, Detroit, Michigan.

Noelle E. Carlozzi, University of Michigan

References

- Aiken LS, & West S (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Arango-Lasprilla JC, Nicholls E, Villaseñor Cabrera T, Drew A, Jimenez-Maldonado M, & Martinez-Cortes ML (2011). Health-related quality of life in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury from Guadalajara, Mexico. Journal of Rehabilitation Medicine, 43, 983–986. 10.2340/16501977-0883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayen E, Pradat-Diehl P, Jourdan C, Ghout I, Bosserelle V, Azerad S, … the Steering Committee of the PariS-TBI study. (2013). Predictors of informal care burden 1 year after a severe traumatic brain injury: Results from the Paris-TBI study. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 28, 408–418. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e31825413cf [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300. 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks N, Campsie L, Symington C, Beattie A, & McKinlay W (1986). The five-year outcome of severe blunt head injury: A relative’s view. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry, 49, 764–770. 10.1136/jnnp.49.7.764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell JD, Yoon DP, & Johnstone B (2010). Determining relationships between physical health and spiritual experience, religious practices, and congregational support in a heterogeneous medical sample. Journal of Religion and Health, 49, 3–17. 10.1007/s10943-008-9227-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Hanks R, Lange RT, Brickell TA, Ianni PA, Miner JA, … Sander AM (2019). Understanding health-related quality of life in caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with traumatic brain injury: Establishing the reliability and validity of PROMIS mental health measures. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S94–S101. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Ianni PA, Lange RT, Brickell TA, Kallen MA, Hahn EA, … Tulsky DS (2019). Understanding health-related quality of life of caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with traumatic brain injury: Establishing the reliability and validity of PROMIS social health measures. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S110–S118. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Ianni PA, Tulsky DS, Brickell TA, Lange RT, French LM, … Kratz AL (2019). Understanding health-related quality of life in caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with traumatic brain injury: Establishing the reliability and validity of PROMIS fatigue and sleep disturbance item banks. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S102–S109. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Hanks R, Hahn EA, Brickell T, Lange R, … Sander AM (2019). The TBI-CareQOL Measurement System: Development and preliminary validation of health-related quality of life measures for caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with traumatic brain injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.08.175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Hanks R, Kratz AL, Hahn E, Brickell TA, … Sander AM (2019). The development of a new computer adaptive test to evaluate feelings of being trapped in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: TBI-CareQOL Feeling Trapped Item Bank. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S43–S51. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.06.025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Ianni PA, Sander AM, Hahn EA, Lange RT, … Hanks R (2019). The development of a two new computer adaptive tests to evaluate feelings of loss in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: TBI-CareQOL Feelings of Loss–Self and Feelings of Loss–Person with Traumatic Brain Injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S31–S42. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Kallen MA, Sander AM, Brickell TA, Lange RT, French LM, … Hanks R (2019). The development of a new computer adaptive test to evaluate anxiety in caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury: TBI-CareQOL Caregiver–Specific Anxiety. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 100(4S), S22–S30. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlozzi NE, Lange RT, French LM, Sander AM, Ianni PA, Tulsky DS, … Brickell TA (2019). Understanding health-related quality of life in caregivers of civilians and service members/veterans with TBI: Reliability and validity data for the TBI-CareQOL Measurement System. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Advance online publication. 10.1016/j.apmr.2018.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, … the PROMIS Cooperative Group. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63, 1179–1194. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chronister J, & Chan F (2006). A stress process model of caregiving for individuals with traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 51, 190–201. 10.1037/0090-5550.51.3.190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chronister J, Chan F, Sasson-Gelman EJ, & Chiu CY (2010). The association of stress-coping variables to quality of life among caregivers of individuals with traumatic brain injury. NeuroRehabilitation, 27, 49–62. 10.3233/NRE-2010-0580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Bogner JA, Mysiw WJ, Clinchot D, & Fugate L (2001). Life satisfaction after traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 16, 543–555. 10.1097/00001199-200112000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan JD, Cuthbert JP, Whiteneck GG, Dijkers MP, Coronado V, Heinemann AW, … Graham JE (2012). Representativeness of the Traumatic Brain Injury Model Systems National Database. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 27, 391–403. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3182238cdd [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis LC, Sander AM, Struchen MA, Sherer M, Nakase-Richardson R, & Malec JF (2009). Medical and psychosocial predictors of caregiver distress and perceived burden following traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 24, 145–154. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e3181a0b291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson D, Park CL, Blank TO, Fenster JR, & Mills MA (2008). Deconstructing spiritual well-being: Existential well-being and HRQOL in cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 17, 161–169. 10.1002/pon.1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CW (1983). Spiritual well-being: Conceptualization and measurement. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 11, 330–338. 10.1177/009164718301100406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ellison CG, & George LK (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33, 46–61. 10.2307/1386636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis N, Rosenbloom BN, Canzian S, & Topolovec-Vranic J (2013). Depression and anxiety in parent versus spouse caregivers of adult patients with traumatic brain injury: A systematic review. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 23, 1–18. 10.1080/09602011.2012.712871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergh TC, Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, & Coleman RD (2003). Social support moderates caregiver life satisfaction following traumatic brain injury. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25, 1090–1101. 10.1076/jcen.25.8.1090.16735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ergh TC, Rapport LJ, Coleman RD, & Hanks RA (2002). Predictors of caregiver and family functioning following traumatic brain injury: Social support moderates caregiver distress. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17, 155–174. 10.1097/00001199-200204000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul M, Xu L, Wald M, & Coronado V (2010). Traumatic brain injury in the United States: Emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and deaths. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 10.15620/cdc.5571 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gulin SL, Perrin PB, Stevens LF, Villaseñor-Cabrera TJ, Jiménez-Maldonado M, Martínez-Cortes ML, & Arango-Lasprilla JC (2014). Health-related quality of life and mental health outcomes in Mexican TBI caregivers. Families, Systems & Health, 32, 53–66. 10.1037/a0032623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanauer DA, Mei Q, Law J, Khanna R, & Zheng K (2015). Supporting information retrieval from electronic health records: A report of University of Michigan’s nine-year experience in developing and using the Electronic Medical Record Search Engine (EMERSE). Journal of Biomedical Informatics, 55, 290–300. 10.1016/j.jbi.2015.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, & Vangel S (2007). Caregiving appraisal after traumatic brain injury: The effects of functional status, coping style, social support and family functioning. NeuroRehabilitation, 22, 43–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanks RA, Rapport LJ, Wertheimer J, & Koviak C (2012). Randomized controlled trial of peer mentoring for individuals with traumatic brain injury and their significant others. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 93, 1297–1304. 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Moser D, Tateno A, Crespo-Facorro B, & Arndt S (2004). Major depression following traumatic brain injury. Archives of General Psychiatry, 61, 42–50. 10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick SD, & McCullough ME (1999). Religion and spirituality in rehabilitation psychology. Rehabilitation Psychology, 44, 388–402. 10.1037/0090-5550.44.4.388 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Knight RG, Devereux R, & Godfrey HP (1998). Caring for a family member with a traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12, 467–481. 10.1080/026990598122430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG (2013). Religion and spirituality in coping with acute and chronic illness. In Pargament KI, Mahoney A, & Shafranske EP (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol. 2): An applied psychology of religion and spirituality (p. 275–295). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 10.1037/14046-014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen S (1998). Quality of life 10 years after a very severe traumatic brain injury (TBI): The perspective of the injured and the closest relative. Brain Injury, 12, 631–648. 10.1080/026990598122205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratz AL, Sander AM, Brickell TA, Lange RT, & Carlozzi NE (2017). Traumatic brain injury caregivers: A qualitative analysis of spouse and parent perspectives on quality of life. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27, 16–37. 10.1080/09602011.2015.1051056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutzer JS, Rapport LJ, Marwitz JH, Harrison-Felix C, Hart T, Glenn M, & Hammond F (2009). Caregivers’ well-being after traumatic brain injury: A multicenter prospective investigation. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 90, 939–946. 10.1016/j.apmr.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, & Folkman S (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Malec J (2005). The Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory. Retrieved from http://www.tbims.org/combi/mpai [DOI] [PubMed]

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, & Sleigh JW (1998a). Caregiver burden at 6 months following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12, 225–238. 10.1080/026990598122700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh NV, Kersel DA, Havill JH, & Sleigh JW (1998b). Caregiver burden at 1 year following severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Injury, 12, 1045–1059. 10.1080/026990598121954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson KM, Pentland B, & McNaughton HK (2000). Brain injury—The perceived health of carers. Disability and Rehabilitation, 22, 683–689. 10.1080/096382800445489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanda U, & Andresen EM (1998). Health-related quality of life. A guide for the health professional. Evaluation & the Health Professions, 21, 179–215. 10.1177/016327879802100204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale MC (2003). Religion, spirituality, and ethnicity: What it means for caregivers of persons with Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Dementia, 2, 379–391. 10.1177/14713012030023006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norup A, Kristensen KS, Siert L, Poulsen I, & Mortensen EL (2011). Neuropsychological support to relatives of patients with severe traumatic brain injury in the sub-acute phase. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 21, 306–321. 10.1080/09602011.2011.558766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norup A, Siert L, & Lykke Mortensen E (2010). Emotional distress and quality of life in relatives of patients with severe brain injury: The first month after injury. Brain Injury, 24, 81–88. 10.3109/02699050903508200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norup A, Snipes DJ, Siert L, Mortensen EL, Perrin PB, & Arango-Lasprilla JC (2013). Longitudinal trajectories of health-related quality of life in Danish family members of individuals with severe brain injury. Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, 19, 71–83. 10.1017/jrc.2013.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Norup A, Welling KL, Qvist J, Siert L, & Mortensen EL (2012). Depression, anxiety and quality-of-life among relatives of patients with severe brain injury: The acute phase. Brain Injury, 26, 1192–1200. 10.3109/02699052.2012.672790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paloutzian RF, & Ellison CW (1982). Loneliness, spiritual well-being and quality of life In Peplau LA & Perlman D (Eds.), Loneliness: A sourcebook of current theory, research, and therapy (pp. 224–237). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Riley BB, Perna R, Tate DG, Forchheimer M, Anderson C, & Luera G (1998). Types of spiritual well-being among persons with chronic illness: Their relation to various forms of quality of life. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, 79, 258–264. 10.1016/S0003-9993(98)90004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Balzer K, Harris J, & Moldovan R (2007). A qualitative needs assessment of persons who have experienced traumatic brain injury and their primary family caregivers. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 22, 14–25. 10.1097/00001199-200701000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. (2013). SAS 9.4 language reference concepts Cary, NC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Shah AA, Snow AL, & Kunik ME (2002). Spiritual and religious coping in caregivers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clinical Gerontologist, 24, 127–136. 10.1300/J018v24n03_11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva J, Ownsworth T, Shields C, & Fleming J (2011). Enhanced appreciation of life following acquired brain injury: Posttraumatic growth at 6 months postdischarge. Brain Impairment, 12, 93–104. 10.1375/brim.12.2.93 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soo C, & Tate R (2007). Psychological treatment for anxiety in people with traumatic brain injury. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3, CD005239 10.1002/14651858.CD005239.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Struchen MA, Atchison TB, Roebuck TM, Caroselli JS, & Sander AM (2002). A multidimensional measure of caregiving appraisal: Validation of the Caregiver Appraisal Scale in traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 17, 132–154. 10.1097/00001199-200204000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tate RL, & Broe GA (1999). Psychosocial adjustment after traumatic brain injury: What are the important variables? Psychological Medicine, 29, 713–725. 10.1017/S0033291799008466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B, Fleming J, Parry J, Vromans M, Cornwell P, Gordon C, & Ownsworth T (2010). Caregivers of adults with traumatic brain injury: The emotional impact of transition from hospital to home. Brain Impairment, 11, 281–292. 10.1375/brim.11.3.281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vangel SJ Jr., Rapport LJ, & Hanks RA (2011). Effects of family and caregiver psychosocial functioning on outcomes in persons with traumatic brain injury. The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation, 26, 20–29. 10.1097/HTR.0b013e318204a70d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldron-Perrine B, Rapport LJ, Hanks RA, Lumley M, Meachen S-J, & Hubbarth P (2011). Religion and spirituality in rehabilitation outcomes among individuals with traumatic brain injury. Rehabilitation Psychology, 56, 107–116. 10.1037/a0023552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]