Lung histological analyses revealed the presence of vascular inflammation and severe endothelial injury as a direct consequence of intracellular severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection and ensuing host inflammatory response in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).1 Endothelial cells promote coagulation following injury, leading to widespread formation of microthrombi, provoking microcirculatory failure or large-vessel thrombosis.2 Growing evidence suggests that microvascular thrombosis is a major pathophysiological event in COVID-19 pathogenesis. Damaged endothelial cells could be closely implicated in the prothrombotic state commonly reported in severe patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). How SARS-CoV-2 exerts its cytopathic effects is still a matter of debate, and ultrastructural evidence of direct viral replication in endothelial cells remains to be demonstrated. Although direct viral tissue damage is a plausible mechanism of injury,3 endothelial damage and thromboinflammation associated with dysregulated immune responses, inducing microvascular thrombosis, represent an attractive alternative hypothesis.2 Using cultured human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells (HPMVEC), we assessed whether plasma collected from patients with COVID-19 at different disease stages could trigger endothelial damage in vitro. The cytotoxicity of plasma samples on HPMVEC was evaluated by assessing mitochondrial activity (WST-1 test) 1 hour after incubation of cells with plasma as previously described.4 We further investigated the association of plasma-induced cytotoxicity with levels of circulating biomarkers related to organ dysfunction (Pao2 [partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood]/Fio2 [fraction of inspired oxygen], widely used as an indicator of oxygenation requirements, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, and aspartate transaminase), endothelial damage (von Willebrand factor antigen; ADAMTS13; plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; syndecan-1), tissue injury (cell-free DNA, a damage-associated molecular patterns marker), and levels of circulating cytokines related to the activation of innate (interleukin [IL]–6 and tumor necrosis factor–α) and adaptative immune cell responses (soluble IL-2 receptor). Inclusion criteria were individuals aged 18 years or older with a positive SARS-CoV-2 real-time reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on nasal or tracheal samples admitted to the Lille University Hospital. Patients on treatment with direct oral anticoagulant or vitamin K antagonists were switched to therapeutic heparin therapy on admission. Patients not in the ICU received once daily thromboprophylaxis with enoxaparin according to their body weight. Patients in the ICU received enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin according to their renal status, their body weight, and the need for invasive procedures. This study was approved by the French institutional authority for personal data protection (Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertés No. DEC20-086) and the ethics committee (IRB 2020-A00763-36), and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

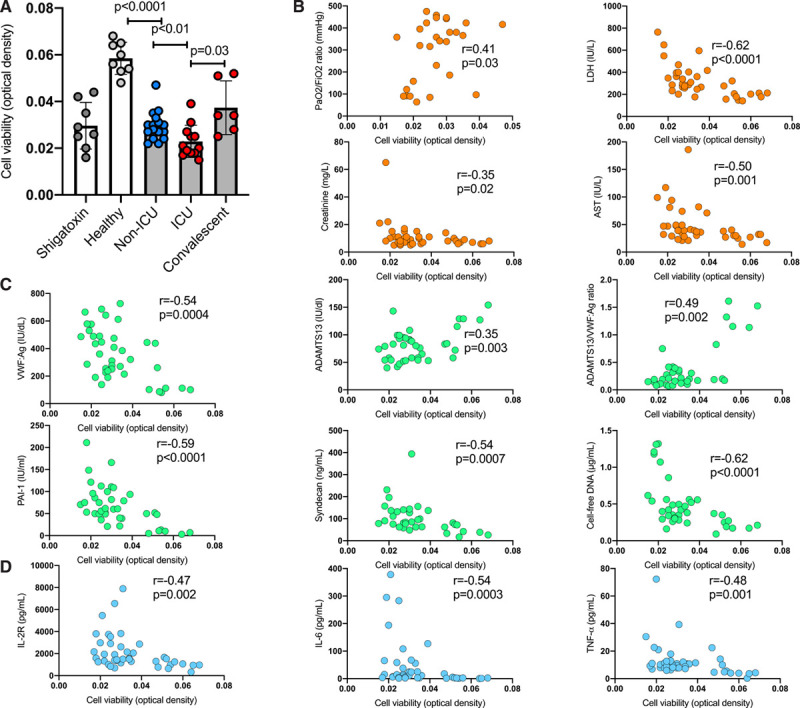

HPMVEC viability was assessed after coincubation with plasma sampled on admission from 28 consecutive patients (non-ICU, n=16; ICU, n=12) hospitalized for COVID-19 at the Lille University Hospital between March 30, 2020, and April 8, 2020, in convalescent patients with COVID-19 (n=6 from the 12 patients in the ICU) sampled after ICU discharge (mean±SD, 21±7 days) and in control healthy donors (n=8). Compared with healthy donor plasma, plasma from patients with COVID-19 significantly decreased HPMVEC viability, with plasma from patients in the ICU inducing the greatest cytotoxicity (Figure [A]). It is interesting that HPMVEC viability was partially restored to control when plasma from convalescent patients after ICU discharge was tested and compared with plasma of the same patients at the time of ICU admission. Moreover, markers of organ dysfunction were correlated with plasma-induced cytotoxicity (Figure [B]). HPMVEC viability also correlated with most plasma markers related to endothelial damage or tissue injury (Figure [C]). Soluble IL-2 receptor and tumor necrosis factor–α levels negatively correlated with HPMVEC viability (Figure [D]). Overall, the degree of vascular endothelial cell injury induced by plasma sampled from patients with COVID-19 correlated to both clinical illness severity at admission and the levels of biomarkers related to endothelial injury, tissue injury, and proinflammatory cytokines.

Figure.

Endothelial cell cytotoxicity induced by plasma sampled from critically ill and convalescent patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The cytotoxicity of platelet-poor plasma samples (obtained after a double centrifugation of citrate tubes at 2500 g for 15 minutes at room temperature) from patients with COVID-19 and controls on HPMVEC was evaluated with a colorimetric assay using 4-[3-(4-iodophenyl)-2-(4-nitrophenyl)-2H-5-tetrazolio]-1.3-benzene disulfonate (WST-1), which in viable cells is cleaved by mitochondrial dehydrogenases. After incubation, the cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline and incubated with WST-1 (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) at a dilution of 1:10 (10 µL) for 2 h at 37°C. Absorbance was measured using a multiwell plate reader (Synergy HTX multi-mode plate reader, BioTek Instruments, Highland Park, VT) at 450 nm with a reference wavelength of 620 nm. As a positive control for endothelial cell injury, Shigatoxin 145 (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Quentin Fallavier, France) was spiked in plasma from healthy adults (10 µg/mL final concentration) and incubated at 37°C for 15 minutes, before addition to HPMVECs. Experiments were performed in triplicate for each patient sample. A, HPMVEC viability after exposure to plasma sampled in healthy subjects (n=8), in non-ICU (n=16), and in ICU (n=12) on admission and in 6 convalescent patients with COVID-19 sampled after ICU discharge (mean±SD, 21±7 days). Data points represent individual sample measurements, whereas horizontal bars show the mean (±SD). Comparisons between groups were done using the Mann-Whitney U test, except for comparison between ICU and convalescent patients, where we used Wilcoxon signed-rank test on matched pairs (n=6). Correlations between HPMVEC viability and (B) markers of organ dysfunction: the Pao2/FiO2 ratio, widely used as an indicator of oxygenation requirements, LDH, creatinine and AST; (C) parameters related to endothelial dysfunction and tissue injury: VWF:Ag, ADAMTS13, ADAMTS13:VWF ratio, PAI-1, syndecan-1, and cell-free DNA; and (D) plasma cytokine concentrations: IL-2R, IL-6. and TNF-α. Correlations were evaluated with the Spearman rank-correlation statistical test. No adjustment for multiple comparisons was done, and the result should be interpreted as hypothesis-generating. AST indicates aspartate transaminase; HPMVEC, human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells; ICU, intensive care unit; IL, interleukin; IL-2R, soluble IL-2 receptor; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1; TNF–α, tumor necrosis factor–α; and VWF:Ag, von Willebrand factor antigen.

Our data shed new light on the pathophysiology of COVID-19 by demonstrating the direct and rapid cytotoxic effect of plasma collected from critically ill patients on vascular endothelial cells. This rapid effect (1 hour after plasma exposure) excludes a direct cytopathic effect of SARS-CoV-2 infection, as the progression of viral infection and visible cytopathogenic effects are in general only apparent 12 to 24 hours after infection.5 A higher cytotoxic effect of plasma on endothelial cells was associated with a more pronounced hypoxemia and organ dysfunction as reflected by the correlation with Pao2/FiO2, lactate dehydrogenase, creatinine, and aspartate transaminase. This cytotoxic effect also correlated with circulating markers of endothelial damage, indicating that this in vitro functional assay reflects microvascular endothelial damage in vivo. Different pathways could be involved in endothelial cell injury during the course of COVID-19, ie, complement activation, cellular hypoxia, platelets, and direct cytotoxicity of cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor–α. We observed a relationship between this cytotoxic effect and the level of proinflammatory cytokines, suggesting that cytotoxicity could be related to overproduction of proinflammatory cytokines. However, this article does not provide the supportive evidence of convalescent plasma for treating severe patients with COVID-19.

In conclusion, we provide for the first time the results of a functional assay demonstrating a direct effect of dysregulation of immune response on endothelial damage in COVID-19. Endotheliopathy is an essential part of the pathological response on severe COVID-19, leading to respiratory failure, multiorgan dysfunction, and thrombosis. Endothelial and microvascular damage are associated with immunopathology and may occur in parallel with intracellular SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all physicians and medical staff involved in patient care. Special thanks are addressed to Eric Boulleaux, Laureline Bourgeois, Aurélie Jospin, Catherine Marichez, Vincent Dalibard, Bénédicte Pradines, Sandrine Vanderziepe, and all the biologists and technicians of the Hemostasis Department for their support during the COVID-19 pandemic. A.R. and A. Dupont collected clinical data, analyzed the data, and wrote the article. J.G., M.C., S. Staessens, M.D.M., E.J., D.C., G.L., F.L., K.F., M.L., D.G., S.D.M., and J.P. collected data. J.G., M.C., S. Staessens, E.J., and S.D.M. analyzed the data. J.L. and A. Duhamel performed the statistical analysis. B.S., E.V., F.V., J.P., E.K., and P.L. provided critical input in the interpretation of data and critically reviewed the article. S. Susen designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote, and critically reviewed the article. All authors provided editorial review and assisted in writing the article.

Sources of Funding

This study was supported by the French government through the Program Investissement d’Avenir (I-SITE ULNE/ANR-16-IDEX-0004 ULNE).

Disclosures

None.

Appendix

Members of the LICORNE Scientific Committee:

Dominique Deplanque (Clinical Investigation Center, CHU Lille, France) Karine Faure (Department of Infectious Diseases, CHU Lille, France) Guillaume Lefevre (Department of Immunology, CHU Lille, France) Enagnon Kazali Alidjinou (Department of Virology, CHU Lille, France) Régis Bordet (Department of Medical Pharmacology, CHU Lille, France) Marie-Charlotte Chopin (Department of Infectious Diseases, CHU Lille, France) Ilka Engelmann (Department of Virology, CHU Lille, France) Delphine Garrigue (Department of Emergency, CHU Lille, France) Anne Goffard (Department of Virology, CHU Lille, France) Eric Kipnis (Department of Anesthesia and Critical Care, CHU Lille, France) Myriam Labalette (Department of Immunology, CHU Lille, France) Marc Lambert (Department of Internal Medicine, CHU Lille, France) David Launay (Department of Internal Medicine, CHU Lille, France) Daniel Mathieu (Department of Intensive Care, CHU Lille, France) Claude-Alain Maurage (Department of Anatomopathology, CHU Lille, France) Julien Poissy (Department of Intensive Care, CHU Lille, France) Boualem Sendid (Department of Parasitology, CHU Lille, France) Sophie Susen (Department of Hematology, CHU Lille, France)

Footnotes

Drs Rauch and Dupont contributed equally.

A list of all members of the LICORNE scientific committee is given in the Appendix.

Data sharing: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Registration: URL: https://www.clinicaltrials.gov; Unique identifier: NCT-04327180.

Contributor Information

Antoine Rauch, Email: antoine.rauch@chru-lille.fr.

Annabelle Dupont, Email: annabelle.dupont@univ-lille.fr.

References

- 1.Ackermann M, Verleden SE, Kuehnel M, Haverich A, Welte T, Laenger F, Vanstapel A, Werlein C, Stark H, Tzankov A, et al. Pulmonary vascular endothelialitis, thrombosis, and angiogenesis in Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:120–128. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2015432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gupta A, Madhavan MV, Sehgal K, Nair N, Mahajan S, Sehrawat TS, Bikdeli B, Ahluwalia N, Ausiello JC, Wan EY, et al. Extrapulmonary manifestations of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;26:1017–1032. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0968-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Puelles VG, Lütgehetmann M, Lindenmeyer MT, Sperhake JP, Wong MN, Allweiss L, Chilla S, Heinemann A, Wanner N, Liu S, et al. Multiorgan and renal tropism of SARS-CoV-2. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:590–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2011400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gavriilaki E, Yuan X, Ye Z, Ambinder AJ, Shanbhag SP, Streiff MB, Kickler TS, Moliterno AR, Sperati CJ, Brodsky RA. Modified Ham test for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2015;125:3637–3646. doi: 10.1182/blood-2015-02-629683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bojkova D, Klann K, Koch B, Widera M, Krause D, Ciesek S, Cinatl J, Münch C. Proteomics of SARS-CoV-2-infected host cells reveals therapy targets. Nature. 2020;583:469–472. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2332-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]