Abstract

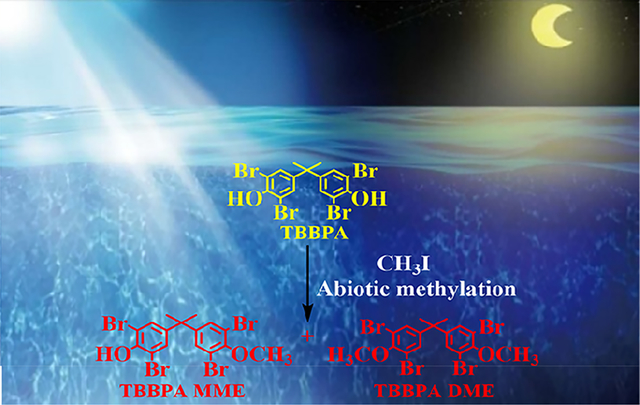

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) is the most widely used brominated flame retardant in the world. Its biotic methylation products, tetrabromobisphenol A mono- and dimethyl ether (TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME, respectively), are frequently detected in the environment, but the importance of abiotic methylation reactions of TBBPA in the environment is not known. In this study, the methylation of TBBPA mediated by methyl iodide (CH3I), a ubiquitous compound in aqueous environments, was investigated in simulated waters in the laboratory. It was found that abiotic methylation occurred under both light and dark conditions and was strongly affected by the pH, temperature, and natural organic matter concentration of the water. Abiotic methylation was further verified in natural river water, and the yield of TBBPA MME mediated abiotically by CH3I was much greater than that of biotic methylation. According to our calculations and by comparison of the activation energies (Ea) for the abiotic methylation of TBBPA and the other four typical phenolic contaminants and/or metabolites (bisphenol A, triclosan, 5-OH-BDE-47, and 4′-OH-CB-61) mediated by CH3I, those phenolic compounds all show great methylation potentials. The results indicate a new abiotic pathway for generating TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME from TBBPA, and they also confirm the potentials for abiotic methylation of other phenolic contaminants in aqueous environments.

Graphical Abstract

1. INTRODUCTION

Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA), a widely used flame retardant (FR) in industrial products, has become a ubiquitous organic contaminant in the environment.1,2 The concentrations of TBBPA have reached microgram per liter and microgram per gram levels in some waters3–6 and sediments5–8 sampled in China, Europe, and the United States, leading to contamination of aquatic organisms,8–10 and TBBPA was finally taken up by animals and humans through the food chain. The increasing level of contamination of the environment by TBBPA has led to a continual increase in its concentration in Chinese breast milk.11 Thus, the fate of TBBPA in the environment is of major concern.

TBBPA can be metabolized by bacteria and plants to form less brominated bisphenol A (BPA), bromophenols, and conjugated and methylated products.12–16 The methylation products, TBBPA mono- and dimethyl ether (TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME, respectively), are frequently detected in various environmental media.17–19 They are less toxic but more persistent and bioaccumulative than the parent compound1,17–20 and are considered as a potential secondary source of TBBPA because of the biotic interconversion between methylated TBBPA and TBBPA.15 Transformation pathways of TBBPA in many organisms have been elucidated. However, its abiotic degradation was studied only in very limited works under photo- and nanomaterial catalysis.21–24 To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study of the strictly chemical methylation of TBBPA, which helps to explain the environmental occurrence of TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME.

CH3I is a good methyl group donor. It is able to methylate many metals, metalloids in the environment, and organic compounds in chemical synthesis through abiotic pathways.25–29 CH3I can be naturally formed by algae, fungi, and higher plants (paddy rice, wheat, and daikon radish) and exists in the air, oceans, freshwater, and terrestrial ecosystems.30–34 In addition, CH3I is widely used as an agricultural soil fumigant and released to freshwater through runoff, causing high concentrations in aqueous environments. After CH3I is applied to a soil column in laboratory-simulated experiment, the early leaching concentrations of CH3I can exceed 10 μg L−1.35 CH3I has become one of the most ubiquitous contaminants in the environment.36

In this work, the abiotic methylation of TBBPA in the aquatic environment was studied in the reaction with CH3I. The results show that TBBPA can be methylated by CH3I in both laboratory-simulated water and natural river water under light and dark conditions. The generation curve for TBBPA MME after reaction between TBBPA and CH3I was calculated and evaluated under different pH conditions. It was demonstrated that, in addition to the biotic methylation, the abiotic methylation of TBBPA is also an important pathway for the formation of TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME in the environment. The abiotic methylation potentials of TBBPA and four other common phenolic compounds were also compared. This research further improves our understanding of the reactions and reactivity of TBBPA in the environment.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents.

TBBPA (0.25 g, 99.0%) and the internal standard of d10-TBBPA (100 μg mL−1 in acetonitrile, 98.5%) were obtained from Dr. Ehrenstorfer GmbH (Augsburg, Germany). TBBPA DME (50 μg mL−1 in nonane, ≥98%), surrogate standards of [13C12]TBBPA (50 μg mL−1 in methanol, 99%), and [13C12]TBBPA DME (100 μg mL−1 in toluene, 99%) were all purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. (Andover, MA). Methyl iodide (CH3I, ≥98%), monopotassium phosphate (KH2PO4, ≥99%), dipotassium phosphate (K2HPO4, ≥99%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH, ≥96%), and sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 95–98%) were all obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Natural organic matter (NOM) from Suwannee River was bought from the International Humic Substance Society (Denver, CO). All solvents used in the study were of chromatographic grade and obtained from J. T. Baker (Philipsburg, NJ).

The working solutions of TBBPA and CH3I used for methylation reaction were set at concentrations of 1 mmol L−1 and 1 mol L−1 in methanol, respectively. The working solution of CH3I was prepared just prior to use. Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ cm−1) was produced by a Milli-Q (Billerica, MA) advantage A10 system. Natural river water (pH 6.8) without detectable TBBPA and its methylation products was sampled from the Qinghe River, Beijing, China, and stored at 4 °C before use.

2.2. Experimental Design.

2.2.1. Methylation of TBBPA in Laboratory-Simulated Water.

Laboratory-simulated water was prepared using sterilized deionized water augmented with buffer salts (KH2PO4 and K2HPO4, final concentrations of 10 mmol L−1) and NaOH/H2SO4 to adjust the pH values to 1.0, 4.0, 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 11.0, and 13.0 for the experiments. One hundred milliliters of laboratory-simulated water was added to working solutions of both TBBPA and CH3I to achieve initial concentrations of 200 nmol L−1 and 1 mmol L−1, respectively, which were higher than their concentrations commonly found in contaminated water bodies for the detection and exploration of the transformation products and mechanism conveniently. They were poured into a 120 mL transparent quartz bottle to act as the reaction system. Control groups, consisting of only individual CH3I (I control) or TBBPA (T control), were added to the water at the same time. The reaction under light conditions was carried out in a chamber using xenon lamps to simulate the solar illuminance with an intensity of 550 W m−2. The reaction under dark conditions was performed by wrapping the bottles with aluminum foil. Due to the fast photolysis of TBBPA and CH3I,23,37 the light experiment lasted for only 180 min, but the reaction under dark conditions lasted as long as 30 days.

For the reactions in light at pH 7.0 (mimicking a natural water system), the methylation reaction was stopped at 5, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, and 180 min and the solutions were sampled to study the time course of the abiotic methylation. For the reactions in the dark at pH 7.0, in addition to the same sampling time points as the illuminance reaction experiment, we added samples at 1, 5, 10, 15, 21, and 30 days. To better understand the effect of acidity on the reaction between TBBPA and CH3I, additional pH values, including 1.0, 4.0, 6.0, 6.5, 7.5, 8.0, 8.5, 11.0, and 13.0, were chosen for dark experiments and sampled at 1, 5, 10, 15, 21, and 30 days. All reactions were conducted at 25 °C without NOM.

Effects of temperature and NOM on the abiotic methylation were also considered. Different temperatures (4, 15, 25, and 35 °C) and contents of NOM (1, 10, and 20 mg L−1) were investigated and compared at pH 7.0, and the reaction and control groups were sampled at 180 min for both light and dark experiments. The solutions of all of the reaction (treatment) and control groups were conducted in triplicate.

2.2.2. Methylation of TBBPA in River Water.

Methylation of TBBPA mediated by CH3I was further studied using nonsterilized (NS) and sterilized (S) river water to verify the occurrence of abiotic methylation in the environment and quantitatively define the contributions of biotic and abiotic methylations. The performance and the initial concentrations of TBBPA and CH3I in the reaction groups were set up in the same way as the laboratory-simulated water experiments. Both TBBPA and CH3I were added together to the sterilized or nonsterilized river water (T&I-S group and T&I-NS group). The control groups consisted of only one reactant; that is, only TBBPA or CH3I was added to the sterilized or nonsterilized river water (T-S, T-NS, I-S, and I-NS controls) under light and dark conditions. The temperature, pH, and NOM adjustments were not performed for the natural river water, and there was only one time point for the light and dark experiments. The solutions of reaction and control groups were sampled at 180 min for the light experiment and at 15 days for the dark experiment.

2.3. Sample Pretreatment.

Solutions of the reaction and control groups were extracted immediately after sampling. A 2 mL volume of a H2SO4 solution (4.9 mol L−1) was used to adjust the pH of the reaction solutions (100 mL). One milliliter of a solution sample was added with 10 ng of [13C12]TBBPA as a surrogate standard and extracted three times with 200 μL of dichloromethane. The combined extract was solvent exchanged with 1 mL of methanol under a gentle nitrogen flow and then added with 10 ng of d10-TBBPA to analyze TBBPA by LC-MS/MS. An additional 1.5 mL of the solution sample was extracted with 300 μL of hexane once for CH3I analysis by GC-MS/MS. The remaining 97.5 mL of the solution sample was added with 10 ng of [13C12]TBBPA DME and extracted three times with 10 mL of methylene dichloride. The combined extract was concentrated to 1 mL by a rotary evaporator and then solvent exchanged with 200 μL of hexane for analysis of the methylation products (TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME) by GC-MS.

2.4. Instrumental Analysis.

TBBPA was quantified by an Agilent 1290 Series LC system coupled with an Agilent 6460 triple quadrupole MS/MS system. Methylation products of TBBPA were detected by an Agilent 6890 gas chromatograph coupled with a model 5975C MS detector (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA). CH3I was detected by an Agilent 7890A gas chromatograph coupled with a model 7000A triple quadrupole MS/MS (Agilent Technologies). The details of the instrument parameters were based on our previous study15 and are listed in Tables S1–S3.

2.5. Quality Assurance and Quality Control (QA/QC).

Laboratory procedure blanks were conducted to control laboratory backgrounds. Blank solvents were injected for every three samples to monitor the carryover between continuous injections. Recoveries of the surrogate standards, [13C12]TBBPA and [13C12]TBBPA DME, were in the ranges of 63–90% and 77–92%, respectively. The recovery of CH3I was 78–90%. The method detection limits (MDLs) for TBBPA DME and CH3I were 3.5 fmol mL−1 and 20 nmol mL−1, respectively. Because of the lack of a standard, TBBPA MME was quasi-quantified by a reference standard of TBBPA DME. However, this would result in underestimating the real yielded amount of TBBPA MME due to the different GC-MS responses between TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME. According to our results, the response of TBBPA DME (quantification ion [M – CH3]+, 557) was ~15 times higher than that of TBBPA (quantification ion [M – CH3]+, 529) at the same molar concentration. Thus, the response of TBBPA MME was higher than that of TBBPA and lower than that of TBBPA DME. The results of TBBPA were corrected by the recoveries of [13C12]TBBPA, and the results of TBBPA DME and TBBPA MME were corrected by the recoveries of [13C12]TBBPA DME.

2.6. Statistical Analysis and Activation Energy Calculation.

SPSS Statistics 20 and Origin 2018 were used to process the data. Analysis of variance (ANOVA), including the independent sample t test and paired sample t test, was performed. Significant differences were considered when p < 0.05.

The activation energy (Ea) was calculated with the Gaussian 09 suite of programs. The density functional theory (DFT) method at B3LYP was employed. The LANL2DZ basis set for I and Br atoms and the 6–31G(d) basis set for the other atoms were used in geometry optimizations. Vibrational frequency analysis at the same level as theory was performed on all optimized structures to characterize stationary points as local minima or transition states. The calculation of intrinsic reaction coordinates (IRCs) was carried out to confirm that transition states connected to the appropriate reactants and products.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Methylation of TBBPA in Laboratory-Simulated Water.

Abiotic methylation was studied using autoclaved laboratory-simulated water. TBBPA is generally photodegraded very fast under light conditions.23 As shown in Figure S1, the photodegradation of TBBPA was observed both with and without addition of CH3I in laboratory-simulated water over 180 min at pH 7.0. Similar amounts of photodegraded TBBPA (~25%) were measured in the presence and absence of CH3I. For the reactors in the dark at pH 7.0 (Figure S1), the recoveries of TBBPA at 180 min were 98.9 ± 3.9% and 97.2 ± 4.1% for reaction groups and T controls, respectively. In addition, the recoveries of TBBPA were 95.3 ± 17.2% and 99.5 ± 22.3% for reaction groups and T controls at the end of the dark experiment (30 days), respectively, and showed only very slight variations [without significant differences (p > 0.1)] compared with the initial amount. TBBPA was transformed only very slightly under dark conditions.

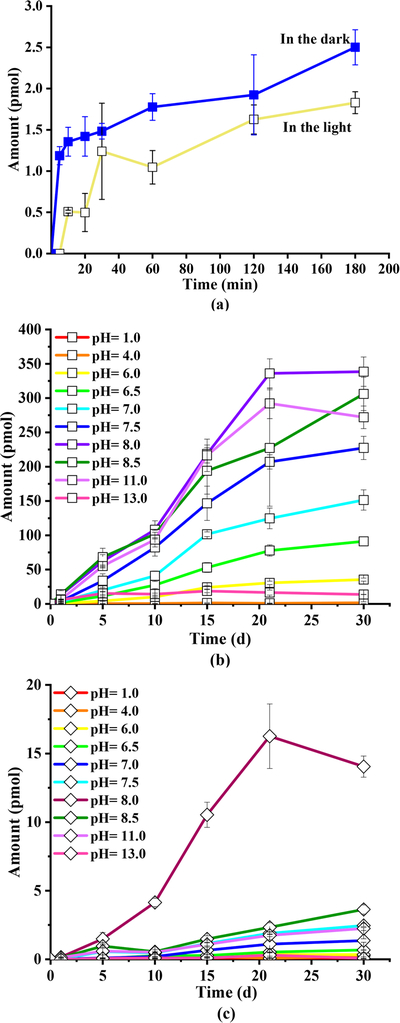

Methylation products were assessed. As shown in Figure 1a, TBBPA MME was found in the reaction groups at pH 7.0. The amounts of TBBPA MME increased from 0 (at 5 min) to 1.8 ± 0.1 pmol for the illuminated reaction and from 0 to 2.6 ± 0.2 pmol for the dark reaction within 180 min. TBBPA MME was produced under dark conditions at significantly higher concentrations (p < 0.05) than under light conditions. It might be attributed to (a) photodegradation of TBBPA and CH3I, which decreased the amount of parent compounds and inhibited the reaction, and/or (b) the methylation product, TBBPA MME, being photodegraded and resulted in lower concentrations under light conditions. No methylation product was detected in I and T control groups under 180 min light and dark reactions, further verifying the importance of abiotic methylation in the reaction system with both TBBPA and CH3I.

Figure 1.

Variations of TBBPA MME in the light and dark experiments at pH 7.0 and 180 min (a), dark experiments at different pH values within 30 days (b), and variations of TBBPA DME in the dark experiments at different pH values within 30 days (c) in laboratory-simulated water.

The results of 30 day dark reaction experiments with different pHs showed (Figure 1b) that the yields of TBBPA MME increased linearly for all tested pH values with the exception of pH 13.0. The reason was the pH-dependent hydrolysis of CH3I. According to the recovery variations of CH3I in reaction solutions (Figure S2), the degradation of CH3I increased with an increase in pH. Quickly hydrolysis-induced exhaustion of CH3I resulted in the nonlinear yield of TBBPA MME at pH 13.0. In comparison, TBBPA MME was produced the most at pH 8.0 (339 ± 21 pmol) and the least at pH 1.0 (0.11 ± 0.01 pmol) at the end of the dark experiment. The results showed the strong influence of pH on the generation of TBBPA MME. Another methylation product, TBBPA DME, could be detected with only a very small amount after 1 day in the dark and was not detectable in the light reaction. As shown in Figure 1c, the formation of TBBPA DME showed a tendency similar to that of TBBPA MME, and the amount of TBBPA DME produced was 14.0 ± 0.8 pmol at pH 8.0 at 30 days. The transformation ratios from TBBPA to TBBPA MME and to TBBPA DME at pH 8.0 were 1.7% and 0.07% at 30 days for the dark experiments, respectively.

Due to the lack of proper conditions for formation, radicals did not exist in our laboratory-simulated water system in the dark. CH3I undergoes a bimolecular nucleophilic substitution (SN2) with OH− in hydrolysis reactions, as shown in eq 1:37,38

| (1) |

TBBPA contains two phenolic hydroxyl groups and can be dissociated under suitable pH conditions to form TBBPA− and TBBPA2− ions, both of which are good nucleophiles. Therefore, TBBPA can compete with OH− through nucleophilic substitution reactions as follows (the generation of TBBPA DME was not considered due to the extremely small yield observed):

| (2) |

| (3) |

The dissociation behavior of TBBPA was strongly affected by pH values. According to the reported data, primary dissociation constant pKa1 and secondary dissociation constant pKa2 of TBBPA are 7.5 and 8.5, respectively.39 The concentrations of TBBPA− and TBBPA2− can affect their reactions with CH3I according to the different amounts of TBBPA MME formed at different pH values. Therefore, the reactions between CH3I and TBBPA− and TBBPA2− involve SN2 reactions.

According to the SN2 reaction type, the reaction velocity between OH− and TBBPA ions and CH3I can be expressed by second-order reactions (eqs 4, 5, and 6):

| (4) |

| (5) |

| (6) |

where ν1–ν3 are the reaction velocities of eqs 1–3, respectively. k1–k3 are the reaction velocity constants of eqs 1–3. [CH3I], [OH−], [TBBPA−], and [TBBPA2−] are the molar concentrations of CH3I, OH−, TBBPA−, and TBBPA2−, respectively. [TBBPA−] and [TBBPA2−] can be calculated on the basis of initially added TBBPA, pH values, and pKa1 and pKa2. Thus, the yield of TBBPA MME (MMME, moles) can be expressed as eq 7:

| (7) |

where C0 is the initial concentration of CH3I (1 mmol L−1), CT is the total molar concentration of [TBBPA], [TBBPA−], and [TBBPA2−] added to the reaction system, x is the pH value of the reaction solution, and t is the reaction time. The detailed information about the derivation of eq 7 is given in section S1 of the Supporting Information. The fitted generation plot of TBBPA MME at different pH values is shown in Figure S3. It was found that the best pH condition for abiotic methylation of TBBPA was around 8. The pH value that is suitable for methylation is also close to environmental pH conditions.

3.2. Effects of Other Environmental Factors on Abiotic Methylation.

The effect of NOM is shown in Figure S4a. NOM contains phenolic functional groups that can compete or form a conjugate with TBBPA. Therefore, the generation of TBBPA MME was restrained to some extent but not significantly (p > 0.1) with the increase in the concentration of NOM under both light and dark conditions.

The temperature is another very important factor that affects the methylation reaction between TBBPA and CH3I. At higher temperatures, the reaction was strongly promoted. The amount of TBBPA MME increased more than 20 times when the temperature increased from 4 to 35 °C (Figure S4b). The temperature-dependent reaction suggests that abiotic methylation of TBBPA produces more methylation products in the summer than in the winter.

3.3. Methylation of TBBPA in River Water.

To investigate the natural abiotic methylation potential of TBBPA mediated by CH3I, the reaction between TBBPA and CH3I in river water was further studied. Like the results of the laboratory-simulated water experiment, only TBBPA MME was detected in the 180 min light reaction, and both TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME were detected in the dark after 15 days. However, besides the abiotic methylation process, biotic methylation was also involved in the river water. Thus, the contributions of abiotic and biotic methylation were evaluated.

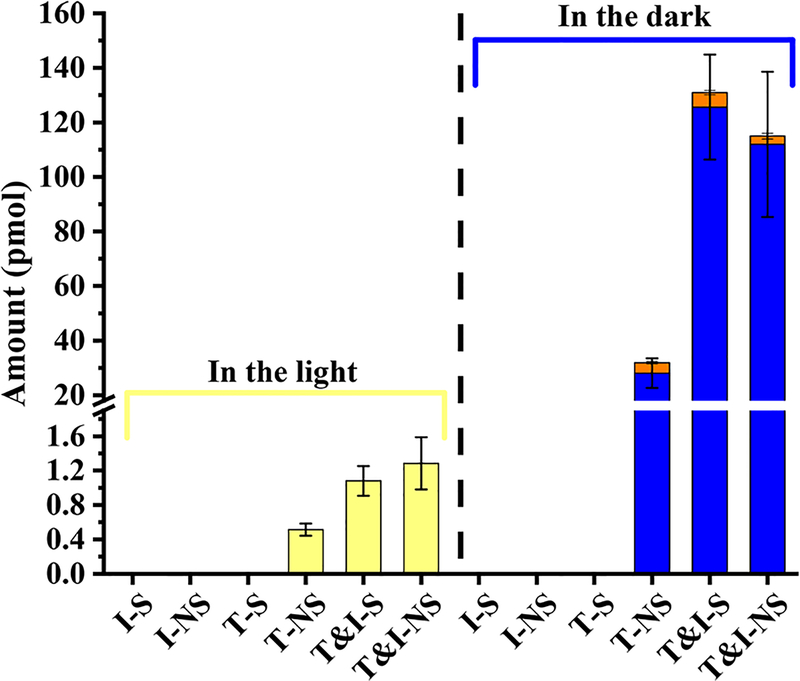

The results of control groups (Figure 2) showed that no methylation product of TBBPA was detected in I-S and I-NS controls with only CH3I in sterilized and nonsterilized river water, respectively. It was also not detected in T-S controls of only TBBPA in sterilized river water, but it could be detected in T-NS controls using nonsterilized river water (from 0.51 ± 0.07 to 28 ± 5 pmol), regardless of the light and dark conditions. The results indicated that the microorganisms existing in nonsterilized river water biomethylate TBBPA to form TBBPA MME, which was consistent with a previous report.40 The amounts of methylation products in T-NS controls could be used to evaluate the contribution of biotic methylation of TBBPA under the tested condition.

Figure 2.

Methylation products of TBBPA in river water after 180 min in the light and 15 days in the dark. The yellow bars are the amount of TBBPA MME after 180 min in the light. The blue and orange bars are the amounts of TBBPA MME and TBBPA DME, respectively, after 15 days in the dark. I, T, S, and NS stand for CH3I, TBBPA, sterilized, and nonsterilized, respectively.

The results of reactions (Figure 2) showed that, when TBBPA and CH3I were both included, the amounts of TBBPA MME in the light experiment were 1.1 ± 0.2 and 1.3 ± 0.3 pmol, respectively, in sterilized (T&I-S) and nonsterilized (T&I-NS) river water. Amounts of methylation products in the dark were 126 ± 19 and 112 ± 27 pmol for TBBPA MME and 5.3 ± 1.1 and 3.1 ± 1.1 pmol for TBBPA DME in T&I-S and T&I-NS groups, respectively. For both 180 min light and 15 day dark reactions, there were no significant differences (p > 0.1) between the amounts of methylated TBBPA in T&I-S and T&I-NS groups. The reason was considered to be the antibacterial activity of CH3I. The presence of CH3I inhibited the biotic methylation in river water.

According to our results, the methylation product TBBPA MME was largely augmented by the existence of CH3I, under both light and dark conditions. Yields of TBBPA MME from the abiotic reaction between TBBPA and CH3I were 0.9 and 3.5 times higher than those of biomethylation under conditions of 180 min light and 15 day dark reactions, respectively. The abiotic methylation of TBBPA is reported for the first time in natural water. The methylation ratio (from TBBPA to TBBPA MME) increased significantly after CH3I was added to the river water sample under a 15 day dark reaction, which demonstrated that the abiotic methylation of TBBPA is also an important pathway for the formation of TBBPA methylation products in the environment.

3.4. Abiotic Methylation Potential for Other Phenolic Compounds.

Methylation is a common biotic and abiotic transformation pathway for many organic pollutants. Other pollutants with phenolic substitution, such as bisphenol A (BPA), triclosan (TCS), the hydroxylated metabolites of polybrominated diphenyl ethers (OH-PBDEs), and polychlorinated biphenyls (OH-PCBs), may also experience a similar abiotic methylation process mediated by CH3I in the environment. To further evaluate the abiotic methylation potential for those compounds, the activation energy (Ea) for the methylation reaction of TBBPA, BPA, TCS, OH-PBDEs, and OH-PCBs was calculated and compared in the presence of CH3I and the SN2 reaction pathway.41 The schematic energy profile for the TBBPA− + CH3I → TBBPA MME + I− reaction is shown in Figure S5. The Ea value for this abiotic methylation reaction was 8.9 kcal mol−1. Through a similar reaction type, the calculated Ea values were 10.5, 19.9, 8.8, and 19.5 kcal mol−1 for the abiotic methylation of BPA, TCS, 5-OH-BDE-47, and 4′-OH-CB-61, respectively. Generally, when the Ea values are <20 kcal mol−1, the corresponding reactions are more favorable and spontaneous. The lower the Ea value, the greater potential the reaction to occur. All of the calculated Ea values were <20 kcal mol−1, indicating that all of these phenolic contaminants have great abiotic methylation potential in the presence of CH3I. These results also provide a clue about the environmental fates of other common phenolic organic pollutants of concern.

In summary, this study revealed a new and important abiotic pathway to methylate TBBPA. The abiotic methylation of TBBPA was largely affected by light irradiation, pH, temperature, and NOM concentration of the aquatic systems. On the basis of these results, the reaction between TBBPA and CH3I involves a SN2 pathway. Calculated Ea values indicate that other phenolic contaminants also exhibit a great potential for abiotic methylation mediated by CH3I in natural waters.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was jointly supported by the National Key Research and Development Project (2018YFC1800702), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21677158, 21621064, and 21806171), and the Chinese Academy of Science (XDB14010400). J.L.S. was supported by the Iowa Superfund Research Program (ISRP), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Grant P42ES013661), and by the 1000-Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.estlett.9b00445.

Additional details about the instrumental parameters and supporting discussion, Tables S1–S3, Figures S1–S5, and section S1 (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Covaci A; Voorspoels S; Abdallah MAE; Geens T; Harrad S; Law RJ Analytical and environmental aspects of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A and its derivatives. J. Chromatogr. A 2009, 1216 (3), 346–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Covaci A; Harrad S; Abdallah MAE; Ali N; Law RJ; Herzke D; de Wit CA Novel brominated flame retardants: A review of their analysis, environmental fate and behavior. Environ. Int 2011, 37 (2), 532–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Gustavsson J; Wiberg K; Ribeli E; Nguyen MA; Josefsson S; Ahrens L Screening of organic flame retardants in Swedish river water. Sci. Total Environ 2018, 625, 1046–1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Gu SY; Ekpeghere KI; Kim HY; Lee IS; Kim DH; Choo G; Oh JE Brominated flame retardants in marine environment focused on aquaculture area: Occurrence, source and bioaccumulation. Sci. Total Environ 2017, 601–602, 1182–1191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Yang S; Wang S; Liu H; Yan Z Tetrabromobisphenol A: Tissue distribution in fish, and seasonal variation in water and sediment of Lake Chaohu, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 2012, 19 (9), 4090–4096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).He MJ; Luo XJ; Yu LH; Liu J; Zhang XL; Chen SJ; Chen D; Mai BX Tetrabromobisphenol-A and hexabromocyclododecane in birds from an e-waste region in South China: Influence of diet on diastereoisomer- and enantiomer-specific distribution and trophodynamics. Environ. Sci. Technol 2010, 44 (15), 5748–5754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Feng AH; Chen SJ; Chen MY; He MJ; Luo XJ; Mai BX Hexabromocyclododecane (HBCD) and tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in riverine and estuarine sediments of the Pearl River Delta in southern China, with emphasis on spatial variability in diastereoisomer- and enantiomer-specific distribution of HBCD. Mar. Pollut. Bull 2012, 64 (5), 919–925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Morris S; Allchin CR; Zegers BN; Haftka JJH; Boon JP; Belpaire C; Leonards PEG; van Leeuwen SPJ; de Boer J Distribution and fate of HBCD and TBBPA brominated flame retardants in North Sea estuaries and aquatic food webs. Environ. Sci. Technol 2004, 38 (21), 5497–5504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Aznar-Alemany Ò; Trabalón L; Jacobs S; Barbosa VL; Tejedor MF; Granby K; Kwadijk C; Cunha SC; Ferrari F; Vandermeersch G; Sioen I; Verbeke W; Vilavert L; Domingo JL; Eljarrat E; Barceló D Occurrence of halogenated flame retardants in commercial seafood species available in European markets. Food Chem. Toxicol 2017, 104, 35–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Johnson-Restrepo B; Adams DH; Kannan K Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) and hexabromocyclododecanes (HBCDs) in tissues of humans, dolphins, and sharks from the United States. Chemosphere 2008, 70 (11), 1935–1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shi ZX; Zhang L; Zhao YF; Sun ZW; Zhou XQ; Li JG; Wu YN A national survey of tetrabromobisphenol-A, hexabromocyclododecane and decabrominated diphenyl ether in human milk from China: Occurrence and exposure assessment. Sci. Total Environ 2017, 599, 237–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Li F; Wang J; Nastold P; Jiang B; Sun F; Zenker A; Kolvenbach BA; Ji R; Francois-Xavier Corvini P Fate and metabolism of tetrabromobisphenol A in soil slurries without and with the amendment with the alkylphenol degrading bacterium Sphingomonas sp. strain TTNP3. Environ. Pollut 2014, 193, 181–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Sun FF; Kolvenbach BA; Nastold P; Jiang BQ; Ji R; Corvini PFX Degradation and metabolism of tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in submerged soil and soil–plant systems. Environ. Sci. Technol 2014, 48 (24), 14291–14299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Peng FQ; Ying GG; Yang B; Liu YS; Lai HJ; Zhou GJ; Chen J; Zhao JL Biotransformation of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A (TBBPA) by freshwater microalgae. Environ. Toxicol. Chem 2014, 33 (8), 1705–1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hou XW; Yu M; Liu AF; Li YL; Ruan T; Liu JY; Schnoor JL; Jiang GB Biotransformation of tetrabromobisphenol A dimethyl ether back to tetrabromobisphenol A in whole pumpkin plants. Environ. Pollut 2018, 241, 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chen X; Gu JQ; Wang YF; Gu XY; Zhao XP; Wang XR; Ji R Fate and O-methylating detoxification of Tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) in two earthworms (Metaphire guillelmi and Eisenia fetida). Environ. Pollut 2017, 227, 526–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Kotthoff M; Rudel H; Jurling H Detection of tetrabromobisphenol A and its mono- and dimethyl derivatives in fish, sediment and suspended particulate matter from European freshwaters and estuaries. Anal. Bioanal. Chem 2017, 409 (14), 3685–3694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Watanabe I; Kashimoto T; Tatsukawa R Identification of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A in the river sediment and the mussel collected in Osaka. Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol 1983, 31 (1), 48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Vorkamp K; Thomsen M; Falk K; Leslie H; Møller S; Sorensen PB Temporal development of brominated flame retardants in peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus) eggs from south Greenland (1986–2003). Environ. Sci. Technol 2005, 39 (21), 8199–8206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).McCormick JM; Paiva MS; Häaggblom MM; Cooper KR; White LA Embryonic exposure to tetrabromobisphenol A and its metabolites, bisphenol A and tetrabromobisphenol A dimethyl ether disrupts normal zebrafish (Danio rerio) development and matrix metalloproteinase expression. Aquat. Toxicol 2010, 100 (3), 255–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Gao SW; Guo CS; Hou S; Wan L; Wang Q; Lv JP; Zhang Y; Gao JF; Meng W; Xu J Photocatalytic removal of tetrabromobisphenol A by magnetically separable flower-like BiOBr/BiOI/Fe3O4 hybrid nanocomposites under visible-light irradiation. J. Hazard. Mater 2017, 331, 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Han SK; Yamasaki T; Yamada K Photodecomposition of tetrabromobisphenol A in aqueous humic acid suspension by irradiation with light of various wavelengths. Chemosphere 2016, 147, 124–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Wang XW; Hu XF; Zhang H; Chang F; Luo YM Photolysis kinetics, mechanisms, and pathways of tetrabromobisphenol A in water under simulated solar light irradiation. Environ. Sci. Technol 2015, 49 (11), 6683–6690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Han Q; Dong WY; Wang HJ; Liu TZ; Tian Y; Song X Degradation of tetrabromobisphenol A by ferrate (VI) oxidation: Performance, inorganic and organic products, pathway and toxicity control. Chemosphere 2018, 198, 92–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Shugui D; Guolan H; Yong C A study of methylation of inorganic tin by iodomethane in an aquatic environment with 13C carbon isotope tracer technique. Appl. Organomet. Chem 1989, 3 (1), 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chen BW; Wang T; He B; Yuan CG; Gao EL; Jiang GB Simulate methylation reaction of arsenic (III) with methyl iodide in an aquatic system. Appl. Organomet. Chem 2006, 20 (11), 747–753. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Ahmad I; Chau YK; Wong PTS; Carty AJ; Taylor L Chemical alkylation of lead (II) salts to tetraalkyllead (IV) in aqueous solution. Nature 1980, 287 (5784), 716–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Sulikowski GA; Sulikowski MM; Haukaas MH; Moon B Iodomethane. e-EROS 2005, DOI: 10.1002/047084289X.ri029m.-pub2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Avila-Zárraga JG; Martínez R Efficient methylation of carboxylic acids with potassium hydroxide/methyl sulfoxide and iodomethane. Synth. Commun 2001, 31 (14), 2177–2183. [Google Scholar]

- (30).Keng FSL; Phang SM; Abd Rahman N; Leedham EC; Hughes C; Robinson AD; Harris NRP; Pyle JA; Sturges WT Volatile halocarbon emissions by three tropical brown seaweeds under different irradiances. J. Appl. Phycol 2013, 25 (5), 1377–1386. [Google Scholar]

- (31).Dailey GD Methyl halide production in fungi. M.S. Thesis, University of New Hampshire, 2007, 293. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Itoh N; Toda H; Matsuda M; Negishi T; Taniguchi T; Ohsawa N Involvement of S-adenosylmethionine-dependent halide/thiol methyltransferase (HTMT) in methyl halide emissions from agricultural plants: Isolation and characterization of an HTMT-coding gene from Raphanus sativus (daikon radish). BMC Plant Biol 2009, 9, 116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Redeker KR; Wang NY; Low JC; McMillan A; Tyler SC; Cicerone RJ Emissions of methyl halides and methane from rice paddies. Science 2000, 290 (5493), 966–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Ooki A; Yokouchi Y Development of a silicone membrane tube equilibrator for measuring partial pressures of volatile organic compounds in natural water. Environ. Sci. Technol 2008, 42 (15), 5706–5711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Guo MM; Zheng W; Papiernik SK; Yates SR Distribution and leaching of methyl iodide in soil following emulated shank and drip application. J. Environ. Qual 2004, 33, 2149–2156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Yokouchi Y; Osada K; Wada M; Hasebe F; Agama M; Murakami R; Mukai H; Nojiri Y; Inuzuka Y; Toom-Sauntry D; Fraser P Global distribution and seasonal concentration change of methyl iodide in the atmosphere. J. Geophys. Res 2008, 113 (D18), n/a. [Google Scholar]

- (37).Gan JY; Yates SR Degradation and phase partition of methyl iodide in soil. J. Agric. Food Chem 1996, 44 (12), 4001–4008. [Google Scholar]

- (38).Gentile IA; Ferraris L; Crespi S; Belligno A The degradation of methyl bromide in some natural fresh waters. Influence of temperature, pH and illuminance. Pestic. Sci 1989, 25 (3), 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- (39).Tetrabromibisphenol A and Derivatives Environmental Health Criteria 172. World Health Organization: Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- (40).George KW; Häggblom MM Microbial O-methylation of the flame retardant tetrabromobisphenol-A. Environ. Sci. Technol 2008, 42 (15), 5555–5561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Xie J; Sun R; Siebert MR; Otto R; Wester R; Hase WL Direct dynamics simulations of the product channels and atomistic mechanisms for the OH− + CH3I reaction. Comparison with experiment. J. Phys. Chem. A 2013, 117 (32), 7162–7178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.